Abstract

Limited access to screening and evaluation for an Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in children is a major barrier to improving outcomes for marginalized families. To identify and evaluate available digital ASD screening resources, we simulated web and mobile app searches by a parent concerned about their child’s likelihood of ASD. Included digital ASD screening tools were: a) on internet or mobile app; b) in English; c) parent user inputting data; d) assigns likelihood category to child <9 years; and e) screens for ASD. Ten search terms, developed using Google Search and parent panel recommendations, were used to search web and app tools in US, UK, India, Australia, Canada using Virtual Private Networks. Results were examined for attributes likely to benefit parents in marginalized communities, such as ease of searching, language versions, and reading level. The four terms most likely to identify any tools were “autism quiz,” “autism screening tool,” “does my child have autism,” and “autism toddler.” 3/5 of searches contained ASD screening tools, as did 1 out of 10 links or apps. Searches identified a total of 1,475 websites and 919 apps, which yielded 23 unique tools. Most tools required continuous internet access or offered only English, and many had high reading levels. In conclusion, screening tools are available, but they are not easily found. Barriers include inaccessibility to parents with limited literacy or limited English proficiency, and frequent encounters with games, advertisements, and use fees.

Keywords: Autism Spectrum Disorder, Mobile Applications, Mass Screening, Digital Divide, Child, Preschool, Parents

Lay Summary

Many parents wonder if their child might have autism. Many parents use their smartphones to answer health questions. We asked, “How easy or hard is it for parents to use their smartphones to find ‘tools’ to test their child for signs of autism?” After doing pretend parent searches, we found that only 1 in 10 search results were tools to test children for autism. These tools were not designed for parents who have low income or other challenges such as low literacy skills, low English proficiency, or not being tech-savvy.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) affects 1 in 44 children (Maenner et al., 2021), and early treatment can be very effective. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends screening all children for ASD at 18- and 24-month primary care visits using a validated screening instrument (Hyman, Levy, & Myers, 2020), and awareness initiatives such as the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s “Learn the Signs Act Early” campaign aim to help parents and others recognize signs of ASD within and outside the clinical context. Although awareness of ASD has risen in recent decades, there remains a gap between symptom presentation, diagnosis, and subsequent treatment. This gap is not evenly shared by all families—having a lower income, being Black, and being Latinx are each associated with older age at diagnosis of ASD (Hyman et al., 2020). ASD screening rates at healthcare visits using a validated instrument exceeded 70% only recently, and even among those who are screened, studies have shown that many children with positive screening results are not referred for evaluation (Lipkin et al., 2020; Wallis et al., 2020; Zuckerman et al., 2020). As a result, there is ample opportunity to detect more children early for treatment and to reduce inequitable access to early detection.

Parents, including many from low income and minority backgrounds, have access to information about child development online. Eighty-five percent of adults in the United States own smartphones (Pew Research Center, 2021), which could offer access to ASD screening instruments both in clinical and non-clinical settings. Access to smartphones is prevalent among US adults who identify as Black (83%) and Latinx (85%), and among a solid majority (76%) of those with low income (Pew Research Center, 2021). Use of such mobile screening tools may empower some parents to assess their own child and discuss resulting concerns with their healthcare provider. This may help reduce the age of ASD diagnosis, as parents’ concerns about their child’s behavior often precede an ASD diagnosis by months to several years (Zwaigenbaum et al., 2015). Validated parent-report instruments to screen for ASD are also in common use in clinical settings, and many are adaptable for electronic use in the form of a website or mobile app.

However, the potential for mobile devices to reduce health inequities, including those seen with ASD detection and treatment, is unclear. The “digital divide,” describing inequalities between those who benefit from information technology and those who do not, is well documented. Further, Veinot and colleagues document how electronic health resources can worsen health inequities when adopted by the wealthy white (Veinot, Mitchell, & Ancker, 2018). The digital divide appears to have exacerbated many inequities in health access observed during the home isolation needed to fight the early Covid-19 pandemic (Shaw, Brewer, & Veinot, 2021). Adults with low income or less education have less broadband internet access, are more likely to be dependent on smartphones as their only internet access, and are less likely to own any computing device (Ryan, 2017). Families with low income often have below-average literacy and/or health literacy, which may limit capacity to identify and use electronic ASD screening tools. In addition, electronic resources available to concerned parents may not incorporate socially inclusive content or technology that would otherwise support access by all families (Latulippe, Hamel, & Giroux, 2017).

