Abstract

Background. The occupational therapy profession needs to respond to the calls to action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) to engage in the process of reconciliation with Indigenous populations. Purpose. To inform development of a survey intended to determine the knowledge gaps of occupational therapists in relation to Indigenous health. Method. A Delphi process engaging 18 occupational therapists with membership in an Indigenous health network was used to prioritize and refine potential themes identified via literature review. Findings. Results of three consensus rounds and Dunn-Bonferroni post-hoc testing demonstrated three statistically distinct hierarchical tiers of 10 priority themes to inform survey development. Implications. The consensus prioritized themes from the literature to underpin further research on occupational therapists’ knowledge in relation to Indigenous health and can provide a learning scaffold for occupational therapists to support a continued response to the TRC calls to action.

Keywords: Consensus, Healthcare disparities, Mixed methods, Priority setting, Reconciliation

Résumé

Description. Les ergothérapeutes doivent répondre aux appels à l’action de la Commission de vérité et réconciliation (CVR) pour s’engager sur la voie de la réconciliation avec les Autochtones. But. Aider à l’élaboration d’un sondage visant à déterminer les lacunes dans les connaissances des ergothérapeutes en matière de santé des Autochtones. Méthodologie. Un processus Delphi avec 18 ergothérapeutes membres d’un réseau sur la santé des Autochtones a été utilisé pour hiérarchiser et affiner les thèmes potentiels recensés par l’entremise d’une revue de la littérature. Résultats. Les résultats de trois tours de consultation et du test post hoc de Dunn-Bonferroni démontrent trois niveaux hiérarchiques statistiquement distincts de 10 thèmes prioritaires pour l’élaboration du sondage. Conséquences. Des thèmes issus de la littérature ont été priorisés pour étayer de futures recherches sur les connaissances des ergothérapeutes en matière de santé des Autochtones et aider les ergothérapeutes à évoluer dans leurs apprentissages pour offrir une réponse continue aux appels à l’action de la CVR.

Mots clés: Consensus, disparités en santé, établissement des priorités, méthodes mixtes, réconciliation

Introduction

For over 150 years, the central goals of policies enacted by governments and other organizations in Canada were to eliminate Indigenous government, rights, and treaties, and through the process of assimilation, cause Indigenous Peoples to cease to exist as distinct peoples (Truth and Reconciliation Commission [TRC], 2015). Residential schools were a central component of this assimilation process and involved the removal of Indigenous children from their homes to residential schools, with the purpose of breaking connections to their culture and identity (TRC, 2015). In 2008, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) was established under the terms of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement between former residential school students, churches, Indigenous organizations, and the Government of Canada (TRC, 2015). The TRC published a final report summarizing the findings of the Commission in relation to the historic relationship between Indigenous Peoples and the Government of Canada, and included 94 calls to action related to education, child welfare, health, and justice (TRC, 2015).

Reconciliation within the Canadian context is a critical and continuous multifaceted process. In recent years, Canada has begun grappling with the historical and ongoing colonization of Indigenous Peoples to address harms through public awareness and reconciliation. There has been increased awareness and focus on the atrocities of residential schools (TRC, 2015), the findings of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG, 2019), and the rights of Indigenous Peoples and communities (e.g., implementation of a National Day for Truth and Reconciliation).

Working toward reconciliation is the responsibility of every Canadian, including occupational therapists. According to the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists (CAOT)'s “CAOT Position Statement: Occupational Therapy and Indigenous Peoples” (CAOT, 2018), occupational therapists are well positioned to support and advance reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples. This is because the profession promotes values such as collaboration and challenges the dominant biomedical model in healthcare (White & Beagan, 2020). At the same time, occupational therapists must acknowledge and address the ways that occupational therapy is situated and rooted in Western frameworks and ways of knowing (Hammell, 2019). Despite the perceived fit between the occupational therapy profession and advancing reconciliation, there is a need for the profession to respond to the calls to action outlined by the TRC and to engage in ongoing reconciliation (Restall et al., 2016).

To reconcile Indigenous ways of knowing and Western practice, there is a need for change within the profession—in curricula as well as policy and regulatory approaches—so that occupational therapists can collaborate with Indigenous Peoples to develop theories and models that will improve health and education outcomes (Phenix & Valavaara, 2016). Indigenous scholars in Canada have outlined the need to view occupational therapy programs as an environment in which to foster change (Phenix & Valavaara, 2016; Restall et al., 2016) and the need to work with occupational therapy associations to guide practice, curriculum development, and professional competencies (Restall et al., 2016).

While existing literature describes how occupational therapists engage with Indigenous Peoples in Canada, many articles focused on the TRC response are non-peer-reviewed editorial publications (e.g., Phenix & Valavaara, 2016; Restall et al., 2016). However, occupational therapists across Canada have demonstrated a commitment to responding to the TRC calls to actions. For example, occupational therapy leaders gathered in 2018 for an annual reflection day in part to “reflect on, and work toward, occupational therapy's responsibility to respond to the TRC calls to action” (Trentham et al., 2018, p. 30). Participants acknowledged that a) the occupational therapy profession is at the beginning of a long journey of reconciliation, and b) occupational therapists must collaborate with professional leadership organizations to align policies and processes to work towards reducing health inequities and to practice in a culturally safe manner (Trentham et al., 2018). As another example, the Occupational Therapy and Indigenous Health Network (OTIHN), a CAOT Practice Network comprised of Indigenous and settler ally occupational therapists and student occupational therapists, continues to focus on building capacity, lobbying for services, and generating a discourse on occupational therapy and Indigenous Peoples’ health in Canada (CAOT, 2016).

