Key Points

Question

Does argatroban improve neurologic function in patients with acute ischemic stroke who received intravenous recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (alteplase)?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 808 patients with acute ischemic stroke, excellent neurologic function at 90 days (modified Rankin Scale score of 0 to 1) in those randomized to receive argatroban plus intravenous alteplase compared with intravenous alteplase alone occurred in 63.8% vs 64.9% of participants, a difference that was not statistically significant.

Meaning

Among patients with acute ischemic stroke who received intravenous alteplase, argatroban was not significantly associated with better neurologic function.

Abstract

Importance

Previous studies suggested a benefit of argatroban plus alteplase (recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator) in patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS). However, robust evidence in trials with large sample sizes is lacking.

Objective

To assess the efficacy of argatroban plus alteplase for AIS.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This multicenter, open-label, blinded end point randomized clinical trial including 808 patients with AIS was conducted at 50 hospitals in China with enrollment from January 18, 2019, through October 30, 2021, and final follow-up on January 24, 2022.

Interventions

Eligible patients were randomly assigned within 4.5 hours of symptom onset to the argatroban plus alteplase group (n = 402), which received intravenous argatroban (100 μg/kg bolus over 3-5 minutes followed by an infusion of 1.0 μg/kg per minute for 48 hours) within 1 hour after alteplase (0.9 mg/kg; maximum dose, 90 mg; 10% administered as 1-minute bolus, remaining infused over 1 hour), or alteplase alone group (n = 415), which received intravenous alteplase alone. Both groups received guideline-based treatments.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary end point was excellent functional outcome, defined as a modified Rankin Scale score (range, 0 [no symptoms] to 6 [death]) of 0 to 1 at 90 days. All end points had blinded assessment and were analyzed on a full analysis set.

Results

Among 817 eligible patients with AIS who were randomized (median [IQR] age, 65 [57-71] years; 238 [29.1%] women; median [IQR] National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score, 9 [7-12]), 760 (93.0%) completed the trial. At 90 days, 210 of 329 participants (63.8%) in the argatroban plus alteplase group vs 238 of 367 (64.9%) in the alteplase alone group had an excellent functional outcome (risk difference, −1.0% [95% CI, −8.1% to 6.1%]; risk ratio, 0.98 [95% CI, 0.88-1.10]; P = .78). The percentages of participants with symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, parenchymal hematoma type 2, and major systemic bleeding were 2.1% (8/383), 2.3% (9/383), and 0.3% (1/383), respectively, in the argatroban plus alteplase group and 1.8% (7/397), 2.5% (10/397), and 0.5% (2/397), respectively, in the alteplase alone group.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients with acute ischemic stroke, treatment with argatroban plus intravenous alteplase compared with alteplase alone did not result in a significantly greater likelihood of excellent functional outcome at 90 days.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03740958

This randomized clinical trial examines the efficacy of argatroban plus altepase for acute ischemic stroke within 4.5 hours from onset.

Introduction

Current guidelines recommend reperfusion therapies, such as intravenous thrombolysis and endovascular thrombectomy, as the most effective strategies for management of acute ischemic stroke (AIS).1 Vessel recanalization was strongly associated with lower mortality and improved functional outcome of reperfusion therapies in patients with AIS.2 However, only 30% of patients achieved complete recanalization through intravenous thrombolysis,3 while approximately 30% of patients with large artery occlusion did not achieve successful reperfusion after endovascular thrombectomy.4 Although endovascular therapy has been shown to be effective in AIS with large artery occlusion,4 its use in clinical practice was limited due to a reliance on device availability and experienced clinicians. In addition, 14% to 34% of the population with initial recanalization underwent reocclusion after alteplase (recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator) thrombolysis and had clinical deterioration and poor outcomes.3,5 Thus, an effective and simple method is needed to improve vessel recanalization, prevent reocclusion, and reduce AIS disability.

Argatroban, a selective thrombin inhibitor, directly inhibits free and clot-associated thrombin as well as thrombin-induced events and has been widely used to treat AIS, particularly in Asian countries such as China and Japan.6,7 Growing evidence from preclinical studies demonstrated the effect of argatroban plus alteplase in ischemic stroke by enhancing and sustaining arterial recanalization.8,9 Translating into clinical practice, early-phase trials have explored the safety and possible efficacy of argatroban plus alteplase in patients receiving intravenous thrombolysis and endovascular treatments.10,11,12 There is a lack of robust evidence for the effect of argatroban plus alteplase in AIS patients because of small sample sizes. In addition, argatroban was found to have neuroprotective potential.13 In this context, a multicenter, open-label, blinded end point randomized trial was designed to explore the efficacy of argatroban plus alteplase for AIS within 4.5 hours from onset.

Methods

Study Design

The Argatroban Plus Recombinant Tissue-Type Plasminogen Activator for AIS (ARAIS) study was a multicenter, open-label, blinded end point randomized trial to assess the efficacy of argatroban plus alteplase in patients with AIS within 4.5 hours from symptom onset. The study protocol is available in Supplement 1 and the statistical analysis plan is available in Supplement 2. The trial was conducted at 50 medical sites (eAppendix 1 in Supplement 3) in China. Details of the study design and rationale have been published elsewhere.14 The trial protocol was approved by the appropriate regulatory and ethical authorities of the ethics committee of the General Hospital of Northern Theatre Command and other participating hospitals. An independent data monitoring committee (eAppendix 2 in Supplement 3) monitored the progress of the trial every 6 months. An independent clinical research organization (Nanjing Service Pharmaceutical Technology Co) monitored the trial for quality control. Signed informed consent was obtained from patients or their legally authorized representatives.

Participants

Eligible patients were adults aged 18 to 80 years with AIS at the time of randomization (baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] score of more than 6; range, 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating greater stroke severity) and were enrolled up to 4.5 hours after the onset of stroke symptoms (the time the patient was last seen well). Whole-head computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging was performed on admission to identify patients with ischemic stroke. Key exclusion criteria were as follows: presence of disability in the community (modified Rankin Scale [mRS] score ≥2; range, 0 [no symptoms] to 6 [death]) before the stroke, history of intracerebral hemorrhage, gastrointestinal or urinary tract bleeding in the last 30 days, and need for concomitant use of anticoagulants other than argatroban. A full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria is available in the study protocol (Supplement 1).

