Abstract

BACKGROUND

Thoracic surgery (TS) residency positions are in high demand. There is no study describing the nationwide attributes of successful matriculants in this specialty. We examined the characteristics of TS resident applicants and identified factors associated with acceptance.

METHODS

Applicant data from 2014 to 2017 application cycles was extracted from the Electronic Residency Application System and stratified by matriculation status. Medical education, type of general surgery residency, and research achievements were analyzed. The number of peer-reviewed publications and the corresponding impact factor for the journals where they were published were quantified.

RESULTS

There were 492 applicants and 358 matriculants. The overall population was primarily male (79.5%), white (55.1%), educated at United States allopathic medical schools (66.5%), and trained at university-based general surgery residencies (59.6%). Education at United States allopathic schools (odds ratio [OR], 2.54; P< .0001), being a member of the American Osteopathic Association (OR, 3.27; P = .021), general surgery residency affiliation with a TS residency (OR, 2.41; P = .0003) or National Cancer Institute designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (OR, 1.76; P = .0172), and being a first-time applicant (OR, 4.71, P< .0001) were independently associated with matriculation. Matriculants published a higher number of manuscripts than nonmatriculants (median of 3 vs 2, P< .0001) and more frequently published in higher impact journals (P< .0001).

CONCLUSIONS

Our study includes objective and quantifiable data from recent application cycles and represents an in-depth examination of applicants to TS residency. The type of medical school and residency, as well as academic productivity, correlate with successful matriculation.

There is growing interest among resident physicians in pursuing subspecialty training.1,2 Across all specialties, approximately 4 of 5 residents training in the United States (US) choose to pursue subspecialty training.2,3 After successful completion of a general surgery (GS) residency, several options are available to graduates, and interest in subspecialty training has been particularly marked among general surgeons.1–7 This is the result of several factors, including a demand for specialists, financial incentives, and a growing concern among mentors and trainees alike that GS residency may not provide sufficient training to perform complex operations.1,3,6,7 Despite this, the number of available training positions rarely meets the demand.

Once among the most sought-after postgraduate disciplines, traditional cardiac surgery training has not seen the same increase in interest compared with other fields such as colorectal surgery, pediatric surgery, and complex general surgical oncology.8 Several studies have examined the causes of reduced interest in cardiac surgery training in the early 2000s.5,8,9 Major contributions to this shift include reduced open cardiac surgical volume and an increased emphasis on lifestyle when making career decisionss.8 Nevertheless, in recent years, a growing demand for specialized surgical care for patients diagnosed with thoracic malignancies has increased the demand for thoracic-focused tracts within thoracic surgery (TS) residencies. In the early 2000s, the number of residency positions outnumbered the available applicants.5 However, an updated description of the competitiveness and positions per applicant is not available.

In this study, we examined the pool of recent candidates applying to North American TS residencies to identify trends in applicant demand for residency positions as well as the characteristics and attributes of successful matriculants. We provide a detailed analysis of the candidates from all recent nonintegrated TS residency application cycles available within the Electronic Residency Application System (ERAS) and hypothesized that productivity, as measured by publication record, was associated with matriculation into a TS residency. Our aim is to provide quantitative data to interested parties, such as current and future applicants and TS residency program directors, highlighting the characteristics and qualifications of matriculants to training programs in this field. Recent studies have described applicant factors associated with successful matriculation into competitive surgical fellowships such as complex general surgical oncology, pediatric surgery, hepatopancreatobiliary, and endocrine surgery fellowships; however, no such study has examined TS residency applicant and matriculant characteristics.10–14

MATERIAL AND METHODS

DATA ACQUISITION.

Approval was granted for the release of deidentified data based on an existing data sharing contract between the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and the National Institutes of Health. The study was also deemed exempt by the National Institutes of Health Institutional Review Board. All data originated from ERAS for the 2014 to 2017 application cycles, which correspond to matriculation dates in August 2015 to 2018. All data were collected from ERAS directly by data operations specialists at the AAMC and deidentified before acquisition by our group to protect applicant privacy.

