Abstract

Background

Ileus commonly occurs after abdominal surgery, and is associated with complications and increased length of hospital stay (LOHS). Onset of ileus is considered to be multifactorial, and a variety of preventative methods have been investigated. Chewing gum (CG) is hypothesised to reduce postoperative ileus by stimulating early recovery of gastrointestinal (GI) function, through cephalo‐vagal stimulation. There is no comprehensive review of this intervention in abdominal surgery.

Objectives

To examine whether chewing gum after surgery hastens the return of gastrointestinal function.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE (via Ovid), MEDLINE (via PubMed), EMBASE (via Ovid), CINAHL (via EBSCO) and ISI Web of Science (June 2014). We hand‐searched reference lists of identified studies and previous reviews and systematic reviews, and contacted CG companies to ask for information on any studies using their products. We identified proposed and ongoing studies from clinicaltrials.gov, World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and metaRegister of Controlled Trials.

Selection criteria

We included completed randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that used postoperative CG as an intervention compared to a control group.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently collected data and assessed study quality using an adapted Cochrane risk of bias (ROB) tool, and resolved disagreements by discussion. We assessed overall quality of evidence for each outcome using Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE). Studies were split into subgroups: colorectal surgery (CRS), caesarean section (CS) and other surgery (OS). We assessed the effect of CG on time to first flatus (TFF), time to bowel movement (TBM), LOHS and time to bowel sounds (TBS) through meta‐analyses using a random‐effects model. We investigated the influence of study quality, reviewers’ methodological estimations and use of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) programmes using sensitivity analyses. We used meta‐regression to explore if surgical site or ROB scores predicted the extent of the effect estimate of the intervention on continuous outcomes. We reported frequency of complications, and descriptions of tolerability of gum and cost.

Main results

We identified 81 studies that comprised 9072 participants for inclusion in our review. We categorised many studies at high or unclear risk of the bias' assessed. There was statistical evidence that use of CG reduced TFF [overall reduction of 10.4 hours (95% CI: ‐11.9, ‐8.9): 12.5 hours (95% CI: ‐17.2, ‐7.8) in CRS, 7.9 hours (95% CI: –10.0, ‐5.8) in CS, 10.6 hours (95% CI: ‐12.7, ‐8.5) in OS]. There was also statistical evidence that use of CG reduced TBM [overall reduction of 12.7 hours (95% CI: ‐14.5, ‐10.9): 18.1 hours (95% CI: ‐25.3, ‐10.9) in CRS, 9.1 hours (95% CI: ‐11.4, ‐6.7) in CS, 12.3 hours (95% CI: ‐14.9, ‐9.7) in OS]. There was statistical evidence that use of CG slightly reduced LOHS [overall reduction of 0.7 days (95% CI: ‐0.8, ‐0.5): 1.0 days in CRS (95% CI: ‐1.6, ‐0.4), 0.2 days (95% CI: ‐0.3, ‐0.1) in CS, 0.8 days (95% CI: ‐1.1, ‐0.5) in OS]. There was statistical evidence that use of CG slightly reduced TBS [overall reduction of 5.0 hours (95% CI: ‐6.4, ‐3.7): 3.21 hours (95% CI: ‐7.0, 0.6) in CRS, 4.4 hours (95% CI: ‐5.9, ‐2.8) in CS, 6.3 hours (95% CI: ‐8.7, ‐3.8) in OS]. Effect sizes were largest in CRS and smallest in CS. There was statistical evidence of heterogeneity in all analyses other than TBS in CRS.

There was little difference in mortality, infection risk and readmission rate between the groups. Some studies reported reduced nausea and vomiting and other complications in the intervention group. CG was generally well‐tolerated by participants. There was little difference in cost between the groups in the two studies reporting this outcome.

Sensitivity analyses by quality of studies and robustness of review estimates revealed no clinically important differences in effect estimates. Sensitivity analysis of ERAS studies showed a smaller effect size on TFF, larger effect size on TBM, and no difference between groups for LOHS.

Meta‐regression analyses indicated that surgical site is associated with the extent of the effect size on LOHS (all surgical subgroups), and TFF and TBM (CS and CRS subgroups only). There was no evidence that ROB score predicted the extent of the effect size on any outcome. Neither variable explained the identified heterogeneity between studies.

Authors' conclusions

This review identified some evidence for the benefit of postoperative CG in improving recovery of GI function. However, the research to date has primarily focussed on CS and CRS, and largely consisted of small, poor quality trials. Many components of the ERAS programme also target ileus, therefore the benefit of CG alongside ERAS may be reduced, as we observed in this review. Therefore larger, better quality RCTS in an ERAS setting in wider surgical disciplines would be needed to improve the evidence base for use of CG after surgery.

Keywords: Humans, Chewing Gum, Abdomen, Abdomen/surgery, Gastrointestinal Motility, Gastrointestinal Motility/physiology, Ileus, Ileus/therapy, Length of Stay, Postoperative Complications, Postoperative Complications/therapy, Postoperative Period, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Recovery of Function, Recovery of Function/physiology, Time Factors

Plain language summary

Chewing gum after surgery to help recovery of the digestive system

Background

When people have surgery on their abdomen, the digestive system can stop working for a few days. This is called ileus, and can be painful and uncomfortable. There are different causes of ileus, and several ways of treating or preventing it. One possible way of preventing ileus is by chewing gum. The idea is that chewing gum tricks the body into thinking it is eating, causing the digestive system to start working again. It is important to do this review because ileus is common: it is estimated that up to a third of people having bowel surgery suffer from ileus.

Main Findings

This review found 81 relevant studies that recruited over 9000 participants in total. The studies mainly focussed on people having bowel surgery or caesarean section, but there were some studies of other surgery types. There were few studies of children. Most studies were of poor quality, which may mean their results are less reliable. We found some evidence that people who chewed gum after an operation were able to pass wind and have bowel movements sooner than people who did not chew gum. We also found some evidence that people who chewed gum after an operation had bowel sounds (gurgling sounds heard using a stethoscope held to the abdomen) slightly sooner than people who did not chew gum. There was a small difference in how long people stayed in hospital between people who did or did not chew gum. There were no differences in complications (such as infection or death) between people who did or did not chew gum. There was also no difference in the overall cost of treatment between people who did or did not chew gum.

Conclusions

There is some evidence that chewing gum after surgery may help the digestive system to recover. However, the studies included in this review are generally of poor quality, which meant that their results may not be reliable. We also know that there are many factors affecting ileus, and that modern treatment plans attempt to reduce risk of ileus. Therefore to further explore using chewing gum after surgery, more studies would be needed which are larger, of better quality, include different types of surgery, and consider recent changes in health care systems.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings ‐ continuous outcomes.

| Chewing gum compared with control for improving postoperative recovery of gastrointestinal function in people undergoing abdominal surgery | |||||

|

Patient or population: individuals undergoing abdominal surgery Settings: hospital setting Intervention: chewing gum Comparison: standard care (no chewing gum) | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Control group | Intervention group | ||||

|

Time to first flatus Hours |

The mean time to first flatus in the control group was 49.9 hours | The mean time to first flatus in the intervention group was 10.4 hours shorter (11.9 to 8.9 hours shorter) | 8293 (77) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | High risk of bias in outcome reporting as participants cannot be blinded for this outcome Small to moderate confidence intervals |

|

Time to first bowel movement Hours |

The mean time to first bowel movement in the control group was 75.4 hours | The mean time to first bowel movement in the intervention group was 12.7 hours shorter (14.5 to 10.9 hours shorter) | 7283 (62) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | High risk of bias in outcome reporting as participants cannot be blinded for this outcome Some suspicion of publication bias based on visual inspection of the funnel plot Small to moderate confidence intervals |

|

Length of hospital stay Days |

The mean length of hospital stay in the control groups was 6.8 days | The mean length of hospital stay in the intervention group was 0.7 days shorter (0.8 to 0.5 days shorter) | 5278 (50) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | High risk of bias in outcome reporting as blinding methods poorly reported Some suspicion of publication bias based on visual inspection of the funnel plot Small to moderate confidence intervals |

|

Time to first bowel sounds Hours |

The mean time to first bowel sounds in the control group was 21.9 hours | The mean time to first bowel sounds in the intervention group was 5.0 (6.4 to 3.7 hours shorter) | 3981 (23) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | High risk of bias in outcome reporting as blinding methods poorly reported Few studies reported accurately recording this outcome Moderate confidence intervals |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

For each continuous outcome, many studies' results were statistically manipulated or estimated to allow inclusion in our meta‐analyses (see Table 3)

For each continuous outcome, there were studies whose results could not be included in this meta‐analysis (see Table 4), therefore the evidence provided here does not include all evidence available

All evidence used is directly relevant to the research question

High heterogeneity between studies for each continuous outcome. Heterogeneity is not well explained by the pre‐specified subgroup analyses

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings ‐ descriptive outcomes.

| Chewing gum compared with control for improving postoperative recovery in people undergoing abdominal surgery | |||

|

Patient or population: individuals undergoing abdominal surgery Settings: hospital setting Intervention: chewing gum Comparison: standard care (no chewing gum) | |||

| Outcomes | Relative effect | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

Complications Frequency |

Potential small reduction in frequency of nausea and vomiting Little difference reported in frequency of mortality Little difference reported in frequency of infection Little difference reported in frequency of readmission Potential small reduction in frequency of other complications Only one study reported complications which authors believed may have been related to the intervention (due to aerophagia whilst chewing gum) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | Methods used for recording complications is poorly reported Low frequency provides little substantial evidence A diverse range of complications are reported; therefore it is difficult to group these together to draw meaningful comparisons High risk of bias in outcome reporting as blinding methods poorly reported |

|

Tolerability of gum Anecdotal evidence, interviews, questionnaires and surveys |

Gum was generally well‐tolerated by participants | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | The majority of evidence is anecdotal This outcome is generally measured and reported in an insufficient manner |

| Cost | One study found that cost of hospitalisation was lower in the intervention group, but did not reach significance (intervention group: 2379 ± 195 USD, control group: 2672 ± 265 USD) One study found that hospital charges did not differ significantly between the groups (intervention group: 2451 ± 806 YTL, 1493 to 4619 YTL; control group: 2102 ± 678 YTL, 1073 to 3497 YTL; P = 0.206) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | Only 2 studies reported cost analyses |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

Background

Description of the condition

Although there is not currently one widely accepted definition of ileus (Vather 2013), this condition has previously been described as a transient impairment of bowel motility after abdominal surgery or other trauma (Holte 2000). Ileus is therefore considered to be an inevitable consequence of abdominal surgery (Tu 2014; Gervaz 2006), and commonly occurs following colorectal, gynaecological, thoracic and urological surgical procedures (Bashankaev 2009). Prevalence of ileus is difficult to estimate due to the lack of accurate reporting and lack of a standardised definition (Barletta 2014; Vather 2013). Evidence indicates that ileus is most prolonged following large bowel surgery, and reports in this surgical discipline range from 3 to 32% of patients (Kronberg 2011; Vasquez 2009). There is evidence however that the introduction of laparoscopic surgery may reduce incidence of ileus (Fujii 2014; Hosono 2006).

Resolution of ileus is an important factor in the speed of postoperative recovery. Ileus can lead to nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort (Johnson 2009), increased length of hospital stay (LOHS) (Schuster 2006) and therefore increased costs (Fitzgerald 2009). Additionally, it has been suggested that postoperative ileus can result in poorer wound healing, delays in time to mobilisation and resumption of oral intake, and reduced patient satisfaction (Behm 2003).

