Abstract

Background

Ensuring safety and wellbeing of all the minority populations of Pakistan is essential for collective national growth. The Pakistani Hazara Shias are a marginalized non-combative migrant population who face targeted violence in Pakistan, and suffer from great challenges which compromise their life satisfaction and mental health. In this study, we aim to identify the determinants of life satisfaction and mental health disorders in Hazara Shias and ascertain which socio-demographic characteristics are associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Methods

We used a cross-sectional quantitative survey, utilizing internationally standardized instruments; with an additional qualitative item. Seven constructs were measured, including household stability; job satisfaction; financial security; community support; life satisfaction; PTSD; and mental health. Factor analysis was performed showing satisfactory Cronbach alpha results. A total of 251 Hazara Shias from Quetta were sampled at community centers through convenience method based on their willingness to participate.

Results

Comparison of mean scores shows significantly higher PTSD in women and unemployed participants. Regression results reveal that people who have low community support, especially from national and ethnic community, religious community, and other community groups, had higher risk of mental health disorders. Structural equation modeling identified that four study variables contribute to greater life satisfaction, including: household satisfaction (β = 0.25, p < 0.001); community satisfaction (β = 0.26, p < 0.001); financial security (β = 0.11, p < 0.05); and job satisfaction (β = 0.13, p < 0.05). Qualitative findings revealed three broad areas which create barriers to life satisfaction, including: fears of assault and discrimination; employment and education problems; and financial and food security issues.

Conclusions

The Hazara Shias need immediate assistance from state and society to improve safety, life opportunities, and mental health. Interventions for poverty alleviation, mental health, and fair education and employment opportunities need to be planned in partnership with the primary security issue.

Keywords: Hazara Shia, Life satisfaction, Mental health, Community support, Pakistan

Introduction

Hazara Shia migration to Pakistan and Victimhood

The first phase of mass migration of Hazara Shias from Afghanistan to Pakistan occurred 150 years ago, in the 1880s, due to persecution in the reign of King Abdur Rehman (European Asylum Support Office, 2015). The second phase of migration to Pakistan happened in 1979 during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan and the third phase in 1996 when the Taliban came into power (National Commission for Human Rights, 2018). The Hazara Shias can be found in different provinces of Pakistan post migration, including Punjab, Sindh and Gilgit-Baltistan, but the majority live in Balochistan.

Recent reports state that there are up to 1 million Hazara Shias living in Pakistan, of which 0.7 million live in Balochistan (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Report, 2022). Other reports claim that the population of Hazara Shias in Balochistan is approximately 0.4 to 0.5 million (National Commission for Human Rights, 2018; Human Rights Watch, 2014). Lack of confirmation about the number of Hazara Shias in the country negatively influences policy planning and the importance given to the critical challenges they face, the first of which is targeted attacks and killing. Noncombatant Hazara Shias of Pakistan have been subjected to extreme violence and persecution from extremist bodies for their sectarian beliefs and minority status (Ahmad Wani, 2019). The persecution also escalated after 9/11 due to the effects of Talibanization and religious intolerance against the Shia sect (Adams et al., 2014).

Perpetrators include Sunni extremist groups, such as the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, and Baloch ethno-nationalist insurgency groups (Ali, 2021). However, state detachment and inability to prosecute perpetrators has also led scholars to claim that the state is complicit in the violence against the Hazara Shias of Pakistan (Ahmad Wani, 2019). Police reports or lodging complaints is not known to gain Hazara Shias justice, and their experience in seeking support from community bystanders or legal authorities has remained ineffective (National Commission for Human Rights, 2018). Known perpetrators against the Hazara Shias have not been punished either due to their strong religious or political affiliation or the poor judicial system. Either way, lack of justice and protection from state and society has contributed to more than a century worth of fear and insecurity in the migrant community.

Theoretical background

We use the trauma-based medical model to argue that when migrants face post-migration violence and abuse, they end up suffering from stress and other mental health challenges (Ryan et al., 2008). The model elaborates that when migrants face traumatizing and stressful experiences such as lack of employment, community acceptance, and witnessing death of loved ones hey can experience compounding mental health issues. We further use need-gratification theory, to show that when migrants face inequalities and deprivation in basic needs such as economic resources, community support, and access to adequate housing, they experience less life satisfaction and overall wellbeing (Adler, 1977). Lack of citizenship status and abuse can combine to influence both mental health and quality of life of migrants and prevent their agency in combatting injustices, implying that the role of researchers and majority population groups is paramount to raise awareness for their protection (De Vroome and Hooghe, 2014).

Life circumstances in Ghettos of Quetta

Housing

Hazara Shias are predominantly found in two neighborhood areas of the Balochistan's provincial capital city of Quetta- Hazara Town and Marriabad. Due to the targeted and random attacks Hazara Shias are forced to remain in ghettoized zones of Quetta (Goodall and Hekmat, 2021). These neighborhoods are characterized as low-income areas with bad housing quality and inadequate access for schooling, health services and job opportunities (Majeed, 2021).

Job satisfaction

Restrictions on mobility due to safety concerns has crippled the community's ability to advocate for themselves, gain better opportunities for education, or receive information for better job opportunities or business expansion (Majeed, 2021). The constant threat of attacks and insecurity has especially affected the mobility of women and girls, who are less likely to pursue higher education and work outside the home (Sultan et al., 2020; Changezi and Biseth, 2011).

Financial security

Initially, the Balochistan government provided job opportunities to the Hazara Shia community on open merit and the share for Hazara Shias in the civil services was 50%. However, in 1972 a quota system was introduced which reduced the share of jobs for the Hazara Shias to 5% by 2011. Due to this the Hazara Shia's have minimum representation in the civil services and do not have a political voice to mobilize protection or equal opportunities (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Report, 2022). Most Hazara Shias also avoid applying for or private sector and government jobs due to fear of attacks or discrimination, crippling their options for growth further (National Commission for Human Rights, 2018). Due to limited mobility and options for private and government employment, majority Hazara Shias are involved in small businesses that do not reap much profit and are difficult to sustain due to the discrimination facing them (National Commission for Human Rights, 2018). This is why majority of Hazara Shias face impoverishment and financial insecurity (Majeed, 2021).