Also collected were archived statistical data from the National Residency Match Program for TS residency from 1998 to 2017. Variables of interest included the number of applicants and the number of positions available per year, and both were used to calculate the ratio of applicants to available positions for each year.5,9

TS residency programs are approved by the American Board of Thoracic Surgery and by the ACGME. Only independent, nonintegrated programs (2- and 3-year TS residencies) were considered in this analysis. Medical student applicants to integrated programs (I6) are outside the scope of this analysis. Approved independent programs receive all applications for TS residency positions through ERAS, and therefore, all applicants to these programs in 2014 to 2017 were included in this analysis. Between 2014 and 2017, an average of 68 programs offered TS residency training positions. Applicants were identified and stratified based on matriculation vs nonmatriculation.

To determine whether an ERAS applicant matriculated into a TS residency, applicant identification numbers available in the AAMC’s GME Track were cross-referenced with the rosters of the specified TS residency programs. Only data from the most recent ERAS application were analyzed for applicants who applied more than once.

Applicant demographics, premedical qualifications, medical school type, GS residency characteristics, and publication data were retrieved by AAMC data specialists and provided to our group for further analysis. Baseline information on applicants’ GS residency program and corresponding affiliation was gathered by means of the American Medical Association’s Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database (FREIDA) and matched to their ACGME identification number. According to FREIDA, GS residency programs are classified as university based, community based, or community based/university affiliated. Programs falling outside of these classifications were labeled as military or unknown.

Our group then established whether an applicant trained at a GS residency with an affiliated TS residency program or with a National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (NCI-CCC) and examined how this influenced matriculation. Institutional and hospital affiliation of an applicant’s home GS residency program was also determined using FREIDA classifications. A GS residency program was considered linked with an institution offering a TS residency training position if a GS resident rotated at that institution or on that service for at least 1 month during GS residency. This was verified by examining the GS residency program’s curriculum. In addition, a GS residency was considered linked to an NCI-CCC if a GS resident rotated at that institution. Note that not all TS residencies are based at an NCI-CCC and vice versa.

Finally, all published manuscripts authored by each applicant were quantified, and the name of each journal in which an applicant published was recorded. An applicant was given credit for a publication if they were among the authors listed on a scientific or clinical manuscript. Articles with the status of “under review” or “accepted but not yet published” were excluded. To gain insight into applicants’ publication records, data were gathered on the impact factor (IF) of the journals in which an applicant’s manuscripts were published. Journal IFs were obtained from Thomson Reuters Journal Citation Reports (Toronto, ON, Canada) for the year 2017 as calculated by Clarivate Analytics (London, United Kingdom) based on citation metrics.

As described previously, journals were ranked into academic tiers based on IF, with low-tier journals defined by IF of less than 2.5, middle-tier as IF 2.5 to 9.9, and high-tier possessing an IF of 10 or more.10 Applicants were categorized based on the single highest IF publication listed on their application. Journals with no IF published by Clarivate Analytics were classified as low tier. Individuals who did not have any publications listed were classified as tier 0.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS.

Applicant characteristics are reported as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared using the Fisher exact test, and continuous variables were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Stratification according to matriculation status was performed to identify variables associated with successful matriculation. Comparisons are reported as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to demonstrate the association of potentially important factors on matriculation. The Cochran-Armitage trend test was applied to determine the association of journal IF on matriculation status. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 software (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

APPLICATION TRENDS.

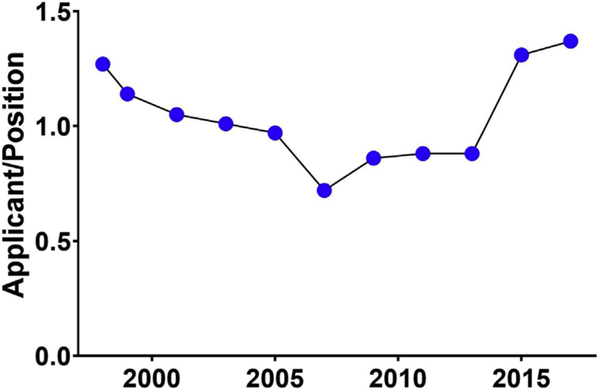

We examined the number of applicants and available positions between 1998 and 2017 and found that between 1997 and 2007, the number of applications per available position trended down at a mean rate of −4.7% per year despite a relatively stable number of positions (mean Δ−1.2%). After 2007, however, the demand for TS residency positions increased substantially and is most evident in the recent trend for applications that outnumber available positions (20152017). The mean rate of change in applicants per position over the decade from 2007 to 2017 was 7.3% annually. This was not explained by the steady decline in the number of positions available during this period, which averaged −3.9% annually (Figure 1).9 These numbers provide strong evidence that successful matriculation into TS residency is becoming increasingly competitive.

