Abstract

The transition to virtual learning during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic marks a paradigm shift in graduate medical education (GME). From June to September 2021, we conducted a dual-center, multispecialty survey of residents, fellows, and faculty members to determine overall perceptions about virtual learning and assess its benefits, drawbacks, and future role in GME. We discovered a mainly positive view of virtual education among trainees (138/207, 0.67, 95% CI 0.59-0.73) and faculty (180/278, 0.65, 0.59-0.70). Large group sessions, such as didactic lectures, grand rounds, and national conferences, were ranked best-suited for the virtual environment, whereas small groups and procedural training were the lowest ranked. Major benefits and drawbacks to virtual learning was identified. A hybrid approach, combining in-person and virtual sessions, was the preferred format among trainees (167/207, 0.81, 0.75-0.86) and faculty (229/278, 0.82, 0.77-0.87). Virtual learning offers a valuable educational experience that should be retained in postpandemic GME curriculums.

Introduction

Graduate medical education (GME) has seen major changes during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Residents, fellows, and faculty have navigated the switch to online learning at a time of unparalleled clinical demands1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and disruptions,5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 yet trainees must still meet milestones to become independent physicians.21

The widespread move toward virtual learning has reshaped the GME landscape. Video conferencing tools (eg, Zoom, Microsoft Teams) are now commonplace in traditional didactic activities such as morning reports, grand rounds, journal clubs, and board review sessions.22, 23, 24 Similar to modern undergraduate medical curriculums, lectures can now be recorded and reviewed asynchronously.3 , 25 , 26 The use of video libraries, podcasts, and multi-institutional platforms has also increased,10 , 13 , 22 , 27, 28, 29 and programs are actively developing their own virtual curriculums.6 , 12 , 23 , 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34

Many survey-based studies have assessed the pandemic's effect on trainees in various medical and surgical specialties.4 , 8 , 11 , 14 , 16 , 18, 19, 20 , 24 , 35 , 36 These primarily focused on stressors, burnout, and clinical disruptions, and few investigated the relative effectiveness, best use, or future role of virtual learning in GME.37 This survey aimed to gather overall perceptions about virtual education, understand the best use of this technology, and assess its benefits, drawbacks, and future role in GME. This is the first study of our knowledge to present such information from both trainees and faculty from multiple specialties across more than 1 institution.

Methods

Setting and Participants

From June to September 2021, we conducted a dual-center, multispecialty survey of residents, fellows, and faculty at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics (UIHC) and Case Western Reserve University-MetroHealth Medical Center (MHMC). The target population for this study included trainees and faculty involved in GME. At UIHC, we emailed surveys to all 808 house staff (582 residents and 226 fellows) and all faculty members (approximately 1500) in the hospital-wide electronic mailing list. At MHMC, we emailed surveys to 413 residents and fellows only, no faculty were recruited. Participants worked in a wide variety of specialties and departments in the healthcare setting and were representative of the target population (Supplemental Fig 1A-B).

Interventions

We developed homegrown surveys using Qualtrics XM software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Our surveys were validated by the UIHC GME leadership and were pretested by the authors and 2 UIHC cardiology fellows. There were 2 separate surveys: 1 for residents/fellows and another for faculty members, with only minor wording differences between them (Supplemental Figs 2 and 3).

We provided a link to the online survey in an email summarizing the study. Participation was voluntary. At UIHC, we distributed surveys to residents and fellows through the GME office and distributed faculty surveys using an institution-wide electronic mailing list. We released both surveys on June 7, 2021, and sent reminder emails 1 week, 3 weeks, and 4 weeks later. We closed these surveys on July 11, 2021.

At MHMC, we emailed surveys to residents and fellows in a similar fashion using their GME office. We released surveys on August 19, 2021, and sent reminder emails 1 week later. We closed these surveys on October 10, 2021.

Survey responses were collected anonymously using the online Qualtrics platform, personal information could not be traced back to the individual participants.

Outcomes Measured

We asked participants demographic questions, their overall opinions about virtual education and its impact on education, how often they'd prefer to use virtual education if they preferred in-person or virtual education, and which educational activities are best-suited for the virtual environment. We also asked about the perceived benefits and drawbacks of virtual education, and how virtual learning should be used in the future.

