Abstract

Levonadifloxacin (intravenous) and its oral prodrug alalevonadifloxacin are broad-spectrum antibacterial agents developed for the treatment of difficult-to-treat infections caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-positive bacteria, especially methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, atypical bacteria, anaerobic bacteria, and biodefence pathogens as well as Gram-negative bacteria. Levonadifloxacin has a well-defined mechanism of action involving a strong affinity for DNA gyrase as well as topoisomerase IV. Alalevonadifloxacin with widely differing solubility and oral bioavailability has pharmacokinetic profile identical to levonadifloxacin. Unlike existing MRSA drugs such as vancomycin and linezolid, which cause unfavorable side effects like nephrotoxicity, bone-marrow toxicity, and muscle toxicity, levonadifloxacin/alalevonadifloxacin has demonstrated superior safety and tolerability features with no serious adverse events. Levonadifloxacin/alalevonadifloxacin could be a useful weapon in the battle against infections caused by resistant microorganisms and could be a preferred antibiotic of choice for empirical therapy in the future.

1. Introduction

Diseases caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria are associated with greater morbidity and mortality, and the use of current medications for previously treatable infections may become ineffective [1]. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is an important public health issue among the many resistant bacterial infections found throughout the world [2]. MRSA infections continue to be problematic in India, within both hospital and community settings [3]. Even though vancomycin, teicoplanin, and linezolid lack hallmarks of a “workhorse antibiotic” such as robust bactericidal action and a favorable safety profile, these remain the standard-of-care antibiotics for nosocomial MRSA infections. As a result, novel workhorse anti-MRSA treatments with an oral alternative for switch-over convenience are required.

There is also an unmet medical need in handling community MRSA infections. The management of community MRSA infections has further been hindered by the global introduction of a virulent, MDR, Panton-Valentine leucocidin-positive Bengal Bay clone (ST772-SCCmec type V; “SCCmec” stands for staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec) [4].

Levonadifloxacin (WCK 771), a benzoquinolizine fluoroquinolone, has a broad-spectrum activity against quinolone-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and MRSA phenotypes. In India, levonadifloxacin and its oral prodrug alalevonadifloxacin (WCK 2349) have recently been approved for the treatment of acute bacterial skin and soft structure infections (ABSSSI) with accompanying bacteremia and diabetic foot infections (DFI) [5]. These compounds have been subjected to several preclinical in vitro and in vivo, as well as clinical phase I studies to test their efficacy, safety, and toxicity. Several phase I trials have been performed in the United States (US) (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT01875939, NCT02253342, NCT02244827, and NCT02217930), and a phase II study has been undertaken in India. In comparison to oral and intravenous linezolid, both oral and intravenous versions have been tested in India for the indication of ABSSSI and DFI (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03405064).

This paper reviews the existing published data on levonadifloxacin and its prodrug alalevonadifloxacin, including relevant chemistry, mechanism of action, mechanism of resistance, microbiology, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, animal models, clinical trials, adverse effects, drug interactions, and their place in therapy. A comprehensive search of PubMed and Scopus was conducted using the search terms “levonadifloxacin and its prodrug alalevonadifloxacin” and “WCK 771” and “WCK 2349” to identify references for this review.

2. Multidrug Resistance and MDR Gram-Positive Infection

Antibiotics' efficacy, which has revolutionized medicine and saved millions of lives, is in jeopardy due to the increasing rise of resistant bacteria around the world. MDR has become a major issue in recent years, since the rate at which new antibiotics are developed has decreased dramatically while antibiotic use has increased [6, 7]. Each year, MDR infections kill at least 50,000 people in Europe and USA alone, with hundreds of thousands more dying in other parts around the globe. According to a UK Government-commissioned Review, it is anticipated that MDR might kill 10 million people each year by 2050, resulting in a total economic output of $100 trillion USD [8, 9].

The global spread of drug resistance among Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus species along with common respiratory pathogens like Streptococcus pneumoniae and Mycobacterium tuberculosis has reached epidemic proportions.

Many common antibiotics are becoming resistant to vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) and a growing number of other pathogens. The majority of human enterococcal infections are caused by E. faecalis and E. faecium, which are also a primary cause of hospital-acquired and MDR infections. In patients with no risk factors, E. faecalis can cause community-acquired endocarditis [10]. A study on bacterial isolates obtained from patients of nursing facilities demonstrated 11.7% prevalence of E. faecalis colonization, acquired at a rate of 4.1 cases per 1000 person-days, with an inferred duration of carriage of 32 days [11]. Another study showed E faecalis prevalence of 8.6% and high rates of resistance to gentamicin, erythromycin, and vancomycin among Egyptian patients with hospital-acquired infections [12].

3. Staphylococcus aureus: A Gram-Positive Pathogen of Particular Concern

Staphylococcus aureus is a common cause of both hospital-acquired and community-acquired infections as well as skin and soft-tissue infections in both healthy people and those with risk factors or underlying conditions [13]. Due to its propensity to survive within monocytes and phagocytes, such as endothelial cells, epithelial cells, fibroblasts, osteoblasts, and keratinocytes, this pathogen has been proven to be the source of persistent infections at diverse anatomical sites [14]. MRSA can cause difficult-to-treat staph infections because of resistance to some antibiotics [15]. Over time, MRSA infections have become more common worldwide. MRSA isolates were first found in 1961 from United Kingdom [16]. The percentage of S. aureus infections worldwide ranges from 13 to 74%. In USA, the incidence rate of invasive MRSA infections in 2005 was found to be 31.8 per 100,000, where S. aureus bacteremia was the primary cause of 75% of these infections [17]. As per global surveillance report from the South-East Asia and Western Pacific Region, incidence rate of MRSA was found to be 2.3–69.1% [18, 19]. Due to an increase in community-acquired infections, the prevalence of MRSA bacteremia rose between 2000 and 2008 in Canada, Australia, and Scandinavia [18]. According to a recent systemic analysis, MRSA accounted for >100,000 deaths and 3.5 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) globally in 2019, associated with antimicrobial resistance [20]. A recent meta-analysis in India observed 37% total prevalence with pooled prevalence of MRSA varying between 31 and 39% during 2015–2019 and 69% in 2020 [21]. Another study showed a continuous rising trend of MRSA in different clinical samples from North India over 3 years (28% in 2017 to 35.1% in 2019) [22]. Several studies have found that patients infected with MRSA have a higher 30-day and 90-day mortality risk, as well as a 1.19-fold increase in hospital expenses when compared to those infected with methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) [23, 24]. CDC and PHAC consider MRSA to be a serious threat and a high priority, respectively [13, 15].

MRSA strains were once restricted to hospitals, that is, hospital-associated MRSA (HA-MRSA); however, in the last 20 years, MRSA have emerged in the general populations (through variation and recombination) in diverse communities (community-associated MRSA or CA-MRSA) [25]. HA-MRSA and CA-MRSA differ not only in terms of clinical characteristics and molecular biology but also in terms of antibiotic susceptibility and treatment. Genotypically, CA-MRSA are newer and more virulent strains (with types IV or V SCCmec and Panton-Valentine leucocidin (PVL) encoding genes) and are generally susceptible to non-β-lactam antimicrobials [25–27].

