Abstract

As the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns forced populations across the world to become completely dependent on digital devices for working, studying, and socializing, there has been no shortage of published studies about the possible negative effects of the increased use of digital devices during this exceptional period. In seeking to empirically address how the concern with digital dependency has been experienced during the pandemic, we present findings from a study of daily self-reported logbooks by 59 university students in Copenhagen, Denmark, over 4 weeks in April and May 2020, investigating their everyday use of digital devices. We highlight two main findings. First, students report high levels of online fatigue, expressed as frustration with their constant reliance on digital devices. On the other hand, students found creative ways of using digital devices for maintaining social relations, helping them to cope with isolation. Such online interactions were nevertheless seen as a poor substitute for physical interactions in the long run. Our findings show how the dependence on digital devices was marked by ambivalence, where digital communication was seen as both the cure against, and cause of, feeling isolated and estranged from a sense of normality.

Keywords: coping, corona, COVID-19, digital devices, lockdown, pandemic, screen time

Introduction

As the COVID-19 lockdowns came into effect across the world in the spring of 2020, some public commentators seemed to suggest that people had (or should) temporarily set aside worries over screen usage given the need to self-isolate to avoid the risk of infection. As the headline of one New York Times column (Bowles, 2020) read: ‘Coronavirus Ended the Screen-Time Debate. Screens Won.’ Phrasing the same point in a different way, two columnists in the Washington Post wrote:

Now your devices are portals to employment and education, ways to keep you inside and build community, and vital reminders you’re not alone. The old concerns aren’t gone, but they look different when people are just trying to get by (Fowler and Kelly, 2020).

As these quotes suggest, the need for social distancing during the pandemic and the subsequent need for increased digital device use dwarfed any moral concerns or panics related to screen time that have been the topic of intense discussion in recent years (see e.g. Lukianoff and Haidt, 2018; Turkle, 2016). Given that people have had to rely on their digital devices and screens for working, studying, and socializing while being in various forms and degrees of social isolation, to many it seemed like the virus had, at least temporarily, disrupted our collective screen time worries. While it is unsurprising that digital consumption reports indicate that time spent on devices and online platforms went up during the lockdowns (Nguyen et al., 2020), it remains less examined what it meant for people to be intensely and constantly dependent on digital devices and screens for doing most of their everyday things.

In this paper, we empirically address how the concern with digital dependency has been experienced during the pandemic by presenting findings from a study of university students in Copenhagen, Denmark during the first lockdown in the spring of 2020. The pandemic response in Denmark was like many other countries in around the world: in late February 2020, the first case of COVID-19 was found, and the number of new cases rose in the ensuing weeks until the government sent the country into lockdown on March 12th. For at least 1.5 months, large parts of the population worked or studied from home until society was partially reopened in May and June. In-person social interactions were advised to be limited and restricted to a maximum of 10 people in public gatherings. As people adjusted to living under lockdown conditions and found themselves confined to their homes, digital devices became the interfaces that enabled communication with the outside world. Not surprisingly then, screen time went dramatically up (Statistics Denmark, 2020).

During this first lockdown in the spring of 2020, we asked 59 university students in Copenhagen to report daily practices and how they felt in logbooks, complemented by follow up interviews. A key part of this data concerned their digital practices and their use of screens for different tasks during the day. In collecting the logbook and interview data, we aimed to investigate the following questions: In which ways did the students change their digital habits during the lockdown? How did the students react emotionally to being more dependent on digital devices than usual? And how did the students adapt their living conditions to accommodate such digital dependency?

In exploring these questions, we highlight two main findings. First, students report high levels of what we term online fatigue, expressed as frustration and apathy with using digital devices. On the other hand, students were able find creative ways of using digital devices for maintaining and nurturing social relations, enabling them to cope with isolation. These findings show how the dependence on digital devices during the first lockdown was marked by a period of ambivalent adaptation, where digital communication was seen as both the cure against and cause of, feeling isolated and estranged from a sense of normality.

The paper is structured as follows. First, we outline various reports and discussions concerning the use of digital devices and increased digital consumption during the pandemic. Second, we present the dataset and methods, describing the logbook format in detail, and how the study was carried out in practical terms. Third, we describe the students’ use of digital devices during the pandemic lockdown and what it meant for them to be dependent on devices and screens. Fourth, we explore their frustrations and even apathy toward digital dependency. Fourth, we analyze how students sought to device new strategies for socializing with friends and family via digital means. We conclude by discussing our findings in relation to how studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic can contribute to the study of digital devices and digital media in everyday life in general.

Screen time during the pandemic

Whether the lockdown did in fact change people’s perceptions of the moral concerns and health-related risks associated with (over-)use of screens – as the newspaper columns seem to suggest – remains inconclusive, to say the least (Andrews, 2020). That much is evident when looking at the flood of academic papers published within the two first years of the pandemic in psychology, public health, and related fields, which have overwhelmingly focused on the potential negative effects of people (over-)consuming digital devices and screens during the lockdowns (e.g. Vanderloo et al., 2020).

