Abstract

Objective:

To describe smoking behaviors and pharmaceutical cessation aid uptake in a population-based Indigenous cohort compared to an age and sex-matched non-Indigenous cohort.

Patients and Methods:

Utilizing the health record-linkage system of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (January 1st, 2006 to December 31st, 2019), smoking data of Indigenous residents of Olmsted County in Minnesota were abstracted to define the smoking prevalence, incidence, cessation, relapse after cessation, and pharmaceutical smoking cessation aid uptake compared to a matched non-Indigenous cohort. Prevalence was analyzed with a modified Poisson regression, cessation and relapse were evaluated with generalized estimating equations. Incidence was evaluated with a Cox proportional hazard model.

Results:

Smoking prevalence was higher in the Indigenous cohort (39–47%; N=898) than the matched cohort (26–30%; N=1780). Pharmaceutical uptake was higher amongst the Indigenous cohort (35.8% vs. 16.3%; p<0.001). Smoking cessation events occurred more frequently in the Indigenous cohort (RR: 1.10, 95% CI:1.06–1.13, p<0.001). Indigenous former smokers were more likely to resume smoking (RR: 3.03, 95% CI:2.93–3.14, p<0.001) compared to the matched cohort. These findings were independent of socioeconomic status, age, and sex.

Conclusion:

Smoking in this Indigenous cohort was more prevalent compared to a sex and age matched non-Indigenous cohort despite more smoking cessation events and higher utilization of smoking cessation aids in the Indigenous cohort. The relapse rate after achieving cessation in the Indigenous cohort was over three times higher than the non-Indigenous cohort. This finding has not been previously described and represents a potential target for relapse prevention efforts in United States Indigenous populations.

Introduction:

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), the estimated smoking prevalence in Indigenous Americans (American Indians and Alaska Natives) is the highest among all ethnic subgroups in the United States (US) at 32%, compared to a 14% composite prevalence for all adults in the US.1–3 Smoking tobacco products increases risk of cancer, respiratory diseases, and mortality.4 Addressing smoking prevalence begins with delineating existing smoking behaviors.5

Regional variations in Indigenous smoking behaviors presents a challenge when assessing smoking behaviors. For example, an estimated 44% of Indigenous adults in the Northern Plains region smoke, compared to 21% of Indigenous adults surveyed in Southwestern tribes.6 Representation of Indigenous people in research demonstrates an additional challenge. Indigenous people are less likely to be represented in published data and less likely to participate in survey research compared to the general population.7 Further, cross-sectional survey design methods limit the understanding of smoking initiation, cessation, and smoking relapse behaviors in Indigenous groups.

A population-based study of Indigenous smoking behaviors can offer invaluable insights for guiding future interventions to address smoking disparities.7 Utilizing the Rochester Epidemiology Project, a record linkage system allowing an inclusive review of health data for residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, a population-based study of Indigenous smoking behaviors was completed to understand smoking behaviors of Indigenous people. Olmsted County, Minnesota, is located on Dakota land.8 The modern state of Minnesota is home to eleven reservation communities, four Dakota Reservations in southern Minnesota, and seven Anishinaabe Reservations in northern Minnesota.8 Although Olmsted County does not include a Reservation community, the city of Rochester represents an urban native community with diverse tribal nations represented.9 Considering the modern Indigenous population, urban Indigenous people represent the largest communities in the United States, with an estimated 71% of modern Indigenous people residing in urban communities today.9

The state of Minnesota instituted the Minnesota Clean Indoor Air Act in 2007 prohibiting the use of smoked tobacco in all enclosed indoor spaces.10 In 2017, Olmsted county banned the use of vaping devices in enclosed spaces prior to the state wide mandate banning use instituted in 2019.10, 11 To date, there are no specific smoking resources offered for Indigenous people living in Olmsted County.

To understand the existing behaviors surrounding smoking in Olmsted. County, Minnesota, we examined incident smoking events, smoking prevalence, cessation events, smoking relapse after cessation, and pharmaceutical cessation aid uptake for a regional Indigenous cohort compared to an age and sex-matched regional non-Indigenous cohort.

Study Design and Methods

This study was conducted with Institutional Review Board approval from the Mayo Clinic (#20–000642) and Olmsted Medical Center (#019-OMC-20).

Rochester Epidemiology Project

The Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) offers a unique opportunity to study longitudinal health behaviors via a multi-site record linkage system of multiple health care delivery sites and health systems, allowing an inclusive review of health data for residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota.12, 13 The REP was established in 1966 and represents a validated source of data for review.12, 14 Smoking has previously been studied in the context of the REP.15 The REP includes 99.9% of individuals in Olmsted County in the 2014 census estimates.13, 16 Length of time included in REP data varies by age and calendar year.13 For example, from census year 2000, median time in years in the system varied from a low of 2.7 years for those with an age over 90 years, to a high of 9.0 years for those between the ages of 60 and 69.13

Study cohort

All adult patients included in the REP with any record indicating an Indigenous (American Indian, Alaska Native, Native American, or First Nations) race or ethnicity from January 1st, 2006 through December 31, 2019, were included in the Indigenous cohort.14 Records defining race or ethnicity were patients’ self-reports, birth certificates, death certificates, children’s birth certificates, providers’ history, or flowsheet input. Patients under age 18 who reached age 18 at any time from January 1st, 2006 to December 31, 2019 were included in the study cohort. Due to the inclusive definitions used for patient recruitment, charts were identified with incorrect designations due to patient self-reporting. To recategorize non-Indigenous individuals, all charts were manually audited, and patients were removed if they required foreign language interpreter services or social history indicated birth history outside the North American continent. Patients were excluded if electronic retrieval followed by manual chart audit did not include smoking behaviors. Patients who exclusively used chewing tobacco, electronic cigarettes, or vaping devices but never cigarettes were excluded. Ceremonial tobacco use was not included in smoking data as this study is designed to review behaviors surrounding commercial tobacco products.17

Matched cohort

The Indigenous cohort was compared to a non-Indigenous age- and sex-matched cohort. Indigenous individuals were randomly matched to non-Indigenous individuals by sex and age (+/− five years) from the REP data in the incident year. Due to the variable presence of recorded smoking data for review, five non-Indigenous matches were generated for each Indigenous patient with a goal of identifying two matches with available smoking data. Matched individuals in the non-Indigenous cohort without available smoking data were excluded.

