Abstract

Background:

Depressive symptoms are common in patients seeking medication treatment for opioid use disorder (MOUD treatment) and decrease quality of life but have been inconsistently related to opioid treatment outcomes. Here, we explore whether depressive symptoms may only be related to adverse treatment outcomes among individuals reporting high opioid use-related coping motives (i.e., use of opioids to change affective states) and high trait impulsivity, two common treatment targets.

Methods:

Patients seeking MOUD treatment (N = 118) completed several questionnaires within two weeks of their treatment intake. Treatment outcomes (opioid-positive urine screens and days retained in treatment) were extracted from treatment records. Moderation analyses controlling for demographic characteristics and main effects were conducted to explore interaction effects between depressive symptoms and two distinct moderators.

Results:

Depressive symptoms were only related to opioid use during early treatment among patients reporting high opioid use-related coping motives (B = 2.67, p = .004) and patients reporting high trait impulsivity (B = 2.01, p = .039). Further, depressive symptoms were only inversely related to days retained among individuals with high opioid use-related coping motives (B = −10.12, p = .003).

Conclusions:

Individuals presenting to treatment with opioid-related coping motives and/or impulsivity in the context of depressive symptoms may confer unique risk for adverse treatment outcomes. Clinicians may wish to consider these additive risk factors when developing their treatment plan.

Keywords: opioid use disorder, depression, methadone, treatment, moderation

1. Introduction

The United States is experiencing a nationwide opioid crisis. In 2021, 80,816 of the drug-related deaths involved an opioid – a fourfold increase in the death rate from opioids since 2000(Centers for Disease Control, 2022; Humphreys et al., 2022). A key resource during this crisis has been treatment programs for people living with opioid use disorder (OUD; e.g., using methadone and buprenorphine), which have been shown to be efficacious for reducing substance use, preventing withdrawal, and reducing risk of future overdose(Mattick et al., 2014; Wakeman et al., 2020). However, discontinuation of treatment remains high in many settings(Timko et al., 2016). Within this context, there is an urgent need to better understand factors that influence opioid use and retention during OUD treatment.

The presence of psychiatric comorbidities complicates OUD treatment. For example, a substantial proportion of people with OUD also present with depressive symptoms, which reduce well-being and quality of life(Conway et al., 2006; Rogers et al., 2021). However, depressive symptoms have inconsistently been related to OUD treatment outcomes, such as in-treatment opioid use and treatment retention(Ghabrash et al., 2020). Although some research has found a link between depressive symptoms and OUD treatment retention as well as continued opioid use among those in treatment for OUD(Brewer et al., 1998; Litz & Leslie, 2017), other research has not found such associations(Rosic et al., 2017).

We contend these mixed findings indicate the presence of unassessed moderator variables that strengthen or weaken the association between depressive symptoms and OUD treatment retention as well as continued opioid use during early treatment. Specifically, in this hypothesis-generating study, we tested two potential moderators of the depression-OUD treatment outcomes link among people living with OUD: opioid use as a coping mechanism and trait impulsivity. We hypothesized these moderators would interact with depressive symptoms among people with OUD to decrease the number of days retained in treatment and increase continued opioid use during early treatment. We selected these moderators because they are modifiable treatment targets addressed in existing psychosocial interventions.

1.1. Potential Moderators of the Depression/OUD-Treatment Outcomes Relationship

1.1.1. Opioid use-related coping motives.

Although individuals may use psychoactive substances (including opioids) for various reasons(Schepis et al., 2020), a subset of individuals in treatment for OUD may have enhanced emotional vulnerability, including symptoms of depression(Lister et al., 2022) and may use opioids to cope with unpleasant emotional states(Gold et al., 2020). Consequently, relapse prevention often incorporates coping-skills training for high-risk situations, including unpleasant aversive states(Marlatt, 1996). Coping motives are also a treatment target in Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) to build distress-tolerance skills, which provides specific guidance for buffering distressing states that maintain addictive behaviors(Linehan, 2014). Depressive symptoms and use of opioids to cope may be associated with increased risk for adverse opioid treatment outcomes. However, no studies have tested this hypothesis among patients receiving medication treatment for OUD.

1.1.2. Trait impulsivity.

Impulsivity is a multifaceted construct that involves a predisposition toward rapid, unplanned reactions to internal or external stimuli without regard to the negative consequences of these reactions(Moeller et al., 2001). It is also a key feature of OUD initiation and maintenance, and undermines treatment retention and outcomes(Loree et al., 2014; Tarter et al., 2003). Interventions including Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)(S. Hayes et al., 2006), DBT(Linehan, 2014) and mindfulness-based interventions(Garland & Howard, 2018) help individuals become more aware of their reactions to high-risk situations and act with intentionality, which can reduce impulsive behaviors. Individuals with greater impulsivity who also have symptoms of depression may be at particular risk for shorter treatment retention and continued use of opioids early in treatment. In the current research, we test this moderation model among people in treatment for OUD. Specifically, we hypothesized that impulsivity interacts with depressive symptoms to make it more difficult for patients to adhere to treatment.

