ABSTRACT

Introduction:

A timely diagnosis of osteoporosis is key to reducing its growing clinical and economic burden. Radiofrequency Echographic Multi Spectrometry (REMS), a new diagnostic technology using an ultrasound approach, has been recognized by scientific associations as a facilitator of patients’ care pathway. We aimed at evaluating the costs of REMS vs. the conventional ionizing technology (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, DXA) for the diagnosis of osteoporosis from the perspective of the Italian National Health Service (NHS) using a cost-minimization analysis (CMA).

Methods:

We carried out structured qualitative interviews and a structured expert elicitation exercise to estimate healthcare resource consumption with a purposeful sample of clinical experts. For the elicitation exercise, an Excel tool was developed and, for each parameter, experts were asked to provide the lowest, highest and most likely value. Estimates provided by experts were averaged with equal weights. Unit costs were retrieved using different public sources.

Results:

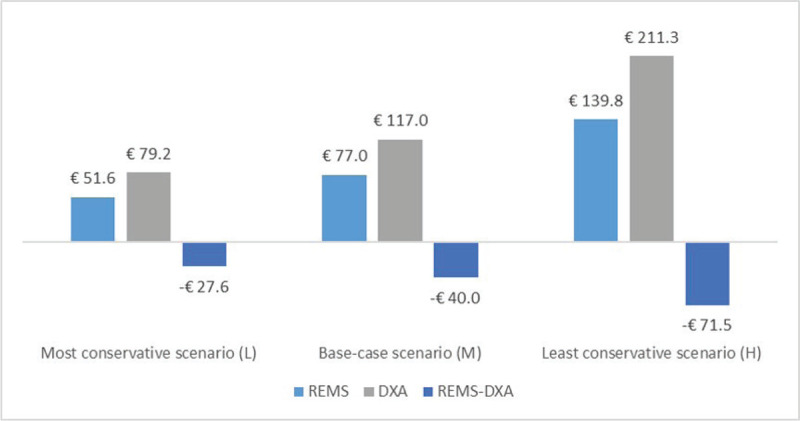

Considering the base-case scenario (most likely value), the cost of professionals amounts to €31.9 for REMS and €48.8 for DXA, the cost of instrumental examinations and laboratory tests to €45.1 for REMS and €68.2 for DXA. Overall, in terms of current costs, REMS is associated with a mean saving for the NHS of €40.0 (range: €27.6-71.5) for each patient.

Conclusions:

REMS is associated with lower direct healthcare costs with respect to DXA. These results may inform policy-makers on the value of the REMS technology in the earlier diagnosis for osteoporosis, and support their decision regarding the reimbursement and diffusion of the technology in the Italian NHS.

Keywords: Cost-minimization analysis, Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA), Economic evaluation, Health Technology Assessment (HTA), Osteoporosis, Radiofrequency Echographic Multi Spectrometry (REMS)

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a systemic disease of the skeletal system, characterized by the deterioration of the density and quality of bone tissue, with a consequent increase in bone fragility and the risk of fracture (1). As people age, bone mass declines and the risk of fragility fractures increases (2). Prevalence of osteoporosis is increasing steadily (3), with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 18.3% (4). In Italy, it is estimated that approximately 3.2 million women and 0.8 million men suffer from osteoporosis, with a higher prevalence in the over 50 age group (5). Osteoporosis represents a relevant and growing public health problem, being a widespread and costly disease that generates a significant burden in terms of disability and impaired quality of life (6). In Italy, fragility fractures are associated with the loss of more than 500,000 healthy life years, ranking fourth among the most serious diseases (7). In addition, the direct health costs associated with fragility fractures amount to approximately 10 billion euros, with significant productivity losses (94 sick leave days/year for 1,000 individuals) (7). Thanks to significant advances in disease management over the last years, osteoporosis is now eminently treatable and the associated fragility fractures preventable (8,9). However, osteoporosis still remains both an underdiagnosed and undertreated disease (10-12). The International Osteoporosis Foundation revealed that restricted access to diagnosis before the first fracture is one of the main causes of osteoporosis underdiagnosis and undertreatment (13). Therefore, identifying patients at risk and making a timely diagnosis are key factors to help reduce the risk of fragility fractures and therefore the burden of the disease (14).

The diagnosis of osteoporosis is based on the assessment of bone mineral density or the anamnesis of femoral or vertebral fractures in adulthood in the absence of major trauma (15). To date, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) at the level of the lumbar spine and proximal femur represents the conventional technology for the diagnosis of osteoporosis (16). Despite the high accuracy of DXA, there are some factors that hinder its adequacy for mass screening, including the cost of the technology, the use of radiations and, in some cases, its limited accessibility (due to a limited number of densitometers, lack of qualified healthcare personnel to correctly perform the exam and/or absence of reimbursement in some countries) (17-19). Overall, this may limit the ability of the health system of timely diagnosing osteoporosis, with a negative impact on fracture prevention. Recently, a new technology that performs the analysis of bone quantity and quality through an ultrasound, non-ionizing approach, called Radiofrequency Echographic Multi Spectrometry (REMS), has been developed for the diagnosis of osteoporosis (20,21). The use of REMS technology for the diagnosis of osteoporosis has been clinically validated by several single-center and multicenter studies, which have shown that REMS has a precision and diagnostic accuracy at least comparable to that of DXA (18,20-23) in several patient populations, including postmenopausal women (18) and female patients aged between 30 and 90 years (22,23). Moreover, an Italian multicenter prospective observational study found that, for the vertebral site, REMS has a greater ability than DXA to identify true positives (i.e., osteoporotic patients who suffered an incident fragility fracture during follow-up) and a similar ability to identify true negatives (i.e., healthy patients who did not have fractures during follow-up), while for the femoral site the predictive ability is similar between REMS and DXA (22). Through its consensus paper published in 2019, the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases has established that REMS represents a valid approach for mass population screening, early diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring (19). In fact, the REMS approach presents some advantages including the absence of radiation, the easy portability of the device and its lower cost (17). In 2021, the Italian Inter-Society Health Ministry Guidelines developed by the Italian National Institute of Health – Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS) – for the “Diagnosis, risk stratification and continuity of care for Fragility Fractures” recognized the REMS ultrasound examination as a diagnostic technology that can facilitate the patients’ care pathway (24).

To complement the current evidence on the clinical value of REMS, the objective of this study was to evaluate the costs associated with the use of the REMS approach for the diagnosis of osteoporosis compared to DXA from the perspective of the Italian National Health Service (NHS) using a cost-minimization analysis (CMA), based on the assumption that the two approaches have comparable diagnostic precision and accuracy and therefore guarantee equivalent health outcomes.

Methods

We performed structured, individual qualitative interviews with a selected sample of clinicians (n = 6) who are recognized experts in the diagnosis and management of patients with osteoporosis and in the use of the REMS technology (e.g., authors of peer-reviewed publications on REMS). The interview guide is reported as Supplementary file 1. Clinicians were selected through a purposive sampling to reflect current practice across different specialties (namely radiology, gynecology, internal medicine, orthopedics and traumatology, endocrinology and rheumatology) and Italian regions (Lombardia, Veneto, Emilia Romagna, Toscana, Lazio, Puglia). The interviews had the objective of: (i) understanding the current and future use of REMS (being a technology recently introduced in the Italian NHS); (ii) gathering qualitative information on the diagnostic pathway and follow-up of osteoporotic patients; (iii) identifying the target population of REMS and DXA; (iv) identifying the types of healthcare resources consumed (e.g., outpatient visits, laboratory tests, healthcare personnel involved) for the diagnosis of osteoporosis. Information collected through qualitative interviews, especially regarding points (iii) and (iv), was used to develop the CMA model.