Community support

Many Hazara Shias are not given jobs, allowed on public transport, or entertained as clients in shops, due to fear that in random attacks against them casualties may also suffer the consequences (Siddiqi, 2012). Community support overall is low, as people fear becoming bystander victims by associating with Hazara Shias. This social discrimination adds to the exclusion and difficulties faced by the community. Many family members of Hazara Shias in Pakistan have further migrated to other countries in search of better opportunities and so they can send finances back home to their family (Ali et al., 2016; Tan, 2016; Radford and Hetz, 2021). In this way, many Hazara Shias in Pakistan suffer from separation from family members due to both targeted killing as well double migration (Koser and Marsden, 2013). This can contribute to mental health challenges and social disintegration for the community already having to deal with grave problems due to violence and victimhood (Brown, 2017; Parkes, 2020).

Post-traumatic stress disorder and mental health

Constant fear of facing violence and brutal killings, and loss of loved ones and family members is a cause of high post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in Hazara Shia community for many years (Lee A, 2002; Zarak et al., 2020). The mental health problems and fear faced by Hazara Shias is compounded by their experiences of being witnesses of violent persecution against their community members or suffering from the loss of a significant family member (National Commission for Human Rights, 2018). Some research also highlights that community members may face high rates of depression and suicide ideation (Mares, 2014). More vulnerable groups for emotional and health challenge risks in the community may include women, younger people, and the unemployed (Ahmad, 2020; Rose, 2002). There are no safe zones for Hazara Shias, who are known to be attacked in public spaces, residential areas, schools, workplaces, places of worship, government offices, police stations, and hospitals (Human Rights Watch, 2014). There are only two main hospitals of Quetta, situated in the unsafe zone with history of attacks against Hazara Shia patients seeking emergency care or other health services (Zarak et al., 2020). Thus, Hazara Shias face both access and cost barriers to seeking healthcare or emergency health services at the time of the attacks.

Life satisfaction

Residents living, working and studying in Quetta face daily uncertainty about whether they will return home alive if they leave the house (Khan and Amin, 2019). Due to the high incidents of persecution and lack of opportunities in Quetta, many try to migrate to other provinces of Pakistan if they are able to gain the opportunity through scholarships or jobs (Siddiqi and Mukhtar, 2015). Nearly all the Hazara Shias are poor and coupled with problems of insecurity they usually have high rates of dropouts during schooling or low participation in business activities (Changezi, 2011). Some reports claim that around 80 to 90 percent students drop out of academic institutes and majority remain restricted to the home or the ghettoized neighborhoods of Quetta to escape assault (Sultan et al., 2020). Apart from low qualifications and specializations, another factor that prevents life advancement for Hazara Shia migrants are language barrier (Brahmbhatt, 2007). Lack of fluency in English, the official working and study language for Pakistan, leads to lower admission and achievement in academic institutes and also influences job opportunities (Taran, 2011). Overall, the Hazara Shias are known to be a marginalized migrant community with high risk of violence and mental health problems, and low quality of life and living standards (Ali, 2021).

Aim of study

The Hazara Shias of Pakistan are a neglected and marginalized population, with very little academic scholarship to guide policy mobilization for their protection and wellbeing. In lieu of this gap and the literature that does exist, the aim of this study is to try and understand factors that influence the mental health and life satisfaction of the Pakistani Hazara Shias residing in Quetta. The specific research questions include:

-

(1)

Which specific socio-demographic characteristics of participants (age; gender; education; marital status; household income; occupation; number of family living in house; and head of household) are associated with PTSD;

-

(2)

What are the higher risks of participants facing mental health disorders with respect to low community support; and (3) What is the relationship between life satisfaction and independent variables of satisfaction with household stability; job satisfaction; financial security; and community support.

Methods

Ethics

We received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of Forman Christian College University to conduct a mixed methods study on the lived experiences and health and social challenges facing Hazara Shia migrants in Pakistan. Participants were provided information about study objectives and informed consent was taken before the start of the study. They were also informed that they could withdraw from the study at any point. No incentives or gifts were provided for participation. Those who self-identified with need for counseling services were offered free services.

Research design

Cross-sectional data has been collected with both closed-ended questions from internationally standardized scales. Three open-ended questions were also added to support respondents to share information about challenges that could not be captured in closed-ended items.

Sample

Both women and men above the age of 18 years were sampled through convenience sampling, which has been commonly used to engage hard-to-reach and vulnerable populations who are fearful for their safety. Seeking participants from community welfare and cultural centers was thus considered a safe zone which would yield a better response. The inclusion criteria were Hazara Shia migrants living in Quetta and who were above 18 years of age.

Tools

The questionnaire was translated by the third author through the forward and backward method (Supplementary File 1). The reliability results are presented in Table 1. Three internationally standardized scales were used to develop the questionnaire for this study. PTSD was assessed using the 24-item PTSD Scale-Self Report for DSM-5 (PSS-SR5) (PTSD Assessment Instruments, 2022). The PSS-SR5 uses a 4 point Likert scale, including responses of: ‘Once a week or less/a little’; ‘2 to 3 times a week/somewhat’; ‘4 to 5 times a week/very much’; and ‘6 or more times a week/severe’). Items include questions such as: “Trying to avoid thoughts or feelings related to the trauma” and “Having difficulty experiencing positive feelings”. A higher score indicates the likelihood of PTSD in respondent. The reliability of the scale for the current study was acceptable (Cronbach's alpha = 0.948)

Table 1.

Reliability and Scale analysis.

| Domain | α | Mean/SD | K |

|---|---|---|---|

| Household Stability (HS) | 0.836 | 29.40 (7.16) | 11 |

| Job Satisfaction (JS) | 0.751 | 06.53 (1.89) | 03 |

| Financial Security (FS) | 0.905 | 01.37 (0.64) | 07 |

| Community Support (CS) | 0.906 | 14.44 (7.48) | 10 |

| Life Satisfaction (LS) | 0.816 | 31.81 (9.96) | 21 |

| PTSD | 0.948 | 25.23 (16.92) | 24 |

| Mental Health | 0.966 | 38.91 (24.98) | 34 |

Common mental health disorders in respondents were measured using the 34-item Instrument for Common Mental disorders (CMDQ) (Christensen et al., 2005). The CMDQ uses a 5-point Likert scale, including responses of: ‘Not at all’, ‘A little’, ‘Modertaely’, ‘Quite a bit’, and ‘Extremely’. Items include questions such as: “Numbness or tingling in parts of body?” and “Worries that there is something seriously wrong with your body?” A higher score indicates higher prevalence of mental health disorders in respondent. The reliability of the scale for the current study was acceptable (Cronbach's alpha = 0.966).

Five study domains- Household Satisfaction, Job Satisfaction, Financial Security, Community Support, and Life Satisfaction, were measured using the Building a New Life in Australia Wave 5 Principal Applicant Survey- Questions (Rioseco et al., 2017). This instrument has been used for migrant communities in Australia and includes 10-items to measure household satisfaction. The first six questions use a 5-point Likert scale (‘Very Satisfied’ to ‘Very Dissatisfied’) include questions such as: “How satisfied are you with the number of rooms in your current home”. The next four questions use a 5-point Likert scale (‘Strongly disagree to ‘Strongly agree’) and include questions such as: “The people in my neighbourhood are friendly”. The reliability of the scale for the current study was acceptable (Cronbach's alpha = 0.836).

There are 3-items measuring job satisfaction, including questions such as “How satisfied are you with your job” and “Have you found it hard getting a job for any of these reasons and using a 5-point Likert scale (‘Very Satisfied’ to ‘Very Dissatisfied’).

There are 7-items measuring financial security, prompting respondents to tick options that apply to them, with questions such as: “Could not pay gas, electricity or telephone bills on time” and “Were unable to (could not) send your child/children to school”. The reliability of the scale for the current study was acceptable (Cronbach's alpha = 0.751).

The community support indicator was measured using 10-items and a 5-point Likert scale of (‘None of the time’ to ‘All of the time’). A higher score indicates higher community support received by respondent. Questions to measure community support included: “Someone to turn to for suggestions about how to deal with a personal problem” and “Someone to prepare your meals if you were unable to do it yourself”. The reliability of the scale for the current study was acceptable (Cronbach's alpha = 0.906).

The life satisfaction domain was measured using 22-items and a 5-point Likert scale depending on the type of question. Some questions had to be reverse coded to align all items so that a higher score indicated higher life satisfaction. Questions to measure life satisfaction included: “I am optimistic about my future in Pakistan” and “I am certain I can accomplish my goals”. The reliability of the scale for the current study was acceptable (Cronbach's alpha = 0.816).

Data collection

We recruited our participants from Quetta from October 2021 to January 2022. Four research assistants collected the data at the following community welfare and cultural centers: (i) Tanzeem e Nasl Nau; (ii) Wahdat Organization; and (iii) NIMSO Organization. We considered it inappropriate to approach participants at their residential homes, as they are a targeted community, who would fear independent researchers visiting their homes. Data was collected through the researcher-assisted method. This was for the convenience of participants, especially illiterate or semi-literate participants.

The research assistants belonged to the Hazara Shia community and this helped in the response and willingness to participate in the study. The research assistants were Undergraduate scholars with experience of research and were trained for the research objectives and assisted survey data collection technique over a one week period. There were two males and two females data collectors, in order to sample both genders from a conservative climate. The research assistants also conducted a brief pilot test of the survey with 5 respondents. Based on the pilot, we found that participants understood all the questions and there were no problems with the translation. Research assistants had the survey on their phone, as a Google survey, and read the questions out to participants or read it with them and then helped them fill the responses.

Finally, a total of 251 complete responses comprised the final sample. Data collectors reported that the low temperature in Quetta and the absence of heating at the community centers, during the months of data collection, was also a problem for willingness to participate in the survey. Women were not eager to respond, even to female data collectors, as they mentioned having to return to home and children. Some participants refused to participate as they believed that this study was a ruse to gain their identification and target them in some way. Some also commented that they only participate in surveys that have a cover letter from international organizations or charities of repute.

Data analysis

The data from the Google Survey Excel form was transferred to SPSS 25.0 for analysis. Descriptive statistics including frequencies and percentages were used to report the socio-demograohic characteristics of respondents and the descriptive data for PTSD, common mental disorders, and community support. The seven study domains were compounded and reliability analysis was conducted. Independent sample t-tests were used to predict the socio-demographics associated with higher PTSD. Next bivariate regression was used to report higher odds of mental health disorders in relation to low community support. Confidence intervals for bivariate odds ratio were reported. Dummy variables were created, with ‘0′ = ‘significant mental health disorders’ and ‘1′ = ‘insignificant mental health disorders’. Community support was recoded with a dummy variable of ‘0′ = ‘insignificant community support’ and ‘1′ = ‘significant community support’. For adjusted odds ratio (OR), age and income was controlled. We used the AMOS module in SPSS to apply structural equation modeling to examine the relationship between the dependent variable (life satisfaction) and other study variables, considered independent variables (Household Stability; Job Satisfaction; Financial Security; and Community Support). P‐values were assigned at 0.05 for this study. For the qualitative responses we conducted a thematic content analysis. We grouped and coded all similar statements to identify the main challenges facing the respondents.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

Table 2 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of study participants. Majority are male (61.8%) and between the ages of 18–37 years (67.7%). Almost half (44.4%) are either illiterate or have studied till primary (up to class 5) or secondary (up to class 10). Most participants (87.2%) have very low monthly household income of less than USD 425.65. A significant number of respondents are unemployed (29.1%), currently enrolled in a graduate program (31.5%) or employed in work such as teaching, business or as a private employee (39.4%). A near majority live in houses with family members above 5 people (77.7%) and most households are headed by men 73.7%. Participant frequency reports for common mental disorders and life satisfaction are summarized in Supplementary File 2. From the 21 questions asked about life satisfaction majority participants, between 67.7%−98.0%, reported unfavorable life satisfaction Table II. Significant number of participants, between 34.1%- 76.5%, reported experiencing common mental disorders.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants (N = 251).

