Abstract

Childhood obesity is a precursor to future health complications. In adults, neighborhood walkability is inversely associated with obesity prevalence. Recently, it has been shown that current urban walkability has been influenced by historical discriminatory neighborhood disinvestment. However, the relationship between this systemic racism and obesity has not been extensively studied. The objective of this study was to evaluate the association of neighborhood walkability and redlining, a historical practice of denying home loans to communities of color, with childhood obesity. We evaluated neighborhood walkability and walkable destinations for 250 participants of the Healthy Start cohort, based in the Denver metropolitan region. Eligible participants attended an examination between ages 4 and 8. Walkable destinations and redlining geolocations were determined based on residential addresses, and a weighting system for destination types was developed. Sidewalks and trails in Denver were included in the network analyst tool in ArcMap to calculate the precise walkable environment for each child. We implemented linear regression models to estimate associations between neighborhood characteristics and child body mass index (BMI) z-scores and fat mass percent. There was a significant association between child BMI and redlining (β: 1.36, 95% CI: 0.106, 2.620). We did not find an association between walkability measures and childhood obesity outcomes. We propose that cities such as Denver pursue built environment policies, such as inclusionary zoning and direct investments in neighborhoods that have been historically neglected, to reduce the childhood health impacts of segregated poverty, and suggest further studies on the influences that redlining and urban built environment factors have on childhood obesity.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11524-022-00703-w.

Keywords: Obesity, Pediatric, Redlining, Walkability, GIS, Built environment, Equity

Introduction

The prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents (ages 2–19 years) in the USA has reached 18.4%, approximately 13.7 million individuals. [1] Childhood obesity has considerable ramifications for the current and future health of children [2]. Children affected by obesity are more likely to experience obesity as adults because physical activity and dietary habits formed in early life are often maintained in adulthood [3]. Furthermore, obesity in childhood is associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol, and mental health implications; [2, 4] these effects may persist well in to adulthood [4].

The built environment can play an important role in obesity prevention in childhood by promoting daily physical activity, [5] and walkability is an important aspect of the built environment [6]. Among adults, safety and mixed land use are two of the best predictors of active transportation (i.e., walking or biking to a work or school location) and recreational walking [7]. Other features of the built environment, such as the density of certain destinations in a neighborhood and proximity to sidewalks, parks, playgrounds, and recreation facilities, may promote walking in childhood [8, 9]. Our current knowledge about lifelong health implications of childhood obesity, coupled with an expanded understanding of neighborhood factors that impact obesity, can contribute to policies and practices that create environments that support healthy weights in children.

Despite the inverse associations between neighborhood walkability and obesity, there are still several important gaps in our knowledge. First, many previous neighborhood-built environment studies investigated indicators at the census tract level or did not study child health outcomes for young children (age 4–8) when spatial buffers were used as a walkability proxy [10, 11]. The use of precise geolocations of walkable destinations within a buffer around an individual’s address provides a more refined measurement of walkability than administrative boundaries, despite the risk of spatial misclassification both methods pose [12, 13]. Additionally, existing research examining associations between walkability and obesity have mixed results or do not focus exclusively on young children [14]. Because young childhood health outcomes are rarely studied in relation to walkability, assessing if the walkability of neighborhoods is associated with childhood obesity and fat mass percent, and which neighborhood factors are most strongly linked to this phenomenon, can allow us to design more equitable and health promoting neighborhoods for childhood development.

Historical neighborhood-level housing discrimination practices, including redlining, still have present-day health and equity implications, particularly relating to the neighborhood-level built environment and residential wealth. The physical and socioeconomic composition of current neighborhoods has been influenced by redlining, largely represented by low-income Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) [15]. The term “redlining” comes from the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) categorization, where “at-risk,” largely BIPOC neighborhoods were highlighted in red on city maps. [15] Individuals who resided in redlined neighborhoods were denied access to loans by local banks, limiting BIPOC home ownership and future wealth creation [15]. While walkable destinations are an important aspect of walkability, the quality of the built environment in redlined neighborhoods can result in less walking, even in the presence of destinations [16].

The long-term health and wellbeing outcomes of residents in formerly redlined neighborhoods is an emerging area of study and is primarily limited to studies of adult health outcomes [17]. A multi-dimensional mechanism may exist for redlining practices resulting in higher rates of childhood obesity. Prior research demonstrated that sustained disinvestment at the neighborhood level over the course of 80 years is associated with poor neighborhood health outcomes [18]. Allostatic load is the physiological “wear and tear” that can result from the daily stress of experiencing social and environmental burdens, particularly segregation and racism [19]. Allostatic load has been associated with higher rates of obesity and other chronic diseases in adults. Additionally, historical redlining is associated with present-day air pollution disparities in US cities, and air pollution exposure is a potential environmental obesogen that has been associated with early childhood obesity risk [20]. Further, historically redlined neighborhoods tend to have fewer trees, resulting in higher temperatures and less protection from the elements, potentially resulting in less walking and physical activity [16]. Uncovering if historic redlining practices impact childhood obesity outcomes will allow for a better understanding of areas for intervention for built environments and associated social contexts.

To address current gaps in knowledge, we conducted a novel exploration of built environment characteristics and the associations with childhood obesity by investigating the precise walkable environment of each child in our cohort. We adapted a method to understand factors that are associated with adult walkability to children in the Healthy Start cohort in Denver, Colorado [16]. Our study objective was to understand the magnitude of associations among neighborhood walkability, historical redlining practices, and childhood obesity in Denver. Our hypothesis was that higher walkability scores would be associated with lower rates of overweight and obese BMIs and fat mass percentages in the cohort and that children living in historically redlined neighborhoods will have higher rates of overweight and obese BMIs and fat mass percentages.

Methods

Study Population and Area

Data for this analysis were obtained from the Healthy Start study, a pre-birth cohort based in the nine-county Denver metropolitan area. Since 2009, Healthy Start has been investigating risk factors for childhood obesity and other health outcomes. Study design and recruitment have been previously described [16]. Briefly, pregnant women aged 16 or older expecting singleton births were recruited from the University of Colorado Hospital outpatient obstetrics clinics between 2009 and 2014. Postnatally, children aged 4 and 8 years were invited to participate in a follow-up visit at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus [21, 22]. The Healthy Start study protocol was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

The study area for this analysis was limited to the City and County of Denver. Due to the varying nature of walkable landscapes in urban, suburban, and rural settings that comprise the entire Healthy Start catchment area, limiting the study area to Denver County allowed us to evaluate urban walkability. In addition, unlike surrounding counties that also include Healthy Start participants, extensive and reliable spatial data was available for Denver. The original Healthy Start cohort had 1410 mother–child dyads. We included participants who underwent a visit between the ages of 4 and 8 and had a known address in Denver, Colorado.