The pathogenesis of postoperative ileus is multifactorial (Bonventre 2014; Le Blanc‐Louvry 2002), as numerous factors influencing the surgical stress response contribute to the development and duration of ileus. These include degree of bowel manipulation, level of surgical trauma, anaesthesia and effects of postoperative modifiers such as pain management with opiates (Holte 2000; Lim 2013; Tu 2014). Additionally, suggested risk factors for postoperative ileus include increasing age, high body mass index and ethnic minority (Chang 2002; Svatek 2010).

Resolution of ileus usually occurs two to five days postoperatively (Livingston 1990; Warren 2011). Generally the small intestine is the first part of the digestive system to recover postoperatively within 24 hours, followed by the stomach within 24 to 48 hours, and the large bowel after 48 to 72 hours (Gervaz 2006; Nimarta 2013). Various approaches have been investigated to prevent onset and reduce duration of ileus, incorporating both reducing surgical stress and optimising postoperative care. These include providing nasogastric decompression, performing minimally invasive surgery, promoting early ambulation, avoiding preoperative bowel preparation, limiting intravenous fluid administration, using prokinetic agents, using epidural analgesia and reducing opiate use for pain management (Story 2009). Many of these practices have been incorporated into the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) programme endorsed across UK National Health Service (NHS) hospitals nationally. Early postoperative feeding is another component of ERAS that may stimulate gut motility, thereby reducing onset and duration of ileus (Fanning 2011). However, early postoperative feeding is not universally accepted, as it is not always well tolerated by patients. For example, vomiting and the risk of postoperative complications such as aspiration may be increased (Basaran 2009; Lewis 2001).

Additionally, a number of non‐clinical approaches to reduce postoperative ileus have been suggested. These include drinking coffee, herbal formulae, acupuncture, mechanical abdominal massage and rocking‐chair motion (Endo 2014; Garcia 2008; Le Blanc‐Louvry 2002; Massey 2010; Müller 2012).

Description of the intervention

It has been suggested that chewing gum (CG) postoperatively may help recovery of gastrointestinal (GI) function by stimulating earlier resumption of bowel activity (Asao 2002; Lim 2013). CG is a form of sham feeding that replicates the process of eating without ingestion of food. Thus, it may stimulate GI function without producing the complications associated with early feeding e.g. nausea, vomiting. CG is a cheap and widely available product which most people have previously experienced. Therefore it is an intervention which is likely to be well tolerated by individuals postoperatively.

How the intervention might work

In 2002, results from a small randomised controlled trial (RCT) suggested that use of CG may hasten postoperative recovery (Asao 2002). Since that time, a number of trials have examined the effect of CG on postoperative ileus, and several have demonstrated benefits (Abd‐El‐Maeboud 2009; Ledari 2012; Marwah 2012). It is thought that there are three main mechanisms by which CG may reduce duration and prevent onset of ileus (Tandeter 2009). First, stimulation of gut motility by cephalo‐vagal stimulation which in turn leads to release of GI hormones. Second, ‘sham feeding’ tricks parts of the digestive system and stimulates motility. Third, encouragement of release of pancreatic juices and saliva (Tandeter 2009). This intervention may provide a means to reduce the duration of postoperative ileus without the adverse effects of increased vomiting and nausea associated with early postoperative feeding. In addition, this may provide an intervention in patients where food cannot be tolerated.

Serious adverse events are unlikely to occur with this intervention; studies have reported no adverse events (Choi 2011; Husslein 2013). However incidents such as indigestion or bloating, potentially due to aerophagia whilst chewing, may occur (Zaghiyan 2013). Additionally CG may cause choking in individuals with dysphagia and in people who have difficulty chewing, such as individuals with dental problems, poor/loosely fitting dentures and young children.

Why it is important to do this review

Chewing gum may offer an innovative intervention for improving postoperative GI function recovery. Earlier resolution of ileus may result in reductions in patient discomfort, complications and LOHS. Considering the number of people who undergo abdominal operations each year globally, and the high prevalence of ileus within these, this could have implications for healthcare costs and recovery. It is therefore essential that benefits and costs are carefully evaluated. This systematic review (SR) summarises the available evidence on the use of CG in reducing the onset and duration of ileus by improving the rate of return of postoperative GI function.

Objectives

The objective of this review is to examine whether chewing gum (CG) after surgery hastens the return of gastrointestinal (GI) function. The review considers the impact of CG on indicators of bowel function [time to first flatus (TFF), bowel movement (TBM) and bowel sounds (TBS)] and on recovery [length of hospital stay (LOHS) and postoperative complications]. The review also considers tolerability of CG and the financial costs and benefits associated with using this intervention.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all RCTs that used chewing gum as an intervention regardless of publication language. Quasi‐randomised trials were not included.

Types of participants

Participants of any age who underwent abdominal surgery for any indication.

Types of interventions

Interventions consisted of CG in the immediate postoperative recovery period and use of a control group for comparison. Studies in which the gum contained an active therapeutic agent were not considered unless the agent was also administered to the control group. Studies in which the intervention consisted of gum in combination with another intervention were not considered.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Primary outcomes were time to first flatus (TFF) (hours) and time to first bowel movement (TBM) (hours).

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were length of hospital stay (LOHS) (days), time to first bowel sounds (TBS) (as an additional marker of return of GI function; hours), reports of postoperative complications (frequency), tolerability of gum and costs and benefits (descriptive outcomes).

Outcome measures were reported in units considered to be clinically meaningful.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, Issue 5, 2014), MEDLINE (via Ovid) from 1966 to present, MEDLINE (via PubMed) from 1966 to present, EMBASE (via Ovid) from 1980 to present, CINAHL (via EBSCO) from 1990 to present and ISI Web of Science from 1900 to present, using a combination of MeSH and key terms. The search terms included “gum”, “recovery” and “ileus” and any derivatives of those terms. Searching for RCTs was done by hand by screening abstracts and full‐texts where necessary.

No limitation based on language or date of publication was applied. One of the authors (RP) developed the search strategies, see Appendix 1 for CENTRAL; Appendix 2 for MEDLINE (via Ovid); Appendix 3 for MEDLINE (via PubMed); Appendix 4 for EMBASE (via Ovid); Appendix 5 for CINAHL (via EBSCO); and Appendix 6 for ISI Web of Science. The first search was run in June 2013, repeated in January 2014, and updated in June 2014.

Searching other resources

We hand‐searched reference lists of identified studies, previous reviews and SRs for additional relevant articles. We searched Google Scholar every two weeks up to page 20 with various combinations of key terms such as “gum, ileus”, “gum, bowel” and “gum, gastrointestinal”. We contacted authors for information on references from their reference lists if we could not access or identify them ourselves.

We searched the following registers for proposed and ongoing trials: clinicaltrials.gov, World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and metaRegister of Controlled Trials using combinations of search terms including “gum chewing”, “gum AND ileus”, “gum AND bowel” and “sham feeding”. We did not impose any date or language restrictions. We approached principal investigators of identified ongoing trials that had not yet been published, to ask for relevant data. In addition, we contacted CG manufacturers (Wrigley Company, Cadbury Trebor Bassett, Lotte, Perfetti Van Melle and Hershey’s) to ask for information on published or unpublished material on their product.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

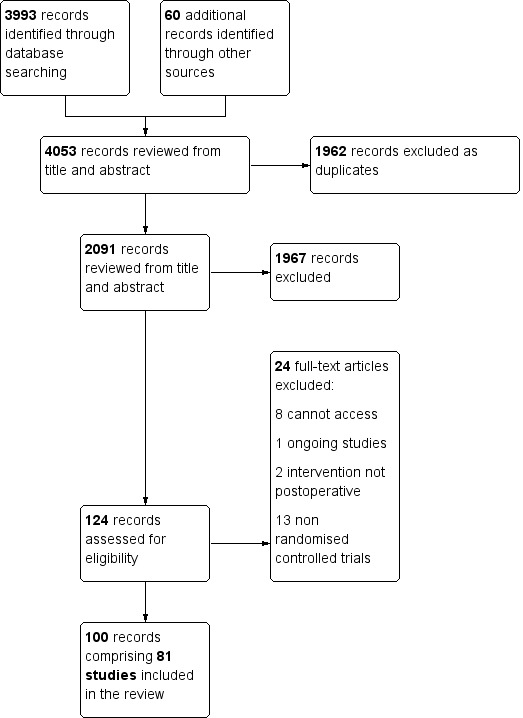

Two review authors (VS and GH) independently examined the titles and abstracts of studies identified through the search strategy. Inconsistency between review authors regarding articles for full‐text reading was resolved by consultation with a third review author (RP or CP). We obtained full‐text papers for all studies that could not be excluded on the basis of title and abstract. The same review authors then independently refined their selection by examining the selected articles and excluding those not relevant to this review. Review authors recorded agreement on trial inclusion, and disagreement was resolved by predetermined co‐review authors (ST and SJL for clinical disputes, RP and CP for methodological disputes). We contacted original study authors where further clarity was needed in order to select a study for inclusion. We documented decisions on all studies and these are presented in the PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (VS and either GH or RP) independently extracted data from each study. Review authors were blinded to each other’s data. We developed a data extraction form adapted for this review from the original provided by Cochrane. Three authors (VS, GH and RP) examined this on several studies selected for inclusion, and revised it for ease of extraction and to include further useful data items. We extracted data regarding participant demographics, participant disease status, surgical procedures, control group postoperative care and the intervention (frequency and duration of CG) using these predesigned data extraction forms. In order to ensure accurate data extraction, three review authors (VS, GH and RP) independently extracted and compared data from 16 (20%) studies for consistency.

Many of the identified studies were published in other languages. Titles and abstracts were generally available in English, and where studies appeared to meet the inclusion criteria, they were either translated or directly extracted onto the data extraction form. Eighteen studies were directly extracted from Chinese (Mandarin), and 19 were translated from Chinese (Mandarin), Farsi, German, Korean and Spanish and then extracted by reviewers.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Either two or three review authors (VS and either GH or RP) independently assessed risk of bias (ROB). We developed our own ROB tool based on the criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), tailored to this review. We developed this as data extraction continued. We included specific examples and numerical cut‐off points in the adapted ROB tool (Appendix 7), to ensure consistency of ROB assessments. We then discussed ROB for all studies to ensure uniformity and agreement. Where possible, we sought protocols to aid assessment of selective outcome reporting bias. We reported use of sample size/power calculations and intention‐to‐treat analyses as measures of methodological quality. We labelled ROB as ‘high’, ‘low’ or ‘unclear’ for the following categories: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of personnel, blinding of outcome assessment (for TFF, TBM, LOHS, TBS and complications), incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and ‘other’ risks (e.g. differences in baseline demographics, study sample size).

Measures of treatment effect

We considered continuous variables (TFF, TBM, LOHS and TBS) as weighted mean differences (WMDs), and included 95% confidence intervals. We reported complications as frequency of nausea and vomiting, mortality, infection, readmissions, other complications, and complications related to the intervention. We descriptively recorded any information on tolerability of gum or financial burden/benefit reported in the studies.

Unit of analysis issues

We used individual participants as the unit of analysis. No studies used cluster randomisation.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted authors when key information was missing. When no further information was provided or authors could not be contacted, we estimated results or used the available data where appropriate (see Data synthesis). Table 3 summarises these estimates and transformations.

