Abstract

Background

The goal of this study was to determine whether an awake prone position (aPP) reduces the global inhomogeneity (GI) index of ventilation measured by electrical impedance tomography (EIT) in COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory failure (ARF).

Methods

This prospective crossover study included COVID-19 patients with COVID-19 and ARF defined by arterial oxygen tension:inspiratory oxygen fraction (PaO2:FIO2) of 100–300 mmHg. After baseline evaluation and 30-min EIT recording in the supine position (SP), patients were randomised into one of two sequences: SP-aPP or aPP-SP. At the end of each 2-h step, oxygenation, respiratory rate, Borg scale and 30-min EIT were recorded.

Results

10 patients were randomised in each group. The GI index did not change in the SP-aPP group (baseline 74±20%, end of SP 78±23% and end of aPP 72±20%, p=0.85) or in the aPP-SP group (baseline 59±14%, end of aPP 59±15% and end of SP 54±13%, p=0.67). In the whole cohort, PaO2:FIO2 increased from 133±44 mmHg at baseline to 183±66 mmHg in aPP (p=0.003) and decreased to 129±49 mmHg in SP (p=0.03).

Conclusion

In spontaneously breathing nonintubated COVID-19 patients with ARF, aPP was not associated with a decrease of lung ventilation inhomogeneity assessed by EIT, despite an improvement in oxygenation.

Short abstract

In spontaneously breathing, nonintubated COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory failure, awake prone position is not associated with a decrease of lung ventilation inhomogeneity assessed by electrical impedance tomography https://bit.ly/3Wb4Gnt

Introduction

Acute respiratory failure (ARF) related to COVID-19 pneumonia is associated with severe impairment in oxygenation, and initially, there is only moderate evidence of respiratory distress [1]. The pathophysiology of underlying hypoxaemia includes intrapulmonary shunt, ventilation to perfusion (V′/Q′) mismatch, pulmonary artery embolism and microvascular coagulation despite relatively preserved lung-gas volumes at the onset of the disease [2, 3]. V′/Q′ mismatch is the result of ventilation and/or perfusion inhomogeneity [4]. In intubated and mechanically ventilated patients, a prone position (PP) improves oxygenation notably through redistribution of the tidal volume towards the dorsal region and by increasing V′/Q′ matching. Therefore, a prolonged repeated PP is recommended for moderate-to-severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [5] and decreases mortality.

Preliminary studies have evaluated the feasibility of an awake prone position (aPP) for COVID-19 patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) [6, 7], and a randomised meta-trial combing aPP and high-flow O2 nasal cannula has shown a decrease in the need for intubation [8]. Electrical impedance tomography (EIT) is a bedside, noninvasive, functional method for monitoring lung ventilation and measuring variations in chest impedance with a thoracic belt [9]. For a mechanically ventilated patient, EIT can be used to evaluate lung recruitment, which is assessed by positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) [10, 11], and to personalise ventilation [12].

EIT has been investigated in ventilated patients with COVID-19 [13], but investigations on nonintubated and spontaneously breathing patients are scarce [14, 15]. Therefore, the main objective of the study was to evaluate lung inhomogeneity assessed by EIT in COVID-19 patients with ARF in a supine position (SP) and PP. The secondary objectives were to compare respiratory function and derived EIT indices in both positions.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

We conducted this prospective crossover cohort study in a tertiary university hospital in Marseille, France. We screened all patients >18 years old who were admitted to the ICU with COVID-19 confirmed by reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR). We included patients who were awake and spontaneously breathing with ARF and hypoxaemia (arterial oxygen tension (PaO2):inspiratory oxygen fraction (FIO2) 100–300 mmHg) requiring O2 supply. Patients were not included if they had evidence of respiratory distress with a high probability of intubation within the next hours (respiratory frequency >35 cycles·min−1, respiratory muscles fatigue, agitation or confusion) or a pacemaker (a contraindication for EIT monitoring). Pregnant or breastfeeding women and patients deprived of liberty or lacking health insurance were also not included.

Study approval was obtained according to French legislation (ethics committee, comité de protection des personnes, Ile de France 1). Each subject gave written informed consent. The study was registered as NCT04632602 in the clinical trials database (https://clinicaltrials.gov/).

