Abstract

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) are classified as non-enveloped ssDNA viruses. However, AAV capsids embedded within exosomes have been observed, and it has been suggested that the AAV membrane associated accessory protein (MAAP) may play a role in envelope-associated AAV (EA-AAV) capsid formation. Here, we observed and selected sufficient homogeneous EA-AAV capsids of AAV2, produced using the Sf9 baculoviral expression system, to determine the cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure at 3.14 Å resolution. The reconstructed map confirmed that the EA-AAV capsid, showed no significant structural variation compared to the non-envelope capsid. In addition, the Sf9 expression system used implies the notion that MAAP may enhance exosome AAV encapsulation. Furthermore, we speculate that these EA-AAV capsids may have therapeutic benefits over the currently used non-envelope AAV capsids, with advantages in immune evasion and/or improved infectivity.

Keywords: Exo-AAV, Enveloped-AAV, EA-AAV capsid, Sf9 production, Structure, MAAP, Gene therapy

1. Introduction

Adeno-associated viruses (AAV) are non-enveloped viruses, that belong to the family Parvoviridae, genus Dependoparvovirus, that package a single stranded DNA (ssDNA) genome within a ~26 nm T = 1 icosahedral capsid (Xie et al., 2002). The virus capsid is composed of the viral proteins (VPs) (VP1 83 kDa, VP2 72 kDa, and VP3 63 kDa) in a ~1:1:10 ratio (Buller and Rose, 1978). VP1 and VP2 are N-terminal extended forms of VP3, with the VP1 unique region (VP1u) encoding a phospholipase A2 (PLA2) domain which are required for infectivity (Girod et al., 2002). The capsid structures of the AAV serotypes, AAV1-13 have been determined by either X-ray crystallography and/or cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) (Large et al., 2021). The AAV capsids are assembled from sixty VPs through 2-, 3-, and 5-fold VP interactions. The capsid core consists of an anti-parallel, eight-stranded (βB to βI) β-barrel motif with an additional strand, βA, anti-parallel to βB and an α-helix (αA). Between the β-strands, large insertion loops form the exterior surface of the capsid. These are characterized by high amino acid sequence and structure variability. Nine such regions at the apex of these insertion loops have been defined and assigned variable regions (VRs) by structural alignments (Govindasamy et al., 2006; Mietzsch et al., 2019). Despite these variabilities the overall AAV capsid morphology is conserved between the serotypes. All the AAV capsids possess cylindrical channels at the icosahedral 5-fold axes that are believed to be the route of genomic DNA packaging and VP1u externalization following cell entry (Bleker et al., 2005). At the 2-fold axes, depressions are flanked by protrusions surrounding the 3-fold axes and raised regions between the 2- and 5-fold axes that are termed 2/5-fold walls. The 2/5-fold wall and 3-fold protrusions have been identified as receptor binding sites for many AAV serotypes and play important roles in cell transduction (Large et al., 2021). Additionally, these regions, including the 5-fold region, displays antigenic sites for antibodies raised by the host immune response (Emmanuel et al., 2021).

To date, AAVs are one of the most commonly used vectors for a variety of gene therapy applications. As such, two AAV biologics have been approved by the FDA (Fischer, 2017; Caccomo, 2019). However, a major challenge for AAV-mediated gene therapy is the presence of pre-existing neutralizing antibodies against the AAV capsids in a large percentage of the population (Boutin et al., 2012; Greenberg et al., 2015). These antibodies can severely reduce the desired therapeutic effect or exclude patients from receiving an AAV-based gene therapy vector (Boutin et al., 2012; Greenberg et al., 2015). Strategies to reduce the antigenicity of the AAV capsids include the engineering of the capsid surface amino acids (Jose et al., 2018; Havlik et al., 2020) or the conjugation of molecules, e.g. polyethylene glycol (Yao et al., 2017; Mével et al., 2020) to the surface of the capsid.

While AAVs are generally described as non-enveloped viruses, exosome-associated (enveloped) AAV (exo-AAV) particles have been observed. Previous studies have shown that these exo-AAV are infectious and are currently being investigated in pre-clinical studies for gene therapy applications (György et al., 2014, 2017; Meliani et al., 2017). As the capsids mediate the attachment to cell receptor(s), the mechanism of cell entry, trafficking, and uncoating for exo-AAVs remain unclear. On the other hand, the surrounding membrane shields the AAV capsids from neutralizing antibodies (Meliani et al., 2017; György et al., 2014).