Occupational therapists have professional, moral, and ethical responsibilities to respond to the TRC's calls to action (Restall et al., 2016). If the profession does not respond, their silence will be complicit in upholding colonial structures and relationships in all sectors of society perpetuating the marginalization and oppression of Indigenous Peoples (Restall et al., 2016). Restall et al. (2016) call on occupational therapists within Canada to ask themselves: “What is my responsibility to address the current injustices and inequities experienced by Indigenous Peoples in Canada?”… [and] “How will I respond to the calls to action?” (p. 265). Responding to the TRC, individually and collectively, is an opportunity for occupational therapists to translate their principles, values, and professional accountability into practice. This further inspires occupational therapists to promote the occupational rights of individuals to freely engage in meaningful occupations, which supports the actualization of human rights (World Federation of Occupational Therapists, 2019).

It is crucial to address one's knowledge gaps about Indigenous health to uphold the principle of non-maleficence in occupational therapy practice (Jacek et al., 2019). The CAOT calls for transformation of occupational therapy practice “to be more culturally safe and to provide space for Indigenous worldviews, knowledge and self-determination” (CAOT, 2018, p. 1). However, occupational therapists must first be aware of their knowledge gaps in relation to Indigenous health and understand how the profession can do harm. True actionable work toward reconciliation can only be pursued if occupational therapists identify and address knowledge gaps.

The term Indigenous will be used throughout this paper to refer to First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples in Canada. The researchers acknowledge the limitations of collapsing diverse Indigenous Peoples and groups under the umbrella term of “Indigenous.” Despite an increase in use of the term “Indigenous” in Canada, it is also contested, as it does not acknowledge the unique languages, histories, knowledge, beliefs, and distinct rights of First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples.

Study Purpose and Rationale

Student occupational therapists at McMaster University initiated an evidence-based practice research project in 2017 using a Delphi process to develop a national needs survey to determine the knowledge gaps of occupational therapists in relation to Indigenous health. The prioritization of themes through the Delphi process was intended to systematically engage stakeholder input into weighting of survey questions and constructs. A Delphi method is a step-wise process of eliciting input from individual experts, compiling the input, and subsequently sharing back the compiled information to identify priorities (Hsu & Sandford, 2007). This consensus process is ideal for developing recommendations to address areas lacking robust evidence (Jünger et al., 2017). The purpose of this study was to use a Delphi method to determine priority constructs for the next phase of the project, that being to develop a survey that would be useful to determine the overall knowledge gaps for occupational therapists working with Indigenous Peoples in Canada. The intent of the survey is to understand the current knowledge of occupational therapists working with Indigenous Peoples in Canada that will inform an evidence-based strategy to address identified knowledge gaps and assist therapists to better engage in reconciliation. To accomplish this goal, the research team undertook a three-phase approach of conducting a literature review, seeking consensus from occupational therapists with membership in an Indigenous health network on key constructs that represent knowledge about Indigenous health, and then developing and implementing a national survey of occupational therapists. This article presents the findings from the first two phases of this project.

Method

A Delphi consensus process was conducted to identify and endorse priority themes for generating survey questions to surface the knowledge gaps of occupational therapists in Canada regarding Indigenous health. The study received approval from the local ethics board as phase one of the proposed survey development (Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board [HiREB] #4150). The research team is composed of white settler-descent occupational therapists and acknowledges that this positionality and privilege inherently biases the research process due to a lack of Indigenous representation and a lack of situated experience of systemic exclusion within the research team. The research team acknowledges that we are working to deconstruct our biases within and beyond our research process.

The research team coordinator (ML) continually seeks out and completes training related to Indigenous health and cultural safety and is an active member of the OTIHN. As this project lacks Indigenous authorship, connection to the national network was essential for the completion of the Delphi process. The academic mentor (TP) of the project recognizes her responsibility to redress systemic injustices using her power and social location as an educator. She continues to engage in ongoing learning about the impacts of colonization by seeking out Indigenous writers and voices, and strategically foregrounds Indigenous ways of knowing and sharing knowledge in her teaching and research.

Prior to beginning this project, the student research team (CJ, KF, ME, JM) each completed letters of interest regarding project participation reviewed by ML, the research team coordinator. The students outlined examples of experiences and skills from both personal and professional lives including previous health-related fieldwork experience, support of equity-deserving groups using a legal and policy lens, and through attendance at training and conferences related to Indigenous health and advocacy. The letters were reviewed by the research coordinator to confirm interest and determine project fit. Following confirmation of the research team, the students completed the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans Course on Research Ethics (TCPS 2: CORE) including the module on Research Involving the First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples of Canada.

As a group, the research team acknowledges that our ability to explicitly engage in a critical examination of positionality has grown throughout this process. The research team intentionally practiced reflexivity individually and collectively to attend to this bias throughout the project via in-depth discussions, regular sharing of resources and learning opportunities, and attendance at an Indigenous Cultural Competency Training Day for healthcare providers by the Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres. The authors continue to be committed to ongoing learning, purposeful professional development, and sharing of resources to support an individual and collective response to the calls to action outlined within the TRC.

Participants

At the time of the study, the expert group that served as the sampling frame for the Delphi process (OTIHN) included approximately 40 Indigenous and settler occupational therapists in Canada with an interest in providing leadership and support for occupational therapy research, education, and practice with and for Indigenous Peoples. Prior to starting the research project, the research coordinator connected with the OTIHN co-chairs to determine if the project was relevant to the network and a good fit for the members to participate in the Delphi process. Participation in the Delphi method was voluntary and anonymous; all group members were invited to participate. Participants were provided with information about the study purpose and objectives via an ethics approved email from a network co-chair and through the LimeSurvey platform (including a description of the Delphi process). Consent for participation was obtained through choosing to proceed with the survey. As this was a small and connected community, demographic information was not gathered to maintain confidentiality.