The sudden shift to an almost complete dependence on digital devices that the pandemic ushered in brought about negative consequences such as: ‘Zoom fatigue’ (Cranford, 2020; Wiederhold, 2020), strains on social relationships, mental and physical health issues and social alienation and deprivation (Iivari et al., 2020). Some studies have documented negative changes in sleep patterns during the pandemic tied to digital media use (Cellini et al., 2020), while others have sought to ascertain whether the sudden increased use of screens might lead to more digital addiction among adolescents (Gupta et al., 2020), and whether the lack of physical activity could have negative physical effects on young people’s bodies (Nagata et al., 2020). Several other papers have focused on the potential detrimental effects such as loneliness, stress, and depression caused by isolation and social distancing, and has asked to which extent digital communication have had any potential mitigating effects to prevent these effect (Ellis et al., 2020; Gabbiadini et al., 2020). In the Danish context, one study found that Danes reported more negative feelings (e.g. worry, nervousness, anxiety, depressed mood) than before the lockdown (Sønderskov et al., 2020).

Parallel to such studies that look at the potential negative effects of digital dependency during the lockdown, studies from media scholars and social scientists have cast a more nuanced light on the issue, taking point of departure in the insight we are currently in ‘a particular historical phase where the perception of the saturation with digital technology has reached a climax’ (Natale and Treré, 2020: 627). Studies have focused on how the pandemic shifted the perspective of, and possibilities for, people to disconnect from digital devices or limit their digital consumption. At the very beginning of the pandemic, for instance, Treré et al. (2020: 606) noted that in this emergency context ‘it becomes even more relevant to explore how the sudden shift to hyper-connectivity is redefining our practices, impacting our wellbeing, and redrawing the limits and boundaries of digital disconnection’. It also includes a focus on more specific aspects, such as how people’s constant need for being online in the pandemic has blurred the boundary between the professional and the private spheres (Bagger and Lomborg, 2021). Other studies have investigated how being constantly online during lockdown has transformed the experience of reality and what it means to cultivate social relations (Thorndahl and Frandsen, 2021). At a more general level, one of the central questions that confronted people during the pandemic given this intensified dependence on being connected, echoes a point by Bucher (2020), that different ethical and moral questions arise when options for actually disconnecting from digital devices is more or less non-existing. Our aim here is to add to these studies that look at the experience of being digitally dependent during the lockdown, combining a ‘thick’ dataset that is both quantitative and qualitative at the individual level, as we explain in the next section.

Methods and data

When the COVID-19 lockdown became a reality in mid-March 2020, we became interested in examining how students in Copenhagen experienced and adjusted to these new circumstances of confinement and isolation. We were especially interested in how students in Copenhagen adapted to a ‘new normal’ sense of everyday life during the COVID-19 lockdown, in which they were forced to be even more dependent on digital devices for socialization, study and work than before.

For 4 weeks from early April to early May 2020, we asked 59 young students living in different parts of Copenhagen to fill out daily logbooks. In addition, 24 of the participants were interviewed using a semi-structured interview model (Spradley, 1979), with questions that related to the answers they had given in the logbook surveys. Finally, the participants were asked to answer a set of evaluation questions after the final day of filling out logbooks were completed. The participants comprise both Danish and international students who live in Copenhagen. They range from 22 to 31 years of age (median = 24 years old). Out of the 59 participants, 46 reported themselves as women and 13 as men. Our data consists of two subsamples: (1) students living in a dormitory and (2) students living in private apartments, either owned or rented. The dormitory participants were recruited through a Facebook group from where 34 of the residents volunteered. We further recruited students mainly via the University of Copenhagen with a minor snowballing effect in their networks, out of which 25 students volunteered.

The logbooks were distributed and collected weekly. They were altered mid-way due to technical issues the first 2 weeks, which creates small differences between weeks 1–2 and weeks 3–4. They were sent to the participants as an Excel spreadsheet divided into tabs for each day. On the first day, participants provided a range of background information, including place of birth, field of university study, etc. They were then asked daily to note down the time they went to sleep and got up, how many people they interacted with both online and offline, their mood via a choice of emojis, thoughts about corona risks, number of hours spent on a screen, and a variety of other questions. A full overview of the questions asked can be found in Figure 1. For some questions, the participants had to choose between predetermined categories such as agreeing or disagreeing with statements or indicating how much they had thought about corona that day on a scale of 1–10. This numerical data makes it possible to quantify several temporal developments for all participants. Three open answer text fields in the logbooks also gave the young people the opportunity to answer in detail with their own words in relation to how their day had been, how they spent their time on screens as well as other observations or reflections they may have had. The result is a qualitative data set of words and sentences written in the participants’ own words.

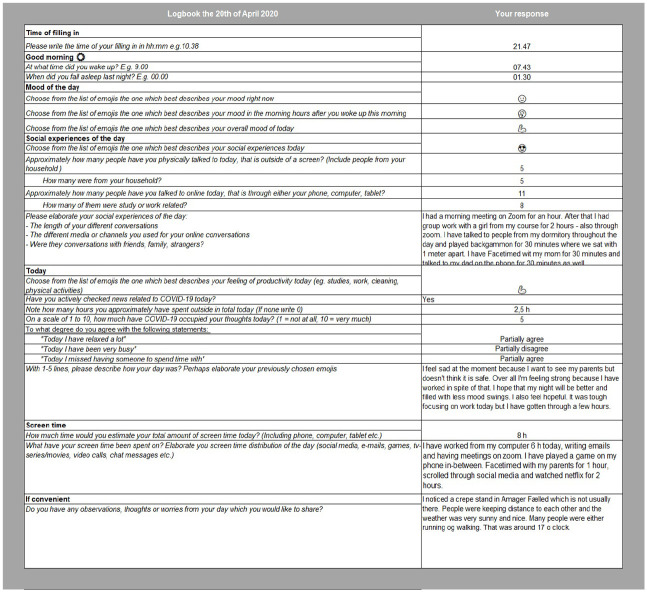

Figure 1.

