Abstract

Survivorship for head and neck cancer patients presents unique challenges related to the anatomic location of their disease. After treatment, patients often have functional impairments requiring additional care and support. In addition, patients may have psychological challenges managing the effect of the disease and treatment. Routine screening is recommended for the identification of psychological conditions. This article reviews the latest research on key psychological conditions associated with head and neck cancer. It discusses risk factors for the development of each condition and provides recommendations for the management of patients who may present with psychological concerns.

Keywords: survivorship, psychology, anxiety, depression, suicide, body image disturbance

Survivorship in Head and Neck Cancer

Mucosal head and neck cancers are those that originate from the upper aerodigestive tract. Primary sites of involvement include the nasal cavity, nasopharynx, oropharynx, oral cavity, hypopharynx, and larynx. The most common cancer histology in these sites is squamous cell carcinoma, which is locally aggressive and has the potential to metastasize. Treatment is often associated with significant morbidity and disfigurement because of the specialized normal function of the primary cancer sites and surrounding region, including breathing, speaking, swallowing, taste, vision and hearing. 1

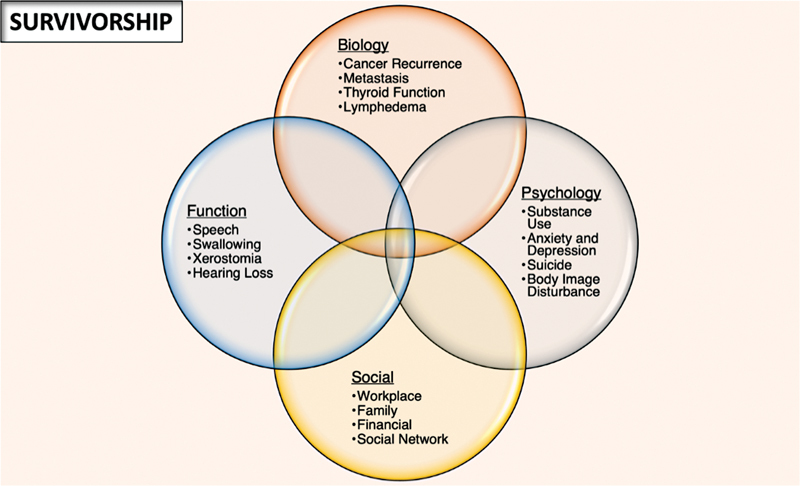

Traditionally, treatment of this disease was focused on the immediate goal of survival from disease. With an increased longevity of survival after treatment of these cancers, patients and clinicians have a vested interest in a longitudinal approach to disease management and survivorship. One result is the use of a survivorship care plan for patients from the time of diagnosis until the end of life 2 ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

A model of survivorship including a combined approach to biological, functional, psychological, and social aspects of care.

Survivorship guidelines from the American Cancer Society suggest a multifaceted approach with cancer surveillance completed in complement with functional, social, and psychological screening. Foundational to these guidelines are screening for recurrence and second primary cancers, long-term treatment effects, promoting current and future healthy behavior, and coordinating interdisciplinary care. 2 These care plans should include primary care and caregivers whenever possible. 2 Unfortunately, only 28% of patients recalled receiving a survivorship care plan with low levels of primary care involvement in their long-term care. 3

The American Head and Neck Society consensus statement on survivorship describes an evidence-based best practice for incorporating survivorship in the multidisciplinary setting. One recommendation from this consensus is to screen for common issues related to function and psychosocial issues that arise during survivorship. A patient who screens positive should be referred to the appropriate member of the multidisciplinary team. 4

In this article, we discuss the latest research on psychological conditions in the survivorship model for head and neck cancer. This article reviews the evidence and key recommendation when considering the psychological care of head and neck cancer patients ( Table 1 ).

