Abstract

Since its discovery as a third unique gaseous signal molecule, hydrogen sulfide (H2S) has been extensively employed to resist stress and control pathogens. Nevertheless, whether H2S can prevent tobacco bacterial wilt is unknown yet. We evaluated the impacts of the H2S donor sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) on the antibacterial activity, morphology, biofilm, and transcriptome of R. solanacearum to understand the effect and mechanism of NaHS on tobacco bacterial wilt. In vitro, NaHS significantly inhibited the growth of Ralstonia solanacearum and obviously altered its cell morphology. Additionally, NaHS significantly inhibited the biofilm formation and swarming motility of R. solanacearum, and reduced the population of R. solanacearum invading tobacco roots. In field experiments, the application of NaHS dramatically decreased the disease incidence and index of tobacco bacterial wilt, with a control efficiency of up to 89.49%. The application of NaHS also influenced the diversity and structure of the soil microbial community. Furthermore, NaHS markedly increased the relative abundances of beneficial microorganisms, which helps prevent tobacco bacterial wilt. These findings highlight NaHS's potential and efficacy as a powerful antibacterial agent for preventing tobacco bacterial wilt caused by R. solanacearum.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Plant sciences

Introduction

Bacterial wilt is a soil-borne disease caused by Ralstonia solanacearum that has a global impact on crop quality and productivity1–3. Bacterial wilt causes soil degradation, poor plant development, an overabundance of harmful bacteria, and breakouts of soil-borne diseases4,5. As a result, it has been attributed to a disturbed ecological balance between plants and rhizosphere microorganisms6.

Agrochemicals are frequently used to control bacterial wilt1,7. Nevertheless, excessive agrochemical use can have major adverse effects, including the spread of resistant strains and environmental threats8,9. Prevention research frequently uses agricultural controls such as resistant cultivars, crop rotation, and tillage control3,6. It is challenging to manage R. solanacearum through agricultural practices due to its protracted presence in the soil outside the host plant. Hence, there is a pressing need to create new alternative agent compounds that effectively control R. solanacearum and are environmentally friendly.

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is the third unique gaseous signal molecule used in animal physiological processes and agricultural production4,10. A large number of studies in the field of plants have shown that H2S can be directly or indirectly involved in a wide range of plant physiological processes, including stomatal movement11, photosynthesis12, seed germination13, root growth14, fruit ripening15, as well as plant senescence16. H2S can enhance plant tolerance to drought, salinity, high-temperature, and heavy metal stress by initiating plant redox signal, antioxidant capacity, and specific components of cellular defense17–20. Exogenous application of H2S induces plant cross-adaptation to multiple abiotic stresses21. Therefore, H2S, a sulfur-containing defense compound, plays an important role in plant resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses22. Previous researches have demonstrated that H2S prevents the growth of several pathogens, such as Rhizopus oryzae, Aspergillus niger, Penicillium italicum, Candida albicans, and Aspergillus niger23,24. However, it is unknown whether H2S can prevent R. solanacearum and whether it can decrease tobacco bacterial wilt (TBW) caused by the pathogen R. solanacearum.

The compound sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) is widely used as H2S donor in basic research. Upon hydrolysis, NaHS were dissociated to Na+ and HS−, and then partially binding to H+ to form H2S25. In this study, we evaluated the impacts of the H2S donor sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) on the antibacterial activity, morphology, biofilm, and transcriptome of R. solanacearum. In addition, NaHS was administered to a tobacco field infested with bacterial wilt. The effect of NaHS on disease incidence, disease index, rhizosphere soil physicochemical properties, and microbial communities was studied to determine the mechanism by which NaHS works to prevent TBW. These investigations will establish NaHS as a unique and eco-friendly antibacterial agent for the control of TBW.

Results

In vitro antibacterial activity of NaHS against R. solanacearum

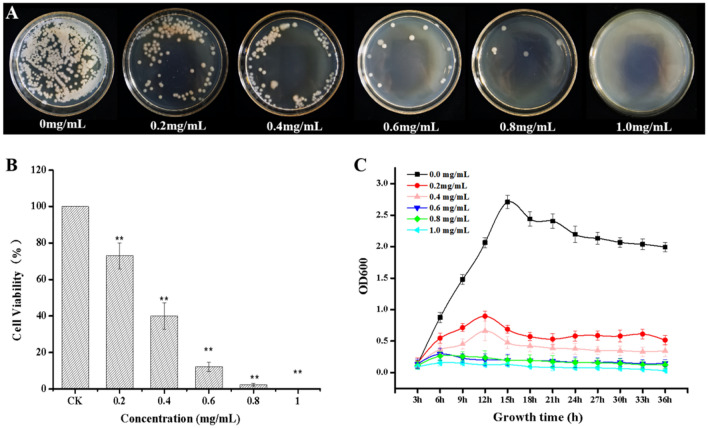

Using NA plates, different concentrations of NaHS were evaluated at 24 h to examine if they may inhibit the development of R. solanacearum (Fig. 1A). Figure 1A demonstrates how NaHS suppressed R. solanacearum growth on plates after 24 h. Additionally, the plate counting method assessed the viability of R. solanacearum (Fig. 1B). Cell viability was 73.03%, 40.01%, 12.16%, and 2.30% at amounts of 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 mg/mL, respectively. The cells displayed total inactivation and no viability following treatment with NaHS at a 1.0 mg/mL dosage. This information suggested that NaHS had an antibacterial action that varied with concentration. The growth curves also calculated NaHS's antibacterial efficacy (Fig. 1C). At concentrations of 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0 mg/mL, NaHS strongly reduced the growth of R. solanacearum, and after 12 h of incubation, the R. solanacearum growth stopped. Moreover, at concentrations of 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0 mg/mL, R. solanacearum growth was almost entirely suppressed. However, NaHS had no effect on the colony shape of R. solanacearum (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

NaHS has an antibacterial effect against R. solanacearum. (A) The growth of R. solanacearum on plates after 24 h of culture. (B) The cell viability rate of R. solanacearum. (C) The OD growth curves of R. solanacearum in the presence of different concentrations of NaHS. The error bars represent the standard deviations of three replicates, and a **p-value of < 0.01 indicates statistically significant differences based on independent-sample t-tests.

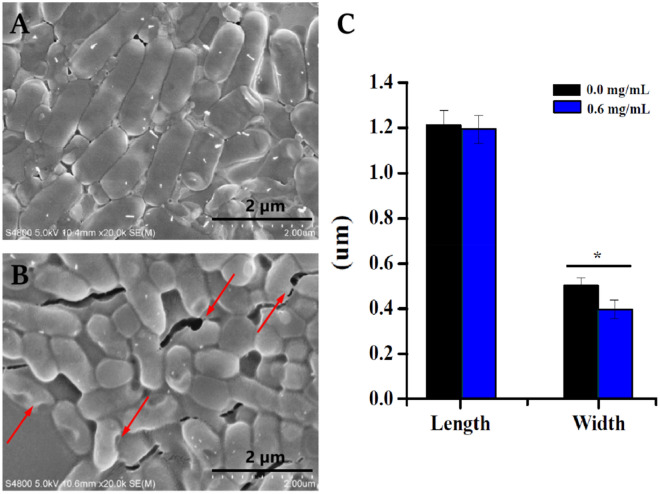

The influence of NaHS on the morphology of R. solanacearum

The cell morphology of R. solanacearum treated with 0.6 mg/mL NaHS was tracked using SEM to investigate the mechanism of antibacterial activity. Untreated R. solanacearum exhibited a long rod shape with a full membrane structure and a smooth texture (Fig. 2A). In contrast, NaHS treatment degraded the bacterial cells' surface structure and morphologies (Fig. 2B). R. solanacearum treated with 0.6 mg/mL NaHS had a shorter form than untreated R. solanacearum. In addition, treated R. solanacearum cells' diameters were much less than those of untreated R. solanacearum cells (Fig. 2C). These findings suggested that R. solanacearum morphology could be impacted by NaHS.

