Abstract

Background and aim

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) coinfection with other respiratory pathogens poses a serious concern that can complicate diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Since COVID-19 and tuberculosis are both severe respiratory infections, their symptoms may overlap and even increase mortality in case of coinfection. The current study aimed to investigate the coinfection of tuberculosis and COVID-19 worldwide through a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

A systematic literature search based on the Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” (PRISMA) was performed on September 28, 2021, for original research articles published in PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase databases from December 2019 to September 2021 using relevant keywords. Data analysis was performed using Stata 14 software.

Results

The final evaluation included 18 prevalence studies with 5843 patients with COVID-19 and 101 patients with COVID-19 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis). The prevalence of tuberculosis infection was 1.1% in patients with confirmed COVID-19. This coinfection among patients with COVID-19 was 3.6% in Africa, 1.5% in Asia, and 1.1% in America. Eighteen case reports and 57 case series were also selected. Eighty-nine adults (67 men and 22 women) with a mean age of 45.14 years had concurrent infections with tuberculosis. The most common clinical manifestations were fever, cough, and weight loss. A total of 20.83% of evaluated patients died, whereas 65.62% recovered. Lopinavir/ritonavir was the most widely used antiviral drug for 10.41% of patients.

Conclusion

COVID-19 has a low prevalence of tuberculosis coinfection, but it remains a critical issue, especially for high-risk individuals. The exact rate of simultaneous tuberculosis in COVID-19 patients could not be reported since we didn't have access to all data worldwide. Therefore, further studies in this field are strongly recommended.

Keywords: COVID-19, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Coinfection, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

1. Introduction

The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causing the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China, which was first identified at the end of 2019, sparked a global outbreak of the disease and is a major public health concern [1]. By January 2022, approximately 5.5 million people had lost their lives due to COVID-19 [2]. Droplets and contact with an infected person easily spread the virus. Symptoms of the disease are usually fever and cough, but it can also cause symptoms of muscle pain (myalgia), diarrhea, vomiting, and shortness of breath (dyspnea) in patients [3]. It puts the elderly and people with underlying diseases at greater risk for severe forms of the disease and mortality [4]. Accurate identification of COVID-19 is crucial because it leads to the control and prevention of infection in the community and appropriate and timely treatment measures in patients [5]. Coinfection in COVID-19 is an essential issue because it may create problems for the medical staff in diagnosing, treating, and prognosis of COVID-19. Therefore, concomitant infections must be carefully identified [6,7]. One of the pathogens that can cause coinfection in COVID-19 is Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis), which is the cause of tuberculosis [8]. Tuberculosis is an infectious disease that, like COVID-19, is transmitted through the respiratory tract and affects the lungs [9]. Concomitant COVID-19 and tuberculosis infection make the diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 more challenging, increasing mortality and non-recovery risks [10,11]. Based on WHO reports, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, years of progress in providing essential TB services to patients and reducing the burden of TB disease have been reversed [12]. Despite successes in some countries and regions, global TB targets are largely off track. Globally, there has been a large drop in the number of newly diagnosed and reported cases of TB. In 2020, TB cases fell from 7.1 million in 2019 to 5.8 million [12]. 93% of this reduction was accounted for by 16 countries, with India, Indonesia, and the Philippines suffering the most [13]. The reduction in the number of people treated for drug-resistant tuberculosis (−15%) and TB preventive treatment (−21%) is another impact, and a decline in global spending on TB diagnostic, treatment, and prevention services (from US$ 5.8 billion to US$ 5.3 billion) [13]. In such a situation, the co-occurrence of COVID-19 in TB patients can pose more risks. Numerous studies have been performed on coinfection with COVID-19 and tuberculosis since the onset of the new coronavirus pandemic worldwide [[14], [15], [16]]. However, a systematic review study has yet to be conducted to summarize the complete information on these patients, including symptoms, medications, laboratory findings, and chest CT scans. Given this issue's importance, this study's purpose was to systematically review articles related to coinfection with COVID-19 and M. tuberculosis (Active or Latent) and then to analyze the data.

2. Methods

We conducted the current review and meta-analysis under the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” (PRISMA) [17].

2.1. Search strategy and study selection

PubMed (MEDLINE), Web of Science, and Embase, the most important electronic databases, were searched on September 28, 2019, to identify relevant studies published in English between December 2019 and September 2021. The following keywords were used: (“COVID-19” [Title/Abstract] OR “novel coronavirus 2019” [Title/Abstract] OR “2019 ncov” [Title/Abstract] OR “nCoV” [Title/Abstract] OR “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2” [Title/Abstract] OR “SARS-CoV-2” [Title/Abstract]) AND (“Tuberculosis” [Title/Abstract] OR “Mycobacterium tuberculosis” [MeSH Terms] OR “TB” [Title/Abstract] OR “M. tuberculosis” [Title/Abstract]). A review of references within covered studies was also done to ensure that relevant publications were noticed. Two investigators independently checked this process. The PICO algorithm was adopted to define inclusion and exclusion criteria for study selection. Accordingly, we evaluated the data on P (Patient, Population, or Problem) = patients with COVID-19, I (Intervention or exposure) = M. tuberculosis infection, C (Comparison) = not applicable, and O (Outcome) = coinfection outcome of COVID-19 and tuberculosis. All clinical studies investigating the presence of M. tuberculosis infection in patients with COVID-19 were selected, articles that reported only the prevalence of COVID-19 or tuberculosis alone, review articles, abstracts presented in conferences, and duplicate studies were excluded. Relevant prevalence studies, case reports, and case series were further evaluated. Afterward, two investigators screened the titles and abstracts of all selected papers. Next, all selected articles were reviewed in their entirety. Review authors discussed and resolved discrepancies in the article selection or technical uncertainties.

2.2. Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed by extracting the first author's name, the year of publication, the type of study, the country where the study took place, the age and gender of patients, the number of confirmed COVID-19 patients, and the number of tuberculosis coinfected patients. Two authors independently recorded the data to avoid any bias.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Stata software was used for the statistical analysis (version 14, IC; STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). The pooled proportion of coinfected patients was estimated. The pooled frequency with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was assessed. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 method. Cochran's Q and the I2 statistic were used to determine between-study heterogeneity.

3. Results

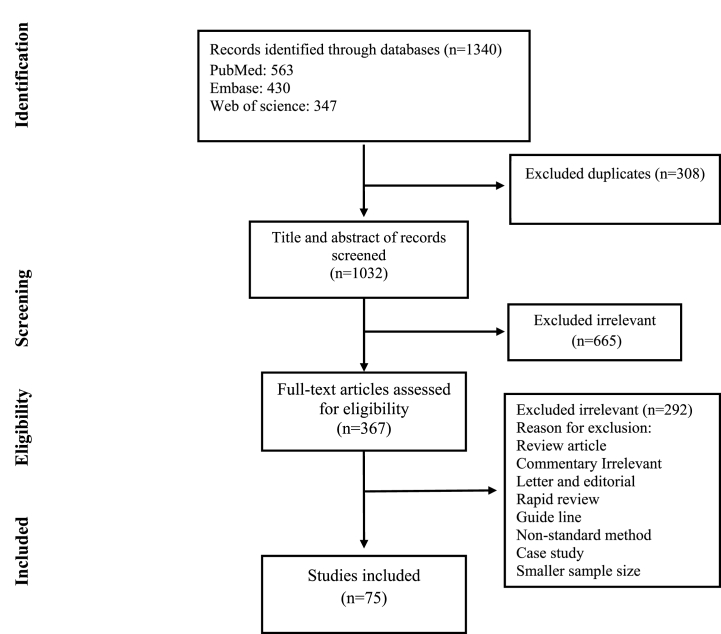

Initial searching yielded 1340 articles; duplicates were removed to leave 1032 for the secondary screening. A total of 665 articles were excluded after the title and abstract screening. Review articles, duplicate papers, systematic reviews, unrelated articles, and articles published in languages other than English were excluded from the review process. After reviewing the full text of the studies, eventually, 75 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1). Eighteen prevalence studies and 75 case reports/series were included in the final selection. The characteristics of the articles are summarized in Table 1, Table 2.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study selection for inclusion in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included prevalence studies.