1.2. Overview of the current research

The purpose of this current study was to examine whether two distinct, clinically-relevant, modifiable treatment targets – opioid use-related coping motives and trait impulsivity – moderate the negative relation between depressive symptoms and two treatment outcomes: early opioid abstinence (i.e., proportion of opioid-free urine screens during the first 30 days of treatment), and number of days retained in treatment over one year. We hypothesized that the relation between depressive symptoms and continued opioid use during early treatment and one-year treatment retention will only be significant among those with high opioid-related coping motives and high trait impulsivity. Hypotheses and the data analytic plan were registered on Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/yns7t/.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants (N =118) were patients enrolled in an OUD medication treatment program located in an urban, Midwestern community who consented to participate in the study. All patients were receiving methadone treatment. The clinic location is in a medically underserved and health professional shortage area (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2022). Patients attended individual therapy and group therapy and completed the survey within two weeks of their intake; treatment outcomes were tracked for up to one-year post-intake. Patients received a $25 gift card and bus-fare for participation. This research was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Wayne State University (Reviewing, Protocol # 1607015098) and Rutgers University (Relying, Study ID: Pro2021000859).

2.2. Measures

Demographics and substance use characteristics.

Demographic and opioid-related characteristics included gender, race, age at time of survey, income (assessed as money received in the past 30 days from all sources, including employment, unemployment insurance, public assistance, social security, family and friends, and illegal activities), education, age at first opioid use, history of injection use, prior treatment history, and methadone dose at stabilization. We also collected descriptive information about use of other substances (i.e., cocaine, marijuana, benzodiazepines) during the first month of treatment.

Depressive symptoms.

Past-week depressive symptoms were measured using the 7-item depression subscale of the DASS-21, which includes a four-point scale ranging from “Never” to “Almost Always”(Antony et al., 1998). Higher scores indicate higher depressive symptoms. Internal consistency was strong in this sample (α=.90).

Opioid use-related coping motives.

A three-item opioid use-related coping motive measure(Lister et al., 2022), adapted from the Drinking Motives Questionnaire (Cooper et al., 1992) was used and demonstrated good internal consistency (α=.81). Items included 1) I typically used heroin to help me relax, 2) I often used heroin to help forget my worries, and 3) I frequently used heroin to help cheer me up when I was in a bad mood. Participants responded on a 7-point scale with anchor points of “Strongly Disagree” and “Strongly Agree”. Higher scores indicate greater coping motives.

Trait impulsivity.

The 15-item BIS-15 scale(Spinella, 2007), which measures broad impulsivity and includes risk-taking items, was used in this study. The measure demonstrated good internal consistency (α=.84). It utilizes a four-point scale ranging from “Rarely” to “Almost Always or Always” and higher scores indicate greater impulsivity.

2.3. Outcome measures

Two OUD treatment outcome measures were included in this study: 1) Continued opioid use during early treatment, or percentage of opioid-positive urine drug screens (UDS) in the first month, and 2) Treatment retention, measured continuously as number of days retained over one year, and censored at 365 days.

2.4. Data analysis

Data were analyzed in SPSS, version 27(IBM Corp., 2020). To test the hypothesized moderation models, we used Hayes’ (2022) PROCESS macro, version 4.1 (A. Hayes, 2017). Prior to all analyses, assumptions were checked and determined to be met. The income variable contained outliers (>3.29 standard deviations above or below the mean) and was winsorized. Some scales contained a very small amount of missing data (1–3 cases); continuous data were imputed using expectation maximization(Musil et al., 2002) and binary missing data were estimated by substituting missing values with Bernoulli-distributed random values(Bernaards et al., 2007). First, we conducted descriptive and bivariate analyses to examine relationships between depressive symptoms and treatment outcomes.

Next, we conducted moderation analyses using PROCESS version 4.1(A. Hayes, 2017) to explore whether depressive symptoms/opioid use and depressive symptoms/treatment retention relationships only held among patients with specific risk factors (i.e., high opioid use-related coping motives, high trait impulsivity). Simple slopes analysis was used to probe interactions, in which we examined effects of depressive symptoms on outcomes at 1 standard deviation above and below the mean, and at the mean. In all analyses, age, gender, past-30 day income, and having a high school diploma were included as covariates due to previous work (Huhn et al., 2019; Parlier-Ahmad et al., 2022; Proctor et al., 2015) highlighting the clinical relevance of these variables for depressive symptoms and OUD treatment outcomes, and all models adjusted for main effects. Estimates reported below reflect adjusted, unstandardized beta coefficients.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive information

Descriptive information is presented in Table 1. On average, 70.7% of UDS in the first month (SD = 37.6%, Range = 0%–100%) were positive for opioids (at the patient level). Patients were retained in treatment for a mean ± SD of 171.9 ± 129.3 days. With regard to other substance use, 24.4% of screens were positive for cocaine, 22.5% were positive for marijuana, and 10.9% of screens were positive for benzodiazepines, at the patient level.

Table 1.

Descriptive information

| M (SD) or N (%) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Demographics | |

| Female Gender | 49 (41.5%) |

| Black or African American Race | 75 (63.6%) |

| Age | 52.7 (13.6) |

| High school diploma or GED | 83 (70.3%) |

| Past 30-day Incomea | $1,412.48 ($1,160.37) |

| Opioid Use and Treatment History | |

| Age of first opioid use | 24.3 (9.4) |

| Age of first methadone treatment | 40.4 (13.0) |

| History of injection opioid use | 52 (44.1%) |

| Prior methadone treatment (before current treatment episode) | 92 (78.0%) |

| Prior buprenorphine treatment | 28 (23.7%) |

| Prior heroin detoxification treatment | 79 (66.9%) |

| Methadone dose at stabilization | 63.3 (24.4) |

| Individual Characteristics | |

| Depressive symptoms | 6.7 (4.4) |

| Trait impulsivity | 36.6 (7.3) |

| Opioid use-related coping motives | 16.3 (4.1) |

| Outcomes | |

| Proportion of opioid-positive screens (first month) | 70.7% (37.6%) |

| Days retained in treatment (censored at 365 days) | 171.9 (129.3) |

| Other Substance Use | |

| Percentage of cocaine-positive screens (first month) | 24.4% (36.4%) |

| Percentage of marijuana-positive screens (first month) | 22.5% (37.7%) |

| Percentage of benzodiazepine-positive screens (first month) | 10.9% (24.6%) |

Income was assessed as money received in the past month from all sources, including employment, unemployment insurance, public assistance, social security, family and friends, and illegal activities. This variable contained outliers and was winsorized.

