Abstract

Background

Electroencephalogram (EEG) has emerged as a non-invasive tool to detect the aberrant neuronal activity related to different stages of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). However, the effectiveness of EEG in the precise diagnosis and assessment of AD and its preclinical stage, amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI), has yet to be fully elucidated. In this study, we aimed to identify key EEG biomarkers that are effective in distinguishing patients at the early stage of AD and monitoring the progression of AD.

Methods

A total of 890 participants, including 189 patients with MCI, 330 patients with AD, 125 patients with other dementias (frontotemporal dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, and vascular cognitive impairment), and 246 healthy controls (HC) were enrolled. Biomarkers were extracted from resting-state EEG recordings for a three-level classification of HC, MCI, and AD. The optimal EEG biomarkers were then identified based on the classification performance. Random forest regression was used to train a series of models by combining participants’ EEG biomarkers, demographic information (i.e., sex, age), CSF biomarkers, and APOE phenotype for assessing the disease progression and individual’s cognitive function.

Results

The identified EEG biomarkers achieved over 70% accuracy in the three-level classification of HC, MCI, and AD. Among all six groups, the most prominent effects of AD-linked neurodegeneration on EEG metrics were localized at parieto-occipital regions. In the cross-validation predictive analyses, the optimal EEG features were more effective than the CSF + APOE biomarkers in predicting the age of onset and disease course, whereas the combination of EEG + CSF + APOE measures achieved the best performance for all targets of prediction.

Conclusions

Our study indicates that EEG can be used as a useful screening tool for the diagnosis and disease progression evaluation of MCI and AD.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13195-023-01181-1.

Keywords: Mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, Electroencephalography, Diagnosis, Prediction, Biomarker

Background

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia, accounting for an estimated 60-80% of cases worldwide [1]. Currently, there is no effective treatment for AD, and only very limited medications show the potentials for delaying the progression of this neurodegenerative disease at its early stage. On the other hand, amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is characterized by cognitive decline greater than normal for a person’s age and education level without notably interfering with activities of daily life [2]. It is well-accepted that MCI is a high-risk factor for the development of AD and reflects a prodromal predementia state of AD, with an estimated conversion rate of 10–15% per year [3]. Taken together, early diagnosis of AD, including detection at MCI or even early stage, may substantially benefit patients from disease-modifying treatments.

The gold standard of AD diagnosis is the Amyloid/Tau/Neurodegeneration (ATN) framework proposed by the National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association in 2018 [4]. In the ATN framework, the biological state of AD is classified through the identification of three biomarkers (i.e., amyloid, tau, and neurodegeneration) measured from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging [4]. Specifically, “A” represents the cortical amyloid PET ligand binding or low CSF Aβ42, “T” refers to elevated CSF phosphorylated tau (P-tau) and cortical tau PET ligand binding, and “N” indicates CSF T-tau, FDG PET hypometabolism, and atrophy on MRI [4]. The ATN framework has been shown to be a feasible way for AD diagnosis and can be also extended to quantify personalized risk profiling for individuals with MCI [5, 6]. However, this approach is typically conducted through a lumbar puncture or PET examination, which is costly, invasive, and highly relies on clinical infrastructure, thus significantly limiting its availability in clinical practice. As such, there are growing demands for the development of new approaches to aid the early diagnosis of AD.

Electroencephalography (EEG), a low-cost, non-invasive, and portable technique that directly measures neural activity with a high temporal resolution, has emerged as a potential tool for detecting neural biomarkers related to MCI and AD [7–10]. Numerous lines of evidence have validated the possibility of using EEG to distinguish MCI and AD patients from healthy cohorts with diverse sensitivity and specificity [11]. Overall, previous EEG studies involving both MCI and AD patients reported relatively consistent neural alterations compared to healthy cohort, including decreased alpha and beta rhythms activity and increased delta and theta oscillations, which are probably the most promising neural biomarkers for early detection of AD, due to their good correlations with patients’ cognitive function [11–15]. In addition, reduced complexity and coherence in EEG recordings, as well as decreased ratios of theta/gamma and high alpha/low alpha, were also reported as potential biomarkers for the diagnosis of AD [15–19].

Despite the convergence of evidence showing EEG-derived biomarkers linked to MCI and AD, there remain important challenges in bringing these findings into clinical practice. In particular, previous studies were largely conducted based on limited sample sizes. During the last three decades, as pointed out in a recent study, more than 95% of the studies that focused on EEG-based classification of MCI or AD were conducted with fewer than 100 participants, making relevant findings unconvincing [15]. Moreover, while AD is the most common form of dementia, symptoms of preclinical and early AD mostly overlap with other types of dementia such as frontotemporal dementia (FTD), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) [20–22]. However, most previous studies have commonly examined EEG signatures related to MCI and AD without the inclusion of other dementias. We argue that the sensitivity and specificity of such EEG biomarkers in early AD diagnosis should be further thoroughly validated on datasets with more types of dementia. Lastly, though a number of EEG biomarkers (e.g., power spectrum, entropy) have been extensively investigated in previous studies [23, 24], clear knowledge gaps remain regarding the effectiveness of such EEG biomarkers in the diagnosis and prediction of the progress of AD.

To address the aforementioned challenges, this study sought to examine key EEG biomarkers that are capable of distinguishing patients with MCI, AD, and other neurodegenerative dementias from healthy participants. We also aimed to investigate how the identified EEG biomarkers were associated with individual cognitive decline and CSF biomarkers. In addition, we implemented a machine learning approach and validated the added value of EEG biomarkers in assessing patients’ cognitive function (i.e., MMSE and MoCA), age of disease onset (ADO), and course of disease (COD).

Materials and methods

Participants

A total of 890 individuals were utilized in the study, including 189 patients with amnestic MCI, 330 patients with AD, 47 patients with FTD, 57 patients with VCI, 21 patients with DLB, and 246 healthy controls (HC). All patients were enrolled from the Department of Neurology, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, between March 2017 and January 2022. The patients of MCI, probable AD, FTD, VCI, and DLB were diagnosed according to the respective clinical-based criteria [25–30]. All HC were recruited from Xiangya Health Management Center, who were matched with age and sex and reported without cognitive decline. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University. All participants or guardians signed the informed consent before the study.

APOE genotyping

The gDNA was extracted from peripheral blood using the standard phenol-chloroform extraction method. All gDNA samples were diluted to 50 ng/μl. A 581-bp fragment was amplified using the following primers: forward 5-CCTACAAATCGGAACTGG-3, and reverse 5-CTCGAACCAGCTCTTGAG-3. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed as previously described [31]. Each PCR product was sequenced using an ABI 3730xl DNA analyzer (ABI, Louis, MO, USA).

