Abstract

CSDBase (http://www.chemie.uni-marburg.de/~csdbase/) is an interactive Internet-embedded research platform providing detailed information on proteins containing the cold shock domain (CSD). It consists of two separated database cores, one dedicated to CSD protein information, and one to provide a powerful resource to relevant literature with emphasis on the bacterial cold shock response. In addition to detailed protein information and useful cross links to other web sites, CSDBase contains computer-generated CSD structure models for most CSD-containing protein sequences available at NCBI non-redundant protein database at the time of CSDBase establishment. These models were calculated on the basis of known crystal and/or NMR structures using SWISS-MODEL and can be downloaded as PDB structure coordinate files for viewing and for manipulation with other software tools. CSDBase will be regularly updated and is organized in a compact form providing user friendly interfaces to both database cores which allow for easy data retrieval.

INTRODUCTION

Proteins interacting with the biological information molecules DNA and RNA play important cellular roles in all organisms. One widespread superfamily of proteins implicated in such function(s) contains the cold shock domain (CSD) which consists of ∼70 amino acids and harbors the nucleic acid binding motifs RNP1 and RNP2. This domain is highly conserved from bacteria to man (1) and the corresponding protein superfamily has been classified into five distinct subgroups which comprise (i) the bacterial cold shock proteins (CSPs), (ii) eukaryotic Y-box proteins (YBPs), (iii) a fraction of the plant glycine-rich protein family (GRPs), (iv) LIN-28 proteins from the Caenorhabditis nematode family, and (v) the mammalian Unr protein (2). Out of this large variety of proteins, so far only structures of members of the bacterial CSP subfamily have been determined (3–8). With ∼70 amino acids in length, CSPs represent the prototype of the CSD and share a highly similar overall fold consisting of five antiparallel β-sheets forming a β-barrel structure with surface exposed aromatic and basic residues (RNP1 and RNP2 motif) that have been shown to be responsible for nucleic acid binding properties of variable binding affinities and sequence selectivities (9–12).

In addition to at least one CSD located near the N-terminus, the eukaryotic counterparts of this protein superfamily have incorporated a broad variety of other motifs that are thought to confer either a more specific template recognition or an ancillary enzymatic function (2). It has been demonstrated that these proteins are involved in a variety of important functions such as mRNA masking, coupling of transcription to translation and developmental timing and regulation (13,14). However, although a large body of information has been accumulated, most features of the CSD protein family members are yet to be explored. Strikingly, recent data indicated that, in spite of a very similar overall fold, even the most simple members of the CSD superfamily, the bacterial CSPs, have surprisingly diverse function(s). Apart from its properties as a transcriptional activator (15), CspA from Escherichia coli has also been shown to destabilize RNA secondary structures (16) and possesses transcriptional antiterminator functions like its homologs CspC and CspE (17). Moreover, CspE was found to be implicated in promoting or protecting chromosome folding and to act as a high-copy suppressor of mutations in chromosomal partition gene mukB (18), while CspD, which appears to exist exclusively as a homodimer, is specifically expressed in the stationary phase and has been shown to inhibit replication (19,20). At least for Bacillus subtilis it is evident that the presence of one out of three individuals of this hierarchically organized protein class is essential even under optimal growth conditions (21). Detailed investigations have further revealed that removal of two of the three csp genes present in B.subtilis results in abnormal nucleoid structure, growth defects, deregulated protein synthesis and the inability to differentiate to endospores (21,22). Although it has been shown that B.subtilis CSPs colocalize with ribosomes in vivo (23), and can be functionally replaced in part by translation initiation factor IF1 from E.coli (24), the nature of CSP function is far from being understood.

In the light of rapidly accumulating sequence data, collections of smaller data subsets stored in specialized databases allow for a much more convenient access to molecular biological information. Therefore, in order to facilitate research activities focused on the interesting and rapidly growing CSD protein superfamily briefly outlined above, we have created CSDBase, an interactive Internet-embedded research platform providing detailed information on CSD containing proteins and the bacterial cold shock response (http://www.chemie.uni-marburg.de/~csdbase/).

