Abstract

Background. The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) assists occupational therapists to identify occupational performance problems using a client-centred approach. Since its first publication in 1991, there has been abundant evidence of the ability of the COPM to detect a statistically significant difference as an outcome measure. There has also been a tacit understanding that a difference of 2 points from pre-test to post-test on either Performance or Satisfaction COPM score represents a clinically significant difference. There is however, some confusion about the origins of this claim. Purpose. To ascertain empirical evidence for the claim that a clinically significant difference is a change score ≥2 points. Method. We conducted a scoping review of peer-reviewed literature (1991–2020) for intervention studies using the COPM as an outcome measure and examined intervention type and change scores. Findings. One hundred studies were identified. The COPM was used to assess effectiveness of eight types of occupational therapy interventions. The common belief, however, was not empirically supported that clinical significance can be asserted on the basis of a two-point change in COPM scores. Implications. Further research is needed to test alternative approaches to asserting clinical significance or a minimal clinically important difference.

Keywords: Canadian occupational performance measure, Clinical significance, Scoping review

Abrégé

Description. La Mesure canadienne du rendement occupationnel (MCRO) aide les ergothérapeutes à identifier les problèmes de rendement occupationnel à l’aide d’une approche axée sur la clientèle. Depuis sa première publication, en 1991, il y a eu une abondance de preuves de l’utilité de la MCRO pour mesurer les résultats en détectant une différence statistiquement significative. Il est également reconnu tacitement qu’une différence de 2 points entre les mesures prétest et post-test en ce qui concerne le rendement ou la satisfaction constitue une différence cliniquement significative. Il y a néanmoins une certaine confusion quant à l’origine de cette interprétation. But. Vérifier les preuves empiriques de l’affirmation selon laquelle une différence ≥2 points est cliniquement significative. Méthodologie. Nous avons réalisé une étude de portée de la littérature ayant fait l’objet d’une évaluation par les pairs entre 1991 et 2020 et portant sur des études d’intervention utilisant la MCRO comme critère d’évaluation, et nous avons examiné les types d’interventions et les différences de résultats. Résultats. Cent études ont été recensées. La MCRO a été utilisée pour évaluer l’efficacité de huit types d’interventions en ergothérapie. La croyance commune selon laquelle la signification clinique peut être évaluée sur la base d’une différence de deux points dans les résultats n’a toutefois pas été soutenue empiriquement. Conséquences. Des recherches supplémentaires sont nécessaires pour tester d’autres approches qui permettraient de confirmer la signification clinique ou la présence d’une différence minimale importante sur le plan clinique.

Mots clés: Étude de portée, mesure canadienne du rendement occupationnel (MCRO), signification clinique

Introduction

The Canadian standard for occupational therapy assessment is the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM; Law et al., 2019). The COPM assists occupational therapists to identify occupational performance problems using a client-centred approach. Since the first edition of the COPM was published in 1991 (Law et al., 1990; Pollock et al., 1990), there has been abundant evidence of the responsiveness of the COPM—that is, the ability of the COPM to detect a statistically significant difference or change over time as an outcome measure (Carswell et al., 2004; McColl et al., 2006). There has also been a tacit understanding that a difference of 2 points from pre-test to post-test on either Performance or Satisfaction represents a clinically significant difference on the COPM. This paper sets out to determine if there is empirical evidence for that assertion.

The idea of a clinically significant difference, or a minimal clinically important difference, is that there is a threshold for change beyond which clients, their support systems, and health professionals can detect a change that has positive functional implications. Virtually any change in scores can be shown to be statistically significant given a large enough sample, but clinical significance represents the real-world relevance of a change. A clinically significant change corresponds to actual functional or appreciable, meaningful change.

The empirical evidence for the claim that a 2-point change was clinically significant, however, is elusive. The original pilot studies upon which the COPM was based made no reference to a clinically significant difference. These included two small studies (N1 = 12; N2 = 37) contained in a preliminary report in the World Federation of Occupational Therapists Bulletin documenting progress on the emerging measure (Baptiste et al., 1993).

In 1994, Law and colleagues published the results of a more ambitious pilot study, involving 219 occupational therapists sampled randomly from the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists’ database. The study included 256 of their clients from 55 practice sites. This study found that the COPM could be administered in about half an hour, resulted in the successful detection of a wide range of occupational performance problems, and was responsive to change over time (Law et al., 1994a). Responsiveness to change was evidenced by change scores of ≥1.5 times the standard deviation for both Performance and Satisfaction. No mention was made of clinical significance.

The first mention of clinical significance in the official documents associated with the COPM appears in the 2nd edition of the COPM manual (Law et al., 1994a, 1994b). In the section on psychometric properties, the authors cite their own study involving 30 outpatients in a rehabilitation day centre. Change scores on the COPM correlated significantly with changes in client self-ratings (on a 7-point scale). This approach, although frequently used, does not substantiate the threshold value of 2.0 for a minimally important clinical difference.

In another study, the COPM was used in a program evaluation of a day treatment program in adult mental health (N = 49). Ratings were taken before and after a 12-week intervention program and a change of 2 points on both Performance and Satisfaction was established as the standard for the program to demonstrate an effect. Results indicated that 78% of respondents achieved this standard of a change of 2 points or greater. It is important to note that this standard was not empirically established, but rather was ordained a priori by the program staff.