CSF collection and analysis

The CSF was collected through a lumbar puncture. The samples were then centrifuged at 2000× g and 4 °C for 10 min and stored at the temperature of −80 °C. All assessments of CSF biomarkers were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), including beta-amyloid (1–40) (EQ 6511–9601), beta-amyloid (1–42) (EQ 6511–9601), total-tau (EQ 6531–9601), and pTau (181) (EQ 6591–9601-L) (EUROIMMUN, Germany). Four core biomarkers, including Aβ42, Aβ40, t-tau, and p-tau were then obtained. All procedures were performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, samples were added to the reagent wells, and the plate was incubated for 3 h at 22°C ± 2°C. After washing, horseradish peroxidase solution was added and incubated for 90 min at 22°C ± 2°C. The plate was then washed with the provided washing buffer, and substrate solution was added. After 30 min incubation protected from light, stop-solution was added, and the optical density (OD) was measured using a microplate reader (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA), at 450 nm, corrected by the reference OD at 620 nm within 30 min of adding the stop solution. Two technical replicates were performed on samples and standards, and the mean of the replicates was used for the final analysis.

EEG collection and preprocessing

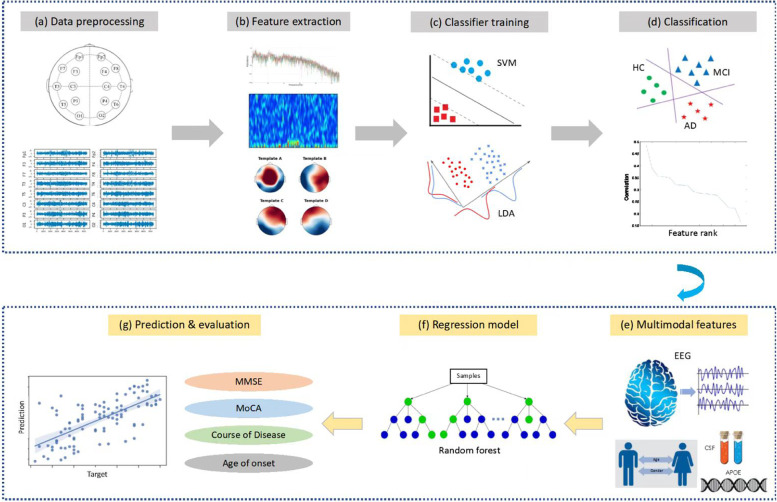

EEG signal was recorded at 200 Hz from the participants in a 10-min eye-closed resting state. Participants were required to remain awake during the entire recording. Standard 16-channels montage was utilized according to the 10–20 International System (channels: Fp1, Fp2, F3, F4, F7, F8, T3, T4, T5, T6, C3, C4, P3, P4, O1, O2). All data analysis was performed using customized Python scripts (Python 3.9, Delaware, USA). The pipeline of the proposed classification and assessment framework is shown in Fig. 1. Briefly, the collected EEG signals were first band-pass filtered between 1 Hz and 55 Hz and further filtered by a 50-Hz notch filter to remove the powerline interference. The filtered data were then re-referenced using a common average re-reference approach. After that, all EEG traces were inspected using a 25-s sliding time window for motion artifact (e.g., spike) detection. Windowed data containing more than 30% artifacts were excluded, leaving the average length of EEG data at 6.2 min. As recommended by a guideline published recently [32], we then segmented the EEG data into a series of epochs using a 5-s time window (i.e., 1000 sample points), resulting in data size of M epochs Í 16 channelsÍ1000 points for each participant. A total of 38,925 epochs were finally obtained from all participants (HC, MCI, and AD).

Fig. 1.

The schematic diagram of the classification a–d of HC/MCI/AD participants and assessment e–g of participants’ cognitive function and disease progression

EEG analyses and feature extraction

We computed multiple types of EEG features, including absolute power, relative power, Hjorth metrics (activity, mobility, and complexity), time-frequency property (STFT), sample entropy, and microstate measures (lifetime, occurrence rate, converting rate). Before feature calculation, each 5s epoch data was filtered by a band-pass filter to extract several frequency components including delta (1–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–13 Hz), beta (13–30 Hz), and gamma (30–45 Hz). We then computed all features from each frequency component of each epoch. Specifically, the absolute power and relative power features were extracted from each frequency band of each channel, while the Hjorth metrics and sample entropy were computed for each channel. Time-frequency (STFT) features were calculated from each frequency band across all channels, while microstate features were extracted across all channels. A detailed definition of these features can be found in the Supplementary material.

Classification of HC, MCI, and AD based on EEG features

We performed a two-step three-level classification of HC, MCI, and AD groups using linear discriminant analysis (LDA) and support vector machine (SVM). Briefly, we first calculated the Pearson’s correlation coefficient between each individual feature dimension and all class labels (HC = 1, MCI = 2, AD = 3), resulting in a series of correlation coefficients between each EEG feature and the class labels. All EEG features were then sorted based on their absolute correlation coefficients in a descending manner, in which the features that yielded a higher coefficient represented more important features and were given higher priority in the classification of the three groups. With the sorted feature set, we started the classification using the feature with the highest priority, and then iteratively added other features one by one (in a forward manner) and evaluated the classification performance at each iteration. The optimal feature set was defined as the set that yielded the highest accuracy, representing the key EEG features essentially related to the diagnosis of MCI and AD. We randomly selected 80% of the samples as a training set, and the left 20% of the samples as a testing set. To avoid the overfitting problem, classifiers were trained using 5-fold cross-validation within the training set, in which 80% of the training set was used to train the model and 20% of the training set was used as the validating set.

Statistical analyses

Among the optimal EEG features identified via the three-way classification, we further explored whether these EEG features could be used to distinguish MCI from AD groups as well as other subtypes of dementia (i.e., DLB, FTD, and VCI) through a series of ANCOVA tests that included age as a covariate. Significant EEG features were determined (p < 0.05) and tested for the between-group difference using a post hoc Tukey test (corrected for age, multiple comparisons were corrected using the FDR Benjamini-Hochberg method). To assess the association among individual neural activity, CSF, and cognitive function, we computed Pearson’s correlation between each EEG feature and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scores, and each CSF biomarker within the combined MCI-AD group.