Questions and answer categories included in the logbook sent to study participants in left column. Example of answers given by one study participant on 1 day in right column.

Logbooks are an effective way for participants to easily provide data over a longer period with relatively fine-grained resolution. The daily logbook method resembles the interviewing and surveying techniques found in experience sampling methods or ecological momentary assessments in which the aim is to gather data about how participants go about their days and what they think for several consecutive points in time, creating a rich longitudinal dataset (Salkind, 2010). The logbook does however differ from traditional experience sampling approaches, as these often seek to ask about momentary thoughts and actions, and most often use short, closed questions. In this sense, the daily logbooks used in this study can be thought of as ‘thick surveys’, consisting of both numerical questions (e.g. ‘how many hours did you sleep last night?’) and open-ended questions that can be answered with several lines of reflections (e.g. ‘what have been the best parts of your day, and why?’). This caters for a ‘thicker’ survey dataset that is thus ethnographic in character, but which can be analyzed using programing techniques and descriptive statistics (Albris et al., 2021). Moreover, since the participants in our case were asked to fill out the open answer categories as extensively as possible, the logbooks in this case also resemble diaries (Hyers, 2018). This survey format, we contend, is well suited to studying everyday practices especially in situations where research must be conducted remotely, as was the case for this study, since we could not be in physical proximity to the participants because of the lockdown. The logbook is also an effective way to collect both quantitative and qualitative data from a relatively small group of research participants, creating possibilities for triangulation and validation. Finally, the combined value of the logbooks and interviews provide for a rich qualitative and quantitative empirical material, allowing for remote ‘thick’ observations (cf. Geertz, 1973).

Given the duration of the data collection (4 weeks), we can only give a temporal snapshot of the students’ thoughts and actions. As we have no baseline to compare with, we cannot know how these people normally use digital devices or what role screens played in their lives before the lockdown period. We can, however, to a certain extent glean their pre-corona practices through the in-depth answers that the participants gave in the logbooks as well as in the follow-up semi-structured interviews, where we asked them about the role or digital devices and social media in their lives in general. All participants in the study consented and were informed about their rights as data subjects, including the purpose of the study and their right to withdraw.

Digital dependence

As they went into lockdown, the students quickly had to rearrange their lives, thereby becoming dependent on digital and online communication. Although members of this demographic group (ages ranging from 18 to 25) were already among the most avid digital users (Andersen et al., 2021) they now had to establish a life of social, work and study related activities mediated almost entirely through digital devices, using various communication software (Zoom, Skype, Teams, etc.) and social media platforms (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, etc.). As was the case for many people around the world, the students were more or less ‘forced’ to sit in front of screens at home, watching lectures or participating in study group meetings instead of going to university or socializing with fellow students. This is what we take digital dependence to be in the context of this study: a non-voluntary dependence on digital devices and platforms for social interactions across all spheres of social life.

In this first section, we look at the digital practices and habits of the students during the lockdown. In doing so, we shift between presenting aggregated measures across all participants and qualitative portrayals of individual experiences through quotes. This includes looking at how many daily online versus offline interactions they report having had, as well as whether they reported having missed someone to spend time with (what we term ‘social deprivation’). Incidentally, we calculate social deprivation from the question ‘To what degree do you agree with the following statements: c)’ ‘Today I missed having someone to spend time with’: [Disagree, Partially disagree, Neither/or, Partially agree, Agree]’. We believe that the social deprivation – or the feeling of being deprived of social relations and stimulus – is more neutral than a term such as loneliness, which connotes a stronger sense of social ‘anomie’.

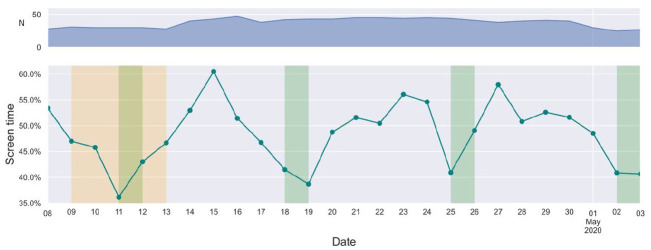

Figure 2 shows the average hours the students reported spending in front of a screen of a digital device as a percentage of their waking hours. They reported spending approximately between 35% and 60% of their time looking at screens. What is immediately clear is that there are differences between their screen time between weekdays and weekends. We might presume that this indicates that the students wanted to take more breaks from online communication by working and studying less during weekends. It might also mean, as we will return to, that the few physical interactions they still had, were prioritized during weekends.

Figure 2.