Outcome Measurement

Healthy Start participants underwent body composition measurements to assess fat mass percent and body mass index (BMI). Both outcome measurements were obtained with a BOD POD (Cosmed, Italy), a body composition tracking system, also known as an air-displacement plethysmograph [23]. The BOD POD calculates whole-body density to determine body composition [23]. The BOD POD works under the same principles as hydrostatic (underwater) weighing; except instead of measuring the volume of water being displaced, it measures the volume of air in the chambers [24]. The BOD POD produces estimates of total fat mass and fat-free mass. We calculated fat mass percent as fat mass/total body mass [25]. Height and weight were also measured, and BMI-for-age z-scores were calculated based on the World Health Organization’s Child Growth Standards [26].

Exposure Assessment

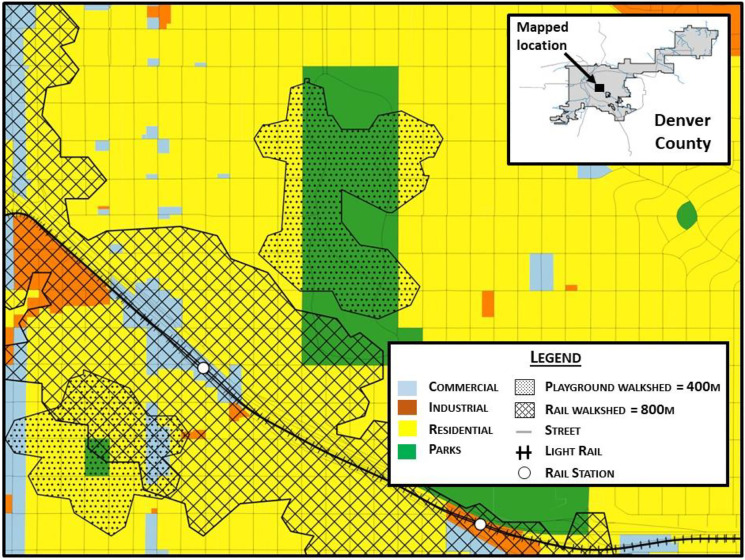

Participant addresses at the time of their age 4- to 8-year-old visit were geocoded to rooftop locations using ArcMap 10.7.1. Geospatial data of walkable destinations within the study area were collected from Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, City of Denver Open Data Catalog, assessor’s data, and Regional Transportation District (see supplemental Table 1). Utilizing trail and sidewalk geolocation from the City of Denver Open Data Catalog as the “network,” we used the Network Analyst extension in ArcMap 10.7.1 to develop walkability scores for each child based on their address location and walk-shed, or the area around a home that is reachable on foot for the average person, of 400 and 800 m from the child’s address (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Service areas, or “walk-shed,” of 400 and 800 m around playgrounds and light rail stations, Health Start cohort, Denver, CO

Since most existing methodologies to assess walkability were developed for adult populations, we tailored our destination type and weighting system specifically to children based on the existing literature on childhood obesity, environmental health, and walkability. Access to safe recreation, healthy food, schools, and social connection are important built environment factors that influence walking for children [7]. To measure walkability for children, we developed three exposure measures: unweighted, density, and weighted walkability scores.

Each destination was assigned a value of one to create unweighted scores, with higher address scores indicating a greater concentration of destination types within 400 m of a participant’s home via sidewalks or trails [27–29]. Transportation and elementary schools were included at 800 m away from participant homes as literature suggests that people are willing to walk further for these destination types [12, 30]. The density score was calculated as a count of all walkable destinations near each address, regardless of type. Assigning weighted walkability scores to study participants allowed us to explore a combination of social and built environment characteristics and historical influences. Each destination included in the weighting system was associated with walking, protection against obesity, or both. For some destinations included in our study, associations in favor of childhood walking or obesity status have not yet been studied, so results from adult studies were extrapolated for use in rationale for the weighting system. Table 1 shows the weighting criteria along with the total weighted score for each destination type. The weighting criteria were assigned higher scores if a criterion was more strongly associated with reduced obesity in children (e.g., primary food access received ten points, while daily transportation only contributed one point toward each participant’s total weighted scores). Rationale for the inclusion of destination types (Table 1) is briefly described below (see Supplemental Table 2 for the development of the weighting system).

Table 1.

Criteria and destination types selected as walkability score inputs, rationale for inclusion, and supporting citations

| Criteria | Destination types | Rationale | Supporting literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Associated with promoting walking | Grocery stores, playgrounds, neighborhood parks |

1. Accessibility of food vendors contributes to walking behavior 2. Adults living within a half mile of a park visit parks and exercise more often 3. Park and playground proximity increases the likelihood that a child will engage in physical activity at the location |

Cerin et al., 2011 [31] Dunton et al., 2014 [32] State Indicator Report on Physical Activity, 2014 [33] |

| 2. Primary food access | Grocery stores |

1. Availability of healthy food choices contributes to weight status 2. National data in the USA suggest that long-term exposure to their food environment could affect childhood obesity risk |

Jia et al., 2019 [34] Cerin et al., 2011 [35] Galvez et al., 2009 [36] |

| 3. Promotes active commuting | Elementary schools, playgrounds, recreation facilities, bus stops |

1. Nearby destinations promote walking and other forms of active commuting, particularly in denser urban 2. Nearby public transportation is associated with more walking |

Freeland et al., 2013 [37] |

| 4. Promotes physical activity | Parks, playgrounds, recreation facilities |

1. Availability of parks is associated with higher levels of physical activity among children and adolescents 2. Positive associations between play equipment and children’s physical activity levels established in literature 3. Greater neighborhood park and recreation areas are associated with greater physical activity |

Floyd et al., 2011 [38] Broekhuizen et al., 2014 [39] Roemmich et al., 2006 [40] |

| 5. Entertainment and social connection | Restaurants, entertainment facilities, parks |