Veinot and colleagues (2018, p. 1081) state that health interventions exacerbate existing inequalities if they are “a) more accessible to, b) adopted more frequently by, c) adhered to more closely by, or d) more effective in socioeconomically advantaged groups.” This may be called “intervention-generated” inequality—while ASD identification in a population overall might improve, the benefits of mobile health ASD screening may be distributed unevenly across the digital divide, worsening inequities in ASD identification (Veinot et al., 2018). We adapt the Veinot et al. conceptual model in Figure 1 (with permission) to suggest mobile health mechanisms for intervention-generated inequality. This adapted model posits that baseline health inequalities are moderated by disparities in access to mHealth technologies (e.g., access to newer mobile devices or broadband, opportunities through employers or healthcare), disparities in uptake of mHealth technology (e.g., differences in social networks, trust in technology and healthcare), disparities in adherence (e.g., time needed to complete a screener, language capabilities), and disparities in effectiveness (e.g., low evidence of efficacy in certain groups). These disparities ultimately result in disparities in evaluation and reporting (e.g., lack of inclusion of People of Color in studies, lack of inclusion of health equity outcomes).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of intervention-generated inequality and mobile health screening. Adapted, with permission, from Veinot, Mitchell, & Ancker (2018) JAMIA, 25(8), 1080–1088.

Such disparities may particularly apply in the case of mHealth ASD screening tools. Parents, including those from low-income and/or lower educational attainment backgrounds, are using digital health information to obtain medical information about their children (Kubb & Foran, 2020; Real et al., 2018). We do not know what they may find to assess their child’s likelihood of an ASD, or whether inequities in ASD identification are worsened in the process. To begin to address this knowledge gap, this study identifies ASD screening resources available to parents, with attention to barriers preventing benefit to parents of low income, racial minorities, and other marginalized groups. The study has two aims: 1) to characterize the results of simulated internet and mobile application searches for screening tools by a hypothetical parent who is concerned about their child’s likelihood of ASD, and; 2) to document preliminary characteristics that may make mobile-compatible screening tools more or less beneficial for marginalized families.

Methods

This study was conducted as a part of a larger project exploring mobile ASD screening. The Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board prospectively reviewed this study and determined it was not human subject research.

Patient and Public Involvement

This study was part of a larger project on equity in access to online ASD screening tools. The larger project solicited periodic feedback from a paid online advisory panel consisting of parents of kids with ASD, parents of children with typical development, and an autistic adult. Parents on the advisory panel were diverse in terms of their racial/ethnic background, educational attainment, and urbanicity. In this project, parent panel members played a critical role in development of online search terms (see below). The actual online search process and subsequent analysis did not involve community members; however, study results were shared with panel members for feedback. Two co-authors are participants in a mentorship program supporting minorities in the health sciences; the study team also includes investigators and parents of children across a spectrum of neurodiversity.

Definition of Mobile Autism Screening Tools

In order to simulate a mobile smartphone search by a parent, we defined mobile health ASD screening tools using the following criteria: a) existing on the publicly searchable internet or as a mobile application on Google Play or Apple Store; b) assigning an ASD likelihood category to a child; c) the parent is a user who inputs data (other users, such as a child or clinician, were allowable in addition); d) is designed for children under 9 years of age at most; and f) available in English (other languages could be supported in addition to English).

Search terms

Our search term goal was to obtain a set of 10 search terms that would approximate a parent searching for an assessment of their child’s ASD likelihood (Figure 2). We developed an initial set of terms and phrases related to our hypothetical scenario by typing terms related to detecting ASD into a Google Search bar, noting the Google Autocomplete predictions that resulted (Sullivan, 2018), and repeating this process with new terms until no new relevant terms were identified (Figure 2D). These terms were then expanded by the investigator team, for a total of 42 candidate terms.