The 3rd edition of the COPM manual (Law et al., 1998) contains the same information, while the 4th edition (2005) mentions clinical significance in two places. In the frequently asked questions (p. 20), the following phrase appears: “Our research has indicated that changes of two or more points on the COPM are clinically important.” Also, in the section discussing the use of the COPM in program evaluation, the text cites the 2nd edition as a source for the following quote stating that, “Previous research has provided evidence that a change of 2.0 or more points is clinically significant (Law et al., 1994a, 1994b)” (p. 50).

In 2006, the authors published a monograph entitled, Research on the COPM (McColl et al., 2006). This book acknowledged that the evidence was sparse for the interpretation of clinical significance. It recommended “some benchmarks for the kinds of changes that constitute a two-point difference” (p. 84).

Most recently, both the 5th edition (2014) and the revised 5th edition (2019) state that: “Research evidence from outcome studies across many different populations and types of interventions has shown that a change of 2 points or more on the COPM represents an important change” (p. 17 in both editions).

In the 30 years since the publication of the COPM in 1991, this idea of a 2-point change indicating clinical significance has become firmly lodged in the collective consciousness of the profession. The origins of this claim however, have become lost in the mists of time. The purpose of the present study is to perform an exhaustive search of intervention studies using the COPM as an outcome measure, to ascertain if there is any empirical evidence for the claim that a clinically significant difference on the COPM is one that exceeds the threshold of 2 points on change scores. The rationale for this undertaking lies in its implications for the client-centred practice of occupational therapy, for the education of evidence-informed practitioners, and for the body of knowledge emerging through the efforts of occupational therapy researchers, in the context of using and interpreting the COPM.

Method

A scoping review was chosen to map the evidence for clinical significance in the literature and to show where gaps exist. The standard of evidence was insufficient for a systematic review, and thus a scoping review appeared to be the best approach to identify the language and concepts used in the occupational therapy literature to discuss clinical significance and the COPM.

The scoping review followed Arksey and O’Malley's approach (2005), which typically unfolds in five steps.

Research Question: The first is to specify the research question: “What magnitude of change score represents a clinically significant difference on the COPM?”

Search Strategy: Three data sources were searched: CINAHL, Medline, and the COPM archive. Articles were included in the dataset if they featured the search terms “COPM” OR “Canadian Occupational Performance Measure” in the title, abstract or keywords; and were published between 1991 and 2020.

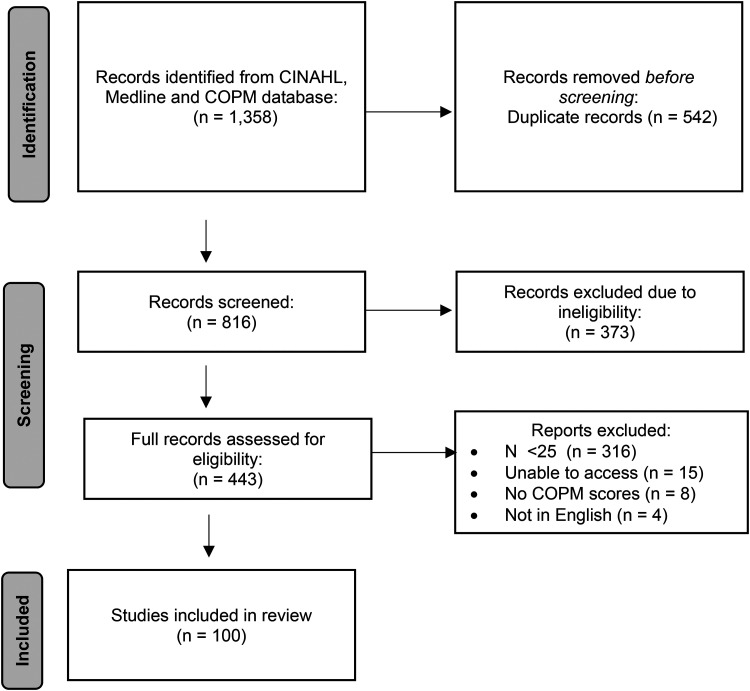

Data Extraction: The initial search produced 1,358 hits, of which 542 were eliminated as duplicates, leaving 816 articles. These 816 titles and abstracts were reviewed by at least two authors to ensure that the article represented an intervention study and the COPM was used as an outcome measure in the study. A further 373 articles were excluded on the basis of these two criteria, leaving 443 articles.

Assess Eligibility: The full text of these remaining 443 articles was reviewed by at least two authors, applying two additional exclusion criteria. Articles were eliminated if the COPM Satisfaction or Performance scores were not published; or the sample size was <25 per group, because sample sizes ≥25 offer some assurance of stable estimates of group means. Articles were also excluded if they were descriptive or psychometric studies and were not based on an intervention study. This resulted in further eliminating 337 articles for the reasons stated in Figure 1, thus leaving a final dataset of 100 articles.

Analyze Data: The contents of this dataset of 100 articles are described in Table 1 and detailed in the Appendix (Supplemental Materials). The interventions studied were classified according to the eight types of interventions described by McColl & Law (2013) (Law & McColl, 2010; see Box 1). We extracted COPM change scores for Performance and Satisfaction from each article, categorized them by type of intervention, and calculated the frequency of articles reporting change scores ≥2 points and citing definitions of clinical significance. Further, we examined the sources cited by articles to track the origins of a clinically significant difference for the COPM.

Figure 1.

Search strategy.

Table 1.

