Abstract

Objective:

A holistic understanding of the naturalistic dynamics among physical activity, sleep, emotions, and purpose in life as part of a system reflecting wellness is key to promoting wellbeing. The main aim of this study is to examine the day-to-day dynamics within this wellness system.

Methods:

Using self-reported emotions (happiness, sadness, anger, anxiousness) and physical activity periods collected twice per day, and daily reports of sleep and purpose in life via smartphone experience-sampling, over 28 days as college students (n = 226 young adults; M = 20.2 years, SD = 1.7 years) went about their daily lives, we examined day-to-day temporal and contemporaneous dynamics using multilevel vector autoregressive models that consider the network of wellness together.

Results:

Network analyses revealed that higher physical activity on a given day predicted an increase of happiness the next day. Higher sleep quality on a given night predicted a decrease in negative emotions the next day and higher purpose in life predicted decreased negative emotions up to two days later. Nodes with the highest centrality were sadness, anxiety, and happiness in the temporal network and purpose in life, anxiety, and anger in the contemporaneous network.

Conclusions:

While the effects of sleep and physical activity on emotions and purpose in life may be shorter term, a sense of purpose in life is a critical component of wellness that can have slightly longer effects, bleeding into the next few days. High-arousal emotions and purpose in life are central to motivating people into action, which can lead to behavior change.

Keywords: network analyses, health behavior, ecological momentary assessment, emotions, physical activity

Wellbeing refers to optimal psychological functioning and experience (11), consisting of emotional (e.g., happiness) (12) and eudaimonic components (e.g., purpose in life) (13). Globally, people rate being happy as important (14,15) and cultivating states of wellbeing through positive psychological interventions is policy-relevant and holds the potential to alter population health (11,16–18). Physical activity and sleep have emerged as key modifiable health behaviors that may have both immediate and persistent impacts on wellbeing (19). However, less is known about the temporal associations among emotions and eudaimonic wellbeing in everyday life. We consider how health behaviors (physical activity and sleep) and wellbeing (positive and negative emotions and purpose in life) form a complex dynamic system, reinforcing one another in daily life. We focus on physical activity and sleep because these health behaviors have emerged as strong predictors of depressive symptoms and wellbeing (20), they are highlighted in global population health policies (19,21,22) and expert consensus statements (23–27), and regular physical activity and sufficient sleep are outlined as key objectives of Healthy People 2030 (28). An interesting direction for future research would be to build upon the present work by addressing additional components of wellbeing (e.g., life satisfaction and self-esteem) and by examining clustering with other health behaviors (e.g., substance use) within a network approach.

Physical activity, sleep, and emotional aspects of wellbeing

Both physical activity and sleep support positive emotions and alleviate negative emotions. In highly controlled laboratory studies, physical activity immediately influences emotions (29–32). Experimental evidence consistently shows that physical activity alleviates negative emotions and enhances positive emotions immediately and up to one day following the session (30,32). Likewise, following one night of sleep deprivation in the laboratory, individuals reported increased negative emotions and lower positive emotions relative to mornings following their habitual sleep schedule (33). There exists laboratory evidence to support the bidirectional associations of emotions with physical activity and sleep. Experimentally-induced negative emotions are attenuated following acute exercise (34) and have been associated with increased sleep fragmentation measured using polysomnography (35,36). However, to what extent the processes observed in the laboratory generalize to real-world settings remains an open question (37).

In naturalistic settings, sleep, physical activity, and wellbeing are dynamic, fluctuate within the same person from one day to the next, and demonstrate bidirectional associations. A growing body of research has focused on within-person associations between physical activity and emotions in everyday life (38) using study designs that include intensive repeated measures in situ (39,40). Evidence from studies seeking to replicate laboratory findings is conflicting. Some experience-sampling studies observed increased positive emotions following physical activity (41–45) whereas others have found no such association (34,46–48). Similar mixed findings have been observed for negative emotions, with some studies finding reduced negative emotions following physical activity (42,44) and others finding no association (34,47,49,50). In contrast, studies probing the effects of emotions on subsequent physical activity show that positive emotions and increased arousal have generally predicted increased physical activity over the next few hours (41,47,51,52) whereas negative emotions have predicted a decrease or no change in subsequent physical activity (34,50–52). Many of these studies used self-reported measures of physical activity (41–45,50), including questions adapted from the Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire (34), the duration of physical activity (41,43,45,51), the weekly frequency of physical activity (42), and a 7-point Likert scale of level of physical activity (50,53). A growing number of studies are using a variety of accelerometers to objectively measure physical activity (46–49). Thus, the current evidence for physical activity supporting emotional wellbeing in naturalistic settings is less clear-cut than laboratory findings.

In contrast, the association between sufficient sleep duration (53–55) and adequate sleep quality (53,54,56–58) with elevated next-day positive emotions and lower next-day negative emotions has been consistently observed in experience-sampling studies. Sleep plays an important role in restoring connectivity between brain systems underlying emotion generation (i.e., limbic system) and emotion regulation (i.e., prefrontal cortex) (59). Thus, sleep facilitates neural and cognitive resources to effectively deal with emotional experiences and maintain balance in the face of everyday stressors (55). In general, inadequate sleep leads to a heightened experience of negative emotions and a reduction in positive emotions (60).

Physical activity, sleep, and eudaimonic aspects of wellbeing

Wellbeing not only encompasses the extent to which we feel happy and sad, calm or anxious, but also includes the extent to which we judge our lives to be meaningful (61). The benefits of physical activity and sleep may extend from emotional to eudaimonic wellbeing, and vice versa. People reporting higher levels of self-reported physical activity report a higher sense of purpose in life up to four years later (62) and objectively measured physical activity is associated with higher purpose in life when averaged across three days (63). People who practice health-promoting behaviors report a greater sense of purpose in life (64). Cross-sectional evidence suggests physical activity supports attainment of a higher goal of health or giving direction and meaning to life across years (62,63,65,66). Older adults endorsing a higher level of meaning and purpose in life report better sleep quality (67) and every unit increase in self-reported purpose in life was associated with 16% reduced odds of developing sleep disturbances over four years (68). People with high purpose in life had 24% decreased risk of becoming physically inactive and 33% reduced risk of developing sleep problems across an eight-year follow-up period in a prospective US national sample of adults (69).

Sleep and physical activity may support individuals in reaching a goal of health that supports other life goals and values (70). Whether physical activity is associated with subsequent increases in one’s sense of purpose in life—similar to how physical activity has emotion-brightening effects—is less certain. Experience-sampling studies have observed that physical activity was positively associated with happiness, positive emotions, and purpose in life on the following day (71) and that people endorsed greater life satisfaction on days when they engage in more minutes of overall physical activity (72). Though an important empirical foundation has been established for the effects of physical activity on eudaimonic wellbeing, there is need to concurrently measure sleep, physical activity, emotions, and purpose in life concurrently in everyday life to gain a holistic understanding of the naturalistic dynamics of interactions within this system.

Health behavior and wellbeing as a complex system

There exist potential bidirectional associations between health behaviors and wellbeing in daily life and there is a complex, networked interplay between sleep and physical activity in real life. As reviewed above, health behavior interventions designed to promote wellbeing focus on the effects of physical activity and sleep on wellbeing (30,38,55,60,63,73), but the degree to which we judge our lives to be meaningful and experience happiness also likely impacts the extent to which we get a good night’s sleep (74) and move throughout the day (50,51,72).

Physical activity and sleep, while generally examined independently in the majority of studies reviewed above (51,69,75–78) likely influence one another in daily life. For example, regular physical activity at or above recommended levels mitigates the detrimental effects of poor sleep on wellbeing (79) and a single bout of physical activity increases neuroelectrical indices of relaxation in individuals with anxiety (80). Although a recent review of 33 ecological momentary assessment studies showed no bidirectional association between daily sleep and physical activity (81), findings showed that sleep quality, sleep efficiency, and wake periods after sleep onset were associated with small effects on physical activity the next day (81). Although the majority of reviewed studies used objective device-based measures of physical activity and sleep, the specific devices used varied greatly in outcome measured (e.g., raw acceleration or steps) and validated cut points used for characterizing sleep and physical activity, which could explain the conflicting findings. Greater consideration of the mutual dependencies between physical activity and sleep will provide a more complete account of how physical activity and sleep engender lasting changes on wellbeing in daily life. To push forward our understanding of health behaviors and wellbeing, this complex systems perspective entailing bidirectional associations and dependencies among a web of individual health behaviors (i.e., physical activity and sleep) can be accommodated by coupling intensive repeated measures with network science.