Assessment of cognitive decline in MCI and AD patients

Next, we aimed to assess how well the selected EEG-based biomarkers, demographic information (i.e., sex, age), the CSF biomarkers, and APOE phenotype can be used to assess individual cognitive function and disease profiles within the MCI and AD groups, through a machine-learning-based approach. Three types of feature sets, including EEG feature-only (EEG), CSF/APOE measures-only (CSF/APOE), and hybrid (EEG + CSF/APOE + demographic information), were independently selected to train a series of regression models for the prediction of the absolute scores of MMSE, MoCA, ADO, and COD, respectively. As the total number of patients with MCI and AD decreased due to missing measurements of CSF and APOE, random forest regression was used in the predictive analysis to avoid an overfitting problem [33]. Random forest regression is an ensemble technique capable of performing regression-based predictive analysis with the use of multiple binary decision trees. The basic idea behind this is to combine multiple simple predictive models in determining the final output rather than relying on a simple regression model. Here, we adopted a 10-fold cross-validation approach to perform relatively robust predictions of measures of interest. In each fold, we randomly split the available participants (MCI + AD) into a training set (80%) and a validating set (20%). After ten iterations, we combined all training and validating sets from each fold to form the complete training set and validating set for the prediction, respectively. The prediction performance of the regression models was assessed using two metrics. The first metric is the coefficient of determination (R2), a statistical measure that assesses how well the predicted scores approximate the target score. The coefficient of determination (R2) is calculated as:

where MSS is the model sum of squares, which is the sum of the squares of the predicted variable minus the mean of the true target variable; TSS is the total sum of squares associated with the target variable, which is the sum of the squares of the target variable minus their mean. R2 ranges from 0 to 1, and a higher R2 indicates better goodness of fit for the observations.

The second metric is the mean absolute error (MAE) which measures the average magnitude of the errors in a set of predictions. MAE can be calculated as:

where n is the number of samples, yi is the target score of the ith sample, and is the predicted score of the ith sample.

Results

Demographic information

The demographic information of 890 participants is summarized in Table 1. No significant difference in age and sex distribution were observed among the MCI, AD, and HC participants (p = 0.50 for age; p = 0.29 for sex).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of six groups of individuals

| MCI (n=189) | AD (n=330) | VCI (n=57) | FTD (n=47) | DLB (n=21) | HC (n=246) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64.77 ± 9.30 | 64.60 ± 9.75 | 67.18 ± 9.80 | 61.36 ± 8.69 | 72.01 ± 9.07 | 63.85 ± 8.20 |

| Sex (male, %) | 68, 35.98 | 121, 36.67 | 31, 54.39 | 23, 48.94 | 13, 61.90 | 104, 42.28 |

| ADO | 62.78 ± 9.42 | 61.80 ± 9.91 | 61.47 ± 11.06 | 61.74 ± 10.42 | 62.67 ± 10.49 | - |

| COD | 1.98 ± 1.91 | 2.90 ± 2.49 | 1.75 ± 1.97 | 2.79 ± 1.65 | 2.00 ± 2.31 | - |

| MMSE | 22.70 ± 4.48 | 11.63 ± 6.28 | 13.51 ± 6.98 | 12.20 ± 7.41 | 12.76 ± 6.44 | 28.62 ± 1.09 |

| MoCA | 16.22 ± 5.01 | 7.02 ± 4.87 | 7.74 ± 4.86 | 7.68 ± 6.74 | 5.94 ± 5.65 | - |

| Aβ42 (pg/ml) | 587.46 ± 439.59 | 408.29 ± 217.28 | - | - | - | - |

| Aβ40 (pg/ml) | 8572.50 ± 6108.20 | 8286.91 ± 6000.22 | - | - | - | - |

| Aβ42/40 | 0.09 ± 0.07 | 0.06 ± 0.04 | - | - | - | - |

| t-tau (pg/ml) | 316.58 ± 289.84 | 506.21 ± 316.95 | - | - | - | - |

| p-tau (pg/ml) | 76.79 ± 51.92 | 104.39 ± 51.94 | - | - | - | - |

| APOE ε4 (%) | 43.86 (25/57) | 52.00 (78/150) |

Fifty-seven with MCI and 150 with AD, completed APOE genotype testing, 43.86% and 52.00% of whom were APOE ε4 carriers (at least one ε4 allele), respectively. In addition, 28 with MCI and 87 with AD completed the CSF core biomarkers testing

ADO age of disease onset, COD course of disease

EEG-based classification results

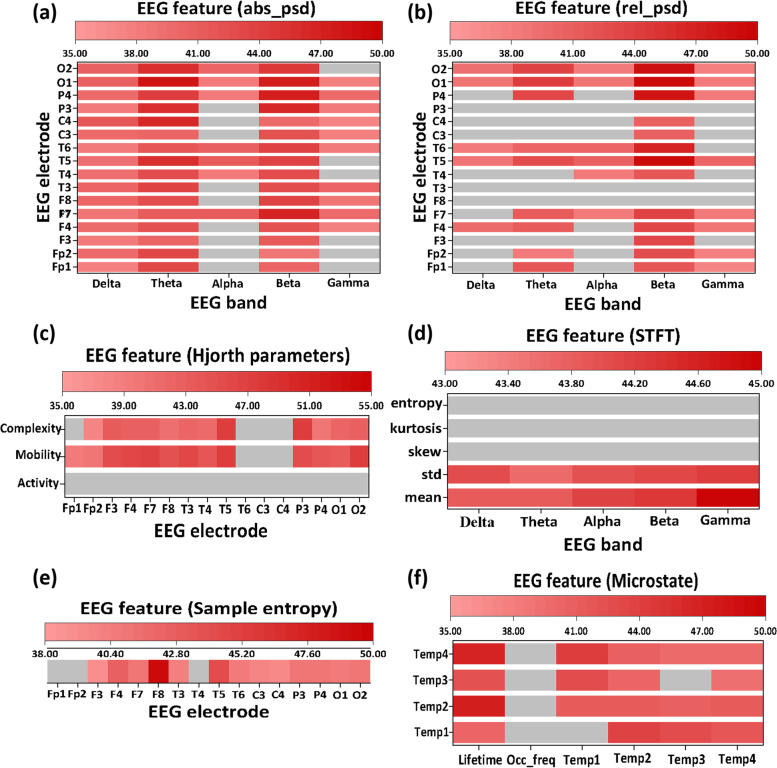

We identified 178 EEG features as the key features for the classification of HC, MCI, and AD. The optimal feature set covered partial features from each EEG feature category, particularly the absolute PSD and the complexity of EEG signals. The distribution of the optimal feature set among all extracted EEG features is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of the optimal feature set among all extracted EEG features in classification (indicated by red). Six types of EEG features were extracted, including a absolute PSD, b relative PSD, c Hjorth metrics (activity, mobility, and complexity), d time-frequency measures (STFT), e sample entropy, and f microstate measures (lifetime, occurrence rate, converting rate)

Table 2 summarizes the classification performance of binary classification and three-level classification. The metrics used to evaluate the classification performance included recall, precision, F1-score, and accuracy, given as:

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

where TP, TN, FP, and FN represent the true positive, true negative, false positive, and false negative, respectively. Generally, Recall measures the model’s ability to correctly predict the positives out of actual positives (i.e., patients). A lower recall score would mean that some patients who are positive are termed as falsely negative. Precision measures the proportion of positively predicted labels that are actually correct. A low precision score would mean that some people who are negative are termed as falsely positive. F1 score represents the model score as a harmonic mean of precision and recall score, which is often used to provide high-level information about the model’s output quality. Model accuracy is defined as the ratio of true positives and true negatives to all positive and negative observations. That is, accuracy evaluates a model’s ability to correctly output a diagnosis out of the total predictions it made.