Baseline assessment and data collection

The following parameters were recorded in the electronic case report form of each subject: age, sex, body mass index, comorbidities, dates of first COVID-19 symptoms, RT-PCR positivity, and hospital and ICU admission. Baseline respiratory parameters included oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry (SpO2), respiratory frequency, O2 supply, arterial blood gas (ABG), PaO2:FIO2 and Borg scale ranking. PaO2:FIO2 was calculated with FIO2 for patients who received O2 with a high-flow nasal cannula or estimated for those who received O2 through non-rebreathing masks with the following formula [16]:

FIO2=21%+oxygen flow rate in L·min−1×3

Thoracic computed tomography (CT) scan was performed as routine exam at ICU admission, and findings were collected. The following clinical events and outcomes were also recorded: intubation, duration of mechanical ventilation, and ICU and hospital mortality.

Design of the study

Patients were randomised to undergo one of two mutually exclusive sequences: SP and then aPP (SP-aPP group) or aPP and then SP (aPP-SP group). Each step lasted 2 h with a washout period of 30 min between them. A 30-min EIT recording was performed at baseline and at the end of each step. SpO2, respiratory frequency, O2 supply, ABG, PaO2:FIO2 and Borg scale ranking were also assessed at the end of each step. The study design is provided in figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Study design. PP: prone position; SP: supine position; RR: respiratory rate; ABG: arterial blood gas; EIT: electrical impedance tomography.

EIT analysis

EIT monitoring was performed using a Pulmo Vista 500® monitor (Dräger, Lübeck, Germany), which was connected to a belt with 16 electrodes placed around the patient's chest at the fifth or sixth intercostal space. EIT measurements were generated by passing a weak alternating electrical current through the belt. Regional variations in impedance (ΔZ) during ventilation were used to map the tidal volume distribution in the lungs. The EIT terms used have been described previously [9].

Our main EIT parameter of interest was the global inhomogeneity (GI) index [17]. Briefly, the GI index is the difference in impedances between end-inspiration and end-expiration and the variations in its pixel values within a predefined lung area. The calculation of GI is based on the difference between each pixel value and the median value of all pixels. These values are normalised by the sum of impedance values within the lung area:

GI=Σ (pixel differences from median)/Σ(pixels), where Σ(pixels)=Σ (ΔZj), Σ (pixel differences from median)=Σ (ΔZj – ΔZ median), ΔZj is the fEIT image value in pixel j, ΔZ median is the median image value, and all sums are calculated for all pixels in the image.

Additional EIT indices studied were the surface of ventilation (SoV) and the centre of ventilation (CoV). SoV represents the number of pixels with variation of impedance. CoV is a measure of anteroposterior distribution of tidal volume and computed by the following formula:

CoV (%)=(height weighted pixel sum)/(pixel sum)

CoV yields a value between 0 and 100%, where 0% indicates all image amplitude at the top, and 100% indicates all amplitude at the bottom of the image. As the centre of the distribution of ventilation moves dorsally, CoV increases [9]. All EIT recordings were analysed offline by two operators (T. Brunelle and C. Guervilly) who were blinded to the sequence allocation.

Statistical analysis

The methodology of analysis complies with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials Statement (CONSORT, http://www.consort-statement.org/consort-statement/). The statistical analysis and figures were generated using SPSS Version 20 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). We postulated that PP would be associated with a decrease in the GI index of 20% (with a standard deviation of 20%). With a power of 80% and α risk of 5%, we needed to include 10 patients in each group. A crossover design was chosen to avoid the risk of important inter-individual heterogeneity and was sufficient with a global cohort of 10 patients.

A washout period of 30 min was used to decrease the risk of sequence effect (carryover effect). However, in case of a sequence effect, a higher number of anticipated patients (10 patients for each sequence) counteracted this risk of loss of power. In case of no association between the sequence and the position (aPP and SP), the effect of the position was tested with an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). Then, a paired t-test for repeated measurements was performed between each time point (baseline and end of step 1, end of step 1 and end of step 2, baseline and end of step 2). We also tested the correlation between PaO2:FIO2 and GI at each time point with Pearson's test. A p-value <0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