1. Estimated results and assumptions.

| Study | Estimated results |

| Atkinson 2014 | Time to first flatus, time to first bowel movement, length of hospital stay and time to first bowel sounds reported as median, interquartile range and range (unpublished information). Mean and standard deviation calculated using the formulae described by Hozo 2005 |

| Bonventre 2014 | Time to first flatus, time to first bowel movement and length of hospital stay reported as median, interquartile range and range (unpublished information). Mean and standard deviation calculated using the formulae described by Hozo 2005 |

| Choi 2011 | Time to first flatus, time to first bowel movement and length of hospital stay reported as median and range (assumed to be range due to broad range of numbers and authors' later paper, Choi 2014). Mean and standard deviation calculated using the formulae described by Hozo 2005 |

| Choi 2014 | Time to first flatus, time to first bowel movement and length of hospital stay reported as median and range. Mean and standard deviation calculated using the formulae described by Hozo 2005 |

| Crainic 2009 | Time to first flatus and time to first bowel movement reported as mean and standard error of the mean. Standard deviation calculated from the standard error of the mean |

| Garshasbi 2011 | Time to first flatus and time to first bowel movement reported as a median (assumed to be means for analyses), time to first bowel sounds reported as a mean. Standard deviation estimations assumed from the most conservative reliable value within the caesarean section subgroup (time to first flatus, time to first bowel movement and time to first bowel sounds: Shang 2010 for both intervention and control groups). Complications reported as % of participants: 2% in gum chewing group and 10% in control group; these have been rounded to the nearest whole number (4.76 rounded to 5 in the gum chewing group, 26.2 rounded to 26 in the control group) |

| Husslein 2013 | Time to first flatus, time to first bowel movement and length of hospital stay reported as median and range. Mean and standard deviation calculated using the formulae described by Hozo 2005 |

| Jakkaew 2013 | Time to first flatus and length of hospital stay reported as median and range. Mean and standard deviation calculated using the formulae described by Hozo 2005 |

| Jin 2010 | Complications reported as % of participants: 8.7% in gum chewing group and 28.6% in control group; these have been rounded to the nearest whole number (4.002 rounded to 4 in the gum chewing group, 12.012 rounded to 12 in the control group) |

| Kafali 2010 | Postoperative antiemetic requirement assumed to indicate frequency of nausea and vomiting. Intestinal enema for discharge assumed to indicate an 'other' complication |

| Lee 2004 | Time to first flatus, time to first bowel movement and length of hospital stay reported as a mean. Assumed that a t‐test was conducted. P values reported as P < 0.03, P < 0.83 and P < 0.42. Conservative assumption of P = 0.03, P = 0.83 and P = 0.42 used to permit estimation of the t value. Standard deviation estimations assumed from the most conservative reliable value within the other surgery subgroup (time to first flatus: Park 2009 for the intervention group, Schweizer 2010 for the control group; time to first bowel movement: Webster 2007 for the intervention group, Chou 2006 for the control group; length of hospital stay: Schweizer 2010 for both intervention and control groups) |

| Lim 2013 | Time to first flatus and time to first bowel movement reported as mean and standard error of the mean. Study data from laparoscopic and open surgery subgroups combined to provide mean values for one intervention and one control group for length of hospital stay (unpublished data), standard deviation estimations assumed from the most conservative reliable value within the colorectal surgery subgroup (Bahena‐Aponte 2010 for both intervention and control groups) |

| Lu 2010a | Length of hospital stay reported as a mean. Standard deviation estimations assumed from the most conservative reliable value within the other surgery subgroup (Schweizer 2010 for both intervention and control groups) |

| Lu 2011 | Time to first flatus, length of hospital stay and time to first bowel sounds reported as a mean. P = 0.001 for time to first flatus, used to estimate the t value. P values presented as P < 0.001 for time to first bowel sounds, conservative assumption of P = 0.001 used to permit estimation of the t value. Standard deviation estimations assumed from the most conservative reliable value within the other surgery subgroup (time to first flatus: Park 2009 for the intervention group, Schweizer 2010 for the control group; length of hospital stay: Schweizer 2010 for both intervention and control groups; time to first bowel sounds: Marwah 2012 for both intervention and control groups) |

| Qiao 2011 | Time to first flatus and time to first bowel movement reported as a mean. Standard deviation estimations assumed from the most conservative reliable value within the other surgery subgroup (time to first flatus: Park 2009 for the intervention group, Schweizer 2010 for the control group; time to first bowel movement: Webster 2007 for the intervention group, Chou 2006 for the control group) |

| Ray 2008 | Time to first flatus and time to first bowel movement assumed to be reported as a mean. Length of hospital stay reported as median (assumed to be mean for analyses). Standard deviation estimations assumed from the most conservative reliable value within the other surgery subgroup (time to first flatus: Park 2009 for the intervention group, Schweizer 2010 for the control group; time to first bowel movement: Webster 2007 for the intervention group, Chou 2006 for the control group; length of hospital stay: Schweizer 2010 for both intervention and control groups). Number of participants per group not specifically stated; numbers used in analyses assumed from the text |

| Safdari‐Dehcheshmehi 2011 | Time to first defaecation and time to first bowel movement reported. Time to first defaecation results used in this review as reviewers anticipated that bowel movement was likely to occur after passage of flatus, and the results for time to first defaecation fitted this criterion whereas results for time to first bowel movement did not. Additionally there may have been a translation error in definition for 'time to first bowel movement' in the manuscript, as this study was translated from Farsi |

| Satij 2006 | Results reported as 'time to bowel function', defined as either passing flatus or a bowel movement; assumed to be time to flatus in this review |

| Schluender 2005 | Time to first flatus, time to first bowel movement and length of hospital stay reported as a mean. Study data from laparoscopic and open surgery subgroups combined to provide mean values for one intervention and one control group, standard deviation estimations assumed from the most conservative reliable value within the colorectal surgery subgroup (time to first flatus: Forrester 2014 for both intervention and control groups; time to first bowel movement: Forrester 2014 for the intervention group, Hirayama 2006 for the control group; length of hospital stay: Bahena‐Aponte 2010 for both intervention and control groups) |

| Watson 2008 | Time to first flatus, time to first bowel movement and length of hospital stay reported as median and interquartile range (unpublished information). Range estimated. Mean and standard deviation calculated using the formulae described by Hozo 2005 |

| Yi 2013 | Length of hospital stay reported as a mean. Standard deviation estimations assumed from the most conservative reliable value within the other surgery subgroup (Schweizer 2010 for both intervention and control groups) |

| Zhao 2008 | Time to first flatus reported as a mean. Standard deviation estimations assumed from the most conservative reliable value within the other surgery subgroup (Park 2009 for the intervention group, Schweizer 2010 for the control group) |

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity across studies by visual inspection of the forest plot and using the Chi2 measurement. Heterogeneity is more difficult to detect when sample sizes and number of events are small, so we used a cut off of P < 0.01 for the Chi2 measurement to decide if there was statistical evidence of heterogeneity (Higgins 2011). As a measure of the variation in intervention effect due to statistical heterogeneity, we also assessed the I2 statistic; we considered values greater than 50% to be indicative of significant heterogeneity (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed reporting bias using funnel plots of included studies.

Data synthesis

We performed analyses in RevMan 5.3. Analyses comprised only within‐study comparisons rather than individual‐level data. Comparisons were based on an intention‐to‐treat analysis. We used a random‐effects model for the meta‐analysis of results, as there was a high level of heterogeneity among included studies. Three authors (VS, CP and RP) discussed results for each outcome measure within each study, to determine the inclusion of data in the meta‐analyses. Where data were not provided in the form of a mean and standard deviation, we derived these from the reported test statistics or estimated them from the reported data if suitable test statistics were not reported. We used the following methods to transform or estimate data:

· We estimated missing standard deviations using the most conservative reliable standard deviation from another study in the same surgical subgroup

· We considered medians as means if reported alone, and applied the most conservative reliable standard deviation from another study in the same surgical subgroup

· Where results were presented as median and range, we calculated mean and standard deviation using the formulae described by Hozo 2005

· Where complications were reported as % incidence, we converted this into the number of participants who experienced complications.

Co‐authors checked 100% of continuous outcome data entered into Revman for included studies. We assessed all of our outcomes using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) protocol and reported this in Table 1 and Table 2; we classed evidence as very low, low, moderate or high quality.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted subgroup analyses to determine the sensitivity of overall conclusions to the surgical site. The key surgical disciplines reporting trials in this research area are colorectal surgery (CRS) and caesarean section (CS); we therefore created three subgroups: ‘CRS’, ‘CS’ and ‘other surgery’ (OS).

We used meta‐regression to assess whether the overall effect size was associated with the surgical site and whether this was a source of heterogeneity between studies using the 'metareg' package for the statistical software 'Stata 13' (StataCorp 2013). We also assigned each study a ROB score based on the combination of high and unclear risks for random sequence generation, allocation concealment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting or ‘other’ types of bias (a score of one was given for each unclear risk and a score of two for each high risk). Based on the spread of ROB scores, we categorised studies into subgroups by overall score: zero to three, four to five and six to ten. We used meta‐regression to assess the association between ROB score and overall effect size and whether this was a source of heterogeneity between studies.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses based on the methodological and reporting qualities of the studies analysed. We considered the impact of methodological quality by excluding studies of lower quality, and we assessed how robust our overall results were to the use of estimates for missing data. We also explored the use of CG in an ERAS setting.

We therefore conducted the following sensitivity analyses:

We removed studies judged at ‘high risk’ of bias for at least two of the following components: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting or ‘other’ types of bias

We removed studies which did not report on complications (deemed by co‐authors to be an indicator of low quality)

We excluded studies with any estimated results

We applied less conservative methods for dealing with missing data (e.g. instead of using the most conservative standard deviations, the mean standard deviation across all reliable values in the relevant subgroup was used)

We only included studies conducted within the context of an ERAS programme.

As we observed publication bias across studies reporting TBM and LOHS, we decided to also conduct post‐hoc meta‐analyses using a fixed‐effect model.

Results

Description of studies

See tables of Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

The electronic search identified 3993 hits. We identified 60 further records through hand‐searching: 54 from Google and Google Scholar and six through scanning reference lists of included studies and relevant SRs. After screening titles and abstracts, we excluded 1962 duplicates and 1967 irrelevant records. We sought full‐texts for the remaining 124 records; upon screening we excluded a further 24 records (see Characteristics of excluded studies). One hundred publications met the full inclusion criteria, of which 19 were subsequently found to be duplicate publications. We therefore identified 81 unique studies for inclusion comprising 9072 participants, as shown in Figure 1.

Included studies

We included 81 studies (see Characteristics of included studies). For 10 studies reported in multiple publications, we used the reference that provided the most comprehensive information (Abdollahi 2013; Asao 2002; Forrester 2014; Huang 2012a; Ledari 2012; Lim 2013; Matros 2006; McCormick 2005; Ren 2010; Schuster 2006).

Twelve studies were published as abstracts (Atkinson 2014; Garshasbi 2011; Lee 2004; Lu 2011; McCormick 2005; Ray 2008; Satij 2006; Schluender 2005; Schweizer 2010; Watson 2008; Webster 2007; Zamora 2012). We could obtain one publication only in part (Jin 2010). We sought extra information for 22 studies; unpublished data were provided for 11 (Atkinson 2014; Bonventre 2014; Ertas 2013; Jernigan 2014; Lim 2013; Matros 2006; McCormick 2005; Satij 2006; Schweizer 2010; Watson 2008; Zamora 2012) (see Characteristics of included studies).

