Abstract

The formation of carbon–carbon bonds via the intermolecular addition of alkyl radicals to alkenes is a cornerstone of organic chemistry and plays a central role in synthesis. However, unless specific electrophilic radicals are involved, polarity matching requirements restrict the alkene component to be electron deficient. This limits the scope of a fundamentally important carbon–carbon bond forming process that could otherwise be more universally applied. Herein, we introduce a polarity transduction strategy that formally overcomes this electronic limitation. Vinyl sulfonium ions are demonstrated to react with carbon-centered radicals, giving adducts that undergo in situ or sequential nucleophilic displacement to provide products that would be inaccessible via traditional methods. The broad generality of this strategy is demonstrated through the derivatization of unmodified complex bioactive molecules.

Since its discovery and establishment in the last century, the olefin hydroalkylation reaction via intermolecular addition of alkyl radicals to alkenes1 has been used extensively in chemical synthesis for the construction of carbon–carbon bonds.2 Decades of research have refined the versatility of this process, stimulating the invention of new reactivity frameworks for the stereoselective synthesis of organic molecules,3 and inspiring significant advances in total synthesis.4 The recent development of efficient approaches to promote radical reactions under mild conditions—e.g., photoredox catalysis,5,6 electrochemical methods,7 and earth abundant transition metal catalysis8—has further enhanced the scope and the utility of this chemistry,9−11 providing new catalytic strategies to access enantioenriched chiral building blocks12 and to selectively functionalize complex molecules.4

Despite the synthetic value of these processes, the strict polarity matching requirements between the radicals and the alkenes involved represent a fundamental limitation to the generality of this chemistry.1,13 While favorable frontier molecular orbital interactions ensure a smooth reaction between alkyl radicals (typically nucleophilic) and electron deficient alkenes 1 (Scheme 1a, left), the addition of the same radical species to electron rich olefins 3 (Scheme 1a, right) is kinetically unfavored and does not practically occur, unless specific electron deficient functional groups are introduced within the radical center to induce electrophilic character.1,13,14Thus, access to products4is not possible using traditional radical chemistry. While a strategy has been developed to circumvent adverse polarity requirements in radical chemistry in the context of hydrogen atom transfer processes—i.e., polarity reversal catalysis15—no strategies have ever been developed to overcome the scope limitations of the radical addition to alkenes. Therefore, a general methodology to address the scope restrictions above would greatly enhance the field of radical chemistry, thereby stimulating further advances in various areas of synthesis.

Scheme 1. (a) Polarity Matching Requirements in Radical Addition to Alkenes; (b) Polarity Transduction Strategy to Access Polarity-Mismatched Products; (c) Design of the Photocatalytic System.

We recently speculated that the strategic design of a composite process constituted by two elementary steps occurring in situ would circumvent the limitations mentioned above, allowing access to products 4 that are elusive to traditional methods. The strategy, described in Scheme 1b, uses alkene 5 equipped with a rationally designed functional group serving the role of a “polarity transducer”. Our polarity transducer would play the key role of converting the mismatched electron-rich polarity of the hypothetical π-system required to access products 4 into the matched electron-deficient polarity of the alkene moiety within 5. Then, after rapid radical addition to give intermediate 6, the polarity transducer group would be in situ displaced by a nucleophile, defining a practical alternative route to products 4.

In designing a suitable polarity transducer functional group, we took into consideration the following requisites. First, it should be electron deficient in nature to subtract electron density from the neighboring π-system, thus lowering the energy of the corresponding lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) to promote the addition of nucleophilic carbon-centered radicals.1,13 Second, it should be an excellent leaving group, to ensure rapid nucleophilic displacement to access desired product 4 from intermediate 6. Third, its structural and electronic features should inhibit radical polymerization, a process typically occurring in vinyl halides 8.16 Inspired by a seminal work from Barton et al.,17 we recently discovered that vinyl phosphonium ions readily undergo radical-based photoredox chemistry under visible light irradiation.18 Therefore, we surmised that structurally related vinyl sulfonium ions 9, a species known to undergo polar reaction with nucleophiles,19 would participate in a radical conjugate addition reaction. As sulfonium ions are known to act as good leaving groups in intramolecular processes,20 and occasionally in intermolecular processes,21 we envisioned that they would constitute ideal polarity transducers for our strategy, given that an opportune reagent 9 and a suitable catalytic cycle were designed.