MRSA's emergence is multifactorial, where host factors, infection control practices, and antimicrobial pressures play a major role. Bacterial mutation leading to the emergence of bacterial resistance phenotypes is associated with the clinical use of antimicrobial agents to which the bacteria are resistant. Bacteria that survive treatment with one antibiotic develop resistance to the effects of that drug and similar drugs [28, 29]. A study revealed that a change in normal colonizing flora (from MSSA to MRSA) of an individual occurs within 24–48 hours under selective antibiotic pressures [30]. Prolonged length of hospitalization, intensive care admission and recent or current hospitalization, recent or long-term antibiotic use, MRSA colonization, invasive procedures (such as urinary catheters, intra-arterial lines, or central venous lines), people with weak immune system (such as HIV infection), admission to nursing homes, open wounds, hemodialysis, and discharge with long-term central venous access or long-term indwelling urinary catheter are all risk factors for MRSA infection, contributing to an overall rise in medical costs, which can be catastrophic in a nation like India [28, 31]. MRSA infection is also more common among healthcare personnel who have direct contact with patients infected with these bacteria [29, 32].

4. Management of MDR Gram-Positive Infection: An Unmet Medical Need

4.1. Available Antimicrobial Agents

Over many decades, antimicrobial medicines have been the cornerstone of treatment for bacterial infections. Several drugs, including glycopeptides (e.g., vancomycin and teicoplanin), linezolid, tigecycline, and daptomycin, and even some beta-lactams, such as ceftaroline and ceftobiprole, continue to be active against MRSA [33]. For severe or life-threatening infections, glycopeptides and lipopeptides (vancomycin, teicoplanin, and daptomycin) were the recommended treatment, with linezolid serving as a unique alternative for oral down-step therapy despite the lack of robust safety and pharmacokinetic data and the unpredictable MRSA-strains' susceptibility profile against these [34]. Quinupristin/dalfopristin, a streptogramin antibiotic, and linezolid, an oxazolidinone, appear to be effective against vancomycin-resistant Gram-positive bacteria strains [35]. A number of newer antimicrobial agents including fluoroquinolone antibiotics were approved for the treatment of MRSA and other MDR Gram-positive pathogens.

4.2. Issue with Currently Available Agents

An ideal antibiotic should have a broad-spectrum bactericidal activity along with no teratogenic effects and drug-drug interactions. Despite missing hallmarks of a “workhorse antibiotic” such as robust bactericidal action and a favorable safety profile, vancomycin, daptomycin, teicoplanin, and linezolid have been considered to be the standard-of-care antibiotics against MRSA infections. However, vancomycin has significant drawbacks, such as relatively weak bactericidal activity, varying MICs, accompanying therapeutic failure, poor pharmacokinetic properties, and the risk for serious toxicity. Moreover, its usage has been restricted in recent years by the emergence of both tolerant and resistant species [36]. Furthermore, studies have shown association of vancomycin with production of hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis and “red man syndrome” and high-dose vancomycin therapy with the incidence of nephrotoxicity [36–38]. Vancomycin also shows poor penetration to certain body tissues, notably cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [39]. Although antibacterial, daptomycin is ineffective in pneumonia and concomitant bacteremia [40]. Daptomycin has demonstrated comparable efficacy to vancomycin in complicated SSTIs, endocarditis, and MRSA bacteremia but not in pneumonia because of inactivation by alveolar surfactant [41]. However, reports have suggested rising daptomycin MICs of 1–2 μg/mL in association with vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA) and heteroresistant VISA (hVISA) strains, thereby raising concerns for cross resistance between daptomycin and vancomycin in hVISA and VISA [42]. Increased MIC of daptomycin was also found to be associated with increased mortality in patients with MRSA bacteremia. Last but not least, daptomycin has been linked to elevated creatine kinase levels and rhabdomyolysis [43], which is troublesome in critically ill patients who are already at risk for these increases and their side effects, like renal injury.

Though linezolid is easily administered orally, prolonged therapy is frequently linked with myelosuppression, necessitating blood parameter monitoring. Recent data imply that linezolid may be unsafe in patients with renal impairment due to its overexposure [44]. Furthermore, because of its weak bactericidal activity, linezolid is not recommended for immunosuppressed or bacteremia patients [44]. Clindamycin use for community MRSA infections is similarly limited due to high prevalence of inducible macrolide resistance in MRSA and numerous reports of antibiotic-associated colitis and antibiotic-associated diarrhea [44, 45]. Table 1 summarizes the common limitations of the currently available anti-MRSA agents.

Table 1.

Common limitations of the currently available anti-MRSA agents.

| Antibiotic | Mechanism of action | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Vancomycin | (i) Inhibits cell wall (peptidoglycan) synthesis (ii) Bactericidal activity (variable) |

(i) MIC creep, hVISA development (ii) Variable tissue penetration (iii) Potential for nephrotoxicity at higher concentrations and in combination with other nephrotoxic agents (iv) Need for TDM |

|

| ||

| Daptomycin | (i) Disrupts cell membrane potential through rapid depolarization (ii) Bactericidal activity |

(i) Inactivated by pulmonary surfactant, not effective treatment of MRSA pneumonia (ii) Potential for decreased susceptibility with increased vancomycin MIC and hVISA |

|

| ||

| Linezolid | (i) Inhibits protein synthesis through binding of 50S ribosomal subunit (ii) Bacteriostatic activity |

(i) Multiple potentially serious side effects (marrow suppression, lactic acidosis, peripheral and optic neuropathy, serotonin syndrome), especially with prolonged use |

|

| ||

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | (i) Inhibits multiple stages in bacterial folate and thymidine synthesis (ii) Bactericidal activity |

(i) May be ineffective in infections involving undrained pus due to thymidine scavenging (ii) Limited data supporting use in bacteremia and endocarditis |

|

| ||

| Clindamycin | (i) Inhibits protein synthesis through binding of 50S ribosomal subunit (ii) Bacteriostatic activity |

(i) Largely unproven for treatment of invasive infections in adults (ii) Inducible resistance can be missed if D-testing is not performed on clinical isolates (iii) Association with antibiotic-associated diarrhea and Clostridium difficile colitis |

|

| ||

| Tetracyclines | (i) Inhibit protein synthesis through binding of 30S ribosomal subunit (ii) Bacteriostatic activity |

(i) Unproven for treatment of invasive infections |

|

| ||

| Tigecycline | (i) Inhibits protein synthesis through binding of 30S ribosomal subunit (ii) Bacteriostatic activity |

(i) Low serum levels (ii) Probably not effective in treatment of HA-MRSA pneumonia |

|

| ||

| Quinupristin/dalfopristin | (i) Synergistic combination of two streptogramin compounds that inhibit protein synthesis (ii) Bactericidal activity in the absence of MLSB resistance |

(i) Frequent side effects (arthralgias, myalgias, venous intolerance) (ii) Multiple drug-drug interactions (iii) Limited data supporting use in invasive disease |

|

| ||

| Rifampicin | (i) Inhibits bacterial transcription (ii) Bactericidal activity |

(i) Rapid development of resistance; cannot be used as monotherapy (ii) Multiple drug-drug interactions (iii) Potential hepatotoxicity |

|

| ||

| Teicoplanin | (i) Inhibits cell wall synthesis | (i) Nephrotoxicity (ii) MIC creep (iii) 2-3 days required to reach therapeutic levels, even with loading dose (iv) Variable tissue penetration (v) Dose adjustment required in renal patients (vi) TDM is recommended |

|

| ||

| Ceftaroline | (i) Binds to penicillin binding protein (PBP2a) and inhibits the synthesis of the peptidoglycan layer of bacterial cell walls | (i) Poor intracellular concentration (ii) Dose adjustment in renal patients (iii) Cannot be used as monotherapy in CABP (iv) Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea |

CABP: community-acquired bacterial pneumonia; HA-MRSA: hospital-associated MRSA; hVISA: heteroresistant vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus; MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration; MLSB: macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B; MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; TDM: therapeutic drug monitoring.

