Abstract

Background

There is a dearth of evidence on the relationship between COVID-19 and metabolic conditions among the general U.S. population. We examined the prevalence and association of metabolic conditions with health and sociodemographic factors before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Data were drawn from the 2019 (N = 5,359) and 2020 (N = 3,830) Health Information National Trends Surveys on adults to compare observations before (2019) and during (2020) the COVID-19 pandemic. We conducted weighted descriptive and multivariable logistic regression analyses to assess the study objective.

Results

During the pandemic, compared to pre-pandemic, the prevalence of diabetes (18.10% vs. 17.28%) has increased, while the prevalence of hypertension (36.38% vs. 36.36%) and obesity (34.68% vs. 34.18%) has remained similar. In general, the prevalence of metabolic conditions was higher during the pandemic (56.09%) compared to pre-pandemic (54.96%). Compared to never smokers, former smokers had higher odds of metabolic conditions (AOR = 1.38, 95% CI = 1.01, 1.87 and AOR = 1.57, 95% CI = 1.10, 2.25) before and during the pandemic, respectively. People with mild anxiety/depression symptoms (before: AOR = 1.52, 95% CI = 1.06, 2.19 and during: AOR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.01, 2.38) had higher odds of metabolic conditions relative to those with no anxiety/depression symptoms.

Conclusion

This study found increased odds of metabolic conditions among certain subgroups of US adults during the pandemic. We recommend further studies and proper allocation of public health resources to address these conditions.

Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 (Coronavirus diseases; COVID-19) has continued to affect many countries, including the United States, since the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a global pandemic in March 2020 [1, 2]. Before the declaration, metabolic conditions such as obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease have continued to be the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the U.S. and the world [3–5]. In 2018, approximately 13% of all U.S. adults had diabetes, with 2.8% of this population being unaware of their status but meeting laboratory criteria for diabetes [6]. Similarly, a national survey from 2017 to 2018 shows that 42.4% of U.S. adults had obesity [7]. These metabolic conditions are associated with severe health risks [8, 9]. Additionally, they predispose people to the risks of death and adverse health outcomes from COVID-19 [8–13]. However, studies on the effects of COVID-19 on these metabolic conditions are scarce. Indeed, the associations between cardiometabolic conditions in U.S. adults and the COVID-19 pandemic and risk factors such as physical inactivity, tobacco use, anxiety/depression, and sociodemographic characteristics remain understudied.

Not only did patients with diabetes or obesity have increased mortality due to COVID-19 infection [14–20], their overall health was also negatively impacted by the COVID-19 lockdown [17, 19]. Studies demonstrated poor glycemic control and increased body mass index (BMI) for patients with diabetes during the lockdown [20, 21] along with a deterioration in glucose regulation [16, 22]. The timings of lockdown orders in the target populations from these studies differ, as they were based on when the countries declared a lockdown [16, 20–22]. Other studies have shown that newly diagnosed diabetes is more prevalent in patients following COVID-19 infection, with one in every ten COVID-19 patients diagnosed with new onset diabetes mellitus [15, 23]. In addition to metabolic health outcomes secondary to diabetes, some subgroups, specifically those with cardiometabolic disease [24], were at an increased risk of poor mental health outcomes, had depressive symptoms [25], and poor sleep quality [26]. Other negative behavioral activities included reduced physical activity [27, 28] and increased alcohol consumption [26].

While the metabolic conditions such as diabetes and obesity are well documented, there is a paucity of research on the association between conditions such as hypertension and COVID-19 [29]. Given the high prevalence of medical conditions such as hypertension and the potential for negative health outcomes secondary to COVID-19, this study explores the relationships between COVID-19 and metabolic conditions before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

We utilize a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults to estimate the prevalence of metabolic conditions (diabetes, hypertension, and obesity) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic declaration. Further, this study examines the association between these metabolic conditions among U.S. adults and the ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic, including physical inactivity, tobacco use, anxiety/depression, and sociodemographic characteristics. Considering the higher prevalence of these metabolic conditions in the U.S. adult population and throughout the world, it is imperative to understand which populations to target for public health interventions to decrease COVID-19 related morbidities for high-risk populations.

Methods

The 2019 and 2020 Health Information National Trends Surveys (HINTSs) de-identified public-use datasets were combined for this study. HINTS is a cross-sectional survey that assesses health-related information (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, and obesity) and behaviors (e.g., tobacco use) among a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults aged ≥18 years. It uses a random sampling technique to select a sample of the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized adult population. Details of the methods, questionnaire, and survey administration have been published [30, 31]. The 2019 survey (HINTS 5 Cycle 3) was conducted from January through April 2019, and the 2020 survey (HINTS 5 Cycle 4) was conducted from February through June 2020. These surveys are the recent publicly available HINTS datasets. The combined HINTS 5 Cycles 4 (N = 3,865) and 3 (N = 5,438) datasets consist of a total sample of 9,303 adults. The study was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of East Tennessee State University and exempted as the HINTS datasets are de-identified and publicly available.

Measures and variables

Dependent variable

The dependent variable is "metabolic condition", derived from three distinct questions about diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. For diabetes, the participants were asked, "Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you have diabetes or high blood sugar?" (yes/no). Hypertension was assessed with the question, "Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you have high blood pressure or hypertension?" (yes/no). Obesity status was determined using body mass index (BMI), and defined as underweight = <18.5, healthy/normal = 18.5–24.9, overweight = 25.0–29.9, and obese ≥ 30.0. Obese was defined as BMI ≥ 30.0 and not obese as BMI < 30 [32, 33]. Thus, the variable "metabolic condition" in this study was ascertained as participants who had diabetes, hypertension, or were obese.