An initial review of the literature revealed that resource consumption data for both DXA and REMS in Italy are scant. Therefore, we performed a structured expert elicitation exercise in order to collect quantitative estimates of healthcare resource consumption. Structured expert elicitation is the process by which the beliefs of experts about unknown quantities or parameters can be formally collected in a quantitative manner (25,26). Expert elicitation is a useful approach when evidence is missing, is not well developed or limited (27). Expert elicitation is increasingly recognized as a valuable method for informing healthcare decision-making as it allows to quantify parameter uncertainty and take it into account within an economic evaluation model (28). Clinical experts involved in the qualitative interviews and other clinicians purposefully identified, who are current users of and knowledgeable about the REMS approach (e.g., authors of peer-reviewed publications on REMS) and are experts in the diagnosis and management of patients with osteoporosis, were invited to participate in the elicitation exercise. A purposeful sampling was deemed appropriate in order to identify information-rich cases, that is, individuals who are especially knowledgeable about or experienced with the phenomenon of interest (29). We developed an ad hoc tool on Microsoft Excel. For each parameter of interest, we asked experts to provide three point estimates, that is, the lowest (L), highest (H) and most likely value (M). As the target population for REMS and DXA can be quite heterogeneous (as confirmed by the clinicians interviewed), for the purposes of the CMA we considered women aged between 30 and 90 years as the target population, as it was the most cited by the clinicians interviewed and the one considered in several studies on REMS (22,23). In the Excel tool, clinicians were explicitly invited to give their estimates considering this target population.

The tool was developed for self-administration, and was sent by email with instructions for autonomous completion. Although face-to-face elicitation is recommended for some consensus methods and can be beneficial in terms of experts’ performance and engagement, it is not deemed necessary when the purpose of the study is to aggregate judgments mathematically (28). The tool consisted of an initial introductory section, with summary information on the study objectives and methods, and a questionnaire section, where experts were invited to provide their resource consumption estimates separately for REMS and DXA. In this section, clinicians were asked to indicate either the quantity of resources consumed (e.g., the time in minutes dedicated by different healthcare professionals in carrying out the diagnostic examination) or the percentage of patients consuming a certain resource (e.g., percentage of patients undergoing a certain laboratory test). The main cost items for which we gathered experts’ estimates were: (i) healthcare professionals’ time; (ii) administrative professionals’ time; (iii) additional instrumental examinations; (iv) laboratory tests; (v) consumables. The tool automatically verified the completeness and consistency of the estimates provided (e.g., that the M estimate was lower than the H and higher than the L) through a series of macros. In case data were not complete or consistent, an error message appeared, inviting responders to provide or correct their estimates in order to proceed with completion. Clinical experts filled in the tool between November 2021 and January 2022, and analyses were carried out in February 2022. Collected data were analyzed by averaging the estimates provided by experts. All experts were given equal weight.

Unit costs were retrieved using different sources in order to evaluate the consumption in monetary terms and perform the CMA. The unit costs of laboratory tests and instrumental examinations were sourced from “Nomenclatore dell’assistenza specialistica ambulatoriale”, an official document providing Italian national tariffs for outpatient services (30). Gross wage of personnel working in the healthcare sector was retrieved from “Conto annuale”, a census survey on Italian public administrations that provides data on the annual wages of Italian public employees for the latest year available (2019) (31). As regards residents, their gross wage, which is established by law, was retrieved from the official Decree of the Italian Ministry of Health (32). All wages were adjusted for inflation to 2021 (adjustment coefficient: 1.030) (33). In order to derive the wage per minute, we calculated the average number of working days and minutes based on the information provided in the most recent National Collective Work Contract, which regulates the working conditions for the professionals employed in the NHS (34). The cost of the devices (REMS and DXA) was collected from the accounting departments of the hospitals in which clinicians involved in the expert elicitation exercise operate (clinicians were asked on a voluntary basis to provide these data in a section of the tool).

We provided three different scenarios: (i) the base-case scenario (only M values considered); (ii) the most conservative scenario (only L values considered); (iii) the least conservative scenario (only H values considered). We calculated the difference in resource consumption and costs for REMS and DXA. The equality of estimates’ mean was assessed through a Student’s t-test (the p-value was reported). We provided separate estimates for current costs (e.g., time dedicated by personnel for diagnosis, laboratory test, etc.) and one-off costs (e.g., training and cost of the device).

A one-way deterministic sensitivity analysis was performed in order to assess how parameters’ uncertainty affected the results for current costs. Elicited parameters were varied according to their minimum (L) and maximum (H) estimate using the base-case scenario as reference. Unit costs and tariffs were varied according to ±20%. Results were graphically represented through tornado diagrams; only the parameters with the highest impact on costs were shown.

Results

Fifteen clinicians were invited to participate in the expert elicitation exercise. Thirteen of them agreed to participate and filled in the Excel tool (response rate = 85%; completion rate = 100%). The experts involved in this phase operate in seven Italian regions (i.e., Emilia-Romagna, Lazio, Liguria, Lombardia, Piemonte, Puglia, Toscana), in both private and public facilities, are representative of different medical specialties, and have an average experience of 24.5 years in the management of patients with osteoporosis (Supplementary table 1).

The clinicians provided all data compulsorily requested (i.e., there were not missing data as regards REMS and DXA resource consumption). Three clinicians completed only the section relative to REMS as they declared to have no experience of use of DXA.

Current costs

Supplementary table 2 shows the number of professionals involved, and the time (in minutes) dedicated by each professional to the different activities for the diagnosis of osteoporosis, for REMS and DXA approach respectively.

The total time dedicated to diagnosis by the different professionals was computed by multiplying the number of professionals involved in the diagnosis by the time dedicated to the different activities, separately for each responder. Then, the different estimates obtained for all responders were averaged. Table I reports the estimates relative to the total time dedicated to diagnosis (in minutes) by each professional figure for the three scenarios.

TABLE I -.

Resource consumption estimates

| REMS Mean (SD) | DXA Mean (SD) | REMS − DXA Mean (p-value) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Most conservative scenario (L) | Base-case scenario (M) | Least conservative scenario (H) | Most conservative scenario (L) | Base-case scenario (M) | Least conservative scenario (H) | Most conservative scenario (L) | Base-case scenario (M) | Least conservative scenario (H) | |

| Time dedicated to diagnosis (in minutes) | |||||||||

| Clinician | 15.8 (10.7) | 29.0 (12.6) | 55.0 (30.9) | 16.5 (13.6) | 26.6 (18.3) | 46 (27.8) | −0.7 (n.s.) | 2.4 (n.s.) | 9.0 (n.s.) |

| Nurse | 3.5 (7.7) | 3.8 (8.9) | 6.2 (12.9) | 6.2 (9.2) | 7.6 (10) | 11 (12.9) | −2.7 (n.s.) | −3.8 (n.s.) | −4.8 (n.s.) |

| Radiology technician | 2.3 (4.8) | 4.8 (9.2) | 6.9 (13.3) | 22.6 (11.7) | 32.3 (15.6) | 48.8 (17.1) | −20.3 (<0.001) | −27.5 (<0.001) | −41.9 (<0.001) |

| Resident | 2.7 (7.3) | 6.6 (11.7) | 13.1 (26.7) | 7 (13.4) | 12.6 (19.2) | 19.5 (27.2) | −4.3 (n.s.) | −6.0 (n.s.) | −6.4 (n.s.) |

| Other healthcare personne | l0.0 (0.0) | 0.4 (1.4) | 0.8 (2.8) | 1.5 (3.4) | 3.1 (7.9) | 10 (28.2) | −1.5 (n.s.) | −2.7 (n.s.) | −9.2 (n.s.) |

| Administrative staff | 2.8 (3.8) | 4.4 (6.3) | 7.9 (8.6) | 7.7 (8.4) | 21.7 (23.4) | 57.2 (89.6) | −4.9 (n.s.) | −17.3 (0.018) | −49.3 (0.050) |

| All professionals | 27.1 (21.5) | 49.1 (22.6) | 89.9 (48.8) | 61.5 (43.0) | 103.9 (44.7) | 192.5 (110.5) | −34.4 (0.020) | −54.8 (<0.001) | −102.6 (0.007) |

| Instrumental exams (% of patients) | |||||||||

| CT scan | 1.5 (5.5) | 2.8 (6.0) | 11.0 (27.7) | 6.6 (12.4) | 11.3 (21.0) | 24.4 (38.0) | −5.1 (n.s.) | −8.5 (n.s.) | −13.4 (n.s.) |

| Magnetic resonance | 2.5 (4.3) | 4.3 (6.6) | 13.2 (27.7) | 7.0 (11.1) | 11.5 (16.2) | 24.0 (32.5) | −4.5 (n.s.) | −7.2 (n.s.) | −10.8 (n.s.) |