Defining Smoking Status:

Combustible tobacco product use including cigarettes, cigars, and pipes from REP records were considered valid if collected by a provider, documented in social history, identified in a flowsheet, or self-reported. A flowsheet is an electronic health record data input system with variable methods of data input. Input to a flowsheet may include data entered by nursing staff, auto entry from patient generated pre-visit questionnaires or electronic health record self-selection via patient facing portal entry, or direct input from a physician or advanced practice provider. For patients with an unknown tobacco status or three or more disagreements in data entry, such as those listed as former, current, or never smokers in the same year, a manual audit was completed to abstract smoking status (AR, YB, JF). The REP data quantifying smoking use was heterogenous. For example, depending on the healthcare system and year of data entry, nomenclature indicating active use of smoked tobacco products included “every day smoker,” “some days smoker,” “heavy tobacco smoker,” “light tobacco smoker,” or “active smoker.” To unify data for review given heterogeneity in the quantification of amount of smoked tobacco product consumption, any individuals with health data indicating any of the previously mentioned tobacco use terms were considered “current smokers” for the purposed of this study. Other categories of smoking behaviors identified in this study included former smoker, never smoker, and unknown. Former smokers were defined as individuals who were previously categorized as a current smoker with a subsequent record indicating former or never smoker. To be considered a former smoker, sustained cessation of 365 calendar days was required for this study. This duration of cessation was selected to identify individuals with cessation efforts that were likely to be sustained, as prior studies suggest long term cessation beyond one year is up to 95%.18, 19 Patients identified as former smokers remained this status unless a subsequent data entry status identified them again as a current smoker. If a patient’s smoking status was indicated as never smoker, or the health record indicated the patient response “no” to smoking, they were considered a never smoker. Patients were sorted into these groups from primary data retrieval and smoking status was defined in these terms for the duration of each calendar year for data available. The calendar year was defined as January 1st through December 31st. For patients with a single data point indicating smoking status with no subsequent data, their data were included in the estimation of prevalence but not incidence, relapse, or cessation. To verify the validity of the smoking definition algorithm, 13% of the study cohort was manually audited. If discrepant tobacco statuses were found during manual chart audits they were corrected per described methods.

Demographics and Socioeconomic Information:

Demographic data collected for each cohort included age, sex, education status, and living address closest to January 1st of the first year of available smoking data. Address information was collected to calculate the individual HOUsing-based index of SocioEconomic Status (HOUSES) index.20 The HOUSES index is a validated measure that uses property data (number of bedrooms, bathrooms, square footage, and estimated building size) to stratify an individual’s socioeconomic status (SES). The HOUSES index has been shown to predict a broad range of health outcomes for adults known to be inversely associated with SES, including acute disease, chronic disease, solid organ transplant outcomes, behavioral health outcomes including smoking, childhood diseases, and all-cause mortality.20–25 Each property feature corresponding to an individual’s address was standardized into a z-score and aggregated to a HOUSES overall z-score of the four items, with higher scores indicating higher socioeconomic status. HOUSES was standardized within the county, then the z-score of HOUSES was converted to HOUSES in quartiles.20, 26 Quartile 1 represents the lowest SES, and quartile 4 represents the highest.20

Definitions:

Prevalence was derived annually as the proportion of current smokers in each cohort divided by the total in the respective cohort for that year. Incidence was defined as the recorded first use of tobacco with no previous records indicating former tobacco use. A manual chart audit was completed to validate smoking incidence for both cohorts. Patients identified for review of incidence included any conversion of status from never smoker to either former smoker or current smoker. If previous records identified prior tobacco use, the smoking status used to identify the incident year was changed to reflect manually corrected smoking status. For a given patient there could only be one incident year. The incident events were defined as the proportion of never smokers from the previous year converting to former or current smokers. Cessation was defined as a current smoker transitioning to a former smoker, with rates defined as the proportion of current smokers who achieved cessation and was calculated annually. For a cessation event to be considered a valid cessation event, documentation of former tobacco use was required for a sustained time of greater than or equal to 365 days from last recorded use of tobacco. Although sustained cessation was required for the purposed of this study to define a cessation event, a relapse event was defined as a former smoker identified with any single recorded event indicating current tobacco use. Any recorded smoking relapse event was considered significant as prior studies indicate any smoking event after greater than one year of cessation is associated with return to previous smoking behaviors in 95% of individuals.27 To be reconsidered a former smoker again, cessation was defined according to the same criteria indicated above. The rate of relapse was defined as the proportion of former smokers who resumed smoking and was calculated annually. For a given patient there could be multiple relapse or cessation events over time. For the estimation of relapse and cessation events contiguous data for two or more years was required. Individuals with a single year of available data or non-contiguous data were only included in the estimation of prevalence and not incidence, relapse, or cessation estimations.

Pharmaceutical Cessation Aids:

Prescriptions generated for bupropion, varenicline, and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) were abstracted from the REP. Bupropion prescriptions generated for never and former smokers were not included in cessation aid data. Bupropion prescriptions generated for current smokers were manually audited to determine if a prescription was offered for depression or smoking cessation with the subsequent exclusion of prescriptions for depression. Charts of individuals classified as former or current smokers in both cohorts were audited to abstract uptake of over-the-counter NRT that was not collected on electronic prescription audit (JF, AR, YB).

