Abstract

A 43-year-old woman died suddenly and was found at PM to have a ruptured thoracic aortic aneurysm. The endothelial surface of the aorta showed a ‘tree-bark’ appearance. Histology of the aneurysm wall showed a patchy, mainly perivascular, plasma cell infiltrate. Multiple spirochete-like organisms were identified on T. pallidum IHC. However, PM syphilis serology (screen including rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and T. pallidum particle agglutination (TPPA)) on femoral blood was negative. PCR testing on FFPE aortic wall tissue was negative. Further history revealed routine antenatal syphilis screening tests had been negative, no known history or risk of exposure to syphilis or other treponemes. This case raises the possibility of false negative syphilis testing. While acknowledged in RPR testing, with the modern testing regime using multiple methods, the rate of false negative results is now thought to be markedly reduced, and false positive results are a much greater problem in clinical medicine. The most common cause of false negative results is early in primary infection before an immune response has been mounted and in those patients that are immunocompromised. False negative results are also more often seen in tertiary syphilis, as in this case. Newer testing methods which include 16S rRNA sequencing have become available and early discussion with a microbiologist would be recommended. Strong macroscopic and microscopic suggestion of syphilis as the cause of the aneurysm makes it necessary to include the possibility of infection in the Post Mortem Report to Coroner as this will have implications for her sexual partners and children.

Keywords: Syphilis, Aortitis, Aneurysm, Serology, False negative

Introduction

There are many causes for thoracic aortic aneurysms, including atherosclerosis, connective tissue disorders (such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or Marfan syndrome), cystic medial necrosis, Takayasu’s arteritis, family history/genetic factors, and infection by Treponema pallidum (syphilitic aortitis).

Syphilis infection is a global concern with the World Health Organisation reporting 7.1 million new infections in 2020 with incidence rates of between 0.32 per 1000 person-years in the South-East Asia region and 4.8 per 1000 person-years in the region of the Americas [1]. In New Zealand, the prevalence of syphilis has been steadily increasing since 2013, but decreased again throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, which may be due to changed testing patterns or durations of limited social interactions during lockdowns [2]. In addition, congenital syphilis has re-emerged. Syphilis infection is therefore of importance as a causative disease in sudden death cases handled by forensic medicine.

The current paper discusses a fatal case of a ruptured thoracic aortic aneurysm where the macroscopic and microscopic findings are strongly suggestive of syphilitic aortitis but confirmatory serology and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing were negative. This poses a challenge for the forensic pathologist to provide a conclusive report and is problematic for the clinicians looking after the sexual partners and children of the deceased.