Figure 2.

(A) Images of R. solanacearum cells obtained by scanning electron microscopy R. solanacearum untreated. (B) R. solanacearum treated with 0.6 mg/mL of NaHS, and (C) the effects of various treatments on the length and width of R. solanacearum cells. The red arrow denotes cell membrane damage. The mean value of length and breadth was derived using the scale bars of SEM images, and * denotes statistically significant differences as determined by t-tests with a p-value of < 0.05.

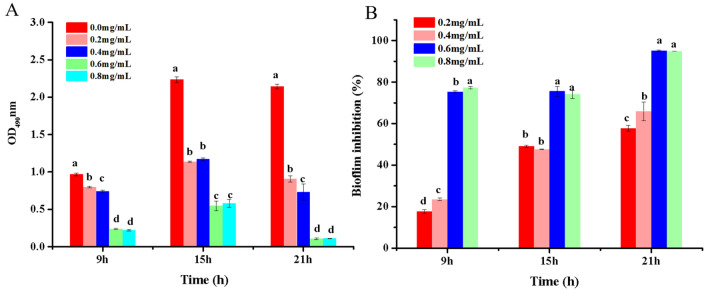

Impact of NaHS on R. solanacearum biofilm formation

After 9, 15, and 21 h, the biofilm development of R. solanacearum was examined under 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 mg/mL concentrations of NaHS (Fig. 3). The biomass climbed from 9 to 15 h and dropped from 15 to 21 h in all treatments (Fig. 3A). Biofilm formation was substantially higher in the control (0.0 mg/mL) than in the other NaHS concentrations (0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 mg/mL). Furthermore, treatments at 0.2 and 0.4 mg/mL could prevent biofilm formation, whereas treatments at 0.6 and 0.8 mg/mL substantially decrease biofilm formation. 0.6 and 0.8 mg/mL doses considerably lowered biofilm formation by 75.52% and 74.03% at 15 h and 95.05% and 94.82% at 21 h, respectively, compared to the control (Fig. 3B). All of these findings revealed that NaHS had a considerable inhibitory effect on R. Solanacearum biofilm development.

Figure 3.

(A) The effects of various concentrations of NaHS on biofilm formation in R. solanacearum. (B) The inhibitory effect of NaHS on biofilm formation in R. solanacearum. The values are expressed as mean ± SE (n = 3). By Duncan's test, bars with lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

Effects of NaHS on R. solanacearum swarming motility

In Petri dishes, the effects of NaHS on R. solanacearum swarming motility were studied. At doses ranging from 0.2 to 0.8 mg/mL after 12 and 48 h, NaHS could substantially reduce the swarming motility of R. solanacearum, as presented in Fig. 4. The migratory zone's diameter gradually shrank as the concentration of NaHS raised. Furthermore, the diameter of the migration zone was significantly reduced by the 0.6 and 0.8 mg/mL treatments, although there was no noticeable difference between the 0.6 and 0.8 mg/mL treatments (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

(A) The effects of varying concentrations of NaHS on the swarming motility of R. solanacearum. (B) The effects of different concentrations of NaHS on the colonization of tobacco roots by R. solanacearum. The values are presented as means ± SD (n = 3). In compliance with Tukey-HSD test, bars with lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

Effect of NaHS on R. solanacearum colonization in tobacco roots

Based on the results of the experiments described above, NaHS could inhibit the growth of R. solanacearum. Thus, we subsequently evaluated the effect of NaHS on the colonization of R. solanacearum in tobacco roots under hydroponic conditions. As shown in Fig. 4B, NaHS significantly decreased the population of R. solanacearum that colonized the roots of tobacco plants at concentrations ranging from 0.2 to 0.8 mg/mL.

Effects of NaHS on the transcriptome of R. solanacearum

We examined and contrasted the transcriptomes of R. solanacearum treated with 0.0 mg/mL (the control) and 0.6 mg/mL NaHS to ascertain the impact of NaHS on the gene expression profile of R. solanacearum. Figure 5 illustrates how the NaHS treatment significantly changed R. solanacearum transcriptome compared to the control. A total of 1822 genes expressed differently, with 950 exhibiting increased expression and 872 demonstrating decreased expression (Fig. 5A). The DEGs were primarily dispersed in 3 categories, including biological processes, cellular components, and molecular activities, according to GO term enrichment analysis. The catalytic activity in molecular processes was enhanced. More enriched biological processes include motility, translation, transmembrane transport, and transport (Fig. 5B). The NaHS treatment group displayed distinct expression patterns compared to the control group (Fig. 5C). The top 20 metabolic pathways were enriched in KEGG analysis for metabolic pathways, microbial metabolism in various settings, carbon metabolism, biosynthesis of secondary metabolism, and biosynthesis (Fig. 5D). It was evident that R. solanacearum pathways had changed due to NaHS treatment based on the outcomes of the volcano plots, GO, and KEGG pathway analyses.

Figure 5.

CK and NaHS transcriptomic analyses. (A) All identified genes volcano plot. (B) GO term enrichment analysis of DEGs. (C) DEG heatmaps. (D) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs. CK represents untreated R. solanacearum, while NaHS denotes R. solanacearum treated with 0.6 mg/mL NaHS.

Effects of NaHS on the incidence and index of TBW

According to the aforementioned experimental findings, NaHS can inhibit R. solanacearum. Thus, we conducted a pot experiment to establish the effects of NaHS on TBW. 10 d after inoculation, the control and NaHS treatments developed symptoms of bacterial wilt. The occurrence of TBW then increased more quickly in the control (CK) group than in the NaHS group (Table 1). When compared to 0.2 mg/mL and 0.4 mg/mL treatments from 18 to 20 days, 0.6 mg/mL and 0.8 mg/mL NaHS might considerably lower the disease incidence. The findings demonstrated that NaHS may substantially minimize the occurrence of TBW and that this incidence was considerably lower than that of the control (Table 1).

Table 1.

The effect of NaHS on the occurrence of tobacco bacterial wilt in pot experiment.

| Treatments | Disease incidence (10d) | Disease incidence (12d) | Disease incidence (14d) | Disease incidence (16d) | Disease incidence (18d) | Disease incidence (20d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 7.68 ± 1.09 a | 17.98 ± 3.41 a | 42.14 ± 6.47 a | 52.35 ± 8.94 a | 61.85 ± 7.04 a | 64.97 ± 9.46 a |

| NaHS200 | 4.36 ± 2.36 b | 9.85 ± 0.31 b | 17.69 ± 2.74 b | 19.68 ± 5.81 b | 28.19 ± 4.16 b | 31.95 ± 3.75 b |

| NaHS400 | 3.12 ± 0.14 c | 5.16 ± 0.38 c | 10.23 ± 1.64 c | 17.31 ± 3.47 b | 19.64 ± 4.75 c | 21.39 ± 2.64 c |

| NaHS600 | 2.16 ± 0.96 c | 3.93 ± 1.02 c | 5.46 ± 3.02 c | 7.38 ± 1.63 c | 8.64 ± 0.98 d | 8.93 ± 1.69 d |

| NaHS800 | 2.07 ± 0.14 c | 3.06 ± 0.84 c | 4.21 ± 1.24 c | 6.98 ± 0.21 c | 8.04 ± 0.86 d | 9.54 ± 1.01 d |

All data are presented as the mean ± SE. The different lowcase letters in the same column indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 based on LSD test among different concentrations of NaHS.

Additionally, we assessed NaHS's ability to control the bacterial wilt-infected tobacco field. Disease incidence (I) and disease index (DI) was substantially greater in the control group than in the NaHS-treated group. As the concentration of NaHS increased from 0.2 to 0.8 mg/mL, the I continuously decreased from 44.22 to 15.21%, and the DI decreased from 13.21 to 4.26%. With the increase of NaHS concentration, the control efficacy increased gradually. All the results suggested that applying NaHS reduces the I and DI of BWT, and the control efficacy of TBW is as high as 89.49% (Table 2).