Data Collection

Literature. To develop themes for the Delphi consensus process, a systematic literature search was completed in February 2018 to map the occupational therapy literature focusing on Indigenous health in Canada. Five databases (CINAHL, OTSeeker, AMED, Social Sciences Abstracts, PsycInfo), Google Scholar and the CAOT Occupational Therapy Now (OT Now) practice magazine were searched for relevant articles. Hand searching through reference lists of included articles was used to ensure all relevant sources were found. Keywords and inclusion criteria are included in Supplemental File A. Title and abstract screening criteria included sources that were published in peer-reviewed journals and grey literature, written in English, and consisted of a Canadian context with both an Indigenous and an occupational therapy focus. The inclusion criteria were intentionally broad to capture a range of perspectives in the literature. Titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion independently by the four reviewers, and any uncertainties were addressed through discussion. Refworks software was used to eliminate duplicate sources. Sources in the full-text review included original research manuscripts, reviews, discussions, editorials/expert opinions, and presentations. Gray literature, defined as professional practice magazines and conference presentations, was intentionally included to allow for diversity in ideas not present in traditional journal articles. Sources were English language literature—a limitation of the researchers’ linguistic abilities. The researchers used a shared Google Sheet to organize inclusion criteria met by each article, a shared Google Doc as a code book, and another Google Doc that outlined the codes allocated to each included article. The researchers used the iterative thematic analysis process outlined in Braun and Clarke (2006) to generate themes.

Delphi Process. The Delphi process was conducted using LimeSurvey, an anonymous online platform hosted on a secure server at McMaster University. The LimeSurvey link was forwarded by the expert group co-chair to group members, with a one-week reminder. Each Delphi round survey was available for two weeks.

In round one of the Delphi method, respondents from the expert group reviewed and provided written feedback on the identified themes and sub-themes. In round two, respondents ranked each theme on a ten-point Likert scale to identify its priority for question generation in the national needs survey (1 ranked highest priority to 10 ranked as lowest priority). To minimize response bias, the themes were presented in a randomized order for each participant. In Delphi round three, respondents from the expert group reviewed the themes presented in order based on each theme's mean rank from round two of the exercise. Participants were asked if they agreed with the ranking of the themes, and if not, were asked to rank the themes reflecting their perceived priority.

Data Analysis

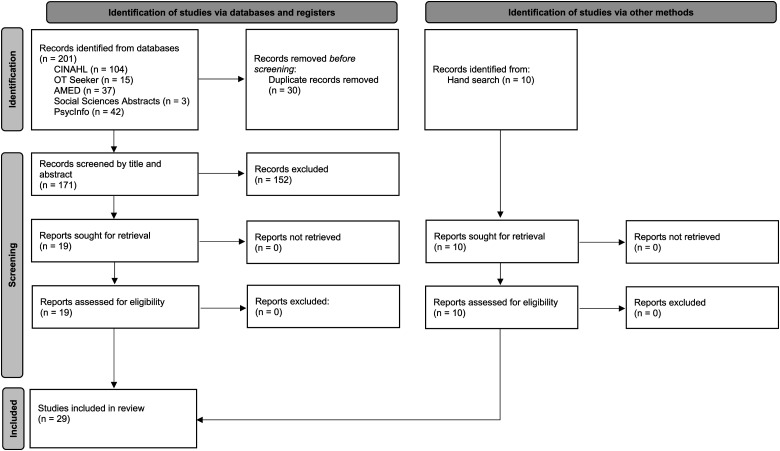

The iterative thematic analysis process outlined in Braun and Clarke (2006) was used to generate themes from the literature review. Braun and Clarke (2006) outline six phases of thematic analysis, with Phase One being “familiarizing yourself with the data.” Systematic searching identified 211 articles addressing occupational therapy with Indigenous Peoples. After removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts for eligibility, 29 articles were selected for full review (see Figure 1 and Supplemental File B).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram (Page et al., 2021).

The first selected article (Restall et al., 2016) was reviewed and coded by all team members to develop code constructs. This article was chosen as it explicitly matched all eligibility criteria and was a shorter article that could be more easily coded by the larger group as a first trial. Phase Two is “generating initial codes,” where the researchers developed a list of preliminary codes (single words or short phrases) matching text segments in the Restall et al. (2016) article. After the full review of the first article was completed, the research team met to discuss and aggregate these codes into broader concepts as a form of triangulation. Phase Three consists of “searching for themes,” where the remaining 28 papers were randomly divided into two equal groups and coded by paired independent reviewers by iteratively reviewing and adding to the list of codes. Phase Four is “reviewing themes,” where these codes were then refined into concepts or sub-themes using a thematic “map” process, as outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006). From the sub-themes, ongoing discussion and reflections were used to refine and organize sub-themes into 10 overarching themes. This was completed by grouping and collapsing the sub-themes under larger headings, which became the themes. This led to the final thematic structure used for the Delphi consensus exercise.

The data from the second and third rounds of the Delphi method was analyzed to determine if consensus was achieved. Definitions of consensus used in a Delphi method vary widely (Diamond et al., 2014). For the purpose of this study, consensus was defined through a pragmatic interpretation of the mean rankings for each theme and supported using Friedman test and Dunn-Bonferroni post hoc test (Hazard-Munro, 2001). A Dunn-Bonferroni post hoc test was completed following a statistically significant Friedman test. Statistically significant differences in the mean rankings of the top and bottom ranked tiers of themes would indicate that the Delphi method could be concluded, as consensus had been reached. The Dunn-Bonferroni post-hoc test was also used to identify priority “tiers” for use in survey development. A tier was defined as a discrete set of consecutively rated themes, which yielded statistically significant differences on a Dunn-Bonferroni post-hoc test when compared to another set of consecutively rated themes.

Findings

Theme Development

Phase Five of the thematic analysis process (Braun & Clarke, 2006) consists of “defining and naming themes,” where through ongoing analysis and discussion, the team identified 10 primary themes with 27 corresponding sub-themes from the literature review. The primary themes identified were: 1) impact of colonialism, 2) Indigenous relationships/partnerships, 3) power imbalances, 4) occupational therapy as a vessel that perpetuates the cultural genocide of colonialism, 5) advocacy/innovation, 6) inappropriate use/imposition of Western norms, 7) cultural safety, 8) respecting knowledge, 9) underlying assumptions of the profession, and 10) reflective/critical practice.