FIGURE 1.

Graph shows the trend in the annual ratio of applicants per position between the 1998 and 2017 applications cycles. Data are shown every 2 years for this 20-year period.

APPLICANT CHARACTERISTICS.

AAMC data indicate 492 applicants were included in the ERAS TS residency applicant pool from 2014 to 2017. The median applicant age was 32.3 years, and the overall population was primarily male (79.5%), White (55.1%), and educated at a US allopathic medical school (66.5%) (Table 1). Of those educated at an allopathic school, 14.7% indicated induction into the American Osteopathic Association (AOA). Most applicants completed GS residency at a university-affiliated program (59.6%), but most did not train at an NCI-CCC (37.4%) or TS residency-affiliated program (39.8%) (Table 1). The median reported number of publications authored per applicant was 3 (mean, 5.8; range, 0–94), and the median IF of journals where work was published was 2.89 (mean, 4.02; range, 0–79.26).

TABLE 1.

Demographic Data for Thoracic Surgery Residency Applicants Stratified by Matriculation Status (2014–2017)

| Variable | Total (N = 492) | Nonmatriculant (n = 134) | Matriculant (n = 358 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median, y | 32.3 | 32.9 | 32.0 |

| Female sex | 101 (20.5) | 30 (22.4) | 71 (19.8) |

| Race/ethnicitya | |||

| White | 271 (55.1) | 57 (42.5) | 214 (59.8) |

| Black/African American | 22 (4.5) | 8 (6.0) | 14 (3.9) |

| Asian | 93 (18.9) | 28 (20.9) | 65 (18.2) |

| Hispanic/Latino/Spanish origin | 28 (5.7) | 7 (5.2) | 21 (5.9) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) |

| Other | 12 (2.4) | 5 (3.7) | 7 (2.0) |

| Unknown | 15 (3.0) | 3 (2.2) | 12 (3.4) |

| Non-United States citizen | 67 (13.6) | 30 (22.4) | 37 (10.3) |

| AOA memberb | 48 (14.7) | 4 (5.9) | 44 (17.0) |

| Medical school designation | |||

| United States allopathic | |||

| Public | 195 (36.6) | 40 (29.9) | 155 (43.3) |

| Private | 132 (26.8) | 28 (20.9) | 104 (29.1) |

| United States osteopathic | 38 (7.7) | 15(11.2) | 23 (6.4) |

| Canadian | 10 (2.0) | 4 (3.0) | 6(1.7) |

| International | 117 (23.8) | 47 (35.1) | 70 (19.6) |

| GS residency designation | |||

| Academic/university affiliated | 293 (59.6) | 56 (41.8) | 237 (66.2) |

| Community based/university affiliated | 99 (20.1) | 35 (26.1) | 38 (10.6) |

| Community based | 51 (10.4) | 13 (9.7) | 64 (17.9) |

| Military | 7(1.4) | 0(0) | 7 (2.0) |

| Unknown | 42 (8.5) | 30 (22.4) | 12 (3.4) |

| TS residency-affiliated GS residency | 196 (39.8) | 29 (21.6) | 167 (46.6) |

| NCI Cancer Center-affiliated GS residency | 184 (37.4) | 32 (23.9) | 152 (42.5) |

| Reapplicant to TS | 47 (9.6) | 28 (20.9) | 19 (5.3) |

Data are presented as n (%) or as indicated otherwise. AOA, American Osteopathic Association; GS, general surgery; NCI, National Cancer Institute; TS, thoracic surgery.

Applicants allowed to choose multiple, therefore numbers may not add to the total of unique applicants

AOA status applies to applicants from United States allopathic/MD-granting medical schools only (n = 327).

FACTORS DIFFERENTIATING MATRICULANTS AND NONMATRICULANTS.