Case report

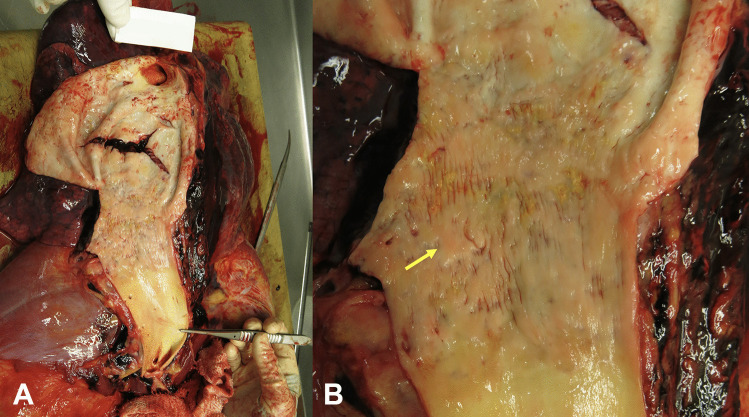

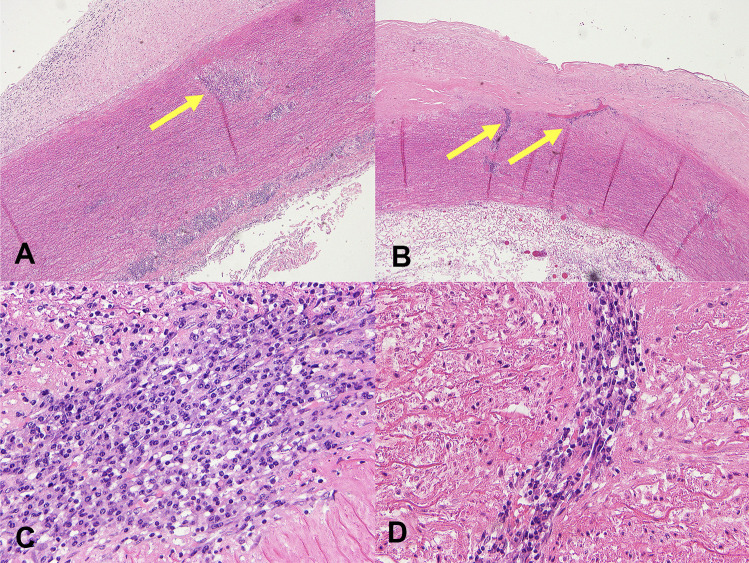

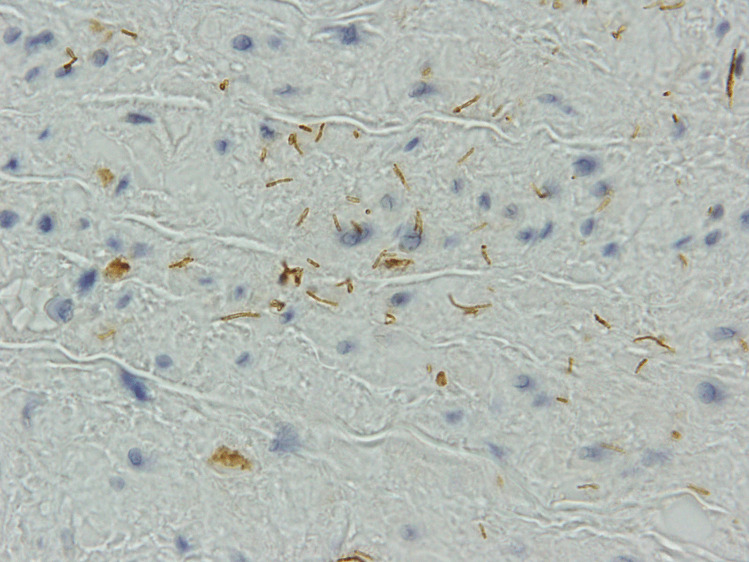

A 43-year-old woman died suddenly with chest pain. At post mortem (PM), a ruptured thoracic aortic aneurysm with bleeding into right pleural cavity was found that was consistent with cause of death. The fusiform aneurysm was approximately 55 mm in maximum diameter. The endothelial surface of the aorta showed a ‘tree-bark’ appearance (Fig. 1). There was an abrupt transition to normal aorta in the distal arch of the aorta. No atherosclerosis was seen throughout. The heart was enlarged at 440 g (predicted heart weight for a 170 cm tall adult female is 267 g, range 173–411 g [3]) but with no other abnormalities, specifically no abnormalities of the heart valves or coronary arteries. Histology of the aortic wall showed fibrointimal hyperplasia, and a patchy, mainly perivascular, variably mild to marked plasma cell infiltrate in the media and adventitia, with occasional sheets of plasma cells within the intima (Fig. 2). There were foci of elastin loss, confirmed with Verhoeff-Van Gieson stain, within relatively intact media (Fig. 3). Multiple spirochete-like organisms were identified on T. pallidum immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 4). PM serology was requested on femoral artery blood. This included a syphilis EIA, rapid plasma reagin (RPR), and T. pallidum particle agglutination (TPPA), all of which were negative.

Fig. 1.

Clinical photographs A demonstrating a ruptured aneurysm within the distal arch of the aorta. B Close up view of the intimal surface of the thoracic aorta adjacent to the ruptured aneurysm demonstrating a ‘tree-bark’ appearance (arrow)

Fig. 2.

Photomicrographs of H&E slides A, B demonstrating aortic wall at low power with fibrointimal hyperplasia, and a patchy, mainly perivascular, variably mild to marked plasma cell infiltrate in the media and adventitia (arrows), with occasional sheets of plasma cells within the intima. C Higher power demonstrating a sheet of plasma cells within the media. D Higher power demonstrating perivascular plasma cells

Fig. 3.

Photomicrograph of aortic wall stained with Verhoeff-Van Gieson stain demonstrating foci of elastin loss within relatively intact media

Fig. 4.

Photomicrograph of aortic wall stained with T. pallidum immunohistochemistry demonstrating multiple spirochete-like organisms

Further history was obtained. The deceased had no known exposure to syphilis, nor risk factors for other (rare) treponemal organisms, such as overseas travel. Routine antenatal syphilis screening tests for three previous pregnancies had all been negative (as was screening for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)).

The case was discussed with microbiologists to better determine the sensitivity of syphilis testing and further testing options. The formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) aortic wall tissue was sent for syphilis PCR testing and was negative.

Discussion

This case raises the possibility of false negative syphilis testing, which in turn has implications for the deceased’s family in terms of diagnostic investigations and clinical management.