Table 1. Recommendations for the surveillance and management of psychological aspects of head and neck cancer survivorship.

| Psychological concern | Recommendation | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Substance use | Screen alcohol dependence | • Refer to abstinence program |

| Screen for tobacco use | • Refer to smoking cessation program | |

| Screen for opioid use | • Incorporate multimodal analgesia • Refer to pain clinic |

|

| Anxiety | Screen for anxiety | • Consider starting SSRI • Refer to psychiatry |

| Depression | Screen for depression | • Consider starting SSRI • Refer to psychiatry |

| Suicide | Screen for suicidal ideation | • Urgent or emergent referral to psychiatry |

| Body image disturbance | Screen for body image disturbance | • Refer for cognitive behavioral therapy |

| Caregiver burnout | Screen for caregiver burnout | • Perform a needs assessment |

Abbreviation: SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Psychological Survivorship

Survivorship combines elements of biological, functional, social, and psychological outcomes in a longitudinal care path. Psychological outcomes are distinct, but interrelated to a patient's tumor biology, functional outcomes, and social support structure. Selected psychological conditions discussed here are substance use and abuse, anxiety and depression, suicide, body image disturbance, and caregiver burnout. Patient-reported outcome measures are discussed, and examples are provided for each psychological condition. Improving the screening and treatment of these conditions can lead to improvement in quality of life during survivorship.

Alcohol, Tobacco, and Marijuana Use

The most common two risk factors for mucosal head and neck cancers are tobacco and alcohol use, which are present in approximately 70% of patients. 5 These substances have a dose–response relationship, with increased cancer incidence for higher intensity or duration of substance use. 6 The combined use of tobacco and alcohol has a synergistic effect on cancer risk compared with the individual use of either substance. 7 The use of tobacco and alcohol has continued effects during survivorship, and use is associated with worse survival and quality of life outcome measures after treatment. 8 Data from the National Health Interview Survey indicate that problem use of alcohol and tobacco is present in 15% to 40% of head and neck cancer survivors. 9 The use of these substances has overlapping effects with psychological conditions such as depression and poor mental health. 7 9 10

Screening for alcohol and tobacco use is important to complete at each visit. There are a multitude of screening tools available. Some of the patient-reported measures used for screening of tobacco include the Russell Standard, Fagerström test, and weekly cigarette use, while screening of alcohol use includes the cut down, annoyed, guilty, and eye-opener screening test, alcohol use disorders identification test, fast alcohol screening test (CAGE, AUDIT, FAST), Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test, and weekly alcohol consumption. 11 12 13 14 15 Commonly reported metrics for tobacco and alcohol use are packs per year usage of tobacco and weekly alcohol use. A common criticism of patient-reported outcome is the additional time burden added to a busy clinical practice. Physicians may consider making these forms available to patients in the waiting area prior to their appointment to minimize extension of clinician visit time.

Practitioners are encouraged to incorporate smoking cessation and alcohol abstinence programs in their survivorship care plans. 4 Studies examining a reduction in alcohol and tobacco use have shown an association with improved survival and psychosocial outcomes. However, the optimal smoking cessation intervention is an ongoing area of research. 16 17

Marijuana has become an increasingly studied substance in the head and neck cancer population. Approximately, 12% of head and neck cancer patients have been reported to be regular marijuana users. 18 19 Unlike tobacco, marijuana does not appear to confer an increased risk for head and neck cancer. 19 Evidence on the use of cannabinoids in the general cancer population indicate that there may be no advantage in pain, sleep, or overall quality of life. It is important to advise patients on the potential adverse effect of smoking marijuana products on pulmonary function. 20 21

Opioid Misuse

Opioids are commonly prescribed to treat pain associated with head and neck cancer and during the subsequent course of treatment. Long-term use of opioid is higher among the head and neck cancer population compared with the general cancer population, presenting a challenge regarding opioid dependency in this population. The percentage of patients who continue to require daily opioids ranges widely from 15% to 55% at 6 months posttreatment. 22 23

