Abstract

Background

To increase people’s access to rehabilitation services, particularly in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic, we need to explore how the delivery of these services can be adapted. This includes the use of home‐based rehabilitation and telerehabilitation. Home‐based rehabilitation services may become frequently used options in the recovery process of patients, not only as a solution to accessibility barriers, but as a complement to the usual in‐person inpatient rehabilitation provision. Telerehabilitation is also becoming more viable as the usability and availability of communication technologies improve.

Objectives

To identify factors that influence the organisation and delivery of in‐person home‐based rehabilitation and home‐based telerehabilitation for people needing rehabilitation.

Search methods

We searched PubMed, Global Health, the VHL Regional Portal, Epistemonikos, Health Systems Evidence, and EBM Reviews as well as preprints, regional repositories, and rehabilitation organisations websites for eligible studies, from database inception to search date in June 2022.

Selection criteria

We included studies that used qualitative methods for data collection and analysis; and that explored patients, caregivers, healthcare providers and other stakeholders’ experiences, perceptions and behaviours about the provision of in‐person home‐based rehabilitation and home‐based telerehabilitation services responding to patients’ needs in different phases of their health conditions.

Data collection and analysis

We used a purposive sampling approach and applied maximum variation sampling in a four‐step sampling frame. We conducted a framework thematic analysis using the CFIR (Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research) framework as our starting point. We assessed our confidence in the findings using the GRADE‐CERQual (Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research) approach.

Main results

We included 223 studies in the review and sampled 53 of these for our analysis. Forty‐five studies were conducted in high‐income countries, and eight in low‐and middle‐income countries. Twenty studies addressed in‐person home‐based rehabilitation, 28 studies addressed home‐based telerehabilitation services, and five studies addressed both modes of delivery. The studies mainly explored the perspectives of healthcare providers, patients with a range of different health conditions, and their informal caregivers and family members.

Based on our GRADE‐CERQual assessments, we had high confidence in eight of the findings, and moderate confidence in five, indicating that it is highly likely or likely respectively that these findings are a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest. There were two findings with low confidence.

High and moderate confidence findings

Home‐based rehabilitation services delivered in‐person or through telerehabilitation

Patients experience home‐based services as convenient and less disruptive of their everyday activities. Patients and providers also suggest that these services can encourage patients' self‐management and can make them feel empowered about the rehabilitation process. But patients, family members, and providers describe privacy and confidentiality issues when services are provided at home. These include the increased privacy of being able to exercise at home but also the loss of privacy when one’s home life is visible to others.

Patients and providers also describe other factors that can affect the success of home‐based rehabilitation services. These include support from providers and family members, good communication with providers, the requirements made of patients and their surroundings, and the transition from hospital to home‐based services.

Telerehabilitation specifically

Patients, family members and providers see telerehabilitation as an opportunity to make services more available. But providers point to practical problems when assessing whether patients are performing their exercises correctly. Providers and patients also describe interruptions from family members.

In addition, providers complain of a lack of equipment, infrastructure and maintenance and patients refer to usability issues and frustration with digital technology. Providers have different opinions about whether telerehabilitation is cost‐efficient for them. But many patients see telerehabilitation as affordable and cost‐saving if the equipment and infrastructure have been provided.

Patients and providers suggest that telerehabilitation can change the nature of their relationship. For instance, some patients describe how telerehabilitation leads to easier and more relaxed communication. Other patients describe feeling abandoned when receiving telerehabilitation services.

Patients, family members and providers call for easy‐to‐use technologies and more training and support. They also suggest that at least some in‐person sessions with the provider are necessary. They feel that telerehabilitation services alone can make it difficult to make meaningful connections. They also explain that some services need the provider’s hands. Providers highlight the importance of personalising the services to each person’s needs and circumstances.

Authors' conclusions

This synthesis identified several factors that can influence the successful implementation of in‐person home‐based rehabilitation and telerehabilitation services. These included factors that facilitate implementation, but also factors that can challenge this process. Healthcare providers, program planners and policymakers might benefit from considering these factors when designing and implementing programmes.

Keywords: Humans, Caregivers, COVID-19, Family, Health Personnel, Pandemics

Plain language summary

Factors that influence the provision of home‐ based rehabilitation services for people needing rehabilitation: a qualitative evidence synthesis

The aim of this Cochrane qualitative evidence synthesis was to explore factors that influence rehabilitation services that are delivered in people’s own homes. The synthesis looked at services that were delivered in person as well as services that were delivered through telerehabilitation. To answer this question, we analysed 53 qualitative studies.

Key messages

Home‐based rehabilitation, delivered in‐person or through telerehabilitation, can be experienced as more accessible and more convenient than facility‐based services. Patients, providers and family members also describe how home‐based services can change the nature of their relationships and can have practical and resource implications that can be both positive and negative.

What was studied in this synthesis?

The COVID‐19 pandemic has led to a stronger focus on home‐based healthcare. This includes the delivery of home‐based rehabilitation services delivered in person or using telerehabilitation. Home‐based rehabilitation services may become a common option in the recovery process of patients, either instead of facility‐based services or as a complement to these services. Telerehabilitation is also becoming more common as people’s access to digital technologies increases.

What are the main findings of this synthesis?

We analysed 53 qualitative studies where patients received rehabilitation services in their own homes. In some of the studies, healthcare providers delivered the services in person. In the other studies, providers delivered the services through telerehabilitation using digital technologies. The studies explored the views and experiences of patients, families and healthcare providers. Most of the studies were from high‐income countries.

Our findings highlight several factors that can influence the organisation and delivery of home‐based rehabilitation. We have moderate to high confidence in the following findings.

Home‐based rehabilitation services delivered in‐person or through telerehabilitation

Patients experience home‐based services as convenient and less disruptive of their everyday activities. Patients and providers also suggest that these services can encourage patients' self‐management and can make them feel empowered about the rehabilitation process. But patients, family members, and providers describe privacy and confidentiality issues when services are provided at home. These include the increased privacy of being able to exercise at home but also the loss of privacy when one’s home life is visible to others.

Patients and providers also describe other factors that can affect the success of home‐based rehabilitation services. These include support from providers and family members, good communication with providers, the requirements made of patients and their surroundings, and the transition from hospital to home‐based services.

Telerehabilitation specifically

Patients, family members and providers see telerehabilitation as an opportunity to make services more available. But providers point to practical problems when assessing whether patients are performing their exercises correctly. Providers and patients also describe interruptions from family members.

In addition, providers complain of a lack of equipment, infrastructure and maintenance and patients refer to usability issues and frustration with digital technology. Providers have different opinions about whether telerehabilitation is cost‐efficient for them. But many patients see telerehabilitation as affordable and cost‐saving if the equipment and infrastructure has been provided.

Patients and providers suggest that telerehabilitation can change the nature of their relationship. For instance, some patients describe how telerehabilitation leads to easier and more relaxed communication. Other patients describe feeling abandoned when receiving telerehabilitation services.

Patients, family members and providers call for easy‐to‐use technologies and more training and support. They also suggest that at least some in‐person sessions with the provider are necessary. They feel that telerehabilitation services alone can make it difficult to make meaningful connections. They also explain that some services need the provider’s hands. Providers highlight the importance of personalising the services to each person’s needs and circumstances.

How up to date is this synthesis?