Unlike for cell entry, the egress of the AAVs has been poorly characterized. AAV vectors are generally released by lysis of their producer cells. However recently, the newly identified membrane associated accessory protein (MAAP) has been implicated in viral non-lytic egress/exosome encapsulation (Ogden et al., 2019; Elmore et al., 2021; Cheng et al., 2021). MAAP has also been shown to accumulate at the host cell membrane and contribute to infectivity (Ogden et al., 2019; Cheng et al., 2021), and MAAP alone can generated exosomes that can be purified by iodixanol gradient and accumulate in the 30% fractions (demonstrated by Elmore et al. pre-print (Elmore et al., 2021)). In addition, it has been demonstrated that exo-AAVs are enriched in MAAP (Cheng et al., 2021), and that the presence of MAAP is sufficient to pull down non-enveloped AAV capsids in vitro (Elmore et al., 2021). Taken together, these findings suggest that MAAP plays a role in associating AAV capsids into cellular exosomes.

This study structurally characterizes homogeneous envelope-associated AAV2 (EA-AAV) capsids, obtained from the Sf9 baculoviral expression system and reports the cryo-EM structure at 3.14 Å resolution. Compared to the non-enveloped capsids (~26 nm in diameter), the size of the EA-AAV capsids was ~40 nm in diameter. The 3-fold protrusions were observed to be located in close proximity to the membrane envelope. However, the structure of the EA-AAV capsid does not display observable structural differences from its non-enveloped counterpart.

2. Results & discussion

2.1. Production of VLPs in Sf9 cells generated enveloped particles

To isolate AAV2 capsids embedded in exosomes, virus like particles (VLPs) were purified by iodixanol gradient ultracentrifugation. SDS-PAGE gels of the purified VLPs showed VP1, VP2, and VP3 at their expected (1:1:10) ratio with minor (<5%) impurities of proteins of >250 and <50 kDa molecular weights (Supplemental Fig. S1).

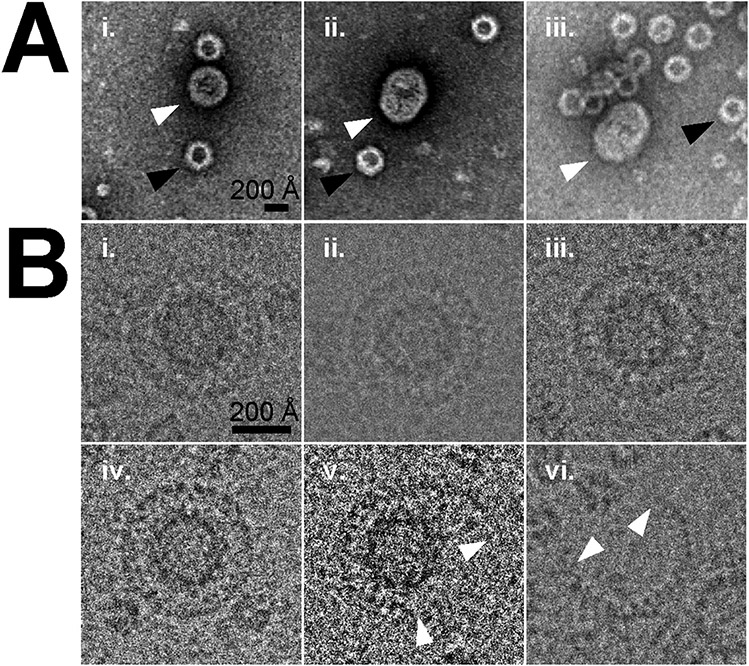

When screening the VLP samples, using negative stain EM, the vast majority of capsids observed were non-enveloped. However, a minor species of ~40 nm diameter spheroids were observed which were stain impermeable in the preparation (Fig. 1A). Given that exosome size typically ranges from 40 to 100 nm in diameter, these particles were within the expected size range of exosomes (Raposo and Stoorvogel, 2013). A small number of 10–15 nm particles were also noted in the background likely representing impurities of presumably cellular proteins. Having confirmed VLP and the presence of a stain impermeable species expected to be exosomes, a high resolution cryo-EM data collection was conducted.

Fig. 1. Enveloped particle identification.

A) Negative stain electron microscopy of particles (i-iii) reveals presence of both enveloped (white arrows) and non-enveloped (black arrows) capsids. Panels i-iii are ordered in by sphericity of the enveloped capsids. It should be noted as the envelopes are stain-impermeable their interior contents are obscured. Scale bar depicts 200 Å. B) Cryo-electron microscopy of capsids (i-iv) show the presence of enveloped capsids. These are examples of the spheroids selected for single particle reconstruction. In addition, broken (v), and capsid void (empty) (vi) envelopes were also observed. White arrows (v & vi) indicate the ends of broken envelopes. Scale bar depicts 200 Å.