| X-ray of the dorsal-lumbar spine | 15.9 (24.8) | 21.5 (24.7) | 33.5 (38.0) | 22.5 (24.2) | 33.5 (24.8) | 51.0 (36.3) | −6.6 (n.s.) | −12.0 (n.s.) | −17.5 (n.s.) |

| DXA (for REMS patients)/REMS (for DXA | 33.5 (38.7) | 39.2 (40.7) | 44.6 (43.9) | 19 (20.8) | 25.5 (25.4) | 48.5 (32.7) | − | − | − |

| Laboratory tests – I level (% of patients) | |||||||||

| 24-hour urinary calcium | 28.1 (30.2) | 35.8 (32.1) | 48.8 (38.3) | 31.5 (33.0) | 39.0 (34.8) | 62.5 (36.6) | −3.4 (n.s.) | −3.2 (n.s.) | −13.7 (n.s.) |

| Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) | 34.5 (39.3) | 41.2 (40.7) | 56.0 (43.7) | 45.5 (44.7) | 52.0 (44.9) | 74.0 (40.0) | −11.0 (n.s.) | −10.8 (n.s.) | −18.0 (n.s.) |

| Calcemia | 40.9 (43.7) | 48.8 (43.0) | 61.6 (43.3) | 57.0 (49.5) | 59.0 (48.9) | 77.5 (41.3) | −16.1 (n.s.) | −10.2 (n.s.) | −15.9 (n.s.) |

| Complete blood count | 31.2 (46.2) | 35.0 (45.9) | 44.6 (47.5) | 36.0 (43.3) | 41.0 (44.6) | 61.5 (43.8) | −4.8 (n.s.) | −6.0 (n.s.) | −16.9 (n.s.) |

| Creatininemia | 37.8 (45.4) | 43.2 (45.2) | 54.1 (46.4) | 49.5 (47.9) | 54.0 (46.7) | 75.0 (40.6) | −11.7 (n.s.) | −10.8 (n.s.) | −20.9 (n.s.) |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) | 27.0 (41.3) | 32.7 (41.7) | 46.9 (46.4) | 31.0 (42.3) | 36.5 (42.6) | 58.5 (44.2) | −4.0 (n.s.) | −3.8 (n.s.) | −11.6 (n.s.) |

| Phosphorus | 40.9 (43.7) | 45.3 (44.1) | 58.2 (43.6) | 47.0 (49.9) | 51.5 (47.6) | 72.5 (41.3) | −6.1 (n.s.) | −6.2 (n.s.) | −14.3 (n.s.) |

| Protidemia (fraction) | 30.9 (46.3) | 34.4 (46.0) | 46.4 (46.0) | 37.0 (44.0) | 42.0 (43.1) | 65.0 (41.7) | −6.1 (n.s.) | −7.6 (n.s.) | −18.6 (n.s.) |

| Laboratory tests – II level (% of patients) | |||||||||

| Ionized calcium | 16.3 (30.1) | 22.7 (36.4) | 34.5 (45.8) | 19.2 (32.3) | 26.0 (38.7) | 48.3 (48.6) | −2.9 (n.s.) | −3.3 (n.s.) | −13.8 (n.s.) |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) | 17.9 (33.0) | 22.5 (33.4) | 33.7 (40.4) | 22.4 (39.1) | 25.1 (37.7) | 44.5 (42.5) | −4.5 (n.s.) | −2.6 (n.s.) | −10.8 (n.s.) |

| Parathyroid hormone (PTH) | 30.5 (40.2) | 39.4 (40.6) | 54.5 (42.2) | 37.5 (43.8) | 45.0 (45.0) | 67.5 (43.3) | −7.0 (n.s.) | −5.6 (n.s.) | −13.0 (n.s.) |

| 25-Hydroxy vitamin D | 44.6 (42.0) | 52.7 (40.7) | 73.8 (36.2) | 48.0 (47.6) | 53.5 (46.7) | 75.5 (40.9) | −3.4 (n.s.) | −0.8 (n.s.) | −1.7 (n.s.) |

| Overnight dexamethasone suppression | 8.2 (19.5) | 11.5 (22.4) | 22.0 (34.4) | 8.7 (21.8) | 14.8 (25.9) | 53.9 (41.6) | −0.5 (n.s.) | −3.3 (n.s.) | −13.9 (n.s.) |

| Serum immunofixation | 9.0 (20.0) | 13.1 (24.2) | 22.5 (36.0) | 12.2 (27.8) | 16.9 (28.6) | 37.0 (41.0) | −3.2 (n.s.) | −3.8 (n.s.) | −14.5 (n.s.) |

| Urine immunofixation | 6.6 (16.3) | 9.8 (19.1) | 19.2 (32.8) | 7.2 (15.4) | 11.9 (18.0) | 33.0 (38.0) | −0.6 (n.s.) | −2.1 (n.s.) | −13.8 (n.s.) |

| Anti-transglutaminase antibodies (ATA) | 14.4 (30.4) | 18.5 (31.2) | 29.1 (38.4) | 16.7 (33.1) | 19.4 (32.0) | 39.5 (41.5) | −2.3 (n.s.) | −0.9 (n.s.) | −10.4 (n.s.) |

Since the p-value is also affected by the sample size (the smaller the sample size, the higher the p-value), we should be careful in interpreting the lack of statistical significance of the difference in estimates (as it may be partly driven by the low number of observations).

CT = computed tomography; DXA = dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; n.s. = not significant; REMS = Radiofrequency Echographic Multi Spectrometry; SD = standard deviation.

Table I also shows resource consumption estimates related to additional instrumental exams and laboratory tests for the diagnosis of osteoporosis. The high proportion of patients undergoing a DXA exam after REMS is due to the fact that, at the time of this study, DXA was the only diagnostic exam recognized by the Italian Medicines Agency (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco – AIFA) for the prescription and reimbursement of some high-cost drugs (35,36). For this reason, in cost calculation we did not consider this item. In order to counterbalance this omission and be conservative in our estimates, we did not consider the REMS exam performed after DXA. However, unlike the former case, the execution of REMS after DXA is not driven by drug prescription and reimbursement needs. Therefore, we may infer that clinicians voluntarily decide to perform REMS after DXA to improve the diagnosis of osteoporosis, for example, in those cases where DXA results can be biased by the presence of some artifacts (e.g., osteoarthritis, previous vertebral fracture), as underlined by the interviewees.

The cost of consumables (i.e., gloves, medical bed sheet, disinfectant, gel) was not considered in the present analysis due to the very limited quantity used for both exams and their contained unit cost.

Supplementary table 3 reports the gross wages of professionals (31,32), and Supplementary table 4 shows the unit cost of instrumental exams and laboratory tests (30).

Table II shows the average cost of personnel (healthcare professionals and administrative staff), instrumental examinations and laboratory tests for the diagnosis of osteoporosis. Considering the base-case scenario, the cost of all professionals for the diagnosis of osteoporosis amounts to €31.9 for REMS and €48.8 for DXA, entailing a saving of €16.9 for REMS. It is interesting to note that, for REMS, the cost of clinicians represents the major driver of personnel cost (approximately 80% of the total personnel cost). For DXA, the personnel cost is more distributed across different professional figures, namely clinicians (48%), radiology technicians (24%) and administrative staff (14%). These findings suggest that the use of DXA usually entails the involvement of more professional figures than REMS, with potential consequences in terms of increasing need of coordination and thus organizational costs. The cost of instrumental examinations and laboratory tests amounts to approximately €45.1 for REMS and €68.2 for DXA, with a saving of €23.1 for REMS.

TABLE II -.