Statistical Analysis:

Annual smoking prevalence over time was analyzed with a modified Poisson regression comparing the proportion of current smokers between the Indigenous cohort and matched cohort, adjusted for HOUSES index, age, and sex. Interaction terms were used to assess whether trends differed over time between cohorts. Cessation and relapse rates were evaluated using generalized estimating equations adjusted for age, sex, HOUSES index, and year with clustering at the patient level. Rates were calculated as the number of former and current smokers relative to the number of smokers and former smokers in the previous year, respectively. Incident events were analyzed as time-to-event data using the time from earliest smoking status to incidence via a Cox proportional hazard model. As it was hypothesized that younger subjects may be at higher risk of smoking incidence compared to older subjects, Cox proportional hazard regression was performed using participants’ age as the time scale. This method allowed us to group subjects of similar risk due to age together and permit for nonparametric age effects. Cumulative incidence of smoking was plotted accounting for the competing risk of death. A chi-square test of independence was utilized to compare smokers in the lowest HOUSES quartile and pharmaceutical uptake. All statistical analyses were completed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) or R, version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). P-values were considered significant ≤ 0.05.

Results:

Basic Characteristics

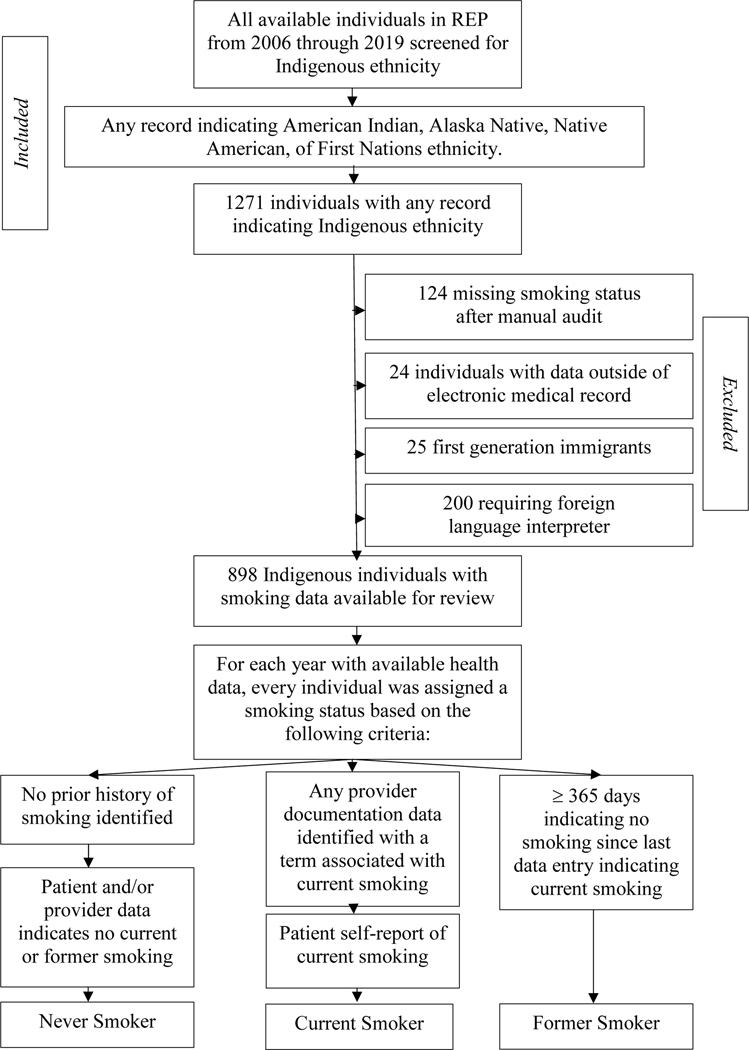

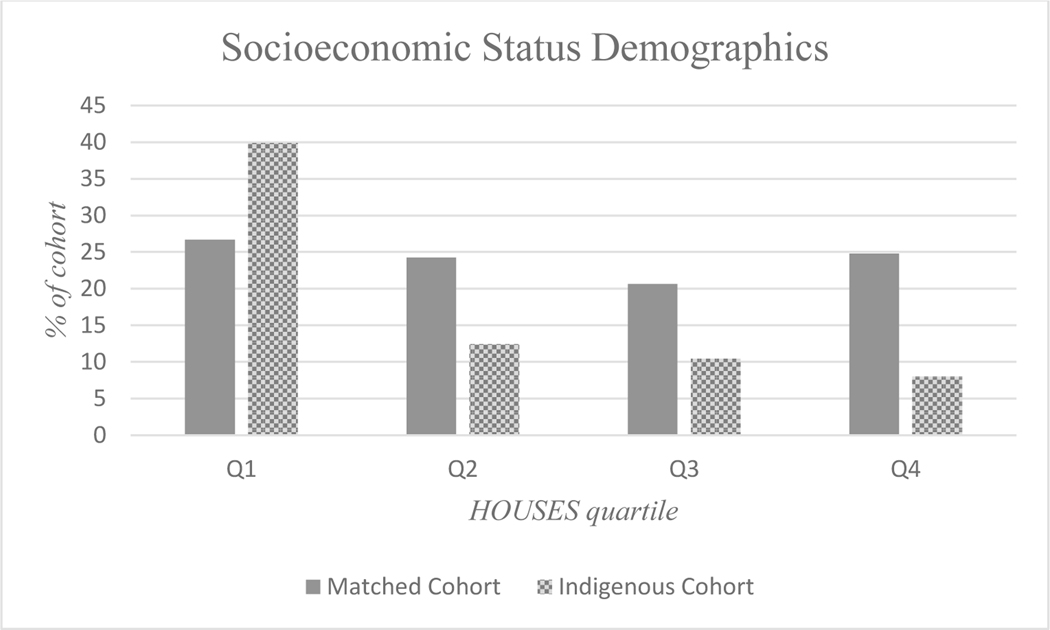

We screened 1037 patients for inclusion in the Indigenous cohort. After removing 124 individuals with missing smoking statuses, 24 individuals with missing electronic health record data, 25 first generation immigrants, and 200 individuals requiring a foreign language interpreter, 898 patients remained in the Indigenous cohort. Exclusion criteria for the study cohort can be found in Figure 1. Smoking data were found to be 95.0% accurate after the manual verification audit. At the start of the study (2006) the average age of the study cohort was 30.3 years (standard deviation 15.7 years). The study cohort consisted of 486 women (54.1%). Two matches for age and sex were identified for 881 individuals in the study cohort. For the remaining 18 patients, one match was identified. The final matched cohort consisted of 1780 individuals. Demographics of the study and matched cohorts can be found in Table 1. HOUSES data as a surrogate of SES was available for 764 individuals in the Indigenous cohort, and 1714 individuals in the matched cohort. A total of 39.9% of the Indigenous cohort was represented in quartile 1, the lowest quartile of SES, compared to 26.7% of the matched cohort (Chi-square statistic 102.5, P=<.001). HOUSES quartile distributions of both cohorts are represented in Figure 2. Education data was frequently missing and thus was not included in adjustments.