The characteristic findings of syphilitic aortitis are thickening of the aortic wall with a ‘tree-bark’ appearance of the intimal surface and the presence of an aneurysm [4]. Other syphilitic cardiovascular manifestations are aortic valve stenosis or regurgitation, and coronary artery ostial stenosis [5]. Microscopic features of syphilitic aortitis are fibrous or fibrocalcific thickening of the intima, fibrous thickening of the adventitia, and focal collections, often perivascular, of plasma cells [6]. The media is not thickened and may have focally interrupted elastic fibres with transversely orientated fibrous scars. Aneurysms are thought to occur due to the changes that occur in the media as described. The vasa vasorum, only present in the thoracic aorta and where syphilitic aortitis is seen, are understood to be the targeted vessels of the organism [5].

The current case demonstrated the characteristic findings described above. Differential diagnoses, as listed in the introduction, were considered unlikely due to a lack of personal or family history of connective tissue disorders or arteritis, and an absence of atherosclerosis. With Takayasu’s arteritis, the inflammation seen histologically is granulomatous, which was not seen in the current case. With cystic medial necrosis, the elastic fibres would typically be more severely affected and there would not be the collections of plasma cells seen in the current case.

Recent literature in the field of forensic medicine has reported cases of syphilitic aortitis.

This includes two case reports of men who died from ruptured syphilitic aortic aneurysms [7, 8]. One of the men was coinfected with HIV. This case from Japan highlights the importance of screening for HIV in patients found to have syphilis, and vice versa [8]. Of note, in both cases, the syphilis serology was positive. A review of pathology archives by Byard in 2018 details four cases of syphilis with cardiovascular manifestations [5]. All showed involvement of the thoracic aorta with aneurysm formation and the characteristic ‘tree bark’ wrinkling of the intimal surface, as seen in the current case.

Testing is done in New Zealand in individuals with signs or symptoms compatible with syphilis, as well as routinely part of antenatal screening. For those with clinical suspicion of T. pallidum infection, testing includes a treponemal and a non-treponemal serological test. Most laboratories in NZ will screen with an enzyme immunoassay (EIA); this includes antenatal screening.

While false negative results have been well described for RPR testing (a non-treponemal test) [9], with the modern testing regime using multiple serological methods, the rate of false negative results is now thought to be markedly reduced. False positive results present a much greater problem in clinical medicine. The most common cause of false negative tests is testing in early primary infection and immunocompromised patients. The case described here does not fall into either category. The limitations of serology include biological false positives (BFPs), especially in pregnancy, and the possibility that seroconversion does not occur when treatment is administered early in primary syphilis [10, 11]. The diagnostic performance of current laboratory tools is summarised in a recent paper by Luo et al. [12]. In tertiary syphilis, while RPR is commonly negative, TPPA would be expected to remain positive [9, 12]. A study by Park et al. found a sensitivity of 86.8–98.5% for TPPA in late latent disease [13].

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is used to detect T. pallidum in tissue specimens, as described in the current case. IHC also has issues with sensitivity and specificity. As the stage of syphilis increases, the sensitivity typically decreases [6] likely due to reduced numbers of organisms. Cross-reactivity with non-Treponema spirochetes has been described with the syphilis IHC and these organisms form part of the normal microbiota of the oropharynx and gastrointestinal tract [14].

In recent decades, molecular methods for diagnosing syphilis have become available. PCR is a very specific and sensitive method, especially in the first and second stages of syphilis. However, the overall sensitivity of syphilis PCR drops significantly in the third stage [6, 15]. This is again most likely due to reduced numbers of the organism, though this would not seem to be an explanation for a false negative result in the current case. The current case did use FFPE tissue for testing, and it is known that the processing required to create a FFPE block degrades DNA and introduces PCR inhibitors, which reduces the sensitivity of PCR [16].

Early treatment in syphilis is paramount to prevent the involvement of the internal organs (which defines the tertiary stage of syphilis), such as an aortic aneurysm. While the macroscopic and microscopic post-mortem findings in the current case are highly suggestive of syphilitic aortitis, they are non-specific and can be present in other inflammatory processes of the aorta [17]. It is critical to establish a firm diagnosis wherever possible.

16S rRNA sequencing targeting the V3-V4 region of the syphilis organism is a relatively new molecular test and has previously been shown to assist in the diagnostic process of a patient with negative syphilis serology [18]. In brief, 16S rRNA uses sequencing techniques to sequence a relatively short gene found in all prokaryotes that encodes for part of the ribosome. Some areas of this gene are hypervariable allowing the test to identify species of bacteria with high sensitivity and specificity. This test could have been attempted in the current case had fresh tissue been taken for testing. Alternatively, the detection of non-Treponema spirochaetes by 16S rRNA sequencing might have assisted with the interpretation of positive IHC.

Considering the uncertainty around the diagnosis in this patient, the safest path is to follow up the deceased’s contacts (sexual partners and children) clinically and serologically to ensure that syphilis infection is not missed (acknowledging the possibility of further false negative serology). The Report for Coroner in this case must include discussion of the diagnostic uncertainly and warrants direct communication to ensure its ramifications are fully understood. This should include the offer to speak directly with family or the family’s usual health practitioner.