Accommodating a complex systems approach to health behaviors and wellbeing using network science

A network approach has emerged to better understand the dynamic relationships among multiple behaviors and psychological processes in daily life (82–85). For example, poor sleep may result in heightened negative emotions, which in turn may lead to more daytime sleepiness, which in turn may lead to negative emotional states. In contrast, being active may result in increased positive emotions, which in turn may lead to feeling a greater sense of purpose in life, which in turn may lead to reduced negative emotions. Network analysis can be applied to experience-sampling data using vector autoregression (VAR) techniques. These approaches predict autoregressive effects: a variable (i.e., sleep quality) at a certain time point is predicted by the same variable at the previous time point as well as all other variables at the previous time point (83). Network analysis extends standard time series analyses by offering a visual representation of the relations among all assessed variables. The network approach also allows for the estimation and visualization of the co-occurrence of multiple variables simultaneously on lagged (previous day) and contemporaneous (same day) levels, thus it is possible to capture the dynamics among variables of interest while considering multiple timescales. Consistent with efforts to conceptualize observed behavioral and psychological processes (e.g., health and wellbeing) as emergent behavior of complex, dynamic systems in which psychology and behavior affect one another (86,87), we apply this network perspective to consider physical activity, sleep, emotions, and purpose in life as part of a system that reflects wellbeing.

A recent paper modeled networks describing within-person associations among self-reported sleep, physical activity, and diet in adults with obesity who were participating in a weight loss intervention (88). Each behavior was measured at three time points: baseline, 6 months, and 12 months using questions that asked participants to report on each behavior over the past month. These retrospective reports were then used to compute daily measures of average minutes per day of physical activity, average minutes per day of sedentary behavior, average sleep duration, and total consumption of vegetables, fruit, and sugar. When participants reported more sedentary behavior than their usual levels across the three time points, they reported less fruit intake and greater consumption of sugar. However, these longitudinal within-person networks should be interpreted with caution for two reasons. First in addition to being susceptible to recall bias, using cross-sectional, retrospective measures may obscure important trends in health behaviors that vary meaningfully from day to day and even within days. Second, the within-person network variables were computed by subtracting the mean of each participant’s behavior across the three time points from each participant’s scores at each time point, thus estimating each person’s average behavior across 12 months. As such, conclusions from these networks cannot inform our understanding of causal dynamics among behaviors within individuals given that the timescale of dynamics within this system was six-month intervals. To address these limitations, we leveraged the strength of the intensive longitudinal data (up to 28 days within 226 individuals) to reveal the dynamics among physical activity, sleep, and wellbeing in daily life.

The present study

Understanding how physical activity and sleep influence wellbeing in everyday life necessitates approaches that consider how these behaviors fluctuate across days as well as how these behaviors support components of wellbeing in everyday life. The aim of this paper was to leverage the strengths of network analysis to explore the daily temporal relationships among physical activity, sleep, and wellbeing. Just as prior work has shown that there are complex, bidirectional associations among components of our proposed health behavior-wellbeing system, we hypothesize that the network approach will be an appropriate method for describing the daily interactions among physical activity, sleep, and wellbeing.

Method

We use data from the Social Health Impact of Network Effects (SHINE) Study, which was designed to provide insight into health behaviors and social interactions among young adults (more details on the full protocol are available at https://osf.io/gkahy/). The University of Pennsylvania served as the Institutional Review Board of record, following reliance agreements and local context review approvals at Columbia University. This study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board and the Army Research Lab Human Research Protection Office.

Participants

The present study used data from 226 young adult participants (169 women, 56 men, 1 unreported, Meanage = 20.2 years, SDage = 1.7, age range: 18–42) who completed the study from May to October 2020. The racial/ethnic composition of the sample was 42% white, 33.6% Asian, 7.1% Black or African American, 10.2% multiracial, 1.3% other, and 9.3% of participants identified as Hispanic or Latino.

Procedure

Recruitment materials advertised a study titled “Social Health Impact of Network Effects Study (SHINE)” to undergraduate students who were members of on-campus social groups (e.g., sports teams, clubs, sororities and fraternities) at the University of Pennsylvania and Columbia University. See Supplemental Digital Content, Methods (https://osf.io/9g5yv/) for additional information about the larger study. Code is available on OSF (https://osf.io/9g5yv/).

We used the LifeData (https://www.lifedatacorp.com/) company’s RealLife Exp smartphone app for experience sampling. Experience-sampling assessment was deployed between 30 May 2020 and 27 October 2020 in response to the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. For this data collection, all participants contacted initially as part of the larger study and any new members that joined the groups were invited to complete an online survey to understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on a variety of psychosocial factors (see codebook on the Open Science Foundation: https://osf.io/gkahy/). Interested participants provided their consent and completed the COVID survey. At the end of the COVID survey, participants were asked for their interest and consent to partake in a 28-day Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) and Ecological Momentary Intervention (EMI) protocol. This second protocol was similar to the first protocol (see Supplemental Digital Content, Methods), though it contained additional items and was completed entirely online. Interested participants were emailed a Qualtrics survey with instructions on how to set up the EMI and EMA protocol on their phone, and then began the protocol. We focus on the baseline survey measures and COVID-19 experience-sampling period because the COVID-19 survey period included a broad range of wellness variables that are of greatest interest in the current investigation. Participants received $60 Amazon gift card for answering at least 70% of the second experience-sampling period.

Measures

The present study made use of participants’ reports of demographic characteristics from the baseline survey (age, gender, race, and ethnicity) and the experience-sampling data collected on their smartphones in day-to-day life during the COVID-19 pandemic. During the experience-sampling period, a morning survey was sent at 8AM and an evening survey was sent at 6PM. The surveys remained open until the next notification: after the 8AM survey, there was a prompt at 2PM and after the 6PM survey there was a prompt at 9PM as part of the EMI (see Supplemental Digital Content, Methods).

Momentary Physical Activity

Physical activity was measured using a modified version of the Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire (LTEQ; Godin et al., 1986; Godin & Shephard, 1985). The LTEQ is a validated measure of adult physical activity (91). Although typically administered as a previous-week recall measure, the measure has been modified to assess physical activity in situ over a period of hours (92–94), thus reducing potential recall bias and reliance on personal heuristics to estimate physical activity (95,96). During the EMA surveys, participants were asked “Since your MORNING/EVENING survey, how many times did you engage in exercise for more than 10 minutes in (1) vigorous exercise (e.g., running, vigorous swimming), (2) moderate exercise (e.g., fast walking, volleyball), (3) mild exercise (e.g., easy walking, yoga). Using the LTEQ scoring procedure, responses were weighted by standard metabolic equivalents (MET; vigorous = 9; moderate = 5; mild = 3) and summed to create a total momentary MET or energy expenditure score. Higher scores indicate greater physical activity energy expenditure. Consistent with prior EMA work using these questions (92,97), the data are most amenable to transformation into METs than other proposed indices of physical activity (e.g., duration).

Momentary Emotional States

Momentary emotions (happy, sad, anxious, angry) were measured using items from the Profile of Mood States (POMS; 97). The POMS is a validated measure of emotions that has been previously used in experience-sampling studies with adults (99,100).

Happiness.

We measured happiness using one item asking participants to respond on a sliding scale from 1 (“Not at all”) to 100 (“Extremely”) to the following prompt: “Right now, I feel HAPPY”.

Sadness.

We measured sadness using one item asking participants to respond on a sliding scale from 1 (“Not at all”) to 100 (“Extremely”) to the following prompt: “Right now, I feel SAD”.

Anxiety.

We measured anxiousness using one item asking participants to respond on a sliding scale from 1 (“Not at all”) to 100 (“Extremely”) to the following prompt: “Right now, I feel ANXIOUS”.

