Abstract

The 2019 global coronavirus disease pandemic has led to an increase in the demand for polyethylene terephthalate (PET) packaging. Although PET is one of the most recycled plastics, it is likely to enter the aquatic ecosystem. To date, the chronic effects of PET microplastics (MPs) on aquatic plants have not been fully understood. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the adverse effects of PET MP fragments derived from PET bottles on the aquatic duckweed plant Lemna minor through a multigenerational study. We conducted acute (3-day exposure) and multigenerational (10 generations from P0 to F9) tests using different-sized PET fragments (PET0–200, < 200 μm; PET200–300, 200–300 μm; and PET300–500, 300–500 μm). Different parameters, including frond number, growth rate based on the frond area, total root length, longest root length, and photosynthesis, were evaluated. The acute test revealed that photosynthesis in L. minor was negatively affected by exposure to small-sized PET fragments (PET0–200). In contrast, the results of the multigenerational test revealed that large-sized PET fragments (PET300–500) showed substantial negative effects on both the growth and photosynthetic activity of L. minor. Continuous exposure to PET MPs for 10 generations caused disturbances in chloroplast distribution and inhibition of plant photosynthetic activity and growth. The findings of this study may serve as a basis for future research on the generational effects of MPs from various PET products.

Keywords: Irregular-shaped microplastic, Aquatic environment, Acute test, Freshwater ecosystem, Aquatic plant

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) is one of the most commonly used plastic polymers worldwide. Particularly, the demand for PET packaging increased during the 2019 global coronavirus disease pandemic (S&P Global, 2021). PET is widely used in various fields because of its high strength, rigidity, and hardness; low moisture absorption, friction, wear; and hydrolytic resistance. Different forms of PET, including fibers, sheets, and films, are used in food and beverage packaging, and PET bottles account for 30 % of the total PET consumption (Ji, 2013; Parolini et al., 2020b; Sinha et al., 2010). In Europe, in 2018, only 32.5 % of the total PET used was recycled (Plastics Europe, 2019), whereas in the US, from 1995 to 2016, only 19.6–39.7 % of PET bottles were recycled (NAPCOR, 2017). PET bottles that are not recycled are released into the ecosystem directly or indirectly through daily use and improper disposal processes. Plastic bottles are one of the top 10 items in ocean refuse (ICC, 2021), as well as freshwater refuse (Bauer-Civiello et al., 2019). Previous studies estimated that 55–60 % of plastic bottles are composed of PET (Rahman and Wahab, 2013). Even though PET is not the most detected or most abundant microplastic (MP) in the environment, PET MPs have been found in lakes across the world (Corcoran et al., 2015; Imhof et al., 2016; Zbyszewski and Corcoran, 2011; Zhang et al., 2016) and account for 1–8.8 % of the total MPs in water and sediments (Rodrigues et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2020) because “PET is the most abundant polyester plastic” (Tournier et al., 2020).

Aquatic plants play an important role in the nutrient cycle and oxygen supply of aquatic ecosystems, and act as a refuge for organisms (Gür et al., 2016). However, research on the effects of MPs and NPs on aquatic plants is limited compared with that on other terrestrial plants (Capozzi et al., 2018; Cui et al., 2022; Dovidat et al., 2020; Green et al., 2021; Jemec Kokalj et al., 2019; Kalčíková et al., 2020, Kalčíková et al., 2017; Mateos-Cárdenas et al., 2019; Rozman et al., 2021; van Weert et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2020). For instance, researchers have recently recognized and emphasized that aquatic vascular plants have often been ignored in MP research (Kalčíková, 2020). Only two studies have investigated the phytotoxicity of PET MPs used for glitters (Green et al., 2021) and PET microfibers (Cui et al., 2022) to duckweed.

Lemna minor is a widely distributed, rapidly growing, and free-floating aquatic plant. Thus, it has been recommended as a standard ecotoxicity test species by several international organizations (ASTM, 2012; ISO, 2005; OECD, 2006; USEPA, 2012). It has been used in several studies owing to its suitability for evaluating the impact of MPs on aquatic plants (Jemec Kokalj et al., 2019; Kalčíková et al., 2020, Kalčíková et al., 2017; Mateos-Cárdenas et al., 2019). In particular, limited research has been conducted on the effects of PET MPs on aquatic plants (Baeza et al., 2020; Heindler et al., 2017; Ji et al., 2020; Lehtiniemi et al., 2018; Maaß et al., 2017; Parolini et al., 2020a, Parolini et al., 2020b; Rodríguez-Hernández et al., 2019; Weber et al., 2018); additionally, only one multigenerational study has been conducted on microfibers and aquatic plants (Cui et al., 2022). Therefore, the present study focused on the multigenerational effects of MP fragments derived from PET water bottles on the duckweed L. minor with an aim to investigate the chronic effects of MPs. We hypothesized that different-sized microplastics would induce different effects on aquatic plants.

This study aimed to evaluate the acute and long-term effects of different-sized MP fragments from PET bottles on L. minor. PET fragments with size ranges of <200 μm (PET0–200), 200–300 μm (PET200–300), and 300–500 μm (PET300–500) were obtained from a commonly used PET water bottle. The adverse effects of different sizes of PET fragments on L. minor were evaluated using the three-day acute test and 10 generation test.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Preparation of PET MP fragments

A PET bottle was washed with distilled water and dried at 20 ± 1 °C. Subsequently, the bottle was cut into small pieces using micro scissors, ground using a stainless-steel foot file, and passed through sieves of varying sizes (200, 300, 500, and 1000 μm) to obtain PET fragments of sizes 0–200 μm, 200–300 μm, 300–500 μm, 500–1000 μm, and > 1000 μm, with a mass percentage distribution of 38.3 ± 8.5 %, 27.2 ± 4.5 %, 19.6 ± 1.6 %, 4.2 ± 0.6 %, and 10.2 ± 11.1 %, respectively (n = 3) (Fig. 1B). Because only a few fragments were larger than 500 μm, only those sized 0–200 μm, 200–300 μm, and 300–500 μm were used in this study. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (FTIR 4100; JASCO, Tokyo, Japan) was used to analyze a commonly used plastic water bottle, and FTIR findings were compared with the findings of previous studies (Andanson and Kazarian, 2008; Prasad et al., 2011), to confirm the composition of PET in the plastic (Fig. 1A). Morphotypes were confirmed using high resolution field-emission scanning electron microscopy (SU8010; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) (Fig. 1C). The average Feret's diameter of PET0–200, PET200–300, and PET300–500 was 105.6 ± 62.2, 177.2 ± 124.41, and 223.2 ± 161.1 μm, respectively (n = 100). The distribution of Feret's diameter is described in Fig. S1.