| First author | Published time | Country | Patients with COVID-19 | Patients with COVID-19-TB | Mean age | Male/Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li [1] | June 2020 | China | 18 | 1 | nr | nr |

| Xu [2] | Apr 2020 | China | 23 | 1 | nr | nr |

| Himwaze [3] | May 2021 | Africa | 29 | 3 | 44 | 2 M/1 F |

| Goel [4] | March 2021 | India | 35 | 1 | nr | nr |

| Medina [5] | July 2021 | Guatemala | 44 | 1 | nr | nr |

| Niang [6] | Oct 2020 | Senegal | 47 | 3 | nr | nr |

| Guan [7] | March 2020 | China | 53 | 2 | nr | nr |

| Sun [8] | Aug 2020 | USA | 63 | 1 | nr | nr |

| Lai [9] | May 2020 | China | 110 | 1 | nr | nr |

| Li [10] | Feb 2021 | China | 125 | 3 | nr | nr |

| Van der Zalm [11] | Jun 2021 | South Africa | 159 | 7 | nr | nr |

| Sahu [12] | Jan 2021 | India | 218 | 1 | nr | nr |

| Rosenberg [13] | March 2020 | USA | 229 | 1 | 84 | 1 M |

| Lu [14] | May 2020 | China | 270 | 16 | nr | nr |

| Mithal [15] | Feb 2021 | India | 401 | 2 | nr | nr |

| Mafort [16] | Apr 2021 | Brazil | 447 | 4 | nr | nr |

| Gupta [17] | Oct 2020 | India | 1073 | 22 | 36 | nr |

| Lagrutta [18] | Jan 2021 | Argentina | 2499 | 31 | nr | nr |

| Total | 5843 | 101 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of included case report/case series.

| First author | Published time | Country | patients with COVID-19 | patients with COVID-19 -TB | Mean age | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Widiasari [19] | Nov 2020 | Indonesia | 2 | 1 | 43 | 1 F |