Anger.

We measured anger using one item asking participants to respond on a sliding scale from 1 (“Not at all”) to 100 (“Extremely”) to the following prompt: “Right now, I feel ANGRY”.

Daily Purpose in Life

We measured purpose in life with an item adapted from Ryff (101). In the morning survey, we measured purpose in life using one item asking participants to respond on a sliding scale from 1 (“Not at all”) to 100 (“Extremely”) to the following prompt: “I feel that I have a sense of direction and purpose in my life”.

Nightly Sleep

We measured sleep using items adapted from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (102) that have been used in previous daily diary studies (103). Typically used as previous-month recall measures, two items were configured for daily assessment as previous-night recalls. These measures are more strongly correlated with actigraphy measures of sleep than retrospective, previous month reports (104).

Sleep duration.

In the morning survey, we measured sleep duration using one item asking participants to answer the following question: “How many hours and minutes of sleep did you get last night (This may be different from # of hours spent in bed)?”. Participants responded based on a hours and minutes number wheel.

Sleep quality.

In the morning survey, we measured sleep quality using one item asking participants to report on a scale from 1 (“Very bad”) to 100 (“Very good”) to the following question: “Last night, how would you rate your quality of sleep?”.

Daily Interactions among Physical Activity, Sleep, and Wellbeing

To accommodate the once per day rating of sleep and purpose in life (in contrast to the other variables, which could be measured more than once per day), we used a multilevel vector autoregressive (mlVAR) model to isolate within- and between-person relationships among multiple variables (83,84; see Supplemental Digital Content). Prior to network estimation, mlVAR transforms the variables by splitting predictors into within and between components, which is relevant for considering the distribution of the ecological momentary assessment variables. Importantly, data are person-mean centered by default, allowing a consideration of within-person associations between variables that are disentangled from between-person differences (105). This approach generates three networks describing the relationships among variables of interest (day’s physical activity, sleep, happiness, sadness, anger, anxiousness, and purpose in life): 1) a directed temporal network revealing within-person time-lagged (previous day) relationships among variables, 2) an undirected network revealing within-person same-day (contemporaneous) relationships among variables, and 3) an undirected between-person network identifying variables that fluctuate at the between-person level (see Supplemental Digital Content, Results and Figure S2 for the between-person network as the focus of this manuscript was on the within-person associations). We computed daily values of physical activity, emotions, and purpose in life by calculating the mean values of physical activity, emotions, and purpose in life across the two reports for each day to be used in these models. Eight multilevel models are sequentially estimated (one for each variable of interest). In this step, each variable (i.e., physical activity, sleep quality, sleep duration, happy, sad, anxiety, angry, purpose in life all assessed at the daily level) at time t is predicted by the 8 within-participants lagged (t-1) variables and the 7 trait-level predictors (the mean of the predicted variable is not included).

Network Estimation

The three networks that comprise the mlVAR model are estimated in two steps. First, the temporal and between-participants models are estimated. Eight multilevel models are sequentially estimated (one for each variable of interest). In this step, each variable (i.e., physical activity, sleep quality, sleep duration, happy, sad, anxiety, angry, purpose in life all assessed at the daily level) at time t is predicted by the 8 within-participants lagged (t-1) variables and the 7 trait-level predictors (the mean of the predicted variable is not included). Along with the fixed effects, random subject intercepts are also included. Equation 1 below, predicting happy affect at time t, depicts how coefficients are obtained for the temporal and between-participants networks. Estimates b1-b8 represent the time-lagged variables (resulting in 8 edges for the temporal network) and b9-b15 represent the trait-level estimates (denoted by ), resulting in 7 estimates for the between-participants network. b0 represents the intercept and (1|ID) denotes the random participant intercepts. A model similar to this one is fit for each of the other seven variables resulting in the 64 estimates for the temporal network and for the 28 between-participants network.

| (1) |

Next, the contemporaneous network is estimated by leveraging the residuals from each of the eight models run in the previous step. Eight multilevel models are fit where the residuals of a given variable are predicted by the residuals from the other seven variables. Equation 2 below (with r_ denoting that these are residuals from prior estimate models in equation 1) predicting the time t happy residuals is presented to help illustrate this procedure. b1 to b7 represent the coefficients that contribute to the contemporaneous network. The remaining components represent orthogonal random slopes for each predictor variable. A similar model is fit for the other seven variables resulting in 28 estimates that comprise the contemporaneous network.

| (2) |

An assumption of mlVAR is that the data are stationary; that is, the mean and variance of a given time series should remain unaltered over time. Thus, we ran a Kwiatkowski-Phillips-Schmidt-Shin (KPSS) test on every participant’s time series for each variable using the tseries package in R (106). Across participants and variables, the data were stationary (p’s ≥ 0.10).

We then computed centrality measures to examine the importance of nodes within temporal (strength, in-degree, out-degree) and contemporaneous (strength, degree) networks. Strength is computed as the sum of the absolute edge values connected to a given node and thus represents the direct influence a node has on a network. Directed networks have two degrees: in-degree representing the number of incoming edges and out-degree representing the number of outgoing edges emanating from a node. In undirected networks, degree represents the number of edges incident on it. Degree informs us how connected a node is within the network.

Robustness checks.

Because physical activity and emotions were measured twice per day, we include additional analyses examining within-day bidirectional associations that may be of interest to readers but outside the scope of this study (see Supplemental Digital Content, Methods and Results; Figure S1). We ran additional conservative analyses with inclusion of the lagged physical activity (t −1) and lagged emotion dependent variable (t −1) in the models and include these results in the Supplemental Digital Content. Although we do not focus on intervention effects in this manuscript, the presented associations were observed when controlling for potential intervention effects. Results were similar when considering the non-intervention sample alone (n = 76). We retain the full sample to ensure high statistical power and because the intervention did not specifically target any of the study variables (107). We refer readers to the supplemental material for a detailed discussion of these supplemental analyses (see Supplemental Digital Content, Figures S3–S4) and a brief overview of the study intervention, and to Jovanova et al. (107) for a detailed discussion of the design and testing of the intervention component that specifically targeted alcohol use.

Results

Out of 12,656 prompts possible (2 prompts per day × 28 days × 226 participants), participants completed 9838 (77.7%) physical activity reports; 10,373 angry reports (82%), 10,388 anxious reports (82.1%); 10,397 happy reports (82.2%); and 10,396 sad reports (82.1%). Out of 6328 prompts possible (1 prompt per day × 28 days × 226 participants), participants completed 5121 sleep duration reports (80.9%) and 5137 sleep quality reports (81.2%) and 5206 purpose in life reports (82.3%). Participants completed an average of 49.3 prompts of up to 56 prompts (SD = 12.6) and reported being physically active on 40.9% of these reports. We provide descriptions of (and correlations among) key study variables in SDC, Table S1.