Fig. 1.

Characteristics of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) fragments derived from water bottles. (A) Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of PET fragments, (B) Mass percentage of PET fragments of each size range prepared from a water bottle (n = 3), and (C) High resolution field-emission scanning electron microscopic images of PET fragments used in the morphological test for L. minor.

2.2. Test species

Lemna minor was obtained from Professor T. Han's laboratory (Ghent University, Incheon, South Korea) and cultivated in our laboratory for three years. L. minor was cultured in Steinberg medium without pH adjustment at 24 °C under 24-h of continuous light (4000–6000 lx). The culture medium contained 350 mg/L KNO3, 90 mg/L KH2PO4, 12.6 mg/L K2HPO4, 100 mg/L MgSO4·7H2O, 295 mg/L Ca(NO3)2·4H2O, 0.12 mg/L H3BO3, 0.18 mg/L ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.044 mg/L Na2MoO4·2H2O, 0.018 mg/L MnCl2·4H2O, 0.76 mg/L FeCl3·6H2O, and 1.5 mg/L Na2EDTA·2H2O (ISO, 2017, ISO, 2005; OECD, 2006). The culture medium was changed every week, and unhealthy plants were removed.

2.3. Acute test

An acute test was conducted based on the root re-growth method, deriving sensitive response using rootless L. minor (Fig. 2A), as described by Park et al. (2013). The roots of two fronds of healthy L. minor plants were removed using scissors to prepare rootless L. minor, and one plant was then exposed to PET fragments in a 24-well plate, each well containing 3 mL solution of 500 mg/L PET fragments of different sizes. Exposure concentration at 500 mg/L was calculated as 2407 ± 9, 447 ± 7, 164 ± 10 particles/mL for PET0–200, PET200–300, and PET300–500, respectively, in the acute test (n = 4). The high test concentration was used in the present study to investigate a pollution hotspot (Haave et al., 2019). The test was performed under 24-h continuous illumination at 24 °C using four replicates (ISO, 2017, ISO, 2005; OECD, 2006). The frond number, frond area, root length, root cell viability, and photosynthetic effects were measured after 3-day exposure.

Fig. 2.

Study design for (A) acute (3 days) and (B) multigenerational tests. In the acute test, two fronds of L. minor without roots were exposed to 500 mg/L polyethylene terephthalate (PET) fragments for three days in a 24-well plate. In the generation test, two fronds of L. minor without roots were exposed to 250 mg/L PET fragments for one week in a 6-well plate. Then, two or three fronds of L. minor were separated from each well and re-exposed to the same conditions. The test was conducted weekly for each of the 10 generations.

2.4. Multigenerational test

A multigenerational test was performed to observe the long-term effects of PET fragments on L. minor (Fig. 2B). Rootless L. minor with two fronds were added to a 6-well plate, each well containing 10 mL culture medium with 250 mg/L PET fragments of different sizes. Exposure concentration at 250 mg/L was calculated as 1136 ± 85, 224 ± 18, 80 ± 4 particles/mL for PET0–200, PET200–300, and PET300–500, respectively (n = 6). The plate was placed in an incubator and maintained under continuous illumination at 24 °C for seven days. After seven days, two to three fronds of healthy L. minor were collected from each well, and the roots and foreign matter were removed by washing with distilled water. Furthermore, the plant was re-exposed to PET fragments of the same size and concentration in a new 6-well plate under the same conditions for seven days. Every seventh day, the test was regenerated because of the limited test space relative to the growth rate of L. minor. The test comprised 10 generations; 12 replicates were tested for the control and six replicates for the PET fragment exposure groups. The frond number, growth rate based on frond area, total root length, longest root length, and photosynthetic effects were measured for each generation.

2.5. Endpoints

Fronds of all sizes and colors were counted to determine the frond number. The frond area was analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Maryland, USA) based on an image of the top of the plant. Root cell viability was only measured in the acute test, which was conducted in accordance with the methods described by Kalčíková et al. (2017). Each plant exposed to PET fragments was collected and washed with distilled water to remove foreign matter, and then stained with 0.05 % Evans blue for 10 min. Subsequently, L. minor samples were washed thrice with distilled water to remove excess dye, and the roots were observed using a microscope (BX51; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) to confirm staining. Photosynthesis was measured using a closed FluorCam (Photon Systems Instruments, Drásov, Czech Republic) and analyzed using the FluorCam 7 software (Photon Systems Instruments, Drásov, Czech Republic). To confirm the effect of PET fragments on photosynthesis, the parameters F0 (minimum fluorescence in the dark-adapted state), Fm (maximum fluorescence in the dark-adapted state), Fv/Fm ([Fm − F0]/Fm; maximum photosystem II [PSII] quantum yield), ΦPSII (effective PSII quantum yield), NPQ (steady-state non-photochemical quenching), qN (coefficient of non-photochemical quenching in steady-state), qP (coefficient of photochemical quenching in steady-state), and qL (fraction of PSII centers that are “open”; “open” implies that the primary quinone acceptor of PSII is oxidized) were analyzed and compared.

