Abstract

Background

Many of the 700,000 American military personnel deployed to the Persian Gulf region in 1990 and 1991 have since reported health symptoms of unknown etiology. This cluster of symptoms has been labeled Gulf War Illness and include chronic musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, headaches, memory and attention difficulties, gastrointestinal complaints, skin abnormalities, breathing problems, and mood and sleep problems1, 2. There have been few high-quality intervention trials and no strong evidence to support available treatments3. Tai Chi is an ancient Chinese martial art with benefits that include enhancing physical and mental health and improving quality of life for those with chronic conditions.

Proposed Methods

In this randomized controlled trial, GW Veterans are randomly assigned to either Tai Chi or a Wellness control condition, with both remotely delivered intervention groups meeting twice a week for 12 weeks. The primary aim is to examine if Tai Chi is associated with greater improvements in GWI symptoms in Veterans with GWI compared to a Wellness intervention. Participants will receive assessments at baseline, 12 weeks (post-intervention), and follow-up assessments 3- and 9-months post-intervention. The primary outcome measure is the Brief Pain Inventory that examines pain intensity and pain interference.

Conclusion

This trial will produce valuable results that can have a meaningful impact on healthcare practices for GWI. If proven as a helpful treatment for individuals with GWI, it would support the implementation of remotely delivered Tai Chi classes that Veterans can access from their own homes.

Keywords: Gulf War Illness, Tai Chi, Wellness, Veteran, Complementary, Integrative

1. Introduction

1.1. Gulf War Illness

Approximately 700,000 American military personnel were deployed to the Persian Gulf region in 1990 and 1991 as part of the multinational coalition that responded to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. Following deployment, many service members and Veterans reported a cluster of health symptoms of unknown etiology that were subsequently labeled Gulf War Illness (GWI). These disparate and seemingly unrelated symptoms include widespread chronic musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, headaches, memory and attention difficulties, gastrointestinal complaints, skin abnormalities, breathing problems, and mood and sleep problems1, 2. This symptom complex has persisted for decades for many Veterans, and it is estimated that up to a third of those Veterans deployed to the Gulf War (GW) may have GWI4, 5. GWI has been characterized as a chronic multisymptom illness and includes 1) musculoskeletal pain, 2) fatigue, and 3) mood-cognition symptomology6. To be diagnosed with GWI, a Veteran must have served in the GW and experience at least one symptom in two of these symptom domains for at least six months6.

Since the 1990s when service personnel returning from the GW first evidenced higher rates of health problems, substantial research has focused on identifying possible etiologies with limited success. For example, a recent longitudinal study demonstrated an association between different neurotoxicant exposures (i.e., propane fuel emissions from tent heaters, anti-nerve gas pyridostigmine bromide pills, and proximity to a munitions demolition of the chemical warfare agents sarin/cyclosarin) and increased odds of reported cognitive/mood, fatigue, and neurological symptoms7. Despite these efforts, a summary of the 2016 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report8 concluded that “it is unlikely that a single definitive causal agent will be identified this many years after the war” (p.1508).

Importantly, GWI symptoms have not diminished over time but instead have remained stable or increased7. In fact, deployment to the GW is associated with higher rates of chronic health conditions common in the normative aging process: hypertension, diabetes, arthritis, and chronic bronchitis9 along with other significant health conditions, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis10. GW Veterans appear to age more quickly, exhibiting rates of medical conditions similar to non-deployed individuals a decade or more older9. Evidence of worsening of GWI symptoms and general accelerated aging intensifies the need for effective, safe, and tolerable treatments for these Veterans.

1.2. Tai Chi

Tai Chi, an ancient Chinese martial art and form of neuromotor exercise, may hold promise for Veterans experiencing GWI. Tai Chi is often described as “meditation in motion,” using an integrated mind-body approach that combines several therapeutic components in a synergistic way. The varied components of Tai Chi are generally considered to be: physical activity in the form of slow, graceful, low-impact movements; range of motion exercises and balance training; mental focus, visualization of body position and choreographed sequential forms; and deep diaphragmatic breathing and mindful relaxation11–13. The benefits of Tai Chi are wide-ranging, and it has been shown to be safe and to enhance physical and mental health and improve quality of life in patients with chronic conditions including, heart failure, cancer, osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, rheumatologic disease, and pulmonary disease14–21.

An umbrella review conducted by members of this investigative team examined studies of in-person Tai Chi. Five distinct symptom categories of GWI that Tai Chi has been demonstrated to benefit were enumerated: fatigue and sleep problems, psychological health, cognitive function, chronic pain, and respiratory function22. The review concluded that Tai Chi may have the potential to improve functioning in GW Veterans though “a diverse, interrelated, reciprocal and potentially synergistic set of mechanistic pathways” (p. 170) including deep breathing and relaxation, group participation, physical activity, learning and memorization of movement patterns, and mindful awareness, attention, and meditation.

Other indications that Tai Chi may prove useful in the treatment of GWI is the empirical support for the treatment of another multicomponent disorder, fibromyalgia23, which has important parallels to GWI. Compared to healthy GW Veterans, GW Veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain report exercise as more painful, and they experience increased pain sensitivity following acute exercise at similar rates as individuals with fibromyalgia24, 25. Abnormal central nervous system processing of sensory and painful stimuli has been identified in subgroups of Veterans with GWI24, 25, similar to what has been found in those with fibromyalgia. Tai Chi has also been shown to have a positive effect on other symptoms associated with GWI, including both mood23 and fatigue26. These findings, taken together, suggest that Tai Chi may benefit Veterans with GWI.