Daily Interactions among Physical Activity, Sleep, and Wellbeing

Temporal Network

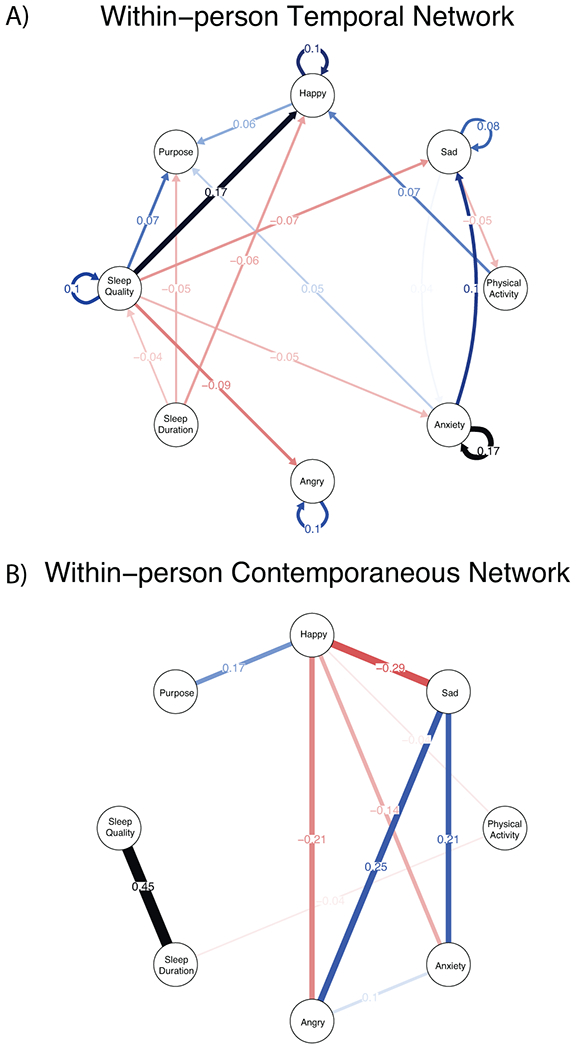

Results from the within-participants temporal network are depicted in Figure 1A. We found the following significant temporal relationships with physical activity: when physical activity was higher than usual on a given day, happiness was higher than usual the next day (b = 0.07, p =0.005). We found the following significant temporal relationships with sleep quality: higher than usual sleep quality on a given night predicted higher next-day purpose in life (b = 0.07, p < 0.001) and happiness (b = 0.17, p < 0.001) as well as lower sadness (b = −0.07, p < 0.001), anxiety (b = −0.05, p < 0.001), and anger (b = −0.09, p < 0.001) the next day. We found the following significant temporal associations with sleep duration: longer than usual sleep duration on a given night predicted lower than usual sleep quality (b = −0.04, p = 0.049), purpose in life (b = −0.05, p < 0.001), and happiness (b = −0.06, p < 0.001) the next day. We found the following significant temporal associations with emotions: when sadness was higher than usual on a given day, physical activity was lower than usual (b = −0.05, p = 0.013) and anxiety was higher than usual (b = 0.04, p = 0.034) the next day; when happiness was higher than usual on a given day, purpose in life was higher than usual the next day (b = 0.06, p = 0.002); when anxiety was higher than usual yesterday, sadness (b = 0.10, p < 0.001) and purpose in life (b = 0.05, p = 0.029) were higher than usual the next day.

Figure 1.

Withing-person temporal (A) and contemporaneous (B) networks. Solid blue/dark blue edges represent positive associations whereas solid red edges represent negative associations. The thickness and shade of the edge represents the strength of the association. In panel A, arrows represent the direction of the effect (i.e., variable yesterday predicting a variable today) and edges represent partial β-coefficients. In Panel B, edges represent partial correlations. All shown edges are statistically significant p < 0.05. Color image is available online only at the Psychosomatic Medicine website.

Contemporaneous Network

Results from the within-participants contemporaneous network are depicted in Figure 1B. We found the following significant relationships for a given day: on days when people experienced higher than usual happiness, sadness (rp = −0.29), anxiousness (rp = −0.14) and anger (rp = −0.21) were lower than usual. On days when physical activity was higher than usual, sleep duration on the same night was shorter (rp = −0.04) and happiness was lower (rp = −0.04) on the same day. Longer sleep duration than usual was associated with higher sleep quality (rp = 0.45) on the same evening. Higher happiness than usual was associated with higher purpose in life (rp = 0.17). The negative emotional states were positively associated (rp’s ≥ 0.10).

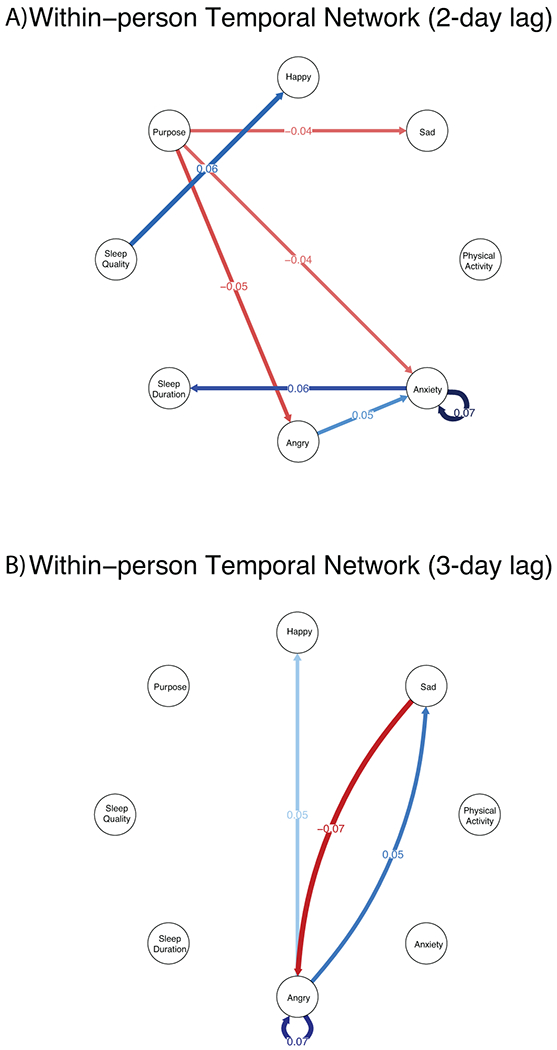

Length of Temporal Effects

Given that physical activity on a given day corresponds with higher happiness the next day and sleep is associated with lower negative emotions the following day, a natural question is how long this temporal relationship persists. Prior work has shown that there are carryover effects in emotions in daily life (100,108) and recent work has suggested that physical activity may interrupt this emotional inertia (109). In exploratory analyses, we next assessed the temporal network with a time lag of two days (rather than one day; see Figure 2A). Physical activity two days prior did not predict happiness (b = 0.001, p = 0.96). Likewise, sleep quality did not predict negative emotions at a lag of two days (b’s ≤ −0.03, p’s ≥ 0.05). However, sleep quality predicted higher happiness at a lag of two days (b = 0.07, p = 0.001). Similarly, purpose in life predicted lower sadness (b = −0.04, p = 0.032), anxiousness (b = −0.04, p = 0.024), and anger (b = −0.05, p = 0.017) at a lag of two days. Anxiety’s positive autocorrelation was significant at the two-day lag (b = 0.07, p = 0.002) and anxiety predicted longer sleep duration at a lag of two days (b = 0.06, p = 0.046). Anger predicted higher anxiety at a lag of two days (b = 0.05, p = 0.006). At a lag of three days, sleep and physical activity were not predictive of any behaviors, yet there were associations between anger with happiness (b = 0.05, p = 0.037) and sadness (b = 0.05, p = 0.024) and between sadness and anger (b = −0.07, p = 0.012; see Figure 2B). Collectively, these findings suggest that while the effects of physical activity on emotions and purpose in life may be shorter term (e.g., one day), a sense of purpose in life and negative emotional states can be slightly longer lasting, bleeding into the next few days.

Figure 2.

Within-person temporal lag of 2 days (A) and temporal lag of 3 days (B) networks. Solid blue/dark blue edges represent positive associations whereas solid red edges represent negative associations. The thickness and shade of the edge represents the strength of the association. Arrows represent the direction of the effect (i.e., variable n days prior predicting a variable today) and edges represent partial β-coefficients. Color image is available online only at the Psychosomatic Medicine website.

Centrality Measures

We present centrality measures for temporal and contemporaneous networks in Table 1. In the temporal network, the nodes with the highest strength are sadness, anxiety, and happiness; the highest in-degree are happiness, purpose in life, and sadness; the highest out-degree are anxiety, physical activity, and sadness. In the contemporaneous network, the nodes with the highest strength are purpose in life, anxiety, and anger; the nodes with the highest degree are happiness, sadness, and anger.

Table 1.