| Patil [20] | Jun 2021 | India | 1 | 1 | 75 | 1 M |

| Agada [21] | Feb 2021 | Nigeria | 1 | 1 | nr | 1 M |

| Adekanmi [22] | Nov 2020 | Nigeria | 3 | 2 | 65 | 2 M |

| Aissaou [23] | Aug 2021 | French | 1 | 1 | 30 | 1 M |

| Singh [24] | March 2021 | India | 9 | 3 | nr | nr |

| Sasson [25] | Dec 2020 | USA | 1 | 1 | 44 | 1 M |

| Bouaré [26] | July 2020 | Morocco | 1 | 1 | 32 | 1 F |

| Castillo [27] | Aug 2020 | Germany | 1 | 1 | 64 | nr |

| Dyachenko [28] | May 2021 | Ukraine | 1 | 1 | 44 | 1 F |

| Fahad Faqihi [29] | July 2020 | Saudi Arabia | 1 | 1 | 60 | 1 M |

| Essajee [30] | Aug 2020 | South Africa | 1 | 1 | 2 years and 7 months | 1 F |

| Ata [31] | Aug 2020 | India | 1 | 1 | 28 | 1 M |

| Gbenga [32] | Oct 2020 | Nigeria | 2 | 2 | 31 | 2 M |

| Gennaro [33] | March 2021 | Italy | 4 | 4 | nr | nr |

| Ghodrati Fard [34] | Feb 2021 | Iran | 3 | 3 | 35.6 | 3 M |

| He [35] | Sep 2020 | China | 3 | 3 | 56.3 | 3 M |

| Ridgway [36] | Jul 2020 | USA | 5 | 1 | 51 | 1 F |

| Orozco [37] | Nov 2020 | Mexico | 1 | 1 | 41 | 1 M |

| Farias [38] | Oct 2020 | Brazil | 2 | 2 | 41 | 2 M |

| Lopinto [39] | Sep 2020 | France | 1 | 1 | 58 | 1 M |

| Musso [40] | Jan 2021 | Moldova | 1 | 1 | 45 | 1 M |

| Luciani [41] | Oct 2021 | Italy | 1 | 1 | 32 | 1 F |

| Alkhateeb [42] | Nov 2020 | Qatar | 1 | 1 | 28 | 1 M |

| Khayat [43] | Jan 2021 | Saudi Arabia | 1 | 1 | 40 | 1 F |

| Elziny [44] | May 2021 | Nepal | 1 | 1 | 29 | 1 M |

| Baskara [45] | Feb 2021 | Indonesia | 1 | 1 | 42 | 1 M |

| Mulale [46] | March 2021 | South Africa | 1 | 1 | 3 months | 1 M |

| Rivas [47] | Oct 2020 | Panama | 2 | 2 | 41 | 2 M |

| Ntshalintshali [48] | Mar 2021 | South Africa | 1 | 1 | 65 | 1 M |

| Çınar [49] | Oct 2020 | Turkey | 1 | 1 | 55 | 1 M |

| Goussard [50] | Aug 2020 | South Africa | 1 | 1 | 3 years | 1 F |

| Goussard [51] | Jul 2020 | South Africa | 1 | 1 | 2 year and 5 months | 1 M |

| Pinheiro [52] | Oct 2020 | Brazil | 1 | 1 | 68 | 1 M |

| Saraceni [53] | Jun 2020 | Italy | 1 | 1 | 59 | 1 M |

| Sarınoğlu [54] | July 2020 | Turkey | 2 | 2 | 58 | 2 F |

| Segrelles-Calvo [55] | Apr 2021 | Spain | 1 | 1 | 58 | 1 M |

| Shabrawishi [56] | Apr 2021 | Saudi Arabia | 7 | 7 | 35 | 4 M/3 F |

| Gerstein [57] | Feb 2021 | El Salvador | 1 | 1 | 49 | 1 M |

| Dakhlia [58] | Sep 2021 | Qatar | 1 | 1 | 34 | 1 M |

| Singh [59] | Aug 2020 | India | 1 | 1 | 76 | 1 F |

| Pillay [60] | Jan 2021 | Durban | 1 | 1 | 44 | 1 F |

| Srivastava [61] | May 2021 | India | 7 | 7 | 60 | 4 M/3 F |

| Vilbrun [62] | Nov 2020 | USA | 1 | 1 | 26 | 1 M |

| Stjepanović [63] | Jan 2021 | Serbia | 1 | 1 | 27 | 1 M |

| Subramanian [64] | March 2021 | India | 1 | 1 | 30 | 1 F |

| Tham [65] | Nov 2021 | Bangladesh | 1 | 1 | 40 | 1 M |

| Tham [65] | Nov 2020 | India | 3 | 3 | 29 | 3 M |

| Cutler [66] | Jul 2020 | USA | 1 | 1 | 61 | 1 M |

| Sarma [67] | Nov 2020 | India | 1 | 1 | 53 | 1 F |

| Verma [68] | Nov 2020 | India | 4 | 4 | 35.5 | 3 M/1 F |

| Wong [69] | Nov 2020 | Singapore | 1 | 1 | 47 | 1 M |

| Ortiz-Martinez [70] | Jun 2021 | Colombia | 1 | 1 | 34 | 1 F |

| Yadav [71] | Aug 2020 | India | 1 | 1 | 43 | 1 M |

| Yao [72] | Nov 2021 | China | 3 | 3 | 50 | 3 M |

| Zhang [73] | Sep 2020 | China | 7 | 1 | 75 | 1 M |

| Yousaf [74] | Sep 2020 | Nepal | 2 | 2 | 33 | 2 M |

| Yousaf [74] | Sep 2020 | India | 2 | 2 | 38.5 | 2 M |

| Yousaf [74] | Sep 2020 | Bangladesh | 2 | 2 | 35 | 2 M |

| ВОРОБЬЕВА [75] | May 2021 | Russia | 1 | 1 | 55 | 1 M |

| Total | 114 | 96 |

3.1. Prevalence studies

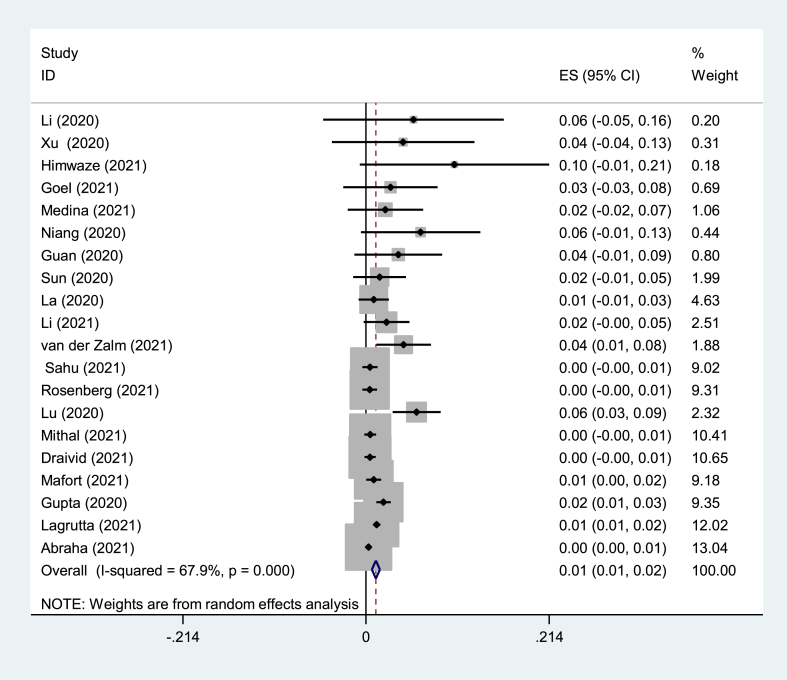

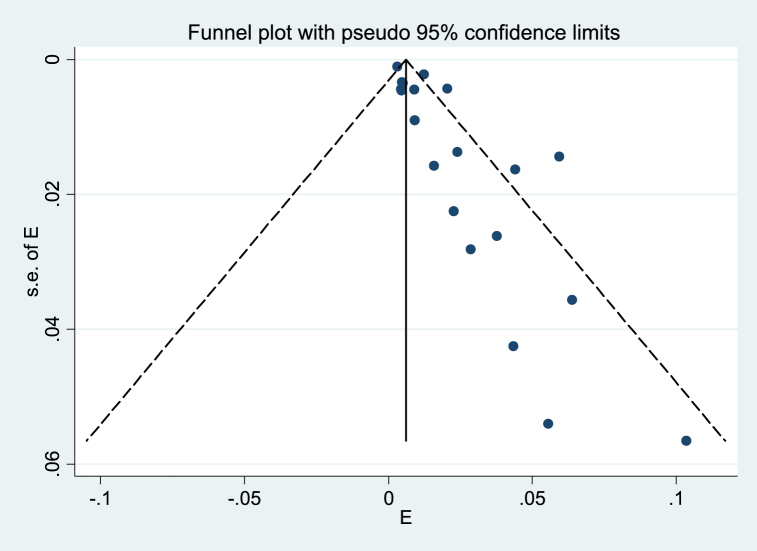

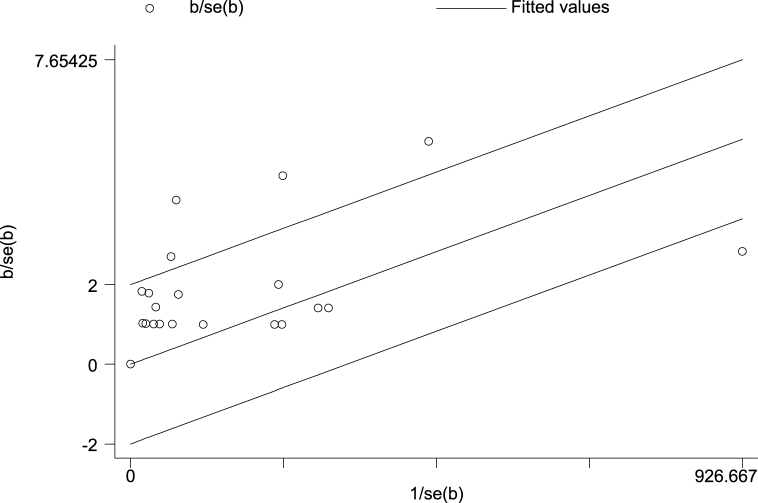

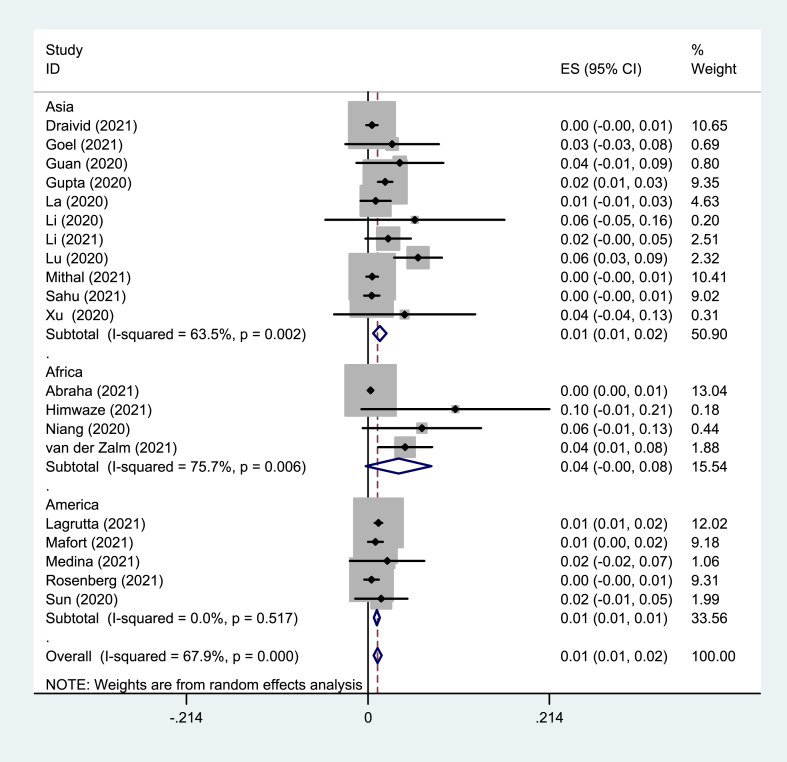

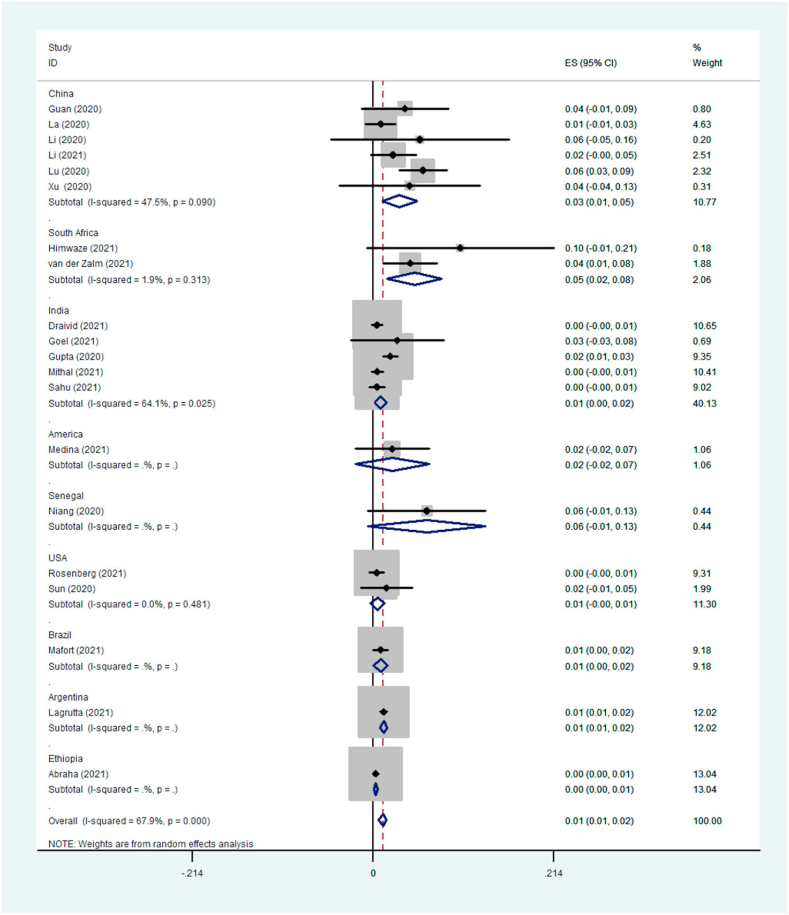

Eighteen prevalence studies were evaluated in the present review, six reported from China (33%), four from India (22%), two from the USA (11%), and Argentina, Brazil, Guatemala, Senegal, South Africa, and Zambia each reported one study (5%). These studies had 5843 participants with COVID-19, of which 101 patients had TB coinfection. The pooled prevalence of TB coinfection among patients with COVID-19 was 1.1% (95% CI: 67.9). The meta-analysis of prevalence studies revealed that the frequency of TB coinfection among patients with COVID-19 was 1.5% (95% CI 0.7–2.3) in Asia (10 studies, 50 patients), 3.6% (95% CI 0.2–7.5) in Africa (3 studies, 13 patients) and 1.1% (95% CI 0.7–1.4) from the America continent (5 studies, 38 patients). When this study was conducted, there were no reports of coinfection with TB in patients with COVID-19 from Europe or Oceania (Table 3). The related analysis included a forest plot, funnel plot, and Galbraith of the meta-analysis on the prevalence of TB among patients with COVID-19, provided in Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6.

