Abstract

Bioorthogonal metallocatalysis has opened up a xenobiotic route to perform nonenzymatic catalytic transformations in living settings. Despite their promising features, most metals are deactivated inside cells by a myriad of reactive biomolecules, including biogenic thiols, thereby limiting the catalytic functioning of these abiotic reagents. Here we report the development of cytocompatible alloyed AuPd nanoparticles with the capacity to elicit bioorthogonal depropargylations with high efficiency in biological media. We also show that the intracellular catalytic performance of these nanoalloys is significantly enhanced by protecting them following two different encapsulation methods. Encapsulation in mesoporous silica nanorods resulted in augmented catalyst reactivity, whereas the use of a biodegradable PLGA matrix increased nanoalloy delivery across the cell membrane. The functional potential of encapsulated AuPd was demonstrated by releasing the potent chemotherapy drug paclitaxel inside cancer cells. Nanoalloy encapsulation provides a novel methodology to develop nanoreactors capable of mediating new-to-life reactions in cells.

Keywords: palladium, gold, nanoalloys, catalysis, bioorthogonal, nanoencapsulation

In the early 2010s, the paths of bioorthogonal chemistry and nanotechnology crossed at the very center of the periodic table of elements,1,2 sparking the emergence of transition-metal catalysts (TMCs) as bioorthogonal nanotools.3,4 Over a decade later, numerous biocompatible TMC-based strategies with different features and functions have been developed for various biomedical applications, including de novo enzyme design,5,6 labeling/uncaging of biomolecules,7,8 or the release of metal-activated probes and therapeutics.9,10 Organometallic complexes,11−15 artificial metalloproteins,5,6,16,17 nanozymes and MOFs,18−27 metal-loaded exosomes and macrophages,28−30 and soft and hard micro/millidevices functionalized with metal nanoparticles (NPs)10,31−36 are representative examples of the wide diversity of catalytic systems reported to date.

The size and nature of the ligands or scaffolds bound to the metal atoms or NPs will dictate whether these nanoreactors are to exert their function in the extracellular or intracellular space, with each environment facing different conditions. While the interstitial liquid is mostly composed of water (up to 95%), intracellular bioorthogonal catalysis is severely restricted by biomolecule crowding (>20% protein by weight37) and the reductive environment of the cell cytoplasm. Under such stringent conditions, most TMCs are poisoned in relatively short periods of time. For this reason, technologies that protect abiotic metals from thiol-rich biomolecules and other reactive species and, at the same time, facilitate access of the substrate to metal active sites are in demand to overcome this issue.

A number of research laboratories have investigated the use of different TMCs (including noble metals such as Ru, Pd, Au, and Pt) and reactions (e.g., dealkylations, cross-couplings, cycloadditions, and ring-closure metathesis) in cells and organisms with the aim of expanding the chemical toolbox for bioorthogonal metallocatalysis. Depropargylations are one such reactions. O- and N-propargyl groups have been extensively used as a masking strategy in chemical biology and medicinal chemistry to render bioactive agents inactive, while activatable by abiotic metal catalysis.10,21,28,32−35,38−44 Because of the lack of natural “depropargylases”, this strategy offers superb control over bioorthogonal dissociative processes, enabling selective uncaging of drugs exclusively in the presence of a metal activator, even in vivo.21,34,44Pd and Au NPs stand out among the metallic nanocatalysts that catalyze depropargylation reactions. Interestingly, there has been an oversight of the reactivity of alloys of these or other noble metals so far. Encouraged by the potential benefits offered by alloyed nanomaterials,45 we embarked on a systematic study to investigate the capacity of a range of single-metal NPs and alloys to uncage a propargyl-masked prodye (PocRho)10 under physiological conditions.