Sample Description (N = 100).

| N/% a | |

|---|---|

| Year of publication | |

| 2000–2005 | 13 |

| 2006–2010 | 16 |

| 2011–2015 | 34 |

| 2016–2020 | 37 |

| Country of study | |

| Sweden | 18 |

| Canada | 15 |

| USA | 15 |

| Australia | 11 |

| UK | 8 |

| Netherlands | 7 |

| Norway | 3 |

| China, Denmark, England, Germany, Ireland, Israel, Scotland, Slovenia, Switzerland | 2 |

| Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Iceland, India, Italy, Korea, Turkey, New Zealand | 1 |

| Age group | |

| Adults incl. seniors | 58 |

| Children | 29 |

| Older adults only | 10 |

| Setting | |

| Institutional | 34 |

| Community | 24 |

| Rehabilitation centre | 16 |

| Out-patient | 14 |

| Research setting | 8 |

| Not specified | 4 |

| Group versus individual-level intervention | |

| Individual | 58 |

| Both | 18 |

| Group | 14 |

| Not specified | 8 |

Note. Some studies were conducted in multiple countries & settings, thus total number may not tally to 100.

Box 1.

Eight Types of Intervention in Occupational Therapy.

| 1. EDUCATION | Learning more about one's condition, options for improvement and prevention of complications. |

| 2. ENVIRONMENTAL MODIFICATION | Altering the non-human environment to enhance function, including adaptive equipment, cueing, accessibility. |

| 3. OCCUPATIONAL DEVELOPMENT | Optimizing participation in complex, meaningful occupations |

| 4. SKILL DEVELOPMENT | Improving performance of specific tasks that are the building blocks of occupation. |

| 5. SUPPORT PROVISION | Providing physical or psychological support by the therapist. |

| 6. SUPPORT ENHANCEMENT | Enhancing the ability of the support network to provide the necessary support for occupational performance. |

| 7. TASK ADAPTATION | Modifying a task to permit it to be accomplished in a different manner. |

| 8. TRAINING | Enhancing physical, psychological, cognitive or social performance, using non-purposeful activities. |

Source: McColl & Law (2013).

Findings

The evidence base is growing steadily on the COPM, with Sweden, Canada, and the USA contributing almost half of the studies. Two-thirds of the studies cited involved adults or seniors and one-third involved children. The 100 articles in the dataset were all intervention studies involving the COPM as an outcome measure. The most commonly reported interventions were Skill Development (n = 21) and Training (n = 24), together responsible for almost half (45%) of the articles. The least commonly seen interventions were Task Adaptation (n = 1) and Occupational Development (n = 2). There were 19 articles where either the intervention was not an occupational therapy intervention (e.g., surgery), or where the intervention was not specified.

Change scores for Performance and Satisfaction on the COPM were examined for each intervention type (see Table 2). The greatest change in both Performance and Satisfaction was in the one study classified as Task Adaptation, pertaining specifically to the use of an orthosis, with an improvement of 4.9 points for Performance and 4.6 points for Satisfaction. Based on COPM change scores, the next highest changes are those related to Support Provision (nine interventions including coaching and psychological support), which produced average change scores of 3.6 for Performance and 4.5 for Satisfaction; and Support Enhancement (six interventions providing education to parents and teachers on how to support clients), resulting in average change scores of 2.5 for Performance and 2.8 for Satisfaction.

Table 2.

Performance and Satisfaction Score Change Based on Intervention Type.

| Intervention type | Total No. of studies | Performance change a | Satisfaction change a | Sample size range | Related articles b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | ||||

| Task adaptation | 1 | 4.90 (0.00) | 4.60 (0.00) | 20 | |

| Support provision | 9 | 3.64 (1.15) | 4.47 (1.42) | 25–7048 | 9, 13, 25, 40, 49, 71, 77, 78, 79 |

| Support enhancement | 6 | 2.53 (0.28) | 2.78 (0.30) | 31–91 | 2, 19, 31, 52, 60, 62 |

| Occupational development | 2 | 2.27 (0.18) | 2.94 (0.28) | 78–88 | 57, 63 |

| Training | 24 | 2.16 (0.17) | 2.01 (0.21) | 25–2068 | 3, 7, 16, 24, 28, 30, 34, 36, 37, 39, 53, 54, 56, 59, 68, 69, 75, 76, 80, 81, 84, 92, 98, 100 |

| Environmental modification | 8 | 1.97 (0.14) | 2.27 (0.19) | 27–353 | 35, 43, 45, 50, 61, 64, 85, 87 |

| Education | 10 | 1.96 (0.30) | 2.39 (0.37) | 25–150 | 17, 18, 22, 26, 27, 38, 41, 44, 46, 90 |

| Skill development | 21 | 1.69 (0.11) | 2.08 (0.11) | 26–181 | 15, 21, 23, 29, 32, 33, 47, 48, 55, 65, 66, 70, 72, 73, 74, 82, 83, 93, 94, 95, 96 |

| Unspecified | 19 | 1.92 (0.08) | 2.37 (0.07) | 25–191 | 1, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 11, 12, 14, 42, 51, 58, 67, 86, 88, 89, 91, 97, 99 |

| Total | 100 | 2.70 (0.15) | 3.11 (0.19) | 728 | 1–100 |

Change scores represent weighted averages (weighted by sample size).

Study numbers from Appendix A.

The smallest change scores were interventions classified as Skill Development, including grasp retraining, hand movements, home-based therapy, and life skills coaching (21 articles with average changes of 1.7 in Performance and 2.1 in Satisfaction); Education, on diagnosis, self-management, and symptom recognition (10 articles with average changes of 2.0 in Performance and 2.4 in Satisfaction); and Environmental Modification, including the use of smart technology and assistive devices (8 articles with average changes of 2.0 in Performance and 2.3 in Satisfaction).