Table 2.

Classification performance of binary classification and triple classification using EEG-based features

| Classifiers | Recall | Precision | F1 score | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC vs. MCI | ||||

| SVM | 79.6% | 75.8% | 77.7% | 76.7% |

| LDA | 83.8% | 78.1% | 80.9% | 79.8% |

| HC vs. AD | ||||

| SVM | 86.4% | 83.6% | 85.0% | 84.4% |

| LDA | 84.7% | 87.0% | 85.8% | 85.8% |

| HC vs. MCI vs. AD | ||||

| SVM | 70.2% | 70.7% | 69.8% | 70.2% |

| LDA | 70.0% | 70.3% | 69.4% | 70.0% |

As shown in Table 2, the binary classification of HC vs. MCI achieved an accuracy of approximately 80% and an F1 score of 80.9%, while the binary classification of HC and AD achieved an accuracy of approximately 85% and an accuracy of 80%. For a three-level classification of HC vs. MCI vs. AD, both the accuracy and F1 score reached about 70%. Regardless of classification type, the SVM model showed similar classification performance compared to the LDA model.

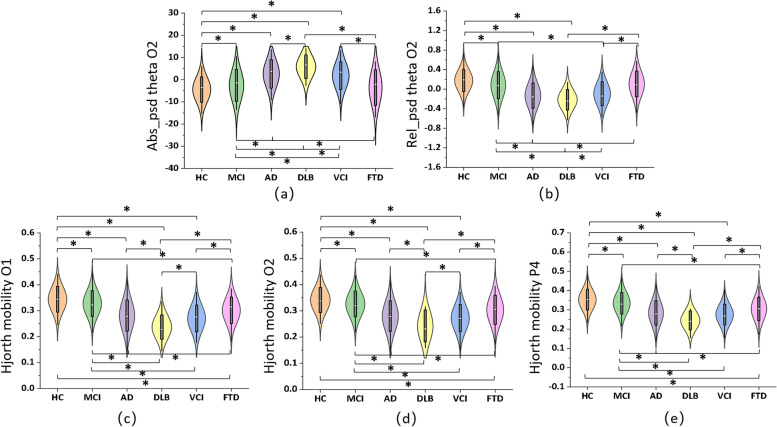

Comparison among MCI/AD and subtypes of dementia

Through a series of ANCOVA tests, we found significant differences among MCI, AD, and other subtypes of dementia in a total of 178 EEG features. Figure 3 displays five EEG features that showed representatively significant differences among all six groups (all Fs > 40, all ps < 0.0001), with results of the post hoc pair-wise comparisons (FDR corrected). Most of the selected features showed significant between-group differences, particularly among HC, MCI, and AD groups. These features mainly included the absolute theta PSD, relative theta PSD at the occipital area, and Hjorth mobility at the parieto-occipital area. Moreover, significant differences between MCI/AD groups and other subtypes of dementia, such as DLB, FTD, or VCI, were also observed in the selected EEG features.

Fig. 3.

The key EEG biomarkers at parieto-occipital regions effectively recognized distinct neural patterns among six groups. Selected EEG features included a absolute theta PSD at O2 (F = 42.46, p < 0.001), b relative theta PSD at O2 (F = 50.11, p < 0.001), c Hjorth mobility at O1 (F = 51.08, p < 0.001), d Hjorth mobility at O2 (F = 50.14, p < 0.001), and e Hjorth mobility at P4 (F = 47.09, p < 0.001). “*” indicates that there is a significant between-group difference (p<0.05, FDR corrected)