Studies were conducted in 20 countries. Multiple trials were identified from the following countries: 35 in China (Cao 2008; Chen 2010; Chen 2011; Chen 2012; Fan 2009; Gong 2011; Guangqing 2011; Han 2011; Huang 2012a; Huang 2012b; Jin 2010; Li 2007a; Li 2012a; Li 2012b; Liang 2007; Lu 2010a; Lu 2010b; Lu 2011; Luo 2010; Qiao 2011; Qiu 2006; Ren 2010; Shang 2010; Sun 2005; Tan 2011; Tian 2013; Wang 2008; Wang 2009a; Wang 2011a; Wang 2011b; Yang 2011; Yi 2013; Zhang 2008; Zhao 2008; Zhong 2009), 12 in the USA (Crainic 2009; Forrester 2014; Jernigan 2014; Lee 2004; Matros 2006; McCormick 2005; Ray 2008; Satij 2006; Schluender 2005; Schuster 2006; Webster 2007; Zaghiyan 2013), eight in Iran (Abdollahi 2013; Akhlaghi 2008; Askarpour 2009; Garshasbi 2011; Ghafouri 2008; Ledari 2012; Pilehvarzadeh 2014; Safdari‐Dehcheshmehi 2011), four in Turkey (Çavuşoğlu 2009; Ertas 2013; Kafali 2010; Terzioglu 2013), three in Korea (Choi 2011; Choi 2014; Park 2009), three in the UK (Atkinson 2014; Quah 2006; Watson 2008), two in Japan (Asao 2002; Hirayama 2006) and two in Thailand (Chuamor 2014; Jakkaew 2013).

We identified only four paediatric studies (Çavuşoğlu 2009; Yang 2011; Zhang 2008; Zhao 2008). Studies applied various exclusion criteria, commonly postoperative complications, previous abdominal/bowel surgery, inability to chew gum and co‐morbidities (including chronic constipation, diabetes, pre‐eclampsia/eclampsia, hypothyroidism and pancreatitis).

One study used sugared gum for the intervention (Zaghiyan 2013); all other studies did not specify or used sugar‐free/sugar‐less gum. Ten studies included placebo or alternative treatment groups alongside a control group. Placebo interventions were sucking hard candy (Crainic 2009) and wearing a silicone‐adhesive patch (Forrester 2014) or an acupressure wrist bracelet (Matros 2006). Alternative treatments were early ambulation and sphincter exercises (Huang 2012a), stomach massage (Lu 2010a), chewing green tea leaves (Zhong 2009), early oral feeding (Safdari‐Dehcheshmehi 2011), laxatives or early feeding (Askarpour 2009), combinations of early oral hydration and early mobilisation (Terzioglu 2013) or combinations of olive oil and water (Bonventre 2014).

Controls received either standard care or a similar care regimen to the intervention group in 52 studies. Four studies were conducted in the context of an ERAS programme (Atkinson 2014; Lim 2013; Watson 2008; Zaghiyan 2013). Fourteen either did not specify or stated that the control group did not chew gum or receive GI stimulants or special treatment (Abdollahi 2013; Cabrera 2012; Choi 2014; Chou 2006; Crainic 2009; Garshasbi 2011; Lee 2004; Liang 2007; Lu 2011; Park 2009; Qiu 2006; Satij 2006; Schluender 2005; Zhang 2008). The control group underwent mobilisation protocols in four studies (Chen 2011; Huang 2012b; Wang 2008; Yi 2013). The control group had sips of clear liquid in one study (McCormick 2005), two studies created their own control group protocol (Akhlaghi 2008; Terzioglu 2013), and controls were nil‐by‐mouth in four studies (Abd‐El‐Maeboud 2009; Askarpour 2009; Marwah 2012; Shang 2010).

Eight studies reported results in subgroups by surgical site (Abdollahi 2013; Bonventre 2014; Schweizer 2010) or surgical approach: open and robot‐assisted (Choi 2011) or open and laparoscopic (Crainic 2009; Lim 2013; McCormick 2005; Schluender 2005). Zaghiyan 2013 conducted age and operative time subgroup analyses following identification of baseline differences.

Of our outcomes, TFF was most commonly reported, followed by TBM, LOHS, tolerability of gum, TBS, complications and cost. Other than these, the most frequently reported outcome was time to first food consumption. Additional reported outcomes included blood catecholamines (Zhang 2008; Zhao 2008), blood motilin (Guangqing 2011; Wang 2011b), blood/serum gastrin (Chen 2010; Zhang 2008; Zhao 2008), blenching (Chuamor 2014), analgesic use (Ertas 2013; Husslein 2013; Kafali 2010), antiemetic use (Ertas 2013; Kafali 2010), time to tolerance or first oral fluids (Crainic 2009; Watson 2008), tolerance of first meal (Jakkaew 2013), time to first hunger (Fan 2009; Forrester 2014; Jakkaew 2013; Ledari 2012; Marwah 2012; McCormick 2005; Schuster 2006), discomfort (Huang 2012a), pain (Lim 2013; Lu 2011), time until ready for discharge (Matros 2006) and time to feeling first intestinal movement (Rashad 2013).

Excluded studies

Upon reading the full texts where possible, we excluded 24 records (see Characteristics of excluded studies). Thirteen were not RCTs (Anon 2006b; Anon 2006c; Anon 2008; Chathongyot 2010; Darvall 2011; Harma 2009; Hwang 2013; Keenahan 2014; Kim 2010; Nimarta 2013; Slim 2014; Takagi 2012; Utli 2013), we could not source eight (Alcántara 2010; Alper 2006; Anon 2006a; Duluklu 2012; Li 2007b; Starly 2009; Wang 2003; Wang 2009b), two described a non‐postoperative intervention (Apostolopoulos 2008; Svarta 2012) and one was incomplete (reported in the Ongoing studies section) (van Leersum 2012).

We identified a further 15 ongoing trials that could not be included in this review (see Ongoing studies). Seven were complete but not yet published (Abd‐El‐Maeboud 2010; Andersson 2011; Clark 2008; Fakari 2011; Lopez 2012; Lv 2011; Sabo 2012).

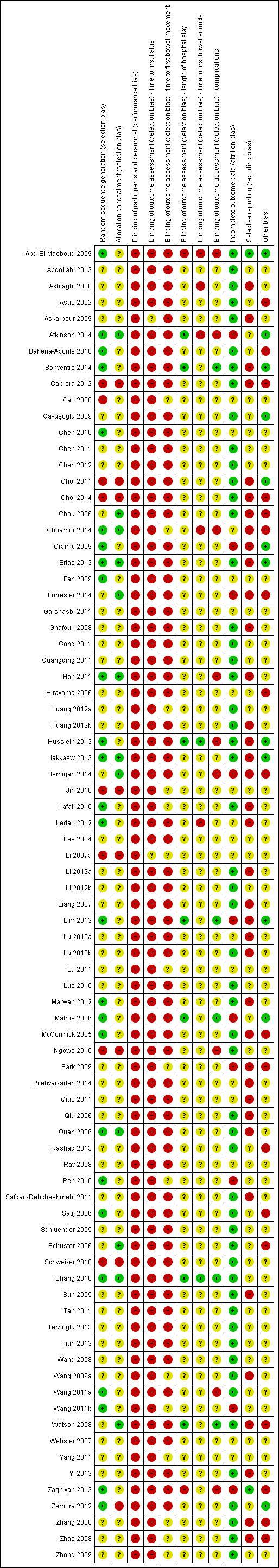

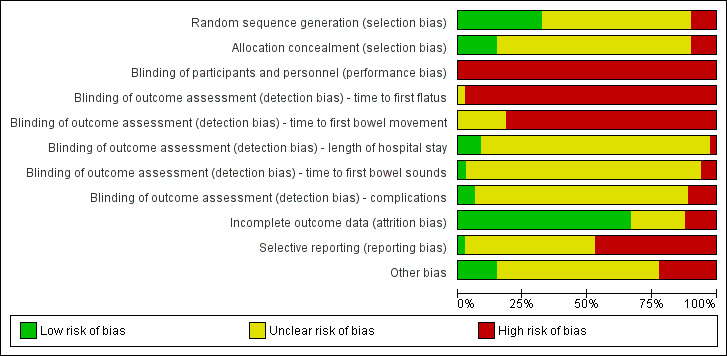

Risk of bias in included studies

ROB for each study is described in detail in the Characteristics of included studies section. Details of ROB judgements for each study are presented in Figure 2, with an overall summary graph in Figure 3. The largest ROB was reporting bias due to Selective reporting (reporting bias). The smallest ROB was attrition bias due to Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias). Allocation concealment methods were most poorly reported, resulting in the greatest number of 'unclear' ROB assessments [see Allocation (selection bias)].

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

We categorised 26 studies at low ROB due to acceptable randomisation sequence generation through use of computer‐generated randomisation, a random number table, a draw or an online program (Abd‐El‐Maeboud 2009; Atkinson 2014; Bahena‐Aponte 2010; Bonventre 2014; Chen 2010; Chuamor 2014; Crainic 2009; Ertas 2013; Fan 2009; Han 2011; Husslein 2013; Jakkaew 2013; Kafali 2010; Ledari 2012; Lim 2013; Marwah 2012; Matros 2006; McCormick 2005; Quah 2006; Ren 2010; Satij 2006; Shang 2010; Wang 2011a; Wang 2011b; Zaghiyan 2013; Zamora 2012).

We classed eight studies at high ROB through inadequate random sequence generation. Methods used included randomisation by order of hospital admission (Cabrera 2012; Cao 2008), hospital bed number (Li 2007a), operating time (Jin 2010), alternate randomisation (Choi 2011; Ngowe 2010), allocation by an investigator (Choi 2014) or allocation by participant preference (Schweizer 2010). We categorised all other studies at unclear ROB.

Allocation concealment

We considered 12 studies to be at low ROB due to adequate allocation concealment methods. Methods included sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes, a sequential card‐pull design, an Access database or central telephone assignment (Atkinson 2014; Chou 2006; Chuamor 2014; Ertas 2013; Forrester 2014; Han 2011; Jakkaew 2013; Jernigan 2014; Quah 2006; Schuster 2006; Shang 2010; Watson 2008). We classed eight studies at high ROB due to inadequate methods for allocation concealment (Cabrera 2012; Choi 2011; Choi 2014; Jin 2010; Li 2007a; Ngowe 2010; Schweizer 2010; Zamora 2012). We classed all remaining studies at unclear ROB.

Blinding

Participants

Participants cannot be adequately blinded with this intervention, therefore we judged all studies to be at high ROB.

Personnel

Personnel were not blinded in four studies (Abd‐El‐Maeboud 2009; Ertas 2013; Jernigan 2014; Zaghiyan 2013). Eight studies described methods used to blind some personnel (Atkinson 2014; Bonventre 2014; Choi 2011; Choi 2014; Lim 2013; Matros 2006; Shang 2010; Watson 2008) and three studies reported personnel blinding but did not describe methods used (Çavuşoğlu 2009; Han 2011; Schluender 2005). No other studies discussed personnel blinding.

Outcome assessment

We considered TFF and TBM as participant‐reported outcomes, therefore we judged all studies reporting these outcomes at high ROB. One study described TFF and TBM with a stoma, which could have been reported by staff (Quah 2006). However, as 45% of participants in this study did not have a stoma placed, we also categorised this study at high ROB.

We assumed that staff reported LOHS (as it is likely to have been taken from medical notes or administration records). We judged two studies at high ROB: authors stated that blinding of outcome assessment was not possible (Abd‐El‐Maeboud 2009; Zaghiyan 2013). We classed seven studies at low ROB, where participants or ward staff were taught not to reveal group allocation to outcome assessors (Atkinson 2014; Bonventre 2014; Husslein 2013; Lim 2013; Matros 2006; Shang 2010; Watson 2008), participants hid gum (Husslein 2013; Matros 2006; Shang 2010), containers for gum disposal were provided (Lim 2013), concealed charts identifying intervention participants (for nurses) were kept in patient records (Lim 2013), or clinical rounds and CG periods were separated (Bonventre 2014; Husslein 2013; Matros 2006). We classed all other studies at unclear ROB, as methods for blinding of outcome assessment were not discussed.