We searched for studies that had been published up to 16 June 2022.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of qualitative findings.

| Summary of review finding | Studies contributing to the review finding | GRADE‐CERQual assessment of confidence in the evidence | Explanation of GRADE‐CERQual assessment |

| Perceptions about rehabilitation services delivered at patients´ homes through in‐person encounters or via telerehabilitation | |||

| Finding 1. Patients and caregivers receiving and healthcare providers delivering telerehabilitation services perceived at least some in‐person home encounters as necessary. They felt that telerehabilitation services alone lost the rapport of social interaction and the opportunity to make meaningful connections. They also pointed out that some types of services provided with the hands could not be delivered using telerehabilitation (moderate confidence finding). | Brouns 2018; Damhus 2018; Dennett 2020; Gélinas‐Bronsard 2019; Hale Gallardo 2020; Hoaas 2016; Lawson 2020; O'Shea 2020; Ownsworth 2020; Palazzo 2016; Pekmezaris 2020; Saywell 2015; Shulver 2016; Van der Meer 2020 | Moderate confidence | Downgraded because we had minor concerns regarding methodological limitations and relevance; no/very minor concerns regarding coherence and adequacy |

| Finding 2. Patients and healthcare providers described how in‐person home‐based rehabilitation and telerehabilitation encouraged patients' self‐management and made them feel empowered about the rehabilitation process. Patients become active contributors and shaped the process and its pace according to their needs. This was seen to facilitate the achievement of final results, whatever the goal that rehabilitation aimed to achieve (high confidence finding). | Argent 2018; Bodker 2015; Dennett 2020; Dinesen 2019; Dubouloz 2004; Edbrooke 2020; Emmerson 2018; Folan 2015; Gélinas‐Bronsard 2019; Hoaas 2016; Mohd Nordin 2014; Ng 2013; Nordin 2017; O'Shea 2020; Ownsworth 2020; Pekmezaris 2020; Pinto 2014; Ranaldi 2018; Randström 2012; Shulver 2016; Sureshkumar 2016; Tsai 2016; Turner 2011; Van der Meer 2020. | High confidence | We had minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, and no/very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy, and relevance |

| Finding 3. Patients and healthcare providers appreciated how in‐person home‐based rehabilitation or telerehabilitation improved patient outcomes related to independence, overall functioning at home, and everyday use of assistive devices, which are facilitated by the interaction with the home environment implicit in these types of services (low confidence finding). | Bodker 2015; Borade 2019; Dennett 2020; Dubouloz 2004; Govender 2019; O'Shea 2020; Pinto 2014; Randstrom 2013 | Low confidence | Downgraded because we had no/very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, serious concerns regarding coherence, and moderate concerns regarding adequacy and relevance |

| Finding 4. Patients, caregivers and healthcare providers regarded the transition from the hospital to home as a challenging process given the lack of human and infrastructure resources available in the home setting. This may have an impact on the implementation of in‐person home‐based rehabilitation. | Govender 2019; HeydariKhayat 2020; Mohd Nordin 2014; Turner 2011; VanderVeen 2019 | Moderate confidence | Downgraded because we had moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations, minor concerns regarding coherence, and relevance, and no/very minor concerns regarding adequacy |

| Finding 5. Patients and healthcare providers described several factors that might affect patients’ motivation and engagement with telerehabilitation services, including support from healthcare providers or family members and other caregivers during sessions, good communication with the healthcare provider, what the exercise required from the patient and their surroundings, and the presence of comorbidities. | Bodker 2015; Brouns 2018; Dennett 2020; Dinesen 2019; Edbrooke 2020; Folan 2015; Hoaas 2016; Lawson 2020; O'Doherty 2013; O'Shea 2020; Palazzo 2016; Ranaldi 2018; Randström 2014; Saywell 2015; Stark 2019; Stuifbergen 2011; Teriö 2019; Van der Meer 2020; Vik 2009 | Moderate confidence | Downgraded because we had no/very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations and adequacy, moderate concerns regarding coherence, and minor concerns regarding relevance |

| Finding 6. Patients, caregivers, and providers described a number of privacy and confidentiality issues when services were provided at home. These included the increased privacy of being able to exercise at home but also the loss of privacy when elements of one’s home life were visible to others. | Bodker 2015; Brouns 2018; Dennett 2020; Gélinas‐Bronsard 2019; Hoaas 2016; Lawson 2020; Ng 2013; Ownsworth 2020; Oyesanya 2019; Palazzo 2016; Pekmezaris 2020; Randström 2012; Randstrom 2013; Randström 2014;Rietdijk 2020 | High confidence | We had no/very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations and coherence, and minor concerns regarding adequacy and relevance |

| Finding 7. Patients regarded in‐person home‐based rehabilitation and telerehabilitation services as convenient and less disruptive of everyday activities. | Govender 2019; Hale Gallardo 2020; HeydariKhayat 2020; Lawson 2020; Ownsworth 2020; Palmcrantz 2017; Pekmezaris 2020; Pinto 2014; Randström 2012; Randstrom 2013; Shulver 2017; Silveira 2019; Stark 2019; Tsai 2016; Tyagi 2018; Van der Meer 2020 | High confidence | We had no/very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, coherence, adequacy,and relevance |

| Finding 8. Patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers called for more training in the context of in‐person home‐based rehabilitation. | Govender 2019; O'Doherty 2013; Randström 2014; Schopfer 2020; Umb Carlsson 2019; VanderVeen 2019 | Low confidence | Downgraded because we had no/very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, minor concerns regarding coherence, serious concerns regarding adequacy, and moderate concerns regarding relevance |

| Perceptions about rehabilitation services delivered at home through telerehabilitation | |||

| Finding 9. Healthcare providers highlighted the importance of personalising the service to each patient’s needs and resources at home. | Bodker 2015; Damhus 2018; Dennett 2020; Edbrooke 2020; Lawson 2020; Ownsworth 2020; Shulver 2017; Silveira 2019; Tsai 2016 | High confidence | We had no/very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, coherence and adequacy, and minor concerns regarding relevance |

| Finding 10. Patients, caregivers, healthcare providers and other stakeholders described how telerehabilitation changed the nature of the patient‐provider relationship. This included overcoming physical barriers to communication and enabling quick responses to questions, creating a more relaxed environment for communication, and supporting shared decision making. Some patients described how telerehabilitation services allowed them to keep connected with their healthcare provider after being discharged from the hospital. However, other patients felt abandoned when receiving telerehabilitation services. | Argent 2018; Bodker 2015; Brouns 2018; Dennett 2020; Dinesen 2019; Emmerson 2018; Gélinas‐Bronsard 2019; Hale Gallardo 2020; Kamwesiga 2017; Lawson 2020; Malmberg 2018; Nordin 2017; Ownsworth 2020; Palazzo 2016; Palmcrantz 2017; Shulver 2017; Stuifbergen 2011; Tsai 2016; Van der Meer 2020 | High confidence | We had minor concerns regarding methodological limitations and relevance, and no/very minor concerns regarding coherence and adequacy |

| Finding 11. Healthcare providers and patients described some aspects of telerehabilitation services at home as challenging. Healthcare providers described problems in assessing patients, their environment, and whether they were performing exercises correctly. Providers and patients also emphasised the need for a quiet place during telerehabilitation sessions and described challenges tied to interruptions from family members. | Argent 2018; Bodker 2015; Damhus 2018; Lawson 2020; Mendell 2019; Ownsworth 2020; Palazzo 2016; Rietdijk 2020; Shulver 2017; Silveira 2019; Sureshkumar 2016; Tsai 2016; Tyagi 2018 | High confidence | We had no/very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, coherence and adequacy, and minor concerns regarding relevance |

| Finding 12. Patients, caregivers, healthcare providers and other stakeholders regarded telerehabilitation as an opportunity to make rehabilitation services more accessible. | Argent 2018; Brouns 2018; Damhus 2018; Dennett 2020; Emmerson 2018; Folan 2015; Gélinas‐Bronsard 2019; Hale Gallardo 2020; Hoaas 2016; Lawson 2020; Malmberg 2018; O'Shea 2020; Ownsworth 2020; Oyesanya 2019; Palmcrantz 2017; Rietdijk 2020; Saywell 2015; Shulver 2017; Tyagi 2018; Van der Meer 2020 | High confidence | We had no/very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, coherence, adequacy and relevance |

| Finding 13. Healthcare providers and policymakers highlighted the need for adequate equipment, infrastructure and maintenance both on the provider side and the patient side but described how these needs were not always met. They described challenges including a lack of resources and investment, a lack of awareness around the resources needed, and rapid advances in technology that make technology rapidly obsolete. | Bodker 2015; Brouns 2018; Gélinas‐Bronsard 2019; Hale Gallardo 2020; Lawson 2020; Mendell 2019; Ownsworth 2020; Oyesanya 2019; Palmcrantz 2017; Shulver 2016; Teriö 2019; Tyagi 2018; Van der Meer 2020 | Moderate confidence | Downgraded because we had no/very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, coherence, and adequacy, and moderate concerns regarding relevance |