Top graph: the total number of participants having filled out data for screen time for each given day from 8th of April to 3rd of May, 2020. Bottom graph shows the mean amount of screen time for participants per day as a percentage of mean number of hours awake during that day. Y-axis shows range from 35% to 60%. Heavy shading indicates weekends, medium shading indicates Danish Easter holiday (9–13 April 2020).

For many participants, a typical day would unravel in front of a screen in the same physical setting but through different digital channels and virtual spaces. Digital devices were no longer mere tools for taking notes, writing assignments, or watching entertainment. Their computers, phones and tablets became interfaces through which they ‘went to university’ and ‘went to work’ as well as places where they meet up with their friends. The following quote provide examples of how one participant spent her time:

Writing with friends on Facebook Messenger, writing with the board of my students’ association I’m part of on Facebook Messenger, Snapchat, watched the Prime Minister’s press meeting, watched tv-series on Viaplay, played computer games, used Spotify to listen to music, looked at my news feed on Facebook, read random articles about celebrities on Buzzfeed (Logbook entry April 24th, 2020, participants number #41 1 ).

At the experiential level, many report that activities on digital devices became indistinguishable from one another in the flow of a day. Minor things such as checking the time (participant #60) or using a calculator (participant #54) on the phone quickly led to subsequent minutes spent scrolling through social media. This is important to note, since the use of simple activities on their digital devices ‘pulled’ and retained their attention (Throop and Duranti, 2015) toward more time-consuming activities, making them more prone to be constantly fixated and attuned toward their digital devices.

While much of the screen time is still spent on activities that they would normally do, such as scrolling through social media, gaming or streaming, the significant change lies in how they report a markedly intense increase in those different uses from before the pandemic. This is evident in quotes such as these, where they report being surprised by how much time they spend on social media: ‘I don’t know how many meters of Facebook I have scrolled but it has come down to a lot’. (Interview April 23rd, 2020, with participant number #46). While the fact that one’s attention is drawn toward social media using other tasks is of course not particular to the lockdown situation, the experience of being drawn toward such activities attains a different character when one is spending more time online overall. For several students, having to work from home meant more often checking Facebook and Instagram. These participants (#5, #11, #31, #69) report that they would not normally use social media during work hours, but when at home, the work-private life boundary became blurred. Having to use social media as the primary way to stay involved in others’ lives and retaining a sense of social interactions during days spent at home quite simply meant spending a lot more time than usual on social media platforms. Some reported notifications as being especially distracting, but also necessary, as they felt they had to be connected when they were not physically present with their colleagues or fellow students. This participant phrases that concern in the following way:

Screen time wise I think that I have become more addicted to my phone now than I was before. But that is also because every time I want to talk to somebody, I’m dependent on having my phone to check their reply, right? (Interview May 4th, 2020, with participant number #16)

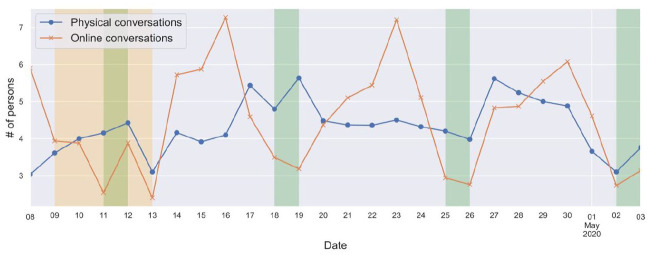

While much of their social interactions were relegated to online communication, most participants also kept having offline interactions with people they either lived with in their dorm or apartment, or with close friends and family members, whom they felt safe being around. Figure 3 shows the mean average of online interactions and offline (physical) interactions that participants reported having had during the data collection period. As is clear, there is a slight pattern that online interactions tend to go up mid-week and drop during the weekend. The signal is less strong for offline interactions, but for at least one of the weekends (April 18–19th), these interactions also went up. This seems to suggest that the students took breaks from online interactions during the weekends, instead either having fewer overall interactions or slightly more offline interactions, which corresponds to the data on reported screen time as presented earlier in Figure 2. The key finding is that, relatively speaking, the participants report having far more online interactions during weekdays than in weekends.

Figure 3.

Mean number of persons the participants have interacted with on a given day. Online interactions are via video, mail or chat, and offline interactions are when they are in physical proximity to another person.

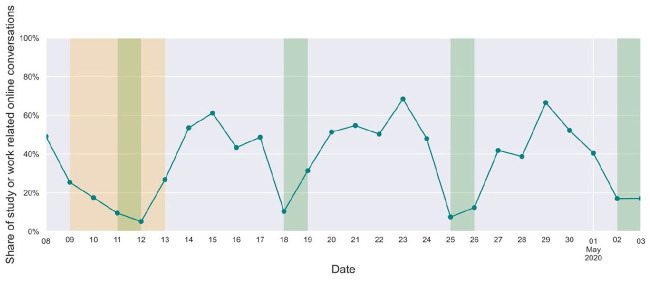

The same pattern of weekday/weekend differences can be reconstructed in the types of online interactions that the participants engaged in. Figure 4 shows that during the weekends, study and work-related interactions only accounted for approximately 20% of all online conversations, whereas the figure fluctuates between 40% and 60% during the weekdays. This indicates, not surprisingly perhaps, that the students spent more time on work and study related activities during the weekdays, which accounts for the higher number of overall online interactions during weekdays as shown above in Figure 3.

