Abstract

Abscisic acid–inducible NAC32 alleviates magnesium toxicity-mediated cell death in roots through direct regulation of XIPOTL1 expression in Arabidopsis.

Dear Editor,

Magnesium (Mg) is one of the macronutrients essential for plant growth and development; however, in serpentine soils, which have a calcium ion (Ca2+):Mg2+ ratio of 1:24 and are widely distributed worldwide, Mg toxicity is a very serious issue that threatens crop quality and yield (Brady et al., 2005; Marschner, 2011; Guo et al., 2014). In recent years, the physiological and molecular mechanisms underlying plant responses to Mg deficiency have been widely investigated (Yan et al., 2018; Meng et al., 2022; Tang et al., 2022). However, the molecular mechanisms of plant responses to Mg toxicity remain largely unclear. Here, we revealed that Mg toxicity inhibited primary root (PR) growth by inducing cell death in the root tips of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana). We then determined that XIPOTL1 (XPL1), encoding a phosphoethanolamine N-methyltransferase, which is also named Defective Primary Root2 (DPR2) or PEAMT1 (PMT1), is involved in Mg toxicity-mediated cell death in root tips. Subsequently, we found that the A subfamily of stress-responsive NAM, ATAF1/2, and CUC2 (SNAC-A) transcription factor NAC32 modulates XPL1 expression, whereby regulating Mg toxicity tolerance in Arabidopsis.

We observed dose-dependent Mg toxicity-mediated PR growth inhibition (Supplemental Figure 1A). We hypothesized that Mg toxicity-mediated PR growth cessation might be caused by root cell death. To test this hypothesis, we evaluated cell death in root tips via propidium iodide (PI) staining (Truernit and Haseloff, 2008). In seedlings subjected to Mg toxicity, the root meristematic zone (MZ) and elongation zone (EZ) showed obvious PI staining, and the stained area was significantly enlarged with increasing concentrations of Mg and prolonged stress exposure (Supplemental Figure 1, B and C; Supplemental Materials and Methods S1).

