Abstract

Objective(s):

To examine the breadth of education or training on the consequences of traumatic brain injury (TBI) for children and adolescents with TBI and their families/caregivers.

Methods:

Systematic scoping review of literature published through July 2018 using eight databases and education, training, instruction, and pediatric search terms. Only studies including pediatric participants (age <18) with TBI or their families/caregivers were included. Six independent reviewers worked in pairs to review abstracts and full-text articles independently, and abstracted data using a REDCap database.

Results:

Forty-two unique studies were included in the review. Based on TBI injury severity, 24 studies included persons with mild TBI (mTBI) and 18 studies focused on moderate/severe TBI. Six studies targeted the education or training provided to children or adolescents with TBI. TBI education was provided primarily in the emergency department or outpatient/community setting. Most studies described TBI education as the main topic of the study or intervention. Educational topics varied, such as managing TBI-related symptoms and behaviors, when to seek care, family issues, and returning to work, school, or play.

Conclusions:

The results of this scoping review may guide future research and intervention development to promote the recovery of children and adolescents with TBI.

Keywords: family education, patient education, pediatric, self-management, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI), a leading cause of death and disability, affects children quite differently than adults (1–3). In the developing brain, a TBI can disrupt this trajectory and lead to potential physical, emotional, social, and cognitive impairments (4), negatively impacting participation in school and other activities. Limited studies have focused on the long-term consequences of pediatric TBI compared to adult populations with TBI. Some evidence suggests that recovery after pediatric TBI may vary based on race/ethnicity, gender, and comorbidities, with ethnic minorities, females, and those with more comorbidities experiencing a slower recovery compared to non-whites, male, and those with fewer comorbidities (5). Given that disparities in health outcomes may occur after TBI, it is unclear how children with TBI and their families are able to manage the consequences of injury and their recovery.

Parents and caregivers of children with TBI face challenges in learning how to care properly for their child with a TBI and determining the appropriate services needed (6). Families report challenges identifying and ensuring the student is provided the appropriate supports to succeed in the classroom (7). Parents and caregivers can experience stress long term when trying to find and provide proper care for their children (6). Intervention programs focused on providing education to youth with TBI and their families could minimize the long-term effects of TBI among this vulnerable population. Yet, research focusing on educating individuals about the consequences of TBI has included predominately adults with TBI and/or their family members (8), and most educational interventions are designed specifically for families/caregivers of adults with moderate/severe TBI.

Previous reviews have focused on education or service delivery in the healthcare or educational setting (9–11). Similarly, Hart et al. explored brain injury education and training provided to adults with TBI and/or family members (8). Children and adolescents with TBI and their families may have unique needs following injury, and the types of training or education on managing TBI-related cognitive, physical, emotional or behavioral consequences of injury have not been summarized. Therefore, we sought to review the peer-reviewed pediatric literature on education provided to children and adolescents with TBI or families/caregivers using a systematic scoping review methodology (12). Systematic scoping reviews are important for examining the scope of existing literature and identifying gaps to inform future clinical and research work. We performed a comprehensive, systematic scoping review of research published through July 2018 to examine the types of education or training on the consequences of TBI developed for children and adolescents with TBI and/or their families/caregivers and to identify gaps in the existing pediatric TBI literature. We aimed to address the following research questions:

-

What types of education have been provided to children and adolescents with TBI and their families/caregivers about the consequences of TBI?

What are the types and topics of the available TBI education or training?

At what point following injury and in what setting (e.g., emergency department, inpatient, outpatient, community) is the TBI education or training provided?

What is known about the outcomes and outcome measures of education or training on the consequences of TBI for children and adolescents with TBI and their families/caregivers?

What are the current gaps in the TBI literature related to TBI education or training?

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a systematic scoping review to: (a) examine the available, published evidence on TBI-related education or training for children and adolescents with TBI and their families/caregivers; (b) determine the types of measurement outcomes have been used to evaluate educational or training interventions; and (c) identify the gaps in the literature to make recommendations to guide future clinical and research work (13). Given that we were not interested at this time on the effectiveness of TBI education or training, a systematic scoping review is more appropriate than a systematic review to answer our aforementioned broad and exploratory questions. Our study used the updated scoping review methodology of Levac et al. (12), which includes up to six framework stages: identifying the research question (stage 1); identifying relevant studies (stage 2); study selection (stage 3); charting the data (stage 4); summarizing and reporting results (stage 5); and the optional stage of consultation with stakeholders (stage 6). Reporting followed the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines (14).

Eligibility Criteria

The target population included children and/or adolescent participants (age <18) with TBI of any severity or their families/caregivers. If an article included both pediatric and adult TBI participants and they were reported separately or the education was different, we included the article. Family or caregivers included parents, siblings, foster parents, other family members or relatives, and paid or unpaid caregivers. We also included studies involving children or adolescents with acquired brain injury (ABI) or general trauma, if a TBI subpopulation was included and education or training about the consequences of TBI was provided. Only articles that described education, information, or training on the consequences of pediatric TBI, whether behavioral, cognitive, emotional, and/or physical, were included.

For this review, TBI education focuses on supporting an individual’s knowledge and management of the consequences of injury. TBI information refers to any facts or knowledge related to TBI-related consequences of injury, as well as managing the consequences of injury. TBI-related training refers to learning specific skills related to managing the consequences of injury. We were also interested in studies on self-management or symptom management training or comprehensive education programs that addressed a variety of topics. It is possible for TBI-related training to also include some aspects of education. For example, a social skills training program may focus on the skills of turn taking and self-regulation of emotions, but also include an educational component such as common social communication and interaction issues following TBI. Studies without significant detail on the education itself were also included to capture the breadth of the relevant literature. We also included studies where education was provided as a control for an active intervention, surveys on educational practice or materials provided by professionals, information on needs assessments, as well as education program descriptions. All studies were peer-reviewed and in the English language.

We excluded studies where the target population for education was healthcare professionals, coaches, athletic trainers, educators, or the general public. We also excluded training or education focused on prevention (e.g., shaken baby or concussion prevention programs) or specific return-to-school strategies. Review articles were not included, and articles were excluded if they were non-peer-reviewed materials or grey literature, such as fact sheets or informational pamphlets, letters or editorials, books or book chapters, book reviews, theses or dissertations, and conference abstracts.

Information Sources

Studies were systematically identified using PubMed, PsychINFO, PsychBITE, ERIC, CINAHL, ERABI (Evidence-Based Review of Moderate to Severe Acquired Brain Injury), PROSPERO, and the Cochrane Library databases through July 2018. Two medical librarians developed search strategies. We used the search strategies from the original review as described in Hart et al. (12), from which over 3,209 abstracts were screened, which yielded 88 publications on adult TBI and family education and 33 publications on pediatric/family education. The original database searches included literature from inception up to October 24, 2016. On July24, 2018, we updated our search to identify pediatric articles published since the last search (October 24, 2016), using the following pediatric search terms (i.e., pediatric*, paediatric*, child*, adolesc*). The search strategies are included in Appendix 1. Search results were exported into an Excel file, and all duplicates were removed. The search yielded 293 additional unique abstracts.

Study Selection

Six reviewers working in pairs were randomly assigned abstracts and full-text articles to screen independently. Disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached. If consensus could not be reached, a third reviewer reviewed the abstract and resolved the disagreement. During the abstract screening phase, duplicates and irrelevant abstracts were removed. During the full-text review phase, we identified multiple publications (n=6) based on the same study sample. We included either the first such publication or the most complete study, but referenced all related publications in the Results.

Data Abstraction

The review team met to discuss and finalize the variables tobe abstracted from the full-text articles. A data abstraction form was created using REDCap electronic data capture tools (15, 16). Reviewers worked in pairs to extract data and resolved discrepancies through discussions. If discrepancies were not resolved, the reviewers included the project lead (MRP) or a third reviewer. Using REDCap, we abstracted data on sample characteristics, study design, type of education or training, education or training delivery methods, dose/duration of education or training, outcomes used in studies evaluating education or training interventions and results, and the authors’ main conclusions. When samples were of mixed ages (adults and pediatric) and etiologies (e.g., TBI and stroke), we only abstracted outcome measures and results including the pediatric TBI sample.

Critical Appraisal

We did not include a critical appraisal of the individual sources of evidence, as our focus was to describe the types of education or training available for children and adolescents with TBI or their families/caregivers.

Synthesis of Results

Studies were grouped by TBI injury severity, and then summarized by the setting of the TBI education/training, who received the education/training, the study design, and the methods of education/training delivery. We analyzed the data by performing descriptive statistics using Stata 17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), and created a summary table. Using the data file with all abstracted data, we identified all outcome measures by name that were used to evaluate education or training interventions and identified the studies using each. We then qualitatively grouped the outcome measures by domain (e.g., physical functioning, cognitive functioning, TBI knowledge).