Delphi Round One

Eighteen members of the expert group participated in round one of the Delphi method. Most participants in the expert group voiced their agreement and support regarding the themes presented; one participant provided feedback that the list of themes was too long, while another participant suggested the addition of a theme: “OT models and theoretical approaches and how they don't fit an Indigenous world view” (participant 3). Participants suggested additional sub-themes and offered elaboration on existing sub-themes; after consolidation, there were 58 total sub-themes (see Supplemental File C). Multiple suggestions were made regarding language use and terminology to improve the clarity of the themes and sub-themes in relation to the survey and impact on survey respondents. For example, participant three from the expert group clarified the wording of an existing sub-theme by writing, “I wouldn’t say that traditional healing is a ‘viable option’; it is key to healing for many Indigenous people.” Feedback from all participants was consolidated through discussion among the four students with the use of an Excel spreadsheet to organize and integrate these comments, and wording of sub-themes was edited. The edited list of 10 themes was used to proceed with round two of the Delphi process.

Delphi Round Two

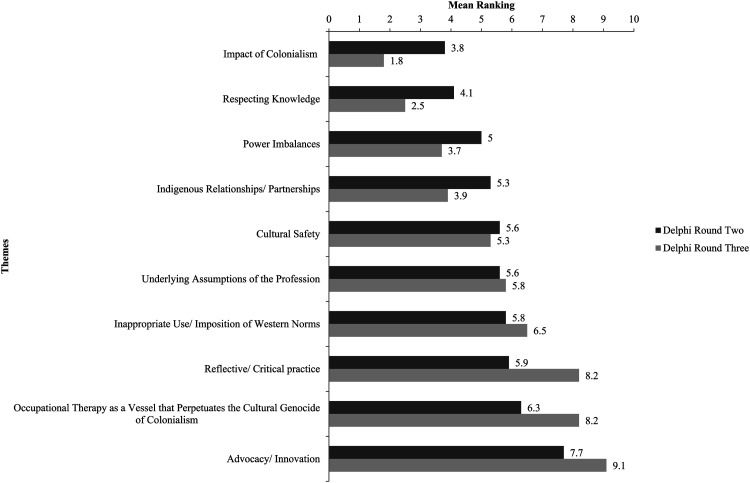

Twelve members of the expert group participated in round two of the consensus process; due to anonymity, it was not possible to determine if participants were consistent between rounds. Themes were ordered using the mean ranking for each theme, with 1 being highest priority to 10 being lowest priority (see Figure 2). While the themes could be rank ordered, there did not appear to be sufficient differences between each theme to conclude that the order was the result of consensus. Results from the Friedman test supported this pragmatic interpretation as there was no statistically significant difference between any of the mean rankings of the themes in round two of the Delphi (x2(9) = 14.055, p = .120). As a result, it was determined that consensus was not achieved, and a third round of the Delphi process was enacted.

Figure 2.

Mean rankings for each theme from the second and third rounds of the Delphi method. The highest priority themes are listed at the top of the figure and organized in descending priority.

Delphi Round Three

Ten members of the expert group participated in round three of the Delphi method. The themes were returned in the same order as seen in round two; however, the differences between mean rankings appeared to be more considerable (see Figure 2). Results from Friedman test support this pragmatic interpretation as there was a statistically significant difference between the mean rankings of the themes in round three of the Delphi method (x2(9) = 62.356, p < .001). The Dunn-Bonferroni post hoc test returned significant differences (p < .05) between the themes ranked at the top with those ranked at the bottom (see Table 1). As a result, it was determined that consensus was achieved, and the Delphi process could be concluded. Results of the Dunn-Bonferroni test demonstrated differences between themes 1–3 and themes 8–10, with themes 4–7 in the middle (see Table 1 and supplemental File D). This informed the development of three tiers for which survey questions could be developed in the next phase of the project (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Statistically Significant Pairwise Comparisons from the Dunn-Bonferroni Post-Hoc Test Following Round Three of the Delphi Method.

| Pairwise Comparisons | Adjusted Significance Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top Ranked Themes | Bottom Ranked Themes | |||

| Rank 1 | Impact of colonialism | Rank 7 | Inappropriate use/ imposition of Western norms | p = .023 |

| Rank 1 | Impact of colonialism | Rank 8 | Reflective/ critical practice | p = .000 |

| Rank 1 | Impact of colonialism | Rank 9 | Occupational therapy as a vessel that perpetuates the cultural genocide of colonialism | p = .000 |

| Rank 1 | Impact of colonialism | Rank 10 | Advocacy/ innovation | p = .000 |

| Rank 2 | Respecting knowledge | Rank 8 | Reflective/ critical practice | p = .001 |

| Rank 2 | Respecting knowledge | Rank 9 | Occupational therapy as a vessel that perpetuates the cultural genocide of colonialism | p = .001 |

| Rank 2 | Respecting knowledge | Rank 10 | Advocacy/ innovation | p = .000 |

| Rank 3 | Power imbalances | Rank 8 | Reflective/ critical practice | p = .040 |

| Rank 3 | Power imbalances | Rank 9 | Occupational therapy as a vessel that perpetuates the cultural genocide of colonialism | p = .040 |

| Rank 3 | Power imbalances | Rank 10 | Advocacy/ innovation | p = .003 |

| Rank 4 | Indigenous relationships/ partnerships | Rank 10 | Advocacy/ innovation | p = .006 |

Table 2.

Themes Organized by Each Respective Tier.

| Tier | Theme |

|---|---|

| One | Impact of colonialism |

| Respecting knowledge | |

| Power imbalances | |

| Two | Indigenous relationships/ partnerships |

| Cultural safety | |

| Underlying assumptions of the profession | |

| Inappropriate use/ Imposition of Western norms | |

| Three | Reflective/ critical practice |

| Occupational therapy as a vessel that perpetuates cultural genocide of colonialism | |

| Advocacy/ innovation |

Discussion

The Delphi consensus process provided a critical step in the development of a needs survey of the knowledge and experience of occupational therapists in Canada in the field of Indigenous health. The prioritization of themes was intended to focus the survey through weighting questions based on the priority themes to reduce response burden and encourage survey participation; higher priority themes were explored with more questions in the survey than lower priority themes. The phrases italicized below are the themes prioritized through the Delphi process.

