Abstract

Musculoskeletal (MSK) health impairments contribute substantially to the pain and disability burden in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), yet health systems strengthening (HSS) responses are nascent in these settings. We aimed to explore the contemporary context, framed as challenges and opportunities, for improving population-level prevention and management of MSK health in LMICs using secondary qualitative data from a previous study exploring HSS priorities for MSK health globally and (2) to contextualize these findings through a primary analysis of health policies for integrated management of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in select LMICs. Part 1: 12 transcripts of interviews with LMIC-based key informants (KIs) were inductively analysed. Part 2: systematic content analysis of health policies for integrated care of NCDs where KIs were resident (Argentina, Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, India, Kenya, Malaysia, Philippines and South Africa). A thematic framework of LMIC-relevant challenges and opportunities was empirically derived and organized around five meta-themes: (1) MSK health is a low priority; (2) social determinants adversely affect MSK health; (3) healthcare system issues de-prioritize MSK health; (4) economic constraints restrict system capacity to direct and mobilize resources to MSK health; and (5) build research capacity. Twelve policy documents were included, describing explicit foci on cardiovascular disease (100%), diabetes (100%), respiratory conditions (100%) and cancer (89%); none explicitly focused on MSK health. Policy strategies were coded into three categories: (1) general principles for people-centred NCD care, (2) service delivery and (3) system strengthening. Four policies described strategies to address MSK health in some way, mostly related to injury care. Priorities and opportunities for HSS for MSK health identified by KIs aligned with broader strategies targeting NCDs identified in the policies. MSK health is not currently prioritized in NCD health policies among selected LMICs. However, opportunities to address the MSK-attributed disability burden exist through integrating MSK-specific HSS initiatives with initiatives targeting NCDs generally and injury and trauma care.

Keywords: Low- and middle-income, policy, qualitative, health system, non-communicable, musculoskeletal

Key messages.

Musculoskeletal (MSK) impairments (including MSK conditions, MSK pain and MSK injury and trauma) are leading contributors to the disability burden in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), yet health systems strengthening (HSS) responses in these settings are limited.

Health systems in LMICs are limited in their capacity to respond to the burden of MSK impairment outside injury and trauma due to a focus on other health conditions, limited human and financial resources and infrastructure, limited surveillance capacity, political instability and prevailing sociocultural attitudes and beliefs. Health policies for integrated management of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in LMICs do not focus on MSK health.

Although system strengthening responses for MSK health in select LMICs are limited, there are opportunities within national strategies for prevention and control of NCDs to arrest the disability burden.

Efforts to raise awareness of MSK health in LMICs and appropriate system strengthening actions, such as policy integration opportunities, will be important not only for addressing MSK-attributed prevention and care of disability across the life course but also to achieve health and quality-of-life gains for people living with other NCDs.

Introduction

Pain and disability are the unifying features across musculoskeletal (MSK) health impairments. A substantial contribution to the burden of disease in the low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is attributed to MSK health impairments, including chronic MSK conditions, MSK pain and MSK injury and trauma. Irrespective of economic development, impaired MSK health consistently features in the top three conditions contributing to the greatest disability burden across most countries and the condition group most in need of rehabilitation services (Vos et al., 2020; Cieza et al., 2021). MSK conditions are also among the leading causes accounting for more than 75% of disease burden attributed to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and injuries for the poorest billion people aged 5–40 years and those greater than 40 years of age (Bukhman et al., 2020). The rate of increase in disease burden for MSK conditions and transport injuries by 100 000 population is greater in LMICs compared with high-income settings (Vos et al., 2020). Furthermore, the MSK-attributed burden in LMICs is likely under-estimated due to limitations in MSK health surveillance (Ferreira et al., 2021). Collectively, these factors drive substantial threats to human capital, to opportunities for child health and healthy ageing and to prosperity of LMIC communities, particularly those made vulnerable due to geography, age and socioeconomic circumstances (Brennan-Olsen et al., 2017; Bukhman et al., 2020).

A burden–response gap for MSK health persists, particularly for LMICs (Sharma et al., 2019). Yet, global health targets for NCDs focus on conditions associated with mortality such as cancer, cardiovascular, diabetes and lung disease, aligned with performance indicators of the Sustainability Development Goals (SDGs). In this paradigm, a greater emphasis is placed on reducing premature mortality from NCDs, rather than preventing and managing disability, despite an increasing life expectancy and years lived in poor health globally (GBD 2019 Demographics Collaborators, 2020). While this lens to health systems strengthening (HSS) is appropriate and effective for addressing NCD-related mortality, health states associated with disability, principally MSK impairments and MSK injury, remain relatively deprioritized. This context is particularly relevant to LMICs given the strong relationship between socioeconomic development and healthy life expectancy at age 65 years (GBD 2019 Demographics Collaborators, 2020) and where social security, long-term care systems and age-related pensions are rarely available to support living with disability (Pot et al., 2018). This approach also limits opportunities for health and quality-of-life gains for people living with (or at risk of) NCDs, given that MSK health impairments frequently co-exist with other NCDs (Simoes et al., 2017) and are a risk factor for developing NCDs (Williams et al., 2018). In light of current policy and financing for NCD care internationally, this MSK burden–response gap is likely to persist without targeted HSS responses (Jailobaeva et al., 2021).

There is emerging evidence of effectiveness of HSS approaches in LMICs, such as community engagement interventions and leadership programmes (Witter et al., 2019). However, these approaches relate to more strongly prioritized health challenges such as communicable, maternal, neonatal and nutritional diseases (CMNNDs), while evidence related to the specific context for MSK health is nascent. Our current understanding of, and evidence for, HSS responses to the health, economic, human capital and social burden imposed by MSK health impairment is largely derived from high-income countries. This highlights a significant knowledge gap in creating and implementing solutions with LMICs. For example, health policy response evaluations have only been investigated in high-income settings (Briggs et al., 2019b; 2020; 2021a; Skempes et al., 2022), creating uncertainty about the MSK-relevant policy landscape in LMICs. Understandably, HSS initiatives developed for high-income settings likely require local adaptation to be appropriate to lower-resourced settings (Briggs et al., 2021b). Here, consultation with local health systems experts and people with lived experience, in tandem with examination of the contemporary policy landscape in LMICs, are important considerations for HSS solutions (Heller et al., 2019; Seward et al., 2021). In a recent qualitative study, we reported the results of 31 interviews with representative KIs from low-income, middle-income and high-income countries on their perceived value of a global strategic response to MSK health and the priorities for HSS for MSK health (Briggs et al., 2021b). We analysed those data from a global perspective, thus specific challenges and opportunities in LMICs were not derived or reported. Secondary analysis of qualitative data can address this knowledge gap by enabling further targeted exploration of data from the parent study (Ruggiano and Perry, 2019).

The aim of this study was to explore context, opportunities and priorities for HSS for MSK health in select LMICs. We define HSS as initiatives that sustainably improve one or more of the functions of the health system, historically defined by the six health systems building blocks: service delivery, health workforce, health information systems, access to essential medicines, financing and leadership/governance. Our objectives were to (1) describe the contemporary context, framed as challenges and opportunities, for improving population-level prevention and management of MSK health in LMICs using secondary qualitative data, and (2) to contextualize these findings through a primary analysis of health policies for integrated management of NCDs in select LMICs.

Methods

Design

A two-part study, undertaken between August 2021 and February 2022, extended a larger programme of work (Briggs et al., 2021a; 2021b; 2021c). Part 1 involved a secondary analysis of a subset of qualitative data, using an alternative analysis frame to the parent study, consistent with principles for secondary qualitative data (Ruggiano and Perry, 2019). Part 2 involved a primary systematic analysis of health policies concerning integrated management of NCDs. The manuscript is reported in alignment with the Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research checklist and Guidance for reporting patients and the public short form and standards for secondary qualitative analysis (Supplementary files 1–3) (Tong et al., 2007; Staniszewska et al., 2017; Ruggiano and Perry, 2019). For the purpose of this report, ‘MSK health’ includes established MSK conditions, MSK pain and MSK injury and trauma.

Part 1: secondary qualitative analysis

Design

A secondary analysis of qualitative data from a larger (parent) study involving 31 international KIs was performed (Briggs et al., 2021b). A subset of data acquired from KIs from LMICs were reanalysed, consistent with best-practice analytic rationales and approaches (Hinds et al., 1997; Ruggiano and Perry, 2019). The methods for the parent study have been described in detail previously (Briggs et al., 2021b). A brief overview is provided below, as relevant to the secondary analysis.