Results

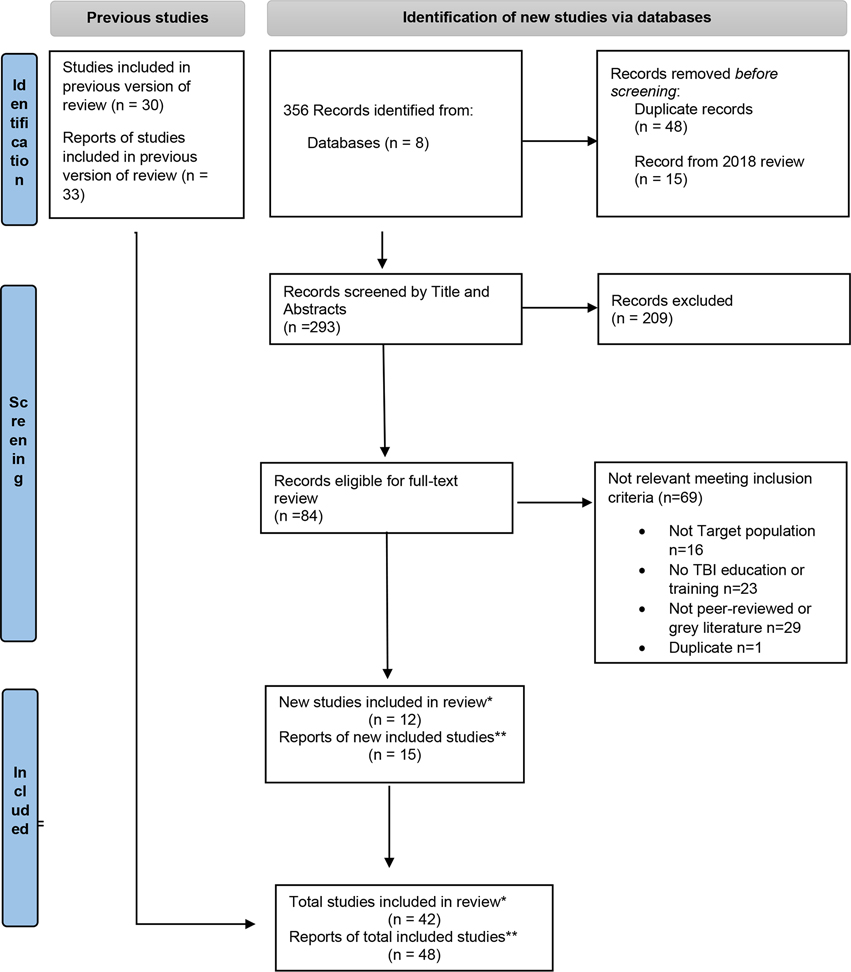

Figure 1 includes details on the study selection process. We initially identified 356 records, and then removed 48 duplicate records and 15 additional records from the initial review. During the review of 293 abstracts, we identified 209 as irrelevant. The remaining 84 abstracts were included for full-text review, of which 69 articles were excluded, leaving 15 articles eligible for data abstraction. Of the 15 articles, 12 articles were unique studies and three articles included the same study sample as one of the 12 unique studies. Thirty-three pediatric studies identified but not included in the Hart et al. (12) review were included. Of the 33 articles, we identified 30 unique studies and three publications that used the same participant data but reported different outcomes. Thus, 42 unique studies were included in this scoping review.

Figure 1. Study Selection.

Footnote. * Studies are unique articles, where the data or subjects are not used in another article included in this review. **Reports are any articles that meet our inclusion criteria, which may include multiple articles using the same data or subjects.