Table 2.

The effect of NaHS on the occurrence of tobacco bacterial wilt in field experiment.

| Treatments | Disease incidence (%) | Disease index | Control efficacy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 89.34 ± 3.69 a | 40.56 ± 2.29 a | 0 c |

| NaHS200 | 44.22 ± 5.94 b | 13.21 ± 1.52 b | 67.46 ± 2.82 b |

| NaHS400 | 29.35 ± 6.99 c | 8.76 ± 1.10 bc | 78.41 ± 2.73 ab |

| NaHS600 | 20.58 ± 2.34 cd | 6.93 ± 1.89 c | 82.98 ± 3.32 a |

| NaHS800 | 15.21 ± 1.63 d | 4.26 ± 1.07 cd | 89.49 ± 1.23 a |

All data are presented as the mean ± SE. The different lowcase letters in the same column indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 based on LSD test among different concentrations of NaHS.

Effects of NaHS application on soil physicochemical properties

Seven physicochemical properties of the rhizosphere soil were analyzed (Table 3). The values of pH, alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen (AN), available phosphorous (AP), and organic matter (OM) were increased as the concentration of NaHS increased from 0.2 to 0.8 mg/mL. There was no significant difference in available potassium (AK) and exchangeable calcium (Ca) between NaHS treatments and CK. The results showed that applying NaHS could increase the soil pH, AN, AP, and OM. What's more, pH, AN, AP, and OM showed a significantly negative (P < 0.01) correlation with the incidence of BWT (Supplementary Table S1). These results indicated that applying NaHS may reduce the incidence of BWT by changing soil physicochemical properties.

Table 3.

The effects of different concentrations of NaHS on soil physicochemical properties.

| Treatments | pH | AN (mg/kg) | AP (mg/kg) | AK (mg/kg) | OM (%) | Ca (mg/kg) | Mg (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 5.22 ± 0.13 d | 141.58 ± 7.18 d | 75.30 ± 3.60 c | 770.44 ± 25.23 a | 2.40 ± 0.19 d | 999.04 ± 31.58 a | 128.47 ± 36.52 a |

| NaHS200 | 5.59 ± 0.15 c | 164.39 ± 3.80 c | 84.00 ± 1.24 bc | 756.87 ± 25.69 a | 3.18 ± 0.10 c | 987.96 ± 62.02 a | 123.03 ± 52.82 a |

| NaHS400 | 6.14 ± 0.07 b | 170.31 ± 3.44 bc | 85.92 ± 4.31 bc | 744.38 ± 36.12 a | 3.38 ± 0.16 bc | 990.50 ± 74.40 a | 120.25 ± 28.00 a |

| NaHS600 | 6.36 ± 0.09 ab | 184.48 ± 3.59 ab | 97.52 ± 5.88 ab | 750.69 ± 41.77 a | 3.69 ± 0.07 b | 998.58 ± 120.40 a | 112.69 ± 18.00 a |

| NaHS800 | 6.49 ± 0.06 a | 188.55 ± 6.98 a | 115.75 ± 11.42 a | 754.51 ± 8.87 a | 4.19 ± 0.13 a | 1005.04 ± 59.29 a | 103.64 ± 39.15 a |

Soil chemical properties in soils are presented as the mean ± SE. The different lowercase letters in the same column indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 based on Tukey-HSD test among different concentrations of NaHS.

Effects of NaHS application on bacterial diversity and community

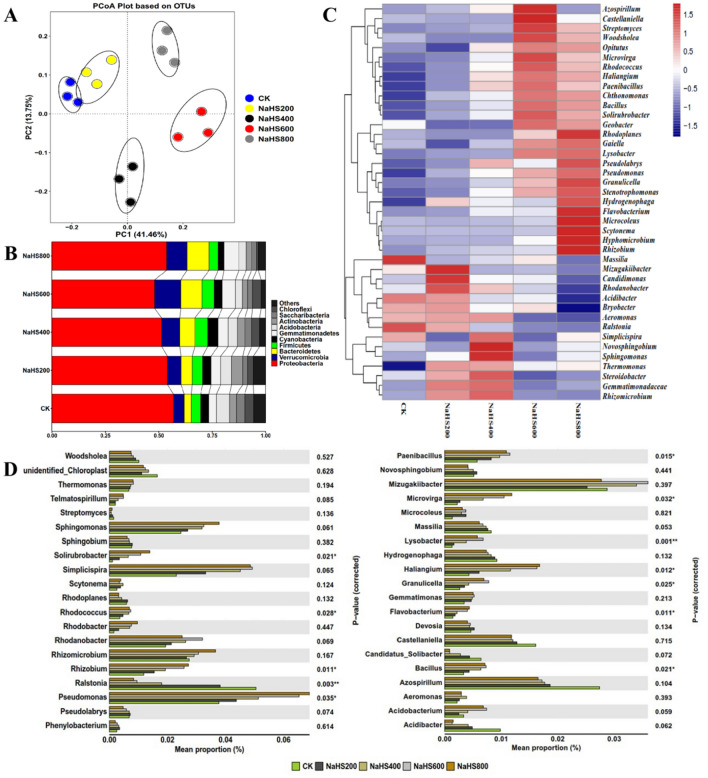

After quality filtering, a total of 679,451 high-quality raw sequences with an average length of 252 bps for bacteria were obtained from rhizospheric soil samples. The OTUs, Chao1, and Shannon index were used to evaluate and compare the richness and diversity of bacterial communities among different treatments (Supplementary Table S2). The OTUs, Chao1, and Shannon index in NaHS200 and CK treatments in the rhizosphere soil were insignificant. While the OTUs, Chao1, and Shannon index of NaHS400, NaHS600, and NaHS800 treatments were significantly lower than NaHS200 and CK treatments. With the increase of NaHS concentration from 0.2 to 0.6 mg/mL, the OTUs and Chao1 decreased gradually (Supplementary Table S2). This result suggested that applying NaHS could change the richness and diversity of the soil bacterial community.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was carried out using weighted UniFrac distance in different treatments, and PC1 and PC2 explained 55.21% of the total bacterial community. Bacterial communities from CK and NaHS200 were clustered together. In contrast, the CK, NaHS400, NaHS600, and NaHS800 were separated (Fig. 6A). This result indicated that NaHS400, NaHS600, and NaHS800 treatments' bacterial community structure was different from CK. A total of 50 bacterial phyla were identified from all soil samples. The top ten abundant bacterial phyla were selected to compare the five treatments' bacterial community changes in rhizosphere soil. The relative abundance of the top ten predominant phyla totaled up to 94.27–97.87% (Fig. 6B). Among the top ten bacterial phyla, Proteobacteria included the pathogen R. solanacearum was the most dominant (48.01–56.91%), and followed by Verrucomicrobia (5.02–12.25%), Bacteroidetes (3.28–10.33%), Firmicutes (4.24–5.92%), Gemmatimonadetes (3.55–6.94%), Acidobacteria (3.24–6.13%), Actinobacteria (2.24–5.28%), Saccharibacteria (2.24–3.84%), Cyanobacteria (2.74–4.89%) and Chloroflexi (0.92–4.23%). The relative abundance of Proteobacteria in NaHS800 treatment was lower than in other treatments. In comparison, the relative abundance of Verrucomicrobia and Bacteroidetes was higher than that in other treatments (Fig. 6B). The heatmap analysis of the top 40 genera with hierarchical clusters was used to identify the different compositions of bacterial community structure. There were distinctions in bacterial community structures among different treatments in the heatmap. Compared to the CK, the relative abundances of Streptomyces, Woodsholea, Microvirga, Rhodococcus, Haliangium, Chthonomonas, Bacillus, Solirubrobacter, Geobacter, Rhodoplanes, Gaiella, Lysobacter, Pseudomonas, Granulicella, Stenotrophomonas, Flavobacterium and Rhizobium in NaHS600 and NaHS800 treatments significantly increased. (Fig. 6C). The application of NaHS significantly decreased the relative abundances of Massilia, Acidibacter, and Ralstonia (pathogen of bacterial wilt). These results suggested that NaHS application influences the structure of the bacterial community.

