Abstract

An 82-year-old woman with parkinsonism and Lewy body dementia was re-admitted to our hospital due to convulsions and the recurrence of cerebral infarction. Parasternal transthoracic echocardiography showed normal left ventricular wall thickness and wall motion. To treat marked bradycardia and hypotension, she underwent temporary pacing. However, she lost her consciousness, when her blood pressure could not be measured. Simultaneous electrocardiogram and blood pressure monitoring showed that systolic blood pressure decreased by almost 30 mmHg from sinus rhythm to junctional rhythm. In the present case of acute cerebral infarction, severe hypotension occurred during junctional rhythm possibly contributed by parkinsonism and Lewy body dementia.

Learning objective

As patients with junctional rhythm usually have no or mild symptoms, there are no specific guidelines for its evaluation and treatment. However, severe symptoms such as hypotension, cerebral infarction, loss of consciousness, or breathlessness may occur in some cases. Holter electrocardiogram with 24-hour noninvasive blood pressure monitoring may be helpful in such severe cases.

Keywords: Junctional rhythm, Severe hypotension, Normal left ventricular function, Parkinsonism and Lewy body dementia

Introduction

Junctional rhythm is a cardiac rhythm arising from the atrioventricular junction as an automatic tachycardia or an escape mechanism during periods of significant bradycardia with rates slower than the intrinsic junctional pacemaker [1]. As most patients with junctional rhythm are asymptomatic, there are no specific guidelines for its evaluation and treatment. We present a case of cerebral infarction and parkinsonism where the patient suffered severe hypotension during junctional rhythm.

Case report

An 82-year-old woman was referred to our hospital due to dysphasia. She had undergone surgery for a lumbar compression fracture and subarachnoid hemorrhage, and had been diagnosed as having parkinsonism and Lewy body dementia. Her extremities were rigid and moved only a little. Her speech was hardly audible because of dysarthria. On physical examination, her consciousness level was E3, V2, and M4, according to the Glasgow Coma Scale. Her blood pressure (BP) was 197/95 mmHg and her pulse rate was 76 beats per minute (bpm). The heart and respiratory sounds were normal on auscultation and there was no pitting edema. Neurological examination demonstrated bilateral Babinski reflex. Results of blood sampling showed anemia (hemoglobin level of 10.4 g/dL), hypoalbuminemia (albumin level of 2.7 g/dL), liver injury (aspartate aminotransferase level of 58 U/L and alanine aminotransferase level of 87 U/L), renal injury (blood urea nitrogen level of 32.7 mg/dL and serum creatinine level of 1.4 mg/dL), and high plasma brain natriuretic peptide level of 608.9 pg/mL. A 12‑lead electrocardiogram (ECG) showed left-axis deviation and ST segment depression in leads V4 and V5 (Fig. 1a). A chest radiograph showed a cardiothoracic ratio of 55 %. Parasternal transthoracic echocardiography showed normal left ventricular (LV) wall thickness. The LV dimension at end-diastole and at end-systole was 36 mm and 22 mm, respectively, and the LV ejection fraction (EF) by Teichholz method was 70 % (Fig. 2). Left atrial dimension was 29 mm. Since a clear two-dimensional image of the apical view was not obtained, LVEF by Simpson's method and left atrial volume were not calculated. Pulsed-wave Doppler echocardiography of the mitral inflow showed an E-wave velocity of 75 cm/s, an A-wave velocity of 105 cm/s, and an E-wave deceleration time of 265 ms. Tissue Doppler echocardiography at the medial mitral annulus showed an e’ wave velocity of 3.2 cm/s and an E/e′ of 24, suggesting LV diastolic dysfunction. Transesophageal echocardiography was not performed due to her families' denial. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed cerebral infarction at the right inner capsule, thalamus, and anterior white matter.

Fig. 1.

