Abstract

Relationships with pet dogs are thought to provide substantial benefits for children, but the study of these relationships has been hindered by a lack of validated measures. Approaches to assessing the quality of children's pet dog relationships have tended to focus on positive relationship qualities and to rely on self‐report questionnaires. The aim of this study was to develop and test multiple measures that could be used to assess both positive and negative features of children's relationships with pet dogs. In a sample of 115 children ages 9–14 years who were pet dog owners, we assessed six qualities of pet dog relationships: Affection, Nurturance of Pet, Emotional Support from Pet, Companionship, Friction with Pet, and Pets as Substitutes for People. All qualities were assessed with child questionnaires, parent questionnaires, and child daily reports of interactions with pets. We found substantial convergence in reports from different observers and across different measurement approaches. Principal components analyses and correlations suggested overlap for many of the positive qualities, which tended to be distinct from negative relationship qualities. The study provides new tools which could be used to test further how relationships with pets contribute to children's development.

Keywords: dogs, human‐animal interaction, measures, pets, pet dog relationships

1. INTRODUCTION

The preadolescent years (ages 9–12 years) are a time of social challenge for children. Relationships with close human partners (parents and friends) are well‐established as buffers against adversity, and it may well be that human‐animal relationships can serve similar roles (Walsh, 2009). Most children live with pets (approximately 65–75% Esposito et al., 2011; Walsh, 2009), which means pets are a widely available source of support. In middle childhood, pets—including dogs—are described by children in ways that suggest they provide many of the benefits of friendship such as companionship, support, and affection (e.g., McNicholas & Collis, 2000; Morrow, 1998). Surprisingly, given the high ownership of pets, Human Animal Interactions (HAI) with therapy animals has been studied more extensively than children's HAI with pets (Esposito et al., 2011; Kerns et al., 2017; Mueller, 2014). In addition, many studies of pets focus on pet ownership, but there is also a need to investigate the importance of the quality of relationships with pets (Esposito et al., 2011; Mueller, 2014).

Different conceptual approaches have been taken to describe the quality of children's relationships with pets (e.g., attachment, companionship), and the lack of a unifying framework has hindered research (Hurley, 2014; Kerns et al., 2017). Further, a lack of validated measures has created a barrier to progress, as different measures are used in different studies, resulting in a lack of replication (Esposito et al., 2011; Mueller, 2014). The development of valid and reliable instruments could stimulate research on HAI and could advance the field by allowing investigators to study the role of pets within the context of other factors instead of focusing on pets in isolation (Kerns et al., 2017; Mueller, 2014). Also, measures could be integrated into longitudinal studies that have another primary aim (Esposito et al., 2011). Finally, studies investigating pets have often included children with any type of pet, even though there may be key differences in the types of support different species can provide. Dogs may be especially salient providers of social support given that they seek social interaction, are loyal and nonjudgmental, and can respond to human behavioral and emotional cues (Jalongo, 2015; Walsh, 2009). Experimental studies with children also show that the presence of a pet dog can enhance children's coping with stress (Kerns et al., 2017; Kertes et al., 2017).

The goal of this study was to develop and provide a preliminary test of measures to assess individual differences in the quality of children's relationships with their pet dogs. We focus on children's relationships with their pet dogs given their potential as support figures. We included children in later middle childhood and early adolescence given their ability to complete self‐report measures and the high pet ownership levels for families with children at this age (Esposito et al., 2011). Although our study focuses on children's relationships with pet dogs, most studies of pet relationship quality include all types of pets, and therefore our overview of the literature includes studies that broadly investigated pet relationships. We do note when studies specifically focused on pet dogs.

1.1. The need for new measures of children's relationships with pet dogs

Preadolescents describe pets as friends and view them as sources of social interaction and emotional support (Bryant, 1990; Davis & Juhasz, 1995). Pets are also credited with reducing children's stress (Covert et al., 1985; Guerney, 1991; Mueller & Callina, 2014) and enhancing emotion regulation (Bryant & Donnellan, 2007; Mueller, 2014). In addition to ameliorating deficits or negative emotions, interactions with animals can promote positive youth development such as thriving (Mueller, 2014). Although it is clear that pets matter to children, there are some gaps in our understanding of pets and their importance to children.

One difficulty in integrating findings in this literature is the lack of a common framework to describe children's relationships with pets. For example, some studies assess pet relationships along a single dimension of closeness (Melson, 2003), whereas others focus on specific relationship qualities (e.g., companionship; Bryant & Donnellan, 2007; Cassels et al., 2017). Almost all studies focus on the positive qualities of pet relationships, and the negative qualities have not been systematically studied (see Kertes et al., 2018 and Cassels et al., 2017, for exceptions). Friends can influence children through their negative interactions (e.g., conflict; Berndt & McCandless, 2009), and similarly it may be important to capture negative interactions with pets to fully describe these relationships. Although pet relationships are sometimes referred to as attachments, we do not use this term as we do not believe these relationships meet classical definitions of the term (e.g., do not serve same security functions, Collis & McNicholas, 1998). Rather, we view children's relationships with dogs as affectional bonds (Ainsworth, 1989).

The lack of a single conceptual framework has also resulted in a diverse set of measures, with few developed specifically for children (Wilson & Netting, 2012). One approach to measurement has been to adapt a measure of social provisions in human close relationships, the Network of Relationships Inventory (NRI), to assess qualities of children's relationships with pets. Studies that have used the NRI have varied in which qualities were assessed; for example, to assess negative interactions with pets Cassels et al. (2017) used the conflict scale whereas Kertes et al. (2018) used the antagonism scale to assess negative interactions with dogs. Specific qualities such as intimacy in pet relationships have been measured with the NRI (Bryant & Donnellan, 2007; Cassels et al., 2017), although some studies have derived a single measure of pet dog relationship support based on multiple positive qualities (Hall et al., 2016; Kerns et al., 2017; Kertes et al., 2018). Other investigators have used the Lexington Attachment Scale (LAPS; Johnson et al., 1992)—initially developed for adults—or the CENSHARE Pet Attachment Scale (Westgarth et al., 2013), both of which can be used to obtain an overall measure of positive pet relationship quality (Bures et al., 2019; Charmaraman et al., 2020; Madden Ellsworth et al., 2017; Westgarth et al., 2013). Items for these measures were developed specifically for assessing children's relationships with pets. Although the LAPS has subscales (general attachment, animal rights/welfare, people substituting), they are not consistently used in research, and one of the scales (animal rights/welfare) is a measure of attitudes toward animals rather than a measure of pet relationship quality.

Another limitation in studies of child‐pet relationships is an almost exclusive focus on child questionnaires and interviews to assess pet relationship quality that rely on global judgements about the relationship. Given the sparse research, these approaches were necessary to provide initial evidence on the importance of pets for children. Nevertheless, there is a need to extend work by developing and rigorously testing other types of measures and consider other informants (Esposito et al., 2011; Mueller, 2014). Child questionnaires can be supplemented with parent reports to determine if these two informants have similar views of the relationship. In addition, daily diaries have been used with children in middle childhood to capture everyday experiences with family members (Sun et al., 2021) and could also be used to capture children's everyday experiences with pet dogs in naturalistic contexts (e.g., instead of asking children if they take care of their pet, asking if they took care of the pet that day).