Figure 1:

Diagram outlining cohort inclusion and exclusion criteria, and subsequent criteria applied to defined smoking status.

Table 1:

Demographics of the Olmsted County, Minnesota Indigenous cohort and the sex and age matched non-Indigenous cohort. Age is represented at age of study beginning in 2006. Study end date was 2019. HOUSES data represents a geospatial indicator of housing-based socioeconomic index, with quartile 1 representing the lowest quartile of housing-based socioeconomic index and quartile 4 representing the highest quartile.

| Indigenous Cohort (N=898) | Match Cohort (N=1780) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, F, n (%) | 486 (54.1) | 960 (53.9) |

| Average age in years (SD) | 30.3 (15.7) | 31.2 (14.6) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 898 (100) | 0 (0) |

| White | 0 | 1483 (83.3) |

| Black/African American | 0 | 105 (5.9) |

| Asian | 0 | 96 (5.4) |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 | 4 (0.2) |

| Other/Mixed | 0 | 68 (3.8) |

| Refusal | 0 | 8 (0.4) |

| Unknown | 0 | 16 (0.9) |

| HOUSES data available | 764 | 1714 |

| HOUSES quartile 1 (%) | 358 (39.9) | 475 (26.7) |

| HOUSES quartile 2 (%) | 179 (12.5) | 432 (24.3) |

| HOUSES quartile 3 (%) | 131 (10.4) | 367 (20.6) |

| HOUSES quartile 4 (%) | 99 (8.0) | 441 (24.8) |

Figure 2:

Socioeconomic status represented by the individual HOUsing-based index of SocioEconomic Status (HOUSES) index for the Indigenous population in Olmsted County, Minnesota, and the sex and age matched non-Indigenous cohort in Olmsted County, Minnesota, from 2006 to 2019.

Smoking Prevalence

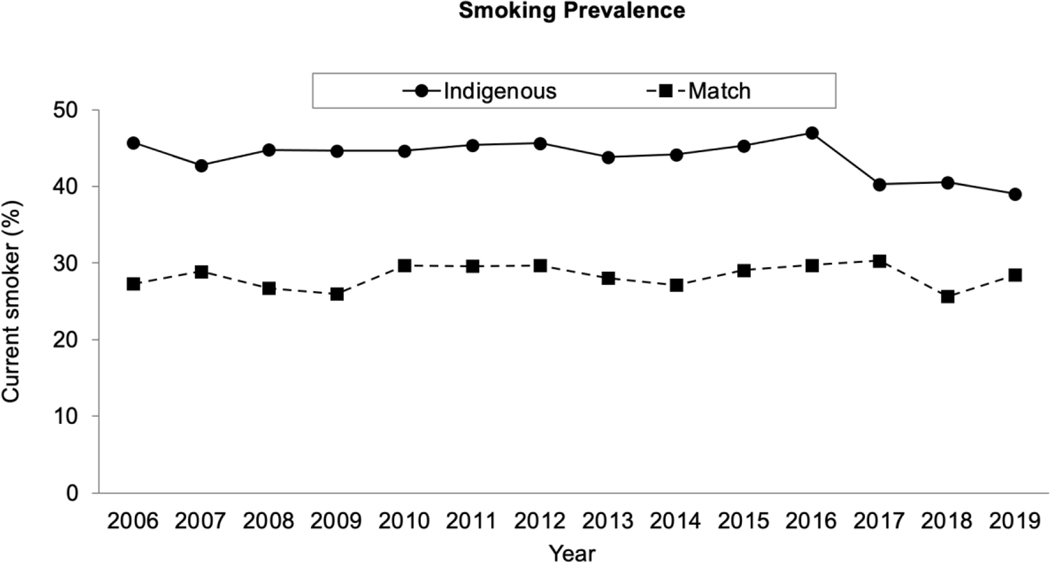

Smoking prevalence differed significantly, with higher smoking prevalence in the Indigenous cohort (yearly prevalence 39 to 47%) compared to the matched cohort (26 to 30%). Smoking prevalence over time is represented in Figure 3. Males were noted to have a higher smoking prevalence than females in the Indigenous cohort (P=<.001). The highest proportion of male current smokers was 57.8% in 2016, and a low of 36.8% in 2006. Over 50% of the current smokers in the Indigenous cohort were men from 2011 to 2016, and 2018 to 2019. Smoking prevalence remained independently associated with Indigenous race after adjustment for age and SES. Prevalence trends did not differ over time between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous cohort (interaction term, P=.17)

Figure 3:

Smoking prevalence comparing the Olmsted County, Minnesota Indigenous cohort and age and sex matched non-Indigenous cohort over time from 2006 to 2019.

Incident Events

Incident smoking events included 22 events identified in the Indigenous cohort and 69 in the matched cohort. The average age of first documented smoking event in the Indigenous cohort was 22.4 years, and 25.2 years in the matched cohort. The youngest age of smoking incidence in the Indigenous cohort was 15 years, and 14 years in the non-Indigenous cohort. Analysis with Cox proportional hazards regression revealed no significant difference in annual incidence events between the two cohorts (Hazard Ratio (HR): 1.06, 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 0.66–1.73, P=0.79). A post-hoc regression using participants’ age as the time scale similarly showed no significant difference in smoking incidence between the two cohorts (HR: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.57–1.55, P=0.81).

