Abstract

Research has found that individuals who were separated from parental care and experienced alternative care settings during childhood are more likely to have poor outcomes as adults. This highlights the importance of understanding factors that are related to resilience and well-being for care leavers. A growing body of research has supported the importance of spirituality in our understanding of resilience and well-being. However, little work to date has examined the relationship of spirituality to outcomes in care leavers. The current study investigated the relationships between spirituality, resilience, well-being, and health in a sample of 529 care leavers from 11 nations. It also examined how different themes of spirituality were related to specific outcome variables. Data revealed that spirituality was significantly associated with higher life satisfaction, better mental and physical health, and more resilience even when accounting for current age, gender, age at separation, Human Development Index scores, and childhood adversity. Furthermore, findings indicate that different themes of spirituality are related to specific outcome variables, even when accounting for demographic information. Findings indicate that spirituality may play an important role in resilience and well-being for care leavers. Implications and limitations are discussed.

Keywords: Spirituality, Resilience, Protective factors, Care leavers, Alternative care, Well-being

Global estimates indicate that millions of children and youth are separated from biological parental care during childhood (Desmond et al., 2020). These children and youth often reside in alternative care settings, including residential care centers or foster care (van IJzendoorn et al., 2020). Outcomes for adults who have transitioned out of care, or care leavers, are often poor (Bondi et al., 2020; McGuire et al., 2021). This has led to a robust literature focused on examining the role of factors associated with higher rates of resilience and better outcomes for this population (Refaeli, 2017). However, little research to date has specifically examined the possible relationship between spirituality and outcomes in this population. The present study investigated the relationship between spirituality and resilience, health, and well-being in a multinational sample of care leavers.

Literature Review

Care leavers are widely recognized as a vulnerable population (Berens & Nelson, 2015; Bondi et al., 2020; van Breda et al., 2020; Wilke et al., 2022). Research has consistently found that care leavers are more likely to have experienced high levels of adverse childhood experience (ACEs) and are at significantly greater risk for negative outcomes (Felitti et al., 1998; Simkiss, 2019). Berlin and colleagues (2011) found that care leavers were more likely to attempt suicide, abuse substances, and engage in criminal behavior. Other work has documented lower rates of post-secondary education, higher rates of unemployment or underemployment, and higher levels of poverty (Berejena Mhongera & Lombard, 2016; Dickens, 2018; Diraditsile & Nyadza, 2018). Furthermore, general early adversity has been linked to challenges with executive functioning (Lund et al., 2020), atypical behavioral development (Domoff et al., 2021; Howard et al., 2020; Ross et al., 2020; Wilke et al., 2020), and mental health concerns (Atluri et al., 2018; Pham et al., 2021). Taken together, care leavers are at higher risk for numerous negative outcomes. This increased risk has led to a robust literature focused on understanding factors that are related to resilience and well-being of care leavers (Refaeli, 2017).

Protective Factors

Despite the higher likelihood of negative outcomes for care leavers, some exhibit more resilience. Resilience is broadly defined as a person’s ability to bounce back when faced with negative life events and overcome obstacles (van Breda, 2018). Research has identified common factors that seem to support resilience and better outcomes in care leavers. Individual (i.e., self-efficacy, emotional regulation, social competency), relational (i.e. sense of belonging, relationships), and communal protective factors (i.e. faith and community traditions, education) interact to contribute to resilience and well-being in care leavers (Bhargava et al., 2018; Frimpong-Manso, 2018; Gilligan, 2001; Perera, 2018; Refaeli, 2017; Sulimani-Aidan, 2017). Recent conceptualizations of resilience emphasize the multidimensional nature of this construct, highlighting that it is dynamic (Masten, 2018; van Breda, 2018) and is the outcome of the interplay between risk and protective factors (Refaeli, 2017).

Spirituality

In recent years, spirituality has been identified as a factor that might be related to positive outcomes (Ager et al., 2015; Bryant-Davis & Wong, 2013). Though the terms spirituality, faith, and religiosity are discrete academic terms (Lunn, 2009), many researchers argue that the concepts themselves are interrelating and linked (Marler & Hadaway, 2002; Scott et al., 2018). Moreover, they are frequently used together (i.e., religion/spirituality) or interchangeably (i.e., religion or spirituality) in academic research. In line with previous work examining factors related to well-being (Makanui et al., 2019; Scott et al., 2018), the current study defined spirituality, religiosity, and faith in a broader sense to include belief systems, a relationship with a higher power, an individual’s sense of higher purpose, and spiritually based practices or behaviors. In other words, in the current research, the term spirituality will encompass religiosity, spirituality, and faith.

A growing body of research has supported the importance of spirituality in positive long-term outcomes (Bryant-Davis & Wong, 2013; Campbell & Bauer, 2021; Tuck & Anderson, 2014). Spirituality seems to serve as a factor that guides people through life challenges and functions as a pathway to resilience and maintaining well-being (Manning, 2014). Spirituality has been associated with happiness, well-being, and life satisfaction (Park et al., 2017). Trauma survivors have identified spirituality as a source of positivity, optimism, security, and meaning (Bryant-Davis & Wong, 2013; Milner et al., 2020). Taken together, this suggests that spirituality serves as an important factor that is associated with resilience in the face of adversity broadly. However, little work to date has specifically examined spirituality in the contexts of outcomes of adults with care experience.

The Present Study

The present study investigated the possible relationship between spirituality and well-being of care leavers. Spirituality was assessed by looking at spontaneous references to spirituality made while responding to a survey examining outcomes for care leavers. Specifically, the research team sought to examine whether life satisfaction, mental and physical health, and resilience differed by the number of spirituality references and if these differences varied by the number of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) care leavers reported. We hypothesized that care leavers with more spirituality references would report more life satisfaction, better mental and physical health, and higher levels of resilience. However, we further postulated that these differences would vary by the interaction between spirituality references and number of ACEs. Specifically, care leavers with more ACEs and spirituality references would report more life satisfaction, better mental and physical health, and higher levels of resilience than those that had more ACEs, but no spirituality references. Moreover, we hypothesized that these differences would be found even when accounting for current age, gender, age at separation from their biological parents, Human Development Index scores, and number of adverse childhood experiences. Furthermore, among care leavers who made spirituality references, we wished to explore if the presence of certain spirituality themes was associated with life satisfaction, mental and physical health, and resilience. As these analyses were exploratory in nature, we did not have specific hypotheses regarding which themes of spirituality would relate to individual well-being variables among adults with care experience.

Methods

Theoretical Framework

This study was conducted according to the Pragmatic Paradigm. The Pragmatic Paradigm is focused on what works in identifying evidence and often provides the foundation for investigation of complex social issues (Feilzer, 2010; Maarouf, 2019; Tashakkori et al., 1998). Research is driven by solving real-world problems (Frankel Pratt, 2016), and researchers are encouraged to include relationships and interactions between multiple factors in order to better reflect the complexity of reality (Sil & Katzenstein, 2010). In this study, this orientation led to using a mixed methods approach, often associated with the pragmatic paradigm (Morgan, 2014). Mixed methods created the opportunity to capture the broader framework offered by quantitative inquiry, as well as to understand the individual perceptions and experiences revealed by qualitative inquiry. Our detailed qualitative results have been published elsewhere (Wilke et al., In Press).