As mentioned previously, the conventional wisdom is that a 2.0 point difference in COPM Performance or Satisfaction represents a clinically significant difference. Using this definition, 69 of the 100 articles detected a difference >2 on Performance, and 73 articles reported a difference >2 on Satisfaction.

The main purpose of this study was to explore the origin of the assertion that a 2.0 point difference represents a clinically significant change. Fifty-three of the articles in our dataset mentioned a clinically significant difference, of which 44 provided a source to substantiate this assertion. Table 3 contains the articles cited and definitions used by articles in our dataset to claim a clinically significant difference. The table is organized chronologically according to year of publication of the definition cited for clinical significance.

Table 3.

References Cited for Definitions of Clinical Significance on the COPM (n = 44 Articles).

| Articles that citeda | Reference for clinical significance | Definition of clinical significance |

|---|---|---|

| 26, 99 | Law et al. (1990) | “Second, the measure should be responsive to clinically important changes expected from occupational therapy intervention (DNHW & CAOT, 1987; Kirshner & Guyatt, 1985; Law, 1987).” (p. 86) |

| 4 | Law et al. (1991) (COPM 1st ed.) | No direct reference to a specific clinically significant difference value is provided. |

| 33, 41, 83 | Law et al. (1994a, 1994b) | “Client scores changed significantly on both performance and satisfaction upon reassessment. The mean change scores in performance and satisfaction for clients, approximately 1.5 times the standard deviation in scores, indicates that the COPM is sensitive to changes in perception of occupational performance by clients.” (p. 195) |

| 33 | Law et al. (1994a, 1994b) (COPM 2nd ed.) | “The change scores on the COPM were correlated with changes in function as rated on Likert scales [by clients, family and therapist]. (p. 27) … “The BOS [Behavioural Observation Scale] ratings corroborated the children's perceptions of significant improvements.” (p. 30) … “Changes of 2 points on the rating scales for Performance and Satisfaction were established as the standard for the program” (p. 30) |

| 27, 62, 69, 70, 71, 98 | Law et al. (1998) (COPM 3rd ed.) | Same as 2nd ed. (1994) |

| 28 | McColl et al. (2000) | “A number of studies have provided assurances of clinical utility and responsiveness of the COPM ( Law et al., 1994a , 1994b; Mew & Fossey, 1996; Toomey et al., 1995; Wilcox, 1994).” (p. 23) |

| 76 | Griffiths et al. (2000) | No mention of the COPM |

| 81 | Carpenter et al. (2016) | “The difference between the initial and the subsequent scores gives the measure of outcome, with a 2-point difference in either direction indicating significant change.” (p. 18) ( Law et al., 1994a , 1994b) |

| 4, 30, 34, 36, 65, 82, 86, 90 | Carswell et al. (2004) | “The difference between the initial and subsequent scores (change score) indicates an outcome. A change score of two or more is considered clinically significant (Law et al., 1991, 1994a, 1994b , 1998).” (p. 211) |

| 2, 17, 23, 24, 32, 35, 37, 39, 40, 54, 55, 64, 66, 87, 92 | Law et al. (2005a, 2005b) (COPM 4th ed.) | “Our research has indicated that changes of two or more points on the COPM are clinically important.” (p. 20) … “Previous research has provided evidence that a change of 2.0 or more points is clinically significant ( Law et al., 1994a, 1994b).” (p. 50) |

| 60 | Law et al. (2005b) | “A difference of 2 points on the COPM is considered to be a clinically important change ( Law et al., 2005a , 2005b; COPM 4th Ed., p. 293) … The results of this study demonstrate that for children and youth receiving home and community occupational therapy services, a statistically and clinically important improvement in occupational performance outcomes was observed within a 6-month time period.” (p. p. 294) |

| 72 | McColl et al. (2006) | “Nine of 10 scored a clinically significant increase of 2 points or more for performance and/or satisfaction for one or more of their goals (Candler, 2003)” (p. 33) … “Pilot studies have shown that clinically significant change is two (2) points or more, thus some of the statistically significant differences seen may not have been clinically significant.” (p. 49) … “Nearly three-quarters of the studies showed changes in the clinically significant range; that is, greater than two (2) points.” (p.50) |

| 34 | Sakzewski et al. (2007) | “The COPM and GAS were the only measures that reported good responsiveness for detecting meaningful clinical change.” (p. 235) |

| 34 | Cusick et al. (2009) | “Responsiveness was also explored by comparing pre- and post-intervention scores of the adapted COPM to the published minimum clinically important difference of 2 points … The adapted COPM demonstrates an ability to detect change above the published minimum clinically important difference of 2 points (Law, 2006) b .” (p. 763) |

| 41, 83 | Phipps & Richardson (2007) | “Previous studies show that a change of 2 or more points on the COPM usually represents at least .75 of a standard deviation, which is considered a moderate-to-large change and a clinically important difference as judged by clients and families ( Law et al., 1994a , 1994b; Sanford et al., 1994). In this study, all change scores for performance and satisfaction for the overall sample and within each diagnostic group were well above 2 points, ranging from 2.85 to 4.07 points.” (p. 331) |

| 3, 42 | Eyssen et al. (2011) | “The optimal decision threshold (cutoff value) of the COPM for evaluating improvement perceived by the client ranged between 0.90 and 1.90 and was higher for the satisfaction scores than for the performance scores … These cutoff values were lower than the 2-point difference indicated in the COPM manual as clinically important ( Law et al., 2005a , 2005b).” (p. 524) |