| Variable | f | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 155 | 61.8 |

| Female | 96 | 38.2 |

| Age | ||

| 18–27 | 122 | 48.6 |

| 28–37 | 48 | 19.1 |

| 38–47 | 48 | 19.1 |

| 48 and above | 33 | 13.1 |

| Education | ||

| None | 18 | 07.2 |

| FSc./ Matric | 82 | 32.7 |

| Undergraduate | 151 | 60.2 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single/ Widowed | 154 | 61.4 |

| Currently Married | 97 | 38.6 |

| Monthly HH Income | ||

| PKR 12,000–24,999 (USD 68.10–141.88) | 52 | 20.7 |

| PKR 25,000–49,999 (USD 141.89–283.76) | 95 | 37.8 |

| PKR 50,000–74,999 (USD 283.77–425.65) | 72 | 28.7 |

| PKR 75,000–100,000 (USD 425.65–567.54) | 32 | 12.7 |

| Current Occupation | ||

| Unemployed | 73 | 29.1 |

| Enrolled as UG/PG student | 79 | 31.5 |

| Employed (teaching, business, private employee) | 99 | 39.4 |

| Number of family members living in house | ||

| 2–4 | 56 | 22.3 |

| 5–7 | 147 | 58.6 |

| 8 to 30 | 48 | 19.1 |

| Head of HH | ||

| Father-in-law/ Brother/ Uncle/ Grandfather | 136 | 54.2 |

| Husband | 49 | 19.5 |

| Self | 34 | 13.5 |

| Mother | 32 | 12.7 |

Mean analysis to predict higher PTSD

Table 3 presents mean comparisons of participant socio-demographics in relation to higher PTSD scores. Significant association has been found between higher mean scores of PTSD and socio-demographic characteristics of (i) women participants (M = 28.77 for females versus M = 22.03 for males), and (ii) Unemployed participants (M = 27.52 for unemployed versus M = 22.33 for employed).

Table 3.

Independent sample t-test between participant socio-demographic variables and PTSD (N = 251).

| Variable | N | Mean | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Younger than 37 years | 170 | 25.80 | 0.235 |

| Above 38 years | 81 | 22.58 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 155 | 22.03 | 0.009 |

| Female | 96 | 28.77 | |

| Education | |||

| None to FSc/ Matric | 100 | 20.38 | 0.400 |

| Undergraduate | 151 | 23.53 | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Single/ Widowed | 154 | 24.44 | 0.357 |

| Currently Married | 97 | 26.47 | |

| Monthly HH Income | |||

| 50,000 or less | 147 | 25.92 | 0.629 |

| 100,000 or less | 104 | 24.00 | |

| Current Occupation | |||

| Unemployed | 73 | 27.52 | 0.041 |

| Employed (teaching, business, private employee) | 99 | 22.33 | |

| Number of family members living in house | |||

| 4 or less | 56 | 23.92 | 0.960 |

| 5 to 30 | 195 | 23.77 | |

| Head of HH | |||

| Male family member or self | 219 | 24.61 | 0.306 |

| Mother | 32 | 28.06 |

Descriptive statistics for common mental health disorders

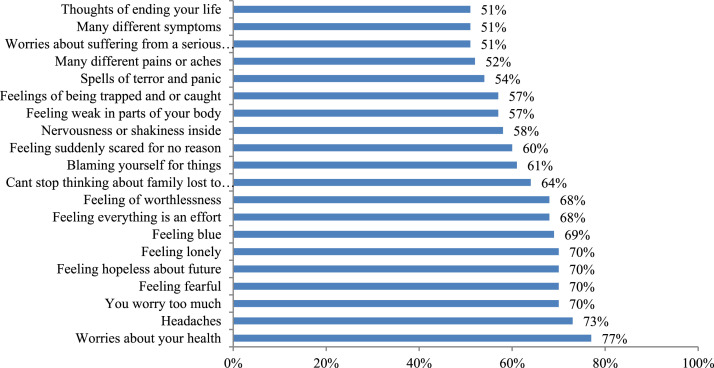

Fig. 1 presents a summary of the common mental health disorders reported by participants above the frequency of 51%. Most participants worry too much (70%), have worries about health generally (77%), and worry that they might suffer from a serious illness (51%). The majority experience headaches (73%), different aches and pains (52%), feel weak in parts of body (57%) and experience different symptoms (51%). Majority participants have feelings of fearfulness (70%), hopelessness for future (70%), loneliness (70%), blue moods (69%), that everything is an effort (68%), and worthlessness (68%). Majority is also unable to stop thinking about family lost to killing (64%). Significant number blames themselves for things (61%), feel suddenly scared for no reason (60%) and experience nervousness and shakiness inside (58%). Many also have feelings of being trapped (57%) and experience spells of panic (54%). More than half (51%) have thoughts about ending their lives.

Fig. 1.

Selective data for mental health challenges facing participants (N==251).

Bivariate regressions results for higher odds of mental health disorders in relation to low community support

Table 4 presents bivariate regression results for higher odds of mental health disorders in relation to low community support. Participants who had low support from community for (i) dealing with a personal problem 3.96 (1.37–0.6.73), (ii) having someone to listen to them when they need to talk- 3.68 (1.37–0.5.92), and (iii) sharing private worries and fears 2.58 (1.00–0.6.61) had high odds of mental health disorders. Similarly, participants who had low support from (i) national or ethnic community 2.34 (1.16–0.4.73), (ii) other community groups 1.84 (1.03–0.3.28), and (iii) from religious community 1.84 (0.99–0.3.46) had higher odds of mental health disorders.

Table 4.

Bivariate odds ratio for higher risk of mental health disorders in relation to community support variables (N = 251).

| OR | P vale | AOR | P vale | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low support from national or ethnic community | 2.32 (1.16–0.4.67) | 0.017 | 2.34 (1.16–0.4.73) | 0.017 |

| Low support from religious community | 1.84 (0.99–0.3.44) | 0.050 | 1.84 (0.99–0.3.46) | 0.050 |

| Low support from other community groups | 1.83 (1.02–0.3.26) | 0.040 | 1.84 (1.03–0.3.28) | 0.040 |

| Low support from for listening when you need to talk | 3.65 (1.36–0.5.83) | 0.010 | 3.68 (1.37–0.5.92) | 0.010 |

| Low support for talk to about yourself or your problems | 2.55 (0.89–0.5.30) | 0.081 | 2.59 (0.90–0.5.74) | 0.078 |

| Low support for sharing private worries and fears | 2.55 (0.99–0.6.56) | 0.050 | 2.58 (1.00–0.6.61) | 0.050 |

| Low support for suggestions about how to deal with a personal problem | 3.85 (1.34–0.6.99) | 0.012 | 3.96 (1.37–0.6.73) | 0.011 |

| Low support for assistance in visiting doctor if you needed it | 1.32 (0.59–0.2.95) | 0.489 | 1.34 (0.59–0.3.04) | 0.478 |

| Low support for preparing meals if you were unable to do it | 1.32 (0.59–0.2.95) | 0.489 | 1.34 (0.59–0.3.04) | 0.478 |

| Low support for helping with daily chores if you were sick | 1.33 (0.63–2.83) | 0.446 | 1.36 (0.63–2.92) | 0.427 |