| Finding 14. Patients and caregivers described many usability issues related to the device, the program or the application; they also emphasised the need for easy‐to‐use technologies that could be adapted to the patient’s individual needs. Patients and caregivers reported a lack of familiarity with, fear of or frustration with digital technology. Patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers called for more training and support in the use of these technologies. | Argent 2018; Bodker 2015; Brouns 2018; Damhus 2018; Emmerson 2018; Folan 2015; Gélinas‐Bronsard 2019; Hale Gallardo 2020; Hoaas 2016; Lawson 2020; Malmberg 2018; Mendell 2019; O'Shea 2020; Ownsworth 2020; Palazzo 2016; Palmcrantz 2017; Rietdijk 2020; Shulver 2016; Shulver 2017; Silveira 2019; Stuifbergen 2011; Sureshkumar 2016; Teriö 2019; Tsai 2016; Tyagi 2018; Van der Meer 2020 | Moderate confidence | Downgraded because we had minor concerns regarding methodological limitations and coherence, no/very minor concerns regarding adequacy, and moderate concerns regarding relevance |

| Finding 15. Healthcare providers differed in their views about whether telerehabilitation was cost‐efficient for them, but many patients encountered it as affordable and cost‐saving when the equipment and infrastructure have been provided. | Bodker 2015; Brouns 2018; Damhus 2018; Gélinas‐Bronsard 2019; Lawson 2020; Ownsworth 2020; Van der Meer 2020 | High confidence | We had no/very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, coherence and adequacy, and moderate concerns regarding relevance |

Background

Description of the topic

It is estimated that 15% of the world’s population live with disabilities, and that 2,4 billion people are in need of rehabilitation services (World Health Organization 2011; Negrini 2020a; Cieza 2021). Demographic changes, such as population growth, ageing, increased complexity and chronicity in diseases, and medical advances that preserve life (Gimigliano 2017), indicate that these figures will increase.

These global trends suggest that key indicators of a population’s health will not only be mortality and morbidity, but also functioning (Gimigliano 2017; Negrini 2020b). Healthcare services need to respond to the increased need for long‐term management of disabilities and chronic conditions by strengthening rehabilitation services (Skempes 2021).

Rehabilitation services target mobility, vision, hearing, and cognition, and contribute to optimizing function ability and well‐being across the continuum of acute, subacute, and long‐term care (Van Egmond 2018; EP and RMBA 2018; Gimigliano 2017; Meyer 2014). However, people do not always access the rehabilitation services they need.

According to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (World Health Organization 2001), contextual factors, including the physical, social and attitudinal environment in which people live and conduct their lives, can act as facilitators or barriers for receiving rehabilitation services (Mlenzana 2013; Gutenbrunner 2020b). This includes factors tied to the rehabilitation services themselves, such as users' access to healthcare providers and to information about services, providers’ skills and other attributes, and people’s confidence in these providers; as well as broader factors related to society's lack of awareness about disability and lack of economic resources.

During the 2020 COVID‐19 pandemic, people attempting to access rehabilitation services were facing additional challenges. Rehabilitation has in the present resource scarcity been perceived as ‘non‐essential’, and many have been cancelled or limited, for instance by limiting care to outpatient settings (Negrini 2020b). The lack of services obviously affects the well‐being and quality of life of people living with disabilities and imposes more burdens on a population that is already vulnerable. Some medical conditions can be aggravated by the lack of access to rehabilitation services. Critical situations have been reported for people with acute health conditions (e.g. stroke in adults), other conditions needing specialized inpatient rehabilitation services (e.g. spinal cord injuries, rare diseases, and musculoskeletal conditions) and long‐term assessment (Boldrini 2020; Dorjbal 2019).

To increase people’s access to rehabilitation services, there is a need to explore how the delivery of these services can be adapted, including through the use of home‐based rehabilitation and telerehabilitation (Brennan 2009). These strategies could help avoid the prolonged interruption of services when other modes of service delivery are limited or not possible, for example, due to natural disasters, geographic isolation or pandemics. Home‐based rehabilitation services may become the most frequently used option in the recovery process of patients, not only as an alternative to access barriers, but as a complement to the usual rehabilitation provision.

How the intervention might work

In‐person home‐based rehabilitation refers to the delivery of rehabilitation services with in‐person encounters provided where the patient lives, for instance at home or in nursing homes or long‐term care (Chi 2020). It is often a component of a broader community‐based rehabilitation process (Cobbing 2016), and one of the supportive tools that allow the continuation of care in a familiar living environment.

In‐person home‐based rehabilitation shares the same goals as other types of rehabilitation. It aims to let people resume their activities, improve their quality of life, reduce the burden of caregivers, and prevent complications and secondary conditions (Hotta 2015). Home‐based rehabilitation aims to provide the benefits of effective treatment to people with no access to in‐patient or facility‐based care, or might complement such care (Stolee 2012). In addition, home‐based rehabilitation focuses on improving people's participation in their own care and their ability to evaluate themselves and set goals for their recovery in the context of their own home. It can involve learning strategies for self‐management related to daily activities at home and in the community; receiving exercise training; exploring community services and facilities; dialogue with professionals; and participation in activities aimed at returning to work (Steihaug 2016).

The types of services that in‐person home‐based rehabilitation provides vary according to the person’s needs. These services can include, for instance, assessment of the home and the environment with modification of architectural barriers that may exist as well as the provision of assistive devices; home nursing and education for the person and their caregiver on topics such as hygiene, bladder and bowel management and skin care; social and psychological support for the emotional demands of the person and their family; primary care by general practitioners and therapists with services necessary for the maintenance of health, well‐being and the prevention of complications, as well as transition therapies towards more complex rehabilitation interventions (Rezaei 2019).

Two Cochrane Reviews have found that in‐person home‐based rehabilitation may be as effective as institutional‐based rehabilitation (Anderson 2017; Coupar 2012), while another, for breast cancer survivors, found that in‐person home‐based rehabilitation may be better than usual care for quality of life and may lead to a reduction in fatigue and anxiety, at least in the short term (Cheng 2017). Additionally, another Cochrane Review found that hospitalization at home for people recovering from stroke may lower the risk of living in an institutional setting at six months and may slightly improve patient satisfaction when compared to in‐hospital care (Gonçalves‐Bradley 2017).

Additional benefits of in‐person home‐based rehabilitation that have been reported include keeping people in a familiar environment; expanding access for people who would not otherwise receive care; aligning the rehabilitation process with each patient’s daily activities at their homes (Cobbing 2016; Housley 2016; Steihaug 2016); and reducing the burden and costs of travel, at least for the patient. However, some barriers to implementation have also been described, such as difficulties in patient adherence and requirements in logistics and human resources (Gelaw 2020; Kuo 2019; Widén 1998).

Telerehabilitation has been defined as the delivery of rehabilitation services where the patient lives via information and communication technologies (Brennan 2009). Telerehabilitation can provide many of the same services described for home‐based rehabilitation, thus providing assistance to homebound patients without the physical presence of a therapist or other healthcare provider (Agostini 2015).

Cochrane Reviews assessing the effectiveness of telerehabilitation for a range of conditions show mixed results. Telerehabilitation may be better than traditional in‐person services or standard care for a number of outcomes among people with multiple sclerosis (Khan 2015). For stroke patients, on the other hand, there may be no significant differences between telerehabilitation and standard delivery of rehabilitation (Laver 2020), while for people with chronic low‐back pain, the effects are largely uncertain due to very low‐certainty evidence (Saragiotto 2016).

Home‐based telerehabilitation shares some of the same potential advantages as in‐person home‐based rehabilitation. Both modes of service delivery allow people to stay in a familiar environment and can help align the rehabilitation process with people’s daily activities at home. In addition, home‐based telerehabilitation not only reduces the burden and costs of travel for the patient, but also for the healthcare provider (Kairy 2009; Peretti 2017). It can improve accessibility in remote places, where traditional rehabilitation services may not be easily accessible (Peretti 2017; Tyagi 2018), and can thus increase the frequency and intensity of care provided to patients and consequently to motivate improvements in their own home environment (Agostini 2015). Telerehabilitation programs can also potentially be adjusted to patients’ daily lives since restrictions on time or location are not always imposed, increasing people’s ability to attend work (Knudsen 2019).