Randomization and Masking

In the trial, eligible patients were randomly assigned to either the argatroban plus alteplase group or the alteplase alone group using a block randomization method with a block size of 4 through a computer-generated random sequence that was centrally administered via a password-protected web-based program (Beijing Zhinan Medical Technology Co). The study team members were blinded to the treatment randomization.

Procedures

In both treatment groups, intravenous alteplase (0.9 mg/kg; maximum dose, 90 mg; 10% administered as a 1-minute bolus, the remaining infused over 1 hour; Boehringer Ingelheim Co) was administered within 4.5 hours after symptom onset. Patients in the argatroban plus alteplase group received a 100-μg/kg intravenous argatroban (Tianjin Institute of Pharmaceutical Research Co) bolus over 3 to 5 minutes within 1 hour of the alteplase bolus, followed by an argatroban infusion of 1.0 μg/kg per minute for 48 hours. Standard treatments based on current guidelines were also received by the patients in both groups.1

Argatroban infusion rates were adjusted to achieve a target activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) of 1.75 × baseline (±10%). A dosing algorithm was developed so that standardized increments or decrements of argatroban infusion rate took place in response to the APTT.15 APTT was monitored at baseline and at 2, 6, 12, 24, and 48 hours after initiation of argatroban; within 2 to 4 hours of any argatroban infusion adjustment; and in the event of major systemic bleeding. Argatroban infusion was terminated immediately if major systemic bleeding or symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage was suspected.

The NIHSS was used to assess neurologic status at baseline, 24 hours, 48 hours, 7 days, and 14 days after randomization. A detailed flowchart of the assessment schedule is provided in the study protocol (Supplement 1). Data on demographic and clinical characteristics were obtained at randomization. Follow-up data were collected at 7 days, 14 days (or at hospital discharge if earlier), and 90 days after randomization. Remote and on-site quality control monitoring and data verification were conducted throughout the study.

Outcomes

The primary end point was excellent functional outcome at 90 days, defined as a score of 0 to 1 on the mRS for the evaluation of neurologic disability, assessed in person or, if an in-person visit was not possible, through a structured interview for telephone assessment by personnel certified in the scoring of the mRS 90 days after randomization (eMethods in Supplement 3).

The secondary end points were favorable functional outcome (mRS score of 0-2) at 90 days; the occurrence of early neurologic improvement compared with baseline at 48 hours, defined as a decrease in NIHSS score of greater than or equal to 216; the occurrence of early neurologic deterioration compared with baseline at 48 hours, defined as an increase in NIHSS score of greater than or equal to 417; change in NIHSS score compared with baseline at 14 days; and the occurrence of stroke18 or other vascular events (transient ischemic attack, myocardial infarction, and vascular death) within 90 days.

Any adverse events that occurred during the study were recorded. The prespecified adverse event outcomes were symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, parenchymal hematoma type 2, and major systemic bleeding that occurred during the study. Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage was defined as any evidence of bleeding on the head computed tomography scan associated with clinically significant neurologic deterioration (≥4-point increase in NIHSS score) in the opinion of the clinical investigator or independent safety monitor.19 Parenchymal hematoma type 2 was defined as confluent bleeding occupying more than 30% of the infarct volume and causing significant mass effect.20 Major systemic bleeding was defined as a drop in the hemoglobin level by at least 2 g/dL or a transfusion of at least 2 U of blood. Follow-up head computed tomography was performed at 24 hours (alteplase alone group) or 48 hours (argatroban plus alteplase group) after randomization or at any time when neurologic deterioration occurred (eFigure 1 in Supplement 3). A central core laboratory for imaging was set to judge intracranial bleeding events and severity.

The baseline and follow-up NIHSS scores were evaluated by the same certified neurologist, who was not blinded to the treatment randomization due to the difficulty of blinding to the open label of argatroban. Final follow-up was performed at 90 days in person or, if an in-person visit was not possible, a structured interview for telephone assessment was performed by a trained and certified staff member in each center who was unaware of the randomized treatment assignment. A training course was held for all the investigators at each center to ensure the validity and reproducibility of the evaluation, and only certified investigators were eligible to evaluate NIHSS or mRS scores. Central adjudication of clinical outcomes and adverse events was also performed by assessors unaware of treatment randomization or clinical details. If there was disagreement between local and central assessors, a consensus was reached by discussion. The local assessor retained control of the final mRS score following any discussion. In addition, there was no disagreement between the central adjudicator and the local assessor.

Sample Size Calculation

Power calculations were based on the estimated treatment effects based on a binary assessment of excellent functional outcome at 90 days. In the Argatroban With Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Acute Stroke (ARTSS-2) study,11 argatroban plus alteplase resulted in a 9% improvement in the primary end point compared with alteplase alone. Therefore, 9% was chosen as the difference used to power this study. Based on the assumption that the percentage of participants with excellent functional outcome was 30% in the argatroban plus alteplase group and 21% in the alteplase alone group (equivalent to a risk ratio [RR] of 1.43), a sample size of 734 (367 per group) was estimated to provide more than 80% power (using a 2-sided α = .05) to detect the 9% greater excellent functional outcome in the argatroban plus alteplase group. Assuming a 10% loss to follow-up, the total sample size was 808 (404 participants per group).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed on the full analysis set, which included all randomized participants with at least 1 postbaseline efficacy evaluation. Generalized linear models (GLMs) were performed for the analyses of the primary and secondary outcomes of favorable functional outcome at 90 days, the occurrence of early neurologic improvement, and early neurologic deterioration. The treatment effects for the above outcomes are presented as RRs and risk differences (RDs) with their 95% CIs. In sensitivity analyses, missing values in the primary outcome were imputed using the last observation carried forward approach, the worst-case scenario approach, the best-case scenario approach, and post hoc multiple imputation. No interim analyses were performed in this study.

A GLM was also used to compare changes in NIHSS score between admission and 14 days, and the geometric mean ratio and 95% CI were calculated between the argatroban plus alteplase and alteplase alone groups. The time-to-event outcomes of stroke or other vascular events were compared using Cox regression models, and the corresponding treatment effects were presented as hazard ratios with 95% CIs. The hazard proportionality assumption was tested by introducing an interaction between time and treatment in the Cox model.