Table 3.

Frequency of TB infection among patients with COVID-19 based on different subgroups.

| patients with COVID-19 and TB | Prevalence% (95% CI) | Number of studies | Number of patients | I-squared | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 1.1 (0.7–1.6) | 18 | 101 | 67.9 | |

| Continent | America | 1.1 (0.7–1.4) | 5 | 38 | 0.0% |

| Asia | 1.5 (0.7–2.3) | 10 | 50 | 63.3% | |

| Africa | 3.6 (−0.2-7.5) | 3 | 13 | 75.5% | |

| Country | China | 3.1 (1.1–5.2) | 6 | 24 | 47.5% |

| India | 0.9 (0.2–1.6) | 4 | 26 | 64.1% | |

| USA | 0.6 (−0.2–1.4) | 2 | 2 | 0.0% | |

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis on the prevalence of TB among patients with COVID-19.

Fig. 3.

Funnel plot of the meta-analysis on the prevalence of TB among patients with COVID-19. Solid circles represent each study in the meta-analysis.

Fig. 4.

Galbraith of the meta-analysis on the prevalence of TB among patients with COVID-19.

Fig. 5.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis on the prevalence of TB among patients with COVID-19 based on continents.

Fig. 6.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis on the prevalence of TB among patients with COVID-19 based on countries.

3.2. Case reports/case series studies

Eighteen case reports (96 patients) and 57 case series (101 patients) highlighted tuberculosis coinfection in 43 and 53 COVID-19 patients, respectively. Of these 96 patients (i.e., 22 female, 67 male, and seven were not reported), the population of men was almost three times that of women. Except for patients whose mean age was not reported (8 patients) and non-adult ones (4 patients), the mean age of adult patients was 45.14 years. Table 4 provides details about these studies; as can be seen, diabetes (15.62%) and hypertension (8.3%) were among the most prevalent comorbidities of coinfected patients. Chronic kidney disease, with a prevalence of 6.25%, was the third most common comorbidity in these patients. According to details regarding concurrent infections, HIV (11.45%) was the most common infection among coinfected patients. Clinical symptoms were also examined in COVID-19 and TB coinfected patients. Fever, cough, and weight loss were the most common clinical manifestations reported in this group of patients, with a frequency of 66.66, 56.25, and 22.91%, respectively. Based on the results of included studies, the real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) (56.25%), chest x-ray (CXR) (35.41%), and computed tomography (CT) scan (32.29%) were the most common diagnostic method for COVID-19. Acid-fast bacillus (AFB) testing (30.20%) was the most common diagnostic method for TB (Table 5). According to the laboratory findings reported in the evaluated articles, elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) (45.83%), lymphopenia (25%), and elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (25%) were the most commonly reported findings, respectively. Monocytosis was the least reported abnormality (Table 4). The type of tuberculosis was also evaluated in case reports/case series studies, of which 17 studies reported the active type and six reported the latent type. It was also found that the most common presentation of TB in coinfected patients was pulmonary involvement in 14 studies. The outcomes of COVID-19 and TB coinfection were reported in 52 studies. According to them, 20 of 96 patients died (20.83%), and 63 out of 96 patients recovered (65.62%) (Table 4). There were three treatment groups for patients with COVID-19 co-infected with TB, including antiviral drugs, antibacterial drugs, and a combination of drugs (Table 5). Lopinavir/Ritonavir was the most widely used antiviral drug reported in seven studies. Among the antibacterial drugs, isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide were more common antibiotics used in 36, 31, 30, and 29 studies, respectively. After these drugs, we can refer to azithromycin (28.12%). Among combination therapies, Hydroxychloroquine consumption was the most common way (27.08%). In the next rank, oxygen supplementation and anticoagulant treatment were among the most widely used methods, each with nine studies. It can be seen that many diagnostic methods were used for COVID-19 infection, but the most common methods were RT-PCR, CT scan, and CXR with 39, 22, and 17 studies, respectively. In our findings, serological tests were not common (3.12%). Regarding TB diagnostic methods, we found that acid-fast bacillus (AFB) testing, PCR, culture, and CT scan were the most common methods, with 30.20, 21.87, 17.70, and 14.58%, respectively (Table 5).

Table 4.

Summary of the case reports/case series findings.

| Overall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of study | Number of studies | Total patients with COVID-19 | Total patients with COVID-19 and TB | n/Na(%) |

| Case report | 18 | 114 | 96 | 96/114 (84.21) |

| Case series | 57 | 5843 | 101 | 101/5843 (1.72) |

| Comorbidities | Variables | Number of studies | Number of patients with co-infection | n/Na(%) |

| Hypertension | 7 | 8 | 8/96 (8.3) | |

| Diabetes | 11 | 15 | 15/96 (15.62) | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 6 | 6 | 6/96 (6.25) | |

| Anemia | 4 | 5 | 5/96 (5.2) | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | 2 | 2 | 2/96 (2.08) | |

| Bronchiectasis | 2 | 3 | 3/96 (3.12) | |

| Esophageal cancer | 2 | 2 | 2/96 (2.08) | |

| Bladder neoplasm | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Nonsmall-cell lung carcinoma | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Coronary artery perforation | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Advanced cirrhosis | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Chronic liver disease | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Exfoliative dermatitis | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Obesity | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Parkinson | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Concurrent infection | HIV | 10 | 11 | 11/96 (11.45) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Pseudomonas sp. | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Stenotrophomonas sp. | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Trichosporon sp. | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| CMV | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Aspergillus | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Clinical manifestation | Fever | 41 | 64 | 64/96 (66.66) |