However, certain disadvantages of home‐based telerehabilitation have been reported, including skepticism on the part of patients due to remote interaction with their physicians or rehabilitation professionals, equipment setup‐related difficulties, the limited scope of exercises, and the need for proper training and education of people involved (Peretti 2017; Tyagi 2018). Telerehabilitation and other telehealth services also require reliable access to equipment, electricity and internet, which can pose serious challenges, particularly in low resource or remote settings (Odendaal 2020).

Why is it important to do this review?

Many people eligible for rehabilitation experience restricted access to services. The COVID‐19 pandemic has worsened service availability and accordingly introduced growing burdens on patients, families and primary healthcare providers (Bettger 2020; Bittner 2020; Ceravolo 2020a; Negrini 2020b). The restrictions that have been imposed to contain the spread of infection are limiting access to many healthcare services, including rehabilitation. Consequences might be long‐lasting, increasing disabling conditions and hindering illness recovery in the population.

The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes the importance of guaranteeing equitable access to quality health services (World Health Organization 2019). As part of this goal, the WHO and the UN have called for the increased use and affordability of information and communication technology (ICT), including telerehabilitation, for people with disabilities. They have also called for more research that can support the quality of rehabilitation services (Clark 2006; World Health Organization 2011).

The identification of factors influencing the organisation and delivery of in‐person home‐based rehabilitation and home‐based telerehabilitation for people in need of rehabilitation in pandemic and non‐pandemic contexts is a relevant issue to investigate. By identifying these factors, we can more easily identify strategies that can improve the provision of these services in ways that are likely to be experienced as acceptable, feasible and equitable by patients, healthcare providers and other stakeholders.

How this review might inform or supplement what is already known in this area

As described above, several systematic reviews have assessed the efficacy and effectiveness of in‐person home‐based rehabilitation and home‐based telerehabilitation services for different patient groups (Anderson 2017; Cheng 2017; Coupar 2012; Gonçalves‐Bradley 2017; Khan 2015; Laver 2020; Saragiotto 2016). In addition, in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic, a series of rapid systematic reviews of the latest scientific literature on rehabilitation have been prepared (Andrenelli 2020; Ceravolo 2020a; Ceravolo 2020b; De Sire 2020). However, these reviews do not aim to explore factors that influence the organisation and delivery of rehabilitation services.

Bettger and colleagues recently published a commentary to describe adjustments to the continuum of rehabilitation services across 12 low‐, middle‐, and high‐income countries in the context of national COVID‐19 preparedness responses. To obtain this information, 20 authors provided reports of rehabilitation practice in their own countries (Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, China, Germany, Guyana, India, Singapore, Spain, Tanzania, the UK,USA) during the COVID‐19 pandemic (Bettger 2020). This commentary describes some of the adaptations and reorganisation of the rehabilitation services carried out in these countries in response to COVID‐19. However, it is not a systematic review and does not have a methodology that allows a formal investigation of the factors that influence the organisation and delivery of rehabilitation services.

We are not aware of any systematic reviews of qualitative research exploring factors that influence the organisation and delivery of in‐person home‐based rehabilitation and home‐based telerehabilitation services, either in pandemic or ‘non‐pandemic’ contexts. Our qualitative evidence synthesis provides information that may be helpful for organising these services and that may also inform the design of future studies and systematic reviews of effectiveness.

Objectives

To identify factors that influence the organisation and delivery of in‐person home‐based rehabilitation for people needing rehabilitation.

To identify factors that influence the organisation and delivery of home‐based telerehabilitation for people needing rehabilitation.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included primary studies applying qualitative designs such as ethnography, phenomenology, case studies, grounded theory studies and qualitative process evaluations. We included studies that used both qualitative methods for data collection (e.g. focus group discussions, individual interviews, observation, diaries, document analysis), and qualitative methods for data analysis (e.g. thematic analysis, framework analysis, grounded theory). We included open‐ended survey questions analysed using a qualitative methodology. We excluded studies that collected data using qualitative methods but did not analyse these data using qualitative analysis methods (e.g. open‐ended survey questions where the response data are analysed using descriptive statistics only).

We included both published and unpublished studies and studies published in any language (see also section on Language translation below).

We included mixed‐methods studies where it was possible to extract the data that were collected and analysed using qualitative methods.

We included studies regardless of whether they were conducted alongside studies of the effectiveness of in‐person home‐based rehabilitation or home‐based telerehabilitation services or not.

We did not exclude studies based on our assessment of methodological limitations. We have used this information about methodological limitations to assess our confidence in the review findings.

Topic of interest

We included studies where the primary focus is experiences, perceptions and behaviours about the provision of in‐person home‐based rehabilitation and home‐based telerehabilitation services responding to patients’ needs in different phases of their health conditions (Gutenbrunner 2020b).

Types of participants

We included studies that explore the experiences, perceptions and behaviours of:

adults eligible for rehabilitation, defined as people with either a defined health condition, functioning problem, specific impairment, activity limitations, or participation restriction for which rehabilitation services are provided (Gutenbrunner 2020a);

informal caregivers directly involved in caring for people who are eligible for rehabilitation (often a family member or friend);

rehabilitation healthcare providers; these could include general and specialist physicians, nurses, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, respiratory therapists, psychologists, speech and language therapists, prosthetist and orthotist, community‐based rehabilitation workers, social workers, special educators, and other key professionals and lay health workers who use telerehabilitation to support or provide home‐based care to patients and/or their informal caregivers, or provide in‐person home‐based rehabilitation services;

other stakeholders involved in the commissioning, evaluation, design, and implementation of rehabilitation services. These could include policymakers at the local, national, or supranational level; administrative staff; information technology staff; managerial and supervisory staff at the organisational level; and technical staff who develop and maintain the platforms to provide telerehabilitation services.

Types of intervention

We define rehabilitation as ”a multimodal person‐centred process including functioning interventions, targeting body functions, activities and participation, and the interaction with the environment, aimed at optimising functioning in persons with health conditions, experiencing disability or likely to experience disability” (Negrini 2020c).

1. In‐person home‐based rehabilitation

We included studies of in‐person home‐based rehabilitation, which we defined as the delivery of rehabilitation services with in‐person encounters provided where the patient lives (e.g. home, nursing homes, long‐term care places) (Chi 2020). This can involve a range of services including continuous functioning assessment, prevention, diagnostic, therapy (e.g. nutritional support, dysphagia and swallowing, physical, psychological, cognitive, cardio‐respiratory, language therapy, occupational therapy, and respiratory therapy), monitoring, supervision, education, consultation, counselling, social support, psychological support, home‐based primary care, prescription and provision of assistive technologies (robotic devices, virtual reality devices, games and motion detection tools), home aids, family support, societal integration, home and workplace adaptations, mental support, home nursing and family help, and other methods of healthcare delivery Bittner 2020; Laver 2020; Rezaei 2019).

2. Home‐based telerehabilitation

We also included home‐based telerehabilitation studies, which we defined as the delivery of rehabilitation services where the patient lives using information and communication technologies (Brennan 2009). This can involve the same services as listed above for in‐person, home‐based rehabilitation (Bittner 2020; Laver 2020; Rezaei 2019).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Information Specialist Paola Andrea Ramírez developed the search strategies in consultation with the review authors, according to the search methods for qualitative synthesis (Booth 2016).

We searched the databases listed below. We did not apply any limits on language or publication date. We included a methodological filter for qualitative studies. See Appendix 1 for all strategies used.

We searched the following databases for primary studies:

PubMed, US National Library of Medicine (NLM) (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) (searched 16 June 2022);

Global Health, Ovid (https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/ovid/global‐health‐30) (searched 23 June 2022);

VHL Regional Portal, BIREME (https://bvsalud.org/) (searched 16 June 2022).

We searched MedXriv via BIREME (https://bvsalud.org/) for pre‐prints(searched 16 June 2022).

We searched the following databases for related systematic reviews that might include eligible primary studies:

Epistemonikos, Epistemonikos Foundation (www.epistemonikos.org/) (searched 16 June 2022);

Health Systems Evidence, McMaster University (www.healthsystemsevidence.org/) (searched 23 June 2022);

EBM Reviews, Ovid (https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/ovid/evidencebased‐medicine‐reviews‐ebmr‐904) (searched 23 June 2022).