1. The social context of eating may be an important contributor to the development and maintenance of obesity 2. Social networks, coupled with the environment, influence the adoption of obesity related behaviors |

Higgs and Thomas, 2016 [41] Serrano Fuentes et al., 2019 [42] |

| 6. Additional food access | Farmers’ markets, community gardens, food pantry | 1. Access to healthy food can reduce the risk of childhood obesity | Le et al., 2016 [43] |

| 7. Rapid transportation | Light rail station | 1. Fast, nearby public transportation increases likelihood that residents will meet physical activity guidelines | University of British Columbia, 2009 [44] |

| 8. Free service | Libraries | 1. Libraries and other free services ca n help to improve health literacy at young ages, potentially contributing to lower obesity outcomes | Tarver et al., 2016 [45] |

| 9. Medical service | Medical care | 1. Access to medical intervention can improve weight status in adults and children | Heymsfield et al., 2018 [46] |

| 10. Daily transportation | Light rail station, bus stops | 1. An increase in mass transit ridership is associated with lower obesity rates in counties across the United States | She et al., 2019 [47] |

Because healthy food is an important protective factor against obesity in children, stratification of food store and restaurant types was conducted to add more sensitivity to the models [34]. Convenience stores and fast-food chains were designated as “unhealthy food options,” while grocery stores, farmers markers, and other restaurant types were categorized as “healthy food options.” [34] A healthy eating index score was generated for each child in the study based on familial eating habits and was included to adjust for personal food consumption as opposed to neighborhood food availability. Other neighborhood factors such as crime are potentially important influences on the prevalence of neighborhood walking. Crime rates likely play a role in the perceived safety of a neighborhood and may confound the association between walkable destinations and obesity; therefore, we included aggregate geospatial crime data from the City of Denver in our analysis to determine the majority crime type in each participant’s neighborhood. [48, 49]

Redlining data were obtained through the mapping inequality tool, a collaborative project between teams at the University of Richmond, Virginia Tech, and the University of Maryland that digitized historical redlining maps to be utilized in research and decision making (see Fig. 2 below for the original map of Denver, CO). [50–52] This tool allowed us to download a shapefile of historically redlined districts in Denver and assign a redlining grade (A, B, C, D, with D being the “redlined” neighborhoods) to study participants based on their residential addresses using ArcMap 10.7.1. [50].

Fig. 2.

Original HOLC map of Denver, Colorado

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics including means, standard deviations, medians, and ranges were used to characterize the exposures, outcomes, and covariates. As the two outcome variables selected for this study (fat mass percent and BMI) are continuous measures, histograms and other appropriate frequency distribution methods were used to examine the outcome variables [25]. Univariable analyses were conducted to understand the missingness and range of each variable and to summarize each of the outcome and covariate variables as means and standard deviations (for continuous variables) or frequencies and percentages (for categorical variables) as appropriate. Age- and sex-adjusted BMI z-scores were utilized to account for the differing typical BMI ranges throughout childhood development [53].

Separate multivariable linear models were implemented to evaluate the relationship between BMI, fat mass percent, and neighborhood redlining and walkability. Covariates for the models were selected as indicators of socioeconomic status, potential walkability confounders, and variables that would add precision to models. The covariates that were tested for confounding and precision for inclusion in our models were obtained from the Healthy Start data set (child age, race, sex, maternal education level, housing type, Internet access, maternal BMI, and healthy eating index score) or publicly available data sources (HOLC redlining grade (if applicable to address), streetlight density, healthy and unhealthy food density, and major neighborhood crime offenses) (see Supplemental Table 1 for all external data sources). The Healthy Start Study racial categories follow categorization from the United States Census [54].

Spatial autocorrelation of the outcome measurements was assessed through global Moran’s I tests. We prepared a list of weights based on neighboring relationships by taking the square root of n to establish k nearest neighbors. Because spatial autocorrelation was not present in our outcome variables, linear regression models were appropriate for subsequent analysis. In separate univariable linear models, we assessed potential confounding variables by examining the strength of the association between each covariate, exposure, and outcome measurement. Significant precision and confounding variables were considered to have a p value for association with the outcome variable of less than 0.05. The exposure of walkability scores, obesity variables outcome, and the precision variables of healthy eating index, maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, and healthy food density were included as continuous variables, while the exposure of redlining, and confounding variables maternal education (< 12th grade, high school degree/GED, some college/associate’s degree, college graduate, graduate degree), housing type (apartment, duplex, condominium/townhouse, house, mobile home), race (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic other), biological sex (male, female), age (ages, four, five, six, seven, eight), Internet access (yes/no), and majority crime offense (auto theft, burglary, drug and alcohol offenses, larceny, public disorder, theft from motor vehicle, traffic accidents, all other crimes) were included as categorical variables. All statistical analyses were performed in R 4.0.1 (code available upon request).

Results

Characteristics of Study Participants

Of the 1410 pregnant women who delivered live births originally recruited into Healthy Start, 779 participated in the follow-up study visit for their children at ages 4 to 8 years. Of these participants, 31.4% (n = 250) had a known address within the City and County of Denver, Colorado. The mean age of study participants was 4 years old (range: 4–8 years). There were slightly more males than females in the study, 53% and 47% respectively. Almost half of the study population were categorized as non-Hispanic White (45%), with Hispanic (27%), non-Hispanic Black (17%), non-Hispanic other (10%), and missing race (1%) following in frequency. Table 2 presents demographic, neighborhood characteristics, and outcome data of the sample stratified by race. Non-Hispanic White children’s mothers had the most graduate degrees (55.7%), while Hispanic children’s mothers were the most likely to have less than a 12th grade education (30.8%).

Table 2.