Nearly half of patients (n = 52, 44.1%) reported a lifetime history of injection opioid use. Although depressive symptoms were unrelated to percentage of opioid-positive screens during the first month (r = .09, p = .316), symptoms were related to number of days retained (r = −.18, p = .047). Patients with a higher percentage of opioid-positive screens during the first month of treatment were retained fewer days (r = −.25, p = .006).

3.2. Moderating effects of opioid use-related coping motives on depressive symptoms and OUD treatment outcomes

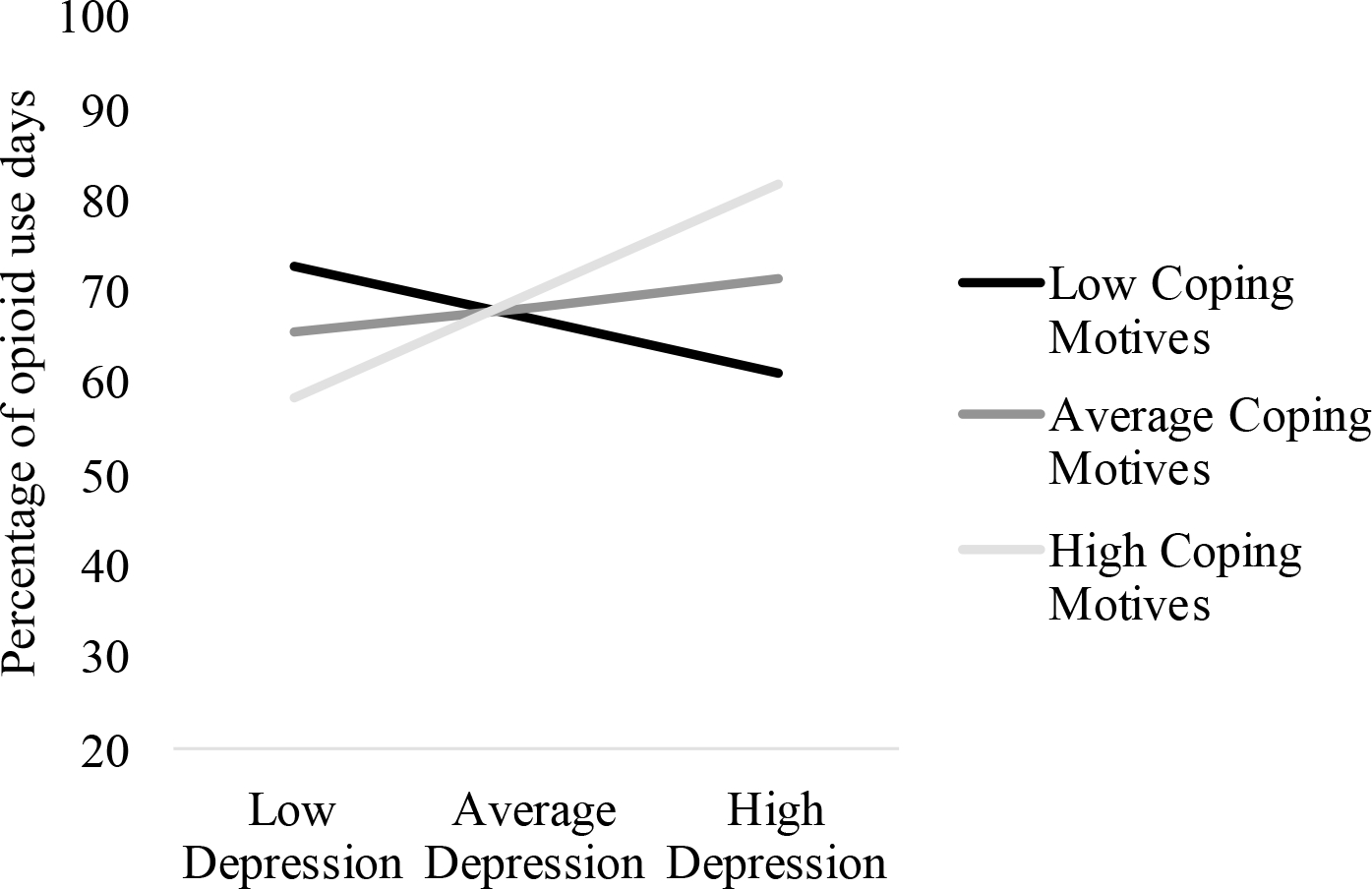

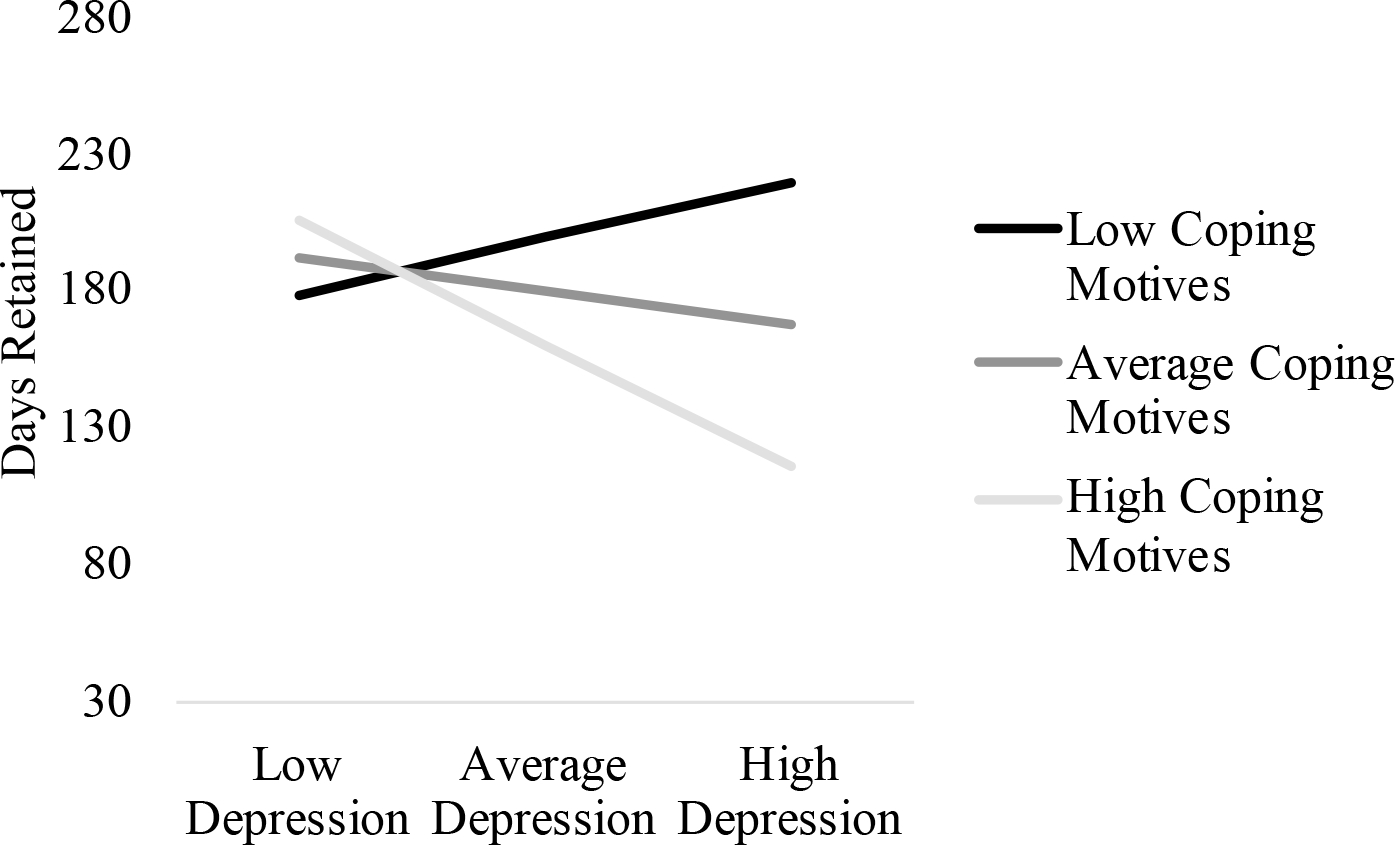

As shown in Figures 1 and 2 and Tables 2 and 3, interactions of depressive symptoms with opioid use-related coping motives were significant for both proportion of opioid-positive UDS (B = 0.48, p = .022) and days retained in treatment (B = −1.80, p = .019). Follow-up analyses revealed that depressive symptoms were related to more-frequent opioid-positive UDS only when coping motives were +1 SD above the mean (B = 2.67, p = .004) but unrelated among patients reporting coping motives at or −1 SD below the mean (ps > .353). Similarly, depressive symptoms were only related to fewer days retained in treatment among patients with coping motives +1 SD above the mean (B = −10.12, p = .003), but unrelated among patients with coping motives at or −1 SD below the mean (ps > .355).

Figure 1.