Sampling and recruitment

In the parent study, 31 KIs were sampled across six eligibility criteria to achieve diversity in the important domains of actors, ideas, contexts and characteristics (Shiffman and Smith, 2007) (Supplementary file 4). We applied maximum heterogeneity sampling to achieve variation across clinical disciplines, sectors, geographies and regional economic development. Furthermore, consistent with a previous approach (Shawar et al., 2015), KIs were sampled as affiliates or representatives of national or international health organizations to enable perspectives to extend beyond just those of the individual. Sampling, data collection and data analysis were undertaken from June to August 2020. The Sydney-based home office of the Global Alliance for Musculoskeletal Health (G-MUSC) undertook recruitment (5 June to 22 July 2020) via email and snowball recruitment independent of the research team.

In this secondary analysis, using purposive sampling, we included KIs who were LMIC-resident at the time of data collection or had explicitly referred to their prior experience working in an LMIC when interviewed. Based on these criteria, 12 unique transcripts were included.

Data collection

An interview schedule [described previously (Briggs et al., 2021b)] was iteratively developed and piloted by the multidisciplinary research team (Supplementary file 5). Three team members (AMB, JEJ, HS) collected data using one-to-one interviews in English, using secure videoconference software and following a standardized approach determined a priori. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriptionist for member checking and analysis.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using a phased, grounded theory approach from August 2021 to January 2022 by four researchers (AMB, JEJ, SS, HS) (Strauss and Corbin, 1998); three collected and analysed data in the parent study (Briggs et al., 2021b). Consistent with recommendations for secondary analysis of qualitative data (Ruggiano and Perry, 2019), an additional analyst (SS) participated in the current analysis bringing a unique perspective and insights based on their extensive LMIC lived experience.

Phase 1: open coding

Two researchers purposefully re-read the 12 uncoded transcripts, creating memos and identifying key concepts around context, challenges, opportunities and priorities for LMIC HSS in MSK health (JEJ, SS). Each independently analysed four randomly selected transcripts using line-by-line inductive coding to create a formative coding framework. The formative framework was then independently reviewed against the four transcripts, followed by an analysts meeting to refine the framework. Next, the two analysts independently open-coded the remaining eight transcripts using a combination of deductive and inductive methods.

Phase 2: axial coding

A composite list of codes was developed, and through an iterative process of comparing inductively derived codes, reviewing the transcripts and discussion of concepts, codes were grouped into logical categories. The analysts discussed and iterated the coding framework.

Phase 3: selective coding

Through a constant comparative approach between groups of codes, transcripts and documented memos, key themes were developed and relationships between these categories were identified to establish an initial thematic framework, which was then discussed and iterated among the four analysts. Key themes were then aggregated under meta-themes for intuitive grouping.

Phase 4: consultation and feedback

Consistent with recommendations by Stocker et al. (2021), the thematic framework was presented to international KIs via an online forum for feedback, to consider whether the framework faithfully represented the contemporary social, cultural and political contexts in their respective countries. Finally, the same four analysts further iterated the thematic framework and compared the results with the parent study to ensure accuracy and avoid duplication and redundancies. Data are presented in de-identified format to preserve anonymity.

Part 2: health policy content analysis

Design

Systematic content analysis of health policy documents focused on integrated management of NCDs among the nine LMICs represented in Part 1, aligned to where KIs were resident at the time of data collection and following previously developed methods (Briggs et al., 2019b). The purpose of this analysis was to elucidate a contemporary health system policy context to enable interpretation of the qualitative data. We considered an analysis of policies targeting NCDs to be the most appropriate policy focus for MSK health, consistent with previous research (Briggs et al., 2019b).

Document search and selection

Policy documents were systematically identified using the following strategies:

Extraction from the WHO NCD document repository. Established in 2016, the repository categorizes policies, strategies and action plans for NCDs and their risk factors, NCD clinical guidelines and NCD legislation and regulatory frameworks submitted by Member States in response to the periodic WHO NCD Country Capacity Survey (most recently undertaken in 2019).

Extraction from the WHO MiNDbank database. Established in 2014, WHO MiNDbank is an online platform providing access to international resources and national/regional level policies, strategies, laws and service standards for mental health, substance abuse, disability, general health, NCDs, human rights, development, children and youth, and older persons.

Desktop Internet search powered by Google by the research team.

Desktop Internet search by local (country-level) investigators on the National Ministry of Health website for each country and/or liaison with National Ministry of Health contacts.

Inclusion criteria

Consistent with earlier approaches, we defined a ‘policy document’ as any national health policy, strategy or action plan (Adebiyi et al., 2019; Briggs et al., 2019b). Two reviewers (AMB, JJY) assessed the eligibility of policy documents against the following inclusion criteria, with disagreement resolved by consensus meeting:

policies described a national approach to the prevention and/or management of NCDs from an integrated perspective, i.e. the policies needed to address two or more NCDs; thus, single disease-specific policies were not included;

policies were the most contemporary for the country (i.e. superseded policies were not included). In order to judge whether a policy was superseded, reviewers examined whether the contents (e.g. vision, goals, target areas and scope) of older policies were reasonably reflected in an updated version. Where the reviewers agreed that the scope and foci of an older policy were reflected in a new version, the older version was excluded. Where an older version contained information (e.g. targets, foci and strategies) that was substantially different to a newer policy, both documents were included.

Where reviewers could not make a decision about the appropriateness of a document for inclusion/exclusion, contact was made with the Ministry of Health in the relevant country and/or the local investigator for clarification or advice.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (AMB JJY) extracted data from included health policies, following a pre-established protocol. A standard data extraction template, developed previously (Briggs et al., 2019b), ensured consistency in document review and data extraction (Supplementary file 6). The template guided extraction on vision and scope of the policy; health conditions included; what objectives/aims were proposed; how they would be achieved through specific strategies/actions; extent of explicit integration of MSK conditions, mobility/functional impairment, persistent non-cancer pain, or injury and trauma within the scope of prevention/management for NCDs; and quality appraisal using a previously developed tool (7 items scored from 0 to 2; total score range 0–14; higher scores indicating greater internal validity) for which measurement properties have been established (Briggs et al., 2019b). Documents published in non-English languages were translated using online translation software.

Data analysis

Descriptive data for the policies were reported as direct text excerpts. Other text data were content analysed (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005), using established methods (Cunningham and Wells, 2017; Briggs et al., 2019a; 2019b) and in accordance with the Ready, Extract, Analyse and Distill (READ) guidelines (Dalglish et al., 2021). Using methods developed for a similar purpose (Briggs et al., 2019b), we deductively applied a detailed base coding framework consisting of 42 first-order codes derived previously, to the text excerpts, describing strategies to achieve the stated objectives of policies. In this base framework, 30 codes described general strategies for prevention/control of NCDs, while 12 codes described MSK-specific strategies. Two analysts (AMB, JJY) coded excerpts against the base coding framework with frequencies of first-order codes calculated to provide an indication of overall prominence. Where existing codes needed revision in scope or new codes were required, coding framework changes were applied inductively.

The discrete results derived from both Parts 1 and 2 were considered in the overall interpretation of the body of evidence. Interpreting both parts provided a broader systems perspective than that would be otherwise possible when considering one of the parts in isolation.

Results

Part 1: qualitative study

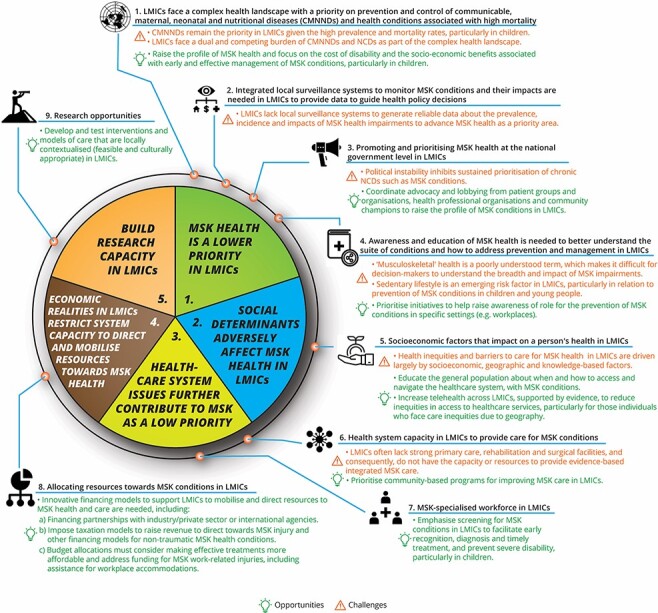

Transcripts from 12 KIs representing a range of sampling criteria, clinical disciplines and 12 LMICs were included in the secondary analysis; demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Ten KIs were resident across nine LMICs at the time of data collection (Argentina, Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, India, Kenya, Malaysia, Philippines and South Africa). Two were not resident in an LMIC but had explicitly discussed their prior work experience in an LMIC, including Botswana, Dominican Republic, India and Tanzania. Supplementary file 7 provides sociodemographic and health characteristics profiles of the 12 LMICs. Data were synthesized into five meta-themes, supported by a number of key themes and sub-themes, structured as challenges and opportunities. The most prominent and novel LMIC-specific challenges and opportunities from the secondary analysis are described below, across four of the five meta-themes, and summarized in Fig. 1. Supplementary file 8 and Fig. 1 provide the full suite of data and highlight where findings are novel to the secondary analysis, have a partial overlap with or are similar to the parent study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sub-set of KIs in the secondary analysis, n = 12