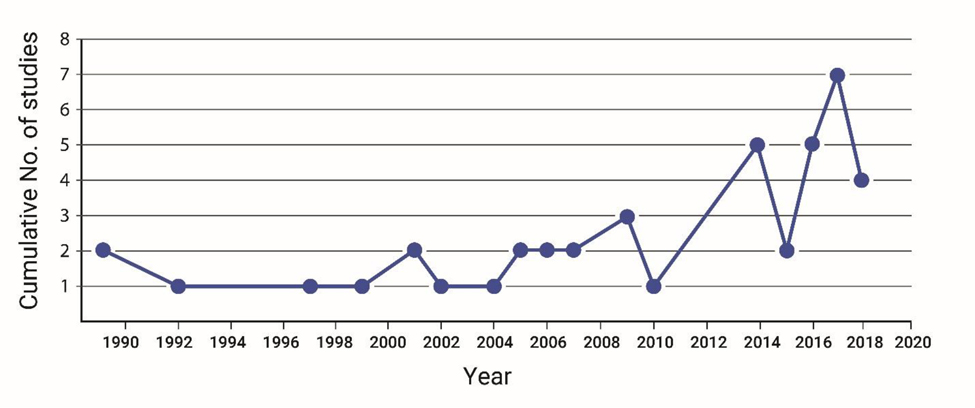

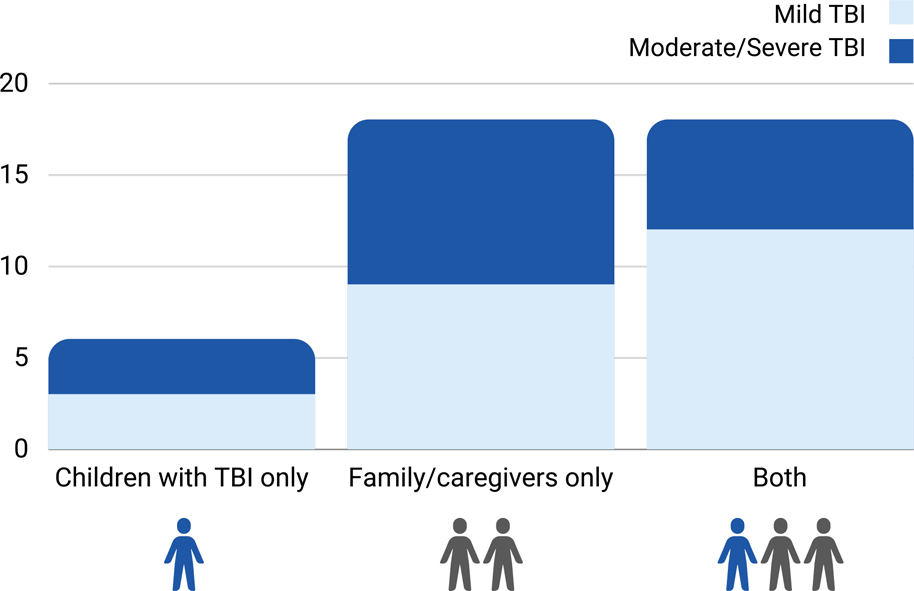

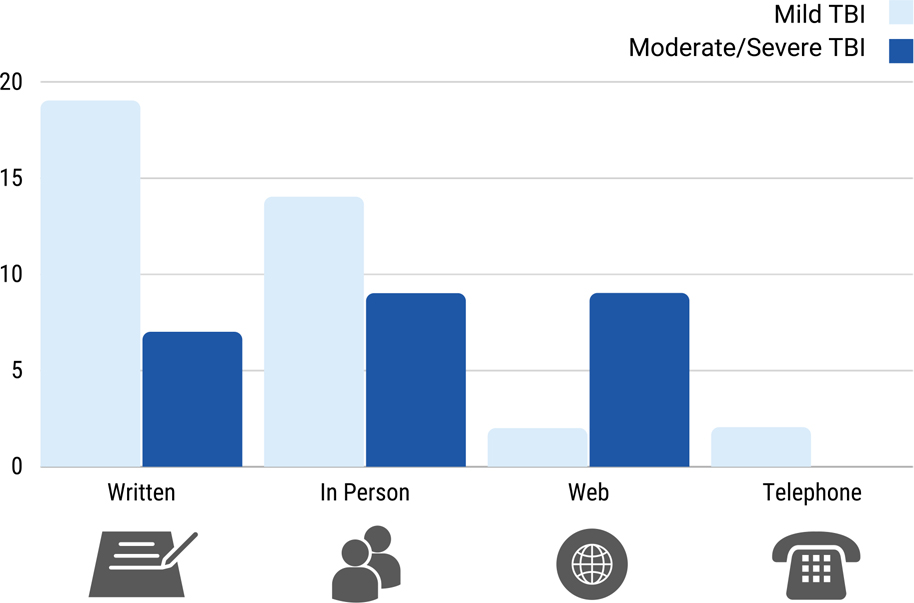

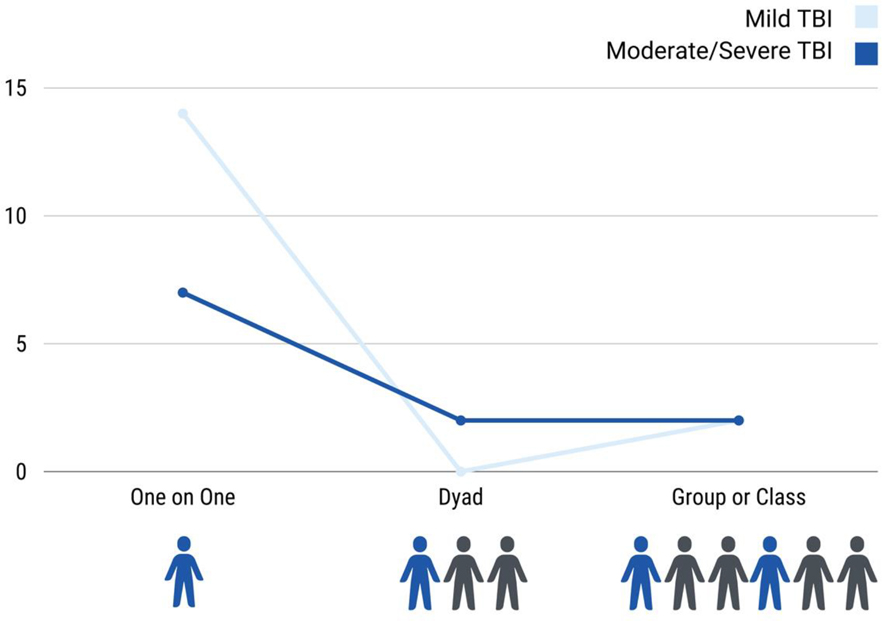

Table 1 provides an overview of the 42 studies. Table 2 includes details on each study, such as the type of TBI education or training and study results, grouped by injury severity. Since 1990, the number of studies on education or training in TBI-related consequences increased (Figure 2). Overall, we found very few studies that geared such education and training to only children or adolescents with TBI (Figure 3). Most studies focused on family/caregivers only or provided education/training to both family/caregivers and children/adolescents with TBI (Figure 4). The education or training was delivered using a variety of methods (Figure 5), and in-person education/training was mostly delivered one-on-one (Figure 6).

Table 1:

Pediatric Education Study Table

| Mild TBI (N=24) | Moderate/Severe TBI (N=18) | Total Sample (N=42) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Education Target Population | |||

| Children with TBI only | 3 | 3 | 6 | |

| Family/caregivers only | 9 | 9 | 18 | |

| Both individual and family/caregivers | 12 | 6 | 18 | |

|

TBI or ABI including TBI | |||

| TBI specifically | 22 | 11 | 33 | |

| ABI including TBI | 2 | 7 | 9 | |

|

Chronicity of TBI (not mutually exclusive) | |||

| Emergency care | 18 | 1 | 19 | |

| Acute care | 2 | 3 | 5 | |

| Inpatient rehab | 1 | 5 | 6 | |

| Outpatient | 7 | 16 | 23 | |

| Other setting | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

|

Education | |||

| Main topic | 20 | 8 | 28 | |

| One Component | 4 | 10 | 14 | |

|

Education Delivery methods (not mutually exclusive) | |||

| Written info | 19 | 7 | 26 | |

| In person | 14 | 9 | 23 | |

| Telephone | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Web | 2 | 9 | 11 | |

| Not reported | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

|

In person one on one deliverymode (not mutually exclusive categories) | |||

| One on one | 14 | 7 | 21 | |

| Dyad | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Group or class | 2 | 2 | 4 |

Table 2:

Pediatric Education Study Table (n=42)

| Author, Year, Country | Article Title | Study Design | Setting | Target Population | Education/Training Description | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild TBI (n=24) | ||||||

| Kerr et al 2007(17), Scotland | A survey of information given to head-injured patients on direct discharge from emergency departments in Scotland | Survey of education practices | ED |

TBI Child/Family *including adults No sample |

Discharge Instructions (DIs) on the physical and physiological changes, cognitive deficits,problems at home,and social difficulties. | Pamphlets should concentrate more on postconcussion symptoms than emergency features. |

| Hwang et al 2014(18), USA | Are pediatric concussion patients compliant with discharge instructions? | Uncontrolled case study | ED |

TBI

Child/Family 150 children 8–17 years |

DIs on return to play. | Pediatric patients returned to play even when some were symptomatic or did not receive medical clearance. |

| Upchurch et al 2015(19), USA | Discharge instructions for youth sports-related concussions in the emergency department, 2004 to 2012. | Survey of education practices | ED |

TBI Child/Family 497 youth aged <18 years |

DIs on recommendations for cognitive or physical rest. | An increase in provision of DIs, but a need still exists to provide appropriate discharge recommendations. |

| Parsley et al 1997(20), UK | Head injury instructions: a time to unify. | Survey of education practices | ED |

TBI Child/Family *including adults No sample |

Head injury information cards on symptoms and advice. | Inconsistent information provided and some were not evidence-based. |

| Ponsford et al 2001(21), Australia | Impact of early intervention on outcome after mild traumatic brain injury in children. | Experimental: Post-test only with non-randomized control group | ED |

TBI Child/Family 130 children aged 6–15 years, 96 matched controls |

Educational booklet on concentration, headaches, fatigue, memory, anger, noise sensitivity, eye problems, and managing these symptoms. | Education impact was small, but booklet resulted in lower symptom and reduced stress. |

| Olsson et al 2014(22), Australia | Evaluation of parent and child psychoeducation resources for the prevention of paediatric post-concussion symptoms. | Experimental: RCT | ED and community/outpatient |

TBI Child/Family 49 families, children aged 6–16 years |

Parent information booklet on mTBI and child education website regarding mTBI, common sequelae, strategies to RTP and school, managing post-injury psychological distress, etc. | Intervention program did not reduce symptoms, mTBI knowledge, psychological distress, behavioral symptoms, health-related quality of life and processing speed, and parents’ psychological distress. |

| Renaud et al 2016(23), The Netherlands | Activities and participation of children and adolescents after mild traumatic brain injury and the effectiveness of an early intervention (Brains Ahead!): study protocol for a cohort study with a nested randomised controlled trial. | Experimental: RCT | ED |

TBI Child/Family No sample |

Individualized psychoeducation and practical advice on managing symptoms via telephone by an interventionist. | N/A |

| Kirelik&McAvoy2016(24), USA | Acute concussion management with remove-reduce/educate/adjust-accommodate/pace (REAP). | Uncontrolled case study | ED |

TBI Child/Family 11 year old boy |

REAP education manual and session provided to parents and students about concussion symptoms, how to promote recovery, as well as reducing stimulation at home and cognitive demands. | The REAP manual can facilitate patient education and aftercare instructions in a busy ED. Case patient had a prompt and complete recovery. |

| Brooks et al 2017(25), USA | Symptom-guided emergency department discharge instructions for children with concussion. | Experimental: RCT | ED |

TBI Child/Family 117 children aged 7–17 years |

Symptom guide DIs to recognize better the somatic, emotional, and cognitive signs and symptoms of post-concussive syndrome. | Intervention and control group found the DIs helpful. Caregivers found the DIs significantly more helpful compared to standard ones. |

| Swaine & Friedman 2001(26), Canada | Activity restrictions as part of the discharge management for children with a traumatic head injury. | Program description | ED and acute care |

TBI Family Parents of children (0–18 years) with concussion |

Educational program including written information on activity restrictions and other topics, including symptom management injury prevention, and follow-up appointments and resources. | N/A |

| Warren &Kissoon 1989(27), Canada | Usefulness of head injury instruction forms in home observation of mild head injuries. | Post-test only with randomized control | ED |

TBI Family 72 Parents of children (mean age= 4.44 years, SD = 3.9 years) with minor head injury (GCS 15, no loss of consciousness or skull fracture) |

Written and standard verbal DIs related to symptom monitoring and mild TBI. | No statistical difference on symptom recall and satisfaction with instructions, between verbal alone and verbal with written instructions. Those who only received verbal instructions rated having written instructions as significantly more useful than those who received written instructions. |

| Ismael et al 2016(28), USA | Impact of video discharge instructions for pediatric fever and closed head injury from the emergency department. | Experimental: RCT | ED |

TBI Caregivers 32 caregivers (17 control and 15 intervention) |

Caregivers received verbal DIs along with written instructions; Intervention group viewed an additional 3.5-minute video alone in the exam room after receiving the standard care instructions. | Intervention group had clinically significant greater post-test knowledge immediately after DI delivery compared to control group, with no age, sex, or education effects. |

| Boddeal 2015(29), Australia & New Zealand | A critical examination of mild traumatic brain injury management informationdistributed to parents. | Survey of education practices | ED and acute care |

TBI Family No sample |

Information pamphlets to educate parents of children with mTBI on diagnostic terminology, management of physical and cognitive symptoms, return to school/play, referrals for existing problems, and information on second impact syndrome. | None of the pamphlets achieved the desired reading level scores. Only 3 out of 27 pamphlets included all 9 criteria recommended by CDC. No pamphlet was free of confusing and incorrect information. |

| Thomas et al 2018(30), USA | Parental knowledge and recall of concussion discharge instructions. Journal of emergency nursing. | Uncontrolled case study | ED |

TBI Family Families of patients aged 11–22 years with concussion |

Written DIs (along with verbal reinforcement) outlining re-flag symptoms, common postconcussive symptoms, importance of physical/cognitive rest, and primary medical doctor or concussion specialist follow-up | Receiving verbal instructions about follow-up care and rest was associated with improved recall of these discharge instructions. Nearly 20% of parents could not spontaneously identify 3 common postconcussive symptoms. 19% of parents misidentified a red-flag symptom (e.g., facial droop, seizure, slurred speech, or coma) as a common postconcussive symptom. |

| Curran et al 2018(31), Canada | Essential content for discharge instructions in pediatric emergency care: aDelphi study. | Survey of education practices | ED |

Mixed Etiologies/TBI Family No sample |

Five most essential DIs content for caregivers of children with TBI receiving ED care based on a Delphi study. Other conditions included were asthma, vomiting/diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, minor brain injury, and bronchiolitis. | Top 5 content: 1. Return to the ED if the child has a headache not helped by analgesia; 2. Refrain from returning to activities until the child is feeling back to normal; 3. Give acetaminophen or ibuprofen according to weight-based guidelines to relieve headaches; 4. Return to the ED if the child develops a major change in behavior within 24–48 h of discharge; 5. Return to the ED if the child has repeated vomiting. |

| Mortenson et al 2016(32), Canada | Impact of early follow-up intervention on parent-reported postconcussion pediatric symptoms: a feasibility study. | Experimental: RCT | ED and community/outpatient |

TBI Family 66 parents of children aged 5–16 years with mild brain injury or concussion |

Parents were provided via telephone by an interventionist with recommendations for symptom management and activity participation, reassured regarding concussion recovery, and provided resources with Web links and education materials. | No significant difference were found between those receiving telephone counseling versus usual care regarding reporting of postconcussive symptoms and family stress. |

| Ward et al 1992(33), UK | Use of head injury instruction cards in accident centres. | Survey of education practices | ED |

TBI Child *including adults 87 patients aged 11 years and older |

Head injury instructions with symptoms with follow-up clinic appointment information | 56 reported receiving the instruction card, while 31 did not remember receiving an instruction card. |

| Lane et al 2017(34), USA | Retrospective chart analysis of concussion discharge instructions in the emergency department. | Survey of education practices | ED |

TBI Child *including adults 795 children aged 17 and younger |

Documentation of education provided on concussion precautions or instructions, printed DIs, and return-to-play precautions. | Only 11% of children with concussion and 29% of all sports-related concussions received DIs. |

| Chavez et al 2018(35), Mexico | Feasibility and effectiveness of a parenting programme for Mexican parents of children with acquired brain injury-Case report. | Uncontrolled case study | Community/outpatient |

ABI/TBI (50%TBI) Family 4 parents with children aged 6–12 years with ABI |

Group sessions on dealing with a head injury in the family, child’s behavior, systematic us of everyday interactions, changing behavior, planning for better behavior, dealing with stress, your family as a team. | ABI education in combination with Signposts are feasible in Mexican population; intervention was effective in improving parking skills and reducing parental stress and improving child’s behavior |

| McDougall et al 2006(36), Canada | An evaluation of the paediatric acquired brain injury community outreach programme (PABICOP). | Experimental: Quasi-experimental with nonequivalent comparison group | Rehabilitation/Community/outpatient |

ABI/TBI (Unclear TBI but appears to be 100% TBI) Family 96 parents of children and youth aged 1–19 years with mild, moderate, or severe brain injury (64 experimental; 32 control) |

Information/education for parents about the effects of BI and appropriate strategies for dealing with these effect. | Intervention group scored higher than comparison group regarding knowledge of ABI at both post-test and follow-up. No other significant differences were found for any of the other family outcomes. |

| Babocket al 2017(37), USA | Adolescents with Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Get SMART: An Analysis of a Novel Web-Based Intervention | Experimental: Open pilot | Community/outpatient |

TBI Child/Family 21 adolescent aged 11–18 years with mTBI/concussion-parent dyads with 13 receiving program |

Web-based intervention with education and training in self-management and effective coping, which includes educational modules on problem-solving training, and stress management/relaxation training. Educational modules that provided anticipatory guidance and techniques to manage consequences of injury. | Concussion knowledge or behavior problems did not change significantly from baseline to the 4-week assessment. Nonsignficant differences in symptom burden, but greater time in program was associated with quicker recovery. |

| Dobneyet al 2017(38), Canada | Evaluation of an active rehabilitation program for concussion management in children and adolescents | Experimental: Pre-post without control | Community/outpatient |

TBI Child/Family 277 youth with concussion (mean age = 14.1 years, SD = 2.3 years) |

Youth and family educated on recovery, managing symptoms, return-to-play and return-to-school recommendations, energy conservation, sleep hygiene, nutrition, hydration and self-management tools. | Compared to pre-intervention, post-concussion symptoms improved; each symptom cluster (physical, cognition, emotion, sleep) improved at follow-up. |

| Hunt et al 2016(39), Canada | Development and feasibility of an evidence-informed self-management education program in pediatric concussion rehabilitation | Experimental: Pre-post without control | Community/outpatient |

TBI Child/Family 62 parents and 25 youth with concussion aged 5–18 years (total, n=87) |

90-min interactive educational group session with slide show and written resource booklet; Education was on the overview of concussion, symptoms, how to explain concussion to others, then evidence-based best practice guidance regarding concussion recovery; includes energy conservation, sleep hygiene, nutrition, relaxation, and return to school, activities, and sports. | Most participants (86/87) reported that they enjoyed the program and would recommend it to others. The primary reason cited was receiving comprehensive information from a credible professional. Ratings of ‘excellent’ were made by participants for information presented (63/87), delivery and format (63/87), length of session (49/87), and ease of understanding (70/87). |

| Reed et al 2015(40), Canada | Management of persistent postconcussion symptoms in youth: a randomised control trial protocol. | Experimental: RCT | Community/outpatient |

TBI Child No sample |

Standard of care intervention for youth aged 10–18 with persistent post-concussive syndrome, including what is a concussion, sleep hygiene, relaxation strategies, self-management tools, etc. | N/A |

| Moderate-to-Severe TBI (n=18) | ||||||

| Ganet al 2010(42), Canada | Development and preliminary evaluation of a structured family system intervention for adolescents with brain injury and their families | Program description/evaluation | Community/outpatient |

ABI/TBI Child/Family 8 adolescents with ABI (5 with TBI) aged 13–18 years and their family members (n=14) |

Feedback received from adolescents with TBI and their families on an educational manual that includes: What happens after brain injury?; common changes after brain injury; brain injury happens to the whole family; being a teen and achieving independence; emotional and physical recovery are two different things; coping with loss and change; managing intense emotions; managing stress and taking care of self; setting SMART goals and tracking progress. | Adolescents rated the intervention as helpful; Both adolescents and family members would recommend the intervention to others; They reported that the intervention was relevant, included all of the most important information, and the handouts were easy to read and understand. |

| Beardmore 1999(43), Australia | Does information and feedback improve children’s knowledge and awareness of deficits after traumatic brain injury? | Experimental: RCT | Community/outpatient |

TBI Child 21 children and adolescents with severe TBI aged 9–16 years |

Intervention group: 30-minute session with written materials on information about the brain, how it is injured, coma, recovery, and problems that can result from brain injury; individual information about the child’s accident (e.g., when and how it occurred was also provided, along with specific strengths and weaknesses) Control group: Information on study habits, time management for school tasks, etc. |

No significant group differences in TBI knowledge with both groups showing increased knowledge; No group or time effects of awareness of TBI deficits, child’s self-esteem. Parents in intervention group reported a greater reduction in stress pre-to-posttest compared to control group. Memory difficulty was associated with poor knowledge. |

| Laheyet al 2017(44), USA | The role of the psychologist with disorders of consciousness in inpatient pediatric neurorehabilitation: A case series. | Uncontrolled case study | Rehabilitation |

ABI/TBI Family 3 parents of 3 children/adolescents with ABI (1 with TBI) aged 13–18 years and their family members (n=14) |

Psychoeducation on recovery and protocols, aphasia, psychotherapeutic interventions, referrals, recommendation for educational services, and caregiver coping strategies, including self-care and stress management strategies. Cognitive-behavioral therapy was used to support the development of effective anxiety management strategies. | Patient’s behavior remained inconsistent with command following; psychologist and cognitive therapist trained caregivers on determining emergence from disorders of consciousness in the home setting. |

| Antoniniet al 2014(45), USA | A pilot randomized trial of an online parenting skills program for pediatric traumatic brain injury: improvements in parenting and child behavior. | Experimental: RCT | Community/outpatient |

TBI Family 37 caregivers of children aged 3–9 years |

Intervention group: Parenting skills training and Control group received internet educational resources only, such as links to brain injury associations and a national database of educational resources on pediatric brain injury. Content included mechanisms and TBI sequelae, advocacy, stress, and behavior. | Training resulted in significantly more parenting behaviors compared to education alone. Both groups reported a nonsignificant decrease undesirable behaviors and increase in child compliance over time. Higher income parents appeared to benefit more out of the education control group. |

| Piovesanaet al 2017(46), Australia | A randomised controlled trial of a web-based multi-modal therapy program to improve executive functioning in children and adolescents with acquired brain injury. | Experimental: RCT | Community/outpatient |

ABI/TBI Child 60 children/adolescents with ABI (19 with TBI) aged 8–16 years; 30 Intervention; 30 Control |

Mitii™ program targeted gross motor or physical activity, cognition and visual perception, or upper limb movement. | No differences found; however, a significant and large effect was found on training dose effect. Program was not effective with improving executive functioning. |

| Raj et al 2018(47), USA | Effects of web-based parent training on caregiver functioning following pediatric traumatic brain injury: A randomized control trial. | Experimental: RCT | Community/outpatient |

TBI Family 113 families of children with TBI aged 3–9 years |

Web-based intervention included live coaching, and training in managing challenging child behaviors, TBI education, stress management, and communication. Education focused on parenting skills, coping with stress, behavior management, dealing with anger, cognitive problems, positive parenting, as well as pain management, parents/siblings, social development and TBI, etc. Comparison group received online web content about TBI. | Caregiver depression was lower in the Intervention group compared to the comparison groups. No differences in caregiver psychological distress, parenting stress, or parenting efficacy. |

| Wade et al 2006(48), USA | The efficacy of an online cognitive-behavioral family intervention in improving child behavior and social competence following pediatric brain injury. | Experimental: RCT | Community/outpatient |

TBI Child/Family 46 children and adolescents with TBI aged 5–16 years and their family members |

Online education provided on the importance of problem solving, communication, and strategies for addressing cognitive and behavioral problems, and stress management. | Children in the treatment group had greater self-management/compliance with parental requests scores compared to control group. No group differences on reporting child behavior problems. |

| Wade et al 2014(49), USA | Counselor-assisted problem solving improves caregiver efficacy following adolescent brain injury. | Experimental: RCT | Community/outpatient |

TBI Child/Family 132 children with TBI aged 12–17 years and their family members (54 CAPS Intervention; 67 Information Resource Intervention) |

Families were encouraged to access online information on pediatric TBI. Weekly sessions focused on problem solving, family problem solving strategies, addressing common cognitive and behavioral consequences of TBI. | CAPS participants reported a greater decrease in depression compared to IRC group, when 5 or more sessions were completed. Differences were found among nonfrequent computer users, where CAPS parents reported higher levels of caregiver efficacy than IRC group. |

| Dise-Lewis et al 2009(50), USA | BrainSTARS: pilot data on a team-based intervention program for students who have acquired brain injury. | Experimental: Pre-post without control | Community/outpatient |

ABI/TBI (Unclear TBI but appears to be 100% TBI) Family 30 children with TBI aged 2 days – 18 years and their parents/guardians (n=41) |

Comprehensive educational manual for the BrainSTARS program. Content included pediatric TBI, including common sequelae, normal developmental accomplishments, and the impact of brain injury at various developmental stages; effective approaches to behavior and learning problems in children who have ABI; list of 20 common neurodevelopmental deficits, behavioral symptoms associated with those deficits, and interventions specific to the underlying neurodevelopmental weakness. | BrainSTARS appeared to increase the competencies of parents, and the usefulness of the educational manual was rated very highly. |

| Wade et al 2009(51), USA | Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a web-based parenting skills program for young children with traumatic brain injury. | Experimental: Pre-post without control | Community/outpatient |

TBI

Family Families of 9 children with TBI aged 3–8 years |

Web-based program focused on positive parenting skills, coping with stress, behavior management following TBI, dealing with anger, cognitive problems and strategies, etc. | Program resulted in an increase in praising, describing child’s play, and few negative behaviors towards child; No reduction of problem behaviors; All parents who participated liked the program. Attrition and nonadherance were high. |

| Wadeet al 2009(52), USA | Brief report: Description of feasibility and satisfaction findings from an innovative online family problem-solving intervention for adolescents following traumatic brain injury. | Experimental: Pre-post without control | Community/outpatient |

TBI

Child/Family 9 adolescents with TBI aged 11–18 years and 1 or more family members for each |

Web-based, self-guided material in 10 sessions on cognitive, emotional functioning, and behavior changes after TBI and strategies to manage them. | Participants found the program to be easy to understand and helpful. |

| Wade et al 2005(53), USA | Can a web-based family problem-solving intervention work for children with traumatic brain injury? | Experimental: Pre-post without control | Community/outpatient |

TBI

Child/Family 6 families (8 parents, 5 siblings, and 6 children with TBI aged 5–16 years) |

Web-based, self-guided didactic information regarding the cognitive and behavioral changes after TBI and behavior management strategies to address changes. | Program resulted in a significant reduction in antisocial behaviors, and nonsignificant changes in executive functioning, parent-child interaction, and family functioning. Children reported significant reduction in conflict with parents, but no change as reported by parents. Website and videoconferences were ranked as moderately to very easy to use. Website rated as very helpful, and videoconferences rated as extremely helpful. |

| Verhelst et al 2017(54), Belgium | How to train an injured brain? A pilot feasibility study of home-based computerized cognitive training. | Uncontrolled case study | Community/outpatient |

TBI

Child 5 children with TBI aged 11–18 years |

BrainGames on an iPad that included games to train different aspects of cognitive functioning, including sustained, selective, and divided attention, inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility, verbal and visuospatial working memory, updating, and processing speed. | Cognitive improvements were retained or increased at the time of follow-up, except regarding attention. Intervention was feasible and showed promise with improving cognitive functioning. |

| Aitken et al 2005(55), USA | Experiences from the development of a comprehensive family support program for pediatric trauma and rehabilitation patients. | Program description/evaluation | Acute care and rehabilitation |

TBI

Family No sample included |

Program for family support and education for hospitalized trauma patients, including TBI. Education on how to work the system, finding resources, understanding TBI and SCI, self-care for parents, etc. | Participation varied; barriers included scheduling, lack of incentives for attending, emotional and physical discomfort or exhaustion, and lack of bonding to group leaders. |

| Eisner and Kreutzer1989(56), USA | A family information system for education following traumatic brain injury. | Program description | Acute care, rehabilitation, community/outpatient |

TBI

Family No sample included |

Collection of 15 articles helpful to educate family members of patients with TBI. | N/A |

| Gillett 2004(57), Canada | The Pediatric Acquired Brain Injury Community Outreach Program (PABICOP) - an innovative comprehensive model of care for children and youth with an acquired brain injury. | Program description | Acute care, rehabilitation, community/outpatient |

ABI/TBI

Child/Family No sample included |

PABICOP provides education to family members about the consequences of TBI and how to manage consequences, such as headaches, sleep disturbances, fatigue, and irritability. | N/A |

| Holland and Holland2002(58), USA | Children’s health promotion through caregiver preparation in pediatric brain injury settings: Compensating for shortened hospital stays with a three-phase model of health education and annotated bibliography. | Program description | Acute care, rehabilitation, community/outpatient |

ABI/TBI

Family No sample included |

Three phases of education for caregivers of pediatric brain injury: 1) ICU through acute hospitalization; 2) through acute inpatient rehabilitation; 3) through outpatient rehabilitation and community re-entry. The educational materials (written and video) are not meant to substitute attention and care from providers. | N/A |

| Wright et al 2007(59), Australia | The Brain Crew: an evolving support programme for children who have parents or siblings with an acquired brain injury. | Program description/evaluation | Rehabilitation |

ABI/TBI

Family Initial pilot included 5 young and teenage children on an inpatient rehabilitation unit; program expanded and included 56 children enrolled, 49 finished, and 44 completed program |

Education included topics, such as brain and brain injury, physical changes, cognitive changes, behavioral and emotional changes, and problem solving and coping. Parents provided with an information sheet, and children provided an activity and information book. |

Program benefits reported: coping with family change, learning more about ABI and how family member changed,feeling less anxious and worried about family member, and less sad because they understood more, participants able to meet other children who have family members with ABI. Parents reported positive program outcomes. Children reported improvements in education and affect, understood ABI better, coping better, and felt involved again, etc. |

Figure 2. Published Studies by Year (N=42).

Figure 3. Pediatric Education Studies Key Finding.

Figure 4. Education Target Population.

Figure 5. Education Delivery Method (Not mutually exclusive categories).

Figure 6. In-Person Education Delivery Mode (Not mutually exclusive categories).

Table 3 depicts a summary of the types of outcome measures by domains used in studies evaluating the effects of education/training. Nearly 90 different outcome measures were used to assess the effects of the education/training and approximately 30 study-developed measures were used to assess parenting skills, intervention acceptability/feasibility, process, usefulness, or satisfaction. Most of the outcome measures used were common data elements (CDEs) for pediatric TBI, and the vast majority addressed cognitive/neuropsychological or behavioral functioning domains.

Table 3:

Measures Used to Evaluate Pediatric or Family/Caregiver Outcomes by Domain

| Domains | No. of measures | No. of studies | Most commonly used measures (No. of studies) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Functioning | 5 | 4 | Functional Disability Inventory (FDI) (2) |

| Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory - physical function (1) | |||

| Post-concussion Symptoms | 6 | 9 | Post-Concussion Symptom Scale (PCSS) from Immediate Post-Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing (ImPACT) - (4) |

| Health and Behavior Inventory (HBI) (3) | |||

| Post-Concussion Symptom Inventory (PCSI) (2) | |||

| Psychosocial | |||

| Behavioral functioning | 10 | 15 | Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (9) |

| Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI) (4) | |||

| Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale (CAFAS) (1) | |||

| Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (1) | |||

| Psychological | 11 | 8 | Parenting Stress Index, Third Edition (PSI) (4) |

| Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) (3) | |||

| Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (3) | |||

| Child Depression Inventory (CDI-SF) (2) | |||

| Spence Child Anxiety Scale (SCAS) (1) | |||

| Beck Youth Inventory - 2nd Ed. (1) | |||

| Cognitive/Neuropsychological | 18 | 13 | The Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions (BRIEF) (7) |

| Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (4) | |||

| Immediate Post-Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing (ImPACT) online (2) | |||

| Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning (WRAML) (1) | |||

| Delis-Kaplan Executive Functioning System (D-KEFS) (1) | |||

| TBI Knowledge | 6 | 7 | Concussion Knowledge CDC Health's Up concussion quiz (2) |

| Knowledge Interview for Children (KIC) (1) | |||

| mTBI Knowledge (1) | |||

| Parenting Skills/Experience | 4 | 6 | Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System (DPICS) (3) |

| Caregiver Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES) (2) | |||

| Family Functioning | 7 | 4 | Family Assessment Device (FAD) (2) |

| Family Burden of Injury Interview (FBII) (2) | |||

| Global | 2 | 2 | Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (2) |

| Short-Form 12-Item health Survey (SF-12) (1) |

Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (mTBI)

The majority of mTBI studies were conducted during emergency care; therefore, we described the education provided in the emergency department separately from the education provided in a rehabilitation center, community, or outpatient setting.

mTBI education/training during emergency care (n=18)

Eighteen studies focused on education or training provided to children or adolescents with mTBI or their family/caregivers during emergency care. Topics included symptom management, when to seek care, and returning to school or activities following discharge. Nine studies targeted education or training for children with TBI and family (17–25), seven targeted parents/caregivers (26–32), and two focused exclusively on providing education/training directly to children with TBI (33, 34). Four studies included adults with TBI (17, 20, 33, 34). One modified Delphi study (31) included children with TBI as well as those with other conditions, such as asthma, vomiting/diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, minor brain injury, and bronchiolitis.

Ten of the 18 studies used an experimental design (18, 21–25, 27, 28, 30, 32). Among those with experimental designs were five pre-post randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) with control (22, 23, 25, 28, 32), three case studies (18, 24, 30), one post-test only design with randomized control (27), and one post-test only design with non-randomized control (21). Seven of the 18 studies were survey practice studies (17, 19, 20, 29, 31, 33, 34), and one was a program description (26). The seven survey practice studies focused on identifying essential content for discharge instructions (DIs) (31), evaluating the content of existing DIs (17, 20, 29), examining the use of DIs (33), and evaluating both the content and use of DIs (19, 34).

The 18 studies varied in the setting and delivery of the education/training. A majority of the studies focused on education/training that was provided exclusively in the ED (17–21, 23–25, 27, 28, 30, 31, 33, 34), while the remainder focused on education/training in the ED and acute hospital settings (26, 29) and education/training in the ED and community/outpatient setting (22, 32). Regarding methods of education delivery, the majority of studies (n=15) provided written information. Nine studies delivered education/training in person, two studies provided follow-up education/training via telephone by an interventionist (23, 32), and one study provided education/training via the web/online (22).

Descriptions of mTBI education/training beyond emergency care (n=6)

Six studies focused on mTBI education/training beyond emergency care. Four studies described TBI-specific education, while two studies also included children or adolescents with ABI (35, 36). In one study (35), at least 50% of the children had a TBI while the other children were diagnosed with a brain tumor or cyst. Another study (36) did not explicitly state the sample’s injury type, but were most likely those with TBI based on the description of the injury characteristics. Five studies focused on education/training provided in the community or outpatient setting (35, 37–40), while one study focused on education/training that was provided at a children’s rehabilitation center and in the community following discharge (36).

All of the mTBI studies occurring outside of the ED used experimental designs. The designs included a pre-post design RCT with control (40), pre-post design without control (38, 39), an open pilot study (37), quasi-experimental design with a non-equivalent comparison group (36), and a case study (35). Three of the studies focused on education/training for children with TBI and their family (37–39), two included education/training for parents/caregivers of children with TBI only (35, 36), and one focused on education/training to help manage persistent post-concussive symptoms for youth aged 10–18 years with mTBI (40). Regarding delivery of the education, three studies provided written education. Of the four studies providing in-person education/training, two studies provided one-on-one education/training (36, 40) and two provided group educational sessions (35, 39). One study used a web-based intervention for adolescents aged 11–18 years with mTBI (37).

Effects of mTBI education/training on patient/family outcomes (n=9)

Nine studies reported on the effects of mTBI education/training on patient/family outcomes. Three RCTs examined the effects of education/training on outcomes (22, 25, 28). In an RCT by Olsson et al. (22), a child-focused education website and a parent psychoeducation booklet for the prevention of pediatric post-concussion symptoms was not more effective than receiving routine mTBI information. Another RCT (25) also did not find a novel ED symptom-guided DIs more effective than standard DIs. Caregivers found the novel DIs more helpful in deciding when their child could resume physical activity and school compared to the standard DIs (p < 0.05). In a more recent RCT (28), the authors recognized the need for culturally tailored and targeted videos for specific patient groups (i.e., ethnic minorities), and the need to adapt material for caregivers with limited English proficiency.

Using an open-label, single arm design (37), Babcock et al. examined the interactive, Web-based Self-Management Activity-restriction and Relaxation Training (SMART) program among adolescent/parent dyads. Adolescents with TBI showed a decrease in reported post-concussive symptoms, which stabilized after two weeks (41). Parents and adolescents found the information useful for monitoring mTBI recovery. Hunt et al. (39) examined the feasibility and knowledge uptake of children and youth with concussion and their families using a 90-minute educational session called “Concussion & You.” The authors concluded that is important to make information accessible, keep messages simple and consistent, promote sharing of experience, and provide tools and resources.

Warren and Kissoon (27) examined whether written DIs improved recall of signs and symptoms and increased parent satisfaction compared to standard verbal discharge explanations alone and found no differences. 84% of parents who received written instruction kept them for future reference; the authors speculated that the written instruction may provide reassurance to the parents, but should be written in simple language. Thomas et al. (30) found that verbal instructions with written instructions were more effective in improving recall than written instructions alone.

Hwang et al. (18) evaluated compliance with concussion DIs. Children with sports injuries were slightly more likely to be compliant with medical clearance; however, more than one-third reported returning to play on the day of the injury, suggesting that the DIs were either not read or ignored. In a non-randomized posttest study (21), providing an mTBI information booklet appeared to optimize early management of mTBI and reduce stress in both children and their parents.

Moderate-to-Severe TBI

Description of Moderate/Severe TBI Education/Training (n=18)

Eighteen studies focused on education/training for young people with moderate/severe brain injury. One study (42) did not specify the severity, but based on the education program described in the paper was likely designed for adolescents with moderate/severe ABI. Of these 18 studies, two included only those with severe injury (43, 44), whereas the remaining 16 included individuals with moderate/severe injuries. However, four studies also included a small sample of individuals with complicated mTBI. Eleven studies included individuals with only TBI and the seven remaining papers included both traumatic and non-traumatic brain injury in their sample.

Papers discussing education related to pediatric brain injury included a variety of experimental and non-experimental designs. Twelve of 18 studies included experimental designs to assess their educational programs. Six studies were RCTs with pre-post controls (43, 45–49), four studies used pre-post design without control (50–53), and two were case studies (44, 54). Six studies described an educational program (42, 55–59), two of which included key stakeholders in developing their educational programs (42, 59).

The target population, setting, and method of education provision varied across the 18 studies. Half of the papers described educational programs designed for the family only, and six programs provided education/training to the family and the child with TBI (42, 48, 49, 52, 53, 57). Three studies focused on education/training provided to the child only (43, 46, 54); however, one of these focused on educating/training children with both traumatic and non-traumatic injuries (46). Educational programs were applied across institutional and community settings. Two papers described education that crossed from hospital admission (e.g., acute care, rehabilitation unit) and into the community/outpatient services (56, 58). One paper covered the acute and rehabilitation stay (55), and two additional papers focused only on education/training provided during the inpatient rehabilitation admission (44, 59). Majority of the educational programs (n = 13) focused on community or outpatient settings.

The methods of education/training delivery focusing on moderate/severe TBI varied across the included papers. Seven used written education and nine incorporated web-based or online education delivery (45–49, 51–54). The remaining nine papers incorporated in-person education/training. Seven studies educated families and children in a one-on-one setting, two used education/training dyads, and two incorporated group educational programming.

Multi-component educational/training interventions for moderate/severe TBI (n=6)

Six articles reported data on multi-component educational/training interventions for children with moderate-to-severe TBI (44, 46, 48, 50, 52, 53). Wade and colleagues, in 2005, concluded that the multi-component web-based interventions that provided TBI information hold promise for improving outcomes in children with TBI (53). The same authors (48) suggested that a web-based cognitive-behavioral intervention, when compared receiving online resources, could improve older children’s self-management and adjustment after TBI, even among children who were economically disadvantaged.

In 2009, Wade et al. completed a survey to determine the acceptability of another family problem-solving intervention (52). Participants rated the program as moderate to high on helpfulness and ease of use, and reported that it increased targeted knowledge about their TBI (52). This intervention, called the Teen Online Problem-Solving program, was built upon the previous online family problem-solving intervention (48), but focused on self-monitoring, self-regulation, and social problem-solving skills. Another intervention, BrainSTARS (50), appeared to increase the competencies of parents and educators, but further study is needed on the impact on student performance and long-term findings. The BrainSTARS intervention is a consultation program with similar underlying intentions as the intervention of Wade et al.

The only study that concluded no additional benefits for the intervention group was that of Piovesana et al. (46), which utilized a multi-modal therapy program to improve executive function in children and adolescents with ABI. This RCT was developed because most interventions focus on a single aspect of executive functioning such as problem solving, rather than multiple components. Laheyet al. (44) used three pediatric cases to examine the role of the psychologist in psychoeducation and supportive interventions to facilitate family adjustment to the child’s TBI. This paper concluded that more research is needed to demonstrate the value of psychology in the rehabilitation process.

Effects of moderate/severe TBI education/training on patient/family outcomes (n=6)

Six studies tested the effects of TBI education/training on patient/family outcomes, of which four were RCTs (43, 45, 47, 49), one a pre-post without control (51) and one uncontrolled case study (54). Five different education/training interventions were evaluated. One study developed and tested an iPad application, Brain Games, to improve cognitive abilities among five adolescents with TBI with diffuse axonal injury (54). The study was deemed feasible, and cognitive improvements were retained or increased at long-term followup on a variety of cognitive measures. Another study tested the feasibility of the Internet-based Interacting Together Everyday: Recovery After Childhood TBI intervention (I-In TERACT) among parents of children with TBI (51). Combining web-based sessions with accompanying live coaching sessions appeared feasible and was enjoyable by parents, despite not reducing problem behaviors among children with TBI.

Three RCTs examined the effects of I-InTERACT by comparing it to either an abbreviated version (Express) and/or an active-control group, the Internet Resource Comparison (IRC) group (5, 47, 49). The IRC group received links to information on pediatric TBI and recovery. The authors concluded that parent training interventions post-TBI may be particularly valuable for lower-income parents who are vulnerable to both environmental and injury-related stresses. Similarly, Antonini et al. (45) found improvements in child behavior support, particularly for those with lower socioeconomic status. No group differences were found in caregiver psychological distress, stress, or self-efficacy (47, 60). From baseline to 6-month followup, the I-InTERACT significantly reduced both caregiver depression and the number of negative parenting behaviors (61). These studies suggest that the intervention is helpful for improving outcomes in children with TBI and their caregivers.

Providing links to pediatric TBI information (control group) was also compared to an online Counselor-Assisted Problem Solving intervention (CAPS group) in reducing caregiver depression and distress during the first 6 months following adolescent TBI (49). CAPS was not more effective than providing only internet resources. After re-analyzing the previous RCT data, adolescents in the CAPS group from married households had lower global adolescent emotional and behavioral functioning compared to those in the CAPS group from single parent households (62). In an older study, adolescents with severe TBI aged 9 to 16 years had limited TBI knowledge with a subset also demonstrating a lack of awareness (43). Authors suggest accounting for unawareness and providing repetition and visual cues to aid in retention of TBI-related information.

Discussion

Summary of Evidence

This systematic scoping review aimed to examine the types of TBI-related education or training developed for children and adolescents with TBI and their families/caregivers, as well as to determine the settings in which such education or training is provided. We sought to classify the types of outcomes and measures used to explore the effects of the TBI-related education or training for children and adolescents with TBI or their family members. Our findings indicate that greater efforts are needed to target education or training specifically to children or adolescents with TBI and for their siblings. Another gap revealed by this scoping review is related to the need to provide pediatric TBI education or training during acute care and inpatient rehabilitation hospitalization, where education may help support families during care transitions.

A notable challenge identified from this review is that it is difficult to determine the effects of TBI psychoeducation, particularly for multi-component interventions where the active ingredients of the intervention are unclear. This is evident with the mixed results on the effectiveness of solely providing education related to the consequences of TBI. For example, there have been improvements to providing pediatric DIs following the launch of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s HEADS UP campaign (19, 34). DIs helped parents with return-to-activities decision-making, but were not helpful in improving symptoms. Providing education may improve over all TBI knowledge, but without a control group, the intervention effectiveness is difficult to determine (39). Studies included in this review indicate that it is more effective to supplement written instructions with verbal instructions or multimedia instructions (28, 30). Most studies did not assess TBI-related knowledge and others created measures to evaluate comprehension of discharge instructions (28), concussion understanding (39), and recall of instructions (27), which makes it difficult to evaluate effects of the education provided.

We provide the following key points as a qualitative synthesis of the findings of this review:

Most pediatric TBI education/training was geared towards family members, most often parents. Few studies specifically provided education or training to children and adolescents with TBI to help them with managing their symptoms, and even fewer studies provided education/training to siblings. TBI education/training is rarely geared towards siblings to help them cope, be included in discussions, and address their fears (55, 59). Using a family-centered and community-based approach may be beneficial not only to address these concerns, but also to connect families to needed services (57).

Education/Training provided soon after an injury tended to focus on those with milder injuries, often in the form of written DIs. DIs seem to be effective when provided in the ED (54), especially since returning to the ED is tied to hospital quality metrics. TBI education should supplement information given by healthcare professionals but should not replace it. Timing of the education is an important factor (50, 58), as information needs can vary throughout the recovery process.

When developing TBI-related education/training, it is important to consider whether the content is understandable by both children and their families. Studies indicated concerns regarding the adequacy, consistency and evidence-based nature of the information provided to families about the consequences of TBI (20). Important content considerations include target population, the nature of the education, the essential topics, and the level of medical jargon used (56).

Children with sports-related injuries often received information regarding return to play or activities; however, those who sustained their injury from other means may not have been consistently provided with similar information (34). Most pediatric patients follow discharge instructions, but some return to play on the day of their injury (18), counter to medical recommendations. Further research is needed to determine what education/training components might be most effective in maintaining adherence to return-to-play restrictions.

Education provided in a variety of formats helped improve TBI-related knowledge or recall of instructions. Written instructions are helpful but may not be sufficient; however, when combined with strategies like videos, info graphics, and teach-back, their effectiveness increases (28, 30). Health literacy is oftentimes not addressed and should be considered by providing printed material using simple language, as well as video or pictorial information (58). The information should be culturally adapted for the target population, be representative of different racial/ethnic groups, and address the educational needs of children or adolescents with TBI and their families who may have limited English proficiency (54).

Few studies have examined self-management strategies, where psychoeducation is a key component, to help support children or adolescents with managing TBI-related symptoms and challenges, especially those with moderate-to-severe injuries who may have more long-term consequences of injury. The studies that used self-management approaches were most commonly targeting mTBI post-concussive symptoms, which often reduced symptom reporting among children or adolescents with TBI.

Interventions were rarely purely psychoeducational in nature, but often included multiple components, especially when targeting problem behaviors. Psychoeducation alone does not seem to be completely effective in changing behaviors or encouraging symptom reporting, but it can reduce stress (21) and in some cases improve knowledge or recall of TBI-information. However, few studies have been designed to truly examine the effects of providing TBI-education to improve outcomes for children or adolescents with TBI and their families/caregivers.

Use of technology was found feasible to educate families on behavioral problems following TBI, even among those with low-income (45, 51, 60), as it helped reduce time or distance barriers (52). Computer usage and the expertise of the caregivers or children/adolescents with TBI should be considered when developing an online TBI-education/training program (49). Other considerations include whether children with TBI may: have attention deficits that could interfere with attending to videoconferencing (53); have a qualified therapist to supplement online information (53); benefit from live synchronized education via live coaching with an online program, such as Skype (61); and have any potential internet connectivity and technological issues that may make it challenging for children or adolescents with TBI to engage in programs (46). Sending emails and text-messages have helped with making sure teens are engaged in and complete educational programs (52).

Limitations

Given that we used the search strategy from the previous review (12), only English-language studies were included. The studies varied in purpose, content, delivery, frequency, and intensity; therefore, it is difficult to assess the true effects of providing pediatric TBI education/training. The included studies often used measures developed by the authors. The included studies also varied in the sample population, education type, or lacked a control group, which would pose a challenge with conducting a systematic review and potential meta-analysis to determine the effects of pediatric TBI educational or training interventions and its key ingredients. We also noted that a limited number of researchers have contributed to the literature; therefore, the results are more reflective of their work with a specific group of participants versus a diverse sampling across multiple study sites and groups. Lastly, we completed our review in 2018; therefore, our review does not reflect the increased use of technology and web-based platforms to provide education and training during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Recommendations for Future Work

The summary of past research included in this review provides directions for future, prospective work. Much of the research thus far has focused on education/training provided in the ED or community/outpatient settings. Especially for children with moderate-to-severe TBI, research should examine educational programming provided to children during acute or inpatient rehabilitation hospital stays, as some of these children are likely to face long-term challenges following their TBI. Additionally, the acute care/rehabilitation setting provides an opportunity for interactions with multiple medical/clinical professionals who can provide training to youth and their families. Educational programs provided to siblings of children with TBI are needed to help address the known effects a TBI has on an entire family unit. Research focusing on return-to-play, thus far, has largely focused on sports-related injuries. Yet, many children experience a TBI outside of organized sports and future research should focus on investigating the essential elements needed to maintain safety and optimize recovery in youth with non-sports-related mTBI.

Ultimately, research must continue to evaluate how successful education provision or training to children with TBI and their families/caregivers can help to promote improved long-term outcomes. Researchers and clinicians should focus on the inclusion of common outcome measures, such as the use of CDEs, across studies to determine what elements of an educational program are most effective in helping to improve knowledge about TBI, promote symptom management, and address the long-term needs of survivors and families. To address social determinants of health that may affect the success of educational provision, researchers should attend to important variables such as health literacy, English proficiency, cultural identity, educational attainment, and socioeconomic status when planning prospective studies.

Conclusion

After examining the existing literature, we concluded that education/training focusing on the consequences of pediatric TBI was: (a) mostly geared toward parents, (b) developed for those with milder injuries, (c) in the form of written DIs, (d) often inadequate and not evidenced-based, and (e) included multiple components. The results of this scoping review will guide future research and intervention development to encourage better management of the consequences of pediatric TBI.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Roxann Grover O’Day, MA for developing all tables and figures for reporting and Sarah Toombs Smith, PhD, ELS for editing this manuscript.

Funding:

The contents of this publication were developed under grants from the National Institute on Aging [NIA grants number K01AG065492; P30AG024832; P30AG059301], the National Institutes of Health [NIH grant number K12HD0055929], the NIH-funded National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences [NIH grant number UL1TR001439], and the National Institute for Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research [NIDILRR grants number 90DPTB0016, 90DP0012] with the Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center at the American Institutes for Research. NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The views, opinions, and/or findings contained in this article are those of the authors and should not be construed as an official institutional position or any other federal agency, policy, or decision unless so designated by other official documentation. The contents of this publication do not necessarily represent the policy of the NIH, ACL or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

Appendix 1: Database Search Strategies

| Database | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| Campbell Library PROSPERO PsycBITE | Title field search using the following terms, as well as reviewing the results to find relevant publications on the key topics: education, training, or instruction: |

| brain injury | |

| brain injuries | |

| concussion | |

| concussions | |

| head injury | |

| head injuries | |

| Postconcussion | |

| Post-concussion | |

| Postconcussive | |

| Post-concussive | |

| The Review Title field was searched to find relevant publications on education, training, or instruction: | |

| brain injury | |

| brain injuries | |

| concussion | |

| head injury | |

| head injuries | |

| • Neurological Group: Traumatic brain injury (TBI)/Head injury AND Intervention: Education/Psychoeducation/Bibliotherapy | |

| • Neurological Group: Traumatic brain injury (TBI)/Head injury AND Intervention: Family Support | |

| • Neurological Group: Traumatic brain injury (TBI)/Head injury AND Keywords: “patient education” | |

| • Neurological Group: Traumatic brain injury (TBI)/Head injury AND Keywords: “caregiver education” | |

| • Neurological Group: Traumatic brain injury (TBI)/Head injury AND Keywords: “family education” | |

| • Neurological Group: Traumatic brain injury (TBI)/Head injury AND Keywords: “patient information” | |

| • Neurological Group: Traumatic brain injury (TBI)/Head injury AND Keywords: “patient training” | |

| • Neurological Group: Traumatic brain injury (TBI)/Head injury AND Keywords: “caregiver training” | |

| • Neurological Group: Traumatic brain injury (TBI)/Head injury AND Keywords: Psychoeducation | |

| • Neurological Group: Traumatic brain injury (TBI)/Head injury AND Keywords: Psychoeducational | |

| • Neurological Group: Traumatic brain injury (TBI)/Head injury AND Keywords: “self management” | |

|

CINAHL (EBSCO)

PsycINFO (EBSCO) |

(MH “Brain Injuries+” OR MH “Brain Concussion+” OR MH “Postconcussion Syndrome” OR “brain injury” OR “brain injuries” OR “brain injured” OR TBI OR “head injury” OR “head injuries” OR concussi* OR Postconcussi* OR Post-concussi*) AND (TI Educat* OR MH “Caregivers/ED” OR MH “Patient Education+” OR MH “Family+/ED” OR MH “Health Education+” OR MH “Consumer Health Information” OR TI teach* OR TI train* OR TI instruct* OR TI information OR TI program* OR TI programme* OR psychoeducation* OR psycho-education* OR MH “Psychoeducation” OR “self management” OR MH “Self Care+”) English language (DE “Traumatic Brain Injury” OR DE “Brain Concussion” OR “brain injury” OR “brain injuries” OR “brain injured” OR TI TBI OR “head injury” OR “head injuries” OR concussi* OR Postconcussi* OR Postconcussi*) AND (TI Educat* OR DE “Client Education” OR “patient education” OR “family education” OR “caregiver education” OR DE “Health Education” OR DE “Drug Education” OR DE “Sex Education” OR TI “teach” OR TI “teaching” OR TI “training” OR TI “instruction” OR TI “instructions” OR TI “program” OR TI “programs” OR TI “programmes” OR TI “programme” OR psychoeducation* OR psycho-education* OR DE “Psychoeducation” OR “self management”) English language |

| Cochrane Library (Wiley) | Line # Search terms |

| #1 MeSH descriptor: [Brain Injuries] explode all trees | |

| #2 MeSH descriptor: [Brain Concussion] explode all trees | |

| #3 MeSH descriptor: [Post-Concussion Syndrome] explode all trees | |

| #4 (Traumatic brain injur* or brain injur* or TBI or head injur* or concussi* or Postconcussi* or Postconcussi*):ti,ab,kw | |

| #5 MeSH descriptor: [Caregivers] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Education - ED] | |

| #6 MeSH descriptor: [Patient Education as Topic] explode all trees | |

| #7 MeSH descriptor: [Health Education] explode all trees | |

| #8 MeSH descriptor: [Consumer Health Information] explode all trees | |

| #9 MeSH descriptor: [Psychotherapy] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Education - ED] | |

| #10 MeSH descriptor: [Self Care] explode all trees | |

| #11 (Educat* or teach* or train* or instruct* or information or program* or programme*):ti | |

| #12 (psychoeducation* or psycho-education* or “self management"):ti,ab,kw | |

| #13 (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4) | |

| #14 (#5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12) | |

| #15 #13 and #14 | |

| ERABI | An online comprehensive review of scientific literature on ABI rehabilitation in the acute and post-acute phase of recovery to identify rehabilitation interventions. We reviewed to locate relevant literature on TBI and education/training. |