| Headache | 10 | 10 | 10/96 (10.41) | |

| Diarrhea | 3 | 5 | 5/96 (5.2) | |

| Emphysema | 3 | 4 | 4/96 (4.16) | |

| Myalgia | 9 | 11 | 11/96 (11.45) | |

| Fatigue | 8 | 12 | 12.96 (12.5) | |

| Cough with sputum production | 9 | 11 | 11/96 (11.45) | |

| Cough | 36 | 54 | 54/96 (56.25) | |

| Lose appetite | 4 | 9 | 9/96 (9.37) | |

| Decreased appetite | 4 | 4 | 4/96 (4.16) | |

| Respiratory failure/distress | 10 | 14 | 14/96 (14.58) | |

| Shortness of breath | 11 | 12 | 12/96 (12.5) | |

| Reduction in breath sounds | 3 | 5 | 5/96 (5.2) | |

| Dyspnea | 14 | 16 | 16/96 (16.66) | |

| Hypoxia | 15 | 16 | 16/96 (16.66) | |

| Chest pain | 8 | 8 | ||

| Abdominal pain | 5 | 5 | 5/96 (5.2) | |

| Tachypnoea | 8 | 8 | 8/96 (8.33) | |

| Tachycardia | 6 | 6 | 6/96 (6.25) | |

| Night sweats | 5 | 5 | 5/96 (5.2) | |

| Neurologic presentation | 2 | 7 | 7/96 (7.29) | |

| Seizures | 1 | 6 | 6/96 (6.25) | |

| Rash | 2 | 3 | 3/96 (3.12) | |

| Wheeze | 1 | 3 | 3/96 (3.12) | |

| Weakness | 3 | 3 | 3/96 (3.12) | |

| Asthenia | 2 | 3 | 3/96 (3.12) | |

| Chest tightness | 2 | 3 | 3/96 (3.12) | |

| Pallor | 2 | 3 | 3/96 (3.12) | |

| Weight loss | 14 | 22 | 22/96 (22.91) | |

| Laboratory finding | Neutrophilia | 11 | 12 | 12.96 (12.5) |

| Lymphopenia | 18 | 24 | 24/96 [25] | |

| Monocytosis | 4 | 4 | 4/96 (4.16) | |

| Leucopenia | 5 | 7 | 7/96 (7.29) | |

| Leukocytosis | 12 | 18 | 18/96 (18.75) | |

| Low hemoglobin | 11 | 14 | 14/96 (14.58) | |

| Thrombocytopenia | 3 | 5 | 5/96 (5.2) | |

| High platelets | 4 | 5 | 5/96 (5.2) | |

| Low albumin | 6 | 7 | 7/96 (7.29) | |

| High fibrinogen | 5 | 7 | 7/96 (7.29) | |

| High ALT | 6 | 10 | 10/96 (10.41) | |

| High AST | 9 | 13 | 13/96 (13.54) | |

| High CRP | 31 | 44 | 44/96 (45.83) | |

| High Procalcitonin | 6 | 6 | 6/96 (6.25) | |

| High LDH | 16 | 24 | 24/96 [25] | |

| High ferritin | 13 | 14 | 14/96 (14.58) | |

| High ESR | 10 | 16 | 16/96 (16.66) | |

| High D-dimer | 16 | 21 | 21/96 (21.87) | |

| High interleukin-6 | 5 | 7 | 7/96 (7.29) | |

| High creatinine | 6 | 7 | 7/96 (7.29) | |

| Imaging | Bilateral pneumonia | 2 | 6 | 6/96 (6.25) |

| Unilateral pneumonia | 2 | 2 | 2/96 (2.08) | |

| Interstitial involvement | 4 | 4 | 4/96 (4.16) | |

| Pulmonary infiltrates | 9 | 15 | 15/96 (15.62) | |

| Tree-in-bud opacities | 3 | 7 | 7/96 (7.29) | |

| Centrilobular nodules | 1 | 2 | 2/96 (2.08) | |

| Hilar lymph nodes | 3 | 4 | 4/96 (4.16) | |

| Reticular pattern | 2 | 2 | 2/96 (2.08) | |

| Patchy opacities/consoliation | 5 | 9 | 9/96 (9.37) | |

| Patchy ground-glass opacities | 4 | 6 | 6/96 (6.25) | |

| Consolidation | 18 | 23 | 23/96 (23.95) | |

| Crazy pavement pattern | 2 | 2 | 2/96 (2.08) | |

| Ground-glass opacity | 13 | 15 | 15/96 (15.62) | |

| Mediastinal lymphadenopathy | 3 | 4 | 4/96 (4.16) | |

| Atelectasis | 4 | 4 | 4/96 (4.16) | |

| Cavitation | 8 | 16 | 16/96 (16.66) | |

| Pleural effusion | 9 | 12 | 12.96 (12.5) | |

| Type of TB | Pulmonary TB | 14 | 23 | 23/96 (23.95) |

| Tuberculous meningitis | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Abdominopelvic tuberculosis | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Disseminated tuberculosis | 2 | 2 | 2/96 (2.08) | |

| Parenchymal and endobronchial tuberculosis | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Lymphadenitis tuberculosis | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Active | 17 | 29 | 29/96 (30.20) | |

| Latent | 6 | 6 | 6/96 (6.25) | |

| Outcome | Live | 52 | 63 | 63/96 (65.62) |

| Dead | 52 | 20 | 20/96 (20.83) | |

n, number of patients with any variables; N, the total number of patients with COVID-19 and TB, nr; not report.

Table 5.

Agents used in the treatment of patients with COVID-19 and TB.

| Agent | Number of studies | Number of patients with co-infection | n/N* (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antiviral drug | Remdesivir | 2 | 2 | 2/96 (2.08) |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | 7 | 10 | 10/96 (10.41) | |

| Sovodak (sofosbuvir/daclatasvir) | 1 | 3 | 3/96 (3.12) | |

| Umifenovir | 2 | 4 | 4/96 (4.16) | |

| Oseltamivir | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Favipiravir | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Valacyclovir | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Ganciclovir | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Ribavirin | 1 | 1 | 1/96 (1.04) | |

| Antibacterial drug | Levofloxacin | 5 | 5 | 5/96 (5.2) |

| Isoniazid | 36 | 47 | 47/96 (48.95) | |

| Rifampicin | 31 | 41 | 41/96 (42.70) | |

| Ethambutol | 30 | 41 | 41/96 (42.70) | |

| Pyrazinamide | 29 | 40 | 40/96 (41.66) | |

| Azithromycin | 18 | 27 | 27/96 (28.12) | |

| Ceftriaxone | 8 | 15 | 15/96 (15.62) | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 6 | 6 | 6/96 (6.25) | |

| Ampicillin | 2 | 2 | 2/96 (2.08) | |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | 2 | 2 | 2/96 (2.08) | |

| Ceftazidime | 2 | 2 | 2/96 (2.08) | |

| Doxycycline | 2 | 2 | 2/96 (2.08) | |

| Combination therapy | Oxygen supplementation | 9 | 10 | 10/96 (10.41) |

| Respiratory support via a high flow nasal cannul | 4 | 4 | 4/96 (4.16) | |

| Methyl prednisolone | 5 | 6 | 6/96 (6.25) | |

| Corticosteroids | 3 | 5 | 5/96 (5.2) | |

| Anticoagulants | 9 | 10 | 10/96 (10.41) | |

| Zinc sulphate | 2 | 3 | 3/96 (3.12) | |

| Pyridoxine (vitamin B₆) | 3 | 4 | 4/96 (4.16) | |

| Vitamin C | 3 | 3 | 3/96 (3.12) | |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 18 | 26 | 26/96 (27.08) | |

| Dexamethasone | 5 | 5 | 5/96 (5.2) | |

| Tocilizumab | 4 | 4 | 4/96 (4.16) | |

| Chloroquine | 3 | 3 | 3/96 (3.12) | |

| Metformin | 2 | 2 | 2/96 (2.08) | |

| Convalescent plasma | 3 | 3 | 3/96 (3.12) | |

| Interferon | 2 | 2 | 2/96 (2.08) | |

| COVID-19 diagnostic method | Variables | Number of studies | Number of patients with co-infection | n/N* (%) |

| RT-PCR | 39 | 54 | 54/96 (56.25) | |

| PCR | 12 | 18 | 18/96 (18.75) | |

| Real-time fluorescence PCR | 1 | 3 | 3/96 (3.12) | |

| Serological test | 3 | 3 | 3/96 (3.12) | |

| CXR | 17 | 34 | 34/96 (35.41) | |

| CT | 22 | 31 | 31/96 (32.29) | |

| TB diagnostic method | Acid-Fast Bacillus (AFB) Testing | 14 | 29 | 29/96 (30.20) |

| Culture | 10 | 17 | 17/96 (17.70) | |

| RIF Assay | 5 | 7 | 7/96 (7.29) | |

| Genexpert | 3 | 10 | 10/96 (10.41) | |

| Xpert MTB/Rif | 5 | 5 | 5/96 (5.2) | |

| CT scan | 12 | 14 | 14/96 (14.58) | |

| HRCT | 1 | 3 | 3/96 (3.12) | |

| Chest X ray | 6 | 7 | 7/96 (7.29) | |

| Molecular testing | 1 | 4 | 4/96 (4.16) | |

| PCR | 10 | 21 | 21/96 (21.87) | |

| Interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) | 1 | 4 | 4/96 (4.16) |