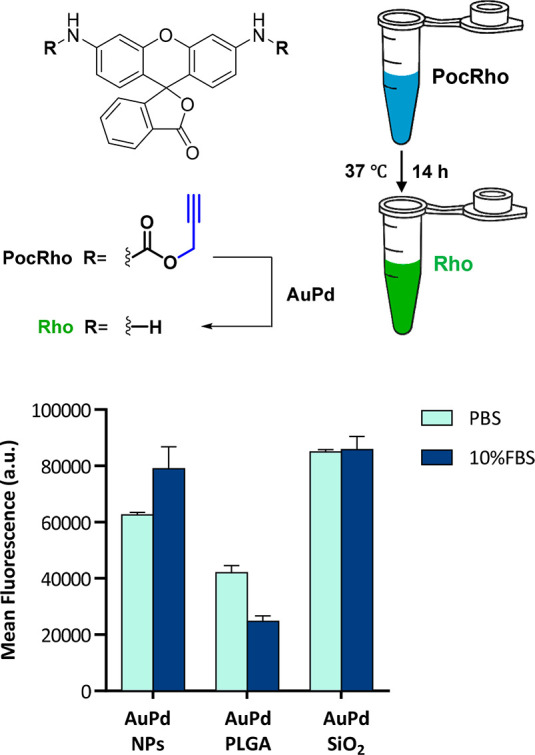

Single-metal NPs of Pd, Au, Pt, and Ru and their corresponding bimetallic alloys were manufactured in a single step using tetrakis(hydroxymethyl)-phosphonium chloride as a simultaneous reducing agent and stabilizing ligand.46−48 (See the full experimental details in the Supporting Information.) NPs were then incubated with PocRho, a bis-propargyloxycarbonyl-protected prodye that releases green fluorescent rhodamine 110 (Rho) upon double depropargylation.21 Reactions were run at 37 °C in PBS in the absence and presence of serum to determine which metallic NPs were compatible not only with physiological media but also with supplements required in cell culture. An analysis of fluorescence intensity was carried out using a spectrofluorometer (PerkinElmer EnVision, λex/em 480/535 nm). As shown in Figure 1a, single-metal Pd NPs and Pd-containing nanoalloys exhibited superior capabilities to uncage Rho, highlighting the performance of AuPd in serum-containing media. (See the kinetics study for best-performing NPs in Figure S1, Supporting Information.) Next, we tested the tolerability of human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells to treatment with the most catalytic NPs identified in the fluorogenic study. Notably, AuPd nanoalloys induced no change in cell viability at any of the concentrations tested, whereas the rest of the NPs displayed variable levels of toxicity at 20 μg/mL (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

(a) Analysis of the conversion of nonfluorescent PocRho (100 μM) to fluorescent Rho after incubation with single-metal or alloyed NPs (20 μg metal/mL) in PBS and 10% FBS in PBS for 14 h. The fluorescence was measured at λex/em 480/535 nm. Error bars: ±SD, n = 3. (b) A549 cell viability study after treatment with Pd, PdPt, PdRu, and AuPd NPs over a range of concentrations. Cell viability measured at day 5 using PrestoBlue reagent. Error bars: ±SD, n = 3. (c) Representative TEM (left) and HAADF-STEM (right) images of AuPd PLGA at different magnifications. (d) Elemental analysis of an AuPd NP embedded in PLGA by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). Analysis was carried out in the marked area of the HAADF-STEM image. (e) Representative TEM (left) and HAADF-STEM (right) images of AuPd SiO2 at different magnifications. (f) Schematic display of a SiO2 scaffold decorated with AuPd NPs and elemental mapping analysis of an AuPd NP by STEM-EDS (scanning mode).

Encouraged by the catalytic properties and tolerability of AuPd, we performed a preliminary in cellulo study to test the bioorthogonal reactivity of the NPs in A549 cells. Disappointingly, cancer cells pretreated with AuPd were not able to convert an inactive precursor of paclitaxel into its toxic form, indicating that these NPs are either unable to enter cells or rapidly deactivated in the cell cytoplasm. The latter is not surprising as metallic Au has a high affinity for thiol groups,32 which are ubiquitous in proteins and can bind to Au surfaces, sterically hindering the access of the substrate to the catalytic sites. Consequently, we decided to investigate different nanoencapsulation methods with the aim of enhancing nanoalloy delivery and protecting the metal NPs from direct contact with thiol-rich biomolecules in the crowded cell cytoplasm. Two kinds of materials were tested to encapsulate AuPd: poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and mesoporous silica nanorods (SiO2). Direct encapsulation of preformed AuPd NPs in the PLGA emulsion results in an inconsistent nanoalloy load distribution,49 making this method inadequate for our goals. Therefore, AuPd-PLGA was prepared by the water/oil/water emulsion and solvent evaporation method using a new methodology inspired by a recently reported procedure designed to produce Pd nanosheets in situ in PLGA.50 (See Figure S2 and experimental details in the Supporting Information.) Images from transmission electron microscopy (TEM and HAADF-STEM) clearly show 2 to 3 nm AuPd NPs embedded inside PLGA nanodrops of approximately 100 nm in diameter (Figure 1c,d and Figure S3). As shown in Figure 1c, the AuPd NPs were selectively loaded in each nanomatrix of PLGA, which is evidence of the efficiency of the loading method. Elemental analysis confirmed the alloyed composition of the AuPd NPs (Figure 1d), which demonstrates the versatility of the in situ approach to yield not only single-metal NPs48 but also AuPd nanoalloys, being the first procedure that facilitates the crystallization of alloyed NPs in double emulsions of PLGA. On the other hand, ordered mesoporous SiO2 nanorods were prepared according to previously reported procedures,52,53 followed by amine-grafting with 3-aminopropyl-triethoxysilane and loading of preformed AuPd NPs. (See full experimental details in the Supporting Information.) TEM and elemental analysis show AuPd NPs embedded within the mesoporous nanorods (Figure 1e,f and Figures S4–S6). The contents of Au and Pd in the nanoencapulated NPs were measured by microwave plasma atomic emission spectrometer (MP-AES) to enable comparative studies using equivalent bimetal concentrations.