| 43, 86, 89 | Law et al. (2014) (COPM 5th ed.) | “Research evidence from outcomes studies across many different populations and types of interventions has shown that a change of 2 points or more on the COPM represents an important change.” (p. 17). |

| 4 | Nieuwenhuizen et al. (2014) | “Change of two or more points on the COPM-P is considered clinically significant by the developers of the instrument ( Law et al., 2005a , 2005b) … A clinically significant improvement of two or more points on the COPM-P was scored by 44 (63.8%) patients.” (p. 740) |

| 65 | Tuntland et al. (2016) | “…it is stated in the COPM manual that a change of 2 points implies an important change.1 However, evidence to support this statement is not confirmed. We find it not plausible that the minimal important change (MIC) is constant, irrespective of diagnoses, severity of disability, age, and the COPM-P versus COPM-S dimensions … The MIC was calculated to be 3.0 points and 3.2 points for COPM-P and COPM-S, respectively, which is above the suggested MIC of 2 points in the COPM manual ( Law et al., 2014 ).” (p. 412) |

Values listed under “Articles that cited” correspond with reference numbers of data set—see Appendix A; several articles cited more than one source.

This reference to Law (2006) refers to the Frequently Asked Questions on the COPM website (www.thecopm.ca/FAQ).

The oldest reference to a clinically significant difference on the COPM is an article by Law et al. (1990), published before the COPM manual, describing the development and conceptual basis for the COPM. It was cited by two articles in the dataset (Gustafsson et al., 2012; Willis et al., 2018). Law's article mentioned clinical significance only as an aspect of the responsiveness of a scale. It makes no mention of the value of 2, but simply states that clinical significance is important for responsiveness.

The most frequently cited source to substantiate the value of a clinically significant difference, not surprisingly, is the COPM manual itself. It was cited by 27 articles, 61% of the 44 articles that offer a citation. The 1st edition of the COPM manual (1991) was referenced twice, the 2nd edition (1994) once, the 3rd edition (1998) 6 times, the 4th edition (2005) 15 times, and the 5th edition (2014) 3 times. However, upon examination, the 1st edition (1991) does not mention clinical significance at all, while the 2nd and 3rd editions (1994, 1998) note that an average change of 1.0 (±2.66) on Performance was correlated at .62 with self-ratings by clients in a rehabilitation setting. An average change score of 1.1 (±2.72) on Satisfaction correlated at .53 with self-rated change. Both of these correlation coefficients were significant, thus supporting the responsiveness of the COPM (i.e., its ability to detect change). They offer no evidence for a threshold value of 2.

The 2nd and 3rd editions also cite results from another pilot study in a mental health setting, where 78% (38 of 49) of respondents reported a change of 2 points or greater in both Performance and Satisfaction on the COPM. This study however provides no external validation that such a change is clinically important or coincides with meaningful functional changes. The 4th (2005), 5th (2014), and revised 5th (2019) editions of the COPM manual all mention clinical significance, but offer no further empirical evidence.

In 1994, Law and colleagues published a report of the initial pilot testing of the COPM. In a mixed sample, they observed that the average change in Performance improved by 1.6× the standard deviation, while Satisfaction scores improved 1.5× the SD. No mention was made of clinical significance, except to say that research is needed to understand how COPM scores relate to “real changes in occupational performance” (Law et al., 1994a, 1994b, p. 197). Yet this study was cited by three articles in our dataset as evidence for the 2-point difference as an indicator of clinical significance (Kendrick et al., 2012; Lexell et al., 2014; Speicher et al., 2014).

Griffiths and associates (2000) were cited by one article in our dataset (Sewell et al., 2005) to substantiate a claim of clinical significance ≥2 points, but curiously, Griffiths and colleagues’ study of functional recovery with COPD did not even use the COPM as an outcome measure. There is no mention of the COPM or of the value of 2 points.

One article in our dataset (Siggeirsdottir et al., 2004) cited Carpenter et al. (2016) as the reference for their assertion of clinical significance. Carpenter and associates made an oblique reference to a 2-point difference being clinically significant in their study of a pain management program. They offered no new empirical evidence, but cited the COPM manual, 2nd edition, to assert clinical significance.

Carswell et al. (2004) were cited by eight articles in our dataset to support an explicit reference to a 2-point change being clinically significant. This article was a systematic review of 86 empirical studies using the COPM. In the introduction, the authors cited the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd editions of the COPM manual to substantiate the statement that a “change score of 2 or more is considered clinically significant” (p. 211).

Five more studies are each cited once (Cusick et al., 2009; Law et al., 2005b; McColl et al., 2006; Nieuwenhuizen et al., 2014; Sakzewski et al., 2007) and one is cited twice (Phipps & Richardson, 2007) by articles in our dataset to substantiate the idea that a change score of 2 or more can be considered the minimally clinically-significant difference on the COPM. None of these studies offers new empirical evidence, but rather each simply reiterates previous claims in either the COPM manual or website as the basis for their assertion of clinical significance.

Only two recent studies provided empirical evidence on what constitutes a minimal clinically significant change: Eyssen et al. (2011) and Tuntland et al. (2016). Eyssen et al. (2011) sought to determine cut-off scores on the COPM that reflect resolution of occupational performance problems. Clients were asked to rate their problems as not resolved, partially resolved, or totally resolved at the conclusion of treatment (3 months post-intervention; n = 138 adults with various conditions). The study showed that clients perceived resolution of occupational performance problems at change scores of 0.9 for Performance, and 1.9 for Satisfaction. These values represent a reasonable estimate of clinical significance, and yet are lower than the commonly-held value of 2.