Study Context

Data presented here were collected as part of a larger initiative focused on healthy development in adults with care experience. All participants completed an online survey consisting of demographic items, 15 open-ended questions regarding their time in care, and several validated measures. The current sample is a subset of this larger research study. In order to ensure an accurate representation of the experience of care leavers, the current study only included participants who spent time in residential or foster care and whose nation of residence during childhood (i.e., the country where the separation from biological parents occurred) had 15 or more survey participants.

Participants

Participants were 529 care leavers who reported being separated from their biological parents during childhood for at least 6 months and placed in residential (78.8%) or foster care (35.3%). Some participants (14.2%) report being in both types of placements at some point during childhood. Approximately half (53.9%) of participants were male and ranged in age from 18 to 89 (M = 27.90; SD = 10.51). Table 1 includes participant demographic information. Participants reported residing in 11 nations during childhood (i.e., the nation in which they were separated from their biological parents). The most commonly reported nations of residence during childhood were India (n = 136), the USA (n = 101), Kenya (n = 94), Zimbabwe (n = 41), and Poland (n = 29). Frequencies, percentages, and Human Development Index (Roser, 2014) scores for nation of residence during childhood can be found in Table 2. Age at initial separation from biological parents ranged from 0 to 17 (M = 6.46; SD = 4.44). The most commonly reported reasons for the separation from biological parents were parental death (38.4%), abandonment/relinquishment (25.0%), and poverty (23.6%).

Table 1.

Frequency and percentage for demographic (n = 529)

| Category | Subcategory | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 244 | 46.1 |

| Male | 285 | 53.9 | |

| Education | Less than high school | 75 | 14.2 |

| High school diploma/equivalent | 163 | 30.8 | |

| Some college | 111 | 21.0 | |

| Associate degree/trade | 30 | 5.7 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 111 | 21.0 | |

| Graduate degree/professional | 39 | 7.3 | |

| Employment | Not working | 258 | 48.8 |

| Working | 271 | 51.2 | |

| Marital Status | Never married | 323 | 61.1 |

| Married | 111 | 21.0 | |

| Other | 95 | 17.9 | |

| Children | No | 391 | 73.9 |

| Yes | 138 | 26.1 |

Table 2.

Frequency, percentage, and Human Development Index for nation of residence during childhood (n = 529)

| Nation | n | % | HDI* |

|---|---|---|---|

| India | 136 | 25.7 | .645 |

| United States of America | 101 | 19.1 | .926 |

| Kenya | 94 | 17.8 | .601 |

| Zimbabwe | 41 | 7.8 | .571 |

| Uganda | 30 | 5.7 | .544 |

| Poland | 29 | 5.5 | .880 |

| Rwanda | 24 | 4.5 | .543 |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 22 | 4.2 | .543 |

| Ethiopia | 20 | 3.8 | .485 |

| Peru | 17 | 3.2 | .777 |

| Thailand | 15 | 2.8 | .777 |

*HDI Human Development Index

Measures

General Demographics

Participants answered a series of questions regarding their current age, nation of residence, gender, education, marital status, whether they have children, and employment status.

Care Experience Demographics

Participants were asked a series of questions regarding their experiences when separated from their biological parents. Items included nation of residence during childhood (i.e., where the separation occurred), age at initial separation, reason(s) for the separation, type(s) of placements, and total number of placements. Human Development Index (HDI; Roser, 2014) for nation of residence during childhood was included as a demographic variable. HDI, which includes life expectancy, education level, and per capita income, is a composite indicator of the average well-being of people in a specific nation. HDI for the nation of residence during childhood is of particular importance in the current study because it captures country level differences between participants.

Care Experience Survey

All participants completed a survey containing 15 open-ended questions regarding their experiences surrounding their separation from parental care. All items were included in the analysis for the current study included. Topics covered included participants’ perceptions of negative and positive impacts resulting from their time in care, supports and barriers to transitioning to adulthood, recommendations for care reform, and what they believed was the most important information for others to know about their experiences in care.

Spontaneous Spirituality References

It is important to note that there were no questions directly referencing spirituality in this study. Data includes spontaneous spirituality references made within the fifteen open-ended questions. For the purposes of this paper, spirituality is defined broadly and includes any support, behaviors, or beliefs linked to religious or spiritual beliefs or institutions, including but not limited to tangible support from religious organizations, personal prayers between an individual and a higher power, and specific group faith community rituals.

Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire

ACEs (Felitti et al., 1998) is a 10-item questionnaire regarding childhood maltreatment and family functioning. Participants evaluate whether they experienced each item (ex. Did you live with anyone who was a problem drinker or alcoholic or who used street drugs?). All items are summed for a total score, where higher scores indicate more adverse childhood experiences. The current sample yielded Cronbach’s alpha = 0.725.

Satisfaction with Life Scale

Life satisfaction was measured with the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985). In the scale, items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale with 1 indicating “strongly disagree” and 7 indicating “strongly agree,” where higher scores indicate more satisfaction with life (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.805).

Brief Resilience Scale

Resilience was measured using the Brief Resilience Scale (Smith et al., 2008), which included six items measuring resilience rated on a 5-point Likert scale with 1 indicating “strongly disagree” and 5 indicating “strongly agree.” A higher score on the Brief Resilience Scale indicates more resilience, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.717.

Physical and Mental Health

Physical and mental health were measured with the Short Form Health Survey (SF-12; Farivar et al., 2007; Gandek et al., 1998; Ware et al., 1996). Physical and mental health are assessed independently with scores ranging from 0 to 100. Higher scores indicate better mental and physical health (Cronbach’s alpha, physical = 0.841; mental = 0.821).

Translations

Survey instruments were available in English, Spanish, Hindi, Thai, and Bulgarian. Cross-cultural methodology guidelines proposed by Brislin (1980) were followed. This included two bilingual experts for each language, with at least one native speaker, conducting blind back-translations, educated translations, and translating survey questions and participant responses.

Procedure

The current research used a cross-sectional and retrospective survey design. Ethical approval was obtained from the author’s Institutional Review Board. Recruitment notices were posted on the website of a coalition connecting organizations serving vulnerable families, distributed through relevant professional networks that serve care leavers, and emailed to potential participants using professional networks’ distribution lists. The recruitment information was further disseminated via chain referral sampling. All measures were completed using an online survey platform. All participants provided informed consent before completing the survey and were free to end the survey at any time. Completion rate was 74.0%.