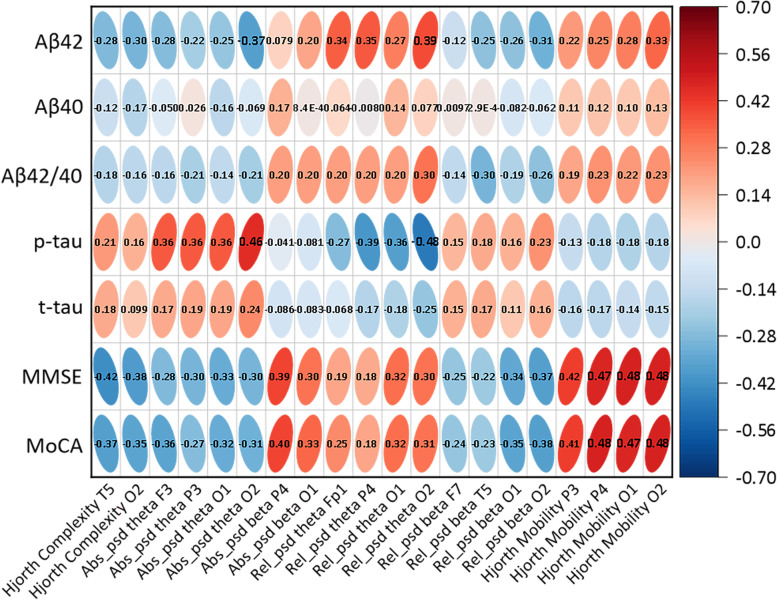

Brain-cognition-CSF relationship in patients with MCI and AD

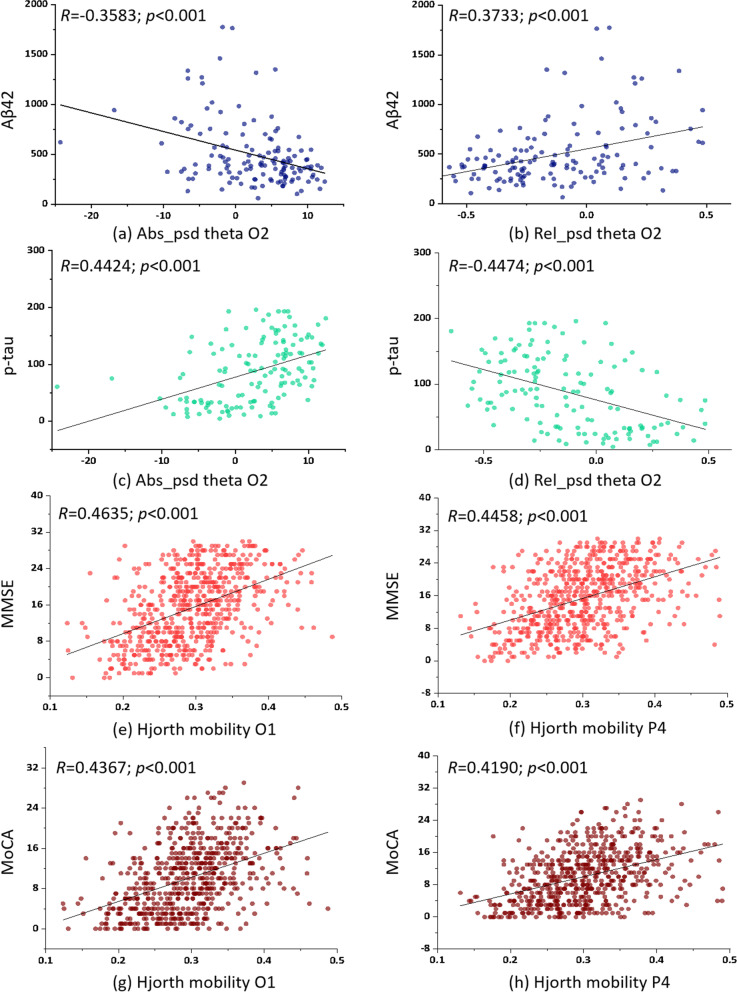

Results of the correlational analyses among brain measures (EEG features), cognitive decline (MMSE, MoCA), and CSF biomarkers are summarized in Fig. 4. The key EEG features that were effective in distinguishing among HC, MCI, AD, DLB, VCI, and FTD were also significantly correlated with multiple cognition/CSF measures. In particular, the absolute theta power of channel O2 was negatively correlated with Aβ42 (r = −0.358, p < 0.001) and positively correlated with p-tau (r = 0.442, p < 0.001), indicating that stronger low-frequency oscillation at the occipital cortex was linked to lower Aβ42 and higher p-tau amount in patients with MCI and AD. Besides, the relative theta power of channel O1 was positively correlated with Aβ42 (r = 0.373, p < 0.001) and negatively correlated with p-tau (r = −0.447, p < 0.001). That is, a stronger low-frequency component at the left occipital cortex was associated with a higher amount of Aβ42 and a lower amount of p-tau in the patients. In terms of cognitive assessment, we found Hjorth mobility of channels O1, O2, and P4 were positively associated with MMSE and MoCA scores, with estimated correlations ranging from 0.416 to 0.464 (all p values < 0.001) (Fig. 5). This finding suggested that stronger instantaneous fluctuation of EEG signals at the parietal and occipital areas was specifically linked to better cognitive function in patients with cognitive impairment.

Fig. 4.

The correlational analyses among brain measures (EEG features), cognitive decline (MMSE, MoCA), and CSF biomarkers. Numbers within the Ellipses represent the correlation coefficients of all x–y pairings

Fig. 5.

Brain-cognition-CSF relationship in patients with MCI and AD. a Absolute theta PSD at O2 vs. Aβ42, b relative theta PSD at O2 vs. Aβ42, c Absolute theta PSD at O2 vs p-tau, d relative theta PSD at O2 vs. p-tau, e Hjorth mobility at O1 vs. MMSE, f Hjorth mobility at P4 vs. MMSE, g Hjorth mobility at O1 vs. MoCA, and h Hjorth mobility at P4 vs. MoCA

Assessing AD-related behaviors using multimodal features

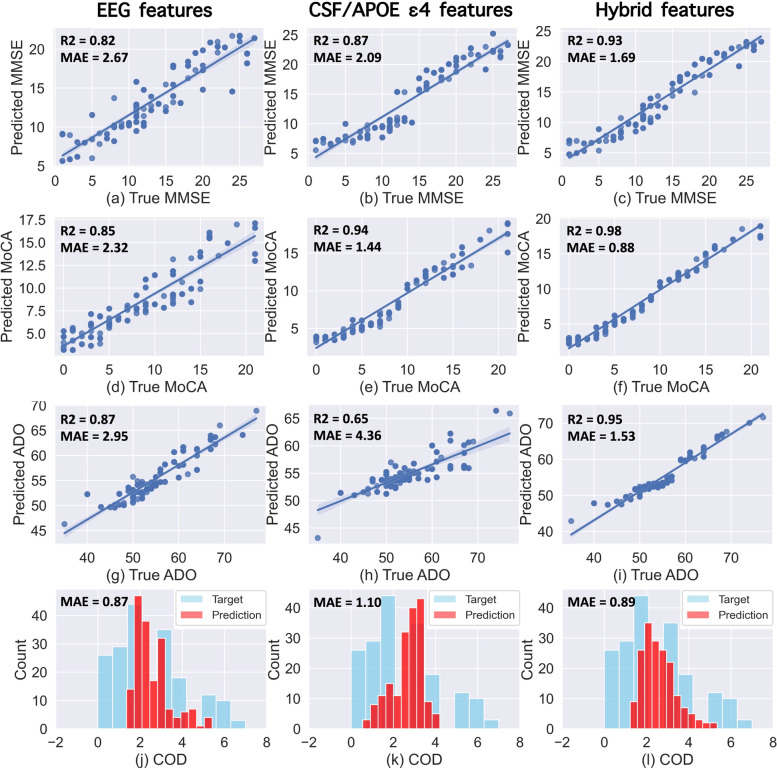

The assessment performance of each target measure, including the MMSE score, MoCA score, ADO, and COD, are shown in Fig. 6. For the assessment of the patient’s MMSE score (Fig. 6a–c), EEG-only features achieved moderate performance (MAE = 2.67, R2 = 0.82), while CSF-APOE features achieved slightly better performance (MAE = 2.09, R2 = 0.87). The best performance was obtained using hybrid features as predictors of the regression model (MAE = 1.69, R2 = 0.93). Similar results were obtained in the assessment of the patient’s MoCA score (Fig. 6d–f). EEG-only features achieved moderate performance (MAE = 2.32, R2 = 0.85), whereas CSF-APOE biomarkers achieved better performance (MAE = 1.44, R2 = 0.94). The hybrid features (MAE = 0.88, R2 = 0.98) were most effective in the assessment of MoCA scores.

Fig. 6.