Following the hypothesis above, we conceived the photocatalytic process depicted in Scheme 1c. Photocatalyst-induced single-electron transfer (SET) decarboxylative oxidation of carboxylic acids 10 would generate carbon-centered radicals 11 in solution.22 Due to the inductive effect of the electron-deficient cationic sulfonium moiety,23 we predicted that nucleophilic radicals 11 would undergo selective addition to the terminal carbon of the pendant vinyl system within 9. This would contrast with the reactivity observed with styrenyl sulfonium radical traps,24 in which addition occurs with opposite site-selectivity. Following the initial radical addition, the resulting electron-poor radical cation intermediate 12 would then undergo SET with the reduced photocatalyst (PC•–) to close the catalytic cycle, affording a transient intermediate sulfonium ylide that would be protonated under the reaction conditions to give adduct 6. Addition of a suitable nucleophile 7 to this reaction mixture would result in the nucleophilic displacement of the sulfonium group within 6, to afford desired products 4.

We commenced our investigation by exposing an acetonitrile mixture of model carboxylic acid N-Boc-isonipecotic acid 10a, vinyl systems 8–9, potassium phosphate, and photocatalyst 1,2,3,5-tetrakis(carbazol-9-yl)-4,6-dicyanobenzene (4CzIPN)25 to blue light irradiation, followed by the addition of 2-mercaptoethanol as a model nucleophile under mild heating (60 °C), Table 1.

Table 1. Optimization Studies.

| entrya,b | alkene (-X) | 4a (%) | 4b (%) | 4c (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Br (8) | 0 | – | – |

| 2 | +S(Ph)2[OTf]− (9a) | 35 | – | – |

| 3c | +S(Ph)2[OTf]− (9a) | 49 | – | – |

| 4 | +S(iPr)2[OTf]− (9b) | 90 | traces | traces |

| 5d | +S(CH2tBu)2[OTf]− (9c) | 71 | 62 | 65 |

| 6e | +S(CH2tBu)2[OTf]− (9c) | traces | – | – |

| 7f | +S(CH2tBu)2[OTf]− (9c) | traces | – | – |

Reactions were performed in 0.05 mmol scale, using 10a (1.0 equiv), 8–9 (1.5 equiv), 4CzIPN (5 mol %), and nucleophiles (2.5 equiv); see Supporting Information for full optimization details.

Unless otherwise stated, 1H NMR yield using CH2Br2 as internal standard.

3CzClIPN (5 mol %) used as photocatalyst.

Yields of isolated material in 0.2 mmol scale reactions.

Reaction carried out in the presence of 1 equiv of TEMPO.

No irradiation.

As expected, upon subjecting vinyl bromide 8 to the reaction conditions, polymerization was observed with no formation of desired compound 4a (Table 1, entry 1). Interestingly, the use of diphenyl vinyl sulfonium triflate 9a(26) led to the formation of desired product 4a in a moderate yield of 35% (entry 2). 1H NMR analysis of the reaction mixture revealed poor mass balance and a complex reaction mixture, due to the high reactivity of the diaryl sulfonium system and the known tendency of this moiety to undergo reductive cleavage.27 The use of a photocatalyst with weaker reductive power (3CzClIPN)28 only slightly improved the results (entry 3). We speculated that the decoration of the sulfonium moiety with bulky alkyl lateral chains would improve its stability, thereby enhancing the efficiency of the process. In consonance with this hypothesis, upon subjecting di-isopropyl vinyl sulfonium 9b(26) to our reaction conditions, the desired product 4a was obtained in 90% yield (entry 4). However, the generality of this system was limited, as only traces of products 4b and 4c were detected when the corresponding nucleophiles were employed, presumably due to a dominant undesired E2 elimination occurring in the sulfonium intermediate (see Table 1, top right).26 Thus, in order to expand the applicability of our system and minimize the undesired side-reactivity, we designed novel vinyl sulfonium ion 9c, equipped with bulky neo-pentyl alkyl lateral chains lacking β-protons. This novel reagent is a bench-stable solid, which can be stored in a standard freezer (−20 °C) for over 6 months with no detectable decomposition, and can be synthesized in high yield and multigram scale from commercial and affordable reagents, without any chromatographic purification needed (see Supporting Information for details). To our delight, this sulfonium salt ensured high generality to the process, with compounds 4a–c respectively isolated in 71%, 62%, and 65% yield (entry 5). In consonance with the radical nature of the process, performing the reaction in the presence of 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxyl free radical (TEMPO), or in the absence of irradiation, led to complete inhibition of the reactivity (entries 6 and 7).