4. Discussion

COVID-19 is a detrimental respiratory infection that has become a global problem due to its high transmission and lethality [18]. As a result, many studies have been conducted to learn more about the disease's mechanisms of pathogenesis, symptoms, and complications. COVID-19 is currently an essential topic of research. However, coinfections with COVID-19 are also a significant concern because they can worsen the course of the disease [19]. Some of these concurrent infections are caused by bacteria. One essential bacteria is M. tuberculosis, which causes tuberculosis [20,21]. Tuberculosis is a contagious and deadly respiratory infection that killed 1.3 million people in 2020 (among HIV-negative people) [22]. China ranks third among the eight countries that account for two-thirds of TB cases worldwide, contributing 8.4% to the globally reported cases [23]. Over a quarter (27%) of all TB cases in the world are reported from India, which continues to have the highest burden of TB [24]. The 50 U S. states and the District of Columbia (DC) provisionally reported 7860 TB cases to the National Tuberculosis Surveillance System (NTSS) in 2021. In 2021, reported TB cases increased by 9.4% (2.37) compared to 2020 (2.16) [25]. Each year, approximately 9000 cases of TB are reported in Argentina. The disease's distribution is not uniform throughout the country. The number of incident TB cases in Zambia in 2019 was estimated at 59,000 (333 per 100,000). The TB burden in Zambia remains among the highest in the world, although TB trends have been declining steadily over the years [26]. South Africa ranks among the top 20 countries with high tuberculosis burden. As of 2018, there were 737 cases of TB per 100,000 in South Africa [27,28]. Brazil ranks 16th on the list of 22 countries with the highest TB burden globally. The state of Rio de Janeiro has the highest TB incidence rate (61.2/100,000) and the highest mortality rate (5.0/100,000) [29]. Therefore, tuberculosis infection in COVID-19 patients can be expected to aggravate the complications and increase disease mortality. In 2020, the Global Tuberculosis Network (GTN) published the results of a pilot study on 49 patients co-infected with both TB and COVID-19 [30]. The authors concluded that, although the symptoms and signs are similar, TB is commonly diagnosed with or after COVID-19, and dual infection may increase the mortality rate. According to a second GTN study [31] involving 69 TB/COVID-19 patients, the overall case-fatality rate was 12.6%, higher than the 1–2% rate reported for drug-susceptible TB [10] and COVID-19 [32]. Further studies from South Africa and the Philippines revealed that COVID-19 patients with TB have a 2.7 [33] and 2.17 [34] higher mortality risk compared to COVID-19 patients without TB. Common symptoms of COVID-19 include fever, cough, and shortness of breath, similar to symptoms of patients with tuberculosis. So, it is logical that overlapping similar symptoms in COVID-19 and tuberculosis coinfection can interfere with the diagnosis and treatment. Our study showed that fever, cough, and weight loss are the most common symptoms among COVID-19 and tuberculosis coinfected patients. Another study conducted in China reported similar results [35]. COVID-19 and tuberculosis are transmitted through droplets; their target organs are the lungs. Both of them stimulate T lymphocytes, especially helper T lymphocytes, by different mechanisms, which ultimately, in severe forms of these two diseases, lead to increased production and secretion of interferons [36]. So, it is likely that they can exacerbate each other's complications. In Wang's study, it was found that patients with COVID-19 and TB coinfection were at high risk of severity than other COVID-19 patients [37]. Due to these facts, tuberculosis was the leading cause of death among infectious diseases before the onset of COVID-19, and about 10 million people, regardless of gender or age, became infected in 2020 [38]. Scattered studies have been conducted worldwide on the simultaneous presence of these two infections. Since we do not have accurate statistics about this coinfection, we evaluated the relevant prevalence and case report/series studies through systematic review and meta-analysis. Our meta-analysis showed that 1.1% of COVID-19 patients simultaneously had tuberculosis infections. Similarly, Ashutosh et al. estimated that the active pulmonary tuberculosis pool proportion was 1.07% among patients with COVID-19. Based on their study, the mortality risk was higher in patients with COVID-19 and active pulmonary tuberculosis than in others [39]. Overall, the rate of coinfection with COVID-19 and tuberculosis has been reported between 0.6% and 3.6% in the reviewed study. To justify this dispersion and difference, we can point to various reasons, including the study population, other comorbidities of patients like diabetes or hypertension, the methods of diagnosis, and the time and place of investigation regarding the prevalence of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis coinfection among patients with COVID-19 was more reported in Africa and China. Since Africa has poor health care and tuberculosis was prevalent in Africa before the advent of COVID-19 [40], it is reasonable to be likely that patients with COVID-19 and tuberculosis be more prevalent in this region. In the case of China, the high population and frequent passenger traffic may contribute to these statistics. Based on evaluated case reports/series studies, we examined other tuberculosis disorders and pulmonary involvement. The investigated studies showed that six people had extrapulmonary tuberculosis, five of whom survived. Nevertheless, due to the minimal number of such cases and lack of access to accurate information worldwide, we could not figure out the exact association of COVID-19 disease with non-pulmonary tuberculosis. One of the highlights of our study was that among concurrent infections, HIV accounted for the highest percentage. Since tuberculosis is an opportunistic infection and people with HIV have weakened immune systems than others, it is reasonable to see more tuberculosis and HIV coinfected patients [41]. According to our study, among the medications used in patients with simultaneous COVID-19 and tuberculosis, the highest consumption belonged to medicines for treating tuberculosis. There is no definitive known cure for all COVID-19 patients. Still, unlike COVID-19, tuberculosis has a specific treatment, so the higher usage of anti-tuberculosis drugs in patients with COVID-19 and TB coinfection can be justified. Our results also showed that using azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine is significant among COVID-19 and TB coinfected patients. Nevertheless, it should be noted that according to recent studies, hydroxychloroquine does not have much effect on the progression of COVID-19, and there is controversy about the effectiveness of azithromycin [42,43]. Many studies were reviewed on the early onset of tuberculosis, and at that time, various drugs were used to treat patients. Therefore, the high percentage of azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine consumption can be related to this issue. Our study had several limitations. First, we did not have enough information from many countries, so we could not fully demonstrate the prevalence of TB infection in COVID-19 patients worldwide. Second, many COVID-19 patients with TB may not have been hospitalized. Third, we only included studies published in English in our research. Fourth, some reviewed studies did not mention the type of TB. Finally, since the generality of the current study is based on the existing articles and the information provided, it was impossible to access detailed information in this case.

5. Conclusion

The simultaneous prevalence of tuberculosis among patients with COVID-19 was 1.1% in general. According to the investigations, it was found that the simultaneous infection of tuberculosis and COVID-19 has been observed in Africa, Asia, and America. Furthermore, TB infection may also increase mortality in COVID-19 patients. Based on different evaluated studies, various drug treatments were performed in COVID-19 patients with tuberculosis, and antibacterial drugs were the most used. The smart selection of the medication and faster diagnostic methods can play an essential role in the recovery of these patients. Since symptoms of TB and COVID-19 overlap, screening TB patients to rule out COVID-19 infection is highly recommended to prevent further damage in this group of patients. It would be helpful to perform further research on the relationship between COVID-19 and extrapulmonary TB coinfections.