Independent variables

The main independent variable is the HINTS survey year, which was based on the 2019 and 2020 surveys, given that COVID-19 cases were widespread globally by January 2020 [31, 34, 35]. The 2019 HINTS data were used as the pre-COVID-19 pandemic cohort, while the 2020 HINTS data were used as the COVID-19 pandemic cohort for stratified analysis.

Other independent variables analyzed in this study included self-reported sociodemographic characteristics, moderate physical activity intensity, cigarette smoking status, e-cigarette use status, and anxiety/depression symptoms [36–38]. The sociodemographic variables included age (18–25, 26–34, 35–49, 50–64, and 65+), sex (male/female), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black/African American, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian, and non-Hispanic others), gender identity (heterosexual/straight or sexual minorities [homosexual, lesbian, gay, or bisexual]), marital status (single/never married, married/living as married, divorced/separated, or widowed), level of education completed (less than high school, high school graduate, some college, and college graduate or higher), and total family income (<$20,000, $20,000 to < $35,000, $35,000 to < $50,000, $50,000 to < $75,000, or ≥ $75,000). General health status was based on self-ratings of overall health as excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor. Due to limited samples, we dichotomized general health status into excellent/very good/good or fair/poor. The number of days per week of moderate intensity physical activity (none and at least one day per week), cigarette smoking status (never/non-smoker, former smoker, and current daily or some days smoker), and e-cigarette use status (never used, former user, and current daily/some days user) were also included.

The anxiety/depression symptoms variable was constructed from Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the HINTS 5 survey. The PHQ-4 assesses symptoms/signs of anxiety and depression, with total scores from 0–12 (0–2 = normal/negative, 3–5 = mild, 6–8 = moderate, and 9–12 = severe) [39, 40]. Thus, anxiety/depression symptoms were categorized into normal or no anxiety/depression, mild, moderate, and severe.

Statistical analyses

The HINTS sampling weight was applied to the analysis to achieve population estimates and offset nonresponse. We estimated the weighted prevalence of each component of metabolic condition before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The weighted prevalence and unweighted frequencies of metabolic conditions by the sociodemographic characteristics, moderate-intensity physical activity, cigarette smoking status, e-cigarette use status, and anxiety/depression symptoms were computed to characterize the survey sample before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, two logistic regression analyses represented by two models were conducted. While Model 1 assessed the association between the metabolic conditions and independent variables using the data before the pandemic, Model 2 utilized the data during the pandemic. All analyses were weighted using the HINTS sampling weight and replicate weight to offset non-response bias and to achieve nationally representative estimates [30, 31]. The weighted percentages, adjusted odds ratios (AOR), 95% 2-tailed confidence intervals (CI), and statistically significant p-value (< 0.05) have been reported.

Results

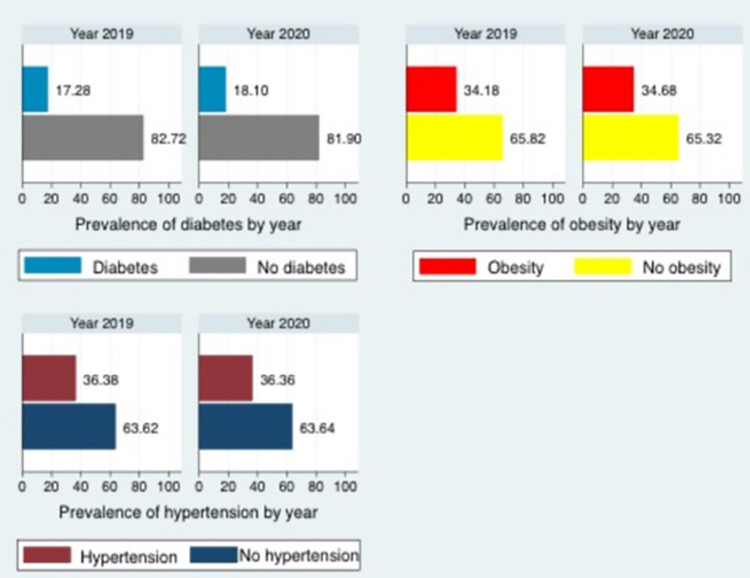

The prevalence of each metabolic condition (diabetes, hypertension, and obesity) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic is presented in Fig 1. The results showed that the prevalence of diabetes was higher during the COVID-19 pandemic (18.10%) than before the pandemic (17.28%). However, the prevalence of hypertension (36.36% vs. 36.38%) and obesity (34.68% vs. 34.18%) was similar during and before the pandemic.