1.2. Development of a new measure of pet dog relationship quality

In this study, we sought to develop and test broad measures of pet dog relationship quality, assessing both positive and negative relationship qualities, as doing so would advance the field by providing comprehensive measures that could be used consistently across studies (Kerns et al., 2017). We focused on dogs given that they are the most common household pet (Bures et al., 2019; Westgarth et al., 2013), children report higher levels of closeness and satisfaction in relationships with dogs compared to other pets (Cassels et al., 2017; Westgarth et al., 2013), and dogs are especially sensitive to social cues (Jalongo, 2015). Ideally, such measures would allow for assessing specific relationship qualities (e.g., companionship, intimacy) as well as yielding broad measures of relationship quality (e.g., support, negative interactions) so studies could test hypotheses about the importance of specific relationship qualities (e.g., the hypothesis that nurturing pets promotes prosocial behavior in children; Melson, 2003). In addition, the content of the measures would reflect the types of interactions and relationship qualities found in child‐dog relationships. To address these issues, we developed a conceptual framework of child‐dog relationship qualities that could guide the development of measures of this relationship.

Consistent with a social provisions perspective on close relationships (Furman & Buhrmester, 1985), our conceptual framework includes relationship qualities that can fulfill social needs. Discussions of the benefits of pet relationships (e.g., Mueller, 2014; Walsh, 2009) commonly identify four positive relationship qualities: Affection, Emotional Support from pet, Companionship, and Nurturance of pet. Although pets provide many benefits, there are also costs (e.g., time commitment, annoying pet habits, etc.; Bryant, 1990). Seeking support from pets in place of human support is sometimes offered as a potential positive benefit of pets (e.g., Johnson et al., 1992). Yet research suggests that the receiving inadequate support from parents—and reliance instead on alternative figures such as peers—is associated with poorer adjustment in children (Kerns & Brumariu, 2016); thus, we view a preference to rely on pets rather than humans as a potentially negative quality. Friction is included to capture negative interactions with pets, which have rarely been studied in children. Taken together, we propose a framework for assessing the quality of children's relationships with pets that includes six qualities: Affection, Nurturance, Emotional Support, Companionship, Friction, and Pets as Substitutes for People.

We then developed a multi‐method approach to assessing these relationship qualities. Specifically, we developed child and parent questionnaires to assess global perceptions of the quality of children's relationships with pet dogs and daily report measure that included behaviorally specific indicators of these same six qualities. We then evaluated the new measures by examining their reliability and validity, including their structure and convergence across measures, to provide an initial test of the validity of the measures.

2. METHOD

2.1. Preliminary studies: Development of pet questionnaire

We developed a new questionnaire measure for children 9 years and older to assess pet relationship quality. We focused on this age for several reasons. First, families with children in this age range are especially likely to own pets (Esposito et al., 2011). In addition, we wanted to develop self‐report measures that could be readily incorporated into studies, and so we focused on developing child self‐report methods that could be administered and scored without extensive training or coding by researchers. We focused on children 9 years and older given evidence that by later middle childhood (compared to younger ages) children are less likely to show extreme responding in their subjective ratings (Chambers & Johnston, 2002) and show better memory and more accurate reporting of family events (Taber, 2010).

We began by conducting a content analysis to identify qualities of pet relationships that had been identified either on prior questionnaires of pet relationship quality or in interview studies in which children reported about their relationships with pets. From this review, we identified six distinct relationship qualities: affection for the pet, nurturance (care of) the pet, emotional support from the pet, companionship with the pet, friction with pet (e.g., pet annoys child), and pet as substitute for people.

Next, we wrote a questionnaire with 5‐item scales for each of the six identified qualities (30 items total). Each item was rated on a 5‐point scale. We created a child version (self‐report) and a parent version (parent reporting about child's relationship with a pet dog), and we piloted the questionnaire with 14 children (9–17 years of age) and their parents. We found good internal consistency alphas for most scales (.70 to .90), although alphas were lower for child reports of Affection (.61) and Emotional Support (.55) and parent reports of Companionship (.61). Based on examination of item‐total correlations, we identified five items that were problematic; we reworded or replaced these items and then used this modified version in the current main study. In addition, to provide a second approach to assessing these six relationship qualities, we created a new daily log measure, which is described below.

2.2. Participants

The sample included 116 children from 105 families (including 11 sibling pairs) who participated with a pet dog (siblings participated with different dogs). Sample size was determined a priori based on power analyses to determine the sample size needed to detect medium sized effects. Children were ages 9–14 years (M age = 10.93, SD = 1.26), with 15 9‐year‐olds, 34 10‐year‐olds, 25 11‐year‐olds, 12 12‐year‐olds, 11 13‐year‐olds, and 2 14‐year‐olds. Families, who resided primarily in Midwestern small towns, were recruited through letters distributed at schools and flyers posted in the community (e.g., libraries, veterinary offices). The sample was 50.0% female and 86.8% White (2.6% Native American, 1.8% Asian/Pacific Islander, 1.8% Black/African American, 7.0% other). Most children attended public schools (85.3%; 6.9% private religious schools; 7.8% homeschool), and 10.3% were eligible for free or reduced lunches. Children were from families with two biological parents (73.3%), a biological parent and a step‐parent (12.9%), a single parent (9.5%), or another status (e.g., had a grandparent as a guardian, 4.3%). Data for one child was excluded as the child had great difficulty completing the questionnaires, leaving a final sample of 115 children.

Children most often described the dog as primarily a family pet (73%; 21% reported the dog was primarily their pet and 6% reported the dog was primarily another family member's pet). Parents reported additional information about the dogs. Regarding dog age, for the sample 10% were 6–11 months old, 22% were 1–2 years old, 37% were 3–5 years old, 24% were 6–10 years old, and 8% were over 10 years old. All dogs had been owned by their families for at least 3 months, and 87% had been with the family for at least one year. Per parent report, 45% of dogs were purebreds (parents reported a diverse range of breeds), 85% of the dogs were spayed or neutered, all were in good health and vaccinated against rabies, and 89% were reported to be comfortable around other dogs. Thus, the sample of dogs was described by parents as generally physically and mentally healthy.

By March 2020, when the COVID‐19 pandemic emerged in the United States, all families had been recruited, and data had been collected from 98 children. The remaining 18 children (16% of the sample) participated using enhanced safety protocols (14 children in person, with data collection outdoors with project staff wearing masks and shields and parents and children wearing masks; four children and their parents completed questionnaires during a live online meeting). We therefore did preliminary analyses (t‐tests) to determine if responses differed for those who participated pre‐ or post‐pandemic. These comparisons were made for all variables that assessed pet relationship quality (questionnaires completed by the child and parent as well as the child daily log measures; described below). None of these comparisons were statistically significant (p < .05), so we pooled all data for analysis.