Interaction between Depressive Symptoms and Coping Motives on Proportion of Opioid Use Days

Figure Legend. Depressive symptoms were significantly related to proportion of opioid use days at high coping motives (i.e., 1 standard deviation above the mean; p = .004), but were unrelated to depressive symptoms at low (i.e., 1 standard deviation below the mean) and average coping motives (ps > .353).

Figure 2.

Interaction between Depressive Symptoms and Coping Motives on Days Retained

Figure Legend. Depressive symptoms were significantly related to days retained at high coping motives (i.e., 1 standard deviation above the mean, p = .003), but were unrelated to depressive symptoms at low and average coping motives (ps > .355).

Table 2.

Interactive Effects on Proportion of Opioid Use Days

| No interaction term | With interaction term | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Unstandardized Estimate (95% CI) | t-value | p-value | Unstandardized Estimate (95% CI) | t-value | p-value | |

|

| ||||||

| Model 1: Coping Motives | ||||||

| Depressive symptoms | 1.46 (−0.04, 2.95) | 1.93 | .056 | 0.68 (−0.92, 2.28) | 0.84 | .403 |

| Coping Motives | 0.03 (−1.65, 1.71) | 0.04 | .971 | 0.37 (−1.30, 2.04) | 0.44 | .662 |

| Depressive Symptoms × Coping Motives | - | - | - | 0.48 (0.07, 0.90) | 2.32 | .022* |

| Covariates | ||||||

| Female Gender | −20.47 (−35.04, −5.89) | −2.78 | .006* | −20.25 (−34.55, −5.95) | −2.81 | .006* |