Of the 492 applicants included in this analysis, 358 (72.8%) matriculated to a TS residency and 134 (27.2%) did not. Between 2014 and 2017, 47 applicants (9.5%) applied more than once in ERAS, and 19 (40.4% of reapplicants and 14.1% of nonmatriculants) eventually matriculated into a TS residency. Characteristics of matriculants and nonmatriculants are detailed in Table 1. The mean Medical College Admission Test score of those who matriculated was significantly higher than those who did not (30.5 vs 28, P < .0001). Similarly, compared with nonmatriculants, a higher percentage of matriculants attended US allopathic medical schools (72.4% vs 50.8%, P < .0001). Of the 327 applicants from US allopathic medical schools, 48 (14.7%) indicated AOA membership, and 44 (91.7%) of these applicants matriculated (P = .0205). Furthermore, matriculants were more likely to be White (59.8% vs 42.5%, P = .0205) and trained at GS residencies affiliated with a TS residency (46.6% vs 21.6%, P = .0003) and/or NCI-CCC (42.5% vs 23.9% P = .0172) (Table 1). Odds ratio analysis of these factors is reported in Table 2. The odds ratios for residents matriculating into fellowship programs by sex and race/ethnicity have fluctuated during the 4-year period being analyzed; however, there is no significant or consistent trend (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Applicant Characteristics Associated with Matriculation

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 0.85 | 0.53–1.39 | .5328 |

| Non-White racea | 0.59 | 0.38–0.92 | .0205 |

| United States allopathic medical schoolb | 2.54 | 1.68–3.83 | <.0001 |

| AOA memberc | 3.27 | 1.13–9.46 | .0205 |

| University-affiliated surgical residencya | 0.96 | 0.49–1.85 | >.999 |

| TS residency-affiliated GS residencya | 2.41 | 1.50–3.89 | .0003 |

| NCI Cancer Center-affiliatec GS residencya | 1.76 | 1.10–2.81 | .0172 |

| First-time TS residency applicant | 4.71 | 2.53–8.78 | <.0001 |

AOA, American Osteopathic Association; CI, confidence interval; GS, general surgery; NCI, National Cancer Institute; TS, thoracic surgery.

Applicants with unknown data for this comparison were excluded. Non-United States citizens were additionally excluded when comparing race only

Includes both public and private United States allopathic medical schools. Compared with non-United States medical schools

AOA membership applies to applicants from US allopathic medical schools only. Comparison made between members and nonmembers/no answer.

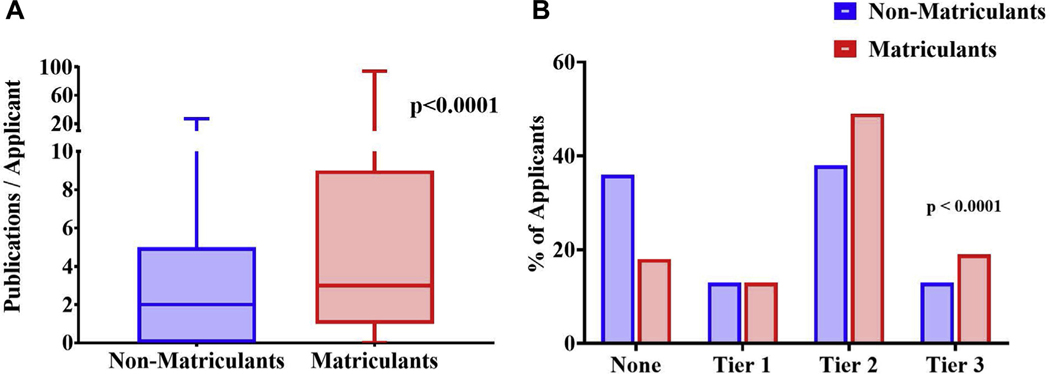

The median number of publications reported by applicants who matriculated was significantly higher than that of nonmatriculants (3 [95% CI, 1–9] vs 2 [95% CI, 0–5], P < .0001) (Figure 2A). The IFs of the journals where applicants’ work was published, when categorized by IF tier, were also significantly different between groups. Whereas nonmatriculants were more likely to have no publications (36% vs 18%), matriculants more often published in tiers 2 or 3 during the study period. Using the Cochran-Armitage test, we observed a significantly stronger trend between matriculation and achieving publication in journals with increasingly higher IFs compared with nonmatriculants (P < .0001) (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