Screening tests for opioid misuse include the Current Opioid Misuse Measure, Opioid Risk Tool, Patient Medication Questionnaire, and the Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain-Revised (SOAPP-R) ( Table 2 ). 24 25 26 27 These may be useful in screening patients after 6 months when the acute posttreatment pain and inflammation have resolved. 22 28 Furthermore, encouraging patients to complete a pain diary can be useful in identifying not only the degree of pain experienced by the patient, but also even alternative approaches utilized by patients to help alleviate their pain. 29

Table 2. Selected patient-reported outcome measures for head and neck cancer screening and surveillance.

| Psychological concern | Patient-reported outcome measures |

|---|---|

| Alcohol dependence |

• CAGE

15

• AUDIT 76 • FAST 14 • Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test 11 |

| Tobacco use |

• Russell Standard

13

• Fagerström test 12 • Weekly cigarette use |

| Opioid use |

• Current Opioid Misuse Measure

26

• Opioid Risk Tool 25 • Patient Medication Questionnaire 25 • Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain-Revised (SOAPP-R). 24 |

| Anxiety |

• GAD-7

77

• Zung self-rating anxiety scale (SAS) 42 • Beck anxiety inventory 78 • Duke anxiety depression scale 79 |

| Depression |

• Patient Health Questionnaire-9

43

• Zung self-rated depression scale 41 • Beck Depression inventory 80 • Duke anxiety depression scale 79 |

| Suicidal ideation |

• Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation

81

• Distress Thermometer 44 • Suicide Ideation and Behavior Assessment Tool 82 |

| Body image disturbance |

• Body Image Scale

68

• Derriford Appearance Scale 83 • Body Image Questionnaire 84 • Body Satisfaction Scale 85 |

| Caregiver burnout |

• Caregiver Strain Index

72

• Perceived Stress Scale 73 • The Caregiver Quality of Life Index |

Abbreviations: CAGE, cut down, annoyed, guilty, and eye-opener; AUDIT, alcohol use disorders identification test; FAST, fast alcohol screening test; GAD-7, general anxiety disorder-7.

To reduce the development of opioid misuse, multimodal analgesia has been recommended for postoperative pain. 30 By targeting different receptors responsible for the sensation of pain through use of more than one class of analgesic medications, the use of multimodal analgesia has shown a reduction in postoperative opioid usage and improved pain management in the head and neck cancer population. 31 32 33 34 By prescribing opioids in conjunction with nonopioid systemic analgesics (e.g. acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, gabapentinoids, ketamine) and/or local anesthetics, physicians can effectively tailor multimodal analgesia management to the specific pain quality uniquely experienced by each patient. 34 Thus, physicians are recommended to incorporate multimodal analgesia in the management of pain for head and neck cancer patients.

Anxiety and Depression

Anxiety and depression are two common psychological disorders during head and neck cancer survivorship. 35 At least one-fifth of head and neck cancer survivors report anxiety or depression. Risk factors for anxiety include patients of younger age, Medicare status, and female sex. 36 Depression is associated with poor oral function and increased substance use. 37 38 Both anxiety and depression are associated with worse patient-reported quality of life outcomes. 39 Only half of patients who have reported symptoms of anxiety or depression will seek or undergo counseling. 38

Survivors should be screened for depression and anxiety symptoms at regular intervals using a validated questionnaire. 4 There are a plethora of patient-reported outcome measures for anxiety and depression. A systematic review of questionnaires identified the Zung self-rating anxiety scale, the Zung self-rated depression scale, and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 as most suitable for head and neck cancer population based on their psychometric properties. 40 41 42 43 However, there are several other patient-reported outcomes such as the Distress Thermometer, which are widely reported in the literature. 40 44

Patients who show signs concerning for a mental health disorder should be referred to support services such as psychotherapy and psychology. 4 In patients for whom transportation could interfere with follow-up with support services, telemedicine offers another effective modality at reducing the severity of depressive symptoms. 45 Furthermore, although support groups have shown to reduce head and neck cancer patient distress, unfortunately this has not been consistently offered to patients. 46 47 The importance of these interventions is at least as important as optimizing patients' function in the posttreatment phase of survivorship. 35 Psychologic intervention of cognitive behavior therapy has shown to be an efficacious intervention in the cancer population. 48 49 50

A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial in the head and neck cancer population suggests good efficacy with the prophylactic pharmacologic use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). This effect is strongest in the subpopulation of patients who receive radiation with or without chemotherapy. The prophylactic use of SSRI resulted in a 50% reduction in depression. 49 These drugs are widely prescribed for use in the cancer population and carry a relatively low complication profile. 51 Physicians should consider the use of an SSRI medication in head and neck cancer patients with signs or symptoms of depression.