The primary analyses of the primary and secondary outcomes were unadjusted. Covariate-adjusted GLM analyses were also performed for all outcomes, adjusting for 6 prespecified prognostic factors: age, sex, NIHSS score at randomization, time from symptom onset to thrombolysis, premorbid function (mRS score of 0 or 1), and history of stroke or transient ischemic attack. Endovascular therapy and large artery occlusion were planned in the covariate-adjusted analyses but were excluded due to skewed distribution or large percentage of missing values (Supplement 2). The missing values of baseline variables in the covariate-adjusted analyses were imputed using simple imputation methods based on their sample distributions. For example, for a continuous variable, missing values were imputed from random values generated from a normal distribution with mean and SD calculated from the available sample.

A subgroup analysis of the primary outcome was performed using GLM on 8 prespecified subgroups (age [<65 years or ≥65 years], sex [female or male], NIHSS score at randomization [6-9 or >9], endovascular therapy [yes or no], large artery occlusion [yes or no], time from symptom onset to thrombolysis [<3 hours or 3-4.5 hours], premorbid function [mRS score], and history of stroke or transient ischemic attack). Assessment of the homogeneity of the treatment effect by a subgroup variable was conducted using a GLM with the treatment, subgroup variable, and their interaction term as independent variables, and the P value for the interaction term was presented. Detailed statistical analyses are described in the statistical analysis plan (Supplement 2).

In addition, per-protocol analyses for primary and secondary outcomes were performed on patients who received the complete intervention as specified in the protocol. A shift in measures of functioning according to the full range of mRS scores at 90 days was performed in a post hoc ordinal logistic regression via GLM with treatment effect presented as an odds ratio with 95% CI. Analyses of adverse events were based on the safety population, which consisted of all randomized participants who received at least 1 dose of the study drug. A 2-sided P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings for secondary outcome analyses should be interpreted as exploratory. SPSS software, version 23 (IBM), and R software, version 4.1.0 (R Foundation), were used for the statistical analyses.

Results

Trial Population

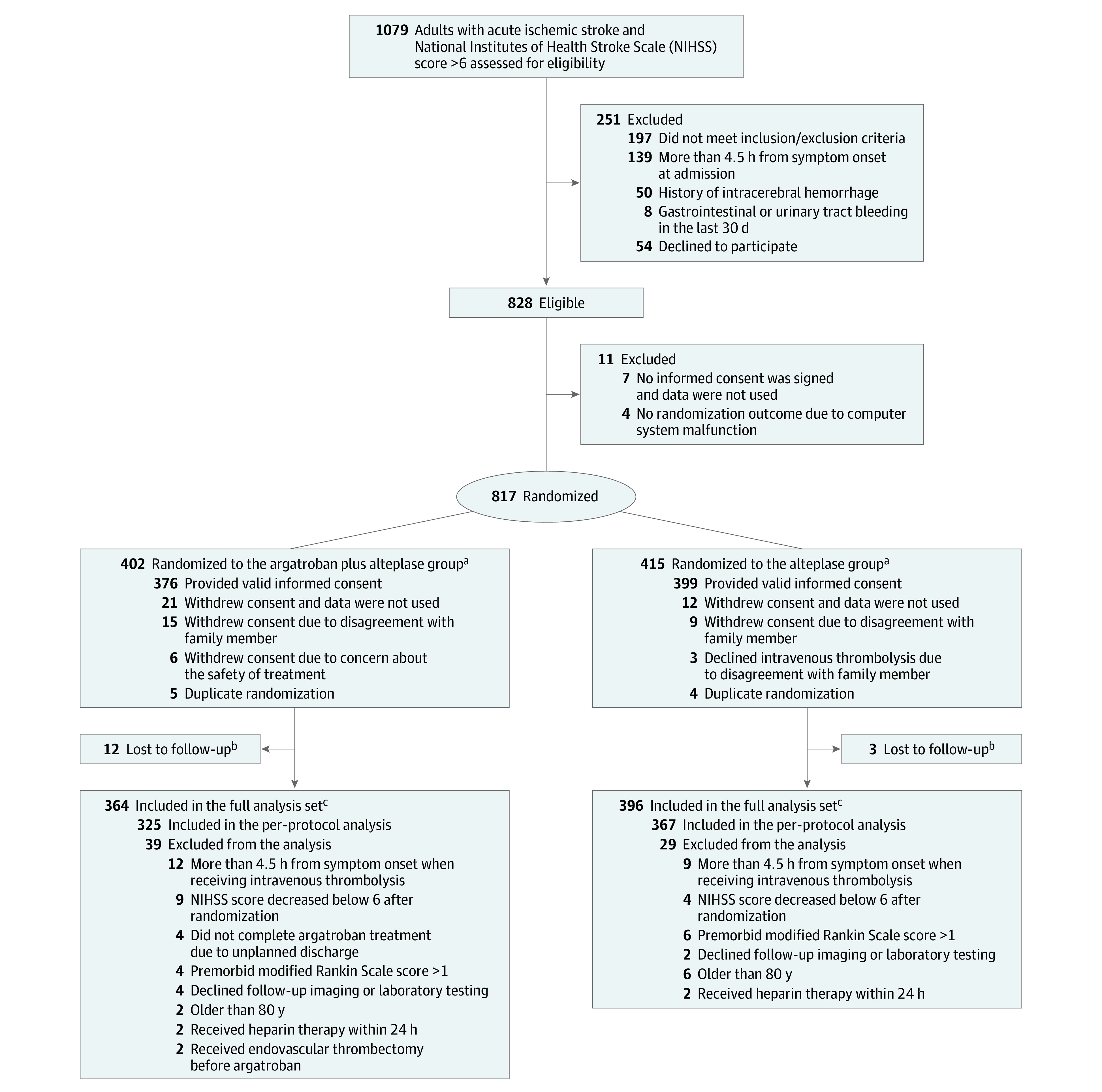

Between January 18, 2019, and October 30, 2021, a total of 828 patients were enrolled and 817 were randomly assigned to the argatroban plus alteplase group (402 patients) or the alteplase alone group (415 patients) after 11 patients were excluded due to randomization errors or lack of informed consent. A total of 57 patients (7.0%) were excluded (33 withdrew consent due to patient decision, 9 duplicate randomizations, and 15 were lost to follow-up). The full analysis set population included 760 patients (364 in the argatroban plus alteplase group and 396 in the alteplase alone group) (Figure 1 and eFigure 2 in Supplement 3). The procedure was completed according to the protocol for 692 patients (325 in the argatroban plus alteplase group and 367 in the alteplase alone group) and the results were included in the per-protocol analysis. The reasons for the incomplete procedures are provided in Figure 1. The trial was completed in January 2022.