| Characteristics | N (%) unless stated otherwise |

|---|---|

| Sampling categoriesa: | |

|

9 (75.0) |

|

4 (33.3) |

|

1 (8.3) |

|

0 |

|

3 (25.0) |

|

2 (16.7) |

| Gender (female) | 3 (25.0) |

| Highest level of education: | |

|

1 (8.3) |

|

6 (50.0) |

|

4 (33.3) |

|

1 (8.3) |

| Clinical disciplines | |

|

1 (8.3) |

|

1 (8.3) |

|

1 (8.3) |

|

1 (8.3) |

|

1 (8.3) |

|

1 (8.3) |

|

1 (8.3) |

|

3 (25.0) |

| Age; mean (SD), range years | 57.6 (11.3), 41–77 |

| Years of professional experience in healthcare; mean (SD), range years | 29.7 (11.7), 10–45 |

| Years of lived experienced with the MSK condition; mean (SD), range years | 20.5 (0.7), 20–21 |

| Nations represented by KIs (World Bank Geographic Region; World Bank income band for Fiscal Year 2022) | |

|

1 (8.3) |

|

1 (8.3) |

|

2 (16.7) |

|

1 (8.3) |

|

1 (8.3) |

|

1 (8.3) |

|

3 (25.0) |

|

1 (8.3) |

|

1 (8.3) |

|

1 (8.3) |

|

1 (8.3) |

|

1 (8.3) |

KIs could be identified as representing more than one sampling category.

KIs representing these nations were not resident at the time of data collection, but explicitly referred to their experience in working in these settings.

Figure 1.

Summary of LMICs-specific challenges and opportunities for HSS in MSK health, derived from Part 1. The centre circle represents meta-themes 1–5. Key themes (1–8) are summarized outside of the meta-themes, along with the unique opportunities (in green and indicated with light bulb icon) and challenges (in orange and indicated with warning icon) for each theme. Data presented reflect the challenges and opportunities that are novel or have nuances relevant to LMICs. The full suite of data is presented in Supplementary file 8

1. Meta-theme: MSK health is a lower priority in LMICs.

Challenge: CMMNDs remain the priority in LMICs given their high prevalence and mortality rates, particularly in children.

KIs articulated that LMICs face a complex health landscape, requiring a primary focus on strengthening prevention and control of CMNNDs. Consequently, MSK health is not considered a priority.

‘Yes, other health issues like, for example, communicable diseases like HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis. The government budget, more budget goes to communicable diseases and these non-communicable diseases are not really considered a top priority issue…My general thinking about musculoskeletal conditions is it seems like it is one of the forgotten or side-lined issues.’ (ID30)

Challenge: LMICs increasingly face the dual and competing burden of both CMNNDs and NCDs as part of the complex health landscape.

KIs highlighted the increasing challenge of addressing the dual burden of both CMNNDs and NCDs competing for the same limited health resources. LMICs focus on NCDs associated with a high mortality burden, rather than those with a larger morbidity burden.

“This is the type of background that nations, some of the nations, like ours on this continent [Africa] also have to deal with other diseases that seem to take the limelight. You have tuberculosis, you have malaria, you have HIV, then you have also issues like cancer and diabetes. These seem to take the lion’s share in terms of attention and in terms of provision, so MSK is a little bit on the back burner, as you’d put it.” (ID3)

Challenge: LMICs lack local surveillance systems to generate reliable data about the incidence, prevalence and health and economic impacts of MSK health impairments to demonstrate the case for advancing MSK health as a priority area.

A lack of reliable local burden of disease data was identified by KIs as compounding the de-prioritization of MSK health in LMICs and challenging governments to recognize and respond to the burden.

‘Firstly, I think that we need representative data of the country, as I said. We need to know the prevalence of musculoskeletal pain to understand if our country is the same as we observe in other countries…Without the numbers, it’s very difficult to take action. I understand that it is not an easy task in any country, but especially in low and middle income countries…the popularization of data science methods and resources to collect, clean and analyse big data will help in this task in the upcoming future.’ (ID28)

Challenge: Political instability inhibits sustained prioritization of chronic NCDs such as MSK conditions. MSK conditions have a less visible impact and require long-term investment, creating a disincentive for political action on MSK health.

Political instability and discontinuity at LMIC government levels were identified by KIs as disrupting progress in raising awareness or advocating for resourcing towards MSK health. Additionally, the long-term investment required for MSK health is often a political disincentive.

‘The problem here is that our governments usually change very often and they change from one side to completely the other, so when you have been doing a little bit of work - and that happened to us, we reached some people and we were doing some work and then election, everybody changed and you are starting from scratch again… every time we change government they completely change their objectives, so nobody wants to get involved with chronic diseases and long term results.’ (ID13)

2. Meta-theme: Social determinants adversely affect MSK health in LMICs

Challenge: A myriad of factors limits equitable access to MSK healthcare in LMICs.

Barriers to equitable access to care were perceived by KIs as largely driven by socioeconomic, geographic and knowledge-based factors (e.g. health literacy and sociocultural attitudes and beliefs), frequently resulting in unmet care access, needs and imposing disparities in health outcomes for MSK conditions in LMICs, particularly for vulnerable population groups.

‘Sometimes other things in developing and low and middle income countries, some external factors and not only the pain condition, like the musculoskeletal pain condition, some economic factors and also social factors could interfere in the treatment and also in the way people live here. Some people here live very, very close to violence and poor quality of life without money.’ (ID28)

3. Meta-theme: Healthcare system issues further contribute to MSK as a low priority

Opportunity: Emphasis should be placed on screening for MSK conditions in LMICs to facilitate early recognition, diagnosis and treatment to prevent severe disability, particularly in children.

Recognizing constraints on the healthcare system in LMICs to provide comprehensive and integrated care for MSK conditions, KIs placed strong emphasis on primary/community care–based screening for MSK conditions, particularly in children, to facilitate early diagnosis and intervention.

‘One more thing we can do is to select the high risk cases right from the beginning, from pre-school age and school age, especially kids from the diabetic families… I would like to use the phrase “catch them young”.’ (ID18)

4. Meta-theme: Economic realities in LMICs restrict system capacity to direct and mobilize resources towards MSK health

Opportunity: Impose taxation models to raise revenue to direct towards MSK injury and other financing models for non-traumatic MSK health conditions.

Recognizing the limited financial resources available in LMICs to direct towards MSK health, a few KIs advocated for innovative financing models, similar to those implemented to fund care of road traffic trauma victims, as well as public–private partnerships to fund a range of non-traumatic MSK conditions.