Tier 1 Themes: Impact of Colonialism, Respecting Knowledge, Power Imbalances

The impact of colonialism was identified as the highest priority theme by the expert group, recognizing “…European colonization of Canada brought injustice, ill health, and disruption to Indigenous peoples’ traditional occupations and ways of being, knowing and connecting” (CAOT, 2018, p. 1). Occupational therapists in Canada require dual understanding of a) Canada's systematic and deeply troubling history of colonization, and b) present, ongoing colonization processes (CAOT, 2018; Grenier, 2020; Phenix & Valavaara, 2016). To ensure best possible care, recognition of how the eligibility and availability of health care services for Indigenous Peoples continues to be governed by rules perpetuating the legacy of colonial ideas is needed (Jull & Giles, 2012). Occupational therapists are encouraged to make a commitment to decolonization, work in partnership with Indigenous Peoples, and recognize their own position in relation to colonization (Restall et al., 2019) as an essential foundation to practice with Indigenous Peoples.

Respecting knowledge was also highly ranked, highlighting the fundamental need for occupational therapists to be open, inclusive, and welcoming of Indigenous knowledge to build respectful relationships (Viscogliosi et al., 2020; White & Beagan, 2020). When working alongside Indigenous Peoples, “the centrality of ‘nothing about us, without us’ is key to occupational therapy having a relevant and impactful role in contributing toward the rights of Indigenous Peoples to have a quality of life and health outcomes equitable to other populations in Canada” (Restall et al., 2016, p. 265). Hammell (2020) extends this argument, specifically calling on occupational therapists to value Indigenous knowledge and make space for Indigenous Peoples to choose to engage in culturally relevant occupations.

The theme power imbalances acknowledged the need to actively recognize and dismantle imbalances within the therapist-client relationship. Therapists’ primacy as experts in enabling occupation must be ceded in service of allyship, partnership, and reciprocal knowledge exchange with Indigenous Peoples (Gerlach et al., 2014). Acknowledging systemic and pervasive power imbalances links back to the impact of colonialism, as power imbalances are situated within the context of historical and current colonialism (Grenier, 2020).

Tier 2 Themes: Indigenous Relationships/Partnerships, Cultural Safety, Underlying Assumptions of the Profession, Inappropriate Use/Imposition of Western Norms

There is emerging literature on best practices for Indigenous relationships/ partnerships in research (e.g., University of Victoria, n.d.; Wright et al., 2019); however, there is a need for the advancement of partnerships for co-design and delivery of health services (Wright et al., 2019). For example, Wright et al. (2019) suggested researchers engaging with an Indigenous methodology in research (e.g., Two-Eyed Seeing—the braiding of Indigenous and Western perspectives in research) should seek to thoroughly and meaningfully integrate the approaches into their work along with an exploration of ethical standards for its application (Bartlett et al., 2012).

Additionally, occupational therapists must engage in respectful relationships with Indigenous Peoples to provide equitable, safe, and competent care (Jull & Giles, 2012). Zafran et al. (2019) outlined that due to historical and ongoing trauma inflicted on Indigenous Peoples and communities by health care institutions, building sustainable relationships based on commitment, respect, and reciprocity is necessary to work toward reconciliation. CAOT (2018) highlighted the need to enable occupational therapists to provide effective and collaborative services with Indigenous populations via identifying and developing formal alliances and partnerships with Indigenous organizations. It is important to note that well-intended partnerships can be challenged by power imbalances and inequities, and as a result, require thoughtful planning throughout the relationship building process (Storr et al., 2018). Working toward this, occupational therapists must promote cultural safety in their services, and re-examine underlying assumptions of the profession to reflect diverse perspectives and values (Jull & Giles, 2012). Occupational therapists and occupational therapy professional associations, including educational programs, must collaboratively create partnerships with local, provincial, and national Indigenous leaders and stakeholders to enable transformation of the profession (Restall et al., 2016; White & Beagan, 2020).

Cultural safety refers to what is felt or experienced by a client when a healthcare provider communicates in a respectful and inclusive way, empowers the client in decision making, and builds a healthcare relationship in which the client and provider work together to ensure effectiveness of care (Jull & Giles, 2012). It requires moving beyond sensitivity and awareness of cultural differences to analyzing power imbalances, discrimination, and the lasting effects of colonization on social, economic, political, and health inequities (Gerlach, 2012). The TRC (2015) places the onus on health care professionals to reduce health inequities through culturally safe practices, such as challenging systemic structures that may limit the time to create effective therapeutic relationships and rapport building with Indigenous clients (White & Beagan, 2020).

Occupational therapists must examine underlying assumptions of the profession in addition to its perspectives and values to meaningfully practice with cultural safety (Jull & Giles, 2012). Restall et al. (2016) also argue that the profession needs to provide culturally relevant health care and reduce the risk of imposing professional assumptions on Indigenous clients reflecting the dominant cultural assumptions of occupational therapy's Western, white, and middle-class founders (Hammell, 2011). For example, the tenet of “client-centeredness” and a focus on individualism impose a Western settler-colonial worldview, which isolates the client from the importance of community and minimizes the recognition of systemic barriers to occupational participation (Restall et al., 2016; White & Beagan, 2020).

A critical examination of underlying assumptions is necessary to mitigate the inappropriate use/imposition of Western norms. Gerlach and Smith (2015) state that occupational therapists, individually and as a profession, need to expand their clinical, education, and research practices beyond a focus on individuals and their immediate environments. Actions informed by Western understandings of health passively impose specific cultural beliefs and perpetuate power imbalances, rendering practice environments as unsafe spaces (Gerlach & Smith, 2015).