Fig 1. The prevalence of diabetes, obesity, and hypertension before (2019) and during (2020) the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 1 presents the prevalence of metabolic conditions by independent variables before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall, the prevalence of metabolic conditions (54.96% vs. 56.09%) was higher during the pandemic than before the pandemic. The distribution of the prevalence of metabolic conditions within the sociodemographic groups, moderate intensity physical activity, cigarette smoking status, and e-cigarette use status before and during the COVID-19 pandemic varied. The prevalence of metabolic conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to before the pandemic increased for individuals aged 35–49 and 50–64 years but decreased for those aged 18–25, 26–34, and ≥65 years. The prevalence also increased for all non-Hispanic racial/ethnic groups but decreased for Hispanic individuals. The prevalence of metabolic condition was higher for individuals who did not engage in moderate-intensity physical activity compared to those who engaged in at least one moderate-intensity physical activity per week. Individuals who were former cigarette smokers or current smokers had an increased prevalence of metabolic conditions. For e-cigarette use groups, the prevalence had increased for those who had never used e-cigarettes and those who currently used e-cigarettes; however, it decreased for former e-cigarette users.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of U.S. adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic and association with metabolic conditions (N = 9,189).

| Before the COVID-19 pandemic (2019) | During the COVID-19 pandemic (2020) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic conditions | Metabolic conditions | ||||||

| Total, n | n(%) | Total, n | n(%) | ||||

| Characteristics | (n = 5,359) | 3,287 (54.96) | P value | (n = 3,830) | 2,353 (56.09) | P value | |

| Age | < .001 | < .001 | |||||

| 18–25 | 187 (11.78) | 51 (32.54) | 147(13.32) | 44 (29.31) | |||

| 26–34 | 493 (12.49) | 170 (38.38) | 337 (12.97) | 118 (37.98) | |||

| 35–49 | 964 (24.61) | 444 (47.75) | 701 (25.47) | 342 (55.97) | |||

| 50–64 | 1,654 (31.11) | 1,067 (61.25) | 1,137 (27.78) | 746 (65.53) | |||

| 65+ | 1,930 (20.02) | 1,470 (76.64) | 1,396 (20.45) | 1,042 (73.34) | |||

| Sex | .577 | .288 | |||||

| Female | 2,795 (50.77) | 1,677 (54.53) | 2,038 (50.88) | 1,242 (55.07) | |||

| Male | 2,091 (49.23) | 1,320 (55.95) | 1,486 (49.12) | 934 (57.75) | |||

| Race/ethnicity | .002 | < .001 | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 3,030 (63.49) | 1,740 (53.04) | 2,125 (63.33) | 1,245 (55.55) | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 669 (11.26) | 505 (64.76) | 478 (11.145) | 369 (70.58) | |||

| Hispanic | 724 (16.83) | 444 (59.00) | 595 (16.96) | 343 (49.20) | |||

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 223 (5.35) | 111 (37.57) | 160 (5.23) | 81 (44.75) | |||

| Non-Hispanic other | 165 (3.07) | 100 (48.46) | 119 (3.34) | 72 (67.55) | |||

| Gender identity | .610 | .658 | |||||

| Heterosexual | 4,747 (95.65) | 2,896 (54.96) | 3,389 (94.57) | 2,083 (56.45) | |||

| Homosexual or lesbian/gay or bisexual | 194 (4.35) | 113 (51.12) | 163 (5.43) | 92 (53.50) | |||

| Marital status | < .001 | < .001 | |||||

| Single/never married | 876 (30.52) | 468 (45.59) | 644 (30.87) | 354 (49.31) | |||

| Married/living as married | 2,827 (55.69) | 1,654 (56.43) | 1,972 (54.77) | 1,177 (58.39) | |||

| Divorced/separated | 936 (8.94) | 623 (63.57) | 679 (9.75) | 445 (58.45) | |||

| Widowed | 581 (4.85) | 461 (78.85) | 410 (4.61) | 310 (77.46) | |||

| Level of education completed | < .001 | < .001 | |||||

| Less than High School | 327 (6.88) | 239 (65.38) | 273 (8.05) | 202 (66.33) | |||

| High School graduate | 932 (23.36) | 675 (63.18) | 702 (22.47) | 509 (66.69) | |||

| Some college | 1,580 (40.26) | 1,052 (57.32) | 1,075 (39.16) | 707 (56.87) | |||

| College graduate or higher | 2,394 (29.50) | 1,243 (43.09) | 1,658 (30.32) | 865 (45.42) | |||

| Total annual family income | < .001 | < .001 | |||||

| <$20,000 | 883 (18.35) | 636 (62.99) | 619 (15.09) | 455 (67.22) | |||

| $20,000 - $34,999 | 608 (11.05) | 417 (62.90) | 450 (11.48) | 298 (61.18) | |||

| $35,000 - $49,999 | 623 (13.48) | 412 (59.33) | 459 (12.70) | 300 (62.05) | |||

| $50,000 - $74,999 | 845 (17.46) | 524 (55.54) | 589 (18.20) | 351 (54.86) | |||

| ≥$75,000 | 1,795 (39.66) | 915 (46.42) | 1,319 (42.54) | 695 (48.49) | |||

| General health status | < .001 | < .001 | |||||

| Excellent/very good/good | 4,478 (84.84) | 2,555 (50.08) | 3,187 (85.89) | 1,818 (51.72) | |||

| Fair/poor | 853 (15.16) | 713 (81.98) | 626 (14.11) | 525 (82.99) | |||

| Moderate physical activity intensity | < .001 | < .001 | |||||

| None | 1,421 (25.78) | 1,065 (68.23) | 1,041 (27.12) | 773 (69.39) | |||

| At least one day per week | 3,861 (74.22) | 2,169 (50.26) | 2,739 (72.88) | 1,545 (51.01) | |||