‘I think for musculoskeletal conditions in general, we don’t have any model for financing here, but the trauma component is very clear. I think there are a number of ideas where you can finance the care of the injured, maybe if you can add a cent or two onto fuel, then that tax can be used for the care of the injured. Similarly, the tax on the automobile industry can be used to promote the care of the injured… So I think there are conditions like injuries within that group which can have a different finance model, but for rest of the conditions I think we need to search for alternative financing models like, as you said, the third party payers or insurance or government health system taking care of the burden of, say, arthritis or back pain.’ (ID19)

Part 2: policy analysis

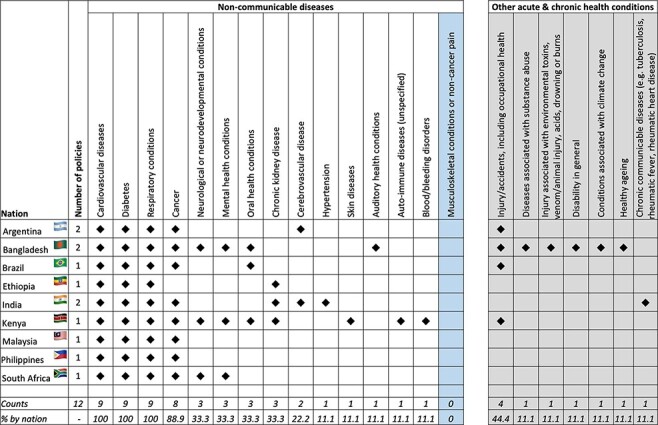

From a yield of 35 potentially eligible documents, 12 (34.3%) met the inclusion criteria across the nine LMICs (Ministerio De Salud, Argentina, 2009; 2013; Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, 2013; 2017a; Department of Health, Philippines, 2016; Ministry of Health, Malaysia, 2016; Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, 2017b; 2018; Ministry of Health, Ethiopia, 2020; Ministério Da Saúde Brasília, 2021; Ministry of Health, Republic of Kenya, 2021; National Department of Health, Republic of South Africa, 2022) (see the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses-aligned flowchart in Supplementary file 9 and Table 2), while the 23 excluded documents are listed in Supplementary file 10. We did not analyse health policies for three LMICs (Botswana, Dominican Republic and United Republic of Tanzania) where two KIs had previously worked. This decision related to KIs being unable to discuss health systems in these three countries from a contemporary perspective during their initial interview and their more limited lived experience in these settings compared with other KIs. Although the majority of countries had policies with an explicit focus on chronic cardiovascular diseases (100%), diabetes (100%), respiratory conditions (100%) and cancer (89%), none had policies with an explicit focus on MSK health conditions or non-cancer pain (Fig. 2). All policies contained a background commentary, with eight (67%) making some reference to MSK health. One Bangladeshi policy referred to MSK conditions and mobility impairment within scope of its actions, although this was not stated as a specific strategic priority area (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, 2017b). Four countries had policies with a focus on likely MSK-relevant injury and occupational health, including road traffic trauma, homicide and violence, suicide and self-harm, falls and injuries related to substance abuse and workplace accidents (Ministerio De Salud, Argentina, 2009; Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, 2017b; Ministério Da Saúde Brasília, 2021; Ministry of Health, Republic of Kenya, 2021). The Kenyan policy included unspecified auto-immune diseases within its scope (Ministry of Health, Republic of Kenya, 2021), which may intuitively extend to inflammatory arthritides, although this was not clarified.

Table 2.

Summary of included policy documents (n = 12) and key characteristics of integrated management of NCDs in LMICs

| MSKc health explicitly included in policy scope | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nation (World Bank income band; regiona) | Policy title (year of publication); timespan | Scope (NCD prevention; NCD management; both) | Aim or vision | MSKc cited in background (yes/No.) | MSK conditions | Mobility or functional impairment | Persistent non-cancer pain | Injury or trauma | Stated objectives or strategies relevant to prevention or management of MSK health (all, some and none) | Internal validity score (0–14) |

| Argentina [upper middle; Latin America and the Caribbean] (Ministerio De Salud, Argentina, 2009) | Resolution 1083/2009: Approve the National Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases and the Healthy Argentina National Plan (2009); not applicableb | Prevention + management | To reduce the prevalence of risk factors and death from chronic NCDs the general population, through health promotion, reorientation of services for health and surveillance of NCDs and risk factors. Second, the Healthy Argentina National Plan aims to coordinate population-based actions aimed at combating comprehensively the main risk factors for chronic NCDs, such as physical inactivity, poor diet and tobacco use. | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | All | 10 |

| Argentina [upper middle; Latin America and the Caribbean] (Ministerio De Salud, Argentina, 2013) | Estrategia Nacional de Prevencion y Control de Enfermedades No Transmisibles (2013); not applicableb | Prevention only | To make available to local governments a series of strategies, resources and effective tools to prevent chronic NCDs at the community level. | Yes | No | No | No | No | All | 8 |

| Bangladesh [lower middle; South Asia] (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, 2018) | Multisectoral Action Plan for Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable diseases 2018–2025 (2018); 2018–2025 | Prevention + management | To contribute towards making Bangladesh free of the avoidable burden of NCD deaths and disability. | Yes | No | No | No | No | Some | 13 |

| Bangladesh [lower middle; South Asia] (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, 2017b) | Fourth Health, Population and Nutrition Sector Programme (4th HPNSP) Operational Plan—Non-communicable Diseases. January 2017—June 2022 (2017); 2017–2022 | Prevention + management | To reduce mortality and morbidity of NCDs in Bangladesh through control of risk factors and improving health service delivery. | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Some | 11 |

| Brazil [upper middle; Latin America and the Caribbean] (Ministério Da Saúde Brasília, 2021) | Plano de Ações Estratégicas para o Enfrentamento das Doenças Crônicas e Agravos não Transmissíveis no Brasil, 2021–2030 (2021); 2021–2030b | Prevention + management | To present a guideline for the prevention of risk factors for NCDs and for the promotion of health of the population, aiming to solve health inequalities. | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | All | 9 |

| Ethiopia [low; Sub-Saharan Africa] (Ministry of Health, Ethiopia, 2020) | National Strategic Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Major Non-communicable Diseases 2013–2017 EFY (2020/21–2024/25) (2020); 2020–2025 | Management only | To see healthy, productive and prosperous Ethiopians free from preventable and avoidable NCDs | Yes | No | No | No | No | Some | 13 |

| India [lower middle; South Asia] (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, 2017a) | National Multisectoral Strategic Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2017–2022 (2017); 2017–2022 | Prevention + management | All Indians enjoy the highest attainable status of health, well-being and quality of life at all ages, free of preventable NCDs and premature death. | No | No | No | No | No | All | 12 |

| India [lower middle; South Asia] (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, 2013) | National Program for Prevention and Control of Cancer, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke: Operational Guidelines (Revised: 2013–17) (2013); 2013–2017 | Prevention + management | Awareness generation for behaviour and lifestyle changes, screening and early diagnosis of persons with a high level of risk factors and their referral to appropriate treatment facilities, i.e. Community Health Centres and District Hospital for management of NCDs. | No | No | No | No | No | Some | 5 |

| Kenya [lower middle; Sub-Saharan Africa] (Ministry of Health, Republic of Kenya, 2021) | National Strategic Plan for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases 2021/22–2025/26 (2021); 2021–2026 | Prevention + management | To halt and reverse the rising burden of NCDs through effective multisectoral collaboration and partnerships by ensuring that Kenyans receive the highest attainable standard of NCD continuum of care that is accessible, affordable, quality, equitable and sustainable; thus, alleviating suffering, disease and death for their well-being and socio-economic development. | Yes | No | No | Nno | Yes | Some | 13 |

| Malaysia [upper middle; East Asia and Pacific] (Ministry of Health, Malaysia, 2016) | National Strategic Plan for Non-Communicable Disease: Medium Term Strategic Plan to Further Strengthen the NCD Prevention and Control Program in Malaysia (2016–2025) (2016); 2016–2025 | Prevention + management | To reduce the burden of NCDs in Malaysia. | No | No | No | No | No | All | 8 |

| Philippines [lower middle; East Asia and Pacific] (Department of Health, Philippines, 2016) | Philippine Multisectoral Strategic Plan for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases 2017–2025 (2016); 2017–2025 | Prevention + management | To attain a Philippines free of the preventable burden of NCDs through addressing risk factors and promoting healthier environments. | no | no | no | no | no | some | 9 |

| South Africa [lower middle; Sub-Saharan Africa] (National Department of Health, Republic of South Africa, 2022) | National Strategic Plan for the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases 2022–2027 (2022); 2022–2027 | Prevention + management | A long and healthy life for all through equitable access to prevention and control of NCDs. To provide integrated, people-centred interventions, to promote health and wellness, prevention and control for South Africa through a strengthened national response to reduce avoidable and premature NCDs+ morbidity, disability and mortality with the framework of the Sustainable Development Goals. | Yes | No | No | No | No | Some | 13 |

Based on 2022 fiscal year classifications by the World Bank https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

Document translated from national language to English.

MSK refers to MSK conditions, mobility/functional impairment, persistent non-cancer MSK pain or injury/trauma.

Figure 2.

Frequency map of, by country, stated foci across policies for non-communicable diseases (left panel) and other included acute and chronic health conditions (right panel)

Across all the policies, one or more of the proposed objectives and/or strategies for the target NCDs also had relevance to prevention or management of MSK health impairment from a HSS perspective: all strategies were relevant in five (41.7%) polices and some were relevant in seven (58.3%) policies. The mean (SD) internal validity score across the policies of 10.3 (2.6) highlights overall high-quality policies based on the assessment criteria.