Tuntland et al. (2016) collected data from 225 community-dwelling older adults at baseline and after 10 weeks of rehabilitation. They asked clients to indicate if they felt that a “minimally important change” had taken place. Clients’ ratings of at least “a little improved” were associated with COPM Performance change scores of 3 points or more, and Satisfaction scores that changed 3.2 points or more, in excess of the 2 point difference attributed to the COPM manuals.

Discussion

This scoping review examined 100 articles from the peer-reviewed literature on the use of the COPM in intervention studies. The aim was to discover if an empirical basis exists for the commonly stated threshold of 2.0 on Performance and Satisfaction change scores as a clinically significant difference.

Almost half of the articles analyzed (n = 47) did not mention a clinically significant difference at all, while just over half (n = 53) alluded to the idea that 2.0 was a reasonable value at which to assert clinical significance, of which 44 offered a specific reference. Twenty-five of those articles cited the COPM manual as their source. Nine articles provided no citation for the cut-off of 2 as the basis for their claim of clinical significance.

No empirical evidence appears to exist to substantiate the claim that a change score of 2.0 or greater on COPM Performance or Satisfaction ratings represents a clinically significant difference. Of the articles in our dataset, 41 of 44 cited sources that did not actually offer any empirical evidence for the threshold value of 2.

Three articles cited sources that had conducted original research as a basis for claiming clinical significance (Arman et al., 2019; Liew et al., 2018; Rijpkema et al., 2020). These articles cited two sources as evidence for claiming clinical significance: Eyssen et al. (2011) and Tuntland and associates (2016). Interestingly, neither of these sources supports the value of 2 for clinical significance. Based on their data, Eyssen et al. (2011) suggested that the correct threshold for clinical significance was lower than 2, while Tuntland et al. (2016) suggested it was greater than 2. Furthermore, Tuntland et al. suggested that a fixed threshold was unlikely, stating it was “not plausible that the minimal important change (MIC) is constant” (p. 412). They assumed it would vary depending on the characteristics of the clients, their occupational performance problems, and other contextual factors. This idea is supported by Page (2014), who advocates for using a multiple of the standard deviation as an effective way of asserting clinical significance.

According to Jaeschke et al. (1989), there are three common approaches for asserting a clinically significant change—also referred to as a “minimal clinically important change” or MCID, or an “optimal decision threshold” (Eyssen et al., 2011), meaning the smallest change in an outcome measure that can be assumed to correspond with meaningful functional change. The anchor-based method compares the change scores observed on the measure of interest with a real-world indicator, like client self-evaluation. This method was used in the COPM pilot studies and reported in the COPM manual 2nd edition (Law et al., 1994a, 1994b). It was also the approach used by Sakzewski et al. (2007), who compared COPM scores with Goal Attainment Scales (GAS) as rated by clients, and by Eyssen et al., (2011), who compared with client perceptions of the resolution of problems.

The distribution method is the second approach to asserting clinical significance. This method suggests that the minimally important difference should correspond to at least the standard error of measurement, which is calculated by dividing the standard deviation by the square root of N, thus correcting for the degree of precision that can be asserted based on sample size. This approach was partially applied by Law et al. (1994a, 1994b), in the pilot test that found meaningful change scores typically at 1.5× the standard deviations. Phipps and Richardson (2007) also refer to the distribution method, but found changes of only 0.75× the standard deviation to be meaningful. In neither case is the correction for sample size used by adding the denominator of square root of N.

The third method for determining clinical significance is the opinion-based method. This approach uses expert consensus to identify a threshold value. It appears that this method was used to suggest that value of 2.0 as the basis for clinical significance on the COPM. The authors, in consultation with therapists and clients in the pilot tests, distilled their collective knowledge to assert that a change of 20% of the total possible score (i.e., 2 points out of 10) was a reasonable level for asserting clinical significance.

Implications of the Findings

The results of this review substantiate the responsiveness of the COPM—that is, its ability to detect statistically significant change over time in occupational Performance and Satisfaction. This review also demonstrates, however, there is no empirical support for the common belief that a clinically important change is consistently 2.0, regardless of client population, occupational performance problems, or other factors like setting or treatment approach.

For clinicians, the lack of support for a two-point clinically significant difference probably has the greatest implication, in that they cannot reasonably assume that they have achieved something important and worthwhile simply because of a difference of 2 points on COPM scores over the course of treatment. It is possible that change scores less than 2 are important. Instead, clinicians should substantiate the claim of clinical significance through client self-report of meaningful functional gains. This should not be a hardship in a practice that is already client-centred. For educators, the implication is also clear that further discussion is needed with occupational therapy students about the difference between clinical and statistical significance, and the duty of the therapist to validate clinical significance in the context of the therapeutic relationship and practice setting.

For researchers, there are two important implications. First, for those using the COPM as an outcome measure—the purpose for which it was created—it is not appropriate to claim clinical significance on the basis of an average change score of 2 or more from pre-test to post-test. Instead, is necessary to employ additional measures, rationales, or new evidence to support clinical significance. Second, there is now a clear need for new, high-quality psychometric research examining clinical significance of the COPM under a variety of different circumstances and with clients who have different health conditions.

It is a limitation of this study that the extended scoping review methodology was not employed, and stakeholder consultation was not undertaken (Colquhoun et al., 2014). This is a promising direction for future research.

Conclusion

To date, the only evidence to claim that a change of score by two or more on the COPM is clinically significant is opinion-based. It would strengthen this claim to have evidence from the anchor-based or distribution-based approaches to determining a minimal clinically important difference.

Key messages

Between 1991 and 2020, 100 intervention studies were found in the peer-reviewed literature using the COPM as an outcome measure; about five studies per year since its publication.

Of the eight types of interventions used by occupational therapists (McColl & Law, 2013), the largest differences in COPM Performance and Satisfaction scores were seen with Task Adaptation, Support Provision, and Support Enhancement.

The clinical significance of a two-point change in COPM scores has not been empirically demonstrated. Further research should test alternative approaches to asserting clinical significance, or a minimal clinically important difference.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cjo-10.1177_00084174221142177 for A Clinically Significant Difference on the COPM: A Review by Mary Ann McColl, Celine Boyer Denis, Kate-Lin Douglas, Justin Gilmour, Nicole Haveman, Meaghan Petersen, Brittany Presswell and Mary Law in Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy

Author Biographies

Mary Ann McColl is Professor in Occupational Therapy at Queen's University, Kingston, ON, Canada, and author of the COPM.

Celine Boyer Denis is an occupational therapist.

Kate-Lin Douglas is an occupational therapist at KidsAbility in Waterloo, ON, Canada.

Justin Gilmour is an occupational therapist at E-Clinic United Healing in Mississauga, ON, Canada.

Nicole Haveman is an occupational therapist at Waterloo-Wellington/Central West Home and Community Care Support Services.

Meaghan Petersen is an occupational therapist.

Brittany Presswell is an occupational therapist at Woodstock Rehabilitation Clinic in Woodstock, ON, Canada.

Mary Law is Professor Emerita in Occupational Therapy at McMaster University, Hamilton, ON Canada, and author of the COPM.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Mary Ann McColl https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9498-4642

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arman N., Tarakci E., Tarakci D., Kasapcopur O. (2019). Effects of video games-based task-oriented activity training (Xbox 360 Kinect) on activity performance and participation in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 98(3), 174–181. 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptiste S. E., Law M., Pollock N., Polatajko H., McColl M. A., Carswell-Opzoomer A. (1993). The Canadian occupational performance measure. World Federation of Occupational Therapists Bulletin, 28(1), 57–51. 10.1080/14473828.1993.11785290 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Candler C. (2003). Sensory integration and therapeutic riding at summer camp: Occupational performance outcomes. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 23, (3), 51–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter L., Baker G. A., Tyldesley B. (2016). The use of the Canadian occupational performance measure as an outcome of a pain management program. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68(1), 16–22. 10.1177/000841740106800102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carswell A., McColl M. A., Baptiste S., Law M., Polatajko H., Pollock N. (2004). The Canadian occupational performance measure: A research and clinical literature review. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(4), 210–222. 10.1177/000841740407100406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun N., Levac D., O’Brien K. K., Straus S., Tricco A. C., Perrier L., Kastner M., Moher D. (2014). Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods and reporting. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67, 1291–1294. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusick A., Lannin N. A., Lowe K. (2009). Adapting the Canadian occupational performance measure for use in a paediatric clinical trial. Disability and Rehabilitation, 29(10), 761–766. 10.1080/09638280600929201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of National Health & Welfare / Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists (DNHW & CAOT). (1987). Toward outcome measures in occupational therapy (H39-114/1987E). Dept. National Health & Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- Eyssen I. C. J. M., Steultjens M. P. M., Oud T. A. M., Bolt E. M., Maasdam A., Dekker J. (2011). Responsiveness of the Canadian occupational performance measure. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 48(5), 517–528. 10.1682/jrrd.2010.06.0110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths T. L., Burr M. L., Campbell I. A., Lewis-Jenkins V., Mullins J., Shiels K., Turner-Lawlor P. J., Payne N., Newcombe R. G., Lonescu A. A., Thomas J., Tunbridge J. (2000). Results at 1 year of outpatient multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet (British Edition), 355(9201), 362–368. 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)07042-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson L., Liddle J., Liang P., Pachana N., Hoyle M., Mitchell G., Mckenna K., Gustafsson L., Liddle J., Liang P., Pachana N., Hoyle M., Mitchell G., Mckenna K. (2012). A driving cessation program to identify and improve transport and lifestyle issues of older retired and retiring drivers. International Psychogeriatrics, 24(5), 794–802. 10.1017/S1041610211002560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke R., Singer J., Guyatt G. H. (1989). Measurement of health status. Ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Controlled Clinical Trials, 10(4), 407–415. 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90005-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendrick D., Silverberg N. D., Barlow S., Miller W. C., Moffat J. (2012). Acquired brain injury self-management programme: A pilot study. Brain Injury, 26(10), 1243–1249. 10.3109/02699052.2012.672787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirshner B., Guyatt G. (1985). A methodological framework for assessing health and disease. Journal of Chronic Disease, 38, 27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law M. (1987). Measurement in occupational therapy: Scientific criteria for evaluation. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 54, 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Law M., Baptiste S., Carswell A., McColl M. A., Polatajko H. J., Pollock N. (1991). Canadian occupational performance measure (COPM). CAOT Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Law M., Baptiste S., Carswell A., McColl M. A., Polatajko H. J., Pollock N. (1998). Canadian occupational performance measure (3rd ed.). CAOT Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Law M., Baptiste S., Carswell A., McColl M. A., Polatajko H. J., Pollock N. (2014). Canadian occupational performance measure (5th ed.). CAOT Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Law M., Baptiste S., Carswell A., McColl M. A., Polatajko H. J., Pollock N. (2019). Canadian occupational performance measure (5th ed. revised.). COPM Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Law M., Baptiste S., Carswell A., McColl M. A., Polatajko H. J., Pollock N. (1994a). Canadian occupational performance measure (2nd ed.). CAOT Publications. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law M., Baptiste S., Carswell A., McColl M. A., Polatajko H. J., Pollock N. (2005a). Canadian occupational performance measure (4th ed.). CAOT Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Law M., Baptiste S., McColl M., Opzoomer A., Polatajko H., Pollock N. (1990). The Canadian occupational performance measure: An outcome measure for occupational therapy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 57(2), 82–87. 10.1177/000841749005700207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law M., Majnemer A., McColl M. A., Bosch J., Hanna S., Wilkins S., Birch S., Telford J., Stewart D. (2005b). Home and community occupational therapy for children and youth: A before and after study. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(5), 289–297. 10.1177/000841740507200505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law M., Mccoll M. A. (2010). Interventions, effects and outcomes in occupational therapy: Adults and older adults. Slack Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Law M., Polatajko H., Pollock N., McColl M. A., Carswell A., Baptiste S. (1994b). Pilot testing of the Canadian occupational performance measure: Clinical and measurement issues. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61(4), 191–197. 10.1177/000841749406100403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lexell E. M., Flansbjer U.-B., Lexell J. (2014). Self-perceived performance and satisfaction with performance of daily activities in persons with multiple sclerosis following interdisciplinary rehabilitation. Disability & Rehabilitation, 36(5), 373–378. 10.3109/09638288.2013.797506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liew P. Y., Stewart K., Khan D., Arnup S. J., Scheinberg A. (2018). Intrathecal baclofen therapy in children: An analysis of individualized goals. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 60(4), 367–373. 10.1111/dmcn.13660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McColl M. A., Carswell A., Law M. (2006). Research on the Canadian occupational performance measure: An annotated resource. CAOT Publications. [Google Scholar]

- McColl M. A., Law M. (2013). Interventions affecting self care, productivity and leisure among adults: A scoping review. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 33(2), 110–119. 10.3928/15394492-20130222-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McColl M. A., Paterson M., Davies D., Doubt L., Law M. (2000). Validity and community utility of the Canadian occupational performance measure. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 67(1), 22–30. 10.1177/000841740006700105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mew M. M., Fossey E. (1996). Client-centred aspects of clinical reasoning during an initial asessment using the COPM. Australian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 43, 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuizen M. G., de Groot S., Janssen T. W. J., van der Maas L. C. C., Beckerman H. (2014). Canadian occupational performance measure performance scale: Validity and responsiveness in chronic pain. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 51(5), 727–746. 10.1682/jrrd.2012.12.0221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page P. (2014). Beyond statistical significance: Clinical interpretation of rehabilitation research literature. The International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 9 (5), 726–736. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipps S., Richardson P. (2007). Occupational therapy outcomes for clients with traumatic brain injury and stroke using the Canadian occupational performance measure. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61(3), 328–334. 10.5014/ajot.61.3.328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock N., Law M., Baptiste S., McColl M., Opzoomer A., Polatajko H. (1990). Occupational performance measures: A review based on the guidelines for client-centred practice of occupational therapy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 57(2), 77–81. 10.1177/000841749005700206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijpkema C., Duijts S. F. A., Stuiver M. M. (2020). Reasons for and outcome of occupational therapy consultation and treatment in the context of multidisciplinary cancer rehabilitation: A historical cohort study. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 67(3), 260–268. 10.1111/1440-1630.12649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakzewski L., Boyd R., Ziviani J. (2007). Clinimetric properties of participation measures for 5- to 13-year-old children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 49(3), 232–240. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00232.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford J., Law M., Swanson L., Guyatt G. (1994). Assessing clinically important change as an outcome of rehabilitation in older adults. Proceedings of the American Society of Aging. San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Sewell L., Singh S. J., Willliams J. E. A., Collier R., Morgan M. D. L. (2005). Can individualized rehabilitation improve functional independence in elderly patients with COPD? Chest, 128(3), 1194–1200. 10.1378/chest.128.3.1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siggeirsdóttir K., Alfredsdóttir U., Einarsdóttir G., Jónsson B. Y. (2004). A new approach in vocational rehabilitation in Iceland: Preliminary report. Work, 22(1), 3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speicher S. M., Walter K. H., Chard K. M. (2014). Interdisciplinary residential treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury: Effects on symptom severity and occupational performance and satisfaction. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68(4), 412–421. 10.5014/ajot.2014.011304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey M., Nicholson D., Carswell A. (1995). The clinical utility of the COPM: A study of community based occupational therapists. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62, 242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuntland H., Aaslund M., Langeland E., Espehaug B., Kjeken I. (2016). Psychometric properties of the Canadian occupational performance measure in home-dwelling older adults. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 9(1), 411–423. 10.2147/jmdh.s113727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox A. (1994). A study of verbal guidance for children with development coordination disorder. Unpublished master's thesis, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario. [Google Scholar]

- Willis C., Nyquist A., Jahnsen R., Elliott C., Ullenhag A. (2018). Enabling physical activity participation for children and youth with disabilities following a goal-directed, family-centred intervention. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 77, 30–39. 10.1016/j.ridd.2018.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cjo-10.1177_00084174221142177 for A Clinically Significant Difference on the COPM: A Review by Mary Ann McColl, Celine Boyer Denis, Kate-Lin Douglas, Justin Gilmour, Nicole Haveman, Meaghan Petersen, Brittany Presswell and Mary Law in Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy