Abstract

Purpose:

A dual-task paradigm was implemented to investigate how noise type and sentence context may interact with age and hearing loss to impact word recall during speech recognition.

Method:

Three noise types with varying degrees of temporal/spectrotemporal modulation were used: speech-shaped noise, speech-modulated noise, and three-talker babble. Participant groups included younger listeners with normal hearing (NH), older listeners with near-normal hearing, and older listeners with sensorineural hearing loss. An adaptive measure was used to establish the signal-to-noise ratio approximating 70% sentence recognition for each participant in each noise type. A word-recall task was then implemented while matching speech-recognition performance across noise types and participant groups. Random-intercept linear mixed-effects models were used to determine the effects of and interactions between noise type, sentence context, and participant group on word recall.

Results:

The results suggest that noise type does not significantly impact word recall when word-recognition performance is controlled. When data from noise types were pooled and compared with quiet, and recall was assessed: older listeners with near-normal hearing performed well when either quiet backgrounds or high sentence context (or both) were present, but older listeners with hearing loss performed well only when both quiet backgrounds and high sentence context were present. Younger listeners with NH were robust to the detrimental effects of noise and low context.

Conclusions:

The general presence of noise has the potential to decrease word recall, but type of noise does not appear to significantly impact this observation when overall task difficulty is controlled. The presence of noise as well as deficits related to age and/or hearing loss appear to limit the availability of cognitive processing resources available for working memory during conversation in difficult listening environments. The conversation environments that impact these resources appear to differ depending on age and/or hearing status.

Speech recognition in noise is a primary concern for listeners with hearing impairment. This complex task is known to be influenced by numerous auditory and nonauditory factors related to the environment and the listener. One relevant topic within speech perception in noise research involves how noise impacts listener performance in aspects outside of traditional speech recognition. One such aspect involves the ability to recall words reported following a delay (i.e., recognition recall). Seminal papers by Rabbitt (1966, 1968) showed that the addition of noise during a speech-recognition task negatively impacts simultaneous secondary tasks, namely, recognition recall. Even when the presentation level of the noise was set in a manner that allowed nearly perfect recognition, listeners’ ability to remember what they had heard was diminished (also see Kjellberg et al., 2008; Koeritzer et al., 2018).

Background noise type has a large effect on speech perception in noise. According to the glimpsing theory, the auditory system isolates time–frequency (T–F) units in which the energy of the target speech is favorable relative to that of the noise, which results in multiple “glimpses” that can be recombined to assemble a representation of the target (Cooke, 2006). Energetic masking occurs when acoustic information from the target is lost due to temporal and spectral overlap with the noise. Nonenergetic masking known as informational masking can also occur (similar to “perceptual masking” originally described by Carhart et al., 1969) and is most relevant when the background is speech or speechlike. Nonenergetic or informational masking leads to the inadvertent processing of acoustic or linguistic information from the background, which interferes with the ability to segregate and process the target speech (e.g., Brungart et al., 2006). Nonenergetic masking can also be related to the phenomenon of modulation interference, in which a competing sound containing amplitude modulations similar to that of target speech interferes with the processing of the target (e.g., Kwon & Turner, 2001). Finally, gated or modulated noises can produce forward and perhaps backward masking to a greater degree than steady-state noises (Dirks et al., 1969; Fogerty et al., 2016).

The extent to which glimpsing can benefit speech recognition varies with the type of noise involved. Noises that modulate in frequency or time offer more glimpsing cues and can be poorer maskers than steady-state noises. Up to 8 dB of masking release can be observed with an amplitude-modulated noise masker compared with a steady noise masker (Festen & Plomp, 1990; Gustafsson & Arlinger, 1994). Furthermore, the opposite trend is noted in terms of informational masking and modulation interference. This presents a paradox in which speechlike modulating noises are less energetically masking and thus present better opportunity for masking release but are simultaneously more likely to lead to inefficient segregation of the speech from the noise or modulation interference.

The finding that noise can hinder recall even when recognition is intact has been interpreted as evidence that increased difficulty during speech recognition can interrupt other cognitive activities, such the memory encoding of auditory material. There is growing evidence that listeners engage additional cognitive resources when recognizing speech in degraded acoustic environments compared with quiet environments, which reduces resources available for other cognitive tasks (cognitive load hypothesis; Cosetti et al., 2016). Variability in cognitive skillset may partially account for the considerable individual variability in speech recognition in noise that remains unexplained by hearing loss, most notably when the background sounds are complex (Akeroyd, 2008). Individual differences in cognitive skills may also mediate individual success with hearing aid signal processing (Akeroyd, 2008; Lunner, 2003; Ng et al., 2013). Semantic context is another factor that influences speech perception in noise and has also been shown to aid both recognition (Nittrouer & Boothroyd, 1990) and recall in both quiet and in noise (Koeritzer et al., 2018).

Listener-specific factors, such as age and hearing status, can impact cognitive skills and the degree to which noise impacts speech recognition and recall. Compared with younger listeners, older listeners perform more poorly on speech recognition tasks, especially in noise. This has been documented in continuous noise (Dubno et al., 2002), interrupted or modulated noise (Dubno et al., 2002; Gifford et al., 2007; Grose et al., 2009; Gustafsson & Arlinger, 1994), and in competing speech backgrounds (Pichora-Fuller et al., 1995; Schoof & Rosen, 2014). These studies also show that hearing loss is significantly related to performance; however, age-related decline in speech recognition has also been shown to be independent of hearing status (Dubno et al., 2002; Gordon-Salant, 2006).

Deterioration of the auditory periphery is certainly a contributor to older listeners’ increased difficulty in background noise. Specific aspects of frequency resolution (Humes, 1996), peripheral auditory thresholds, and cognition are all known to decline with age and are likely to contribute to the age-related decline in speech perception. One of the clearest and largest auditory deficits associated with aging involves impaired temporal processing, which occurs independent of declines in hearing threshold (for reviews, see Fullgrabe, 2013; Gordon-Salant, 2006). Behavioral and electrophysiological studies have shown deficits in older individuals’ processing of envelope cues (Grose et al., 2009) and temporal fine structure cues (Fullgrabe, 2013), both of which are important for speech recognition in noise (Assmann & Summerfield, 2004; Rosen, 1992).

Age-related declines in broader central processing may directly manifest as declines in various auditory skills (Humes et al., 2012). This is especially important to consider in context with a decline-compensatory hypothesis in which processing declines may activate additional cognitive resources to maintain speech recognition performance. These declines may interact with acoustic characteristics of the environment and contribute to age-related differences in speech perception in noise. Compared with younger listeners, older listeners exert more effort to achieve the same level of performance on speech recognition in noise tasks (Anderson Gosselin & Gagné, 2011; Desjardins & Doherty, 2012) and benefit more from conditions offering context than younger participants (Desjardins & Doherty, 2012; Pichora-Fuller et al., 1995). Furthermore, age-related declines in working memory, processing speed, and inhibition may make older listeners more susceptible to informational masking than younger listeners (Tillman et al., 1973).

With regard to hearing status, sensorineural hearing loss leads to both threshold and suprathreshold auditory deficits, which dramatically impact speech recognition in noise. Auditory filters generally broaden as auditory thresholds increase (Glasberg & Moore, 1986; Moore, 2007). Broadened filters introduce distortion to the spectral representation of the speech signal, which subsequently reduces speech recognition (ter Keurs et al., 1993), increases susceptibility to upward spread of masking (Baer & Moore, 1993), and reduces benefit from masking release (Festen & Plomp, 1990; ter Keurs et al., 1993). In terms of the glimpsing theory, poor spectral resolution increases the proportion of T–F units that contain at least some noise, leaving fewer noise-free units on which to base speech recognition. Accordingly, background noise is known to disproportionately affect listeners with hearing impairment compared with listeners with normal hearing (NH). This disproportionate effect of sensorineural hearing loss is driven largely by suprathreshold deficits, as this effect remains even when amplification is provided.