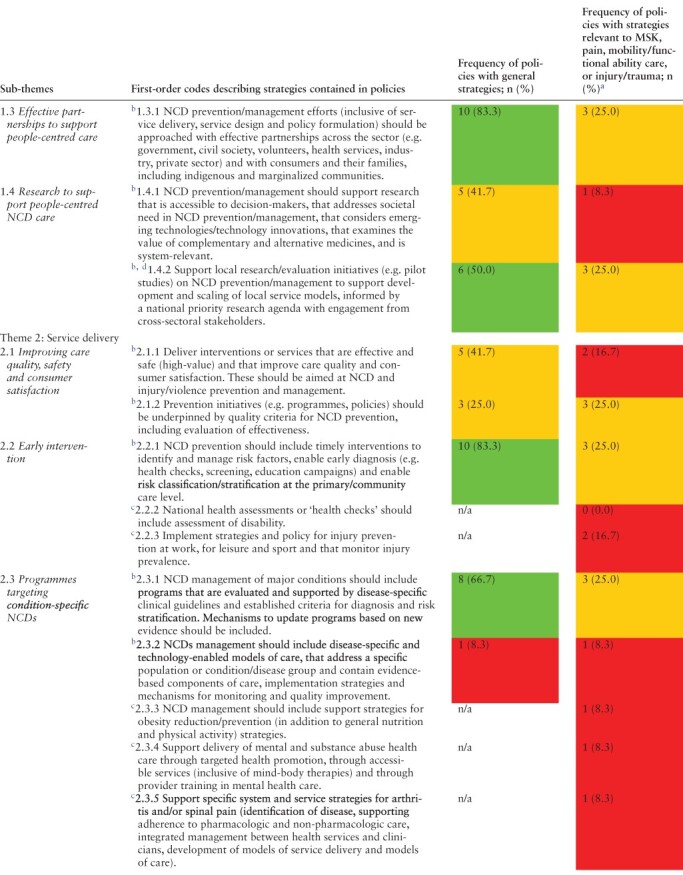

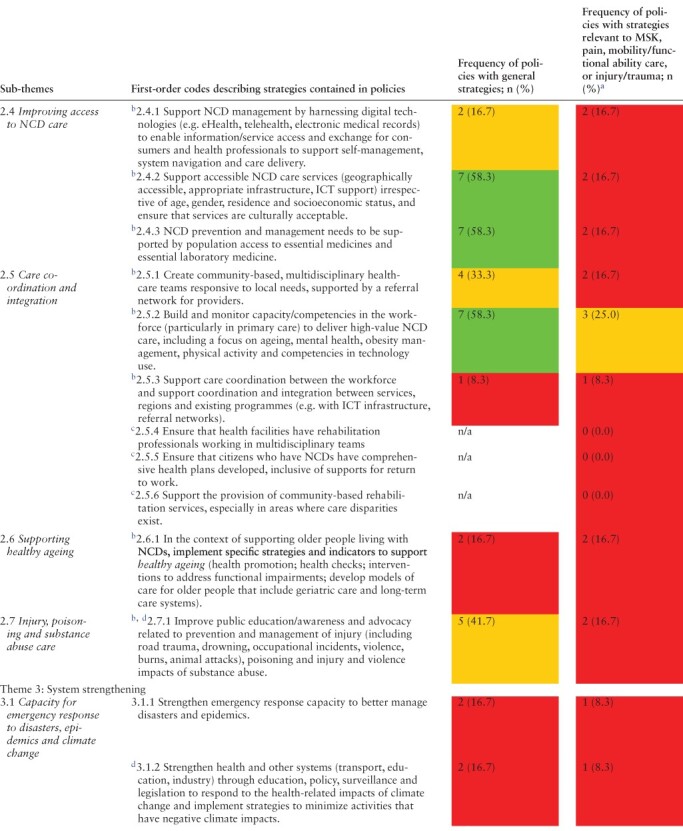

Strategies to achieve the aims stated across the policies were coded against a framework of three overarching themes: (1) general principles for people-centred NCD care, (2) service delivery and (3) system strengthening, underpinned with 45 first-order codes [three new codes were added to the base coding framework of 42 codes (Briggs et al., 2019b) to describe general NCD prevention/control strategies] (Table 3). Across the 33 codes describing general prevention/control strategies for NCDs, 31 (93.9%) had some relevance to MSK health (3.1.1 and 3.2.2 were not considered relevant).

Table 3.

Summary of overarching themes, supported by sub-themes and first-order codes to describe the scope and content of the strategies outlined in the included health policies for LMICs (n = 12). Frequencies of general strategies for prevention/control of NCDs and frequencies of specific strategies relevant to musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions, pain, mobility/functional ability, or injury/trauma, by policy, are included to provide a measure of prominence for first-order codes. Frequencies, expressed as n(%), are colour coded for ease of interpretation (red <25%; amber ≥25% to <50%; green ≥50%)

|

|

|

|

Analysis based on 4 policies that reported some focus on MSK health (Ministerio De Salud, Argentina, 2009; Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, 2017b; Ministério Da Saúde Brasília, 2021; Ministry of Health, Republic of Kenya, 2021).

General NCD prevention or control strategies relevant to the prevention/control of musculoskeletal health conditions; persistent non-cancer MSK pain; loss of functional ability/mobility; or injury/trauma, derived previously (Briggs et al., 2019b).

Additional MSK-specific strategies, derived previously (Briggs et al., 2019b).

New code derived from data in the current study to reflect general NCD prevention/control strategies identified among policies from LMICs.

ICT: information and communication technologies; MSK: musculoskeletal; n/a: not applicable; NCD: noncommunicable disease.

Theme 1: general principles for people-centred NCD care

Policies frequently identified a need for promoting safe work/school, living and transport environments to reduce exposure to environmental risk factors associated with NCDs (e.g. air pollutants and other toxins/chemical exposure), injury (work, road trauma and interpersonal violence) and health sequelae of climate change. Multifaceted strategies to support an increase in population-level physical activity (PA) (including in school contexts); promotion of healthy behaviours (nutrition, limiting alcohol and tobacco use, PA and mental well-being) in community, workplace and schools and public health education were frequently cited as important strategies for prevention and control of NCDs. Cross-sectoral partnerships and research that is accessible and meaningful to decision-makers and supports local need were also advocated as system reform enablers.

Theme 2: service delivery

Policies frequently cited the need for access to early screening, diagnosis and intervention within primary/community care settings. For NCD-specific care, evidence-based programmes to manage major NCDs were recommended. Concerning service access, the importance of population access to essential medicines, laboratory services and NCD services (irrespective of age, gender, geography and socioeconomic status) was frequently cited. Workforce capacity development (capabilities, volumes and outreach services) in primary/community care settings was advocated to improve care access, coordination and integration. Policies also identified a need for public education and awareness related to prevention and management of injury (including road trauma, drowning, occupational incidents, violence, burns and animal attacks), poisoning and injury and violence sequelae of substance abuse.

Theme 3: system strengthening

Population-level health surveillance; innovative revenue and financing models (e.g. funding reallocation) that support access to care without incurring excessive health expenditure for the most vulnerable; health governance responses through policy formulation, implementation and monitoring; and establishment of regulation standards to address unhelpful commercial influences on population health behaviours were strongly identified as important strategies across LMIC policies. Some LMIC policies also identified the need for strengthening systems of non-health sectors (e.g. transport, education and industry) to respond to the health impacts of climate change.

Among the four policies that expressed some inclusion of MSK health (Ministerio De Salud, Argentina, 2009; Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, 2017b; Ministério Da Saúde Brasília, 2021; Ministry of Health, Republic of Kenya, 2021), general NCD care strategies were commonly applied to the MSK health components of the policies (e.g. safe environments, promoting healthy behaviours and public health education). Among the MSK-specific codes previously derived (Briggs et al., 2019b), policy and strategies for prevention and management of injury (occupational, road trauma and violence), obesity, mental health and substance abuse, osteoarthritis and spinal pain were identified. Creation of guidelines and standards to support care, and social and financial support for people living with disability, were also cited (Table 3).

