Abstract

Comparative genomics has shown that ray-finned fish (Actinopterygii) contain more copies of many genes than other vertebrates. A large number of these additional genes appear to have been produced during a genome duplication event that occurred early during the evolution of Actinopterygii (i.e. before the teleost radiation). In addition to this ancient genome duplication event, many lineages within Actinopterygii have experienced more recent genome duplications. Here we introduce a curated database named Wanda that lists groups of orthologous genes with one copy from man, mouse and chicken, one or two from tetraploid Xenopus and two or more ancient copies (i.e. paralogs) from ray-finned fish. The database also contains the sequence alignments and phylogenetic trees that were necessary for determining the correct orthologous and paralogous relationships among genes. Where available, map positions and functional data are also reported. The Wanda database should be of particular use to evolutionary and developmental biologists who are interested in the evolutionary and functional divergence of genes after duplication. Wanda is available at http://www.evolutionsbiologie.uni-konstanz.de/Wanda/.

INTRODUCTION

Ray-finned fish (Actinopterygii) have more copies of many genes than species in their sister group Sarcopterygii (the lobed-finned fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals). Zebrafish (Danio rerio) and medaka (Oryzias latipes), for example, possess seven unlinked Hox gene clusters, almost twice as many as tetrapods such as mouse and human, which have four (1,2). Amores et al. (1) proposed that the extra Hox genes in zebrafish were produced during a genome duplication event before the evolution and radiation of Teleostei (3,4). In fact, several authors have speculated that the ‘extra’ genes produced during the proposed fish-specific genome duplication event somehow facilitated speciation in Actinopterygii (3,5–7). More recently, evidence for Hox cluster duplication has also been uncovered in the cichlid Oreochromis niloticus (8) and the pufferfish Fugu rubripes (9,10). Support for a large-scale gene duplication event in fish is not limited to the Hox clusters. Gene mapping and phylogenetic studies have identified a large number of other sarcopterygian genes with two zebrafish orthologs (11–15). The observations that many of these zebrafish ‘paralogs’ (16,17) are sister sequences in phylogenetic trees support the hypothesis that they were formed after ray-finned fish and tetrapods diverged from one another. The observations that different paralogous pairs were formed at approximately the same time (15), that they are found throughout the genome and that they show synteny with other duplicated genes (11,12,14), support the hypothesis that they were formed during a complete genome duplication event.

However, gene duplication appears to be a remarkably frequent event (18) and tetraploidy has occurred independently in numerous lineages within Actinopterygii (19–23). It is therefore possible that independent gene and genome duplication events have led to the appearance of an ancient genome duplication event (24).

Redundant genes produced by gene or genome duplication events are likely to be silenced and eventually lost (18,25,26). Nevertheless, numerous models have been put forward to explain the retention of duplicated genes and their divergence in sequence and function. If a gene is not turned into a pseudogene, alternatively, by chance, a series of non-deleterious mutations might turn the duplicate into a gene with a new function (27). Although Ohno’s model was adopted widely as an explanation for the evolution of functionally novel genes, it was criticized and numerous other models were put forward to explain both the retention and functional divergence of genes (28–30). In the fish species for which gene expression has been best studied, namely the zebrafish, retained duplicates often appear to have subdivided the roles of their single-gene ancestors (31–34). If duplicated genes lose different regulatory subfunctions, each affecting different spatial and/or temporal expression patterns, then they must complement each other by jointly retaining the full set of subfunctions present in the ancestral gene. Therefore, degenerative mutations facilitate the retention of duplicate functional genes, in which both duplicates now perform different but necessary subfunctions. Thus, the likelihood of gene retention/survival following duplication seems to increase when genes subdivide the roles of their ancestors.

Recently, a model called ‘divergent resolution’ has been proposed (18,35) which suggests that loss or silencing of duplicated genes might be more important to the evolution of species diversity than the evolution of new functions in duplicated genes. Divergent resolution occurs when different copies of a duplicated gene are lost in geographically separated populations and can genetically isolate these populations, should they become reunited (7). Divergent resolution of the 1000 to tens of thousands of genes and their regulatory regions produced by large-scale gene duplications or a complete genome duplication event provides another alternative link between genome duplication and speciation in teleosts.

CONTENTS OF THE DATABASE AND AVAILABILITY

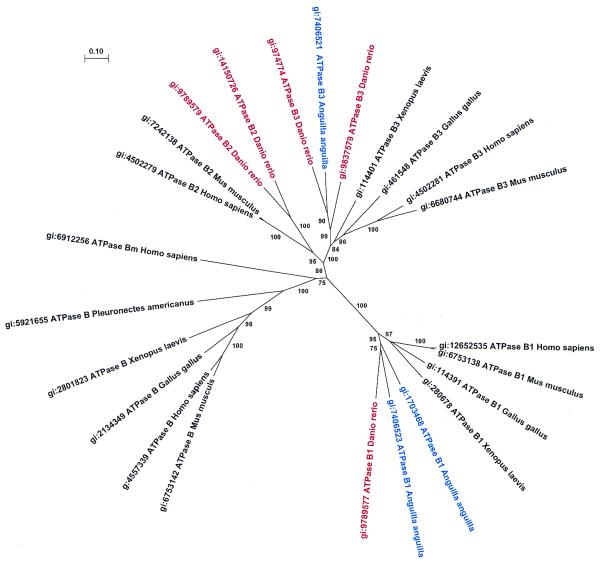

At the moment, the Wanda database lists more than 60 genes that occur once in human and mouse and twice in fish. In the near future, we expect the number of fish homologs to increase rapidly, because of the genome sequencing projects of Fugu rubripes (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/), its fresh water relative Tetraodon nigroides (http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/) and zebrafish, for which the complete genome is planned to be sequenced in 2003. The majority of duplicates compiled so far are from zebrafish; however, the database also includes genes from other fish species, even when only one copy is known. Many of these genes are most closely related to one of the two zebrafish duplicates (Fig. 1), indicating that they are probably one of a pair of genes (i.e. semi-orthologs with respect to the tetrapod homolog) (36).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree showing the orthologous and paralogous relationships among ATPase B genes. Two copies of ATPase B3 and ATPase B2 exist for D.rerio (zebrafish) and two copies of ATPase B1 for Anguilla anguilla (European eel). The fact that the single ATPase B3 of Anguilla is clustered, with high confidence, with one of the zebrafish paralogs, would imply that the duplication of both zebrafish ATPase B3 genes occurred before the radiation of eels and zebrafish. The same conclusion can be drawn on the basis of the clustering of the zebrafish ATPase B1 gene with one of the two Anguilla ATPase B1 genes. These observations suggest that probably another ATPase B3 gene is present in eels and that another ATPase B1 gene occurs in zebrafish.

International databases, such as EMBL (37) and GenBank (38), are checked daily for the submission of new fish genes by using the Current Sequence Awareness tool, developed by the Belgian EMBNet node (http://ben.vub.ac.be/). When new fish genes have been submitted, similarity searches (for instance, BLAST) are performed to find sarcopterygian and actinopterygian homologs. Phylogenetic trees will be constructed to determine the relationship between the new gene(s) and known fish duplicates.

The Wanda database allows users to determine quickly whether a known fish gene is one of a set of ‘semi-orthologs’. Fish genes very often have names that provide no hint to the fact that they are one of many orthologs of a given tetrapod gene. Nevertheless, this information can be very important. For example, differences in gene expression patterns between tetrapods (such as mouse) and fish (such as zebrafish) can sometimes be explained by paralogs in fish that subdivide the roles of their tetrapod orthologs. Furthermore, the possibility of performing local BLAST (39) searches will be useful for correctly naming new genes that have been isolated from fishes. For example, a new gene from a certain species may be most similar to one of two paralogous genes in another species of fish. Wanda then allows users to determine whether the newly sequenced gene is either the ‘a’ or the ‘b’ copy, which should designate paralogous genes more consistently in the future.

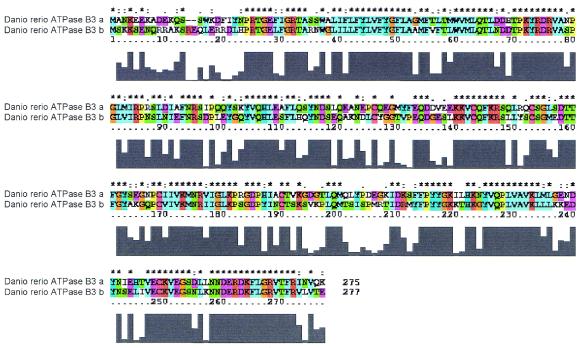

In addition to compiling duplicated genes in fishes and their vertebrate orthologs, Wanda will also provide: (i) references to literature and other databases reporting expression data for fish duplicates; (ii) nucleotide and amino acid sequence alignments and variability maps (Fig. 2) of fish paralogs; (iii) nucleotide and amino acid sequence alignments of fish duplicates and their sarcopterygian orthologs; (iv) phylogenetic trees (Fig. 1) showing the relative rates of evolution and the orthologous and paralogous relationships between duplicated fish genes and their sarcopterygian orthologs; (v) tables listing the results of studies that look for purifying or positive selection after duplication events; and (vi) cross-references to the international nucleotide sequence databases, such as EMBL and GenBank and to other fish-specific databases, such as ZFIN (40) (http://zfin.org/ZFIN/).

Figure 2.

Sequence alignment and variability map of the ATPase B3 paralogs of zebrafish. A line above the alignment is used to mark strongly conserved positions. An asterisk indicates positions with a single, conserved residue, and a colon and a full point, one of the ‘strong’ (STA, NEQK, NHQK, NDEQ, QHRK, MILV, MILF, HY and FYW) and ‘weaker’ (CSA, ATV, SAG, STNK, STPA, SGND, SNDEQK, NDEQHK, NEQHRK, FVLIM and HFY) groups, respectively (41). Variability maps for the other zebrafish paralogs will be available as well.

A well-annotated database that compiles paralogous gene sequences in fish is a valuable source of information for biologists and geneticists who are interested in the evolutionary and developmental consequences of duplication events, as well as for biologists concerned with the evolutionary consequences of large-scale gene duplications. Overall, the Wanda database aims to compare duplicated genes with their non-duplicated homologs, in terms of structure and function and evolutionary divergence. As this database grows, it will also provide the data necessary to test the ancient fish-specific genome duplication hypothesis. Combining phylogenetic trees with map data will help testing the hypothesis that ‘divergent resolution’ has played a role in speciation within the ray-finned fish.

The Wanda database is available via the World Wide Web at http://www.evolutionsbiologie.uni-konstanz.de/Wanda/. Questions regarding the Wanda database should be addressed to: yvdp@gengenp.rug.ac.be, john.taylor@uni-konstanz.de or axel.meyer@uni-konstanz.de.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the German Science Foundation (DFG PE 842/2-1). J.S.T. is indebted to the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada for a Postdoctoral fellowship. Y.V.d.P. is a Postdoctoral Fellow of the Fund for Scientific Research (Flanders).

REFERENCES

- 1.Amores A., Force,A., Yan,Y.-L., Joly,L., Amemiya,C., Fritz,A., Ho,R.K., Langeland,J., Prince,V., Wang,Y.-L. et al. (1998) Zebrafish hox clusters and vertebrate genome evolution. Science, 282, 1711–1714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naruse K., Fukamachi,S., Mitani,H., Kondo,M., Matsuoka,T., Kondo,S., Hanamura,N., Morita,Y., Hasegawa,K., Nishigaki,R. et al. (2000) A detailed linkage map of medaka, Oryzias latipes: comparative genomics and genome evolution. Genetics, 154, 1773–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wittbrodt J., Meyer,A. and Schartl,M. (1998) More genes in fish? Bioessays, 20, 511–512. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer A. and Schartl,M. (1999) Gene and genome duplications in vertebrates: the one-to-four (-to-eight in fish) rule and the evolution of novel gene functions. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 11, 699–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aparicio S. (2000) Vertebrate evolution: recent perspectives from fish. Trends Genet., 16, 54–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kappen C. (2000) Analysis of a complete homeobox gene repertoire: implications for the evolution of diversity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 4481–4486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor J., Van de Peer,Y. and Meyer,A. (2001) Genome duplication, divergent resolution and speciation. Trends Genet., 17, 299–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Málaga-Trillo E. and Meyer,A. (2001) Genome duplications and accelerated evolution of Hox genes and cluster architecture in teleost fishes. Am. Zool., 41, 676–686. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aparicio S., Hawker,K., Cottage,A., Mikawa,Y., Zuo,L., Venkatesh,B., Chen,E., Krumlauf,R. and Brenner,S. (1997) Organization of the Fugu rubripes Hox clusters: evidence for continuing evolution of vertebrate Hox complexes. Nature Genet., 16, 79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amores A., Amemiya,C.T. and Postlethwait,J. (2000) Genome duplication and evolution of Hox clusters in teleosts. Abstract from the Zebrafish Development and Genetics Meeting. Cold Spring Harbor. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gates M.A., Kim,L., Cardozo,T., Sirotkin,H.I., Dougan,S.T., Lashkari,D., Abagyan,R., Schier,A.F. and Talbot,W.S. (1999) A genetic linkage map for zebrafish: comparative analysis and localization of genes and expressed sequences. Genome Res., 9, 334–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Postlethwait J.H., Woods,I.G., Ngo-Hazelett,P., Yan,Y.-L., Kelly,P.D., Chu,F., Huang,H., Hill-Force,A. and Talbot,W.S. (2000) Zebrafish comparative genomics and the origins of vertebrate chromosomes. Genome Res., 10, 1890–1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson-Rechavi M., Marchand,O., Escriva,H., Bardet,P.L., Zelus,D., Hughes,S. and Laudet,V. (2001) Euteleost fish genomes are characterized by expansion of gene families. Genome Res., 11, 781–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woods I.G., Kelly,P.D., Chu,F., Ngo-Hazelett,P., Yan,Y.-L., Huang,H., Postlethwait,J.H. qand Talbot,W.S. (2000) A comparative map of the zebrafish genome. Genome Res., 10, 1903–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor J.S., Van de Peer,Y., Braasch,I. and Meyer,A. (2001) Comparative genomics provides evidence for an ancient genome duplication event in fish. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci., 356, 1661–1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitch W.M. (2000) Homology: a personal view on some of the problems. Trends Genet., 16, 227–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mindell D.P. and Meyer,A. (2001) Homology evolving. Trends Ecol. Evol., 16, 434–440. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynch M. and Conery,J.S. (2000) The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science, 290, 1151–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uyeno T. and Smith,G.R. (1972) Tetraploid origin of the karyotype of catostomid fishes. Science, 175, 644–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dingerkus G. and Howell,W.M. (1976) Karyotypic analysis and evidence of tetraploidy in the North American paddlefish, Polyodon spathula. Science, 194, 842–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allendorf F.W. and Utter,F.M. (1976) Gene duplication in the family Salmonidae. III. Linkage between two duplicated loci coding for aspartate aminotransferase in the cutthroat trout (Salmo clarki). Hereditas, 82, 19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferris S.D. and Whitt,G.S. (1977) Loss of duplicate gene expression after polyploidisation. Nature, 265, 258–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson-Rechavi M., Marchand,O., Escriva,H. and Laudet,V. (2001) An ancestral whole-genome duplication may not have been responsible for the abundance of duplicated fish genes. Curr. Biol., 11, R458–R459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bailey G.S., Poulter,R.T. and Stockwell,P.A. (1978) Gene duplication in tetraploid fish: model for gene silencing at unlinked duplicated loci. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 75, 5575–5579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li W.-H. (1980) Rate of gene silencing at duplicate loci: a theoretical study and interpretation of data from tetraploid fishes. Genetics, 95, 237–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohno S. (1970) Evolution by Gene Duplication. Springer Verlag, New York, NY.

- 28.Nowak M.A., Boerlijst,M.C., Cooke,J. and Maynard Smith,J. (1997) Evolution of genetic redundancy. Nature, 388, 167–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gibson T.J. and Spring,J. (1998) Genetic redundancy in vertebrates: polyploidy and persistence of genes encoding multidomain proteins. Trends Genet., 14, 46–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Force A., Lynch,M., Pickett,F.B., Amores,A., Yan,Y.-l. and Postlethwait,J. (1999) Preservation of duplicate genes by complementary, degenerative mutations. Genetics, 151, 1531–1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ekker M., Akimenko,M.A., Allende,M.L., Smith,R., Drouin,G., Langille,R.M., Weinberg,E.S. and Westerfield,M. (1997) Relationships among msx gene structure and function in zebrafish and other vertebrates. Mol. Biol. Evol., 14, 1008–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martínez-Barberá J.P., Toresson,H., Da Rocha,S. and Krauss,S. (1997) Cloning and expression of three members of the zebrafish Bmp family: Bmp2a, Bmp2b and Bmp4. Gene, 198, 53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laforest L., Brown,C.W., Poleo,G., Geraudie,J., Tada,M., Ekker,M. and Akimenko,M.-A. (1998) Involvement of the Sonic Hedgehog, patched 1 and bmp2 genes in patterning of the zebrafish dermal fin rays. Development, 125, 4175–4184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van de Peer Y., Taylor,J.S., Braasch,I. and Meyer,A. (2001) The ghost of selection past: rates of evolution and functional divergence in anciently duplicated genes. J. Mol. Evol., 53, 434–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lynch M. and Force,A. (2000) The probability of duplicate gene preservation by subfunctionalization. Genetics, 154, 459–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharman A.C. (1999) Some new terms for duplicated genes. Cell Dev. Biol., 10, 561–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stoesser G., Baker,W., van den Broek,A., Camon,E., Garcia-Pastor,M., Kanz,C., Kulikova,T., Lombard,V., Lopez,R., Parkinson,H. et al. (2001) The EMBL nucleotide sequence database. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 17–21. Updated article in this issue: Nucleic Acids Res. (2002), 30, 21–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wheeler D.L., Church,D.M., Lash,A.E., Leipe,D.D., Madden,T.L., Pontius,J.U., Schuler,G.D., Schriml,L.M., Tatusova,T.A., Wagner,L. and Rapp,B.A. (2001) Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 11–16. Updated article in this issue: Nucleic Acids Res. (2002), 30, 13–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Altschul S.F., Gish,W., Miller,W., Myers,E.W. and Lipman,D.J. (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol., 215, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sprague J., Doerry,E., Douglas,S. and Westerfield,M. (2001) The Zebrafish Information Network (ZFIN): a resource for genetic, genomic and developmental research. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 87–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson J.D., Gibson,T.J., Plewniak,F., Jeanmougin,F. and Higgins,D.G. (1997) The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 4876–4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]