Searching other resources

We searched international and regional web portals of rehabilitation organisations and associations to identify pertinent studies (searched June 2022).

We reviewed the reference lists of all included studies and key references of systematic reviews. Where necessary, we contacted the authors of included studies to clarify published information and to seek unpublished data. We contacted researchers with expertise relevant to the review topic to request studies that might meet our inclusion criteria.

Data collection, management, and synthesis

Selection of studies

Two review authors from a team of seven (LHL, AMP, DFP, MV, LFM, MAS, KMC) independently assessed the titles and abstracts of the identified records to evaluate eligibility. We retrieved the full text of all the papers identified as potentially relevant by both review authors. Two review authors from a team of nine then assessed these papers independently (LHL, AMP, DFP, MV, CG, LFM, CA, ASR, IL). We resolved disagreements by discussion or, when required, by involving a third review author.

Where the same study, using the same sample and methods, was presented in different reports, we collated these reports so that each study (rather than each report) is the unit of interest in our review.

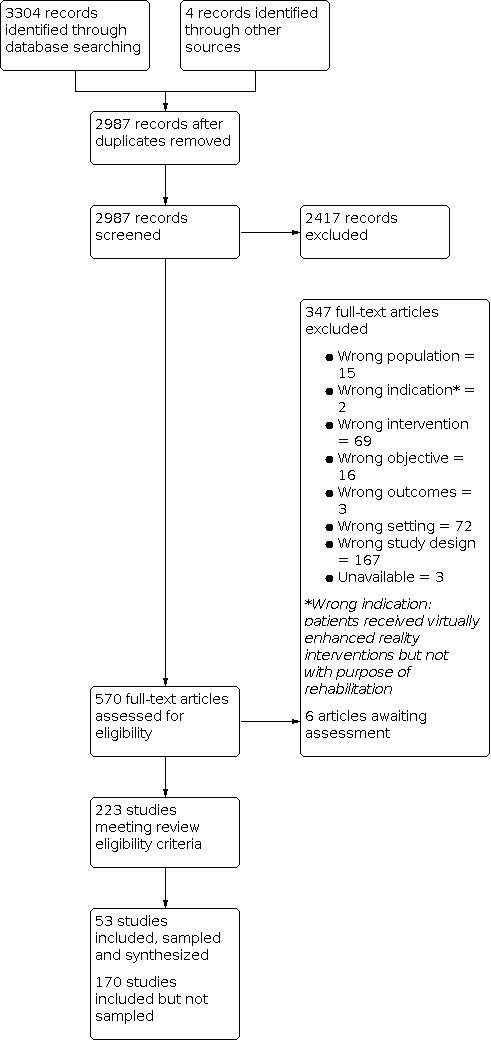

We included a PRISMA flow diagram to show our search results and the process of screening and selecting studies for inclusion (Figure 1).

1.

Language translation

For titles and abstracts that were published in a language that none of the review team are proficient in (i.e. languages other than English, Spanish, Norwegian, Italian, Portuguese, Swedish and Danish), we carried out an initial translation through open‐source software (Google Translate). If this translation indicated inclusion, or if the translation was inadequate to decide, we retrieved the full text of the paper. We then asked members of Cochrane networks or other networks that are proficient in that language to assist us in assessing the full text of the article for inclusion. If this could not be done for a paper in a particular language, the paper was listed under ‘studies awaiting classification,’ to ensure transparency in the review process.

Sampling of studies

Qualitative evidence synthesis aims for variation in concepts rather than an exhaustive sample, and large amounts of study data can impair the quality of the analysis. As we considered that the high number of studies we had included in the review represented a problem for the analysis, we decided to select a sample of these studies for the analysis.

To ensure the broadest possible variation within the studies sampled for analysis, we used a purposive sampling approach and applied maximum variation sampling (Patton 2002). This approach has been successfully implemented in several other qualitative evidence syntheses (Ames 2019; Karimi‐Shahanjarini 2019; McCartan 2020).

To answer our review questions, we decided on four criteria that would enable us to capture rich data from different settings, different types of participants and different health conditions. This became our four‐step sampling frame.

First, we sampled all studies from low‐ and middle‐income country (settings (LMICs), as most studies took place in high‐income country (HIC) settings and we wanted to ensure that findings from LMICs were represented in the synthesis. This gave us seven studies.

Second, we sampled an additional 14 studies that maximized the variation on the types of participants included in the studies (patients and caregivers, healthcare providers, and other stakeholders).

Third, we sampled an additional 23 studies that maximized variation in relation to the type of disability explored in the study (mobility, vision, hearing, or cognition).

Finally, we went through the remaining studies and, for the study data that were relevant to the synthesis objective, assessed the richness of these data. We considered a data‐rich study to be one that provided more detailed descriptions to understand patients', caregivers', healthcare providers' and other stakeholders' experiences and opinions about home‐based rehabilitation. We assessed the richness of these data in relation to our review question as high (i.e. providing perspectives of more than one type of participant‐patients, caregivers, healthcare providers and other stakeholders‐; addressing more than one domain in the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR); and in‐depth data analysis), moderate (i.e., providing perspectives of more than one type of participant or addressing more than one domain in the CFIR framework) or poor (i.e. providing perspectives of one type of participant or addressing only one domain in the CFIR framework ). We then sampled all nine studies that we rated as having moderate or high data richness.

This process gave us a total of 53 sampled studies.

Extraction of information about study characteristics

Two pairs of review authors (AMP, LFM, KMC, MAS) independently extracted information about the study characteristics of the included papers. We extracted information about:

author(s), year, country;

mode of rehabilitation delivery (e.g. home‐based rehabilitation services, home aids, home modifications, home nursing and family help, telerehabilitation);

type of participant (i.e. patient, caregiver, healthcare provider, other stakeholders);

health condition (i.e. physical, vision, hearing, or cognition);

study design, approach for data collection and analysis.

We resolved any differences of opinion about study characteristics by consensus within the pairs of review authors that extracted the information about study characteristics.

Assessing the methodological limitations of included studies

Two review authors [MV, KMC, MAS] independently assessed methodological limitations for each study using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme 2013). We summarised the methodological limitations judgments across different studies for each of the domains listed below.

Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research?

Is a qualitative methodology appropriate?

Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research?

Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research?

Were the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue?

Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered?

Have ethical issues been taken into consideration?

Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous?

Is there a clear statement of findings?

How valuable is the research? (Determined by assessing the richness of the study data. See section above on 'Sampling of studies' for details).

We resolved disagreements by discussion or, when required, by engaging a third review author. Where any of the review authors were also authors of included studies, they were not involved in the assessment of the study’s methodological limitations.

Data extraction, analysis and synthesis

We considered a number of potentially relevant frameworks for data analysis but chose the CFIR because it provided us with a comprehensive list of factors that could influence intervention implementation (Damschroder 2009). The CFIR has been developed based on different constructs associated with effective implementation; supported by a compilation of publications across 13 scientific disciplines (Damschroder 2009; Means 2020). CFIR facilitates systematic analysis and organisation of findings from implementation studies and, in addition, is adaptable to different settings and scenarios. The CFIR framework is composed of five major domains, each of which may affect an intervention’s implementation (Damschroder 2009; Means 2020).

Intervention characteristics (i.e. key attributes of interventions that influence the success of implementation as their complexity, costs, design, among others).

Inner setting (i.e. features of the implementing organisation as their structural characteristics, networks and communications, culture, and readiness for implementation).

Outer setting (i.e. features of the external context or environment as external policies, incentives, and constraints; patient needs and resources; and peer pressure).

Characteristics of individuals involved in implementation (i.e., individual stage of change, knowledge and beliefs about the intervention, self‐efficacy, and other personal attributes).

Implementation process (i.e. strategies or tactics that might influence implementation, these include strategies for engaging, executing, planning, reflecting and evaluating).

See also Figure 2 for a representation of using the CFIR framework in this review.

2.

Relationship between CFIR Framework and this qualitative evidence synthesis

Extracting and coding the evidence against the CFIR framework: we developed a data extraction form that was based on the CFIR framework and that was piloted on a small number of studies before final approval. Five review authors (MV, LHL, AMP, DP, and LFM) used this data extraction form to extract data on participants’ experiences, perceptions, and behaviours about factors that influence the provision of in‐person home‐based rehabilitation and telerehabilitation services and to code this data against the CFIR framework. A pilot trial of the data extraction form was conducted to check its adequacy, and changes were made when necessary.