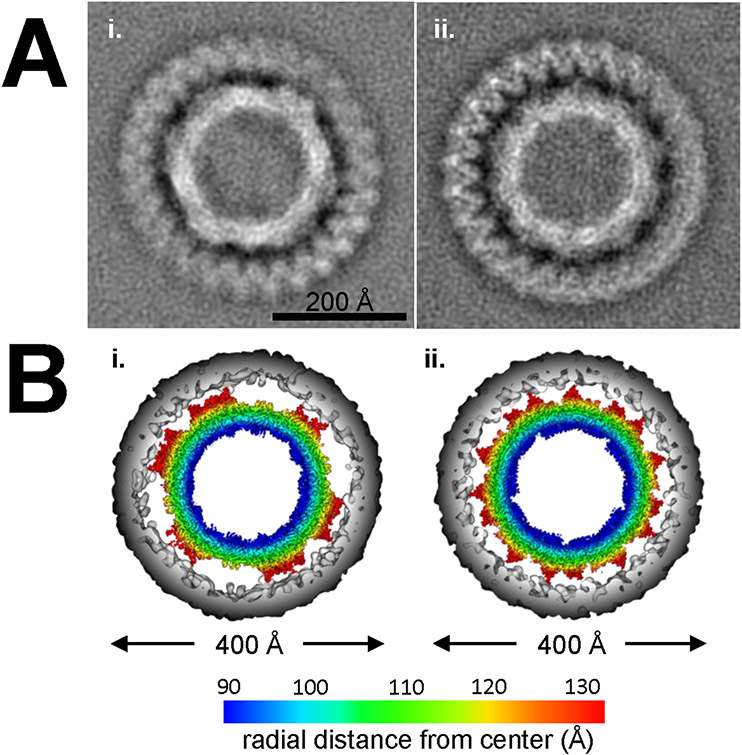

Similar to the negative stain samples, in the cryo-EM micrographs the expected non-enveloped AAV VLP capsids of 26 nm diameter were the prominent species (number boxed 46,289), but sparsely mixed within the sample were envelope-associated AAV (EA-AAV) capsid particles (number boxed 506) of ~40 nm in diameter. Based on the numbers of observations, it was calculated that approximately 1 in every ~90 particles selected was an EA-AAV capsid. A selection of near spherical EA-AAV capsids (291 particles) were further identified and used in the image reconstruction shown in Fig. 1B. A number of broken EA-AAV capsid particles (not included in the cryo-EM reconstruction) were also observed (Fig. 1B) that may have resulted from lysing of the envelope during the vitrification process. The observation of a homogenous population of EA-AAV capsids in cryo-EM (Fig. 1B), was in contrast to previous observations (György et al., 2017), where the reported heterogenous population contained multiple icosahedrons per exosome (exo-AAV) with one or more envelope species. The difference, in this sample preparation and those previously reported, could be due to alternative purification techniques and the specific density of the EA-AAV capsids in the iodixanol fractions collected. In contrast, previous electron microscopy studies were done with EA-AAVs purified by differential centrifugation instead of iodixanol (György et al., 2017). From the calculated two-dimensional (2D) class averaged images (Fig. 2A), the thickness of the envelope was estimated to be ~5 nm, which is typical for a lipid bilayer (Nagle and Tristram-Nagle, 2000).

Fig. 2. Two-dimensional class classification and orientation of EA-AAV capsids.

A) Two-dimensional (2D) classification of 291 particles used for reconstruction generated two classes, i) 2-fold and ii) 5-fold views perpendicular to the plane of view. Scale bar depicts 200 Å. B) The final image reconstructed map with envelope (gray) and capsid (colored radially as depicted in key). Capsid models have been rotated and orthogonally sliced as in the views of the panels in A to demonstrate the i) 2-fold and ii) 5-fold orientation of the 2D classes.

The 2D class classification of the boxed EA-AAV capsid particles resulted in two principle classes, identified from the final map as the near 2-fold (179 particles) (Fig. 2 Ai & Bi) and near 5-fold (112 particles) (Fig. 2 Aii & Bii) projections. In both classes the envelope observed around the particle demonstrated an irregular halo of density with a repeating diffuse “zig-zag” pattern ring. This pattern is likely the result of noise resulting from mismatched symmetry between the capsid (icosahedral) and envelope (presumed non-symmetric). But it may also be signal from protein(s) embedded within the lipid. It also noteworthy, that the boundary limits of the inner radius of the envelope most likely make contacts with the AAV2 capsid 3-fold protrusions.