Tier 3 Themes: Reflective/Critical Practice, Occupational Therapy as a Vessel that Perpetuates the Cultural Genocide of Colonialism, Advocacy/Innovation

Occupational therapists must practice cultural humility and reflective/critical practice to systematically examine their professional assumptions and beliefs in consideration of power imbalances that can uphold systems of discrimination (Beagan, 2015; Hammell, 2013). While similar to the theme power imbalances, this theme calls for active engagement from occupational therapists to continuously reflect on their position of power and work towards addressing behaviours that are harmful when working with Indigenous Peoples as a component of cultural safety (Beagan, 2015; Gerlach, 2012). Work toward cultural safety and systemic changes can only begin once occupational therapists are aware of their own values and beliefs, and critically reflect on how this can impact therapeutic relationships with Indigenous Peoples (Jull & Giles, 2012; Restall et al., 2016). The theme of occupational therapy as a vessel that perpetuates the cultural genocide of colonialism builds upon the previous themes, highlighting how occupational therapists operating from implicit biases in their professional values can reinforce health inequities, colonialism, and power imbalances (Gerlach, 2012; White & Beagan, 2020). Practitioners can impose Eurocentric professional values, such as individualism, recreating systems of power in the therapeutic relationship (Gerlach & Smith, 2015; White & Beagan, 2020). As such, occupational therapists may cause harm when working with Indigenous clients by failing to recognize how routine professional actions can impair cultural safety and trauma-informed practice (Gerlach & Smith, 2015; Jacek et al., 2019).

Interestingly, the theme garnering the lowest priority rating was advocacy/innovation. The concepts of advocacy and innovation are included together as they both indicate actions needed to address the harms inherent in the healthcare system and the routine provision of services. Advocacy calls for addressing the environmental factors—social and political systems—that can constrain occupational engagement and contribute to health inequities (Restall et al., 2016). Innovation means being flexible in the implementation of routine practice and service delivery models to best serve Indigenous clients (White & Beagan, 2020). The three themes in this tier must be considered together, as advocacy/innovation actions can be inappropriate if there has not been adequate critical reflection on the legacy of genocide in the occupational therapy profession (White & Beagan, 2020).

The tiers of priority themes suggest a development of concepts that build upon one another from the most foundational, to those that may require more advanced knowledge and understanding. In general, tier one themes are related to having a foundational understanding of colonialism in a general healthcare context that need not be specifically related to occupational therapy. Tier two themes identify essential practices for working with Indigenous Peoples, namely an emphasis on relationship building and cultural safety. Furthermore, this tier tends to focus on the context of the occupational therapy profession, including the biases and assumptions inherent in its tools and theories. Tier three themes can be understood as themes that explicitly uncover the harms associated with these aforementioned assumptions and call for an active dismantling of these biases and systems to work toward reconciliation. It is important to note that these tiers are not distinct, but rather build upon each other and overlap with one another. For example, critical reflexivity is an essential component of cultural safety (a tier two theme) and yet it was prioritized to tier three.

Study Limitations

The researchers acknowledge the following study limitations. A core team of five researchers completed the literature review and led the Delphi process. Although consensus and reflexivity was employed, the nature of qualitative research is such that rater bias is inevitable in the 10 foundational themes. Exclusion of French language literature in the literature review underpinning the first round of the Delphi may also have limited the outcomes. The survey was conducted in English, which limited the involvement of participants who were not fluent in written English. There is a lack of clarity for best practices linking Delphi methodologies to specific consensus goals (Diamond et al., 2014). In addition, the use of this method requires the continued commitment from participants from an expert group throughout the process; this includes being asked a similar question or questions multiple times. During the implementation of the Delphi method, there was a decrease in the number of participants within each round, and it was not possible to determine if the participants were consistent. Additionally, membership within the expert group for the Delphi method was voluntary and with no prior knowledge/experience requirements.

Furthermore, demographic information was not collected from the participants to preserve anonymity in the Delphi process given the relatively small pool of stakeholders. However, this information would have been helpful in assessing representation of participants and in interpreting any differences between responses from Indigenous and non-Indigenous participants. There was limited opportunity for participants to elaborate on their views and decisions regarding the priority and potential overlap of themes. The researchers do not purport that reaching consensus ensured that the best ranking was achieved, as the method merely supports the identified areas that one group of participants or experts consider important or a priority in relation to a specific topic at a specific point in time (Hsu & Sandford, 2007).

Practice Implications

The priorities established through the Delphi process, while intended to guide survey development, can be of value for occupational therapists to guide their process of engaging in reconciliation. Occupational therapists may choose to reflect on their current knowledge gaps in relation to the themes. It should be noted that the tiers are not intended to provide an exhaustive list of concepts in the area of Indigenous health. Rather, they may be helpful as a scaffold to organize learning and/or professional development from building upon foundational ideas (tier 1); to starting or continuing to practice in a culturally safer manner (tier 2); and then working towards decolonization (tier 3). Occupational therapists, regardless of their practice setting or years of practice, are encouraged to review the themes and identify a starting place as their own priority areas to address within the tiers. Moving from intention to action, it may be beneficial to create specific goals or a professional development plan to address learning within the tiers, and to critically reflect on applications of the learning to practice.

The authors of this paper do not suggest that the themes are an end-stage for learning, as critical reflection and learning are ongoing, iterative processes that are essential throughout one's professional career. Furthermore, the authors envision that the results of the Delphi process and prioritized themes will ultimately impact occupational therapists’ priorities and values in practice, with the overall aim to work toward reconciliation and safer practice. It is our hope that occupational therapists will also leverage their resources and social location to advance reconciliation in our Canadian society and systems, beyond the safety of our “practice” lane.