Suicide

An underreported problem in the head and neck cancer survivorship is the risk of suicide. 52 Head and neck cancer survivors have one of the highest rates of suicide among the general cancer population. 53 Nearly 1% of head and neck cancer survivors attempt suicide and 0.4% will have a suicide event. 54 Suicide events have a standardized mortality ratio of 3.6 compared with the general population and are highest in the first 5 years after diagnosis. 55 Risk factors for suicide completion include male gender, white race, advanced stage, and unmarried marital status. 53

Suicidal ideation may be screened for in the clinic to help identify at-risk individuals and prevent a suicide event. 56 The Distress Thermometer and Beck Suicide Inventory have been used in head and neck cancer population to screen for suicidal ideation. 54 56 These patient-reported outcome scales should be utilized as initial screening tools to identify at-risk individuals requiring further psychiatric assessment.

Suicidal ideation has been prospectively studied in the head and neck cancer population to be around 8% to 10%. This risk is highest within the initial 3 months after treatment. 54 Physicians should screen for suicidal ideation in individuals with dysphoria or depression or if there is any clinical suspicion of suicidal ideation. Suicidal ideation should be managed with an urgent or emergent referral to psychiatry for additional care and support.

Body Image Disturbance

Body image disturbance is defined by perceived disfigurement and dysfunction associated with a patients survivorship. 57 Key elements of body image disturbance include dissatisfaction with appearance, efforts for appearance concealment, distress revolving around functional impairments, and social isolation and avoidance. 58 Body image disturbance has a prevalence as high as 75% in patients with head and neck cancer. 59 The development of body image disturbance can lead to significant psychosocial morbidity including feelings of social isolation, depression, anxiety, stigmatization, and overall decreased quality of life. 57

Demographic factors related to increased risk for body image disturbance include female sex, younger age, lower educational attainment, unemployment, single relationship status, and living in urban areas. In terms of oncological and procedural risk factors, laryngeal/hypopharyngeal cancer, worsening tumor grade and stage, free flap reconstruction, and use of multiple treatment modalities have been associated with body image disturbance. 60 61 62 63 64 Of the emotional and psychosocial risk factors, preoperative coping skills, prolonged denial surrounding cancer diagnosis, and a history of depression or suicidal ideation place patients at higher risk for future body image disturbance, with depression being the greatest risk factor. 65 66 67 Difficulties with communication and eating as well as baseline physical symptom burden represent some of the functional risk factors associated with future body image disturbance development. 66

The most widely used screening tool for body image disturbance is the Body Image Scale. 58 The 10-item screening tool results in scores ranging from 0 to 30, with a cutoff score of 8 or greater considered to be clinically significant. 68 Following surgical treatment, body image disturbance increases at 3 months posttreatment and may stabilize around 6 to 12 months posttreatment. 66

Despite the multitude of risk factors for development of body image disturbance and studies indicating a persistence of body image disturbance following treatment, research into possible interventions have been limited. One study utilized a novel telemedicine-based cognitive behavioral therapy intervention termed BRIGHT (Building a Renewed ImaGe after Head & neck cancer Treatment), which was shown to decrease postoperative body image disturbance within a limited number of head and neck cancer patients. 69 Unfortunately, other body image disturbance interventions that have found success in patients with other forms of cancer have not shown the same degree of improvement in body image disturbance among patients with head and neck cancer. 70

Despite the lack of evidence-based interventions, better preoperative expectations, improved social support, and positive rational acceptance have been identified as key factors that influence the severity of body image disturbance. 58 Setting clear preoperative expectations, providing early involvement with the multidisciplinary team, and validating each patient's experience may help reduce the severity of body image disturbance. Furthermore, cognitive behavioral therapy may decrease postoperative body image disturbance within a limited number of head and neck cancer survivors. 69 Physicians should screen for body image disturbance and appropriately refer patients for cognitive behavioral therapy.