Figure 2.

mHealth Autism Screening: search term development

Parent advisors were presented with the following hypothetical scenario:

You are worried that your 2-year-old child might have autism. You go online to find a website that can help assess your child’s autism risk.

Then, they were asked to respond to two questions. First, they generated their own responses to the above scenario when asked (Figure 2A):

What would you type into your search bar on Google? List your 5 most likely entries.

This generated 78 unique responses which we summarized into four themes (Figure 2, A–B). The first, “When you can know,” incorporated responses about the age at which signs of ASD can be observed. The second theme called “Sign, symptom, characteristic” grouped the panel’s search suggestions about observable signs of ASD. The third and fourth themes, “Diagnose, diagnosis, assess, identify” and “How to know/tell/find out,” grouped responses containing key words similar to their respective titles. To represent the first of these four themes, “When you can know” (Figure 2, C, G, search terms 1–4), we used four age-specific terms to represent a range of age groups. The three remaining themes were used to organize results from question two. This second question presented the list of 42 candidate terms and asked panel members (Figure 2E):

Out of the search terms provided below, which EIGHT search terms would you pick to do the search described previously?

We then identified the 15 most-chosen candidate terms and consolidated them into 6 rough equivalents using the remaining three theme groups from the first question (Figure 2F). For example, one of the 15 popular terms, “does my child have autism?” was considered sufficient to stand in place of another one, “is my child autistic,” to represent theme 3 “Diagnose, diagnosis, assess, identify.”

Pilot experimentation revealed that search results improved in the presence of individual terms rather than sentence grammar or Boolean logic, and that short phrases were often more effective. Search terms were therefore simplified (e.g., “signs of autism in a two year old” was simplified to “autism age 2”; Figure 2G). The final list consisted of the four age-specific terms and the six rough equivalent terms to total 10 terms (Figure 2G).

Search process

In order not to limit our search to individually-tailored results, and to access English-speaking markets outside of the United States, we used Virtual Private Network (VPN) software. We estimated the top 3 countries with the largest internet-using English-speaking populations by multiplying their internet user population (Internet World Stats - Usage and Population Statistics) by the proportion of English speakers there (Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia). These were the United States, India, and Nigeria. However, at that point in time, commercially-available VPN software did not offer access to Nigeria, so we replaced it with the next largest, the United Kingdom. Australia and Canada were added for their known product development in mHealth screening for Autism, for a total of 5 countries.