4.3. Empirical MDR Gram-Positive Coverage

Empirical therapy with broad-spectrum antimicrobials plays a major role in the pharmacotherapy of complicated skin and soft-tissue infections (SSTIs), postsurgical site infections, and potential drug-resistant organisms like MRSA [46, 47]. Unlike definitive treatment, empirical or presumptive anti-infective therapy is one-time treatment administered for a presumed infection which is based on a clinical diagnosis along with evidence from the literature and educated experience with the bacteria that are likely to cause the infection [48]. When starting empiric antibiotics, it is critical that this therapy be started as soon as possible and as appropriately as possible, because delays in treatment are correlated with adverse outcomes [47, 48].

An initial empiric therapy utilizes broad-spectrum antimicrobial medicines in order to cover many potential infections linked with the specific clinical condition. However, once laboratory findings of microbiology tests with pathogen identification and antimicrobial susceptibility data are known, every effort should be undertaken to narrow the antibiotic spectrum. This is an important component of antimicrobial therapy, since it can lower cost and toxicity while also considerably delaying the emergence of antibiotic resistance in the community [48].

Thus, every effort should be made to carefully select antibiotics, balancing the necessity for wide empiric coverage of possible bacteria with the need to preserve existing antibiotics for when they are absolutely necessary. Current antibiotics' resistance or safety deficiency-related restrictions, as well as halted anti-infective drug research, raise the possibility of diverse resistance mechanisms spreading globally. Therefore, there is an unmet need for the development of novel treatments that are effective against a broad spectrum of multidrug-resistant Gram-positive bacteria.

5. Levonadifloxacin: New Agent for MDR Gram-Positive Pathogen (MRSA)

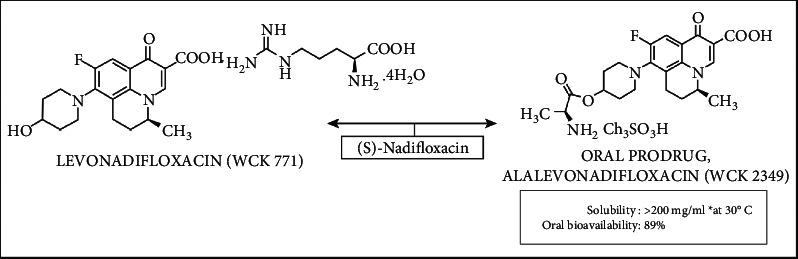

After a 14-year hiatus, the two forms of novel anti-MRSA agent “levonadifloxacin,” intravenous and oral, have recently been launched in India by Wockhardt Limited as EMROK and EMROK O, respectively. The structure of injectable and oral prodrug of levonadifloxacin is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structure of injectable and oral prodrug of levonadifloxacin.

Both forms have been recently approved by Drug Controller General of India and are licensed for the treatment of ABSSSI coexisting with bacteremia as well as DFI. The important features of levonadifloxacin are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Features of levonadifloxacin.

| Antibiotic class | Benzoquinolizine fluoroquinolone |

|---|---|

| Administration route | Intravenous and oral |

| Intravenous dose regimen | 800 mg BID |

| Oral dose regimen | 1000 mg BID |

| Indications | ABSSSI with concurrent bacteremia and DFI |

| Activity spectrum | MRSA, QRSA, VRSA, VISA, Quinolone-S Gram-negatives, RTI pathogens |

| MRSA coverage | >99 percent |

| Gram-negative coverage | Partial |

| Intracellular activity | Yes (including MRSA + QRSA) |

| Biofilm eradication | Strong action for MRSA/QRSA biofilms |

| Activity in acidic conditions | Enhanced |

| T max | 2.68 ± 1.27 h for oral 1000 mg |

| C max | 21.48 ± 8.82 μg/mL for oral 1000 mg |

| Plasma AUC | Highest plasma exposures among quinolones |

| Intravenous 800 mg: 377.8 ± 35.33 mg·h/L | |

| Oral 1000 mg: 318.4 ± 33.2 | |

| Epithelial lining fluid AUC | Highest lung penetration among quinolones 1000 mg oral OD: 345.2 μg·h/mL |

| Mean elimination half-life of 800 mg BID infused over 90 minutes | 6.8 hours |

| Metabolism | 72% of intravenous levonadifloxacin excreted as levonadifloxacin sulfate metabolite (approximately 50.3% in urine and 21.6% in faeces) |

| Dose adjustment in renal impaired patients | Not required∗ |

| Dose adjustment in hepatic impairment | Not required |

| Liver safety | Very good |

| Cardiovascular system safety | Excellent |

| Gastrointestinal tolerability | Excellent |

∗ <5% of dose is excreted as unchanged levonadifloxacin suggesting minimal role of renal system in elimination of levonadifloxacin. ABSSSI: acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections; AUC: area under curve; BID: bis in die/twice a day; CAP: community-acquired pneumonia; cIAI: complicated intra-abdominal infections; Cmax: maximum mean plasma concentration; DFI: diabetic foot infections; MDR: multidrug-resistant; MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA: methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; QRSA: quinolone-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; RTI: respiratory tract infections; Tmax: time to reach maximum concentration; VISA: vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus; VRSA: vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

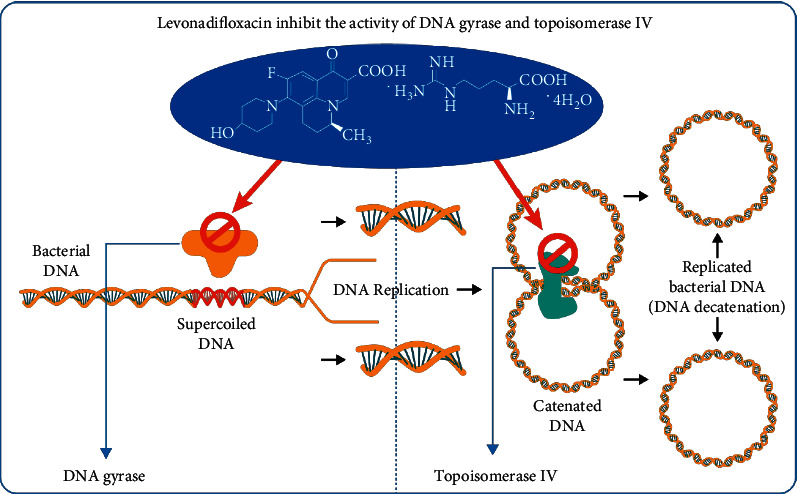

6. Levonadifloxacin: Mechanism of Action

The Korean Society of Infectious Diseases and the Korean Society for Chemotherapy's 2018 guidelines highly support the use of respiratory fluoroquinolones as empirical therapy, with a very high level of evidence [49]. Quinolones are known to have cidal activity by increasing the concentration of DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV enzyme-DNA cleavage complexes. Because bound quinolone physically prevents future ligation reactions, the cleavage caused by these complexes results in permanent chromosomal breakage. When a significant number of DNA strands break, other DNA repair processes are overwhelmed, resulting in bacterial cell death [50]. It is believed that, because of the presence of chiral benzoquinolizine core, levonadifloxacin shows a strong affinity for DNA gyrase, while retaining significant affinity towards topoisomerase IV. In contrast to other quinolones, such as ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin, which largely block DNA topoisomerase IV, levonadifloxacin has a well-defined mechanism of action involving a strong affinity for staphylococcal DNA gyrase as well as topoisomerase IV as shown in Figure 2 [51, 52].

Figure 2.

The mechanism of action of levonadifloxacin.