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article. </p>

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supp. Material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare that there are no potential conflicts of interest in the present study.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Li X., Wang C., Kou S., Luo P., Zhao M., Yu K.J.C.C. Lung ventilation function characteristics of survivors from severe COVID-19: a prospective study. Crit. Care. 2020;24(1):1–2. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02992-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu M., Li M., Zhan W., Han T., Liu L., Zhang G., et al. Clinical analysis of 23 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in xinyang city of henan province. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2020;32(4):421–425. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn121430-20200301-00153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Himwaze C.M., Telendiy V., Maate F., Songwe M., Chanda C., Chanda D., et al. 2021. Post Mortem Examination of Hospital Inpatient COVID-19 Deaths in Lusaka, Zambia-A Descriptive Whole Body Autopsy Series. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goel N., Goyal N., Kumar R.J.M.A. 2021. Clinico-radiological Evaluation of Post COVID-19 at a Tertiary Pulmonary Care Centre in Delhi, India. fCD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medina N., Alastruey-Izquierdo A., Bonilla O., Ortíz B., Gamboa O., Salazar L.R., et al. 2021. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on HIV Care in Guatemala. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niang I., Diallo I., Diouf J.C.N., Ly M., Toure M.H., Diouf K.N., et al. Dakar-Senegal); 2020. Sorting and Detection of COVID-19 by Low-Dose Thoracic CT Scan in Patients Consulting the Radiology Department of Fann Hospital; p. 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guan C.S., Lv Z.B., Yan S., Du Y.N., Chen H., Wei L.G., et al. Imaging features of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): evaluation on thin-section CT. Acad. Radiol. 2020;27(5):609–613. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun Y., Dong Y., Wang L., Xie H., Li B., Chang C., et al. Characteristics and prognostic factors of disease severity in patients with COVID-19. The Beijing experience. 2020;112 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai X., Wang M., Qin C., Tan L., Ran L., Chen D., et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-2019) infection among health care workers and implications for prevention measures in a tertiary hospital in Wuhan. China. 2020;3(5):e209666–e. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.9666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li C., Su Q., Liu J., Chen L., Li Y., Tian X., et al. Comparison of clinical and serological features of RT-PCR positive and negative COVID-19 patients. J. Int. Med. Res. 2021;49(2) doi: 10.1177/0300060520972658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Zalm M.M., Lishman J., Verhagen L.M., Redfern A., Smit L., Barday M., et al. Clinical experience with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2–related illness in children: hospital experience in cape town. S. Afr. 2021;72(12):e938–e944. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sahu A.K., Dhar A., Aggarwal B.J.T.I. Imaging. Radiographic features of COVID-19 infection at presentation and significance of chest X-ray: early experience from a super-specialty hospital in India. Indian J. Radiol. Imag. 2021;31(Suppl 1):S128. doi: 10.4103/ijri.IJRI_368_20. JoR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenberg E.S., Dufort E.M., Blog D.S., Hall E.W., Hoefer D., Backenson B.P., et al. COVID-19 testing, epidemic features, hospital outcomes, and household prevalence. New York State. 2020;71(8):1953–1959. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu X., Gong W., Peng Z., Zeng F., Liu FJFim. High resolution CT imaging dynamic follow-up study of novel coronavirus pneumonia. Front. Med. 2020;7:168. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mithal A., Jevalikar G., Sharma R., Singh A., Farooqui K.J., Mahendru S., et al. High prevalence of diabetes and other comorbidities in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Delhi, India, and their association with outcomes. Diabetes Metabol. Syndr.: Clin. Res. Rev. 2021;15(1):169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mafort T.T., Rufino R., da Costa C.H., da Cal M.S., Monnerat L.B., Litrento P.F., et al. One-month outcomes of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection and their relationships with lung ultrasound signs. The Ultrasound Journal. 2021;13(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13089-021-00223-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta N., Ish P., Gupta A., Malhotra N., Caminero J.A., Singla R., et al. A profile of a retrospective cohort of 22 patients with COVID-19 and active/treated tuberculosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2020;56(5) doi: 10.1183/13993003.03408-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lagrutta L., Sotelo C.A., Estecho B.R., Beorda W.J., Francos J.L.J.M. The febrile emergency unit at muñiz hospital facing COVID-19, HIV and tuberculosis. Medicina. 2021;81(2):143–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Widiasari N.P.A., Arisanti N.L.P.E., Rai I.B.N., Iswari I.S.J.O. Two serial case of coronavirus disease-19 patients coinfected with HIV: comparison of pre-anti-retroviral (art) and on art patient. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2020;8(T1):416–421. AMJoMS. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patil S., GjijoM Gondhali. COVID-19 pneumonia with pulmonary tuberculosis: double trouble. International Journal of Mycobacteriology. 2021;10(2):206. doi: 10.4103/ijmy.ijmy_51_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agada A., Kwaghe V., Habib Z., Adebayo F., Anthony B., Yunusa T., et al. COVID-19 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis coinfection: a case report. W. Afr. J. Med. 2021;38(2):176–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adekanmi A.J., Baiyewu L.A., Osobu B.E., Omjtpamj Atalabi. vol. 37. 2020. (Where COVID-19 Testing Is Challenging: a Case Series Highlighting the Role of Thoracic Imaging in Resolving Management Dilemma Posed by Unusual Presentation). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aissaoui H., Louvel D., KdjjoCT Alsibai, Diseases O.M. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis Coinfection: A Case of Unusual Bronchoesophageal Fistula. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh A., Saini I., Meena S.K., RjijoP Gera. Demographic and clinical profile of mortality cases of COVID-19 in. Children in New Delhi. 2021;88(6):610. doi: 10.1007/s12098-021-03687-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sasson A., Aijaz A., Chernyavsky S., Salomon N., editors. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. Oxford University Press US; 2020. A coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) mystery: persistent fevers and leukocytosis in a patient with severe COVID-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bouaré F., Laghmari M., Etouche F.N., Arjdal B., Saidi I., Hajhouji F., et al. Unusual association of COVID-19, pulmonary tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus, having progressed favorably under treatment with chloroquine and rifampin. The Pan African Medical Journal. 2020;35(Suppl 2) doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.2.24952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Del Castillo R., Martinez D., Sarria G.J., Pinillos L., Garcia B., Castillo L., et al. Low-dose radiotherapy for COVID-19 pneumonia treatment: case report, procedure, and literature review. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2020;196(12):1086–1093. doi: 10.1007/s00066-020-01675-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dyachenko P.A., Smiianova O.I., Agjwl Dyachenko. MENINGO-ENCEPHALITIS in a middle-aged woman hospitalized for COVID-19. Wiad. Lek. 2021;74(5):1274–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faqihi F., Alharthy A., Noor A., Balshi A., Balhamar A., Karakitsos D.J.R. COVID-19 in a patient with active tuberculosis: a rare case-report. Respiratory Medicine Case Reports. 2020;31 doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2020.101146. MCR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Essajee F., Solomons R., Goussard P., Van Toorn R.J.B. Child with tuberculous meningitis and COVID-19 coinfection complicated by extensive cerebral sinus venous thrombosis. BMJ Case Reports CP. 2020;13(9) doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-238597. CRC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ata F., Yousaf Q., Parambil J.V., Parengal J., Mohamedali M.G., Zjtajocr Yousaf. A 28-year-old man from India with SARS-cov-2 and pulmonary tuberculosis Co-infection with central nervous system involvement. The American journal of case reports. 2020;21 doi: 10.12659/AJCR.926034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gbenga T.A., Oloyede T., Ibrahim O.R., Sanda A., Suleiman B.M.J. Pulmonary tuberculosis in coronavirus disease-19 patients: a report of two cases from Nigeria. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2020;8(T1):272–275. OAMJoMS. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Di Gennaro F., Gualano G., Timelli L., Vittozzi P., Di Bari V., Libertone R., et al. Increase in tuberculosis diagnostic delay during first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: data from an Italian infectious disease referral hospital. Antibiotics. 2021;10:272. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10030272. s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published …; 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fard N.G., Khaledi M., Afkhami H., Barzan M., Farahani H.E., Sameni F., et al. 2021. COVID-19 Coinfection in Patients with Active Tuberculosis: First Case-Report in Iran. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lian J., Jin X., Hao S., Cai H., Zhang S., Zheng L., et al. Analysis of epidemiological and clinical features in older patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outside Wuhan. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71(15):740–747. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ridgway J.P., Farley B., Benoit J.-L., Frohne C., Hazra A., Pettit N., et al. A case series of five people living with HIV hospitalized with COVID-19 in Chicago, Illinois. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2020;34(8):331–335. doi: 10.1089/apc.2020.0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Orozco J.A.M., Tinajero Á.S., Vargas E.B., Cueva A.I.D., Escobar H.R., Alcocer E.V., et al. COVID-19 and tuberculosis coinfection in a 51-year-old taxi driver in Mexico city. The American journal of case reports. 