(A) Box-and-whisker plot compares median number of peer-reviewed publications for matriculants vs nonmatriculants to thoracic surgery residency programs (P < .0001). The line in the middle of each box indicates the median; the top and bottom borders of the box mark the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively, and the whiskers mark the 90th and 10th percentiles. (B) Grouped bar graph compares the percentage of matriculants and nonmatriculants in each impact factor (IF) of highest publication group. The 4 groups include none (no publications), tier 1 (IF<2.5), tier 2 (IF 2.5–9.9), and tier 3 (IF ≥10). Analysis of the trend in matriculation based on IF of highest category was performed using Cochran-Armitage analysis (P < .0001)

COMMENT

As has been described for other surgical fellowships, the number of applicants to TS residency is considerably greater than the number of available positions.10,11 Nevertheless, very little data exist describing the qualities of the applicants who successfully matriculate into these positions. We analyzed the most recent objective and quantifiable source data on all applicants from the most recent years. These data were submitted through ERAS and are available from the AAMC (application cycles 2014–2017). Our study allows us to provide a more generalized and detailed description of all quantifiable metrics of the applicants predictive of matriculation. Our findings provide insight and potential guidance to those interested in a career in TS, current and future applicants, and to TS residency program directors. As in other similar studies, we acknowledge that several applicant factors that are likely to contribute to matriculation could not be quantified or included in our analysis.1,10–12,14 Neverthe-less, our analysis offers an overview of metrics describing applicants’ medical education, GS residency training, and research accomplishments.

Applicants who attended an allopathic medical school in the US were more likely to achieve matriculation to TS residency. This is commonly valued in the surgical and other medical communities as a sign of academic prestige.4,10 While Medical College Admission Test scores may not be directly evaluated by fellowship/TS residency programs, a higher score may increase one’s chances of acceptance to a US allopathic medical school, which in turn appears to be taken into consideration by program directors. Nevertheless, more than 1 in 4 matriculants (27.7%) were educated at an osteopathic or international medical school. Therefore, medical education prerequisites are not stringent, and successful candidates come from a variety of academic backgrounds. AOA membership was also found to be associated with matriculation; however, only a minority of TS residency applicants indicated AOA membership. This finding is consistent with that of a previous study Examining AOA membership and the impact on matriculation to fellowship.15

GS residency affiliation with a TS residency or an NCI-CCC was also associated with increased likelihood of matriculation. While we could not ascertain whether candidates matched into their GS residency-affiliated program, such affiliations likely contribute by fostering relationships between residents and experts in the field. Residents are more likely to be mentored by TS faculty or gain exposure to patients with complex cardiac pathologies or thoracic malignancies earlier in their training. Such affiliations also likely increase opportunities to pursue related research and obtain letters of recommendation from academic leaders in the field.

Not surprisingly, academic productivity is significantly associated with successful matriculation. Our study revealed that matriculants to TS residency exhibited far greater academic productivity than most GS graduates.16 This finding suggests that successful applicants to TS residencies are among those with the strongest academic profiles. Awareness of the competitive nature combined with the expectation of academic productivity from TS residency programs likely contributes to publication profiles noted in our analysis.

Volume and quality of publications were both associated with matriculation. Matriculants tended to achieve publication in high IF journals at a significantly higher rate than nonmatriculants. Although imperfect, we used the IF of the publishing journal as a surrogate for research quality. Attaining publication in a “high” IF journal (IF 10) is uncommon, strenuous, and time consuming, and few graduates of GS residency succeed in this endeavor.16 This is well illustrated in our applicant pool, where only 19.0% of the matriculant population achieved at least 1 publication in a journal with an IF of 10 or higher. Using the 2017 Clarivate Analytics Impact Factor analysis, we found that no clinical journal in the field of surgery had an IF exceeding 10. Publication in IF tier 3 (IF >10) was therefore reserved to applicants who had published in basic science or broader highly respected clinical journals.

Our report represents an examination of ERAS applications submitted to independent TS residency pro-grams and describes qualities that program directors likely examine when selecting candidates for interviews. However, this study is not without limitations. We would like to reiterate that our analysis does not represent a comprehensive evaluation and does not include important subjective measures. Personal connections, interview performance, and quality of letters of recommendation are just a few of these unquantifiable factors. In addition, to protect applicant privacy, the AAMC does not provide applicant characteristics, such as American Board of Surgery In-Training Examination scores, rank list, and program match data, or whether an applicant took time off for dedicated research.