7. Levonadifloxacin: Spectrum of Activity

Levonadifloxacin is a fluoroquinolone benzoquinolizine having broad-spectrum action against respiratory Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens, including methicillin- and quinolone-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis, and also against atypical pathogens such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, M. genitalium, M. hominis, Ureaplasma spp. (including macrolide-, tetracycline-, and levofloxacin-resistant strains), Chlamydophila pneumoniae, and Legionella pneumophila (Table 3). A study demonstrated high activity against contemporary Gram-positive pathogens collected from various Indian hospitals [51]. It even has clinical benefits against quinolone-susceptible Gram-negative bacteria such as E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas, and Acinetobacter [50, 53]. Bioterror organisms such as Bacillus anthracis, Francisella tularensis, Burkholderia mallei, Yersinia pestis, and Burkholderia pseudomallei have also been shown to be susceptible to levonadifloxacin [44]. Levonadifloxacin has the benefit of being effective against resistant organisms with a very low mutation rate [54, 55]. Because of its large concentrations in the lungs and powerful intracellular activity against a wide range of possible respiratory pathogens, levonadifloxacin may be ideally suited for the treatment of extracellular and intracellular bacterial pathogen-caused respiratory infections, particularly in COVID-19 [56]. Levonadifloxacin not only kills biofilm-embedded QRSA and MRSA but also inhibits the NorA efflux pump, which is an important big contributor of development of quinolone resistance [57].

Table 3.

Unique multispectrum coverage of levonadifloxacin.

| Spectrum of activity of levonadifloxacin | Organisms |

|---|---|

| Excellent Gram-positive bacteria coverage | (i) Staphylococcus aureus: MSSA, MRSA, QRSA, VRSA |

| (ii) Coagulase-negative staphylococci | |

| (iii) Staphylococcus epidermidis | |

| (iv) Streptococcus pneumoniae | |

| (v) Streptococcus pyogenes | |

| (vi) Streptococcus agalactiae | |

| (vii) Viridans group streptococci | |

|

| |

| Quinolone sensitive Gram-negative (at par with ciprofloxacin) | (i) Escherichia coli |

| (ii) Klebsiella spp. | |

| (iii) Enterobacter spp. | |

| (iv) Citrobacter spp. | |

| (v) Proteus spp. | |

| vi) Providencia spp. | |

| (vii) Pseudomonas aeruginosa | |

| (viii) Moraxella catarrhalis | |

| (ix) Haemophilus influenzae | |

|

| |

| Good anaerobic coverage | (i) Clostridium difficile |

| (ii) Clostridium perfringens | |

| (iii) Cutibacterium (Propionibacterium) acnes | |

| (iv) Peptostreptococcus spp. | |

|

| |

| Good atypical bacteria coverage | (i) Mycoplasma |

| (ii) Chlamydia pneumoniae | |

| (iii) Chlamydia trachomatis | |

| (iv) Legionella pneumophila | |

| (v) Ureaplasma | |

MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA: methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; QRSA: quinolone-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; VRSA: vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

According to a study, WCK 771 exhibit bactericidal activity against vancomycin-resistant S. aureus strain HMC3 isolated from a patient's heel wound at the Hershey Medical Center, USA [58]. A study demonstrated the immunomodulatory effects of levonadifloxacin. In a lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human whole-blood (HWB) model, levonadifloxacin dramatically reduced inflammatory responses by inhibiting proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, and, in mouse acute lung injury (ALI) model, it reduced lung total white blood cell count, myeloperoxidase, and cytokine levels, with peak effect observed mostly at 24 h [53]. The favorable safety and efficacy of levonadifloxacin in subjects receiving medications for comorbidities such as antidiabetics or antihypertensives show low drug-drug interaction, which is due to levonadifloxacin's lack of CYP interaction [59].

8. Meeting the Unmet Need with Levonadifloxacin IV and Oral

An oral version with equal PK/PD was required as a step-down therapy and therefore the L-arginine salt formulation (alalevonadifloxacin or WCK 2349) was created. It has a high oral bioavailability (89%) and has been successfully developed and launched as levonadifloxacin oral prodrug formulation (EMROK O) in India [60, 61]. Multiple phase I studies have been performed with levonadifloxacin IV and oral in India and the USA. A brief account of phase I studies is discussed in the following sections.

8.1. Phase I Indian Trial

A study was performed in India with a goal of investigating the pharmacokinetics of intravenous WCK 771. Healthy adult male subjects were administered single doses of ECK 771 ranging from 50 mg to 1200 mg, multiples doses of 500 mg and 600 mg twice daily for 1 day, and 600 mg to 1200 mg twice daily for 5 days. The results of this study showed that there was a linear increase in Cmax and AUC(0–∞) for 50 mg to 1200 mg single doses. Cmax ranged between 1.84 and 32.33 μg/mL and AUC(0–∞) ranged between 10.07 and 277.66 μg·hr/mL. The AUC(tau) at steady state for BID for 5 days was not statistically different from the AUC(0–∞) following corresponding single doses at all four dose levels. Accumulation could be seen after several doses. Furthermore, throughout single dose and multiple doses, the terminal elimination half-life (t1/2) remained constant at around 6–8 hours [62].

8.2. Phase I US Trial

Two separate trials in USA were conducted to evaluate the safety, pharmacokinetics, and tolerability of multiple ascending (twice daily at 12-hour intervals for 5 days) doses of WCK 771 (600, 800, or 1000 mg) and WCK 2349 (800, 1000, or 1200 mg). Mean total and peak exposures of levonadifloxacin increased from 800 to 1000 mg after WCK 2349 but the values remained relatively unchanged from 1000 to 1200 mg. The mean t1/2 of levonadifloxacin was comparable across dosages and ranged from 9.7 to 10.4 hours and from 8.28 to 9.62 hours for WCK 771 and WCK 2349, respectively. There were no deaths or serious adverse events in both studies. Therefore, both WCK 771 and WCK 2349 administered in multiple escalating doses were well tolerated by the US subjects [63]. The steady-state volume of distribution (Vss) ranged from 145.34 to 172.0 L after intravenous WCK 771 injection, the clearance (CLss) ranged from 6.7 to 8.2 L/h, and the terminal t1/2 was 8.5–12 hours. The accumulation factor ranged from 0.99 to 1.1 over 5 days, indicating negligible or minimal buildup [64].

8.3. Phase I Study: Intrapulmonary Pharmacokinetics of Levonadifloxacin

A phase I study was conducted in healthy adult human subjects with an aim to compare plasma, epithelial lining fluid (ELF), and alveolar macrophage (AM) concentrations of levonadifloxacin following oral administration of alalevonadifloxacin (1000 mg twice daily for 5 days). The penetration ratios for ELF and AM to plasma concentration for levonadifloxacin were 7.66 and 1.58, respectively, supporting its use for lower respiratory tract infections. Oral levonadifloxacin's elimination half-life, clearance, and volume of distribution were found to be 6.35 h, 8.17 L/hour, and 59.2 L, respectively. The phase I study concluded that the oral administration of alalevonadifloxacin at a dose of 1,000 mg twice day for 5 days was shown to be safe and well tolerated (NCT02253342) [61].

8.4. Phase I Study: Drug-Food Interaction

Furthermore, Bhagwat et al. investigated the influence of food on WCK 2349 oral absorption and assessed the absolute bioavailability of WCK 2349 at 1000 mg in comparison to 800 mg WCK 771 administered as an intravenous infusion. WCK 2349 given in the fed condition reduced Cmax by 27% compared to the fasted state and delayed the time to achieve Cmax (Tmax) by 2 hours. The AUC values, on the other hand, remained unchanged. The study demonstrated that WCK 2349 could be delivered regardless of fed or fasted state. WCK 2349 had an absolute bioavailability of 89.35 percent and similar concentration-time profile of levonadifloxacin when compared to WCK 771. In a nutshell, these findings suggest that switching from an intravenous to an oral formulation of levonadifloxacin is effective for inpatients (NCT01875939) [50, 65].