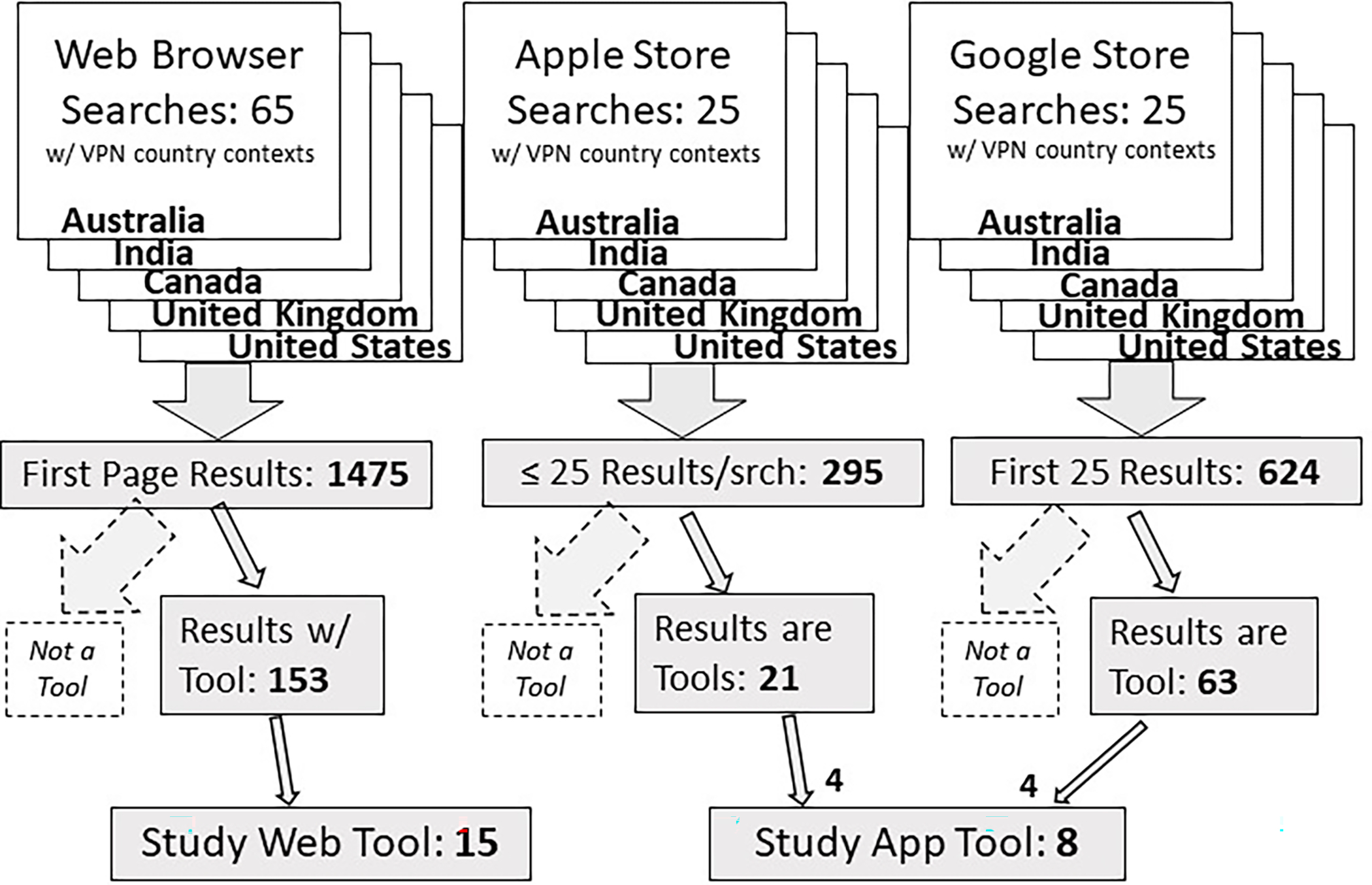

We identified Chrome and Google Search as the predominant browser and search engine worldwide using market data (StatCounter). Fifty searches were conducted in October and November of 2019 to iterate through the diversity of combinations created by 5 countries and 10 search terms. A secondary set of 15 searches (5 countries × 3 best search terms) in the same time period compared results using Bing, a second major search engine. To simulate realistic conditions, only the first page of search results was used (~23 results per search, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

mHealth Autism Screening: search strategy VPN = Virtual Private Network

Once we identified Apple iOS and Google Android as the predominant mobile operating systems (International Data Corporation), we conducted a similar search within mobile app stores from devices running iOS and Android. The 5 most productive terms from the web searches used in 5 VPN country contexts each produced 25 more searches per store, or 50 additional searches (Figure 3). To simulate realistic conditions, we included up to the first 25 results. Data for all search results were collected in a Microsoft Access 2016 database. From the web or mobile application results, ASD screening tools were identified using study inclusion criteria. We noted the ages of children for which each tool was designed, if available, and whether the app was updated or website copyrighted in the last 2 years.

Assessment of tool attributes informing Access, Uptake, and Adherence Inequality

We then recorded preliminary attributes of these tools under themes of Access, Uptake, and Adherence as described by Veinot and colleagues (2018) and in Figure 1. As previously mentioned, Access refers to a user’s environment and device, or the “channels” by which a person might be offered a tool. For our purposes, the themes Uptake and Adherence refer to finding/loading an ASD screening tool and using the tool, respectively. Attributes likely to affect a tool’s Effectiveness will be reported in a subsequent publication.

Access

We first noted tool attributes relevant to environmental and technological channels of access to a digital ASD screening tool. We noted which VPN “countries” in which we found tools. We labeled tools as “Free version available” if they were available without a use fee, and we labeled as “Publicly available” tools that did not require permission from the sponsors in order to function. We noted whether mobile apps were available on each of Android and Apple app stores.