Results

Total number of ACEs, ACEs categories (less than four ACEs and four or more ACEs), total spirituality references, spirituality references group (none, one, and two or more references), and spirituality themes were independent variables (IVs). Dependent variables (DVs) in this study included life satisfaction, mental and physical health, and resilience. Demographic variables included current age, gender, HDI, and age at separation from parental care. Means and standard deviations for DVs and continuous demographic variables, as well as bivariate correlations between these variables, can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Correlations between DVs and demographic variables (n = 529)

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Life satisfaction | 20.13 | 7.11 | — | |||||||

| 2. Mental health | 44.88 | 8.95 | .53* | — | ||||||

| 3. Physical health | 49.83 | 6.64 | .29* | .32* | — | |||||

| 4. Resilience | 3.18 | .81 | .51* | .38* | .25* | — | ||||

| 5. Total ACEs | 4.35 | 2.61 | − .40* | − .39* | − .25* | − .28* | — | |||

| 6. Current age | 27.90 | 10.51 | − .50 | − .09* | − .12* | − .11* | .14* | — | ||

| 7. Separation age | 6.46 | 4.44 | .02 | .00 | .02 | − .03 | .01 | − .20* | — | |

| 8. HDI | .67 | .15 | .18* | − .03 | .00 | .02 | .07 | .33* | − .12* | — |

| 9. Total spirit refs | .92 | 1.63 | .15* | .13* | .12* | .16* | − .06 | .10* | − .06 | − .02 |

*p < .05

References to Spirituality

The 15 open-ended questions from the survey were examined using qualitative thematic data analysis. Two raters manually coded all open-ended questions and analyzed every question independently for references associated with faith, spirituality, and religion. A total of 494 spirituality-related references were identified. Most spirituality references were positive (93.8%) or neutral (5.8%). As the focus of the current study was on spirituality as a positive factor and the number of negative spirituality references were minimal (0.35%), negative references were excluded from analysis in this study. Total number of spirituality references ranged from 0 to 11 (M = 0.92; SD = 1.63). After examining the distribution of the total number of spirituality references, participants were grouped based on the number of spirituality references they made (none n = 324; 1 reference n = 92; 2 + references n = 113). The majority of participants did not make any spontaneous spirituality references (61.2%). However, a substantial number of participants made one (17.4%) or more (21.4%).

Each spirituality reference was further examined using qualitative thematic data analysis to investigate how care leavers were discussing spirituality. Themes within the references were clustered, and the researchers developed a directory of operational definitions and keywords corresponding to the major themes. A description of relationships between the themes and individual references was written and considered before drafting the final qualitative themes (see Table 4). Six spirituality themes emerged within the data: a personal relationship to God, spiritual community support, higher purpose, identity development, spirituality-based teachings and teachers, and spirituality-based servanthood. The detailed qualitative findings of the thematic analysis are reported elsewhere (See Wilke et al., In Press). For this manuscript, we will be focusing on the presence or absence of specific themes and how they relate to the resilience and well-being measures. The presence or absence of each spirituality theme was coded (0 = absent; 1 = present). Frequencies, percentages, and descriptions of each theme can be found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Frequencies, percentages, and descriptions of spirituality themes (n = 205)

| Theme | F | % | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship to God | 131 | 63.9 | The importance of a personal relationship with God and how this relationship empowered and supported the participants. Included how they felt the supportive presence of God, that they felt listened to and connected with God, and that their spiritual relationship with God was transformative in their lives |

| Spiritual support | 79 | 38.5 | The impact of spiritual communities in their lives. Included the value of social and emotional support from congregation members, spiritual leaders, and studying spiritual scriptures |

| Higher purpose | 57 | 27.8 | Finding a sense of higher purpose in their spirituality and relationships to God. This included a belief that God had a specific, designed purpose for them or someone close to them, and that their experienced adversity would serve a higher purpose |

| Spiritual teachings/teachers | 50 | 24.4 | The importance of the role of spiritual instruction and spiritual instructors. Included many kinds of spiritual instruction (i.e., reading religious text) or learning from an different of spiritual instructors (i.e., listening to priests) |

| Spiritual identity development | 46 | 22.4 | The idea that spirituality was a core component of their identity. Included notions of “finding themselves” and defining their adult identities within the context of their spirituality, positively developing identities through a relationship with God, and centering identity around spirituality |

| Spirituality-based servanthood | 35 | 14.6 | Value of spirituality-based servanthood as a motivator to serve others or to serve God by serving others. Included evangelistic undertones, such as being motivated to serve others in order to encourage that individual toward faith/religion/spirituality |

Relationship Between DVs, Spirituality References, and ACEs

Pearson’s correlations were conducted to examine the possible relationship between total number of spirituality references, total number of ACEs, and DVs among care leavers (see Table 3). The total number of ACEs was significantly negatively correlated with life satisfaction, mental health, physical health, and resilience. As the number of ACEs increased among care leavers, measures of well-being decreased. Furthermore, the total number of spirituality references was significantly positively correlated with life satisfaction, mental health, physical health, and resilience. In other words, as the number of spirituality references increased among adults with care experience, so did well-being measures. Total number of spirituality references was not significantly correlated to the total number of ACEs.

To better understand the possible relationship between spirituality references, ACEs, and the DVs among care leavers, a multivariate analysis of covariances (MANCOVAs) was conducted. Total number of spirituality references was coded into three categories: no spirituality references (n = 324), one spirituality reference (n = 92), and two or more spirituality references (n = 113). In order to better examine the ACEs by spirituality reference interactions, the total number of ACEs was coded into two categories: less than four ACEs (n = 188) and four or more ACEs (n = 341). Spirituality reference categories (no references, one reference, and two or more references) and ACEs categories (less than four and four or more) were IVs. Life satisfaction, mental and physical health, and resilience were DVs. Current age, age at separation, and HDI of nation of residence during childhood were included as covariates. For the covariates, results of the multivariate analysis were significant for HDI, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.935, p < 0.01. Findings indicated that life satisfaction differed by HDI of nation of residence during childhood, F (1, 529) = 23.98, p < 0.01, ŋ2 = 0.044. Care leavers who resided in nations with higher HDIs during childhood had more satisfaction with life.

Means and standard deviations for each DV by number of spirituality references categories and ACEs categories can be found in Table 5. The multivariate effect was significant for the spirituality references categories, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.936, p < 0.01. Data revealed that the number of spirituality references was significantly related to satisfaction with life, F (1, 529) = 6.14, p < 0.01, ŋ2 = 0.023; mental health, F (1, 529) = 4.12, p < 0.01, ŋ2 = 0.016; physical health, F (1, 529) = 3.01, p < 0.01, ŋ2 = 0.011; and resilience, F (1, 529) = 9.14, p < 0.01, ŋ2 = 0.034. For life satisfaction, care leavers who made two or more spirituality references (M = 22.55; SD = 6.83) reported significantly higher life satisfaction than those who had no spirituality references (M = 19.57; SD = 7.14) or one spirituality reference (M = 19.14; SD = 6.75). For mental health, adults with care experience with one (M = 46.81; SD = 8.54) or two or more (M = 46.51; SD = 8.24) spirituality references reported significantly better mental health than those with no spirituality references (M = 43.77; SD = 9.14). In terms of physical health, results indicated that care leavers with two or more spirituality references (M = 52.08; SD = 7.26) reported significantly better physical health than those who made no spirituality references (M = 49.10; SD = 8.85) or one spirituality reference (M = 49.67; SD = 9.06). Finally, the data showed that participants who made two or more spirituality references (M = 3.46; SD = 0.83) reported significantly more resilience than those who had no spirituality references (M = 3.11; SD = 0.77) or one spirituality reference (M = 3.11; SD = 0.85). Taken together, findings suggest that care leavers who made two or more spirituality references reported better well-being than those made no spirituality references.

Table 5.