Listeners with hearing impairment show more difficulty listening in forward speech backgrounds compared with time-reversed speech backgrounds (Summers & Molis, 2004), suggesting a possible increase in nonenergetic masking as well. Hearing impairment may also increase the cognitive burden during speech recognition in difficult environments. For example, adults with mild hearing impairment have been shown to recall fewer words than adults with NH, despite having correctly recognized the same amount of words (Rabbitt, 1990).

As methodology and acoustic parameters often vary substantially between studies, it can be difficult to compare studies involving speech recognition or recall in noise. Primary differences across studies include the noise type(s) and signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) used. Noise type directly impacts masking and auditory processing at peripheral and central levels. In terms of SNR, studies often use a fixed SNR for all participants, allowing individual speech recognition performance to vary, which does not account for individual differences in glimpsing capabilities or cognitive skillset. The use of a single SNR for all listeners effectively creates a different perceptual environment for each listener, with some listeners experiencing more difficulty than others at the same SNR. In this study, speech-perception performance rather than SNR was fixed across individuals, in an effort to reduce variability in overall task difficulty resulting from differences in glimpsing and cognitive abilities.

In addition, the audiologic definition of hearing impairment varies across studies, specifically in the degree of low-frequency hearing loss. Listeners with a sloping hearing loss affecting only the high frequencies would have glimpsing capabilities in the low frequencies comparable with that of listeners with NH and may perform more similarly to listeners with NH than a participant group with at least moderate hearing loss across all frequencies. Variability in these various factors may contribute to the lack of clarity with regard to how noise type impacts speech perception across populations.

The goal of this study was to investigate the impact of noise and sentence context on speech recognition and recall in multiple patient populations, using multiple noise types while controlling speech perception performance to account for individual variability in overall glimpsing and cognitive skills. Hearing-impaired participants demonstrating at least moderate hearing loss across most frequencies were recruited in order to ensure that these listeners possessed little if any spectral regions of normal function.

Method

Two experiments were performed using the same participants. There were three groups of participants: a younger group with normal hearing (YNH), an older group with near-normal hearing (ONN), and an older group with hearing impairment (OHI). Mean audiograms for ONN and OHI groups are provided in Figure 1. Testing was performed over two sessions, each lasting no more than 2 hr. A hearing assessment, cognitive evaluation, and Experiment 1 were completed during the first session. Experiment 2 was completed during the second session.

Figure 1.

Group mean pure-tone air-conduction audiometric thresholds (and standard deviations) for the older group with near-normal hearing (ONN; unfilled symbols) and older group with hearing impairment (OHI; filled symbols). X symbols indicate left-ear thresholds, and O symbols indicate right-ear thresholds. The 20 dB HL limit of normal hearing is represented by the horizontal dotted line. Thresholds below 20 dB HL were not determined. ANSI = American National Standards Institute.

The purpose of Experiment 1 was to individually measure the SNR at which each participant approximated 70% correct sentence recognition (SNR-70) in each of three noise types varying in spectrotemporal complexity. The noise types included steady speech-shaped noise (SSN), speech-modulated noise (SMN), and three-talker babble (3T). The purpose of Experiment 2 was to assess word recall in these noise types using a dual-task paradigm in which a word-recall task was combined with a concurrent word-recognition task. Word-recall performance served as an indirect measure of working memory, as working memory capacity is likely to be affected by cognitive resource allocation during complex tasks. It was hypothesized that more complex listening conditions would increase the burden on cognitive resources, including working memory capacity, which in turn would reduce the memory for what was said during noisy conversation (Lunner, 2003; Ng et al., 2013; Pichora-Fuller et al., 1995; Tun et al., 2009). The SNR-70s measured in Experiment 1, at which equal performance was observed for each noise and listener, were used as the SNRs in Experiment 2. As a result, recall performance was measured in “equally difficult” acoustic environments for all participants regardless of individual differences in hearing status, age, and noise tolerance.

These three noise types provided not only different levels of complexity but they also provided different types of glimpsing cues. The SSN noise type is nominally or acoustically steady and minimalizes glimpsing opportunities; SMN offers temporal glimpsing cues simultaneously across the frequency spectrum; and 3T offers spectrotemporal glimpsing cues consisting of glimpses at different spectral loci at different times. They were employed to assess the extent to which they differentially disrupt working memory, measured in terms of differences in recall performance between noise conditions. It is not well known whether spectrotemporal aspects of the noise interact with cognitive skills or if working memory performance varies across these different noises. Accordingly, these noise types allow an assessment of how the availability of varying glimpsing cues may influence the cognitive burden incurred during speech recognition.

Participants

This study was performed with approval from The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board. Participants included nine individuals in the YNH group (eight women; aged 21–30 years; x̅: 24.8 years), nine individuals in the ONN group (six women; aged 60–67 years; x̅: 63.2 years), and eight individuals in the OHI group (six women; aged 63–71 years; x̅: 66.0 years). Participants in the YNH group were recruited from The Ohio State University student population and nearby metropolitan area. Participants in the ONN and OHI groups were recruited from The Ohio State University Speech-Language-Hearing Clinic and nearby metropolitan area. All participants had no prior exposure to the speech materials used and denied history of any medical or neurological contraindications to testing.

Age criteria for each group were determined based on research suggesting that age-related cognitive declines in speech processing and memory are greater for individuals above 60 years of age (Salthouse, 2009). Accordingly, participants in the YNH group were between 18 and 30 years of age to obtain a sample of adults who were least likely to demonstrate age-related cognitive decline. Participants in the ONN and OHI groups were aged 60 years and older to ensure recruitment from populations that were most likely to demonstrate typical cognitive decline associated with aging.

A hearing assessment was performed on date of first test, which included otoscopy, tympanometry (American National Standards Institute [ANSI], 1987), and pure-tone audiometry (ANSI, 2004, 2010). All hearing testing was performed using diagnostic equipment calibrated for clinical use. For participants in the YNH group, NH was defined as passing a pure-tone air-conduction screening at 20 dB HL for octave frequencies from 250 to 8000 Hz. For participants in the ONN group, near-normal hearing was defined as having pure-tone air-conduction thresholds of 30 dB HL or better at octave frequencies from 250 to 3000 Hz, with air–bone gaps no greater than 10 dB, and with no greater than 10-dB difference in thresholds across ears between 250 and 3000 Hz. This resulted in the recruitment of listeners with no greater than a mild hearing loss in the primary speech-frequency regions. Thresholds at 4000 Hz also fulfilled these criteria, with two exceptions (ONN 01 and 03). Thresholds at 8000 Hz were over 30 dB HL for the majority of listeners (six of nine). Audiograms for each individual ONN listener are provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Pure-tone air-conduction audiometric thresholds for individual participants in the older group with near-normal hearing (ONN). X symbols indicate left-ear thresholds, and O symbols indicate right-ear thresholds. The 20 dB HL limit of normal hearing is represented by a horizontal dotted line in each panel. Thresholds below 20 dB were not determined. Participant number, age in years, and sex are displayed in each panel. ANSI = American National Standards Institute.

Participants in the OHI group demonstrated symmetrical, sensorineural hearing loss that was generally moderate in degree. Pure-tone average air-conduction thresholds (based on 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz and averaged across ears) ranged from 35 to 68 dB HL. Air–bone gaps were no greater than 10 dB at octave frequencies from 250 to 8000 Hz. No greater than a 10-dB asymmetry in air-conduction thresholds between ears was permitted between 250 and 3000 Hz. These individuals also showed bilateral word-recognition scores (WRSs) in quiet of at least 65% correct to only include individuals who demonstrated at least “fair” word understanding (Lawson & Peterson, 2011). Listeners in this group were experienced hearing aid users who had been fit bilaterally for at least 1 year and had worn their current hearing aids for at least 12 weeks to ensure full acclimatization to new amplification (Kuk et al., 2003). Audiograms for each individual OHI listener are provided in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

As Figure 2 but for the older group with hearing impairment (OHI). ANSI = American National Standards Institute.

Cognitive Tests

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment was used as an enrollment criterion to screen individuals for mild cognitive impairment (Nasreddine et al., 2005). Only participants who achieved a passing score of 26 or greater were invited to participate. Three other tests of cognitive function were used to characterize the cognitive status of each individual and group. These tests were used to assess processing speed, inhibition, and working-memory capacity and were administered in that order.