Figure 1. Patient Flow in the ARAIS Randomized Clinical Trial.

aA total of 383 patients in the argatroban plus alteplase group and 397 patients in the alteplase group were included in the safety population.

bPatients lost to follow-up due to missing any follow-up assessments after treatment.

cBaseline characteristics in patients missing primary outcome data are shown in eTable 4 in Supplement 3.

The treatment groups were well balanced with respect to baseline patient characteristics in the full analysis set population (Table 1) and per-protocol analysis set population (eTable 1 in Supplement 3). In the argatroban plus alteplase group, 325 of 364 patients (89.3%) underwent the complete procedure of argatroban plus alteplase treatment at a median of 155 minutes from symptom onset to the alteplase treatment. The remaining 39 patients did not receive complete argatroban treatment after alteplase treatment. In the alteplase group, 367 of 396 patients (92.7%) underwent the complete procedure of alteplase treatment at a median of 155 minutes from symptom onset to the alteplase treatment. The remaining 29 patients did not receive complete alteplase treatment.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Population in a Study of the Effect of Argatroban Plus Alteplase vs Alteplase on Neurologic Function After Acute Ischemic Stroke.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full analysis set | Randomization set | |||

| Argatroban plus alteplase (n = 364) | Alteplase alone (n = 396) | Argatroban plus alteplase (n = 402) | Alteplase alone (n = 415) | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 66 (58-72) | 64 (56-71) | 66 (58-72) | 64 (56-71) |

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 249 (68.4) | 289 (73.0) | 271/397 (68.3) | 299/411 (72.7) |

| Women | 115 (31.6) | 107 (27.0) | 126/397 (31.7) | 112/411 (27.3) |

| Currently smokes tobacco | 131 (36.0) | 141 (35.6) | 141/396 (35.6) | 143/411 (34.8) |

| Currently drinks alcohola | 69/354 (19.5) | 69/389 (17.7) | 73/386 (18.9) | 69/404 (17.1) |

| Comorbiditiesb | ||||

| Hypertension | 203 (55.8) | 223 (56.3) | 216/397 (54.4) | 232/411 (56.4) |

| Diabetes | 91 (25.0) | 81 (20.5) | 100/397 (25.2) | 87/410 (21.2) |

| Prior ischemic or hemorrhagic strokec | 74 (20.3) | 68 (17.2) | 82/397 (20.7) | 74/411 (18.0) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 18/346 (5.2) | 21/378 (5.6) | 19/365 (5.2) | 22/388 (5.7) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 3 (0.8) | 3 (0.8) | 3/397 (0.8) | 4/411 (1.0) |

| Prior transient ischemic attack | 3 (0.8) | 4 (1.0) | 3/397 (0.8) | 5/411 (1.2) |

| Body mass index, median (IQR) | 22.9 (21.0-24.0) | 23.7 (21.0-24.0) | 22.7 (20.1-24.0) | 23.5 (21.0-24.0) |

| Blood pressure at randomization | ||||

| Systolic | ||||

| Median (IQR), mm Hg | 154 (139-170) | 150 (136-166) | 152 (138-170) | 150 (136-165) |

| >140 mm Hg | 242 (66.5) | 250 (63.1) | 257/397 (64.7) | 250/411 (60.8) |

| Diastolic | ||||

| Median (IQR), mm Hg | 90 (80-98) | 88 (80-97) | 90 (80-98) | 88 (80-97) |

| >90 mm Hg | 142 (39.0) | 142 (35.9) | 151/397 (38.0) | 145/411 (35.3) |

| Blood glucose | ||||

| Median (IQR), mg/dL | 118.8 (102.8-164.0) | 121.0 (102.6-160.7) | 120.8 (102.6-162.2) | 120.6 (102.6-163.8) |

| >126 mg/dL | 128/293 (43.7) | 143/324 (44.1) | 144/321 (44.9) | 150/335 (44.8) |

| NIHSS score at randomization, median (IQR)d | 9 (7-12) | 8 (6-12) | 9 (7-12) | 9 (6-12) |

| GRASPS score at randomization, median (IQR)e | 75 (71-79) | 74 (70-78) | 75 (71-79) | 74 (70-78) |

| ASPECTS score at randomization, median (IQR)f | 9 (8-10) | 9 (8-10) | 9 (8-10) | 9 (8-10) |

| Estimated premorbid function (mRS score)g | ||||

| No symptoms (score of 0) | 295 (81.0) | 314 (79.3) | 318/397 (80.1) | 326/411 (79.3) |

| Symptoms without any disability (score of 1) | 65 (17.9) | 76 (19.2) | 75/397 (18.9) | 79/411 (19.2) |

| Mild disability (score of 2) | 4 (1.1) | 6 (1.5) | 4/397 (1.0) | 6/411 (1.5) |

| Presumed stroke causeh | ||||

| Undetermined | 233/356 (65.4) | 270/389 (69.4) | 242/370 (65.4) | 276/401 (68.8) |

| Large artery atherosclerosis | 67/356 (18.8) | 74/389 (19.0) | 71/370 (19.2) | 76/401 (19.0) |

| Small artery occlusion | 33/356 (9.3) | 29/389 (7.5) | 34/370 (9.2) | 33/401 (8.2) |

| Cardioembolic | 20/356 (5.6) | 15/389 (3.9) | 20/370 (5.4) | 15/401 (3.7) |

| Other | 3/356 (0.8) | 1/389 (0.3) | 3/370 (0.8) | 1/401 (0.2) |

| Location of responsible vesseli | ||||

| Anterior stroke | 157/195 (80.5) | 153/200 (76.5) | 167/205 (81.5) | 162/209 (77.5) |