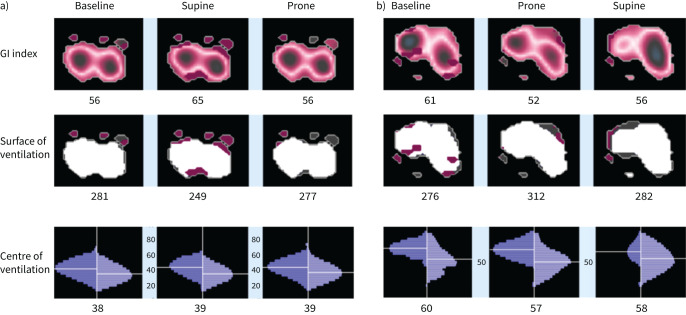

A flow chart of the study is shown in figure 2. Initially, 22 patients gave their consent and were included in the study. One patient was rapidly intubated after consent, and another withdrew his consent; therefore, data were available for 20 patients. Table 1 shows the demographics, medical history, gravity scores, thoracic CT scan findings, respiratory function and support at ICU admission and clinical outcomes of the studied population.

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram of the study. PaO2:FIO2: arterial oxygen tension:inspiratory oxygen fraction.

TABLE 1.

Demographics, gravity scores, respiratory function and support at ICU admission and outcomes

| Patients n | 20 |

| Age years, mean±sd | 60±15 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 4 (20) |

| Body mass index, mean±sd | 27±3 |

| Medical history, n (%) | |

| Hypertension | 7 (35) |

| Diabetes | 8 (40) |

| Ischaemic cardiomyopathy | 3 (15) |

| Stroke | 1 (5) |

| Chronic lung disease | 1 (5) |

| Solid organ cancer, haematological malignancy | 3 (15) |

| Chronic renal failure | 0 (0) |

| Simplified acute physiology score 2, mean±sd | 31±12 |

| Sepsis organ failure assessment score, mean±sd | 3±2 |

| Delay between onset of symptoms to ICU admission, days, mean± sd | 7±4 |

| Respiratory function at ICU admission, mean±sd | |

| Transcutaneous peripheral saturation % | 93±4 |

| Respiratory rate cycles per minute | 29±8 |

| Borg scale ranking | 3±2 |

| Arterial pH | 7.49±0.03 |

| PaCO2 mmHg | 33±4 |

| PaO2:FIO2 mmHg | 146±39 |

| Arterial oxygen saturation % | 96±2 |

| Arterial lactate mmol·L−1 | 1.5±0.6 |

| CT scan characteristics at ICU admission, n (%) | |

| Diffuse and bilateral pattern | 20 (100) |

| Ground-glass opacities | |

| <25% | 4 (20) |

| 25–50% | 9 (45) |

| >75% | 7 (35) |

| Consolidation | 5 (25) |

| Crazy paving | 7 (35) |

| Respiratory support at ICU admission | |

| O2 non-rebreathing mask, n (%) | 4 (20) |

| O2 L·min−1, mean±sd | 12±2 |

| High-flow nasal cannula, n (%) | 16 (80) |

| O2 flow L·min−1, mean±sd | 47±7 |

| O2 inspired fraction %, mean±sd | 59±17 |

| Outcomes | |

| Intubation during ICU stay, n (%) | 3 (15) |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation days, mean±sd | 15±6 |

| ICU mortality, n (%) | 1 (5) |

| Hospital mortality, n (%) | 1 (5) |

ICU: intensive care unit; sd: standard deviation; PaCO2: arterial carbon dioxide tension; PaO2:FIO2: arterial oxygen tension:inspiratory oxygen fraction; CT: computed tomography.