Processing speed was measured using the Letter Digit Substitution Test (LDST; van der Elst et al., 2006). Participants were provided a key of numbers 1–9 and corresponding letters to which the numbers were paired. A grid of randomized letters was printed below the key. Participants were instructed to fill in as much of the grid as possible in 60 s, by writing the number corresponding to each letter in the grid. A higher LDST score indicated better/faster processing speed.

Inhibition was measured using a visual Stroop task (Stroop, 1935). Words that spell colors (e.g., “red”) were presented on a computer screen in congruent and incongruent trials. For congruent trials, the color of the text matched the color spelled by the word. For incongruent trials, these aspects differed. Control trials showing a colored rectangle were also presented. Participants were asked to identify the color seen on the screen, rather than the color indicated by spelling, as quickly and accurately as possible. Responses were entered by the participant pressing buttons on a keyboard. A lower Stroop score indicated better inhibition. The recorded measurement was the average response time for all correctly recognized incongruent trials divided by the average response time for all correctly recognized control trials. This normalization factored out age-related changes in general processing speed that influence response times (Ben-David & Schneider, 2009; Knight & Heinrich, 2017).

Working-memory capacity was assessed using a reading-span test (RSpan, Daneman & Carpenter, 1980). The RSpan is a nonauditory verbal working memory test that taps both storage and processing capacities of working memory. A higher RSpan score indicates better working memory capacity. Sentences were presented individually on a computer screen. Participants judged whether or not the sentence was semantically plausible (made logical sense), and then saw a single letter presented on the screen. After a given series of sentences and letters, corresponding to a given set size (three, four, five, six, or seven sentences), the participant was prompted to recall the letters in serial order. Each participant received three presentations of each set size. The recorded measurement was the traditional “absolute RSpan” score, which consisted of the sum of the letters from all perfectly recalled sets.

Declines in these three specific cognitive skills have been shown to be associated with aging and have been proposed to be relevant to successful speech perception in noise (Akeroyd, 2008; Rönnberg, 2003; Schoof & Rosen, 2014). To avoid the potential confound involving the modality under test, all cognitive tests were performed in the visual modality. These tests are free and publicly available either in pencil-and-paper format or in computerized format (http://www.millisecond.com).

Experiment 1: Adaptive Speech-in-Noise Testing

Stimuli

Target stimuli for this experiment were phonetically balanced sentences from the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) corpus (IEEE, 1969) spoken by a male talker. This corpus consists of 72 lists with each list containing 10 sentences and each sentence containing five keywords for scoring intelligibility. These sentences have a moderate to high semantic context. Sentences were selected from Lists 1–50 for testing and Lists 71–72 for practice.

The three background noise types differed in their spectral and temporal composition and were expected to introduce different elements to masking. The SSN represented an acoustically unmodulated masker and was created by shaping a 10-s white noise to match the long-term average amplitude spectrum (65,536-point Hanning-windowed fast Fourier transform with 97% temporal overlap) of a set of 20 concatenated and level-equated test sentences spoken by the target voice.

The SMN background represented a temporally modulated masker, which allowed for the glimpsing of speech during brief time periods when the noise amplitude dipped relative to that of the target. These acoustic glimpses were available across all frequencies simultaneously. The SMN noise was created by modulating the SSN with the broadband amplitude envelope of a three-talker babble (the 3T noise described below). The broadband envelope was extracted using half-wave rectification and low-pass filtering (12th order Butterworth, 6 dB/octave per order rolloff; see Healy & Steinbach, 2007) at 17 Hz, which equals half of the bandwidth of the first equivalent rectangular bandwidth filter in the range of human auditory sensitivity (Glasberg & Moore, 1990). This smoothing was performed to avoid smoothing of higher envelope rates by the auditory system, which could potentially differ across participants due to their differing hearing status and accompanying auditory tuning.

The 3T background represented a spectrotemporally complex modulated masker, which allowed for glimpsing in both the frequency and time domains. This number of talkers was chosen based on findings from Simpson and Cooke (2005) and Rosen et al. (2013). These studies respectively measured consonant and IEEE sentence recognition in babble at a fixed SNR, with varying number of talkers composing the babble noise. The use of three talkers was selected more directly from Rosen et al. (2013), who showed a significant decrease in IEEE sentence recognition between one- and two-talker babble but little change in recognition with babble containing two, four, eight, or 16 talkers. The 3T babble was created using sentences from the AzBio test (Spahr et al., 2012), spoken by one female and two male voices. For each voice, 20 different AzBio sentences were equated in amplitude, concatenated, and time reversed. These three files were mixed at random start positions relative to one another and a random overall start position to create the 3T babble for each target sentence. The 3T background was created using time-reversed speech signals to limit listeners’ confusion with the target stimulus and reduce lexical/semantic interference.

Procedure

Following the completion of the cognitive tasks, participants completed a speech recognition in noise task. An adaptive procedure (Levitt, 1971) was used to find the SNR that approximated SNR-70 for each individual in each of the three noise types. The procedure was similar to that of Kwon et al. (2012) and was employed to minimize the confound involving overall task difficulty.

During the adaptive procedure (one down/one up), the level of the noise was adjusted while the level of the target IEEE sentence remained constant. The SNR decreased if the participant correctly identified four or more keywords (80%) and increased if the participant correctly identified three or fewer keywords (60%). Testing began at an SNR of −6 dB, which increased in 4-dB steps after each sentence presentation until at least four keywords in a given sentence were correctly reported. The level of the noise was adjusted in 4-dB steps for the first four reversals, and then in 2-dB steps for the next four reversals. The SNR values at the final four reversals were averaged and recorded as the SNR-70 for that block of trials. Five adaptive runs were completed for each noise type. The values from the three runs having the lowest deviation from the mean of all five blocks were averaged to represent the SNR-70 for that noise type. All blocks of a given noise type were completed before proceeding to the next noise type. The presentation order of noise type and the sentence-to-condition correspondence was randomized for each participant.

Participants were instructed to repeat back as much of each sentence as possible and were encouraged to guess when unsure. Spoken responses were scored for number of keywords correct by the experimenter. Repeated presentation of sentences was not permitted. All testing was performed with participants seated with the experimenter in a double-walled sound booth. Stimuli were presented from a desktop computer, converted to analog form using an RME Fireface UC digital-to-analog converter and presented diotically over Sennheiser HD280 Pro Headphones. The overall root-mean-square (RMS) level of the target speech stimuli (prior to the addition of noise) was calibrated to 65 dBA in each headphone using a sound-level meter and flat-plate coupler (Larson Davis models 824 and AEC 101).

For the participants in the OHI group, individualized frequency-specific gains were added to the 65-dBA presentation level to ensure audibility. Gains were based on the pure-tone audiogram according to the NAL-RP fitting rational (Byrne & Dillon, 1986). They were implemented using a RANE DEQ 60 L digital equalizer as described in Healy et al. (2015). The total RMS level with frequency-specific gains did not exceed 99 dBA for any participant.

A short practice of 20 sentences was provided before adaptive testing began. Practice sentences were IEEE sentences unused during formal testing. Five sentences were first presented in quiet, followed by five sentences in each noise type presented at +6 dB SNR. The presentation order of noise types during practice was SSN, SMN, 3T.

Experiment 2: Word Recall Testing

Stimuli

Target stimuli in this experiment were sentences from the Revised Speech Perception in Noise Test (R-SPIN; Bilger et al., 1984). This corpus consists of 200 target words positioned as the final word in 200 high-predictability (HP) and 200 low-predictability (LP) sentences. As the names suggest, the final word in HP sentences are predictable through the semantic content of the preceding words, whereas those in LP sentences are not. A total of 320 R-SPIN target sentences were presented, with 160 in each of the HP and LP conditions. The same three background noises were employed, and each noise type for each participant was presented at a fixed SNR corresponding to their individual and noise-specific SNR-70 determined during Experiment 1. The creation of the noises followed the procedures used in Experiment 1, using a separate SSN created to match the SPIN sentences (again a 10-s white noise shaped to match 10 HP and 10 LP concatenated and level-equated test sentences spoken by the target voice).