| Posterior stroke | 33/195 (16.9) | 43/200 (21.5) | 33/205 (16.1) | 43/209 (20.6) |

| Anterior and posterior stroke | 5/195 (2.6) | 4/200 (2.0) | 5/205 (2.4) | 4/209 (1.9) |

| Location of responsible artery (≥50% stenosis)i | ||||

| Internal carotid | 18/75 (24.0) | 16/85 (18.8) | 20/82 (24.4) | 16/88 (18.2) |

| Middle cerebral | 44/75 (58.7) | 49/85 (57.6) | 47/82 (57.3) | 52/88 (59.1) |

| Anterior cerebral | 2/75 (2.7) | 5/85 (5.9) | 2/82 (2.4) | 5/88 (5.7) |

| Posterior cerebral | 4/75 (5.3) | 5/85 (5.9) | 4/82 (4.9) | 5/88 (5.7) |

| Basilar | 5/75 (6.7) | 6/85 (7.1) | 5/82 (6.1) | 6/88 (6.8) |

| Vertebral | 4/75 (5.3) | 4/85 (4.7) | 4/82 (4.9) | 4/88 (4.5) |

| Time from symptom onset to alteplase, median (IQR), min | 160 (120-208) | 155 (114-201) | 160 (120-208) | 156 (115-201) |

| Time from symptom onset to discharge, median (IQR), d | 10 (7-13) | 9 (7-13) | 10 (7-12) | 10 (6-13) |

| Endovascular treatment | 10 (2.7) | 13 (3.3) | 15/397 (3.7) | 17/411 (4.1) |

Defined as consuming alcohol at least once a week within 1 year prior to the onset of the disease.

Comorbidities based on family or patient report.

Prior ischemic stroke referred only to the patients with premorbid modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores ≤1.

Scores on National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) range from 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating more severe neurologic deficit; a mean NIHSS score of 8 to 9 indicates moderate neurologic deficit.

The GRASPS score uses 6 clinical variables to estimate risk of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage after intravenous alteplase and ranges from 0 to 101, with higher scores indicating greater risk.

The Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS) determines the extent of ischemic tissue based on computed tomography imaging. Scores range from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating less infarct volume.

Scores on the mRS of functional disability range from 0 (no symptoms) to 6 (death).

The presumed stroke cause was classified according to the Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) using clinical findings, brain imaging, and laboratory test results. Other causes included nonatherosclerotic vasculopathies, hypercoagulable states, and hematologic disorder.

Definite conclusions based on vessel examination. The diagnosis was based on the clinician’s interpretation of the clinical features and examination results at the time of hospital discharge.

Primary Outcome

The percentage of patients with mRS scores of 0 to 1 at 90 days was 63.8% (210/329) in the argatroban plus alteplase group and 64.9% (238/367) in the alteplase alone group. In the full analysis set population, the risk of having an excellent outcome showed no significant difference between the argatroban plus alteplase and alteplase alone groups (unadjusted RD, −1.0% [95% CI, −8.1% to 6.1%]; RR, 0.98 [95% CI, 0.88-1.10]; P = .78; Table 2 and Figure 2). Given that there were 121 patients (73 in the argatroban plus alteplase group and 48 in alteplase alone group) with missing values in the primary outcome, sensitivity analyses were performed and similar RR results were also observed (eTable 2 in Supplement 3). The difference in the risks of having a primary outcome remained nonsignificant after adjustment for prespecified prognostic variables (RD, −1.0% [95% CI, −7.6% to 5.7%]; RR, 1.03 [95% CI, 0.86-1.23]; P = .78; Table 2). The per-protocol analysis yielded similar results (unadjusted RD, −0.3% [95% CI, −7.4% to 6.9%]; RR, 1.00 [95% CI, 0.89-1.11]; P = .95; adjusted RD, −0.4% [95% CI, −7.0% to 6.3%]; RR, 0.98 [95% CI, 0.89-1.08]; P = .65; eFigure 3 and eTable 3 in Supplement 3).

Table 2. Primary Analysis of Outcomes in the Full Analysis Set.

| Outcome | No. (%) | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argatroban plus alteplase (n = 364) | Alteplase alone (n = 396) | Risk difference (95% CI) | Risk ratio (95% CI) | P value | Risk difference (95% CI) | Risk ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| Primary | ||||||||

| mRS score of 0 to 1 at 90 db,c | 210/329 (63.8) | 238/367 (64.9) | −1.0 (−8.1 to 6.1) | 0.98 (0.88 to 1.10) | .78 | −1.0 (−7.6 to 5.7) | 1.03 (0.86 to 1.23) | .78 |

| Secondary | ||||||||

| mRS score of 0 to 2 within 90 dc | 250/329 (76.0) | 280/367 (76.3) | −0.3 (−6.6 to 6.0) | 1.00 (0.92 to 1.08) | .93 | 0.9% (−5.2 to 6.9) | 0.99 (0.77 to 1.26) | .92 |

| Early neurologic improvement within 48 hc,d | 251 (69.0) | 269 (67.9) | 1.0 (−5.6 to 7.6) | 1.03 (0.84 to 1.27) | .76 | 1.0 (−5.7 to 7.7) | 1.03 (0.84 to 1.28) | .77 |

| Early neurologic deterioration within 48 hc,e | 13 (3.6) | 20 (5.1) | −1.5 (−4.4 to 1.4) | 0.71 (0.36 to 1.40) | .31 | −1.7 (−4.5 to 1.2) | 0.69 (0.35 to 1.37) | .26 |

| Change in NIHSS score at day 14 from baseline, median (IQR)f | −0.85 (−1.61 to −0.25) | −0.81 (−1.95 to −0.29) | GMR, −0.03 (−0.16 to 0.11) | .69 | GMR, −0.01 (−0.15 to 0.12) | .85 | ||

| Stroke or other vascular events within 90 dg | 1/329 (0.3) | 1/367 (0.3) | Hazard ratio, 1.12 (0.07 to 17.94) | .94 | Hazard ratio, 0.78 (0.04 to 15.16) | .87 | ||

| mRS score distribution at 90 dc,h | Odds ratio, 1.06 (0.81 to 1.39) | .66 | Odds ratio, 1.01 (0.58 to 1.76) | .98 | ||||

Abbreviations: GMR, geometric mean ratio; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

Adjusted for prespecified prognostic variables (age, sex, NIHSS score at randomization, time from the onset of symptoms to thrombolysis, premorbid function [mRS score of 0 or 1], and history of stroke or transient ischemic attack).

mRS scores range from 0 to 6; a score of 0 indicates no symptoms; 1, symptoms without clinically significant disability; 2, slight disability; 3, moderate disability; 4, moderately severe disability; 5, severe disability; and 6, death.