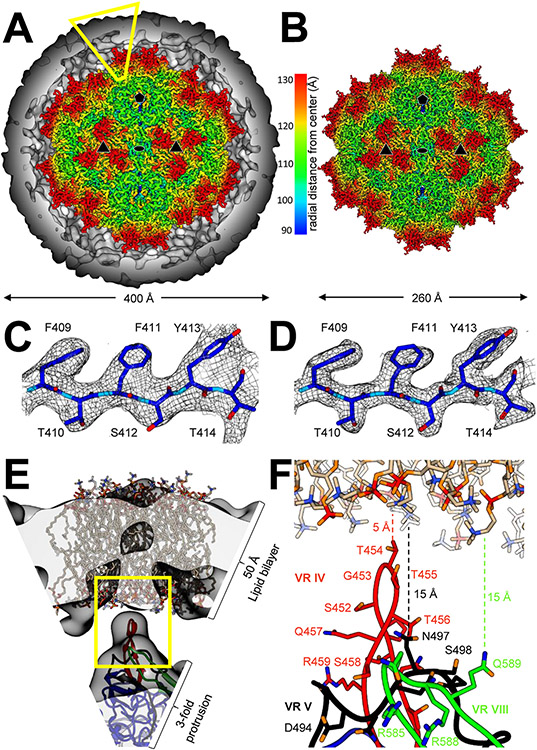

2.2. 3D reconstruction of envelope-associated AAV2 capsid

The 3D-reconstruction of the enveloped-associated and non-enveloped AAV capsids produced final maps with estimated 3.14 and 2.43 Å resolution, respectively (Fig. 3A and B, Table 1), based on the FSC0.143 cutoff (Supplemental Fig. S2). An AAV2 60mer VP3 model (Xie et al., 2002), generated from the non-enveloped capsids particles was fitted into both map and refined. The final maps had sufficient quality to build side chains into the density (Fig. 3C and D). The structure and final refinement statistics are given in Table 1. Consistent with the 2D classes the envelope thickness is ~5 nm (Fig. 3E), which is typical for a typical lipid bilayer (Nagle and Tristram-Nagle, 2000; Kuba et al., 2021). The cryo-EM map showed the closest approach of the capsid to the envelope at the 3-fold protrusions with a distance of ~5–10 Å (Fig. 3F). It was additionally noted that envelope density was “best” ordered around the 3-fold axes and substantially less ordered over the 5-fold axes. Complete density coverage over the 3-fold was observed at 3 sigma map contouring but near the 5-fold axes the map contour was 1 sigma to achieve coverage. We hypothesize, the protrusion around the 3-fold axes (consisting of variable regions IV, V, and VIII), with localized polar and positively charged amino acids, most likely facilitate to stabilize the lipid shell by interaction with the polar and negative charged lipid head groups in a non-specific manner (Fig. 3 E & F). Other capsid surfaces are not expected to participate in similar stabilization because the curvature of a lipid bilayer would likely not permit close contacts.

Fig. 3. Structural characterization of the EA-AAV capsid.

A) EA-AAV final map at 3.14 Å resolution, contoured to 3σ, overlaid onto the lipid envelope map at 10 Å resolution, contoured to 1σ. The capsid is colored in rainbow radial distance scale, while the envelope is colored in gray. The 2-fold (oval), 3-fold (triangle), and 5-fold (pentagon) are indicated to indicate the asymmetric unit of the capsid. The yellow open trapezoid highlights the region of the structure shown in E. B) Non-enveloped AAV capsid final map at 2.43 Å resolution, contoured to 3σ, using the same rainbow radial distance scale. C and D) The β-strand G (βG) for the enveloped (C) and non-enveloped AAV (D) contoured to 2σ to demonstrate map quality of the structures, respectively. E) Zoom in figure of trapezoid shown in (A), to demonstrate the fit of the structure. The low-resolution map (gray) is shown contoured to 1σ with a diacylglycerol and phospholipid (POPC) lipid membrane docked (CC 0.52 at 10 Å resolution) to demonstrate that a lipid bilayer can readily fit into the halo envelope density. Also shown is the docked enveloped AAV capsid structure (CC 0.92 at 10 Å resolution). The AAV2 VP3 variable regions (VRs) IV (red), V (black), and VIII (green) are as colored. F) Close-up of the yellow open boxed region of panel E, with side chains shown. Distances are given of the closest approach of VRs to the modeled lipid envelope as docked. Coloring of amino acid side chains is as follows: oxygen orange, phosphate red, nitrogen blue. Carbons are colored by VR as in left.

Table 1.