We assumed that staff reported TBS (unless otherwise stated). We classed five studies as at high ROB where authors reported that blinding of staff was not possible (Abd‐El‐Maeboud 2009; Atkinson 2014), TBS was participant‐reported (Akhlaghi 2008; Ledari 2012) or investigators providing the gum assessed TBS (Chuamor 2014). We classed two studies at low ROB (same methods used for LOHS assessment) (Husslein 2013; Shang 2010). We classed all other studies at unclear ROB.

Complications were reported by participants or staff. We classed nine studies at high ROB where complications were participant‐reported or staff were not blinded or inadequately blinded (Abd‐El‐Maeboud 2009; Atkinson 2014; Chuamor 2014; Han 2011; Husslein 2013; Jernigan 2014; Ngowe 2010; Wang 2011a; Zaghiyan 2013). We categorised five studies at low ROB (same methods used for LOHS assessment) (Bonventre 2014; Lim 2013; Matros 2006; Shang 2010; Watson 2008). We classed all other studies at unclear ROB.

ROB through blinding of assessment of tolerability of gum was not reported as this was not possible nor relevant to both groups. Additionally, ROB for assessment of cost was not reported as we considered blinding to have had little effect.

Incomplete outcome data

We judged ROB as high in 10 studies. One had a greater than 10% difference in missing data between groups (Zaghiyan 2013). One stated use of intention‐to‐treat analyses, but only 157 of 168 participants were included in analyses (Lim 2013). Eight reported more than 10% missing data for an outcome of interest (Atkinson 2014; Crainic 2009; Forrester 2014; Jernigan 2014; Matros 2006; Park 2009; Ren 2010; Wang 2011b).

Sixteen studies did not state the number of participants included in analyses (Cao 2008; Chen 2010; Chuamor 2014; Fan 2009; Garshasbi 2011; Hirayama 2006; Jin 2010; Lee 2004; Li 2007a; Lu 2010a; Lu 2011; Pilehvarzadeh 2014; Qiao 2011; Ray 2008; Webster 2007; Yang 2011) and one study reported a 9% attrition rate of randomised participants, but did not state to which group(s) they had been allocated (Ledari 2012). We considered these to be at unclear ROB. We classed all remaining studies at low ROB.

Selective reporting

We judged two studies to be at low ROB, where all outcomes pre‐specified in the available protocol were reported in the publication (Abd‐El‐Maeboud 2009; Zaghiyan 2013).

We classed 38 studies at high ROB. Six studies deviated in outcome reporting from pre‐specifications in the protocol (Bonventre 2014; Ertas 2013; Husslein 2013; Jernigan 2014; Lim 2013; Safdari‐Dehcheshmehi 2011). Five studies did not pre‐specify any outcomes in the publication (Askarpour 2009; Li 2012a; Lu 2010b; Sun 2005; Wang 2009a). In 27 studies data pre‐specified as an outcome measure or collected as part of the research methodology were not presented fully, or outcome reporting deviated from pre‐specifications in the publication (Akhlaghi 2008; Cabrera 2012; Choi 2011; Choi 2014; Chou 2006; Chuamor 2014; Crainic 2009; Forrester 2014; Ghafouri 2008; Han 2011; Huang 2012b; Jakkaew 2013; Kafali 2010; Ledari 2012; Liang 2007; Lu 2010a; Marwah 2012; McCormick 2005; Park 2009; Pilehvarzadeh 2014; Qiao 2011; Qiu 2006; Quah 2006; Watson 2008; Yi 2013; Zhang 2008; Zhao 2008).

We classed all other studies at unclear ROB. We categorised studies that were reported only as abstracts as unclear so as not to penalise for exclusion of information within the confines of an abstract.

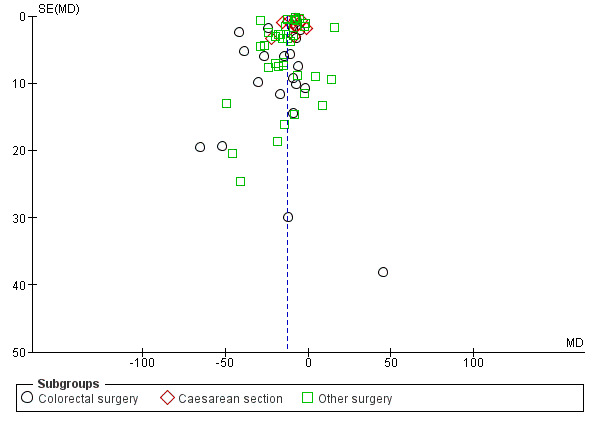

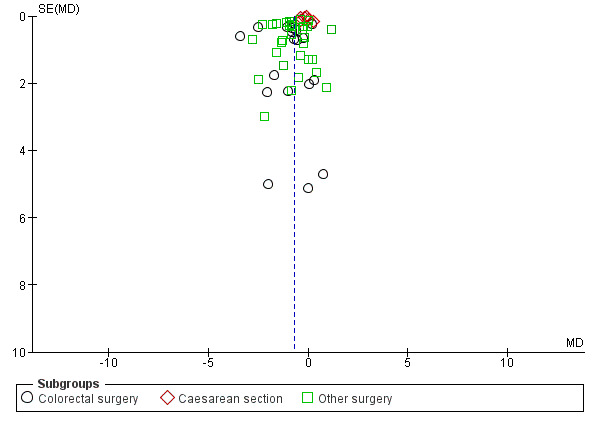

Visual inspection of the funnel plots for each continuous outcome indicated that reporting bias may be present for TBM and LOHS.

Other potential sources of bias

We detected three additional potential biases:

Baseline differences between groups. Onset and duration of ileus are considered to be multifactorial, hence some baseline differences between groups could introduce bias. We classed six studies at high ROB due to significant baseline differences in age (Park 2009), operative time (Rashad 2013), age and operative time (Zaghiyan 2013), operative blood loss (Chuamor 2014), BMI, ethnicity and use of epidural (Jernigan 2014) and BMI, stoma creation and pain relief (Watson 2008). Zaghiyan 2013 conducted further subgroup analyses to explore the implications of the identified baseline differences in age and operative time.

We considered sample sizes that were more than 10% below the sample size calculations, or which were likely to be too small to adequately test the research question, to be at high ROB. We considered 20 participants per arm as an arbitrary value for acceptable sample sizes; we classed 11 studies at high ROB with sample sizes less than 20 per arm (Asao 2002; Bahena‐Aponte 2010; Cabrera 2012; Choi 2014; Chou 2006; Hirayama 2006; Park 2009; Satij 2006; Schuster 2006; Zhang 2008; Zhao 2008). We classed 12 studies at low ROB where sample sizes were within 10% of the calculated sample size requirement (Abd‐El‐Maeboud 2009; Atkinson 2014; Bonventre 2014; Çavuşoğlu 2009; Choi 2011; Crainic 2009; Ertas 2013; Husslein 2013; Jakkaew 2013; Lim 2013; Matros 2006; Zamora 2012); three futher studies met the calculated sample size requirement (within 10%) but were still judged at high risk due to baseline differences between groups (Chuamor 2014; Watson 2008; Zaghiyan 2013). We classed two studies at high ROB where sample size requirements more than 10% below the sample size calculations (Forrester 2014; Jernigan 2014).

Non‐specified differences in randomisation to treatment groups. We decided that a greater than 10% difference in randomisation to each arm, which was not pre‐specified, constituted a ROB. Two studies were classed at high ROB due to a 17% and 34% difference in randomisation between groups (Hirayama 2006; McCormick 2005).

We judged all other studies at unclear ROB for these additional potential biases.

Effects of interventions

Evidence for effects of interventions are summarised in the Table 1 and Table 2.