Results of the prediction analyses using different combinations of features. The predictions of MMSE (a–c), MoCA (d–f), ADO (g–i), and COD (j–l) were obtained using EEG feature only (first column), CSF/APOE biomarkers (second column), hybrid features (EEG, CSF/APOE, sex, and age) as the predictors of the regression model, respectively. R2 is the determination coefficient, and MAE is the mean absolute error

In the assessment of ADO (Fig. 6g–i), EEG-only features achieved moderate performance (MAE = 2.95 years, R2 = 0.87), which was markedly higher compared to the performance obtained from CSF-APOE features (MAE = 4.36 years, R2 = 0.65). The best prediction of ADO was obtained from the hybrid features (MAE = 1.53 years, R2 = 0.95). For COD (Fig. 6j–l), EEG-only features achieved the best performance (MAE = 0.87 years, no correlation coefficient due to the discrete and small range of COD) compared to a moderate performance using hybrid features (MAE = 0.89 years) or CSF-APOE features (MAE = 1.12 years).

Discussion

Growing evidence has demonstrated that EEG measurements reflect the effects of AD neuropathology on the brain neural signal transmission underpinning cognitive processes [3, 34–36], yet it remains largely unknown about the accuracy and reliability of different types of EEG biomarkers in facilitating the early detection and prediction of AD progression. To our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively evaluate the impacts of promising EEG biomarkers on effectively differentiating patients with MCI, AD, and other subtypes of dementias from HC, and to clarify the associations among EEG-based neural signatures, individual cognitive function, and CSF biomarkers. Remarkably, we provided strong evidence supporting that the inclusion of multi-dimensional information (i.e., EEG biomarkers, CSF/APOE ε4 measures, and demographic characteristics) is highly effective in assessing patients’ cognitive function and clinical status through a machine learning approach. Together, our findings suggest that EEG biomarkers are of great importance for the early detection of AD in clinical practice.

Identifying effective EEG biomarkers associated with AD could help us elucidate the neural mechanism underlying this neurodegenerative disorder and facilitate its early diagnosis. As reported in previous studies, patients with MCI and AD generally showed decreased alpha/beta power and increased theta/delta power in a broad range of brain regions such as frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital areas [23, 37–39]. Other abnormal brain alterations, such as functional connectivity and entropy, were also reported [17, 37, 40–42]. However, the multi-group classification of HC, MCI, and AD based on these EEG biomarkers has not yet achieved satisfactory accuracy, possibly due to the difficulty in selecting meaningful EEG metrics and the heterogeneity of patients when the sample size is limited. In this study, we addressed this challenge by recruiting a relatively large sample of healthy controls (246) and patients (189 MCI and 330 AD) in a clinical framework and achieved a decent three-level classification accuracy (over 70%). In particular, the key EEG biomarkers that have the most prominent effect on differentiating MCI and AD from the HC included power spectral density measures and entropy, which aligns well with previous studies [37, 43]. Our findings thus confirm that the power spectral density metrics and entropy are significantly altered in AD patients. Importantly, given the decent sample size and the rigorous EEG acquisition condition in the present study, our findings could provide a solid benchmark for developing useful EEG-based tools for the early diagnosis and screening of AD.

We explored whether EEG-based biomarkers could differentiate MCI and AD from other subtypes of dementia, a critical clinical question that has never been systematically studied before. We found that multiple EEG biomarkers revealed highly distinct patterns over MCI/AD-related groups and other dementias. First, the spectral measures of theta rhythm (absolute/relative PSD) at the occipital region presented with a purely monotonic trend from HC to MCI and AD, a finding that has been consistently reported in previous studies [14, 37]. Post hoc pair-wise comparisons further confirmed that these measures were capable of differentiating HC/MCI/AD groups from other dementias. We hypothesize that the alterations of the EEG power spectral density may be present not only in AD-related cognitive decline, but also in other dementias that have different neurodegenerative causes (e.g., FTD, VCI). And such alterations could be potentially differentiated by EEG measurements. This premise is supported by recent studies suggesting that EEG technique may be able to distinguish MCI/AD patients from other dementias such as FTD, VCI, or DLB [18–20]. However, it is worth noting that we didn’t perform a systematic classification among all six groups in this study due to the relatively small sample sizes of FTD, VCI, and DLB groups. Future work is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of EEG techniques in diagnosing different types of dementias.

We found that Hjorth mobility of EEG signals at parietal and occipital regions was highly effective in distinguishing among HC, MCI, AD, DLB, VCI, and FTD groups. This was evidenced by the consistently decreased mobility in the HC-MCI-AD trajectory and the significant differences in most pair-wise comparisons among all six groups. Hjorth mobility is one of the Hjorth parameters that measure the complexity of a signal [44]. Among the Hjorth parameters, mobility is defined as a ratio per time unit and may also be treated as a mean frequency. Though less explored in AD studies, decreased Hjorth complexity was reported in the AD cohort compared to HC [45]. Previous studies also showed that the complexity measure of EEG could be effective in the differential diagnosis of MCI and AD [24, 46], which strengthens the findings in our study. Besides, the decreased mobility in MCI and AD group reflects the decreased frequency of neuronal oscillation caused by cognitive decline. This finding is in line with a previous study that reported a shift in the power spectrum toward the lower frequencies (delta and theta band) [37]. Given the high discrimination power of these biomarkers that have never been reported in the literature, our study provides first-hand evidence for developing EEG-based quantitative, statistically significant criteria that could be applied to the differential diagnosis of dementia in routine assessments in the future.

Understanding the relationship between EEG biomarkers and currently used biomarkers (e.g., CSF) could improve our knowledge of the pathological basis of AD. With a large sample size, we found that key EEG biomarkers, including power spectrum at the occipital region and signal complexity at the parieto-occipital area, were significantly associated with both patient’s cognitive decline and levels of p-tau and Aβ42. These findings consolidate results from previous studies that reported significant correlations between EEG-derived biomarkers and CSF measures (e.g., Aβ42, tau, p-tau) in limited samples of AD patients [47, 48]. Together with the above classification result, in addition to being able to detect AD and other dementias, EEG biomarkers may be used as potential measures for monitoring the progression of AD. In particular, CSF and neuroimaging biomarkers have been a core basis in recently proposed recommendations and research criteria for the diagnosis of AD at the preclinical, prodromal, and overt dementia stages in the clinical practice [4, 49]. Therefore, EEG-derived biomarkers could be a valuable addition to the clinically adopted neuroimaging biomarkers.