The practicality of delivering Tai Chi in military populations has been demonstrated in several small-scale feasibility or pilot studies27–30. For example, research conducted by the current authors showed that recruitment of Veterans for Tai Chi is feasible with reported high satisfaction29. Qualitative findings indicated that Tai Chi may be a particularly good fit for military populations as it is derived from the martial arts and defense training, resonating in a positive way with their military training and ‘warrior spirit.’ Thus, investigation of Tai Chi to address symptoms of GWI is merited at this time.

1.3. Remote delivery of mind body interventions

Pre-pandemic research demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of synchronous videoconferencing therapies in the treatment of Veterans. When compared with in-person care to address PTSD in Veterans, for example, videoconferencing dropout rates were similar, outcomes were non-inferior, and both satisfaction and therapeutic alliance were comparable31. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, both the need for behavioral health treatment and the use of videoconferencing have increased dramatically32, 33 Online mind-body interventions, such as Tai Chi, yoga, and mindfulness, have been highly utilized for general stress reduction34, though most are asynchronous . It is important to determine if interactive and synchronous remote delivery of these interventions can lead to a reduction in key symptoms associated with Gulf War Illness, such as pain.

1.4. The current investigation

In March 2020, our randomized trial for GWI symptoms comparing Tai Chi to Wellness (an attention control group) was halted mid-way due to the onset of COVID-19. In the latter part of 2020, the investigators received permission from the funding source and Investigational Review Board (IRB) to shift from conducting an in-person intervention study to develop and examine Tai Chi and Wellness delivered via synchronous video teleconferencing. Important changes included: Tai Chi movement sequences that requiring stepping across the floor were replaced with components that could be done standing in one place; physical activity and neuropsychological outcome measures were replaced with psychometric measures that could be completed remotely; since the virtual platform affords fewer opportunities for spontaneous interaction among group members and instructors, group leaders were more directive in facilitating interactions and providing feedback. Given the distinct differences between the in-person and virtual protocols, we elected to consider them as two separate studies. The protocol for the ongoing fully remote trial is presented here.

In light of the opioid crisis, there is a need for research that focuses on identifying effective nonpharmacologic treatments for chronic pain. The primary aim of the current study is to examine if a synchronously delivered remote 12-week Tai Chi intervention is associated with greater improvements in pain and other GWI symptoms compared to the 12-week synchronously delivered remote Wellness intervention. The second aim is to examine if Tai Chi is associated with greater improvements in other physical and psychological measures compared to the Wellness intervention. The third aim is to examine the feasibility and acceptability of both the Tai Chi and Wellness interventions. This trial will produce valuable results that can have a direct and immediate impact on healthcare practices for GWI. If proven as helpful, these non-pharmaceutical, remotely accessible interventions could be implemented across VA nationwide with Veterans able to participate from their own homes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants are up to 72 Veterans who were deployed to the Persian Gulf region in 1990–1991 in Operation Desert Shield and/or Operation Desert Storm and report symptoms consistent with GWI1, 6. Please refer to Table 1 for the list of inclusion and exclusion criteria and rationale.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria and Rationale

| Inclusion criteria | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Veteran who served in the 1990–91 Gulf War Theatre | Population under study |

| Meet GWI criteria using criteria of having at least 1 chronic symptom in 2 symptom domains (i.e., 1) musculoskeletal pain 2) fatigue, and 3) mood-cognition symptomology)6 | Population under study |

| Musculoskeletal or joint pain or stiffness for at least 6 months must be one of the GWI symptoms | Population under study |

| English speaking | Practical consideration |

| Ability to attend group sessions at scheduled times | Practical consideration |

| Access to a computer or tablet device for sessions | Practical consideration |

| Exclusion criteria | Rationale |

| Lacks capacity to consent | Human subjects concern |

| Major medical, psychiatric, or neurological disorder or brain injury that could interfere with ability to safely engage in study activities | Human subjects concern and safety consideration |

| Change in psychotropic or pain medication in past month | Treatment confound |

| Current Tai Chi, mindfulness, or yoga practice for at least 3 hours per week for more than 3 months | Treatment confound |

| Difficulty standing for 60 minutes | Safety consideration |

| Disruptive, disrespectful, or threatening to staff or Veterans and non-responsive to limit setting | Safety consideration |

| Current involvement in a treatment study for GWI or pain | Treatment confound |