Results for the dependent variables by spirituality reference group and ACEs category: descriptives (means and standard deviations) and MANCOVA results (F-values (partial η2)

| < 4 ACEs | 4 + ACEs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | M | SD | M | SD | SR (η2p) | ACE (η2p) | Interaction (η2p) |

| Life satisfaction | 6.14 (.02)* | 12.97 (.02)* | 10.28 (.04)* | ||||

| 0 Refs | 23.49 | 5.61 | 17.60 | 7.05 | |||

| 1 Ref | 20.22 | 6.74 | 18.69 | 6.75 | |||

| 2 + Refs | 22.63 | 7.14 | 22.54 | 6.62 | |||

| Mental health | 4.12 (.02)* | 11.74 (.02)* | 2.77 (.01) | ||||

| 0 Refs | 47.31 | 8.15 | 41.94 | 9.10 | |||

| 1 Ref | 48.92 | 6.95 | 45.94 | 9.10 | |||

| 2 + Refs | 47.07 | 8.16 | 46.05 | 8.34 | |||

| Physical health | 3.01 (.01)* | 4.08 (.01)* | 8.02 (.03)* | ||||

| 0 Refs | 53.08 | 6.60 | 47.07 | 9.18 | |||

| 1 Ref | 49.45 | 9.30 | 49.76 | 9.02 | |||

| 2 + Refs | 51.94 | 7.62 | 52.19 | 7.62 | |||

| Resilience | 9.14 (.03)* | .01 (.00) | 8.62 (.03)* | ||||

| 0 Refs | 3.34 | .60 | 2.99 | .82 | |||

| 1 Ref | 2.76 | .89 | 3.26 | .80 | |||

| 2 + Refs | 3.53 | .77 | 3.40 | .82 | |||

*p < .05

The multivariate effect was also significant for the ACE categories, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.955, p < 0.01. Data revealed that ACE categories were significantly related to satisfaction with life, F (1, 529) = 12.97, p < 0.01, ŋ2 = 0.024; mental health, F (1, 529) = 11.74, p < 0.01, ŋ2 = 0.022; and physical health, F (1, 529) = 4.08, p < 0.01, ŋ2 = 0.008. Data revealed that adults with care experience with four or more ACEs reported significantly lower life satisfaction (4 + M = 18.70; SD = 7.14; > 4 M = 22.73; SD = 6.29) and poorer mental (4 + M = 43.45; SD = 9.14; > 4 M = 47.48; SD = 7.98) and physical health (4 + M = 48.50; SD = 9.00; > 4 M = 52.25; SD = 7.38). Resilience was not significant for the ACE categories.

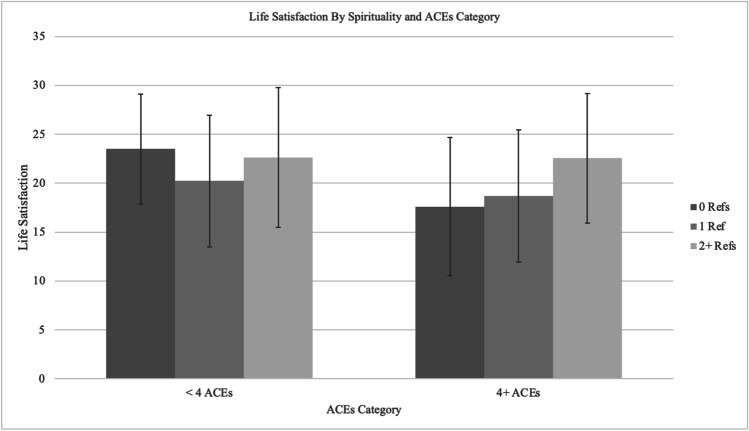

The multivariate effect was significant for the interaction between spirituality reference categories and ACE categories, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.923, p < 0.01. Data revealed that the interaction was significantly related to satisfaction with life, F (1, 529) = 10.27, p < 0.01, ŋ2 = 0.038; physical health, F (1, 529) = 8.02, p < 0.01, ŋ2 = 0.030; and resilience, F (1, 529) = 8.62, p < 0.01, ŋ2 = 0.032. As can be seen in Fig. 1, care leavers who reported less than four ACEs differed by spirituality references categories for life satisfaction. Those who reported less than four ACEs and made one spirituality reference (M = 20.22; SD = 6.74) reported significantly lower life satisfaction than those who made no references (M = 23.49; SD = 5.61) or two or more references (M = 22.63; SD = 7.14). However, participants who reported four or more ACEs significantly differed by spirituality references categories for life satisfaction. Specifically, care leavers who had four or more ACEs and made two or more spirituality references (M = 22.54; SD = 6.62) reported significantly higher life satisfaction than those who made no spirituality references (M = 17.60; SD = 7.05) or one spirituality reference (M = 18.69; SD = 6.75).

Fig. 1.

The interaction between ACE category and spirituality reference category for life satisfaction

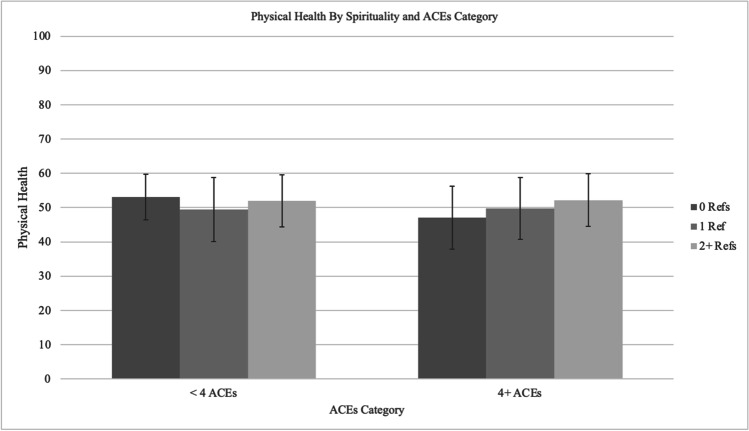

Figure 2 shows the ACE category by spirituality reference category interaction for physical health among care leavers. Participants who reported less than four ACEs did not differ by spirituality reference categories for physical health. Data suggested that participants who reported four or more ACEs significantly differed by spirituality references categories for physical health. Specifically, care leavers who had four or more ACEs and made one (M = 49.76; SD = 9.02) or two or more (M = 52.19; SD = 7.62) spirituality references reported significantly better physical health than those who made no spirituality references (M = 47.07; SD = 9.18).

Fig. 2.

The interaction between ACE category and spirituality reference category for physical health

Figure 3 shows the ACE category by spirituality reference category interaction for resilience for care leavers. Individuals who reported less than four ACEs and made one spirituality reference (M = 2.76; SD = 0.89) reported significantly lower resilience than those who made no references (M = 3.34; SD = 0.60) or two or more references (M = 3.53; SD = 0.77). Moreover, data revealed that participants who reported four or more ACEs significantly differed by spirituality references categories for resilience. Care leavers who had four or more ACEs and made one (M = 3.26; SD = 0.80) or two or more (M = 3.40; SD = 0.82) spirituality references reported significantly more resilience than those who made no spirituality references (M = 2.99; SD = 0.82). Mental health was not significant for the interaction of spirituality references categories and ACE categories.

Fig. 3.