Node centrality measures for within-person temporal and contemporaneous networks.

| Node | Strength | In-degree | Out-degree |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Temporal Network

|

|||

| Happiness | 1.53 | 0.16 | 0.07 |

| Anxiety | 1.83 | 0.04 | 0.14 |

| Anger | 0.96 | 0 | 0 |

| Sadness | 2.23 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| Purpose in life | 1.64 | 0.12 | 0 |

| Sleep duration | 0 | 0 | 0.03 |

| Sleep quality | 0 | 0 | 0.04 |

| Physical activity | 1.33 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| Contemporaneous Network |

Strength |

Degree |

|

| Happiness | 2.41 | 0.87 | |

| Anxiety | 3.17 | 0.50 | |

| Anger | 3.09 | 0.57 | |

| Sadness | 2.85 | 0.76 | |

| Purpose in life | 3.38 | 0.17 | |

| Sleep duration | 1.33 | 0.52 | |

| Sleep quality | 0.93 | 0.54 | |

| Physical activity | 2.57 | 0.13 |

Note: Strength represents the sum of the absolute weights to/from a node. In the temporal (directed) network, the in-degree is the number of incoming edges to a node, and out-degree is the number of outgoing edges emanating from a node. In the contemporaneous (undirected) network, the degree represents the number of edges connected to a node. The top three values for each measure are highlighted in grey. A total of 5495 anxiety, 5498 happiness, 5492 anger, 5500 sadness, 5206 purpose in life, 5121 sleep duration, 5137 sleep quality, and 5340 physical activity daily reports nested within 210 participants.

Discussion

Sleep, physical activity, emotions, and purpose in life are parts of a health behavior wellbeing system. The extent to which components of this system interact and mutually influence one another during everyday life is not clear, due in part to the challenge of concurrently measuring these states and behaviors and due to the complex, mutual dependencies that exist within this system. We capitalized on smartphone experience-sampling approaches across one month and network analyses to reveal the pairwise interplay and to simultaneously estimate associations among components of the health behavior wellbeing system in a naturalistic real-world setting.

In the within-person temporal network, which shows how sleep, physical activity, purpose in life, and emotions relate to one another from one day to the next, we observed that higher than usual sleep quality is associated with decreased negative emotional states (sad, angry, anxiety) the next day. Longer sleep duration yesterday was associated with decreased purpose in life and reduced happiness the next day, which is consistent with prior work at the between-person level suggesting that longer sleep duration (≥ 10h ) is associated with increased depressive symptoms that overlap with the current operationalization of purpose in life, e.g., “little interest or pleasure in doing things” (110). Collectively, findings are consistent with work demonstrating that sleep is a crucial health behavior supporting wellbeing in daily life (55,67,111–113) but extends it by examining the influence of sleep characteristics on both emotional and eudaimonic components of wellbeing across a month at the within-person level.

The within-person temporal network also offered insight into associations between the physical activity and emotional aspects of wellbeing. We observed that higher than usual physical activity yesterday predicted increased happiness the next day, but these effects disappeared in the two- and three-day temporal networks. This finding is consistent with laboratory studies showing that a single bout of physical activity enhances positive emotions up to one day following the experimental session (30). We extend prior experience-sampling work (41–45,47) by examining the effects of physical activity on emotions up to 3 days later. This finding is further supported by interpreting it alongside the contemporaneous network showing that increased physical activity is associated with decreased happiness on the same day, suggesting that there is a temporal precedence for the physical activity-emotions association: people need to engage in physical activity before experiencing enhanced positive emotions. Our findings show people must engage in physical activity regularly to accrue the emotion-brightening effects of physical activity in everyday life because these effects are relatively short lived.

Findings from the within-person temporal network highlight sadness as a particularly potent negative emotional state influencing next-day physical activity. This is consistent with prior experience-sampling work demonstrating that heightened negative emotions immediately reduces subsequent physical activity (114). We show that this relationship persists up to one day. Consistent with network perspectives of emotions suggesting that psychopathology results from the causal interplay between symptoms (85,115,116), we find that there is a positive interplay among sadness, anger, and anxiousness within the same day, such that these negative emotional states perpetuate one another. Consistent with these perspectives, we find sadness has a persistent influence on physical activity. In this way, negative emotions may subsequently reduce the likelihood of being physically active, which is a potent moderator of positive emotions. Thus, it is plausible that engaging in physical activity may briefly interrupt the interplay among negative emotional states suggesting its utility in the management of negative emotional states.

With respect to purpose in life as an indicator of eudaimonic wellbeing, our daily network models show that on days when purpose in life is higher than usual, happiness is also higher than usual. This positive association is consistent with prior work demonstrating that purpose in life supports psychological wellbeing and is related with positive emotions (117–119) but extends it by showing this association holds on a daily timescale. In this way, purpose in life is a renewable resource that physical activity can serve to enhance, thus bolstering wellbeing by supporting attainment of the greater goal of health or by simply engaging in enjoyable meaningful daily activities (63,120,121). Our findings did not support a bidirectional association between purpose in life and physical activity from one day to the next. Although prior work has shown a bidirectional association between physical activity and purpose in life, our findings may differ because these studies have used objective measures of physical activity. However, by using self-reported physical activity periods, it is possible that our participants were able to move beyond experimenter-defined notions of physical activity or exercise with the goal of improving fitness. We also find that negative emotional states, such as anxiety, are associated with greater purpose in life the next day. Although our data cannot directly explain this association, one possibility is that anxiety may drive individuals to seek out opportunities to engage in meaningful activities. This finding aligns with the notion that all emotions, especially high-arousal emotions (e.g., anger and anxiety) are associated with motivational action (122) and can motivate people to take control of a situation and change behavior (123).

Although the two-day and three-day lag networks were exploratory in nature, purpose in life appears to be particularly salient for reducing negative emotions up to two days later. It is possible that a boost in daily meaning has an enduring impact on emotional health persisting beyond the activity bout—bleeding into the next few days. This finding has practical implications. Substantial public health efforts have highlighted physical activity as a means of enhancing population physical and mental health (124). However, efforts to disseminate these guidelines have focused on communicating the duration, frequency, and type of physical activity to receive optimal health benefits. Such an approach overlooks a critical component of the health behavior-wellbeing system: finding meaning or purpose in daily activities. Aristotle (125) first proposed that human behavior is likely better understood within the lens of phronesis or practical reasoning that aims to realize valued goals. This perspective is in contrast to the robust body of literature seeking to determine the antecedents and determinants of physical activity (126–129). Our findings highlight that the pathway from physical activity → purpose in life → emotions may play a critical role in supporting everyday wellbeing and ought to be considered when translating physical activity guidelines to the general population. For instance, helping people identify daily physical activities that support their values and meaning-making and finding ways to help them understand how frequently to engage in these behaviors to support their health and wellbeing.

Our findings provide evidence of the feasibility and utility of viewing physical activity, sleep, emotions, and purpose in life as part of a system reflecting wellness in daily life. In particular, the centrality metrics we calculated reflect the structural importance of a given node (i.e., strength) and assign importance to the node based on the number of links held (i.e., in-degree and out-degree) within our health behavior-wellbeing system (130). Consistent with dual-processing, self-regulation, and self-determination theories of health behaviors, our centrality findings highlight emotions as central to engaging in health behaviors to support wellbeing (131–134). We found that the nodes with the highest strength were sadness, anxiety, and happiness in the temporal network and purpose in life, anxiety, and anger in the contemporaneous network. Interventions aiming to influence the dynamics within our health behavior-wellbeing system may be most effective by targeting positive and negative emotions and purpose in life to have immediate (same-day) and carryover (next-day) effects on wellbeing. Moreover, purpose in life has been found to act as a buffer helping to recover from negative emotions (135). Alongside the finding that happiness, purpose in life, and sadness have the most incoming links within the temporal network, it is likely that these nodes are most susceptible to perturbations in other nodes (e.g., sleep and physical activity) from day to day. Given that anxiety, physical activity, and sadness have the highest number of outgoing links within the temporal network, targeting these nodes may be most effective for influencing wellbeing from one day to the next within our system. In the contemporaneous network, happiness, sadness, and anger are most connected. This finding is perhaps unsurprising given prior work that shows high-arousal emotions motivate people into action, which can incite behavior change (123).