This project generated consensus for priority areas to investigate in a planned survey of occupational therapists across Canada that will help determine overall knowledge gaps related to Indigenous health. While discussion of the processes for survey refinement, pilot testing, and distribution is beyond the scope of this paper, work is ongoing to advance this survey research to explicate the current knowledge of occupational therapists in relation to Indigenous health in Canada relative to the priorities identified. We anticipate that the subsequent survey findings will (1) contribute to and build upon the current contextual body of health knowledge of an occupational therapist working with Indigenous Peoples in Canada, (2) provide insight into how occupational therapists can engage in reconciliation, and (3) support work toward ensuring continued culturally safe practices with Indigenous clients and communities.

Conclusion

The goal of this project was to inform development of a survey to determine the knowledge gaps of occupational therapists across Canada by conducting a Delphi consensus process utilizing an expert group on occupational therapy and Indigenous health to identify survey priorities. Although the aim of developing a survey is the main objective of the research project, it should be acknowledged that the results of the Delphi process have implications for positively influencing occupational therapy practice when working with Indigenous Peoples. Specifically, this project challenges occupational therapists to understand colonialism, their own inherent knowledge gaps, assumptions, and biases, how they may be contributing to harm, and the need to consciously dismantle assumptions and work toward action-oriented reconciliation. It represents an important step toward ultimately 1) producing recommendations for the occupational therapy profession to begin addressing the knowledge gaps identified, and 2) providing occupational therapists with tangible action steps that are in alignment with the TRC calls to action.

Key messages

Active and continuous collaboration through connecting with an Indigenous network via a Delphi process is important for establishing priorities for national needs survey development.

The prioritized themes can assist an occupational therapist to organize learning to build upon foundational concepts related to Indigenous health, start or continue to practice in a culturally safer manner, and work toward decolonization.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cjo-10.1177_00084174221116638 for Knowledge Gaps Regarding Indigenous Health in Occupational Therapy: A Delphi Process by Claire C. Jacek, Kassandra M. Fritz, Monique E. Lizon and Tara L. Packham in Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-cjo-10.1177_00084174221116638 for Knowledge Gaps Regarding Indigenous Health in Occupational Therapy: A Delphi Process by Claire C. Jacek, Kassandra M. Fritz, Monique E. Lizon and Tara L. Packham in Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-cjo-10.1177_00084174221116638 for Knowledge Gaps Regarding Indigenous Health in Occupational Therapy: A Delphi Process by Claire C. Jacek, Kassandra M. Fritz, Monique E. Lizon and Tara L. Packham in Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-cjo-10.1177_00084174221116638 for Knowledge Gaps Regarding Indigenous Health in Occupational Therapy: A Delphi Process by Claire C. Jacek, Kassandra M. Fritz, Monique E. Lizon and Tara L. Packham in Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Matthew Ellies Reg. OT (BC) and Jasper Moedt Reg. OT (BC) for their contribution as members of the research team throughout the systematic literature search, theme identification, and Delphi process. The authors want to acknowledge the active and continuous collaboration and contributions of the Occupational Therapy and Indigenous Health Network (OTIHN) throughout the Delphi process.

Author Biographies

Claire C. Jacek, OT Reg. (Ont) is affiliated with the Occupational Therapy program at the School of Rehabilitation Science, McMaster University, Canada.

Kassandra M. Fritz, OT Reg. (Ont.) is affiliated with the Occupational Therapy program at the School of Rehabilitation Science, McMaster University, Canada.

Monique E. Lizon, OT Reg. (Ont.) is affiliated with the Occupational Therapy program at the School of Rehabilitation Science, McMaster University, Canada.

Tara Packham, PhD, OT Reg. (Ont.) is an occupational therapist and Assistant Professor in the School of Rehabilitation Science, McMaster University, Canada.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Canadian Occupational Therapy Foundation (2020 McMaster Legacy Grant).

Authors’ Note: At the time of the study, C. Jacek and K. Fritz were student occupational therapists at McMaster University in the School of Rehabilitation Science.

Author Contributions: All the authors contributed to study design and methods and preparation of the manuscript.

ORCID iDs: Claire C. Jacek https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6490-8403

Tara L. Packham https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5593-1975

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Bartlett C., Marshall M., Marshall A. (2012). Two-eyed seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 2(4), 331–340. 10.1007/s13412-012-0086-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beagan B. L. (2015). Approaches to culture and diversity: A critical synthesis of occupational therapy literature: Des approches en matière de culture et de diversité: une synthèse critique de la littérature en ergothérapie. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 82(5), 272–282. 10.1177/0008417414567530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. (2018). CAOT Position Statement: Occupational therapy and Indigenous peoples. Retrieved on March 10, 2021 from https://www.caot.ca/document/3700/O%20%20OT%20and%20Aboriginal%20Health.pdf

- Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists (CAOT). (2016). Occupational therapy and Indigenous health network. Retrieved on May 4, 2022 from https://www.caot.ca/site/pd/otn/otahn?nav=sidebar

- Diamond I. R., Grant R. C., Feldman B. M., Pencharz P. B., Ling S. C., Moore A. M., Wales P. W. (2014). Defining consensus: A systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(4), 401–409. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach A. J. (2012). A critical reflection on the concept of cultural safety. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(3), 151–158. 10.2182/cjot.2012.79.3.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach A. J., Smith M. (2015). “Walking side by side”: Being an occupational therapy change agent in partnership with indigenous clients and communities. Occupational Therapy Now, 17(5), 7–9. Retrieved from https://www.caot.ca/document/4014/OTNow_9_15.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach A. J., Sullivan T., Valavaara K., McNeil C. (2014). Turning the gaze inward: Relational practices with aboriginal peoples informed by cultural safety. Occupational Therapy Now, 16(1), 20–21. Retrieved from https://www.caot.ca/document/4003/jan_jan14.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Grenier M. L. (2020). Cultural competency and the reproduction of White supremacy in occupational therapy education. Health Education Journal, 79(6), 633–644. 10.1177/0017896920902515 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammell K. R. W. (2013). Occupation, well-being, and culture: Theory and cultural humility. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 80(4), 224–234. 10.1177/0008417413500465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammell K. W. (2011). Resisting theoretical imperialism in the disciplines of occupational science and occupational therapy. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(1), 27–33. 10.4276/030802211X12947686093602 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammell K. W. (2019). Building globally relevant occupational therapy from the strength of our diversity. World Federation of Occupational Therapists Bulletin, 75(1), 13–26. 10.1080/14473828.2018.1529480 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammell K. W. (2020). Making choices from the choices we have: The contextual-embeddedness of occupational choice. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 87(5), 400–411. 10.1177/0008417420965741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazard-Munro B. (2001). Selected nonparametric techniques. In Hazard-Munro B. (Ed.), Statistical methods for health care research (4th ed., pp. 109136). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C. C., Sandford B. A. (2007). The Delphi technique: Making sense of consensus. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 12(10), 1–8. 10.7275/pdz9-th90 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacek C., Fritz K., Ellies M., Moedt J., Lizon M. (2019). Practicing non-maleficience: Reflecting on reconciliation and doing no harm. Occupational Therapy Now, 21(2), 24–25. Retrieved from https://www.mydigitalpublication.com/publication/?i=656859&p=&l=&m=&ver=&view=&pp= [Google Scholar]