Smoking Cessation and Relapse

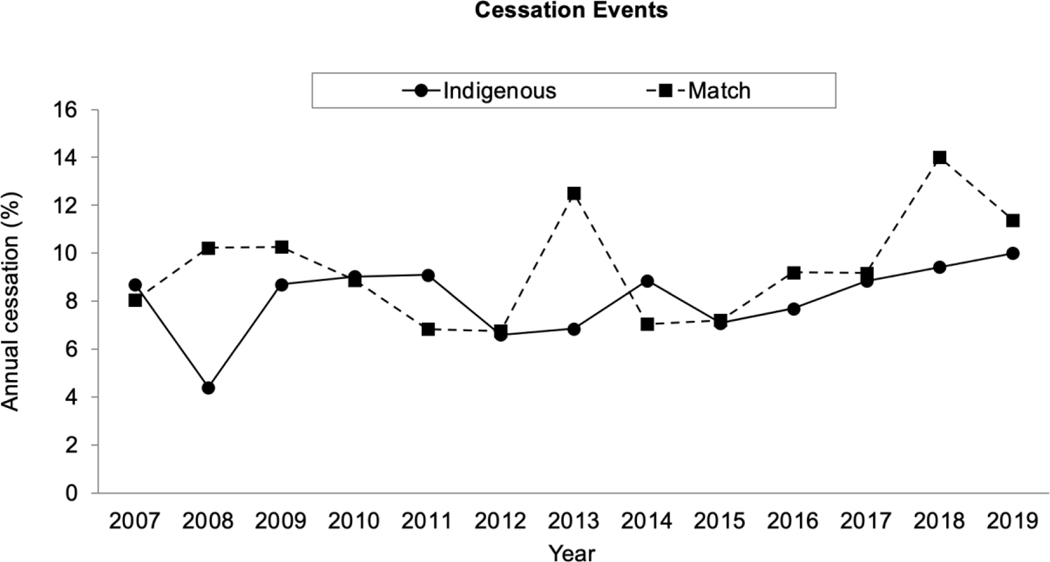

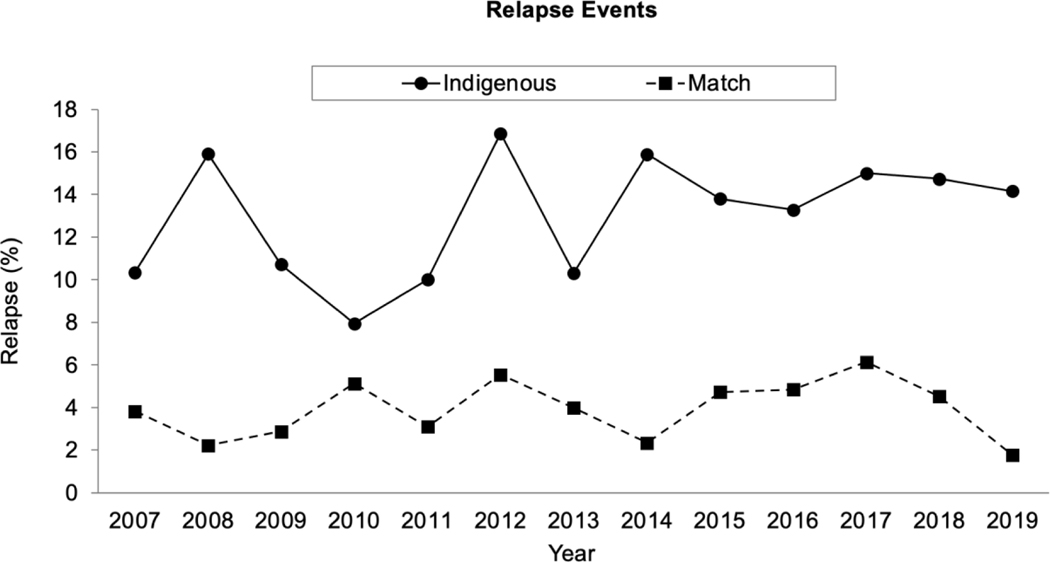

Smoking cessation in the Indigenous cohort was significantly higher than the matched cohort, with 193 cessation events identified in the Indigenous cohort and 248 cessation events identified in the matched cohort (RR: 1.10, 95% CI:1.06–1.13, P=<.001). Cessation events over time for both cohorts can be found in Figure 4. Annual relapse events were significantly higher in the Indigenous cohort, with 148 relapse events identified in the Indigenous cohort and 137 relapse events in the matched cohort (RR: 3.03, 95% CI:2.93–3.14, P=<.001). Relapse events over time are represented in Figure 5. Cessation and relapse events were both noted to decrease by calendar year (RR: 0.95,95% CI: 0.93–0.97, P=<.001 and RR 0.94, 95% CI: 0.92–0.96, P=<.001, respectively). Adjustment for age, sex, and SES did not change results. Indigenous people represented in quartile 1 of HOUSES Index were still more likely to achieve cessation compared to the matched cohort but were also more likely to relapse (P=<001).

Figure 4:

Cessation events represented as the proportion of current smokers achieving cessation annually comparing the Olmsted County, Minnesota Indigenous cohort and age and sex matched non- Indigenous cohort from 2006 to 2019.

Figure 5:

Relapse events represented as the proportion of former smokers resuming smoking annually comparing the Olmsted County, Minnesota Indigenous cohort and age and sex matched non- Indigenous cohort from 2006 to 2019.

Pharmaceutical Cessation Aid Uptake

In the Indigenous cohort, the proportion of ever smokers using any cessation aid was 35.8%. In the matched cohort, the proportion of ever smokers using any aid was 16.3%. Comparing the overall uptake of any pharmaceutical quit aid, the Indigenous cohort was more likely to use any aid (P=<.001). The proportion of ever smokers utilizing bupropion and NRT in the Indigenous cohort was significantly higher than the matched cohort (P=<.001). There was no difference between varenicline uptake in the proportion of ever smokers between the study cohort and control. These findings are represented in Table 2.