The resident/fellow survey included 21 questions, with 4 Likert scale, 2 ranking, 10 multiple choice, and 5 open-ended questions (Supplemental Fig 2). The faculty survey included 20 questions, with 4 Likert scale, 2 ranking, 9 multiple choice, and 5 open-ended questions (Supplemental Fig 3). The question asking about potential drawbacks to virtual education was added to the survey on June 18, 2021. The question asking about the relative effectiveness of virtual education compared to in-person was added on June 15, 2021. We added both questions after receiving respondent feedback that they should be included.

Analysis of the Outcomes

We performed statistical analysis with Stata 17 for Windows (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). We included surveys that were completed beyond demographic information. We tabulated survey question responses using frequency and percent. We used the Wilcoxon rank-sum nonparametric test to compare between trainees, faculty, and resident/fellow training year.

We verified response data by manually cross-checking within the Qualtrics platform. We collected information on the state of residence to divide responses from UIHC and MHMC. Our data analysis occurred from March to May 2022.

Our study was approved as exempt by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board.

Results

Of the 1221 residents and fellows at UIHC and MHMC, 246 attempted the survey, but 207 had completed the survey beyond demographic information and were included in the statistical analysis (response rate = 17%). Of the approximately 1500 faculty at UIHC, 538 attempted the survey and 278 completed the survey beyond demographic information and were included in the statistical analysis (response rate = 19%).

Demographics: Residents and Fellows

Of the 207 residents and fellows who completed the study, 105 (51%) identified as male and 99 (48%) identified as female. The majority of respondents (167/207, 81%) were aged 25-34, 33 (16%) were 35-44, and 4 (2%) were over age 45. There were 38 (18%) R (resident training year)-1 residents, 82 (40%) were R2 or R3, 41 (20%) were R4 and above. Among the 43 fellows who participated, 14 (7%) were F1, 11 (5%) were F2, and 18 (9%) were F3 or higher. Among all house staff respondents, 69% were from UIHC and 25% were from MHMC. The most frequently reported specialties were internal medicine (37/207, 18%) followed by cardiology (26/207, 13%), pediatrics (14/207, 7%), psychiatry (13/207, 6%), and general surgery (10/207, 5%), though a wide range of specialties was reported (Supplemental Fig 1A)

Demographics: Faculty

Of the 278 faculty at UIHC who completed the study, 119 (43%) identified as male, 142 (51%) as female, and 3 (1%) as nonbinary/third gender. Fourteen (5%) of the respondents were aged 18-24, 52 (19%) were aged 25-34, 75 (27%) were 35-44, 61 (22%) were 45-54, 38 (14%) were 55-64, 25 (9%) were 65-74, and 4 (1%) were 75 and older. Faculty worked in an array of medical specialties and departments (Supplemental Fig 1B). The most frequently reported medical specialties were internal medicine and its subspecialties (81/278, 29%) followed by pediatric subspecialties (19/278, 7%), and surgery (17/278, 6%). Complete demographic information for residents, fellows, and faculty are outlined in Table 1 .

TABLE 1.

Virtual education survey demographics

| Characteristic | Residents/fellows |

Faculty |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 105 | 50.7 | 119 | 42.8 |

| Female | 99 | 47.8 | 142 | 51.1 |

| Nonbinary/third gender | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1.1 |

| Age | ||||

| 18-24 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 5 |

| 25-34 | 167 | 80.7 | 52 | 18.7 |

| 35-44 | 33 | 15.9 | 75 | 27.0 |

| 45-54 | 3 | 1.5 | 61 | 21.9 |

| 55-64 | 1 | 0.5 | 38 | 13.7 |

| 65-74 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 9 |

| 75+ | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1.4 |

| Institution | ||||

| UIHC | 143 | 69.1 | 278 | 100 |

| MHMC | 51 | 24.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Did not answer | 13 | 6.28 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 207 | 100 | 278 | 100 |

MHMC, MetroHealth Medical Center; UIHC, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics.