2.3. Procedures

Teams of two research assistants made one‐time visits to families in their homes to collect the data. Upon arrival, the researchers explained the procedures and obtained parent consent and child assent. Then, children completed questionnaires about their relationship with their pet dog (parents were separated from the child so that the child could complete questionnaires in private). Children also completed other tasks that are not part of this report. Meanwhile, parents provided demographic information about the family and about their child's relationship with their pet dog. Then, the researcher explained the seven‐day daily log to the child in front of their parent. Children were to complete these daily log sheets once per day at the end of the day for seven consecutive days, beginning the day after the in‐home visit. If they forgot to complete a report on any particular day, children were asked to do it the day after and to write in the date that they actually completed the diary. Children and parents were asked to return the daily logs via a postage paid envelope provided at the in‐home visit, and 100 children (of the 115; 87%) returned daily logs.

The parent and child were each given $25.00 for their participation, and the family was given a $25.00 gift card to a pet store. Children received an additional $25.00 for returning the seven‐day daily log.

3. MEASURES

3.1. Questionnaire measures of the child‐dog relationship (Appendix A and B)

3.1.1. Pet dog relationship inventory: Child report and parent report

The overall quality of children's relationships with their pet dog was assessed using a newly developed “Pet Dog Relationship Inventory” (PDRI; items in Appendix A). The PDRI asks children to reflect on how much they feel or act in certain ways using a 5‐point scale (1 = Almost always true; 5 = Almost never true). The measure contains 30 items, and these items correspond with six child‐dog relationship quality scales (5 items each): (1) Affection (e.g., “I love my pet”); (2) Nurturance of Pet (e.g., “I help take care of my pet”); (3) Emotional Support from Pet (e.g., “When I am upset, being with my pet helps me feel better”); (4) Companionship (e.g., “My pet and I spend a lot of time together”); (5) Friction with Pet (e.g., “I get mad at my pet”); and (6) Pet as Substitute for People (e.g., “I would rather spend time with my pet than anyone else”). The six quality scores were derived by averaging across the five respective items for that scale, with higher scores indicating greater endorsement of that quality. Cronbach's alphas were calculated separately for each quality scale and are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive statistics for child report of pet dog relationship

| Range of scores obtained | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Min | Max | M | SD | Cronbach's Alpha | |

| Pet dog relationship inventory: Child | ||||||

| Affection | 113 | 3.20 | 5.00 | 4.71 | .37 | .61 |

| Nurturance of pet | 114 | 2.40 | 5.00 | 4.24 | .71 | .78 |

| Emotional support from pet | 114 | 1.40 | 5.00 | 4.12 | .72 | .73 |

| Companionship | 114 | 1.60 | 5.00 | 4.06 | .69 | .75 |

| Friction with pet | 114 | 1.00 | 3.80 | 2.05 | .67 | .70 |

| Pet as substitute for people | 114 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.51 | .97 | .87 |

| Pet dog relationship inventory: Parent | ||||||

| Affection | 115 | 2.40 | 5.00 | 4.56 | .55 | .82 |

| Nurturance of pet | 115 | 2.00 | 5.00 | 3.91 | .77 | .83 |

| Emotional support from pet | 115 | 1.80 | 5.00 | 3.79 | .79 | .78 |

| Companionship | 115 | 1.60 | 5.00 | 3.85 | .74 | .77 |

| Friction with pet | 115 | 1.00 | 3.20 | 1.59 | .54 | .72 |

| Pet as substitute for people | 115 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.62 | .93 | .85 |

| LAPS ‐ Overall | 115 | 2.61 | 3.96 | 3.54 | .27 | .79 |

| NRI ‐ Overall | 115 | 2.50 | 5.00 | 3.99 | .56 | .87 |

| Daily logs: Behavioral report | ||||||

| Affection | 100 | .14 | 1.00 | .96 | .13 | .87 |

| Nurturance of pet | 100 | .00 | 1.00 | .63 | .31 | .88 |

| Emotional support from pet | 100 | .00 | 1.00 | .45 | .29 | .88 |

| Companionship | 100 | .07 | 1.00 | .81 | .22 | .85 |

| Friction with pet | 100 | .00 | .71 | .11 | .16 | .78 |

| Pet as substitute for people | 100 | .00 | 1.00 | .51 | .34 | .91 |

| Daily logs: Pet relationship quality ratings | ||||||

| Affection | 100 | 1.57 | 5.00 | 4.38 | .67 | .87 |

| Nurturance of pet | 100 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 4.05 | .92 | .91 |

| Emotional support from pet | 100 | 1.43 | 5.00 | 4.35 | .72 | .87 |

| Companionship | 100 | 1.29 | 5.00 | 4.01 | .76 | .89 |

| Friction with pet | 100 | 1.00 | 3.86 | 1.54 | .63 | .86 |

| Pet as substitute for people | 100 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.26 | 1.12 | .95 |

Parents were also asked to complete the PDRI (Appendix B). The parent version was exactly the same as the child version (30 items; six scales with five items each), with the exception that parents are asked to report on their child's relationship with their pet dog, rather than their own relationship with a pet dog. Thus, for example, parents are asked to indicate on the 5‐point scale (1 = Almost never true; 5 = Almost always true) how true the statement “My child loves this pet” is for their child (see Table 1 for scale alphas). Cronbach's alphas were calculated separately for each quality scale and are listed in Table 1.

3.1.2. Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale (LAPS)

The overall quality of children's relationships with their pet dog was also assessed using the Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale (LAPS; Johnson et al., 1992). Children were asked to indicate whether they agreed or disagreed with 23 brief statements about their favorite pet dog (e.g., “I believe my dog is my best friend”) and about other people (e.g., “Quite often, my feelings toward people are affected by the way they react to my dog”). Items were scored on a 4‐point scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree. Overall child‐dog relationship quality scores were derived by reverse scoring the negatively worded statements (e.g., “I am not very attached to my dog”) and then calculating an average score across all 23 items. Higher average scores indicate higher child‐dog relationship quality. For this sample, Cronbach's α = .79.

3.1.3. NRI: Pet Provisions of Support (PPS) version

Child‐dog relationship quality was further assessed using the Pet Provisions of Support (PPS) Inventory which uses a subset of items from the NRI to assess pet relationship quality (Bryant & Donnellan, 2007). Children rate 12 items about themselves and their pet dog using a 5‐point scale (1 = little or none to 5 = the most). Items assess four social provisions (three items each): self‐enhancing admiration (e.g., “How much does your dog make you feel good about yourself?”), affection (e.g., “How much does this pet love or like you?”), nurturance (e.g., “How much do you take care of your pet dog?”), and companionship (e.g., “How much free time do you spend with your dog?”). We combined these scales to assess average overall child‐dog relationship quality scale (Cronbach's α = .86 for this sample) as reliability for the individual scales was modest in this sample (Cronbach's α’s = .66, .68, .59, .53, respectively), and the scales were all correlated with one another. Higher scores on this overall quality scale indicate higher child‐dog relationship quality.