To investigate the physical damage caused by PET fragments to L. minor plants, the air-facing surface of the leaves was analyzed using a field-emission scanning electron microscope (SU8010; Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Japan), and the outer cell walls (epicuticle layer) were observed using an optical microscope (BX51; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The leaves were fixed in 2.5 % glutaraldehyde (TEDPELLA, Inc., CA, USA) and dehydrated using ethanol and isoamyl acetate (DAEJUNG, South Korea). Scanning electron microscope samples were prepared as described by Kwak et al. (2017). Distribution of chloroplast in the cell was observed using a fluorescence microscope (BX51; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an X-Cite 110LED illumination system (Excelitas Technologies Corp., MA, USA).

2.6. Quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC)

All apparatus components were rinsed using acetone and distilled water prior to use. Cotton laboratory coats and nitrile gloves were always worn during the experiments. The culture medium was filtered or autoclaved prior to use. A static electricity remover (STABLO-AP, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) was used throughout the process of preparing PET fragments and the test solution. Well plates were covered for the exposure duration.

2.7. Data analyses

To calculate the frond number and frond area-specific growth rate (SGR FA), the following equation was used:

| (1) |

where X t2 is the frond number and frond area measured at the end of test t 2 (day 3 of the acute test or day 7 of each generation of the generation test), and X t1 denotes the frond number and frond area measured at the beginning of the test t 1 (day 0) (ISO, 2005; OECD, 2006; USEPA, 2012). The significance of differences between the measured values in this study was analyzed using Tukey's test in a one-way analysis of variance using the OriginPro 8 software (p < 0.05) (OriginLab, Northampton, Massachusetts, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Acute effects of PET fragments on L. minor

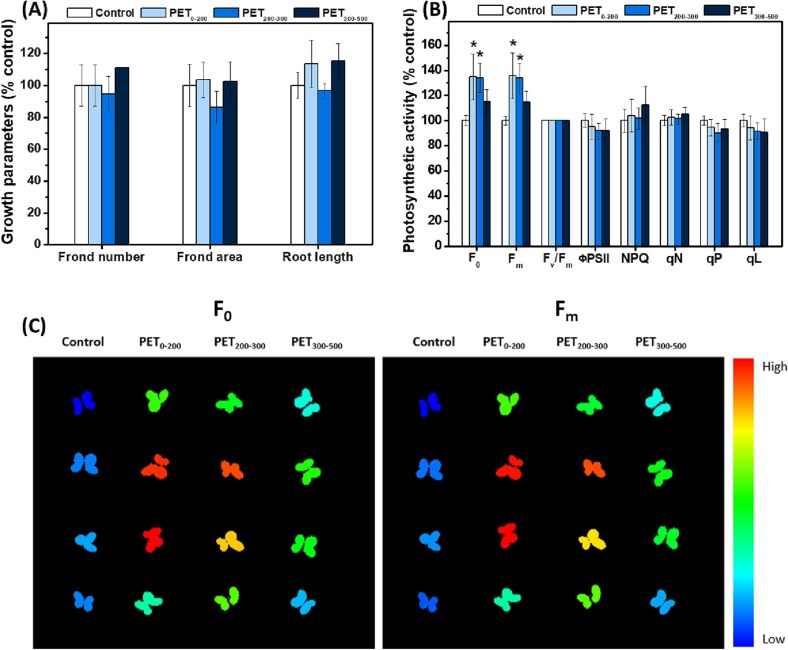

The effects of different-sized PET fragments on L. minor after 3-day exposure are shown in Fig. 3 and S2. In general, PET fragments of all sizes had no effect on the frond number, frond area, root length (Fig. 3A), and root cell viability (Fig. S2). However, owing to photosynthesis, the F0 and Fm of the PET0–200 and PET200–300 exposure groups significantly increased compared with those of the control group.

Fig. 3.

Effects of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) fragments on L. minor after 3-day exposure. (A) Effects of PET fragments on the frond number, growth rate based on the frond area, and root length of L. minor; (B) Effect of PET fragments on the photosynthesis of L. minor. “*” indicates a significant difference between the PET-exposed and control groups (p < 0.05); and (C) Visualization of photosynthesis using the F0 (minimum fluorescence in the dark-adapted state) and Fm (maximum fluorescence in the dark-adapted state) values of L. minor exposed to PET fragments measured using a closed FluorCam and analyzed using the FluorCam 7 software. Four replicates were analyzed in (A) and (B). Fig. 3(C) is created using F0 and Fm values presented in Fig. 3(B). The color scale provided to the right of (C) denotes the range of normalized values for each parameter from the lowest (blue) to the highest (red). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.2. Multigenerational effects of PET fragments on the growth of L. minor