Discussion

Main findings

Health systems in LMICs are constrained in their capacity to respond to the current and projected burden of MSK health impairments beyond MSK injury and trauma. Limited financial, human and health infrastructure resourcing and performance targets of the SDGs contribute to a selective HSS focus on CMNNDs and NCDs associated with premature mortality and injury and trauma. Despite an identified need to address MSK health and MSK rehabilitation needs in LMICs (Sharma et al., 2019; Foster et al., 2020; Vos et al., 2020; Cieza et al., 2021; Briggs et al., 2021a), key rate-limiting factors include frequent political instability; an absence of MSK-specific policy responses; inadequate reliable local health surveillance data on MSK health impairment, prevalence and impact; and limited population awareness of MSK health on a background of prevailing sociocultural attitudes. Global health estimates suggest that this burden-system response gap for LMICs will likely accelerate with higher rates of ageing, risk factor prevalence for NCDs (such as obesity and reduced PA) and road traffic trauma compared with high-income nations (Jackson et al., 2015; 2016; Briggs et al., 2018b; Blyth et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2019; Cordero et al., 2020; Vos et al., 2020; Cieza et al., 2021). Our results from secondary analysis of qualitative data specific to LMICs, contextualized through analysis of health policies for integrated NCD care, highlight these challenges, yet critically, signal opportunities for targeted HSS initiatives that can benefit MSK health in LMICs.

Internationally, health policy responses for MSK health are typically observed in high-income nations. For example, in an analysis of health policies from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Member States, 50% of the countries had NCD policies that explicitly included MSK health (Briggs et al., 2019b). In contrast, among the integrated NCD policies evaluated in the current study, none documented an explicit focus on MSK health and only four considered MSK health peripherally, primarily focusing on injury and trauma. Despite the void of health policy responses to chronic MSK conditions, the policy responses aligned with prevention and management of injury and trauma attributed to road traffic accidents, occupational accidents and interpersonal violence, likely reflecting the sustained global health advocacy in injury and trauma care in LMICs and a stronger emphasis on minimizing premature mortality (Peden, 2005; Mock et al., 2008; Spiegel et al., 2008; Lagrone et al., 2016). For NCD care unrelated to injury, we identified policy strategies that could create critical system and service capabilities to support MSK health responses. Integrating MSK care with prevention and control of NCDs more broadly, and in some contexts injury and trauma (e.g. in revenue models for financing rehabilitation for MSK impairments), appears a rational, sustainable and appropriate response. Importantly, this is consistent with the principles of development effectiveness, where integration with existing systems and infrastructure is preferred over establishing new systems in low-resource settings (Hoy et al., 2014; Briggs et al., 2020). Realization of these potential opportunities requires greater public and political awareness and advocacy within LMICs and civil society, applying observations and learning from how the ‘big 4 NCDs’ have been prioritized for global action (Heller et al., 2019) and principles for raising awareness of global health issues (Shiffman and Smith, 2007).

Health systems strengthening in LMIC contexts

From Part 1 of this study, we identified unique LMIC context–specific perspectives on challenges and opportunities for HSS in MSK health, as distinct to the global perspective (Briggs et al., 2021a; 2021b). In particular, the healthcare landscape in LMICs was characterized by the competing priorities of CMNNDs, NCDs and injury. These factors collectively limit the capacity of LMICs to respond to the MSK-attributed morbidity burden. Unique system capacity challenges were related to political instability; inadequate revenue and finance allocations for MSK health (creating potentially catastrophic health expenditure for the most vulnerable, including inadequate access to essential medicines); and health infrastructure constraints for primary/community-based screening and service models, rehabilitation and non-trauma surgical care.

To facilitate reliable and credible data-driven advocacy efforts, KIs expressed the need for building national capacity to monitor population health, including MSK impairment prevalence and impact. Surveillance capability is relevant to LMIC local contexts and to improving global health estimates, since for many LMICs, local data are not available (Ferreira et al., 2021; Tamrakar et al., 2021). LMIC system constraints viewed through social determinants of MSK health frame highlight critical factors such as the need to continue working (despite MSK impairment) and manage care inequalities imposed by geography or by the need to travel long distances to access MSK care. Varying beliefs, expectations and prevailing sociocultural attitudes about MSK health, chronic MSK pain and disability across countries, including LMICs (Ferreira-Valente et al., 2019; Sharma and Ferreira-Valente et al., 2020), also impact HSS opportunities. While this issue was identified in this LMIC-focused secondary analysis, it resonates with minority groups from high-income nations where MSK care inequities are also pronounced (Hogg et al., 2012; Lewis and Upsdell, 2018; Lin et al., 2018; Morales and Yong, 2021). Compared with global perspectives, KIs from LMICs placed greater emphasis on the need for community-based screening and early intervention in children to minimize long-term disability and loss of human capital into adulthood. This finding aligns with evidence for strengthening primary care systems with benefits for child health outcomes (Witter et al., 2019; Foster et al., 2020), e.g. in childhood arthritis in LMICs (Consolaro et al., 2019). These context-specific issues highlight the need for inclusion of LMICs representatives in co-developing global health strategies to ensure their adaptability to suit local LMIC contexts.

NCD health policy context in LMICs and triangulation with qualitative data

Findings from the policy content analysis resonated with those from the secondary qualitative analysis, where KIs’ perspectives reflected the current policy landscape in their specific LMIC settings. Most health policies referred to the need for strengthening financing models and governance through health policy and regulation. However, these areas were articulated in the context of NCD care generally, indicating opportunities for integration of MSK care within broader NCD reform efforts. Health policies outlined strategies to strengthen primary and community-based NCD care to make services accessible and affordable to overcome health inequities. Strategies included building community-based capacity for early screening, diagnosis, early intervention and access to essential medicines and laboratory services, and adopting innovative financing approaches such as revenue reallocation. Given the limited global development assistance for health in NCDs (Jailobaeva et al., 2021), innovative finance models will be especially important. These policy foci align with KIs’ perspectives and with global primary care reform priorities and evidence for HSS initiatives in LMICs (Kluge et al., 2018; World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef), 2018; Witter et al., 2019).

We observed important differences in strategic priorities compared with health policy data from high-income nations, such as Member States of the OECD (Briggs et al., 2019b). Policies from LMICs more strongly focused on environment (safe environments, acting on environmental toxins and pollutants and acting on health sequelae of climate change), access (early screening/intervention, especially for child health and access to essential medicines), injury and trauma care (advocacy, prevention, management and surveillance systems to address road traffic, occupational and interpersonal violence-related injury), local service models (supporting evaluation and scale-up of service models) and system-level foci (health financing mechanisms to minimize catastrophic personal health expenditure, social and health policy formulation and regulation to address unhelpful commercial influence and marketing). Many of these policy themes are similarly reported in a recent synthesis of diabetes and hypertension models of care in LMICs (Lall et al., 2018). While digital technologies and infrastructure were previously highlighted as priorities in policies among OECD Member States and are recommended as a system strengthening opportunity in WHO guidelines (Briggs et al., 2019b; WHO, 2019b), an emphasis on leveraging digital technologies was not observed in policies of the selected LMICs. This observation is consistent with aligned research where investment in digital infrastructure was deprioritized (Briggs and Araujo De Carvalho, 2018a) and there is little evidence to support investment in health information systems in LMICs to improve health outcomes (Witter et al., 2019) and the debate about telehealth technologies bridging or widening care-inequity gaps in LMICs (Reis et al., 2021).

Opportunities for building capacity in LMICs to address pain and disability through action on MSK health

Findings from the current study point to specific opportunities and priorities in LMICs (Box 1). Critically, these empirically derived opportunities and priorities align with evidence for HSS in LMICs, as identified recently (Witter et al., 2019). Specific target domains include leadership and governance, financing and service models.

Box 1.

Opportunities and priorities for health systems strengthening in low- and middle-income countries for musculoskeletal health.

Engage, empower and educate communities and governments of LIMCs: focus on costs attributed to lost participation and health loss in children. Here, public health messaging should include prevention opportunities and the relevance of current global NCD-focused public health initiatives to MSK care (e.g. WHO ‘Best Buys’ and ‘Package of Essential Non-communicable Disease Interventions for Primary Health Care in Low-Resource Settings’ (World Health Organization, 2010; 2017)).

Governance: integrate MSK health as the priority area within current and emerging national NCD and injury and trauma rehabilitation policy. Policy evolution may also be informed by learning from the prioritization of other NCDs in the global health agenda and the framework suggested by Shiffman and Smith for advocacy and prioritization of health issues at a global level (Shiffman and Smith, 2007; Heller et al., 2019).