Perceptions of Virtual Education

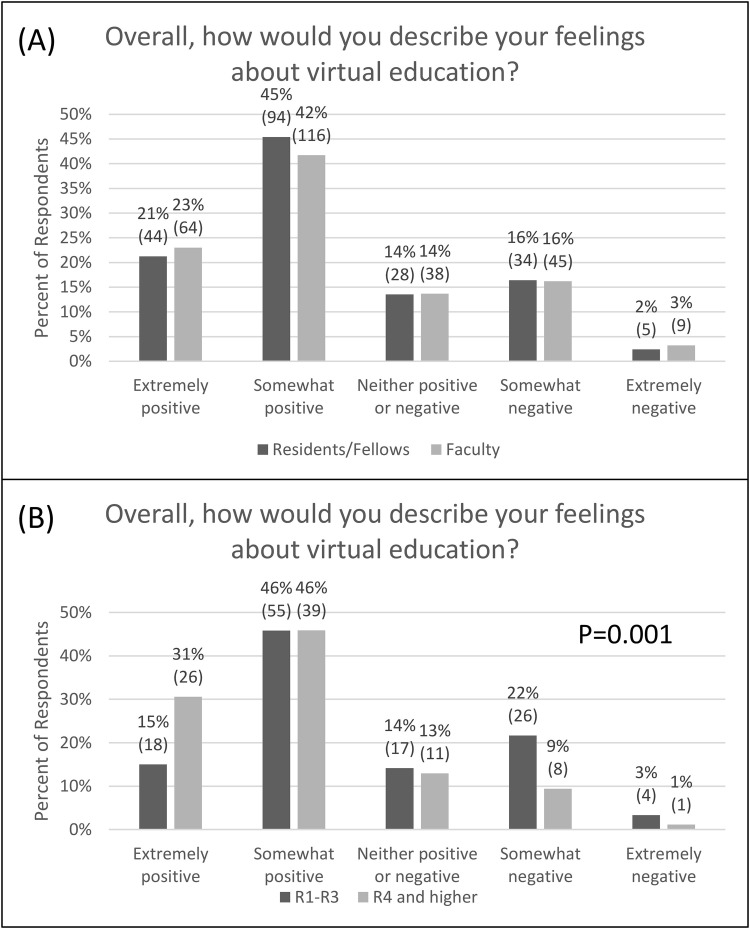

The majority of trainees (138/207, 0.67, 95% CI 0.59-0.73) and faculty (180/278, 0.65, 0.59-0.70) described their feelings as either “positive” or “somewhat positive” in regard to virtual education (Fig 1 A). There was a statistical difference between trainees at level R4 and above compared to R1-R3 (P = 0.001) (Fig 1B). Of the 85 trainees R4 and above, 26 (0.31, 0.21-0.41) described their feelings as “extremely positive” compared to only 18 (0.15, 0.09-0.23) of the 120 R1-R3 residents. R1-R3 residents had more negative views, as 30 (0.25, 0.18-0.33) reported either “somewhat” or “extremely” negative feelings compared to only 9 trainees R4 and above (0.11, 0.05-0.19).

FIG 1.

Overall feelings about virtual education. (A) Resident/fellow and faculty feelings about virtual education. Missing 2 residents/fellows (1%), 6 faculty (2%). (B) Resident/fellow feelings about virtual education based on level of training. There was a statistically significant difference between R1-R3 and R4-higher, P = 0.001. Missing 2 residents/fellows (1%). R, resident training year. (Color version of figure is available online.)

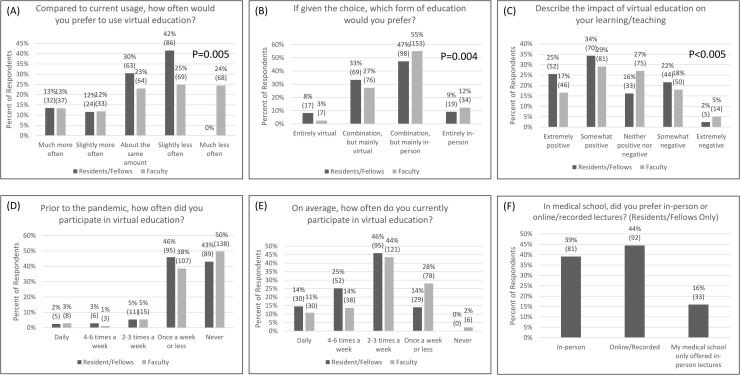

Compared to current usage, most trainees (149/207, 0.72, 0.65-0.78) and faculty (133/278, 0.48, 0.42-0.54) would prefer to use virtual education either the same amount or less often. An additional 68 faculty (0.24, 0.20-0.30) reported they would like to use it much less often (Fig 2 A) compared to zero trainees. Trainees and faculty were statistically distinct in their preferred use of virtual education (P = 0.005).