Different sentence corpora were employed for Experiments 1 and 2 due to the different requirements of those experiments—Experiment 1 required a large number of sentences (IEEE) due to the use of adaptive tracking and a fixed number of reversals rather than a fixed number trials, whereas the design of Experiment 2 required a sentence-final scoring corpus (R-SPIN). The SNR-70 values obtained using the IEEE sentences were increased by 2 dB for use with the R-SPIN sentences. This correction factor was based on pilot data obtained from a group of younger listeners with NH who did not participate in the formal study and was found to approximately equate intelligibility across the corpora in each noise type.

Procedure

Experiment 2 involved a dual recognition/recall task. The recall aspect of the task was designed to tap both processing and storage aspects of working memory and was modeled after the methods of Daneman and Carpenter (1980), Pichora-Fuller et al. (1995), and Ng et al. (2013). In accord with typical R-SPIN testing, participants were instructed to listen to each sentence and to repeat the final word immediately following the presentation of each sentence. Sentences were grouped into sets of eight, based on the findings of Pichora-Fuller et al. (1995), who showed that a set size of eight is sensitive to different age groups compared with smaller set sizes. Participants reported the final word after each sentence. At the end of the set of eight sentences, participants again recalled the final words they reported for each of the eight sentences, in any order. Words were scored as correctly recalled according to how the words were reported by the participant, regardless of whether the reported word was the correct R-SPIN word. Only an exact match of the reported word was scored as correctly recalled. Participants were made aware of the recall portion of the task prior to testing.

Recall was measured in quiet and in all three noise types, as well as in HP and LP conditions separately, yielding eight total blocks. All four blocks (corresponding to quiet, SSN, SMN, and 3T) within the same predictability were completed before moving on to the remaining four blocks of the opposite predictability condition. Presentation order of HP and LP conditions was balanced across participants. Within each predictability condition, testing in quiet was completed first and the presentation order of noise types was randomized for each participant. The sentence-to-condition correspondence was also randomized for each participant.

Within each block, five eight-sentence recall sets were presented. The first recall set served as practice, whereas the following four sets were scored and averaged to represent the recall score for that block. The test setting, apparatus, and other procedures followed those of Experiment 1. The level of the stimulus presentation was set to 65 dBA. As in Experiment 1, NAL-RP gains for OHI listeners were added to this level. The total RMS level with frequency-specific gains again did not exceed 99 dBA for any participant.

Statistical Analysis

A first analysis allowed an investigation of how cognitive measures compared across participant groups. To answer this question, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed to evaluate the effect of participant group on each cognitive test. A second and third analysis allowed an investigation of how noise impacts speech recognition (Experiment 1) and word recall (Experiment 2) for the various participant groups. Random-intercept linear mixed models (LMMs) were constructed to answer these questions. The random intercepts were included in these analyses to account for the fact that multiple measurements were recorded from each participant. All data analysis was conducted in R software, using the default dummy coding where applicable.

The second analysis described above involved a single random-intercept LMM labeled Model A. The fixed effects included factors of noise type and participant group, as well as their interaction. The dependent variable was SNR-70. The primary question for this analysis was how does noise type impact speech recognition and interact with listener characteristics that differ between participant groups?

The third analysis involved two random-intercept LMMs, labeled Models B and C. Both models included fixed effects of noise, participant group, and context (HP and LP), as well as interactions. The dependent variable was word recall. For Model B, the primary question was whether there was an effect of noise type on word recall. Accordingly, recall data from the quiet condition were excluded from analysis. Results from Model B prompted the design of Model C, which addressed whether the presence of noise, separately from its type, influenced word recall. For Model C, recall data from quiet were included and data from the three noise types were pooled.

Results

Cognitive Tests

Table 1 shows the mean scores and standard deviations for the Stroop, LDST, and RSpan tests for each group. Table 2 summarizes the results of the one-way MANOVA that assessed differences in cognitive scores between participant groups. This analysis revealed significant differences in performance on these three cognitive tests between participant groups (F = 3.20, p < .05), specifically for performance on the Stroop (F = 8.71, p < .01) and LDST (F = 7.45, p < .01). Differences in RSpan performance were not significant (p > .05). However, the 16-point higher mean score of the YNH group relative to the ONN and OHI groups is notable.

Table 1.

Mean scores and standard deviations on the Stroop, letter digit substitution, and reading span tests for the younger group with normal hearing, older group with near-normal hearing, and older group with hearing impairment.

| Cognitive measure | Participant group |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YNH |

ONN |

OHI |

||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Stroop | 1.07 | 0.10 | 1.28 | 0.16 | 1.37 | 0.20 |

| LDST | 41.78 | 6.16 | 33.44 | 4.33 | 34.38 | 4.10 |

| RSpan | 48.33 | 15.07 | 32.44 | 21.02 | 32.63 | 22.30 |

Note. YNH = younger group with normal hearing; ONN = older group with near-normal hearing; OHI = older group with hearing impairment; LDST = Letter Digit Substitution Test; RSpan = reading span test.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) table with participant group as the independent variable and scores on the Stroop, Letter Digit Substitution Test (LDST), and reading span test (RSpan) as the dependent variables.

| Source | df | Pillai | Approx F | Num df | Den df | Pr (> F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant group | 2 | 0.61 | 3.20 | 6 | 44 | < .05* |

| Stroop | 2 | 8.71 | < .01** | |||

| LDST | 2 | 7.45 | < .01** | |||

| RSpan | 2 | 1.91 | .17 | |||

| Residuals | 23 |

Note. df = degrees of freedom; Num df = number of degrees of freedom in the model; Den df = number of degrees of freedom associated with errors in the model; Pr (> F) = p value.

p value is less than .05.

p value is less than .01.

Overall, the YNH group demonstrated better performance on the cognitive tests compared with the ONN and OHI groups, whereas the ONN and OHI groups demonstrated similar performance on all cognitive tests. These results suggest that cognitive performance of our participants was more impacted by age than by hearing status, as older listeners with and without hearing loss shared similar cognitive performance.

Experiment 1

Figure 4 displays the mean SNR required to approximate 70% sentence recognition, for each participant group in each noise type. Table 3 summarizes the results of the random-intercept LMM for Experiment 1, designated as Model A. Results show a significant main effect of participant group (F = 28.88, p < .001), a significant main effect of noise type (F = 288.40, p < .001), and a significant interaction between noise type and participant group (F = 26.76, p < .001). Because the interaction is significant, contrasts within each main effect are not listed and we instead look to the individual components of the interaction (and Figure 4) for details. Estimated marginal means were used to calculate the pairwise contrasts within the interaction.

Figure 4.

Mean signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) values (and standard errors) approximating 70% correct sentence recognition (SNR-70) for each noise type as a function of participant group. OHI = older group with hearing impairment; ONN = older group with near-normal hearing; YNH = younger group with normal hearing; SSN = speech-shaped noise; SMN = speech-modulated noise; 3T = three-talker babble.

Table 3.