Figure 6.

Bacterial community in the soil after five treatments. (A) The principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the soil bacterial community. (B) The relative abundance of bacterial phyla in soil samples. (C) A hierarchical cluster analysis of the top 40 classified bacterial genera and (D) The relative abundances of the top 40 classified bacterial genera among different treatments are all shown. The relative abundance of several taxa was examined using one-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (CK is 0.0 mg/mL NaHS, NaHS200 is 0.2 mg/mL NaHS, NaHS400 is 0.4 mg/mL NaHS, NaHS600 is 0.6 mg/mL NaHS, and NaHS800 is 0.8 mg/mL NaHS).

Further analyses were carried out at the genus level. The different distributions of the top forty abundant bacterial genera among the five treatments were illustrated in Fig. 6. Twelve varied among the five treatments were significantly different, including Solirubrobacter, Rhodococcus, Rhizobium, Ralstonia, Pseudomonas, Paenibacillus, Microvirga, Lysobacter, Haliangium, Granulicella, Flavobacterium, and Bacillus. The genus Solirubrobacter, Rhodococcus, Rhizobium, Pseudomonas, Paenibacillus, Microvirga, Lysobacter, Haliangium, Granulicella, Flavobacterium, and Bacillus were dominant in NaHS treatments and occupied a low percentage in CK (Fig. 6D). In contrast, Ralstonia was dominant in CK and decreased significantly in NaHS treatments (Fig. 6D).

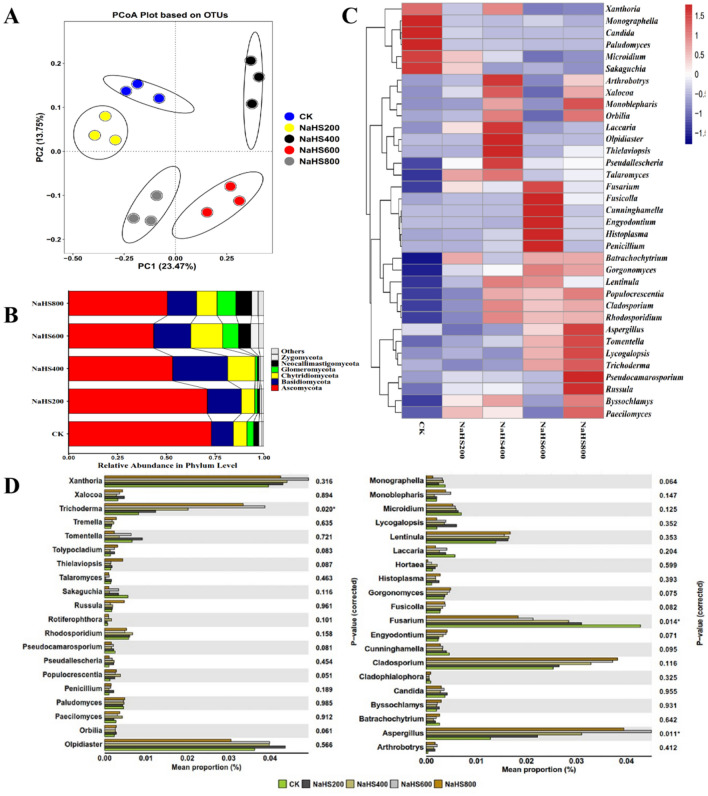

Effects of NaHS application on fungal diversity and community

The difference between the OTUs, Chao1, and Shannon fungal community index among different treatments was also analyzed (Supplementary Table S2). There was no significant difference in OTUs, Shannon, and Chao1 indexes between CK and NaHS 200. With an increase in NaHS concentration from 0.4 to 0.8 mg/mL, the OTUs, Chao1, and Shannon index were reduced significantly. The results showed that NaHS application could impact the diversity and richness of soil fungi.

According to PCoA analysis, PC1 and PC2 explained 23.47% and 13.75% of the total fungal community variations, respectively (Fig. 7A). The distribution of fungi among different treatments was relatively discrete, indicating obvious differences in the fungal community structure among different treatments. Top six fungal phyla were identified from all soil samples, including Ascomycota (43.56–73.45%), followed by Basidiomycota (7.98–28.21%), Chytridiomycota (6.84–30.15%), Glomeromycota (1.00–8.16%), Neocallimastigomycota (0.05–6.19%) and Zygomycota (0.66–9.31%) (Fig. 7B). The relative abundance of Ascomycota decreased as the concentration of NaHS increased from 200 to 600 mg/L. The relative abundance of Basidiomycota, Glomeromycota, Chytridiomycota, and Zygomycota also varies with the concentration of NaHS. These results indicated that NaHS altered the fungal community composition associated with NaHS concentration. In the heatmap for the fungal community, the relative abundance of Monograpella, Candida, Paludomyces, Microidium, and Sakaguchia in CK was significantly higher than in NaHS treatment. NaHS800 significantly enriched the relative abundance of Batrachochytrium, Gorgonomyces, Populocrescentia, Cladosporium, Rhodosporidium, Aspergillus, Tomentella, Lycogalopsis, Trichoderma, Pseudocamarosporium, Russula, Byssochlamys, and Paecilomyces (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7.

Soil fungi in five different treatments. (A) The relative abundance of bacterial phyla in soil samples. (B) The principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the soil fungal community. (C) The hierarchical cluster analysis of the most common fungal genera and (D) the relative abundances of the top 40 classified fungal genera among various treatments. Different genera abundances were examined using a one-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (CK: 0.0 mg/mL NaHS, 0.2 mg/mL NaHS, 0.4 mg/mL NaHS, 0.6 mg/mL NaHS, and 0.8 mg/mL NaHS for NaHS200, 400, 600, and 800).

The distributions of the top forty abundant fungi at the genus level among the five treatments were analyzed (Fig. 7D). Three were significantly different among the five treatments, including Trichoderma, Fusarium, and Aspergillus. Genus Trichoderma and Aspergillus were dominant in NaHS and occupied a low percentage in CK (Fig. 7D). In contrast, Fusarium was dominant in CK and decreased significantly in NaHS treatments (Fig. 7D).

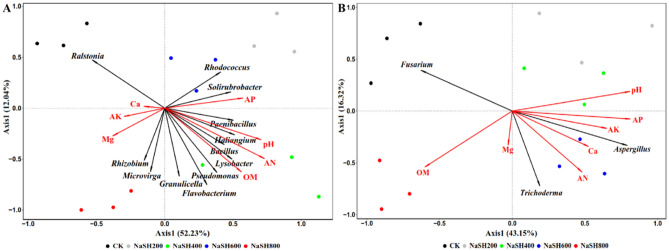

Relationship between rhizosphere soil physicochemical properties and microbial community

The relationship between rhizosphere soil physicochemical properties and microbial community structure was analyzed by redundancy analysis (RDA). The results showed 64.27% and 59.47% of bacterial and fungal community variation, respectively (Fig. 8). The bacterial Rhodococcus, Solirubrobacter, Paenibacillus, and Haliangium, Bacillus, Lysobacter, Pseudomonas, Flavobacterium, and Granulicella were positively correlated with pH, AN, AP, and OM. While, Ralstonia presented contrasting behavior negatively associated with pH, AN, AP, and OM, as shown in Fig. 8A. Trichoderma and Aspergillus were positively linked with AN, Ca, AK, AP, and pH. On the other hand, Fusarium negatively correlated with AN, Ca, AK, AP, and pH (Fig. 8B). The redundancy analysis revealed that rhizosphere soil AN, Ca, AK, AP, and pH greatly influenced the microbial community.