3.2. Daily log measures of the child‐dog relationship (Appendix C)

The questionnaire measures assessed children's and parents’ overall perceptions of children's relationships with their pet dogs. We wanted to supplement these measures by obtaining children's daily reports of experiences with pets, as these might be less susceptible to self‐report biases or memory distortions. The quality of children's relationships with their pet dog was assessed using the newly developed What Did You and Your Dog Do Today measure (Appendix C). This measure contains two types of child‐pet relationship reports: (1) the child's daily rating of the quality of interactions with their pet dog; and (2) the child's daily report of their behavioral interactions with their pet dog.

3.2.1. Daily log: Pet relationship quality ratings

The relationship quality ratings ask children to respond to six statements about how they felt when they were with their dog that day. These statements correspond with the six relationship quality scales found on the Pet Dog Relationship Inventory, though these items differ in that they ask children to reflect on their experiences that day (e.g., “TODAY, when I was with my dog: I felt very close to my dog”). Items are rated on a 5‐point scale, from 1 = almost never, to 5 = almost always. The six quality scale scores were derived by averaging the participants’ respective scores for each scale across the 7 days. Daily quality scores were calculated for all participants who provided a report of that quality on at least 5 of the 7 days (n = 100 children). Cronbach's alphas were calculated separately for each quality scale and are listed in Table 1.

3.2.2. Daily log: Pet relationship behavioral ratings

The behavioral report asks children to respond to 12 statements regarding behavioral interactions with their dog that day. These statements correspond with six behavioral scales (two items per scale): (1) Affection (e.g., “Spent time petting your dog”); (2) Nurturance of Pet (e.g., “Fed your dog”); (3) Emotional Support from Pet (e.g., “Felt your dog understood how you felt”); (4) Companionship (e.g., “Played with your dog”); (5) Friction with Pet (e.g., “Got mad at my dog”); and (6) Pet as Substitute for People (e.g., “Felt closer to your dog than anyone else”). Children were asked to indicate whether they did or did not do these behaviors that day; 0 = No to 1 = Yes. The six behavioral scale scores were derived by averaging participants’ scores on the two respective items for each scale across the seven days. Scale scores were calculated for all participants who, across the seven days, completed at least 70% of the items (n = 100 children). Cronbach's alphas were calculated separately for each behavioral scale and are listed in Table 1.

3.3. Data analysis plan and data transparency

Data analyses proceeded in five steps. First, we examined basic descriptive information for child reports of all of the pet relationship scales (means, standard deviations, Cronbach's alphas). We also conducted CFA analyses for the child questionnaire to test how well items loaded on to each of the scales. Second, we examined correlations among the six pet relationship qualities as assessed via child and parent questionnaires. Third, we examined the correlations among the six pet relationship qualities as assessed via the daily logs. Fourth, we examined whether the pet relationship qualities as assessed by child and parent questionnaires were associated with the child's daily log reports of pet relationship quality using multilevel modeling. Finally, we examined how the six pet relationship qualities, as assessed by questionnaires and logs, were related to relationship quality as assessed with the LAPS and NRI scores.

The data set (in SPSS), syntax files, and a code book of the variables can be accessed through the Open Science Framework site: https://osf.io/j4s8f/.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Descriptive information for new pet relationship measures

Means and standard deviations for all child measures of pet dog relationship quality are shown in Table 1. As expected, children's reports of pet relationship quality tended to be positive. On the child questionnaire, ratings were especially high for Affection, followed by Nurturance, Emotional Support from the Pet, and Companionship. Ratings for Pet as Substitutes for People was lower, and the lowest ratings were for Friction with Pet. The behavioral ratings from the daily log showed the same pattern, except that Companionship was reported relatively more often than was Nurturance or Emotional Support. The behavioral ratings revealed that children engaged in affectionate interactions with pets daily, and that they engaged in companionship and nurturing activities on most days. Children sought out pets for emotional support or in place of people on about half the days. Reports of friction with pet dogs was relatively rare. A similar pattern was reflected on daily log global ratings, although interestingly the mean for Affection was lower than when this quality was reported via global questionnaire.

Table 1 also includes the Cronbach's alphas for all of the scales. Alphas were adequate to very good, .70–.95, except for the lower alpha for Affection as assessed by the child questionnaire (.61). The lower alpha might be due to the restricted range for this variable (all children rated the pet dog relationship high on this variable; range 3.20–5.00). Alphas based on the daily log behavior reports and ratings were consistently very good (.78 or higher).

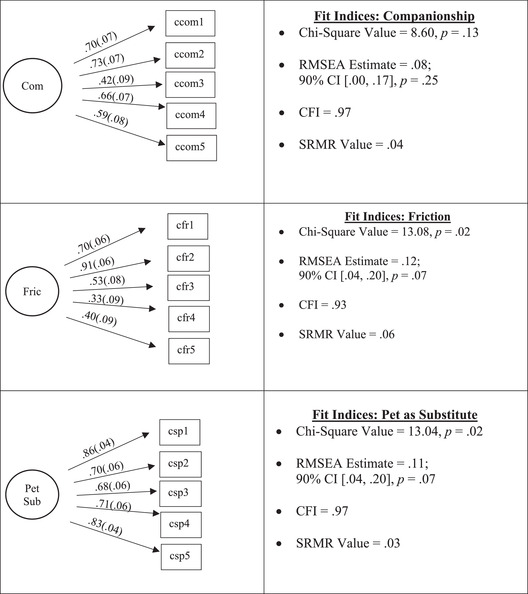

We also evaluated the structure of the six scales from the child questionnaire using the software MPlus (version 8.5; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2022) to conduct a CFA. Due to our sample size, we evaluated each scale separately (see Figure 1). To test model fit for each scale, we examined four indicators. First, we examined χ2 which, when not significant, indicates that sample and the model‐implied variances and covariances do not differ (i.e., the model fits the data well; Brown & Moore, 2012). Then, we examined the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the comparative fit index (CFI) with the following cut off criteria to determine acceptable fit (Kline, 2016): (1) SRMR values < .10; (2) RMSEA values ≤ .08; and (3) CFI ≥ .90. The majority of the fit indices for the Affection, Nurturance of Pet, Emotional Support from Pet, and Companionship scales indicated that the single factor model fit the data well (see Figure 1). Conclusions regarding model fit were more mixed for the Friction and Pet at Substitute scales with χ2 and RMSEA indicating poor fit, and CFI and SRMR indicating acceptable fit (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Confirmatory factor analyses for six qualities of pet dog relationships. Note. Aff = Affection; Nur = Nurturance of Pet; Emot Sup = Emotional Support from Pet; Com = Companionship; Fric = Friction with Pet; Pet Sub = Pet as Substitute. Values in figures represent standardized loadings (and standard errors).

Modification indices were examined for each of the six scales; these indices suggested one item could be dropped for the Affection, Emotional Support from Pet, and Friction scales due to some evidence of redundancy among the indicators (items). Given, however, that this is the first test of this measure, and it is not yet cross‐validated, we retained all items for further analyses.

4.2. Associations among scales from the questionnaire measures of pet dog relationship quality

We next sought to determine the distinctiveness of the six pet relationship qualities as assessed with the questionnaire. Table 2 displays correlations among the child ratings of the six qualities above the diagonal, correlations among the parent ratings of the six qualities below the diagonal, and correlations between child and parent reports for each of the qualities on the diagonal.