8.5. Phase I Study: Effect on QT Interval

In another study, the electrocardiographic (ECG) effects of WCK 2349 at a supratherapeutic oral dose of 2,600 mg in 48 normal participants were compared to placebo and oral moxifloxacin (400 mg). WCK 2349 had no effect on baseline and placebo-corrected QTcF (QT interval adjusted for heart rate using the Fridericia method), QRS, or PR interval. Except for a possibly transient elevation in HR, which appears to be clinically negligible, a supratherapeutic dose of WCK 2349 is not likely to elicit clinically significant ECG effects and thus can provide a viable alternative to QT prolonging antibiotics (NCT02217930) [66].

8.6. Phase I Study: PK in Hepatic Impairment

Another phase I trial was conducted to understand the pharmacokinetics of levonadifloxacin and alalevonadifloxacin in patients with hepatic impairment. The study data suggested that WCK 771 and WCK 2349 could be safely administered to patients with hepatic impairment in order to obtain a therapeutically suitable PK profile (NCT02244827) [50].

9. Potential Benefits of Levonadifloxacin

In nonclinical and clinical investigations, levonadifloxacin and its prodrug alalevonadifloxacin (WCK 2349, oral) have been studied for the treatment of ABSSSI, CABP, and other types of infections.

9.1. In ABSSSI with DFI

A multicentric phase 3 trial which was an active-comparator study was completed recently. The aim of the study was to establish the noninferiority of oral levonadifloxacin (1000 mg) with oral linezolid (600 mg) and the noninferiority of IV levonadifloxacin (800 mg) with IV linezolid (600 mg) in ABSSSI, including diabetic foot infection at Test of Cure (TOC) visit. Before the commencement of this phase 3 trial, 157 subjects (healthy volunteers) in multiple phase I studies (115 subjects from India and 42 subjects from USA) and 104 subjects in phase II (India) studies received IV levonadifloxacin, and 287 subjects (263 healthy volunteers and 24 hepatically impaired subjects) in multiple phase I studies (94 subjects from India and 193 subjects from USA) and 119 subjects in phase II (India) studies received oral levonadifloxacin.

When compared to linezolid (IV and oral), levonadifloxacin (IV and oral) exhibited a greater clinical responder rate of 85.2% and 92.7% during visit 3 (days 3-4). The clinical cure rate at TOC was also found to be higher in levonadifloxacin (IV and oral) when compared to linezolid (IV and oral), that is, 95% versus 89.3%, respectively, for MRSA patients, indicating its favorable microbiological efficacy. Additionally, in the diabetic foot ulcer subgroup, clinical cure at TOC for levonadifloxacin IV was higher than that for linezolid (91.7% versus 76.9%). The pharmacokinetic investigation revealed that the bioavailability of oral levonadifloxacin was 90%, and the comparable pharmacokinetic profile of levonadifloxacin by both routes provides an alternative for switch from IV to oral treatment. Mild constipation (3.6%), hyperglycemia (1.6%) of mild-to-moderate severity, and being not related to levonadifloxacin as majority of these patients had high blood glucose at screening and cough (1.2%) (mild severity and not related to levonadifloxacin) were the most common AEs reported in levonadifloxacin-treated subjects. Overall, both IV and oral levonadifloxacin treatments were well tolerated and noninferior to IV and oral linezolid in participants with ABSSSI (NCT03405064; CTRI No.: CTRI/2017/06/008843) [67]. The PIONEER study also indicated remarkable clinical success rates of 98.2% for ABSSSI and 95.1% for DFI [68].

9.2. In CABP/Lower Respiratory Tract Infection

A multicenter, retrospective, postmarketing, real-world study as a part of PIONEER study was conducted to document the outcomes of oral and/or intravenous administration of levonadifloxacin for the treatment of lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI), in particular CABP in hospital and outpatient settings. 338 pneumonia/LRTI patients included in the study were given levonadifloxacin as empirical therapy with clinical success rates for the drug as 93.5% with intravenous therapy, 98.7% with oral therapy, and 100.0% with intravenous followed by oral therapy. Moreover, investigators graded levonadifloxacin therapy as “excellent to good” for efficacy in 95.2% of patients and “very good” for safety in 97.9% of patients. Only 4 (1.2 percent) of the 338 individuals who received levonadifloxacin had a total of 5 (1.5 percent) minor adverse events, with nausea in three patients and diarrhea and fatigue in one patient each. The study thus displayed a favorable PK/PD and safety profile of levonadifloxacin in the case of LRTI/CABP [59].

9.3. In Febrile Neutropenia

Years of empirical antibiotic treatment have resulted in a shift in infection pathogens from primarily Gram-negative bacteria to more Gram-positive bacteria. Empirical antibiotic therapy in the treatment of fever and neutropenia reduces the risk of developing sepsis, septic shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome, organ failure, and mortality [69]. Fluoroquinolone antimicrobial prophylaxis has been shown to reduce the incidence of neutropenic fever, infection rates, hospitalization rates, and length of hospital stay in this patient population [70]. Fluoroquinolone prophylaxis also lowers febrile neutropenia in patients with solid tumors or lymphoma receiving cyclical standard-dose myelosuppressive chemotherapy [71]. Levonadifloxacin has also proved to be an effective agent for prophylaxis of febrile neutropenia because of its good safety and efficacy profile. The clinical success rate for treating febrile neutropenia with levonadifloxacin medication (oral/IV) was found to be 93.8% in the PIONEER research [72].

9.4. In Bone and Joint Infections

Staphylococcus aureus is the primary cause of bone and joint infections (BJI). BJI caused by MRSA necessitates the use of antibiotics for a longer period of time, which cannot be done safely with the present anti-MRSA drugs due to their adverse events. Studies have shown excellent levonadifloxacin's resistance mechanisms such as the NorA efflux pump, DNA Gyrase/Topo IV mutations, and biofilm formation, which indicate that this drug can potentially be used to treat difficult-to-treat BJI [68, 73]. Levonadifloxacin demonstrated very good results in PIONEER study for BJI, with clinical success rates of 100% [72]. Additional research works employing BJI animal models as well as human trials are required to thoroughly examine levonadifloxacin therapy and its positioning in the treatment of these infections. The various clinical trials of levonadifloxacin and alalevonadifloxacin are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of clinical studies with levonadifloxacin and alalevonadifloxacin.

| Aim of the Study | Dose | No. of subjects | Study outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crossover food-effect and absolute bioavailability study of alalevonadifloxacin [65] | 800 mg (IV) and 1000 mg (oral) | 12 | Alalevonadifloxacin could be delivered regardless of fed or fasted state. Alalevonadifloxacin had concentration-time profile similar to that of levonadifloxacin. These findings suggest that switching from an intravenous to an oral formulation of levonadifloxacin is effective for inpatients |

|

| |||

| Determine the supratherapeutic dose of alalevonadifloxacin and assess its effect on cardiac repolarization as shown by analysis of the QT interval [66] | Part 1: Single dose of 1800 mg, 2200 mg, 2600 mg, and 3000 mg Part 2: Single dose of 2600 mg, moxifloxacin 400 mg, and placebo matched to moxifloxacin |