With the optimized conditions in hand, we next looked at exploring the generality of our polarity transduction strategy. Thus, model radical precursor 10a was subjected to the reaction conditions, while varying the nature of the nucleophiles (Scheme 2). Thiol 4d was obtained in 61% yield from commercial sodium hydrosulfide. Sulfides 4a, 4e, and 4f were obtained in good to excellent yields respectively from primary, secondary, and aromatic thiols. The hypertension medicament captopril, carrying an additional carboxylic acid functionality, was conveniently converted into novel derivative 4g in 53% yield upon stoichiometric dianion generation with sodium hydride, followed by addition to the sulfonium mixture in DMF (see Supporting Information for more details). For this entry, as well as for the other complex nucleophiles used to access products 4k, 4l, and 4p, the stoichiometry of the system was adjusted to ensure the use of the valuable nucleophile as the limiting reagent (see Supporting Information). Alcohol 4h was accessed in 52% yield employing a solution of water/HMPA and potassium bicarbonate to promote solvolysis of the corresponding sulfonium intermediate. Primary and secondary ethers 4i and 4j were accessed in moderate yields using aliphatic alcohols as nucleophiles. For these two entries vinyl diphenyl sulfonium triflate was used, potassium tert-butoxide was employed as a base, and the less reductive photocatalyst 3CzClIPN28 was used (see Supporting Information for details). Aromatic ether 4b was obtained in 62% yield from phenol following standard reaction conditions. Unmodified alkaloid morphine was selectively converted into novel derivative 4k in 78% yield, without side reactivity arising from the nucleophilic allylic alcohol and the tertiary amine present in the complex scaffold. Ester derivative 4l was obtained in 82% yield from unmodified d-biotin, suggesting the possible future application of this chemistry in biotinylation strategies. Primary amine 4m was obtained in 79% yield using commercially available ammonia in methanol solution as nucleophilic nitrogen source. Secondary, tertiary, and aromatic amines 4c, 4n, and 4o were also obtained in good yields from the corresponding amine nucleophiles. The decongestant pseudoephedrine, bearing an amine and a neighboring alcohol functionality, underwent selective N-functionalization to provide novel derivative 4p in 59% yield.

Scheme 2. Reaction Scope.

Preformed captopril dianion was used as limiting reagent (see Supporting Information for full details).

After nucleophile addition, the reaction was sealed and heated to 120 °C.

Diphenyl vinyl sulfonium triflate 9a, KOtBu, catalytic 3CzClIPN were used and irradiation was performed at 0 °C.

Reaction stoichiometry: 10a (2.0 equiv), 9c (2.2 equiv), 4CzIPN (10 mol %), and nucleophile (1.0 equiv).

0.1 mmol scale.

After nucleophile addition, the reaction was sealed and heated to 100 °C.

Reactions were performed in a 0.2 mmol scale, using 10 (1 equiv), 9c (1.5 equiv), 4CzIPN (5 mol %), and nucleophile (typically 2.5 equiv), in CH3CN unless otherwise stated; see Supporting Information for full experimental details.Cz: carbazolyl.

We next looked at exploring the generality of our strategy by varying the nature of the carboxylic acid radical precursor. A variety of N- or O-containing heterocyclic carboxylic acids underwent the desired reactivity to afford compounds 4q–4s in good to excellent yields. Cyclic molecules with different ring size were successfully functionalized, with both macrocycle 4t as well as strained four-membered ring 4u obtained respectively in 51% and 73% yield from the corresponding carboxylic acids. Compound 4v was obtained in 77% yield from bulky adamantane carboxylic acid.

We next tested the methodology in the functionalization of structurally complex carboxylic acids. Compound 4w was obtained in 74% yield from vitamin E analogue Trolox, with no observable side reactivity arising from the free phenolic group. Functionalization of the hyperlipidemia treatment drugs bezafibrate and gemfibrozil afforded novel derivatives 4x and 4y in 79% and 84% yield. Finally, derivatization of complex triterpenoid structures bearing multiple functionalities, e.g., free alcohols, a carbonyl, and an activated alkene moiety, led to desired compound 4z and 4aa in respectively 56% and 82% yield.