The interaction between ACE category and spirituality reference category for resilience

Themes Associated with Well-being Among Those Who Made Spirituality References

We also wanted to examine if the presence of certain spirituality themes was associated with life satisfaction, mental and physical health, and resilience among care leavers. Only data from participants who made spirituality references were included in the current analyses (n = 205). Multiple regression models were used in order to determine if spirituality themes (relationship to God, spiritual community support, higher purpose, identity development, spirituality-based teachings and teachers, and spirituality-based servanthood) and demographic variables were related to life satisfaction, mental and physical health, and resilience. Multiple regression analysis is used with continuous dependent variables and categorical or continuous independent variables. Continuous variables included current age, age at separation from biological parents, HDI of the nation of residence during childhood, total ACEs, and total spirituality references. As categorical variables cannot be entered directly into a regression model and be meaningfully interpreted (Cohen, 1983), dummy variables were used in the regression equation. Categorical variables in the current regression equation included gender (0 = female; 1 = male) and spirituality themes (relationship to God, spiritual community support, higher purpose, spiritual identity development, spirituality-based teachings and teachers, and spirituality-based servanthood; 0 = absent; 1 = present).

The multiple linear regression model for life satisfaction with the predictors of current age, age at separation, gender, total ACEs, HDI of nation of residence during childhood, and spirituality themes was significant, F (7, 205) = 5.05, p < 0.001, and explained 24.0% of the variance (R2 = 0.240). As can be seen in Table 6, age at separation from parental care (Beta = 0.156, p < 0.05), HDI of the participants’ nation of residence during childhood (Beta = 0.384, p < 0.001), ACEs (Beta = − 0.192, p < 0.01), relationship to God (Beta = 0.193, p < 0.05), and spirituality-based teachings and teachers (Beta = 0.178, p < 0.05) were related to life satisfaction. Participants who were older when separated from parental care and those who lived in a nation with a higher HDI during childhood had higher life satisfaction. Those who had more ACEs had lower life satisfaction. Furthermore, care leavers who had spirituality themes regarding relationship to God and spirituality-based teachings and teachers had higher life satisfaction than those who did not. Data did not reveal significant differences for those who made other types of spirituality references.

Table 6.

Summary of linear regression for life satisfaction from type of spirituality references and demographics (n = 205)

| Variable | Unstandardized coefficients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | p | ||

| Current age | − .05 | .04 | − .093 | − 1.29 | .200 |

| Age at separation | .25 | .11 | .156 | 2.32 | .022* |

| Male | .06 | .95 | .004 | .06 | .951 |

| HDI | 15.65 | 3.10 | .384 | 5.05 | < .001* |

| ACEs | − .57 | .19 | − .192 | − 2.97 | .003* |

| Total spirituality ref | .06 | .37 | .016 | .17 | .868 |

| Relationship to God | 2.81 | 1.15 | .193 | 2.44 | .016* |

| Spiritual support | .88 | 1.09 | .061 | .80 | .423 |

| Higher purpose | − 1.01 | 1.16 | − .061 | − .87 | .386 |

| Spiritual teachings | 3.01 | 1.26 | .178 | 2.38 | .018* |

| Spiritual identity | .08 | 1.23 | .004 | .06 | .949 |

| Servanthood | 1.08 | 1.46 | .050 | .74 | .463 |

*p < .05

The multiple linear regression model predicting mental health from current age, age at separation, gender, total ACEs, HDI of nation of residence during childhood, and type of spirituality references was significant, F (7, 205) = 2.96, p < 0.001, and explained 15.6% of the variance (R2 = 0.156). As can be seen in Table 7, age at separation from parental care (Beta = 0.144, p < 0.05), HDI of the participants’ nation of residence during childhood (Beta = 0.289, p < 0.001), ACEs (Beta = − 0.211, p < 0.01), and relationship to God (Beta = 0.202, p < 0.05) were associated with mental health. Participants who were older when separated from parental care and those who lived in a nation with a higher HDI during childhood reported better mental health. Those who had more ACEs reported poorer mental health. Furthermore, care leavers who had spirituality themes about their relationship to God reported better mental health than those who did not. Data did not reveal significant differences for those who made other types of spirituality references.

Table 7.

Summary of linear regression for mental health from type of spirituality references and demographics (n = 205)

| Variable | Unstandardized coefficients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | p | ||

| Current age | − .02 | .05 | − .028 | − .37 | .711 |

| Age at separation | .27 | .13 | .144 | 2.02 | .044* |

| Male | − .48 | 1.19 | − .028 | − .40 | .689 |

| HDI | 14.04 | 3.90 | .289 | 3.60 | < .001* |

| ACEs | − .75 | .24 | − .211 | − 3.10 | .002* |

| Total spirituality Refs | − .26 | .46 | − .059 | − .57 | .567 |

| Relationship to God | 3.51 | 1.45 | .202 | 2.43 | .016* |

| Spiritual support | .12 | 1.38 | .007 | .09 | .928 |

| Higher purpose | − .85 | 1.46 | − .043 | − .58 | .565 |

| Spiritual teachings | 1.40 | 1.59 | .069 | .88 | .380 |

| Spiritual identity | − 1.26 | 1.55 | − .057 | − .81 | .418 |

| Servanthood | − .82 | 1.84 | − .032 | − .45 | .656 |

*p < .05

The multiple linear regression model for physical health with the predictors of current age, age at separation, gender, total ACEs, HDI of nation of residence during childhood, and type of spirituality references was significant, F (7, 205) = 2.81, p < 0.001, and explained 15.0% of the variance (R2 = 0.150). As can be seen in Table 8, current age (Beta = − 0.160, p < 0.05), age at separation from parental care (Beta = 0.147, p < 0.05), ACEs (Beta = − 0.171, p < 0.05), spiritual community support (Beta = 0.224, p < 0.01), and spiritual identity development (Beta = 0.160, p < 0.05) were related to physical health. Participants who were older when separated from parental care and those who lived in a nation with a higher HDI during childhood reported better physical health. Those who were older and had more ACEs reported poorer physical health. Furthermore, adults with care experience whose spirituality themes related to spiritual community support and spiritual identity development reported better physical health than those who did not. Data did not reveal significant differences for those who made other types of spirituality references.

Table 8.

Summary of linear regression for physical health from type of spirituality references and demographics (n = 205)

| Variable | Unstandardized coefficients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | p | ||

| Current age | − .10 | .05 | − .160 | − 2.10 | .037* |

| Age at separation | .27 | .13 | .147 | 2.06 | .041* |

| Male | − 1.03 | 1.17 | − .063 | − .88 | .381 |

| HDI | 5.41 | 3.83 | .114 | 1.41 | .160 |

| ACEs | − .60 | .24 | − .171 | − 2.50 | .013* |

| Total spirituality Refs | .00 | .45 | .000 | .00 | .998 |

| Relationship to God | 1.14 | 1.42 | .067 | .81 | .422 |

| Spiritual support | 3.76 | 1.35 | .224 | 2.78 | .006* |

| Higher purpose | .69 | 1.44 | .035 | .48 | .633 |

| Spiritual teachings | − .07 | 1.56 | − .003 | − .04 | .967 |

| Spiritual identity | 3.48 | 1.52 | .160 | 2.28 | .024* |

| Servanthood | .19 | 1.81 | .008 | .11 | .914 |

*p < .05

The multiple linear regression model predicting resilience from current age, age at separation, gender, total ACEs, HDI of nation of residence during childhood, and type of spirituality references was significant, F (7, 205) = 2.55, p < 0.01, and explained 13.7% of the variance (R2 = 0.137). As can be seen in Table 9, current age (Beta = − 0.173, p < 0.05), relationship to God (Beta = 0.295, p < 0.001), spiritual community support (Beta = 0.170, p < 0.05), higher purpose (Beta = 0.193, p < 0.01), and spirituality-based teachings and teachers (Beta = 0.171, p < 0.05) were associated with resilience. Participants who were older had lower resilience. Furthermore, care leavers whose spirituality themes included references to their relationship to God, spiritual community support, having a higher purpose, and spirituality-based teachings and teachers reported more resilience than those who did not. Data did not reveal significant differences for those who made other types of spirituality references.