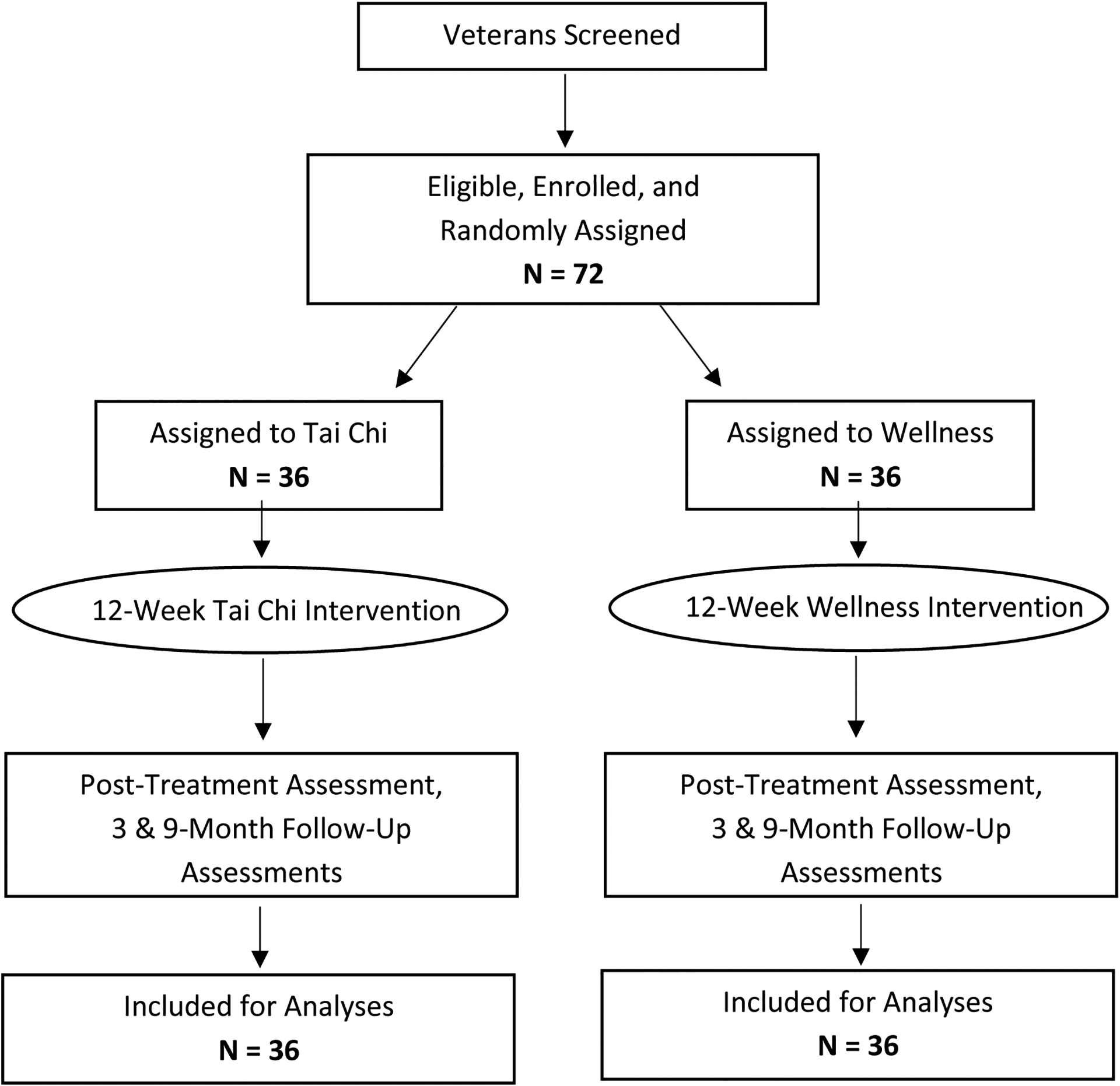

2.2. Study design

In this single-blind randomized controlled trial, GW Veterans are randomly assigned to either the Tai Chi or the Wellness conditions, with both groups meeting remotely twice a week for 12 weeks. Participants in both conditions receive assessments at baseline, 12 weeks (post-intervention), 24 weeks (approximately 3 months post-intervention) and 48 weeks (approximately 9 months post-intervention). Six cohorts of 12 Veterans each are planned. See Figure 1 for the participant flow.

Figure 1.

Planned Participant Flow

2.2.1. Adaptations to study design and procedures for telehealth format

In order to adapt the protocol from an in-person to a fully remote format, a number of changes and adaptations were made to the consent process, the assessments and procedures, and the synchronously delivered telehealth interventions. Please see Figure 2 for a summary.

Figure 2:

Study Design Adaptations and Procedures for Telehealth Format

2.2.2. Ethical oversight

The study protocol is approved by the IRB at the VA Boston Healthcare System. Clinical trial registration was completed at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02661997).

2.3. Study procedures

2.3.1. Recruitment

Participants are recruited using a variety of strategies. Please see Table 2 for a description of the methods used. As all aspects of the study are conducted remotely, Gulf War Veterans from anywhere in the United States are eligible to participate.

Table 2.

Recruitment Methods

| Description of Recruitment Methods |

|---|

| Medical center staff are informed and provided with IRB-approved pamphlets describing the study. If Veterans sign IRB-approved “permission to contact” forms, study staff contact them for telephone screening. |

| Utilization of an electronic referral data repository maintained by the National Center for PTSD into which Veterans were previously entered on a voluntary basis and written permission for future contact was established. |

| Mailing IRB-approved letters to Veterans in the VA Boston Healthcare System identified as serving on active duty in 1990 and/or 1991. A pre-addressed, postage paid postcard is enclosed to provide the ability to opt out of being contacted. Veterans who do not opt out within two weeks of letters being mailed are eligible to be contacted by study staff. |

| Recontacting Veterans who were screened for a previous trial who may be eligible to participate (as allowed by IRB approval of a HIPAA waiver). |

| IRB approved flyers, brochures and link to the study website posted to Veteran social media platforms such as GW Veterans Facebook groups and pages. |

2.3.2. Screening

In the initial telephone screening, Veterans are provided with an overview of the study. If they express interest, study staff briefly assess for all inclusion/exclusion criteria (see Table 1). Veterans are recruited in cohorts of 8 to 16 during one-month intensive recruitment periods. Once a cohort of Veterans is assembled, baseline assessments are scheduled.