| Anxiety/depression symptoms | .001 | .229 | |||||

| None | 3,771 (68.35) | 2,252 (52.23) | 2,669 (68.57) | 1,594 (53.65) | |||

| Mild | 865 (18.08) | 533 (55.43) | 629 (17.48) | 398 (59.62) | |||

| Moderate | 334 (7.40) | 225 (57.83) | 258 (7.93) | 174 (61.98) | |||

| Severe | 236 (6.18) | 174 (74.62) | 173 (6.02) | 113 (58.89) | |||

| Cigarette smoking status | < .001 | < .001 | |||||

| Never | 3,261 (64.22) | 1,892 (51.74) | 2,407 (63.11) | 1,403 (50.98) | |||

| Former smoker | 1,406 (23.27) | 984 (63.86) | 931 (23.02) | 628 (67.91) | |||

| Current smoker | 611 (12.52) | 364 (55.43) | 436 (13.87) | 287 (59.39) | |||

| E-cigarette use status | < .001 | .005 | |||||

| Never | 4,591 (80.77) | 2,882 (57.15) | 3,297 (80.91) | 2,070 (58.40) | |||

| Former user | 526 (13.83) | 282 (53.61) | 381 (12.71) | 205 (52.51) | |||

| Current user | 173 (5.40) | 86 (28.66) | 114 (6.39) | 55 (37.24) | |||

Data source: 2019 and 2020 Health Information National Trends Surveys, HINTS 5 Cycles 3 and 4, respectively.

Unweighted N = 9,189 and weighted N = 501,680,570.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic data (HINTS 5 Cycles 3) were collected from January through April 2019, and during the COVID-19 pandemic data were collected from February through June 2020.

Frequencies were not weighted, while percentages were weighted. Differences in total numbers in categories may be due to missing data.

Table 2 shows metabolic conditions and their associated factors before (Model 1) and during (Model 2) the COVID-19 pandemic, respectively. Before the pandemic, compared to age 18–25 years, only two groups of individuals aged 50–64 (AOR = 2.64, 95% CI = 1.20, 5.77) and 65 years or older (AOR = 4.82, 95% CI = 2.25, 10.32) had significantly higher odds of metabolic conditions. During the pandemic, the likelihood of metabolic conditions was significantly higher for four groups: individuals aged 26–34 (AOR = 1.95, 95% CI = 1.04, 3.67), 35–49 (AOR = 4.13, 95% CI = 2.12, 8.04), 50–64 (AOR = 6.19, 95% CI = 3.03, 12.65), and 65 years or older (AOR = 7.82, 95% CI = 3.92, 15.57) compared to age 18–25 years. During the pandemic, males had significantly higher odds of metabolic conditions (AOR = 1.28, 95% CI = 1.01, 1.64) relative to females, whereas the odds were not different before the pandemic. Compared to non-Hispanic White people, the odds were significantly higher for non-Hispanic Black people before (AOR = 2.01, 95% CI = 1.26, 3.22) and during (AOR = 2.09, 95% CI = 1.22, 3.58) the pandemic. Engaging in at least one moderate-intensity physical activity per week was associated with a lower likelihood of metabolic conditions before (AOR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.46, 0.88) and during (AOR = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.42, 0.79) the pandemic as compared to no physical activity. Having mild (AOR = 1.52, 95% CI = 1.06, 2.19) or severe (AOR = 2.44, 95% CI = 1.27, 4.69) anxiety/depression symptoms, compared to no anxiety/depression symptoms, was associated with higher metabolic conditions before the pandemic. Only mild anxiety/depression symptoms (AOR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.01, 2.38) were associated with higher metabolic conditions during the pandemic. Compared to people who never smoked cigarettes, former cigarette smokers had significantly higher odds of metabolic conditions before (AOR = 1.38, 95% CI = 1.01, 1.87) and during (AOR = 1.57, 95% CI = 1.10, 2.25) the pandemic, but not current smokers. Before the pandemic, the likelihood of metabolic conditions was significantly lower for current e-cigarette users (AOR = 0.44, 95% CI = 0.23, 0.85) compared to those who had never used e-cigarettes, with no difference observed during the pandemic.

Table 2. The odds of metabolic conditions among U.S. adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic (N = 9,189).

| Before the COVID-19 (Model 1) | During the COVID-19 (Model 2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | |

| Age | ||||

| 18–25 | Ref. | - | Ref. | - |

| 26–34 | 1.04 | (0.44, 2.45) | 1.95 * | (1.04, 3.67) |

| 35–49 | 1.46 | (0.66, 3.26) | 4.13 *** | (2.12, 8.04) |

| 50–64 | 2.64 * | (1.20, 5.77) | 6.19 *** | (3.03, 12.65) |

| 65+ | 4.82 *** | (2.25, 10.32) | 7.82 *** | (3.92, 15.57) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | Ref. | - | Ref. | - |

| Male | 1.11 | (0.85, 1.44) | 1.28 * | (1.01, 1.64) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref. | - | Ref. | - |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2.01 ** | (1.26, 3.22) | 2.09 ** | (1.22, 3.58) |

| Hispanic | 1.33 | (0.93, 1.89) | 0.91 | (0.64, 1.28) |

| Non-Asian | 0.74 | (0.44, 1.25 | 0.72 | (0.42, 1.25) |

| Non-Hispanic other | 1.37 | (0.56, 3.35) | 1.25 | (0.57, 2.72) |

| Gender identity | ||||

| Heterosexual | Ref. | - | Ref. | - |

| Homosexual/lesbian/gay/bisexual | 1.43 | (0.67, 3.06) | 1.30 | (0.58, 2.93) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single/never married | Ref. | - | Ref. | |