Figure 8.

Analysis of duplication between soil physicochemical characteristics and rhizosphere microbial community. (A) Bacterial and (B) fungal communities. (CK is 0.0 mg/mL NaHS, NaHS200 is 0.2 mg/mL NaHS, NaHS400 is 0.4 mg/mL NaHS, NaHS600 is 0.6 mg/mL NaHS, and NaHS800 is 0.8 mg/mL NaHS).

Discussion

In this study. We determined that NaHS greatly decreased R. solanacearum growth and affected its morphology, biofilm, and transcriptome (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5). Furthermore, NaHS treatment might regulate TBW (Tables 1, 2), change soil physicochemical parameters (Table 3), and regulate the soil microbial community (Figs. 6, 7, 8).

H2S possesses several biological activities, including cell signaling and antibacterial and antifungal properties23,24,26. Our findings demonstrated that NaHS is a powerful antibacterial agent against R. solanacearum (Fig. 1). According to the SEM results, NaHS may disrupt the cell morphology, resulting in the death of R. solanacearum (Fig. 2). As per earlier research, several antibacterial agents target the cell membrane first and then inhibit R. solanacearum by destroying the cell membrane21,27. Furthermore, we observed that NaHS prevented R. solanacearum biofilm formation, swarming motility, and colonization ability (Figs. 3, 4), similar to prior work28. We investigated the transcriptome of R. solanacearum better to study the antibacterial mechanism of NaHS against R. solanacearum. In NaHS-treated R. solanacearum, 1822 genes are engaged, with 950 up-regulated and 872 down-regulated (Fig. 6). The transcriptome of R. solanacearum is dramatically altered by NaHS treatment. These data suggested that NaHS are involved in antibacterial activity.

Antibacterial drugs are an effective technique to control pathogens. Lysine had a controlled efficacy of 58–100% on tomato bacterial wilt in pot experiments29. Hydroxycoumarins can potentially reduce TBW by 38.27–80.03%30. In this investigation, we discovered that using NaHS may effectively prevent TBW, with control efficacy reaching 89.49% in the field experiment (Table 2). According to the findings, NaHS could be employed as an antibacterial agent to control TBW.

Since researchers indicated that the exogenous application of H2S can affect plant growth by altering soil nutrient content31,32, in our study, the application of NaHS also increased soil pH, AN, AP, and OM values (Table 3). Increased pH is important for inhibiting the survival of R. solanacearum and increasing OM, N, and P to meet the needs of plant growth33,34. In addition, the higher soil phosphorus could increase the activity of beneficial microorganisms against the pathogen34. This study demonstrated that the application of NaHS significantly reduced the disease incidence and disease index of TBW, and pH, AN, AP, and OM showed a significantly negative correlation with the incidence of TBW (Table 2, Supplementary Table S1). It was hypothesized that administering NaHS could also modify the physicochemical features of the soil.

The rhizosphere soil microbial community structure influences the plant's immunity and quality, and the microbial community is considered a key mechanism that can suppress soil-borne pathogens35,36. Our findings explored that applying NaHS altered the diversity and richness of soil microbes (Supplementary Table S2), which was consistent with the results of Fang et al.32. The microbial analysis revealed a different treatment pattern (Figs. 6A, 7A). NaHS application significantly influenced the composition of the soil microbial community (Figs. 6, 7). NaHS treatments reduced the relative abundance of Proteobacteria (Fig. 6B), which was similar to the results by Li et al.35. The phylum Proteobacteria including the pathogen R. solanacearum, is less abundant in healthy soils than in bacterial wilt soil35. NaHS treatments also reduced the relative abundance of Acidobacteria (Fig. 6B). Acidobacteria was mainly driven by soil pH, and the low pH was more suitable for the survival of Acidobacteria37. Our results also showed that the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes was increased in NaHS treatments (Fig. 6B), which could promote plant growth and improve the resistance of plants to environmental stress38. The heatmap based on significant changes indicated that NaHS application increased the abundances of some bacteria and fungi (such as Paenibacillus, Bacillus, Lysobacter, Aspergillus, and Trichoderma, etc). (Figs. 6C, 7C). These microorganisms are recognized as beneficial microorganisms, and their functions may be related to soil physicochemical properties, accelerating the cycling of elements, promoting plant growth, and environmental adaption39–42.

In the present investigation, specific genera of microorganisms of Solirubrobacter, Rhodococcus, Rhizobium, Pseudomonas, Paenibacillus, Microvirga, Lysobacter, Haliangium, Granulicella, Flavobacterium, Bacillus, Trichoderma, and Aspergillus were significantly high in NaHS treatments. However, Ralstonia and Fusarium were significantly low in NaHS treatments (Figs. 6D, 7D). The genus Ralstonia includes many soil-borne pathogens, which only infect roots via wounds caused by microbes and insects43. Pathogenic Fusarium can infect the root by penetrating hyphae, causing more wounds to the root, thus increasing the root infection by pathogenic Ralstonia44. The application of NaHS could inhibit bacterial wilts caused by pathogenic Ralstonia. Some species of Solirubrobacter and Granulicella positively affect the soil's organic carbon transition45. Rhodococcus and Bacillus were reported as phosphate-mobilizing bacteria, which can solubilize organic and inorganic phosphate46. Furthermore, some species of the genus Bacillus can affect the growth and virulence traits of Ralstonia by producing volatile organic compounds41. Pseudomonas promotes plant growth, inhibits pathogens, and induces systemic resistance to diseases in many plants47. Microvirga is a nitrogen-fixing bacteria that can be involved in nitrogen cycling46. Previous studies have documented that Pseudomonas, Rhizobium, Paenibacillus, Lysobacter, Haliangium, Flavobacterium, and Bacillus, as antagonistic bacteria, can mitigate many soil-borne diseases and promote plant growth and health40,41,48,49. Trichoderma and Aspergillus have been reported as antagonistic fungi. They directly interact with roots to produce bioactive substances, improve plant growth, and resist abiotic and biotic stress40,42. The application of NaHS may provide a suitable environment for promoting the growth of these beneficial microorganisms, increasing the relative abundance of these beneficial microorganisms, and reducing the incidence of BWT. The redundancy analysis (RDA) revealed that these beneficial microorganisms were positively correlated with pH, AN, and AP, whereas Ralstonia was negatively correlated with pH, AN, and AP (Fig. 8).

In this study, we revealed that NaHS considerably reduced the growth of R. solanacearum in the root by controlling the root's biofilm production, transcriptome, and colonization. Similarly, the occurrence and disease index of TBW decreased dramatically through using NaHS. Moreover, the exogenous application of NaHS can affect the soil's physiochemical properties and influence the constitution and arrangement of the soil's microbial population, contributing to the management of TBW. These results might offer empirical and theoretical justification for NaHS-mediated TBW control. Future studies are expected to evaluated the effect of NaHS on the expression of biofilm formation-related genes and virulence-associated genes of R. solanacearum.

Materials and methods

Tobacco materials, bacterial strains, culture conditions, and reagents

The Tobacco Research Institute of Hubei in Wuhan, China, provided the Yunyan87 for this study. The R. solanacearum (phylotype I, race 1, biovar III) was used in this study50. R. solanacearum was routinely grown on a semisolid medium containing 0.35% agar, nutrient broth medium (NB), and nutrient agar (NA) medium. For hydroponic tobacco, Murashige and Skoog (MS) media was utilized. NaHS was acquired from Aladdin Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) for use in this study.

Evaluating NaHS antibacterial activity against R. solanacearum in vitro

Agar dilution assays and growth curves at various doses were used to assess the influence of NaHS on the growth of R. solanacearum. 100 µL of newly developed R. solanacearum suspension (1 × 109 CFU/mL) was disseminated directly onto NA plates with varying concentrations (0.0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0 mg/mL) of NaHS. The plates were incubated at 28 ± 1 °C for 24 h to count the colonies. The viability of the R. solanacearum cell was then measured by counting CFU on the agar plates. Cell viability (%) = V′/V × 100% formula was used to calculate the viability of the cells, where V′ and V stand for the number of colony-forming units on the control plates (0.0 mg/mL NaHS) and NaHS (0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0 mg/mL) plates, respectively.