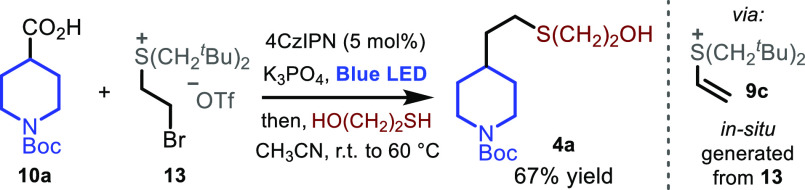

Delighted by the wide scope of application of this methodology, we questioned whether the use of bromo-sulfonium structure 13 (Scheme 3), a synthetic intermediate in-route to vinyl sulfonium 9c, would undergo the desired reactivity via in situ generation of the corresponding vinyl system, further streamlining the chemistry. Pleasingly, upon subjecting 13 to our reaction conditions, final compound 4a was isolated in 67% yield, confirming the feasibility of this approach.

Scheme 3. In Situ Generation of the Vinyl Sulfonium.

Reaction performed in a 0.2 mmol scale, using 10a (1 equiv), 13 (1.5 equiv), 4CzIPN (5 mol %) and mercaptoethanol (2.5 equiv); see Supporting Information for details.

By allowing practical access to products that would be the result of the forbidden reaction between nucleophilic alkyl radicals and electron-rich double bonds, this methodology formally redefines the scope of the classic addition of carbon-centered radicals to double bonds. We anticipate that this novel reactivity platform will stimulate considerable advances in various areas of synthesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank the EPSRC for funding (New Investigator Award EP/V006401/1 to M.S.). M.S. thanks the University of Nottingham and the Green Chemicals Beacon of Excellence for a Nottingham Research Fellowship. D.F. thanks the School of Chemistry, University of Nottingham, for a doctoral studentship. We thank Profs. R. Denton and P. Melchiorre for stimulating discussions and Prof. H. W. Lam for providing a sample of morphine used during the scope investigation of the methodology.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.2c12699.

Spectral data for all compounds, additional experimental details, materials, methods, including photographs of experimental setup (PDF)