Figure 4.

The mean share of work or study related online conversations from April to May 2020.

These initial descriptions of the students’ digital practices illustrate a sense of ambivalence: on the one hand they report that the ‘forced’ reliance on digital devices and screens was a challenge, both in terms of being constantly pulled toward online platforms, especially social media, and the sheer amount of time spent on digital devices. At the same time, however, the quantitative data that they reported on their screen time and online interactions suggest that many of them tried to create some form of everyday stability, most evident in the differences between their digital device use between weekdays and weekends.

In the next two sections, we delve deeper into two themes that act as prisms into the ways that the participants tried to adapt to an increasingly digitally dependent lifestyle: a sense of online fatigue leading to frustration and apathy, and strategies for coping with isolation by socializing with friends and family.

Online fatigue and ‘Bad Screen Time’

Several students reported in their logbooks that they had been concerned with their own screen time, and especially social media use, already prior to the pandemic. As such, the lockdown situation was accompanied by a feeling that any efforts to change their digital habits had been set back to square one. As one student notes in a follow up interview:

I’ve always tried to limit myself because I feel that I use social media too much. I was good before corona came, and then when it came, and I had nothing to do, then I’d just sit there, looking at Facebook and Instagram for hours (Interview April 29th, 2020, participant number #22).

In the logbook entries, we often find frustrations given that digital devices have become an inevitable part of daily routines. Participants reported feelings that can be conceptualized as good and bad screen time. Good screen time predominantly referred to the digital devices as socializing interfaces (as we shall see in the next section) or for work and study, in which they add some value to the person’s daily life. Bad screen time, by contrast, involves reports such as the feeling of endless scrolling, surfing the web without any aim or checking the news in unfocused ways. Bad screen time can be boiled down to activities which participants perceive as ‘wasted time’, or time that could have been spent productively, meaning that it would have had a certain purpose by giving them a sense of progress over a day. While such bad screen time is, arguably, not specific to the pandemic lockdown situation as such – being a feeling that users of digital devices can be assumed to report at any point in time – here we take note of the fact that the isolation and digital dependence further added fuel to the fire. When the participants do not achieve their intended goals for the day, it left many feeling unproductive, creating a sense having let themselves down, which they often relate to life as being disorderly:

My circadian rhythm is turned upside down. I slept until late in the afternoon and still I felt tired when I woke up. I haven’t really achieved anything. I have only watched tv series and played computer games. It is hard to find the motivation to study (Logbook entry April 7th, 2020, participant number #41).

The context created by the lockdown of working from home and not being able to meet with friends created ripe settings for the students to struggle with their ability to concentrate, and hence for digital activities to distract them. Boredom and fatigue, or being fed up with online communication, was reported as a main reason for spending unproductive time on screens, especially on social media. Echoing what Paasonen (2021) has recently called attention to, we might say that digital devices enmeshed the students in boredom and distraction precisely because they became more dependent on them during the pandemic. One participant describes her own behavior in the following pathologizing way:

I’ve noticed that I sometimes just swipe between pages on my phone just to find something to do, because by now I’ve seen all of Instagram and Facebook and 9gag and whatever else I usually go to. It almost becomes psychotic (Interview April 29th, 2020, with participant number #52).

As indicated, participants also report a widespread fatigue with digital devices as something that they necessarily must go through to function as social beings. The ambivalence is once again apparent since the screen which used to be a tool for studying as well as entertainment has now become an unavoidable mediator for most of their tasks and needs, meaning what while that while they before the pandemic had greater flexibility in detaching themselves from social media and digital communication in general, under the lockdown most, if not all, students report that this flexibility is less available to them.

The case of Kathrine (pseudonym), 22-year-old bachelor student, is exemplary. She reports how the increased amount of time spent on digital devices during the lockdown has led her to change other aspects of her routines, such as switching from screen related entertainment to audio books whilst going for a walk. In an interview, she notes that:

Before (the lockdown red.), I could sit and watch a movie on my computer in bed, whereas now I prefer not to do so. Now it just has to be put away when the workday is over because I’ve spent so much time on it (Interview April 28th, 2020, with Kathrine).

In the interview we conducted with her, she links this change to her now intensified relationship with her screen. For her it is not only the number of hours but also the frustrations connected to her study group or with lectures, where both technical issues as well as disagreements talked out virtually, that have changed her relationship to digital device screens. In one of her logbook entries from the 14th of April, she states that ‘I have reached a state where I hate virtual work’. At the time she described how the transition from normal ways of studying into virtual had caused her to not enjoy school because of all the frustrations now linked to her screen. This led her to distance herself from her phone during the Easter holiday:

Before Easter, I was stressed so I didn’t have my phone on me the entire Easter. That was when I had my dad help me with making a coffee table to get away from it and I made ceramics with my mom to have something else be there instead of those screens (Interview April 28th, 2020, with Kathrine).