In summary, the current case highlights the difficulty in making a diagnosis of syphilitic aortitis despite multiple investigations including macroscopic findings at autopsy, microscopy including IHC, multiple antemortem and PM serological tests, and molecular testing. Early discussion with a microbiologist is advised in cases with high clinical suspicion in order to guide the collection of optimal samples, in this case fresh tissue for PCR-based molecular testing including 16S rRNA sequencing. Despite persisting diagnostic uncertainty, appropriate follow-up with contacts is critical.

Key points

The incidence of syphilis infection is increasing and should be considered in a case of ruptured aneurysm

Serology may be unhelpful especially in a case of tertiary syphilis

Early discussion with a microbiologist is recommended in cases of high clinical suspicion

Molecular techniques have become available, including 16S rRNA sequencing, to confirm diagnosis but may require special techniques including fresh tissue

Where uncertainty persists, the safest path is to follow up the cases contacts clinically and serologically

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Dr Katherine Hulme. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Dr Katherine Hulme and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

Not applicable to this case report.

Code availability

Not applicable to this case report.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Health and Disabilities Ethics Committees of New Zealand has confirmed that no ethical approval is required.

Consent for publication

The responsible coroner of the case has given consent to publish after discussion with the family and approval from them also.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Global progress report on HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections, 2021. Accountability for the global health sector strategies 2016–2021: actions for impact. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 2.ESR. Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI) surveillance (Dashboard). https://www.esr.cri.nz/our-services/consultancy/public-health/sti/ Accessed 8 Apr 2022.

- 3.Kitzman DW, Scholz DG, Hagen PT, Illstrup DM, Edwards WD. Age-related changes in normal human hearts during the first 10 decades of life. Part II (maturity): a quantitative anatomic study of 765 specimens from subjects 20 to 99 years old. Mayo Clin Proc. 1988;63:137–46. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(12)64946-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts WC, Ko JM, Vowels TJ. Natural history of syphilitic aortitis. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(11):1578–1587. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byard RW. Syphilis—cardiovascular manifestations of the great imitator. J Forensic Sci. 2018;63:1312–1315. doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.13709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Müller H, Eisendle K, Bräuninger W, Kutzner H, Cerroni L, Zelger B. Comparative analysis of immunohistochemistry, polymerase chain reaction and focus-floating microscopy for the detection of Treponema pallidum in mucocutaneous lesions of primary, secondary and tertiary syphilis. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:50–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kislov MA, Chauhan M, Krupin KN, Romanova OL, Byard RW. Sudden death due to rupture of an aortic syphilitic aneurysm. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2022;18(1):106–109. doi: 10.1007/s12024-021-00419-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ro A, Mori S, Kageyama N, Chiba S, Mukai T. Ruptured syphilitic aneurysm: a cause of sudden death in a man with human immunodeficiency coinfection. J Forensic Sci. 2019;64(5):1555–1558. doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.14046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peeling R, Ye H. Diagnostic tools for preventing and managing maternal and congenital syphilis: an overview. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:439–446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuddenham S, Katz SS, Ghanem KG. Syphilis laboratory guidelines: performance characteristics of nontreponemal antibody tests. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:S21–42. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ortiz DA, Shukla MR, Loeffelholz MJ. The traditional or reverse algorithm for diagnosis of syphilis: pros and cons. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:S43–51. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo Y, Xie Y, Xiao Y. Laboratory diagnostic tools for syphilis: current status and future propsects. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;10:574806. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.574806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park IU, Fakile YF, Chow JM, Gustafson KJ, Jost H, Schapiro JM, et al. Performance of treponemal tests for the diagnosis of syphilis. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(6):913–918. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruiz SJ, Procop GW, Tomsich RJ. Cross-reactivity of anti-treponema immunohistochemistry with non-treponema spirochetes: a simple call for caution. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:1021–1022. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2016-0004-LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou C, Zhang X, Zhang W, Duan J, Zhao F. PCR detection for syphilis diagnosis: status and prospects. J Clin Lab Anal. 2019;33. 10.1002/jcla.22890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Srinivasan M, Sedmak D, Jewell S. Effect of fixatives and tissue processing on the content and integrity of nucleic acids. Am J Pathol. 2002;161(6):1961–1971. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64472-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cocora M, Nechifor D, Lazar M-A, Mornos A. Impending aortic rupture in a patient with syphilitic aortitis. Vascular Health and Risk management. 2021;17:255–258. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S289455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chambers LC, Srinivasan S, Lukehart SA, Ocbamichael N, Morgan JL, Sylvan Lowens M, Fredericks DN, Golden MR, Manhart LE. Primary syphilis in the male urethra: a case report. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:1231–1234. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable to this case report.

Not applicable to this case report.