The R. solanacearum was freshly cultured in a suspension, and 100 µL of that suspension (1 × 109 CFU/mL) was transferred to NB medium with various NaHS concentrations (0.0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0 mg/mL). The cultures were incubated at 30 °C for 36 h while shaken at 180 rpm. The optical density of 600 nm (OD600) was measured every 3 h using a Nicolet Evolution 300 UV–Vis spectrometer to obtain the growth curves. Each treatment was carried out three times and calculated to obtain an average value.

The influence of NaHS on the morphology of R. solanacearum

A scanning electron microscope (SEM) was used to examine the morphology of R. solanacearum cells in the presence of NaHS. R. solanacearum was diluted in NB medium to 1 × 109 CFU/mL solution. NaHS was added to the suspension of R. solanacearum at a final concentration of 0.6 mg/mL. The medium devoid of NaHS served as the control. The cultures were incubated at 30 °C for 12 h with 180 rpm shaking. After 12 h, the cells of R. solanacearum were removed by centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 5 min, washed three times with 0.1 mol/L pH 7.0 phosphate buffer, and fixed with 2.5% of glutaraldehyde overnight at 4 °C. The SEM analysis was performed as described by Li et al.21.

Effect of NaHS on biofilm formation of R. solanacearum

Ralstonia solanacearum biofilm formation was assessed using crystal violet staining, as outlined by Peeters et al.51, with minor modifications. The experiment was carried out in 96-well microtiter plates. To induce biofilm growth, 100 L of mixed cultures (10 µL of inoculum (OD600 ≈ 1.0) mixed with a final NaHS concentration of 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 mg/mL in NB medium) were inoculated into individual wells of a 96-well microtiter plate. The plates were wrapped with cling wrap and incubated at 30 °C without shaking for 9, 15, and 21 h before the liquid medium was withdrawn, and the plates were rinsed three times with distilled water. Each well was stained for 30 min with 0.1% crystal violet, followed by three washes with water to eliminate any remaining stain. 200 µL of 95% ethanol was used to remove the crystal violet, and then a microplate reader was used to measure the biofilm's absorbance at 490 nm. The experiment was carried out in triplicate, with each treatment repeated three times.

Effect of NaHS on swarming motility of R. solanacearum

With slight modifications, the swarming assay was based on Tans-Kersten et al.52. study. In Petri dishes, a semisolid medium containing 0.35% agar and NaHS at various doses (0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 mg/mL) was added before being air-dried. The OD600 ≈ 0.8 R. solanacearum overnight culture was collected, twice washed in sterile water at 6000 rpm for five minutes, and then resuspended in sterile water. Drop-inoculated 2 µL of R. solanacearum suspension onto the center of plates. They were then incubated at 30 °C for 12 and 48 h. On each plate, the colony diameters were measured in both the vertical and horizontal directions. Each assay was carried out three times. The average of three separate experiments was used to express the outcomes.

Evaluation of R. solanacearum colonization in tobacco roots

A hydroponic experiment and plate counts were used to assess R. solanacearum colonization. Tobacco seedlings were rinsed three times with distilled water after reaching the 4–5 leaf stage, and tobacco roots were immersed in different concentrations of NaHS (0.0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0 mg/mL) for 30 min. The treated tobacco seedlings were grown in MS medium with 1 mL of R. solanacearum (1 × 109 CFU/mL) added as an inoculant. The population of R. solanacearum adhering to the tobacco root was identified after 3 days of incubation in a greenhouse at 28 ± 1 °C with 85–90% relative humidity. The tobacco roots were cut out, submerged in 75% ethanol for 15 min, and then rinsed in sterile water. Each treated 1 g root was blotted dry before being pulverized in a mortar with 5 mL sterile water until finely homogenized. 1 mL of the supernatant was then collected as the bacterial suspension in the plant roots. The suspension was then sub-cultured and evenly placed onto NA medium before being maintained for 48 h at 30 °C. To determine the amount of R. solanacearum in tobacco roots per unit weight, the strains were then characterized, and the colonies were counted. At least three times were given for each treatment independently.

Transcriptome analysis

Using a mirVana miRNA isolation kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA), total RNA from R. solanacearum treated with 0.0 (the control) and 0.6 mg/mL NaHS was extracted as recommended by the manufacturer. Using a Nano 6000 Assay Kit from the Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA), the concentration and quality of the RNA were evaluated. Consequently, NEBNext® UltraTM Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (NEB, USA) was used to prepare 3 µg of total RNA from each sample following the manufacturer's instructions. The samples were sequenced on the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system after synthesizing the first and second strand complementary cDNA. The readings were approximately 150 bp in length. FastQC was used to check the quality of the raw RNA-Seq data53. The R. solanacearum reference genome (NZ CP016914.1) was obtained from GeneBank, and Bowtie2-2.2.3 was used to align the reads to the reference genome sequences54. HTSeq v0.6.1 was used to count the number of reads aligned to each gene, and the FPKM of the genes was calculated using both gene lengths and the number of reads mapped55. The DESeq R package (1.18.0) was used to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Gene Ontology (GO) was confirmed to be considerably enriched at p < 0.05 using the GOseq program in R56. Using KOBAS software (KOBAS, Surrey, UK), the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis was performed, and the pathway with a corrected p < 0.05 was regarded as significantly enriched in DEGs57. Transcriptome analysis was carried out using 2 samples for each of the 3 biological replications per sample.

Indoor pot and field experiments

An indoor pot experiment in the greenhouse was conducted to assess the control efficacy of NaHS on TBW. When tobacco seedlings reached the 4–5 leaf stage, the rhizosphere was infected with 1 mL of fresh R. solanacearum suspension (1 × 109 CFU/mL). Two days after R. solanacearum inoculation, 10 mL of NaHS in various doses (0.0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0 mg/mL) was irrigated onto the tobacco roots. Tobacco seedlings injected with bacteria were grown in a greenhouse at 28 ± 1 °C and 85–90% relative humidity. Each treatment had three replicates, each one with 30 plants. Every 2 days, the disease's progression was recorded.

The field experiment was performed in tobacco fields with 15 years of continuous cropping tobacco fields in Xuan'en County (109°26′ E, 29°59′ N), Enshi City, Hubei province, China, from April to September 2019. TBW incidence has been higher than 95% yearly for the past 5 years58 when tobacco seedlings with 4–5 leaves were transplanted into the field. The experimental design consisted of three blocks, each 200 m2 in size, and each block was divided into five plots of 40 m2, with 60 plants in each plot. Five treatments with three replicates in completely randomized blocks were established. The treatments were: (1) control, 0.0 mg/mL NaHS (CK); (2) 50 mL, 0.2 mg/mL NaHS (NaHS200); (3) 50 mL, 0.4 mg/mL NaHS (NaHS400); (4) 50 mL, 0.6 mg/mL NaHS (NaHS600); (5) 50 mL, 0.8 mg/L NaHS (NaHS800). NaHS was applied to each tobacco root during transplantation. The planting density of all treatments was the same. TBW symptoms were tracked from 30 to 100 days after transplantation.

A prior study described the TBW disease index (DI) based on a severity scale of 0–921. The TBW disease incidence (I) and disease index (DI) was calculated as follows: I = n/N × 100%, and DI = ∑(r × n′)/(N × 9) × 100, where "n" represents the total number of infected tobacco plants and "N" refers to the total number of plants, "r" represents the disease severity rating scale, and "n′" is the number of infected tobacco plants with a rating of r. Control efficiency = [(I of control − I of treatment)/I of control] × 100%.