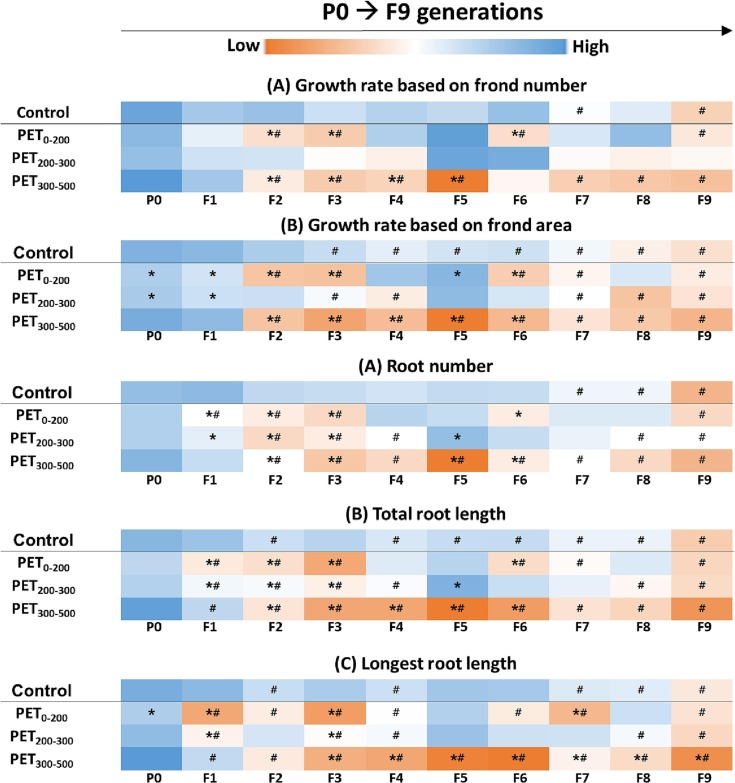

Compared with the acute test results, the growth parameters of each exposure group were significantly different from those of their P0 (*) generation or control groups of each generation (#) (Fig. 4 and S3). The growth rate based on the frond number of L. minor in the control group decreased significantly in F7 and F9 compared with that in P0, whereas the growth rate based on the frond number in the PET exposure group decreased significantly in F2. In subsequent generations, no effect on the growth rate based on the frond number of L. minor was observed for the PET200–300 group, and a decrease or no influence was evident when L. minor was exposed to PET0–200. However, plants exposed to PET300–500 showed a continuous decrease in the frond number from F2 onwards and reached the levels observed for the control or P0 (Figs. 4A and S3A). Furthermore, the growth rate based on the frond area of L. minor of the control group decreased significantly from F3 onwards. However, the growth rate decreased significantly from P0, F1, and F2 (Figs. 4B and S3B) for the PET0–200, PET200–300, and PET300–500 groups, respectively. The root-related parameters also demonstrated a similar trend. For instance, the root number of the control group was significantly lower in P0 than in F7, whereas significant differences were observed in F1 and F2 compared with the control and P0, respectively, when the plants were exposed to PET fragments (Figs. 4C and S3C). Furthermore, the total root length of the control group was significantly lower in P0 than in F2, whereas that of the PET fragment exposure groups significantly decreased from F1 onwards (Figs. 4D and S3D). The longest root length of plants in the control group was significantly shorter than that of plants in P0, whereas L. minor exposed to PET fragments showed significant differences in this parameter in P0 and F1 compared with those of the control group and P0, respectively (Figs. 4E and S3E).

Fig. 4.

Color table representing the toxic effects of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) fragments on the growth of L. minor in the multigenerational test. (A) Frond number, (B) growth rate based on frond area, (C) root number, (D) total root length, and (E) longest root length. The color represents the range of average values of each endpoint from the lowest (red) to the highest value (blue). “*” indicates a significant difference between the PET-exposed and control groups within the same generation (p < 0.05). “#” indicates a significant difference between the P0 generation and other generations (F1 to F9) within the same exposure group (p < 0.05). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

With the advancement of generations, the control group was more significantly affected than P0, which might be attributed to the damage caused by cutting the root before exposing plants of each generation to PET fragments. However, intergenerational differences were evident earlier in the PET-exposed plants than those in the control plants.

3.3. Multigenerational effects of PET fragments on the photosynthetic activity of L. minor

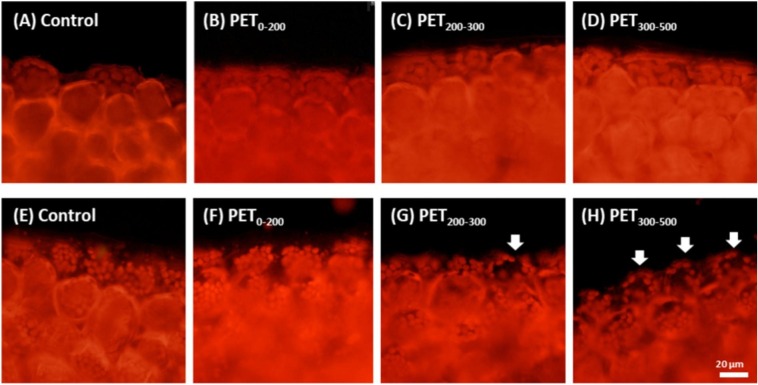

PET fragments affected photosynthesis (Figs. 5 and S4) and chloroplast distribution (Fig. 6 ) in L. minor, in the multigenerational test. In the control group, compared to that in P0, F0 was only significantly higher in F9. Conversely, when exposed to PET0–200 and PET300–500, significant changes in F0 were observed in F2 compared with that in the P0 or control group, whereas in the PET200–300 exposure group, F0 significantly increased in only F7 and F8 (Figs. 5A and S4A). Compared to those in P0, the Fm values in the control and PET fragment exposure groups significantly decreased in some generations only, and there was no significant difference in Fm values between the control and PET fragment exposure groups (Figs. 5B and S4B). In accordance with the changes in F0 and Fm, the Fv/Fm value of P0 was only significantly reduced in F8 and F9 compared to that of the control group. However, the Fv/Fm values of the exposure groups were significantly lower in F1 than those of the P0 or control group (Figs. 5C and S4C). The increase in F0 indicates that more energy is required for photosynthesis (Landi et al., 2013), whereas the decrease in Fm implies that irreversible damage has occurred to the PSII reaction center or antenna (Baker, 2008; Landi et al., 2013). Fv/Fm is an effective parameter for evaluating photosynthetic activity, which is generally reduced under stress (Baker, 2008; Landi et al., 2013).

Fig. 5.

Color table representing the toxic effects of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) fragments on the photosynthetic activity of L. minor in the multigenerational test. (A) F0 (minimum fluorescence in the dark-adapted state); (B) Fm (maximum fluorescence in the dark-adapted state); (C) Fv/Fm ([Fm—F0]/Fm, maximum PSII quantum yield); (D) ΦPSII (effective PSII quantum yield); (E) NPQ (steady-state non-photochemical quenching); (F) qN (coefficient of non-photochemical quenching in the steady-state); (G) qP (coefficient of photochemical quenching in the steady-state); and (H) qL (fraction of PSII centers that are “open”; “open” implies that the primary quinone acceptor of PSII is oxidized). The color represents the range of average values of each endpoint from the lowest (red) to the highest (blue) values. “*” denotes significant differences between the PET-exposed and control groups within the same generation. “#” denotes significant differences between the P0 generations within the same exposure group. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 6.

Chloroplast distribution in the fronds of L. minor after (A-D) 3-day exposure duration in the acute test and (E-H) 7-day exposure duration in the multigenerational test. White arrows indicate abnormal distribution of chloroplast. Disturbance in chloroplast distribution was not observed in the acute test; however, slight and notable disturbances were observed in the PET200–300 and PET300–500 exposure groups, respectively.