DATABASE CONTENT, ACCESS AND USAGE

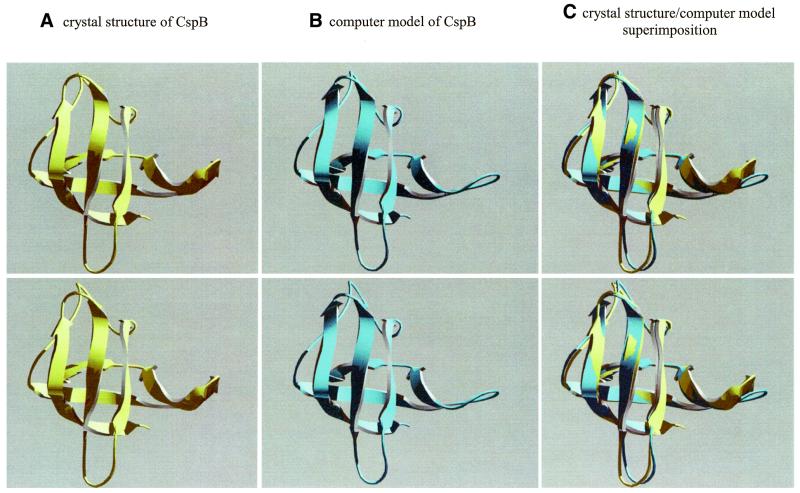

CSD protein sequences were acquired by performing a BLASTP search at NCBI non-redundant database using cold shock protein CspB from B.subtilis as template (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/; 25,26). Except for the number of descriptions and the number of displayed alignments which were both set to a non-limiting value, BLAST default settings were used. On the basis of experimentally determined CSD protein structures (5–8), each of the protein sequences retrieved and thereby detected to have homologies to CSD containing CspB, was subjected to comparative protein modeling using SWISS-MODEL first approach mode (http://www.expasy.ch/swissmod/SWISS-MODEL.html; 27,28). The constructed homology-models were automatically analyzed by the WHAT IF verification program (29,30) and were stored in CSDBase as multi-layered atom coordinate files (PDB format). Each layer holds the atom coordinates of a separate model where the first layer represents the model structure generated for the protein of interest while the other layers contain the coordinates of the experimental structure(s) used as template(s) for the calculations as taken from PDB (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/). To demonstrate the quality of the generated protein models, Figure 1 shows stereo images of a typical raw model structure generated for CspB from Bacillus caldolyticus in comparison to its crystal structure that was experimentally determined later (r.m.s.d. = 0.87 Å). Although the theoretical structure model shown in Figure 1 fits well to the experimentally determined, the reader should be reminded, that such homology models should be regarded as raw models which often require additional inspection and further refinement.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the crystal structure of cold shock protein CspB from B.caldolyticus [(A) PDB accession no. 1C9O; A-chain (4)] and its computer-generated model structure counterpart as stored in CSDBase [(B) first layer of CSDBase file name CspB_baccl (this work)]. Ribbon model stereo pairs were generated with Swiss-PdbViewer version 3.7b2 (34) and images were rendered using POV-Ray version 3.1g. Superimposition (C) of CspB crystal structure (yellow) on CspB computer model (cyan) was performed using the ‘iterative magic fit’ function of Swiss-PdbViewer (r.m.s.d. = 0.87 Å for the carbon α trace). Note that the presented computer model was generated with SWISS-MODEL (27,28) on the basis of known structures for CspB and CspA from B.subtilis and E.coli, respectively, at a time where the crystal structure of CspB from B.caldolyticus was not yet available.

For those sequences which allowed for generation of a protein model, all relevant information was extracted via NCBI from the original database entries and was stored together with the downloadable protein model atomic coordinate file in CSDBase. In addition to the protein sequences, accession numbers, protein names, gene names and a brief description of the proteins, the modeled regions of the protein sequences were indicated, the number of amino acids for each protein was determined and its pI and mass were calculated using the proteomic tools available at ExPASy server (http://ca.expasy.org/tools/pi_tool.html; 31). One of the interesting results obtained during this data acquisition was that, in contrast to what is sometimes believed, bacterial CSPs are not uniformly acidic but rather stretch over a broad pI range and can have a basic pI of as high as 10.28 (CspH from E.coli). Moreover, apart from a N-terminal CSD, the genus Mycobacterium harbors CSP sequences which contain an additional C-terminal domain of approximately 70 amino acids of unknown structure and function. Since Mycobacteria have some features in common with eukaryotes and utilize these as hosts, it might be possible that this CSD extension feature reflects further development of simple CSD proteins in the direction of higher organized Y-box proteins.