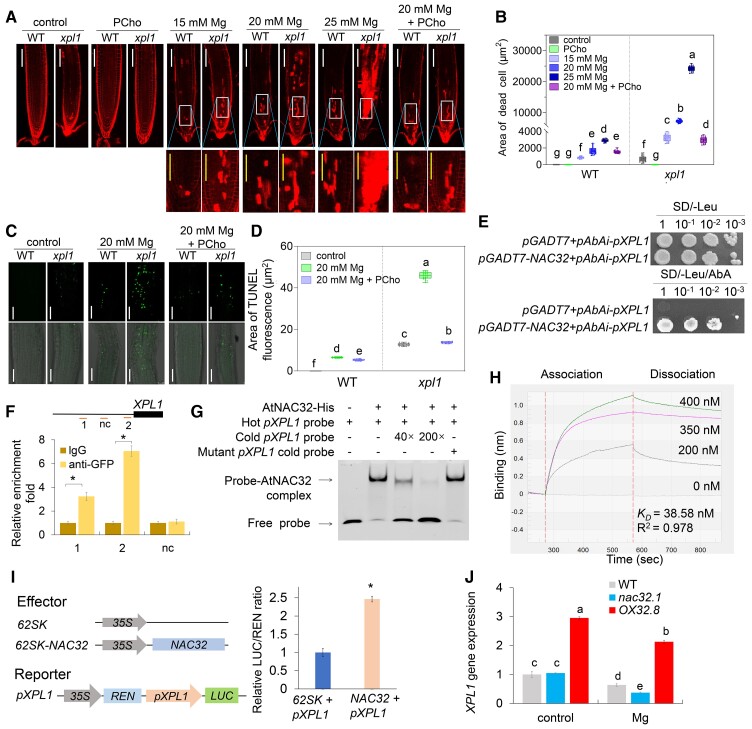

We next performed a transcriptome analysis to determine the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in Arabidopsis seedlings subjected to Mg toxicity. A total of 3442 DEGs (2172 up-regulated and 1270 down-regulated genes) were identified (Supplemental Figure 2, A and B; Supplemental Table 1). The expression patterns of seven genes were randomly selected and measured via RT‒qPCR, and the results showed good consistency with the transcriptome data (Supplemental Figure 2, C and D; Supplemental Table 2). Gene ontology analysis showed that the up-regulated DEGs were mainly enriched in pathways related to stress or defense responses, phytohormone responses, and senescence processes (Supplemental Figure 2E), while the down-regulated DEGs were significantly enriched in pathways associated with cell wall organization and metabolism, Mg2+ homeostasis, growth, development or differentiation, and lipid biosynthesis and metabolism (Supplemental Figure 2F). Next, these DEGs were subjected to regulatory network analysis. The XPL1/DPR2/PEAMT1/PMT1 gene (At3g18000), which encodes a phosphoethanolamine N-methyltransferase that catalyzes phosphocholine (PCho) biosynthesis, was identified in eight enriched pathways of the down-regulated DEGs (Supplemental Figure 2G). Loss of function of XPL1 results in ROS overaccumulation and cell death in root tips and alters the structure of the cytoskeleton, ultimately leading to severe PR growth inhibition (Mou et al., 2002; Cruz-Ramírez et al., 2004; Begora et al., 2010; Zou et al., 2019; He et al., 2022). We then analyzed whether the Mg toxicity-mediated cell death in root tips was affected in the xpl1 mutant and whether the phenotype was due to the defect in PCho. PI staining showed that Mg toxicity induced more severe cell death in the xpl1 mutant plants than in wild-type (WT) plants; however, supplementation with PCho markedly reduced root cell death (Figure 1, A and B). To further determine whether the Mg toxicity-induced cell death in root tips was associated with programmed cell death (PCD), we performed a terminal deoxynucleotide transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay. Mg toxicity strongly increased the number of TUNEL-positive nuclei, especially in the xpl1 mutant, but supplementation with PCho markedly reduced the numbers of TUNEL-positive nuclei in both the WT and the xpl1 mutant (Figure 1, C and D). These results demonstrate that the XPL1 gene and its involvement in PCho synthesis are key factors in Mg toxicity-mediated cell death in root tips.

Figure 1.