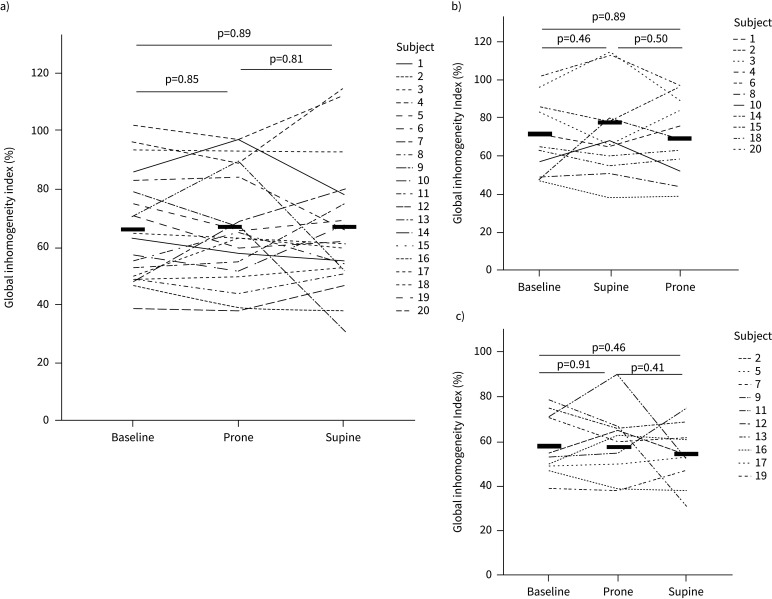

Three patients were intubated during their ICU stay, and one of them died. The overall ICU and hospital mortality rate was 5%. 10 patients were randomised into each group (SP-aPP and aPP-SP). One patient in the SP-aPP group could not tolerate aPP, so all time points were available for only nine patients in this group. An example of EIT measurements for one patient in each group is provided in figure 3. Respiratory function at baseline was not different between the two groups. Mean respiratory frequency was 28±7 cycles·min−1 in the aPP-SP group and 29±9 cycles·min−1 in the SP-aPP group (p=0.74). Mean PaO2:FIO2 was 135±25 mmHg in the aPP-SP group and 152±60 mmHg in the SP-aPP group (p=0.55). Borg scale ranking was 4±2 inthe aPP-SP group and 6±3 in theSP-aPP group (p=0.14).

FIGURE 3.

Representative images of electrical impedance tomography indices in a) one patient in the supine-prone group and b) one patient in the prone-supine group. GI: global inhomogeneity.

EIT analysis

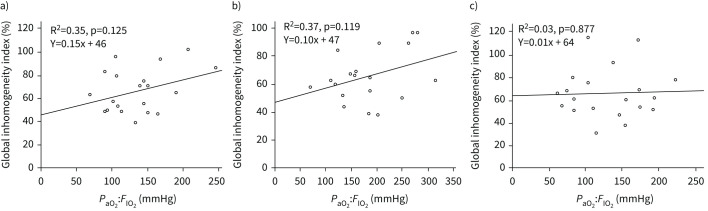

Concerning the GI index, we did not find an association between sequence and position (p=0.053). We also found no significant change in GI index from the comparison of each time point in the SP-aPP group (baseline 74±20%, end of SP 78±23% and end of aPP 72±20%, p=0.85) and in the aPP-SP group (baseline 59±14%, end of aPP 59±15% and end of SP 54±13%, p=0.67) (figure 4). In the whole cohort, the CoV did not significantly change during the study (49±7 at baseline, 49±7 during aPP, and 47±7 during SP, p=0.62). Furthermore, the surface of ventilation did not significantly change during the study (330±78 at baseline, 328±71 during aPP and 332±68 during SP, p=0.98).

FIGURE 4.

Global inhomogeneity index measured by electrical impedance tomography at baseline, end of prone position and end of supine position in a) the whole cohort, b) the supine-prone group and c) the prone-supine group. The thick black lines represent the mean.

Oxygenation and clinical respiratory parameters

In the whole cohort, PaO2:FIO2 increased from 133±44 mmHg at baseline to 183±66 mmHg in aPP (p=0.003) and decreased to 129±49 mmHg in SP (p=0.03). PaO2:FIO2 in aPP increased in 18 out of 19 patients, and the mean increase was 41±49%. The respiratory rate significantly decreased in aPP compared with baseline (22±5 and 27±6 cycles·min−1, p=0.002, respectively) but was not significantly different from that in SP (22±5 and 23±6 cycles·min−1, p=0.68, respectively). The Borg scale ranking did not significantly change during the study and remained relatively low (2.4±2.2 at baseline, 1.7±1.6 in aPP (p=0.13), and 2.1±2.1 in SP; p=0.46). PaO2:FIO2 and the GI index were not correlated at any time point of the study (figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Correlations between global inhomogeneity index and arterial oxygen tension:inspiratory oxygen fraction (PaO2:FIO2) in the whole cohort of patients a) at baseline, b) at the end of prone position and c) at the end of supine position.