Uptake

We next noted search yield and attributes relevant to finding and loading a digital ASD screening tool. We counted the number of clicks required to arrive at a tool from a web link, for how many web links did search providers receive commission for listing (known as “sponsored”), and how many apps were games. We counted as “registration required” any tools that required the user to create a login account before their use. We noted which ones required ongoing cellular or Wi-Fi data connections to function once they were loaded or installed.

Adherence

We then identified attributes associated with using a digital ASD screening tool. We labeled tools as “User must submit additional personal data for results” if, once completing the questions, the tool withheld the results until the user entered more information about themselves such as an email address. We noted the presence of advertisements or promotion of services, including those in the screen margins and those integrated into tool content itself. To approximate readability, we measured the Flesch-Kincaid estimated reading grade level of the first 5 questions and their corresponding answer options, combined with text from each tool’s results. We noted which tools were available in languages other than English.

Results

Search results

Four terms (Figure 4) were most likely to identify any tools (with mean number of tools per search): “autism quiz” (7.8), “autism screening tool” (4.0), “does my child have autism” (3.6), and “autism toddler” (2.6). Study searches yielded no new tools after these four terms were used in the United States and the United Kingdom. Bing Search results were similar to those from Google Search.

Figure 4.

mHealth Autism Screening: search yield of most effective terms across all 65 web searches

Overall, about three-fifths of searches contained ASD screening tools, and 1 out of 10 links or apps were ASD screening tools. Many individual results across all searches led to relatively few screening tools; 15 unique websites and 8 unique apps meeting study criteria were ultimately identified (Table 1). Sixteen tools (10 web, 6 mobile app) specified a target age range. Websites offered more tools designed for preschoolers 3 – 5 years old (web 5/10, 50%; mobile 1/6, 17%) but a similar number of tools for older children 6 and up (web 6/10, 60%; mobile 4/6, 67%). Mobile apps included toddlers 3 and under more often (web 4/10 40%, mobile 5/6, 83%). A majority of the 8 apps and 15 websites had been updated or copyrighted in the past two years. Three tools (13%) were versions of the commonly used Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT).

Table 1.

mHealth Autism Screening: Tool attributes. Rendered as number of tools (percent) unless otherwise noted.

| Tool Attribute | Mobile App | Web | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 8 | 15 | 23 |

| Intended child age, mean lower/upper bound in years¤ | 1.9/10 | 3.4/9.6 | 2.8/9.7 |

| App updated or website copyrighted in last 2 years | 5 (63%) | 14 (93%) | 19 (83%) |

| Found in all 5 VPN country settings† | 8(100%) | 9 (60%) | 17 (74%) |

| Free version available | 6 (75%) | 12 (80%) | 18 (78%) |

| Publicly Available | 6 (75%)‡ | 15 (100%) | 21 (91%) |

| Android, Apple compatible | 6 (75%), 5 (63%) | n/a | n/a |

| Registration Required for use | 2 (25%) | 1 (7%) | 3 (13%) |

| Internet (cell/wifi) required once tool loaded/installed | 5 (63%) | 15 (100%) | 20 (87%) |

| User must submit additional personal data for results | 2 (25%) | 6 (40%) | 8 (35%) |

| Displays Ads/promotes services | 0 (0%) | 8 (53%) | 8 (35%) |

| Mean reading grade level (range)§ | 6.9 (5 – 11) | 9.8 (5 – 16) | 8.9 (5 – 16) |

| Language other than English offered | 3 (38%) | 7 (47%) | 10 (43%) |

H Based on the 6 mobile apps and 10 web tools that specified age range.

Only up to the first 25 results of each search were considered in order to simulate real-world conditions. VPN = Virtual Private Network

The remaining 2 tools may be downloaded, but require permission from developer or healthcare client to unlock.

Flesch-Kincaid Reading Grade Level of text from first 5 questions/answers combined with total results.