Table 2:

Pharmaceutical cessation aid uptake in the Olmsted County, Minnesota, Indigenous cohort and the age and sex matched non-Indigenous cohort. Each cohort is sorted by pharmaceutical agent compared with chi squared analysis at the 0.05 significance level.

| Indigenous Cohort | Match Cohort | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ever smokers, n, (% total cohort) | 584 (65.0) | 778 (43.7) | <.00001 |

| Any cessation aid, n, (% ever smokers) | 209 (35.8) | 127 (16.3) | <.00001 |

| Varenicline, n (% ever smokers) | 31(5.3) | 57 (7.3) | 0.39 |

| Nicotine Replacement, n (% ever smokers) | 151(25.9) | 87 (11.2) | <.00001 |

| Bupropion * , n (% ever smokers) | 94 (16.1) | 50 (6.4) | <.00001 |

Excluded patients prescribed bupropion for indications other than smoking cessation, including anxiety, depression or other mood disorder.

Discussion:

This study represents one of the only longitudinal descriptions of smoking behaviors in US Indigenous people compared to a matched regional cohort. The prevalence of smoking in our Indigenous cohort was higher than the non-Indigenous population, consistent with previous studies.1, 3 The annual smoking prevalence in this Indigenous population ranged from 39–47%, higher than CDC estimations of a 32% smoking prevalence1. To explain the high smoking prevalence among Indigenous people in Olmsted County, we considered three possible explanations, a higher smoking incidence, fewer cessation events, or more relapse events. Incident smoking events identified were low in both cohorts studied with no statistically significant differences. The Indigenous cohort demonstrates higher uptake of pharmaceutical quit aids and a higher smoking cessation rate compared to the non-Indigenous cohort. The most interesting finding of our study is the three-fold higher relapse rate amongst the Indigenous cohort compared to the non-Indigenous matched cohort. Prominent smoking prevalence in Indigenous populations has not been previously attributed to a higher rate of relapse. Therefore, smoking cessation maintenance may represent an attractive and novel target for addressing smoking prevalence in Indigenous populations.

The findings of our study contrast to prior works studying Indigenous utilization and awareness of smoking cessation resources. A prior survey described low awareness of pharmaceutical smoking cessation aids in a Kansas Indigenous population (N=998).28 Our study demonstrates the Olmsted County Indigenous population was able to obtain pharmaceutical cessation aids and quit smoking more effectively than the matched non-Indigenous cohort. Unfortunately, cessation efforts were outpaced by relapse once smoking cessation was achieved.

Causes of smoking relapse in Indigenous people have been explored in several scenarios, including pregnancy and secondhand smoke exposure. Psychosocial stress in the post-partum period in Alaska Native women has been described as a contributor to smoking relapse after cessation.29–32 Women cited anxiety, prior trauma, and parenting related stress as causes of smoking relapse.33–35 The presence of exposure to smoking either in the workplace or in the home has also been attributed to smoking relapse in Indigenous homes.36, 37 A survey of Native Americans in Minnesota revealed 40% of those surveyed were exposed to secondhand smoke at work.38 Decreased impulse control beyond three months of cessation was associated with resumption of smoking in a longitudinal study of the general population examining smoking relapse behaviors.39 Additional studies of smoking after cessation in non-Indigenous populations suggest other psychosocial comorbidities may influence resumption of smoking, such as concomitant use of cannabis, alcohol, or substance use recovery.40, 41 However, these studies were not conducted in Indigenous populations. The importance of studying contributory factors to smoking relapse in Indigenous populations is highlighted by a recent study conducted by Patten et al published in 2020. Although smoking is commonly described as a behavior associated with psychosocial stress and depression in the general population, this study reported Alaska Native women who smoked scored lower on stress and depression scales when compared non-smokers.42 Unique factors specific to Indigenous populations such as the cultural significance of tobacco and trauma from the impact of colonization are known to influence health outcomes across the spectrum of healthcare delivery.4, 43–48 Further study examining other factors contributing to smoking relapse after cessation in Indigenous North Americans could inform future prospective interventions.

The results of this study represent a novel window to address smoking prevalence by maintaining cessation, an intervention not widely described in the literature. There are numerous prospective studies attempting to address smoking prevalence in this population with smoking cessation programs, many of which do not reach statistical significance when attempting to address cessation as the primary outcome.49–52 In a randomized control trial comparing a culturally tailored smoking cessation intervention to an intervention without cultural tailoring the primary outcome of biochemically verified cessation was not achieved.49 The minimal success noted in such programs may be due to intervention promoting a suboptimal outcome. Our study demonstrates the Indigenous population in Olmsted County, Minnesota can access and utilize pharmaceutical cessation aids and effectively achieve smoking cessation. Further work should follow to examine the experience of Indigenous former smokers to examine risk factors and barriers to long-term cessation maintenance.

Strengths

There is a paucity of literature describing longitudinal smoking behaviors in Indigenous Americans. This study represents a large, inclusive cohort of Indigenous people. Utilizing any record indicating Indigenous race allowed inclusion of mixed-race individuals. Including mixedrace individuals in studies of Indigenous Americans is crucial, as definitions based on blood quantum are inherently flawed and exclude a large proportion of the Indigenous population.45, 53 Additionally, our study includes consideration of SES to limit confounding of findings that may be secondary to SES rather than race or ethnicity.46 The Olmsted County Indigenous population represents a blend of urban and rural Indigenous people, allowing a holistic review of a larger population. This study was conducted with involvement of the Mayo Clinic Center for Equity and Community Engagement Research, specifically the Native American Community Engagement Coordinator.