Soil sample collection and physicochemical properties analysis of rhizosphere

Rhizosphere soils were collected by the five-spot-sampling method at 50 d, 70 d, and 90 d post-transplantation58. Then the soil samples from the five separate sites were mixed into one soil sample and partitioned into two subsamples, one was immediately transported on ice to the laboratory and stored at − 80 °C for genomic DNA extraction, and the other subsamples were air-dried for physicochemical properties analysis. The analysis of soil pH, alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen (AN), available phosphorus (AP), available potassium (AK), organic matter (OM), exchangeable calcium (Ca), and exchangeable magnesium (Mg) was performed according to Hu et al.59.

Rhizosphere soil microbial community analysis

DNA was extracted from 0.5 g rhizosphere soil using the FastDNA Spin Kit (MP Biomedicals, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol. The integrity of DNA samples was determined by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. Then the concentration and purity of the DNA were determined using a Nanodrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA).

The extracted DNA from each soil sample was used as a template for amplification. The V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA genes and the ITS1 regions of the fungal rRNA genes were amplified. Each DNA sample was amplified separately using the following primers: Forward, 515F; (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′), and Reverse, 806R; (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) for bacterial60. Forward, ITS5-1737F; (5′-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3′) and Reverse, ITS2-2043R; (5′-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3′) for fungi61. All PCR reactions were performed on Illumina HiSeq platforms (Illumina Inc., USA) at Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). The library quality was assessed on the Qubit@ 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Scientific) and the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system. CASAVA1.8 statistically analyzed the sequence quality. The raw sequence data was filtrated using the FASTX Toolkit 0.0.13 software package. That removed the low mass base at the tail of the sequence (Q value < 20) and the sequences with lengths < 35 bp. Finally, the obtained size of the amplicon reads was approximately 250 bp. All effective tags of all samples were clustered using Uparse software (V7.0.1001, http://drive5.com/uparse/). Sequences with ≥ 99.5% identity for 16S rDNA and sequences with ≥ 97% identity for ITS were assigned to the same OTUs (operational taxonomic units). The OTUs, Chao1, and Shannon index were calculated with QIIME (Version 1.7.0) to evaluate the richness and diversity of soil microbial community62.

Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), the least significant difference (LSD) test, Tukey-HSD test, Duncan's test, and independent-sample t-tests with p values of < 0.05 and < 0.01 were used to analyze the data among the treatments. The statistical evaluations utilized SPSS version 18.0 (IBM, United States). The correlation analysis was conducted using the Pearson 2-tailed correlation test. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) with the weighted Unifrac distance and redundancy analysis (RDA) was carried out using R (Version 2.15.3).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the key technology projects of CNTC (No. 110202101059(XJ-08), the key technology projects of Hubei tobacco companies (No. 027Y2021-001), the Science and Technology Research Project of the Education Department of Hubei Province (D20201003), and Wuhan key research and development project (2022023102015166).

Author contributions

Y.H. and J.Y. conceived and designed the experiments. D.W., Q.G. and W.Z. performed the experiments. D.W., Y.Y. and C.Y. analyzed the data. D.W., J.Y. and Y.H. wrote and revised the paper. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Dingxin Wen and Qingqing Guo.

Contributor Information

Chunlei Yang, Email: ycl193737@163.com.

Jun Yu, Email: yujun80324@163.com.

Yun Hu, Email: huyun@hubu.edu.cn.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-26697-8.