Calculated using a generalized linear model.

Early neurologic improvement was defined as a decrease of ≥2 on the NIHSS score between baseline and 48 hours.

Early neurologic deterioration was defined as an increase of ≥4 on the NIHSS score between baseline and 48 hours, but not the result of cerebral hemorrhage.

NIHSS scores range from 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating greater stroke severity. The log (NIHSS score + 1) was analyzed using a generalized linear model.

Calculated using Cox regression model.

As a post hoc analysis, this outcome was used to describe a shift in measures of functioning according to the full range of scores on the mRS at 90 days.

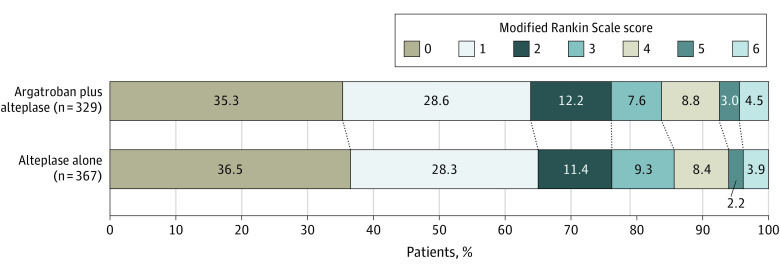

Figure 2. Distribution of Modified Rankin Scale Scores at 90 Days in the Full Analysis Set.

A total of 760 patients were included in the full analysis set; however, 696 patients (329 in the argatroban plus alteplase group and 367 in the alteplase alone group) with 90-day follow-up data were included in the analysis of the primary outcome. The raw distribution of scores is shown. Scores ranged from 0 to 6, with 0 indicating no symptoms; 1, symptoms without clinically significant disability; 2, slight disability; 3, moderate disability; 4, moderately severe disability; 5, severe disability; and 6, death. Treatment with argatroban plus alteplase was associated with an adjusted risk difference of −1.0% (95% CI, −7.6% to 5.7%; P = .78) for the outcome of a score of 0 or 1 on the modified Rankin Scale at 90 days. The overall distribution of scores was not statistically significant in the ordinal logistic analysis (odds ratio, 1.06 [95% CI, 0.81-1.39]; P = .66; adjusted odds ratio, 1.01 [95% CI, 0.58-1.76]; P = .98).

Secondary Outcomes

No significant differences were observed in the secondary outcomes in both the unadjusted and adjusted analysis, including the risks of having an mRS score of 0 to 2, early neurologic improvement within 48 hours, early neurologic deterioration within 48 hours, change in NIHSS score compared with randomization at 14 days, and stroke or other vascular events within 90 days (Table 2). In the per-protocol analysis, similar results were obtained in both unadjusted and adjusted per-protocol analyses (eTable 3 in Supplement 3). A post hoc ordinal logistic regression analysis showed no significant differences in the mRS score improvement at 90 days, in which the proportional odds assumption was met (P = .94; Table 2 and eTable 3 in Supplement 3).

A prespecified subgroup analysis showed no evidence of effect modification in the risks of having a primary outcome between the argatroban plus alteplase and alteplase alone groups by age, sex, NIHSS score at randomization, endovascular therapy, large artery occlusion, time from the onset of symptoms to treatment, mRS score at admission, and history of stroke or transient ischemic attack (eFigure 4 in Supplement 3). The results of the per-protocol analysis were similar to those of the full analysis set population for the primary outcome (eFigure 5 in Supplement 3).

Adverse Events

The occurrence of adverse events was similar across the 2 groups, including symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, other intracranial bleeding events, major bleeding events, other bleeding events, and other most common adverse events between the 2 groups (Table 3).

Table 3. Adverse Events in the Safety Populationa.

| Adverse event | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Argatroban plus alteplase (n = 383) | Alteplase alone (n = 397) | |

| Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage definition | ||

| ECASS-IIb | 8 (2.1) | 7 (1.8) |

| SITS-MOSTc | 8 (2.1) | 7 (1.8) |

| NINDSd | 13 (3.4) | 14 (3.5) |

| HBCe | 9 (2.3) | 8 (2.0) |

| Radiologic hemorrhage type | ||

| Parenchymal hematoma | ||

| Type 2f | 9 (2.3) | 10 (2.5) |

| Type 1g | 7 (1.8) | 8 (2.0) |

| Hemorrhagic infarction | ||

| Type 2h | 8 (2.1) | 6 (1.5) |

| Type 1i | 9 (2.3) | 8 (2.0) |

| Remote parenchymal hemorrhagej | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.8) |

| Major systemic bleedingk | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) |

| Other bleeding eventsl | 14 (3.7) | 10 (2.5) |

| Other most common adverse eventsm | 46 (12.0) | 43 (10.8) |

The safety population consisted of all randomized participants who received at least 1 dose of the study drug.

The European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS) defines symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage as any evidence of bleeding on the head computed tomography imaging associated with clinically significant neurologic deterioration (increase in National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] score ≥4 points) in the opinion of the clinical investigator or independent safety monitor.

The Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke Monitoring Study (SITS-MOST) defined symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage as local or remote parenchymal hemorrhage type 2 on the imaging scan 22 to 36 hours after treatment combined with a neurologic deterioration of 4 points or more on the NIHSS score from baseline, or from the lowest NIHSS value between baseline and 24 hours, or leading to death.

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study (NINDS) defined symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage as any hemorrhage plus any neurologic deterioration (NIHSS score ≥1) or that leads to death within 7 days.