Build capacity in existing LMIC service models: extend current service models for NCD and injury care to include MSK health conditions more broadly, with a focus on early screening and intervention in primary care, particularly for children. Furthermore, supporting locally adapted implementation of emerging global opportunities that are MSK-relevant, including the WHO Package of Interventions for Rehabiliation for MSK conditions (Rauch et al., 2019), the WHO Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE) service model (WHO 2019a) and WHO Guidelines on chronic primary low back pain, will help to build service-level and workforce capacity in MSK healthcare delivery.

Financing: create sustainable revenue streams for NCD and injury care in LMICs that include MSK care to ensure care accessibility and access to essential medicines, laboratory services and rehabilitative therapies. Innovative financing solutions such as taxation and redistribution strategies will be important, supported by evidence for cost-effectiveness and health benefit (Kaur et al., 2019).

Surveillance: build secure infrastructure and systems to collect population-level MSK impairment prevalence and impact data in LMICs. A greater representation of MSK epidemiology studies from LMICs in regional and global health journals, measurement of MSK health in intrinsic capacity assessment for healthy ageing (Veronese et al., 2022) and monitoring of MSK health as part of the WHO NCD Country Capacity Surveys would facilitate surveillance efforts.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this research is the first study to examine HSS challenges and opportunities in MSK health for select LMICs. We applied rigorous, best-practice and established methods to each part of the research (Adebiyi et al., 2019; Ruggiano and Perry, 2019). Our sample was modest for KIs and policies and therefore the scope of LMICs included, and thus, we cannot speculate whether our results are transferable to other LMICs. Although we identified consistency in themes in analysis of the qualitative (part 1) data, other evidence may arise in the context of a primary study and/or inclusion of KIs from other LMICs and/or sampling categories. Nonetheless, we achieved representation across LMIC economies and regions to provide novel, contemporary insights. Our methods provide a framework to extend the research to evaluate context and policy across other LMICs, to further validate our results and to explore differences across a larger sample. Expansion of the research to include other LMICs will be important to improve the transferability of findings and targets for HSS interventions. Our policy focus was limited to integrated prevention and control of NCDs, and quality appraisals suggested high-quality polices. We cannot speculate on policy strategies across sectors such as occupational health, public health and focused injury and trauma, and population groups such as youth and ageing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the input from participants in the parent study and guidance provided from the external advisory group convened by the Global Alliance for Musculoskeletal Health (G-MUSC), including Kristina Åkesson, Neil Betteridge, Karsten Dreinhöfer and Anthony Woolf (chair). The authors acknowledge that the role of G-MUSC is auspicing the parent study.

Contributor Information

Andrew M Briggs, Curtin School of Allied Health and Curtin enAble Institute, Faculty of Health Sciences, Curtin University, Kent Street, Bentley, Western Australia 6102, Australia; Global Alliance for Musculoskeletal Health (G-MUSC), Institute of Bone and Joint Research, Kolling Institute, University of Sydney, 10 Westbourne Street, St Leonards, New South Wales 2064, Australia.

Joanne E Jordan, HealthSense (Aust) Pty Ltd, Malvern East, Victoria 3145, Australia.

Saurab Sharma, Department of Physiotherapy, Kathmandu University School of Medical Sciences, Dhulikhel 45200, Nepal; School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of New South Wales, 18 High St Kensington, New South Wales 2052, Australia; Centre for Pain IMPACT, Neuroscience Research Australia, 139 Barker Street, Randwick, New South Wales 2031, Australia.

James J Young, Department of Research, Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College, 6100 Leslie Street, North York, Ontario M2H 3J1, Canada; Center for Muscle and Joint Health, Department of Sports Science and Clinical Biomechanics, University of Southern Denmark, 5230 Odense, Denmark.

Jason Chua, TBI Network, Faculty of Health and Environmental Sciences, Auckland University of Technology, 55 Wellesley Street East, Auckland CBD, Auckland 1010, New Zealand.

Helen E Foster, Population Health Institute, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 4AX, United Kingdom; Paediatric Global Musculoskeletal Task Force, Global Alliance for Musculoskeletal Health, Institute of Bone and Joint Research, Kolling Institute, University of Sydney, 10 Westbourne Street, St Leonards, New South Wales 2064, Australia.

Syed Atiqul Haq, Rheumatology Department, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Dhaka 1000, Bangladesh; Asia Pacific League of Associations for Rheumatology (APLAR), 1 Scotts Road #24-10, Shaw Center Singapore 228208, Singapore.

Carmen Huckel Schneider, Menzies Centre for Health Policy and Economics, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, 17 John Hopkins Drive, Camperdown, New South Wales 2050, Australia.

Anil Jain, Department of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, Santokba Durlabhji Memorial Hospital, Bhawani Singh Marg Road, Rambagh Circle 302015, Jaipur, India.

Manjul Joshipura, AO Alliance Foundation, Clavadelerstrasse 8, Davos Platz 7270, Switzerland.

Asgar Ali Kalla, Department of Medicine, University of Cape Town, Anzio Road, Observatory, Cape Town 7925, South Africa.

Deborah Kopansky-Giles, Global Alliance for Musculoskeletal Health (G-MUSC), Institute of Bone and Joint Research, Kolling Institute, University of Sydney, 10 Westbourne Street, St Leonards, New South Wales 2064, Australia; Department of Research, Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College, 6100 Leslie Street, North York, Ontario M2H 3J1, Canada; Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto, 500 University Ave, Toronto, ON M5G 1V7, Canada.

Lyn March, Global Alliance for Musculoskeletal Health (G-MUSC), Institute of Bone and Joint Research, Kolling Institute, University of Sydney, 10 Westbourne Street, St Leonards, New South Wales 2064, Australia; Florance and Cope Professorial Department of Rheumatology, Royal North Shore Hospital, Reserve Rd, St Leonards NSW 2065, Australia; Kolling Institute, University of Sydney, 10 Westbourne Street, St Leonards, New South Wales 2064, Australia.

Felipe J J Reis, Physical Therapy Department, Instituto Federal do Rio de Janeiro (IFRJ), R. Sen. Furtado, 121/125 - Maracanã, Rio de Janeiro – RJ, 20270-021, Brazil; Clinical Medicine Department, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro – RJ, 21044-020, Brazil; Pain in Motion Research Group, Department of Physiotherapy, Human Physiology and Anatomy, Faculty of Physical Education & Physiotherapy, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Bd de la Plaine 2, Ixelles 1050, Brussels, Belgium.

Katherine Ann V Reyes, Alliance for Improving Health Outcomes, Inc., West Ave, Quezon City 1104, Philippines; School of Public Health, Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila, Intramuros, Manila, 1002 Metro, Manila, Philippines.

Enrique R Soriano, Rheumatology Unit, Internal Medicine Services and University Institute, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Tte. Gral. Juan Domingo Perón 4190, C1199 CABA, Buenos Aires, Argentina; Pan-American League of Associations for Rheumatology (PANLAR), Wells Fargo Plaza, 333 SE 2nd Avenue Suite 2000 Mia, Florida 33131, United States of America.

Helen Slater, Curtin School of Allied Health and Curtin enAble Institute, Faculty of Health Sciences, Curtin University, Kent Street, Bentley, Western Australia 6102, Australia.

Abbreviations

CMNNDs: Communicable, maternal, neonatal and nutritional diseases

COREQ-32: COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research checklist

GBD: Global burden of disease

GRIPP2-sf: Guidance for reporting patients and the public short form

HSS: Health system strengthening

G-MUSC: Global Alliance for Musculoskeletal Health

ICT: Information and Communication Technology

LMIC: Low- and middle-income country

MSK: Musculoskeletal

NCD: Non-communicable disease

OECD: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

PPI: Patient and public involvement

PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

SDG(s): Sustainable Development Goal(s)

WHO: World Health Organization

Supplementary data

Supplementary data is available at HEAPOL Journal online.

Funding

This research was funded by research grants awarded by the Bone and Joint Decade Foundation (Sweden), grant number: not applicable; Curtin University (Australia), grant number: not applicable; Institute of Bone and Joint Research, Royal North Shore Hospital (Australia), grant number: not applicable; and Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College (Canada), grant number: not applicable.

Ethical approval

The Human Research Ethics Committee of Curtin University, Australia (HRE2020-0183), approved this research, including secondary analysis of qualitative data.

Conflict of interest statement

Dr. Briggs reports grants from the Bone and Joint Decade Foundation; grants from Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College; grants from the Institute for Bone and Joint Research, Royal North Shore Hospital, NSW, Australia; grants from Curtin University, during the conduct of the study, and personal fees from World Health Organization, outside the submitted work.