Table 9.

Summary of linear regression for resilience from type of spirituality references and demographics (n = 205)

| Variable | Unstandardized coefficients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | p | ||

| Current age | − .01 | .01 | − .173 | − 2.25 | .026* |

| Age at separation | .00 | .01 | .019 | .27 | .787 |

| Male | − .05 | .12 | − .028 | − .38 | .702 |

| HDI | .36 | .40 | .072 | .89 | .372 |

| ACEs | .00 | .03 | .006 | .08 | .933 |

| Total spirit Refs | − .04 | .05 | − .081 | − .78 | .436 |

| Relationship to God | .52 | .15 | .295 | 3.50 | < .001* |

| Spiritual support | .30 | .14 | .170 | 2.09 | .038* |

| Higher purpose | .39 | .15 | .193 | 2.58 | .011* |

| Spiritual teachings | .35 | .16 | .171 | 2.15 | .033* |

| Spiritual identity | .00 | .16 | .000 | .01 | .995 |

| Servanthood | .23 | .19 | .088 | 1.21 | .228 |

*p < .05

Discussion

The goal of the current study was to examine the possible relationships between spirituality, resilience, health, and well-being in a sample of adults with care leavers. Specifically, this research investigated whether care leavers who made more spirituality references reported higher levels of life satisfaction, mental and physical health, and resilience than those that made fewer spirituality references. Furthermore, we examined whether differences in resilience and well-being variables among care leavers would vary by the interaction between spirituality references and number of ACEs. We also wished to explore spirituality themes associated with life satisfaction, mental and physical health, and resilience among adults with care experience. Data revealed that spirituality played an important role in well-being for care leavers. In line with our hypotheses, findings suggest that participants with two or more spirituality references had significantly higher life satisfaction, better mental and physical health, and higher resilience than those that did not make spirituality references, even when accounting for current age, age at separation, gender, HDI, and childhood adversity. Overall, these findings indicate that the individuals who made more spirituality references reported higher levels of well-being and resilience. Moreover, we found that there was a significant interaction for ACEs and spirituality references for life satisfaction, physical health, and resilience. Care leavers who experienced higher rates of ACEs and had more spirituality references reported significantly higher life satisfaction, better physical health, and more resilience than those who had high rates of ACEs and fewer spirituality references.

When specifically examining data for care leavers that made spirituality references, findings indicate that specific spirituality themes were associated with different well-being variables. Life satisfaction was related to references to a relationship with God and spiritual teachings/teachers. Mental health was only associated with references to a relationship with God. By contrast, physical health was found to relate to references to spiritual support and spiritual identity. Finally, resilience was associated with references to relationship to God, spiritual support, having a higher purpose, and spiritual teachings/teachers. Interestingly, the total number of spirituality references was not associated with any of the resilience and well-being variables.

Findings from the current study are consistent with previous research on other vulnerable populations that suggests that spirituality has a positive association on well-being (Bryant-Davis & Wong, 2013; Campbell & Bauer, 2021; Park et al., 2017; Tuck & Anderson, 2014). Relationship to God has been demonstrated as a source of strength for children in foster care (Jackson et al., 2010) and a key support for survivors of intimate partner violence (Drumm et al., 2013). Spiritual teachings and pastoral care were highlighted as a vital support for natural disaster survivors (Alawiyah et al., 2011). A scoping review of faith and resilience showed spiritual community support to be an important factor in positive outcomes (Campbell & Bauer, 2021). Other research has shown spiritual community support to be valuable in humanitarian crises (Ager et al., 2015), during the COVID-19 pandemic (Wilke & Howard, 2021), and among internally displaced persons (Parsitau, 2011). The development of a spiritual identity has been found to be important for those with chronic physical conditions (Faull & Hills, 2006). Research on redemptive narratives aligns with the findings of this study that indicate a higher purpose or meaning for adversity can be an important factor in supporting positive outcomes (Russell, 2020). Further research has shown using faith for meaning making to resilience in times of adversity or when experiencing major negative life events (Glenn, 2014; Koenig, 2006; Ögtem-Young, 2018).

Though directionality cannot be inferred in the current study, our findings support the possibility that spirituality could serve as a protective factor that can potentially support care leavers through life challenges and function as a pathway to resilience and maintaining well-being.

Implications for Practice

The documented risks of having care experience are substantial and varied (Berlin et al., 2011; Felitti et al., 1998; Simkiss, 2019). Not only does the higher risk of negative outcomes impact the individual, but also families, communities, and systems more broadly. However, it is clear that some care leavers experience positive outcomes and greater resilience in the face of tremendous adversity. As such, identifying supports or potential protective factors to support resilience and better outcomes is a critical contribution to both research and practice. Indeed, this has become a recent research focus (Bhargava et al., 2018; Frimpong-Manso, 2018; Perera, 2018; Refaeli, 2017; Sulimani-Aidan, 2017). To date, social relationships, financial support, social environment, access to services, peer support, personal factors, and more (Bryant-Davis & Wong, 2013; Frimpong-Manso, 2018; Scott et al., 2022; Sulimani-Aidan & Melkman, 2018; van Breda & Dickens, 2017) have been shown to support better outcomes in this population. However, to our knowledge, no other studies have examined relationship between spirituality and health, well-being, and resilience for care leavers.

Although the findings of this study are preliminary in nature and require further research to confirm, they would be in line with other studies showing benefit from spirituality as relates to well-being (Ager et al., 2015; Bryant-Davis & Wong, 2013) and even spirituality as a source of support in the face of adversity (Bryant-Davis & Wong, 2013; Milner et al., 2020). As such, there are some important implications for practice. Spirituality should be considered a potentially valuable contributing factor to health, resilience, and well-being. Although spirituality is a personal choice and should never be a point of coercion, practitioners should allow the practice of desired spiritual practices and facilitate access to such practices. Supporting the types of spiritual themes outlined in this study would require low investments of time, money and other resources, and may be a valuable contribution available to even very low-resource environments. Therefore, facilitating access to spiritual practices may be one more tool practitioners that can be used to support health, resilience, and well-being in care leavers.

Limitations and Future Research

The current study had limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. These may also serve as catalysts for future work. First, the original survey was not intended to examine spirituality, and analysis was based on spontaneous spirituality references made during the open-ended questions. Furthermore, the current study defined spirituality, religiosity, and faith as a singular construct. Future studies should measure each directly with psychometrically valid measures and differentiate how each concept impacts well-being.