| Married/living as married | 1.68 ** | (1.18, 2.39) | 0.74 | (0.49, 1.13) |

| Divorced/separated | 1.40 | (0.92, 2.14) | 0.46 ** | (0.27, 0.78) |

| Widowed | 1.89 | (0.97, 3.66) | 0.71 | (0.36, 1.40) |

| Level of education completed | ||||

| Less than High School | Ref. | - | Ref. | - |

| High school graduate | 1.40 | (0.72, 2.71) | 1.23 | (0.611, 2.49) |

| Some college | 1.31 | (0.67, 2.55) | 0.93 | (0.45, 1.92) |

| College graduate/higher | 1.07 | (0.54, 2.14) | 0.72 | (0.35, 1.47) |

| Total family annual income | ||||

| <$20,000 | Ref. | Ref. | - | |

| $20,000 - $34,999 | 1.02 | (0.61, 1.68) | 0.77 | (0.38, 1.56) |

| $35,000 - $49,999 | 0.94 | (0.54, 1.65) | 0.78 | (0.42, 1.45) |

| $50,000 - $74,999 | 0.89 | (0.52, 1.53) | 0.67 | (0.39, 1.17) |

| ≥$75,000 | 0.73 | (0.45, 1.17) | 0.63 | (0.37, 1.07) |

| General health status | ||||

| Excellent/very good/good | Ref | - | Ref | - |

| Fair/poor | 2.82 *** | (1.99, 3.99) | 2.99 *** | (1.97, 4.53) |

| Moderate physical activity intensity | ||||

| None | Ref | Ref | ||

| At least one day per week | 0.64 ** | (0.46, 0.88) | 0.58 *** | (0.42, 0.79) |

| Anxiety/depression symptoms | ||||

| None | Ref. | Ref. | - | |

| Mild | 1.52 * | (1.06, 2.19) | 1.55 * | (1.01, 2.38) |

| Moderate | 1.31 | (0.83, 2.08) | 1.76 | (0.87, 3.57) |

| Severe | 2.44 ** | (1.27, 4.69) | 1.53 | (0.72, 3.22) |

| Cigarette smoking status | ||||

| Never smoker | Ref. | Ref. | - | |

| Former smoker | 1.38 * | (1.01, 1.87) | 1.57 ** | (1.10, 2.25) |

| Current smoker | 0.93 | (0.59, 1.46) | 1.02 | (0.54, 1.95) |

| E-cigarette smoking status | ||||

| Never user | Ref. | Ref. | - | |

| Former user | 1.03 | (0.63, 2.68) | 1.03 | (0.60, 1.78) |

| Current user | 0.44 * | (0.23, 0.85) | 0.63 | (0.30, 1.30) |

Data source: 2019 and 2020 Health Information National Trends Surveys, HINTS 5 Cycles 3 and 4 respectively.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic data (HINTS 5 Cycles 3) were collected from January through April 2019, and during the COVID-19 pandemic data were collected from February through June 2020.

AOR = Adjusted odds ratio. 95% CI = 95% confidence interval. Ref = Reference group.

*p ≤0.05

**p ≤0.01

***p ≤ 0.001.

Discussion

This study assessed the prevalence of metabolic conditions among U.S. adults and the underlying associated factors before and during the COVID-19 pandemic using the HINTS 2019 and 2020 survey data. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to use nationally representative U.S. adult data to highlight associations between metabolic outcomes, sociodemographic factors, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

There was an increase in the overall prevalence of metabolic conditions, especially among certain subgroups during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is consistent with a systematic review that assessed the impact of disasters, including pandemics, on metabolic conditions and reported increased incidence and mortality for diabetes and obesity [41]. Our findings indicate that being elderly (aged 50+), non-Hispanic Black person, former smoker, having fair/poor health status, and having mild anxiety significantly increased the likelihood of metabolic conditions pre- and during the pandemic. However, the disparities in these health and sociodemographic factors were greater during the pandemic.

Previous studies have established that the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated and further unmasked existing disparities in metabolic outcomes [42–46]. For instance, we found that the odds of metabolic outcomes were significantly higher only among the elderly age groups (50–64 and 65+) compared to young adults before the pandemic. However, these increases in odds almost doubled among these age groups during the pandemic. Significantly higher odds were also noted in the middle age groups (26–34 and 35–49), where the odds almost tripled for the 35–49 age group during the pandemic. Consistent with the literature, our results indicated age was the strongest factor associated with an increased likelihood of adverse metabolic conditions during the pandemic [46–48] with higher age range conferring a higher risk for metabolic conditions. The association between age and metabolic conditions during the pandemic and the risks for adverse health conditions from COVID-19 suggests that health interventions targeted at high-risk groups such as the elderly could optimize outcomes, particularly during disasters such as this global pandemic.

Moreover, this study provides additional evidence that individual health behaviors played a critical role in developing metabolic conditions before and during the pandemic. For example, while being a former smoker increased the odds of metabolic conditions, engaging in moderate physical activity decreased the odds. In light of pandemic-related restrictions associated with increased social isolation and psychological distress [49], people are more likely to smoke and engage in sedentary behaviors such as screen time which limits physical activity [50, 51] and increases the risk of metabolic diseases. A recent systematic review assessing screen-based sedentary behavior among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic reported a dose-response association between increased levels of screen time and components of metabolic syndrome [28]. Our findings are consistent with the existing literature on smoking as a risk factor for metabolic conditions [52–55] and increased physical activity as a protective factor [56–58]. As such, both smoking cessation and physical activity should be encouraged to reduce the risk of metabolic conditions, especially during this pandemic.