Once the five review authors had finished data extraction, four review authors (MV, CG, ASR, and IL) checked this data extraction and verified that all relevant data were extracted. We included data in the form of quotes or field note extracts, as well as authors’ interpretations which could be presented in either the results or discussion sections of the articles.

Once our analyses were finalised, we explored whether any of the factors we had identified were primarily based on studies from high‐, middle‐, or low‐income settings and if they represented only a particular group of patients.

Developing implications for practice

Once we had finished preparing the review findings, we examined each finding, identified factors that could influence the implementation of the intervention/s, and developed prompts for future implementers. These prompts are not intended to be recommendations but are phrased as questions to help implementers consider the implications of the review findings within their context. We sent these prompts to a selection of stakeholders from different countries and professional backgrounds to gather their feedback about the relevance of these prompts and how they are phrased and presented, and then revised the prompts accordingly. These prompts are presented in the "implications for practice" section.

Assessing our confidence in the review findings

Four review authors [MV, LHL, AMP, and DP] used the GRADE‐CERQual (Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research) approach to assess our confidence in each finding (Lewin 2018). GRADE‐CERQual assesses confidence in the evidence, based on the following four key components.

Methodological limitations of included studies: the extent to which there are concerns about the design or conduct of the primary studies that contributed evidence to an individual review finding.

Coherence of the review finding: an assessment of how clear and cogent the fit is between the data from the primary studies and a review finding that synthesises those data. By cogent, we mean well‐supported or compelling.

Adequacy of the data contributing to a review finding: an overall determination of the degree of richness and quantity of data supporting a review finding.

Relevance of the included studies to the review question: the extent to which the body of evidence from the primary studies supporting a review finding is applicable to the context (perspective or population, phenomenon of interest, setting) specified in the review question.

After assessing each of the four components, we developed a ‘Summary of qualitative findings’ table and made a judgment about the overall confidence in the evidence supporting the review finding. We judged confidence as high, moderate, low, or very low. The final assessment was based on consensus among the review authors. All findings started as high confidence and then were graded down if there are important concerns regarding any of the GRADE‐CERQual components.

Summary of Qualitative Findings table(s) and Evidence Profile(s)

We presented summaries of the findings and our assessments of confidence in these findings in a Summary of Qualitative Findings table. We have included detailed descriptions of our confidence assessments in an GRADE‐CERQual Qualitative Evidence Profile (Appendix 2).

Results

Results of the search

The search retrieved 2987 records after duplicates were removed. We reviewed 570 articles in full‐text, 347 were excluded (Additional file) and 223 articles met our inclusion criteria, of which eight were performed in low‐ and middle‐income countries. Eighty‐one studies addressed in‐person home‐based rehabilitation without a telehealth component. One‐hundred‐ten studies addressed home‐based telerehabilitation services. Thirty‐two studies addressed both in‐person home‐based rehabilitation and home‐based telerehabilitation services. Eighty studies presented the perspectives of different types of participants, the remaining studies presented only the perspective of patients (n =105), caregivers (n = 8), healthcare providers (n = 26), and other stakeholders (n = 5). In relation to health conditions, 63 studies focused on rehabilitation services for people who had a stroke. The remaining studies focused on people with cardiovascular diseases (n = 35), musculoskeletal disorders (n = 20), rehabilitation services for elderly people (n = 17), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n = 11), cancer (n = 11), brain injury (n = 10), Multiple Sclerosis (n = 10), spinal cord injury, (n = 10), persistent pain (n = 4), intellectual disabilities (n = 3), hearing impairments (n = 1), joint replacements (n = 1), temporomandibular disorders (n = 1), rheumatoid arthritis (n = 1), and burn (n = 1). Six studies did not specify the health condition.

From the 223 studies that met our inclusion criteria, we sampled 53 studies for inclusion in the analysis (Figure 1). All of the sampled studies were published between 2009 and 2020, except for one from 2004 (Dubouloz 2004). All of the studies were published in English. We found six studies that could not be translated and we listed them under the section Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Description of the studies

In this section, we describe the studies that we included and sampled. For a more detailed description of 53 studies that were included and sampled see Table 2. For a description of studies that were included but not sampled see Table 3.

1. Characteristics of studies included and sampled.

| Author(s), Year | Country | Mode of rehabilitation delivery | Description of study participants | Health condition or disability addressed by the study/Type of rehabilitation delivered | Study design/ Data collection approach/ Data analysis approach |

| Argent 2018 | Ireland | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Ten healthcare professionals (four physiotherapists, two clinical nurse specialists, two orthopaedic assistants, one occupational therapist and one staff nurse) | Joint replacement/ Exercise therapy |

Qualitative study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Thematic analysis with a grounded‐theory approach |

| Borade 2019 | India | In‐person home‐based rehabilitation | Twenty‐five patients having mobility related disabilities, who used one or more ads | Mobility restriction/ Activities in daily living (ADL) | Qualitative study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Thematic analysis |

| Brouns 2018 | Netherlands | In‐person + home‐based telerehabilitation | Thirty‐two patients, fifteen caregivers, and thirteen healthcare professionals (physiotherapists, psychologists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, physicians, and managers) | Stroke/ Multidisciplinary | Qualitative study/ Semi‐structured individual and focus group interviews/ Direct content analysis using the implementation model of Grol |

| Bodker 2015 | Denmark | In‐person + home‐based telerehabilitation | Eleven patients with COPD and the therapist of the programme (managing nurse and the physiotherapist) | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease/ Pulmonary |

Ethnographic/ Observations and semi‐structured interviews/ Analytical concepts developed within STS (Science and Technology Studies) in order to study the taming and unleashing of telecare |

| Damhus 2018 | Denmark | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Twenty‐five healthcare professionals (6 nurses and 19 physiotherapists) | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease/ Respiratory |

Theoretical domains framework/ Semi‐structured individual and focus group interviews/ Data were triangulated and was used as a coding framework in the analysis |

| Dennett 2020 | England | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Eleven patients with multiple sclerosis | Multiple Sclerosis/ Exercise therapy | Qualitative study/ In‐depth, individual, face‐to‐face interviews/ Thematic analysis |

| Dinesen 2019 | Denmark | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Fourteen cardiac patients, twelve patient spouses/partners, and one son | Cardiac disease/ Cardiac | Descriptive case study/ Documents, participant observation, and interviews/ Thematic analysis |

| Dubouloz 2004 | Canada | In‐person home‐based rehabilitation | Six patients with rheumatoid arthritis | Arthritis/ Activities in daily living (ADL) | Grounded theory study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Constant comparative analysis |

| Edbrooke 2020 | Australia | In‐person home‐based rehabilitation | Ninety‐two patients with non‐small cell lung cancer | Cancer/ Exercise therapy | Mixed methods study / Semi‐structured interviews, home visits and telephone calls/ Content analysis |

| Emmerson 2018 | Australia | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Ten patients with stroke and upper limb impairment | Stroke/ Exercise therapy | Convergent mixed methods design, based on phenomenology/ Semi‐structured interview in‐depth/ Thematic analysis |

| Folan 2015 | Australia | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Seven patients ( 4 in‐patients and 3 out‐patients) with spinal cord injury | Spinal cord injury/ Activities in daily living (ADL) | Qualitative study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Thematic analysis |

| Govender 2019 | South Africa | In‐person home‐based rehabilitation | Five patients, five family caregivers, five community partners, five clinicians, and five researchers | Elderly/ Multidisciplinary | Exploratory study/ Survey and semi‐structured interviews/ Thematic analysis |

| Gélinas‐Bronsard 2019 | Canada | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Eight patients who had suffered a stroke |