Our results showed that F0 significantly increased, Fm slightly decreased, and Fv/Fm significantly decreased in the PET fragment exposure groups compared with those in the control group. According to previous studies, ΦPSII is more sensitive to stress than Fv/Fm (Landi et al., 2013), which is consistent with our findings. Furthermore, ΦPSII showed a decreasing trend from F2 onwards in the control group, whereas the PET exposure groups showed significant differences in F1 (Figs. 5D and S4D). Both NPQ and qN are non-photochemistry indicators and increase under stress (Horton and Ruban, 1992). The NPQ value of the control group did not significantly change with generation. In contrast, significant differences in NPQ values were observed among early generations in the PET fragment exposure groups (Figs. 5E and S4E). The qN value of the control group was significantly lower in F2, F4, F8, and F9 than in P0. However, significant differences in P0 and F1 were observed in the PET exposure groups compared with those in the control group and P0, respectively (Figs. 5F and S4F). In addition, both qP and qL are photochemistry indicators that decrease under stress (Horton and Ruban, 1992). Herein, qP did not change significantly in both the control and PET fragment exposure groups (Figs. 5G and S4G). However, in the control group, the qL value in F3 was significantly lower than that in P0, whereas the PET fragment exposure groups showed significant changes in F1 compared with those in P0 and the control group (Figs. 5H and S4H).

Compared with the control, significant changes in NPQ and qN values in P0 indicated that PET affected the photosynthesis of L. minor in P0, whereas the decrease in NPQ of F3 was probably caused by the decrease in the PSII quantum yield (Fv/Fm and ΦPSII) and photochemistry (qP and qL). The decrease in qP and qL values might have resulted from the decrease in the PSII quantum yield (Fv/Fm and ΦPSII). Considering the results of the multigenerational test for L. minor, among all photosynthetic parameters, Fv/Fm, ΦPSII, and qL were relatively sensitive to PET, whereas NPQ and qP were relatively insensitive. In addition, slight disturbances in chloroplast distribution were observed in the PET200–300 exposure group, whereas considerable disturbances were observed in the PET300–500 exposure group (Fig. 6).

4. Discussion

4.1. Acute effects of PET fragments on L. minor

F0 is an indicator of sensitivity to plant stress and chlorophyll content and can be used to evaluate the relative size of PSII antennae. Thus, an increase in F0 implies that more energy is required for photosynthesis (Baker, 2008; Landi et al., 2013). However, compared with that of the control, the Fv/Fm value of the PET fragment exposure groups was not affected, implying that the increase in Fm could be attributed to an increase in F0. A previous study reported that exposure to high concentrations of MPs alters chlorophyll and protein composition, reduces the chlorophyll content, and inhibits the formation of chloroplasts and photosystems (Yu et al., 2020). Therefore, high exposure concentration of PET fragments in the acute assay (500 mg/L) caused adverse impacts on the F0 and Fm state in L. minor.

In our study, the PET fragments did not have negative effects on L. minor growth parameters even at a high exposure concentration of PET fragments (500 mg/L). According to previous studies, MPs negligibly or limitedly affected the growth of duckweed (L. minor and Spirodela polyrhiza) during short-term exposure periods (5–7 days) (Dovidat et al., 2020; Kalčíková et al., 2020, Kalčíková et al., 2017; Mateos-Cárdenas et al., 2019; Rozman et al., 2021) despite their adsorption on the roots and fronds. Similar to our results, Rozman et al. (2021) reported no growth inhibition of duckweed after four days of exposure to PET fragments (211.8 ± 51.7 μm) obtained from bottles. Therefore, the negligible acute toxicity of PET fragments on the growth (Fig. 3A), some parameters of photosynthetic activity (Fv/Fm, ΦPSII, NPQ, qN, qP, and qL) (Fig. 3B), and distribution of chloroplasts (Figs. 6A to D) can be attributed to the short exposure duration.

4.2. Multigenerational effects of PET fragments on L. minor

In this study, we observed that long-term exposure of L. minor to PET fragments can alter photosynthetic activity or chloroplast distribution, and, therefore, cause growth inhibition in the multigenerational study. Although some ecotoxic mechanisms of PET fragments remained unclear, our study found that physical damage to L. minor was not related to the phytotoxicity of PET fragments (Figs. S5 and S6). Toxic effects in L. minor may involve reactive oxygen species (ROS) or leachable chemicals from PET. For instance, chloroplast distribution is used for evaluating light stress (Kasahara et al., 2002) or chemical stress (Samardakiewicz et al., 2015), and is also related to ROS (Samardakiewicz et al., 2015). In addition, MP exposure results in altered activities of antioxidant enzymes (Jiang et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2022). Previous studies have also reported that oxidative damage decreases with a decrease in the MP size (Jiang et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020). Therefore, the adverse effects of PET0–200 on L. minor were greater than that of PET200–300 considering the size of PET fragments. Jiang et al. (2019) reported that the effect of MPs on biomass was greater in the 5-μm MP exposure group, whereas the effects of ROS and genotoxicity were more severe in the 100-nm exposure group in broad bean (Vicia faba) exposed to 10 mg/L, 50 mg/L, and 150 mg/L of 100 nm and 5 μm polystyrene suspensions for 48 h. Li et al. (2020) found that, when cucumber (Cucumis sativus) was exposed to 50 mg/L of 100 nm, 300 nm, 500 nm, and 700 nm polystyrene in Hoagland nutrient solution for 65 d, the ROS levels and antioxidant enzyme activities increased with an increase in MP size; the aboveground biomass was significantly affected only in the 300-nm MP exposure group; however, no effect was observed on belowground biomass. In addition, significant effects on the chlorophyll content, carotenoids, and photosynthesis were observed in the 100-nm and 700-nm MP exposure groups.

Another potential toxic mechanism may be related to leachable compounds from PET. Various additives, such as flame retardants, antioxidants, stabilizers, plasticizers, and catalysts, are added to plastic products to improve their quality, processability, physical properties, and long-term stability (Lithner et al., 2009). Additives are also added during PET bottle production, and some chemicals, such as dimethyl phthalate, diethyl phthalate, diisobutyl phthalate, di-n-hexyl phthalate, benzyl butyl phthalate, di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate, dioctyl phthalate, and d-Limonene, have been detected in PET bottle leachate (Heindler et al., 2017; Zimmermann et al., 2019). These additives might have adverse effects on L. minor following long-term exposure.

The effect of PET300–500 fragments on L. minor was greater than that of smaller-sized fragments, although the effects on different endpoints varied slightly. Previous studies have compared the effects of different-sized MPs on both aquatic and terrestrial plants exposed to liquid matrices (Bosker et al., 2019; Dovidat et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020; van Weert et al., 2019). According to their results, some endpoints show a size-dependent trend (Bosker et al., 2019; Jiang et al., 2019), some exhibit no relationship with MP size (Bosker et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020), and some are not affected by MP size (Bosker et al., 2019; Dovidat et al., 2020). Bosker et al. (2019) reported that, when garden cress (Lepidium sativum) was exposed to MPs of sizes 50 nm, 500 nm, and 4800 nm on filter paper, germination decreased after 8 h with an increase in the size; however, no significant difference was observed after 24 h. Furthermore, the root growth of plants exposed to MPs of sizes 50 nm, 500 nm, and 4800 nm showed significant increase, slight decrease, and no effect after 24 h, respectively; however, no effect was observed after 48 h and 72 h in any case. At 72-h exposure, the shoot growth of the 500-nm MP exposure group significantly decreased; however, none of the MPs affected the chlorophyll content.

In this study, the effects of PET fragments on 10 generations (P0 to F9 generations) of L. minor were studied. Although negative effects were observed in both the control and PET exposure groups, the effects occurred earlier in the PET exposure groups. Several studies have been conducted on the general ecotoxic effects of MPs on several organisms, such as soil nematodes (Zhao et al., 2017), water fleas (Liu et al., 2020; Martins and Guilhermino, 2018; Schür et al., 2020), fish (Wang et al., 2019), marine copepods (Zhang et al., 2019), and barnacles (Yu and Chan, 2020). In general, multigeneration tests were conducted up to a maximum of four generations (Martins and Guilhermino, 2018; Schür et al., 2020), and some were conducted only up to two generations (Wang et al., 2019; Yu and Chan, 2020; Zhao et al., 2017). Under continuous exposure to MPs, increasingly severe adverse effects were observed on the test organisms (Liu et al., 2020; Martins and Guilhermino, 2018; Schür et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2019). However, the organisms gradually recovered (Martins and Guilhermino, 2018; Ren et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2017) under recovery conditions. Only one study showed that the adverse effects in F1 were more severe than those in the maternal group under recovery conditions (Yu and Chan, 2020). Thus, our results suggested that PET MP fragments would have a multigenerational impact on L. minor and other organisms.

5. Conclusions

To verify the effects of PET MP fragments obtained from PET bottles on L. minor, acute and multigenerational tests were conducted using PET fragments of size ranges 0–200, 200–300, and 300–500 μm, and their effects on L. minor growth and photosynthesis were investigated. The acute test results demonstrated that PET0–200 and PET200–300 negatively affected photosynthesis (F0 and Fm) but did not affect the growth of L. minor. The general effects increased with a decrease in MP size, which might be attributed to ROS generation. In the acute test, the toxicity of smaller-sized PET fragments (PET0–200) to L. minor was greater than that of larger-sized PET fragments. In contrast, in the generational test, both L. minor growth and photosynthesis were negatively affected by exposure to PET fragments, and larger-sized PET fragments (PET300–500) were more toxic. We speculate that the negative effects of PET fragments on L. minor might have been related to leachable chemicals from PET or oxidative stress. Thus, both the limitations of the present study and necessity of future studies investigating this aspect were primarily related to the lack of visual evidence for qualitative or quantitative analyses of leachable chemicals from PET and ROS production.

To date, studies on the effects of MPs on aquatic plants have been limited compared with those examining the effects of MPs on other aquatic organisms, such as fish, shrimp, and invertebrates. Thus, further research on the impact of MPs derived from various products on aquatic plants is necessary as a variety of plastic products are used in daily life.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

R. Cui performed the experiments and drafted the first manuscript. J. I. Kwak performed the experiments. The project was planned and the manuscript was edited by Y.-J. An. The project was supervised by Y.-J. An.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This paper was supported by Konkuk University in 2022.

Editor: Kevin V Thomas

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162159.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary figures

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Andanson J.M., Kazarian S.G. In situ ATR-FTIR spectroscopy of poly(ethylene terephthalate) subjected to high-temperature methanol. Macromol. Symp. 2008;265:195–204. doi: 10.1002/masy.200850521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ASTM . 2012. Standard Guide for Conducting Static Toxicity Tests With Lemna gibba G3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baeza C., Cifuentes C., González P., Araneda A., Barra R. Experimental exposure of lumbricus terrestris to microplastics. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2020;231 doi: 10.1007/s11270-020-04673-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker N.R. Chlorophyll fluorescence: a probe of photosynthesis in vivo. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008;59:89–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer-Civiello A., Critchell K., Hoogenboom M., Hamann M. Input of plastic debris in an urban tropical river system. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019;144:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosker T., Bouwman L.J., Brun N.R., Behrens P., Vijver M.G. Microplastics accumulate on pores in seed capsule and delay germination and root growth of the terrestrial vascular plant Lepidium sativum. Chemosphere. 2019;226:774–781. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.03.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capozzi F., Carotenuto R., Giordano S., Spagnuolo V. Evidence on the effectiveness of mosses for biomonitoring of microplastics in fresh water environment. Chemosphere. 2018;205:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.04.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran P.L., Norris T., Ceccanese T., Walzak M.J., Helm P.A., Marvin C.H. Hidden plastics of Lake Ontario, Canada and their potential preservation in the sediment record. Environ. Pollut. 2015;204:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui R., Kwak J.I., An Y.-J. Acute and multigenerational effects of petroleum- and cellulose-based microfibers on growth and photosynthetic capacity of Lemna minor. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022;182 doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.113953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidat L.C., Brinkmann B.W., Vijver M.G., Bosker T. Plastic particles adsorb to the roots of freshwater vascular plant Spirodela polyrhiza but do not impair growth. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 2020;5:37–45. doi: 10.1002/lol2.10118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green D.S., Jefferson M., Boots B., Stone L. All that glitters is litter? Ecological impacts of conventional versus biodegradable glitter in a freshwater habitat. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021;402 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gür N., Türker O.C., Böcük H. Toxicity assessment of boron (B) by Lemna minor L. and Lemna gibba L. and their possible use as model plants for ecological risk assessment of aquatic ecosystems with boron pollution. Chemosphere. 2016;157:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.04.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haave M., Lorenz C., Primpke S., Gerdts G. Different stories told by small and large microplastics in sediment - first report of microplastic concentrations in an urban recipient in Norway. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019;141:501–513. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heindler F.M., Alajmi F., Huerlimann R., Zeng C., Newman S.J., Vamvounis G., van Herwerden L. Toxic effects of polyethylene terephthalate microparticles and di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate on the calanoid copepod, Parvocalanus crassirostris. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017;141:298–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton P., Ruban A.V. Regulation of photosystem II. Photosynth. Res. 1992;34:375–385. doi: 10.1007/BF00029812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICC The International Coastal cleanup 2021 Report: We clean on. 2021. https://oceanconservancy.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/2020-ICC-Report_Web_FINAL-0909.pdf

- Imhof H.K., Laforsch C., Wiesheu A.C., Schmid J., Anger P.M., Niessner R., Ivleva N.P. Pigments and plastic in limnetic ecosystems: a qualitative and quantitative study on microparticles of different size classes. Water Res. 2016;98:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISO . 2005. Water Quality — Determination of the Toxic Effect of Water Constituents and Waste Water on Duckweed (Lemna minor) — Duckweed Growth Inhibition Test. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ISO . 2017. Water Quality -- Determination of the Growth Inhibition Effects of Waste Waters, Natural Waters and Chemicals on the Duckweed Spirodela polyrhiza -- Method Using a Stock Culture Independent Microbiotest. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jemec Kokalj A., Kuehnel D., Puntar B., Žgajnar Gotvajn A., Kalčikova G. An exploratory ecotoxicity study of primary microplastics versus aged in natural waters and wastewaters. Environ. Pollut. 2019;254 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.112980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji L.-N. Study on preparation process and properties of polyethylene terephthalate (pet) Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013;312:406–410. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.312.406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y., Wang C., Wang Y., Fu L., Man M., Chen L. Realistic polyethylene terephthalate nanoplastics and the size- and surface coating-dependent toxicological impacts on zebrafish embryos. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2020;7:2313–2324. doi: 10.1039/d0en00464b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Chen H., Liao Y., Ye Z., Li M., Klobučar G. Ecotoxicity and genotoxicity of polystyrene microplastics on higher plant Vicia faba. Environ. Pollut. 2019;250:831–838. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalčíková G. Aquatic vascular plants – a forgotten piece of nature in microplastic research. Environ. Pollut. 2020;262 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalčíková G., Žgajnar Gotvajn A., Kladnik A., Jemec A. Impact of polyethylene microbeads on the floating freshwater plant duckweed Lemna minor. Environ. Pollut. 2017;230:1108–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalčíková G., Skalar T., Marolt G., Jemec Kokalj A. An environmental concentration of aged microplastics with adsorbed silver significantly affects aquatic organisms. Water Res. 2020;175 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara M., Kagawa T., Oikawa K., Suetsugu N., Miyao M., Wada M. Chloroplast avoidance movement reduces photodamage in plants. Nature. 2002;420:829–832. doi: 10.1038/nature01213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak J.I., Park J.-W., An Y.-J. Effects of silver nanowire length and exposure route on cytotoxicity to earthworms. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017;24:14516–14524. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-9054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landi M., Remorini D., Pardossi A., Guidi L. Purple versus green-leafed Ocimum basilicum: which differences occur with regard to photosynthesis under boron toxicity? J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2013;176:942–951. doi: 10.1002/jpln.201200626. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtiniemi M., Hartikainen S., Näkki P., Engström-Öst J., Koistinen A., Setälä O. Size matters more than shape: ingestion of primary and secondary microplastics by small predators. Food Webs. 2018;17 doi: 10.1016/j.fooweb.2018.e00097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Li R., Li Q., Zhou J., Wang G. Physiological response of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) leaves to polystyrene nanoplastics pollution. Chemosphere. 2020;255 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lithner D., Damberg J., Dave G., Larsson Å. Leachates from plastic consumer products - screening for toxicity with Daphnia magna. Chemosphere. 2009;74:1195–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Cai M., Wu D., Yu P., Jiao Y., Jiang Q., Zhao Y. Effects of nanoplastics at predicted environmental concentration on Daphnia pulex after exposure through multiple generations. Environ. Pollut. 2020;256 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maaß S., Daphi D., Lehmann A., Rillig M.C. Transport of microplastics by two collembolan species. Environ. Pollut. 2017;225:456–459. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins A., Guilhermino L. Transgenerational effects and recovery of microplastics exposure in model populations of the freshwater cladoceran Daphnia magna Straus. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;631–632:421–428. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateos-Cárdenas A., Scott D.T., Seitmaganbetova G.van, van P., John O.H., Marcel A.K.J. Polyethylene microplastics adhere to Lemna minor (L.), yet have no effects on plant growth or feeding by Gammarus duebeni (Lillj.) Sci. Total Environ. 2019;689:413–421. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.06.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAPCOR . 2017. Report on Postconsumer PET Container Recycling Activity in 2017. [Google Scholar]