2.4. Randomization

Randomization occurs after baseline assessments for all members of the cohort are completed. Within the week prior to randomization, study staff confirm that each participant is still interested and able to attend at the time that both interventions are scheduled. A study staff member then makes a list of available cohort participants in order of completion of initial telephone screening. The cohort list is password-protected and unavailable to the principal investigator (PI). The PI then uses the list randomizer from Random.org (https://www.random.org/lists/) to create a randomly ordered list of the group assignments equally distributed between Tai Chi and Wellness and equal to the size of the cohort, rounding up to an even number. The PI’s list of group assignments is then matched with the numbered list of participants. Study staff then call participants to inform them of their condition assignment and the days and times of the group intervention to which they have been assigned.

2.5. Assessment Instruments and Procedures

Assessments consist of staff-administered interviews and self-report assessment questionnaires. Assessments last approximately 90 to 120 minutes and the staff-administered components are completed via WebEx. Treatment condition is assigned after the baseline, so all study staff are blind to condition throughout the baseline assessment. Please see Table 3 for full list of measures and time of administration. Instruments that align with the GWI domains and Common Data Elements (CDEs) recommended by GWI research community stakeholders35 are also indicated. Two measures included in the post-treatment and follow-up assessments (Qualitative feedback interview and Seven-day physical activity recall) lead participants to discuss treatment condition, so they are administered by an unblinded staff member who does not lead the group to which the participants are assigned. Weekly phone calls are made during the interventions to assess pain, group cohesion, and home practice, also conducted by an unblinded staff member not leading the group. The remaining post-treatment and follow-up measures are administered remotely (via postal mail).

Table 3.

Schedule and Description of Measures

| Measure | Pre | Post | 3-Mo | 9-Mo | Weekly During Tx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gulf War Illness Outcome Measures | |||||

| Primary Outcome Measure | |||||

| Brief pain inventory – short form. A 9-item self-report measure that examines pain intensity and interference with functioning in various life domains36, 37. [Aligns with CDE Domain: Pain35] | X | X | X | X | X |

| Secondary Outcome Measures | |||||

| Multi-dimensional fatigue inventory. A 20-item self-report measure that examines symptoms of fatigue. The questions pertain to general, physical, and mental fatigue in addition to reduced motivation and activity38. [Aligns with CDE Domain: Fatigue35] | X | X | X | X | |

| Depression anxiety stress scales. A 21-item self-report measure that examines emotional states of depression, anxiety and stress39.[Aligns with CDE Domain: Neuropsychological35] | X | X | X | X | |

| Physical and Psychological Outcome Measures | |||||

| Pain Catastrophizing Scale. A 13-item self-report measure that examines the extent to which participants catastrophize pain in the forms of rumination, magnification, and helplessness40. | X | X | X | X | |

| PTSD checklist for DSM-5. A 20-item self-report measure that examines symptoms of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder criteria over the past month41, 42. [Aligns with CDE Domain: Neuropsychological35] | X | X | X | X | |

| Insomnia severity index. A 7-item self-report measure that is used as a brief screen of insomnia symptoms and is sensitive measure of change in perceived sleep difficulties43. [Aligns with CDE Domain: Sleep35] | X | X | X | X | |

| PROMIS self-efficacy for managing symptoms short form. An 8-item self-report measure that examines elements of self-care44. | X | X | X | X | |

| PROMIS global health scale short form. An 8-item self-report measure that examines physical function, fatigue, pain, emotional distress, and social health45. [Aligns with CDE Domain: Quality of Life35] | X | X | X | X | |

| Chronic pain self-efficacy scale. A 22-item self-report measure that examines perceived self-efficacy to cope with components chronic pain such as pain management, physical function, and coping with symptoms46. | X | X | X | X | |

| West Haven-Yale multidimensional pain inventory. A 52-item self-report measure that examines experiences with chronic pain and engagement in everyday activities47. [Aligns with CDE Domain: Pain35] | X | X | X | X | |

| Mindful attention awareness scale. A 15-item self-report measure that assesses participants’ openness towards, awareness of, and attention to the present. This scale can reveal information about one’s self-regulation and well-being48. | X | X | X | X | |

| Seven-day physical activity recall. A variable-length measure that is administered by the study staff in an interview format. Examines participants’ recall of the amount of time they engaged in moderate, hard, and very hard physical activity and time spent sleeping each day over the past week49. [Aligns with CDE Domain: Post-Exertional Malaise35] | X | X | X | X | |

| Measures of Feasibility and Acceptability | |||||

| Client satisfaction questionnaire. An 8-item self-report measure that examines participants’ satisfaction with services provided50. | X | ||||

| Qualitative Interview. A variable-length, semi-structured interview developed for this study that gathers qualitative information about the participants’ experience with the content and modality (telehealth group format) of the intervention and that is audio recorded with participant consent. | X | X | X | ||

| Tai Chi Home Practice Log. Number of days per week and minutes per practice session are recorded weekly during treatment. | X | ||||

| Weekly Wellness Goals Log. SMART Goals and progress ratings are recorded weekly during treatment. | X | ||||

| Group cohesiveness scale. A 7-item self-report measure that examines group cohesion within a therapeutic atmosphere51. | X | ||||

| Measure of Distress Related to COVID-19 and Social Distancing | |||||

| Epidemic – pandemic impacts inventory. A 92-item questionnaire. Designed to learn about and describe the impact of the coronavirus disease pandemic on various domains of personal and family life, including employment, education, home life, social life, economic, physical health, infection experiences, and positive changes52. | X | X | X | ||

| Descriptive Measures | |||||

| Demographics: A 12-item self-report measure that examines age, years of education, gender, sex, race, ethnicity, relationship/marital status, employment status, current living situation, number and age of children (if any), and internet accessibility. [Aligns with CDE Domain: Baseline/Covariate35] | X | ||||