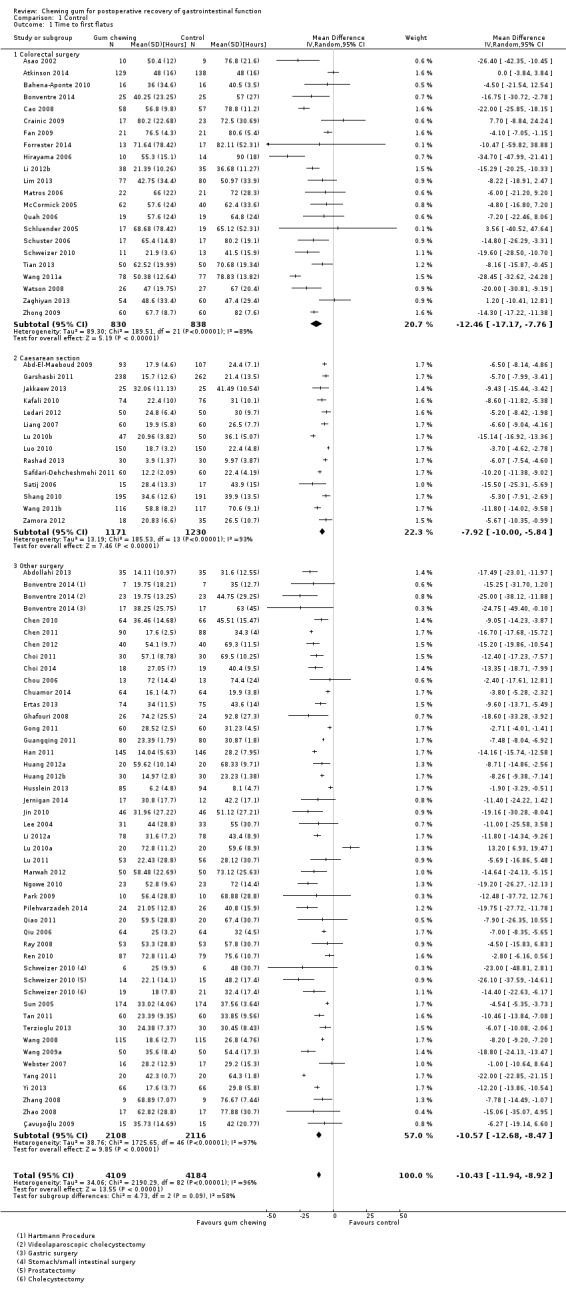

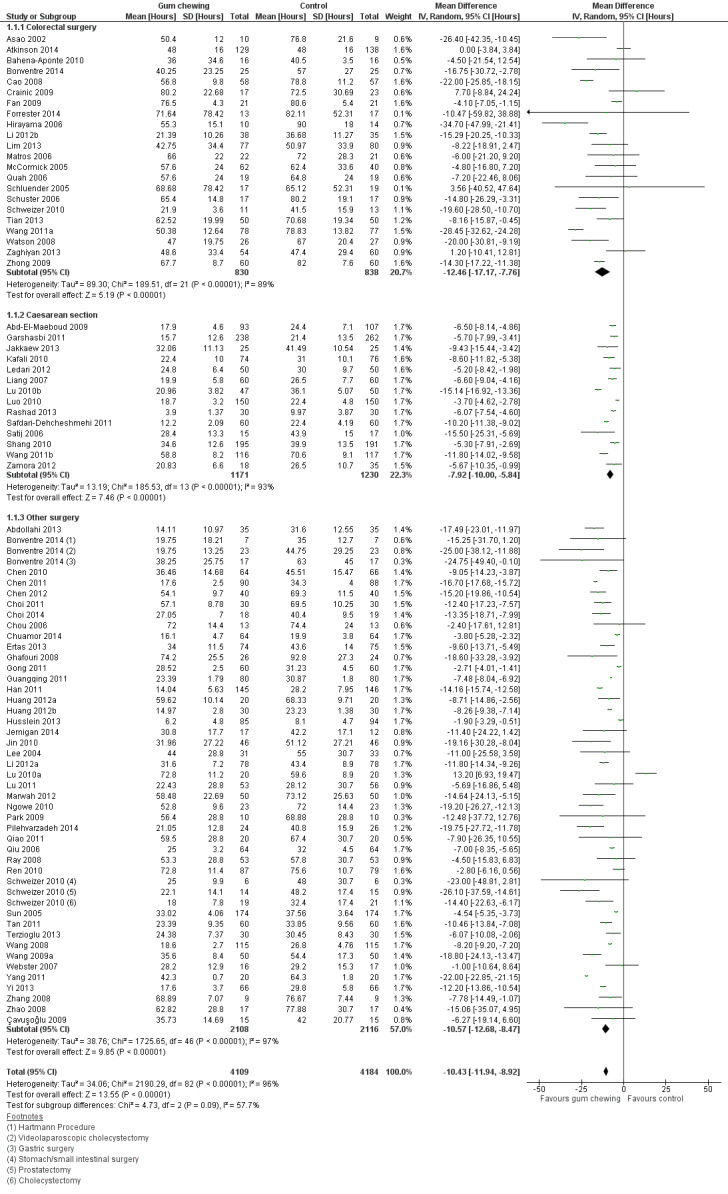

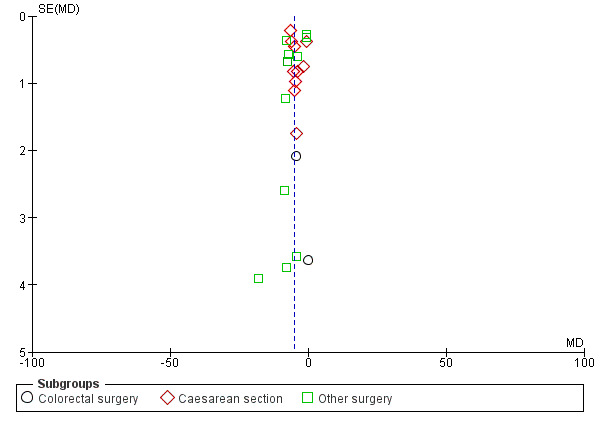

Time to first flatus

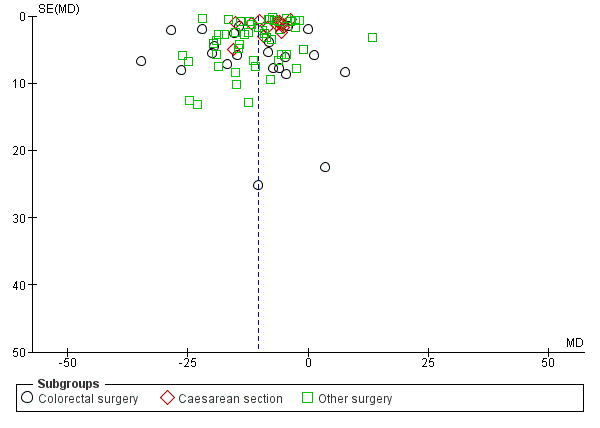

A reduction in TFF with postoperative CG was observed across subgroups. The overall combined analysis of 8239 participants from 77 studies showed a reduction of 10.4 hours (95% CI ‐11.9, ‐8.9) (see Analysis 1.1, Figure 4). In the CRS subgroup, analysis of 1668 participants from 22 studies showed a reduction of 12.5 hours (95% CI ‐17.2, ‐7.8). In the CS subgroup, analysis of 2401 participants from 14 studies showed a reduction of 7.9 hours (95% CI –10.0, ‐5.8). In the OS subgroup, analysis of 4224 participants from 43 studies showed a reduction of 10.6 hours (95% CI ‐12.7, ‐8.5). There was evidence of statistical heterogeneity between studies in all analyses (overall: I2 = 96%, P < 0.001, CRS: I2 = 89%, P < 0.001, CS: I2 = 93%, P < 0.001, OS: I2 = 97%, P < 0.001). Visual inspection of the funnel plot did not indicate the presence of publication bias (see Figure 5). Post‐hoc meta‐analyses using a fixed‐effect model showed a reduced effect estimate, but no difference in direction of effect [overall reduction of 9.1 hours (95% CI ‐9.3, ‐8.8), CRS: reduction of 12.5 hours (95% CI ‐13.9, ‐11.2), CS: overall reduction of 7.2 hours (95% CI ‐7.7, ‐6.7), OS: overall reduction of 9.5 hours (95% CI ‐9.8, ‐9.2)] (see Appendix 8).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Control, Outcome 1 Time to first flatus.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Control, outcome: 1.1 Time to first flatus [Hours].

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Control, outcome: 1.1 Time to first flatus [Hours].

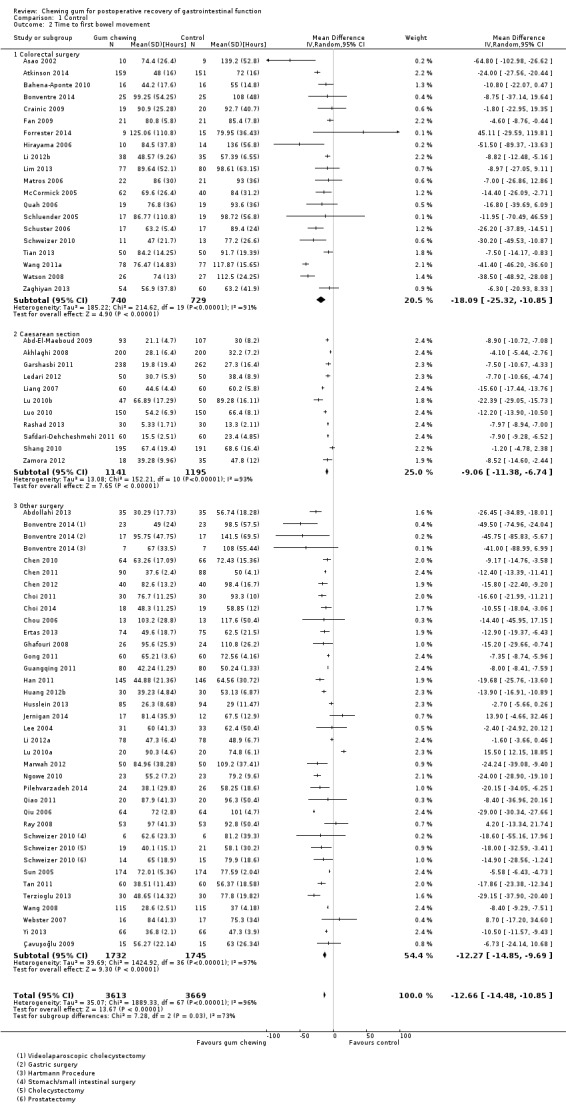

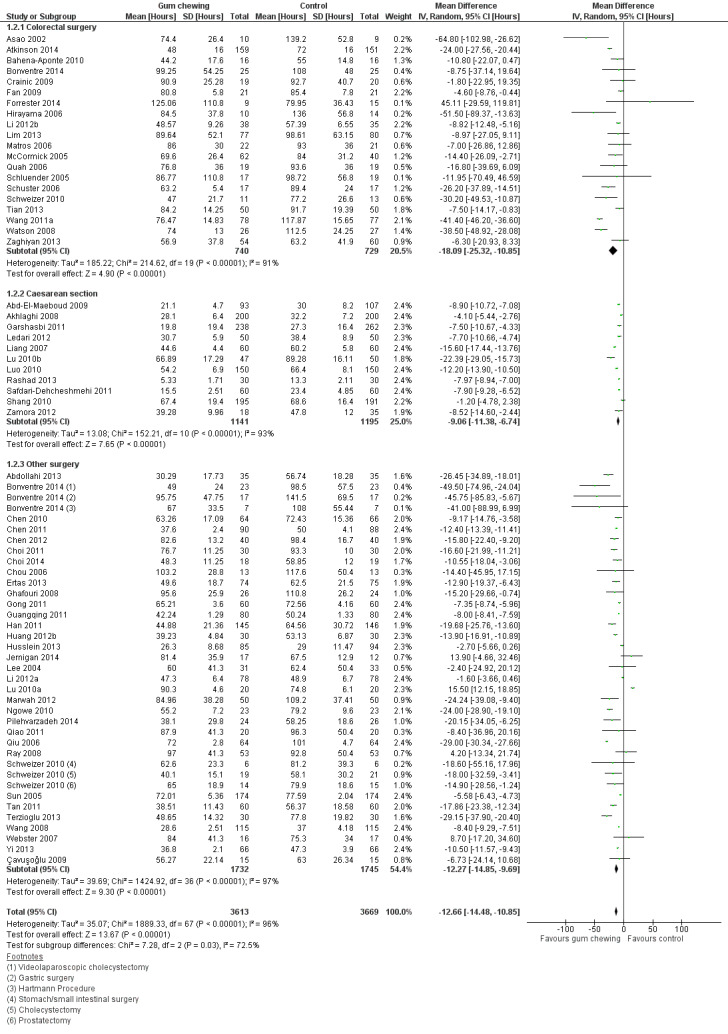

Time to first bowel movement

A reduction in TBM with postoperative CG was observed across subgroups. The overall combined analysis of 7282 participants from 62 studies showed a reduction of 12.7 hours (95% CI ‐14.5, ‐10.9) (see Analysis 1.2, Figure 6). In the CRS subgroup, analysis of 1470 participants from 20 studies showed a reduction of 18.1 hours (95% CI ‐25.3, ‐10.9). In the CS subgroup, analysis of 2336 participants from 11 studies showed a reduction of 9.1 hours (95% CI ‐11.4, ‐6.7). In the OS subgroup, analysis of 3477 participants from 33 studies showed a reduction of 12.3 hours (95% CI ‐14.9, ‐9.7). There was evidence of statistical heterogeneity between studies in all analyses (overall: I2 = 96%, P < 0.001, CRS: I2 = 91%, P < 0.001, CS: I2 = 93%, P < 0.001, OS: I2 = 97%, P < 0.001). Visual inspection of the funnel plot indicated that publication bias may be present (see Figure 7). Post‐hoc meta‐analyses using a fixed‐effect model showed a reduced effect estimate, but no difference in direction of effect [overall reduction of 9.2 hours (95% CI ‐9.4, ‐8.9), CRS: reduction of 17.6 (95% CI ‐19.4, ‐15.9), CS: overall reduction of 8.4 hours (95% CI ‐9.0, ‐7.9), OS: overall reduction of 9.2 hours (95% CI ‐9.4, ‐8.9)] (see Appendix 8).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Control, Outcome 2 Time to first bowel movement.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Control, outcome: 1.2 Time to first bowel movement [Hours].

7.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Control, outcome: 1.2 Time to first bowel movement [Hours].