Implications to practice and research

The COVID-19 pandemic has placed extraordinary demand on public health systems and essential services, while individuals with underlying health conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases are at higher risk of hospitalization and death [8, 59]. Thus, the association between COVID-19 and metabolic conditions alongside the disparities highlighted in this study suggests the need for further research and fair allocation of medical resources to address these conditions during and after the pandemic.

Although this study provides additional evidence to the literature on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic related to metabolic conditions among the generally representative U.S. population, some limitations should be considered. These limitations include self-reporting bias and potential underestimation of chronic health problems, such as metabolic conditions, that develop over time. Given the cross-sectional data and lack of temporal sequence information on the variables, we could not make causal inferences. Longitudinal follow-up should be continued for future research to further validate this study’s findings. Additionally, public health assessment tools specifically validated for chronic diseases, such as metabolic conditions, that could be used for national observatory datasets would allow researchers to more rapidly evaluate data in real time in future public health crises, such as this recent global pandemic. Standardized validated tools would provide more meaningful assessments and results nationally and internationally. Moreover, there are probable effects of confounders not considered in this study such as sedentary behavior, sleep pattern, eating habits, and employment that might give rise to inaccurate estimates of the true association. Furthermore, the HINTS datasets do not contain responses specific to the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, because metabolic conditions and lifestyle behavioral risk factors take time to accumulate and change health conditions, the results of this study might be biased and under-estimated given the durations of the data before (January through April 2019) and during (February through June 2020) the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, future studies comparing the rates and prevalence of metabolic conditions before and during the pandemic are needed considering the longer of the data.

Despite these limitations, these data validate that high-risk groups, such as advanced age, should be targeted for interventions to protect against the negative effects of COVID-19. Another gap in the literature that could be addressed with future research is the health consequences of a public lockdown, which was the mitigation strategy for a global pandemic, compared to the consequences of the infectious disease itself. Development of tools designed to measure outcomes secondary to each of these distinctly different effects would benefit future research and resultant health policy. For example, it would be helpful to know if depressive symptoms were a direct effect of the disease, such as suffering from long-COVID, or from the social isolation secondary to the public lockdown. Overall, the HINTS dataset provides an efficient means to evaluate important public health questions in a rapidly evolving situation such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

In this nationally representative sample of U.S. adults, the prevalence of metabolic conditions increased during the COVID-19 pandemic in certain subgroups of individuals. Specifically, there was an increased risk of metabolic outcomes associated with older age. Other groups with signals for increased risk included: non-Hispanic Black people, former smokers, individuals with poor health status, and mild anxiety. Thus, there is a need for proper rationing of resources to address these conditions during the pandemic.

Data Availability

The data is publicly available at HINTS (https://hints.cancer.gov/).

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157–60. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update. 2022. [Dec 5, 2022]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19—21-december-2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Waard A-KM, Hollander M, Korevaar JC, Nielen MMJ, Carlsson AC, Lionis C, et al. Selective prevention of cardiometabolic diseases: activities and attitudes of general practitioners across Europe. European Journal of Public Health. 2018;29(1):88–93. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cky112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danaei G, Ding EL, Mozaffarian D, Taylor B, Rehm J, Murray CJL, et al. Correction: The Preventable Causes of Death in the United States: Comparative Risk Assessment of Dietary, Lifestyle, and Metabolic Risk Factors. PLOS Medicine. 2011;8(1):10.1371/annotation/0ef47acd-9dcc-4296-a897-872d182cde57. doi: 10.1371/annotation/0ef47acd-9dcc-4296-a897-872d182cde57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suglia SF, Koenen KC, Boynton-Jarrett R, Chan PS, Clark CJ, Danese A, et al. Childhood and Adolescent Adversity and Cardiometabolic Outcomes: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(5):e15–e28. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2020. 2020 [updated 2020-09December 22, 2021]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity Among Adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2020;(360):1–8. Epub 2020/06/04. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Almeida-Pititto B, Dualib PM, Zajdenverg L, Dantas JR, de Souza FD, Rodacki M, et al. Severity and mortality of COVID 19 in patients with diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome. 2020;12(1):75. doi: 10.1186/s13098-020-00586-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elezkurtaj S, Greuel S, Ihlow J, Michaelis EG, Bischoff P, Kunze CA, et al. Causes of death and comorbidities in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Scientific Reports. 2021;11(1):4263. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-82862-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorjee K, Kim H, Bonomo E, Dolma R. Prevalence and predictors of death and severe disease in patients hospitalized due to COVID-19: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of 77 studies and 38,000 patients. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(12):e0243191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kompaniyets L, Pennington AF, Goodman AB, Rosenblum HG, Belay B, Ko JY, et al. Underlying Medical Conditions and Severe Illness Among 540,667 Adults Hospitalized With COVID-19, March 2020-March 2021. Prev Chronic Dis. 2021;18:E66. Epub 2021/07/02. doi: 10.5888/pcd18.210123 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8269743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mueller AL, McNamara MS, Sinclair DA. Why does COVID-19 disproportionately affect older people? Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(10):9959–81. Epub 2020/05/29. doi: 10.18632/aging.103344 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishiga M, Wang DW, Han Y, Lewis DB, Wu JC. COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease: from basic mechanisms to clinical perspectives. Nature Reviews Cardiology. 2020;17(9):543–58. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0413-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bellido V, Pérez A. Consequences of COVID-19 on people with diabetes. Endocrinologia, diabetes y nutricion. 2020;67(6):355–6. Epub 2020/06/02. doi: 10.1016/j.endinu.2020.04.001 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7211748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farag AA, Hassanin HM, Soliman HH, Sallam A, Sediq AM, Abd Elbaser ES, et al. Newly Diagnosed Diabetes in Patients with COVID-19: Different Types and Short-Term Outcomes. Tropical medicine and infectious disease. 2021;6(3). Epub 2021/08/28. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed6030142 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8396224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karatas S, Yesim T, Beysel S. Impact of lockdown COVID-19 on metabolic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus and healthy people. Primary care diabetes. 2021;15(3):424–7. Epub 2021/01/15. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2021.01.003 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7834877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanchis-Gomar F, Lavie CJ, Mehra MR, Henry BM, Lippi G. Obesity and Outcomes in COVID-19: When an Epidemic and Pandemic Collide. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(7):1445–53. Epub 2020/07/06. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.05.006 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7236707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schofield J, Leelarathna L, Thabit H. COVID-19: Impact of and on Diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2020;11(7):1429–35. Epub 2020/06/06. doi: 10.1007/s13300-020-00847-5 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soeroto AY, Soetedjo NN, Purwiga A, Santoso P, Kulsum ID, Suryadinata H, et al. Effect of increased BMI and obesity on the outcome of COVID-19 adult patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes & metabolic syndrome. 2020;14(6):1897–904. Epub 2020/10/03. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.09.029 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7521380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanji Y, Sawada S, Watanabe T, Mita T, Kobayashi Y, Murakami T, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on glycemic control among outpatients with type 2 diabetes in Japan: A hospital-based survey from a country without lockdown. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;176:108840. Epub 2021/05/03. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.108840 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8084613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biamonte E, Pegoraro F, Carrone F, Facchi I, Favacchio G, Lania AG, et al. Weight change and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes patients during COVID-19 pandemic: the lockdown effect. Endocrine. 2021;72(3):604–10. Epub 2021/05/06. doi: 10.1007/s12020-021-02739-5 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8098639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Önmez A, Gamsızkan Z, Özdemir Ş, Kesikbaş E, Gökosmanoğlu F, Torun S, et al. The effect of COVID-19 lockdown on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Turkey. Diabetes & metabolic syndrome. 2020;14(6):1963–6. Epub 2020/10/16. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.10.007 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7548075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sathish T, Cao Y. Is newly diagnosed diabetes as frequent as preexisting diabetes in COVID-19 patients? Diabetes & metabolic syndrome. 2021;15(1):147–8. Epub 2020/12/15. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.12.024 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.García-Garro PA, Aibar-Almazán A, Rivas-Campo Y, Vega-Ávila GC, Afanador-Restrepo DF, Martínez-Amat A, et al. The Association of Cardiometabolic Disease with Psychological Factors in Colombian People during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Clin Med. 2021;10(21). Epub 2021/11/14. doi: 10.3390/jcm10214959 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8584396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hossain MM, Tasnim S, Sultana A, Faizah F, Mazumder H, Zou L, et al. Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: a review. F1000Res. 2020;9:636. Epub 2020/10/24. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.24457.1 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7549174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neill E, Meyer D, Toh WL, van Rheenen TE, Phillipou A, Tan EJ, et al. Alcohol use in Australia during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic: Initial results from the COLLATE project. Psychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 2020;74(10):542–9. Epub 2020/07/01. doi: 10.1111/pcn.13099 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7436134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, Chtourou H, Boukhris O, Masmoudi L, et al. Effects of COVID-19 Home Confinement on Eating Behaviour and Physical Activity: Results of the ECLB-COVID19 International Online Survey. Nutrients. 2020;12(6). Epub 2020/06/03. doi: 10.3390/nu12061583 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7352706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Musa S, Elyamani R, Dergaa I. COVID-19 and screen-based sedentary behaviour: Systematic review of digital screen time and metabolic syndrome in adolescents. PLoS One. 2022;17(3):e0265560. Epub 2022/03/22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0265560 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8936454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muhamad S-A, Ugusman A, Kumar J, Skiba D, Hamid AA, Aminuddin A. COVID-19 and Hypertension: The What, the Why, and the How. Frontiers in Physiology. 2021;12. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.665064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finney Rutten LJ, Blake KD, Skolnick VG, Davis T, Moser RP, Hesse BW. Data Resource Profile: The National Cancer Institute’s Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). Int J Epidemiol. 2020;49(1):17–j. Epub 2019/05/01. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz083 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7124481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Westat. Health Information National Trends Survey 5 (HINTS 5) Cycle 4 2020 [August 1, 2021]. Methodology Report. Rockville, MD: Westat.:[Available from: https://hints.cancer.gov/docs/methodologyreports/HINTS5_Cycle4_MethodologyReport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 32.CDC. Defining Adult Overweight and Obesity 2021. [Dec 13, 2021]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/defining.html. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landers SJ, Mimiaga MJ, Conron KJ. Sexual orientation differences in asthma correlates in a population-based sample of adults. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(12):2238–41. Epub 2011/10/25. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300305 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3222437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gardner L. Update January 31: Modeling the Spreading Risk of 2019-nCoV. 2020. [Dec. 14, 2021]. Available from: https://systems.jhu.edu/research/public-health/ncov-model-2/. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polyakova M, Kocks G, Udalova V, Finkelstein A. Initial economic damage from the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States is more widespread across ages and geographies than initial mortality impacts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(45):27934–9. Epub 2020/10/22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2014279117 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7668078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dibato JE, Montvida O, Zaccardi F, Sargeant JA, Davies MJ, Khunti K, et al. Association of Cardiometabolic Multimorbidity and Depression With Cardiovascular Events in Early-Onset Adult Type 2 Diabetes: A Multiethnic Study in the U.S. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(1):231–9. Epub 2020/11/13. doi: 10.2337/dc20-2045 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tornhammar P, Jernberg T, Bergström G, Blomberg A, Engström G, Engvall J, et al. Association of cardiometabolic risk factors with hospitalisation or death due to COVID-19: population-based cohort study in Sweden (SCAPIS). BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):e051359. Epub 20210902. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051359 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8413466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakakibara BM, Obembe AO, Eng JJ. The prevalence of cardiometabolic multimorbidity and its association with physical activity, diet, and stress in Canada: evidence from a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1361. Epub 2019/10/28. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7682-4 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6814029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Löwe B, Wahl I, Rose M, Spitzer C, Glaesmer H, Wingenfeld K, et al. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2010;122(1–2):86–95. Epub 2009/07/21. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.019 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613–21. Epub 2009/12/10. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Rubeis V, Lee J, Anwer MS, Yoshida-Montezuma Y, Andreacchi AT, Stone E, et al. Impact of disasters, including pandemics, on cardiometabolic outcomes across the life-course: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(5):e047152. Epub 20210503. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047152 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8098961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wassink J, Perreira KM, Harris KM. Beyond Race/Ethnicity: Skin Color and Cardiometabolic Health Among Blacks and Hispanics in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health. 2017;19(5):1018–26. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0495-y ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5359067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mozumdar A, Liguori G. Persistent increase of prevalence of metabolic syndrome among U.S. adults: NHANES III to NHANES 1999–2006. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(1):216–9. Epub 20101001. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0879 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3005489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):491–7. Epub 20120117. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Price-Haywood EG, Burton J, Fort D, Seoane L. Hospitalization and Mortality among Black Patients and White Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(26):2534–43. Epub 20200527. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa2011686 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7269015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferdinand KC, Reddy TK. Disparities in the COVID-19 pandemic: A clarion call for preventive cardiology. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2021;8:100283. Epub 20211016. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpc.2021.100283 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8520280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sinclair AJ, Abdelhafiz AH. Cardiometabolic disease in the older person: prediction and prevention for the generalist physician. Cardiovasc Endocrinol Metab. 2020;9(3):90–5. Epub 20200222. doi: 10.1097/XCE.0000000000000193 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7410030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Risks and Vaccine Information for Older Adults 2021. [cited January 8, 2022]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/aging/covid19/covid19-older-adults.html#increased-risk. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murphy L, Markey K, C OD, Moloney M, Doody O. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and its related restrictions on people with pre-existent mental health conditions: A scoping review. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2021;35(4):375–94. Epub 2021/06/29. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2021.05.002 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Puccinelli PJ, da Costa TS, Seffrin A, de Lira CAB, Vancini RL, Nikolaidis PT, et al. Reduced level of physical activity during COVID-19 pandemic is associated with depression and anxiety levels: an internet-based survey. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):425. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10470-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tzu-Hsuan Chen D. The psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on changes in smoking behavior: Evidence from a nationwide survey in the UK. Tob Prev Cessat. 2020;6:59. Epub 2020/11/10. doi: 10.18332/tpc/126976 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7643580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khan SS, Ning H, Sinha A, Wilkins J, Allen NB, Vu THT, et al. Cigarette Smoking and Competing Risks for Fatal and Nonfatal Cardiovascular Disease Subtypes Across the Life Course. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(23):e021751. Epub 2021/11/18. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.021751 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin MS, Huang TJ, Lin YC, Jane SW, Chen MY. The association between smoking and cardiometabolic risk among male adults with disabilities in Taiwan. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;18(2):106–12. Epub 2018/08/18. doi: 10.1177/1474515118795602 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cole TB. Smoking Cessation and Reduction of Cardiovascular Disease Risk. JAMA. 2019;322(7):651. Epub 2019/08/21. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.11166 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2014. Available from: https://aahb.org/Resources/Pictures/Meetings/2014-Charleston/PPT%20Presentations/Sunday%20Welcome/Abrams.AAHB.3.13.v1.o.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang X, Cash RE, Bower JK, Focht BC, Paskett ED. Physical activity and risk of cardiovascular disease by weight status among U.S adults. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0232893. Epub 2020/05/10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232893 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7209349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dipietro L, Zhang Y, Mavredes M, Simmens SJ, Whiteley JA, Hayman LL, et al. Physical Activity and Cardiometabolic Risk Factor Clustering in Young Adults with Obesity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2020;52(5):1050–6. Epub 2019/11/26. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002214 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7166161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Young DR, Coleman KJ, Ngor E, Reynolds K, Sidell M, Sallis RE. Associations between physical activity and cardiometabolic risk factors assessed in a Southern California health care system, 2010–2012. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E219. Epub 2014/12/20. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140196 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4273545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, Thome B, Parker M, Glickman A, et al. Fair Allocation of Scarce Medical Resources in the Time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):2049–55. Epub 2020/03/24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]