Caregiver Burnout

When we consider psychological survivorship, we often focus solely on the patient. Given the specific burden of care and recovery associated with head and neck cancer and its treatment, it is important to also consider the psychological impact on the caregiver and/or patient support system. Caregivers are often responsible for demanding tasks including help with finances, communication, transportation, and tasks of daily living. Head and neck cancer survivors can also have significant standing care needs including wound care, tracheotomy management, and care of a gastrostomy tube. In addition, reviews on the topic highlight the disproportionate number of female caregivers compared with males. 71

The use of screening tools may be helpful adjuncts to assess caregiver burnout. The Caregiver Strain Index and Caregiver Quality of Life Index are two tools previously used to assess caregiver burden in the head and neck cancer population. 72 73

Caregivers are a crucial component of a patient's survivorship care plan. In caregivers with burnout, a needs assessment can be performed to identify the need for additional supports. 74 In addition, generating a tailored support plan using a standardized tool such as the survivorship needs assessment planning may assist in the care of survivors and their primary caregivers. 75

Conclusion

The modern treatment of patient with head and neck cancer includes a holistic approach to care. At each clinic visit, time should be allocated for the screening and management of associated psychological aspects of the condition. Special attention should be paid to patients within the first 6 months of treatment, as many of the psychological concerns peak during this timeframe. Screening for psychological disorders should be completed with validated and reliable instruments. Patients who screen positive for a psychological condition should be reviewed by a health care professional and have an action plan incorporated in their visit.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Hong W K, Weber R S.Head and Neck Cancer: Basic and Clinical AspectsSpringer;2012