Correlation analysis

Table 5 presents Pearson correlation results between study variables. Life satisfaction is positively correlated with household stability (r = 0.319, p < 0.01), job satisfaction (r = 0.17666, p < 0.01), and community support (r = 0.213, p < 0.01). However, life satisfaction is negatively correlated with financial security (r = - 0.870, p = n/s). Housing stability is positively correlated with job satisfaction (r = 0.231, p < 0.01), financial security (r = 0.148, p < 0.05) and community support (r = 0.323, p < 0.01). Job satisfaction is positively correlated with financial security (r = 0.160, p = n/s), but negatively correlated with community support (r = - 0.055, p = n/s). Financial security is negatively correlated with community support (r = - 0.800, p = n/s).

Table 5.

Correlation analysis between variables.

| HS | JI | FS | CS | LS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household Stability (HS) | 1 | ||||

| Job Satisfaction (JS) | 0.231** | 1 | |||

| Financial Security (FS) | 0.148* | 0.160 | 1 | ||

| Community Support (CS) | 0.323** | −0.055 | −0.800 | 1 | |

| Life Satisfaction (LS) | 0.319** | 0.176** | −0.870 | 0.213** | 1 |

Structural equation modeling

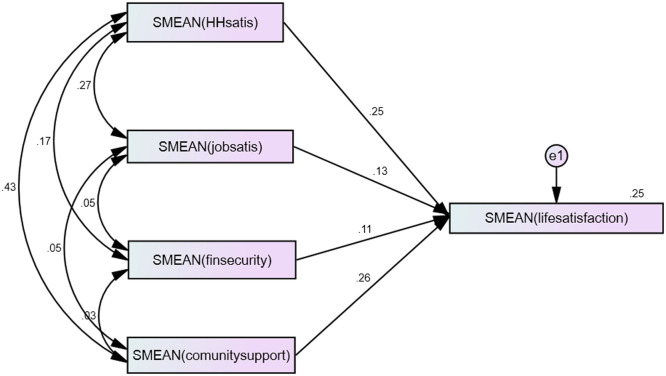

Path analysis (Fig. 2) reveals significant results for all four observed study variables (Table 6). Household satisfaction contributes to greater life satisfaction (β = 0.25, R2 = 0.25, p < 0.001) and community satisfaction also contributes to greater life satisfaction (β = 0.26, R2 = 0.25, p < 0.001). Financial security (β = 0.11, R2 = 0.25, p < 0.05) and job satisfaction (β = 0.13, R2 = 0.25, p < 0.05) also significantly contributes to greater life satisfaction. With regard to the relationship between the independent variables of the study, household satisfaction and community support positively covaried with each other (β = 0.43, p < 0.001), as did job satisfaction and household satisfaction (β = 0.27, p < 0.001). Similarly, financial security and household satisfaction covaried with each other (β = 0.17, p < 0.05) (Table 7).

Fig. 2.

Structural equation model showing standardized estimates of path analysis.

Table 6.

Path coefficients of Life Satisfaction.

| β | S.E. | C.R. | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household Satisfaction | → | Life Satisfaction | .248 | .077 | 3.861 | *** |

| Financial Security | → | Life Satisfaction | .114 | .952 | 2.043 | .041 |

| Job Satisfaction | → | Life Satisfaction | .127 | .272 | 2.231 | .026 |

| Community Support | → | Life Satisfaction | .260 | .065 | 4.251 | *** |

| R2 | .250 | *** | ||||

Table 7.

Covariances among observed variables.

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HHsatis_1 | <–> | comunitysupport_1 | 24.623 | 3.925 | 6.274 | *** |

| jobsat_1 | <–> | comunitysupport_1 | .733 | .904 | .811 | .417 |

| finsecurity_1 | <–> | HHsatis_1 | .609 | .227 | 2.683 | .007 |

| jobsat_1 | <–> | finsecurity_1 | .042 | .056 | .747 | .455 |

| jobsat_1 | <–> | HHsatis_1 | 3.379 | .828 | 4.081 | *** |

| finsecurity_1 | <–> | comunitysupport_1 | .109 | .253 | .431 | .667 |

Qualitative data categorizing the challenges facing the respondents

A thematic analysis of the qualitative answers of participants revealed the following eleven challenges which prevented life satisfaction:

Fears of assault and discrimination

-

1

Fear of physical assault and homicide (n = 178; 70.9%)- Many participants feared assault or homicide due to the regular and normalized attacks against the Hazara Shia community of Pakistan, specifically in Quetta.

-

2

Feel discriminated against in Pakistan and do not belong (n = 44; 17.5%)- Some participants believed they faced both individual-level and institutional-level discrimination, which prevented them from integrating and progressing in Pakistan.

Employment and education problems

-

1

Low pay and job not according to merit (n = 99; 39.4%)- Many employed participants believed they were not getting paid according to what they deserved and that their job profile was not according to their degree and merit.

-

2

English is not good enough and language is a barrier for progress and both educational and employment opportunities (n = 88; 35.1%)- A significant number of participants believed that not being well-verse in English or having a family and educational background which provided them with fluency in English was a barrier to their progress for professional advancement.

-

3

Choice of university and workplace is too far (n = 52; 20.7%)- Some participants complained of distant institutes for study and work, and not having adequate public transport facilities or being able to shift to nearer accommodation.

Financial and food security issues

-

1

Could not pay gas, electricity or telephone bills on time in the last few months (n = 164; 65.3%)- Majority participants complained that they could not pay basic utility bills on time due to lack of finances and nation-wide increments in utility bills.