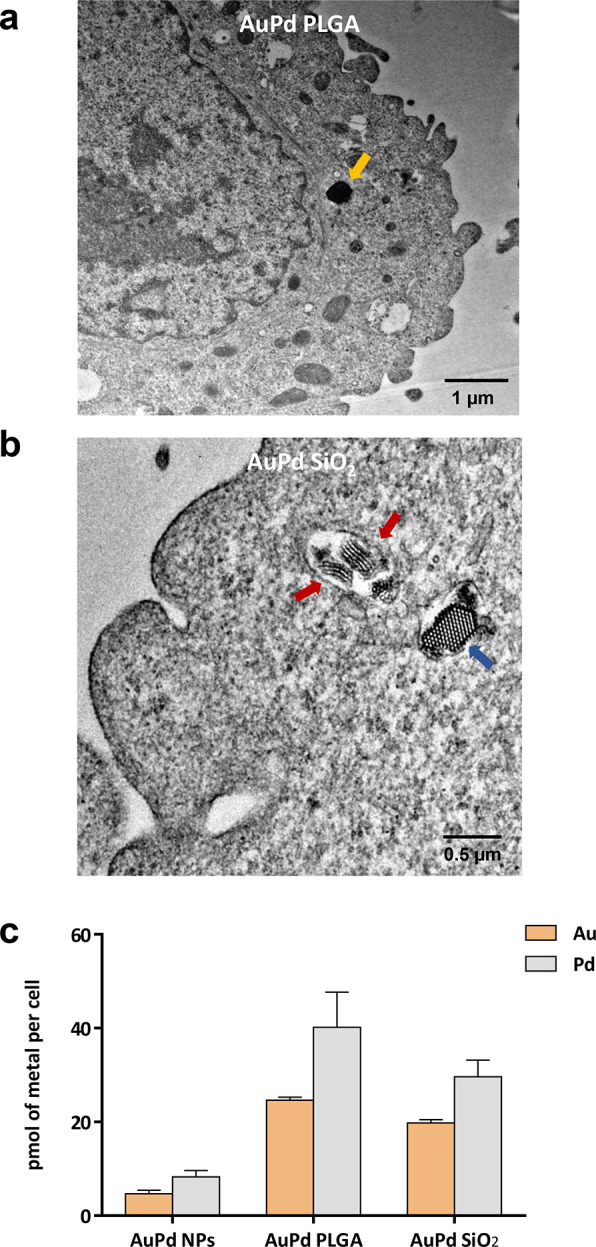

The PocRho fluorogenic test was then used to compare the catalytic efficacy of uncoated AuPd NPs versus nanoencapsulated AuPd at 37 °C in PBS with and without serum. Analysis revealed that AuPd SiO2 mediated the highest fluorescence signal, being superior to uncoated AuPd nanoalloys (Figure 2). This may be associated with the homogeneous dispersion of AuPd NPs throughout the pore channels of the scaffold.51 In contrast, AuPd PLGA demonstrated a significantly lower depropargylation capacity at equal metal concentrations. Subsequently, we studied the capacity of each of the materials to deliver AuPd into A549 cells. Two methods were used to study nanoalloy transcellular delivery: TEM, to visualize the metal presence in the cell cytoplasm, and inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-OES), for quantitative metal content analysis. Cells were treated with nanoencapsulated AuPd NPs for 30 min. After the media containing NPs were removed and the adhered cells were washed twice with PBS, cells were detached by trypsinization and centrifuged to further eliminate extracellular NPs by discarding the supernatant. Cells were then incubated on a coverslip for an additional 24 h, fixed (paraformaldehyde), and processed for TEM analysis. Rather than being adsorbed on the cell membrane, images verified the presence of AuPd PLGA and AuPd SiO2 in the cytoplasm of A549 cells, which appeared as separate NPs of various sizes across the cell cytoplasm (Figure 3a,b; see additional images in Figure S7, Supporting Information). On the other hand, an intracellular metal content study was carried out by incubating A549 cells with freestanding AuPd NPs, AuPd PLGA, and AuPd SiO2 (20 μg/mL of metal content), followed by the same procedure described above to remove extracellular NPs and thus ensure that only internalized nanoalloys were measured. Cell pellets were digested (10% HNO3) and analyzed by ICP-OES. As shown in Figure 3c, the content of Au and Pd in cells treated with uncoated AuPd was relatively low, which may in part explain the lack of capacity of these NPs to activate prodrugs inside cells. Notably, encapsulated AuPd achieved far superior intracellular delivery, highlighting the performance of AuPd PLGA, whose capacity to deliver the nanoalloys into A549 cells was approximately 25% higher than that of AuPd SiO2. As expected, the Au/Pd content ratio remained constant for the three nanocomposites.