NAC32 positively regulates Mg toxicity tolerance by modulating XPL1 expression through direct binding to the XPL1 promoter. A, Representative images of PI staining showing cell death in the root tips of 4-day-old WT plants and xpl1 mutants treated with or without Mg (10, 15, 20, or 25 mM), 100 μM PCho or their combination for 3 d (white bar, 100 μm; yellow bar, 50 μm). B, Quantification of cell death in root tips treated in the same manner as in (A). The results shown are the means ± Sds (n = 3, more than 15 seedlings/genotype/treatment). C, Detection of PCD in WT and xpl1 root tips via a terminal deoxynucleotide transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assays. Four-day-old WT plants and xpl1 mutants treated with or without 20 mM Mg, 100 μM PCho, or their combination for 3 d (bar, 50 μm). D, Quantification of PCD in root tips treated in the same manner as in (C). The results shown are the means ± Sds (n = 3, more than 10 seedlings/genotype/treatment). The central line in boxplots is the median, the box indicates the first and third quartiles, and the whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum values, the dots represent the measurements for each plant. E, Y1H assay showing that NAC32 bound to the promoter of the XPL1 gene. Transformed yeast cells were grown on Sd-Leu/AbA medium. The assay was performed three times, each yielding similar results. F, Results of a ChIP–qPCR assay of the NAC32-DNA complex. A schematic of the primer design for the XPL1 promoter is shown at the top of the panel. The red lines mark sequences amplified by ChIP‒qPCR. ChIP‒qPCR was performed in the absence (IgG) or presence (anti-GFP) of an anti-GFP antibody. No enrichment was observed in the negative control (nc), which lacked the NAC core sequence. The results shown are the means ± Sds (n = 3). G, Results of an EMSA revealing specific NAC32 binding to the XPL1 promoter region harboring NAC32-binding sites. H, Detection of the binding of NAC32 to region #2 of the XPL1 promoter using biolayer interferometry technology. No detectable signal was obtained when the protein buffer control (0 nM) was used. KD, equilibrium dissociation constant. R2, coefficient of determination. I, Transient dual-LUC reporter assays showing that NAC32 transcriptionally activates XPL1 expression. The results shown are the means ± Sds (n = 9). J, Relative expression of the XPL1 gene in 5-day-old WT, nac32 and OX32 seedlings treated with 20 mΜ Mg for 24 h. The results shown are the means ± Ses (n = 3). The asterisks show significant differences from the control according to a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (P < 0.05). The different letters indicate significantly different values at P < 0.05 according to Tukey’s test.