| The Kansas Gulf War experiences and exposures questionnaire part 1. A 32-item self-report measure that queries about chronic symptoms and diagnoses required to ascertain Kansas and Chronic Multi-symptom Illness (CMI) case status 1. [Aligns with CDE Domain: Baseline/Covariate35] | X | X | X | X | |

| The Kansas Gulf War experiences and exposures questionnaire part 2. A 36-item self-report measure that queries about demographics such as military rank and current military status, GW duty service (active vs. reserve/National Guard), military and deployment history, and exposures1. [Aligns with CDE Domain: Baseline/Covariate35] | X | ||||

| Health symptom checklist. A 34-item self-report measure that examines health and mental health symptoms over the past 30 days. The symptoms assessed fall under the following categories: cardiac, pulmonary, dermatological, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, musculoskeletal, neurological, and psychological7, 53. Within this measure there are 5 embedded items that address malingering behaviors54. [Aligns with CDE Domain: Baseline/Covariate35] | X | X | X | X |

2.6. Treatment Conditions

2.6.1. Tai Chi Treatment.

The standardized protocol was modeled after a Tai Chi program tested in previous randomized controlled trials19, 20, 23, 55. The program is derived from the classical Yang Tai Chi 108 postures56, which has been shown to be a moderate-intensity exercise13. The movements and postures were selected by the instructors (BM and BW) because they: (1) are easily comprehensible and can be taught via remote instruction; (2) represent progressive degrees of stress to postural stability, with weight-bearing moving from bilateral to unilateral supports; (3) emphasize increasing magnitude of trunk and arm rotation with diminishing base of support and, as such, will potentially improve physical function without excessively stressing the joints; and (4) include meditative qualities. The Qigong movements included are: Expanding the qi field, Arching the chest to cleanse the body, Pour qi down the bai hui, Push the mountains side to side, Press forward and settle the wrists, Bear swims in water, Eagle gathers the prey, and Crane spreads wings. The Tai Chi forms included are: Begin Tai Chi, Repulse the monkey, Brush knee, and Cloud hands. Classes are tailored as needed for participant flexibility and endurance.

Each Tai Chi session lasts approximately 60 minutes and occurs twice per week for 12 weeks. Participants are also provided with a printed Participant Manual which includes Tai Chi principles, practicing techniques, and safety precautions. Throughout the group sessions, the instructors provide education about the guiding principles of Tai Chi that can help both the mind and body. Every session includes the following components: (1) warm up and a review of Tai Chi principles; (2) meditation with Tai Chi movement; (3) breathing techniques; and (4) relaxation. A research assistant attends each session and completes a fidelity checklist to record instructor adherence to the above components. Participants are encouraged to practice at home using home practice exercises described in the Participant Manual and video recordings accessible to participants on a website. During weekly phone calls with study staff, participants provide information on how many minutes of Tai Chi home practice they engage in each day of the week.

2.6.2. Wellness Comparison.

Previous randomized trials by our investigative group have used a Wellness Education control intervention as an attention control comparison for Tai Chi and found that Tai Chi had a significantly greater impact on symptoms23, 55. Given the successful use of Wellness Education control as a comparator to Tai Chi, it was determined that a Wellness intervention is a suitable attention control group for this randomized controlled trial. Participants in the Wellness condition also attend two 60-minute sessions per week for 12 weeks. A standardized protocol was developed to correspond to the VA Whole Health Program57 and to emphasize wellness across various domains that impact physical and emotional health. Topics covered during the 12-week group include physical activity, personal development, healthy eating and substance use, relationships, spirituality, mind-body connection, and personal environment and surroundings. Participants are encouraged to set SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic and Timely) goals each week to increase the likelihood of meeting their objectives58. Every session includes: (1) review of the written materials for that session; (2) a brief video clip related to the topic being discussed; (3) a brief mindfulness meditation exercise led by an instructor; and (4) review of SMART goals. One of the group leaders completes fidelity checklists after each group to record coverage of the topics and treatment components.

2.6.3. Expertise and program adherence of Tai Chi instructors

Two instructors trained in Yang-style Tai Chi (BM and BW), each with over 20 years of experience teaching Tai Chi are hired for the project. Each instructor will teach 3 cohorts of 24 classes, with occasional substitutions for each other in cases of illness or travel.

2.6.4. Expertise and program adherence of Wellness group leaders

The Wellness group is co-facilitated by two study staff consisting of at least one clinical psychologist or trainee with a doctorate in clinical psychology. All groups are facilitated or supervised by one of the Principal Investigators who are licensed clinical psychologists.

2.7. Safety Protocol

To optimize safety, we exclude individuals with major medical, psychiatric, or neurological disorders or moderate to severe traumatic brain injury and any medical conditions that carry a risk to safe participation. Each Tai Chi session begins with warm-up and stretching exercises to prevent injury and participants are provided with opportunities to report any negative effects they may have experienced. At least one research staff member is present at all intervention classes.

All study personnel complete required trainings in ethics, human subjects, data integrity, and information security. All data with identifying information is stored in locked files or password-protected computer files on secure servers. Data for analysis are identified by participant codes, and identifying information is removed. The identity of participants will not be revealed in the presentation or publication of any results from the project.