FIG 2.

Preferences, perceptions, and experiences with virtual education. (A) How often should virtual education be used? Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test comparing trainees and faculty, P = 0.005. Missing 2 residents/fellows (1%), 7 faculty (3%). (B) Which is preferred: In-person or virtual education? Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test comparing trainees and faculty, P = 0.004. Missing 4 residents/fellows (2%), 8 faculty (3%). (C) The impact of virtual education on learning/teaching. Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test comparing trainees and faculty, P value < 0.005. Missing 3 residents/fellows (1%), 12 faculty (4%). (D) Prior to the pandemic, how often was virtual education used? Missing 1 resident/fellow (1%), 7 faculty (3%). (E) How often is virtual education currently being used? Missing 1 resident/fellow (1%), 5 faculty (2%). Residents/fellows prepandemic (D) vs now (E); Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test, p<0.005. Faculty prepandemic (D) vs now (E); Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test, P < 0.005. (F) Resident/fellow preferences in medical school: in-person vs online/recorded lecture. Missing 1 resident/fellow (1, 1%). (Color version of figure is available online.)

If given the choice, most trainees (167/207, 0.81, 0.75-0.86) and faculty (229/278, 0.82, 0.77-0.87) would prefer a combination of virtual and in-person, with a higher preference for “mainly in-person” (trainees 98/207, 0.47, 0.40-0.54; faculty 153/278, 0.55, 0.49-0.61) as opposed to “mainly virtual” (trainees 69/207, 0.33, 0.27-0.40; faculty 76/278, 0.27, 0.22-0.33) (Fig 2B). Only 7 faculty (0.03, 0.01-0.05) preferred “entirely virtual” compared to 17 trainees (0.08, 0.05-0.13). Thirty-four faculty (0.12, 0.09-0.17) would prefer “entirely in-person” compared to 19 trainees (0.09, 0.06-0.14). Trainees and faculty were statistically distinct in their preferred form of education (P = 0.0043).

When we asked participants to describe the impact of virtual education on their learning/teaching, there were significant differences between faculty and trainees (P < 0.005). More residents and fellows (122/207, 0.59, 0.52-0.66) described the impact as “extremely” or “somewhat” positive compared to faculty (127/278, 0.46, 0.40-0.51). Thirty-three trainees (0.16, 0.11-0.21) and 75 faculty (0.27, 0.21-0.32) reported “nether positive nor negative.” Forty-four trainees (0.22, 0.16-0.27) and 50 faculty (0.18, 0.14-0.23) reported “somewhat negative” and only 5 trainees (0.02, 0.01-0.06) and 14 faculty (0.05, 0.03-0.08) reported “extremely negative” (Fig 2C).

The use of virtual education during the pandemic significantly increased compared to prepandemic for both trainees and faculty (P < 0.005). The majority of trainees (177/207, 0.86, 0.80-0.90) and faculty (189/278, 0.68, 0.62-0.73) were currently using virtual education at least 2-3 times a week. Before the pandemic, most used virtual education once a week or less (Trainees 184/207, 0.89, 0.84-0.93; Faculty 247/278, 0.89, 0.85-0.92) (Figs 2D and 2E).

We also asked residents and fellows if they preferred in-person or online/recorded lectures in medical school. A slight majority (92/207, 0.44, 0.38-0.51) preferred “online/recorded” lectures compared to “in-person” (81/207, 0.39, 0.32-0.46). Thirty-three (0.16, 0.11-0.21) said their medical school only offered in-person lectures (Fig 2F).

Which Educational Activities are Best for Virtual Learning?

We asked respondents about their experiences with virtual education in various learning environments. For all respondents, virtual education was most commonly used for “PowerPoint lectures.” We then asked participants to rank educational activities from best to worst in terms of their suitability for the virtual learning environment. For both trainees and faculty, the highest-ranked educational activity was PowerPoint lectures, followed by board review, procedure simulation, grand rounds, conferences/workshops/seminars, research presentations, small groups, and other (Supplemental Table 1).