- Jull J. E., Giles A. R. (2012). Health equity, aboriginal peoples and occupational therapy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(2), 70–76. 10.2182/cjot.2012.79.2.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jünger S., Payne S. A., Brine J., Radbruch L., Brearley S. G. (2017). Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: Recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliative Medicine, 31(8), 684–706. 10.1177/0269216317690685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG). (2019). Reclaiming power and place. The final report of the national inquiry into missing and murdered indigenous women and girls. The National Inquiry. Retrieved from https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Final_Report_Vol_1a-1.pdf

- Page M. J. McKenzie J. E. Bossuyt P. M. Boutron I. Hoffmann T. C. Mulrow C. D. Shamseer L. Tetzlaff J. M. Aki E. A. Brennan S. E. Chou R. Glanville J. Grimshaw J. M. Hróbjartsson A. Lalu M. M. Li T. Loder E. W., Mayo-Wilson E., McDonald, S., … Moher D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Medicine, 18(3), e1003583. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phenix A., Valavaara K. (2016). Reflections on the truth and reconciliation commission: Calls to action in occupational therapy. Occupational Therapy Now, 18(6), 17–18. Retrieved from https://www.mydigitalpublication.com/publication/?i=656840&p=&l=&m=&ver=&view=&pp= [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restall G., Gerlach A., Valavaara K., Phenix A. (2016). The truth and reconciliation commission’s calls to action: How will occupational therapists respond? Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 83(5), 266–268. 10.1177/0008417416678850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restall G., Phenix A., Valavaara K. (2019). Advancing reconciliation in scholarship of occupational therapy and indigenous Peoples’ health. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 86(4), 256–261. 10.1177/0008417419872461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storr C., MacLachlan J., Krishna D., Ponnusamy R., Drynan D., Moliner C., Cameron D. (2018). Building sustainable fieldwork partnerships between Canada and India: Finding common goals through evaluation. World Federation of Occupational Therapists Bulletin, 74(1), 34–43. 10.1080/14473828.2018.1432312 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trentham B., Eadie S., Gerlach A., Restall G. (2018). Occupational therapy Canada 2018: A day of reflection and dialogue. Occupational Therapy Now, 20(5), 30–31. Retrieved from https://www.mydigitalpublication.com/publication/?m=61587&i=656851&p=32&ver=html5 [Google Scholar]

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission. (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Retrieved from https://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Honouring_the_Truth_Reconciling_for_the_Future_July_23_2015.pdf

- University of Victoria: Centre for Indigenous Research and Community-Led Engagement. (n.d.). Guiding principles. Retrieved from https://www.uvic.ca/research/centres/circle/about/principles/index.php

- Viscogliosi C., Asselin H., Basile S., Borwick K., Couturier Y., Drolet M. J., Levasseur M. (2020). Importance of indigenous elders’ contributions to individual and community wellness: Results from a scoping review on social participation and intergenerational solidarity. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 111(5), 667–681. 10.17269/s41997-019-00292-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White T., Beagan B. L. (2020). Occupational therapy roles in an indigenous context: An integrative review. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 87(3), 200–210. 10.1177/0008417420924933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Federation of Occupational Therapists (WFOT). (2019). Position Statement Occupational Therapy and Human Rights. Retrieved from https://wfot.org/resources/occupational-therapy-and-human-rights [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wright A. L., Gabel C., Ballantyne M., Jack S. M., Wahoush O. (2019). Using two-eyed seeing in research with indigenous people: An integrative review. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1–19. 10.1177/1609406919869695 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zafran H., Barudin J., Saunders S., Kasperski J. (2019). An occupational therapy program lays a foundation for indigenous partnerships and topics. Occupational Therapy Now, 21(4), 28–29. Retrieved from https://www.caot.ca/document/6768/OT%20program%20lays%20a%20foundation%20for%20Indigenous%20partnerships.pdf [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cjo-10.1177_00084174221116638 for Knowledge Gaps Regarding Indigenous Health in Occupational Therapy: A Delphi Process by Claire C. Jacek, Kassandra M. Fritz, Monique E. Lizon and Tara L. Packham in Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-cjo-10.1177_00084174221116638 for Knowledge Gaps Regarding Indigenous Health in Occupational Therapy: A Delphi Process by Claire C. Jacek, Kassandra M. Fritz, Monique E. Lizon and Tara L. Packham in Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-cjo-10.1177_00084174221116638 for Knowledge Gaps Regarding Indigenous Health in Occupational Therapy: A Delphi Process by Claire C. Jacek, Kassandra M. Fritz, Monique E. Lizon and Tara L. Packham in Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-cjo-10.1177_00084174221116638 for Knowledge Gaps Regarding Indigenous Health in Occupational Therapy: A Delphi Process by Claire C. Jacek, Kassandra M. Fritz, Monique E. Lizon and Tara L. Packham in Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy