Abstract

This work explores a method for classifying peaks appearing within a data-intensive time-series. We summarize a case study from a clinical trial aimed at reducing secondhand smoke exposure via the installation of air particle monitors in households. Proper orthogonal decomposition (POD) in conjunction with a k-means clustering algorithm assigns each data peak to one of two clusters. Aversive feedback from the monitors increased the proportion of short-duration, attenuated peaks from 38.8% to 96.6%. For each cluster, a distribution of parameters from a physics-based model of airborne particles is estimated. Peaks generated from these distributions are correctly identified by POD/clustering with >60% accuracy.

Keywords: proper orthogonal decomposition, k-means, Dylos monitor, real-time measurement, secondhand smoke

1. Introduction

Real-time and mobile technology for health delivery is becoming increasingly widespread and has the capacity to fundamentally alter the nature of the interaction between patients and health service providers. This technology offers the potential for personalized treatments that can be modified in real-time in response to several variables, namely participants’ varying behaviors, environmental contexts, and unique past history [1]. Capitalizing on this opportunity is predicated on the accurate identification of these variables in a variety of dynamic contexts. Our ability to achieve this is limited by the availability of suitable technology to gauge behavior. In an effort to move towards this eventual future, this study explored the clustering of behavioral characteristics from intensive time-series data generated via a secondhand smoke exposure (SHSe) real-time technology intervention.

Project Fresh Air (PFA) is an ongoing randomized intervention trial aimed at reducing SHSe in the homes of smokers via the installation of Dylos DC1700 air particle quality monitors. Each study household contains a child as well as an adult who engages in SHS-generating behavior, typically indoor cigarette smoking. As described in Ref. [2], the monitors are calibrated to detect particles with sizes ranging from 0.5 to 2.5 microns, which is consistent with SHS as well as non-tobacco aerosol sources such as cooking and incense. One monitor is installed in the main smoking room and another is placed in the child’s bedroom; measurements from only the main room monitor are included in the following discussion. Every ten seconds, the monitor collects a measurement of the air particle concentration, which is an average of the previous 10 measurements collected at one-second intervals. This data is transmitted to a small computer that, in turn, uploads the data to a website that is accessible to PFA staff in near real-time. The monitors are fit with devices that deliver aversive visual and auditory feedback (yellow/red lights and beeps) that are programmed to engage when air particle concentrations exceed 60 ; the aversiveness of the feedback increases [3] if the 120 threshold is breached. For each home, the duration of the trial is broken into two phases: 1.) Baseline (BL) – a washout period during which feedback is not activated, designed to allow for the abatement of participant reactivity to monitor installation and 2.) Treatment (TX) – the period during which the feedback is activated.

To reduce SHSe, the PFA intervention aims to modify particle-generating behavior, in particular tobacco smoking. The intervals of the particle time-series data with elevated concentrations, or peaks, serve as proxy measures of this behavior. As such, we seek to abstract behavioral features from peaks in the time-series data. Complicating this task is the lack of information about the identification and number of household occupants associated with a given peak. Additionally, the monitors only detect information about particle size and not chemical composition so confounding sources of smoke particles, such as burning food, are likely present. Ultimately, we aim to associate different peaks with distinct behaviors such as cigarette smoking, food burning, or air venting and to analyze the patterns of these behaviors over time. The approach outlined hereafter represents the establishment of the groundwork on which to accomplish this task.

In Section 2, proper orthogonal decomposition (POD), a blind signal separation (BSS) technique that can be used to identify underlying source signals that are functionally associated with peak characteristics, is described. Section 3 discusses the application of the methodology in Section 2 to a case study from PFA. A cluster analysis of POD coefficients that allows characteristically similar peaks to be classified together is set forth in Section 4 and the results of this analysis are summarized in Section 5. Section 6 describes the relationship between peak clusters and parameters from a physics-based model of airborne particulates, which enables a physical interpretation of the POD/clustering results. A discussion of findings ensues in Section 7.

2. Extension of Proper Orthogonal Decomposition to Peak Analysis

BSS is defined as the factoring of a mixed source into previously-unknown, independent components [4]. It has been implemented in a variety of contexts including the analysis of interstellar dust [5], neuroprocessing [6], and audio processing [7]. A popular BSS technique is proper orthogonal decomposition (POD) also known as Karhunen–Loève decomposition [8], principal components analysis [9], singular systems analysis [10], or singular value decomposition [11]. This procedure transforms a set of observations to a new coordinate system in which each dimension is linearly uncorrelated with the others. It is an attractive option to discriminate between peak characteristics since it provides an optimal basis to decompose signals and analytical bounds for the estimate of total “energy” captured by the decomposition [8]. For this study, POD is used to define a projection (decomposition) into a lower dimensional space where different types of peaks that represent similar physical scenarios that triggered elevated particle counts can be identified via clustering analysis.

Consider a sequence of observations represented by scalar functions u(x, ti), i = 1…M. Typically ti represents the ith temporal observation of state variable x. Without loss of generality, the time-average of the sequence, defined by

| (1) |

is assumed to be zero (if not, as it is in our case, simply subtract the time-average from all observations). The POD extracts time-independent orthonormal basis functions, ϕk(x), and time-dependent orthonormal amplitude coefficients, ak(ti), such that the reconstruction

| (2) |

is optimal in the sense that the average least squares truncation error of the POD reconstruction is minimized for any given number m ≤ M of basis functions over all possible sets of orthogonal functions. ⟨·⟩ denotes an average operation, usually over time; and the functions ϕk(x) are called empirical eigenfunctions, coherent structures, or POD modes.

The domains x and t are completely empirical so that there is flexibility to interpreting them according to the needs of the data. Often times, POD analysis is performed on a state variable x assessed at various times ti [12]. When extended to time-series data, the interpretation can change to i instances of a univariate time-series x, e.g., stock returns for multiple companies over a specified interval [13]. The procedure can also be performed on multivariate time-series [14]. Yet another interpretation is singular spectrum analysis, where a univariate time-series is embedded to create a multidimensional state variable x, that is observed at time steps ti [15]. In our case, we are interested in peak events, i.e., the intervals in the time-series with elevated particle measurements. We assign u(x, ti) to the indoor particle concentration measurements of the ith peak. Rather than representing a state variable assessed at some time ti, x is a subset of the data corresponding to the ith peak. Thus the collection of peaks can be summarized as the matrix U = [u(x, t1)|u(x, t2)|…|u(x, tM)] where the ith column corresponds to the data from the ith peak event, although the order of the peaks does not affect the analysis.

It can be shown that the eigenfunctions ϕk in Eq. 2 are the eigenvectors of the matrix product . A popular technique for finding these eigenvectors when the resolution of x is greater than the number of observations is the method of snapshots developed by Sirovich [16]. First the eigenvectors of , denoted as vk, are found. Then the ϕk’s are calculated by Φ = UV where Φ = [ϕ1|ϕ2|…ϕM] and V = [v1|v2|…vM]. Let ai represent the reconstruction coefficients associated with the ith peak. These can be calculated by A = UT Φ, where A is the M-by-M matrix [a1|a2|…aM]. Statistically speaking, the eigenvalues λk of represent the variance of the data set in the direction of the corresponding POD mode ϕk(x). In physical terms, if u represents a component of a velocity field, then λk measures the amount of kinetic energy captured by the respective POD mode, ϕk(x). In this sense, the energy measures the contribution of each mode to the overall dynamics. Thus, the total energy captured in the POD is defined as the sum of all eigenvalues: , and the relative energy captured by the kth mode is Ek = λk/E.

3. POD of Particle Concentration Time-Series

To demonstrate the application of POD to particle concentration data, we considered a single household from PFA, HM180. This home is a single-story, 1 bedroom, 1 bathroom detached house. The monitor was placed at a height of 8 feet in the living room of the home. The household was enrolled in the study for 95 days, with the first 31 days in the BL phase and the remainder in the TX phase. Approximately 750,000 measurements were collected from the monitor in the main smoking room. As will be discussed in detail in Section 5.2, HM180 was chosen based on its reporting of tobacco smoking events to PFA staff.

When recorded by the Dylos monitor, each particle concentration measurement is assigned an alarm status variable that controls the emission of visual and auditory feedback. We use this variable to define peak events. An event begins when the alarm status indicates an initial breach of 60 ; this triggers a yellow light and the first sound. The peak event does not end until the alarm status indicates that the concentration has fallen below 40 which corresponds with the cessation of all visual and auditory feedback. This definition of a peak ensures that each peak event mirrors the presentation of monitor feedback, which is hypothesized to affect behavior. While there is a risk that the multiple peaks could be concatenated into one event, particularly for events with long tails, the eigenmodes calculated below do not indicate that this is a common occurrence.

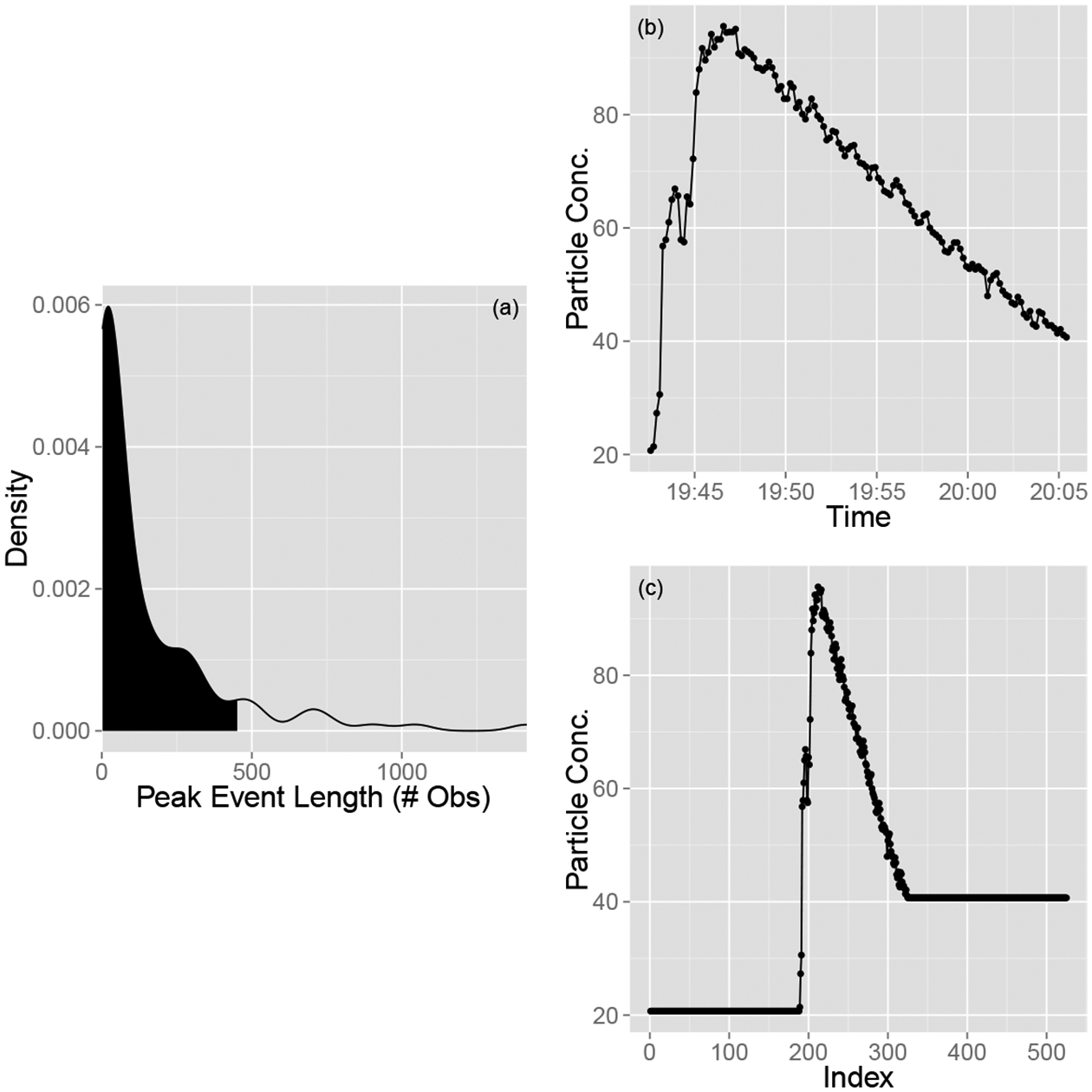

Defining peaks this way results in considerable variability in the number of observations comprising each peak event. The POD process outlined above, though, requires each peak to have the same number of measurements so they can populate the columns of the matrix U. In meeting this requirement two competing effects must be taken into account: (a) if too few measurements are used, then much of the information about the longer duration peaks is lost; but (b) if too many measurements are used, much of the information about the shorter-duration peaks is diluted. We chose the 90th percentile of the distribution of the number of measurements in a peak as a likely good balance between these considerations. This percentile is consistent with the right-skew distribution of the peak durations present in most homes. Figure 1(a) shows the distribution of peak durations; the 90th percentile is 452 observations. The one minute (six observations) preceding each event is concatenated to the data to capture information about the leadup to threshold exceedance. In order to focus on peak shape, we aligned the center of mass of each peak while maintaining a uniform number of observations via the following process. Let lj and νj represent the number of observations and the center of mass, respectively, of the jth peak event. Generally speaking, lj ≠ lk and νj ≠ νk for the jth and kth peaks. Let ν* represent the maximum value of all νj’s and Ui,j represent the ith observation of the jth peak. We aligned all of the center of masses with ν* by concatenating ν* − νj “dummy” observations to U1,j, each of which are set equal to U1,j. To maintain uniformity in the number of observations, let r* be the maximum of lj − νj, the distance between a center of mass and the last measurement. Now concatenate r* − νj dummy observations to UN,j, each set equal to UN,j. Each peak event now has observations and their centers of mass, calculated without including the dummy observations, align. This process, which we call padding, is illustrated in Fig. 1 for the 15th peak (in temporal order), where ν* = 250, r* = 275, and .

Figure 1:

Panel (a) Distribution of the length of peak events. The shaded region represents the 90th percentile. Panels (b)-(c) The padding procedure for Peak 15 (in temporal order). The peak as it appears in the time-series is shown in Panel (b); Length(l15)=138 and center of mass (ν15) = 63. Panel (c) illustrates the peak after 187 and 200 dummy variables have been added to the beginning and end of the peak, respectively. The event, along with all others, now has observations, enough to account for centering every peak event in the full data series about its center of mass. Note that the average has not been subtracted out.

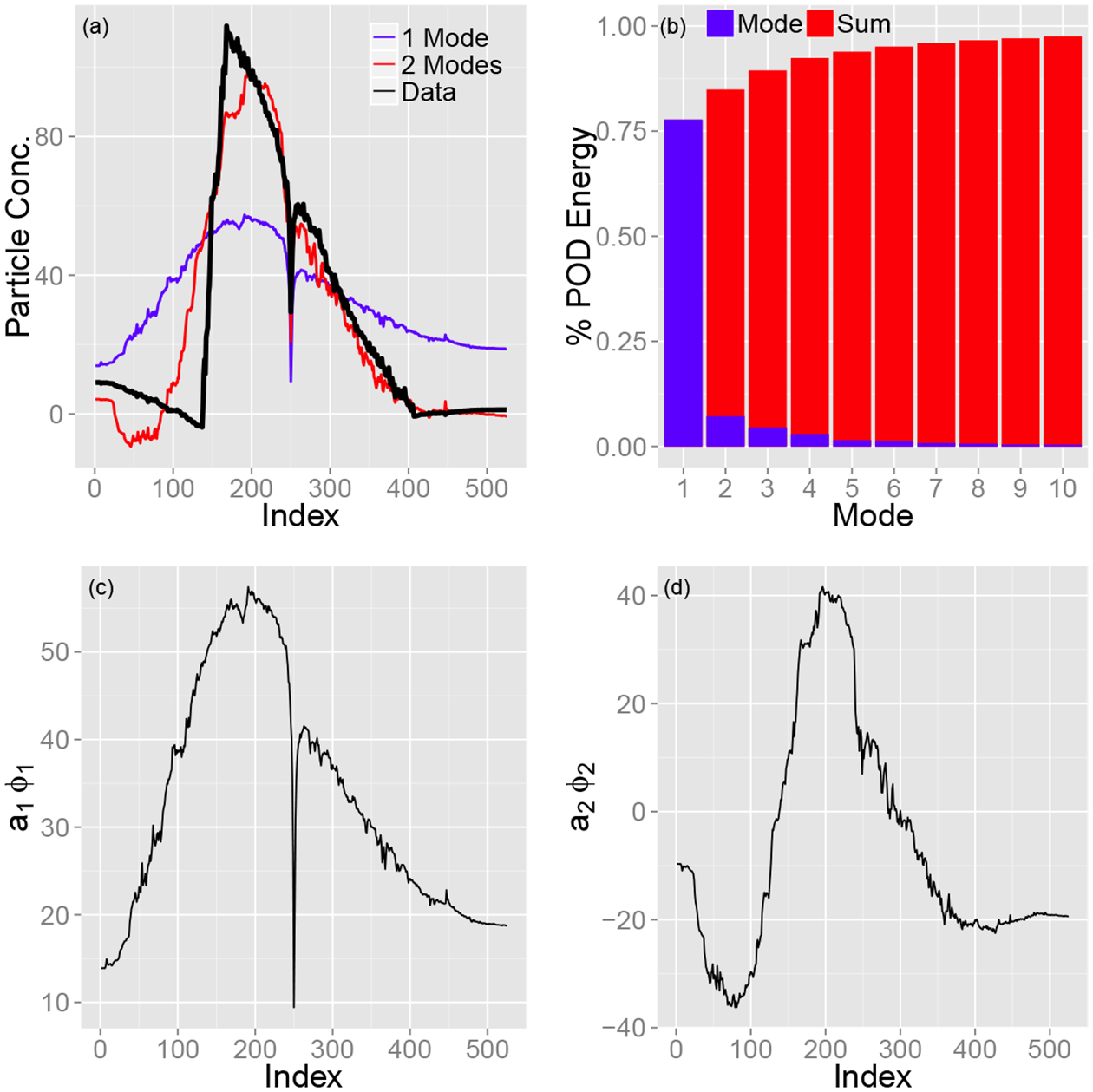

Following the above procedure, the data matrix U is obtained and the POD analysis can be performed. We subtract out the average over all observations, that is, the row averages of U, and find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of UUT. The total “energy” captured by the POD reveals that the contribution for each mode decreases rapidly as seen in panel (b) of Fig. 2. Specifically, using one and two modes corresponds, respectively, to capturing 79% and 7% of the “energy” of the original peaks, or 86% cumulatively. Therefore, each peak can be approximated by a linear combination of these two modes. Figure 2 depicts the POD for a sample peak event; as can be observed in panel (a) the two-mode reconstruction is able to capture the shape of the peak quite accurately. The analytic results outlined hereafter were also performed using three and four eigenmodes as opposed to two. The results were not affected but the computational cost was significantly increased.

Figure 2:

Proper orthogonal decomposition (POD) results. (a) Reconstruction of the 24th peak (in temporal order). The thick black line corresponds to the original peak while the blue and red lines represent POD reconstructions using, respectively, 1 and 2 POD modes. (b) Individual and cumulative average variance accounted for by the first ten eigenmodes, ϕi. Note ϕ1 ≈ 79% and ϕ1 + ϕ2 ≈ 86% of the total variance. (c)-(d) The first two eigenmodes ϕ1 and ϕ2, respectively.

4. Cluster Analysis

As outlined above, the projection of each peak onto the two-dimensional subspace formed by the first two POD eigenmodes can be used to reduce the dimensionality of each peak from to 2. By performing a cluster analysis on the coefficients of this projection, groups of peaks with similar coefficients, and therefore similar characteristics, can be identified. The k-means algorithm is very popular for cluster analysis due to its simplicity and local-minimum convergence properties [17]. Given a set of observations (x1, x2, …, xM), the k-means algorithm partitions the data points into k clusters S = {S1, S2, …, Sk} while attempting to reduce the total sum of square error over all clusters. That is, we seek

| (3) |

where μi is the center of mass, or centroid, of the points in Si. The algorithm proceeds as follows:

Randomly select k values from (x1, x2, …, xM), which serve as the initial centroids.

Assign each data point to the centroid it is closest to, as measured by sum of square error. In other words, Si = {xp : ∥xp − μi∥2 ≤ ∥xp − μl∥2 ∀ l with 1 ≤ l ≤ k}. Each point can be assigned to only one cluster so in the rare event that there is a tie, it is resolved at random.

Recalculate .

Repeat steps two and three until no xj’s change clusters.

The k-means algorithm is guaranteed to converge locally, but not globally. To ensure that the optimal clustering is identified, for each k-means application we perform the above-described procedure 100 times and choose the clustering associated with the lowest sum of square errors. Generally speaking, a smaller k corresponds to less variability in the local minima that are identified.

The standard k-means algorithm gives equal weight to every dimension of the xj’s. Recall, though, that for this study the dimensions for each observation correspond to the coefficients for the first two eigenfunctions, ϕ1 and ϕ2, in the reconstruction of the peaks. These modes do not have equal weight in reproducing a peak and the proportion of the total information provided by ϕi is given by . Consider Λ ≡ {λ1, λ2,} and . When calculating the distance between observations and centroids (xj − μi for i = 1, …, k and j = 1, …, M), the difference between the pth dimension of xj and μi is multiplied by where is the pth element of . This procedure ensures that differences corresponding to ϕ1 are more heavily-weighted, than differences in ϕ2. These weightings are in proportion to total energy captured by a mode. The difference between the cluster assignment from the standard and weighted k-means algorithms diminishes as k decreases. As will be described below, k = 2 is appropriate and in this case, for this home, the cluster assignments from the standard and weighted k-means algorithm are identical.

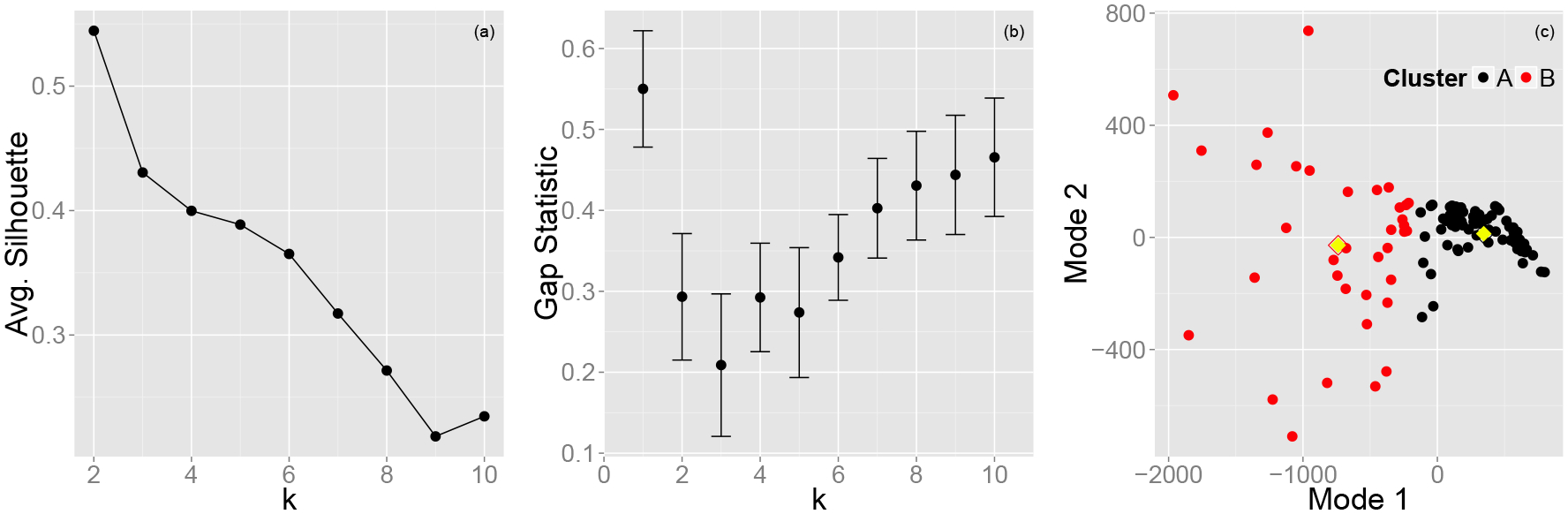

A critical component of the k-means algorithm is the selection of k, the number of clusters with which to partition the data. Two metrics, silhouettes and the gap statistic, were used to identify the optimal k. The method of silhouettes is a graphical technique used to gauge the distinctness of clusters [18]. Let α(i) be the distance from xi, the ith peak, to μi and let β(i) be the distance from xi to the next closest centroid. The silhouette represents the relative distance of a peak to its two nearest clusters. In the ideal case, a peak lies directly on its centroid so α(i) = 0 and s(i) = 1. Therefore, to select the optimal number of clusters, we calculate , the average silhouette over all peaks, for various values of k and choose the one closest to 1. Figure 3(a) illustrates calculated for k = 2, …, 10 and we see that the highest value corresponds to k = 2.

Figure 3:

Weighted k-means clustering. (a) Average silhouette. (b) Gap statistic. (c) Each point represents a peak. Its two coordinates are the coefficients corresponding to the first two eigenfunctions ϕ1 and ϕ2. k = 2 was used and each peak is classified as Type A (black) or Type B (red). The filled yellow diamonds represent the centroid of each cluster.

Because two clusters are used to determine the value of a silhouette, this method cannot be used to evaluate the k = 1 case, which is important if one wishes to determine whether the data as a whole data has any clustered structure. The gap statistic does not suffer from this weakness. It compares the clustering of the data versus the clustering of a reference distribution explicitly constructed without a clustered configuration [19]. For a set of clustered observations (x1, x2, …, xM), let denote the total sum of square error over all observations and their associated centroid. An unclustered reference distribution of M observations is then generated from a uniform distribution over the range of each dimension of the data. We partition the data into k clusters and calculate E*(k), the total sum of square errors for this distribution. B bootstrapped reference distributions are created and the above process is repeated. We can then calculate the gap statistic , which represents the difference between the errors for the data and the unclustered reference distribution for k clusters. Larger values of G(k) indicate a greater level of clustered structure in the data. The standard deviation of the errors associated with the B reference distributions can also be calculated, which allows the standard deviation of the gap statistic, σG(k), to be determined. A criterion for choosing k + 1 versus k clusters is that G(k + 1) > G(k) + σG(k).

The gap statistic assumes well-separated, uniform clusters so the presence of subclusters within larger clusters in the data can lead to non-monotonic behavior. Therefore, it is important to examine the entire gap curve rather than simply identifying the maximum [19]. Figure 3(b) shows the gap statistic which illustrates two distinct clusters. The first, from k = 1 through 3, has its maximum at k = 1 and then decreases, indicating uniformity throughout this cluster. The second cluster (k = 4 through 10) has an increasing trend in G(k), which is indicative of subclustering. Overall though, this analysis corresponds with the results of the method of silhouettes, namely that k = 2 is ideal when applying the weighted k-means algorithm to the data.

5. Results of POD and Cluster Analysis

5.1. Peak Classification

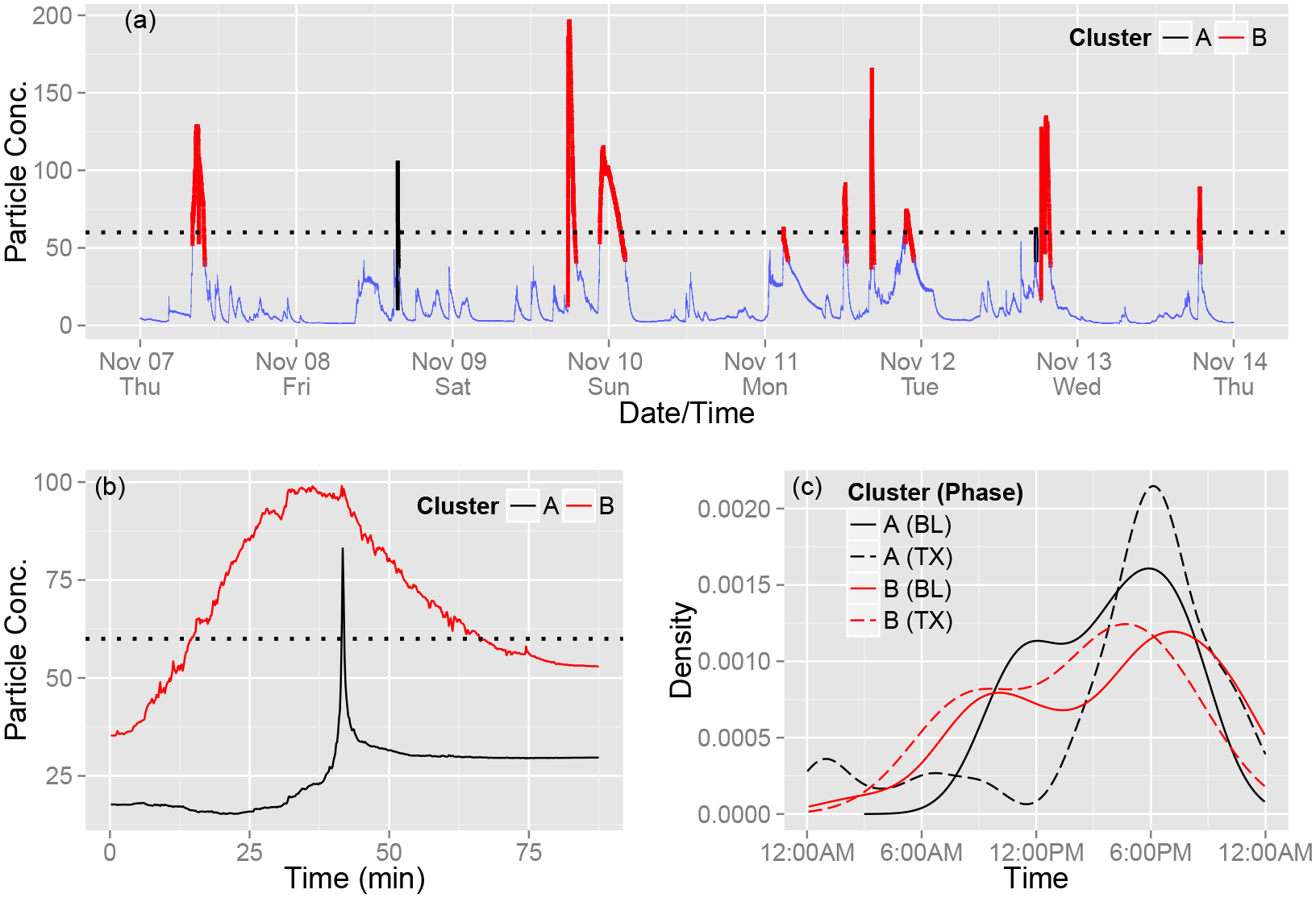

Based on the results from the previous two sections, a k-means cluster analysis with k = 2 was performed on the projection coefficients of the first two eigenmodes extracted from the POD procedure. We give these clusters the intentionally nondescript names Type A and Type B to highlight the fact that they were identified solely through their structure with no immediately discernible connections to real-world, household activities. Figure 3(c) illustrates projection coefficients categorized by typology and Fig. 4 illustrates an interval of the time-series with peaks classified by cluster. There is more variance and subclustering in the Type B peaks indicating that they correspond to the k=4 through 10 class in Fig. 3(b). For both classes, the “average” peak was constructed by using the coordinates of the centroid as projection coefficients, shown in Fig. 4(b). Type A peaks are characterized by relatively minor exceedances of the 60 threshold, a shorter duration, and a lower initial value. Type B peaks are, on the other hand, less attenuated, longer, and have higher initial values. Table 1 illustrates the mean and standard deviation of peak duration, maximum concentration, initial value, and area under the peak of the non-padded type A and Type B peaks.

Figure 4:

Cluster characteristics. (a) Example time-series graph of the type reviewed by the participant in the present study. Peak events are colored by cluster type. (b) “Average” peak from each cluster calculated by using each cluster’s centroid coordinates as the projection coefficients and adding back the previously-subtracted peak average. (c) Estimated distribution of peak start time classified by both cluster and intervention phase.

Table 1:

Mean values over all peaks of key features stratified by cluster. Standard deviations follows the mean in parentheses.

| Type A | Type B | |

|---|---|---|

| Duration in minutes | 4.3 (7.0) | 65.3 (48.2) |

| Maximum concentration | 106.4 (38.4) | 121.1 (40.3) |

| Initial concentration | 15.5 (12.2) | 40.0 (16.8) |

| Area under the peak | 309.3 (456.8) | 5447.4 (4344.7) |

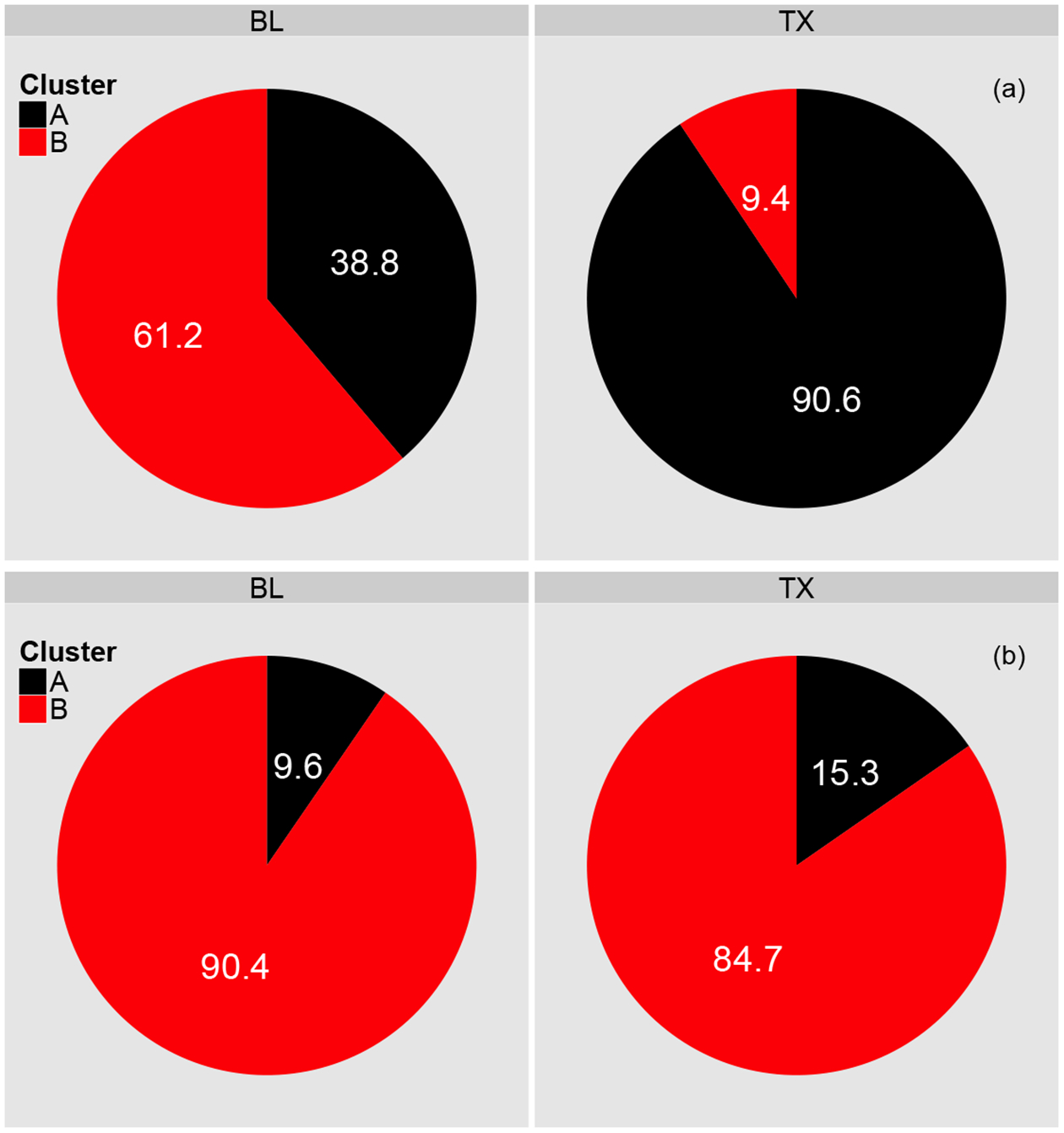

The POD/clustering procedure can be used to assess the effect of the intervention. As shown in Fig. 5, prior to the activation of the visual and audio feedback (BL phase), there were 49 total peaks (19 Type A and 30 Type B). In the TX phase, there were 64 total peaks (58 Type A and 6 Type B). The TX phase is 2.1 times longer than the BL phase so the effective number of peaks (and type of peaks) in the BL is obtained by multiplying by 2.1, i.e. 49·2.1 = 102.9, which is 1.61 times the number of peaks in the TX phase. A z-test can be used to assess the null hypothesis that the proportions of peak types in the BL and TX phases are equal by pooling the samples together and calculating the standard error of the difference between the proportions. A z-score is then calculated by dividing the difference between proportions by this standard error. For the above-detailed results, the p-value is < 0.01, indicating a statistically significant difference between the proportions.

Figure 5:

Intervention Effect. (a) Proportion of total number of peaks accounted for by each cluster stratified by intervention phase. (b) The same analysis but for proportion of total area under the curve.

Similar analysis can also be used to quantify the effect of the intervention on potential SHSe associated with peak events, quantified by the numerically-calculated area under the peaks. While the values reported are not indicative of true exposure that can be evaluated from a health-based perspective, this approach allows us to evaluate differences between the two phases of the intervention. In the BL phase, the total area under all 49 peaks was 169,300.2 , of which a proportion of 0.096 was accounted for by Type A peaks. In the TX phase, the total area under the peaks was 50,627.3 , of which a proportion of 0.153 was associated with the Type A cluster. The two-proportions z-test for area under the curve yielded a p-value of 0.37, indicating that, while a greater proportion of the area was associated with Type A peaks during the treatment phase, this difference was not statistically significant. The intervention did have the effect of reducing the overall exposure though. As described above, the effective area under the curve for the BL phase is calculated as as 169, 300.2·2.1 =355,530.4 μg·min. This value is just over 7 times as large as the exposure in the TX phase.

To summarize, the intervention was effective in reducing the number of peaks and the total area under these events. It also resulted in a more frequent occurrence of Type A peaks in the TX phase compared to the BL. This is a positive result since Cluster A is associated with smaller, possibly less harmful peaks. The difference in the proportion of area under the curve attributed to each cluster between the two phases was not statistically significant, despite the increased frequency of Type A peaks. This is likely due to the short duration of Type A peaks which have minimal effects on the area under the curve.

5.2. Relating Clustering to Household Activities

The above analysis provides information regarding the frequency and potential exposure due to peak events but does not address the ultimate goal of relating different types of peaks to household behaviors. To aid with this task, we use information obtained during coaching visits that occurred throughout the intervention. During these meetings, PFA coaches and study participants (SPs) reviewed graphs detailing air particle concentrations over the previous seven days. Specifically, time-periods with elevated concentrations were highlighted and the participants were asked to recall their behaviors at these times. In PFA, SPs seldom reveal that peaks are the result of tobacco smoking, even when other evidence of indoor tobacco use (e.g., cigarette butts in an ashtray) are observed. This was not the case for the subject home though, which is why it was selected to be summarized in this report. On 11/14/13, a version of the seven-day summary chart presented in Fig. 4(a) was reviewed by the SP and the home’s coach. This interaction focused, in part, on identifying strategies to reduce SHSe. Immediately following the coaching session, the monitor feedback was activated. The SP reported that the peak that occurred on Wednesday, 11/13/13 around 6:30 p.m. “happens because [her] husband lights his cigarette and then closes the back door.” More generally, the SP commented that her “husband smokes outside on the back patio at night time when he gets home from work.” In a subsequent visit on 11/27/13, the SP indicated that when she is not home her husband often “is home and is smoking in the house.”

The SP’s comments represent reports of smoking at specific times which we can cross–reference with our data. Table 2 provides a list of the 11 peak events for the time-period in Fig. 4(b). The 11/13/13 event is classified as Type B, as are eight of the other events. It may be the case then that the Cluster B events are associated with the husband’s cigarette smoking. Figure 4(c) illustrates the distribution of peak event start times for both cluster types and in both phases of the intervention. The mode of each distribution corresponds with the SP’s 6:30 p.m. report of her husband’s smoking. There is minimal difference between the Cluster B start time distributions from both phases. This is consistent with the evidence associating Cluster B with cigarette smoking and the SP’s report of her husband’s resistance to not smoking indoors. In contrast, the Cluster A distribution from the TX phase is more focused around 6:30 p.m. relative to the BL phase. Taken in conjunction with the sharp increase in the frequency of short-duration, cluster A peaks in the TX phase, this shift in the distribution may represent the husband taking steps to ensure that his after-work smoking less detrimentally affects the indoor environment. With this interpretation, the Type A peaks can be hypothesized to represent low-exposure events such as the lighting of a cigarette on the way out of the door or cigarette smoke drifting from outside into the home. Type B then could be associated with deviations from these behaviors and represent prolonged indoor smoking behavior. In PFA, though, the measures of human activity and the chemical composition of indoor air particles are too under-specified to allow this speculation to be either proved or disproved. As will be discussed later, the availability of verified information such as this would be a powerful tool for health promotion scientists to use when attempting to change household behaviors.

Table 2:

Tabulation of the peak events identified in Fig. 4(a).

| Start | End | Class |

|---|---|---|

| 11/07/13, 08:01:59 | 11/07/13, 09:56:09 | B |

| 11/08/13, 15:33:19, | 11/08/13, 15:41:49 | A |

| 11/09/13, 17:43:05 | 11/09/13, 19:00:15 | B |

| 11/09/13, 22:35:35 | 11/10/13, 02:32:19 | B |

| 11/11/13, 02:47:19 | 11/11/13, 03:33:29 | B |

| 11/11/13, 12:08:19 | 11/11/13, 12:35:59 | B |

| 11/11/13, 16:18:29 | 11/11/13, 16:45:09 | B |

| 11/11/13, 21:35:05 | 11/11/13, 22:51:55 | B |

| 11/12/13, 17:36:45 | 11/12/13, 17:39:45 | A |

| 11/12/13, 18:24:25 | 11/12/13, 19:51:25 | B |

| 11/13/13, 18:40:05 | 11/13/13,18:57:55 | B |

6. The Relationship of POD to Physical Parameters

When utilizing the POD/clustering algorithm, peak clusters are identified empirically and there is no explicit correlation to physical characteristics. To address this, we investigate the relationship between peak typology and parameters from a physics-based mass balance model of airborne particles. Model parameter estimates are calculated for each peak and are grouped by cluster. As will be demonstrated, this allows for the assessment of the POD/clustering algorithm’s ability to discriminate physical characteristics.

To model air particle concentration, consider the following first-order mass-balance equation that describes the dispersion of nonsorbing particles in a single zone [20, 21]:

| (4) |

where y(t) is the airborne concentration of particles at time t, V is the volume of the zone, e(t) is the particle emission rate at time t, and A is a rate coefficient for loss due to outdoor air exchange, particle deposition, and/or other first-order processes. It is likely that air exchange rate is the primary influence for A. We assume that the emission rate for a peak event, such as the smoking of a cigarette, is some constant ec for the duration of the particle generation and then zero otherwise, i.e.,

where te is the duration of the emission and tl is the length of an event. Equation (4) then has the exact solution

| (5) |

where κ ≡ ec/(V A) and . κ is the ratio of the particle source rate to the volume of air being displaced per unit time and ym is the maximum concentration, which occurs at te.

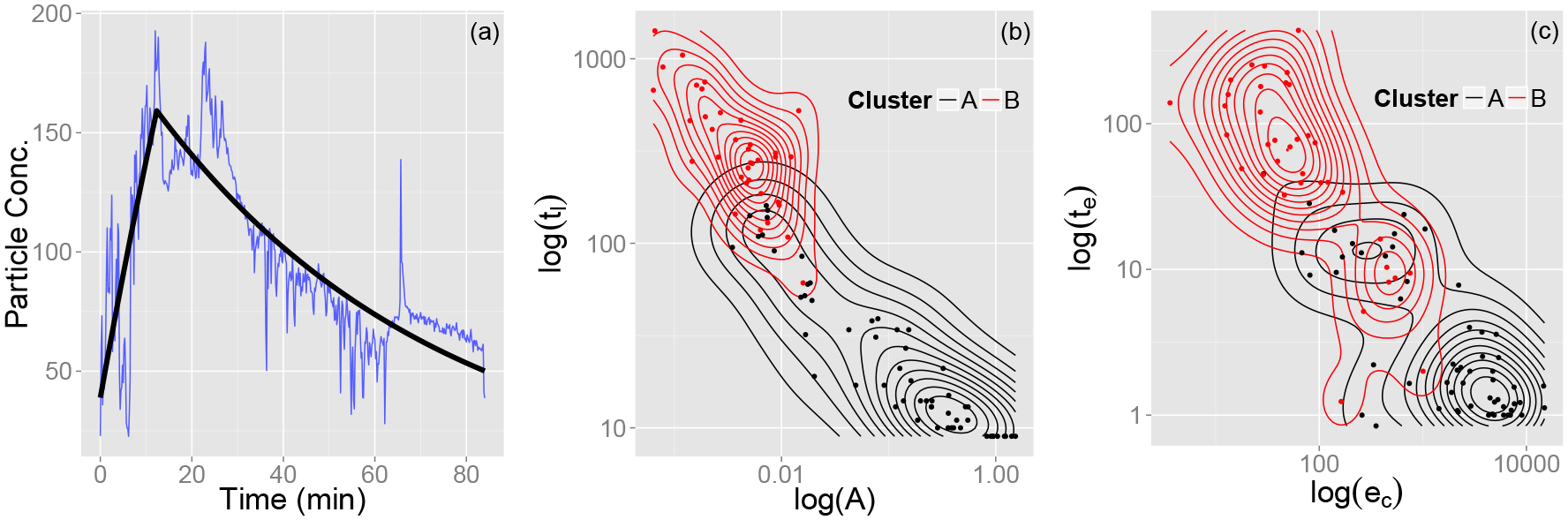

As measured by PFA staff, the volume of the room where the monitor was located is approximately 180m3. With V = 180m3, Eq. (5) is fit to each of the 113 peak events [see Fig. 6(a)] and a vector of parameters pi = (y0, ec, A, te, tl)T is extracted for i = 1, …, 113. The parameter tl is not extracted from the fit, but is instead set equal to the duration of the original event. Prior to the curve fitting, the one-minute that had been appended to the beginning of each event was removed since this flat time-period diluted the peak characteristics for short-duration peaks and had little effect on the fit for long-duration peaks. The fitting procedure did not converge for 18.6% of the events, primarily due to Eq. (5) being over-parametrized for the shortest-duration peaks.

Figure 6:

Parameter fitting and estimated density distributions. (a) The fitting of Peak 53 (in temporal order) to Eq. (5). (b) A log-log plot of the two-dimensional kernel density estimates of the parameter distribution in (A, tl)-space. (c) A log-log plot of the two-dimensional kernel density estimates of the parameter distribution in (ec, te)-space.

The (A, tl)-space corresponds in some sense to household characteristics since it encompasses the decay rate and the duration required for indoor air concentrations to fall below 40 .· (ec, te)-space, on the other hand, corresponds to behavioral characteristics concerning the magnitude and duration of a particle generating event. Figures 6(b) and (c) illustrate two-dimensional kerneldensity estimates, calculated using the ks package in the R Statistical Software [22], of these two parameter subspaces stratified by cluster. Kernel density estimation consists of the use of data smoothing to empirically estimate a probability density function [23]. We see that, while overall the POD does a satisfactory job of discriminating between the physical parameters, there is less overlap in the case of (A, tl). This indicates that the POD is more successful in identifying differences in these parameters as opposed to (ec, te). Similar differences in typology distributions exist for other pairs of variables not shown here.

We now seek to determine the accuracy of the POD/clustering algorithm at identifying peaks from each distinct physical parameter class using a bootstrap-type methodology. Let PA represent the sets of fitted parameters associated with the Type A peaks and PB be the sets of parameters associated with the Type B peaks. As detailed in Section 5, 77 Type A peaks were identified so we sample 77 parameter sets (pi), with replacement, from PA. Similarly, we sample 36 parameter sets from PB. The POD/clustering analysis (with the same specifications as in Section 5) is then performed on these sample peaks and each peak’s classification is compared with its original class for consistency. This procedure was repeated 1,000 times and the average ratios of correct identification over these trials were calculated. Type A peaks were accurately identified 68.2% of the time and Type B peaks were correctly identified 64.7% of the time. For our purposes, this is an acceptable level of accuracy. The misidentification of peaks can be due to one or more of several factors. First, the 18.6% of peaks that were not able to be fit to Eq (5) were all from Cluster A and were, in most cases, the shortest duration events, i.e. the most dissimilar from Cluster B. This likely biased the findings. Second, while the POD and curve fitting exercises can both be interpreted as dimensionality reduction techniques, the curve fitting is much more rigid than the POD in terms of what features can be extracted. Finally, as shown in Figure 6(b)–(c), there is an overlap between typology parameter distributions which complicates the clustering procedure. Overall though, the POD satisfactorily identifies features from this first-order physics model.

7. Discussion

Intensive air particle concentration time-series data were generated from a health-behavior intervention aimed at reducing household SHSe. Peak events were extracted from the time-series and transformed so that POD could be used to project the peaks into a lower-dimensional space. After using analytic metrics to obtain the optimal number of clusters, a k-means algorithm was used to partition the peaks into two classes. Once the aversive stimuli component of the intervention was activated, effects were observed in the form of a decreased number of peaks and an increased frequency of short-duration, attenuated, Type A peaks. Peak classification was cross-referenced with SP-reported information about household behaviors to generate evidence that Type B peaks were associated with indoor smoking. The distribution of peak event start times also provided insight into how household members were adjusting their behavior in response to the intervention. A relationship was also identified between the POD-defined clusters and physical parameters obtained from fitting the peaks to the solution of a parsimonious ordinary differential equation.

The results summarized in the previous paragraph represent a case-study of one home, chosen due to the willingness of the SP to report indoor smoking. While preliminary analyses have indicated certain findings are robust among many homes (e.g., k = 2 as the optimal number of clusters), the extent to which these conclusions are generalizable to other homes is not known and requires additional investigation. In particular, more accurate information about the household behaviors associated with specific peaks is required, possibly via studies utilizing intensive ecological momentary assessments. This information will also allow for the exploration of the association between the subclustering identified in the Type B cluster and different classes of particle sources. Furthermore, the procedures described herein can be refined and alternate decomposition techniques (e.g., wavelet analysis) can be explored. As we move forward and the dynamics of more homes are identified, it is possible that we will gain the ability to efficiently characterize homes which are not intensely monitored into household archetypes which will allow us to modify the intervention based on archetype characteristics.

From a larger vantage point, PFA and other real-time and mobile technology based studies enable precise measures of behavior as it takes place in a natural environment, such as the home for PFA. This ability will radically transform interventions for disease prevention and treatment towards those that are suitable for adaptive technologies [24, 25] and personalized treatment that tailors interventions in real-time to the particular conditions at hand [1]. The social and behavioral science theories on which traditional interventions are based typically rely on hypothetical constructs, notably cognitions and personal decision making, as mediators of important human behavior. It has been suggested that extant cognitive models do not inform the advancement of models of real-time objective behavior [26]. Contextual behavioral science [27] provides alternatives to cognitive-based models such as the Behavioral Ecological Model (BEM), which asserts behavior as an extension of biology with contributions from chemistry and physics [28]. Fundamental to this theory are Principles of Behavior that define operant behavior as a function of immediate consequences rather than cognitions. This model relies almost exclusively on objective measures of behavior and, as such, it is well-suited to inform real-time measurements and to be informed by the results of real-time and mobile measures.

As mobile technology becomes more ubiquitous, adaptive interventions are beginning to be implemented. For example, the ability to employ automatic shaping mechanisms has been established for physical activity [29]. While our measurements are too crude to achieve high-fidelity use of behavioral principles, this study lays the groundwork to move tobacco control, specifically the control of SHSe, in this direction by gauging behavior in a variety of data-intensive, dynamic contexts, which is not the case for typical intervention models. As technological advances allow for a more comprehensive specification of behaviors, the knowledge gained by the data-centric techniques developed in studies like this will prepare us to take full advantage of the technology in many fields including, but certainly not limited to, tobacco control. Furthermore, in a synergistic process, studies such as this will identify information gaps and poorly-specified variables that can serve as a road map for the development of more precise technology.

Highlights.

A POD/k-means clustering algorithm classified time-series peaks into one of two empirically-defined classes.

A behavioral intervention increased the proportion of peaks from the class associated with shorter durations.

Distinguishing physical properties of the peaks were identified with > 60% accuracy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank PFA staff for the implementation of the intervention from which this data was collected and the households that participated in the study. We also thank Sandy Liles for his review of the document. Research reported in this publication was supported by NHLBI of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01HL103684. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work was also supported by the San Diego State University Computational Science Research Center and the ARCS Foundation.

Biographies

Vincent Berardi: Vincent Berardi holds a B.S. in Mathematics from Saint Peter’s College (N.J.) and an M.S. in Applied Mathematics from San Diego State University. He is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Computational Sciences through a joint program at San Diego State University and Claremont Graduate University. Mr. Berardi’s research is at the nexus of real-time, mobile technology and health interventions, focusing on the incorporation of behavioral principles into these processes. His approach includes the use of dynamical systems analyses, modeling simulations, and statistical techniques.

Ricardo Carretero: Prof. Carretero holds a Summa Cum Laude B.Sc. in Physics from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, UNAM (1992) and a Ph.D. in Applied Mathematics and Computation from Queen Mary College, University of London, UK (1997). He was a post-doc at the Centre for Nonlinear Dynamics, University College London, UK, and was a PIMS Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada. He started as an Assistant Professor in Applied Mathematics at San Diego State University (SDSU) in 2002, and was promoted to Associate Professor in 2006 and to Full Professor since 2009. His research focuses in spatiotemporal dynamical systems, nonlinear waves and its applications. He is the co-founder and co-director of the Nonlinear Dynamical Systems (NLDS) group at SDSU. He has received multiple NSF grants, published more than a hundred peer-reviewed publications, including 3 co-authored/edited books. He is an active advocate of the dissemination of science, he continuously delivers engaging presentations at local high schools and science festivals, and helps in the design of museum exhibits.

Neil Klepeis: Neil E. Klepeis holds an M.S. in Chemistry from Stanford University and a Ph.D. in Environmental Health Sciences from the University of California at Berkeley. As an adjunct SDSU professor and owner of an environmental-health technology firm, he performs R&D at the nexus of environmental and toxic-exposure monitoring, simulation modeling, and behavioral health. He has contributed 40+ publications related to tobacco smoke, exposure modeling, and real-time monitoring & feedback. He seeks to combine the environmental and behavioral fields through modeling, designing and implementing innovative behavioral approaches that protect air quality and other resources vital to human health and wellbeing.

Antonio Palacios: Antonio Palacios received his Ph.D. in Mathematics at Arizona State University. He was a postdoctoral fellow in Mathematics and also in Physics at the University of Houston from 1996–1999. He joined the Math Department at San Diego State University in 1999 and has been a full professor since 2008. His research interests are in modeling complex nonlinear systems. In particular, multidisciplinary nonlinear systems that interface with Biology, Engineering, and Physics. Over the past twelve years he has been collaborating the Space and Naval Warfare (SPAWAR) Center, San Diego to design and fabricate innovative technologies. Prof. Palacios’s publications reflect a dual interest in Applied Mathematics and Engineering, linked through ideas and methods from the theory of Nonlinear Dynamical Systems. He holds seven approved U.S. Patents and four more pending.

John Bellettiere: John Bellettiere holds a Masters of Arts degree in economics and a Masters in Public Health in behavioral science and health promotion. He is pursuing a PhD in epidemiology were his studies focus on non-invasive health-related sensors to solve public health problems. John is interested in developing, evaluating, and using sensors to passively collect data on health outcomes and potential behavioral, physiologic, and environmental risk factors. His research space includes physical activity and sedentary behavior measured by accelerometers and inclinometers and second hand smoke exposure measured by light refracting particle sensors.

Suzanne Hughes: Suzanne Hughes is a Research Investigator and Co-Director at the Center for Behavioral Epidemiology & Community Health, and an Adjunct Associate Professor, Graduate School of Public Health, at San Diego State University. She has a B.A. in Chemistry and an M.P.H. and a Ph.D. in Public Health-Epidemiology. Her research focuses mainly on epidemiological, clinical, and community trials in the areas of maternal and child health, alcohol use, tobacco use, secondhand smoke exposure, diet, and immigrant health.

Saori Obayashi: Saori Obayashi is a Registered Dietitian and received a Ph.D. in Human Nutrition from Michigan State University. She is currently a postdoctoral student with Project Fresh Air and manages the daily operations of this project. Her research interests include obesity and related disease prevention, health disparity, and community nutrition intervention.

Melbourne Hovell: Dr. Hovell obtained an MA (1973) in Operant Psychology, Western Michigan University; Ph.D. (1976) in Human Development, University of Kansas; and MPH (1981) in Epidemiology, UC, Berkeley. He was a Senior Research Associate, and Adjunct Assistant Professor in Medicine and Human Biology, Stanford University, 1976–1982. He founded (1982) the Health Promotion Division and The Center for Behavioral Epidemiology (1988) and Co-founder of Ph.D. programs in clinical psychology; epidemiology and health behavior. Dr. Hovell promoted the Behavioral Ecological Model (BEM) as the basis for over 87 Federal, State and Foundation grants, 330 publications, and advancement of hundreds of graduate students.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Bibliography

- [1].Patrick K, Griswold WG, Raab F, Intille SS, Health and the mobile phone, American Journal of Preventive Medicine 35 (2) (2008) 177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Klepeis NE, Hughes SC, Edwards RD, Allen T, Johnson M, Chowdhury Z, Smith KR, Boman-Davis M, Bellettiere J, Hovell MF, Promoting smoke-free homes: A novel behavioral intervention using real-time audio-visual feedback on airborne particle levels, PLOS ONE 8 (8) (2013) e73251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bellettiere J, Hughes SC, Liles S, Boman-Davis M, Klepeis NE, Blumberg E, Mills J, Berardi V, Obayashi S, Allen TT, et al. , Developing and selecting auditory warnings for a real-time behavioral intervention, American Journal of Public Health Research 2 (6) (2014) 232–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Abrard F, Deville Y, A time–frequency blind signal separation method applicable to under-determined mixtures of dependent sources, Signal Processing 85 (7) (2005) 1389–1403. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Berné O, Joblin C, Deville Y, Smith J, Rapacioli M, Bernard J, Thomas J, Reach W, Abergel A, Analysis of the emission of very small dust particles from spitzer spectro-imagery data using blind signal separation methods, Astronomy & Astrophysics 469 (2) (2007) 575–586. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Jung T-P, Makeig S, Humphries C, Lee T-W, Mckeown MJ, Iragui V, Sejnowski TJ, Removing electroencephalographic artifacts by blind source separation, Psychophysiology 37 (02) (2000) 163–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Torkkola K, Blind separation for audio signals-are we there yet?, in: Proc. Workshop on Independent Component Analysis and Blind Signal Separation, 1999, pp. 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Loève M, Probability Theory, Van Nostrand, New York, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dunteman GH, Principal components analysis, no. 69, Sage, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Fowler A, Kember G, Singular systems analysis as a moving-window spectral method, European Journal of Applied Mathematics 9 (01) (1998) 55–79. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Trefethen LN, Bau D III, Numerical linear algebra, Vol. 50, Siam, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Palacios A, Gunaratne G, Gorman M, Robbins K, A Karhunen-Loève analysis of spatiotemporal flame patterns, Phys. Rev. E 57 (1998) 5958–5971. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Back AD, Weigend AS, A first application of independent component analysis to extracting structure from stock returns, International Journal of Neural Systems 8 (04) (1997) 473–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bankó Z, Dobos L, Abonyi J, Dynamic principal component analysis in multivariate time-series segmentation, Conservation, Information, Evolution 1 (1) (2011) 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Vautard R, Yiou P, Ghil M, Singular-spectrum analysis: A toolkit for short, noisy chaotic signals, Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 58 (1) (1992) 95–126. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sirovich L, Turbulence and the dynamics of coherent structures, part I: Coherent structures, Q. Appl. Math XLV (1987) 561–572. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Pelleg D, Moore AW, et al. , X-means: Extending k-means with efficient estimation of the number of clusters, in: ICML, 2000, pp. 727–734. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Rousseeuw PJ, Silhouettes: a graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis, Journal of computational and applied mathematics 20 (1987) 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Tibshirani R, Walther G, Hastie T, Estimating the number of clusters in a data set via the gap statistic, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 63 (2) (2001) 411–423. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ott W, Langan L, Switzer P, A time series model for cigarette smoking activity patterns: Model validation for carbon monoxide and respirable particles in a chamber and an automobile, Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology 2 (2) (1992) 175. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Klepeis NE, Nazaroff WW, Modeling residential exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke, Atmospheric Environment 40 (23) (2006) 4393–4407. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Duong T, ks: Kernel smoothing, r package version 1.9.3 (2014). URL http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ks

- [23].Duong T, ks: Kernel density estimation and kernel discriminant analysis for multivariate data in r, Journal of Statistical Software 21 (7) (2007) 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Steinhubl SR, Muse ED, Topol EJ, Can mobile health technologies transform health care?, JAMA 310 (22) (2013) 2395–2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Phillips G, Felix L, Galli L, Patel V, Edwards P, The effectiveness of M-health technologies for improving health and health services: a systematic review protocol, BMC research notes 3 (1) (2010) 250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Riley WT, Rivera DE, Atienza AA, Nilsen W, Allison SM, Mermelstein R, Health behavior models in the age of mobile interventions: are our theories up to the task?, Translational Behavioral Medicine 1 (1) (2011) 53–71. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0021-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].De Houwer J, Roche B, Dymond S, Advances in relational frame theory: Research and application, New Harbinger Publications, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hovell MF, Wahlgren D, Adams M, The logical and empirical basis for the behavioral ecological model, Emerging Theories and Models in Health Promotion Research and Practice. Strategies for Enhancing Public Health. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; (2009) 415–449. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Adams MA, Sallis JF, Norman GJ, Hovell MF, Hekler EB, Perata E, An adaptive physical activity intervention for overweight adults: a randomized controlled trial, PLOS ONE 8 (12) (2013) e82901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]