Benefits, Drawbacks, and Future Directions

We asked open-ended questions about the benefits and drawbacks of virtual education. We qualitatively reviewed their responses. Major themes can be found in Table 2 . Both trainees and faculty appreciated the accessibility and flexibility of virtual education, including the ability to watch lectures anytime, anywhere, and attend despite busy clinical schedules. They reported that virtual education allowed more time for family and personal hobbies thereby improving work-life balance. The drawbacks of virtual education included the impersonal and isolated feeling from reduced social interactions before, during, and after sessions. Faculty frequently reported audience distraction and had trouble “connecting” with them. Technical difficulties and excess screen time were also reported downsides. Some trainees thought they did not learn as well on virtual formats.

TABLE 2.

Benefits and drawbacks of virtual education

| Benefits | Drawbacks |

|---|---|

| Accessibility/flexibility/convenience | Impersonal/isolating |

| Allows for multitasking | Less interactive/reduced participation |

| Saves time/less commuting | Audience loses attention |

| More family/personal time | More distractions |

| Better work-life balance | Loss of social connectedness/camaraderie |

| Cost-savings (eg, childcare, gas) | Less networking opportunities |

| Increased attendance | Less hands-on/procedural training |

| More visiting lecturers | Reduced learning and retention |

| Recording/playback capabilities | More technical difficulties |

| Chat features | Too much screen time |

We also asked which virtual education activities should be continued after the pandemic is over (Table 3 ). Many respondents wanted to continue large group talks virtually, such as grand rounds and morbidity and mortality conferences. They also saw the benefit in continuing regional and national conferences virtually, making attendance easier, faster, and cheaper. Most wanted to continue traditional didactics, morning reports, and board review sessions in virtual formats, but a hybrid approach was often encouraged (ie, return to in-person with a virtual option for those off campus or unable to attend). Several faculties said that virtually-conducted administrative meetings would be just as effective and more time-efficient. Small group sessions were deemed less conducive to virtual formats as they rely on frequent participation which is limited by screen-based communication.

TABLE 3.

Which virtual activities should be continued after the covid-19 pandemic?

| Virtual GME activities to continue postpandemic* |

|---|

| Grand rounds |

| Morbidity & mortality conference |

| Invited guest speakers |

| Inter-institutional presentations |

| National conferences |

| Research presentations |

| Didactic lectures |

| Morning report |

| Board review |

| Administrative meetings |

| Hospital protocol training |

| Small group sessions† |

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; GME, graduate medical education.

Activities are listed in no particular order.

A few respondents suggested that small group sessions should only be considered in very specific instances.

Discussion

The use of virtual learning in GME has rapidly become the “new normal” during the COVID-19 pandemic, but its optimal use is yet to be determined. This survey-based study provides evidence in favor of conducting large group sessions virtually, such as didactic lectures and grand rounds, as well as conferences, workshops, and seminars. There are many benefits and drawbacks to virtual learning, and a hybrid approach, combining in-person and virtual elements, may be the optimal solution.

Although we found a generally positive view of virtual education among trainees and faculty, most would prefer to use it the same amount or less often, suggesting the need to limit video conferencing methods and avoid so-called “Zoom fatigue.38” Faculty held a more negative view of these technologies, perhaps explained by generational differences in adapting to newer technologies.1 Advanced trainees were more positive about virtual learning than earlier trainees, possibly explained by their established social connections and greater reliance on clinical, rather than didactic, learning. They are also older on average, more likely to have families, and may benefit more from efficient virtual sessions.

Virtual learning has been used in many traditional educational activities,6 , 22, 23, 24 but which is best for the virtual environment? We found that PowerPoint lectures were the highest-ranked activity for the virtual environment, followed by board reviews, grand rounds, and conferences (Supplemental Table 1). Thus, virtual modalities seem best for activities where audience participation is not required, as time delays inhibit interactive discussions.38 Unsurprisingly, small group work was the lowest-ranked activity given its reliance on frequent interaction.

Early in the pandemic, many national and regional conferences were canceled and moved to the virtual environment where live and on-demand presentations became more widely accessible.5 , 23 Studies have shown increased attendance during this period, citing time- and cost-savings as major influences.27 Our survey results support these benefits, especially among faculty.