2020;21 doi: 10.12659/AJCR.927628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farias L.A.B.G., Moreira A.L.G., Corrêa E.A., de Oliveira Lima C.A.L., Lopes I.M.P., de Holanda P.E.L., et al. Case report: coronavirus disease and pulmonary tuberculosis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus: report of two cases. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020;103(4):1593. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lopinto J., Teulier M., Milon A., Voiriot G., Mjbpm Fartoukh. Severe hemoptysis in post-tuberculosis bronchiectasis precipitated by SARS-CoV-2 infection. BMC Pulm. Med. 2020;20(1):1–3. doi: 10.1186/s12890-020-01285-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Musso M., Di Gennaro F., Gualano G., Mosti S., Cerva C., Fard S.N., et al. 2021. Concurrent Cavitary Pulmonary Tuberculosis and COVID-19 Pneumonia with in Vitro Immune Cell Anergy; pp. 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luciani M., Bentivegna E., Spuntarelli V., Lamberti P.A., Guerritore L., Chiappino D., et al. Coinfection of tuberculosis pneumonia and COVID-19 in a patient vaccinated with Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG): case report. SN comprehensive clinical medicine. 2020;2(11):2419–2422. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00601-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.AlKhateeb M.H., Aziz A., Eltahir M., Elzouki A.J.C. Bilateral foot-drop secondary to axonal neuropathy in a tuberculosis patient with Co-infection of COVID-19. A Case Report. 2020;12(11) doi: 10.7759/cureus.11734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khayat M., Fan H., Vali Y.J.R. COVID-19 promoting the development of active tuberculosis in a patient with latent tuberculosis infection. A case report. 2021;32 doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2021.101344. MCR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elziny M.M., Ghazy A., Elfert K.A., Aboukamar MjtajoTM Hygiene. Case report: development of miliary pulmonary tuberculosis in a patient with peritoneal tuberculosis after COVID-19 upper respiratory tract infection. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021;104(5):1792. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baskara M.A., Makrufardi F., AjaoM Dinisari, Surgery COVID-19 and active primary tuberculosis in a low-resource setting: a case report. Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 2021;62:80–83. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2020.12.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mulale U.K., Kashamba T., Strysko J., Kyokunda L.T.J. Fatal SARS-CoV-2 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis coinfection in an infant: insights from Botswana. BMJ Case Reports CP. 2021;14(4) doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-239701. BCRC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rivas N., Espinoza M., Loban A., Luque O., Jurado J., Henry-Hurtado N., et al. Case report: COVID-19 recovery from triple infection with. Mycobacterium tuberculosis, HIV, and SARS-CoV-2. 2020;103(4):1597. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ntshalintshali S.D., Abrahams R., Sabela T., Rood J., Karamchand S., Du Plessis N., et al. Tuberculosis reactivation-a consequence of Covid-19 acquired immunodeficiency? 2021;34(1):51–53. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Çınar O.E., Sayınalp B., Karakulak E.A., Karataş A.A., Velet M., İnkaya A.Ç., et al. Convalescent (immune) plasma treatment in a myelodysplastic COVID-19 patient with disseminated tuberculosis. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2020;59(5) doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2020.102821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goussard P., Van Wyk L., Burke J., Malherbe A., Retief F., Andronikou S., et al. Bronchoscopy in children with COVID‐19. A case series. 2020;55(10):2816–2822. doi: 10.1002/ppul.25015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goussard P., Solomons R.S., Andronikou S., Mfingwana L., Verhagen L.M., Hjpp Rabie. 2020. COVID‐19 in a Child with Tuberculous Airway Compression. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pinheiro D.O., Pessoa M.S.L., Lima C.F.C., Holanda J.L.B. vol. 53. 2020. (Tuberculosis and Coronavirus Disease 2019 Coinfection). JRdSBdMT. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saraceni F., Scortechini I., Mancini G., Mariani M., Federici I., Gaetani M., et al. Severe COVID‐19 in a patient with chronic graft‐versus‐host disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplant successfully treated with ruxolitinib. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2021;23(1) doi: 10.1111/tid.13401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sarınoğlu R.C., Sili U., Eryuksel E., Yildizeli S.O., Cimsit C., AkjtjoIiDC Yagci. Tuberculosis and COVID-19: an overlapping situation during pandemic. The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries. 2020;14(7):721–725. doi: 10.3855/jidc.13152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Segrelles-Calvo G., Glauber R.D.S., Llopis-Pastor E., Frasés SJAdB. A Triple Co-infection; 2020. Trichosporon Asahii as Cause of Nosocomial Pneumonia in Patient with COVID-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shabrawishi M., AlQarni A., Ghazawi M., Melibari B., Baljoon T., Alwafi H., et al. New disease and old threats: a case series of COVID‐19 and tuberculosis coinfection in. Saudi Arab. (Quarterly Forecast Rep.) 2021;9(5) doi: 10.1002/ccr3.4233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gerstein S., Khatri A., Roth N., FjjoCT Wallach, Diseases O.M. 2021. Coronavirus Disease 2019 and Extra-pulmonary Tuberculosis Co-infection–A Case Report and Review of Literature. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dakhlia S., Iqbal P., Abubakar M., Zara S., Murtaza M., Al Bozom A., et al. 2021. A Case of Concomitant Pulmonary Embolism and Pulmonary Tuberculosis in the Era of COVID 19, a Matter of Cautious Approach. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singh A., Gupta A., Das K.J.I. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 and tuberculosis coinfection: double trouble. Indian J. Med. Specialities. 2020;11(3):164. JoMS. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pillay S., Magula N.J.S. A trio of infectious diseases and pulmonary embolism: a developing world's reality. South. Afr. J. HIV Med. 2021;22(1):1–4. doi: 10.4102/sajhivmed.v22i1.1192. AJoHM. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Srivastava S., Jaggi N.J. 2021. TB Positive Cases Go up in Ongoing COVID-19 Pandemic Despite Lower Testing of TB: an Observational Study from a Hospital from Northern India. IJoT. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vilbrun S.C., Mathurin L., Pape J.W., Fitzgerald D., Walsh K.F.J. Hygiene. Case report: multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and COVID-19 coinfection in Port-au-Prince. Haiti. 2020;103(5):1986. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0851. TAJoTM. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stjepanović M., Belić S., Buha I., Marić N., Baralić M., Mihailović-Vučinić VJSazcl. 2021. Unrecognized Tuberculosis in a Patient with COVID-19; p. 6. 00. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Subramanian N., Sagili H., Naik P., Durairaj J.J.B. Imaging as an alternate diagnostic modality in a presumptive case of abdominopelvic TB in a COVID-19 patient. BMJ Case Reports CP. 2021;14(3) doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-241882. CRC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tham S.M., Lim W.Y., Lee C.K., Loh J., Premkumar A., Yan B., et al. Four patients with COVID-19 and tuberculosis, Singapore. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26(11):2763. doi: 10.3201/eid2611.202752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cutler T., Scales D., Levine W., Schluger N., O'Donnell M.J.A., Medicine C.C. A novel viral epidemic collides with an ancient scourge: COVID-19 associated with tuberculosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020;202(5):748. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0828IM. JoR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sarma U., Mishra V., Goel J., Yadav S., Sharma S., Sherawat RkjijoCCMP-r Official Publication of Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine. Covid-19 pneumonia with delayed viral clearance in a patient with active drug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. Indian J. Crit. Care Med.: Peer-reviewed, Official Publication of Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine. 2020;24(11):1132. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Verma V., Nagar M., Jain V., Santoshi J.A., Dwivedi M., Behera P., et al. Adapting Policy Guidelines for Spine Surgeries during COVID-19 pandemic in view of evolving evidences: an early experience from a tertiary care teaching hospital. Cureus. 2020;12(7) doi: 10.7759/cureus.9147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wong S.W., Ng J.K.X., Chia Y.W.J. Tuberculous pericarditis with tamponade diagnosed concomitantly with COVID-19: a case report. European Heart Journal-Case Reports. 2021;5(1):ytaa491. doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytaa491. EHJ-CR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ortiz-Martínez Y., Mogollón-Vargas J.M., López-Rodríguez M., Rodriguez-Morales A.J.J., Disease I. A fatal case of triple coinfection: COVID-19, HIV and Tuberculosis. Trav. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021;43 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2021.102129. TM. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yadav S., Rawal G.J.T. vol. 36. 2020. (The Case of Pulmonary Tuberculosis with COVID-19 in an Indian Male-A First of its Type Case Ever Reported from South Asia). PAMJ. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yao Z., Chen J., Wang Q., Liu W., Zhang Q., Nan J., et al. Three patients with COVID-19 and pulmonary tuberculosis, Wuhan, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26(11):2754. doi: 10.3201/eid2611.201536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang Y., Zhang C., Hu Y., Yao H., Zeng X., Hu C., et al. Clinical features and outcomes of seven patients with COVID-19 in a family cluster. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020;20(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05364-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yousaf Z., Khan A.A., Chaudhary H.A., Mushtaq K., Parengal J., Aboukamar M., et al. Cavitary pulmonary tuberculosis with COVID-19 coinfection. IDCases. 2020;22 doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Воробьева О.В., Ласточкин А.В., РОМАНОВА Л.П., ЮСОВ А.А.J.P.M. Changes in organs in COVID-19 at chronic obstructive disease and pulmonary tuberculosis. A clinical case. 2021:41–44. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supp. Material/referenced in article.