2.8. Strategies to minimize nonadherence and attrition

To minimize the likelihood that participants will drop out due to schedule conflicts, study staff call participants prior to randomization to verify availability on the days and times of sessions. During the treatment phase, study staff call participants who cancel or do not show for sessions. Participants who have not been in contact for more than a week or who cancel several consecutive sessions are called by study staff and every effort is made to reengage them. During weekly phone calls to administer measures and record home practice, participants are given opportunities to provide feedback. Study classes are scheduled mid-day (between 11am and 2pm Eastern) to maximize ability for employed participants to attend during lunch breaks and to include participants in other time zones. To minimize cancellation and rescheduling of sessions, back-up instructors are available for both treatment conditions. Tai Chi instructors and the Wellness Group leader and/or supervisor attend weekly team meetings to problem-solve issues that arise (i.e. unable to access videos for home practice, limitations related to previous injuries, ongoing physical or mental health issues) that may interfere with class participation. In response to feedback obtained in a feasibility study of Tai Chi29, one of the study investigators attends each Tai Chi class to address issues that may arise to allow the Tai Chi instructor to focus on session content.

2.9. Data analytic strategy

2.9.1. Participant Attrition and Missing Data.

Rigorous attempts are made to keep participants engaged in the study and to gather complete data regardless of treatment completion. We anticipate incomplete data due to factors such as attrition, participant unwillingness, and time constraints. We plan to conduct intention-to-treat analyses with all randomized participants to protect against potential bias and will use recommended imputation procedures for missing data59.

2.9.2. Aims 1 and 2: Differential treatment effects

For Aim 1, we will utilize two approaches to determine whether participants in the Tai Chi Condition show more advantageous change on the BPI than those in the Wellness Condition. First, using the 4 assessment points (baseline, post-intervention, 3-month follow-up, and 9-month follow-up), we will fit longitudinal mixed models and will include a treatment condition by time interaction term to evaluate whether there are differential changes in the treatment groups over time. Log-transformed scores for the outcomes will be used in the analysis as needed. Results will be presented as between-group differences with 95% confidence intervals based on estimates from the longitudinal models. All model assumptions will be checked with standard regression diagnostic evaluations. These analyses will be based on all available data.

Second, we will utilize data from the weekly administrations of the BPI to model the trajectories of each group over the intervention period and present them graphically. We will fit longitudinal mixed models and will include a treatment condition by time interaction term to evaluate whether there are differential changes in the treatment groups over the intervention period.

For Aim 2, we will use a similar approach to Aim 1 to determine whether participants in the Tai Chi Condition show more advantageous change than those in the Wellness Condition across the 4 assessment points on the other physical and psychological measures. (There are no weekly administrations of the secondary measures.)

2.9.3. Aim 3: Feasibility and acceptability

For Aim 3, to examine the feasibility and acceptability of the two treatments, descriptive and summary statistics will be utilized to examine participant adherence (number of sessions attended) and satisfaction as reported on the client satisfaction questionnaire. Qualitative analysis of interviews will be conducted using an iterative coding process. Qualitative data will be transcribed and then analyzed by the research team using a general inductive approach60. Two or more raters will independently code several transcripts to identify themes. The team will review identified themes, discuss discrepancies, and refine the coding rubric. Raters will code the remaining transcripts and meet until consensus is reached on the identified themes and on the distribution of participant quotes under appropriate themes. The team will then choose and report participant quotes that best represent the identified themes.

2.9.4. Power analyses and sample size for Aims 1 and 2

With the anticipated 72 participants enrolled (36 in each condition), assuming that 15% do not complete the post-treatment assessment, we will have sufficient (.80) power to show a medium-large between group effect (0.72) as has been found in previous similar trials23, 61.

3. Discussion

This manuscript describes the first fully remote clinical trial to address symptoms of GWI using Tai Chi. We were spurred by pandemic restrictions to switch from in-person to remote delivery for this trial. However, even prior to 2020, examination of remotely delivered interventions for Veterans was important for behavioral treatments in general and for GWI populations in particular. Videoconferencing telehealth therapies gained prominence over the past decades due to their convenience and potential to save costs for both providers and patients. Remote interventions that allow synchronous interactions simulate in-person treatment delivery and allow real time feedback from instructors as well as live interactions among group members.

To adapt to the remote format in the current study, practical and substantive changes were made to the interventions and assessment instruments. Differences in remote group dynamics and virtual interactions among participants and instructors may affect outcomes. For example, muting participants during Tai Chi class is needed to ensure clear delivery of instruction and directed taking of turns in Wellness discussions avoids talking over other group members. The virtual platform and these necessary adaptations may inhibit socialization, constrain development of group cohesion, and limit the sense of camaraderie among participants. Nonetheless, for GW Veterans who appreciate connection with other Veterans of their era, videoconferencing may have a particular advantage in improving access to care. The relatively small numbers of GW Veterans in most geographic areas make in-person group treatments targeting GWI largely impractical. Thus, focus on the remote delivery of these two interventions will provide the opportunity to advance our understanding of the effectiveness of mind body treatments when delivered via synchronous telehealth.