Model A: Linear mixed model with participant group and noise type as fixed effects and 70% correct sentence recognition (SNR-70) as the dependent variable (pairwise contrasts are intended).

| Parameter | Estimate | Test statistic (df) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant group | F = 28.88 (2) | < .001*** | |

| Noise type | F = 288.40 (2) | < .001*** | |

| Participant Group × Noise Type | F = 26.76 (4) | < .001*** | |

| YNH (SSN vs. SMN) | 2.08 | t = 6.07 (280) | < .001*** |

| YNH (SSN vs. 3T) | −2.33 | t = −6.80 (280) | < .001*** |

| YNH (SMN vs. 3T) | −4.42 | t = −12.87 (280) | < .001*** |

| ONN (SSN vs. SMN) | 0.42 | t = 1.21 (280) | = .74 |

| ONN (SSN vs. 3T) | −3.83 | t = −11.17 (280) | < .001*** |

| ONN (SMN vs. 3T) | −4.25 | t = −12.38 (280) | < .001*** |

| OHI (SSN vs. SMN) | −2.59 | t = −7.13 (280) | < .001*** |

| OHI (SSN vs. 3T) | −6.50 | t = −17.85 (280) | < .001*** |

| OHI (SMN vs. 3T) | −3.91 | t = −10.73 (280) | < .001*** |

| SSN (YNH vs. ONN) | 0.14 | t = 0.13 (26.17) | = .90 |

| SSN (YNH vs. OHI) | −4.89 | t = −4.24 (26.17) | < .01** |

| SSN (ONN vs. OHI) | −5.03 | t = −4.36 (26.17) | < .01** |

| SMN (YNH vs. ONN) | −1.53 | t = −1.37 (26.17) | = .74 |

| SMN (YNH vs. OHI) | −9.57 | t = −8.29 (26.17) | < .001*** |

| SMN (ONN vs. OHI) | −8.04 | t = −7.00 (26.17) | < .001*** |

| 3T (YNH vs. ONN) | −1.36 | t = −1.22 (26.17) | = .74 |

| 3T (YNH vs. OHI) | −9.06 | t = −7.85 (26.17) | < .001*** |

| 3T (ONN vs. OHI) | −7.70 | t = −6.67 (26.17) | < .001*** |

Note. p values were adjusted using the Holm–Bonferroni method for multiple comparisons. df = degrees of freedom; YNH = younger group with normal hearing; SSN = speech-shaped noise; 3T = Three-Talker Babble; SMN = speech-modulated noise; ONN = older group with near-normal hearing; OHI = older group with hearing impairment.

p value is less than .05.

p value is less than .01.

Regarding the contrasts involving participant group, the OHI group displayed significantly higher (required the most favorable) SNR-70s in all noise types, relative to the ONN and YNH groups (p < .01). This result was consistent with known deficits in glimpsing and speech recognition in noise associated with sensorineural hearing loss. The YNH and ONN groups overall performed similarly in all noise types (p ≥ .74).

Regarding the contrasts involving noise type, SNR-70 was highest (less noise tolerated) for the 3T noise for all participant groups (p < .001). The SNR-70s for YNH, ONN, and OHI groups were, on average, 4.4, 4.3, and 3.9 dB more favorable in 3T compared with SMN, and, on average, 2.3, 3.8, and 6.5 dB more favorable in 3T compared with SSN. The relationship between SSN and SMN differed between participant groups, consistent with the significant interaction. For the YNH group, SNR-70 was lower for SMN than SSN (p < .001), consistent with studies showing that younger listeners with NH show benefit from masking release in temporally modulated noise (e.g., Kwon & Turner, 2001; Kwon et al., 2012). For the ONN group, the SNR-70 for SMN was not different from SSN (p = .74), consistent with the detrimental effect of age on masking release (Dubno et al., 2002; Gifford et al., 2007). For the OHI group, the SNR-70 for SMN was larger than SSN (p < .001), suggesting the OHI group may have experienced some degree of modulation masking (Fogerty et al., 2016; Kwon & Turner, 2001).

Experiment 2

Because the focus of Experiment 2 was on word recall rather than recognition, word recognition was not plotted. However, it is important to note that the current use of SNR-70 successfully resulted in similar speech-recognition performance across conditions and listeners. For HP stimuli, the average difference in recognition between participant groups within a given noise type was 6.5 percentage points. For LP stimuli, this average difference was 9.9 percentage points.

Turning to word recall, Table 4 summarizes the results for random-intercept LMM Model B, in which only data from the three noise conditions was included, and the quiet condition was excluded. This allowed a focus on the potential effect of noise type on recall performance across groups. Table 5 summarizes the results from Model C, in which recall data from the three noise conditions were pooled and compared with that from the quiet condition. This allowed a focus on the extent to which the general presence of noise, rather than specific type of noise, influenced recall performance across groups.

Table 4.

Model B: Linear mixed model with participant group, noise type, and context as fixed effects and recall as the dependent variable (pairwise contrasts are intended).

| Parameter | Estimate | Test statistic (df) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant group | F = 6.76 (2) | < .01** | |

| YNH vs. ONN | 15.28 | t = 2.77 (23) | < .05* |

| YNH vs. OHI | 19.68 | t = 3.46 (23) | < .01** |

| ONN vs. OHI | 4.41 | t = 0.77 (23) | .45 |

| Noise type | F = 1.89 (2) | = .16 | |

| Context | F = 11.04 (1) | < .01** | |

| High vs. low | 4.56 | t = 3.32 (115) | < .01** |

| Participant Group × Noise Type | F = 1.21 (4) | = .31 | |

| Participant Group × Context | F = 1.88 (2) | = .16 | |

| Noise type × Context | F = 1.51 (2) | = .23 | |

| Participant Group × Noise Type × Context | F = 1.28 (4) | = .28 |

Note. p values were adjusted using the Holm–Bonferroni method for multiple comparisons. df = degrees of freedom; YNH = younger group with normal hearing; ONN = older group with near-normal hearing; OHI = older group with hearing impairment.

p value is less than .05.

p value is less than .01.

Table 5.

Model C: Linear mixed model with participant group, noise type, and context as fixed effects and recall as the dependent variable (pairwise contrasts are intended).

| Parameter | Estimate | Test statistic (df) | p value | Contrast no. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant group | - | F = 5.44 (2) | < .05* | ||

| Noise | - | F = 16.68 (1) | < .001*** | ||

| Context | - | F = 5.79 (1) | < .05* | ||

| Participant Group × Noise | - | F = 1.59 (2) | = .21 | ||

| Participant Group × Context | - | F = 1.59 (2) | = .21 | ||

| Noise × Context | - | F = 0.61 (1) | = .44 | ||

| Participant Group × Noise × Context | - | F = 5.83 (2) | < .01** | ||

| High | YNH (noise vs. quiet) | 1.16 | t = 0.34 (173) | = 1.00 | |

| ONN (noise vs. quiet) | −3.24 | t = −0.94 (173) | = 1.00 | ||

| OHI (noise vs. quiet) | −12.11 | t = −3.32 (173) | < .05* | 1 | |

| Low | YNH (noise vs. quiet) | −6.37 | t = −1.85 (173) | = .85 | |

| ONN (noise vs. quiet) | −14.12 | t = −4.11 (173) | < .01** | 3 | |

| OHI (noise vs. quiet) | −0.39 | t = −0.11 (173) | = 1.00 | ||

| Noise | YNH (high vs. low) | 4.75 | t = 1.95 (173) | .73 | |

| ONN (high vs. low) | 7.76 | t = 3.19 (173) | < .05* | 4 | |

| OHI (high vs. low) | 1.17 | t = 0.46 (173) | = 1.00 | ||

| Quiet | YNH (high vs. low) | −2.78 | t = −0.66 (173) | = 1.00 | |

| ONN (high vs. low) | −3.13 | t = −0.74 (173) | = 1.00 | ||

| OHI (high vs. low) | 12.89 | t = 2.89 (173) | = .08 | 2 | |

| High | Noise (YNH vs. ONN) | 13.77 | t = 2.42 (29.24) | = .35 | |

| Noise (YNH vs. OHI) | 21.47 | t = 3.67 (29.24) | < .05* | ||

| Noise (ONN vs. OHI) | 7.70 | t = 1.31 (29.24) | = 1.00 | ||

| Low | Noise (YNH vs. ONN) | 16.78 | t = 2.95 (29.24) | = .10 | |

| Noise (YNH vs. OHI) | 17.90 | t = 3.06 (29.24) | = .09 | ||

| Noise (ONN vs. OHI) | 1.11 | t = 0.19 (29.24) | = 1.00 | ||

| High | Quiet (YNH vs. ONN) | 9.38 | t = 1.41 (52.57) | = 1.00 | |

| Quiet (YNH vs. OHI) | 8.20 | t = 1.20 (52.57) | = 1.00 | ||

| Quiet (ONN vs. OHI) | −1.17 | t = −0.17 (52.57) | = 1.00 | ||

| Low | Quiet (YNH vs. ONN) | 9.03 | t = 1.36 (52.57) | = 1.00 | |

| Quiet (YNH vs. OHI) | 23.87 | t = 3.49 (52.57) | < .05* | ||

| Quiet (ONN vs. OHI) | 14.84 | t = 2.17 (52.57) | = .52 | ||

Note. p values were adjusted using the Holm–Bonferroni method for multiple comparisons. df = degrees of freedom; YNH = younger group with normal hearing; ONN = older group with near-normal hearing; OHI = older group with hearing impairment.

p value is less than .05.

p value is less than .01.

p value is less than .001.