TABLE 2.

Correlations within and between pet dog relationship inventory: Child and parent report

| Child report | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent report | Affection | Nurturance to Pet | Emotional support from pet | Companionship | Friction with Pet | Pet as substitute for people |

| Affection | .23 * | .53*** | .34*** | .51*** | −.11 | .23* |

| Nurturance of pet | .50*** | .35 *** | .37*** | .55*** | −.09 | .20* |

| Emotional support from pet | .67*** | .58*** | .21 * | .42*** | −.11 | .29** |

| Companionship | .66*** | .50*** | .67*** | .27 ** | .02 | .15 |

| Friction with pet | −.41*** | −.27** | −.28** | −.27*** | .27 ** | −.05 |

| Pet as substitute for people | .50*** | .34*** | .57*** | .65*** | −.20* | .28 ** |

Note. Child correlations above diagonal (N = 113–114). Parent correlations below diagonal (N = 115). Parent‐child correlations on diagonal. *** p < .001. ** p < .01. * p ≤.05.

Correlations among the child reports revealed that three of the qualities – Affection, Nurturance, and Companionship – all showed large, positive associations with one another (rs > .50). Emotional Support was moderately related to all of these qualities (rs = .34 to .42). Friction with pet was not related to any of the other relationship qualities, and Pets as Substitutes for People was related weakly but significantly and positively with Affection, r = .23, Nurturance, r = .20, and Emotional Support, r = .29. By contrast, parent reports showed significant associations among all of the scales, and the magnitude of correlations tended to be higher than those found for child report of these same qualities. Thus, child ratings were more distinct, whereas parent ratings appeared to capture a more global judgement about the pet relationship quality. These interpretations were supported by the results of principal component analyses conducted with the scale scores. For the child questionnaire, we conducted a PCA (criterion of eigenvalue of 1.0 or greater) with an obliminal rotation, which yielded a two factor solution: the first factor included all but Friction and explained 42% of the variance, and the second factor, with a high loading only for Friction, explained an additional 17% of the variance (see Supplementary Table S1). By contrast, an analogous PCA of the parent questionnaire revealed only a single factor that accounted for 57% of the variance; factor loadings for the single unrotated factor based on parent questionnaire were: Affection, .81; Nurturance, .62; Emotional Support, .84; Companionship, .83; Friction with Pet, ‐.38; Pets as Substitutes for People, .67.

Table 2 (on the diagonal) also displays the correlations between child and parent reports of a specific relationship quality. Correlations were small but significant (rs .21 to .35) for all of the six qualities, providing some evidence for the validity of the child questionnaire. As shown in Supplementary Table S2, by comparison few of the cross‐construct, cross‐informant correlations were significant.

4.3. Associations among the scales from the daily log measures of pet dog relationship quality

Table 3 displays correlations among the Behavior reports and Relationship Quality ratings from the Daily Logs. The correlations among the behavior reports of the qualities (above diagonal) show that Friction and Nurturance were not correlated with the other qualities. The remaining qualities were related to one another, with the strongest associations between Affection and Companionship, r = .53 and between Emotional Support and Pets as Substitutes, r = .54. A PCA (see Supplementary Table S1) conducted with the scale scores revealed a two factor solution that accounted for 37% of the variance in the behavior ratings. Affection, Emotional Support, Companionship, and Pets as Substitutes for People loaded on the first factor, and Nurturance and Friction with Pet loaded on the second factor; the latter suggests that friction with a pet may arise in the context of daily care.

TABLE 3.

Correlations between the daily log pet relationship quality ratings and the daily log behavioral report: Child report

| Daily log: Pet relationship behavioral report | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily log: Quality ratings | Affection | Nurturance of pet | Emotional support from pet | Companionship | Friction with pet | Pet as substitute for people |

| Affection | .49 *** | .16 | .29** | .53*** | .05 | .23* |

| Nurturance of pet | .64*** | .51 *** | .04 | .17 | .09 | .19 |

| Emotional support from pet | .79*** | .61*** | .46 *** | .37*** | −.06 | .54*** |

| Companionship | .72*** | .63*** | .65*** | .50 *** | −.06 | .30** |

| Friction with pet | −.02 | .01 | −.001 | .01 | .58 *** | −.09 |

| Pet as substitute for people | .43*** | .36*** | .42*** | .47*** | −.06 | .71 *** |

Note. Quality rating correlations below diagonal. Behavioral report correlations above diagonal. Quality rating‐behavioral report correlations on diagonal. N = 100. *** p < .001. ** p < .01. * p < .05.

For the daily Relationship Quality ratings, Friction was not related to any of the other qualities, and the rest of the qualities were all significantly related to one another, with rs .36 ‐ .79. As shown in Supplementary Table S1, a PCA performed with the scale scores revealed a two‐factor solution that was similar to the results for the child global questionnaire ratings (55% of variance explained); the first factor included all scales except Friction, which was the sole scale to load on the second factor.

Finally, we examined convergence between the two daily log reports of relationship quality. The six qualities, as assessed with the two methods in the daily log, were highly related to one another (see values on diagonal of Table 3); correlations ranged from .46 to .71 and tended to be higher than the cross‐measure, construct correlations (see Supplementary Table S3).

4.4. Do relationship ratings from the pet relationship questionnaire predict children's daily experiences with pets?

We next tested whether children's reports from the pet dog relationship questionnaire were related to their reports of daily experiences with their pet dog. To account for the nested nature of the daily report data, we used multilevel modeling (MLM) day‐within‐person analyses in HLM 8.0 (Raudenbush et al., 2019). For each relationship rating, we analyzed two models, a null model and a grand mean centered level 2 predictor model. Given that the analytic procedure is the same for each model, we describe the procedure using Affection as an example. First, we examined a null model with the log rating of Affection as the dependent variable and no predictors:

We used the variance components produced by this analysis to calculate the intra‐class coefficient (ICC), which allows for the examination of the percentage of daily Affection that is attributed to differences between individuals:

The ICC value for this model indicates that 19.17% of the total variability in Affection (quality rating) is at level 2 (attributed to differences between persons) and the remaining variability is at level 1 (the day level).

Next, we ran a model with one grand‐mean centered predictor, Affection (from the pet relationship questionnaire), predicting the intercept of daily Affection (from log quality ratings):

The final estimation of fixed effects of the intercept of daily Affection yields an unstandardized coefficient that represents the relationship between the Affection quality rating from the pet relationship questionnaire and mean daily Affection. In this case, the coefficient of .72 is significantly different from zero. The t‐ratio is 4.47, which is significant at the p<.001 level. All told, these results indicate that for every one‐unit increase in the affection quality rating from the pet relationship questionnaire, daily Affection increased by .72, indicating that Affection quality reports from the pet relationship questionnaire predict daily Affection quality experiences.