References

- 1.Nion YA, Toyota K. Recent trends in control methods for bacterial wilt diseases caused by Ralstonia solanacearum. Microbes Environ. 2015;30:1–11. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME14144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wicker E, Grassart L, Coranson-Beaudu R, Mian D, Guilbaud C, Fegan M, Prior P. Ralstonia solanacearum strains from Martinique (French West Indies) exhibiting a new pathogenic potential. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:6790–6801. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00841-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gamliel A, Austerweil M, Kritzman G. Non-chemical approach to soilborne pest management—Organic amendments. Crop Prot. 2000;19:847–853. doi: 10.1016/S0261-2194(00)00112-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodwin LR, Francom D, Dieken FP, Taylor JD, Warenycia MW, Reiffenstein RJ, Dowling G. Determination of sulfide in brain tissue by gas dialysis/ion chromatography: Postmortem studies and two case reports. J. Anal. Toxicol. 1989;13:105–109. doi: 10.1093/jat/13.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aroca A, Gotor C, Bassham DC, Romero LC. Hydrogen sulfide: From a toxic molecule to a key molecule of cell life. Antioxidants. 2020;9:621. doi: 10.3390/antiox9070621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bai W, Kong F, Lin Y, Zhang C. Extract of syringa oblata: A new biocontrol agent against tobacco bacterial wilt caused by Ralstonia solanacearum. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2016;134:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schreinemachers P, Tipraqsa P. Agricultural pesticides and land use intensification in high, middle and low income countries. Food Policy. 2012;37:616–626. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2012.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perera-Rios, J. et al. Agricultural pesticide residues in water from a karstic aquifer in Yucatan, Mexico, pose a risk to children's health. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 1–15 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Negatu B, Dugassa S, Mekonnen Y. Environmental and health risks of pesticide use in Ethiopia. J. Health Pollut. 2021;11:210601. doi: 10.5696/2156-9614-11.30.210601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corpas FJ, Palma JM. H2S signaling in plants and applications in agriculture. J. Adv. Res. 2020;24:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dooley FD, Nair SP, Ward PD. Increased growth and germination success in plants following hydrogen sulfide administration. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e62048. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, Wu FH, Wang WH, Zheng CJ, Lin GH, Dong XJ, He JX, Pei ZM, Zheng HL. Hydrogen sulphide enhances photosynthesis through promoting chloroplast biogenesis, photosynthetic enzyme expression, and thiol redox modification in Spinacia oleracea seedlings. J. Exp. Bot. 2011;62:4481–4493. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang H, Hu LY, Hu KD, He YD, Wang SH, Luo JP. Hydrogen sulfide promotes wheat seed germination and alleviates oxidative damage against copper stress. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2008;50:1518–1529. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin YT, Li MY, Cui WT, Lu W, Shen WB. Haem oxygenase-1 is involved in hydrogen sulfide-induced cucumber adventitious root formation. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2012;31:519–528. doi: 10.1007/s00344-012-9262-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ge Y, Hu KD, Wang SS, Hu LY, Chen XY, Li YH, Yang Y, Yang F, Zhang H. Hydrogen sulfide alleviates postharvest ripening and senescence of banana by antagonizing the effect of ethylene. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0191351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alvarez C, García I, Moreno I, Pérez-Pérez ME, Crespo JL, Romero LC, Gotor C. Cysteine-generated sulfide in the cytosol negatively regulates autophagy and modulates the transcriptional profile in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:4621–4634. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.105403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fotopoulos V, Christou A, Manganaris G. Hydrogen sulfide as a potent regulator of plant responses to abiotic stress factors. In: Gaur RK, Sharma P, editors. Molecular Approaches in Plant Abiotic Stress. CRC Press; 2013. pp. 353–373. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun J, Wang RG, Zhang X, Yu YC, Zhao R, Li ZY, Chen SL. Hydrogen sulfide alleviates cadmium toxicity through regulations of cadmium transport across the plasma and vacuolar membranes in Populus euphratica cells. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2013;65:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.García-Mata C, Lamattina L. Hydrogen sulphide, a novel gasotransmitter involved in guard cell signalling. New Phytol. 2010;188:977–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li J, Yu Z, Choo S, Zhao J, Wang Z, Xie R. Chemico-proteomics reveal the enhancement of salt tolerance in an invasive plant species via H2S signaling. ACS Omega. 2020;5:14575–14585. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c01275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li ZG, Min X, Zhou ZH. Hydrogen sulfide: A signal molecule in plant cross-adaptation. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:1621. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi HT, Ye TT, Han N, Bian HW, Liu XD, Chan ZL. Hydrogen sulfide regulates abiotic stress tolerance and biotic stress resistance in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2015;57:628–640. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu LH, Hu KD, Hu LY, Li YH, Hu LB, Yan H, Liu YS, Zhang H. An antifungal role of hydrogen sulfide on the postharvest pathogens Aspergillus niger and Penicillium italicum. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e104206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng H, Zhang YX, Palmer LD, Kehl-Fie TE, Skaar EP, Trinidad JC, Giedroc DP. Hydrogen sulfide and reactive sulfur species impact proteome S-sulfhydration and global virulence regulation in Staphylococcus aureus. ACS Infect. Dis. 2017;3:744–755. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowicka E, Beltowski J. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S)—the third gas of interest for pharmacologists. Pharmacol. Rep. 2007;59:4–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szabo C. A timeline of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) research: From environmental toxin to biological mediator. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018;149:5–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen JN, Yu YM, Li SL, Ding W. Resveratrol and coumarin: Novel agricultural antibacterial agent against Ralstonia solanacearum in vitro and in vivo. Molecules. 2016;21:1501. doi: 10.3390/molecules21111501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li SL, Pi J, Zhu H, Yang L, Zhang XG, Ding W. Caffeic acid in tobacco root exudate defends tobacco plants from infection by Ralstonia solanacearum. Front. Plant Sci. 2021;12:690586. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.690586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Posas MB, Toyota K, Islam TMD. Inhibition of bacterial wilt of tomato caused by Ralstonia solanacearum by sugars and amino acids. Microbes Environ. 2007;22:290–296. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.22.290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang L, Ding W, Xu YQ, Wu DS, Li SL, Chen JN, Guo B. New insights into the antibacterial activity of hydroxycoumarins against Ralstonia solanacearum. Molecules. 2016;21:468. doi: 10.3390/molecules21040468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ju W, Liu L, Fang L, Cui Y, Duan C, Wu H. Impact of co-inoculation with plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria and rhizobium on the biochemical responses of alfalfa-soil system in copper contaminated soil. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019;167:218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fang LC, Ju WL, Yang CL, Jin XL, Liu DD, Li MD, Yu JL, Zhao W, Zhang C. Exogenous application of signaling molecules to enhance the resistance of legume-rhizobium symbiosis in Pb/Cd-contaminated soils. Environ. Pollut. 2020;265:114744. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He K, Yang SY, Li H, Wang H, Li ZL. Effects of calcium carbonate on the survival of Ralstonia solanacearum in soil and control of tobacco bacterial wilt. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2014;140:665–675. doi: 10.1007/s10658-014-0496-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen S, Qi GF, Ma GQ, Zhao XY. Biochar amendment controlled bacterial wilt through changing soil chemical properties and microbial community. Microbiol. Res. 2020;231:126373. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2019.126373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li JG, Ren GD, Jia ZJ, Dong YH. Composition and activity of rhizosphere microbial communities associated with healthy and diseased greenhouse tomatoes. Plant Soil. 2014;380:337–347. doi: 10.1007/s11104-014-2097-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rasuk MC, Fernández BA, Kurth D, Contreras M, Novoa F, Poiré D, Farías ME. Bacterial diversity in microbial mats and sediments from the Atacama desert. Microb. Ecol. 2016;71:44–56. doi: 10.1007/s00248-015-0649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lauber CL, Hamady M, Knight R, Fierer N. Pyrosequencing-based assessment of soil pH as a predictor of soil bacterial community structure at the continental scale. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:5111–5120. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00335-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naumoff DG, Dedysh SN. Lateral gene transfer between the Bacteroidetes and Acidobacteria: The case of α-l-rhamnosidases. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:3843–3851. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pattee HE. Production of aflatoxins by Aspergillus flavus cultured on flue-cured tobacco. Appl. Microbiol. 1969;18:952–953. doi: 10.1128/am.18.5.952-953.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Badri DV, Weir TL, VanderLelie D, Vivanco JM. Rhizosphere chemical dialogues: Plant–microbe interactions. Curr. Opin. Biotech. 2009;20:642–650. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raza W, Ling N, Yang LD, Huang QW, Shen QR. Response of tomato wilt pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum to the volatile organic compounds produced by a biocontrol strain Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SQR-9. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:24856. doi: 10.1038/srep24856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silva RN, Monteiro VN, Steindorff AS, Gomes EV, Noronha EF, Ulhoa CJ. Trichoderma/pathogen/plant interaction in pre-harvest food security. Fungal Biol. 2019;123:565–583. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2019.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mcgarvey JA, Denny TP, Schell MA. Spatial-temporal and quantitative analysis of growth and EPS I production by Ralstonia solanacearum in resistant and susceptible tomato cultivars. Phytopathology. 1999;89:1233–1239. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1999.89.12.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Michielse CB, Rep M. Pathogen profile update: Fusarium oxysporum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2009;10:311–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2009.00538.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee KCY, Morgan XC, Dunfield PF, Tamas I, Mcdonald IR, Stott MB. Genomic analysis of Chthonomonas calidirosea, the first sequenced isolate of the phylum Armatimonadetes. ISME J. 2014;8:1522–1533. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen YP, Rekha PD, Arun AB, Shen FT, Lai WA, Young CC. Phosphate solubilizing bacteria from subtropical soil and their tricalcium phosphate solubilizing abilities. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2006;34:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2005.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haas D, Defago G. Biological control of soil-borne pathogens by fluorescent pseudomonads. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005;3:307–319. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bakker PA, Pieterse CM, VanLoon LC. Induced systemic resistance by fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. Phytopathology. 2007;97:239–243. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-97-2-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramesh R, Ghanekar MP, Joshi AA. Potential rhizobacteria for the suppression of bacterial wilt pathogen, Ralstonia solanacearum in eggplant (Solanum melongena L). Veg. Sci. 2009;36:193–199. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu H, Li YY, Yan Y, Zheng L, Li XH, Huang J. Physiological specialization of Ralstonia solanacearum strains isolated from Enshi, Hubei Province. Chin. Tobacco Sci. 2014;35:79–83. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peeters E, Nelis HJ, Coenye T. Comparison of multiple methods for quantification of microbial biofilms grown in microtiter plates. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2008;72:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tans-Kersten J, Brown D, Allen C. Swimming motility, a virulence trait of Ralstonia solanacearum, is regulated by FlhDC and the plant host environment. Mol. Plant Microbe. In. 2004;17:686–695. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2004.17.6.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ewels P, Magnusson M, Lundin S, Kaller M. MultiQC: Summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:3047–3048. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trapanell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Young MD, Wakefield MJ, Smyth GK, Oshlack A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: Accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mao XZ, Cai T, Olyarchuk JG, Wei LP. Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3787–3793. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zheng XF, Zhu YJ, Wang JP, Wang ZR, Liu B. Combined use of a microbial restoration substrate and avirulent Ralstonia solanacearum for the control of tomato bacterial wilt. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:20091. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-56572-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hu Y, Li YY, Yang XQ, Li CL, Wang L, Feng J, Chen SW, Li XH, Yang Y. Effects of integrated biocontrol on bacterial wilt and rhizosphere bacterial community of tobacco. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:2653. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-82060-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu B, Wang X, Yang L, Yang H, Zeng H, Qiu Y, Wang CJ, Yu J, Li JP, Xu DH, He ZL, Chen SW. Effects of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens ZM9 on bacterial wilt and rhizosphere microbial communities of tobacco. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016;103:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2016.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang CS, Lin Y, Tian XY, Xu Q, Chen ZH, Lin W. Tobacco bacterial wilt suppression with biochar soil addition associates to improved soil physiochemical properties and increased rhizosphere bacteria abundance. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2017;112:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2016.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hill TC, Walsh KA, Harris JA, Moffett BF. Using ecological diversity measures with bacterial communities. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2003;43:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2003.tb01040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.