Health communication efforts highlight values affirmation as a critical component of health messaging and behavior change in daily life (136,137). Future work that examines activity-promoting interventions incorporating aspects of self-affirmation and purpose in life combined with mobile sensing will help reveal whether, how, and the temporal nature by which these interventions influence components of the health behavior-wellbeing system in daily life. Commercially available wearables already deploy nudges that incorporate self-affirmation messages to influence behavior; however, to what extent an activity-promoting intervention can be personalized to align with one’s purpose and values may be more fruitful for influencing behavior in the moment. Future work may seek to understand how personalized movement interventions can have a downstream impact on sustainable behavior change in peoples’ daily lives compared to movement interventions that do not target self-affirmation.

Days of higher than usual physical activity were associated with shorter than usual sleep duration that night. These findings are in line with observations that physical activity and sleep represent two ends of a continuum in which prioritizing one behavior (e.g., physical activity) may occur at the expense of the other (e.g., sleep) due to time constraints (138). Although cross-sectional evidence suggests increased physical activity benefits sleep quality and duration (139), our findings highlight the need for examining how these relationships unfold in the course of daily life. Prior experience-sampling work has found equivocal findings for the association between physical activity and sleep, with some finding people sleep longer on days following higher than usual physical activity (140) and others finding no association between sleep duration and physical activity (141,142). In daily life, however, physical activity and sleep compete for time: Being physically active may come at the expense of time to sleep when juggling all the responsibilities of daily life (143). People who exercise regularly sleep on average 15.5 minutes less than those who do not exercise (143), and our findings extend this work to the within-person level suggesting that on days when people engage in more physical activity than usual it may occur at the expense of sleep duration that night. Alternatively, the observed longer sleep duration may be indicative of persistent negative emotions during the COVID-19 pandemic, which is often associated with sleep disturbances (144).

Limitations

Despite the strength of the naturalistic reports of sleep, physical activity, emotions, and purpose in life across one month in the present investigation, there are limitations that warrant further discussion. The sample is primarily white, college-aged adults identifying as women, making generalizations to other samples difficult. The self-report measures of sleep and physical activity were retrospective in nature (reporting on the previous timepoint’s behavior). This approach allowed us to capture behaviors occurring after the evening survey (6:00pm) but may have introduced retrospective biases. An interval-contingent EMA protocol was used whereby participants responded at the same time every day. This approach likely supported the high response rate (77.1%), but may have led participants to anticipate the assessments in a way that may be mitigated by signal-contingent or variable time-based approaches. Interesting directions for future research would be to build upon the present work by addressing additional components of wellbeing (e.g., life satisfaction and self-esteem), examining clustering with other health behaviors (e.g., substance use), and delineating associations within the health behavior-wellbeing system with finer granularity of data (e.g., minutes or hours).

Conclusions

In summary, we helped bridge the gap between laboratory studies and experience-sampling work regarding the roles of physical activity, sleep, emotions, and purpose in life on everyday wellbeing. We examined associations among physical activity, sleep, emotions, and purpose in life as components within a health behavior wellbeing system that reflect wellness in daily life and found that physical activity predicted increased happiness the next day and better sleep quality predicted reduced negative emotions the next day. We found that purpose in life predicted decreased sadness, anxiousness, and anger up to two days later. Our results lay the groundwork for creating naturalistic, mobile-sensing based human models to further elucidate the interplay among real-world health behaviors and wellbeing. Future work, which may be particularly important, can test how changes in some sets of nodes within this complex system propagate to influence other nodes within the system, useful for testing the feasibility of interventions and informing the design of ecologically-relevant health-enhancing wellness programs. Such interventions will likely be most successful by taking a person-specific approach, which will necessitate collecting substantially more intensive time series data for each participant (145,146).

Supplementary Material

Conflicts of Interest and Sources of Funding

Research was sponsored by the Army Research Office and was accomplished under Grant Number W911NF-18-1-0244. D.M.L. and A.L.M. acknowledge support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K01 DA047417) and the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation. D.S.B. acknowledges support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Swartz Foundation, the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the NSF (PHY-1554488; IIS-1926757), and National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH113550). The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the Army Research Office or the U.S. Government. The U.S. Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Government purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation herein.

List of abbreviations

- EMA

Ecological Momentary Assessment

- EMI

Ecological Momentary Intervention

- LTEQ

Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire

- MET

Metabolic Equivalents

- mlVAR

Multilevel Vector Autoregressive model

- OSF

Open Science Framework

- POMS

Profile of Mood States

- SHINE

Social Health Impact of Network Effects Study

- VAR

Vector Autoregression

Footnotes

Previous Posting: This manuscript was posted as a preprint on PsyArXiv.com on April 26, 2022. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/q4jn3

Author Disclosure Statement

No conflicting financial interests exist.

Citation Diversity Statement

Recent work in several fields of science has identified a bias in citation practices such that papers from women and other minority scholars are under-cited relative to the number of such papers in the field (1–9). Here we sought to proactively consider choosing references that reflect the diversity of the field in thought, form of contribution, gender, race, ethnicity, and other factors. First, we obtained the predicted gender of the first and last author of each reference by using databases that store the probability of a first name being carried by a woman (5,10). By this measure (and excluding self-citations to the first and last authors of our current paper), our references contain 14.79% woman(first)/woman(last), 17.17% man/woman, 28.9% woman/man, and 39.14% man/man. This method is limited in that a) names, pronouns, and social media profiles used to construct the databases may not, in every case, be indicative of gender identity and b) it cannot account for intersex, non-binary, or transgender people. We look forward to future work that could help us to better understand how to support equitable practices in science.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Amanda L. McGowan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization, Project Administration. Zachary M. Boyd: Validation, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing. Yoona Kang: Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing, Project Administration. Logan Bennett: Writing—Review & Editing. Peter J. Mucha: Resources, Writing—Review & Editing, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition. Kevin N. Ochsner: Resources, Writing—Review & Editing, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition. Dani S. Bassett: Resources, Writing—Review & Editing, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition. Emily B. Falk: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition. David M. Lydon-Staley: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Resources, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition.