Refinement statistics of the enveloped and non-enveloped AAV2 structures.

| Enveloped capsid | Non-enveloped capsid | |

|---|---|---|

| Micrographs | 2133 | |

| Defocus (μm) | ||

| Minimum - Maximum | 1.59–3.50 | |

| Mean ± Standard Deviation | 2.54 ± 0.32 | |

| Particles | 291 | 46,289 |

| Resolution (Å) | 3.14 | 2.43 |

| Map to model CC | 0.812 | 0.823 |

| Ramachandran (%) | ||

| Outliers | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Allowed | 1.8 | 2.6 |

| Favored | 98.2 | 97.4 |

| Bond length RMSD (Å) | 0.011 | 0.008 |

| Bond angle RMSD (°) | 1.328 | 0.754 |

| Clashes per 10,000 atoms | 13.15 | 6.75 |

| Rotamer outliers (%) | 1.1 | 0.0 |

| Cβ deviations (%) | 0.6 | 0.0 |

| Cis-proline (%) | 3.0 | 3.0 |

Comparing the structure superposition of the enveloped- and non-enveloped AAV2 capsids resulted in a Cα RMSD distances of 0.32 Å, demonstrating no significant structural deviation between the capsids at the resolutions presented (Fig. 3C and D). Additionally, structural superposition of the EA-AAV capsid structure onto the previously deposited crystal (PDB: 1LP3) and cryo-EM structures (PDB: 6U0V) of the AAV2 capsid had Cα RMSD distances of 0.46 and 0.44 Å, respectively (Xie et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2019). Therefore, these observations would imply that EA-AAV capsids are not a structurally distinct class from their non-enveloped counterparts. However, the composition of the lipid envelope could not be determined. It is possible that additional membrane associated proteins (ie. MAAP or host proteins) are present but not resolved in the structure deposited, as indicated by the presence of minor protein impurities (Supplemental Fig. S1). Any such protein would likely have either low occupancy or symmetry mismatch to the icosahedral capsid.

3. Conclusion

This study presents the first evidence that AAV capsids, produced in Sf9 cells, contain a small but significant number of homogenous EA-AAV capsids (~1%). The expression system used demonstrates that the generation of these particles is producer cell independent, and therefore allows for production of EA-AAV capsids by scalable production systems such as the Sf9 baculovirus system used in this study, though the ability to purify them is probably limited to means which exclude affinity base chromatography (i.e. anion exchange, or AAV specific antibody/nanobody columns) (Rieser et al., 2021; Mietzsch et al., 2020).

Natural analogues to our observational EA-AAV capsid can be found in other non-enveloped viruses. Hepatitis A virus uses this strategy to evade the humoral host immune response (Feng et al., 2013); while both Norovirus and Rotavirus utilize this strategy when shed from stool to infect the next host to successfully evade host proteases within the gut/stool, and allows these viruses to achieve a higher multiple of infection in the next host (Santiana et al., 2019). We believe that EA-AAVs may behave in a similar manner to these non-enveloped viruses, as MAAP deletion variants are out competed by wtAAV2 by ~10 fold margin (Ogden et al., 2019), and in challenge to neutralizing antibodies in vivo retain higher infectivity (Meliani et al., 2017; György et al., 2014).

The EA-AAV capsid are ordered and as such their structure were determined to 3.14 Å resolution, and the capsid structure has been determined to be the same to their non-enveloped counterpart (2.43 Å resolution). The close contacts of the protrusions at the capsid 3-fold along with polar and positive charge amino acid clusters could imply that this region is involved in a non-specific interaction with the lipid envelope. Given the potential role of MAAP generating these small exosomes, we cannot rule out that MAAP is present in a symmetry mismatched manner and hence not visualized. In this view, it is possible that MAAP is inducing both exosome formation and recruitment of newly produced AAV particles.

It remains to be seen if the non-human cell line derived, such as Sf9, EA-AAV are infectious, relative to their human cell line derived counterpart. As subsequent EA-AAV infection likely utilizes host cell machinery for host cell uptake even if MAAP alone is sufficient to induce envelope formation. If the host machinery is required for EA-AAV host cell uptake, but not for production, this may provide a future roadmap for retargeting of capsids. Furthermore, the incorporation of proteins, peptides, and/or glycans into the EA-AAV membrane may aid in cell targeting. Therefore, we speculate that MAAP derived EA-AAV capsids may have therapeutic benefits of immune evasion and/or improved infectivity.

4. Materials & method

4.1. Production & purification

AAV2 VLPs were produced and harvested as previously described (Kohlbrenner et al., 2005). Briefly, by utilizing the Sf9 baculoviral expression system comprising the entire nucleotide sequence of the AAV2 VP open reading frame (including the entire MAAP and AAP open reading frames within) driven by the polyhedron promoter. Following the harvest, the cell pellet was lysed by freeze-thawing and subsequent use of a microfluidizer (Microfluidonics model LM-10). VLPs separated from cell lysate and PEG pellet were combined and purified by iodixanol gradient as previously described (Kohlbrenner et al., 2005) and visualized by SDS-PAGE for confirmation of purity and of VP protein composition. Fractions containing VP1/2/3 in the 25–40% iodixanol fractions were combined and buffer exchanged using a 150 kDa cutoff concentrator (Orbital Biosciences cat#: AP0715010) into Universal Buffer pH 7.4 (Bennett et al., 2017) and sample purity and concentration assessed by SDS-PAGE.