For both Models B and C, further analyses were conducted to evaluate whether the inclusion of random slopes for effects of noise type and context would significantly alter the model. The results were the same for both models and justify the use of an intercept-only random effects structure. The inclusion of random slope for noise type resulted in a nearly singular fit, suggesting that there was not sufficient variability remaining. The inclusion of random slope for context did not result in a singular fit; however, likelihood ratio testing suggested that the random slope for context did not explain a significant portion of variance in either model.

Model B

As indicated in Table 4, there was a significant main effect of participant group (F = 6.76, p < .01) and a significant main effect of context (F = 11.04, p < .01). There was not a significant effect of noise type or any significant interactions (p > .05). Figure 5 displays group-mean word recall, for each participant group, in each noise-type and sentence-predictability condition.

Figure 5.

Mean word recall in percent correct (and standard errors) as a function of participant group for each noise type. Semantic predictability conditions are plotted in separate panels. YNH = younger group with normal hearing; ONN = older group with near-normal hearing; OHI = older group with hearing impairment; SSN = speech-shaped noise; SMN = speech-modulated noise; 3T = three-talker babble.

The YNH group recalled more words than the ONN and OHI groups across conditions (p < .05). Averaged across noise types and predictability condition, the YNH group, on average, recalled 15.3 percentage points more words than did the ONN group and 19.7 percentage points more words than did the OHI group. Word recall for the ONN and OHI groups did not differ (p = .45). The significant main effect of context simply reflects overall better recall in the HP conditions compared with LP conditions.

Of primary interest to this study, there were no significant differences in recall across the noise types and no interactions involving noise type. Maximum differences in recall between noise types in any predictability condition were 10.8 percentage points, 6.9 percentage points, and 7.4 percentage points for the YNH, ONN, and OHI groups, respectively. This suggests that noise type did not significantly influence word recall in the current paradigm, in which the confound of overall performance level (and presumably overall task difficulty) was controlled. These results prompted the construction of Model C to assess whether the general presence of noise, rather than type of noise, impacted word recall.

Model C

As indicated in Table 5, there was a significant main effect of participant group (F = 5.44, p < .05), a significant main effect of noise condition (F = 16.68, p < .001), and a significant main effect of context (F = 5.79, p < .05). There was also a significant three-way interaction between participant group, noise condition, and context (F = 5.83, p < .01). No two-way interactions were significant (p < .05). Figure 6 displays group-mean word recall for each participant group, in quiet and pooled-noise conditions, in each sentence-predictability condition.

Figure 6.

Mean word recall in percent correct (and standard errors) as a function of participant group in quiet versus pooled noise conditions. Semantic predictability conditions are plotted in separate panels. YNH = younger group with normal hearing; ONN = older group with near-normal hearing; OHI = older group with hearing impairment.

The significant effect of participant group likely reflects the consistent trend for the YNH group to recall more words than the ONN and OHI groups. Averaged across conditions, the YNH group recalled 13.8 percentage points more words than the ONN group and 18.8 percentage points more words than the OHI group. The significant effects of noise condition and sentence predictability simply reflect greater word recall in quiet relative to noise, and in HP relative to LP sentences, when collapsed across all conditions.

These results suggest that the YNH group performed well on word recall in all conditions—in quiet and noise, and in HP and LP. Turning to the older listeners, the significant interaction indicates four contrasts of interest: These are labeled (1)–(4) in Table 5. Considering higher recall to reflect “better” performance simplifies the discussion. Contrast (1) indicates that the OHI group performed better in quiet than in noise, in the HP condition, and (2) suggests that the OHI group performed better in HP context than in LP, when in quiet (noting the p value of .08). So the OHI group appeared able to use the HP context to perform better in quiet than noise but was less able to perform well, even in quiet, without sentence context. This effect is evident in the top and center panels of Figure 6. Contrast (3) indicates that the ONN group performed better in quiet than in noise, but in the less contextually supportive LP condition, and (4) indicates that performance in noise dropped for these participants from HP to LP. Hence, the ONN group displayed the advantage of quiet regardless of sentence context while they also appeared to benefit from HP context to perform well in noise.

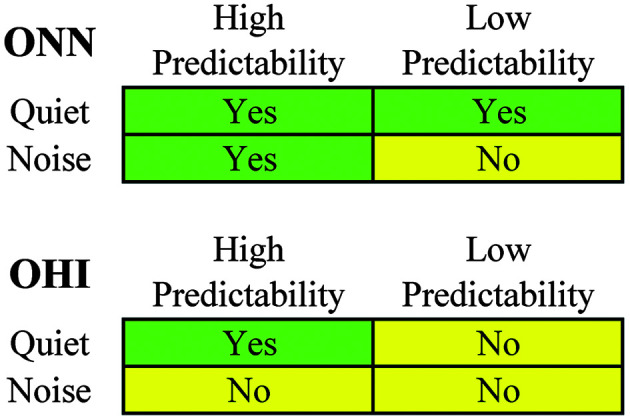

Thus, if quiet versus noise and HP versus LP sentence context are considered as factors arranged in a 2 × 2 array, then it may be considered that the current ONN group performed well on the word-recall task whenever quiet or HP context was available (three of four squares), whereas the OHI group performed well only when quiet and HP were both available (one of four squares, see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

A 2 × 2 array indicating the noise or sentence-predictability conditions in which older subject groups performed well on the word-recall task (Yes = performed well; No = did not). The Yes versus No distinctions are supported by probabilities of .05 or lower, with the exception of one, where the difference was p = .08 (OHI, quiet, high vs. low predictability). ONN = older group with near-normal hearing; OHI = older group with hearing impairment.

Discussion

Experiment 1

The results in Figure 4 (Model A) are in accord with those previously shown in the literature. The OHI group demonstrated the most difficulty in all noise types. Known threshold and suprathreshold auditory detriments that accompany sensorineural hearing loss, as well as suprathreshold auditory deficits associated with aging, likely contributed to these results (for a review, see Gordon-Salant, 2006). Listeners in all groups required the highest SNR-70 in the 3T noise type. Previous studies have shown that higher (more favorable) SNRs are required to achieve the same performance in babble compared with nonspeech noise types (Desjardins & Doherty, 2012; Healy et al., 2013, 2014). This result was also consistent with theories related to informational (Brungart et al., 2006) or perceptual masking (Carhart et al., 1969). In contrast, the 3T noise type offered more opportunities for spectral glimpsing compared with SMN and more spectral and temporal glimpsing compared with SSN. Furthermore, this potential advantage was offset, perhaps by the informational or speechlike component of the 3T noise type, necessitating higher SNRs to achieve equal performance for all groups.

Relative performance between SSN and SMN varied with participant group. The YNH group did show the anticipated benefit from masking release (a 2-dB effect between SMN and SSN). The ONN group demonstrated minimal masking release, consistent with studies showing that older listeners experience reduced benefit from background modulation during speech recognition. Furthermore, the OHI group not only demonstrated a lack of masking release but they also appear to have shown some degree of modulation interference, as this group required an average 2.6 dB more favorable signal in SMN to achieve the same performance in SSN. The lack of masking release in listeners with hearing impairment was shown to be directly related to broad auditory tuning by the classic work of ter Keurs et al. (1993). Larsby et al. (2005) also showed that older listeners with hearing impairment have more difficulty in noise having a high degree of temporal fluctuation.

Experiment 2

Figure 5 (Model B) displays word recall (rather than recognition) and shows that the YNH group demonstrated the best recall in all noise types. This is consistent with studies showing that age decreases performance on cognitive tasks, word-recall tasks, and dual-task paradigms evaluating listening effort (Desjardins & Doherty, 2012; Gosselin & Gagné, 2011; Schoof & Rosen, 2014; Tun et al., 2009). On average, the ONN group showed numerically higher recall in high-predictability conditions than the OHI group; however, this result was not significant in Table 4. Interestingly, the effect of noise type was also nonsignificant in this model, which suggests that recall performance may not be directly linked to the nature of target glimpses available.