| Age | 0.62 (0.07, 1.17) | 2.22 | .029* | 0.67 (0.13, 1.21) | 2.44 | .017* |

| High school degree | −2.69 (−16.91, 11.53) | −0.37 | .709 | −3.69 (−17.66, 10.29) | .−0.52 | .602 |

| Past 30-day Incomea | −0.01 (−0.01, 0.001) | −1.75 | .083 | −0.01 (−0.01, 0.0001) | −1.96 | .053 |

| Model 2: Impulsivity | ||||||

| Depressive symptoms | 0.97 (−0.65, 2.58) | 1.19 | .238 | 0.75 (−0.86, 2.35) | 0.92 | .360 |

| Impulsivity | 0.73 (−0.29, 1.74) | 1.42 | .159 | 0.72 (−0.28, 1.73) | 1.43 | .155 |

| Depressive Symptoms × Impulsivity | - | - | - | 0.17 (0.0002,0.34) | 1.98 | .050* |

| Covariates | ||||||

| Female Gender | −21.98 (−36.53, −7.43) | −2.99 | .003* | −21.86 (−36.22, −7.50) | −3.02 | .003* |

| Age | 0.69 (0.15, 1.23) | 2.52 | .013* | 0.73 (0.19, 1.26) | 2.68 | .009* |

| High school degree | −2.14 (−16.23, 11.95) | −0.30 | .764 | −2.06 (−15.96, 11.85) | −0.29 | .770 |

| Past 30-day Incomea | −0.01 (−0.01, 0.001) | −1.71 | 090 | −0.01 (−0.01, 0.001) | −1.64 | .104 |

Income was assessed as money received in the past month from all sources, including employment, unemployment insurance, public assistance, social security, family and friends, and illegal activities. This variable contained outliers and was winsorized.

Table 3.

Interactive Effects on Days Retained

| No interaction term | With interaction term | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Unstandardized Estimate (95% CI) | t-value | p-value | Unstandardized Estimate (95% CI) | t-value | p-value | |

|

| ||||||

| Model 1: Coping Motives | ||||||

| Depressive symptoms | −5.62 (−11.06, −0.18) | −2.05 | .043* | −2.74 (−8.59, 3.11) | −0.93 | .355 |

| Coping Motives | −3.43 (−9.55, 2.68) | −1.11 | .268 | −4.69 (−10.78, 1.39) | −1.53 | .129 |

| Depressive Symptoms × Coping Motives | - | - | - | −1.80 (−3.30, −0.30) | −2.37 | .019* |

| Covariates | ||||||

| Female Gender | 44.68 (−8.42, 97.77) | 1.67 | .098 | 43.87 (−8.16, 95.90) | 1.67 | .098 |

| Age | −0.22 (−2.23, 1.80) | −0.21 | .831 | −0.40 (−2.38, 1.58) | −0.40 | .690 |

| High school degree | 16.38 (−35.41, 68.17) | 0.63 | .532 | 20.11 (−30.73, 70.95) | 0.78 | .435 |

| Past 30-day Incomea | 0.02 (0.003, 0.04) | 2.31 | .023* | 0.03 (0.01, 0.05) | 2.54 | .013* |

| Model 2: Impulsivity | ||||||

| Depressive symptoms | −5.82 (−11.79, 0.14) | −1.94 | .056 | −5.55 (−11.59, 0.48) | −1.82 | .071 |

| Impulsivity | −0.46 (−4.21, 3.29) | −0.24 | .809 | −0.45 (−4.21, 3.31) | −0.24 | .812 |

| Depressive Symptoms × Impulsivity | - | - | - | −0.21 (−0.86, 0.43) | −0.65 | .517 |

| Covariates | ||||||

| Female Gender | 43.02 (−10.74, 96.77) | 1.59 | .116 | 42.88 (−11.03, 96.78) | 1.58 | .118 |

| Age | 0.003 (−2.00, 2.01) | 0.003 | .998 | −0.04 (−2.06, 1.98) | −0.04 | .968 |

| High school degree | 17.81 (−34.23, 69.86) | 0.68 | .499 | 17.71 (−34.48, 69.90) | 0.67 | .503 |

| Past 30-day Incomea | 0.02 (0.002, 0.04) | 2.21 | .029* | 0.02 (0.002, 0.04) | 2.18 | .032* |

Income was assessed as money received in the past month from all sources, including employment, unemployment insurance, public assistance, social security, family and friends, and illegal activities. This variable contained outliers and was winsorized.

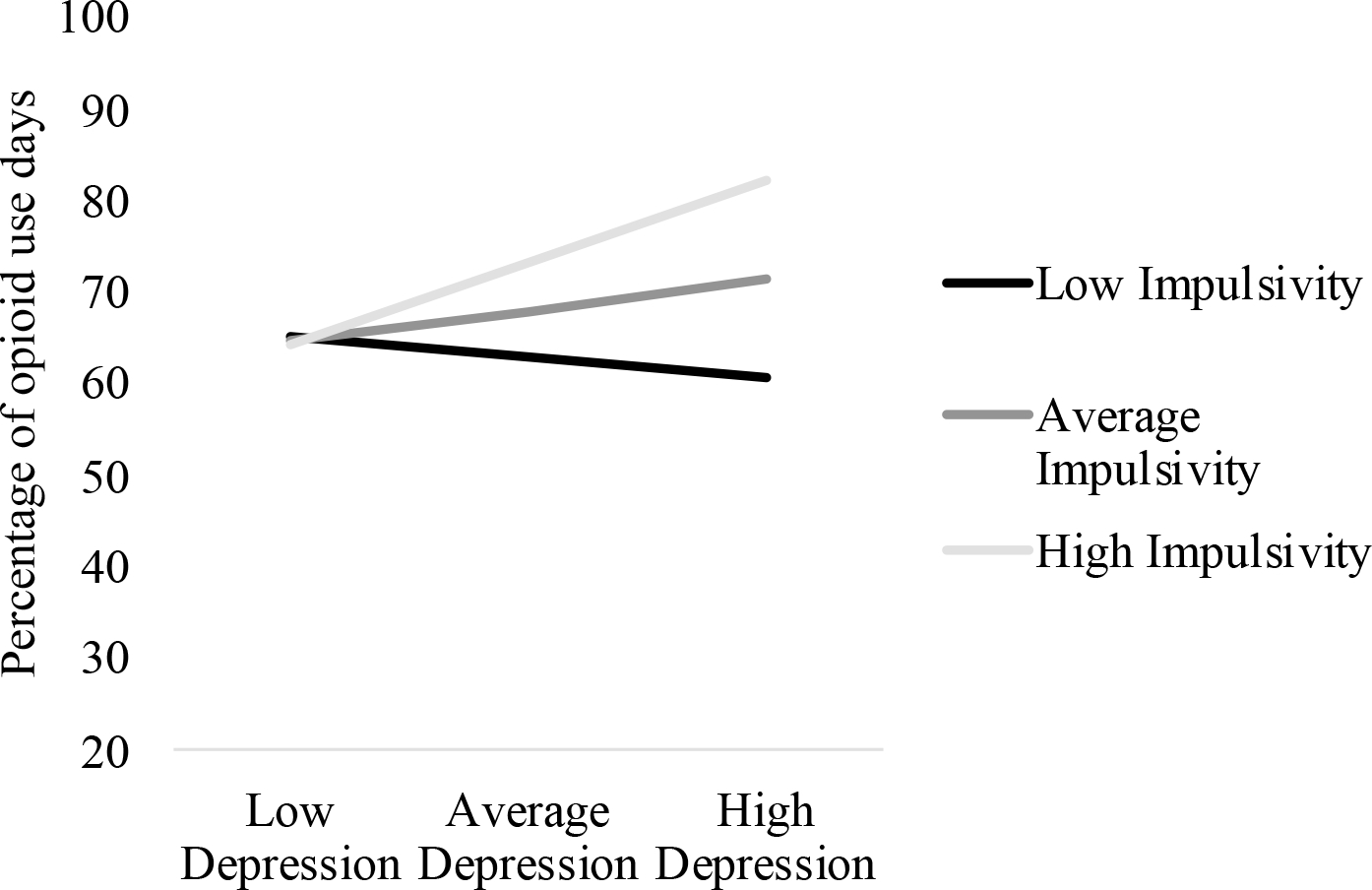

3.3. Moderating effects of trait impulsivity on depressive symptoms and OUD treatment outcomes

The interaction of depressive symptoms and trait impulsivity on the proportion of opioid-positive UDS was significant (see Table 2, Figure 3), whereas the effect on days retained in treatment was non-significant (Table 3). Follow-up analyses revealed that depressive symptoms were only positively related to opioid-positive screens for trait impulsivity +1 SD above the mean (B = 2.01, p = .039), but unrelated at average or −1 SD below the mean of trait impulsivity (ps > .360).

Figure 3.

Interaction between Depressive Symptoms and Impulsivity on Proportion of Opioid Use Days

Figure Legend. Depressive symptoms were significantly related to proportion of opioid use days at high impulsivity (p = .039), but were unrelated to depressive symptoms at low and impulsivity (ps > .360).

4. Discussion

People with OUD are a high-risk population for overdose death and other morbidities, although engagement in opioid agonist treatment can reduce opioid-related harms. Because many people in OUD treatment discontinue care earlier than recommended by their treatment provider, the current research assessed whether specific, modifiable treatment targets moderate the influence of depressive symptoms on two OUD treatment outcomes (continued opioid use during early treatment, retention). This analysis yields findings that could help to clarify the conditions under which depressive symptomatology may undermine OUD treatment outcomes, and identify relevant areas for future study, particularly regarding adjunctive psychosocial interventions that may promote abstinence and retention.

In line with our hypotheses, the association between depressive symptoms and OUD treatment outcomes was moderated by other treatment targets, but differed depending on the treatment outcome measure. The most consistent interactive relation was observed for opioid use-related coping motives and depressive symptoms. Specifically, we observed a significant interaction in the analyses of early-treatment opioid use as well as treatment retention. By comparison, trait impulsivity and depressive symptoms only interacted to influence opioid-positive urine drug test results. Taken together, our findings imply that the influence of depressive symptoms on OUD treatment outcomes may depend on the presence of other individual differences, a finding that should be explored more in future work.

4.1. Implications

The association between depressive symptoms and treatment outcomes has been debated(Ghabrash et al., 2020). The current findings provide support for the idea that opioid use-related coping motives moderate the relationship between depressive symptoms and methadone treatment outcomes. This finding extends literature identifying the important role that motives to cope with depressive symptoms have among people in methadone treatment(Mahu et al., 2021), while reinforcing that opioid use-related coping motives may interact with other factors in predicting methadone treatment outcomes(McHugh et al., 2013). Moreover, this finding requires refinement of the self-medication hypothesis(Khantzian, 1997), which has generated limited empirical support(Lembke, 2012). Specifically, self-medication may result from the combination of a negative affective state and a motive to attenuate these emotions through opioid use. Lastly, the present results highlight the potential importance of further exploring treatment protocols that address coping motives for opioid use, such as relapse prevention and DBT.