Current costs for the diagnosis of osteoporosis

| REMS Mean (SD) | DXA Mean (SD) | REMS − DXA Mean (p-value) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Most conservative scenario (L) | Base-case scenario (M) | Least conservative c scenario (H) | Most onservative scenario (L) | Base-case scenario (M) | Least conservative scenario (H) | Most conservative scenario (L) | Base-case scenario (M) | Least conservative scenario (H) | |

| Personnel | |||||||||

| Clinician | €13.9 (9.4) | €25.5 (11.1) | €48.3 (27.1) | €14.5 (12) | €23.4 (16.1) | €40.4 (24.4) | −€0.6 (n.s.) | €0.6 (n.s.) | €7.9 (n.s.) |

| Nurse | €1.3 (2.8) | €1.4 (3.3) | €2.2 (4.7) | €2.3 (3.4) | €2.8 (3.7) | €4.0 (4.7) | −€1.0 (n.s.) | −€1.4 (n.s.) | −€1.8 (n.s.) |

| Radiology technician | €0.8 (1.7) | €1.7 (3.3) | €2.5 (4.8) | €8.2 (4.2) | €11.7 (5.6) | €17.6 (6.2) | −€7.3 (<0.001) | −€9.9 (<0.001) | −€15.1 (<0.001) |

| Resident | €0.7 (2.0) | €1.8 (3.2) | €3.6 (7.3) | €1.9 (3.7) | €3.5 (5.3) | €5.3 (7.5) | −€1.2 (n.s.) | −€1.6 (n.s.) | −€1.8 (n.s.) |

| Other healthcare personnel | €0.0 (0.0) | €0.1 (0.4) | €0.2 (0.8) | €0.4 (1.0) | €0.9 (2.3) | €2.9 (8.3) | −€0.4 (n.s.) | −€0.8 (n.s.) | −€2.7 (n.s.) |

| Administrative staff | €0.8 (1.2) | €1.3 (1.9) | €2.4 (2.6) | €2.4 (2.6) | €6.6 (7.1) | €17.5 (27.4) | −€1.5 (n.s.) | −€5.3 (0.018) | −€15.1 (n.s.) |

| Total personnel | €17.6 (12.1) | €31.9 (12.3) | €59.3 (30.1) | €29.6 (21) | €48.8 (23.1) | €87.8 (43) | −€12.0 (n.s.) | −€16.9 (0.034) | −€28.5 (n.s.) |

| Instrumental exams | |||||||||

| CT scan | €1.2 (4.3) | €2.2 (4.6) | €8.5 (21.5) | €5.1 (9.7) | €8.8 (16.3) | €19 (29.5) | −€3.9 (n.s.) | −€6.6 (n.s.) | −€10.4 (n.s.) |

| Magnetic resonance | €2.9 (5.0) | €5.0 (7.7) | €15.2 (32.1) | €8.1 (12.9) | €13.3 (18.7) | €27.8 (37.6) | −€5.2 (n.s.) | −€8.3 (n.s.) | −€12.6 (n.s.) |

| X-ray of the dorsal-lumbar spine | €5.5 (8.6) | €7.4 (8.5) | €11.6 (13.1) | €7.8 (8.4) | €11.6 (8.6) | €17.6 (12.6) | −€2.3 (n.s.) | −€4.2 (n.s.) | −€6 (n.s.) |

| Laboratory tests − I level | |||||||||

| 24-hour urinary calcium | €0.3 (0.3) | €0.4 (0.4) | €0.6 (0.4) | €0.4 (0.4) | €0.4 (0.4) | €0.7 (0.4) | €0.0 (n.s.) | €0.0 (n.s.) | −€0.2 (n.s.) |

| Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) | €0.4 (0.4) | €0.4 (0.4) | €0.6 (0.5) | €0.5 (0.5) | €0.5 (0.5) | €0.8 (0.4) | −€0.1 (n.s.) | −€0.1 (n.s.) | −€0.2 (n.s.) |

| Calcemia | €0.5 (0.5) | €0.6 (0.5) | €0.7 (0.5) | €0.6 (0.6) | €0.7 (0.6) | €0.9 (0.5) | −€0.2 (n.s.) | −€0.1 (n.s.) | −€0.2 (n.s.) |

| Complete blood count | €1.0 (1.5) | €1.1 (1.5) | €1.4 (1.5) | €1.1 (1.4) | €1.3 (1.4) | €1.9 (1.4) | −€0.2 (n.s.) | −€0.2 (n.s.) | −€0.5 (n.s.) |

| Creatininemia | €0.4 (0.5) | €0.5 (0.5) | €0.6 (0.5) | €0.6 (0.5) | €0.6 (0.5) | €0.8 (0.5) | −€0.1 (n.s.) | −€0.1 (n.s.) | −€0.2 (n.s.) |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) | €0.5 (0.8) | €0.6 (0.8) | €0.9 (0.9) | €0.6 (0.8) | €0.7 (0.8) | €1.1 (0.9) | −€0.1 (n.s.) | −€0.1 (n.s.) | −€0.2 (n.s.) |

| Phosphorus | €0.6 (0.6) | €0.7 (0.6) | €0.8 (0.6) | €0.7 (0.7) | €0.8 (0.7) | €1.1 (0.6) | −€0.1 (n.s.) | −€0.1 (n.s.) | −€0.2 (n.s.) |

| Protidemia (fraction) | €1.3 (2.0) | €1.5 (1.9) | €2 (1.9) | €1.6 (1.9) | €1.8 (1.8) | €2.7 (1.8) | −€0.3 (n.s.) | −€0.3 (n.s.) | −€0.8 (n.s.) |

| Laboratory tests − II level | |||||||||

| Ionized calcium | €0.2 (0.3) | €0.3 (0.4) | €0.4 (0.5) | €0.2 (0.4) | €0.3 (0.4) | €0.5 (0.5) | €0.0 (n.s.) | €0.0 (n.s.) | −€0.2 (n.s.) |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) | €1.0 (1.8) | €1.2 (1.8) | €1.8 (2.2) | €1.2 (2.1) | €1.4 (2.1) | €2.4 (2.3) | −€0.2 (n.s.) | −€0.1 (n.s.) | −€0.6 (n.s.) |

| Parathyroid hormone (PTH) | €5.8 (7.6) | €7.5 (7.7) | €10.3 (8) | €7.1 (8.3) | €8.5 (8.5) | €12.8 (8.2) | −€1.3 (n.s.) | −€1.1 (n.s.) | −€2.5 (n.s.) |

| 25-Hydroxy vitamin D | €7.1 (6.7) | €8.4 (6.4) | €11.7 (5.7) | €7.6 (7.5) | €8.5 (7.4) | €12 (6.5) | −€0.5 (n.s.) | −€0.1 (n.s.) | −€0.3 (n.s.) |

| Overnight dexamethasone suppression test | €0.6 (1.5) | €0.9 (1.7) | €1.7 (2.7) | €0.7 (1.7) | €1.2 (2.0) | €2.8 (3.2) | €0.0 (n.s.) | −€0.3 (n.s.) | −€1.1 (n.s.) |

| Serum immunofixation | €1.9 (4.2) | €2.7 (5) | €4.7 (7.5) | €2.5 (5.8) | €3.5 (6) | €7.7 (8.6) | −€0.7 (n.s.) | −€0.8 (n.s.) | −€3.0 (n.s.) |

| Urine immunofixation | €1.4 (3.4) | €2.1 (4.0) | €4.0 (6.9) | €1.5 (3.2) | €2.5 (3.8) | €6.9 (7.9) | −€0.1 (n.s.) | −€0.4 (n.s.) | −€2.9 (n.s.) |

| Anti-transglutaminase antibodies (ATA) | €1.4 (3.0) | €1.8 (3.1) | €2.9 (3.8) | €1.7 (3.3) | €1.9 (3.2) | €3.9 (4.1) | −€0.2 (n.s.) | −€0.1 (n.s.) | −€1.0 (n.s.) |

| Total exams | €34 (41.3) | €45.1 (45.2) | €80.5 (93.6) | €49.6 (58.1) | €68.2 (72.1) | €123.6 (108.3) | −€15.6 (n.s.) | −€23.1 (n.s.) | −€43.0 (n.s.) |

CT = computed tomography; DXA = dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; n.s. = not significant; REMS = Radiofrequency Echographic Multi Spectrometry; SD = standard deviation.