We sought to determine which transcription factors could directly modulate XPL1 expression. For this, we screened a yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) library and obtained the SNAC-A transcription factor NAC32, and the result of a subsequent Y1H assay further confirmed the interactions between NAC32 and the XPL1 promoter (Figure 1E). The binding of NAC32 to the XPL1 promoter region was additionally evaluated via chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)–qPCR (Figure 1F), an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) (Figure 1G) and biolayer interferometry technology (Figure 1H). To confirm the transcriptional regulation of XPL1 expression by NAC32, we cotransfected plants with a 62SK-NAC32 plasmid and a promoterXPL1-Luciferase reporter construct. Cotransfection with NAC32 increased XPL1 expression (Figure 1I). We then examined XPL1 gene expression in the T-DNA insertion mutant nac32.1 and the NAC32-overexpressing 35S:NAC32 (OX32.8) transgenic Arabidopsis line (Allu et al. 2016; Mahmood, El-Kereamy, et al. 2016; Mahmood, Xu, et al. 2016). RT‒qPCR analysis revealed that XPL1 expression was highly up-regulated in OX32 but was not detected in the nac32 mutant (Figure 1J).

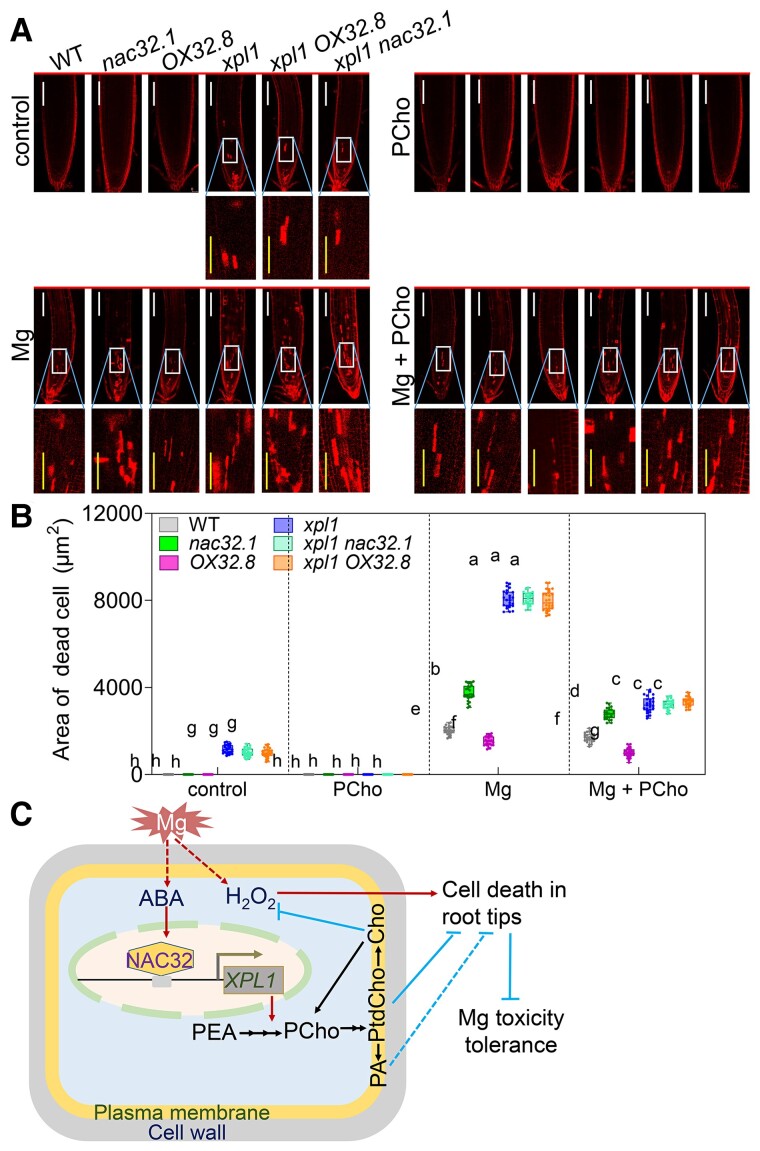

Mg toxicity induced NAC32 gene expression (Supplemental Figure 3A). GUS staining of the promoterNAC32:GUS transgenic line indicated that Mg toxicity significantly induced NAC32 expression in both the roots and the leaves (Supplemental Figure 3, B–E). Interestingly, the detection of the NAC32 protein using a globally active 35S promoter-driven NAC32-GFP indicated that Mg toxicity increased NAC32 protein abundance in roots (Supplemental Figure 3F). We then analyzed the physiological roles of NAC32 in Arabidopsis in response to Mg toxicity. The two nac32 mutants exhibited increased inhibition of PR growth, indicating increased sensitivity to Mg toxicity, whereas the two OX32 lines exhibited less inhibition of PR growth under Mg toxicity (Supplemental Figure 4, A and B). We also measured the lengths of the MZ and EZ and assessed the MZ cell number. The values of all three indexes were reduced in the two nac32 mutants; however, the two OX32 lines showed the opposite phenotype (Supplemental Figure 4, C–E). We performed a hydroponic experiment to investigate the role of NAC32 in modulating Mg toxicity tolerance. The results of chlorophyll fluorescence analysis indicated that OX32 plants showed increased Mg toxicity tolerance, whereas nac32 mutants showed decreased Mg toxicity tolerance (Supplemental Figure 5, A–H). Mg toxicity resulted in plant death due to increased H2O2 and malondialdehyde levels in the leaves; this was especially true for the nac32 mutant, whereas OX32 exhibited increased tolerance to Mg toxicity (Supplemental Figure 5, I–K). We then examined Mg-induced cell death in the root tips (Figure 2, A and B). The nac32 mutant plants exhibited more root cell death than the WT plants, while the OX32 plants showed the opposite results. Supplementation with PCho markedly reduced cell death, especially in the nac32 mutant. We also analyzed the phenotypes of xpl1 OX32 and xpl1 nac32 double mutants. Both double mutants showed PI staining similar to that of the xpl1 mutant (Figure 2, A and B). We then investigated PR growth in response to Mg toxicity in the double mutants. The xpl1 OX32 and xpl1 nac32 double mutants showed PR growth similar to that of the xpl1 mutant (Supplemental Figure 6). Notably, the xpl1 mutant displayed reduced PR growth under normal conditions compared to WT plants, and mutation of XPL1 resulted in increased sensitivity to Mg toxicity as well as salt stress (Supplemental Figure 6; Mou et al., 2002; He et al., 2022), indicating that XPL1 is an important factor controlling PR elongation. These results suggested that XPL1 is epistatic to NAC32 in regulating the Mg toxicity response.

Figure 2.