Discussion

This prospective crossover study was performed with awake, nonintubated, spontaneously breathing COVID-19 patients with ARF. PP did not decrease ventilation inhomogeneity assessed by EIT, it did not modify the centre or surface of ventilation assessed by EIT, it increased oxygenation and decreased respiratory rate, and it did not modify the dyspnoea Borg score. aPP has widely been adopted by clinicians since the early beginning of the pandemic in both ICU settings and general wards. Numerous studies have evaluated its feasibility and clinical effects [6,7]. However, its potential benefit in critically ill COVID-19 patients is still being questioned in regard to preventing intubation [18, 19] or decreasing mortality [8].

The physiological effects of aPP in spontaneously breathing, nonintubated COVID-19 patients have not yet been fully described. In intubated and mechanically ventilated patients with non-COVID ARDS, improvement in oxygenation in PP is mainly due to redistribution of tidal volume towards dorsal regions and therefore where perfusion is still prominent and therefore decreasing V′/Q′ mismatch [20]. Dalla Corte et al. [21] showed that PP was associated with recruitment of dorsal regions and increased lung ventilation homogeneity in mechanically ventilated and paralysed intubated ARDS patients.

Despite improvement in oxygenation in both groups, Dos Santos Rocha et al. [15] found no redistribution of regional ventilation induced by aPP in COVID-19-related ARDS patients who were noninvasively ventilated (NIV), whereas PP of invasively ventilated patients led to redistribution of regional ventilation from the ventral to the dorsal lung areas. Therefore, since regional aeration was not significantly modified by aPP in NIV patients, they hypothesised that the benefit in oxygenation was predominantly explained by the redistribution of pulmonary blood flow and optimisation of ventilation-perfusion matching rather than alveolar recruitment or aeration change.

Additionally, we hypothesise that patients included at a relatively early state of the disease had a normal elastance (“phenotype L”) according to Gattinoni et al. [22]. We may reasonably consider that patients at a later stage of the disease with high elastance (“phenotype H”) could have a redistribution of ventilation and a decrease of GI during aPP. Previous studies have investigated lung perfusion with dual-energy or single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)/positron emission tomography (PET) CT scan in COVID-19 patients. They found that perfusion preferentially occurred in areas of non-ventilated inflamed lungs, suggesting complete loss of hypoxic vasoconstriction [23] aside from large perfusion defects that may or may not be related to pulmonary embolisms [24]. Also, in 10 intubated and mechanically ventilated COVID-19 ARDS patients, Mauri et al. [25] found a decrease of the GI index from 70±11% to 59±10% when increasing PEEP from 5 to 15 cmH2O. Seven of the patients were investigated using a modified EIT device allowing pulmonary perfusion distribution. The authors found a median V′/Q′ mismatch of 34% (interquartile range 32–45%).

The improvement in oxygenation that we observed during aPP without any variation of EIT indices suggests redistribution of lung perfusion towards ventral regions. To support this hypothesis, we performed dual-energy CT iodine mapping on one of the included patients, who was awake and breathing spontaneously. This was done first in SP and then after 4 h in aPP. We observed a redistribution of lung perfusion towards the ventral part of the lung (dependent lung in the PP) with no change in lung condensations/atelectasis topography (still prominent in dorsal regions). In the meantime, we observed a significant improvement in respiratory function (supplementary Appendix A).

Other studies have investigated the aeration response to aPP in patients with ARF related to COVID-19 using ultrasound scores [26–29]. Consistent results were observed with an improvement in aeration of the dorsal regions of the lungs during and after aPP, particularly in patients who benefited from the combination of aPP and high-flow O2 nasal cannula [26, 28] or noninvasive ventilation [27]. Interestingly, in those studies, the duration of aPP was longer (range 3 to 8 h) compared with those investigated in our study (2 h) and could at least partly explain the difference from our results, besides the different monitoring used. The relatively low Borg score ranking and respiratory rates contrast with the moderate hypoxaemia that we observed and support the concept of “silent” or “happy” hypoxaemia reported in COVID-19 disease, for which mechanisms have not been totally elucidated [30].