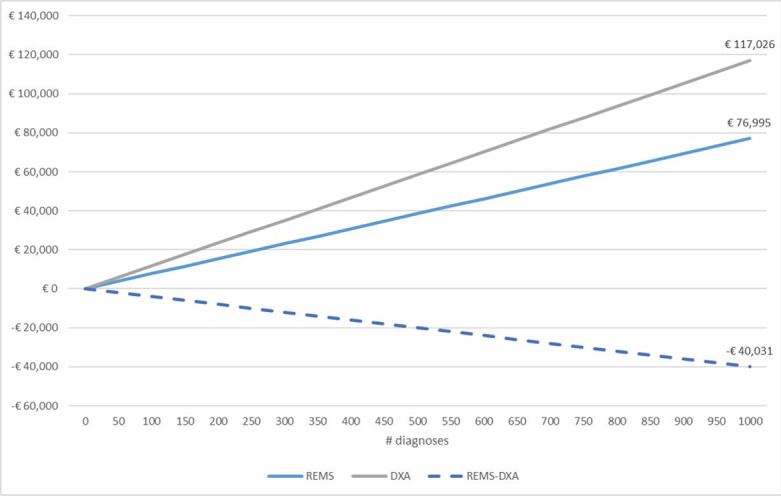

Overall, the use of REMS approach for the diagnosis of osteoporosis is associated with a mean saving for the NHS of €40.0 (range: €27.6-€71.5) for each patient (Fig. 1). By increasing the number of patients diagnosed through the REMS approach (see Fig. 2 for the base-case scenario), the NHS would be able to save a significant amount of healthcare resources to diagnose osteoporosis (approximately €40.000 saved every 1,000 diagnosed patients).

Fig. 1 -.

Total costs and difference in costs for Radiofrequency Echographic Multi Spectrometry and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

Fig. 2 -.

Cumulative costs and savings (base-case scenario).

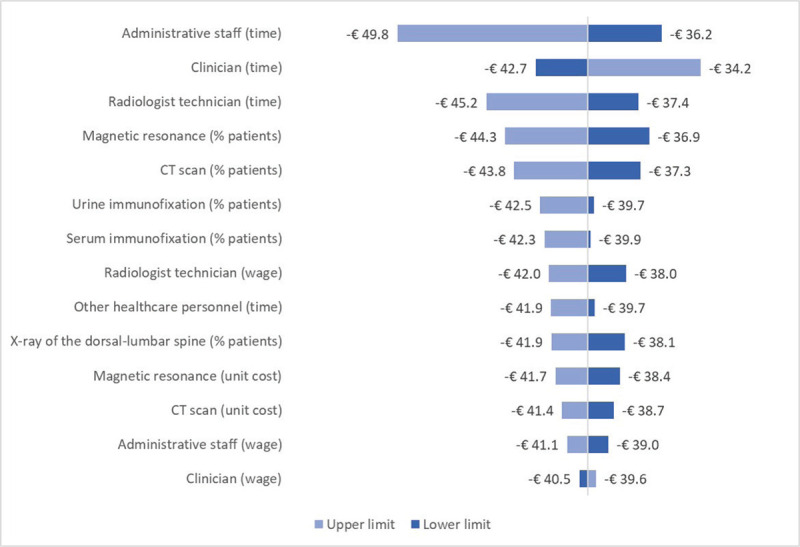

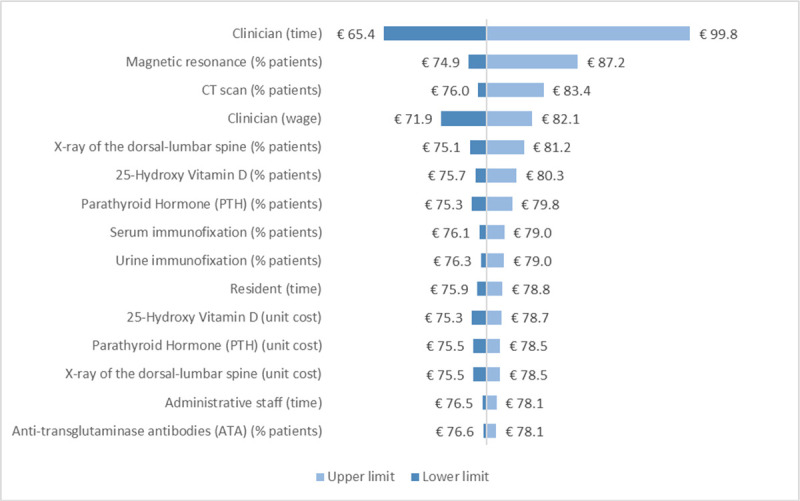

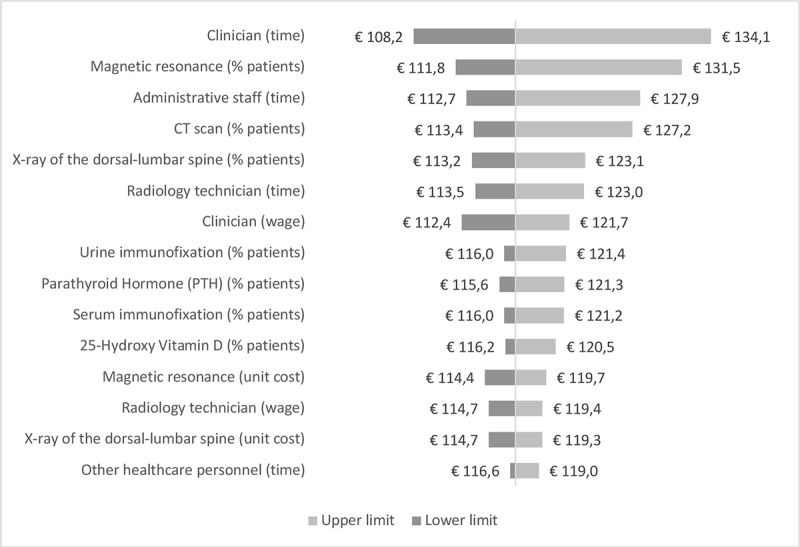

According to the sensitivity analysis, the two parameters whose variation has the largest impact both on REMS and DXA costs are the time dedicated by clinicians to diagnosis and the percentage of patients undergoing magnetic resonance as additional instrumental exam (Supplementary figure 1, Supplementary figure 2). In particular, when the time dedicated by clinicians is varied according to its lower (L estimate) and upper (H estimate) limit, the cost of REMS ranges from €65.4 to €99.8, while the cost of DXA was from €108.2 to €134.1. The three parameters whose variation has the largest impact on the difference in costs between REMS and DXA are the time dedicated by administrative staff, clinicians and radiology technicians (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 -.

Sensitivity analysis – Difference in costs between Radiofrequency Echographic Multi Spectrometry and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

One-off costs

In the tool, clinicians were asked to provide an estimate of the training time dedicated by the healthcare professionals to learn how to use the technology in clinical practice, both for REMS and DXA (Supplementary table 5). Considering the base-case scenario, the training for REMS entails a lower amount of time dedicated by healthcare professionals, resulting in a one-off cost of €357.4 compared to €1,169.0 for DXA (Tab. III). A lower training time is likely to be beneficial not only in terms of technology-related costs but also in terms of organizational impact, and could be used to leverage the introduction and uptake of REMS in clinical practice.

TABLE III -.

Cost of personnel for training

| Professional figure | REMS Mean (SD) | DXA Mean (SD) | REMS − DXA Mean (p-value) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Most conservative scenario (L) | Base-case scenario (M) | Least conservative scenario (H) | Most conservative scenario (L) | Base-case scenario (M) | Least conservative scenario (H) | Most conservative scenario (L) | Base-case scenario (M) | Least conservative scenario (H) | |

| Clinician | €138.8 (355.7) | €269.8 (712.8) | €970.5 (2,881.7) | €519.7 (1,161.6) | €744.5 (1,546.0) | €949 (1,913.8) | −€381 (n.s.) | −€474.7 (n.s.) | €21.4 (n.s.) |

| Nurse | €1.3 (3.3) | €1.8 (4.8) | €19.4 (48.6) | €5.8 (9.6) | €8.8 (15.3) | €11.3 (21.5) | −€4.6 (n.s.) | −€6.9 (n.s.) | €8.1 (n.s.) |

| Radiology technician | €3.3 (8.1) | €11.4 (23.2) | €16.7 (34.4) | €269.7 (491.6) | €389.3 (673.9) | €703.8 (954.1) | −€266.4 (n.s.) | −€377.9 (n.s.) | −€687.1 (0.016) |

| Resident | €32.9 (113.6) | €74.4 (225.7) | €156.7 (452.6) | €4.4 (10.6) | €23 (41.9) | €36.4 (64.2) | €28.5 (n.s.) | €51.4 (n.s.) | €120.3 (n.s.) |

| Other healthcare personnel | €0.0 (0.0) | €0.0 (0.0) | €21.6 (77.9) | €1.8 (5.6) | €3.5 (11.1) | €10.5 (33.3) | −€1.8 (n.s.) | −€3.5 (n.s.) | €11.1 (n.s.) |

| Total professionals | €176.2 (467.7) | €357.4 (933.6) | €1,184.8 (3,318.9) | €801.4 (1,635.5) | €1,169.0 (2,186.5) | €1,711.1 (2,688.6) | −€625.2 (n.s.) | −€811.6 (n.s.) | −€526.2 (n.s.) |

Since the p-value is also affected by the sample size (the smaller the sample size, the higher the p-value), we should be careful in interpreting the lack of statistical significance of the difference in estimates (as it may be driven by the low number of observations).