Participant demographic, neighborhood, and outcome data by race for Healthy Start participants at 4–8-year-old visit (n = 250)

| Non-Hispanic White (N = 131) | Hispanic (N = 52) | Non-Hispanic Black (N = 55) | Non-Hispanic Other (N = 12) | Overall (N = 250) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 4.22 (0.560) | 4.46 (1.01) | 4.40 (0.735) | 4.36 (0.505) | 4.32 (0.716) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 4.00 [4.00, 7.00] | 4.00 [4.00, 8.00] | 4.00 [4.00, 7.00] | 4.00 [4.00, 5.00] | 4.00 [4.00, 8.00] |

| Missing | 3 (2.3%) | 2 (3.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (8.3%) | 6 (2.4%) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 58 (44.3%) | 29 (55.8%) | 25 (45.5%) | 6 (50.0%) | 118 (47.2%) |

| Male | 73 (55.7%) | 23 (44.2%) | 30 (54.5%) | 6 (50.0%) | 132 (52.8%) |

| Maternal education | |||||

| Less than 12th grade | 3 (2.3%) | 16 (30.8%) | 15 (27.3%) | 1 (8.3%) | 35 (14.0%) |

| High school degree or GED | 4 (3.1%) | 12 (23.1%) | 17 (30.9%) | 6 (50.0%) | 39 (15.6%) |

| Some college or associate’s degree | 7 (5.3%) | 17 (32.7%) | 18 (32.7%) | 3 (25.0%) | 45 (18.0%) |

| Four years of college (BA,BS) | 44 (33.6%) | 6 (11.5%) | 3 (5.5%) | 0 (0%) | 53 (21.2%) |

| Graduate degree (Master’s, Ph.D.) | 73 (55.7%) | 1 (1.9%) | 2 (3.6%) | 2 (16.7%) | 78 (31.2%) |

| Redline grade | |||||

| A | 5 (3.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (8.3%) | 6 (2.4%) |

| B | 22 (16.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) | 0 (0%) | 23 (9.2%) |

| C | 17 (13.0%) | 3 (5.8%) | 5 (9.1%) | 2 (16.7%) | 27 (10.8%) |

| D | 5 (3.8%) | 3 (5.8%) | 9 (16.4%) | 1 (8.3%) | 18 (7.2%) |

| No grade | 82 (62.6%) | 46 (88.5%) | 40 (72.7%) | 8 (66.7%) | 176 (70.4%) |

| Internet | |||||

| Yes | 127 (96.9%) | 40 (76.9%) | 48 (87.3%) | 10 (83.3%) | 225 (90.0%) |

| No | 2 (1.5%) | 12 (23.1%) | 7 (12.7%) | 2 (16.7%) | 23 (9.2%) |

| Missing | 2 (1.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.8%) |

| Home type | |||||

| Apartment | 8 (6.1%) | 12 (23.1%) | 18 (32.7%) | 1 (8.3%) | 39 (15.6%) |

| Duplex | 6 (4.6%) | 2 (3.8%) | 4 (7.3%) | 1 (8.3%) | 13 (5.2%) |

| Condominium/townhome | 4 (3.1%) | 8 (15.4%) | 12 (21.8%) | 3 (25.0%) | 27 (10.8%) |

| House | 108 (82.4%) | 30 (57.7%) | 20 (36.4%) | 7 (58.3%) | 165 (66.0%) |

| Mobile home | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Missing | 5 (3.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (2.4%) |

| Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 24.6 (5.54) | 29.2 (9.72) | 25.9 (6.40) | 24.0 (4.78) | 25.8 (6.98) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 23.1 [18.0, 48.3] | 26.8 [16.3, 62.6] | 23.8 [16.6, 51.9] | 21.8 [18.6, 31.1] | 23.9 [16.3, 62.6] |

| Healthy eating index score | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 61.2 (11.3) | 61.3 (12.7) | 53.6 (12.4) | 58.2 (11.8) | 59.5 (12.1) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 60.4 [34.5, 96.8] | 62.1 [38.4, 87.1] | 54.2 [34.5, 81.6] | 57.9 [40.4, 80.8] | 59.6 [34.5, 96.8] |

| Missing | 15 (11.5%) | 14 (26.9%) | 12 (21.8%) | 2 (16.7%) | 43 (17.2%) |

| Majority neighborhood crime offense | |||||

| All other crimes | 11 (8.4%) | 21 (40.4%) | 25 (45.5%) | 3 (25.0%) | 60 (24.0%) |

| Auto theft | 1 (0.8%) | 5 (9.6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (16.7%) | 8 (3.2%) |

| Burglary | 7 (5.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (2.8%) |

| Drug/alcohol | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.8%) |

| Larceny | 7 (5.3%) | 1 (1.9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (8.3%) | 9 (3.6%) |

| Missing | 2 (1.5%) | 2 (3.8%) | 5 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (3.6%) |

| Public disorder | 5 (3.8%) | 11 (21.2%) | 4 (7.3%) | 0 (0%) | 20 (8.0%) |

| Theft from motor vehicle | 33 (25.2%) | 6 (11.5%) | 5 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) | 44 (17.6%) |

| Traffic accident | 65 (49.6%) | 6 (11.5%) | 14 (25.5%) | 6 (50.0%) | 91 (36.4%) |

| Mean (SD) | 1.05 (1.28) | 0.596 (1.01) | 1.82 (2.53) | 1.33 (1.87) | 1.14 (1.67) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 1.00 [0, 5.00] | 0 [0, 5.00] | 1.00 [0, 9.00] | 0 [0, 5.00] | 0.500 [0, 9.00] |

| Unhealthy food density | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.27 (2.31) | 0.750 (1.22) | 1.89 (3.08) | 1.33 (1.44) | 1.30 (2.32) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 0 [0, 18.0] | 0 [0, 5.00] | 1.00 [0, 19.0] | 1.00 [0, 4.00] | 0 [0, 19.0] |

| BMI Z-scores | |||||

| Mean (SD) | -0.0430 (0.774) | 0.665 (1.98) | -0.112 (0.768) | 0.669 (3.53) | 0.126 (1.37) |

| Median [Min, Max] | -0.0950 [-2.54, 2.23] | 0.355 [-3.29, 7.98] | -0.0650 [-1.98, 1.85] | -0.230 [-1.81, 11.0] | 0[-3.29, 11.0] |

| Missing | 3 (2.3%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (5.5%) | 1 (8.3%) | 7 (2.8%) |

| Fat mass percent | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 19.1 (6.74) | 21.8 (6.53) | 17.4 (5.64) | 18.2 (6.95) | 19.2 (6.61) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 19.1 [0.800, 38.6] | 22.1 [9.85, 37.7] | 17.8 [3.80, 29.5] | 20.2 [2.45, 27.0] | 19.6 [0.800, 38.6] |