Our study suffers from some limitations. Besides the small sample size, we were not able to measure all EIT indices, particularly those related to pulmonary recruitment and atelectasis. These indices are only available when patients are ventilated on positive pressure with a decremental PEEP trial. We also cannot rule out redistribution of ventilation with longer periods of PP.

We could not investigate pulmonary perfusion with our EIT device. Indeed, this requires a specific device, and a currently experimental technique is not widespread. It also requires a saline injection via a central line during breath-holds of several seconds, which was not applicable in our clinical setting. Finally, our results cannot be generalised to patients with more severe disease (PaO2:FIO2 <100 mmHg).

Conclusion

In spontaneously breathing nonintubated COVID-19 patients with ARF, aPP is not associated with a decrease of lung ventilation inhomogeneity assessed by EIT, despite an improvement in oxygenation. Further studies investigating lung perfusion or intrapulmonary shunting are warranted to explain the mechanism or potential clinical benefits.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00509-2022.SUPPLEMENT (217.2KB, jpg)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patients and their families and all the frontline caregivers involved in the COVID-19 pandemic. We also thank Basile Puech for the computed tomography scan analysis.

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

This study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov with identifier number NCT04632602. Individual patients’ data reported in this article will be shared after de-identification (text, tables, figures and appendices), beginning 6 months and ending 2 years after article publication, to researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal and after approval of the corresponding author. The datasets generated and analysed during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contributions: C. Guervilly designed the study. K. Baumstarck and C. Guervilly developed the protocol and the statistical analysis plan. T. Brunelle, E. Prud'homme, J-E. Alphonsine, C. Sanz, S. Salmi, N. Peres, J-M. Forel, S. Hraiech, A. Roch and C. Guervilly included the patients and performed all procedures of the study and data acquisition. K. Baumstarck performed the statistical analysis of the data. T. Brunelle and C. Guervilly wrote the first draft of the manuscript. L. Papazian, S. Hraiech and A. Roch revised the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the revision, and read and approved the final version of the manuscript. C. Guervilly takes responsibility for the integrity of the work, from inception to publication.

Support statement: The study was funded by a grant from Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Marseille. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