Kathrine’s case is exemplary of a general sense of what we earlier have called online fatigue: a sense that while digital communication was seen by students as being a necessary means of coping with social isolation, they reported being tired of having to communication with friends, family members and fellow students through screens. However, some of Kathrine’s decisions to willfully try to limit her screen time is also indicative of the ability of many students to exert agency in trying to adapt to these new circumstances. We explore other ways that the students did this in the next section.

Coping strategies and online sociality

For the students, digital devices became crucial not just for work and study, but also for maintaining social relations and for coping with the often-stressful circumstances of the pandemic. Social interactions – whether online or offline – were seen as vital to many, not least to counter feelings of isolation, loneliness, or merely feeling deprived of social interactions (cf. Sønderskov et al., 2020). However, the relationship between online interactions and feeling of social deprivation indicate an interesting trend in the dataset as we shall see.

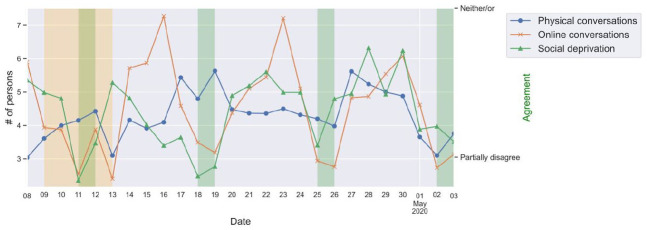

In Figure 5, graphs for the development of both online and offline interactions are shown alongside participants’ reported levels of social deprivation. Here we see that the general level of social deprivation throughout the period is rather low, fluctuating between neither/or and just below partially disagree. Social deprivation seems to generally be lowest during the weekends and rising during the weekdays. While there is no clear correlation between the number of online/offline conversations and social deprivation, some points in the period are noteworthy. For the second weekend during the 18th and 19th of April the participants reported interacting with many people offline, while almost having no online interactions, and consequently low level of social deprivation. Comparing Thursday the 16th of April with Thursday the 23rd of April we see the same kind of spike in online conversations, but with a higher level of social deprivation at the latter day. Looking back at Figure 4, we see that a greater share of the online conversations on the 23rd were study or work related, which might not pose the same social satisfaction. However, overall, the quantitative correlations seem to be rather spurious.

Figure 5.

Mean number of physical and online conversations or the left y-axis and social deprivation on the right y-axis.

While the increased amount of digital screen time led to reports of frustrations and of not being able to concentrate as we described in the previous section, a central theme being reported by almost all study participants revolve around coming up with innovative ways of maintaining and establishing social relations online, but also offline to the extent possible, and how they made use of creative solutions to do so. Meeting with other people through screens enables a myriad of possibilities for social interactions, and there are variations in the activities the participant partakes in. Examples from the lockdown period that perhaps stand out from pre-lockdown times are coffee dates, board games, sing-alongs, and Easter celebrations in the form of large lunches with family or friends via Teams, Facetime, Skype or Zoom. It entails both familiar activities translated into online formats but also completely new types of social activities that for some became regular routines during the lockdown. The number of participants in these gatherings varies from two or three people, to larger activities with 20 or more. Two participants describe the online social activities as easily accessible because they just need to open their computer or phone: ‘It has been a good day today where I’ve caught up with an old friend on video call which we never really did before [lockdown] when you had to find a date and meet up physically’ (Logbook entry April 15th, 2020, participant number #59); ‘Today I had a long video call with some friends, and we played “Never Have I Ever”. It was extremely fun, and we played along and drank wine at the same time’ (Logbook entry April 20th, 2020, participant number #12). Despite such positive experiences of using online interactions in creative and new ways, the increased social use of devices created a sense of ambivalence. Many report that social interaction through a screen is both positive and meaningful, but that it cannot compensate for the intimacy one gets through offline interactions. Thus, although many students report positive sentiments, they also find it difficult to interpret facial gestures and body language through the screen, making it difficult to converse without interruptions. Socializing through screens necessarily entails a distance between the participants communicating which makes it challenging to have intimate conversations and maintain close ties. In addition, the challenges involved in socializing through a screen lead to new types of questions about what makes a friendship as rules of the game have been changed, as one participant notes: ‘I tried having a zoom-party one day. That was kind of annoying because everyone was talking at the same time. It was with pretty close friends, and we usually have parties together every Friday’ (Interview April 24th, 2020, with participant number #44). In a similar vein, another participant reflects on the apparent disruption to what a friendship tie or relation means when interactions have become forced to be channeled through a digital medium:

Nice to have a Zoom meeting with the study group, but it is difficult for me to figure out the social through a screen. Are we friends or not if all of our conversations take place over Zoom and Facebook? (Logbook entry April 29th, 2020, participant number #61).

The case of Laura (pseudonym) is indicative of how students adapted in creative ways to being dependent on digital communication for being social during the lockdown. Laura is 24 and currently pursuing a master’s degree at The University of Copenhagen. She lives in an apartment with her boyfriend. They have chosen to mainly socialize physically with both parents during the lockdown, which also means that Laura primarily maintains relationships with friends online. During the period, however, she meets a few times with friends for a walk, but she predominantly communicated with friends via video calls (i.e. Skype, Zoom or Teams). Figure 6 shows Laura’s daily screen time. The amount of time Laura reports spending on screens is mainly between 20-45% of her waking hours, with some outliers, which is at the lower end of the scale compared to other participants. Laura reports a slight overall increase in screen time across the data collection period.