-

2

Have to regularly pawn or sell things to survive (n = 88; 35.1%)- Many participants shared that they had to regularly sell things in order to survive and manage basic household expenses.

-

3

Went without meals in the last few months (n = 70; 27.9%)- A significant number of people stated that they had gone without meals or had to skip meals in the last few months due to lack of finances.

-

4

Need help from welfare or community organization in order to survive (n = 50; 19.9%)- Some participants agreed that without the help of welfare and community charity organizations they would not have been able to survive in the last few months.

-

5

Unable to send children to school due to expense (n = 33; 13.1%)- Some participants admitted that they were not sending their children to school due to the high expense and inability to pay for school fees, even the extra expenses required for public schooling, such as money for transport, uniform, food, books and stationary.

Discussion

Majority Hazara Shia participants of this study are impoverished, and are either illiterate or semi-literate. The majority also indicate low life satisfaction. This study confirms reports about the extreme deprivation, poverty and low literacy of the Hazara Shia community of Quetta (Ahmad Wani, 2019). The major finding, through path analysis, is that life satisfaction of Hazara Shias is associated with household and financial stability, and job satisfaction and community support. The independent variables also show positive covariance (household satisfaction, community support, job satisfaction, and financial security). Supporting migrants for housing, employment, income generation, and community inclusion is a human rights issue (Eschbach et al., 2001), which Hazara Shias of Pakistan have been deprived of since their relocation many decades ago. Global scholarship on migrant communities confirms that they are less likely to get formal sector jobs, adequate pay or satisfactory housing (UK Home Office Report, 2014). Unless migrants are supported with better laws to protect their social integration, financial security, and life satisfaction, development and stability within a region or nation is not possible (Phillimore, 2006).

Our study shows that higher PTSD scores are associated with women and unemployed people. Other research confirms that women migrants face greater stress, possibly due to greater isolation and less social connectedness (Anjara et al., 2017). With the Hazara Shia migrants, specifically, PTSD may be exacerbated in women and the unemployed due to the genocide they face and the loss of family members who were male guardians and financial sponsors. Furthermore, women migrants from conservative and unique ethnic backgrounds face their own complex challenges related to inability to culturally integrate leading to greater stress after relocation (Kavian et al., 2020). As has been done in other countries, there is critical need for supporting Hazara Shia women migrants with interventions for health services (Villadsen et al., 2016) and improved social support (Dominguez-Fuentes and Hombrados-Mendieta, 2012).

Scholarship also confirms that unemployed migrant workers face greater stress and depression, especially if the duration of their unemployment is longer and the type of job opportunities are from the informal sector (Chen et al., 2012). Since migrant populations, and women specifically, suffer from higher PTSD, scholars recommend regular screening in order to identify the extent of the problem and plan policies accordingly and on individual case basis (Schweitzer et al., 2018). The utilization of community social workers to support individual families within neighborhoods and the community, in partnership with primary level health services, would also be beneficial (Fortuna et al., 2008).

Our study also shows that the Hazara Shias suffer from high incidence of common mental health disorders as well. Majority experienced worries, blue moods, fears, and hopelessness. Many also felt trapped and had thoughts about ending their lives. There were also reports of physical symptoms such as headaches, weakness, aches and pains. This stress and anxiety are the result of various factors which include; experiencing the death of near and dear ones, living through unending war, stressed transit experiences, unending grief and loneliness, and cultural shock (Alemi, 2014; Hamrah, 2020). Research about migrant Hazara Shias from Australia also confirms that they suffer from vitamin and mineral deficiencies (Benson J, 2013), complex mental health (Ahmad F., 2020) and physical health (Finney Lamb C, 2009) challenges, due to historic malnutrition and negligence. Women, children, and elderly may face greater mental health risks due to remaining indoors and receiving less health attention (Sanati Pour M, 2014). It is also not uncommon for migrant refugees to suffer from suicide ideation, and even have incidence of suicides, especially when they experience low community support and absence of community structures to help them deal with conflict (Ao et al., 2016). There is immediate need to collect data to identify suicide rates in the Hazara Shia community through collaboration of state, health sector, and local community bodies.

Regression results revealed that participants who had low community support faced higher risk of mental disorders. Specifically, people with low support from national and ethnic community, religious community, and other community groups faced higher risk. Several studies confirm that migrant populations, especially those with experiences of conflict and violence, are highly dependent on community support in order to develop resilience and coping strategies for survival, progress and even advocacy (Siriwardhana et al., 2014). The benefits of delivering community support initiatives for migrants through their own ethnic and religious community is that the support generated is culturally appropriate and assists in dealing with exile-related stressors that are unique to the group (Tribe, R., 2002). In the Hazara Shias case, support from their own ethnic and religious community would help in making sense of the violence against them, shared understanding in coping with loss of loved ones, and encouraging long-term support for survival and advocacy.

The qualitative findings from our study reveal three areas of challenges that Hazara Shias identify as barriers to their life satisfaction. Firstly, as a non-combative targeted minority they feel immense fear of facing physical assault and homicide or then discrimination at the hands of state and society. Both academic scholarship and news reports confirm that the critical and urgent need is for Hazara Shias to be provided protection against the violence against them by perpetrators who are not being penalized by state to date (Ahmad Wani, 2019). Secondly, they feel they are underpaid and underutilized compared to their merit and that distance and inadequate English language skills both contribute to barriers in getting good academic or employment opportunities.

Finally, the Hazara Shias describe suffering from extreme poverty and food insecurity with complaints about inability to pay utility bills, going without eating meals, and inability to send children to school. In order to survive, many have to regularly pawn or sell things, and need support from welfare or charity organizations. Unless a diverse combination of effective interventions to support the economic and financial integration of the Hazara Shias is not delivered in Pakistan, there is risk that the violence and exclusion against the Hazaras contributes to sustained violence against them or ‘genocide by attrition’. This is because victims of ethnic cleansing and genocide are more vulnerable when they are neglected and marginalized by state and society, as they become voiceless and stateless groups who cannot advocate to stop the violence and injustice against them (Card, 2003; Caso, 2011).