DXA = dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; n.s. = not significant; REMS = Radiofrequency Echographic Multi Spectrometry; SD = standard deviation.

Six clinicians provided us with the data regarding the cost of REMS device, and three with the cost of DXA technology (for different models, namely Hologic Horizon, Hologic Lunar and Hologic Discovery). By averaging the values provided, which were quite heterogeneous, the unit cost of acquisition (with VAT) for REMS equals €32,833 (with no maintenance costs), while for DXA it was €45,000 (including €5,000 for maintenance costs). Moreover, although not considered in the present analysis, the use of DXA requires a dedicated radiology room, with a relevant investment for its set-up (e.g., to shield medical personnel from harmful secondary radiation), while REMS can be used in the ambulatory or at the bed of the hospitalized patient or at the patient’s home.

Discussion

REMS has been recognized by international and national scientific associations as a promising approach for the diagnosis of osteoporosis (19,24). In 2021, the Italian Inter-Society Health Ministry Guidelines developed by the Italian National Institute of Health – Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS) on Fragility Fractures have stated that, on the basis of published scientific evidence, “REMS reaches a good level of accuracy and precision, is a good predictor of fragility fracture risk and may improve the diagnosis of osteoporosis in the routine care” (page 1173) (24). Moreover, the guidelines envisage a substantial range of applications for REMS, wider than for DXA, including: (i) fracture risk assessment in pediatric patients, pregnant women and patients at risk of secondary osteoporosis (e.g., diabetic or oncological patients); (ii) use in primary care (in some countries, the need for radiological protection with DXA could represent a problem), (iii) use in fractured and non-transferable hospitalized patients (thanks to REMS ease of transportation). Overall, the guidelines recognize that REMS can improve the “continuity of care at the patients’ home” (page 1172) (24). The clinicians interviewed in the present study cited several characteristics of REMS that could favor its diffusion in the coming years, also as a screening method: (i) simplicity of the method; (ii) practicality and portability of the device (e.g., use on bedridden patients); (iii) possibility of following the patient on the territory rather than in the hospital, in line with the recent indications of the Italian Piano Nazionale Resistenza e Resilienza (PNRR); (iv) possibility for the clinician to manage the diagnosis independently, without having to rely on the radiology technician and radiologist for the execution and reporting of the examination respectively; (v) greater reliability in case of artifacts (e.g., osteoarthritis, previous vertebral fracture, calcifications, osteophytes, etc.); (vi) absence of ionizing radiation (use in women of childbearing age, pregnant women and children); (vii) possibility for the patient to be diagnosed timely, avoiding the long waiting lists for DXA in some local or regional contexts in Italy.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the direct healthcare costs associated with the use of the REMS approach vs. DXA for the diagnosis of osteoporosis. The results of our CMA, conducted from the perspective of the Italian NHS, suggest that the REMS approach is associated with lower direct healthcare costs with respect to DXA. Overall, in fact, the mean current costs amount to €77.0 for REMS (€31.9 for time dedicated by healthcare personnel and administrative staff, and €45.1 for additional instrumental exams and laboratory tests) and to €117.0 for DXA (€48.8 for time dedicated by healthcare personnel and administrative staff, and €68.2 for additional instrumental exams and laboratory tests). Also one-off costs are lower for the REMS approach: €357.4 vs. €1,169.0 for training, and €32,833 vs. €45,000 for the acquisition of the device. These findings may inform the decision regarding the inclusion of REMS among Livelli Essenziali di Assistenza, that is, the healthcare services and treatments that the Italian NHS provides to all citizens free of charge or upon payment of a fee. In particular, the evidence on REMS direct healthcare costs could be used by policy-makers to define a fair reimbursement tariff for this novel diagnostic approach, reflecting the cost actually borne by the healthcare system in delivering the care service.

Besides the cost estimates and results provided in the present analysis, it is worth noting that a higher diffusion of REMS could generate additional savings for the healthcare system, the patients and the society as a whole.

In a section of the tool, clinicians declared that, on average, the instrumental exam execution is concomitant with the specialist outpatient visit in the 70% of cases with REMS (L = 56%, H = 88%) while only in the 19% of cases with DXA (L = 12%; H = 35%). Moreover, the communication of diagnostic results is concomitant with exam execution in the 81% of cases with REMS (L = 70%; H = 93%) while only in the 29% of cases with DXA (L = 22%; H = 45%). Although patients now have the possibility to access their medical reports online, the fact that, in the majority of cases, the REMS exam is concomitant with the specialist outpatient visit translates into a significantly lower number of accesses for patients diagnosed with the REMS approach. In turn, this implies savings in terms of direct non-healthcare costs (e.g., cost of transportation for the patient and cost of informal caregiving) and indirect costs (e.g., loss of productivity due to absence from work or leisure time lost).

In the tool clinicians also declared that, on average, 25% of patients cannot undergo DXA due to several reasons (e.g., bedridden patients, pregnant women, etc.). Moreover, the average frequency of follow-up is different between the two approaches: 21 months for DXA (L = 13; H = 28) and 13 months for REMS (L = 9; H = 19). The higher frequency of follow-up and the higher number of patients who can access REMS may have a significant and positive impact on the ability of the NHS to timely diagnose osteoporosis and prevent fragility fractures (as also underlined in the 2021 Italian Inter-Society Health Ministry Guidelines on Fragility Fractures), with a positive impact on both the patient and the overall healthcare system. A prospective observational study with a 5-year follow-up found that REMS is more effective than DXA in identifying incident fragility fractures both at the vertebral (OR = 2.6 for REMS vs. 1.7 for DXA) and the lumbar site (OR = 2.81 for REMS vs. 2.68 for DXA) (22). Fragility fractures have been demonstrated to be associated with a substantial clinical and economic burden. In fact, the study by Borgström and colleagues (2020) (7) estimated that, in Italy, the mean direct healthcare cost of a hip fracture amounts to €21,307, the cost of a vertebral fracture to €4,713 and the cost of a forearm fracture to €1,301. Moreover, the authors reported that, in 2017, the Quality-Adjusted Life-Years lost due to morbidity and mortality associated with osteoporotic fractures in our country were approximately 229,000, and they envisage that these estimates will increase in the next few years due to changing demography. These data suggest that a delay in diagnosis of osteoporosis and fragility fractures will likely translate into a higher burden for the NHS and the society as a whole. Following the Italian Inter-Society Health Ministry Guidelines, a more widespread use of REMS could help enhance the ability of the NHS to improve the overall diagnostic pathway for osteoporosis.

Although this study contributed at filling the evidence gap on the economic impact of REMS and DXA, it has some limitations. Coherently with other expert elicitation studies, we relied on a purposive sample of experts rather than on a random one. Although a purposive sampling may be subject to selection bias issues, it allowed us to carefully select clinicians on the basis of their recognized expertise in the management of patients with osteoporosis and the use of the technology, which could not be possible through a random sampling. This is particularly true for recently introduced technologies, like REMS, for which the number of clinicians knowledgeable about the technology itself is very limited. In line with Bojke and colleagues (28), in selecting the experts for the elicitation exercise we relied on three typically used criteria, that is, normative expertise, substantive expertise and willingness to participate. Moreover, we took into account their geographical distribution, in order to capture heterogeneity in clinical practice in different Italian regions, and different medical specialties (i.e., endocrinology, gynecology, internal medicine, orthopedics, physiatry, radiology and rheumatology). Finally, as suggested by Bojke and colleagues (28), we attempted to minimize experts’ motivational biases by ensuring that our sample contained a range of different viewpoints.