Another set of limitations focus on methodology. The current research used a cross-sectional and retrospective survey design. The nature of this type of design means that causality cannot be inferred. For example, though the current study found a relationship between the spirituality themes of relationship with God and mental health, we cannot with certainty say that having the perception of a relationship with God leads to better mental health. As such, the potential directional relationship of the variables should be interpreted with caution. Convenience and chain referral sampling were utilized in the current study. It was a one-time, online survey and was only translated into a few languages. A major disadvantage of these approaches is the lack of clear generalizability. Indeed, the current participants likely represent a subset of a broader population of care leavers. For example, in order to participate in the current study, participants had to have access to the internet and be literate. As a result, the current sample is likely biased toward urban, educated participants with a higher socioeconomic status, and potentially more positive long-term outcomes. Moreover, recruitment notices were distributed by an alliance for faith-based organizations. As such, participants represented in the current sample might be more likely to engage in spirituality and faith practices and may not be representative of care leavers in general. Future work should employ more robust and representative sampling methods, increase the number of languages available, and focus on recruiting representative samples that better capture the experiences of all care leavers.

Conclusion

Care leavers are at substantial risk for negative outcomes impacting them, their families, and their communities. Identifying factors that can support better outcomes in this population is a critical contribution to society. Learning from care leavers can help us to identify which factors seem to make a difference. Furthermore, their experiences and insights can improve outcomes for children separated from parental care now and in the future. Taken together, findings from the current study suggest that spirituality may play an important and unique role as a factor associated with resilience, mental health, physical health, and life satisfaction among care leavers. More research is necessary to understand the relationship in a more generalizable sample of this population. By better understanding how spirituality relates to positive outcomes in care leavers, we can improve the chances of better outcomes for children separated from parental care.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants of this study, as well as partners including Udayan Care, the Kenya Society of Care Leavers, Rwanda Network of Care Leavers, Uganda Care Leavers, Zimbabwe Care Leavers Network, CAFO member organizations, and all who gave input to this project. Laura Nzirimu was a tireless advocate in supporting the data collection process and has our deepest gratitude.

Funding

The authors would like to thank UBS Optimus Foundation for providing the funding that made this project possible.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Declarations

Ethics and Integrity Statements

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Samford University on 9/15/2020 (EXMT-A-20-F-2). All participants completed an informed consent.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Ager J, Fiddian-Qasmiyeh E, Ager A. Local faith communities and the promotion of resilience in contexts of humanitarian crisis. Journal of Refugee Studies. 2015;28(2):202–221. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fev001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alawiyah T, Bell H, Pyles L, Runnels RC. Spirituality and faith-based interventions: Pathways to disaster resilience for African American Hurricane Katrina survivors. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought. 2011;30(3):294–319. doi: 10.1080/15426432.2011.587388. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atluri N, Pogula M, Chandrashekar R, Gupta Ariely S. Mental and emotional health needs of orphaned and separated youth in New Delhi, India during transition into adulthood. Institutionalised Children Explorations and beyond. 2018;5(2):188–207. doi: 10.5958/2349-3011.2018.00015.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berejena Mhongera P, Lombard A. Poverty to more poverty: An evaluation of transition services provided to adolescent girls from two institutions in Zimbabwe. Children and Youth Services Review. 2016;64:145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.childyoUth.2016.03.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berens A, Nelson C. The science of early adversity: Is there a role for large institutions in the care of vulnerable children? The Lancet. 2015;386(9991):388–398. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61131-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Appleyard K, Dodge KA. Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment: Mediating mechanisms and implications for prevention. Child Development. 2011;82(1):162–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava R, Chandrashekhar R, Kansal S, Modi K. Young adults transitioning from institutional care to independent living: The role of aftercare support and services. Institutionalised Children Explorations and beyond. 2018;5(2):168–187. doi: 10.5958/2349-3011.2018.00014.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bondi B, Pepler D, Motz M, Andrews NC. Establishing clinically and theoretically grounded cross-domain cumulative risk and protection scores in sibling groups exposed prenatally to substances. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020;108:104631. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brislin RW. Cross-cultural research methods. In: Altman I, Rapoport A, Wohlwill JF, editors. Environment and culture. Boston, MA: Springer; 1980. pp. 47–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis T, Wong EC. Faith to move mountains: Religious coping, spirituality, and interpersonal trauma recovery. American Psychologist. 2013;68(8):675. doi: 10.1037/a0034380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C., & Bauer, S. (2021). Christian faith and resilience: Implications for social work practice. Social Work & Christianity, 48(1). 10.3403/SWC.V48I1.212