Given our inability to analyze data before deidentification and aggregation by AAMC, we also could not examine raw individual data such as the specific TS residency program where the applicant matched, the length of training of that program, whether the applicant opted for a thoracic or cardiac training track, or whether the applicants were first authors on the publications reported in their applications. In addition, we did not examine the applications of those who applied to integrated (I6) TS residency programs and therefore cannot comment on the qualities of those who apply to such programs.

Finally, although applicants sign a legal statement attesting to the truthfulness of their application, data are often self-reported and carry the risk of misrepresentation. Our study should therefore not serve as a prescription but rather a guide to successful matriculation.

This study provides new and valuable insight into the attributes of those who successfully matriculate to TS residency. Applicants’ medical school, AOA status, residency affiliations, and individual research accomplishments were associated with successful matriculation and highlight the potential criteria considered by program directors. Our findings describe objective data intended to inform and help guide future TS residency applicants.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr Marie Caulfield and Dr Brianna Gunter for their invaluable work at the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), for their expert data collection and analysis, and for their extremely helpful collaboration with the National Cancer Institute Surgical Oncology Research Fellowship.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AAMC

Association of American Medical Colleges

- AOA

American Osteopathic Association

- CI

confidence interval

- ERAS

Electronic Residency Application System

- FREIDA

Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database

- GS

general surgery

- IF

impact factor

- IQR

interquartile range

- NCI-CCC

National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center

- TS

thoracic surgery

- US

United States

REFERENCES

- 1.Ellis MC, Dhungel B, Weerasinghe R, et al. Trends in research time, fellowship training, and practice patterns among general surgery graduates. J Surg Educ. 2011;68:309–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borman KR, Vick LR, Biester TW, et al. Changing demographics of residents choosing fellowships: longterm data from the American Board of Surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:782–788 [discussion: 788–789]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedell ML, VanderMeer TJ, Cheatham ML, et al. Perceptions of graduating general surgery chief residents: are they confident in their training? J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:695–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rinard JR, Mahabir RC. Successfully matching into surgical specialties: an analysis of national resident matching program data. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2:316–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pousatis SM, Marshall MB. Trends in applications for thoracic fellowship in comparison with other subspecialties. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:624–632 [discussion: 632–633]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Napolitano LM, Savarise M, Paramo JC, et al. Are general surgery residents ready to practice? A survey of the American College of Surgeons Board of Governors and Young Fellows Association. J Am Coll Surg.2014;218:1063–1072.e31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman JJ, Esposito TJ, Rozycki GS, et al. Early subspecialization and perceived competence in surgical training: are residents ready? J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:764–771 [discussion: 771–773]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bohl M, Reddy RM. Spouses of thoracic surgery applicants: changing demographics and motivations in a new generation. J Surg Educ. 2013;70: 640–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The National Residency Matching Program (NRMP) Results and Data for Specialties Match, 2018. Available at: https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Main-Match-Result-and-Data-2018.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2020.

- 10.Wach MM, Ruff SM, Ayabe RI, et al. An examination of applicants and factors associated with matriculation to complex general surgical oncology fellowship training programs. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:3436–3442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta S, McDonald JD, Wach MM, et al. Qualities and characteristics of applicants associated with successful matriculation to pediatric surgery fellowship training. J Pediatr Surg. 2020;55:2075–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraser JD, Aguayo P, St Peter S, et al. Analysis of the pediatric surgery match: factors predicting outcome. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011;27:1239–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker EH, Dowden JE, Cochran AR, et al. Qualities and characteristics of successfully matched North American HPB surgery fellowship candidates. HPB (Oxford). 2016;18:479–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kulaylat AN, Kenning EM, Chesnut CH 3rd, et al. The profile of successful applicants for endocrine surgery fellowships: results of a national survey. Am J Surg. 2014;208:685–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stain SC, Hiatt JR, Ata A, et al. Characteristics of highly ranked applicants to general surgery residency programs. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:413417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merani S, Switzer N, Kayssi A, et al. Research productivity of residents and surgeons with formal research training. J Surg Educ. 2014;71:865–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]