Part 1: 32 (24 alalevonadifloxacin + 8 placebo) Part 2: 48 |

Supratherapeutic dose of alalevonadifloxacin is not likely to elicit clinically significant ECG effects and thus can provide a viable alternative to QT prolonging antibiotics |

|

| |||

| Evaluate the effect of hepatic impairment on the pharmacokinetics of levonadifloxacin and its sulfate metabolite after single oral dose administration of alalevonadifloxacin [50] | 1000 mg | 48 | There were no significant differences (p > 0.05) in the PK parameters of levonadifloxacin or its sulfate metabolite in mild or moderate hepatic impaired groups compared to normal matched control groups. Levonadifloxacin and alalevonadifloxacin could be safely administered to patients with hepatic impairment in order to obtain a therapeutically suitable PK profile |

|

| |||

| Determine and compare plasma, ELF, and AM concentrations of levonadifloxacin after oral administration of alalevonadifloxacin [61] | 1000 mg BID x 5 days | 31 | The penetration ratios for ELF and AM to plasma concentration for levonadifloxacin were 7.66 and 1.58, respectively, supporting its use for lower respiratory tract infections |

|

| |||

| Comparative study of levonadifloxacin (IV and oral) with linezolid (IV and oral) in ABSSSI [67] | Experimental: oral levonadifloxacin (1000 mg BID) or IV levonadifloxacin (800 mg BID) Active comparator: oral linezolid (600 mg BID) or IV linezolid (600 mg BID) |

501 | When compared to linezolid (IV and oral), levonadifloxacin (IV and oral) exhibited a greater clinical responder rate of 85.2% and 92.7%. The clinical cure rate was also found to be higher in levonadifloxacin (IV and oral) when compared to linezolid (IV and oral), i.e., 95% versus 89.3%, respectively, for MRSA patients, indicating its favorable microbiological efficacy. Additionally, in the diabetic foot ulcer subgroup, clinical cure for IV levonadifloxacin was higher than that for linezolid (91.7% versus 76.9%). |

ABSSSI: acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections; AM: alveolar macrophage; BID: bis in die/twice a day; ECG: electrocardiogram; ELF: epithelial lining fluid; IV: intravenous; MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; PK: pharmacokinetic.

10. Superiority of Levonadifloxacin over Other Agents

Unlike other fluoroquinolones (moxifloxacin, levofloxacin, and ciprofloxacin) that degrade in acidic environments, levonadifloxacin showed improved activity at pH 5.5, increasing its therapeutic potential in intracellular infections and other clinical situations with acidic environments. The MIC of levonadifloxacin against S. aureus strains was 2, 8, and 16 times lower than those of moxifloxacin, levofloxacin, and ciprofloxacin, respectively, at pH 7.4 which was further reduced at pH 5.5. On the contrary, comparator quinolones saw a fourfold increase in MIC at pH 5.5 [14].

Levonadifloxacin had a steady bacterial death rate of 90% against methicillin- and quinolone-resistant Staphylococcus aureus embedded biofilms; clindamycin and linezolid had inconsistent efficacy, whereas vancomycin and daptomycin had no activity. Scanning electron microscopy images verified levonadifloxacin's efficiency against biofilm, demonstrating disruption of biofilm structure and a concomitant reduction in viable bacterial population [74].

In another study, WCK 771 showed the NorA efflux pump had no effect on the activity of WCK 771, indicating it as a major advantage, since a high number of staphylococcal isolates exhibit efflux-mediated fluoroquinolone resistance [75]. Table 5 compares the efficacy and side effects of currently available anti-MRSA drugs, including levonadifloxacin, vancomycin, teicoplanin, linezolid, daptomycin, ceftaroline, and omadacycline.

Table 5.

Comparative efficacy and safety parameters between anti-MRSA agents (Reddy et al. [76].

| Levonadifloxacin | Vancomycin/teicoplanin | Linezolid | Daptomycin | Ceftaroline | Omadacycline | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose | 800 mg BID (IV); 1000 mg BID (oral) |

Vancomycin: 0.5 g QD or 1 g BID Teicoplanin: 400 mg BID (LD); 400 mg OD (MD) |

600 mg BID | 500 mg OD | 600 mg BID | CAP: day 1: LD of 200 mg IV QD or 100 mg IV BID; day 2: MD of 100 mg IV QD or 300 mg PO QD SSTI: day 1: LD of 200 mg IV or 100 mg IV BID; day 2: MD of 100 mg IV QD or 300 mg PO QD OR SSTI (only for tablets): days 1 and 2: LD of 450 mg PO QD; day 3: MD of 300 mg PO QD |

|

| ||||||

| Spectrum | Broad | Narrow | Narrow | Narrow | Broad | Broad |

|

| ||||||

| Formulation | IV and oral | IV only | IV and oral | IV only | IV only | IV and oral |

|

| ||||||

| Bacterial killing | Cidal | Slow bactericidal | Static | Cidal | Cidal | Static |

|

| ||||||

| Major adverse effects | None | Nephrotoxicity | Bone-marrow suppression | Muscle toxicity | Diarrhea, nausea, and rash | Nausea, vomiting, infusion site reactions, alanine aminotransferase increased, aspartate aminotransferase increased, gamma-glutamyl transferase increased, hypertension, headache, diarrhea, insomnia, and constipation |

|

| ||||||

| Lung tissue concentration | Excellent | Poor | Good | Not active | Poor | Poor |

|

| ||||||

| MRSA Biofilm action | Yes | No | Moderate | No | No | No |

|

| ||||||

| Dose adjustment in RI | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

|

| ||||||

| Dose adjustment in HI | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

BID: bis in die/twice a day; CAP: community-acquired pneumonia; HI: hepatic impairment; IV: intravenous; LD: loading dose; MD: maintaining dose; MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; OD: once daily; PO: per os; QD: quaque die/once daily; RI: renal impairment.

11. Conclusion

Levonadifloxacin (intravenous) and oral prodrug of levonadifloxacin, that is, alalevonadifloxacin, are broad-spectrum anti-MRSA benzoquinolizine subclass of quinolones. Both IV and oral forms have been studied for the treatment of ABSSSI, CABP, and other types of infections and phase II and phase III clinical studies have been completed, demonstrating that they are clinically acceptable therapeutic options for the management of complex and serious infections caused by MDR Gram-positive bacteria, especially MRSA with a very low frequency of mutation, atypical bacteria, anaerobic bacteria, and biodefence pathogens, as well as Gram-negative bacteria. Alalevonadifloxacin is formulated to release the active drug immediately after oral administration that is responsible for excellent uptake and bioavailability in both the fasting and fed states. The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of alalevonadifloxacin including improved aqueous solubility can help for an easy transition from parenteral to oral medication.

The existing MRSA drugs such as vancomycin, teicoplanin, daptomycin, and linezolid have unfavorable features such as nephrotoxicity, bone-marrow depression, and muscle toxicity and thus cannot be given to patients with compromised kidney/liver function or critically ill patients who require chronic therapy. However, unlike other MRSA drugs, clinical and nonclinical studies have established superior safety and tolerability features of levonadifloxacin/alalevonadifloxacin with no serious adverse events. Novel anti-MRSA agent like levonadifloxacin/alalevonadifloxacin is a therapeutic candidate for the management and treatment of difficult-to-treat infections caused by resistant pathogens and could be a preferred antibiotic of choice for empirical therapy. However, large-scale trials in India are needed to prove the efficacy and safety of levonadifloxacin therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank WorkSure® India for providing assistance in preparation of the manuscript. The authors would like to acknowledge efforts of Mr. Nitin Bhadana, Mr. Suraj Tiwari, Mr. Parth Thakkar, and Mr. Lyndon Dsouza in their assistance in manuscript writing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Koulenti D., Xu E., Song A., et al. Emerging treatment options for infections by multidrug-resistant gram-positive microorganisms. Microorganisms . 2020;8(2):p. 191. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8020191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gajdács M. The continuing threat of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antibiotics . 2019;8(2):p. 52. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics8020052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sunagar R., Hegde N. R., Archana G. J., Sinha A. Y., Nagamani K., Isloor S. Prevalence and genotype distribution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in India. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance . 2016;7:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blomfeldt A., Larssen K. W., Moghen A., et al. Emerging multidrug-resistant Bengal Bay clone ST772-MRSA-V in Norway: molecular epidemiology 2004–2014. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases . 2017;36(10):1911–1921. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-3014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appalaraju B., Baveja S., Baliga S., et al. In vitro activity of a novel antibacterial agent, levonadifloxacin, against clinical isolates collected in a prospective, multicentre surveillance study in India during 2016–18. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy . 2020;75(3):600–608. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenner A., Bhagwandin N., Kowalski S. P. Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) and Multidrug Resistance (MDR): Overview of Current Approaches, Consortia and Intellectual Property Issues . Geneva, Switzerland: World Intellectual Property Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gajdács M., Albericio F. Antibiotic Resistance: From the Bench to Patients. Antibiotics . 2019;8:p. 129. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics8030129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’neill J. The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance . London, UK: Wellcome Trust; 2016. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. [Google Scholar]