Stroke/ Multidisciplinary | Individual qualitative study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Content analysis |

| Hale Gallardo 2020 | United States | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Ten stakeholders (medical directors and program managers) | Not specified/ Exercise therapy | Qualitative study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Thematic analysis |

| HeydariKhayat 2020 | Iran | In‐person home‐based rehabilitation | Sixteen burn survivors patients | Burns/ Multidisciplinary | Phenomenological study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Thematic analysis |

| Hoaas 2016 | Norway | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Ten patients with moderate to severe COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease /Respiratory | Mixed methods study/ Analysis of logs on the webpage, semi‐structured focus groups, standardised questionnaire and an individual open‐ended questionnaire/ Thematic analysis |

| Kamwesiga 2017 | Uganda | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Eleven patients with stroke and nine family caregivers | Stroke/ Multidisciplinary | Grounded theory study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Constant comparative analysis |

| Lawson 2020 | Australia | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Twenty‐five patients with stroke and nine healthcare professionals | Stroke/ Cognitive | Qualitative study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Inductive thematic analysis |

| Malmberg 2018 | Sweden | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Twenty patients that had used Internet interventions for hearing aid | Hearing impairment/ Communication | Qualitative exploratory study/ Semi‐structured telephone interviews/ Content analysis |

| Mendell 2019 | Canada | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Thirty‐eight patients with acute coronary syndrome | Acute coronary syndrome/ Cardiac | Qualitative study/ Chat sessions/ Thematic analysis |

| Mohd Nordin 2014 | Malaysia | In‐person home‐based rehabilitation | Fifteen rehabilitation professionals and eight stroke survivors | Stroke/ Multidisciplinary | Qualitative study/ Focus groups/ Thematic analysis |

| Ng 2013 | Canada | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Three patients and their significant others | Brain Injury/ Cognitive | Case study/ Feedback interviews, therapist´s field notes and session recordings/ Descriptive analysis |

| Nordin 2017 | Sweden | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Nineteen patients with persistent musculoskeletal pain | Persistent Pain/ Multimodal for pain | Qualitative study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Content analysis |

| O'Doherty 2013 | Ireland | In‐person home‐based rehabilitation | Ten nurses | Elderly/ Nursing in | Qualitative descriptive study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Thematic analysis |

| O'Shea 2020 | Dublin and Belgium | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Forty‐four patients with cardiovascular disease | Cardiovascular disease/ Cariac | Qualitative study/ Participant debriefs, interviews/ Braun and Clarke framework for thematic analysis |

| Ownsworth 2020 | Australia | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Thirteen multidisciplinary rehabilitation coordinators, nine patients, and eight family caregivers | Brain injury/ Multidisciplinary | Qualitative study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Inductive analysis |

| Oyesanya 2019 | United States | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Fifteen patients and twelve caregivers | Brain Injury/ Multidisciplinary | Qualitative exploratory study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Content analysis |

| Palazzo 2016 | France | In‐person + home‐based telerehabilitation | Twenty‐nine patients with chronic low back pain | Chronic low back pain/ Multidisciplinary | Qualitative study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Thematic analysis |

| Palmcrantz 2017 | Sweden | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Fifteen patients who had suffered stroke | Stroke/ Exercise therapy | Qualitative study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Content analysis |

| Pekmezaris 2020 | United States | In‐person home‐based rehabilitation | Approximately 20 community advisory board members, one‐third were patients and caregivers, one‐third were providers (pulmonologists, researchers, and primary care physicians), and another one‐third were the other stakeholders (such as community‐based organizations) |

Pulmonary diseases/ Respiratory | Qualitative study/ Focus groups/ Content analysis |

| Pinto 2014 | Brazil | In‐person home‐based rehabilitation | Twenty‐three patients with COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease/ Respiratory | Qualitative study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Thematic content analysis and contextualized semantic interpretation |

| Ranaldi 2018 | United Kingdom | In‐person home‐based rehabilitation | Four hundred fifty‐seven patients with cardiac disease | Cardiac disease/ Cardiac | Qualitative study/ Questionnaires/ Thematic analysis |

| Randström 2012 | Sweden | In‐person home‐based rehabilitation | Ten older patients | Elderly/ Multidisciplinary | Qualitative study/ Interviews/ Content analysis |

| Randstrom 2013 | Sweden | In‐person home‐based rehabilitation | Six older patients and six family members | Elderly/ Multidisciplinary | Qualitative descriptive study/ Interviews/ Content analysis |

| Randström 2014 | Sweden | In‐person home‐based rehabilitation | Twenty‐eight healthcare providers, six physiotherapists, three occupational therapists, five district nurses, five nurse assistants, one home helper, three home help officers responsible for needs assessment and five home help officers in charge of home help | Elderly/ Multidisciplinary | Qualitative descriptive study/ Focus groups/ Content analysis |

| Rietdijk 2020 | Australia | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Thirty‐six patients and their caregivers | Elderly/ Communication | Mixed methods study/ Skype interview, telephone interview or written questionnaire/ Inductive thematic analysis |

| Rizzo 2019 | United States | In‐person home‐based rehabilitation | Ten patients with orthopaedic diagnoses | Musculoeskeletal/ Exercise therapy | Interpretative study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Constant comparative analysis |

| Saywell 2015 | New Zealand | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Fifteen patients who had suffered stroke | Stroke/ Exercise therapy | Qualitative descriptive study/ A brief questionnaire was used to gather data on mobile phone ownership/ Inductive analysis |

| Schopfer 2020 | United States | In‐person home‐based rehabilitation | One hundred and seventy one patients with cardiac diseases (acute myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, obstructive coronary artery disease, stable angina, valve replacement and some outpatients with stable heart failure | Cardiac disease/ Cardiac | Mixed methods study/ Survey, and open‐ended semi‐structured interviews/ Thematic analysis |

| Shulver 2016 | Australia | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Forty‐four health workers (experienced and inexperienced) providing services to older people in the areas of rehabilitation and allied health, residential aged care and palliative care | Elderly/ Multidisciplinary | Qualitative study/ Semi‐structured focus groups/ Thematic analysis |

| Shulver 2017 | Australia | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Thirteen older patients, three spouses and one caregiver | Elderly/ Exercise therapy | Qualitative study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Thematic analysis |

| Silveira 2019 | United States | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Twenty patients with multiple sclerosis who use wheelchairs | Multiple Sclerosis/ Exercise therapy | Qualitative study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Deductive content analysis |

| Stark 2019 | Germany | In‐person home‐based rehabilitation | Thirteen patients and nine non‐professional coaches (family members) | Stroke/ Exercise therapy | Mixed methods study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Hermeneutic phenomenological data analysis |

| Stuifbergen 2011 | United States | In‐person + home‐based telerehabilitation | Thirty‐four patients with multiple sclerosis | Multiple Sclerosis/ Cognitive | Qualitative exploratory, descriptive study/ Qualitative data from a questionnaire administered by phone/ Content analysis |

| Sureshkumar 2016 | India | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Sixty patients and their caregivers | Stroke/ Multidisciplinary | Mixed methods study/ Semi‐structured questionnaire/ Framework approach |

| Teriö 2019 | Uganda | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Twelve participants: Four occupational therapists, three researchers, three information technology (IT) specialists and two rehabilitation managers | Stroke/ Activities in daily living (ADL) | Single‐case study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Framework approach |

| Tsai 2016 | Australia | In‐person + home‐based telerehabilitation | Eleven patients with COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease/ Respiratory | Mixed methods study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Thematic descriptive analysis |

| Turner 2011 | Australia | In‐person home‐based rehabilitation | Twenty patients and eighteen family caregivers | Brain Injury/ Multidisciplinary | Qualitative study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Thematic analysis |

| Tyagi 2018 | Singapore | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Thirty‐seven participants: 13 patient‐caregiver dyads and 11 therapists | Stroke/ Exercise therapy | Qualitative study / Semi‐structured in‐depth interviews and focus group discussions/ Thematic analysis |

| Umb Carlsson 2019 | Sweden | In‐person home‐based rehabilitation | Five residents, six staff members and five rehabilitation professionals | Intellectual disability/ Promotion of healthy lifestyles | Qualitative study/ Semi‐structured interviews/ Content analysis |

| Van der Meer 2020 | Netherlands | Home‐based telerehabilitation | Nine patients and eleven orofacial physical therapists | Temporomandibular Disorders/ Exercise therapy |