A 12‑lead electrocardiogram (ECG) on her second admission showing left-axis deviation and ST segment depression in leads V4 and V5 (a). A 12‑lead ECG on the second day showing bradycardia due to junctional rhythm (b).

Fig. 2.

A parasternal long-axis view showing normal left ventricular (LV) wall thickness. LV dimension at end-diastole and at end-systole was 36 mm and 22 mm, respectively, and LV ejection fraction by Teichholz method was 70 % (a, b). A parasternal short-axis view also showing normal LV wall motion (c, d).

The patient was diagnosed with lacunar infarct and treated with 100 mg of aspirin. As her dysphasia remained, she was transferred to another hospital with nasogastric tube for rehabilitation and with daily administration of 100 mg of droxidopa, 25 mg of zonisamide, 25 mg of opicapone, 50 mg of amantadine, levodopa, and 9 mg of rivastigmine.

However, she collapsed from seizure twice and was re-admitted to our hospital 6 days later. On admission, her blood BP was 143/81 mmHg and her pulse rate was 55 bpm. Auscultation of the lung field was normal. There were no significant changes in her blood tests. MRI of her brain showed newly developed multiple cerebral infarcts.

On the second day, marked bradycardia (30–40 bpm) due to junctional rhythm (Fig. 1b) occurred with hypotension (BP < 90 mmHg). Even after the administration of atropine and dopamine, bradycardia persisted. A temporary pacemaker was inserted through the right femoral vein. After ventricular pacing was initiated, she became unconscious and stopped breathing. Noninvasive BP could not be measured, and cardiac massage and artificial respiration were initiated. Then her BP measured 80 mmHg and she was taken to the intensive care unit.

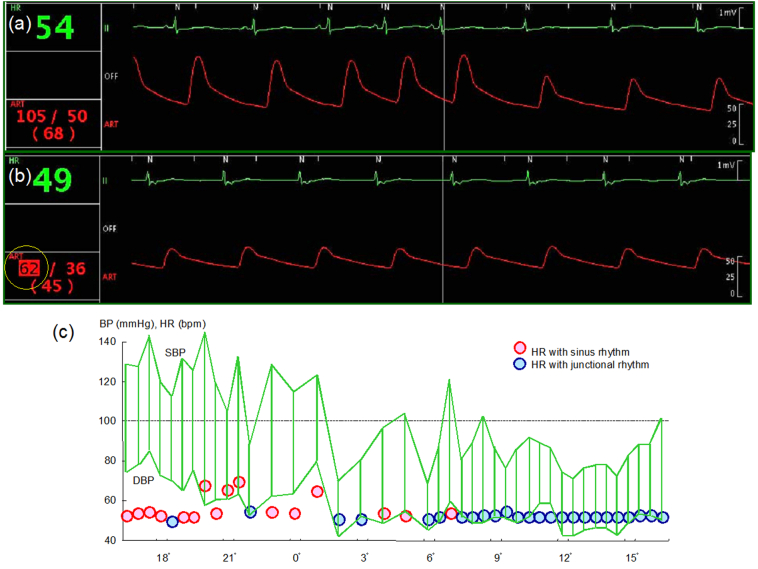

Simultaneous ECG and invasive blood pressure monitoring showed that systolic BP decreased from 111 mmHg to 83 mmHg when sinus rhythm became junctional rhythm (Fig. 3a). On another occasion, systolic BP dropped as low as 62 mmHg (Fig. 3b). Holter ECG with 24-hour BP monitoring showed that BP dropped markedly during junctional rhythm (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Simultaneous electrocardiogram (ECG) and invasive blood pressure (BP) monitoring showing systolic BP decreased from 111 mmHg to 83 mmHg when sinus rhythm became junctional rhythm (a). On another occasion, systolic BP (SBP) dropped as low as 62 mmHg (b). Holter ECG with 24-hour BP monitoring showing BP dropped markedly during junctional rhythm (c).

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate.