- 2.Cohen E E, LaMonte S J, Erb N L. American Cancer Society Head and Neck Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(03):203–239. doi: 10.3322/caac.21343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pagedar N A, Kendell N, Christensen A J, Thomsen T A, Gist M, Seaman A T. Head and neck cancer survivorship from the patient perspective. Head Neck. 2020;42(09):2431–2439. doi: 10.1002/hed.26265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goyal N, Day A, Epstein J. Head and neck cancer survivorship consensus statement from the American Head and Neck Society. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2021;7(01):70–92. doi: 10.1002/lio2.702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beynon R A, Lang S, Schimansky S. Tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking at diagnosis of head and neck cancer and all-cause mortality: results from head and neck 5000, a prospective observational cohort of people with head and neck cancer. Int J Cancer. 2018;143(05):1114–1127. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Credico G, Polesel J, Dal Maso L. Alcohol drinking and head and neck cancer risk: the joint effect of intensity and duration. Br J Cancer. 2020;123(09):1456–1463. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-01031-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCarter K, Baker A L, Britton B. Smoking, drinking, and depression: comorbidity in head and neck cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Cancer Med. 2018;7(06):2382–2390. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howren M B, Christensen A J, Pagedar N A. Problem alcohol and tobacco use in head and neck cancer patients at diagnosis: associations with health-related quality of life. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(10):8111–8118. doi: 10.1007/s00520-022-07248-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balachandra S, Eary R L, Lee R. Substance use and mental health burden in head and neck and other cancer survivors: a National Health Interview Survey analysis. Cancer. 2022;128(01):112–121. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee J H, Ba D, Liu G, Leslie D, Zacharia B E, Goyal N. Association of head and neck cancer with mental health disorders in a large insurance claims database. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(04):339–344. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.4512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selzer M L, Vinokur A, van Rooijen L. A self-administered short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST) J Stud Alcohol. 1975;36(01):117–126. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1975.36.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heatherton T F, Kozlowski L T, Frecker R C, Fagerström K O. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(09):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.West R, Hajek P, Stead L, Stapleton J. Outcome criteria in smoking cessation trials: proposal for a common standard. Addiction. 2005;100(03):299–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hodgson R, Alwyn T, John B, Thom B, Smith A. The FAST alcohol screening test. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37(01):61–66. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schofield A. The CAGE questionnaire and psychological health. Br J Addict. 1988;83(07):761–764. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb00508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCarter K, Martínez Ú, Britton B. Smoking cessation care among patients with head and neck cancer: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2016;6(09):e012296. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang M W, Oakley R, Dale C, Purushotham A, Møller H, Gallagher J E. A surgeon led smoking cessation intervention in a head and neck cancer centre. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(01):636. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0636-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J, Hua G, Zhang H. Rate of second primary head and neck cancer with cannabis use. Cureus. 2020;12(11):e11483. doi: 10.7759/cureus.11483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berthiller J, Lee Y CA, Boffetta P. Marijuana smoking and the risk of head and neck cancer: pooled analysis in the INHANCE consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(05):1544–1551. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams A M, Gilbert M, Siddiqui F. Cannabis use in patients with head and neck cancer and radiotherapy outcomes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2022;112(05):e60–e61. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mücke M, Weier M, Carter C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of cannabinoids in palliative medicine. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2018;9(02):220–234. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zayed S, Lin C, Boldt R G. Risk of chronic opioid use after radiation for head and neck cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020;6(02):100583. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2020.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hinther A, Rasool A, Nakoneshny S C. Chronic opioid use following surgery for head and neck cancer patients undergoing free flap reconstruction. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;50(01):28. doi: 10.1186/s40463-021-00508-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Butler S F, Fernandez K, Benoit C, Budman S H, Jamison R N. Validation of the revised Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPP-R) J Pain. 2008;9(04):360–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Webster L R, Webster R M. Predicting aberrant behaviors in opioid-treated patients: preliminary validation of the Opioid Risk Tool. Pain Med. 2005;6(06):432–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butler S F, Budman S H, Fernandez K C.Development and validation of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure Pain 2007130(1-2):144–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ducharme J, Moore S. Opioid use disorder assessment tools and drug screening. Mo Med. 2019;116(04):318–324. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carmichael A N, Morgan L, del Fabbro E. Identifying and assessing the risk of opioid abuse in patients with cancer: an integrative review. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2016;7:71–79. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S85409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arneson D L, Coss D C, Rovick L P, Guthrie P F. An interprofessional pain diary in transitional care: a feasibility project. J Dr Nurs Pract. 2020;13(03):195–201. doi: 10.1891/JDNP-D-19-00075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chou R, Gordon D B, de Leon-Casasola O A. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists' Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17(02):131–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Go B C, Go C C, Chorath K, Moreira A, Rajasekaran K. Multimodal analgesia in head and neck free flap reconstruction: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;166(05):820–831. doi: 10.1177/01945998211032910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hinther A, Nakoneshny S C, Chandarana S P. Efficacy of multimodal analgesia for postoperative pain management in head and neck cancer patients. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(06):1266. doi: 10.3390/cancers13061266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldberg S F, Pozek J J, Schwenk E S, Baratta J L, Beausang D H, Wong A K. Practical management of a regional anesthesia-driven acute pain service. Adv Anesth. 2017;35(01):191–211. doi: 10.1016/j.aan.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwenk E S, Mariano E R. Designing the ideal perioperative pain management plan starts with multimodal analgesia. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2018;71(05):345–352. doi: 10.4097/kja.d.18.00217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hammermüller C, Hinz A, Dietz A. Depression, anxiety, fatigue, and quality of life in a large sample of patients suffering from head and neck cancer in comparison with the general population. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(01):94. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07773-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Götze H, Friedrich M, Taubenheim S, Dietz A, Lordick F, Mehnert A. Depression and anxiety in long-term survivors 5 and 10 years after cancer diagnosis. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(01):211–220. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04805-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu Y S, Lin P Y, Chien C Y. Anxiety and depression in patients with head and neck cancer: 6-month follow-up study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:1029–1036. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S103203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen A M, Daly M E, Vazquez E. Depression among long-term survivors of head and neck cancer treated with radiation therapy. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139(09):885–889. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.4072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lenze N R, Bensen J T, Yarbrough W G, Shuman A G. Characteristics and outcomes associated with anxiety and depression in a head and neck cancer survivorship cohort. Am J Otolaryngol. 2022;43(03):103442. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2022.103442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shunmugasundaram C, Rutherford C, Butow P N, Sundaresan P, Dhillon H M. What are the optimal measures to identify anxiety and depression in people diagnosed with head and neck cancer (HNC): a systematic review. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2020;4(01):26. doi: 10.1186/s41687-020-00189-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.William W K. Dordrecht: Springer; 2014. Zung self-rating depression scale; p. 7317. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zung W WK. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12(06):371–379. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(71)71479-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kroenke K, Spitzer R L, Williams J BW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(09):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN Guidelines Version 1.2022 Distress Management. GuidelinesPublished online 2022. Accessed August 17, 2022 at:https://www.nccn.org/docs/default-source/patient-resources/nccn_distress_thermometer.pdf?sfvrsn=ef1df1a2_4