NAC32 alleviates Mg toxicity-induced cell death in the root tips of Arabidopsis. A, Representative images of PI staining showing cell death in the root tips of 4-day-old WT, nac32.1, OX32.8, xpl1, xpl1 nac32.1 and xpl1 OX32.8 plants treated with or without 20 mM Mg, 100 μM phosphocholine (PCho), or their combination for 4 d (bar, 100 μm). B, Quantification of cell death in root tips treated in the same manner as in (A). The results shown are the means ± Sds (n = 3, more than 15 seedlings/genotype/treatment, Tukey’s test, P < 0.05). The central line in boxplots is the median, the box indicates the first and third quartiles, and the whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum values, the dots represent the measurements for each plant. C, Proposed model for the mechanism by which ABA-inducible NAC32 positively regulates Mg toxicity tolerance through regulation of XPL1 expression in Arabidopsis. Mg toxicity increases the H2O2 level, thus resulting in cell death in roots. Mg toxicity induces ABA accumulation and subsequently increases NAC32 expression. NAC32 directly and positively regulates XPL1 expression, thereby increasing PCho biosynthesis and ultimately alleviating Mg toxicity-mediated root cell death by modulating membrane stability in response to Mg toxicity through PA and its precursor PtdCho and by reducing H2O2 accumulation through PtdCho-converted Cho. Moreover, PA, as a signaling molecule, regulates plant growth and stress responses. PEA, phosphoethanolamine.

Overall, given our results combined with those of previous studies (Cruz-Ramírez et al., 2004; Zou et al., 2019), we propose a model of the Mg toxicity response involving a link between XPL1 and Mg toxicity-mediated cell death in roots (Figure 2C). On the one hand, Mg toxicity induces H2O2 accumulation, resulting in oxidative damage and cell death in roots (Supplemental Figure 5, I–K; Marschner, 2011; Guo et al., 2014). On the other hand, Mg toxicity also induces NAC32 expression and NAC32 protein accumulation (Supplemental Figure 3), which may be caused by Mg toxicity-induced abscisic acid (ABA) accumulation (Guo et al., 2014). NAC32 up-regulates the expression of XPL1 gene by directly binding to XPL1 promoter, thereby increasing PCho biosynthesis. PCho is the precursor for the biosynthesis of phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho). PtdCho can be converted into phosphatidic acid (PA) and choline (Cho) (Smith et al., 2000). Cho inhibits root cell death caused by oxidative damage through the reduction of H2O2 accumulation, while PA, as a signal molecule, plays an important role in plant development and stress response (Cruz-Ramírez et al., 2004; Zou et al., 2019). Moreover, as membrane components, both PA and PtdCho modulate membrane stability in response to Mg toxicity (Cruz-Ramírez et al., 2004). Taken together, ABA-inducible NAC32 alleviates Mg toxicity-mediated cell death in roots through regulation of XPL1 expression in Arabidopsis. Future studies will elucidate how the ABA signaling pathway is involved in NAC32-mediated Mg toxicity tolerance in plants.

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Mg toxicity induces cell death in root tips.

Supplemental Figure S2. Transcriptome analysis.

Supplemental Figure S3. Expression pattern of NAC32.

Supplemental Figure S4. NAC32 modulates the Mg toxicity tolerance.

Supplemental Figure S5. NAC32 positively regulates Mg toxicity tolerance.

Supplemental Figure S6. XPL1 is epistatic to NAC32 in regulating the Mg toxicity response.

Supplemental Materials and Methods S1.

Supplemental Table S1. Transcriptome data.

Supplemental Table S2. List of primers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Steven J. Rothstein at University of Guelph for providing OX32.6, OX32.8, and promoterNAC32:GUS seeds.

Contributor Information

Liangliang Sun, College of Horticulture, Shanxi Agricultural University, Taigu 030801, China.

Ping Zhang, College of Horticulture, Shanxi Agricultural University, Taigu 030801, China.

Menglu Xing, College of Horticulture, Shanxi Agricultural University, Taigu 030801, China.

Ruishan Li, College of Horticulture, Shanxi Agricultural University, Taigu 030801, China.

Hao Yu, College of Horticulture, Shanxi Agricultural University, Taigu 030801, China.

Qiong Ju, College of Horticulture, Shanxi Agricultural University, Taigu 030801, China.

Jianli Yang, State Key Laboratory of Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, College of Life Sciences, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310058, China.

Jin Xu, College of Horticulture, Shanxi Agricultural University, Taigu 030801, China.

Funding

This research was supported by the China National Natural Sciences Foundation (32070314), the Science and technology Innovation Fund project of Shanxi Agricultural University (2020BQ24 and 2020QC13), and the Basic Research Program of Shanxi Province (Free Exploration) (20210302124369 and 20210302124065).