Limitations

There was no direct interaction by our research team with participants in this large, retrospective cohort study. We were unable to explore individual experiences surrounding smoking initiation, use of pharmaceutical quit aids, smoking cessation, or relapse behaviors. Furthermore, the complex interaction of individuals with the local community, background of historical trauma, and systematic racism were not assessed. Although we supplemented electronic retrieval with manual audits to verify accurate data capture, it is possible smoking data was not recorded accurately in clinical encounters. Additional limitations of this study include possible underrepresentation of former smokers. Individuals who quit smoking before study start date may have been represented as never smokers due to long periods of abstinence. Therefore, the relapse rate may be higher than reported in this study. Although uptake of NRT was audited, our study may underestimate NRT uptake if there was no documentation of over-the-counter products. Adjustment for depression and mood disorder was not included in this study. Although this study was not designed to assess the effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions, a limitation includes lack of information from quit lines or other online interventions. The estimation of incident smoking events in this population is likely underrepresented. Although individuals under age 18 were included in this study who reached age 18 at any time from 2006 to 2019, this study was not specifically designed to examine pediatric smoking behaviors.

Conclusion:

Smoking prevalence was significantly higher in Indigenous people compared to an age and sex matched cohort in Olmsted County, Minnesota due to a smoking relapse rate three times higher than the non-Indigenous cohort. Pharmaceutical uptake of bupropion and NRT were significantly higher in the Indigenous cohort compared to the matched non-Indigenous cohort. Risk factors for smoking relapse and barriers to maintaining cessation should be explored in future prospective studies.

Acknowledgements:

Guarantor statement:

The authors of this study take full responsibility for the results, analysis, and interpretation of findings out lined in the study, and all content outlined in the manuscript.

Role of sponsors:

the above sponsors provided funding but did not contribute to design or analysis.

Financial Statement

This study was supported by funding from the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Healthcare Delivery and the Rochester Epidemiology Project Scholarship. This study used the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) medical records-linkage system, which is supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA; AG 058738), by the Mayo Clinic Research Committee, and by fees paid annually by REP users. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Mayo Clinic, or the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of the Healthcare Delivery. Ann M. Rusk M.D. and Christopher C. Destephano, M.D., M.P.H. disclose funding from the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery. Dr. Rusk also discloses funding from the Rochester Epidemiology Project Scholarship. Alanna M. Chamberlain, Ph.D., Barbara A. Abbott, Cassie C. Kennedy, M.D., Christi A. Patten, Ph.D., and Chung-Il Wi, M.D., disclose funding from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Kennedy and Dr. Wi disclose funding from Mayo Funds. Dr. Kennedy also discloses funding from the Department of Defense. Dr.Wi also discloses funding from GlaxsoSmithKlein.

Abbreviations:

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control

- CI

Confidence Interval

- HR

Hazard Ratio

- NRT

Nicotine Replacement Therapy

- REP

Rochester Epidemiology Project

- SES

Socioeconomic status

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

Yvonne T. Bui and Jamie R. Felzer M.D., M.P.H have no disclosures to report.

Collaborators: Contributory study networks involved in the development of this manuscript include the Rochester Epidemiology Project, the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery, and the HOUSES project.

CRediT author statement:

Ann M. Rusk M.D: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, visualization, project administration, funding acquisition. Rachel E. Giblon, M.S.: methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing – review and editing. Alanna M. Chamberlain, Ph.D.: conceptualization, methodology, software, resources, writing – review and editing, supervision. Christi A. Patten, Ph.D.: conceptualization, methodology, software, resources, writing – review and editing, supervision. Jamie R. Felzer, M.D., M.P.H.: investigation, data curation, writing – review and editing. Yvonne T. Bui, B.S.: investigation, data curation, writing – review and editing. Chung-Il. Wi M.D: software, formal analysis, resources, writing – review and editing. Christopher C. Destephano, M.D., M.P.H: visualization, writing – review and editing. Barbara A. Abbott: data curation, writing – editing and review. Cassie C. Kennedy, M.D., F.C.C.P: conceptualization, methodology, software, resources, writing – review and editing, supervision.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. American Indians/Alaska Native and Tobacco Use. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tibuakuu M, Okunrintemi V, Jirru E, et al. National Trends in Cessation Counseling, Prescription Medication Use, and Associated Costs Among US Adult Cigarette Smokers. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e194585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United States Census. The American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2010. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mowery PD, Dube SR, Thorne SL, Garrett BE, Homa DM, Nez Henderson P. Disparities in Smoking-Related Mortality Among American Indians/Alaska Natives. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49:738–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brownson RC, Fielding JE, Maylahn CM. Evidence-based public health: a fundamental concept for public health practice. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:175–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steele CB, Cardinez CJ, Richardson LC, Tom-Orme L, Shaw KM. Surveillance for health behaviors of American Indians and Alaska Natives-findings from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2000–2006. Cancer. 2008;113:1131–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smylie J, Firestone M. Back to the basics: Identifying and addressing underlying challenges in achieving high quality and relevant health statistics for indigenous populations in Canada. Stat J IAOS. 2015;31:67–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Dakota People: Minnesota Historical Society; 2022.

- 9.United States Census Bureau Public Use Microdata Sample. Vol 20212019.