There are some limitations to our study. We were not able to achieve random sampling or a bigger sample, due to low response. The data was collected at Hazara Shia community centers, and results may differ or perhaps be worse for those who do not visit their community centers and are restricted to their homes. We also limited our sample to Hazara Shias in Quetta, and it may be possible that other Hazara Shias in Pakistan face similar or different challenges that need to be investigated. However, the strength of this study is that it helps to identify factors that are contributing to low life satisfaction and mental health problems in the Hazara Shia community and also helps to highlight which areas need to be improved upon to support them. The findings of this study are important not just for mobilizing protective policy and security for the Hazara Shias who are in dire need of both, but also contributes to the literature for realties of migrant populations living in developing nations who face victimization due to religious and ethnic belonging.

Conclusion

This is the first empirical study on the life satisfaction and mental health of the Hazara Shia community in the city where they are found in large majority after migration from Afghanistan. The findings contribute to empirical evidence that should inform and mobilize the state, society, ethnic and religious communities, and international stakeholders about the extreme victimization and neglect facing the community. Overall, participants were found to have low life satisfaction and face considerable mental health challenges. From both a human rights and nation building perspective, there is need to support the Hazara Shia community with protection and security, and simultaneously deliver interventions to improve their life satisfaction and mental health. This study is able to identify the interventions needed to improve their wellbeing, including improvement in housing stability, financial security, job satisfaction, and community support. Future research must also look closely into specific needs for more vulnerable groups, the women and unemployed, within the Hazara Shia community.

Funding

This study has not received any funding

Author contributions

SRJ designed the study and was responsible for the data collection, data analysis and drafting of the manuscript. SKB assisted in data collection and QK in data analysis. SMHN assisted in tool development and reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final version.

Declaration of Competing Interest

We have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our data collectors Shehzad Ali, Muhammad Hadi, Maria Batool, and Anam Zara. We also acknowledge support from the following for arranging permission at community centers for collecting data and helping to coordinate timings and approach participants for consent: Abdul Baseer, Alamdar Hussain, Barkat Ali, Ghulam Raza, Muhammad Tahir, Murtaza Noyan, Sabeem Imtiaz, Mujeeb ur Rehman, Sulyman Shah, and Asmat Kakkar. Finally, we would like to thank student research assistants Sheza Saeed and Kundan Rana for assistance in coordinating with data collectors, sometimes late at night, and later coding and entry of data into SPSS.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jmh.2023.100166.

Contributor Information

Sara Rizvi Jafree, Email: sarajafree@fccollege.edu.pk.

Syeda Khadija Burhan, Email: khadijaburhan@fccollege.edu.pk.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Adams B., Kine P., Ross J., Saunders J. Human Rights Watch; 2014. We Are the Walking Dead’: Killings of Shia Hazaras in Balochistan, Pakistan. [Google Scholar]

- Adler S. Maslow's need hierarchy and the adjustment of immigrants. J. Int. Migration Rev. 1977;11(4):444–451. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad Wani S. Political indifference and state complicity: the Travails of Hazaras in Balochistan. J. Strat. Anal. 2019;43(4):328–334. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad F. Posttraumatic stress disorder, social support and coping among Afghan refugees in Canada. Community Ment. Health J. 2020:597–605. doi: 10.1007/s10597-019-00518-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemi Q.J. Psychological distress in Afghan refugees: a mixed-method systematic review. J. Immigrant Minority Health. 2014:1247–1261. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9861-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M., Briskman L., Fiske L. Asylum seekers and refugees in Indonesia: problems and potentials. J. Cosmopolitan Civ. Soc. 2016;8(2):22–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ali S. The specter of hate and intolerance: sectarian-Jihadi nexus and the persecution of Hazara Shia community in Pakistan. J. Contemporary South Asia. 2021;29(2):198–211. [Google Scholar]

- Anjara S.G., Nellums L.B., Bonetto C., Van Bortel T. Stress, health and quality of life of female migrant domestic workers in Singapore: a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2017;17(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12905-017-0442-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ao T., Shetty S., Sivilli T., Blanton C., Ellis H., Geltman P.L., Cardozo B.L. Suicidal ideation and mental health of Bhutanese refugees in the United States. J. Immigrant Minority Health. 2016;18(4):828–835. doi: 10.1007/s10903-015-0325-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson J. Low vitamin B12 levels among newly-arrived refugees from Bhutan, Iran and Afghanistan: a Multicentre Australian Study. PLoS ONE. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahmbhatt K.A. Refugee Council and University of Birmingham; Birmingham: 2007. Refugees’ Experiences of Integration: Policy Related Findings on Employment, ESOL and Vocational Training. [Google Scholar]

- Brown T. After the boats stopped: refugees managing a life of protracted limbo in Indonesia. J. Antropologi Indonesia. 2017:34–50. [Google Scholar]

- Card C. Genocide and social death. Hypatia. 2003;18(1):63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Caso M. iUniverse; 2011. Invisible and Voiceless: The Struggle of Mexican Americans For Recognition, Justice, and Equality. [Google Scholar]

- Changezi S.H., Biseth H. Education of Hazara Girls in a Diaspora: education as empowerment and an agent of change. J. Res. Comparat. Int. Educ. 2011;6(1):79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Changezi S.B. Education of Hazara Girls in a Dispora: education as empowerment and an agent of change. Res. Comparat. Int. Educ. 2011:79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Li W., He J., Wu L., Yan Z., Tang W. Mental health, duration of unemployment, and coping strategy: a cross-sectional study of unemployed migrant workers in eastern China during the economic crisis. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen K.S., Fink P., Toft T., Frostholm L., Ørnbøl E., Olesen F. A brief case-finding questionnaire for common mental disorders: the CMDQ. Fam. Pract. 2005;22(4):448–457. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vroome T., Hooghe M. Life satisfaction among ethnic minorities in the Netherlands: immigration experience or adverse living conditions? J. J. Happiness Stud. 2014;15(6):1389–1406. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Report (2022). The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) Information Report Pakistan, Prepared for Government of Australia, Retrieved from https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/country-information-report-pakistan.pdf.

- Dominguez-Fuentes J.M., Hombrados-Mendieta M.I. Social support and happiness in immigrant women in Spain. Psychol. Rep. 2012;110(3):977–990. doi: 10.2466/17.02.20.21.PR0.110.3.977-990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschbach K., Hagan J., Rodríguez N. lasa Forum. Vol. 32. 2001. Migrant deaths at the US-Mexico border: research findings and ethical and human rights themes; pp. 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- European Asylum Support Office (EASO). (2015). EASO Country of Origin Information Report. Pakistan Country Overview. Retrieved from http://www.refworld.org/docid/55e061f24.html.