In addition to the CSD protein data and model structures described above, CSDBase provides a powerful, easy-to-use retrieval system for the relevant literature which was compiled using the PubMed interface at NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PubMed/; 25). CSDBase literature entries (as well as those for the protein data) can be searched by choosing from a range of pre-defined topics such as author, year of publication, journal name, etc., followed by entering a user-defined phrase (an asterisk will result in display of all entries currently available). In all cases, data output can be ordered according to different aspects. It should be noted that at this stage the content of the literature database core is restricted to bacterial CSPs and the bacterial cold shock response. We are currently working on adding the eukaryotic publications.

CSDBase can be accessed via the Internet at http://www.chemie.uni-marburg.de/~csdbase/ using Microsoft Internet Explorer version 5 or higher and is organized in a compact self-explanatory form. Note that with most other browsers, database functions remain non-operational. Further details concerning usage of CSDBase can be viewed directly by selecting the ‘Info’ submenu displayed in the title bar of every CSDBase page.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Since the CSD-containing cold shock proteins are implicated to play a major role during the bacterial cold shock response (32,33), in an additional pilot project a third database core is currently under construction to incorporate detailed proteomic data including clickable 2D gels of cold shock stressed bacteria. Moreover, two novel CSD protein structures await release in the near future (PDB accession nos 1G6P and 1H95) which will allow us to further refine the model structures presently available in CSDBase. In this manner, it is our intention to continuously extend the capabilities of this initial version of CSDBase step-by-step to provide a powerful starting platform for researchers working on CSD containing proteins and the bacterial cold shock response.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Rolf Henrich for a quick introduction into Internet-embedded database organization. This work was supported by Sonderforschungsbereich 395 and Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wolffe A.P., Tafuri,S., Ranjan,M. and Familari,M. (1992) The Y-box factors: a family of nucleic acid binding proteins conserved from Escherichia coli to man. New Biol., 4, 290–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graumann P.L. and Marahiel,M.A. (1998) A superfamily of proteins containing the cold shock domain. Trends Biochem. Sci., 23, 286–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kremer W., Schuler,B., Harrieder,S., Geyer,M., Gronwald,W., Welker,C., Jaenicke,R. and Kalbitzer,H.R. (2001) Solution NMR structure of the cold-shock protein from the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. Eur. J. Biochem., 268, 2527–2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mueller U., Perl,D., Schmid,F.X. and Heinemann,U. (2000) Thermal stability and atomic-resolution crystal structure of the Bacillus caldolyticus cold shock protein. J. Mol. Biol., 297, 975–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newkirk K., Feng,W., Jiang,W., Tejero,R., Emerson,S.D., Inouye,M. and Montelione,G.T. (1994) Solution NMR structure of the major cold shock protein (CspA) from Escherichia coli: identification of a binding epitope for DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 5114–5118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schindelin H., Marahiel,M.A. and Heinemann,U. (1993) Universal nucleic acid-binding domain revealed by crystal structure of the B. subtilis major cold-shock protein. Nature, 364, 164–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schindelin H., Jiang,W., Inouye,M. and Heinemann,U. (1994) Crystal structure of CspA, the major cold shock protein of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 5119–5123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnuchel A., Wiltscheck,R., Czisch,M., Herrler,M., Willimsky,G., Graumann,P., Marahiel,M.A. and Holak,T.A. (1993) Structure in solution of the major cold-shock protein from Bacillus subtilis. Nature, 364, 169–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopez M.M. and Makhatadze,G.I. (2000) Major cold shock proteins, CspA from Escherichia coli and CspB from Bacillus subtilis, interact differently with single-stranded DNA templates. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1479, 196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez M.M., Yutani,K. and Makhatadze,G.I. (1999) Interactions of the major cold shock protein of Bacillus subtilis CspB with single-stranded DNA templates of different base composition. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 33601–33608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phadtare S. and Inouye,M. (1999) Sequence-selective interactions with RNA by CspB, CspC and CspE, members of the CspA family of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol., 33, 1004–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schröder K., Graumann,P., Schnuchel,A., Holak,T.A. and Marahiel,M.A. (1995) Mutational analysis of the putative nucleic acid-binding surface of the cold-shock domain, CspB, revealed an essential role of aromatic and basic residues in binding of single-stranded DNA containing the Y-box motif. Mol. Microbiol., 16, 699–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sachetto-Martins G., Franco,L.O. and de Oliveira,D.E. (2000) Plant glycine-rich proteins: a family or just proteins with a common motif? Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1492, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sommerville J. (1999) Activities of cold-shock domain proteins in translation control. Bioessays, 21, 319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brandi A., Pon,C.L. and Gualerzi,C.O. (1994) Interaction of the main cold shock protein CS7.4 (CspA) of Escherichia coli with the promoter region of hns. Biochimie, 76, 1090–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang W., Hou,Y. and Inouye,M. (1997) CspA, the major cold-shock protein of Escherichia coli, is an RNA chaperone. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bae W., Xia,B., Inouye,M. and Severinov,K. (2000) Escherichia coli CspA-family RNA chaperones are transcription antiterminators. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 7784–7789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu K.H., Liu,E., Dean,K., Gingras,M., DeGraff,W. and Trun,N.J. (1996) Overproduction of three genes leads to camphor resistance and chromosome condensation in Escherichia coli. Genetics, 143, 1521–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamanaka K. and Inouye,M. (1997) Growth-phase-dependent expression of cspD, encoding a member of the CspA family in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 179, 5126–5130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamanaka K., Zheng,W., Crooke,E., Wang,Y.-H. and Inouye,M. (2001) CspD, a novel DNA replication inhibitor induced during the stationary phase in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol., 39, 1572–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graumann P., Wendrich,T.M., Weber,M.H.W., Schröder,K. and Marahiel,M.A. (1997) A family of cold shock proteins in Bacillus subtilis is essential for cellular growth and for efficient protein synthesis at optimal and low temperatures. Mol. Microbiol., 25, 741–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weber M.H.W., Volkov,A.V., Fricke,I., Marahiel,M.A. and Graumann,P.L. (2001) Localization of cold shock proteins to cytosolic spaces surrounding nucleoids in Bacillus subtilis depends on active transcription. J. Bacteriol., 183, 6435–6443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mascarenhas J., Weber,M.H.W. and Graumann,P.L. (2001) Specific polar localization of ribosomes in Bacillus subtilis depends on active transcription. EMBO Rep., 2, 685–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber M.H.W., Beckering,C.L. and Marahiel,M.A. (2001) Complementation of cold shock proteins by translation initiation factor IF1 in vivo. J. Bacteriol., 183, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wheeler D.L., Church,D.M., Lash,A.E., Leipe,D.D., Madden,T.L., Pontius,J.U., Schuler,G.D., Schriml,L.M., Tatusova,T.A., Wagner,L. and Rapp,B.A. (2001) Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 11–16. Updated article in this issue: Nucleic Acids Res. (2002), 30, 13–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altschul S.F., Madden,T.L., Schäffer,A.A., Zhang,J., Zhang,Z., Miller,W. and Lipman,D.J. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peitsch M.C. (1995) Protein modeling by E-mail. Biotechnology, 13, 658–660. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peitsch M.C. (1996) ProMod and Swiss-Model: Internet-based tools for automated comparative protein modelling. Biochem. Soc. Trans, 24, 274–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hooft R.W.W., Vriend,G., Sander,C. and Abola,E.E. (1996) Errors in protein structures. Nature, 381, 272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vriend G. (1990) WHAT IF: a molecular modelling and drug design program. J. Mol. Graph., 8, 52–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bjellqvist B., Hughes,G.J., Pasquali,C., Paquet,N., Ravier,F., Sanchez,J.-C., Frutiger,S. and Hochstrasser,D.F. (1993) The focusing positions of polypeptides in immobilized pH gradients can be predicted from their amino acid sequences. Electrophoresis, 14, 1023–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Graumann P.L. and Marahiel,M.A. (1999) Cold shock response in Bacillus subtilis. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 1, 203–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamanaka K. (1999) Cold shock response in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 1, 193–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guex N. and Peitsch,M.C. (1997) SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis, 18, 2714–2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]