Another limitation concerns the impossibility to retrieve some of the cost data regarding DXA technology (e.g., investment cost for setting up the radiology room), possibly underestimating the cost associated with DXA.

Future avenues of research may explore prospectively the economic impact of the prevention of fragility fractures with REMS vs. DXA in the Italian clinical practice.

Conclusion

Clinical studies have shown that REMS has a diagnostic accuracy and precision at least comparable to that of DXA. Moreover, scientific associations and the 2021 Italian Inter-Society Health Ministry Guidelines on Fragility Fractures have recognized that REMS is a valuable diagnostic approach for osteoporosis that may facilitate the patients’ care pathway. These results and those provided by the present study regarding the economic impact of the two diagnostic approaches may inform policy-makers on the value of the REMS approach in the earlier diagnosis for osteoporosis, and support their decision regarding the reimbursement and diffusion of the technology in the Italian NHS. In particular, the results of this study may contribute to the definition of a fair reimbursement tariff for REMS, which is not yet comprised in Livelli Essenziali di Assistenza, and which should reflect the cost borne by the healthcare system in delivering the care service.

Disclosures

Funding: CERGAS SDA Bocconi received a research grant from Echolight S.p.A. for this study. The funder had no access to the dataset and had no role in study design, data collection or analysis.

Conflict of interest: Ludovica Borsoi and Patrizio Armeni declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and publication of this study. Maria Luisa Brandi declares the following competing interests: Echolight S.p.A. (consulting fees).

Author contributions: Conceptualization, Ludovica Borsoi and Patrizio Armeni; Data curation, Ludovica Borsoi; Formal analysis, Ludovica Borsoi; Funding acquisition, Ludovica Borsoi and Patrizio Armeni; Investigation, Ludovica Borsoi; Methodology, Ludovica Borsoi and Patrizio Armeni; Project administration, Ludovica Borsoi and Patrizio Armeni; Supervision, Patrizio Armeni; Visualization, Ludovica Borsoi; Writing – original draft, Ludovica Borsoi; Writing – review and editing, Ludovica Borsoi, Patrizio Armeni and Maria Luisa Brandi.

Research ethics: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Università Commerciale Luigi Bocconi.

Supplementary File 1- Interview guide

Objective

The objective of the study for which we are conducting this interview is to evaluate the costs associated with the use of the REMS approach for the diagnosis of osteoporosis compared to the gold standard (DXA) from the perspective of the National Health Service through a cost- minimization analysis.

Professional information

We would like to start the interview by asking you some professional information. In particular, we would like to know:

the role you currently hold;

your affiliation;

your experience in the management of patients with osteoporosis.

Target population

Recently published studies that evaluated the diagnostic and predictive ability of REMS technology compared to DXA (gold standard) involved the following populations: 1) postmenopausal women aged between 51 and 70 years (Di Paola et al, 2018); 2) women aged between 30 and 90 years (Cortet et al, 2021; Adami et al, 2020; Di Paola et al, 2018), 3) men aged between 30 and 90 years (Ciardo et al, SIOMMMS 2020) and 4) adolescents (Caffarelli et al. ICCBH, 2019).

-

In clinical practice, and in your experience, what is the target population for the REMS approach in the diagnosis of osteoporosis? Is it the same for DXA?

-

1.1.

Are there any differences?

-

1.2.

If so, why?

-

1.1.

Diagnostic pathway

-

2.

Could you explain to us how a diagnosis of osteoporosis is made using the REMS approach on axial anatomical sites? And with DXA? (hint: from the interview with the patient to the examination and reporting)

-

2.1.

In which setting(s) is the examination usually carried out with the REMS approach? And with DXA? (hint: outpatient, day hospital, hospitalization, at home)

-

2.2.

Are these exams followed by other instrumental exams? If so, which ones? Are they different depending on the initial approach adopted (REMS or DXA)?

-

2.1.

-

3.

Does the overall diagnostic pathway vary depending on the results obtained through the main instrumental examination (REMS or DXA)? If so, in what aspects?

-

3.1.

What is the impact of this result on the choice of the following therapeutic pathway? Is the impact different depending on whether the outcome derives from the REMS approach rather than DXA?

-

3.1.

-

4.

Based on your experience, what are the factors that most influence the choice between the two diagnostic approaches (REMS and DXA)? (hint: clinical characteristics of the patient; type of patient - e.g. bedridden patient, pregnant woman, fractured patient, arthrosis, rare diseases; ease of use of the technology, safety, technology already present in the hospital; need to monitor the state patient's bone; waiting lists; etc.)

-

4.1.

According to your experience, do you think there is a problem of accessibility of patients to REMS for the diagnosis of osteoporosis? What about DXA? For what reason(s)?

-

4.1.1.

If so, do you think this has a significant impact on the NHS's ability to identify patients at risk and make timely diagnoses?

-

4.1.1.

-

4.2.

In your experience, is there an instrumental examination (REMS or DXA) preferable in the following situations?

Fracture

Bedridden patient

Bone degeneration (arthrosis, calcifications, or other)

Prevention

Diseases that increase the risk of developing osteoporosis

Patient with high BMI

Pregnancy

If so, which one? Is it just preferable or strongly recommended?

-

5.

Once a diagnosis of osteoporosis has been established, what is the recommended frequency of repetition of the instrumental examination to monitor the progression of bone loss?

-

5.1.

Are there differences in timing depending on the approach adopted for the diagnosis (REMS or DXA)? If so, why?

-

5.2.

In your experience, does the frequency of the exam in real clinical practice reflect that recommended? If not, why?

-

5.3.

For follow-up instrumental examinations, is it important to maintain the same approach (REMS or DXA) adopted in the diagnosis or is it possible to change?

-

5.3.1.

Does the therapeutic pathway change depending on the instrumental examination performed in the follow-up? If so, in what aspects?

-

5.3.1.

-

5.1.

-

4.1.

Consumption of resources

-

6.

Is there a REMS equipment in your structure? What about DXA?

-

6.1.

If so, is there more than one (REMS and / or DXA)?

-

6.1.

-

7.

Who are the professionals involved in the diagnosis of osteoporosis through the REMS approach? And with DXA? (hint: medical doctor, resident, radiology technician, nurse, other healthcare personnel)

-

7.1.

Is it necessary to carry out special training for the use of REMS for the purpose of diagnosing osteoporosis? What about DXA for the purpose of diagnosing osteoporosis? If so, can you describe how it is done in the facility where you work?

-

7.1.

-

8.

For the purpose of diagnosing osteoporosis, does the use of REMS imply an involvement of administrative staff? If so, for which activities? And what about DXA?

-

9.

What consumables are used for the execution of REMS for the purpose of diagnosing osteoporosis? What about DXA? (hint: gloves, disinfectant, medical bed sheet, etc.)

-

10.

The SIOMMMS guidelines provide for carrying out some laboratory tests (level I and II*) that allow the differential diagnosis between primary and secondary osteoporosis and the evaluation of bone metabolism. Are these laboratory tests performed regardless of the instrumental examination performed (REMS or DXA) for the purpose of diagnosing osteoporosis? Or are there any differences?

-

10.1.

Based on your experience, what is the percentage of patients with a positive instrumental test for whom I and II level laboratory tests are performed?

-

10.1.

Supplementary Table 1.

- Sample description (expert elicitation exercise)

| Experts characteristics (n=13) | |

|---|---|

| Professional figure, % | |

| Endocrinologist | 15.4% |

| Gynecologist | 15.4% |

| Internist | 15.4% |

| Orthopedist | 15.4% |

| Physiatrist | 15.4% |

| Radiologist | 7.7% |

| Rheumatologist | 15.4% |

| Geographical region in which they operate, % | |

| North | 38.5% |

| Centre | 38.5% |

| South | 23.1% |

| Nature of facility in which they operate, % | |

| Public | 46.2% |

| Private | 53.8% |

| Years of experience in managing patients with osteoporosis, mean (SD) | 24.5 (10.4) |

Supplementary Table 2.