- Cohen A. Comparing regression coefficients across subsamples: A study of the statistical test. Sociological Methods & Research. 1983;12(1):77–94. doi: 10.1177/0049124183012001003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond C, Watt K, Saha A, Huang J, Lu C. Prevalence and number of children living in institutional care: Global, regional, and country estimates. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 2020;4(5):370–377. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickens L. One-year outcomes of youth exiting a residential care facility in South Africa. Child & Family Social Work. 2018;23(4):558–565. doi: 10.1111/cfs.12411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diener ED, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diraditsile K, Nyadza M. Life after institutional care: Implications for research and practice. Child & Family Social Work. 2018;23(3):451–457. doi: 10.1111/cfs.12436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Domoff S, Borgen A, Wilke N, Howard A. Adverse childhood experiences and problematic media use: Perceptions of caregivers of high-risk youth. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(13):6725. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18136725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drumm R, Popescu M, Cooper L, Trecartin S, Seifert M, Foster T, Kilcher C. “God just brought me through it”: Spiritual coping strategies for resilience among intimate partner violence survivors. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2013;42(4):385–394. doi: 10.1007/s10615-013-0449-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farivar SS, Cunningham WE, Hays RD. Correlated physical and mental health summary scores for the SF-36 and SF-12 Health Survey, V. 1. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2007;5(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faull K, Hills MD. The role of the spiritual dimension of the self as the prime determinant of health. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2006;28(11):729–740. doi: 10.1080/09638280500265946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feilzer MY. Doing mixed methods research pragmatically: Implications for the rediscovery of pragmatism as a research paradigm. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2010;4(1):6–16. doi: 10.1177/1558689809349691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Marks JS. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel Pratt S. Pragmatism as ontology, not (just) epistemology: Exploring the full horizon of pragmatism as an approach to IR theory. International Studies Review. 2016;18(3):508–527. doi: 10.1093/isr/viv003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frimpong-Manso K. Building and utilising resilience: The challenges and coping mechanisms of care leavers in Ghana. Children and Youth Services Review. 2018;87:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.02.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, Apolone G, Bjorner JB, Brazier JE, Bullinger M, Kaasa S, Leplege A, Prieto L, Sullivan M. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: Results from the IQOLA Project. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1998;51(11):1171–1178. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan R. Promoting positive outcomes for children in need: The assessment of protective factors. In: Horwath J, editor. The child’s world: Assessing children in need. Kingsley Publishers; 2001. pp. 180–193. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn CTB. A bridge over troubled waters: Spirituality and resilience with emerging adult childhood trauma survivors. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health. 2014;16(1):37–50. doi: 10.1080/19349637.2014.864543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howard ARH, Lynch A, Call CD, Cross D. Sensory processing in children with a history of maltreatment: An occupational therapy perspective. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2020;15(1):60–67. doi: 10.1080/17450128.2019.1687963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson LJ, White CR, O’Brien K, DiLorenzo P, Cathcart E, Wolf M, Bruskas D, Pecora PJ, Nix-Early V, Cabrera J. Exploring spirituality among youth in foster care: Findings from the Casey field office mental health study. Child & Family Social Work. 2010;15(1):107–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2009.00649.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig H. In the wake of disaster: Religious responses to terrorism & catastrophe. Templeton Foundation Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lund J, Toombs E, Radford A, Boles K, Mushquash C. Adverse childhood experiences and executive function difficulties in children: A systematic review. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020;106:104485. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunn J. The role of religion, spirituality and faith in development: A critical theory approach. Third World Quarterly. 2009;30(5):937–951. doi: 10.1080/0143659090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maarouf H. Pragmatism as a supportive paradigm for the mixed research approach: Conceptualizing the ontological, epistemological, and axiological stances of pragmatism. International Business Research. 2019;12(9):1–12. doi: 10.5539/ibr.v12n9p1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Makanui KP, Jackson Y, Gusler S. Spirituality and its relation to mental health outcomes: An examination of youth in foster care. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2019;11(3):203. doi: 10.1037/rel0000184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning LK. Enduring as lived experience: Exploring the essence of spiritual resilience for women in late life. Journal of Religion and Health. 2014;53(2):352–362. doi: 10.1007/s10943-012-9633-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marler PL, Hadaway CK. “Being religious” or “being spiritual” in America: A zero-sum proposition? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2002;41(2):289–300. doi: 10.1111/1468-5906.00117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS. Resilience theory and research on children and families: Past, present, and promise. Journal of Family Theory & Review. 2018;10(1):12–31. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire A, Huffhines L, Jackson Y. The trajectory of PTSD among youth in foster care: A survival analysis examining maltreatment experiences prior to entry into care. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2021;115:105026. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner K, Crawford P, Edgley A, Hare-Duke L, Slade M. The experiences of spirituality among adults with mental health difficulties: A qualitative systematic review. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. 2020;29:E34. doi: 10.1017/S2045796019000234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DL. Pragmatism as a paradigm for social research. Qualitative Inquiry. 2014;20(8):1045–1053. doi: 10.1177/1077800413513733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ögtem-Young Ö. Faith Resilience: Everyday Experiences. Societies. 2018;8(1):10. doi: 10.3390/soc8010010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Masters KS, Salsman JM, Wachholtz A, Clements AD, Salmoirago-Blotcher E, Trevino K, Wischenka DM. Advancing our understanding of religion and spirituality in the context of behavioral medicine. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2017;40(1):39–51. doi: 10.1007/s10865-016-9755-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsitau DS. The role of faith and faith-based organizations among internally displaced persons in Kenya. Journal of Refugee Studies. 2011;24(3):493–512. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fer035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perera WDP. Leaving alternative care: Building support systems for young people. Institutionalised Children Explorations and beyond. 2018;5(2):147–154. doi: 10.1177/2349301120180205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pham T, Qi H, Chen D, Chen H, Fan F. Prevalences of and correlations between childhood trauma and depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and suicidal behavior among institutionalized adolescents in Vietnam. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2021;115:105022. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refaeli T. Narratives of care leavers: What promotes resilience in transitions to independent lives? Children and Youth Services Review. 2017;79:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.05.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roser, M. (2014). Human development index (HDI). Our World in Data. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/human-development-index?ref=https://githubhelp.com. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- Ross N, Gilbert R, Torres S, Dugas K, Jefferies P, McDonald S, Savage S, Ungar M. Adverse childhood experiences: Assessing the impact on physical and psychosocial health in adulthood and the mitigating role of resilience. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020;103:104440. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell MH. Redeeming narratives in Christian community. In: Manning RR, editor. Mutual Enrichment between Psychology and Theology. Routledge; 2020. pp. 190–199. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J., Mason, B., & Kelly, A. (2022). ‘After god, we give strength to each other’: Young people’s experiences of coping in the context of unaccompanied forced migration. Journal of Youth Studies, 1–17. 10.1080/13676261.2022.2118033

- Scott LD, Jr, Hodge DR, White T, Munson MR. Substance use among older youth transitioning from foster care: Examining the protective effects of religious and spiritual capital. Child & Family Social Work. 2018;23(3):399–407. doi: 10.1111/cfs.12429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sil R, Katzenstein PJ. Analytic eclecticism in the study of world politics: Reconfiguring problems and mechanisms across research traditions. Perspectives on Politics. 2010;8(2):411–431. doi: 10.1017/S1537592710001179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simkiss D. The needs of looked after children from an adverse childhood experience perspective. Paediatrics and Child Health. 2019;29(1):25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.paed.2018.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;15(3):194–200. doi: 10.1080/10705500802222972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulimani-Aidan Y. To dream the impossible dream: Care leavers’ challenges and barriers in pursuing their future expectations and goals. Children and Youth Services Review. 2017;81:332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.08.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sulimani-Aidan Y, Melkman E. Risk and resilience in the transition to adulthood from the point of view of care leavers and caseworkers. Children and Youth Services Review. 2018;88:135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.03.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, Teddlie CB. Mixed methodology: Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tuck I, Anderson L. Forgiveness, flourishing, and resilience: The influences of expressions of spirituality on mental health recovery. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2014;35(4):277–282. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2014.885623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Breda A, Munro E, Gilligan R, Anghel R, Harder A, Incarnato M, Mann-Feder V, Refaeli T, Stohler R, Storø J. Extended care: Global dialogue on policy, practice and research. Children and Youth Services Review. 2020;119:105596. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Breda AD. A critical review of resilience theory and its relevance for social work. Social Work. 2018;54(1):1–18. doi: 10.15270/54-1-611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Breda AD, Dickens L. The contribution of resilience to one-year independent living outcomes of care-leavers in South Africa. Children and Youth Services Review. 2017;83:264–273. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M., Duschinsky, R., Fox, N., Goldman, P., Gunnar, M., Johnson, D. E., Nelson, C. A., Reijman, S., Skinner, M., Zeanah, C. H., & Sonuga-Barke, E. (2020). Institutionalisation and deinstitutionalisation of children 1: A systematic and integrative review of evidence regarding effects on development. The Lancet Psychiatry, S2215-0366. 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30399-2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke N, Howard AH, Morgan M, Hardin M. Adverse childhood experiences and problematic media use: The roles of attachment and impulsivity. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2020;15:1–12. doi: 10.1080/17450128.2020.1734706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke NG, Howard AH. Data-informed recommendations for faith communities desiring to support vulnerable children and families during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought. 2021;40(3):349–364. doi: 10.1080/15426432.2021.1895957. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke NG, Howard ARH, Todorov S, Bautista J, Medefind J. Antecedents to child placement in residential care: A systematic review. Institutionalised Children Explorations and beyond: An International Journal on Alternative Care. 2022;9(2):188–201. doi: 10.1177/2349300322108233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke, N. G., Roberts, M., Mitchell, T., & Howard, A. R. H. (In Press). Spirituality as a protective factor: A multinational study of 267 adults with care experience. Social Work & Christianity

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.