Tool attributes informing Access, Uptake, and Adherence Inequality

Access

All mobile app tools were found in all 5 VPN country settings, whereas only 60% (9/15) of web tools were found in all 5. Most tools were available free and functioned without specific permission (publicly available). Five tools (2 mobile app and 3 web) charged user fees, four of which cost $0.99 - $1.99. The fifth tool required specific permission for use from the sponsoring clinic, and the clinic then would submit a $30 per-use payment to the tool developer. Two mobile app tools were only available on Android, and 3 only on Apple iOS, leaving 3 of 8 apps (38%) offered on both (Table 1).

Uptake

At the level of a whole search (each producing up to 25 individual links or apps), 57% (37) of 65 web searches and 58% (29) of 50 app searches produced a link or app that was an ASD screening tool. At the level of individual results (links or apps produced by searches) pooled from all searches, 10% (153) of 1,475 links and 9% (84) of 919 apps were an ASD screening tool. Forty-five percent (66/147) of links to tools required more than one click to arrive at the tool. Eighteen percent (270/1475) of all links were sponsored, and 22% (204/919) of all apps were games. Most apps did not require registration to use (Table 1). All web tools and a majority (5/6, 63%) of mobile app tools required continuous internet access for use.

Adherence

The user must submit more information about themselves to get their results for 35% of tools (Table 1). Many websites (53%) contained advertisements or solicitations. Ads included prescription medications, clothing, a magazine subscription, an IQ test, and books produced by the website’s host. Some tools invited users to pay to “chat online with a licensed therapist.” Investigators testing 3 tools were solicited repeatedly—using the email address required to receive original ASD screening results—for additional ASD-related paid services. The mean reading grade level was 8.9—which corresponds to about an 8th grade reading level—and was higher in websites than mobile apps. Most tools (57%) offered only English versions. The remainder offered translations most often in Spanish (6 tools) and French (3). Two tools offered 10 and 12 additional languages such as Arabic, Chinese, French, and Portuguese. Two websites with the M-CHAT-R contained links to mchatscreen.com with 72 translations into 48 languages.

Discussion

This simulation of a hypothetical parent’s search for web based or mobile app tools to assess their child’s likelihood of an ASD provides a view into what parents may encounter on their own devices. Our results suggest that a parent attempting this task must at least be persistent, given that they would have to look at about ten individual results to find any tool, that some search terms are much less effective than others, and that for two out of five searches they would not find any tool. Along the way they would have to click through multiple browser pages to access many web tools, and a fifth of their individual search results would be games or “sponsored” (commercially-paid) links. Once they find a tool, it would need continued internet access to function. In addition, they would find that many mobile apps only work on Android or Apple, but not both.

Challenges accessing these mHealth ASD screening tools might be particularly acute in parents of Color, of lower educational attainment, or with limited English proficiency. This is a particular concern since these are social groups that are already underserved in access to ASD diagnostic and treatment services. For instance, frequent encounters with commercial enticements and requirements to submit an email address to access tool results are likely to erode a parent’s sense of a tool’s trustworthiness or respect for privacy. This might be a particular challenge for families of Color, who might already be less trusting of conventional health resources. Likewise, parents and caregivers with limited literacy are very likely to encounter text they do not understand, which could limit their ability to use available tools. Finally, digital ASD screening tool options may be limited for those with limited English proficiency, although we did not initiate similar searches in other languages in this study.

As suggested in the conceptual model, equitable access, uptake, adherence, and effectiveness are essential for mHealth resources to support underserved families, and each of the issues identified above could alone prevent a tool’s benefit from reaching such families. While we find the free public availability of many tools encouraging, the barriers we document here suggest that existing digital ASD screening resources, as a group, lack many qualities necessary to reduce inequities in ASD detection.

The conceptual model lists precautions for each inequality category. These study results inform specific precautions for website and app developers to consider. Access related precautions should include offering tool versions compatible with older and less expensive devices running both Android and Apple operating systems, and offering “data-lite” versions for use with limited access data plans. Uptake related precautions should include hosting curated “useful links” webpages optimized for common search engines that list ASD screening tools, and including plain-language disclosure of sponsorship & data usage. Precautions to mitigate inequalities in Adherence should include offering more tools in multiple languages, and using universal precautions for literacy burden (DeWalt et al., 2011). A few additional precautions merit mentioning here, despite lying beyond the scope of this study. The first is portrayal of a diversity of families within the tool’s imagery and cultural references (Uptake precaution). Another is the practice of participatory, user-centered tool design that includes members of underserved communities during tool development (Adherence precaution). Lastly, study of a tool’s efficacy among specific underserved groups is needed (Effectiveness precaution), using equity-oriented evaluation and reporting techniques.