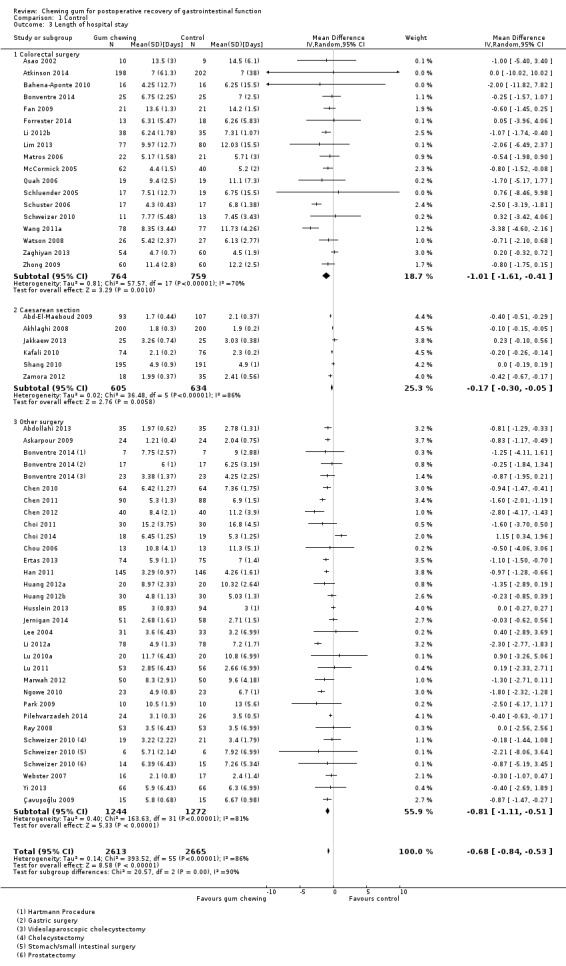

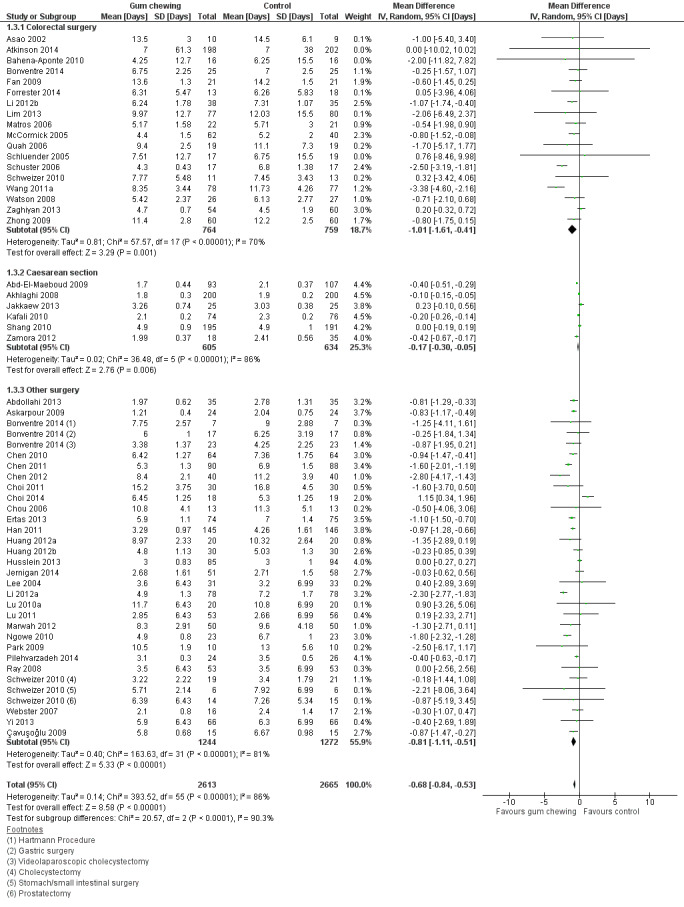

Length of hospital stay

A reduction in LOHS with postoperative CG was observed across subgroups. The overall combined analysis of 5278 participants from 50 studies showed a reduction of 0.7 days (95% CI ‐0.8, ‐0.5) (see Analysis 1.3, Figure 8). In the CRS subgroup, analysis of 1523 participants from 18 studies showed a reduction of 1.0 days (95% CI ‐1.6, ‐0.4). In the CS subgroup, analysis of 1239 participants from 6 studies showed a reduction of 0.2 days (95% CI ‐0.3, ‐0.1). In the OS subgroup, analysis of 2516 participants from 28 studies showed a reduction of 0.8 days (95% CI ‐1.1, ‐0.5). There was evidence of statistical heterogeneity between studies in all analyses (overall: I2 = 86%, P < 0.001, CRS: I2 = 70%, P < 0.001, CS: I2 = 86%, P < 0.001, OS: I2 = 81%, P < 0.001). Visual inspection of the funnel plot indicated that publication bias may be present (see Figure 9). Post‐hoc meta‐analyses using a fixed‐effect model showed a reduced effect estimate, but no difference in direction of effect [overall reduction of 0.2 days (95% CI ‐0.3, ‐0.2), CRS: reduction of 0.9 days (95% CI ‐1.2, ‐0.6), CS: overall reduction of 0.2 days (95% CI ‐0.2, ‐0.1), OS: overall reduction of 0.7 (95% CI ‐0.8, ‐0.6)] (see Appendix 8).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Control, Outcome 3 Length of hospital stay.

8.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Control, outcome: 1.3 Length of hospital stay [Days].

9.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Control, outcome: 1.3 Length of hospital stay [Days].

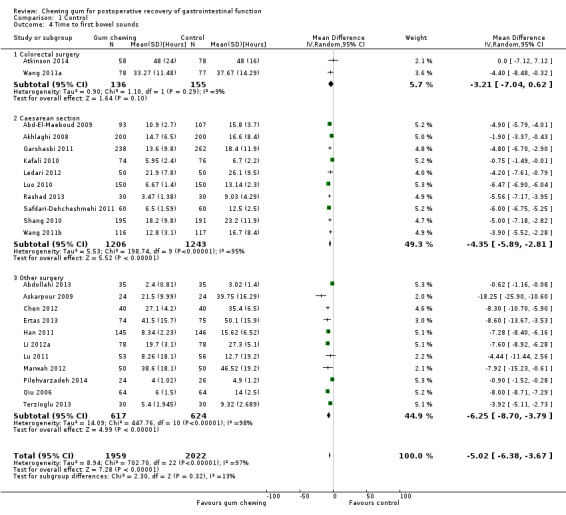

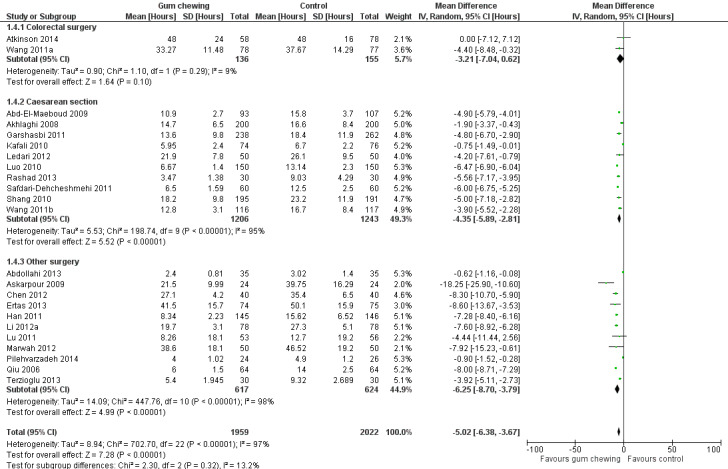

Time to first bowel sounds

A reduction in TBS with postoperative CG was observed across subgroups. The overall combined analysis of 3981 participants from 23 studies showed a reduction of 5.0 hours (95% CI ‐6.4, ‐3.7) (see Analysis 1.4, Figure 10). In the CRS subgroup, analysis of 291 participants from 2 studies showed a reduction of 3.2 hours (95% CI ‐7.0, 0.6). In the CS subgroup, analysis of 2449 participants from 10 studies showed a reduction of 4.4 hours (95% CI ‐5.9, ‐2.8). In the OS subgroup, analysis of 1241 participants from 11 studies showed a reduction of 6.3 hours (95% CI ‐8.7, ‐3.8). There was evidence of statistical heterogeneity between studies in all analyses other than CRS (as only two studies were included) (overall: I2 = 97%, P < 0.001, CRS: I2 = 9%, P = 0.29, CS: I2 = 95%, P < 0.001, OS: I2 = 98%, P < 0.001). Visual inspection of the funnel plot did not indicate the presence of publication bias (see Figure 11). Post‐hoc meta‐analyses using a fixed‐effect model showed a reduced effect estimate, but no difference in direction of effect [overall reduction of 4.3 hours (95% CI ‐4.5, ‐4.1), CRS: reduction of 3.3 hours (95% CI ‐6.9, 0.2), CS: overall reduction of 5.0 hours (95% CI ‐5.3, ‐4.7), OS: overall reduction of 3.4 hours (95% CI ‐3.7, ‐3.1)] (see Appendix 8).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Control, Outcome 4 Time to first bowel sounds.

10.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Control, outcome: 1.4 Time to first bowel sounds [Hours].

11.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Control, outcome: 1.4 Time to first bowel sounds [Hours].

Complications

We reported nausea and vomiting, mortality, infection, readmissions, other complications, and complications related to the intervention.

Fifteen studies reported nausea and vomiting (six CRS, four CS, five OS) (see Analysis 1.5). Similar prevalence of nausea and vomiting were observed between groups in five CRS and three CS studies (Abd‐El‐Maeboud 2009; Atkinson 2014; Hirayama 2006; Jakkaew 2013; Lim 2013; Zaghiyan 2013; Zamora 2012; Zhong 2009). Nausea and vomiting reports were lower in the intervention group in one CRS, one CS and all five OS studies (Askarpour 2009; Han 2011; Jernigan 2014; Kafali 2010; Li 2012a; Marwah 2012; Wang 2011a).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Control, Outcome 5 Complications ‐ Nausea and Vomiting [Frequency].

| Complications ‐ Nausea and Vomiting [Frequency] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Intervention group | Control group |

| Colorectal surgery | ||

| Atkinson 2014 | 36 (vomiting on postoperative day 2, recorded for only 196 of 198 participants in the intervention group) | 34 (vomiting on postoperative day 2, recorded for all 202 participants in the control group) |

| Hirayama 2006 | 0 | 2 |

| Lim 2013 | 100 | 97 |

| Wang 2011a | 24 | 36 |

| Zaghiyan 2013 | 3 | 6 |

| Zhong 2009 | 22 | 21 |

| Caesarean section | ||

| Abd‐El‐Maeboud 2009 | 1 | 3 |

| Jakkaew 2013 | 2 | 3 |

| Kafali 2010 | 2 | 10 |

| Zamora 2012 | 0 ‐ no recorded postoperative ileus symptoms (such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension and diarrhoea) | 0 ‐ no recorded postoperative ileus symptoms (such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension and diarrhoea) |

| Other surgery | ||

| Askarpour 2009 | 0 | 4 |

| Han 2011 | 5 | 17 |

| Jernigan 2014 | 22 | 39 |

| Li 2012a | 20 | 33 |

| Marwah 2012 | 14 | 25 |

Seven studies reported mortality (five CRS, two OS) (details presented in Analysis 1.6). Four CRS and both OS studies reported either no or one death, with no differences between groups (Bahena‐Aponte 2010; Çavuşoğlu 2009; Lim 2013; Marwah 2012; Quah 2006; Watson 2008). One CRS study reported 11 deaths in the intervention group and none in the control group (Atkinson 2014); authors have however confirmed that mortality was not judged to be related to the intervention in these cases.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Control, Outcome 6 Complications ‐ Mortality [Frequency].