Figure 6.

Amount of screen time as a percentage of hours awake during a day for Laura (participant #16). Gaps in the figure indicate days Laura forgot to log her screen time.

In an interview, Laura explains that she started doing daily fitness exercises with her friend. Each morning, they follow a fitness video instruction and simultaneously converse through video-call. Laura doesn’t usually work out every day, but during the lockdown this became a regular routine, and the two friends now talk more frequently than before.

Apart from fitness sessions, Laura also meets up online with friends to drink wine, play bingo and attend a dinner club. Laura emphasizes the importance for her in keeping up with friends during lockdown, and she is excited about the new kinds of online social initiatives and the possibilities of the social screen: ‘I would like to attend more of such initiatives because I think it is cool that people come together in different ways than we usually do’ (Interview May 4th, 2020, with Laura). Laura is impressed by how successful socializing through a screen has been, and she remarks that in the case she travels abroad for a longer period it is nice to know that it is possible to maintain acquaintances through online platforms. Despite her positive experiences with the social screen Laura expresses frustration over lack of offline interaction with her friends: ‘The five minutes I spent talking to a friend [offline] made a big difference for my day’ (Logbook entry April 8th, 2020, Laura). As such, Laura is like many other students in the research project, in that she prefers offline social interaction and having physical contact: ‘I have started to value even a short conversation face to face’. (Logbook entry April 20th, 2020, Laura).

Finding new and creative ways of socializing online during the pandemic, can indeed be seen, we argue, as a social coping strategy aimed at mitigating feelings of digital fatigue and a general sense of apathy. Although we do find that participants in fact sought to strengthen existing friendship ties and even sought to revive older friendships, this online social existence nevertheless also put a strain on their sense of feeling connected to others, and as such, online interactions also seemed to reinforce the feeling of being isolated from friends and family. As such, the digital devices and online platforms both presented a way for socialization to continue and to be innovated, as much as it also creates a sense of distance.

Discussion and conclusion

Whether or not one would normatively agree that people ought not to worry about the time spent on screens, it is an entirely different question of how people experienced this increased dependence on digital devices during the lockdown either negatively or positively, or as an ambivalent mix of both. Based on the analysis of the logbook and interview data that we have presented in this paper; we have argued that the increased use of digital devices during the lockdown was accompanied by various forms of ambivalence. As the lockdown abruptly intensified the need for people to rely on digital devices and screens in their daily lives to an unprecedented degree, people were unable to adjust in a gradual manner, which led to many frustrations.

In our analysis we show how the lockdown instigated a continuum of mixed emotional and affective responses toward digital devices that had now become both the means through which one’s life could continue in some form, and as a source of frustration and apathy. For the study participants, this meant renegotiating and compromising to deal with the frustrations associated with being isolated and having digital devices as the only mediators of social relations and work activities. The lockdown thus presented the participants in this study with a challenge: they are forced to embrace screens to a larger extent than before the lockdown. At the same time, most, if not all, participants report being tired of their devices, even hating their computers. Some students were able to adjust and adapt in constructive ways, especially when it came to maintaining social relations. Nevertheless, our findings thus suggest that the lockdown created both positive and negative responses to this greater dependence on screens and digital devices. Most centrality, we find that the students’ dependence on digital devices can best be described as an ambivalent form of adjustment to the realities of the pandemic, in the sense that digital communication was seen as both the solution to feeling isolated and lonely, while at the same time reenforcing and reminding people of the digitally meditated social distance that existed between them and their networks of friends and family.

As a reflection that follows from this last point and which speaks to the study design, for several participants the logbook itself became a form of diary, which helped to shape their perception of the rhythms of everyday life. In asking participants to log elements of their everyday lives such as screen time, we simultaneously forced them to become more aware of changes to their habits. In some cases, participants noted that this prompted them to want to change their habits, especially regarding screen time and digital devices. It could be argued that the participants’ screen time habits may have looked different had they not been noting them in the logbooks. On the other hand, getting an insight into the way our participants dealt with this newfound awareness through their daily deliberations and post-study evaluations allowed us to explore one of the ways they negotiated the role of digital devices in their everyday lives in this period, a central element of our analysis.

Looking beyond the pandemic, a key perspective on digital dependence as we have discussed it in this paper would be to study to which extent online communication for working and studying are become even more widespread than before the pandemic, as people have become more accustomed to platforms such as Zoom or Microsoft Teams. Importantly, it will of course be difficult to ascertain whether there is a contribution of a potentially lasting effect of the COVID-19 lockdown, not only on young people and students, as has been the focus of this study, but all who became more dependent on digital devices during the pandemic. Future research should also focus on risk factors and benefits associated with the changes in our (digital) everyday lives that COVID-19 has brought upon us (Fenwick et al., 2020; Gabryelczyk, 2020), particularly if these new digital communication methods are adopted long-term in both vocational and private settings.