Several days later, her cardiac rhythm became sinus rhythm and her BP returned to normal level. Although critical bradycardia might recur in the near future, her family did not consent to pacemaker implantation. She was transferred to another hospital for rehabilitation.

Discussion

Junctional rhythm originates when the electrical activity of the sinoatrial node is blocked or is less than the automaticity of the AV node/His Purkinje. Junctional rhythm can be observed in some conditions and/or with some drugs. In the present case, parkinsonism [2], cerebral infarction [3], and rivastigmine [4] might have contributed to sinus bradycardia and junctional escape rhythm.

Although junctional rhythm is usually asymptomatic, there have been some reports of it being related to significant hypotension. Jeon et al. [5] reported a case of severe hypotension with accelerated junctional rhythm after infiltration of lidocaine containing epinephrine in dental surgery under general anesthesia. They put forward that the combination of these two drugs might have contributed to accelerate junctional rhythm and hypotension. Furthermore, Sardana et al. [6] observed severe hypotension during accelerated junctional rhythm in a case of acute myocardial infarction with severe LV dysfunction. They stressed the importance of preserving LA contraction and atrioventricular synchrony in patients with acute LV dysfunction.

In the present case, the patient lost consciousness and stopped breathing after successful temporary pacing, when noninvasive BP could not be measured because of severe hypotension. Simultaneous ECG and invasive BP monitoring revealed that systolic BP decreased by almost 30 mmHg during junctional rhythm and systolic BP dropped to as low as 62 mmHg. Holter ECG with 24-hour BP monitoring also showed marked hypotension during junctional rhythm.

In the present case, loss of atrial kick might have significantly affected hemodynamics. The patient had suffered from parkinsonism and Lewy body dementia for years, and these diseases are known to cause neurogenic orthostatic hypotension [7]. Neurogenic orthostatic hypotension is a failure of the autonomic nervous system to regulate BP in response to postural change, due to an inadequate release of norepinephrine. It is possible that mildly decreased cardiac output due to disappearance of atrial kick might have caused hypotension without regulation of BP in this case.

On her 2nd admission, an MRI of the brain showed newly developed multiple cerebral infarction. It is possible that paroxysmal atrial fibrillation might have occurred and caused cardiogenic embolism before 2nd admission.

Conclusions

In the present case of acute cerebral infarction, severe hypotension occurred during junctional rhythm possibly contributed by parkinsonism and Lewy body dementia.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ms. Kako Fujno and Yukina Fujii for taking clear echocardiographic images.

References

- 1.Strickberger A. Junctional rhythms and junctional tachycardia. Cardiac electrophysiology 4th ed. 2004:57. doi: 10.1016/B0-7216-0323-8/50060-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olshansky B., Feigofsky S., Cannom D.S. Is it bradycardia or something else causing symptoms? HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2018;4:601–603. doi: 10.1016/j.hrcr.2018.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ritter M.A., Rohde A., Heuschmann P.U., Dziewas R., Stypmann J., Nabavi D.G., Ringelstein B.E. Heart rate monitoring on the stroke unit. What does heart beat tell about prognosis? An observational study. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-11-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soysal P., Isik A.T. Asymptomatic bradycardia due to rivastigmine in an elderly adult with lewy body dementia. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2015;63:2648–2650. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeon Y., Shim J., Kim H. Junctional rhythm with severe hypotension following infiltration of lidocaine containing epinephrine during dental surgery. J. Dent. Anesth Pain. Med. 2020;20:89–93. doi: 10.17245/jdapm.2020.20.2.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sardana M., Shaikh A., Smith C. The atrial kick: atrioventricular dyssynchrony causing paroxysms of hypotension in setting of acute left ventricular dysfunction. J. Am. Col.l Cardiol. 2018;71:A2357. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allan L.M. Diagnosis and management of autonomic dysfunction in dementia syndromes. Curr. Treat. Options. Neurol. 2019;21:38. doi: 10.1007/s11940-019-0581-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]