| Complications ‐ Mortality [Frequency] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Intervention group | Control group |

| Colorectal surgery | ||

| Atkinson 2014 | 11 ‐ 9 prior to 12‐week follow‐up, 2 after 12‐week follow‐up | 0 |

| Bahena‐Aponte 2010 | 0 | 0 |

| Lim 2013 | 0 | 1 ‐ 30 day mortality |

| Quah 2006 | 1 | 0 |

| Watson 2008 | 0 | 1 |

| Other surgery | ||

| Marwah 2012 | 0 | 0 |

| Çavuşoğlu 2009 | 0 | 0 |

Thirteen studies reported on infections (six CRS, one CS, six OS) (details presented in Analysis 1.7). No studies found any clinically important differences between groups in reports of infections (Abd‐El‐Maeboud 2009; Asao 2002; Çavuşoğlu 2009; Chou 2006; Hirayama 2006; Marwah 2012; Matros 2006; Ngowe 2010; Park 2009; Quah 2006; Watson 2008; Zaghiyan 2013; Zhang 2008).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Control, Outcome 7 Complications ‐ Infection [Frequency].

| Complications ‐ Infection [Frequency] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Intervention group | Control group |

| Colorectal surgery | ||

| Asao 2002 | 0 | 0 |

| Hirayama 2006 | 2 ‐ wound infection | 4 ‐ wound infection |

| Matros 2006 | 0 ‐ in hospital, 2 ‐ within 30 days wound infection and intra‐abdominal abscess | 2 ‐ in hospital wound infection and pneumonia, 4 ‐ within 30 days wound infection, pneumonia and intra‐abdominal abscess |

| Quah 2006 | 2 ‐ wound infection | 2 ‐ chest infection and urinary tract infection |

| Watson 2008 | 1 ‐ wound infection | 4 ‐ wound infection and MRSA |

| Zaghiyan 2013 | 1 ‐ wound infection/pelvic abscess | 1 ‐ abdominal abscess |

| Caesarean section | ||

| Abd‐El‐Maeboud 2009 | 7 ‐ febrile morbidity | 10 ‐ febrile morbidity |

| Other surgery | ||

| Chou 2006 | 1 ‐ pneumonia | 0 |

| Marwah 2012 | 3 ‐ purulent wound discharge | 3 ‐ purulent wound discharge and pneumonitis |

| Ngowe 2010 | 3 ‐ parietal sepsis | 2 ‐ parietal sepsis |

| Park 2009 | 0 ‐ no postoperative complications such as postoperative infection or haemorrhage | 0 ‐ no postoperative complications such as postoperative infection or haemorrhage |

| Zhang 2008 | 0 | 0 |

| Çavuşoğlu 2009 | 0 | 2 ‐ intra‐abdominal abscess and superficial surgical site infection |

Twelve studies reported readmissions (seven CRS, five OS) (details presented in Analysis 1.8). One CRS and four OS studies reported no readmissions in either study arm (Choi 2014; Ertas 2013; Husslein 2013; Schuster 2006; Zhang 2008). Six CRS and one OS study reported no difference in readmissions between groups (Asao 2002; Jernigan 2014; Lim 2013; Matros 2006; Quah 2006; Watson 2008; Zaghiyan 2013).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Control, Outcome 8 Complications ‐ Readmissions [Frequency].

| Complications ‐ Readmissions [Frequency] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Intervention group | Control group |

| Colorectal surgery | ||

| Asao 2002 | 0 | 1 ‐ due to ileus, 2 days post‐discharge |

| Lim 2013 | 6 | 6 |

| Matros 2006 | 1 ‐ due to ileus, within 30 days | 2 ‐ due to ileus, within 30 days |

| Quah 2006 | 0 | 1 ‐ within 30 days |

| Schuster 2006 | 0 | 0 |

| Watson 2008 | 1 ‐ due to abdominal abscess, within 30 days | 0 |

| Zaghiyan 2013 | 0 | 2 ‐ due to ileus, within 30 days |

| Other surgery | ||

| Choi 2014 | 0 | 0 |

| Ertas 2013 | 0 | 0 |

| Husslein 2013 | 0 | 0 |

| Jernigan 2014 | 2 ‐ within 30 days | 3 ‐ within 30 days |

| Zhang 2008 | 0 | 0 |

Fifty‐four studies reported on other types of complications (including halitosis, dry mouth, bloating, oral ulcers, intestinal obstruction and anastomotic leak) (see Analysis 1.9). Eight studies reported none in either group (Abdollahi 2013; Asao 2002; Bonventre 2014; Li 2012b; Ngowe 2010; Park 2009; Zamora 2012; Zhang 2008). Three reported none in the intervention group but no information for the control group (Gong 2011; Huang 2012b; Qiu 2006). Markedly higher numbers of other complications were reported in the control group in four CRS, six CS and 11 OS studies (Abd‐El‐Maeboud 2009; Chen 2012; Ertas 2013; Garshasbi 2011; Guangqing 2011; Han 2011; Huang 2012a; Husslein 2013; Jin 2010; Kafali 2010; Liang 2007; Li 2012a; Luo 2010; Qiao 2011; Shang 2010; Sun 2005; Tan 2011; Tian 2013; Wang 2008; Wang 2011a; Zhong 2009). The remaining 22 studies did not report clinically important differences in other complications.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Control, Outcome 9 Complications ‐ Other [Frequency].

| Complications ‐ Other [Frequency] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Intervention group | Control group |

| Colorectal surgery | ||

| Asao 2002 | 0 | 0 |

| Bahena‐Aponte 2010 | 0 | 2 |

| Bonventre 2014 | 0 ‐ no postoperative complications were observed | 0 ‐ no postoperative complications were observed |

| Cao 2008 | 16 | 12 |

| Forrester 2014 | 0 | 1 |

| Hirayama 2006 | 2 | 1 |

| Li 2012b | 0 ‐ no participants experienced adverse effects | 0 ‐ no participants experienced adverse effects |

| Lim 2013 | 57 | 63 |

| Matros 2006 | 1 | 2 |

| Quah 2006 | 2 | 3 |

| Schluender 2005 | 2 | 2 |

| Schuster 2006 | 1 | 2 |

| Tian 2013 | 4 | 13 |

| Wang 2011a | 28 | 58 |

| Watson 2008 | 6 | 7 |

| Zaghiyan 2013 | 6 | 8 |

| Zhong 2009 | 11 | 20 |

| Caesarean section | ||

| Abd‐El‐Maeboud 2009 | 11 | 31 |

| Garshasbi 2011 | 5 | 26 |

| Jakkaew 2013 | 5 | 2 |

| Kafali 2010 | 5 ‐ inestinal enema for gas passage (after 48 hr without passage of flatus). May have confounded results for time to first flatus | 16 ‐ inestinal enema for gas passage (after 48 hr without passage of flatus). May have confounded results for time to first flatus |

| Liang 2007 | 12 | 23 |

| Luo 2010 | 24 | 60 |

| Satij 2006 | 1 | 4 |

| Shang 2010 | 23 | 41 |

| Zamora 2012 | 0 ‐ no recorded complications (such as fever or temperature >38°C or wound dehiscence) | 0 ‐ no recorded complications (such as fever or temperature >38°C or wound dehiscence) |

| Other surgery | ||

| Abdollahi 2013 | 0 ‐ there were no surgicical complications in the 2 groups | 0 ‐ there were no surgicical complications in the 2 groups |

| Bonventre 2014 | 0 ‐ no postoperative complications were observed | 0 ‐ no postoperative complications were observed |

| Chen 2012 | 9 | 47 |

| Choi 2011 | 9 | 8 |

| Choi 2014 | 2 | 3 |

| Ertas 2013 | 12 | 37 |

| Gong 2011 | 0 ‐ no complications in the intervention group | No information |

| Guangqing 2011 | 5 | 80 |

| Han 2011 | 4 | 37 |

| Huang 2012a | 13 | 31 |

| Huang 2012b | 0 ‐ no bloating, pain nor complications in the intervention group | No information |

| Husslein 2013 | 9 | 63 |

| Jernigan 2014 | 2 | 5 |

| Jin 2010 | 4 | 12 |

| Li 2012a | 19 | 39 |

| Lu 2010a | 10 | 11 |

| Lu 2011 | 2 | 4 |

| Marwah 2012 | 14 | 16 |

| Ngowe 2010 | 0 | 0 |

| Park 2009 | 0 ‐ no postoperative complications such as postoperative infection or haemorrhage | 0 ‐ no postoperative complications such as postoperative infection or haemorrhage |

| Qiao 2011 | 7 | 28 |

| Qiu 2006 | 0 ‐ no complications in the intervention group | No information |

| Ray 2008 | 8 | 11 |

| Sun 2005 | 57 | 142 |

| Tan 2011 | 3 | 22 |

| Wang 2008 | 22 | 190 |

| Yi 2013 | 8 | 10 |

| Zhang 2008 | 0 | 0 |

| Çavuşoğlu 2009 | 1 | 4 |

Ten studies considered complications associated with CG (see Analysis 1.10). Nine reported no complications caused by the intervention (Bonventre 2014; Choi 2014; Ertas 2013; Hirayama 2006; Lee 2004; Li 2007a; Lu 2010a; Schluender 2005; Schweizer 2010). Cabrera 2012 reported abdominal distension, lack of gas and stool passage, and increased postoperative pain in two participants in the intervention group; authors believed this to be due to aerophagia whilst chewing gum.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Control, Outcome 10 Complications related to the intervention [Frequency].

| Complications related to the intervention [Frequency] | |

|---|---|

| Study | |

| Colorectal surgery | |

| Bonventre 2014 | No treatment‐related complications were observed |

| Hirayama 2006 | No side effects or clinical problems were caused by gum‐chewing in any participants during this study |

| Schluender 2005 | There were no adverse events related to chewing. One participant was excluded due to nausea from chewing |

| Schweizer 2010 | In the entire participant population, no complications caused by the chewing gum were observed |

| Other surgery | |

| Bonventre 2014 | No treatment‐related complications were observed |

| Cabrera 2012 | 2 participants (12%) experienced abdominal distension, lack of gas and stool passage, and increased postoperative pain. Authors believed that this was due to aerophagia from chewing gum, therefore the intervention was stopped and nasogastric tubes put in place |

| Choi 2014 | There were no cases of side effects from gum chewing |

| Ertas 2013 | There were no reports of complications associated with gum chewing |

| Lee 2004 | No major complications with gum chewing were noted |

| Li 2007a | There were no adverse effects (e.g. abdominal pain/distension) in the gum chewing group |

| Lu 2010a | Not even one case of chewing gum was found to give an adverse effect on participants |

| Schweizer 2010 | In the entire participant population, no complications caused by the chewing gum were observed |

Tolerability of gum

Twenty‐nine studies reported on participants’ tolerability of gum (eight CRS, nine CS, 10 OS and two including both CRS and OS subgroups) (see Analysis 1.11). Eight CRS, seven CS and seven OS studies reported that gum was tolerated by all participants or that none of the participants were dissatisfied with it (Abd‐El‐Maeboud 2009; Abdollahi 2013; Akhlaghi 2008; Asao 2002; Bonventre 2014; Ertas 2013; Garshasbi 2011; Ghafouri 2008; Kafali 2010; Ledari 2012; Lee 2004; Lim 2013; Marwah 2012; McCormick 2005; Ngowe 2010; Quah 2006; Satij 2006; Schuster 2006; Wang 2011a; Watson 2008; Zamora 2012).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Control, Outcome 11 Tolerability of gum.

| Tolerability of gum | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Description | Method of reporting |

| Colorectal surgery | ||

| Asao 2002 | All the patients tolerated gum chewing from the first AM after the operation | Patient tolerance of postoperative gum chewing was queried and recorded on the chart with information concerning flatus and defecation |

| Bonventre 2014 | All of the patients tolerated treatment from the first postoperative morning | Not discussed |

| Crainic 2009 | Anecdotal findings indicated that 20% of subjects (13 of 66: gum chewing and placebo group) said chewing gum or sucking on hard candy increased nausea | Not discussed |