- 9.RoA R. Antimicrobial Resistance: Tackling a Crisis for the Health and Wealth of Nations . London, UK: Review on Antimicrobial Resistance; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levitus M., Rewane A., Perera T. Statpearls . Treasure Island, FL, USA: Statpearls Publishing; 2020. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis E., Hicks L., Ali I., et al. Epidemiology of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis colonization in nursing facilities. Open Forum Infectious Diseases . 2020;7 doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esmail M. A. M., Abdulghany H. M., Khairy R. M. Prevalence of multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecalis in hospital-acquired surgical wound infections and bacteremia: concomitant analysis of antimicrobial resistance genes. Infectious Diseases: Research and Treatment . 2019;12 doi: 10.1177/1178633719882929.117863371988292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Organization W. H. Prioritization of Pathogens to Guide Discovery, Research and Development of New Antibiotics for Drug-Resistant Bacterial Infections, Including Tuberculosis . Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubois J., Dubois M. Levonadifloxacin (WCK 771) exerts potent intracellular activity against Staphylococcus aureus in THP-1 monocytes at clinically relevant concentrations. Journal of Medical Microbiology . 2019;68(12):1716–1722. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.001102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers For Disease Control And Prevention. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019 . Atlanta, Georgia, US: Centers For Disease Control And Preventio; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Enright M. C., Robinson D. A., Randle G., Feil E. J., Grundmann H., Spratt B. G. The evolutionary history of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . 2002;99(11):7687–7692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122108599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klevens R. M., Morrison M. A., Nadle J., et al. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA . 2007;298(15):1763–1771. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hassoun A., Linden P. K., Friedman B. Incidence, prevalence, and management of MRSA bacteremia across patient populations-a review of recent developments in MRSA management and treatment. Critical Care . 2017;21(1):211–310. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1801-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Organization W. H. Antimicrobial Resistance Global Report on Surveillance: 2014 Summary . Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators, Ikuta K. S., Sharara F., et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet . 2022;399(10325):629–655. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patil S. S., Suresh K. P., Shinduja R., et al. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oman Medical Journal . 2022;37(4):p. e440. doi: 10.5001/omj.2022.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lohan K., Sangwan J., Mane P., Lathwal S. Prevalence pattern of MRSA from a rural medical college of North India: a cause of concern. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care . 2021;10(2):p. 752. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1527_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engemann J. J., Carmeli Y., Cosgrove S. E., et al. Adverse clinical and economic outcomes attributable to methicillin resistance among patients with Staphylococcus aureus surgical site infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases . 2003;36(5):592–598. doi: 10.1086/367653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson R. E., Slayton R. B., Stevens V. W., et al. Attributable mortality of healthcare-associated infections due to multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology . 2017;38(7):848–856. doi: 10.1017/ice.2017.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kateete D. P., Bwanga F., Seni J., et al. CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA coexist in community and hospital settings in Uganda. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control . 2019;8(1):94–99. doi: 10.1186/s13756-019-0551-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lakhundi S., Zhang K. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: molecular characterization, evolution, and epidemiology. Clinical Microbiology Reviews . 2018;31(4) doi: 10.1128/cmr.00020-18.e00020-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.David M. Z., Daum R. S. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology and clinical consequences of an emerging epidemic. Clinical Microbiology Reviews . 2010;23(3):616–687. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00081-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graffunder E. M., Venezia R. A. Risk factors associated with nosocomial methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection including previous use of antimicrobials. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy . 2002;49(6):999–1005. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkf009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeller J. L., Golub R. M. JAMA patient page. MRSA infections. JAMA . 2011;306(16):p. 1818. doi: 10.1001/jama.306.16.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schentag J. J., Hyatt J. M., Carr J. R., et al. Genesis of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), how treatment of MRSA infections has selected for vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium, and the importance of antibiotic management and infection control. Clinical Infectious Diseases . 1998;26(5):1204–1214. doi: 10.1086/520287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kulkarni A. P., Nagvekar V. C., Veeraraghavan B., et al. Current perspectives on treatment of Gram-positive infections in India: what is the way forward? Interdisciplinary perspectives on infectious diseases . 2019;2019:8. doi: 10.1155/2019/7601847.7601847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siddiqui A. H., Koirala J. Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus . Treasure Island, FL, USA: Statpearls Publishing; 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossolini G. M., Arena F., Pecile P., Pollini S. Update on the antibiotic resistance crisis. Current Opinion in Pharmacology . 2014;18:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bassetti M., Carnelutti A., Castaldo N., Peghin M. Important new therapies for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy . 2019;20(18):2317–2334. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2019.1675637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lundstrom T. S., Sobel J. D. Antibiotics for Gram-positive bacterial infections: vancomycin, teicoplanin, quinupristin/dalfopristin, and linezolid. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America . 2000;14(2):463–474. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kollef M. H. Limitations of vancomycin in the management of resistant staphylococcal infections. Clinical Infectious Diseases . 2007;45(Supplement_3):191–195. doi: 10.1086/519470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rostas S. E., Kubiak D. W., Calderwood M. S. High-dose intravenous vancomycin therapy and the risk of nephrotoxicity. Clinical Therapeutics . 2014;36(7):1098–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sivagnanam S., Deleu D. Red man syndrome. Critical Care . 2002;7(2):1–3. doi: 10.1186/cc1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ziglam H., Finch R. Limitations of presently available glycopeptides in the treatment of Gram-positive infection. Clinical Microbiology and Infections . 2001;7:53–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2001.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choo E. J., Chambers H. F. Treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Infection & chemotherapy . 2016;48(4):267–273. doi: 10.3947/ic.2016.48.4.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Enoch D. A., Bygott J. M., Daly M.-L., Karas J. A. Daptomycin. Journal of Infection . 2007;55(3):205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2007.05.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jevitt L. A., Smith A. J., Williams P. P., Raney P. M., McGowan J. E., Tenover F. C. In vitro activities of daptomycin, linezolid, and quinupristin-dalfopristin against a challenge panel of staphylococci and enterococci, including vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. Microbial Drug Resistance . 2003;9(4):389–393. doi: 10.1089/107662903322762833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Papadopoulos S., Ball A. M., Liewer S. E., Martin C. A., Winstead P. S., Murphy B. S. Rhabdomyolysis during therapy with daptomycin. Clinical Infectious Diseases . 2006;42(12):e108–e110. doi: 10.1086/504379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bakthavatchalam Y. D., Shankar A., Muniyasamy R., et al. Levonadifloxacin, a recently approved benzoquinolizine fluoroquinolone, exhibits potent in vitro activity against contemporary Staphylococcus aureus isolates and Bengal Bay clone isolates collected from a large Indian tertiary care hospital. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy . 2020;75(8):2156–2159. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nguyen H. M., Graber C. J. Limitations of antibiotic options for invasive infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: is combination therapy the answer? Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy . 2010;65(1):24–36. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McConeghy K. W., Bleasdale S. C., Rodvold K. A. The empirical combination of vancomycin and a β-lactam for staphylococcal bacteremia. Clinical Infectious Diseases . 2013;57(12):1760–1765. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vazquez-Guillamet C., Kollef M. H. Treatment of gram-positive infections in critically ill patients. BMC Infectious Diseases . 2014;14(1):92–98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) GoI. Directorate General of Health Services . New Delhi, India: Ministry of Health and Family; 2016. National treatment guidelines for antimicrobial use in infectious diseases-Version 1.0. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee M. S., Oh J. Y., Kang C.-I., et al. Guideline for antibiotic use in adults with community-acquired pneumonia. Infection & Chemotherapy . 2018;50(2):160–198. doi: 10.3947/ic.2018.50.2.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhagwat S. S., Nandanwar M., Kansagara A., et al. Levonadifloxacin, a novel broad-spectrum anti-MRSA benzoquinolizine quinolone agent: review of current evidence. Drug Design, Development and Therapy . 2019;13:4351–4365. doi: 10.2147/dddt.s229882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baliga S., Mamtora D. K., Gupta V., et al. Assessment of antibacterial activity of levonadifloxacin against contemporary gram-positive clinical isolates collected from various Indian hospitals using disk-diffusion assay. Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology . 2020;38(3-4):307–312. doi: 10.4103/ijmm.ijmm_20_307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bhagwat S. S., Mundkur L. A., Gupte S. V., Patel M. V., Khorakiwala H. F. The anti-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus quinolone WCK 771 has potent activity against sequentially selected mutants, has a narrow mutant selection window against quinolone-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and preferentially targets DNA gyrase. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy . 2006;50(11):3568–3579. doi: 10.1128/aac.00641-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patel A., Sangle G. V., Trivedi J., et al. Levonadifloxacin, a novel benzoquinolizine fluoroquinolone, modulates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses in human whole-blood assay and murine acute lung injury model. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy . 2020;64(5) doi: 10.1128/aac.00084-20.e00084-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kongre V., Bhagwat S., Bharadwaj R. Resistance pattern among contemporary Gram positive clinical isolates and in vitro activity of novel antibiotic, Levonadifloxacin (WCK 771) International Journal of Infectious Diseases . 2020;101:p. 30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saxena D., Kaul G., Dasgupta A., Chopra S. Levonadifloxacin arginine salt to treat MRSA infection and acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection. Drugs of Today . 2020;56(9):583–598. doi: 10.1358/dot.2020.56.9.3168445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saseedharan S., Aneja P., Chowti A., Debnath K., Mehta K. D., Sonone P. Efficacy and safety of intravenous and/or oral levonadifloxacin in the management of secondary bacterial pulmonary infections in COVID-19 patients: findings of a retrospective, real-world, multi-center study. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences . 2021;9(10):p. 2933. doi: 10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20213685. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mamtora D., Saseedharan S., Rampal R., et al. In vitro activity of a novel benzoquinolizine antibiotic, levonadifloxacin (WCK 771) against blood stream gram-positive isolates from a tertiary care hospital. Journal of Laboratory Physicians . 2020;12(3):230–232. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1720944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bozdogan B., Esel D., Whitener C., Browne F. A., Appelbaum P. C. Antibacterial susceptibility of a vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain isolated at the Hershey Medical Center. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy . 2003;52(5):864–868. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Prabhudesai D. P., Jain D. A., Borade D. P., et al. Efficacy and safety of levonadifloxacin in the management of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP): findings of a retrospective, real-world, multi-centre study. International Journal of Innovative Research in Medical Science . 2021;6(12):919–925. doi: 10.23958/ijirms/vol06-i12/1295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bhawsar S., Kale R., Deshpande P., Yeole R., Bhagwat S., Patel M. Design and synthesis of an oral prodrug alalevonadifloxacin for the treatment of MRSA infection. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters . 2021;54 doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2021.128432.128432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rodvold K. A., Gotfried M. H., Chugh R., et al. Intrapulmonary pharmacokinetics of levonadifloxacin following oral administration of alalevonadifloxacin to healthy adult subjects. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy . 2018;62(3) doi: 10.1128/aac.02297-17.e02297-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Niu J., Ivaturi V., Gobburu J., Chugh R., Bhatia A. Pharmacokinetics of intravenous WCK 771 in healthy Indian male adults. BID . 600;5:p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chugh R., Lakdavala F., Bhatia A. Twenty-Sixth European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases . Amsterdam, Netherlands: 2016. Safety and pharmacokinetics of multiple ascending doses of WCK 771 and WCK 2349. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mehrotra S., Ivaturi V., Gobburu J., Chugh R., Bhatia A. Pharmacokinetics of intravenous WCK 771 in healthy US adults. Ratio . 2015;1(10) [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chugh R., Lakdavla F., Bhagwat S., Patel L., Bhatia A. Abstr 55th Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother . Washington, DC, USA: CA American Society for Microbiology; 2015. Food effect and absolute bioavailability study of WCK 2349 and WCK 771 in healthy adult human volunteers in US, abstr A-039. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mason J. W., Chugh R., Patel A., Gutte R., Bhatia A. Electrocardiographic effects of a supratherapeutic dose of WCK 2349, a benzoquinolizine fluoroquinolone. Clinical and Translational Science . 2019;12(1):47–52. doi: 10.1111/cts.12594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bhatia A., Mastim M., Shah M., et al. Efficacy and safety of a novel broad-spectrum anti-MRSA agent levonadifloxacin compared with linezolid for acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections: a phase 3, openlabel, randomized study. Journal of the Association of Physicians of India . 2020;68(8):30–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mehta Y., Hegde A., Pande R., et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in intensive care unit setting of India: a review of clinical burden, patterns of prevalence, preventive measures, and future strategies. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine . 2020;24(1):p. 55. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kliegman R. M., Behrman R. E., Jenson H. B., Stanton B. M. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics E-Book . Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yemm K. E., Barreto J. N., Mara K. C., Dierkhising R. A., Gangat N., Tosh P. K. A comparison of levofloxacin and oral third-generation cephalosporins as antibacterial prophylaxis in acute leukaemia patients during chemotherapy-induced neutropenia. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy . 2018;73(1):204–211. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cullen M., Baijal S. Prevention of febrile neutropenia: use of prophylactic antibiotics. British Journal of Cancer . 2009;101(S1):S11–S14. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mehta K., Mehta Y., Sutar A., et al. Prescription-Event monitoring study on safety and efficacy of levonadifloxacin (oral and IV) in management of bacterial infections: findings of real-world observational study. International Journal of Applied and Basic Medical Research . 2022;12(1):p. 30. doi: 10.4103/ijabmr.ijabmr_602_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Prabhoo R., Chaddha R., Iyer R., Mehra A., Ahdal J., Jain R. Overview of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus mediated bone and joint infections in India. Orthopedic Reviews . 2019;11(2):p. 8070. doi: 10.4081/or.2019.8070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tellis M., Joseph J., Khande H., Bhagwat S., Patel M. In vitro bactericidal activity of levonadifloxacin (WCK 771) against methicillin-and quinolone-resistant Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Journal of Medical Microbiology . 2019;68(8):1129–1136. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jacobs M. R., Bajaksouzian S., Windau A., et al. In vitro activity of the new quinolone WCK 771 against staphylococci. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy . 2004;48(9):3338–3342. doi: 10.1128/aac.48.9.3338-3342.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reddy P. K. N., Sutar A., Sahu S., Thampi P. C., Keswani N., Mehta K. D. Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus-importance of appropriate empirical therapy in serious infections. International Journal of Advances in Medicine . 2021;9(1):56–65. [Google Scholar]