- Finney Lamb C. Refugees and oral health: lessons learned from stories of Hazara refugees. Aust. Health Rev. 2009 doi: 10.1071/ah090618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortuna L.R., Porche M.V., Alegria M. Political violence, psychosocial trauma, and the context of mental health services use among immigrant Latinos in the United States. Ethn. Health. 2008;13(5):435–463. doi: 10.1080/13557850701837286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall H., Hekmat L. Talking to water: memory, gender and environment for Hazara refugees in Australia. J. Int. Rev. Environ. History. 2021;7(1):83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Hamrah M.H. The prevalence and correlates of symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among resettled Afghan refugees in a regional area of Australia. J. Mental Health. 2020 doi: 10.1080/09638237.2020.1739247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Watch. (2014). “We are the Walking Dead” Killings of Shia Hazaras in Balochistan, Pakistan, https://www.hrw.org/report/2014/06/29/we-are-walking-dead/killings-shia-hazara-balochistan-pakistan.

- Kavian F., Mehta K., Willis E., Mwanri L., Ward P., Booth S. Migration, stress and the challenges of accessing food: an exploratory study of the experience of recent Afghan women refugees in Adelaide, Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(4):1379. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17041379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S., Ul Amin N. Minority ethnic, race and sect relations in Pakistan: hazara Residing in Quetta. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. (Pakistan) 2019;27(2) [Google Scholar]

- Koser, K. (2013). Migration and Displacement Impacts of Afghan Transitions in 2014: implications for Australia. Irregular Migration Research Program Occasional Paper Series, no. 03/2013. Australian Dept. of Immigration & Citizenship.

- Lee A. Post-traumatic stress disorder and terrorism. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2002:633–637. [Google Scholar]

- Majeed G. Issues of Shia Hazara Community of Quetta, Balochistan: an Overview. J. J. Polit. Stud. 2021;28(1):77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Mares P. Refuge without work: 'This is a poison, a poison for the life of a person'. Griffith Rev. 2014;(45):103–116. [Google Scholar]

- National Commission for Human Rights. (2018). Understanding the Agonies of Ethnic Hazaras. NCHR Report, Islamabad.

- Parkes A. Afghan-Hazara Migration and Relocation in a Globalised Australia. J. Religions. 2020;11(12):670. [Google Scholar]

- Phillimore J.a. Problem or Opportunity? Asylum seekers, refugees, employment and social exclusion in deprived Urban Areas. Urban Stud. 2006:1715–1736. [Google Scholar]

- PTSD Assessment Instruments 2022, Available from: https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/assessment/. [cited 23 Jun 2020].

- Radford D., Hetz H. Aussies? Afghans? Hazara refugees and migrants negotiating multiple identities and belonging in Australia. J. Soc. Identities. 2021;27(3):377–393. [Google Scholar]

- Rioseco P., De Maio J., Hoang C. The building a new life in Australia (BNLA) dataset: a longitudinal study of humanitarian migrants in Australia. Aust. Econ. Rev. 2017;50(3):356–362. [Google Scholar]

- Rose S.C., B. J. (2002). Psychological debriefing for preventing post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane database of systematic reviews. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ryan D., Dooley B., Benson C. Theoretical perspectives on post-migration adaptation and psychological wellbeing among refugees: towards a resource-based model. J. Refug. Stud. 2008;21(1):1–18. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fem047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanati Pour M. Prevalence of dyslipidaemia and micronutrient deficiencies among newly arrived Afghan refugees in rural Australia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer R.D., Vromans L., Brough M., Asic-Kobe M., Correa-Velez I., Murray K., Lenette C. Recently resettled refugee women-at-risk in Australia evidence high levels of psychiatric symptoms: individual, trauma and post-migration factors predict outcomes. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1143-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi M.U.A., Mukhtar M. Perceptions of Violence and Victimization among Hazara in Pakistan. J. Polit. Sci. 2015;33:1. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi F.H. Security Dynamics in Pakistani Balochistan: religious Activism and Ethnic Conflict in the War on Terror. J. Asian Affairs. 2012;39(3):157–175. [Google Scholar]

- Siriwardhana C., Ali S.S., Roberts B., Stewart R. A systematic review of resilience and mental health outcomes of conflict-driven adult forced migrants. Confl. Health. 2014;8(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultan S., Kanwer M., and Mirza J.A., (2020), The Multi-Layered Minority: exploring the Intersection of Gender, Class and Religious-Ethnic Affiliation in the Marginalisation of Hazara Women in Pakistan Religious Inequalities and Gender, Part of the CREID Intersection Series Retrieved 1.2.22: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/15870/The%20Multi-Layered%20Minority_v2.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Tan N.F. The status of asylum seekers and refugees in Indonesia. J. Int. J. Refugee Law. 2016;28(3):365–383. [Google Scholar]

- Taran P. Global Migration Policy Associates (GMPA); Geneva: Geneva: 2011. Crisis, Migration and Precarious Work: Impacts and Responses. Focus on European Union Member Countries. [Google Scholar]

- Tribe R. Mental health of refugees and asylum-seekers. Adv. Psychiatric Treat. 2002;8(4):240–247. [Google Scholar]

- UK Home Office Report . Stationary Office; London: 2014. Asylum Policy Instruction: Permission to Work.http://sheffieldvolunteercentre.org.uk/uploads/files/GOV_Permission_to_Work_Asy_v6_0_April_2014.pdf Retrieved 31.1.22. [Google Scholar]

- Villadsen S.F., Mortensen L.H., Andersen A.M.N. Care during pregnancy and childbirth for migrant women: how do we advance? Development of intervention studies–the case of the MAMAACT intervention in Denmark. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016;32:100–112. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarak M.S., Rasool G., Arshad Z., Batool M., Shah S., Naseer M., Haq S.W.R. Assessment of Psychological Status (PTSD and Depression) Among The Terrorism Affected Hazara Community in Quetta, Pakistan. Cambridge Med. J. 2020:1–8. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.