INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has strained workforces and magnified systemic challenges and many hospital medicine groups have therefore created interventions to address physician wellness and burnout. In this paper, we describe the national landscape for hospital medicine wellness interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic as assessed and studied by the Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN) Wellness Working Group1 and identify potential gaps to target in continuation of wellness efforts during the evolution of the pandemic and beyond.

METHODS

Between May 2020 and October 2021, the HOMERuN Provider Wellness working group surveyed all 50 HOMERuN institutions across the country about wellness offerings and 26 sites responded (52% response rate). The survey was adapted from the framework outlined in the Press-Ganey tool “Caring for Caregivers: A Leadership Checklist,”2 and wellness offerings were categorized using this framework into (1) protective strategies, designed to meet basic safety, operational and clinical needs, and (2) emotional support strategies geared toward addressing provider mental health and stress burden. Then the working group conducted 4 focus groups with representative members from the broader HOMERuN group to further probe wellness trends and best practices—specifically gaps, barriers, new wellness roles, and which offerings persisted 18 months into the pandemic. Findings from both the survey and focus groups were thematically organized into cohesive wellness best practices by workgroup members.

RESULTS

Protective Strategies

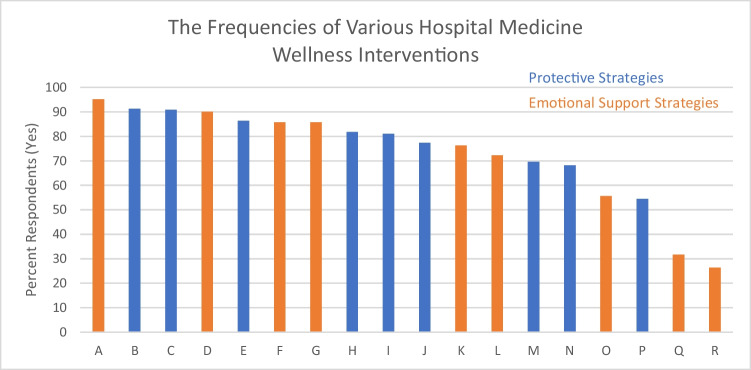

With regard to safety and basic operational needs, results (Fig. 1) showed wide adoption of guidelines to assist with triaging, isolating patients, workplace safety, and optimizing employee health (54.55–91.3%). Of note, 77% of sites surveyed endorsed adequate access to personal protective equipment early in the pandemic.

Figure 1.

The frequencies of various hospital medicine wellness interventions. Protective strategies and emotional support strategies. N = 26. A, Transparent and frequent COVID-related communication; B, Alteration in inpatient scheduling; C, Implementation of new guidelines to reduce transmission (e.g., universal masking, limiting the number of people on the elevator); D, Guidelines and/or offerings to reduce family exposure (e.g., hotel offering); E, Transparent and clear return to work guidelines; F, Wellness resource offerings (e.g., nutrition, sleep); G, Anxiety reduction strategies and resources; H, Available and updated COVID-related patient care instruction; I, Use of triaging and/or quarantining protocols; J, Access to adequate personal protective equipment (PPE), including N95 masks; K, Increased mental health resources/Employee Assistance Program (EAP); L, Transparent communication re: COVID-related individual financial impact; M, Inpatient use of telemedicine to limit patient contact; N, Healthcare worker re-deployment (non-hospitalist); O, Childcare and/or Eldercare resources; P, Increased use of ancillary and/or consultant services; Q, Direct assessment of stressors and/or wellness needs; R, Support offerings for families of caregivers.

Compared to other protective wellness initiatives, there were lower reported rates of inpatient telehealth (70%), redeployment of non-hospitalist physicians (70%), and increased of use ancillary or consult service support (50%).

Emotional Support Strategies

Compared to protective strategies, there was increased variability in the frequency of emotional support strategy wellness offerings (Figure). While there were high reported rates of COVID-related communication (95%), wellness resource offerings (85%), anxiety reduction strategies (85%), and guidelines to reduce family exposure (90%), there were much lower rates of childcare/eldercare offerings (55%), support for families of caregivers (26%), and direct assessment of stressors and/or wellness needs (31%).

DISCUSSION

Our evaluation of wellness offerings of diverse academic hospital medicine groups across the country in response to the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated generally widespread adoption of protective strategy offerings, with more variable emotional support strategy offerings.

As supported by the Press Ganey “Caring for Caregivers” framework used for this study, protective strategy offerings are the necessary foundation for addressing provider wellness. Crucial protective strategies, such as access to PPE, were arguably under-implemented, as they did not achieve 100% frequency in reported availability. Additionally, other measures that may help to protect against physician burnout, such as alterations in scheduling3, staffing support through redeployment of other healthcare workers, and maximizing ancillary/consult services were under-utilized compared to other strategies. One potential reason for this is that these interventions require greater resources for adoption and implementation.

The variability in emotional support strategy offerings was notable for decreased frequency of childcare/eldercare resources and family support as compared to other offerings. This is seemingly a mismatch in available wellness offerings as compared to primary reported stressors during the pandemic including the stresses of child and eldercare, supported by the fact that more physicians have converted to part-time or are leaving clinical medicine altogether in response to the pandemic.4 More importantly, only a small minority of groups did a direct assessment of the wellness needs of their faculty to help target wellness offerings to reported greatest needs.

CONCLUSIONS

Best Practices for Hospital Medicine Programs-CARES

Our work provides the basis for some key recommendations for academic hospital medicine groups as they strive to address provider wellness during the COVID-19 pandemic and future challenges that may affect hospitalists. We have utilized the results of our national survey to develop the Best Practices for Hospital Medicine Programs CARES model to target gaps we identified in provider wellness offerings (Table 1). The model promotes checklist utilization, direct surveying of your team, increasing support to hospitalists who are caregivers, evaluating the impact of offerings, and ensuring basic personal protective measures are fully met.

Table 1.

Best Practices for Hospital Medicine Programs-CARES

| Checklist | Utilize a structured framework to help organize wellness interventions. We recommend the Press Ganey Wellness Checklist as one option. https://info.pressganey.com/press-ganey-blog-healthcare-experience-insights/caring-for-caregivers-a-leadership-checklist |

| Assessment | Survey your providers to identify primary stressors and wellness needs. Use these results to directly target wellness offerings to achieve highest yield interventions |

| Relationship |

Ensure wellness offerings include addressing the unique needs of providers who are also primary caregivers, including child and eldercare resources Provide additional resources for counseling and support to families |

| Evaluation | Evaluate the utilization and impact of wellness offerings to determine which offerings are most impactful and identify targets for improvement |

| Safety needs | Ensure “safety musts” are provided, including 100% access to basic personal protection needs such as adequate PPE, mental health offerings, and others as identified |

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Tejal Gandhi MD MPH CPPS and the HOMERuN COVID-19 Collaborative.

Declarations:

Conflict of Interest:

Elizabeth Murphy received a consulting fee for the creation of an online learning module regarding transitions of care for the ACP online leadership course and is paid consulting fees by ACP for the facilitation of a leadership course. Neither poses a conflict of interest for this article.

The remaining authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Auerbach AD, Patel MS, Metlay JP, et al. The Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN): a learning organization focused on improving hospital care. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):415-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Press Ganey “Caring for Caregivers” Checklist https://info.pressganey.com/press-ganey-blog-healthcare-experienceinsights/caring-for-caregivers-a-leadership-checklist. Accessed 2/7/2023.

- 3.Pierce RG, Diaz M, Kneeland P. Optimizing well‐being, practice culture, and professional thriving in an era of turbulence. J Hosp Med. 2019;14.2: 126–128. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Sheather J, Slattery D. The great resignation—how do we support and retain staff already stretched to their limit?. BMJ. 2021;375. [DOI] [PubMed]