- 45.Kroenke K, Theobald D, Wu J. Effect of telecare management on pain and depression in patients with cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304(02):163–171. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jabbour J, Milross C, Sundaresan P. Education and support needs in patients with head and neck cancer: a multi-institutional survey. Cancer. 2017;123(11):1949–1957. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ringash J, Bernstein L J, Devins G. Head and neck cancer survivorship: learning the needs, meeting the needs. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2018;28(01):64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Richardson A E, Broadbent E, Morton R P. A systematic review of psychological interventions for patients with head and neck cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(06):2007–2021. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04768-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lydiatt W M, Bessette D, Schmid K K, Sayles H, Burke W J. Prevention of depression with escitalopram in patients undergoing treatment for head and neck cancer: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139(07):678–686. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.3371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barsevick A M, Sweeney C, Haney E, Chung E.A systematic qualitative analysis of psychoeducational interventions for depression in patients with cancer Oncol Nurs Forum 2002290173–84., quiz 85–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ostuzzi G, Matcham F, Dauchy S, Barbui C, Hotopf M. Antidepressants for the treatment of depression in people with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;4(04):CD011006. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011006.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Massa S T, Hong S A, Osazuwa-Peters N. Lethal suicidal acts among head and neck cancer survivors: the tip of a distress iceberg. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;147(11):989–990. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2021.2840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kendal W S. Suicide and cancer: a gender-comparative study. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(02):381–387. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Henry M, Rosberger Z, Bertrand L. Prevalence and risk factors of suicidal ideation among patients with head and neck cancer: longitudinal study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;159(05):843–852. doi: 10.1177/0194599818776873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Misono S, Weiss N S, Fann J R, Redman M, Yueh B. Incidence of suicide in persons with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(29):4731–4738. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.8941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chang D C, Chen A WG, Lo Y S, Chuang Y C, Chen M K. Factors associated with suicidal ideation risk in head and neck cancer: a longitudinal study. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(11):2491–2495. doi: 10.1002/lary.27843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rhoten B A, Murphy B, Ridner S H. Body image in patients with head and neck cancer: a review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2013;49(08):753–760. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ellis M A, Sterba K R, Day T A. Body image disturbance in surgically treated head and neck cancer patients: a patient-centered approach. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;161(02):278–287. doi: 10.1177/0194599819837621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fingeret M C, Yuan Y, Urbauer D, Weston J, Nipomnick S, Weber R. The nature and extent of body image concerns among surgically treated patients with head and neck cancer. Psychooncology. 2012;21(08):836–844. doi: 10.1002/pon.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ellis M A, Sterba K R, Brennan E A. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures assessing body image disturbance in patients with head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;160(06):941–954. doi: 10.1177/0194599819829018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beal B T, White E K, Behera A K. Patients' body image improves after Mohs micrographic surgery for nonmelanoma head and neck skin cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44(11):1380–1388. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Clarke S A, Newell R, Thompson A, Harcourt D, Lindenmeyer A. Appearance concerns and psychosocial adjustment following head and neck cancer: a cross-sectional study and nine-month follow-up. Psychol Health Med. 2014;19(05):505–518. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2013.855319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Macias D, Hand B N, Maurer S. Factors associated with risk of body image-related distress in patients with head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;147(12):1019–1026. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2021.1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen S C, Yu P J, Hong M Y. Communication dysfunction, body image, and symptom severity in postoperative head and neck cancer patients: factors associated with the amount of speaking after treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(08):2375–2382. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2587-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fingeret M C, Vidrine D J, Reece G P, Gillenwater A M, Gritz E R. Multidimensional analysis of body image concerns among newly diagnosed patients with oral cavity cancer. Head Neck. 2010;32(03):301–309. doi: 10.1002/hed.21181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Henry M, Albert J G, Frenkiel S. Body image concerns in patients with head and neck cancer: a longitudinal study. Front Psychol. 2022;13:816587. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.816587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dropkin M J. Body image and quality of life after head and neck cancer surgery. Cancer Pract. 1999;7(06):309–313. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.76006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hopwood P, Fletcher I, Lee A, Al Ghazal S. A body image scale for use with cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(02):189–197. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Graboyes E M, Maurer S, Park Y. Evaluation of a novel telemedicine-based intervention to manage body image disturbance in head and neck cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2020;29(12):1988–1994. doi: 10.1002/pon.5399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Melissant H C, Jansen F, Eerenstein S EJ. A structured expressive writing activity targeting body image-related distress among head and neck cancer survivors: who do we reach and what are the effects? Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(10):5763–5776. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06114-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Benyo S, Phan C, Goyal N.Health and well-being needs among head and neck cancer caregivers - a systematic review Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2022(e-pub ahead of print) 10.1177/00034894221088180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Robinson B C. Validation of a caregiver strain index. J Gerontol. 1983;38(03):344–348. doi: 10.1093/geronj/38.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(04):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Richardson A, Plant H, Moore S, Medina J, Cornwall A, Ream E. Developing supportive care for family members of people with lung cancer: a feasibility study. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(11):1259–1269. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0233-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sterba K R, Armeson K, Zapka J. Evaluation of a survivorship needs assessment planning tool for head and neck cancer survivor-caregiver dyads. J Cancer Surviv. 2019;13(01):117–129. doi: 10.1007/s11764-019-0732-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Saunders J B, Aasland O G, Babor T F, de la Fuente J R, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption–II. Addiction. 1993;88(06):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Spitzer R L, Kroenke K, Williams J BW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Beck A T, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer R A. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(06):893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Parkerson G R, Jr, Broadhead W E, Tse C K. The Duke Health Profile. A 17-item measure of health and dysfunction. Med Care. 1990;28(11):1056–1072. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199011000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Beck A T, Ward C H, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Beck A T, Steer R A, Ranieri W F. Scale for Suicide Ideation: psychometric properties of a self-report version. J Clin Psychol. 1988;44(04):499–505. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198807)44:4<499::aid-jclp2270440404>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Alphs L, Fu D J, Williamson D. Suicide Ideation and Behavior Assessment Tool (SIBAT): evaluation of intra- and inter-rater reliability, validity, and mapping to Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment. Psychiatry Res. 2020;294:113495. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Klassen A, Newton J, Goodacre T. The Derriford appearance scale (DAS-59) Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54(07):647–648. doi: 10.1054/bjps.2001.3660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bruchon-Schweitzer M. Dimensionality of the body-image: the body-image questionnaire. Percept Mot Skills. 1987;65(03):887–892. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dewey M E, Newton T, Brodie D, Kiemle G. Development and preliminary validation of the body satisfaction scale (BSS) Psychol Health. 1990;4(03):213–220. [Google Scholar]