Dr. Jordan reports personal fees from Curtin University, during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Sharma reports personal fees from Curtin University, during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Young reports grants from the Danish Foundation for Chiropractic Research and Post-graduate Education; grants from Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College; grants from the Ontario Chiropractic Association; grants from the National Chiropractic Mutual Insurance Company Foundation; grants from the University of Southern Denmark Faculty Scholarship and personal fees from Curtin University, outside the submitted work.

Dr. Foster is the Chair of the Paediatric Global MSK Task Force.

Dr. Haq has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Jain has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Joshipura has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Kalla has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Kopansky-Giles reports grants from Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College, during the conduct of the study.

Dr. March reports personal fees from Lilly Pty Ltd, personal fees from Pfizer Ltd, personal fees from AbbVie Pty Ltd and grants from Janssen Pty Ltd, outside the submitted work; Dr March is an Executive member of OMERACT that receives funding from 30 different companies.

Dr. Reis has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Reyes has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Soriano reports grants, personal fees and non-financial support from AbbVie; personal fees from Amgen; personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb Pharmaceuticals (BMS); grants from Glaxo; grants and personal fees from Janssen; personal fees from Lilly; grants and personal fees from Novartis; grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Pfizer; grants and personal fees from Roche; and grants, personal fees and non-financial support from UCB, outside the submitted work.

Dr. Chua reports personal fees from Curtin University, during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Huckel Schneider reports grants from Curtin University, during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Slater reports grants from Bone and Joint Decade Foundation; grants from Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College; grants from Institute for Bone and Joint Research, Royal North Shore Hospital, NSW, Australia; and grants from Curtin University, during the conduct of the study.

Reflexivity statement

The authorship team intentionally reflects diversity and inclusion in gender (seven females and ten males), clinical disciplines (chiropractic, orthopaedic and trauma surgery, rehabilitation medicine, rheumatology and paediatric rheumatology, physiotherapy and public health) and health policy expertise. The authors represent the regions of East Asia and the Pacific (eight authors), Europe and Central Asia (two authors), Latin America and the Caribbean (two authors), North America (two authors), South Asia (four authors) and Sub-Saharan Africa (one author). Critically, seven authors are resident in LMICs, thereby bringing contemporary context and interpretations to the author team. Three early post-doctoral scholars are co-authors in an effort to support capacity-building in this research field.

Author contribution statement

Conception or design of the work: Briggs, Jordan, Sharma, Kopansky-Giles, March, Slater.

Data collection: Briggs, Jordan, Sharma, Young, Slater.

Data analysis and interpretation: Briggs, Jordan, Sharma, Young, Slater.

Drafting the article: Briggs, Jordan, Sharma, Young, Chua, Slater.

Critical revision of the article: Briggs, Jordan, Sharma, Young, Chua, Foster, Haq, Huckel Schneider, Jain, Joshipura, Kalla, Kopansky-Giles, March, Reis, Reyes, Soriano, Slater.

Final approval of the version to be submitted: Briggs, Jordan, Sharma, Young, Chua, Foster, Haq, Huckel Schneider, Jain, Joshipura, Kalla, Kopansky-Giles, March, Reis, Reyes, Soriano, Slater.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

References

- Adebiyi BO, Mukumbang FC, Beytell AM. 2019. To what extent is fetal alcohol spectrum disorder considered in policy-related documents in South Africa? A document review. Health Research Policy and Systems 17: 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blyth FM, Briggs AM, Huckel Schneider C, Hoy DG, March LM. 2019. The global burden of musculoskeletal pain - where to from here? American Journal of Public Health 109: 35–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan-Olsen SL, Cook S, Leech MT et al. 2017. Prevalence of arthritis according to age, sex and socioeconomic status in six low and middle income countries: analysis of data from the World Health Organization study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE) Wave 1. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 18: 271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs AM, Araujo De Carvalho I. 2018a. Actions required to implement integrated care for older people in the community using the World Health Organization’s ICOPE approach: a global Delphi consensus study. PLoS One 13: e0205533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs AM, Houlding E, Hinman RS et al. 2019a. Health professionals and students encounter multi-level barriers to implementing high-value osteoarthritis care: a multi-national study. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 27: 788–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs AM, Huckel Schneider C, Slater H et al. 2021a. Health systems strengthening to arrest the global disability burden: empirical development of prioritised components for a global strategy for improving musculoskeletal health. BMJ Global Health 6: e006045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs AM, Jordan JE, Kopansky-Giles D et al. 2021b. The need for adaptable global guidance in health systems strengthening for musculoskeletal health: a qualitative study of international key informants. Global Health Research and Policy 6: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs AM, Persaud JG, Deverell ML et al. 2019b. Integrated prevention and management of non-communicable diseases, including musculoskeletal health: a systematic policy analysis among OECD countries. BMJ Global Health 4: e001806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs AM, Shiffman J, Shawar YR et al. 2020. Global health policy in the 21st century: Challenges and opportunities to arrest the global disability burden from musculoskeletal health conditions. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology 34: 101549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs AM, Slater H, Jordan JE et al. 2021c. Towards a Global Strategy to Improve Musculoskeletal Health. Sydney: Global Alliance for Musculoskeletal Health (G-MUSC). [Google Scholar]

- Briggs AM, Woolf AD, Dreinhoefer KE et al. 2018b. Reducing the global burden of musculoskeletal conditions. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 96: 366–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukhman G, Mocumbi AO, Atun R et al. 2020. The Lancet NCDI Poverty Commission: bridging a gap in universal health coverage for the poorest billion. The Lancet 396: 991–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Kuhn M, Prettner K, Bloom DE. 2019. The global macroeconomic burden of road injuries: estimates and projections for 166 countries. The Lancet Planetary Health 3: e390–e98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieza A, Causey K, Kamenov K et al. 2021. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the Global Burden of Disease study 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 396: 2006–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consolaro A, Giancane G, Alongi A et al. 2019. Phenotypic variability and disparities in treatment and outcomes of childhood arthritis throughout the world: an observational cohort study. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 3: 255–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero DM, Miclau TA, Paul AV et al. 2020. The global burden of musculoskeletal injury in low and lower-middle income countries: a systematic literature review. OTA International: The Open Access Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma 3: e062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham M, Wells M. 2017. Qualitative analysis of 6961 free-text comments from the first National Cancer Patient Experience Survey in Scotland. BMJ Open 7: e015726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalglish SL, Khalid H, Mcmahon SA. 2021. Document analysis in health policy research: the READ approach. Health Policy and Planning 35: 1424–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health, Philippines . 2016. Philippine Multisectoral Strategic Plan for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases 2017–2025. Manila, Philippines: Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira GE, Buchbinder R, Zadro JR et al. 2021. Are musculoskeletal conditions neglected in national health surveys? Rheumatology (Oxford) 60: 4874–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira-Valente A, Sharma S, Torres S et al. 2019. Does religiosity/spirituality play a role in function, pain-related beliefs, and coping in patients with chronic pain? A systematic review. Journal of Religion and Health 61: 2331–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster HE, Scott C, Tiderius CJ, Dobbs MB. 2020. Improving musculoskeletal health for children and young people – a ‘call to action’. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology 34: 101566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2019 Demographics Collaborators . 2020. Global age-sex-specific fertility, mortality, healthy life expectancy (HALE), and population estimates in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2019: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 396: 1160–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller O, Somerville C, Suggs LS et al. 2019. The process of prioritization of non-communicable diseases in the global health policy arena. Health Policy and Planning 34: 370–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds PS, Vogel RJ, Clarke-Steffen L. 1997. The possibilities and pitfalls of doing a secondary analysis of a qualitative data set. Qualitative Health Research 7: 408–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg MN, Gibson S, Helou A, Degabriele J, Farrell MJ. 2012. Waiting in pain: a systematic investigation into the provision of persistent pain services in Australia. Medical Journal of Australia 196: 386–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoy D, Geere J-A, Davatchi F, Meggitt B, Barrero LH. 2014. A time for action: opportunities for preventing the growing burden and disability from musculoskeletal conditions in low- and middle-income countries. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology 28: 377–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. 2005. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15: 1277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson T, Thomas S, Stabile V et al. 2015. Prevalence of chronic pain in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet 385: S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson T, Thomas S, Stabile V et al. 2016. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the global burden of chronic pain without clear etiology in low and middle-income countries: trends in heterogeneous data and a proposal for new assessment methods. Anesthesia and Analgesia 123: 739–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jailobaeva K, Falconer J, Loffreda G et al. 2021. An analysis of policy and funding priorities of global actors regarding noncommunicable disease in low- and middle-income countries. Globalization and Health 17: 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]