- OECD . 2006. OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals No. 221 Lemna sp. Growth Inhibition Test. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park A., Kim Y.J., Choi E.M., Brown M.T., Han T. A novel bioassay using root re-growth in Lemna. Aquat. Toxicol. 2013;140–141:415–424. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parolini M., De Felice B., Gazzotti S., Annunziata L., Sugni M., Bacchetta R., Ortenzi M.A. Oxidative stress-related effects induced by micronized polyethylene terephthalate microparticles in the Manila clam. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health - Part A Curr. Issues. 2020;83:168–179. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2020.1737852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parolini M., Ferrario C., De Felice B., Gazzotti S., Bonasoro F., Candia Carnevali M.D., Ortenzi M.A., Sugni M. Interactive effects between sinking polyethylene terephthalate (PET) microplastics deriving from water bottles and a benthic grazer. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020;398 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plastics Europe . 2019. Plastics - The Facts 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad S.G., De A., De U. Structural and optical investigations of radiation damage in transparent PET ppolymer films. Int. J. Spectrosc. 2011;2011:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2011/810936. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman W.M.N.W.A., Wahab A.F.A. Green pavement using recycled polyethylene terephthalate (PET) as partial fine aggregate replacement in modified asphalt. Procedia Eng. 2013;53:124–128. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2013.02.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ren H.Y., Liu B.F., Kong F., Zhao L., Xie G.J., Ren N.Q. Enhanced lipid accumulation of green microalga Scenedesmus sp. by metal ions and EDTA addition. Bioresour. Technol. 2014;169:763–767. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.06.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues M.O., Abrantes N., Gonçalves F.J.M., Nogueira H., Marques J.C., Gonçalves A.M.M. Spatial and temporal distribution of microplastics in water and sediments of a freshwater system (Antuã River, Portugal) Sci. Total Environ. 2018;633:1549–1559. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.03.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Hernández A.G., Muñoz-Tabares J.A., Aguilar-Guzmán J.C., Vazquez-Duhalt R. A novel and simple method for polyethylene terephthalate (PET) nanoparticle production. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2019;6:2031–2036. doi: 10.1039/c9en00365g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rozman U., Turk T., Skalar T., Zupančič M., Čelan Korošin N., Marinšek M., Olivero-Verbel J., Kalčíková G. An extensive characterization of various environmentally relevant microplastics – material properties, leaching and ecotoxicity testing. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;773 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- S&. P Global . IHS Markit; 2021. PET polymer: chemical economics handbook.https://ihsmarkit.com/products/pet-polymer-chemical-economics-handbook.html (Published November 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Samardakiewicz S., Krzeszowiec-Jeleń W., Bednarski W., Jankowski A., Suski S., Gabryś H., Woźny A. Pb-induced avoidance-like chloroplast movements in fronds of Lemna trisulca L. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schür C., Zipp S., Thalau T., Wagner M. Microplastics but not natural particles induce multigenerational effects in Daphnia magna. Environ. Pollut. 2020;260 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha V., Patel M.R., Patel J.V. Pet waste management by chemical recycling: a review. J. Polym. Environ. 2010;18:8–25. doi: 10.1007/s10924-008-0106-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tournier V., Topham C.M., Gilles A., et al. An engineered PET depolymerase to break down and recycle plastic bottles. Nature. 2020;580:216–219. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USEPA . 2012. Ecological Effects Test Guidelines OCSPP 850.4400: Aaquatic Plant Toxicity Test Using Lemna spp. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Li Y., Lu L., Zheng M., Zhang X., Tian H., Wang W., Ru S. Polystyrene microplastics cause tissue damages, sex-specific reproductive disruption and transgenerational effects in marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) Environ. Pollut. 2019;254 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber A., Scherer C., Brennholt N., Reifferscheid G., Wagner M. PET microplastics do not negatively affect the survival, development, metabolism and feeding activity of the freshwater invertebrate Gammarus pulex. Environ. Pollut. 2018;234:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Weert S., Redondo-Hasselerharm P.E., Diepens N.J., Koelmans A.A. Effects of nanoplastics and microplastics on the growth of sediment-rooted macrophytes. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;654:1040–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P., Tang Y., Dang M., Wang S., Jin H., Liu Y., Jing H., Zheng C., Yi S., Cai Z. Spatial-temporal distribution of microplastics in surface water and sediments of Maozhou River within Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;717 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G.-L., Zheng M.M., Liao H.-M., Tan A.-J., Feng D., Lv S.-M. Influence of cadmium and microplastics on physiological responses, ultrastructure and rhizosphere microbial community of duckweed. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022;243 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.114011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S.P., Chan B.K.K. Intergenerational microplastics impact the intertidal barnacle amphibalanus amphitrite during the planktonic larval and benthic adult stages. Environ. Pollut. 2020;267 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Zhang X., Hu J., Peng J., Qu J. Ecotoxicity of polystyrene microplastics to submerged carnivorous Utricularia vulgaris plants in freshwater ecosystems. Environ. Pollut. 2020;265 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zbyszewski M., Corcoran P.L. Distribution and degradation of fresh water plastic particles along the beaches of Lake Huron, Canada. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2011;220:365–372. doi: 10.1007/s11270-011-0760-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K., Su J., Xiong X., Wu X., Wu C., Liu J. Microplastic pollution of lakeshore sediments from remote lakes in Tibet plateau, China. Environ. Pollut. 2016;219:450–455. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Jeong C.B., Lee J.S., Wang D., Wang M. Transgenerational proteome plasticity in resilience of a marine copepod in response to environmentally relevant concentrations of microplastics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019;53:8426–8436. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b02525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Qu M., Wong G., Wang D. Transgenerational toxicity of nanopolystyrene particles in the range of μg L-1 in the nematode: Caenorhabditis elegans. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2017;4:2356–2366. doi: 10.1039/c7en00707h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann L., Dierkes G., Ternes T.A., Völker C., Wagner M. Benchmarking the in vitro toxicity and chemical composition of plastic consumer products. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019;53 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b02293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.