The Heidelberg Bleeding Classification (HBC) defined symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage as new intracranial hemorrhage detected by brain imaging associated with any of the following: (1) increase of ≥4 points in total NIHSS score at the time of diagnosis compared with immediately before worsening (note that a 4-point change is not compared with the baseline admission NIHSS score but instead to the immediate predeterioration neurologic status), (2) increase of ≥2 points in 1 NIHSS category, (3) leading to intubation/hemicraniectomy/endovascular thrombectomy placement or other major medical/surgical intervention, or (4) absence of alternative explanation for deterioration.

Parenchymal hematoma type 2 was defined as confluent bleeding occupying more than 30% of the infarct volume and causing significant mass effect.

Parenchymal hematoma type 1 was defined as confluent bleeding occupying less than 30% of the infarct volume with some slight mass effect.

Hemorrhagic infarction type 2 was defined as confluent petechiae within the infarcted area but no space-occupying effect.

Hemorrhagic infarction type 1 was defined as small petechiae along the margins of the infarct.

Remote parenchymal hemorrhage was defined as intracranial hemorrhage outside the infarcted brain tissue.

Major systemic bleeding was defined as a decrease in the hemoglobin level by ≥2 g/dL or a transfusion of ≥2 U of blood.

Other bleeding events included skin, mucous membrane, gastrointestinal, urine, and gum bleeding.

Other most common adverse events included constipation, insomnia, pneumonia, dyspnea, headache, and vomiting.

Discussion

This trial showed that treatment with argatroban plus intravenous alteplase compared with alteplase alone did not result in a significantly greater likelihood of excellent functional outcome at 90 days or identify a signal of harm among patients with acute ischemic stroke. Furthermore, there was no evidence of effect modification of prespecified subgroups on the treatment effect on the primary end point.

This study differed from previous studies in 3 major ways.10,11,12 First, previous trials had relatively small sample sizes, ranging from 10 to 90 participants. To date, the present study, including 828 participants, is the largest randomized trial that provides robust statistical evidence on the effect of argatroban plus alteplase on AIS. Second, the included patients with median NIHSS scores of 8 to 9 had less severe neurologic deficit than those in previous studies with a median NIHSS score of 13 to 19.5.10,11 Third, the target population in previous studies was patients with large artery occlusion, whereas this was not mandatory in the current study. Although previous studies suggested that argatroban plus alteplase increased the percentage of patients with excellent functional outcomes,10,11 unexpectedly, argatroban plus alteplase did not show a significant improvement in neurologic function in the present study. The negative results may be attributed to the fewer enrolled patients with large artery occlusion in the current study (20.8%), because the promising results of argatroban plus alteplase were found in patients with a high percentage of large artery occlusion (51.1% to 100%),9,10,11 while argatroban plus alteplase may increase recanalization and decrease the reocclusion rates of large artery occlusion, resulting in better neurologic improvement. Namely, there may be a “floor” effect where smaller clots are lysed as much as possible by alteplase so there is less room for benefit, as opposed to larger clots that do not respond as well to alteplase. Because it is impractical to perform vessel imaging before intravenous thrombolysis in most stroke centers in China, large artery occlusion was not mandatory in this trial design. In addition, the rapid development of endovascular treatment after 5 clinical trials resulted in more patients with large artery occlusion receiving endovascular treatment.4 Collectively, these 2 reasons resulted in a lower proportion of patients with large artery occlusion enrolled in the trial. Having a similar profile of enrolled patients and study aim to this trial, the Multi-arm Optimization of Stroke Thrombolysis (MOST; NCT03735979)21 study is ongoing and the results will bring further evidence about the efficacy and safety of argatroban plus alteplase therapy.

In the current study, there was no effect of argatroban plus alteplase on early functional outcome, such as early neurologic improvement at 48 hours, early neurologic deterioration at 48 hours, or change in NIHSS score compared with randomization at 14 days. The lack of a significant effect on early outcomes correlated well with the negative primary outcome because the changes in these early outcomes, such as an increase in early neurologic improvement and a decrease in early neurologic deterioration, will result in the high risk of excellent functional outcome at 90 days. Furthermore, no significant difference in risk of having other secondary outcomes, such as stroke or other vascular events within 90 days, was found between the groups.

For the adverse events, similar rates of bleeding events were observed between the argatroban plus alteplase group and the alteplase alone group, which was consistent with previous studies.10,11 In this trial, the symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage rate was 1.8% to 2.1%, which was lower than in previous studies.10,11 This phenomenon could be due to the lower median NIHSS score at risk in the present study, which was comparable to recent studies involving a similar population: Chinese population with moderate neurologic function (median NIHSS score of 6 to 8) and similar definition of symptomatic intercranial hemorrhage.22,23 Despite the neutral results in this trial, the finding that no harmful profile of argatroban was observed in patients who received intravenous alteplase suggests the possible safety and feasibility of anticoagulants immediately after thrombolysis, which was prohibited by the current guidelines.1

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, more patients dropped out in the argatroban plus alteplase group than the alteplase alone group due to less willingness to adhere to the study protocol among patients and their families randomized to the argatroban plus alteplase group. As a result, the number of patients in the argatroban plus alteplase group (n = 364) did not meet the minimum sample size (n = 367) that was required according to the power calculation; thus, the lower statistical power and imbalanced sample sizes between the groups cannot be ignored. In addition, there was a large difference in the percentage of patients with excellent functional outcome between the assumed values in the sample size calculation (21%) and observed values in this trial (64%). The difference might be attributed to the enrolled population with milder neurologic deficit (a median NIHSS score of 9 vs a median NIHSS score of 13-19.5 in previous studies10,11) as well as the improvement in stroke care over time. Second, due to the open-label design, the present study did not conceal the assigned treatment from the participants and physicians. On the other hand, blinded end point assessments were used to reduce measurement bias and try to ensure that the primary end point was measured objectively. Third, a lower proportion of patients with large artery occlusion was enrolled in the trial than in previous studies,10,11 which may be the main cause of the negative results of this trial. Thus, the effect of alteplase plus argatroban in patients with large artery occlusion warrants investigation in future trials. In addition, endovascular thrombectomy was used infrequently because most participating sites did not have endovascular thrombectomy capability. This limits generalizability to sites with readily available endovascular thrombectomy. Fourth, argatroban (100-μg/kg bolus followed by 1 μg/kg per minute) was used in our trial based on previous studies,10,11 while high-dose argatroban (100-μg/kg bolus followed by 3 μg/kg per minute) was used in previous studies.11,12,21 In addition, only 23.2% patients met target APTT at 2 hours, and it took approximately 5 hours to reach target APTT (eTable 5 and eFigure 6 in Supplement 3). The low dose of argatroban and low target APTT rate may partially contribute to the neutral results, because high doses of argatroban and good target APTT theoretically may produce a better improvement of clinical outcome if symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage did not increase. Fifth, the dropout rate in this trial may have introduced attrition bias or possible confounding. Sixth, further confirmation of these conclusions in non-Chinese populations would be welcome, given the differences in body mass index, comorbidities, and etiology of patients with AIS.