| Missing | 14 (10.7%) | 8 (15.4%) | 8 (14.5%) | 1 (8.3%) | 31 (12.4%) |

Exposure Summary

Redline grades were distributed disproportionately by race as well; non-Hispanic Whites were the most likely to live in areas of Denver that historically received a redline grade of “A” or lived in areas of the city that were not redlined by HOLC. Non-Hispanic Black participants were the most likely to live in a neighborhood that historically received a grade of “D.” Non-Hispanic White participants were also most likely to live in a house (82.4%), while non-Hispanic Black participants were the most likely to live in an apartment (32.7%). Pre-pregnancy BMI was highest among mothers who identified as Hispanic (29.2 kg/m2), compared to all other racial categories. The average fat mass percent of the child was also highest among Hispanic participants (21.8%). With respect to the walkability scores, the weighted, unweighted, and density scores were not normally distributed. The median weighted walkability scores were 37 (IQR: 21, 51); unweighted walkability scores had a median of 3 (IQR: 2, 4); and density walkability scores had a median of 5 (IQR: 2, 10). Histograms displaying the walkability score distributions are provided in Supplemental Fig. 1.

Regression Analysis

The Moran’s I statistic for the BMI outcome was − 0.036 (p = 0.943) and 0.00133 for fat mass percent (p = 0.399), which indicated that spatial autocorrelation is not present in the outcome variables and thus did not necessitate use of spatial regression models. Variables that had a statistically significant association with both the exposure and outcome variable (p < 0.05) included in the model were maternal education, child race, home type, redline grade, and majority neighborhood crime offense (Supplemental Tables 3 and 4). Out of all the variables tested for confounding and precision in univariable analyses, none was considered precision variables for our study participants based on statistical significance (p < 0.05); however, age and sex were considered standard adjustment variables. Crude and adjusted regression analyses with the two outcome measures (BMI and fat mass percent) and the three measures for neighborhood walkability (density, unweighted, and weighted) are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Crude and adjusted associations between walkability exposures and BMI z-score and fat mass percent among children in the Healthy Start study

| BMI crude | Fat mass % crude | BMI adjusted* | Fat mass % adjusted* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI |

| Density score | -0.00195 | (− 0.0318, 0.0279) | 0.443 | (− 0.235, 0.527) | 0.0315 | (− 0.0263, 0.0894) | 0.146 | (− 0.235, 0.527) |

| Unweighted score | 0.0367 | (− 0.0607, 0.135) | 0.425 | (− 0.134, 0.312) | 0.0873 | (− 0.263, 0.438) | − 1.07 | (− 0.235, 0.527) |

| Weighted score | 0.00452 | (0.003, 0.0148) | 0.351 | (− 3.42, 1.24) | − 0.0166 | (− 0.0505, 0.0174) | 0.0889 | (− 0.134, 0.312) |

| R2 | 0.403 | R2 | 0.583 |

*Adjusted for age, race, sex, maternal education, redline grade, home type, and majority neighborhood crime offense

The main significant finding of interest is that BMI z-scores are positively associated with redlining; in a crude regression analysis, redline grade “D” was associated with higher BMI z-scores (β = 1.05, 95%CI [0.388, 1.71]). The results of the regression for the BMI adjusted walkability model indicated that this model explained 40.3% of the variance in BMI z-scores (R2 = 0.403, p > 0.05). In both crude and multiple regression analyses as well as separate multiple regression models that independently evaluated the exposure variables, all three walkability measures (density, weighted, and unweighted walkability scores) did not have a significant association with obesity outcomes in our study population Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of univariable linear regression model for redline grades and BMI z-scores among children in the Healthy Start study residing in Denver (n = 250)

| Crude | Adjusted* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Redline grade | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI |

| No grade | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| A | − 0.31275 | (− 1.42, 0.269) | 0.16 | (− 3.7, 8.2) |

| B | 0.187 | (− 0.404, 0.779) | 0.424 | (− 2.17, 3.92) |

| C | − 0.243 | (− 0.804, 0.318) | − 0.121 | (− 2.8, 3.05) |

| D | 1.05 | (0.388, 1.71) | 0.139 | (− 5.12, 2.17) |

| R2 | 0.0317 | R2 | 0.145 |

*Adjusted for age, race, sex, maternal education, redline grade, home type, and majority neighborhood crime offense (Significance for crude redline grade D, p = 0.0337)

Discussion

Despite hypothesizing that walkability is protective against childhood obesity, our study found that neighborhood walkability is not significantly associated with obesity for children aged 4 to 8 [55, 56]. However, there is still promising literature that walkability is associated with lower obesity in older children and adults. [43, 57] In our univariable model, redlining indicated a positive association with obesity, which might have gone undetected in the adjusted model due to the small sample size [10, 36]. Higher BMIs in the grade D neighborhoods strengthens the notion that neighborhood environments play a considerable role in health outcomes [10]. Bower et al. found that Black isolation, or segregation, was significantly associated with higher rates of obesity among Black women when compared to White women, which indicates heightened obesity risk in segregated neighborhoods [58]. Extensive research on the mental and physical health ramifications for children who currently reside in historically redlined neighborhoods is not yet available. However, research suggests that racial composition of redlined neighborhoods is shifting, and there are statistically significant associations between redlining and indicators of population health, such as heightened prevalence of poor mental health and lower life expectancy at birth [59, 60]. Additional investigations of the drivers that might produce higher rates of obesity in children in historically redlined neighborhoods can help us to appropriately intervene in social environments to reduce health disparities in these neighborhoods.

Chronic diseases have now outpaced infectious diseases as the leading cause of death in the world, pointing to the need to address a growing obesity crisis [41]. In 2019, six out of 10 adult Americans had a chronic disease, costing $3.5 trillion in medical expenses; further, chronic diseases were leading cause of death and disability in the USA [61]. Chronic diseases pose challenges related to quality of life and the burden of medical expenses at an individual and societal level. As obesity in adulthood is often rooted in patterns established earlier in childhood, identifying interventions to reduce childhood obesity is a critical public health priority [3]. Healthy Start investigators have identified behavioral, dietary, and demographic risk factors for higher adiposity at birth, including maternal high-fat diet and poor diet [62, 63]; Hispanic/Latina ethnicity [22]; higher dietary inflammatory index [64]; maternal intake of total fat, saturated fat, unsaturated fat, and total carbohydrates during pregnancy [65]; higher consumption of eggs, starchy vegetables, solid fats, fruit, and non-whole grains [66]; higher maternal pre-pregnancy BMI [67]; and combined exposure to secondhand smoke and a lack of exclusive breastfeeding [68]. It is likely that many of these contributors, and not walkability, are strong indicators of early childhood obesity outcomes. These factors are influenced by socioeconomic status, culture, environment, discrimination, and health literacy and education [69, 70]. As these are primarily diet-based indicators, it is also critical to explore factors that promote physical activity, particularly as children age and gain autonomy.