In sum, across the multilevel models analyzed, we found that the null model ICCs ranged between 0 and .1917, which shows that between 0 and 19.17% of the variation in each respective relationship rating scale is attributable to differences between individuals. In addition, the level 2 predictor models showed that all of the qualities from the questionnaire, except Friction, were related to that same quality as assessed with the daily behavior reports (see Table 4 for all level 2 predictor model coefficients). We provide the correlations based on aggregated scores for each quality in Supplementary Table 4 to show effect sizes; significant rs were .33 to .52. In addition, further level 2 predictor models showed that all of the qualities as assessed by the child questionnaire were related to those same qualities as assessed with the daily ratings of those same qualities (rs were .29 to .66 for aggregated daily reports; see Supplementary Table S4).

TABLE 4.

MLM level 2 predictor model results examining whether pet dog relationship inventory child and parent reports predict the child's daily behavioral reports and daily pet relationship quality ratings

| Daily logs: Behavioral report | Daily logs: Pet relationship quality ratings | |

|---|---|---|

| Pet dog relationship inventory: Child report | ||

| Affection | .11*** | .72*** |

| Nurturance of pet | .17*** | .78*** |

| Emotional support from pet | .17*** | .30*** |

| Companionship | .11*** | .59*** |

| Friction with pet | .02 | .28** |

| Pet as sub | .18*** | .75*** |

| Pet dog relationship inventory: Parent report | ||

| Affection | .09*** | .33*** |

| Nurturance of pet | .13*** | .51*** |

| Emotional support from pet | .04 | .16 |

| Companionship | .07* | .29** |

| Friction with pet | .05 | .26* |

| Pet as sub | .04 | .33** |

Note. *** p < .001. ** p < .01. * p < .05. Values for daily log variables reflect unstandardized coefficients that represent the relationship between child and parent ratings for each scale of the pet dog relationship inventory and the child's mean daily behavioral or quality report of that same scale.

Analogous MLM analyses of the parent questionnaire report of the pet dog relationship showed the reports were also significantly related to child daily reports for five of the qualities: Affection, Nurturance, Companionship, Friction, and Pets as Substitutes (the latter two only for daily quality ratings but not behavioral ratings). Parent report was not related to daily measures of Emotional Support (see Table 4; see also Supplementary Table S4 for correlations based on aggregated log ratings).

4.5. Pet relationship qualities: Associations with the LAPS and NRI

Our last question was how the new measures of pet dog relationship quality would converge with other measures of pet relationship quality. For these analyses, we examined how each of the pet relationship qualities (assessed via questionnaire, log behavior reports, and log ratings) were related to overall scores on the LAPS and the PPS version of the NRI. As shown in Table 5, the LAPS showed at least some associations with all of the pet relationship qualities except Friction. The LAPS was most consistently and strongly related to Pets as Substitutes for People, Emotional Support, and Companionship. The NRI also was related to all of the qualities except Friction. It was related most consistently to Pets as Substitutes and Emotional Support. The NRI Positive Qualities scale was also related to Nurturance and Companionship ratings, but not to the behavior reports of these qualities from the daily logs (see Supplementary Table S5 for correlations of individual NRI subscales).

TABLE 5.

Correlations between the child reported pet dog relationship inventory, the daily log ratings, and the other pet measures

| LAPS ‐ Overall | PPS version of NRI ‐ Overall | |

|---|---|---|

| Affection | ||

| PDRI | .23* | .37*** |

| Daily behavioral report | .20* | .21* |

| Daily quality rating | .16 | .38*** |

| Nurturance of pet | ||

| PDRI | .31** | .37*** |

| Daily behavioral report | .08 | .16 |

| Daily quality rating | .22* | .32** |

| Emotional support from pet | ||

| PDRI | .62*** | .41*** |

| Daily behavioral report | .33** | .37*** |

| Daily quality rating | .19 | .37*** |

| Companionship | ||

| PDRI | .33*** | .40*** |

| Daily behavioral report | .27** | .18 |

| Daily quality rating | .19* | .39*** |

| Friction with pet | ||

| PDRI | −.10 | −.09 |

| Daily behavioral report | −.08 | −.18 |

| Daily quality rating | −.06 | −.12 |

| Pet as substitute for people | ||

| PDRI | .52*** | .45*** |

| Daily behavioral report | .38*** | .44*** |

| Daily quality rating | .45*** | .40*** |

Note. PDRI = Pet Dog Relationship Inventory. N's = 113–114 (PDRI); 100 (Daily Behavioral Report); 100 (Daily Quality Rating). *** p < .001. ** p < .01. * p ≤ .05.

5. DISCUSSION

The aim of our study was to develop a set of measures for children in middle childhood to provide assessments of the qualities of children's relationships with pet dogs. We developed measures to assess six specific relationship qualities that were identified from a literature review: affection, nurturance of pet, emotional support from pet, companionship, friction with pet, and pet as substitute for people. Our multi‐method approach included child questionnaires, parent questionnaires, and child daily reports of experiences with their pet dogs. Overall, the measures provided reliable indices of the pet relationship qualities, and the convergence across different assessment approaches provides initial evidence for the validity of the measures. Correlations suggested that affection, nurturance, emotional support, and companionship tended to be strongly associated with one another, and these qualities were also moderately related to pet as substitutes for people. Especially in the child self‐reports, the negative quality of friction with pets was distinct from the positive qualities. An advantage of these new measures is that they assess a broader set of qualities than available measures (e.g., pets as substitutes is not included on the NRI, and the LAPS does not assess negative interactions with pets). In addition, we demonstrated that the child questionnaire is related to both parent perceptions of the relationship as well as to reports of daily interactions with pets. The diary measure is innovative and may be an important alternative to child questionnaires as daily reports tend to be less influenced by self‐report biases.

Theoretical frameworks regarding the importance of relationships with pets have tended to emphasize that these relationships are a source of positive interactions that can fulfill human needs for affection, emotional support, and companionship (Mueller, 2014; Walsh, 2009). These same qualities have also been identified as key features of children's friendships (Newcomb & Bagwell, 1995). Children view pets as friends (Davis and Juhasz, 1995), and our findings suggest that these three qualities are highly characteristic of children's relationships with their pet dogs and tend to co‐occur. These qualities also, for the most part, were strongly related to providing nurturance to a pet. We sought to develop a measure that would assess specific relationship qualities but also wanted to determine their distinctiveness. Our findings suggest that the positive qualities in pet dog relationships tend to co‐occur, and therefore it may be sufficient in many research contexts to assess positive pet dog relationship quality as a single dimension, as has been done in prior studies of pets and pet dog relationship quality (e.g., Bures et al., 2019; Hall et al., 2016; Mueller & Callina, 2014; Westgarth et al., 2013). Nevertheless, there may be occasions when the assessment of specific qualities would provide a more refined test of the potential impact of pet dog relationships. For example, assessment of specific qualities is necessary to test whether opportunities to take care of pets (i.e., nurturance of pet) promotes empathy in children (Melson, 2003). In addition, it may be that some qualities are more important for children's well‐being, and testing this idea would require measures that allow for distinguishing between different positive relationship qualities (e.g., companionship with a pet might mitigate feelings of loneliness).