Author Contributions

† S.P. and D.F. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Giese B. Formation of CC Bonds by Addition of Free Radicals to Alkenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1983, 22, 753–764. 10.1002/anie.198307531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Encyclopedia of Radicals in Chemistry, Biology and Materials; Studer A., Chatgilialoglu C., Eds.; Wiley, 2012. [Google Scholar]; b Subramanian H.; Landais Y.; Sibi M. P.Radical Addition Reactions. In Comprehensive Organic Synthesis, 2nd ed.; Knochel P., Ed.; Elsevier, 2014; Vol. 4, pp 699–741. [Google Scholar]; c Srikanth G. S. C.; Castle S. L. Advances in Radical Conjugate Additions. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 10377–10441. 10.1016/j.tet.2005.07.077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Streuff J.; Gansäuer A. Metal-Catalyzed β-Functionalization of Michael Acceptors through Reductive Radical Addition Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 14232–14242. 10.1002/anie.201505231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Curran D. P.; Porter N. A.; Giese B.. Stereochemistry of Radical Reactions; VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]; b Sibi M. P.; Ji J. Practical and Efficient Enantioselective Conjugate Radical Additions. J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 3800–3801. 10.1021/jo970558y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Sibi M. P.; Porter N. A. Enantioselective Free Radical Reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 1999, 32, 163–171. 10.1021/ar9600547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Sibi M. P.; Manyem S.; Zimmerman J. Enantioselective Radical Processes. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 3263–3296. 10.1021/cr020044l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Bar G.; Parsons A. F. Stereoselective Radical Reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2003, 32, 251–263. 10.1039/b111414j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Jasperse C. P.; Curran D. P.; Fevig T. L. Radical Reactions in Natural Product Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 1991, 91, 1237–1286. 10.1021/cr00006a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Pitre S. P.; Weires N. A.; Overman L. E. Forging C(Sp3)–C(Sp3) Bonds with Carbon-Centered Radicals in the Synthesis of Complex Molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 2800–2813. 10.1021/jacs.8b11790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Nicholls T. P.; Leonori D.; Bissember A. C. Applications of Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis to the Synthesis of Natural Products and Related Compounds. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2016, 33, 1248–1254. 10.1039/C6NP00070C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Nicewicz D. A.; MacMillan D. W. C. Merging Photoredox Catalysis with Organocatalysis: the Direct Asymmetric Alkylation of Aldehydes. Science 2008, 322, 77–80. 10.1126/science.1161976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ischay M. A.; Anzovino M. E.; Du J.; Yoon T. P. Efficient Visible Light Photocatalysis of [2 + 2] Enone Cycloadditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 12886–12887. 10.1021/ja805387f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Narayanam J. M. R.; Tucker J. W.; Stephenson C. R. J. Electron-Transfer Photoredox Catalysis: Development of a Tin-Free Reductive Dehalogenation Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 8756–8757. 10.1021/ja9033582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For reviews:; a Prier C. K.; Rankic D. A.; MacMillan D. W. C. Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis with Transition Metal Complexes: Applications in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5322–5363. 10.1021/cr300503r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Shaw M. H.; Twilton J.; MacMillan D. W. C. Photoredox Catalysis in Organic Chemistry. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 6898–6926. 10.1021/acs.joc.6b01449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Goddard J.-P.; Ollivier C.; Fensterbank L. Photoredox Catalysis for the Generation of Carbon Centered Radicals. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 1924–1936. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Staveness D.; Bosque I.; Stephenson C. R. J. Free Radical Chemistry Enabled by Visible Light-Induced Electron Transfer. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 2295–2396. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Romero N. A.; Nicewicz D. A. Organic Photoredox Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 10075–10166. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Yan M.; Kawamata Y.; Baran P. S. Synthetic Organic Electrochemical Methods Since 2000: On the Verge of a Renaissance. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 13230–13319. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zhu C.; Ang N. W. J.; Meyer T. H.; Qiu Y.; Ackermann L. Organic Electrochemistry: Molecular Syntheses with Potential. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 415–431. 10.1021/acscentsci.0c01532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Pollok D.; Waldvogel S. R. Electro-Organic Synthesis – a 21st Century Technique. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 12386–12400. 10.1039/D0SC01848A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected reviews:; a Kyne S. H.; Lefèvre G.; Ollivier C.; Petit M.; Ramis Cladera V.-A.; Fensterbank L. Iron and Cobalt Catalysis: New Perspectives in Synthetic Radical Chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 8501–8542. 10.1039/D0CS00969E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Fu G. C. Transition-Metal Catalysis of Nucleophilic Substitution Reactions: A Radical Alternative to SN1 and SN2 Processes. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 692–700. 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Fürstner A. Iron Catalysis in Organic Synthesis: A Critical Assessment of What It Takes To Make This Base Metal a Multitasking Champion. ACS Cent. Sci. 2016, 2, 778–789. 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Tasker S. Z.; Standley E. A.; Jamison T. F. Recent Advances in Homogeneous Nickel Catalysis. Nature 2014, 509, 299–309. 10.1038/nature13274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Photoredox catalysis:Gant Kanegusuku A. L.; Roizen J. L. Recent Advances in Photoredox-Mediated Radical Conjugate Addition Reactions: An Expanding Toolkit for the Giese Reaction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 21116–21149. 10.1002/anie.202016666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selected examples via electrochemical methods:; a Li D.; Ma T.-K.; Scott R. J.; Wilden J. D. Electrochemical Radical Reactions of Alkyl Iodides: A Highly Efficient, Clean, Green Alternative to Tin Reagents. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 5333–5338. 10.1039/D0SC01694B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Chen X.; Luo X.; Peng X.; Guo J.; Zai J.; Wang P. Catalyst-Free Decarboxylation of Carboxylic Acids and Deoxygenation of Alcohols by Electro-Induced Radical Formation. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 3226–3230. 10.1002/chem.201905224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Significant examples via earth abundant metal catalysis:; a Lo J. C.; Gui J.; Yabe Y.; Pan C.-M.; Baran P. S. Functionalized Olefin Cross-Coupling to Construct Carbon-Carbon Bonds. Nature 2014, 516, 343–348. 10.1038/nature14006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lo J. C.; Kim D.; Pan C.-M.; Edwards J. T.; Yabe Y.; Gui J.; Qin T.; Gutiérrez S.; Giacoboni J.; Smith M. W.; Holland P. L.; Baran P. S. Fe-Catalyzed C–C Bond Construction from Olefins via Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 2484–2503. 10.1021/jacs.6b13155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Qin T.; Malins L. R.; Edwards J. T.; Merchant R. R.; Novak A. J. E.; Zhong J. Z.; Mills R. B.; Yan M.; Yuan C.; Eastgate M. D.; Baran P. S. Nickel-Catalyzed Barton Decarboxylation and Giese Reactions: A Practical Take on Classic Transforms. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 260–265. 10.1002/anie.201609662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Mondal S.; Dumur F.; Gigmes D.; Sibi M. P.; Bertrand M. P.; Nechab M. Enantioselective Radical Reactions Using Chiral Catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 5842–5976. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Nagib D. A. Asymmetric Catalysis in Radical Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 15989–15992. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.2c00622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Silvi M.; Melchiorre P. Enhancing the Potential of Enantioselective Organocatalysis with Light. Nature 2018, 554, 41–49. 10.1038/nature25175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Brimioulle R.; Lenhart D.; Maturi M. M.; Bach T. Enantioselective Catalysis of Photochemical Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 3872–3890. 10.1002/anie.201411409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Meggers E. Asymmetric Catalysis Activated by Visible Light. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 3290–3301. 10.1039/C4CC09268F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Fleming I.Radical Reactions. In Molecular Orbitals and Organic Chemical Reactions, Student Edition; Wiley: Chichester, United Kingdom, 2009; pp 275–297. [Google Scholar]; b Parsaee F.; Senarathna M. C.; Kannangara P. B.; Alexander S. N.; Arche P. D. E.; Welin E. R. Radical Philicity and Its Role in Selective Organic Transformations. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2021, 5, 486–499. 10.1038/s41570-021-00284-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q.; Suravarapu S. R.; Renaud P. A Giese Reaction for Electron-Rich Alkenes. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 2225–2230. 10.1039/D0SC06341J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Paul V.; Roberts B. P. Polarity Reversal Catalysis of Hydrogen Atom Abstraction Reactions. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1987, 1322–1324. 10.1039/c39870001322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Roberts B. P. Polarity-Reversal Catalysis of Hydrogen-Atom Abstraction Reactions: Concepts and Applications in Organic Chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1999, 28, 25–35. 10.1039/a804291h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Blauer G.; Shenblat M.; Katchalsky A. Polymerization of Vinyl Bromide in Solution. J. Polym. Sci. 1959, 38, 189–204. 10.1002/pol.1959.1203813316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Enomoto S. Polymerization of Vinyl Chloride. J. Polym. Sci. Part A-1 Polym. Chem. 1969, 7, 1255–1267. 10.1002/pol.1969.150070506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Barton D. H. R.; Togo H.; Zard S. Z. Radical Addition to Vinyl Sulphones and Vinyl Phosphonium Salts. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985, 26, 6349–6352. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)84596-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Barton D. H. R.; Boivin J.; Crépon E.; Sarma J.; Togo H.; Zaid S. Z. Decarboxylative Radical Addition to Vinylsulphones and Vinylphosphonium Bromide: Some Further Novel Transformations of Geminal (Pyridine-2-Thiyl) Phenylsulphones. Tetrahedron 1991, 47, 7091–7108. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)96163-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Filippini D.; Silvi M. Visible Light-Driven Conjunctive Olefination. Nat. Chem. 2022, 14, 66–70. 