The interaction between depressive symptoms and trait impulsivity produced a mixed effect on methadone treatment outcomes. Although high levels of depressive symptoms and impulsivity moderated greater opioid use early in treatment, no moderating effect was observed for treatment retention. This discrepancy may arise because first-month opioid use is an early treatment outcome, whereas retention is a longer-term outcome. Treatment for OUD can create structure and reduce impulsive behaviors by helping patients 1) manage high-risk situations, 2) identify alternative activities (e.g., stable employment, attending support meetings) to substance use that provide structure and stability, and 3) identify affective and physical states which may prompt a patient to act. Thus, trait impulsivity may demonstrate adverse effects during early treatment, prior to a sufficient dose of psychosocial intervention and as an individuals is being stabilized on their methadone dose, that dissipates when considering longer-term outcomes. However, it should be noted that effects related to impulsivity were small, and this result should be replicated in future work.

Depressive symptoms should be treated in the context of substance use treatment to maximize patient quality of life and reduce distress, regardless of whether symptoms interfere with OUD treatment. However, findings from this study have implications for reducing substance use among individuals with co-occurring OUD and depression. Specifically, those with depressive symptoms who report opioid use to cope with their depressive symptoms may benefit from adjunctive interventions that foster alternative methods of coping and/or interventions that foster distress tolerance and acceptance of aversive affective states. If future work also suggests that depressive symptoms confer unique risk among individuals with other underlying risk factors (such as coping motives or impulsivity), it may be beneficial to test the efficacy of interventions that foster tolerance of distress and reduce impulsivity, such as DBT(Rezaie et al., 2021) and ACT(S. Hayes et al., 2006) among persons with co-occurring OUD and depression.

4.2. Limitations

Some limitations of the current research should be noted. First, this study only collected data at one opioid treatment program in a medically underserved urban area of a Midwestern state. This strategy allowed increased understanding of a group that has been historically marginalized in the United States, and patients in our clinic share many similarities to those attending opioid treatment programs in other underserved urban areas. However, it is possible that our tests may have been influenced by demographic characteristics of our sample, and the frequency and degree of patients’ measured treatment targets, and may not generalize to other treatment settings or populations. We recommend moderation models be replicated in different treatment settings and geographic areas. We also recommend that future studies be conducted with larger samples to explore moderation models specific to patient sub-populations to help identify treatment needs of particular groups (e.g., women’s specialty programs, young-adult specialty programs, different cultural groups). Unfortunately, the sample size employed in the current study was relatively small and thus we were not able to probe these interactions. Additionally, results only generalize to patients who elected to participate in the study, and may not generalize to those who did not attend their study appointment.

We also suggest testing similar moderation models using mental health measures other than depressive symptoms, such as symptoms of PTSD or anxiety, because both have similarly high rates among patients with OUD and would provide insight into whether our models are more general to negative emotional states or are specific to depression. Future work may also use intensive longitudinal designs to test mediation effects between constructs of interest (i.e., whether individuals with high trait-level coping motives and impulsivity experience greater opioid use following increases in depressive symptoms). Longitudinal analyses would also allow researchers to control for time-varying changes in methadone dose (i.e., gradually increasing methadone dose as an individual is stabilized during early treatment). Doing so would also address a limitation in the present study (i.e., that we did not control for changes in dose during early stabilization). Finally, urine screens were administered approximately weekly; thus, it is possible that use of certain short-acting opioids was not captured. Unfortunately, we do not have urine screen information for individuals who were discharged from treatment, precluding analyses of long-term substance use outcomes.

4.3. Conclusions

The existing literature provides mixed findings on the influence of depressive symptoms to treatment outcomes. As a result, OUD treatment protocols lack a clear priority of how and when to address depressive symptoms in integrated approaches, aside from those seeking to provide care for any comorbid disorders. To test whether other factors have an influential role and identify findings that can inform treatment protocols, we examined two treatment targets as potential moderators of the depressive symptoms to OUD treatment outcome relationship. Our findings reveal that patients with high levels of depressive symptoms who also have high levels of coping motives for their opioid use and those with high trait impulsivity, are at greater risk for adverse treatment outcomes. We recommend that clinical directors and treatment researchers identify strategies to better identify these high-risk groups and integrate or adapt existing treatment protocols to address depressive symptoms under these conditions.

Highlights.

Depressive symptoms were related to opioid use/retention in those with high coping motives

Depressive symptoms were unrelated to opioid use or retention at low coping motives

Depressive symptoms were related to opioid use among those with high impulsivity

Depressive symptoms were unrelated to opioid use or retention at low impulsivity

Funding sources

This work was supported by a research grant (to JJL) from the Wayne State University Provost & Vice President for Academic Affairs; Gertrude Levin Endowed Chair in Addiction and Pain Biology (MKG), Lycaki/Young Funds (State of Michigan); and Detroit Wayne Integrated Health Network. JDE is supported by National Institutes of Health and the National Institute on Drug Abuse T32 DA007209 (Bigelow/Strain/Weerts). The funding sources had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Antony M, Bieling P, Cox B, Enns M, & Swinson R (1998). Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical groups and community sample. Psychological Assessment, 10, 176–181. [Google Scholar]

- Bernaards C, Belin T, & Schafer J (2007). Robustness of a multivariate normal approximation for imputation of incomplete binary data. Statistics in Medicine, 26(6), 1368–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer D, Catalano R, Haggerty K, Gainey R, & Fleming C (1998). RESEARCH REPORT A meta-analysis of predictors of continued drug use during and after treatment for opiate addiction. Addiction, 93(1), 73–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. (2022). U.S. Overdose Deaths In 2021 Increased Half as Much as in 2020 – But Are Still Up 15%. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2022/202205.htm

- Conway K, Compton W, Stinson F, & Grant B (2006). Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(2), 247–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M, Russell M, Skinner J, & Windle M (1992). Drinking motives questionnaire. PsycTESTS. [Google Scholar]

- Garland E, & Howard M (2018). Mindfulness-based treatment of addiction: Current state of the field and envisioning the next wave of research. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 13(1), 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghabrash M, Bahremand A, Veileuz M, Blais-Normandin G, Chicoine G, Sutra-Cole C, Kaur N, Ziegler D, Dubreucq S, Juteau L, & Lestage L (2020). Depression and outcomes of methadone and buprenorphine treatment among people with opioid use disorders: A literature review. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 16(2), 191–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold A, Stathopoulou G, & Otto M (2020). Emotion regulation and motives for illicit drug use in opioid-dependent patients. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 49(1), 74–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S, Luoma J, Bond F, Masuda A, & Lillis J (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huhn A, Berry M, & Dunn K (2019). Sex-based differences in treatment outcomes for persons with opioid use disorder. American Journal on Addictions, 28(4), 246–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Shover C, Andrews C, Bohnert A, Brandeau M, Caulkins J, Chen J, Cuélla M, Hurd Y, Juurlink D, Koh H, Krebs E, Lembke A, Mackey S, Ouellette L, Suffoletto B, & Timko C (2022). Responding to the opioid crisis in North America and beyond: Recommendations of the Stanford-Lancet commission. The Lancet Commissions, 399(10324), 555–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. (2020). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. (27.0) [Computer software]. IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian E (1997). The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 4(5), 231–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lembke A (2012). Time to abandon the self-medication hypothesis in patients with psychiatric disorders. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 38(6), 524–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M (2014). DBT Skills training manual. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lister J, Yoon M, Nower L, Ellis J, & Ledgerwood D (2022). Subtypes of patients with opioid use disorder in methadone maintenance treatment: A pathways model analysis. International Gambling Studies, 22(2), 300–316. [Google Scholar]

- Litz M, & Leslie D (2017). The impact of mental health comorbidities on adherence to buprenorphine: A claims based analysis. American Journal on Addictions, 26(8), 859–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loree A, Lundahl L, & Ledgerwood D (2014). Impulsivity as a predictor of treatment outcome in substance use disorders: Review and synthesis. Drug and Alcohol Review, 34(2), 119–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahu I, Barrett S, Conrod P, Bartel S, & Stewart S (2021). Different drugs come with different motives: Examining motives for substance use among people who engage in polysubstance use undergoing methadone maintenance therapy (MMT). Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 229, 109133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt G (1996). Taxonomy of high-risk situations for alcohol relapse: Evolution and development of cognitive-behavioral model. Addiction, 91(12s1), 37–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick R, Breen C, Kimber J, & Davoli M (2014). Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviws, 2, CD002207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh R, Murray H, Hearon B, Pratt E, Pollack M, Safren S, & Otto M (2013). Predictors of dropout from psychosocial treatment in opioid-dependent outpatients. American Journal on Addictions, 22(1), 18–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller F, Barratt E, Dougherty D, Schmitz J, & Swann A (2001). Psychiatric Aspects of Impulsivity. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(11), 1783–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musil C, Warner C, Yobas P, & Jones S (2002). A comparison of imputation techniques for handling missing data. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 24(7), 815–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parlier-Ahmad A, Pugh M, & Martin C (2022). Treatment outcomes among black adults receiving medication for opioid use disorder. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 9(4), 1557–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor S, Copeland A, Kopak A, Hoffmann N, Herschman P, & Polukhina N (2015). Predictors of patient retention in methadone maintenance treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(4), 906–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaie Z, Afshari B, & Balagabri Z (2021). Effects of Dialectical Behavior Therapy on Emotion Regulation, Distress Tolerance, Craving, and Depression in Patients with Opioid Dependence Disorder. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 1–10.33110276 [Google Scholar]

- Rogers A, Zvolensky M, Ditre J, Buckner J, & Asmundson G (2021). Association of opioid misuse with anxiety and depression: A systematic review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 84, 101978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosic T, Naji L, Bawor M, Dennis B, Plater C, Marsh D, Thabane L, & Samaan Z (2017). The impact of comorbid psychiatric disorders on methadone maintenance treatment in opioid use disorder: A prospective cohort study. Neuropsychiatric Disease Adn Treatment, 13, 1399–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepis T, deNadai A, Ford J, & McCabe S (2020). Prescription opioid misuse motive latent classes: Outcomes from a nationally representative US sample. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Science, 29, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinella M (2007). Normative data and a short form of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. International Journal of Neuroscience, 117(3), 359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter R, Kirisci L, Mezzich A, Cornelius J, Pajer K, Vanyukov M, Gardner W, Blackson T, & Clark D (2003). Neurobehavioral Disinhibition in Childhood Predicts Early Age at Onset of Substance Use Disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(6), 1078–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timko C, Schultz N, Cucciare M, Vittorio L, & Garrison-Dihen C (2016). Retention in medication-assisted treatment for opiate dependence: A systematic review. Journal of addictive diseases. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 35(1), 22–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeman S, Larochelle M, Ameli O, Chaisson C, McPeeters J, Crown W, Azocar F, & Sanghavi D (2020). Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Nework Open, 3(2), e1920622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]