Qualitative descriptive study/ Open face‐to‐face interviews/ Thematic analysis |

| VanderVeen 2019 | Netherlands | In‐person home‐based rehabilitation | Fourteen healthcare professionals: two occupational therapists, two physical therapists, two case managers, a psychologist, an elderly advisor, a nurse, a speech therapist, a nursing home manager, a manager in allied healthcare, a general practitioner and a geriatrician. | Stroke/ Multidisciplinary | Qualitative study/ Focus groups and semi‐structured interviews/ Content analysis |

| Vik 2009 | Norway | In‐person home‐based rehabilitation | Three older patients | Elderly/ Nursing in | Case study/ Interviews/ Grounded theory |

2. Studies that met our inclusion criteria but were not sampled for analysis.

| Author / year | Country | Health condition | Mode of rehabilitation delivery |

| Alary Gauvreau 2019 | Canada | Aphasia | Telerehabilitation |

| Ando 2019 | United Kingdom | Motor neurone disease | Telerehabilitation |

| Banner 2015 | Canada | Heart disease | Telerehabilitation |

| Barclay 2020 | Australia | Spinal cord injury | Home‐based + telerehabilitation |

| Bendelin 2018 | Sweden | Chronic pain | Home‐based + telerehabilitation |

| Birkeland 2017 | Norway | No specific health condition described | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Boland 2018 | New Zealand | Stroke | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Booth 2007 | Australia | Spinal cord injury | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Brennan 2020 | Ireland | Cancer | Home‐based + telerehabilitation |

| Brewer 2017 | United States | Heart disease | Telerehabilitation |

| Buimer 2017 | Netherlands | Cancer | Telerehabilitation |

| Burkow 2015 | Norway | Pulmonary diseases | Home‐based + telerehabilitation |

| Caughlin 2020 | Canada | Stroke | Telerehabilitation |

| Chen 2019a | China | Elderly | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Chen 2019b | United States | Stroke | Telerehabilitation |

| Cherry 2017 | United States | Stroke | Telerehabilitation |

| Choularia 2014 | United Kingdom | Stroke | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Clark 2013 | Australia | Heart disease | Telerehabilitation |

| Cobley 2013 | United Kingdom | Stroke | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Constantinescu 2017 | Canada | Cancer | Home‐based + telerehabilitation |

| Conti 2015 | Italy | Spinal cord injury | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Cottrell 2017 | Australia | Musculoeskeletal | Telerehabilitation |

| Davoody 2016 | Sweden | Stroke | Home‐based + telerehabilitation |

| Davoody 2014 | Sweden | Stroke | Telerehabilitation |

| DeVries 2017 | Netherlands | Arthritis | Home‐based + telerehabilitation |

| Deighan 2017 | United Kingdom | Heart disease | Telerehabilitation |

| Delmar 2009 | Denmark | Musculoeskeletal | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Demain 2013 | United Kingdom | Stroke | Home‐based + telerehabilitation |

| Dimaguila 2019 | Australia | Stroke | Telerehabilitation |

| Dinesen 2011 | Denmark | Pulmonary diseases | Telerehabilitation |

| Dinesen 2013 | Denmark | Pulmonary diseases | Telerehabilitation |

| Dinesen 2018 | Denmark | Heart disease | Telerehabilitation |

| Dithmer 2016 | Denmark | Heart disease | Telerehabilitation |

| Dobson 2019 | New Zealand | Pulmonary diseases | Telerehabilitation |

| Doig 2009 | Australia | Traumatic brain injury | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Donoso Brown 2015 | United States | Stroke | Home‐based + telerehabilitation |

| Dow 2007 | Australia | Stroke, cancer, brain tumour, amputation, Parkinson's and musculoskeletal | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Duggan 2013 | United Kingdom | Chronic pain | Home‐based + telerehabilitation |

| Eliassen 2018 | Norway | Musculoeskeletal and Stroke | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Eriksson 2011 | Sweden | Musculoeskeletal | Home‐based + telerehabilitation |

| Essery 2017 | United Kingdom | Vestibular dysfunction | Telerehabilitation |

| Feinberg 2018 | United States | Heart disease | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Forman 2014 | United States | Heart disease | Telerehabilitation |

| Forsberg 2014 | Sweden | Multiple sclerosis | Telerehabilitation |

| Frohmader 2017 | Australia | Heart disease | Telerehabilitation |

| Frohmader 2015 | Australia | Heart disease | Telerehabilitation |

| Frost 2019 | United Kingdom | Heart disease | Home‐based + telerehabilitation |

| Galvin 2014 | Ireland | Stroke | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Gell 2019 | United States | Cancer | Telerehabilitation |

| Giesbrecht 2014 | Canada | Elderly | Telerehabilitation |

| Gilbert 2019 | United Kingdom | Musculoeskeletal | Telerehabilitation |

| Giunti 2018 | Switzerland | Multiple sclerosis | Telerehabilitation |

| Gustafsson 2019 | Sweden | Elderly | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Gustafsson 2014a | Australia | Stroke | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Gustafsson 2014b | Australia | Stroke | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Hale 2005 | New Zealand | Stroke | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Harder 2017 | United Kingdom | Cancer | Telerehabilitation |

| Hathiramani 2019 | United Kingdom | Cancer | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Hayward 2015 | Australia | Stroke | Home‐based + telerehabilitation |

| Herber 2017 | United Kingdom | Heart disease | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Heron 2019 | United Kingdom | Stroke | Telerehabilitation |

| Higgins 2017 | Australia | Heart disease | Telerehabilitation |

| Hill 2016 | Australia | Aphasia | Telerehabilitation |

| Hines 2017 | Australia | Traumatic brain injury | Telerehabilitation |

| Hjelle 2017 | Norway | Elderly | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Hoffman 2017 | United States | Cancer | Telerehabilitation |

| Hwang 2017 | Australia | Heart disease | Telerehabilitation |

| Inskip 2018 | Canada | Pulmonary diseases | Telerehabilitation |

| Jakobsen 2018 | Norway | Elderly | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| James 2018 | Australia | Motor neurone disease | Home‐based + telerehabilitation |

| Jansen‐Kosterink 2019 | Netherlands | Chronic diseases | Telerehabilitation |

| Jäppinen 2017 | Finland | Musculoeskeletal | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Jelin 2012 | Norway | Chronic pain | Telerehabilitation |

| Jones 2017 | United Kingdom | Stroke | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Jones 2007 | United Kingdom | Heart disease | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Jullamate 2007 | Thailand | Stroke | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Kairy 2014 | Canada | Traumatic brain injury | Telerehabilitation |

| Kairy 2013 | Canada | Musculoeskeletal | Telerehabilitation |

| Kingston 2014 | Australia | Musculoeskeletal | Telerehabilitation |

| Knudsen 2019 | Denmark | Heart disease | Telerehabilitation |

| Krishnan 2018 | United States | Stroke | Telerehabilitation |

| Lahham 2017 | Australia | Pulmonary diseases | Home‐based + telerehabilitation |

| Lai 2019 | United States | Disability | Telerehabilitation |

| Lawford 2018a | Australia | Musculoeskeletal | Telerehabilitation |

| Lawford 2018b | Australia | Musculoeskeletal | Telerehabilitation |

| Learmonth 2019 | Australia | Multiple sclerosis | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Lee 2009 | Canada | Heart disease | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Letts 2011 | Canada | Spinal cord injury | Telerehabilitation |

| Lindblom 2020 | Sweden | Stroke | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Lou 2017 | Denmark | Stroke | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Lovo Grona 2017 | Canada | Musculoeskeletal | Telerehabilitation |

| Lovo 2019 | Canada | Musculoeskeletal | Telerehabilitation |

| Lutz 2009 | United States | Stroke | Telerehabilitation |

| Lykke 2019 | Denmark | Elderly | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Madden 2010 | United Kingdom | Heart disease | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Magne 2020 | Norway | Elderly | Home‐based rehabilitation |

| Markle‐Reid 2020 | Canada | Stroke | Home‐based + telerehabilitation |

| Martin 2018 | United Kingdom | Traumatic brain injury | Telerehabilitation |

| Martinez 2017 | United States | Traumatic brain injury | Telerehabilitation |

| Marwaa 2020 | Denmark | Stroke | Telerehabilitation |

| Mawson 2016 | United Kingdom | Stroke | Telerehabilitation |