After three decades of research on GWI, high quality clinical trials to identify feasible, acceptable, and efficacious treatments for GWI symptoms have been scant. The 2016 IOM report5 recommended a shift in focus—from attempts to establish etiology to the development and evaluation of therapeutic interventions for managing the symptoms of GWI. Investigation of mind-body treatments that focus on “the interconnectedness of the brain and body” (p. 249)5 were specifically recommended. Indeed, recent studies have suggested that complementary and integrative mind-body therapeutic approaches such as yoga61, acupuncture62, and mindfulness63 may be fruitful approaches to explore to reduce GWI symptoms and improve functioning. However, current VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Chronic Multisymptom Illness indicates that evidence to support these interventions remains weak3. The current study will add to this growing body of literature on integrative, nonpharmacologic approaches by providing evidence on the viability of telehealth delivery. If shown to be effective and engaging, the remotely delivered Tai Chi interventions offered in this study can be used to promote health while also providing social connection for Veterans suffering from GWI. Offering home-based synchronous teleconferencing interventions that address mind and body to Veterans who served in the Gulf over 30 years ago will represent a notable step in health promotion for this important group of Veterans.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

There is a need for high-quality intervention trials for Gulf War Illness

Tai Chi shows promise to address pain and improve functioning in Gulf War Illness

Using telehealth therapies for Gulf War Veterans can improve access to care

Acknowledgement

This manuscript represents original work that has not been published previously and it is not under concurrent review elsewhere. The investigators are solely responsible for the contents of the manuscript and they do not represent official views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. No conflicts of interest exist for any of the authors.

Funding:

This work is supported by a grant funded through the Veterans Administration Clinical Science Research and Development Service (grant number: SPLD-004-15S). Dr. Chenchen Wang is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH, R01AT006367, R01AT005521 and K24AT007323) and the Rheumatology Research Foundation Innovative Research Award.

Abbreviations:

- GW

Gulf War

- GWI

Gulf War Illness

- BPI

Brief Pain Inventory

- IOM

Institute of Medicine

- SMART

Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic and Timely

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Steele L. Prevalence and patterns of Gulf War illness in Kansas veterans: association of symptoms with characteristics of person, place, and time of military service. American journal of epidemiology. 2000;152(10):992–1002. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.10.992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iannacchione VG, Dever JA, Bann CM, et al. Validation of a research case definition of Gulf War illness in the 1991 US military population. Neuroepidemiology. 2011;37(2):129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Management of Chronic Multisymptom Illness CMI 2021 (2021).

- 4.Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses. Gulf War Illness and the Health of Gulf War Veterans: Research Update and Recommendations, 2009–2013, Updated Scientific Findings and Recommendations. Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs. 2014; [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine. Gulf War and health: Volume 10: Update of health effects of serving in the Gulf War. 2016;doi: 10.17226/21840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukuda K, Nisenbaum R, Stewart G, et al. Chronic multisymptom illness affecting Air Force veterans of the Gulf War. Jama. 1998;280(11):981–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yee MK, Zundel CG, Maule AL, et al. Longitudinal assessment of health symptoms in relation to neurotoxicant exposures in 1991 Gulf War Veterans: The Ft. Devens Cohort. Journal of occupational and environmental medicine. 2020;62(9):663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.IOM. Gulf War and Health: Volume 10: Update of Health Effects of Serving in the Gulf War, 2016. Mil Med. 2017;182:1507–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zundel CG, Krengel MH, Heeren T, et al. Rates of chronic medical conditions in 1991 Gulf War veterans compared to the general population. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2019;16(6):949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horner RD, Grambow SC, Coffman CJ, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis among 1991 Gulf War veterans: evidence for a time-limited outbreak. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;31(1):28–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wayne PM, Kaptchuk TJ. Challenges inherent to t’ai chi research: part II—defining the intervention and optimal study design. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2008;14(2):191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solloway MR, Taylor SL, Shekelle PG, et al. An evidence map of the effect of Tai Chi on health outcomes. Syst Rev. Jul 27 2016;5(1):126. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0300-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lan C, Lai JS, Chen SY. Tai Chi Chuan: An ancient wisdom on exercise and health promotion. Sports Medicine. 2002;32(4):217–24. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200232040-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y-W, Hunt MA, Campbell KL, Peill K, Reid WD. The effect of Tai Chi on four chronic conditions—cancer, osteoarthritis, heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analyses. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2016;50(7):397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song R, Grabowska W, Park M, et al. The impact of Tai Chi and Qigong mind-body exercises on motor and non-motor function and quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. Aug 2017;41:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2017.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor-Piliae R, Finley BA. Benefits of tai chi exercise among adults with chronic heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2020;35(5):423–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang C Role of Tai Chi in the treatment of rheumatologic diseases. Current rheumatology reports. 2012;14(6):598–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang C, Bannuru R, Ramel J, Kupelnick B, Scott T, Schmid CH. Tai Chi on psychological well-being: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies. 2010;10(1):23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang C, Schmid CH, Fielding RA, et al. Effect of tai chi versus aerobic exercise for fibromyalgia: comparative effectiveness randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2018;360:k851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang C, Schmid CH, Iversen MD, et al. Comparative effectiveness of Tai Chi versus physical therapy for knee osteoarthritis: A randomized trial. Annals of internal medicine. 2016;165(2):77–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang C, Collet JP, Lau J. The effect of Tai Chi on health outcomes in patients with chronic conditions: A systematic review. Archives of internal medicine. 2004;164(5):493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reid KF, Bannuru RR, Wang C, Mori DL, Niles BL. The effects of tai chi mind-body approach on the mechanisms of gulf war illness: an umbrella review. Integrative Medicine Research. 2019;8(3):167–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang C, Schmid CH, Rones R, et al. A randomized trial of Tai Chi for fibromyalgia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(8):743–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cook DB, Stegner AJ, Ellingson LD. Exercise alters pain sensitivity in Gulf War veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain. The Journal of Pain. 2010;11(8):764–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gopinath K, Gandhi P, Goyal A, et al. FMRI reveals abnormal central processing of sensory and pain stimuli in ill Gulf War veterans. Neurotoxicology. 2012;33(3):261–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiang Y, Lu L, Chen X, Wen Z. Does Tai Chi relieve fatigue? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0174872. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yost TL, Taylor AG. Qigong as a novel intervention for service members with mild traumatic brain injury. Explore (NY). May-Jun 2013;9(3):142–9. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2013.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reb AM, Saum NS, Murphy DA, Breckenridge-Sproat ST, Su X, Bormann JE. Qigong in Injured Military Service Members. J Holist Nurs. Mar 2017;35(1):10–24. doi: 10.1177/0898010116638159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niles BL, Mori DL, Polizzi CP, Pless Kaiser A, Ledoux AM, Wang C. Feasibility, qualitative findings and satisfaction of a brief Tai Chi mind-body programme for veterans with post-traumatic stress symptoms. BMJ Open. Nov 29 2016;6(11):e012464. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munro S, Komelski M, Lutgens B, Lagoy J, Detweiler M. Improving the Health of Veterans Though Moving Meditation Practices: A Mixed-Methods Pilot Study. Journal of Veterans Studies. 2019;5(1):16–23. doi: 10.21061/jvs.v5i1.128 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morland LA, Mackintosh MA, Glassman LH, et al. Home‐based delivery of variable length prolonged exposure therapy: A comparison of clinical efficacy between service modalities. Depression and anxiety. 2020;37(4):346–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou X, Snoswell CL, Harding LE, et al. The role of telehealth in reducing the mental health burden from COVID-19. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2020;26(4):377–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pierce BS, Perrin PB, Tyler CM, McKee GB, Watson JD. The COVID-19 telepsychology revolution: A national study of pandemic-based changes in US mental health care delivery. American Psychologist. 2021;76(1):14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trevino KM, Raghunathan N, Latte-Naor S, et al. Rapid deployment of virtual mind-body interventions during the COVID-19 outbreak: Feasibility, acceptability, and implications for future care. Support Care Cancer. Sep 9 2020;doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05740-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen DE, Sullivan KA, McNeil RB, et al. A common language for Gulf War Illness (GWI) research studies: GWI common data elements. Life Sci. Feb 1 2022;290:119818. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: Global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Annals, Academy of Medicine, Singapore. 1994;23(2):129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cleeland CS. The Brief Pain Inventory User Guide. 2009. p. 1–63.