Our results follow patterns similar to other published studies. For example, Virani et al. searched Google Play for apps designed for parents of infants, and excluded 72 of the initial 175 apps that met study criteria due to “insufficient free features (n=25), lack of credible information/sources (n=24), excessive advertisements (n=19), and demand[ing] unnecessary personal information (n=4)” (Virani, Duffett-Leger, & Letourneau, 2019). Of the final 16 apps remaining after other exclusions, all were free, most were available on both iOS and Android platforms, and half were free of advertisements. Taki et al. searched for websites and mobile apps on infant feeding and found most of them to be non-commercial, and most of them to have poor quality. Their Flesch-Kincaid reading grade levels had a median of 9 for websites and 8 for apps (Taki et al., 2015). The Joint Commission and others have historically recommended that patient education materials be rendered at no more than a 5th grade reading level (Stossel, Segar, Gliatto, Fallar, & Karani, 2012).

Strengths of this study include its comprehensive search strategy, stakeholder engagement, and grounding in an eHealth equity conceptual model. This model is important among literature on the digital divide and health because it distinguishes between barriers to Access, Uptake, Adherence, and Effectiveness of a digital health intervention that pertain to health inequities. Furthermore, Veinot and colleagues (2018) offered precautions to mitigate inequalities in each of these four categories. Our use and extension of the model further adapts those mitigation strategies to mobile health screening tools and suggests precautions based on study outcomes. It may be useful for other researchers seeking an equity-oriented framework to develop and understand mHealth screening tools for autism or other chronic conditions.

This study contributes to ASD literature by examining characteristics of mobile ASD screening tools that may generate ASD inequity rather than reducing it. If developers of future mHealth ASD screening tools take precautions we describe here starting at the product development stage, such tools could reduce ASD inequities. This is especially relevant considering the post-pandemic ubiquity of internet use for child health and development.

This study is limited by its hypothetical nature; observing parents conduct their own searches—although beyond our capacity in this study—might produce more accurate results. Second, a diversity of user circumstances informs the digital divide and inequities in ASD detection; we assess a few basic characteristics of these ASD screening tools that cannot fully represent their significance. For example, the Flesch-Kincaid formula, based only on word syllables and sentence length, cannot fully assess comprehensibility. Third, our sample was not comprehensive since some English markets were omitted due to sampling only five countries and a lack of VPN access (e.g., Nigeria). On the other hand, we find it notable that three quarters of tools were found in all 5 VPN country contexts, and within the countries we searched, no new tools emerged after searching the United States and the United Kingdom. Fourth, readers should remember that websites and mobile apps change frequently and these results represent a discrete window in time (late 2019).

Next steps for this research include an evaluation of tool quality, qualitative study of stakeholder experience with these screening tools, and comparative usability testing including families in marginalized groups. Knowledge developed from this research may inform evaluation methods and application design standards for other digital tools that screen children for developmental and behavioral conditions.

Although digital resources hold promise to improve access to ASD identification in theory, here we document numerous challenges that a concerned parent would encounter while trying to assess their child’s likelihood of having the condition. These results help us understand the digital divide and its relationship with early detection of ASD. Digital tools designed to increase access to timely identification of ASD for marginalized families may have the opposite effect if they do not address the types of barriers we describe here.

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health R21MH120349-01. BS involvement was supported by a National Library of Medicine training grant 5T15LM007088. LRV and YM involvement was supported by National Institutes of Health Common Fund and Office of Scientific Workforce Diversity grants UL1GM118964, RL5GM118963, and TL4GM118965.