10.1038/s41557-021-00807-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Filippini D.; Silvi M. The Conceptual Development of a Conjunctive Olefination. Synlett 2022, 33, 1011–1016. 10.1055/a-1787-1159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Gosselck J.; Béress L.; Schenk H. Reactions of Substituted Vinylsulfonium Salts with CH-Acidic Compounds. – A New Route to Polysubstituted Cyclopropanes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1966, 5, 596–597. 10.1002/anie.196605962. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Unthank M. G.; Hussain N.; Aggarwal V. K. The Use of Vinyl Sulfonium Salts in the Stereocontrolled Asymmetric Synthesis of Epoxide- and Aziridine-Fused Heterocycles: Application to the Synthesis of (−)-Balanol. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 7066–7069. 10.1002/anie.200602782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Mondal M.; Chen S.; Kerrigan N. J. Recent Developments in Vinylsulfonium and Vinylsulfoxonium Salt Chemistry. Molecules 2018, 23, 738. 10.3390/molecules23040738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Juliá F.; Yan J.; Paulus F.; Ritter T. Vinyl Thianthrenium Tetrafluoroborate: A Practical and Versatile Vinylating Reagent Made from Ethylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 12992–12998. 10.1021/jacs.1c06632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Corey E. J.; Chaykovsky M. Dimethyloxosulfonium Methylide ((CH3)2SOCH2) and Dimethylsulfonium Methylide ((CH3)2SCH2). Formation and Application to Organic Synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87, 1353–1364. 10.1021/ja01084a034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; For a comparative study of the leaving group abilities of onium ions:; b Aggarwal V. K.; Harvey J. N.; Robiette R. On the Importance of Leaving Group Ability in Reactions of Ammonium, Oxonium, Phosphonium, and Sulfonium Ylides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 5468–5471. 10.1002/anie.200501526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Umemura K.; Matsuyama H.; Kamigata N. Alkylation of Several Nucleophiles with Alkylsulfonium Salts. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1990, 63, 2593–2600. 10.1246/bcsj.63.2593. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Kozhushkov S. I.; Alcarazo M. Synthetic Applications of Sulfonium Salts. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 2020, 2486–2500. 10.1002/ejic.202000249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Holst D. E.; Wang D. J.; Kim M. J.; Guzei I. A.; Wickens Z. K. Aziridine Synthesis by Coupling Amines and Alkenes via an Electrogenerated Dication. Nature 2021, 596, 74–79. 10.1038/s41586-021-03717-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Wang D. J.; Targos K.; Wickens Z. K. Electrochemical Synthesis of Allylic Amines from Terminal Alkenes and Secondary Amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 21503–21510. 10.1021/jacs.1c11763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Chu L.; Ohta C.; Zuo Z.; MacMillan D. W. C. Carboxylic Acids as A Traceless Activation Group for Conjugate Additions: A Three-Step Synthesis of (±)-Pregabalin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 10886–10889. 10.1021/ja505964r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Jin Y.; Fu H. Visible-Light Photoredox Decarboxylative Couplings. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2017, 6, 368–385. 10.1002/ajoc.201600513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Schwarz J.; König B. Decarboxylative Reactions with and without Light – a Comparison. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 323–361. 10.1039/C7GC02949G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hansch C.; Leo A.; Taft R. W. A Survey of Hammett Substituent Constants and Resonance and Field Parameters. Chem. Rev. 1991, 91, 165–195. 10.1021/cr00002a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.-L.; Yang L.; Wu J.; Zhu C.; Wang P. Vinyl Sulfonium Salts as the Radical Acceptor for Metal-Free Decarboxylative Alkenylation. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 7768–7772. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c03074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang T.-Y.; Lu L.-H.; Cao Z.; Liu Y.; He W.-M.; Yu B. Recent Advances of 1,2,3,5-Tetrakis(Carbazol-9-Yl)-4,6-Dicyanobenzene (4CzIPN) in Photocatalytic Transformations. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 5408–5419. 10.1039/C9CC01047E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Zhang W.; Colandrea V. J.; Jimenez L. S. Reactivity and Rearrangements of Dialkyl- and Diarylvinylsulfonium Salts with Indole-2- and Pyrrole-2-Carboxaldehydes. Tetrahedron 1999, 55, 10659–10672. 10.1016/S0040-4020(99)00605-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Péter Á.; Perry G. J. P.; Procter D. J. Radical C–C Bond Formation Using Sulfonium Salts and Light. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2020, 362, 2135–2142. 10.1002/adsc.202000220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Dewanji A.; van Dalsen L.; Rossi-Ashton J. A.; Gasson E.; Crisenza G. E. M.; Procter D. J. A General Arene C–H Functionalization Strategy via Electron Donor–Acceptor Complex Photoactivation. Nat. Chem. 2023, 15, 43–52. 10.1038/s41557-022-01092-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speckmeier E.; Fischer T. G.; Zeitler K. A Toolbox Approach To Construct Broadly Applicable Metal-Free Catalysts for Photoredox Chemistry: Deliberate Tuning of Redox Potentials and Importance of Halogens in Donor–Acceptor Cyanoarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 15353–15365. 10.1021/jacs.8b08933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.