Figure 2.

Analysis of the conversion of PocRho (100 μM) into Rho after incubation with naked AuPd NPs, AuPd PLGA, and AuPd SiO2 (20 μg metal/mL) in PBS and 10% FBS in PBS for 14 h. Fluorescence was measured at λex/em 480/535 nm. Error bars: ±SD, n = 3.

Figure 3.

Nanoalloy internalization studies in lung cancer A549 cells. (a) Representative TEM image of the ultrathin cross-section of a cell treated with AuPd PLGA, showing the membrane and the cytoplasm. A NP is indicated with an orange arrow. Scale bar = 1 μm. (b) Representative TEM image of the ultrathin cross-section of a cell treated with AuPd SiO2, showing the membrane and the cytoplasm. Two laterally imaged NPs are indicated with red arrows. A transversally imaged NP is indicated with a blue arrow. Scale bar = 0.5 μm. (c) Quantification of Au and Pd content inside the cell (pmol of metal/cell). Analysis performed by ICP-OES. Error bars: ±SD, n = 3.

Encouraged by the improved catalytic properties of AuPd SiO2 in biological media and the superior transcellular carrier abilities of AuPd PLGA, an intracellular prodrug activation study was performed using the inactive chemotherapy precursor Pro-PTX (Figure 4a), which upon a single depropargylation reaction triggers a self-immolation cascade that releases highly toxic PTX (mechanism described in a previous work35). A549 cells were preincubated with either freestanding or encapsulated AuPd NPs (20 μg of metal/mL) for 30 min and then washed twice with PBS to eliminate extracellular nanoalloys. Vehicle (0.1% v/v DMSO) or Pro-PTX (1 μM) was added to the cells and incubated for 5 days. Cell viability was measured using the PrestoBlue assay. PTX (1 μM) treatment and untreated cells (0.1% v/v DMSO) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Cells treated with Pro-PTX (1 μM) in the absence of AuPd NPs were used as an additional negative control. As shown in Figure 4b, A549 cell proliferation was unaffected by treatment with either Pro-PTX or the AuPd nanoalloys. In contrast, the incubation of Pro-PTX with cells pretreated with encapsulated AuPd elicited highly potent inhibition of cancer cell proliferation, showing anticancer activity comparable to the direct treatment with PTX. Remarkably, the intracellular drug uncaging capacities of both encapsulation methods were essentially equivalent. This indicates that the superior delivery properties of AuPd PLGA compensates for its lower catalytic properties relative to those of AuPd SiO2. Of note, incubation of Pro-PTX with cells pretreated with “naked” AuPd NPs did not show any reduction of cell viability, in agreement with their reduced cellular internalization (as shown in Figure 3c). This study demonstrates that the encapsulation of metal nanoalloys can serve to improve both catalytic and cell delivery properties, thereby enabling the performance of intracellular bioorthogonal reactions.

Figure 4.

(a) AuPd-mediated conversion of Pro-PTX to PTX. (b) Intracellular prodrug activation assay in A549 lung cancer cells. Cells were treated with uncoated and encapsulated AuPd for 30 min prior to prodrug addition. Cell viability was measured at day 5. Experiments: 0.1% DMSO (untreated control); AuPd (20 μg metal/mL, −ve control); Pro-PTX (1 μM, −ve control); PTX (1 μM, +ve control); and AuPd + 1 μM Pro-PTX (activation assays). Error bars: ±SD, n = 3. Significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA): ***P < 0.001. (c) Immunofluorescence study of the microtubule distribution in A549 cells labeled with AuPd PLGA or AuPd SiO2 and treated with Pro-PTX (1 μM). Cells were incubated with encapsulated AuPd for 30 min prior to prodrug addition. Negative controls: Pro-PTX (1 μM), AuPd PLGA, and AuPd SiO2. Positive control: PTX (1 μM). 48 h after treatment, cells were fixed and stained for microtubules (green), actin filaments (red), and cell nuclei (blue). The panel shows the merged image of the three channels as maximal projections. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Finally, to validate that the combined treatment of encapsulated AuPd NPs and Pro-PTX results in the same antiproliferative mode of action as for the parent drug PTX, we studied microtubule stabilization by immunofluorescence.54 Cells were treated as previously described; fixed after 2 days of treatment; incubated with DAPI (cell nuclei stain), anti-α-tubulin IgG (for microtubules), and TRITC-phalloidin (for actin filaments); and imaged by confocal microscopy (Olympus FV1000). As shown in Figure 4c, negative controls did not induce changes in cell morphology. In contrast, treating A549 cells with PTX led to microtubule accumulation (green channel), round-shaped cells, and fragmented nuclei (independent channel images are shown in Figure S8, Supporting Information). Notably, equivalent morphological changes were observed in cells treated with both Pro-PTX and encapsulated AuPd NPs, evidence that the anticancer effect mediated by these combinations is the result of the intracellular generation of PTX.

In conclusion, we have studied the capacity of noble metal NPs (Pd, Au, Pt, and Ru, and their corresponding bimetallic alloys) to mediate depropargylation reactions in biological media and discovered that AuPd nanoalloys display superior catalytic properties and tolerability compared to any other single-metal or alloyed NP tested in this work. The enhanced catalysis elicited by alloyed AuPd NPs is likely a consequence of a combination of factors, including geometric and electronic effects on the NP surface55 and the fact that each metal mediates depropargylation reactions by different but complementary mechanisms.32,38 Regrettably, these bimetallic NPs show negligible bioorthogonal reactivity inside cells. To improve their in cellulo performance, we investigated two nanoencapsulation methods, both of which successfully enabled AuPd-mediated intracellular uncaging of the clinically approved drug PTX. Notably, each material promoted AuPd catalysis by different means: nondegradable mesoporous silica nanorods augmented the catalytic performance of the nanoalloys, whereas biodegradable PLGA matrixes enhanced transcellular NP delivery. By protecting AuPd NPs with scaffolds with distinct features, this investigation provides a novel and versatile strategy for protecting metal NPs and performing intracellular biorthogonal catalysis toward different applications, including the selective uncaging of probes and drugs inside cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank the confocal microscopy facilities of the IGC for helping with the experiments [CIBER-BBN (initiative funded by the VI National R&D&i Plan 2008–2011, Iniciativa Ingenio 2010, Consolider Program, CIBER Actions and financed by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III with assistance from the European Regional Development Fund]. The synthesis of materials has been performed by the Platform of Production of Biomaterials and Nanoparticles of the NANBIOSIS ICTS, more specifically by the Nanoparticle Synthesis Unit of the CIBER in BioEngineering, Biomaterials & Nanomedicine (CIBER-BBN). ELECMI (LMA-UNIZAR) ICTS is also gratefully acknowledged.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- EDS

energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy

- HAADF-STEM

high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy

- ICP-OES

inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- MP-AES

microwave plasma atomic emission spectrometer

- MS

mass spectrometry

- NP

nanoparticle

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PLGA

poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid

- ppm

parts per million

- r.t.

room temperature

- SD

standard deviation

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- TMC

transition-metal catalyst

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.nanolett.2c03593.

Preparation and characterization of NPs, prodye, and prodrug; methods and experimental procedures; biological assays; and Figures S1–S8 (PDF)

Author Contributions

• B.R.-R., A.M.P.-L., and L.U. made equal contributions.