This study affirmed previously described benefits of virtual learning in GME, such as accessibility, flexibility, recording capabilities, and time-savings36; yet drawbacks remain, including the impersonal nature of online formats, increased distractions, technical difficulties, and even reduced networking opportunities (Table 2). The negative impact of the pandemic on psychosocial well-being among physicians-in-training has been recognized.3 , 6 , 8 , 18 , 20 , 24 , 35 , 36 This may contribute to negative perceptions of virtual learning. Similarly, the cancellation and postponement of procedures remain a concern for surgical and procedural trainees,4 , 5 , 7 , 9 , 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 , 35 and it may be difficult for virtual learning to bridge this training gap.

This study has several limitations. We did not assess psychosocial stress or well-being among participants, a potential confounder gave the COVID-19 pandemic's emotional impact. A disproportionate number of respondents were from UIHC, no faculty were recruited at MHMC, and internal medicine and its subspecialties were heavily represented with less input from surgical/procedural specialties. Surveys were also done at 2 distinct timepoints in a pandemic that was constantly evolving. Lastly, we must consider response bias since this is survey data.

As the ever-evolving COVID-19 pandemic unfolds and the need for social distancing is reduced, GME programs across the world must consider if, and how, virtual learning should be retained in their curriculums. Future research should compare in-person, virtual, and hybrid curriculums and their outcomes on clinical and educational performance metrics among trainees across all medical and surgical disciplines. Repeat survey-based studies at later stages in the COVID-19 pandemic would be useful. Understanding the utility of virtual learning methods will determine its future role in GME.

Conclusion

The transition to virtual education during the COVID-19 pandemic has challenged us to rethink how we learn and teach amid social distancing guidelines. Our dual-center, the survey-based study offers an overall positive view of virtual learning. Virtual learning appears best for large group sessions and conferences but is less suitable for small groups and procedural training. A hybrid approach, combining in-person and virtual formats, may help balance the benefits and drawbacks. These results will guide GME curricular development in a postpandemic world.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank Hillary Chappo, MHA and Gerald Wickham, EdD, MA, (UIHC GME Office), Sasha Alexander (UIHC Office of the Dean), and the MHMC GME Office for their assistance with survey distribution.

Authors’ Contribution

Aron Evans: Methodology, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, project administration. Mehul Adhaduk: formal analysis, writing—review and editing. Ahmad Jabri: data curation, investigation, writing—review and editing. Mahi Ashwath: conceptualization, supervision, writing—review and editing, project administration.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2023.101641.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.McCarthy C, Carayannopoulos K, Walton JM. COVID-19 and changes to postgraduate medical education in Canada. CMAJ. 2020;192(35):E1018–E1020. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sia CH, Tan BY, Ooi SBS. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on postgraduate medical education in a Singaporean academic medical institution. Korean J Med Educ. 2020;32(2):97–100. doi: 10.3946/kjme.2020.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaul V, Gallo de Moraes A, Khateeb D, et al. Medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Chest. 2021;159(5):1949–1960. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El Tahan MR, Wilkinson K, Huber J, et al. Challenges in the cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia fellowship program since the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: an electronic survey on potential solutions. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2022;36(1):76–83. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2021.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrario L, Maffioli A, Bondurri AA, et al. COVID-19 and surgical training in Italy: residents and young consultants perspectives from the battlefield. Am J Surg. 2020;220(4):850–852. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dedeilia A, Sotiropoulos MG, Hanrahan JG, et al. Medical and surgical education challenges and innovations in the COVID-19 era: a systematic review. In Vivo. 2020;34(3 Suppl):1603–1611. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yadav A. Cardiology training in times of COVID-19: beyond the present. Indian Heart J. 2020;72(4):321–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2020.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enujioke SC, McBrayer K, Soe KC, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on post graduate medical education and training. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):580. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-03019-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu KM, Smith M, Steyn E, et al. Changes in surgical practice in 85 South African hospitals during COVID-19 hard lockdown. S Afr Med J. 2020;110(9):916–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newsome HA, Davies OMT, Doerfer KW. Coronavirus disease 2019-an impetus for resident education reform? JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146(9):785–786. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aziz H, James T, Remulla D, et al. Effect of COVID-19 on surgical training across the United States: a National Survey of General Surgery Residents. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(2):431–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chick RC, Clifton GT, Peace KM, et al. Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(4):729–732. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakshi SK, Ho AC, Chodosh J, et al. Training in the year of the eye: the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on ophthalmic education. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104(9):1181–1183. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-316991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campi R, Amparore D, Checcucci E, et al. Exploring the residents' perspective on smart learning modalities and contents for virtual urology education: lesson learned during the COVID-19 pandemic. Actas Urol Esp (Engl Ed) 2021;45(1):39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.acuro.2020.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen SY, Lo HY, Hung SK. What is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on residency training: a systematic review and analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):618. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-03041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrara M, Romano V, Steel DH, et al. Reshaping ophthalmology training after COVID-19 pandemic. Eye (Lond) 2020;34(11):2089–2097. doi: 10.1038/s41433-020-1061-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imielski B. The detrimental effect of COVID-19 on subspecialty medical education. Surgery. 2020;168(2):218–219. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khusid JA, Weinstein CS, Becerra AZ, et al. Well-being and education of urology residents during the COVID-19 pandemic: results of an American National Survey. Int J Clin Pract. 2020;74(9):e13559. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pelargos PE, Chakraborty A, Zhao YD, et al. An evaluation of neurosurgical resident education and sentiment during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a North American Survey. World Neurosurg. 2020;140:e381–e386. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shih G, Deer JD, Lau J, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the education and wellness of U.S. Pediatric anesthesiology fellows. Paediatr Anaesth. 2021;31(3):268–274. doi: 10.1111/pan.14112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Education ACfGM. Guidance statement on competency-based medical education during COVID-19 residency and fellowship disruptions. Updated January 2022. 2022. https://www.acgme.org/newsroom/2020/9/guidance-statement-on-competency-based-medical-education-during-covid-19-residency-and-fellowship-disruptions/.