4.2. Negative stain electron microscopy

Negative stain electron microscopy (EM) was employed after purification to ensure the purity and integrity of the capsids. 5 μL of VLPs at 0.1 mg/mL were applied onto a glow-discharged copper grid (Electron Microscopy Supplies cat#: CFU-400Cu). The VLPs were incubated for 30 s before blotting dry. The grid was then washed 3 times for 10 s in filtered de-ionized water (>5 MΩ) then blotted dry again. The grid was then stained twice in 1% uranyl acetate for 5 s before blotting dry. Grids were imaged on an electron microscope (Thermo-Fisher model FEI Spirit) operated at 120kV.

4.3. Cryo-electron microscopy, particle reconstruction, and model building

Sample vitrification was done via plunge freezing (Thermo Fisher Scientific model Vitrobot Mark IV). 3 μL of VLPs at 1 mg/mL were pipetted onto a negatively glow-discharged Quantifoil copper grid (Electron Microscopy Supplies cat#: Q4100CR2-2NM). The VLPs were incubated for 5 min at 22 °C before blotting off excess sample and plunge freezing into liquid ethane. Cryo-EM images were collected on an electron microscope (Thermo-Fisher model FEI Titan Krios) operated at 300 kV equipped with a Gatan Energy Filter (Gatan model GIF). A slit width of 20 eV was set for energy filter. A nominal magnification of 81,000× was used, giving a physical pixel size of 1.1 Å (0.55 α per pixel at super-resolution mode). Movies were recorded with K3 camera operating in counting mode with dose rate of the electron beam set to 27 electrons per physical pixel per second on camera, corresponding to dosage of 22e−/Å2/sec. An accumulated dose of 34e− per Å2 on the sample was fractionated into a movie stack of 30 image frames. A total of 2133 movies were recorded within an 8 h session using the SerialEM software (Mastronarde, 2005). For each recorded movie, the frames were aligned for drift correction as previously described (Zheng et al., 2017). For the cryo-EM reconstruction, particles were excluded from the data set due to micrographs of poor quality, overlapping particles or damaged particles (especially in the case of enveloped capsids). 2D classification and 3D reconstruction of either enveloped or non-enveloped capsids were done imposing icosahedral symmetry in the cisTEM software suite while applying an inner mask 80 Å in diameter and an outer mask of 300 Å in diameter to suppress contribution from the VLP particle center or lipid envelope, respectively (Grant et al., 2018).

The final map was calculated using cisTEM flattened between 20-3.14 Å (high resolution) or from 20 to 10 Å (low resolution) (Grant et al., 2018) to either visualize the VLP structure or lipid envelope, respectively. Finally, the maps were normalized using the Mapman software suite (Kleywegt, Jones). Both the non-enveloped and EA capsid maps have been deposited into EMDB with accession codes EMD-24719 & EMD-24718, respectively. The atomic model was built and refined based the crystal structure of AAV2 (PDB: 1lp3) (Xie et al., 2002). The structure was refined in Coot (Emsley et al., 2010) and phenix (Afonine et al., 2012) iteratively. The atomic model for the non-enveloped and EA-AAV capsids have been deposited with the pdbid 7RWT & 7RWL respectively. The particles selected for the non-enveloped and EA-AAV capsid were collected from the same micrographs and the final data statistics are given in Table 1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We wish to dedicate this manuscript in the memory of the late Mavis Agbandje-McKenna, who always wanted to push the envelope of discovery of this virus. Figs. 2B and 3 were generated in Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004). The authors thank the UF-ICBR Electron Microscopy core (RRID:SCR_019146) for access to electron microscopes utilized for sample optimizing and screening.

Funding

The University of Florida COM and NIH grant R01 NIH GM082946 (to M.A.-M. and R.M.) provided funds for these research efforts at the University of Florida.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Joshua A. Hull: was responsible for sample production & purification, negative stain-EM, single particle cryo-electron microscopy data processing, structure interpretation, structure refinement. Mario Mietzsch: assisted with cryo-EM data collection and single particle reconstruction. Paul Chipnian: is responsible for freezing and screening cryo-EM samples and assisted with cryo-EM data collection. David Strugatsky: was responsible for cryo-EM data collection. Robert McKenna: is the senior author responsible for concept and design of the study, data interpretation, All author contributed to the writing and preparation of this manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: The University of Florida Research Foundation has filed, and licensed patent applications based on the findings described herein.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2021.09.010.

References

- Afonine AP, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH, 2012. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett A, Patel S, Mietzsch M, Jose A, Lins-Austin B, Yu JC, Bothner B, McKenna R, Agbandje-McKenna M, 15 September 2017. Thermal stability as a determinant of AAV serotype identity. Mol. Thera. Methods & Clinic. Develop 6, 171–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleker S, Sonntag F, Kleinschmidt J, 2005. Mutational analysis of narrow pores at the fivefold symmetry axes of adeno-associated virus type 2 capsids reveals a dual role in genome packaging and activation of phospholipase A2 activity. J. Virol 2528–2540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutin S, Monteilhet V, Veron P, Leborgne C, Benveniste O, Montus MF, Masurier C, 2012. Prevalence of serum IgG and neutralizing factors against adeno-associated virus (AAV) types 1, 2, 5, 6, 8, and 9 in the healthy population: implications for gene therapy using AAV vectors. Hum. Gene Ther 21 (6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buller RM, Rose JA, 1978. Characterization of adenovirus-associated virus-induced polypeptides in KB cells. J. Virol 331–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caccomo S, May 2019. FDA approves innovative gene therapy to treat pediatric patients with spinal muscular atrophy, a rare disease and leading genetic cause of infant mortality, [Online]. Available: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-innovative-gene-therapy-treat-pediatric-patients-spinal-muscular-atrophy-rare-disease. (Accessed 16 August 2021), 24. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng M, Dietz L, Gong Y, Eichler F, Nammour J, Ng C, Grimm D, Maguire CA, 2021. August 27. Neutralizing antibody evasion and transduction with purified extracellular vesicle-enveloped AAV vectors. Hum. Gene Ther https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/hum.2021.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore ZC, Havlik LP, Oh DK, Vincent HA, Asokan A, 2021. The membrane associated accessory protein is an adeno-associated viral egress factor, 17 June [Online]. Available: 10.1101/2021.06.17.448857. (Accessed 15 July 2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel SN, Mietzsch M, Tseng YS, Smith JK, Agbandje-McKenna M, 2021. Parvovirus capsid-antibody complex structures reveal conservation of antigenic epitopes across the family. Viral Immunol. 34 (1), 3–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K, 2010. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr 66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Hensley L, McKnight KL, Hu F, Madden V, Ping L, Jeong S-H, Walker C, Lanford RE, Lemon SM, 2013. A pathogenic picornavirus acquires an envelope by hijacking cellular membranes. Nature 496 (7445), 367–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A, 18 December 2017. FDA approves novel gene therapy to treat patients with a rare form of inherited vision loss [Online]. Available: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-novel-gene-therapy-treat-patients-rare-form-inherited-vision-loss. (Accessed 16 August 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Girod A, Wobus CE, Zadori Z, Ried M, Leike K, Tijssen P, Kleinschmidt JA, Hallek M, 1 May 2002. The VP1 capsid protein of adeno-associated virus type 2 is carrying a phospholipase A2 domain required for virus infectivity. J. Gen. Virol 83 (5), 973–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindasamy L, Padron E, McKenna R, Muzyczka N, Kaludov N, Chiorini JA, Agbandje-McKenna M, 2006. Structurally mapping the diverse phenotype of adeno-associated virus serotype 4. J. Virol 80 (23), 11556–11570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant T, Rohou A, Grigorieff N, 7 March 2018. cisTEM, user-friendly software for single-particle image processing. eLife 7, e35383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg B, Butler J, Felker GM, Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Pogoda JM, Provost R, Guerrero J, Hajjar RJ, Zsebo KM, 2015. Prevalence of AAV1 neutralizing antibodies and consequences for a clinical trial of gene transfer for advanced heart failure. Gene Ther. 23, 313–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- György B, Fitzpatrick Z, Crommentuijn MHW, Mu D, Maguire CA, August 2014. Naturally enveloped AAV vectors for shielding neutralizing antibodies and robust gene delivery in vivo. Biomaterials 35 (26), 7598–7609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- György B, Sage C, Indzhykulian AA, Scheffer DI, Brisson AR, Tan S, Wu X, Volak A, Mu D, Tamvakologos PI, Li Y, Fitzpatrick Z, Ericsson M, Breakefield XO, Corey, 1 February 2017. Rescue of hearing by gene delivery to inner-ear hair cells using exosome-associated AAV. Mol. Ther 25 (2), 379–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havlik LP, Simon KE, Smith JK, Kline KA, Tse LV, Oh DK, Fanous MM, Meganck RM, Mietzsch M, Kleinschmidt J, Agbandje-McKenna M, Asokan A, 2020. Coevolution of adeno-associated virus capsid antigenicity and tropism through a structure-guided approach. J. Virol 94 (19), e00976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose A, Mietzsch M, Smith JK, Kurian J, Chipman P, McKenna R, Chiorini J, Agbandje-McKenna M, 2018. High-resolution structural characterization of a new adeno-associated virus serotype 5 antibody epitope toward engineering antibody-resistant recombinant gene delivery vectors. J. Virol 93 (1), e01394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleywegt GJ and Jones TA, "Uppsala Software Factory - MAPMAN Manual," Uppsala Software Factory, 27 February 2003. [Online]. Available: https://www.csb.yale.edu/userguides/datamanip/uppsala/manuals/mapman_man.html. [Accessed 27 April 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlbrenner E, Aslanidi G, Nash K, Shklyaev S, Campbell-Thompson M, Byrne BJ, Snyder RO, Muzyczka N, Warrington KH, Zolotukhin S, 6 October 2005. Successful production of pseudotyped rAAV vectors using a modified baculovirus expression system. Mol. Therp 12 (6), 1217–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuba JO, Yu Y, Klauda JB, 2021. Estimating localization of various statins within a POPC bilayer. Chem. Phys. Lipids 236, 105074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large EE, Silveria MA, Zane GM, Weerakoon O, Chapman MS, 2021. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) gene delivery: dissecting molecular interactions upon cell entry. Viruses 13 (7), 1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastronarde DN, 2005. Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J. Struct. Biol 152 (1), 36–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meliani A, Boisgerault F, Fitzpatrick Z, Marmier S, Leborgne C, Collaud F, Sola MS, Charles S, Ronzitti G, Vignaud A, Wittenberghe L, Marolleau B, Jouen F, 2017. Enhanced liver gene transfer and evasion of preexisting humoral immunity with exosome-enveloped AAV vectors. Blood Adv. 1 (23), 2019–2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mével M, Bouzelha M, Leray A, Pacouret S, Guilbaud M, Penaud-Budloo M, Alvarez-Dorta D, Dubreil L, Gouin SG, Combal JP, Hommel M, Gonzalez-Aseguinolaza G, Blouin V, Moullier P, Adjali O, Deniaud D, Ayuso E, 2020. Chemical Modification of the Adeno-Associated Virus Capsid to Improve Gene Delivery, vol. 11. Royal Society of Chemistry, pp. 1122–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mietzsch M, Pénzes JJ, Agbandje-McKenna M, 2019. Twenty-five years of structural parvovirology. Viruses 11 (4), 362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mietzsch M, Smith JK, Yu JC, Banala V, Emmanuel SN, Jose A, Chipman P, Bhattacharya N, McKenna R, Agbandje-McKenna M, 2020. Characterization of AAV-specific affinity ligands: consequences for vector purification and development strategies. Mol. Therp. Methods Clinic. Develop 19, 362–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagle JF, Tristram-Nagle S, 2000. Structure of lipid bilayers. Biochem. et Biophys. Acta 1469 (3), 159–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden PJ, Kelsic ED, Sinai S, Church GM, 29 November 2019. Comprehensive AAV capsid fitness landscape reveals a viral gene and enables machine-guided design. Science 366 (6469), 1139–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE, 1 July 2004. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem 25 (13), 1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raposo G, Stoorvogel W, 18 February 2013. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesides, and friends. JCB (J. Cell Biol.) 200 (4), 373–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieser R, Koch J, Facciioli G, Richter K, Menzen T, Biel M, Winter G, Michalakis S, 2021. Comparison of different liquid chromatography-based purification strategies for adeno-associated virus vectors. Pharmaceutics 13 (5), 748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiana M, Ghosh S, Ho BA, Rajasekaran V, Du W-L, Mutsafi Y, De Jésus-Diaz DA, Sosnovtsev SV, Levenson EA, Parra GI, Takvorian PM, Cali A, Bleck C, Vlasova AN, Saif LJ, Patton JT, Lopalco P, Corcelli A, Green KY, Altan-Bonnet N, 2019. Vesicle-cloaked virus dusters are optimal units for inter-organismal viral transmission. Cell Host Microbe 24 (2), 208–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Q, Bu W, Bhatia S, Hare J, Somasundaram T, Azzi A, Chapman MS, 6 August 2002. The atomic structure of adeno-associated virus (AAV-2), a vector for human gene therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Unit. States Am 99 (16), 10405–10410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao T, Zhou X, Zhang C, Yu X, Tian Z, Zhang L, Zhou D, 2017. Site-specific PEGylated adeno-associated viruses with increased serum stability and reduced immunogenicity. Molecules 22 (7), 1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Cao L, Cui M, Sun Z, Hu M, Zhang R, Stuart W, Zhao X, Yang Z, Li X, Sun Y, Li S, Ding W, Lou Z, Rao Z, 2019. Adeno-associated virus 2 bound to its cellular receptor AAVR. Nat. Microbiol 4, 675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng SQ, Palovcak E, Armache J-P, Verba KA, Cheng Y, Agard DA, 2017. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 14 (4), 331–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.