We thank EPSRC (Healthcare Technology Challenge Award, no. EP/N021134/1) and ERC (Advanced Grant CADENCE, no. ERC-2016-ADG-742684) for funding. B.R.-R., M.C.O.-L., and T.V. thanks the EC for MSC fellowships (H2020-MSCA-IF-2014-658833, H2020-MSCA-IF-2018-841990, H2020-MSCA-IF-2016-749299, and H2020-MSCA-IF-2019-895664, respectively). V.S. acknowledges the financial support of Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades, Programa Retos Investigación, Proyecto REF: RTI2018-099019-A-I00.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Yusop R. M.; Unciti-Broceta A.; Johansson E. M. V.; Sánchez-Martín R. M.; Bradley M. Palladium-mediated intracellular chemistry. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 239–243. 10.1038/nchem.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unciti-Broceta A.; Johansson E. M. V.; Yusop R. M.; Sánchez-Martín R. M.; Bradley M. Synthesis of polystyrene microspheres and functionalization with Pd(0) nanoparticles to perform bioorthogonal organometallic chemistry in living cells. Nat. Protocols 2012, 7, 1207–1218. 10.1038/nprot.2012.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de L’Isle M. O. N.; Ortega-Liebana M. C.; Unciti-Broceta A. Transition metal catalysts for the bioorthogonal synthesis of bioactive agents. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2021, 61, 32–42. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatino V.; Unnikrishnan V. B.; Bernardes G. J. L. Transition metal mediated bioorthogonal release. Chem. Catal 2022, 2, 39–51. 10.1016/j.checat.2021.12.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeschek M.; Reuter R.; Heinisch T.; Trindler C.; Klehr J.; Panke S.; Ward T. R. Directed evolution of artificial metalloenzymes for in vivo metathesis. Nature 2016, 537, 661–665. 10.1038/nature19114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubokura K.; Vong K. K.; Pradipta A. R.; Ogura A.; Urano S.; Tahara T.; Nozaki S.; Onoe H.; Nakao Y.; Sibgatullina R.; Kurbangalieva A.; Watanabe Y.; Tanaka K. In vivo gold complex catalysis within live mice. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 3579–3584. 10.1002/anie.201610273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicer C. D.; Triemer T.; Davis B. G. Palladium-mediated cell-surface labelling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 800–803. 10.1021/ja209352s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Yu J.; Zhao J.; Wang J.; Zheng S.; Lin S.; Chen L.; Yang M.; Jia S.; Zhang X.; Chen P. Palladium-triggered deprotection chemistry for protein activation in living cells. Nat. Chem. 2014, 6, 352–361. 10.1038/nchem.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez M. I.; Penas C.; Vázquez M. E.; Mascareñas J. L. Metal-catalyzed uncaging of DNA-binding agents in living cells. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 1901–1907. 10.1039/C3SC53317D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss J. T.; Dawson J. C.; Macleod K. G.; Rybski W.; Fraser C.; Torres-Sánchez C.; Patton E. E.; Bradley M.; Carragher N. O.; Unciti-Broceta A. Extracellular palladium-catalysed dealkylation of 5-fluoro-1-propargyl-uracil as a bioorthogonally activated prodrug approach. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3277. 10.1038/ncomms4277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Völker T.; Dempwolff F.; Graumann P. L.; Meggers E. Progress towards bioorthogonal catalysis with organometallic compounds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 10536–10540. 10.1002/anie.201404547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomás-Gamasa M.; Martínez-Calvo M.; Couceiro J. R.; Mascareñas J. L. Transition metal catalysis in the mitochondria of living cells. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12538. 10.1038/ncomms12538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Calvo M.; Couceiro J. R.; Destito P.; Rodríguez J.; Mosquera J.; Mascareñas J. L. Intracellular deprotection reactions mediated by palladium complexes equipped with designed phosphine ligands. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 6055–6061. 10.1021/acscatal.8b01606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal C.; Tomás-Gamasa M.; Destito P.; López F.; Mascareñas J. L. Concurrent and orthogonal gold(I) and ruthenium(II) catalysis inside living cells. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1913. 10.1038/s41467-018-04314-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel-Ávila J.; Tomás-Gamasa M.; Olmos A.; Pérez P. J.; Mascareñas J. L. Discrete Cu(I) complexes for azide–alkyne annulations of small molecules inside mammalian cells. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 1947–1952. 10.1039/C7SC04643J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto Y.; Kojima R.; Schwizer F.; Bartolami E.; Heinisch T.; Matile S.; Fussenegger M.; Ward T. R. A cell-penetrating artificial metalloenzyme regulates a gene switch in a designer mammalian cell. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1943. 10.1038/s41467-018-04440-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eda S.; Nasibullin I.; Vong K.; Kudo N.; Yoshida M.; Kurbangalieva A.; Tanaka K. Biocompatibility and therapeutic potential of glycosylated albumin artificial metalloenzymes. Nat. Catal. 2019, 2, 780–792. 10.1038/s41929-019-0317-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tonga G. Y.; Jeong Y.; Duncan B.; Mizuhara T.; Mout R.; Das R.; Kim S. T.; Yeh Y. C.; Yan B.; Hou S.; Rotello V. M. Supramolecular regulation of bioorthogonal catalysis in cells using nanoparticle-embedded transition metal catalysts. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 597–603. 10.1038/nchem.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y.; Feng X.; Xing H.; Xu Y.; Kim B. K.; Baig N.; Zhou T.; Gewirth A. A.; Lu Y.; Oldfield E.; Zimmerman S. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 11077–11080. 10.1021/jacs.6b04477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. A.; Askevold B.; Mikula H.; Kohler R. H.; Pirovich D.; Weissleder R. Nano-palladium is a cellular catalyst for in vivo chemistry. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15906. 10.1038/ncomms15906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoop M.; Ribeiro A. S.; Rösch D.; Weinand P.; Mendes N.; Mushtaq F.; Chen X.-Z.; Shen Y.; Pujante C. F.; Puigmartí-Luis J.; Paredes J.; Nelson B. J.; Pêgo A. P.; Pané S. Mobile magnetic nanocatalysts for bioorthogonal targeted cancer therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1705920. 10.1002/adfm.201705920. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Pujals S.; Stals P. J. M.; Paulöhrl T.; Presolski S. I.; Meijer E. W.; Albertazzi L.; Palmans A. R. A. Catalytically active single-chain polymeric nanoparticles: exploring their functions in complex biological media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 3423–3433. 10.1021/jacs.8b00122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F.; Zhang Y.; Du Z.; Ren J.; Qu X. Designed heterogeneous palladium catalysts for reversible light-controlled bioorthogonal catalysis in living cells. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1209. 10.1038/s41467-018-03617-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F. M.; Zhang Y.; Liu Z. W.; Du Z.; Zhang L.; Ren J. S.; Qu X. G. A Biocompatible heterogeneous MOF-Cu catalyst for in vivo drug synthesis in targeted subcellular organelles. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 6987–6992. 10.1002/anie.201901760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao-Milán R.; Gopalakrishnan S.; He L. D.; Huang R.; Wang Li-S.; Castellanos L.; Luther D. C.; Landis R. F.; Makabenta J. M. V.; Li C.-H.; Zhang X.; Scaletti F.; Vachet R. W.; Rotello V. M. Thermally gated bio-orthogonal nanozymes with supramolecularly confined porphyrin catalysts for antimicrobial uses. Chem. 2020, 6, 1113–1124. 10.1016/j.chempr.2020.01.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du Z.; Liu C.; Song H.; Scott P.; Liu Z.; Ren J.; Qu X. Neutrophil-membrane-directed bioorthogonal synthesis of inflammation-targeting chiral drugs. Chem. 2020, 6, 2060–2072. 10.1016/j.chempr.2020.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez R.; Carrillo-Carrión C.; Destito P.; Alvarez A.; Tomás-Gamasa M.; Pelaz B.; Lopez F.; Mascareñas J. L.; del Pino P. Core-Shell Palladium/MOF platforms as diffusion-controlled nanoreactors in living cells and tissue models. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2020, 1, 100076. 10.1016/j.xcrp.2020.100076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancho-Albero M.; Rubio-Ruiz B.; Pérez-López A. M.; Sebastián V.; Martín-Duque P.; Arruebo M.; Santamaría J.; Unciti-Broceta A. Cancer-derived exosomes loaded with ultrathin palladium nanosheets for targeted bioorthogonal catalysis. Nat. Catal. 2019, 2, 864–872. 10.1038/s41929-019-0333-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian V.; Sancho-Albero M.; Arruebo M.; Perez-Lopez A. M.; Rubio-Ruiz B.; Martin-Duque P.; Unciti-Broceta A.; Santamaria J. Nondestructive production of exosomes loaded with ultrathin palladium nanosheets for targeted bio-orthogonal catalysis. Nat. Protoc 2021, 16, 131–163. 10.1038/s41596-020-00406-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das R.; Hardie J.; Joshi B. P.; Zhang X.; Gupta A.; Luther D. C.; Fedeli S.; Farkas M. E.; Rotello V. M. Macrophage-encapsulated bioorthogonal nanozymes for targeting cancer cells. JACS Au 2022, 2, 1679–1685. 10.1021/jacsau.2c00247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavadetscher J.; Hoffmann S.; Lilienkampf A.; Mackay L.; Yusop R. M.; Rider S. A.; Mullins J. J.; Bradley M. Copper catalysis in living systems and in situ drug synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 15662–15666. 10.1002/anie.201609837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-López A. M.; Rubio-Ruiz B.; Sebastián V.; Hamilton L.; Adam C.; Bray T. L.; Irusta S.; Brennan P. M.; Lloyd-Jones G.; Sieger D.; Santamaría J.; Unciti-Broceta A. Gold-triggered uncaging chemistry in living systems. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 12548–12552. 10.1002/anie.201705609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray T. L.; Salji M.; Brombin A.; Pérez-López A. M.; Rubio-Ruiz B.; Galbraith L. C.A.; Patton E. E.; Leung H. Y.; Unciti-Broceta A. Bright insights into palladium-triggered local chemotherapy. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 7354–7361. 10.1039/C8SC02291G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Liebana M. C.; Porter N. J.; Adam C.; Valero T.; Hamilton L.; Sieger D.; Becker C. G.; Unciti-Broceta A. Truly-biocompatible gold catalysis enables vivo-orthogonal intra-CNS release of anxiolytics. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202111461 10.1002/anie.202111461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-López A. M.; Rubio-Ruiz B.; Valero T.; Contreras-Montoya R.; Álvarez de Cienfuegos L.; Sebastián V.; Santamaría J.; Unciti-Broceta A. Bioorthogonal uncaging of cytotoxic paclitaxel through Pd nanosheet–hydrogel frameworks. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 9650–9659. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. W.; Li H. J.; Bian Y. J.; Wang Z. J.; Chen G. J.; Zhang X. D.; Miao Y. M.; Wen D.; Wang J. Q.; Wan G.; Zeng Y.; Abdou P.; Fang J.; Li S.; Sun C. J.; Gu Z. Bioorthogonal catalytic patch. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 933–941. 10.1038/s41565-021-00910-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton A. B. How Crowded Is the Cytoplasm?. Cell 1982, 30, 345–347. 