The strength of this study lies in the ability to quantify the immediate walkable environment for each study participant, along with the careful review of existing literature to inform the walkability index. This quantification and asset evaluation of the walkable environment demonstrated that mere availability of locations near a home cannot equate to utilization or access because socioeconomic factors had stronger associations with childhood obesity in our cohort than walkability measures. An additional strength is this is an exceptionally well-characterized cohort in terms of nutrition and behavior. Further, this research serves as a methodology, as well as call for action, for public health research and practice to continue to explore historical geospatial redlining districts and their correlation to current population health outcomes with the use of the mapping inequality tool. While this study of a single city may not be generalizable due to city variation in climate, historical and current urban planning, segregation, and environmental injustice, it serves as a model for replication in other cities and with other health outcomes.

There were several limitations to this study. Our sample size (n = 250) might not be sufficient to identify trends in walkability and associations with childhood obesity. A key weakness of this study was the lack of qualitative data that would allow us to understand the relationship between the presence of walkable locations, social influences, and health behaviors in households as they relate to childhood obesity and other health indicators. We were not able to assess participant residential history that may have resulted in residential exposure misclassification. With the COVID pandemic beginning amid this research project, interviews and focus groups with study participants were not feasible. Our study lacked field validation that would help examine the mechanisms mediating participant built environments and weight outcomes within neighborhoods [71]. It is also possible that families in this study tend to travel beyond their neighborhoods for daily needs and activities, so the built environment and social factors affecting participant physical activity and obesity outcomes could exist partially or entirely beyond their immediate walkable environments [72]. Spatial misclassification is possible when conducting analyses with buffers because the range of neighborhood contexts each participant is exposed to may not be captured with this method [13, 73].

Policy options to mitigate the negative outcomes of concentrated neighborhood poverty and structural inequities, such as inclusionary zoning and direct neighborhood investments in the form of community land-trusts, park and recreation infrastructure, and streetlight installation, should be considered on a community basis [74–77]. Nardone et al. posit that “policy responses must consider how to reverse and repair the legacy of structural racism such as redlining,” pointing to a need for intentional evaluation of historical and current policies that contribute to segregation. Because direct neighborhood investments often lead to gentrification in the USA, policies need to also counteract trends toward displacement of residents who can benefit from these neighborhood investments, such as tax freezes for existing residents or government real estate market control [78]. Affordable housing choices outside of the redlined sections of cities may encourage a reduction of concentrated areas of poverty, thus improving social and built environment attributes that promote healthy behaviors and development for children. [60, 74] Further exploration of the influences of built environment and historically redlined neighborhoods on childhood obesity outcomes is necessary to validate the findings of this study. Cities such as Denver with a history of redlining practices can evaluate and redesign policies that perpetuate the segregating and economically disadvantaging environments established during the redlining era. We know that environmental, social, and economic conditions shape health; addressing historical and current injustices in our urban communities is imperative in our efforts to address the childhood obesity epidemic.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by grant 5UG3OD023248 (PI: Dabelea) from the National Institutes of Health and by RD-839278 (PI: Magzamen) from the US Environmental Protection Agency. Ms. Kowalski was supported by a GRA award from the Colorado School of Public Health. We are grateful to Dr. Kirsten Eilertson and the Graybill Statistical Laboratory at Colorado State University, Josh Reyling and the Colorado State University Geospatial Centroid for technical support on this project, and the staff and the participants of the Healthy Start study for their involvement in the study.

Data Availability

Due to IRB and participant confidentiality, human subjects data are not available for distribution. Redlining data are available through the University of Richmond Mapping Inequality project. All other exposure data sources can be found in Supplemental Table 1. Code is available upon request to the first author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no actual or potential competing interests

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Childhood Obesity Facts. Accessed June 20, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/childhood.html#:~:text=Prevalence%20of%20Childhood%20Obesity%20in%20the%20United%20States&text=The%20prevalence%20of%20obesity%20was,to%2019%2Dyear%2Dolds.

- 2.Flynn MAT, McNeil DA, Maloff B, et al. Reducing obesity and related chronic disease risk in children and youth: a synthesis of evidence with ‘best practice’ recommendations. Obes Rev. 2006;7(s1):7–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiefer K, Shirey L, Summer L. Childhood obesity: a lifelong threat to health. Published online March 2002. Accessed June 20, 2020. https://hpi.georgetown.edu/obesity/

- 4.Hakkak R, Bell A. Obesity and the link to chronic disease development. J Obes Chronic Dis. 2016;1(1). 10.17756/jocd.2016-001.

- 5.Rahman T, Cushing RA, Jackson RJ. Contributions of built environment to childhood obesity. Mt Sinai J Med N Y. 2011;78(1):49–57. doi: 10.1002/msj.20235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang X, Mu L. The perceived importance and objective measurement of walkability in the built environment rating. Environ Plan B Urban Anal City Sci. 2020;47(9):1655–1671. doi: 10.1177/2399808319832305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saelens BE, Handy SL. Built environment correlates of walking: a review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(7 Suppl):S550–S566. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817c67a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saelens B, Sallis J, Frank L, et al. Obesogenic neighborhood environments, child and parent obesity: the neighborhood impact on kids study. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(5):e57–e64. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh GK, Siahpush M, Kogan MD. Neighborhood socioeconomic conditions, built environments, and childhood obesity. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(3). 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0730. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Daniels KM, Schinasi LH, Auchincloss AH, Forrest CB, Diez Roux AV. The built and social neighborhood environment and child obesity: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Prev Med. 2021;153:106790. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manaugh K, El-Geneidy A. Validating walkability indices: how do different households respond to the walkability of their neighborhood? Transp Res Part -Transp Environ. 2011;16:309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.trd.2011.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morphocode. The 5-minute walk. MORPHOCODE. Published November 15, 2018. Accessed April 6, 2021. https://morphocode.com/the-5-minute-walk/.