Footnotes

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- DeWalt DA, Broucksou KA, Hawk V, Brach C, Hink A, Rudd R, & Callahan L (2011). Developing and testing the health literacy universal precautions toolkit. Nursing Outlook, 59(2), 85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2010.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SL, Levy SE, & Myers SM (2020). Identification, Evaluation, and Management of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Pediatrics, 145(1), e20193447. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Data Corporation. (2021). IDC - Smartphone Market Share - OS. Retrieved from https://www.idc.com/promo/smartphone-market-share/os

- Internet World Stats - Usage and Population Statistics. (2021). Top 20 Countries with the Highest Number of Internet Users. Retrieved from https://www.internetworldstats.com/top20.htm

- Kubb C, & Foran HM (2020). Online Health Information Seeking by Parents for Their Children: Systematic Review and Agenda for Further Research. J Med Internet Res, 22(8), e19985. doi: 10.2196/19985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latulippe K, Hamel C, & Giroux D (2017). Social Health Inequalities and eHealth: A Literature Review With Qualitative Synthesis of Theoretical and Empirical Studies. J Med Internet Res, 19(4), e136. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkin PH, Macias MM, Baer Chen B, Coury D, Gottschlich EA, Hyman SL, . . . Levy SE. (2020). Trends in Pediatricians’ Developmental Screening: 2002–2016. Pediatrics, 145(4). doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maenner MJ, Shaw KA, Bakian AV, Bilder DA, Durkin MS, Esler A, . . . Cogswell ME. (2021). Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years - Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2018. MMWR Surveill Summ, 70(11), 1–16. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7011a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2021). Mobile Fact Sheet. Internet & Technology. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/

- Real FJ, DeBlasio D, Rounce C, Henize AW, Beck AF, & Klein MD (2018). Opportunities for and Barriers to Using Smartphones for Health Education Among Families at an Urban Primary Care Clinic. Clinical pediatrics, 57(11), 1281–1285. doi: 10.1177/0009922818772157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C (2017). Computer and Internet Use in the United States: 2016. Retrieved from Washington, DC: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2018/acs/ACS-39.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Shaw J, Brewer LC, & Veinot T (2021). Recommendations for Health Equity and Virtual Care Arising From the COVID-19 Pandemic: Narrative Review. JMIR Form Res, 5(4), e23233. doi: 10.2196/23233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StatCounter. (2021). Search Engine Market Share Worldwide. Retrieved from https://gs.statcounter.com/search-engine-market-share [Google Scholar]

- Stossel LM, Segar N, Gliatto P, Fallar R, & Karani R (2012). Readability of Patient Education Materials Available at the Point of Care. Journal of general internal medicine, 27(9), 1165–1170. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2046-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan D (2018). How Google autocomplete works in Search. Retrieved from https://blog.google/products/search/how-google-autocomplete-works-search/

- Taki S, Campbell KJ, Russell CG, Elliott R, Laws R, & Denney-Wilson E (2015). Infant Feeding Websites and Apps: A Systematic Assessment of Quality and Content. Interact J Med Res, 4(3), e18. doi: 10.2196/ijmr.4323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veinot TC, Mitchell H, & Ancker JS (2018). Good intentions are not enough: how informatics interventions can worsen inequality. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 25(8), 1080–1088. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virani A, Duffett-Leger L, & Letourneau N (2019). Parenting apps review: in search of good quality apps. mHealth, 5, 44. doi: 10.21037/mhealth.2019.08.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis KE, Guthrie W, Bennett AE, Gerdes M, Levy SE, Mandell DS, & Miller JS (2020). Adherence to screening and referral guidelines for autism spectrum disorder in toddlers in pediatric primary care. PLoS One, 15(5), e0232335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia. (2021). List of countries by English-speaking population. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_English-speaking_population

- Zuckerman KE, Chavez AE, Wilson L, Unger K, Reuland C, Ramsey K, . . . Fombonne E. (2020). Improving autism and developmental screening and referral in US primary care practices serving Latinos. Autism, 1362361320957461. doi: 10.1177/1362361320957461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwaigenbaum L, Bauman ML, Fein D, Pierce K, Buie T, Davis PA, . . . Wagner S. (2015). Early Screening of Autism Spectrum Disorder: Recommendations for Practice and Research. Pediatrics, 136(Supplement 1), S41. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3667D [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]