To further evaluate the added value of including EEG in clinical practice, we implemented a machine learning approach to assess patients’ cognitive decline, ADO, and COD using standalone EEG biomarkers and a combination of EEG and other recommended biomarkers. CSF/APOEε4 measures were more effective than EEG biomarkers in assessing patients’ cognitive function (i.e., MMSE and MoCA). This is expected given that ATN measures have been widely accepted as recommended biomarkers for clinical diagnosis of AD [4, 50]. Yet, EEG biomarkers were found to be more effective than the CSF/APOE measures in assessing disease ADO and COD, suggesting the advantage of using EEG to evaluate the temporal profile of AD. As expected, the combination of the measures of EEG, CSF, APOE ε4, age, and sex achieved the best performance in all assessments. It has been recommended that the combination of amyloid-based biomarkers with other measures such as abnormal neurodegeneration biomarkers could provide higher accuracy and reliability in the prediction of future cognitive decline and conversion rate to AD than amyloid measure alon e[51]. Our finding thus supports the premise that the fusion of multi-dimensional information could potentially improve the power of primary outcomes in clinical trials.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, we have a limited sample size for other subtypes of dementia, such as FTD, VCI, and DLB. Though the focus of this study is to perform a three-way classification of HC/MCI/AD, future work should include various types of dementia to assess the sensitivity and specificity of EEG-based early detection of AD. In addition, due to the limited availability of CSF/APOE measures, only a small number of MCI and AD patients are available for the prediction analysis in the present study. The effectiveness of adding EEG biomarkers into a model for monitoring and prediction of AD progression should be evaluated with larger samples in the future. Finally, this study only included measurements for a single time point. Longitudinal studies with large cohorts would be conducted in the future to assess whether EEG biomarkers can be used to trace the progress trajectory of AD or evaluate the efficacy of pharmacological/therapeutic interventions for AD patients.

Conclusions

Increasing evidence suggests that EEG biomarkers are diagnostically meaningful and associated with the clinical progression of AD. In this study, we identified distinct neural biomarkers that were specifically linked to the CSF measures and cognitive function of AD patients. These neural biomarkers mainly included the power spectrum alterations of low-frequency oscillations at the occipital area and the altered signal complexity at the parietal and occipital regions. Finally, through a machine learning approach, we found that the combination of EEG biomarkers, CSF/APOE ε4 measures, and demographic information of patients was most effective in assessing individual cognitive function and disease progression.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all participants in the present study.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADO

Age of disease onset

- ATN

Amyloid/Tau/Neurodegeneration

- COD

Course of disease

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- DLB

Dementia with Lewy bodies

- EEG

Electroencephalogram

- FTD

Frontotemporal dementia

- HC

Healthy controls

- LDA

Linear discriminant analysis

- MAE

Mean absolute error

- MCI

Mild cognitive impairment

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- MoCA

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- SVM

Support vector machine

- VCI

Vascular cognitive impairment

Authors’ contributions

B.J. and L.S. provided concept and design; B.J., H.Z., H.L., X.X., X.L., Q.Y., X.L., Y.Z. and L.F. collected participants' information; Original data in this study acquired by H.J. and S.H.; R.L., K.Q., H.P., Y.L., W.F., X.W., Y.D. and Y.Y. analysed and explained the data; B.J. and R.L. wrote the main manuscript; L.S. supervised the whole process. All authors reviewed the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported the National Key R&D Program of China (No.2020YFC2008500), STI2030-Major Projects (No.2021ZD0201803), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81971029, 82071216), Hunan Innovative Province Construction Project (No.2019SK2335), and Hu-Xiang Youth Project (No. 2021RC3028).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed in the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Study approval by the Institutional Review Board of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University was obtained before the study initiation. All participants consented to participate in this study, which was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Bin Jiao and Rihui Li contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Gauthier S, Reisberg B, Zaudig M, Petersen RC, Ritchie K, Broich K, et al. Mild cognitive impairment. Lancet. 2006;367(9518):1262–1270. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68542-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen RC, Doody R, Kurz A, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rabins PV, et al. Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2001;58(12):1985–1992. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.12.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaubert S, Raimondo F, Houot M, Corsi MC, Naccache L, Diego Sitt J, et al. EEG evidence of compensatory mechanisms in preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2019;142(7):2096–2112. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jack CR, Jr, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(4):535–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheltens P, De Strooper B, Kivipelto M, Holstege H, Chételat G, Teunissen CE, et al. Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 2021;397(10284):1577–1590. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32205-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Maurik IS, Vos SJ, Bos I, Bouwman FH, Teunissen CE, Scheltens P, et al. Biomarker-based prognosis for people with mild cognitive impairment (ABIDE): a modelling study. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(11):1034–1044. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30283-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meghdadi AH, Stevanović Karić M, McConnell M, Rupp G, Richard C, Hamilton J, et al. Resting state EEG biomarkers of cognitive decline associated with Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0244180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smailovic U, Johansson C, Koenig T, Kåreholt I, Graff C, Jelic V. Decreased Global EEG Synchronization in Amyloid Positive Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer's Disease Patients-Relationship to APOE ε4. Brain Sci. 2021;11(10):1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Vecchio F, Miraglia F, Alu F, Menna M, Judica E, Cotelli M, et al. Classification of Alzheimer's Disease with Respect to Physiological Aging with Innovative EEG Biomarkers in a Machine Learning Implementation. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;75(4):1253–1261. doi: 10.3233/JAD-200171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vecchio F, Miraglia F, Iberite F, Lacidogna G, Guglielmi V, Marra C, et al. Sustainable method for Alzheimer dementia prediction in mild cognitive impairment: Electroencephalographic connectivity and graph theory combined with apolipoprotein E. Ann Neurol. 2018;84(2):302–314. doi: 10.1002/ana.25289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farina FR, Emek-Savaş DD, Rueda-Delgado L, Boyle R, Kiiski H, Yener G, et al. A comparison of resting state EEG and structural MRI for classifying Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage. 2020;215:116795. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassani R, Falk TH, Fraga FJ, Cecchi M, Moore DK, Anghinah R. Towards automated electroencephalography-based Alzheimer's disease diagnosis using portable low-density devices. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2017;33:261–271. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatz F, Hardmeier M, Benz N, Ehrensperger M, Gschwandtner U, Rüegg S, et al. Microstate connectivity alterations in patients with early Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7:78. doi: 10.1186/s13195-015-0163-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Musaeus CS, Engedal K, Høgh P, Jelic V, Mørup M, Naik M, et al. EEG Theta Power Is an Early Marker of Cognitive Decline in Dementia due to Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;64(4):1359–1371. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monllor P, Cervera-Ferri A, Lloret MA, Esteve D, Lopez B, Leon JL, et al. Electroencephalography as a Non-Invasive Biomarker of Alzheimer's Disease: A Forgotten Candidate to Substitute CSF Molecules? Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(19):10889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Le Roc'h K. EEG coherence in Alzheimer disease, by Besthorn et al. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1994;91(3):232-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Stam CJ, van der Made Y, Pijnenburg YA, Scheltens P. EEG synchronization in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 2003;108(2):90–96. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2003.02067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moretti DV, Pievani M, Fracassi C, Binetti G, Rosini S, Geroldi C, et al. Increase of theta/gamma and alpha3/alpha2 ratio is associated with amygdalo-hippocampal complex atrophy. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17(2):349–357. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moretti DV, Prestia A, Fracassi C, Binetti G, Zanetti O, Frisoni GB. Specific EEG changes associated with atrophy of hippocampus in subjects with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:253153. doi: 10.1155/2012/253153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nardone R, Sebastianelli L, Versace V, Saltuari L, Lochner P, Frey V, et al. Usefulness of EEG Techniques in Distinguishing Frontotemporal Dementia from Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. Dis Markers. 2018;2018:6581490. doi: 10.1155/2018/6581490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schumacher J, Taylor JP, Hamilton CA, Firbank M, Cromarty RA, Donaghy PC, et al. Quantitative EEG as a biomarker in mild cognitive impairment with Lewy bodies. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12(1):82. doi: 10.1186/s13195-020-00650-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Babiloni C, Arakaki X, Bonanni L, Bujan A, Carrillo MC, Del Percio C, et al. EEG measures for clinical research in major vascular cognitive impairment: recommendations by an expert panel. Neurobiol Aging. 2021;103:78–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2021.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vecchio F, Babiloni C, Lizio R, Fallani Fde V, Blinowska K, Verrienti G, et al. Resting state cortical EEG rhythms in Alzheimer's disease: toward EEG markers for clinical applications: a review. Suppl Clin Neurophysiol. 2013;62:223–236. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-7020-5307-8.00015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McBride JC, Zhao X, Munro NB, Smith CD, Jicha GA, Hively L, et al. Spectral and complexity analysis of scalp EEG characteristics for mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer's disease. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2014;114(2):153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, Jr, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, Mendez MF, Kramer JH, Neuhaus J, et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 9):2456–2477. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, Kertesz A, Mendez M, Cappa SF, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011;76(11):1006–1014. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821103e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sachdev P, Kalaria R, O'Brien J, Skoog I, Alladi S, Black SE, et al. Diagnostic criteria for vascular cognitive disorders: a VASCOG statement. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2014;28(3):206–218. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O'Brien JT, Feldman H, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65(12):1863–1872. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiao B, Tang B, Liu X, Xu J, Wang Y, Zhou L, et al. Mutational analysis in early-onset familial Alzheimer's disease in Mainland China. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(8):1957.e1–1957.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Babiloni C, Barry RJ, Basar E, Blinowska KJ, Cichocki A, Drinkenburg W, et al. International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology (IFCN) - EEG research workgroup: Recommendations on frequency and topographic analysis of resting state EEG rhythms. Part 1: Applications in clinical research studies. Clin Neurophysiol. 2020;131(1):285–307. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2019.06.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Breiman L. Random Forests. Machine Learning. 2001;45(1):5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeKosky ST, Scheff SW. Synapse loss in frontal cortex biopsies in Alzheimer's disease: correlation with cognitive severity. Ann Neurol. 1990;27(5):457–464. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scheff SW, Price DA, Schmitt FA, DeKosky ST, Mufson EJ. Synaptic alterations in CA1 in mild Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2007;68(18):1501–1508. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260698.46517.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ieracitano C, Mammone N, Hussain A, Morabito FC. A novel multi-modal machine learning based approach for automatic classification of EEG recordings in dementia. Neural Netw. 2020;123:176–190. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2019.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Babiloni C, Binetti G, Cassetta E, Dal Forno G, Del Percio C, Ferreri F, et al. Sources of cortical rhythms change as a function of cognitive impairment in pathological aging: a multicenter study. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117(2):252–268. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Babiloni C, Frisoni GB, Pievani M, Vecchio F, Lizio R, Buttiglione M, et al. Hippocampal volume and cortical sources of EEG alpha rhythms in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Neuroimage. 2009;44(1):123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cassani R, Estarellas M, San-Martin R, Fraga FJ, Falk TH. Systematic Review on Resting-State EEG for Alzheimer's Disease Diagnosis and Progression Assessment. Dis Markers. 2018;2018:5174815. doi: 10.1155/2018/5174815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jelic V, Johansson SE, Almkvist O, Shigeta M, Julin P, Nordberg A, et al. Quantitative electroencephalography in mild cognitive impairment: longitudinal changes and possible prediction of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21(4):533–540. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gallego-Jutglà E, Solé-Casals J, Vialatte FB, Dauwels J, Cichocki A. A theta-band EEG based index for early diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;43(4):1175–1184. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li R, Nguyen T, Potter T, Zhang Y. Dynamic cortical connectivity alterations associated with Alzheimer's disease: An EEG and fNIRS integration study. Neuroimage Clin. 2019;21:101622. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.101622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maturana-Candelas A, Gómez C, Poza J, Pinto N, Hornero R. EEG Characterization of the Alzheimer's Disease Continuum by Means of Multiscale Entropies. Entropy (Basel). 2019;21(6):544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Hjorth B. EEG analysis based on time domain properties. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1970;29(3):306–310. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(70)90143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dauwels J, Vialatte F, Cichocki A. Diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease from EEG signals: where are we standing? Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010;7(6):487–505. doi: 10.2174/156720510792231720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poil SS, de Haan W, van der Flier WM, Mansvelder HD, Scheltens P, Linkenkaer-Hansen K. Integrative EEG biomarkers predict progression to Alzheimer's disease at the MCI stage. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:58. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jelic V, Blomberg M, Dierks T, Basun H, Shigeta M, Julin P, et al. EEG slowing and cerebrospinal fluid tau levels in patients with cognitive decline. Neuroreport. 1998;9(1):157–160. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199801050-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smailovic U, Koenig T, Kåreholt I, Andersson T, Kramberger MG, Winblad B, et al. Quantitative EEG power and synchronization correlate with Alzheimer's disease CSF biomarkers. Neurobiol Aging. 2018;63:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Babiloni C, Arakaki X, Azami H, Bennys K, Blinowska K, Bonanni L, et al. Measures of resting state EEG rhythms for clinical trials in Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations of an expert panel. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(9):1528–1553. doi: 10.1002/alz.12311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosenberg A, Solomon A, Soininen H, Visser PJ, Blennow K, Hartmann T, et al. Research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer's disease: findings from the LipiDiDiet randomized controlled trial. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2021;13(1):64. doi: 10.1186/s13195-021-00799-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burnham SC, Bourgeat P, Doré V, Savage G, Brown B, Laws S, et al. Clinical and cognitive trajectories in cognitively healthy elderly individuals with suspected non-Alzheimer's disease pathophysiology (SNAP) or Alzheimer's disease pathology: a longitudinal study. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(10):1044–1053. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Supplementary material.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed in the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.