We were unsure at the outset how to view the quality of pets as substitutes for people: is high reliance on pet dogs, in place of humans, a sign of close pet attachment as conceptualized in the Lexington Attachment Scale (Johnson et al., 1992)? Or, as suggested in research with children, is stronger reliance on nonparental figures (e.g., peers, pets) potentially a problematic indicator of the relationship, given that children in middle childhood would be expected to rely most prominently on parents to fulfill needs for comfort (Kerns & Brumariu, 2016)? In this study, we sought to determine how this quality was related to other pet dog relationship qualities. We found that viewing one's pet as a substitute for people (i.e., preferring support from the pet) tended to be associated with other positive pet relationship qualities, suggesting that children who are heavily relying on pets for support tend to view these relationships as generally supportive. We note, however, that the correlations are more moderate for this quality than for the other positive relationship qualities. The daily reports suggest that on those days when children viewed pets as preferred partners over people, they also sought out their pet for support. Studies of network support suggest that children typically rely less on pet dogs for support, instead favoring human partners (McNicholas & Collis, 2000). It might be that for most children, pet dogs are ancillary supports who children may rely on when support from humans is not available (e.g., parent is absent or occupied, friend is not available). Studies of children's social networks rarely consider pets as potential providers of support (see McNicholas & Collis, 2000, for an exception), and thus additional research is needed to understand when and why children turn to pets for support (e.g., may depend on availability of human partners or the quality of those relationships).

For the most part, children's reports of friction with the pet dog were not related to positive qualities in the pet dog relationship. This finding is reminiscent of studies showing that positive and negative qualities in children's friendships tend to be distinct (Berndt & McCandless, 2009). One exception to this pattern is that, in reports of daily interactions, children's reports of nurturance and friction with the pet tended to load positively together. It may be that taking care of one's pet is often the context in which children have negative experiences with the pet (e.g., have to enforce house rules, clean up after pet). Studies of pet dog relationship quality have tended to focus on positive relationship qualities, and negative pet dog relationship qualities are rarely assessed (see Kertes et al., 2018, for an exception). Challenging interactions with pets may provide some opportunities for growth (e.g., learning how to consistently apply rules, to regulate emotions), or they may have negative impacts (e.g., lead to negative mood, which in turn impacts child motivation or quality of interactions with human partners). An important direction for future research is to investigate further how children are impacted by the negative interactions they have with their pets.

A major goal of the study was to develop a set of measures, using different methods, that could assess pet dog relationship quality. In this preliminary test of the measures, we found that all of the measurement approaches allowed for the reliable assessment of the specific relationship qualities as evaluated by the internal consistency of scales. CFA analyses, conducted to examine the structure of each scale from the child questionnaire, mostly supported the hypothesized scale structures, although a few items were identified that were not as strong of indicators of a particular construct. It should be noted that our sample size precluded a test of all individual items from all scales in a single CFA analysis. Thus, our findings, while promising, are a first step in validating the factor structure of the child PDRI, and there is a need to test in a CFA analysis the full structure of all items and scales in a larger sample.

In addition, we found convergence across methods in the assessment of the pet dog relationship qualities. Specifically, children's global questionnaire ratings of the qualities were related to parent reports of the same qualities. In addition, the global questionnaire ratings were also related to child daily reports of the qualities as assessed through daily ratings and behavioral reports, except for daily behavioral reports of friction with pets. Parent questionnaire reports were also related to child daily reports, although parent reports of Emotional Support from the pet were not associated with child reports from the daily interactions; perhaps parents have a general sense of the relationship but are less aware of specific instances when children are seeking out pet dogs for emotional support. Interestingly, in parent questionnaire reports, all of the qualities including friction loaded on a single factor, and correlations among the qualities were typically higher than for child report, suggesting that parents may hold somewhat undifferentiated views of their child's relationships with a pet dog. It might be that parents form a general impression of the relationship, which then colors how they view the specific qualities. Children in middle childhood tend to be concrete thinkers, which may actually contribute to them responding in a more specific way when questioned about different qualities. Regardless of the reason, the different pattern of findings for parents and children's reports underscores the importance of obtaining reports of pet dog relationship quality directly from children.

Although results from this study are promising, there are limitations of the study. The measures were tested in a single, predominantly White sample. Given that pet ownership rates vary across ethnic groups (Owen et al., 2010), and pet relationship quality may also vary, it will be important to test the measures in samples that have greater racial and ethnic diversity. Although our sample size provided adequate power for our analyses, larger samples would also allow for testing whether subgroups differ (e.g., are reports from boys and girls similar in their structure). Daily reports were obtained for 1 week, and rates of negative interactions with pets were low. For studies that focus on children's negative interactions with pets, a longer sampling (e.g., 2 weeks) might be needed to obtain sufficient variability in reports given that negative interactions with pets may occur only sporadically. Finally, although we showed convergence across methods, another way to validate the measures would be to examine how they are associated with children's interactions with pets.

This study shows that pet dog relationship qualities can be reliably measured. Future studies could examine which of these qualities are related to children's well‐being. Especially needed are studies that examine pet dog relationships along with children's other close relationships (e.g., parents, friends), so that the relative importance of pet dog relationships for mental health and social competence can be evaluated (Kerns et al., 2017). Finally, the lack of well validated measures of pet relationship quality have hindered the scientific study of HAI (Esposito et al., 2011; Mueller, 2014). The development of measures is important so that they can be included in large scale and longitudinal studies of child development as these provide an excellent opportunity to examine the importance of pets (Cassels et al., 2017; Esposito et al., 2011). It is likely that the measure could be used to describe children's relationships with other types of common pets (e.g., cats), although this would need to be explicitly tested.

In conclusion, the growing field of HAI research has been documenting the ways in which animals contribute to children's development (Mueller, 2014). The present study provides an initial test of a new set of multi‐method tools that can be used to describe the quality of children's relationships with pet dogs. Future research could build on current findings by considering how both positive and negative interactions with dogs and other pets contribute to children's social and emotional development and by considering the role of pets in the context of children's human relationships.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose

Supporting information

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

TablesS1‐S5

Kerns, K. A. , Dulmen, M. H. M. , Kochendorfer, L. B. , Obeldobel, C. A. , Gastelle, M. , & Horowitz, A. (2023). Assessing children's relationships with pet dogs: A multi‐method approach. Social Development, 32, 98–116. 10.1111/sode.12622