- 22.Shah S, Diwan S, Kohan L, et al. The technological impact of COVID-19 on the future of education and health care delivery. Pain Physician. 2020;23(4S):S367–S380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gottlieb M, Landry A, Egan DJ, et al. Rethinking residency conferences in the era of COVID-19. AEM Educ Training. 2020;4(3):313–317. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hahn TW. Virtual noon conferences: providing resident education and wellness during the COVID-19 pandemic. PRiMER. 2020;4:17. doi: 10.22454/PRiMER.2020.364166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hammond D, Louca C, Leeves L, et al. Undergraduate medical education and Covid-19: engaged but abstract. Med Educ Online. 2020;25(1) doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1781379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marshall AL, Wolanskyj-Spinner A. COVID-19: challenges and opportunities for educators and generation Z learners. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(6):1135–1137. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Senapati A, Khan N, Chebrolu LB. Impact of social media and virtual learning on cardiology during the COVID-19 pandemic era and beyond. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2020;16(3):e1–e7. doi: 10.14797/mdcj-16-3-e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Almarzooq ZI, Lopes M, Kochar A. Virtual learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: a disruptive technology in graduate medical education. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(20):2635–2638. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roy SF, Cecchini MJ. Implementing a structured digital-based online pathology curriculum for trainees at the time of COVID-19. J Clin Pathol. 2020;73(8):444. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2020-206682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teele SA, Sindelar A, Brown D, et al. Online education in a hurry: delivering pediatric graduate medical education during COVID-19. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2021;60 doi: 10.1016/j.ppedcard.2020.101320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eusuf DV, England EL, Charlesworth M, et al. Maintaining education and professional development for anaesthesia trainees during the COVID-19 pandemic: the Self-isolAting Virtual Education (SAVEd) project. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125(5):e432–e434. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis EE, Taylor LJ, Hermsen JL, et al. Cardiothoracic education in the time of COVID-19: how I teach it. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;110(2):362–363. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alvin MD, George E, Deng F, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on radiology trainees. Radiology. 2020;296(2):246–248. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nadgir R. Teaching remotely: educating radiology trainees at the workstation in the COVID-19 era. Acad Radiol. 2020;27(9):1291–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2020.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chou DW, Staltari G, Mullen M, et al. Otolaryngology resident wellness, training, and education in the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2021;130(8):904–914. doi: 10.1177/0003489420987194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rana T, Hackett C, Quezada T, et al. Medicine and surgery residents' perspectives on the impact of COVID-19 on graduate medical education. Med Educ Online. 2020;25(1) doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1818439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kivlehan E, Chaviano K, Fetsko L, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: early effects on pediatric rehabilitation medicine training. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2020;13(3):289–299. doi: 10.3233/PRM-200765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiederhold BK. Connecting through technology during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: avoiding "Zoom Fatigue". Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2020;23(7):437–438. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2020.29188.bkw. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.