Given potential sensitivity in the data the logbook entries, all respondents were ensured anonymity and therefore detached from their name from the very beginning so only one member of the team were in contact with them and could reidentify their logbooks if needed. Going through the data, each researcher only encountered a participant number to distinguish the logbooks from each other. It is this participant number, we report with each quote to give some sense of individuality for the reader as we refrain from pseudonymizing each respondent (except for two cases later on), presenting a quote as is.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The research is supported by funding from the H2020 European Research Council (grant number 834540) as part of the project The Political Economy of Distraction in Digitized Denmark (DISTRACT).

ORCID iDs: Emilie Munch Gregersen  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6912-0922

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6912-0922

Kristoffer Albris  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1201-2231

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1201-2231

References

- Albris K, Otto EI, Astrupgaard SL, et al. (2021) A view from anthropology: Should Anthropologists fear the data machines? Big Data & Society 8(2): 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen CW, Tassy A, Pedersen M. (2021) Det digitale Danmark – et statistisk portræt. Samfundsøkonomen 1, March. Djøfs Forlag. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews TM. (2020) Our IPhone weekly screen time reports are through the roof, and people are ‘horrified’. Washington Post, 24March. [Google Scholar]

- Bagger C, Lomborg S. (2021) Overcoming forced disconnection: Disentangling the professional and the personal in pandemic times. In:Chia A, Jorge A, Karppi T. (eds) Reckoning With Social Media. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, pp.167–188. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles N. (2020) Coronavirus ended the screen-time debate. Screens won. The New York Times, 31March. [Google Scholar]

- Bucher T. (2020) Nothing to disconnect from? Being singular plural in an age of machine learning. Media Culture & Society 42(4): 610–617. [Google Scholar]

- Cellini N, Canale N, Mioni G, et al. (2020) Changes in sleep pattern, sense of time and digital media use during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. Journal of Sleep Research 29(4): e13074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranford S. (2020) Zoom fatigue, hyperfocus, and entropy of thought. Matters 3(3): 587–589. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis WE, Dumas TM, Forbes LM. (2020) Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. Revue Canadienne des Sciences Du Comportement 52(3): 177–187. [Google Scholar]

- Fenwick M, McCahery JA, Vermeulen EP. (2020) Will the world ever Be the same after COVID-19? Two lessons from the first global crisis of a Digital Age. European Business Organization Law Review 22: 125–145. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler GA, Kelly H. (2020) ‘Screen time’ has gone from sin to survival tool. Washington Post, 9April. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbiadini A, Baldissarri C, Durante F, et al. (2020) Together apart: The mitigating role of digital communication technologies on negative affect during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 554678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabryelczyk R. (2020) Has COVID-19 accelerated digital transformation? Initial lessons learned for Public Administrations. Information Systems Management 37(4): 303–309. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz C. (1973) The Interpretation of Cultures. New York, NY: Basic books. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta T, Swami MK, Nebhinani N. (2020) Risk of digital addiction among children and adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic: Concerns, caution, and way out. Journal of Indian Association for Child & Adolescent Mental Health 16(3): 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Hyers L. (2018) Diary Methods: Understanding Qualitative Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iivari N, Sharma S, Ventä-Olkkonen L. (2020) Digital transformation of everyday life – How COVID-19 pandemic transformed the basic education of the young generation and why information management research should care? International Journal of Information Management 55: 102183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukianoff G, Haidt J. (2018) The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure. London: Penguin UK. [Google Scholar]

- Nagata JM, Abdel Magid HS, Pettee Gabriel K. (2020) Screen time for children and adolescents during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 pandemic. Obesity 28: 1582–1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natale S, Treré E. (2020) Vinyl won’t save us: reframing disconnection as engagement. Media Culture & Society 42(4): 626–633. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen MH, Gruber J, Fuchs J, et al. (2020) Changes in digital communication during the COVID-19 global pandemic: Implications for digital inequality and future research. Social Media + Society 6: 2056305120948255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paasonen S. (2021) Dependent, Distracted, Bored: Affective Formations in Networked Media. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salkind NJ. (2010) Encyclopedia of Research Design, vols. 1-0. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Spradley JP. (1979) The Ethnographic Interview. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Denmark (2020) Proportion of Individuals Using the Internet. Copenhagen: Government of Denmark. [Google Scholar]

- Sønderskov KM, Dinesen PT, Santini ZI, et al. (2020) The depressive state of Denmark during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Neuropsychiatrica 32(4): 226–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorndahl KL, Frandsen LN. (2021) Logged in while locked down: Exploring the influence of digital technologies in the time of Corona. Qualitative Inquiry 27: 870–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Throop CJ, Duranti A. (2015) Attention, ritual glitches, and attentional pull: The president and the queen. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 14(4): 1055–1082. [Google Scholar]

- Treré E, Natale S, Keightley E, et al. (2020) The limits and boundaries of digital disconnection. Media Culture & Society 42(4): 605–609. [Google Scholar]

- Turkle S. (2016) Reclaiming Conversation. The Power of Talk in a Digital Age. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderloo LM, Carsley S, Aglipay M, et al. (2020) Applying harm reduction principles to address screen time in young children amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics 41(5): 335–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederhold BK. (2020) Connecting through technology during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 pandemic: Avoiding “Zoom Fatigue”. Cyberpsychology Behavior and Social Networking 23(7): 437–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]