Conclusions

Among patients with AIS, treatment with argatroban plus intravenous alteplase compared with alteplase alone did not result in a significantly greater likelihood of excellent functional outcome at 90 days.

Trial protocol

Statistical analysis plan

eAppendix

eMeothds

eFigures

eTables

Nonauthor collaborators

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50(12):e344-e418. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rha JH, Saver JL. The impact of recanalization on ischemic stroke outcome: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2007;38(3):967-973. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000258112.14918.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexandrov AV, Grotta JC. Arterial reocclusion in stroke patients treated with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator. Neurology. 2002;59(6):862-867. doi: 10.1212/WNL.59.6.862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, et al. ; HERMES collaborators . Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet. 2016;387(10029):1723-1731. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00163-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saqqur M, Molina CA, Salam A, et al. ; CLOTBUST Investigators . Clinical deterioration after intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator treatment: a multicenter transcranial Doppler study. Stroke. 2007;38(1):69-74. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000251800.01964.f6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen L, Cao S, Yang J. Argatroban plus aspirin versus aspirin in acute ischemic stroke. Neurol Res. 2018;40(10):862-867. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2018.1495882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hosomi N, Naya T, Kohno M, Kobayashi S, Koziol JA; Japan Standard Stroke Registry Study Group . Efficacy of anti-coagulant treatment with argatroban on cardioembolic stroke. J Neurol. 2007;254(5):605-612. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0365-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jang IK, Gold HK, Leinbach RC, Fallon JT, Collen D. In vivo thrombin inhibition enhances and sustains arterial recanalization with recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator. Circ Res. 1990;67(6):1552-1561. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.67.6.1552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris DC, Zhang L, Zhang ZG, et al. Extension of the therapeutic window for recombinant tissue plasminogen activator with argatroban in a rat model of embolic stroke. Stroke. 2001;32(11):2635-2640. doi: 10.1161/hs1101.097390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barreto AD, Alexandrov AV, Lyden P, et al. The argatroban and tissue-type plasminogen activator stroke study: final results of a pilot safety study. Stroke. 2012;43(3):770-775. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.625574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barreto AD, Ford GA, Shen L, et al. ; ARTSS-2 Investigators . Randomized, multicenter trial of ARTSS-2 (argatroban with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute stroke). Stroke. 2017;48(6):1608-1616. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.016720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berekashvili K, Soomro J, Shen L, et al. Safety and feasibility of argatroban, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator, and intra-arterial therapy in stroke (ARTSS-IA study). J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;27(12):3647-3651. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.08.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyden P, Pereira B, Chen B, et al. Direct thrombin inhibitor argatroban reduces stroke damage in 2 different models. Stroke. 2014;45(3):896-899. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang Y, Zhou Z, Pan Y, Chen H, Wang Y; ARAIS Protocol Steering Group . Randomized trial of argatroban plus recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke (ARAIS): rationale and design. Am Heart J. 2020;225:38-43. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2020.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugg RM, Pary JK, Uchino K, et al. Argatroban tPA stroke study: study design and results in the first treated cohort. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(8):1057-1062. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.8.1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molina CA, Alvarez-Sabín J, Montaner J, et al. Thrombolysis-related hemorrhagic infarction: a marker of early reperfusion, reduced infarct size, and improved outcome in patients with proximal middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke. 2002;33(6):1551-1556. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000016323.13456.E5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arenillas JF, Rovira A, Molina CA, Grivé E, Montaner J, Alvarez-Sabín J. Prediction of early neurological deterioration using diffusion- and perfusion-weighted imaging in hyperacute middle cerebral artery ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2002;33(9):2197-2203. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000027861.75884.DF [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sacco RL, Kasner SE, Broderick JP, et al. An updated definition of stroke for the 21st century: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(7):2064-2089. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e318296aeca [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao NM, Levine SR, Gornbein JA, Saver JL. Defining clinically relevant cerebral hemorrhage after thrombolytic therapy for stroke: analysis of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke tissue-type plasminogen activator trials. Stroke. 2014;45(9):2728-2733. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiorelli M, Bastianello S, von Kummer R, et al. Hemorrhagic transformation within 36 hours of a cerebral infarct: relationships with early clinical deterioration and 3-month outcome in the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study I (ECASS I) cohort. Stroke. 1999;30(11):2280-2284. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.30.11.2280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deeds SI, Barreto A, Elm J, et al. The multiarm optimization of stroke thrombolysis phase 3 acute stroke randomized clinical trial: rationale and methods. Int J Stroke. 2021;16(7):873-880. doi: 10.1177/1747493020978345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng H, Yang Y, Chen H, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3-4.5 hours after acute ischaemic stroke: the first multicentre, phase III trial in China. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2020;5(3):285-290. doi: 10.1136/svn-2020-000337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li S, Pan Y, Wang Z, et al. Safety and efficacy of tenecteplase versus alteplase in patients with acute ischaemic stroke (TRACE): a multicentre, randomised, open label, blinded-endpoint (PROBE) controlled phase II study. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2022;7(1):47-53. doi: 10.1136/svn-2021-000978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

Statistical analysis plan

eAppendix

eMeothds

eFigures

eTables

Nonauthor collaborators

Data sharing statement