- 13.Duncan DT, Tamura K, Regan SD, et al. Quantifying spatial misclassification in exposure to noise complaints among low-income housing residents across new york city neighborhoods: a global positioning system (GPS) study. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27(1):67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galvez M, Pearl M, Yen I. Childhood obesity and the built environment: a review of the literature from 2008–2009. Natl Inst Health Public Access. Published online April 22, 2010. 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328336eb6f.

- 15.Nardone A, Chiang J, Corburn J. Historic redlining and urban health today in U.S. cities. Environ Justice. 2020;13(4):109–119. 10.1089/env.2020.0011.

- 16.Hoffman JS, Shandas V, Pendleton N. The effects of historical housing policies on resident exposure to intra-urban heat: a study of 108 US urban areas. Climate. 2020;8(1):12. doi: 10.3390/cli8010012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McClure E, Feinstein L, Cordoba E, et al. The legacy of redlining in the effect of foreclosures on Detroit residents’ self-rated health. Health Place. 2019;55:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynch EE, Malcoe LH, Laurent SE, Richardson J, Mitchell BC, Meier HCS. The legacy of structural racism: associations between historic redlining, current mortgage lending, and health. SSM - Popul Health. 2021;14:100793. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hwa Jung K, Pitkowsky Z, Argenio K, et al. The effects of the historical practice of residential redlining in the United States on recent temporal trends of air pollution near New York City schools. Environ Int. 2022;169:107551. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2022.107551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vrijheid M, Fossati S, Maitre L, et al. Early-life environmental exposures and childhood obesity: an exposome-wide approach. Environ Health Perspect. 2020;128(6):067009. doi: 10.1289/EHP5975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perng W, Francis EC, Schuldt C, Barbosa G, Dabelea D, Sauder KA. Pre- and perinatal correlates of ideal cardiovascular health during early childhood: a prospective analysis in the Healthy Start study. J Pediatr. Published online March 16, 2021. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Sauder KA, Kaar JL, Starling AP, et al. Predictors of infant body composition at 5 months of age: the Healthy Start study. J Pediatr. 2017;183:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fields D, Allison D. Air‐displacement plethysmography pediatric option in 2–6 years old using the four‐compartment model as a criterion method. Obesity. Published online 2012 10.1038/oby.2012.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Dempster P, Aitkens S. A new air displacement method for the determination of human body composition. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27(12):1692–1697. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199512000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perng W, Ringham BM, Glueck DH, et al. An observational cohort study of weight- and length-derived anthropometric indicators with body composition at birth and 5 mo: the Healthy Start study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(2):559–567. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.149617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Child growth standards. Accessed August 29, 2021. https://www.who.int/tools/child-growth-standards/software.

- 27.Riazi NA, Link to external site this link will open in a new window, Blanchette S, et al. Correlates of children’s independent mobility in Canada: a multi-site study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(16):2862. 10.3390/ijerph16162862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Obesity and the built environment among massachusetts children. 10.1177/0009922809336073. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Christian H, Villanueva K, Pereira G, et al. The built environment and children’s physical activity–what is ‘child friendly’? J Sci Med Sport. 2012;15:S254–S255. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2012.11.618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodríguez-López C, Salas-Fariña ZM, Villa-González E, et al. The threshold distance associated with walking from home to school. Health Educ Behav Off Publ Soc Public Health Educ. 2017;44(6):857–866. doi: 10.1177/1090198116688429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cerin E, Frank LD, Sallis JF, et al. From neighborhood design and food options to residents’ weight status. Appetite. 2011;56(3):693–703. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunton GF, Almanza E, Jerrett M, Wolch J, Pentz MA. Neighborhood park use by children. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(2):136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.State indicator report on physical activity, 2014. Published online 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/downloads/pa_state_indicator_report_2014.pdf.

- 34.Jia P, Xue H, Cheng X, Wang Y. Effects of school neighborhood food environments on childhood obesity at multiple scales: a longitudinal kindergarten cohort study in the USA. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1329-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cerin E, Frank LD, Sallis JF, et al. From neighborhood design and food options to residents’ weight status. Appetite. 2011;56(3):693–703. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galvez MP, Hong L, Choi E, Liao L, Godbold J, Brenner B. Childhood obesity and neighborhood food store availability in an inner city community. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(5):339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freeland AL, Banerjee SN, Dannenberg AL, Wendel AM. Walking associated with public transit: moving toward increased physical activity in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(3):536–542. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Floyd MF, Bocarro JN, Smith WR, et al. Park-based physical activity among children and adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(3):258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Broekhuizen K, Scholten AM, de Vries SI. The value of (pre)school playgrounds for children’s physical activity level: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11(1):59. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roemmich JN, Epstein LH, Raja S, Yin L, Robinson J, Winiewicz D. Association of access to parks and recreational facilities with the physical activity of young children. Prev Med. 2006;43(6):437–441. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Higgs S, Thomas J. Social influences on eating. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2016;9:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Serrano Fuentes N, Rogers A, Portillo MC. Social network influences and the adoption of obesity-related behaviours in adults: a critical interpretative synthesis review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1178. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7467-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Le H, Engler-Stringer R, Muhajarine N. Walkable home neighbourhood food environment and children’s overweight and obesity: proximity, density or price? Can J Public Health. 2016;107(1):ES42-ES47. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy2.library.colostate.edu/10.17269/CJPH.107.5347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.University of British Columbia. Public transit users three times more likely to meet fitness guidelines. ScienceDaily. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/03/090326134014.htm.

- 45.Tarver T, Woodson D, Fechter N, Vanchiere J, Olmstadt W, Tudor C. A Novel tool for health literacy: using comic books to combat childhood obesity. J Hosp Librariansh. 2016;16(2):152–159. doi: 10.1080/15323269.2016.1154768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heymsfield S, Aronne LJ, Eneli I, et al. Clinical perspectives on obesity treatment: challenges, gaps, and promising opportunities. NAM Perspect. Published online September 10, 2018. 10.31478/201809b.