Results of Model C are plotted in Figure 6. These results are consistent with and complementary to Model B. The YNH group again demonstrated the best recall overall, most notably in noise. Also as shown in Model B, overall pooled performance between ONN and OHI groups was similar, suggesting that hearing impairment did not significantly impact recall in quiet or in noise. Considering both Models B and C, it appears that the presence of noise impacted recall but the type of noise was not a significant factor, as there was a significant effect of noise on recall in Model C but no effect of noise type in Model B.

Model C also offers new comparisons between quiet and noise. Specifically, the significant three-way interaction indicates that the impact of noise on recall varied depending on the population and context condition (see Figure 7). The auditory and cognitive characteristics of the YNH group rendered them overall robust to noise, regardless of whether contextual support was available. The ONN group was also somewhat robust to the impact of noise; however, the availability of context seemed to play a greater role, as recall in this group only suffered when noise and low context coexisted. This suggests that recall by ONN listeners is most impacted in noisy conversations that lack supportive context and, that, when context is available as a listening aid, the impact of noise is mitigated.

For the OHI group, it appears that auditory deficits accompanying sensorineural hearing loss rendered this group widely debilitated by noise. In fact, referring again to Figures 6 and 7, recall was overall poor for the OHI group in all conditions except for the most ideal condition of combined quiet and high predictability. The impact of noise in this group nullified the potential benefit of contextual support seen in the results of the ONN group. However, in conversations lacking context, the presence of noise did not introduce additional burden, evidenced by the mere 0.39 percentage point difference between quiet and noise conditions. For the OHI population, both context and the absence of noise appear needed for successful recall performance.

The lack of a significant effect of noise type in this study is generally consistent with the results of Desjardins and Doherty (2012). We suspect that the current results may be in part due to two specific aspects of our methodology: the decision to fix performance rather than SNR and the word-recall measure used as the secondary task in a dual-task paradigm. Some studies have noted that fixing performance level rather than SNR changes the magnitude of age-related effects on listening effort and discourse comprehension. Schneider et al. (2000) showed age-related differences in discourse comprehension that were significant in fixed SNR conditions became nonsignificant when the perceptual difficulty of the task rather than SNR was equated. Desjardins and Doherty (2012) also described a similar theory while comparing their results with Gosselin and Gagné (2011), stating that a greater difference in listening effort may have been observed between younger and older listeners in conditions fixed by SNR compared with conditions fixed by performance. The process of varying SNR on an individual basis to match performance level may have factored out individual characteristics of glimpsing/noise type as well as individual characteristics related to aging and cognition.

The decision to time reverse the 3T noise type likely limited semantic or lexical interference that may affect listener performance. This decision was in accord with the current focus on spectrotemporal aspects of the maskers and glimpsing. Furthermore, it does introduce a secondary question involving whether there would have been a significant effect of noise type on recall if the speechlike noise had not been time reversed. Semantic or lexical interference is well known to impact speech recognition, especially for older adults (Tillman et al., 1973). Hoen et al. (2007) described the masking potential of forward and reversed speech babble. When the number of talkers was relatively high (six or eight), both maskers produced similar masking of target speech (similar intelligibility). Furthermore, when the number of talkers was lower (four), the forward speech produced more masking/lower intelligibility than the reversed speech. These results highlight the role of identifiable speech in informational masking—the masker having a smaller number of talkers likely possesses more readily identifiable speech/more lexical content and therefore more lexical interference. Accordingly, the current 3T noise may have produced additional masking and a higher (require a more favorable) SNR-70 had it not been time reversed. Furthermore, it is not clear whether the use of a forward speech masker would have produced a disassociation between intelligibility and word recall, different from that observed currently for time-reversed speech.

The current results may be compared with those of the Repeat-Recall Test (Kuk et al., 2019; Slugocki et al., 2018). This test consists of thematically related sentence lists in quiet or in noise at a fixed SNR. Each sentence is repeated after its presentation to assess recognition, and then as many sentences as possible are repeated again after a list of six sentences to assess recall. Listeners also report effort and duration of time spent concentrating in those conditions. Both high- and low-context conditions and normative data from NH listeners are available. Kuk et al. (2021) assessed performance of NH listeners on this test using two noise types. It was found that SSN produced more masking/less recognition than did two-talker babble (see their Figure 1). This result stands in contrast to those of the current Experiment 1 but can be understood in terms of the additional glimpsing opportunities associated with fewer talkers. The additional lexical interference associated with fewer talkers, which would tend to increase masking, is apparently secondary to this primary acoustic effect of masking and glimpsing. In accord with the current Experiment 2, these authors observed little if any consistent difference in recall between masker types (see their Figure 3).

As shown in Table 2, there was a significant relationship between participant group and cognitive performance. This may suggest that stratifying participants in the manner performed currently (YNH, ONN, and OHI) can largely account for cognitive differences between populations. To evaluate this theory, three additional statistical models were constructed. Models A.2, B.2, and C.2 were used to evaluate Models A, B, and C with the addition of the three cognitive tests as covariates. All other parameters of the models remained the same. In Experiment 1, where the measure was recognition, a significant effect of listener group was observed both in the primary analysis (Model A, Table 3) and in the additional analysis involving cognitive covariates. In contrast, when recall was the measure in Experiment 2, the primary analyses revealed a significant effect of listener group (Models B and C, Tables 4 and 5), whereas the effect of listener group became nonsignificant in the additional analysis involving cognitive covariates. Details of these additional analyses will be made available upon reasonable request to the authors. As the task of Experiment 1 was rooted in more basic perception abilities, it is perhaps unsurprising that adjusting for cognition did not lead to any significant change in results. In contrast, the recall task of Experiment 2 was designed to tap cognition/working memory, and so it is perhaps unsurprising that participant group differences were diminished after adjusting for cognition. These results suggest that stratifying listeners into groups as performed currently has the potential to account for much of the broad cognitive differences that exist across listeners, at least for the simple task of word recall and for listeners that differ widely in age and hearing status.

Conclusions

The primary research objective in this study was to assess the manner in which noise type interacts with age and hearing status to influence word recall while controlling for individual differences in glimpsing and noise tolerance and therefore overall task difficulty. The results may be summarized as follows:

The stratification of listeners into YNH, ONN, and OHI groups and the use of SNR conditions producing equivalent word recognition and therefore likely similar difficulty appears to have limited the differential effects of cognitive skills on word recall performance.

There was no evidence supporting an effect of these noise types on word recall for any participant group or context condition. It seems that the general presence of noise, rather than noise type, impacted recall with poorer recall noted in noise conditions compared with quiet conditions.

Younger listeners with NH were highly robust to the detrimental effects of noise, demonstrating higher word recall than older listeners with near-normal hearing and with hearing loss in all conditions.

Older listeners with near-normal hearing were able to take advantage of quiet backgrounds or high sentence context (or both) to perform well on word recall. Recall was only reduced when background noise and a lack of context were concurrently present. In contrast, the older listeners with hearing impairment required both quiet backgrounds and high sentence context to perform well on word recall. A lack of either advantage was detrimental to these listeners.

Data Availability Statement

Additional data will be made available upon reasonable request to the authors.

Acknowledgments

This work was drawn from a dissertation submitted to The Ohio State University Graduate School by B.L.C., under the direction of E.W.H. It was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (R01 DC015521 to E.W.H.), The Ohio State University Alumni Grant for Graduate Research and Scholarship, and The Ohio State University Graduate School Presidential Fellowship. The authors are grateful for the assistance of Jordan Vasko, Victoria Sevich, and Devan Lander.

Funding Statement

This work was drawn from a dissertation submitted to The Ohio State University Graduate School by B.L.C., under the direction of E.W.H. It was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (R01 DC015521 to E.W.H.), The Ohio State University Alumni Grant for Graduate Research and Scholarship, and The Ohio State University Graduate School Presidential Fellowship.

References

- Akeroyd, M. A. (2008). Are individual differences in speech reception related to individual differences in cognitive ability? A survey of twenty experimental studies with normal and hearing-impaired adults. International Journal of Audiology, 47(Suppl. 2), S53–S71. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992020802301142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American National Standards Institute. (1987). ANSI S3.39 (R2012). American National Standard Specifications for Instruments to Measure Aural Acoustic Impedance and Admittance(Aural Acoustic Immittance).

- American National Standards Institute. (2004). ANSI S3.21 (R2009). American National Standard Methods for Manual Pure-Tone Threshold Audiometry.

- American National Standards Institute. (2010). ANSI S3.6, American National Standard Specification for Audiometers.

- Assmann, P. , & Summerfield, Q. (2004). The perception of speech under adverse conditions. In Speech Processing in the Auditory System (Vol. 18, pp. 231–308). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-21575-1_5 [Google Scholar]

- Baer, T. , & Moore, B. C. J. (1993). Effects of spectral smearing on the intelligibility of sentences in noise. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 94(3), 1229–1241. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.408176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-David, B. M. , & Schneider, B. A. (2009). A sensory origin for color-word Stroop effects in aging: A meta-analysis. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 16(5), 505–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825580902855862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilger, R. C. , Nuetzel, J. M. , Rabinowitz, W. M. , & Rzeczkowski, C. (1984). Standardization of a test of speech perception in noise. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 27(1), 32–48. https://doi.org/10.1044/jshr.2701.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brungart, D. S. , Chang, P. S. , Simpson, B. D. , & Wang, D. (2006). Isolating the energetic component of speech-on-speech masking with ideal time–frequency segregation. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 120(6), 4007–4018. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.2363929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, D. , & Dillon, H. (1986). The National Acoustic Laboratories' (NAL) new procedure for selecting the gain and frequency response of a hearing aid. Ear and Hearing, 7(4), 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003446-198608000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carhart, R. , Tillman, T. W. , & Greetis, E. S. (1969). Perceptual masking in multiple sound backgrounds. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 45(3), 694–703. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.1911445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, M. P. (2006). A glimpsing model of speech perception in noise. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 119(3), 1562–1573. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.2166600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosetti, M. , Pinkston, J. , Flores, J. , Friedmann, D. , Jones, C. , Roland, J., Jr. , & Waltzman, S. (2016). Neurocognitive testing and cochlear implantation: Insights into performance in older adults. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 11, 603–613. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S100255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneman, M. , & Carpenter, P. A. (1980). Individual differences in working memory and reading. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 19(4), 450–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(80)90312-6 [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins, J. L. , & Doherty, K. A. (2012). Age-related changes in listening Effort for various types of masker noises. Ear and Hearing, 34(3), 261–272. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0b013e31826d0ba4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirks, D. D. , Wilson, R. H. , & Bower, D. R. (1969). Effect of pulsed masking on selected speech materials. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 46(4B), 898–906. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.1911808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubno, J. R. , Horwitz, A. R. , & Ahlstrom, J. B. (2002). Benefit of modulated maskers for speech recognition by younger and older adults with normal hearing. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 111(6), 2897–2907. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.1480421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festen, J. M. , & Plomp, R. (1990). Effects of fluctuating noise and interfering speech on the speech-reception threshold for impaired and normal hearing. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 88(4), 1725–1736. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.400247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogerty, D. , Xu, J. , & Gibbs, B., III. (2016). Modulation masking and glimpsing of natural and vocoded speech during single-talker modulated noise: Effect of the modulation spectrum. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 140(3), 1800–1816. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.4962494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullgrabe, C. (2013). Age-dependent changes in temporal-fine-structure processing in the absence of peripheral hearing loss. American Journal of Audiology, 22(2), 313–315. https://doi.org/10.1044/1059-0889(2013/12-0070) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, R. H. , Bacon, S. P. , & Williams, E. J. (2007). An examination of speech recognition in a modulated background and of forward masking in younger and older listeners. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 50(4), 857–864. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2007/060) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasberg, B. R. , & Moore, B. C. (1986). Auditory filter shapes in subjects with unilateral and bilateral cochlear impairments. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 79(4), 1020–1033. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.393374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasberg, B. R. , & Moore, B. C. (1990). Derivation of auditory filter shapes from notched-noise data. Hearing Research, 47(1‑2), 103–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-5955(90)90170-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Salant, S. (2006). Speech perception and auditory temporal processing performance by older listeners: Implications for real-world communication. Seminars in Hearing, 27(4), 264–268. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2006-954852 [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin, P. A. , & Gagné, J. P. (2011). Older adults expend more listening effort than young adults recognizing speech in noise. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 54(3), 944–958. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2010/10-0069) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grose, J. H. , Mamo, S. K. , & Hall, J. W., III. (2009). Age effects in temporal envelope processing: Speech unmasking and auditory steady state responses. Ear and Hearing, 30(5), 568–575. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181ac128f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, H. A. , & Arlinger, S. D. (1994). Masking of speech by amplitude-modulated noise. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 95(1), 518–529. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.408346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy, E. W. , & Steinbach, H. M. (2007). The effect of smoothing filter slope and spectral frequency on temporal speech information. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 121(2), 1177–1181. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.2354019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy, E. W. , Yoho, S. E. , Chen, J. , Wang, Y. , & Wang, D. L. (2015). An algorithm to increase speech intelligibility for hearing-impaired listeners in novel segments of the same noise type. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 138(3), 1660–1669. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.4929493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy, E. W. , Yoho, S. E. , Wang, Y. , Apoux, F. , & Wang, D. L. (2014). Speech-cue transmission by an algorithm to increase consonant recognition in noise for hearing-impaired listeners. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 136(6), 3325–3336. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.4901712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy, E. W. , Yoho, S. E. , Wang, Y. , & Wang, D. (2013). An algorithm to improve speech recognition in noise for hearing-impaired listeners. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 134(4), 3029–3038. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.4820893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoen, M. , Meunier, F. , Grataloup, C.-L. , Pellegrino, F. , Grimault, N. , Perrin, F. , Perrot, X. , & Collet, L. (2007). Phonetic and lexical interferences in informational masking during speech-in-speech comprehension. Speech Communication, 49(12), 905–916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.specom.2007.05.008 [Google Scholar]

- Humes, L. E. (1996). Speech understanding in the elderly. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 7(3), 161–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humes, L. E. , Dubno, J. R. , Gordon-Salant, S. , Lister, J. J. , Cacace, A. T. , Cruickshanks, K. J. , Gates, G. A. , Wilson, R. H. , & Wingfield, A. (2012). Central presbycusis: A review and evaluation of the evidence. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 23(8), 635–666. https://doi.org/10.3766/jaaa.23.8.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IEEE. (1969). IEEE recommended practice for speech quality measurements. IEEE Transactions on Audio and Electroacoustics, 17, 225–246. [Google Scholar]

- Kjellberg, A. , Ljung, R. , & Hallman, D. (2008). Recall of words heard in noise. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 22(8), 1088–1098. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1422 [Google Scholar]

- Knight, S. , & Heinrich, A. (2017). Different measures of auditory and visual Stroop interference and their relationship to speech intelligibility in noise. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. Article 230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeritzer, M. A. , Rogers, C. S. , Van Engen, K. J. , & Peelle, J. E. (2018). The impact of age, background noise, semantic ambiguity, and hearing loss on recognition memory for spoken sentences. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 61(3), 740–751. https://doi.org/10.1044/2017_JSLHR-H-17-0077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuk, F. K. , Potts, L. , Valente, M. , Lee, L. , & Picirrillo, J. (2003). Evidence of acclimatization in persons with severe-to-profound hearing loss. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 14(2), 84–99. https://doi.org/10.3766/jaaa.14.2.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuk, F. , Slugocki, C. , & Korhonen, P. (2019). An integrative evaluation of the efficacy of a directional microphone and noise reduction algorithm under realistic signal-to-noise ratios. Journal of American Academy Audiology, 31(4), 262–270. https://doi.org/10.3766/jaaa.19009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuk, F. , Slugocki, C. , Ruperto, N. , & Korhonen, P. (2021). Performance of normal-hearing listeners on the Repeat-Recall test in different noise configurations. International Journal of Audiology, 60(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2020.1807626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]