References

- 1.Bertolero MA, Dworkin JD, David SU, Lloreda CL, Srivastava P, Stiso J, et al. Racial and ethnic imbalance in neuroscience reference lists and intersections with gender. bioRxiv. 2020; [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caplar N, Tacchella S, Birrer S. Quantitative evaluation of gender bias in astronomical publications from citation counts. Nature Astronomy. 2017;1(6):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chakravartty P, Kuo R, Grubbs V, McIlwain C. # CommunicationSoWhite. Journal of Communication. 2018;68(2):254–66. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dion ML, Sumner JL, Mitchell SM. Gendered citation patterns across political science and social science methodology fields. Political Analysis. 2018;26(3):312–27. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dworkin JD, Linn KA, Teich EG, Zurn P, Shinohara RT, Bassett DS. The extent and drivers of gender imbalance in neuroscience reference lists. Nat Neurosci. 2020. Aug;23(8):918–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fulvio JM, Akinnola I, Postle BR. Gender (im) balance in citation practices in cognitive neuroscience. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2020;1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maliniak D, Powers R, Walter BF. The gender citation gap in international relations. International Organization. 2013;67(4):889–922. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell SM, Lange S, Brus H. Gendered citation patterns in international relations journals. International Studies Perspectives. 2013;14(4):485–92. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X, Dworkin JD, Zhou D, Stiso J, Falk EB, Bassett DS, et al. Gendered citation practices in the field of communication. Annals of the International Communication Association. 2021. Apr 3;45(2):134–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou D, Cornblath EJ, Stiso J, Teich EG, Dworkin JD, Blevins AS, et al. Gender Diversity Statement and Code Notebook v1.0. Zenodo; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan RM, Deci EL. ON HAPPINESS AND HUMAN POTENTIALS: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001. Jan 1;141–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwarz N. Well-being: Foundations of hedonic psychology. Russell Sage Foundation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waterman AS. Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1993;64(4):678. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diener E, Napa-Scollon CK, Oishi S, Dzokoto V, Suh EM. Positivity and the construction of life satisfaction judgments: Global happiness is not the sum of its parts. Journal of happiness studies. 2000;1(2):159–76. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diener E, Oishi S. Money and happiness: Income and subjective well-being across nations. Culture and subjective well-being. 2000;185–218. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diener E, Biswas-Diener R. Well-being interventions to improve societies. Global Happiness Council, Global Happiness and Well-being Policy Report. 2019;95–110. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stone BM, Parks AC. Cultivating subjective well-being through positive psychological interventions. Handbook of well-being DEF Publishers; DOI: nobascholar.com. 2018; [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Agteren J, Iasiello M, Lo L, Bartholomaeus J, Kopsaftis Z, Carey M, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological interventions to improve mental wellbeing. Nature Human Behaviour. 2021;5(5):631–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2018 Physical activity guidelines advisory committee scientific report. Washington, DC; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wickham SR, Amarasekara NA, Bartonicek A, Conner TS. The Big Three Health Behaviors and Mental Health and Well-Being Among Young Adults: A Cross-Sectional Investigation of Sleep, Exercise, and Diet. Frontiers in Psychology [Internet]. 2020. [cited 2022 Jun 10];11. Available from: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.579205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. Guidelines on physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep for children under 5 years of age [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2019. [cited 2020 Sep 2]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/311664 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ross R, Chaput JP, Giangregorio LM, Janssen I, Saunders TJ, Kho ME, et al. Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Adults aged 18-64 years and Adults aged 65 years or older: an integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2020. Oct;45(10 (Suppl. 2)):S57–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bharadva K, Shastri D, Gaonkar N, Thakre R, Mondkar J, Nanavati R, et al. Consensus Statement of Indian Academy of Pediatrics on Early Childhood Development. Indian Pediatr. 2020. Sep 1;57(9):834–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroshus E, Wagner J, Wyrick D, Athey A, Bell L, Benjamin HJ, et al. Wake up call for collegiate athlete sleep: narrative review and consensus recommendations from the NCAA Interassociation Task Force on Sleep and Wellness. British journal of sports medicine. 2019;53(12):731–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reardon CL, Hainline B, Aron CM, Baron D, Baum AL, Bindra A, et al. Mental health in elite athletes: International Olympic Committee consensus statement (2019). Br J Sports Med. 2019. Jun 1;53(11):667–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rhodes RE, Guerrero MD, Vanderloo LM, Barbeau K, Birken CS, Chaput JP, et al. Development of a consensus statement on the role of the family in the physical activity, sedentary, and sleep behaviours of children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020. Jun 16;17(1):74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canadian Psychological Association. Psychology works fact sheet: Physical activity, mental health, and motivation [Internet]. 2016. [cited 2022 Jun 10]. Available from: https://cpa.ca/docs/File/Publications/FactSheets/PsychologyWorksFactSheet_PhysicalActivity_MentalHealth_Motivation.pdf

- 28.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Physical Activity - Healthy People 2030 | health.gov [Internet]. [cited 2021 Sep 23]. Available from: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/physical-activity