Conflict of interest: L. Papazian received consultancy fees from Air Liquide MS, Faron and MSD outside the submitted work. C. Guervilly received fees from Xenios FMC outside the submitted work. The other authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Dhont S, Derom E, Van Braeckel E, et al. The pathophysiology of ‘happy’ hypoxemia in COVID-19. Respir Res 2020; 21: 198. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01462-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, et al. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA 2020; 324: 782–793. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connors JM, Levy JH. COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood 2020; 135: 2033–2040. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zarantonello F, Andreatta G, Sella N, et al. Prone position and lung ventilation and perfusion matching in acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 202: 278–279. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0775IM [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan E, Del Sorbo L, Goligher EC, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Society of Intensive Care Medicine/Society of Critical Care Medicine clinical practice guideline: mechanical ventilation in adult patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 195: 1253–1263. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0548ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elharrar X, Trigui Y, Dols A-M, et al. Use of prone positioning in nonintubated patients with COVID-19 and hypoxemic acute respiratory failure. JAMA 2020; 323: 2336–2338. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coppo A, Bellani G, Winterton D, et al. Feasibility and physiological effects of prone positioning in non-intubated patients with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19 (PRON-COVID): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8: 765–774. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30268-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehrmann S, Li J, Ibarra-Estrada M, et al. Awake prone positioning for COVID-19 acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure: a randomised, controlled, multinational, open-label meta-trial. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 20: S2213-2600(21)00356-8. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00356-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frerichs I, Amato MBP, van Kaam AH, et al. Chest electrical impedance tomography examination, data analysis, terminology, clinical use and recommendations: consensus statement of the TRanslational EIT developmeNt stuDy group. Thorax 2017; 72: 83–93. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eronia N, Mauri T, Maffezzini E, et al. Bedside selection of positive end-expiratory pressure by electrical impedance tomography in hypoxemic patients: a feasibility study. Ann Intensive Care 2017; 7: 76. doi: 10.1186/s13613-017-0299-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sella N, Zarantonello F, Andreatta G, et al. Positive end-expiratory pressure titration in COVID-19 acute respiratory failure: electrical impedance tomography vs. PEEP/FiO2 tables. Crit Care 2020; 24: 540. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03242-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lobo B, Hermosa C, Abella A, et al. Electrical impedance tomography. Ann Transl Med 2018; 6: 26. doi: 10.21037/atm.2017.12.06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perier F, Tuffet S, Maraffi T, et al. Electrical impedance tomography to titrate positive end-expiratory pressure in COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care 2020; 24: 678. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03414-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rauseo M, Mirabella L, Laforgia D, et al. A Pilot study on electrical impedance tomography during CPAP trial in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 pneumonia: the bright side of non-invasive ventilation. Front Physiol 2021; 12: 728243. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.728243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dos Santos Rocha A, Diaper J, Balogh AL, et al. Effect of body position on the redistribution of regional lung aeration during invasive and non-invasive ventilation of COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep 2022; 12: 11085. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-15122-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coudroy R, Frat JP, Girault C, et al. Reliability of methods to estimate the fraction of inspired oxygen in patients with acute respiratory failure breathing through non-rebreather reservoir bag oxygen mask. Thorax 2020; 75: 805–807. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-214863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao Z, Möller K, Steinmann D, et al. Evaluation of an electrical impedance tomography-based global inhomogeneity index for pulmonary ventilation distribution. Intensive Care Med 2009; 35: 1900–1906. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1589-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrando C, Mellado-Artigas R, Gea A, et al. Awake prone positioning does not reduce the risk of intubation in COVID19 treated with highflow nasal oxygen therapy: a multicenter, adjusted cohort study. Crit Care 2020; 24: 597. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03314-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nauka PC, Chekuri S, Aboodi M, et al. A case-control study of prone positioning in awake and nonintubated hospitalized coronavirus disease 2019 patients. Crit Care Explor 2021; 3: e0348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gattinoni L, Pesenti A, Carlesso E. Body position changes redistribute lung computed-tomographic density in patients with acute respiratory failure: impact and clinical fallout through the following 20 years. Intensive Care Med 2013; 39: 1909–1915. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3066-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dalla Corte F, Mauri T, Spinelli E, et al. Dynamic bedside assessment of the physiologic effects of prone position in acute respiratory distress syndrome patients by electrical impedance tomography. Minerva Anestesiol 2020; 86: 1057–1064. doi: 10.23736/S0375-9393.20.14130-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gattinoni L, Chiumello D, Caironi P, et al. COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatments for different phenotypes? Intensive Care Med 2020; 46: 1099–1102. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06033-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramos CD, Fernandes AP, Souza SPM, et al. Simultaneous imaging of lung perfusion and glucose metabolism in COVID-19 pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021; 203: 1186–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhawan RT, Gopalan D, Howard L, et al. Beyond the clot: perfusion imaging of the pulmonary vasculature after COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9: 107–116. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30407-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mauri T, Spinelli E, Scotti E, et al. Potential for lung recruitment and ventilation–perfusion mismatch in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome from coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care Med 2020; 48: 1129–1134. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ibarra-Estrada M, Gamero-Rodríguez MJ, García-de-Acilu M, et al. Lung ultrasound response to awake prone positioning predicts the need for intubation in patients with COVID-19 induced acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: an observational study. Crit Care 2022; 26: 189. doi: 10.1186/s13054-022-04064-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Musso G, Taliano C, Molinaro F, et al. Early prolonged prone position in noninvasively ventilated patients with SARS-CoV-2-related moderate-to-severe hypoxemic respiratory failure: clinical outcomes and mechanisms for treatment response in the PRO-NIV study. Crit Care 2022; 26: 118. doi: 10.1186/s13054-022-03937-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ibarra-Estrada M, Li J, Pavlov I, et al. Factors for success of awake prone positioning in patients with COVID-19-induced acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care 2022; 26: 84. doi: 10.1186/s13054-022-03950-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Avdeev SN, Nekludova GV, Trushenko NV, et al. Lung ultrasound can predict response to the prone position in awake non-intubated patients with COVID-19 associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care 2021; 25: 35. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03472-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tobin MJ, Laghi F, Jubran A. Why COVID-19 silent hypoxemia is baffling to physicians. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 202: 356–360. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202006-2157CP [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00509-2022.SUPPLEMENT (217.2KB, jpg)