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90231-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss J. T.; Dawson J. C.; Fraser C.; Rybski W.; Torres-Sánchez C.; Bradley M.; Patton E. E.; Carragher N. O.; Unciti-Broceta A. Development and bioorthogonal activation of palladium-labile prodrugs of gemcitabine. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 5395–5404. 10.1021/jm500531z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Ruiz B.; Weiss J. T.; Unciti-Broceta A. Efficient palladium-triggered release of vorinostat from a bioorthogonal precursor. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 9974–9980. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam C.; Pérez-López A. M.; Hamilton L.; Rubio-Ruiz B.; Bray T. L.; Sieger D.; Brennan P. M.; Unciti-Broceta A. Bioorthogonal uncaging of the active metabolite of irinotecan by palladium-functionalized microdevices. Chem.—Eur. J. 2018, 24, 16783–16790. 10.1002/chem.201803725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plunk M. A.; Alaniz A.; Olademehin O. P.; Ellington T. L.; Shuford K. L.; Kane R. R. Design and catalyzed activation of Tak-242 prodrugs for localized inhibition of TLR4-induced inflammation. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 141–146. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plunk M. A.; Quintana J. M.; Darden C. M.; Lawrence M. C.; Naziruddin B.; Kane R. R. Design and catalyzed activation of mycophenolic acid prodrugs. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 812–816. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.1c00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Ruiz B.; Pérez-López A. M.; Sebastián V.; Unciti-Broceta A. A minimally-masked inactive prodrug of panobinostat that is bioorthogonally activated by gold chemistry. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 41, 116217. 10.1016/j.bmc.2021.116217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam C.; Bray T. L.; Pérez-López A. M.; Tan E. H.; Rubio-Ruiz B.; Baillache D. J.; Houston D. R.; Salji M. J.; Leung H. Y.; Unciti-Broceta A. A 5-FU precursor designed to evade anabolic and catabolic drug pathways and activated by Pd chemistry in vitro and in vivo. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 552–561. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A. K.; Mehara P.; Das P. Recent Advances in Supported Bimetallic Pd–Au Catalysts: Development and Applications in Organic Synthesis with Focused Catalytic Action Study. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 6672–670. 10.1021/acscatal.2c00725. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hueso J. L.; Sebastian V.; Mayoral A.; Usón L.; Arruebo M.; Santamaría J. Beyond gold: rediscovering tetrakis-(hydroxymethyl)-phosphonium chloride (THPC) as an effective agent for the synthesis of ultra-small noble metal nanoparticles and Pt-containing nanoalloys. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 10427–10433. 10.1039/c3ra40774h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uson L.; Sebastian V.; Mayoral A.; Hueso J. L.; Eguizabal A.; Arruebo M.; Santamaria J. Spontaneous formation of Au–Pt alloyed nanoparticles using pure nano-counterparts as starters: a ligand and size dependent process. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 10152–10161. 10.1039/C5NR01819F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laura U.; Arruebo M.; Sebastian V. Towards the continuous production of Pt-based heterogeneous catalysts using microfluidic systems. Dalton Trans 2018, 47, 1693–1702. 10.1039/C7DT03360E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque-Michel E.; Larrea A.; Lahuerta C.; Sebastian V.; Imbuluzqueta E.; Arruebo M.; Blanco-Prieto M. J.; Santamaria J. A simple approach to obtain hybrid Au-loaded polymeric nanoparticles with a tunable metal load. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 6495–6506. 10.1039/C5NR06850A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uson L.; Yus C.; Mendoza G.; Leroy E.; Irusta S.; Alejo T.; Garcia-Domingo D.; Larrea A.; Arruebo M.; Arenal R.; Sebastian V. Nanoengineering palladium plasmonic nanosheets inside polymer nanospheres for photothermal ther-apy and targeted drug delivery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2106932. 10.1002/adfm.202106932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson M.; Ji Y.; Leong G. J.; Kovach N. C.; Trewyn B. G.; Richards R. M. Hybrid Mesoporous Silica/Noble-Metal Nanoparticle Materials-Synthesis and Catalytic Applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2018, 1, 4386–4400. 10.1021/acsanm.8b00967. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uson L.; Hueso J. L.; Sebastian V.; Arenal R.; Florea I.; Irusta S.; Arruebo M.; Santamaria J. In-situ preparation of ultra-small Pt nanoparticles within rod-shaped mesoporous silica particles: 3-D tomography and catalytic oxidation of n-hexane. Catal. Commun. 2017, 100, 93–97. 10.1016/j.catcom.2017.06.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Liebana M. C.; Hueso J. L.; Fernández-Pacheco R.; Irusta S.; Santamaria J. Luminescent mesoporous nanorods as photocatalytic enzyme-like peroxidase surrogates. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 7766–7778. 10.1039/C8SC03112F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver B. A. How taxol/paclitaxel kills cancer cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 2014, 25, 2677–2681. 10.1091/mbc.e14-04-0916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamler J. T. L.; Ashberry H. M.; Skrabalak S. E.; Koczkur K. M. Random Alloyed Versus Intermetallic Nanoparticles: A Comparison of Electrocatalytic Performance. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1801563 10.1002/adma.201801563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.