References

- Allu AD, Brotman Y, Xue GP, Balazadeh S (2016) Transcription factor ANAC032 modulates JA/SA signalling in response to Pseudomonas syringae infection. EMBO Rep 17(11): 1578–1589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begora MD, Macleod MJR, McCarry BE, Summers PS, Weretilnyk EA (2010) Identification of phosphoethanolamine N-methyltransferase from Arabidopsis and its role in choline and phospholipid metabolism. J Biol Chem 285(38): 29147–29155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KU, Kruckeberg AR, Bradshaw HD (2005) Evolutionary ecology of plant adaptation to serpentine soils. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 36(1): 243–266 [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Ramírez A, López-Bucio J, Ramírez-Pimentel G, Zurita-Silva A, Sánchez-Calderon L, Ramírez-Chávez E, González-Ortega E, Herrera-Estrella L (2004) The xipotl mutant of Arabidopsis reveals a critical role for phospholipid metabolism in root system development and epidermal cell integrity. Plant Cell 16(8): 2020–2034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Cong Y, Hussain N, Wang Y, Liu Z, Jiang L, Liang Z, Chen K (2014) The remodeling of seedling development in response to long-term magnesium toxicity and regulation by ABA-DELLA signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol 55(10): 1713–1726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He QY, Jin JF, Lou HQ, Dang FF, Xu JM, Zheng SJ, Yang JL (2022) Abscisic acid-dependent PMT1 expression regulates salt tolerance by alleviating abscisic acid-mediated reactive oxygen species production in Arabidopsis. J Integr Plant Biol 64(9): 1803–1820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood K, El-Kereamy A, Kim SH, Nambara E, Rothstein SJ (2016) ANAC032 positively regulates age-dependent and stress induced senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 57(10): 2029–2046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood K, Xu Z, El-Kereamy A, Casaretto JA, Rothstein SJ (2016) The Arabidopsis transcription factor ANAC032 represses anthocyanin biosynthesis in response to high sucrose and oxidative and abiotic stresses. Front Plant Sci 7: 1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschner H (2011) Marschner's Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, Ed 3. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, USA, pp 672 [Google Scholar]

- Meng S-F, Zhang B, Tang R-J, Zheng X-J, Chen R, Liu C-G, Jing Y-P, Ge H-M, Zhang C, Chu Y-L, et al. (2022) Four plasma membrane-localized MGR transporters mediate xylem Mg2+ loading for root-to-shoot Mg2+ translocation in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant 15(5): 805–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mou ZL, Wang XQ, Fu ZM, Dai Y, Han C, Ouyang J, Bao F, Hu YX, Li JY (2002). Silencing of phosphoethanolamine N-methyltransferase results in temperature-sensitive male sterility and salt hypersensitivity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 14(9): 2031–2043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DD, Summers PS, Weretilnyk EA (2000) Phosphocholine synthesis in spinach: characterization of phosphoethanolamine N-methyltransferase. Physiol Plant 108(3): 286–294 [Google Scholar]

- Tang R-J, Meng S-F, Zheng X-J, Zhang B, Yang Y, Wang C, Fu A-G, Zhao F-G, Lan W-Z, Luan S (2022) Conserved mechanism for vacuolar magnesium sequestration in yeast and plant cells. Nat Plants 8(2): 181–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truernit E, Haseloff J (2008) A simple way to identify non-viable cells within living plant tissue using confocal microscopy. Plant Methods 4(1): 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y-W, Mao D-D, Yang L, Qi J-L, Zhang X-X, Tang Q-L, Li Y-P, Tang R-J, Luan S (2018) Magnesium transporter MGT6 plays an essential role in maintaining magnesium homeostasis and regulating high magnesium tolerance in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci 9: 274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y, Zhang X, Tan Y, Huang J, Zheng Z, Tao L (2019) Phosphoethanolamine n-methyltransferase 1 contributes to maintenance of root apical meristem by affecting ros and auxin-regulated cell differentiation in Arabidopsis. New Phytol 224(1): 258–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.