- 10.Minnesota Clean Indoor Air Act. Vol 2022. Minnesota Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olmsted County Smoke-Free Workplaces Ordinance. In: Ordinances OCCo, ed 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Melton LJ 3rd, History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:1202–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, Melton LJ 3rd, Rocca WA. Use of a medical records linkage system to enumerate a dynamic population over time: the Rochester epidemiology project. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:1059–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Finney Rutten LJ, et al. Rochester Epidemiology Project Data Exploration Portal. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:E42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Leibson CL, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, 3rd, Rocca WA. Generalizability of epidemiological findings and public health decisions: an illustration from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:151–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rocca WA, Grossardt BR, Brue SM, et al. Data Resource Profile: Expansion of the Rochester Epidemiology Project medical records-linkage system (E-REP). Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47:368–368j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boudreau G, Hernandez C, Hoffer D, et al. Why the World Will Never Be Tobacco-Free: Reframing “Tobacco Control” Into a Traditional Tobacco Movement. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:1188–1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilpin EA, Pierce JP, Farkas AJ. Duration of smoking abstinence and success in quitting. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:572–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krall EA, Garvey AJ, Garcia RI. Smoking relapse after 2 years of abstinence: findings from the VA Normative Aging Study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4:95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juhn YJ, Beebe TJ, Finnie DM, et al. Development and initial testing of a new socioeconomic status measure based on housing data. J Urban Health. 2011;88:933–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bang DW, Manemann SM, Gerber Y, et al. A novel socioeconomic measure using individual housing data in cardiovascular outcome research. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:11597–11615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barwise A, Wi CI, Frank R, et al. An Innovative Individual-Level Socioeconomic Measure Predicts Critical Care Outcomes in Older Adults: A Population-Based Study. J Intensive Care Med. 2021;36:828–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butterfield MC, Williams AR, Beebe T, et al. A two-county comparison of the HOUSES index on predicting self-rated health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:254–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stevens MA, Beebe TJ, Wi CI, Taler SJ, St Sauver JL, Juhn YJ. HOUSES Index as an Innovative Socioeconomic Measure Predicts Graft Failure Among Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplantation. 2020;104:2383–2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wi CI, Gauger J, Bachman M, et al. Role of individual-housing-based socioeconomic status measure in relation to smoking status among late adolescents with asthma. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26:455–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wi CI, St Sauver JL, Jacobson DJ, et al. Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status, and Health Disparities in a Mixed Rural-Urban US Community-Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:612–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garvey AJ, Bliss RE, Hitchcock JL, Heinold JW, Rosner B. Predictors of smoking relapse among self-quitters: a report from the Normative Aging Study. Addict Behav. 1992;17:367–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daley CM, Faseru B, Nazir N, et al. Influence of traditional tobacco use on smoking cessation among American Indians. Addiction. 2011;106:1003–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curtin SC, Matthews TJ. Smoking Prevalence and Cessation Before and During Pregnancy: Data From the Birth Certificate, 2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;65:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gould GS, Patten C, Glover M, Kira A, Jayasinghe H. Smoking in Pregnancy Among Indigenous Women in High-Income Countries: A Narrative Review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19:506–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Specker BL, Wey HE, Minett M, Beare TM. Pregnancy Survey of Smoking and Alcohol Use in South Dakota American Indian and White Mothers. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:8997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tong VT, England LJ, Dietz PM, Asare LA. Smoking patterns and use of cessation interventions during pregnancy. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patten CA, Koller KR, Flanagan CA, et al. Age of initiation of cigarette smoking and smokeless tobacco use among western Alaska Native people: Secondary analysis of the WATCH study. Addict Behav Rep. 2019;9:100143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patten CA, Koller KR, Flanagan CA, et al. Biomarker feedback intervention for smoking cessation among Alaska Native pregnant women: Randomized pilot study. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102:528–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Solomon LJ, Higgins ST, Heil SH, Badger GJ, Thomas CS, Bernstein IM. Predictors of postpartum relapse to smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90:224–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hyland A, Higbee C, Travers MJ, et al. Smoke-free homes and smoking cessation and relapse in a longitudinal population of adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:614–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fu SS, Burgess DJ, van Ryn M, et al. Smoking-cessation strategies for American Indians: should smoking-cessation treatment include a prescription for a complete home smoking ban? Am J Prev Med. 2010;39:S56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forster J, Poupart J, Rhodes K, et al. Cigarette Smoking Among Urban American Indian Adults - Hennepin and Ramsey Counties, Minnesota, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:534–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yong HH, Borland R, Cooper J, Cummings KM. Postquitting experiences and expectations of adult smokers and their association with subsequent relapse: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12 Suppl:S12–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quisenberry AJ, Pittman J, Goodwin RD, Bickel WK, D’Urso G, Sheffer CE. Smoking relapse risk is increased among individuals in recovery. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;202:93–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weinberger AH, Platt J, Copeland J, Goodwin RD. Is Cannabis Use Associated With Increased Risk of Cigarette Smoking Initiation, Persistence, and Relapse? Longitudinal Data From a Representative Sample of US Adults. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patten CA, Lando HA, Desnoyers CA, et al. Association of Tobacco Use During Pregnancy, Perceived Stress, and Depression Among Alaska Native Women Participants in the Healthy Pregnancies Project. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22:2104–2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cobb N, Espey D, King J. Health behaviors and risk factors among American Indians and Alaska Natives, 2000–2010. Am J Public Health. 2014;104 Suppl 3:S481–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crump AD, Etz K, Arroyo JA, Hemberger N, Srinivasan S. Accelerating and Strengthening Native American Health Research Through a Collaborative NIH Initiative. Prev Sci. 2020;21:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liebler CA. Counting America’s First Peoples. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2018;677:180–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Penman-Aguilar A, Talih M, Huang D, Moonesinghe R, Bouye K, Beckles G. Measurement of Health Disparities, Health Inequities, and Social Determinants of Health to Support the Advancement of Health Equity. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2016;22 Suppl 1:S33–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woodbury RB, Ketchum S, Hiratsuka VY, Spicer P. Health-Related Participatory Research in American Indian and Alaska Native Communities: A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang M, An Q, Yeh F, et al. Smoking-attributable mortality in American Indians: findings from the Strong Heart Study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2015;30:553–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choi WS, Beebe LA, Nazir N, et al. All Nations Breath of Life: A Randomized Trial of Smoking Cessation for American Indians. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51:743–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dignan MB, Jones K, Burhansstipanov L, et al. A randomized trial to reduce smoking among American Indians in South Dakota: The walking forward study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2019;81:28–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patten CA. Tobacco cessation intervention during pregnancy among Alaska Native women. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27:S86–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith SS, Rouse LM, Caskey M, et al. Culturally-Tailored Smoking Cessation for Adult American Indian Smokers: A Clinical Trial. Couns Psychol. 2014;42:852–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmidt RW. American Indian Identity and Blood Quantum in the 21st Century: A Critical Review. Journal of Anthropology. 2011;2011:549521. [Google Scholar]