- 47.She Z, King DM, Jacobson SH. Is promoting public transit an effective intervention for obesity?: a longitudinal study of the relation between public transit usage and obesity. Transp Res Part Policy Pract. 2019;119:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2018.10.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kneeshaw-Price SH, Saelens BE, Sallis JF, et al. Neighborhood crime-related safety and its relation to children’s physical activity. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2015;92(3):472–489. doi: 10.1007/s11524-015-9949-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Denver Open Data Catalog: Crime. Accessed March 2, 2022. https://www.denvergov.org/opendata/dataset/city-and-county-of-denver-crime.

- 50.Mapping inequality. Accessed April 5, 2021. https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/.

- 51.T-RACES: testbed for the redlining archives of California’s exclusionary spaces. Accessed March 2, 2022. http://t-races.net/T-RACES/.

- 52.CI-BER: cyberinfrastructure for billions of electronic records: about CI-BER. CI-BER. Accessed March 2, 2022. http://ci-ber.blogspot.com/p/about-ci-ber.html.

- 53.Growth reference 5–19 years - BMI-for-age (5–19 years). Published April 18, 2021. Accessed April 18, 2021. https://www.who.int/tools/growth-reference-data-for-5to19-years/indicators/bmi-for-age.

- 54.Bureau UC. About race. The United States Census Bureau. Accessed October 8, 2021. https://www.census.gov/topics/population/race/about.html.

- 55.Yoshinaga M, Miyazaki A, Aoki M, et al. Promoting physical activity through walking to treat childhood obesity, mainly for mild to moderate obesity. Pediatr Int. Published online April 17, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.dos Anjos Souza Barbosa JP, Henrique Guerra P, de Oliveira Santos C, de Oliveira Barbosa Nunes AP, Turrell G, Antonio Florindo A. Walkability, overweight, and obesity in adults: a systematic review of observational studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. Published online August 28, 2019. 10.3390/ijerph16173135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Kowaleski-Jones L, Zick C, Smith KR, Brown B, Hanson H, Fan J. Walkable neighborhoods and obesity: evaluating effects with a propensity score approach. SSM - Popul Health. 2017;6:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bower KM, Thorpe RJ, Yenokyan G, McGinty EEE, Dubay L, Gaskin DJ. Racial residential segregation and disparities in obesity among women. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2015;92(5):843–852. doi: 10.1007/s11524-015-9974-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harshbarger AMP and D. America’s formerly redlined neighborhoods have changed, and so must solutions to rectify them. Brookings. Published October 14, 2019. Accessed October 9, 2021. https://www.brookings.edu/research/americas-formerly-redlines-areas-changed-so-must-solutions/.

- 60.Redlining and neighborhood health. NCRC. Published September 10, 2020. Accessed October 9, 2021. https://ncrc.org/holc-health/.

- 61.Health and economic costs of chronic diseases | CDC. Published April 28, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/costs/index.htm.

- 62.Shapiro ALB, Ringham BM, Glueck DH, et al. Infant adiposity is independently associated with a maternal high fat diet but not related to niacin intake: the Healthy Start Study. Febr 2017. 21(1662–1668). 10.1007/s10995-016-2258-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.A L B Shapiro, J L Kaar, T L Crume, et al. Maternal diet quality in pregnancy and neonatal adiposity: the Healthy Start study. Int J Obes. 2016;40(1056–1062). 10.1038/ijo.2016.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Moore BF, Sauder KA, Starling AP, et al. Proinflammatory diets during pregnancy and neonatal adiposity in the Healthy Start study. J Pediatr. 2017;192:P121–127.E2. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Crume TL, Brinton JT, Shapiro A, et al. Maternal dietary intake during pregnancy and offspring body composition: the Healthy Start study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(5). 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Starling AP, Sauder KA, Kaar JL. Maternal dietary patterns during pregnancy are associated with newborn body composition. J Nutr. 2017;147(7):1334–1339. doi: 10.3945/jn.117.248948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Starling AP, Brinton JT, Glueck DH, et al. Associations of maternal BMI and gestational weight gain with neonatal adiposity in the Healthy Start study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(2):302–309. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.094946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moore BF, Sauder KA, Starling AP, Ringham BM, Glueck DH, Dabelea D. Exposure to secondhand smoke, exclusive breastfeeding and infant adiposity at age 5 months in the Healthy Start study. Pediatr Obes. 2017;12(Suppl 1):111–119. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Meade CD, Stanley NB, Martinez-Tyson D, Gwede CK. 20 years later: continued relevance of cancer, culture, and literacy in cancer education for social justice and health equity. J Cancer Educ. 2020;35(4):631–634. doi: 10.1007/s13187-020-01817-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Campbell MK. Biological, environmental, and social influences on childhood obesity. Pediatr Res. 2016;79(1):205–211. doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhou Q, Zhao L, Zhang L, et al. Neighborhood supermarket access and childhood obesity: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2021;22(S1):e12937. doi: 10.1111/obr.12937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang S, Chen X, Wang L, et al. Walkability indices and childhood obesity: a review of epidemiologic evidence. Obes Rev. 2021;22(S1):e13096. doi: 10.1111/obr.13096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kwan MP. The uncertain geographic context problem. Ann Assoc Am Geogr. 2012;102(5):958–968. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2012.687349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ramakrishnan K, Treskon M, Greene S. Inclusionary zoning: what does the research tell us about the effectiveness of local action? :11. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/inclusionary-zoning-what-does-research-tell-us-abouteffectiveness-local-action

- 75.Hindman DJ, Pollack CE. Community land trusts as a means to improve health. JAMA Health Forum. 2020;1(2):e200149. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Seltenrich N. Just What the doctor ordered: using parks to improve children’s health. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123(10):A254–A259. doi: 10.1289/ehp.123-A254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chalfin A, Hansen B, Lerner J, Parker L. Reducing crime through environmental design: evidence from a randomized experiment of street lighting in New York City. Journal of Quant Criminol. 38(1):127–157

- 78.Zuk M, Bierbaum A, Gorska K, et al. Gentrification, displacement and the role of public investment: a literature review.; 2015. 10.13140/RG.2.2.12408.60168.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Due to IRB and participant confidentiality, human subjects data are not available for distribution. Redlining data are available through the University of Richmond Mapping Inequality project. All other exposure data sources can be found in Supplemental Table 1. Code is available upon request to the first author.