- 29.Bartholomew JB, Morrison D, Ciccolo JT. Effects of acute exercise on mood and well-being in patients with major depressive disorder. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2005;37(12):2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basso JC, Suzuki WA. The Effects of Acute Exercise on Mood, Cognition, Neurophysiology, and Neurochemical Pathways: A Review. Brain Plast. 2017;2(2):127–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ekkekakis P, Petruzzello SJ. Acute aerobic exercise and affect. Sports Med. 1999. Nov 1;28(5):337–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeung RR. The acute effects of exercise on mood state. Journal of psychosomatic research. 1996;40(2):123–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franzen PL, Siegle GJ, Buysse DJ. Relationships between affect, vigilance, and sleepiness following sleep deprivation. Journal of Sleep Research. 2008;17(1):34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mata J, Thompson RJ, Jaeggi SM, Buschkuehl M, Jonides J, Gotlib IH. Walk on the bright side: Physical activity and affect in major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121(2):297–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vandekerckhove M, Weiss R, Schotte C, Exadaktylos V, Haex B, Verbraecken J, et al. The role of presleep negative emotion in sleep physiology. Psychophysiology. 2011;48(12):1738–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Talamini LM, Bringmann LF, Boer M de, Hofman WF. Sleeping Worries Away or Worrying Away Sleep? Physiological Evidence on Sleep-Emotion Interactions. PLOS ONE. 2013. May 1;8(5):e62480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchell G. Revisiting truth or triviality: The external validity of research in the psychological laboratory. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2012;7(2):109–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liao Y, Shonkoff ET, Dunton GF. The Acute Relationships Between Affect, Physical Feeling States, and Physical Activity in Daily Life: A Review of Current Evidence. Frontiers in Psychology. 2015;6:1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Larson R, Csikszentmihalyi M. The experience sampling method. In: Flow and the foundations of positive psychology. Springer; 2014. p. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:1–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carels RA, Coit C, Young K, Berger B. Exercise Makes You Feel Good, But Does Feeling Good Make You Exercise?: An Examination of Obese Dieters. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 2007. Dec 1;29(6):706–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gauvin L, Rejeski WJ, Norris JL. A naturalistic study of the impact of acute physical activity on feeling states and affect in women. Health Psychology. 1996;15(5):391–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guérin E, Fortier MS, Sweet SN. An Experience Sampling Study of Physical Activity and Positive Affect: Investigating the Role of Situational Motivation and Perceived Intensity Across Time. Health Psychol Res. 2013. Jun 13;1(2):e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.LePage ML, Crowther JH. The effects of exercise on body satisfaction and affect. Body Image. 2010. Mar 1;7(2):124–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Do B, Wang SD, Courtney JB, Dunton GF. Examining the day-level impact of physical activity on affect during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: An ecological momentary assessment study. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2021. Sep 1;56:102010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kanning M, Ebner-Priemer U, Schlicht W. Using activity triggered e-diaries to reveal the associations between physical activity and affective states in older adult’s daily living. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2015. Sep 17;12(1):111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim J, Conroy DE, Smyth JM. Bidirectional associations of momentary affect with physical activity and sedentary behaviors in working adults. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2020;54(4):268–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Von Haaren B, Loeffler S, Haertel S, Anastasopoulou P, Stumpp J, Hey S, et al. Characteristics of the Activity-Affect Association in Inactive People: An Ambulatory Assessment Study in Daily Life. Frontiers in Psychology. 2013;4:163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hevel DJ, Dunton GF, Maher JP. Acute Bidirectional Relations Between Affect, Physical Feeling States, and Activity-Related Behaviors Among Older Adults: An Ecological Momentary Assessment Study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2021. Jan 1;55(1):41–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wichers M, Peeters F, Rutten BPF, Jacobs N, Derom C, Thiery E, et al. A time-lagged momentary assessment study on daily life physical activity and affect. Health Psychology. 2012;31(2):135–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dunton GF, Atienza AA, Castro CM, King AC. Using Ecological Momentary Assessment to Examine Antecedents and Correlates of Physical Activity Bouts in Adults Age 50+ Years: A Pilot Study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2009. Dec 1;38(3):249–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schwerdtfeger A, Eberhardt R, Chmitorz A, Schaller E. Momentary Affect Predicts Bodily Movement in Daily Life: An Ambulatory Monitoring Study. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 2010. Oct 1;32(5):674–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Wild-Hartmann JA, Wichers M, van Bemmel AL, Derom C, Thiery E, Jacobs N, et al. Day-to-day associations between subjective sleep and affect in regard to future depression in a female population-based sample. Br J Psychiatry. 2013. Jun;202:407–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sonnentag S, Binnewies C, Mojza EJ. “Did you have a nice evening?” A day-level study on recovery experiences, sleep, and affect. J Appl Psychol. 2008. May;93(3):674–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wrzus C, Wagner GG, Riediger M. Feeling good when sleeping in? Day-to-day associations between sleep duration and affective well-being differ from youth to old age. Emotion. 2014. Jun;14(3):624–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kalmbach DA, Pillai V, Roth T, Drake CL. The interplay between daily affect and sleep: a 2-week study of young women. Journal of Sleep Research. 2014;23(6):636–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mccrae CS, McNAMARA JPH, Rowe MA, Dzierzewski JM, Dirk J, Marsiske M, et al. Sleep and affect in older adults: using multilevel modeling to examine daily associations. Journal of Sleep Research. 2008;17(1):42–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Totterdell P, Reynolds S, Parkinson B, Briner RB. Associations of sleep with everyday mood, minor symptoms and social interaction experience. Sleep. 1994. Aug;17(5):466–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van der Helm E, Walker MP. Overnight Therapy? The Role of Sleep in Emotional Brain Processing. Psychol Bull. 2009. Sep;135(5):731–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kahn M, Sheppes G, Sadeh A. Sleep and emotions: Bidirectional links and underlying mechanisms. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2013. Aug 1;89(2):218–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ruggeri K, Garcia-Garzon E, Maguire Á, Matz S, Huppert FA. Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: a multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2020. Jun 19;18(1):192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yemiscigil A, Vlaev I. The bidirectional relationship between sense of purpose in life and physical activity: a longitudinal study. J Behav Med. 2021. Oct 1;44(5):715–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hooker SA, Masters KS. Purpose in life is associated with physical activity measured by accelerometer. Journal of Health Psychology. 2016;21(6):962–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ryff CD, Singer B. The contours of positive human health. Psychological inquiry. 1998;9(1):1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sutin AR, Luchetti M, Stephan Y, Terracciano A. Sense of purpose in life and motivation, barriers, and engagement in physical activity and sedentary behavior: Test of a mediational model. J Health Psychol. 2021. May 27;13591053211021660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang Z, Chen W. Longitudinal Associations Between Physical Activity and Purpose in Life Among Older Adults: A Cross-Lagged Panel Analysis. Journal of Aging and Health. 2021;08982643211019508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Turner AD, Smith CE, Ong JC. Is purpose in life associated with less sleep disturbance in older adults? Sleep Science and Practice. 2017. Jul 10;1(1):14. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim ES, Hershner SD, Strecher VJ. Purpose in life and incidence of sleep disturbances. Journal of behavioral medicine. 2015;38(3):590–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim ES, Shiba K, Boehm JK, Kubzansky LD. Sense of purpose in life and five health behaviors in older adults. Preventive Medicine. 2020. Oct 1;139:106172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Scheier MF, Wrosch C, Baum A, Cohen S, Martire LM, Matthews KA, et al. The life engagement test: Assessing purpose in life. Journal of behavioral medicine. 2006;29(3):291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee SS, Yu K, Choi E, Choi I. To drink, or to exercise: That is (not) the question! Daily effects of alcohol consumption and exercise on well-being. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being [Internet]. 2021. [cited 2022 Jan 10];n/a(n/a). Available from: 10.1111/aphw.12319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bourke M, Hilland TA, Craike M. Daily Physical Activity and Satisfaction with Life in Adolescents: An Ecological Momentary Assessment Study Exploring Direct Associations and the Mediating Role of Core Affect. J Happiness Stud [Internet]. 2021. Jul 14 [cited 2022 Feb 3]; Available from: 10.1007/s10902-021-00431-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Das SK, Mason ST, Vail TA, Rogers GV, Livingston KA, Whelan JG, et al. Effectiveness of an Energy Management Training Course on Employee Well-Being: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Health Promot. 2019. Jan 1;33(1):118–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Krueger PM, Friedman EM. Sleep duration in the United States: a cross-sectional population-based study. American journal of epidemiology. 2009;169(9):1052–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li W, Yin J, Cai X, Cheng X, Wang Y. Association between sleep duration and quality and depressive symptoms among university students: A cross-sectional study. PloS one. 2020;15(9):e0238811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kanning M, Schlicht W. Be active and become happy: an ecological momentary assessment of physical activity and mood. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 2010;32(2):253–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Triantafillou S, Saeb S, Lattie EG, Mohr DC, Kording KP. Relationship between sleep quality and mood: Ecological momentary assessment study. JMIR Mental Health. 2019;6(3):e12613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Maher CA, Mire E, Harrington DM, Staiano AE, Katzmarzyk PT. The independent and combined associations of physical activity and sedentary behavior with obesity in adults: NHANES 2003-06. Obesity. 2013;21(12):E730–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Huang BH, Duncan MJ, Cistulli PA, Nassar N, Hamer M, Stamatakis E. Sleep and physical activity in relation to all-cause, cardiovascular disease and cancer mortality risk. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2021; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lattari E, Portugal E, Moraes H, Machado S, M Santos T, C Deslandes A. Acute effects of exercise on mood and EEG activity in healthy young subjects: a systematic review. CNS & Neurological Disorders-Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets-CNS & Neurological Disorders). 2014;13(6):972–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Atoui S, Chevance G, Romain AJ, Kingsbury C, Lachance JP, Bernard P. Daily associations between sleep and physical activity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2021;57:101426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Epskamp S, Cramer AOJ, Waldorp LJ, Schmittmann VD, Borsboom D. qgraph: Network Visualizations of Relationships in Psychometric Data. Journal of Statistical Software. 2012. May 24;48(1):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Epskamp S, Waldorp LJ, Mõttus R, Borsboom D. The Gaussian graphical model in cross-sectional and time-series data. Multivariate behavioral research. 2018;53(4):453–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Epskamp S, Deserno MK, Bringmann LF. mlVAR: Multi-level vector autoregression. R package version 0.4. 4. 2019. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fried EI, van Borkulo CD, Cramer AOJ, Boschloo L, Schoevers RA, Borsboom D. Mental disorders as networks of problems: a review of recent insights. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017. Jan 1;52(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Borsboom D, Cramer AOJ, Schmittmann VD, Epskamp S, Waldorp LJ. The Small World of Psychopathology. PLOS ONE. 2011. Nov 17;6(11):e27407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cramer AOJ, Van Der Sluis S, Noordhof A, Wichers M, Geschwind N, Aggen SH, et al. Dimensions of Normal Personality as Networks in Search of Equilibrium: You Can’t like Parties if you Don’t like People. Eur J Pers. 2012. Jul 1;26(4):414–31. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chevance G, Golaszewski NM, Baretta D, Hekler EB, Larsen BA, Patrick K, et al. Modelling multiple health behavior change with network analyses: results from a one-year study conducted among overweight and obese adults. J Behav Med. 2020. Apr 1;43(2):254–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Godin G, Jobin J, Bouillon J. Assessment of leisure time exercise behavior by self-report: a concurrent validity study. Canadian Journal of Public Health= Revue canadienne de sante publique. 1986;77(5):359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Godin G, Shephard J. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1985;10(3):141–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jacobs DR Jr, Ainsworth BE, Hartman TJ, Leon AS. A simultaneous evaluation of 10 commonly used physical activity questionnaires. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 1993;25(1):81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Conroy DE, Ram N, Pincus AL, Coffman DL, Lorek AE, Rebar AL, et al. Daily Physical Activity and Alcohol Use Across the Adult Lifespan. Health Psychol. 2015. Jun;34(6):653–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lydon-Staley DM, Zurn P, Bassett DS. Within-person variability in curiosity during daily life and associations with well-being. Journal of personality. 2020;88(4):625–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Maher JP, Doerksen SE, Elavsky S, Hyde AL, Pincus AL, Ram N, et al. A daily analysis of physical activity and satisfaction with life in emerging adults. Health Psychology. 2013;32(6):647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Matthews CE, Steven CM, George SM, Sampson J, Bowles HR. Improving self-reports of active and sedentary behaviors in large epidemiologic studies. Exercise and sport sciences reviews. 2012;40(3):118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Schwarz N. Retrospective and concurrent self-reports: The rationale for real-time data capture. The science of real-time data capture: Self-reports in health research. 2007;11:26. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Maher JP, Pincus AL, Ram N, Conroy DE. Daily physical activity and life satisfaction across adulthood. Developmental psychology. 2015;51(10):1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Curran SL, Andrykowski MA, Studts JL. Short form of the profile of mood states (POMS-SF): psychometric information. Psychological assessment. 1995;7(1):80. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fosco GM, Lydon-Staley DM. A within-family examination of interparental conflict, cognitive appraisals, and adolescent mood and well-being. Child development. 2019;90(4):e421–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lydon-Staley DM, Xia M, Mak HW, Fosco GM. Adolescent emotion network dynamics in daily life and implications for depression. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 2019;47(4):717–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 19900501;57(6):1069. [Google Scholar]