- 38.Smets E, Garssen B, Bonke Bd, De Haes J. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. Journal of psychosomatic research. 1995;39(3):315–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour research and therapy. 1995;33(3):335–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(4):524. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, Schnurr PP. The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). www.ptsd.va.gov

- 42.Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress. Dec 2015;28(6):489–98. doi: 10.1002/jts.22059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep medicine. 2001;2(4):297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gruber-Baldini AL, Velozo C, Romero S, Shulman LM. Validation of the PROMIS® measures of self-efficacy for managing chronic conditions. Quality of Life Research. 2017;26(7):1915–1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2010;63(11):1179–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anderson KO, Dowds BN, Pelletz RE, Edwards WT, Peeters-Asdourian C. Development and initial validation of a scale to measure self-efficacy beliefs in patients with chronic pain. Pain. 1995;63(1):77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kerns RD, Turk DC, Rudy TE. The west haven-yale multidimensional pain inventory (WHYMPI). Pain. 1985;23(4):345–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of personality and social psychology. 2003;84(4):822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sallis JF, Haskell WL, Wood PD, et al. Physical activity assessment methodology in the Five-City Project. American journal of epidemiology. 1985;121(1):91–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, Nguyen TD. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: Development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1979/01/01/ 1979;2(3):197–207. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wongpakaran T, Wongpakaran N, Intachote‐Sakamoto R, Boripuntakul T. The group cohesiveness scale (GCS) for psychiatric inpatients. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2013;49(1):58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grasso DJ, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Ford JD, Carter A. The epidemic–pandemic impacts inventory (EPII). University of Connecticut School of Medicine. 2020; [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bartone PT, Ursano RJ, Wright KM, Ingraham LH. The impact of a military air disaster on the health of assistance workers. Journal of nervous and mental disease. 1989;177(6):317–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vanderploeg RD, Curtiss G. Malingering assessment: evaluation of validity of performance. NeuroRehabilitation. 2001;16(4):245–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang C, Schmid CH, Hibberd PL, et al. Tai Chi is effective in treating knee osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care & Research: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology. 2009;61(11):1545–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.China Sports. Simplified “Taijiquan”. Beijing: China Publications Center. 1983:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 57.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. What is Whole Health? Accessed September 21, 2022. https://www.va.gov/wholehealth/

- 58.Doran GT. There’sa SMART way to write management’s goals and objectives. Management review. 1981;70(11):35–36. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rombach I, Gray AM, Jenkinson C, Murray DW, Rivero-Arias O. Multiple imputation for patient reported outcome measures in randomised controlled trials: advantages and disadvantages of imputing at the item, subscale or composite score level. BMC medical research methodology. 2018;18(1):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American journal of evaluation. 2006;27(2):237–246. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bayley PJ, Schulz-Heik RJ, Cho R, et al. Yoga is effective in treating symptoms of Gulf War illness: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2021;143:563–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Conboy L, Gerke T, Hsu K-Y, St John M, Goldstein M, Schnyer R. The effectiveness of individualized acupuncture protocols in the treatment of Gulf War Illness: a pragmatic randomized clinical trial. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0149161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kearney DJ, Simpson TL, Malte CA, Felleman B, Martinez ME, Hunt SC. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in addition to usual care is associated with improvements in pain, fatigue, and cognitive failures among veterans with gulf war illness. The American journal of medicine. 2016;129(2):204–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.