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data, data analysis coding, and research materials are available by emailing the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- Ainsworth, M. S. (1989). Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist, 44(4), 709–716. 10.1037/0003-066X.44.4.709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt, T. J. , & McCandless, M. A. (2009). Methods for investigating children's relationships with friends. In Rubin K. H., Bukowski W. M., & Laursen B. (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 63–81). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. A. , & Moore, M. T. (2012). Confirmatory factor analysis. In Hoyle R. H. (Ed.), Handbook of structural equation modeling (pp. 361–379). Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, B. K. (1990). The richness of the child‐pet relationship: A consideration of both benefits and costs to children. Anthrozoös, 3(4), 253–261. 10.2752/089279390787057469 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, B. K. , & Donnellan, B. M. (2007). The relation between socio‐economic status concerns and angry peer conflict resolution is moderated by pet provisions of support. Anthrozoös, 20(3), 213–223. 10.2752/089279307X224764 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bures, R. M. , Mueller, M. K. , & Gee, N. R. (2019). Measuring human‐animal attachment in a large U.S. survey: Two brief measures for children and their primary caregivers. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 1–5. 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassels, M. T. , White, N. , Gee, N. , & Hughes, C. (2017). One of the family? Measuring young adolescents’ relationships with pets and siblings. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 49, 12–20. 10.1016/j.appdev.2017.01003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, C. T. , & Johnston, C. (2002). Developmental differences in children's use of rating scales. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 27(1), 27–36. 10.1093/jos/9.1.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaraman, L. , Mueller, M. K. , & Richer, A. M. (2020). The role of pet companionship in online and offline social interactions in adolescence. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 37, 589–599. 10.1007/s10560-020-00707-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collis, G. M. , & McNicholas, J. , (1998). A theoretical basis for health benefits of pet ownership, attachment versus psychological support. In Wilson C. C. & Turner D. C. (Eds.), Companion animals in human health (pp. 105–134). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Covert, A. M. , Whiren, A. P. , Keith, J. , & Nelson, C. (1985). Pets, early adolescents, and families. Marriage and Family Review, 8(3‐4), 95–108. 10.1300/J002v08n03_08 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J. H. , & Juhasz, A. M. (1995). The preadolescent/pet friendship bond. Anthrozoös, 8, 78–82. 10.2752/089279395787156437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, L. , McCune, S. , Griffin, J. A. , & Maholmes, V. (2011). Directions in human‐animal interaction research: Child development, health, and therapeutic interventions. Child Development Perspectives, 5(3), 205–211. 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00175.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Furman, W. , & Buhrmester, D. (1985). Children's perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology, 21(6), 1016–1024. 10.1037/0012-1649.21.6.1016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guerney, L. F. (1991). A survey of self‐supports and social supports of self‐care children. Elementary School Guidance and Counseling, 25(4), 243–254. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42868971 [Google Scholar]

- Hall, N. J. , Liu, J. , Kertes, D. A. , & Wynne, C. D. L. (2016). Behavioral and self‐report measures influencing children's reported attachment to their dog. Anthrozoös, 29(1), 137–150. 10.1080/08927936.2015.1088683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, K. B. (2014). Development and human‐animal interaction. Human Development, 57, 30–34. 10.1159/000357795 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jalongo, M. R. (2015). An attachment perspective on the child‐dog bond: Interdisciplinary and international research findings. Early Childhood Education Journal, 43, 395–405. 10.1007/s10643-015-0687-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, T. P. , Garrity, T. F. , & Stallones, L. (1992). Psychometric evaluation of the Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale (LAPS). Anthrozoös, 5(3), 160–175. 10.2752/089279392787011395 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns, K. A. , & Brumariu, L. E. (2016). Attachment in middle childhood. In Cassidy J. & Shaver P. (Eds), Handbook of attachment (3rd ed., pp. 349–365). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Kerns, K. A. , Koehn, A. J. , van Dulmen, M. H. M. , Stuart‐Parrigon, K. L. , & Coifman, K. G. (2017). Preadolescents’ relationships with pet dogs: Relationship continuity and associations with adjustment. Applied Developmental Science, 21(1), 67–80. 10.1080/10888691.2016.1160781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertes, D. A. , Hall, N. , & Bhatt, S. A. (2018). Children's relationships with their pet dogs and OXTR genotype predict child‐pet interaction in an experimental setting. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1–9. 10.3389/fpsych.2018.01472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertes, D. A. , Liu, J. , Hall, N. J. , Hadad, N. A. , Wynne, C. D. L. , & Bhatt, S. S. (2017). Effect of pet dogs on children's perceived stress and cortisol stress response. Social Development, 26(2), 382–401. 10.1111/sode.12203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden Ellsworth, L. , Keen, H. A. , Mills, P. E. , Newman, J. , Martin, F. , & Newberry, R. C. (2017). Role of 4‐H dog programs in life skills development. Anthrozoös, 30(1), 91–108. 10.1080/08927936.2017.1270596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McNicholas, J. , & Collis, G. M. (2000). Children's representation of pets in their social networks. Child: Care, Health, and Development, 27(3), 279–294. 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2001.00202.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melson, G. F. (2003). Child development and the human‐companion animal bond. American Behavioral Scientists, 47(1), 31–39. 10.1177/0002764203255210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, V. (1998). My animals and other family: Children's perspectives on their relationships with companion animals. Anthrozoös, 11(4), 218–226. 10.2752/089279398787000526 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, M. K. (2014). Human‐animal interaction as a context for positive youth development: A relational developmental systems approach to constructing human‐animal interaction theory and research. Human Development, 57, 5–25. 10.1159/000356914 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, M. K. , & Callina, K. S. (2014). Human‐animal interaction as a context for thriving and coping in military‐connected youth: The role of pets during deployment. Applied Developmental Science, 18(4), 214–223. 10.1080/10888691.2014.955612 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L. K. , & Muthén, B. O. (1998‐2022) Mplus (Version 8.5). Los Angeles, CA: Authors. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb, A. F. , & Bagwell, C. L. (1995). Children's friendship relations: A meta‐analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 117(2), 306–347. 10.1037/0033-2909.117.2.306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Owen, C. G. , Nightingale, C. M. , Rudnicka, A. R. , Ekelund, U. , McMinn, A. M. , van Sluijs, E. F. , Griffin, S. J. , Cook, D. G. , & Whincup, P. H. (2010). Family dog ownership and levels of physical activity in childhood: Findings from the Child Heart and Health Study in England. American Journal of Public Health, 100(9), 1669–1671. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.188193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush, S. W. , Bryk, A. S. , Cheong, Y. F. , & Congdon, R. (2019). HLM 8 for Windows [Computer Software]. Skokie, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X. , Updegraff, K. A. , McHale, S. M. , Hochgraf, A. K. , Gallagher, A. M. , & Umaña‐Taylor, A. J. (2021). Implications of COVID‐19 school closures for sibling dynamics among US Latinx children: A prospective, daily diary study. Developmental Psychology, 57(10), 1708–1718. 10.1037/dev0001196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taber, S. M. (2010). The veridicality of children's reports of parenting: A review of factors contributing to parent–child discrepancies. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(8), 999–1010. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, F. (2009). Human‐animal bonds II: The role of pets in family systems and family therapy. Family Process, 48(4), 462–480. 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01297.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westgarth, C. , Boddy, L. M. , Stratton, G. , German, A. J. , Gaskell, R. M. , Coyne, K. P. , Bundred, P. , McCune, S. , & Dawson, S. (2013). Pet ownership, dog types, and attachment to pets in 9–10 year old children in Liverpool, UK. BMC Veterinary Research, 9, 1–10. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1746‐6148/9/102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, C. C. , & Netting, F. E. (2012). The status of instrument development in the human‐animal interaction field. Anthrozoös, 25(3), s11–s55. 10.2752/175303712X13353430376977 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

TablesS1‐S5

Data Availability Statement

All data, data analysis coding, and research materials are available by emailing the corresponding author.