- Resource consumption – Number of professionals and time dedicated by each professional to the diagnosis of osteoporosis

| Professional figure | Input | REMS mean (SD) | DXA mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Most conservative scenario (L) | Base-case scenario (M) | Least conservative scenario (H) | Most conservative scenario (L) | Base-case scenario (M) | Least conservative scenario (H) | ||

| Clinician | |||||||

| # professionals | 0.8 (0.4) | 0.9 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.4) | 0.9 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.3) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) - Patient interview | 5.1 (2.8) | 9.5 (4.5) | 13.2 (6.6) | 4.6 (4.3) | 6.6 (6.6) | 10.5 (9.0) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) - Exam execution | 7.3 (3.9) | 10.5 (4.3) | 15.4 (7.2) | 3.0 (5.4) | 6.2 (7.4) | 10.5 (9.8) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) - Reporting and communication of the outcome | 5.8 (3.9) | 10.2 (4.8) | 14.5 (6.9) | 6.1 (4) | 9.3 (4) | 13 (5.4) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) – Manual data elaboration | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 3.0 (4.8) | 5.5 (6.4) | 8.0 (8.9) | |

| Nurse | |||||||

| # professionals | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.6 (0.5) | 0.6 (0.5) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) - Patient interview | 1.2 (2.2) | 1.4 (2.2) | 1.5 (2.4) | 2.8 (4.1) | 3.4 (4.6) | 5.5 (5.5) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) - Exam execution | 1.9 (4.3) | 2.3 (4.8) | 3.5 (8.5) | 3 (4.2) | 3.7 (4.9) | 5.0 (7.1) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) - Reporting and communication of the outcome | 0.8 (1.9) | 1.2 (3.0) | 1.2 (3.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) – Manual data elaboration | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 0.5 (1.6) | 0.5 (1.6) | 0.5 (1.6) | |

| Radiology technician | |||||||

| # professionals | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0.9 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.0) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) - Patient interview | 0.8 (1.9) | 1.4 (3.0) | 2.3 (4.8) | 5.6 (3.5) | 8.1 (5.7) | 12.3 (6.5) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) - Exam execution | 1.5 (3.2) | 2.7 (5.3) | 3.5 (6.9) | 10 (4.7) | 15.7 (3.9) | 21.5 (5.8) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) - Reporting and communication of the outcome | 0.4 (1.4) | 0.8 (2.8) | 1.2 (4.2) | 1.5 (3.4) | 2.0 (4.2) | 2.5 (5.4) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) – Manual data elaboration | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5.5 (5.0) | 9.0 (6.1) | 12.5 (9.8) | |

| Resident | |||||||

| # professionals | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.5 (0.5) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) - Patient interview | 1.2 (2.2) | 2.2 (3.8) | 2.7 (4.8) | 1.6 (2.4) | 2.6 (3.5) | 5 (6.2) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) - Exam execution | 1.9 (3.3) | 3.1 (5.2) | 4.6 (7.8) | 2 (4.8) | 4.2 (6.6) | 6 (8.4) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) - Reporting and communication of the outcome | 0.9 (2.8) | 1.4 (3.0) | 2.3 (4.8) | 1.6 (3.3) | 2.3 (4.8) | 3.5 (6.7) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) – Manual data elaboration | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 2.0 (4.8) | 3.5 (6.7) | 5.0 (8.5) | |

| Other healthcare personnel | |||||||

| # professionals | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.4 (0.7) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) - Patient interview | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.1 (0.3) | 1.1 (3.1) | 2.0 (4.8) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) - Exam execution | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.4 (1.4) | 0.8 (2.8) | 0.5 (1.6) | 1.0 (3.2) | 1.5 (4.7) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) - Reporting and communication of the outcome | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 1.0 (2.1) | 1.0 (2.1) | 2 (4.8) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) – Manual data elaboration | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | |

| Administrative staff | |||||||

| # professionals | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.6 (0.5) | 0.9 (0.3) | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.8 (1.1) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) - Exam booking and payment | 2.0 (2.5) | 3.6 (4.2) | 5.6 (5.8) | 5.2 (4.5) | 11.2 (8.8) | 18.2 (17.3) | |

| Time dedicated (in minutes) - Exam reporting | 1.5 (3.2) | 2.1 (4.2) | 2.3 (4.8) | 2.5 (4.9) | 4.5 (6.9) | 6.0 (9.1) | |

Note. n.a.: not applicable.

Supplementary Table 3.

- Gross wage of professionals

| Gross wage (2019) | Gross wage (2021) | Wage per minute (2021) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinician | € 81,745 | € 84,197 | € 0.878 |

| Nurse | € 33,973 | € 34,992 | € 0.365 |

| Radiology technician | € 33,621 | € 34,630 | € 0.361 |

| Resident | € 25,500 | € 26,265 | € 0.274 |

| Other healthcare personnel | € 27,259 | € 28,077 | € 0.293 |

| Administrative staff | € 28,445 | € 29,298 | € 0.305 |

Notes:

- On the basis of the information provided in the CCNL, we considered 5 working days per week, with a working time of 7 hours and 12 minutes per day (i.e., 432 minutes per day). In 2021, considering all the holidays and days of annual leave, we estimated a total of 222 working days. Overall, this translates into 95,904 working minutes, corresponding to approximately 1,598 working hours. Using these data, we computed the wage per minute of each professional.

- In estimating the wages of all professionals except residents, we averaged the wage reported in Conto Annuale for IRCCS, policlinics and local health authorities. For residents, we averaged the two different wages established by law according to seniority (€25,000 for the first two years of specialization, €26,000 for the remaining years).

Supplementary Table 4.

- Unit cost of instrumental exams and laboratory tests

| Unit cost | |

|---|---|

| Instrumental exams | |

| CT scan | € 77.67 |

| Magnetic resonance | € 115.80 |

| X-ray of the dorsal-lumbar spine | € 34.60 |

| Laboratory tests - I level | |

| 24-hour urinary calcium | € 1.13 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) | € 1.04 |

| Calcemia | € 1.13 |

| Complete blood count | € 3.17 |

| Creatininemia | € 1.13 |

| Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) | € 1.95 |

| Phosphorus | € 1.46 |

| Protidemia (fraction) | € 4.23 |

| Laboratory tests - II level | |

| Ionized calcium | € 1.13 |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) | € 5.46 |

| Parathyroid Hormone (PTH) | € 18.92 |

| 25-Hydroxy Vitamin D | € 15.86 |

| Overnight dexamethasone suppression test | € 7.79 |

| Serum immunofixation | € 20.88 |

| Urine immunofixation | € 20.88 |

| Anti-transglutaminase antibodies (ATA) | € 9.98 |

Supplementary Table 5.

- Total time dedicated to training (in minutes) by each healthcare professional

| REMS mean (SD) | DXA mean (SD) | REMS - DXA mean (p-value) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professional figure | Most conservat ive scenario (L) | Base-case scenario (M) | Least conservati ve scenario (H) | Most conserva tive scenario (L) | Base-case scenario (M) | Least conserva tive scenario (H) | Most conservati ve scenario (L) | Base-case scenario (M) | Least conservati ve scenario (H) |

| Clinician | 158.1 (405.2) | 307.3 (811.9) | 1,105.4 (3,282.3) | 592.0 (1,323.2) | 848 (1,760.9) | 1,081.0 (2,179.9) | -433.9 (n.s.) | -540.7 (n.s.) | 24.4 (n.s) |

| Nurse | 3.5 (9.0) | 5 (13.2) | 53.1 (133.1) | 16.0 (26.3) | 24 (42.0) | 31.0 (59.0) | -12.5 (n.s.) | -19.0 (n.s.) | 22.1 (n.s) |

| Radiology technician | 9.2 (22.5) | 31.5 (64.3) | 46.2 (95.4) | 747.0 (1361.5) | 1,078 (1,866.2) | 1,949 (2,642.4) | -737.8 (n.s.) | -1,046.5 (n.s.) | -1902.8 (0.016) |

| Resident | 120 (415.0) | 271.5 (824.0) | 572.3 (1,652.6) | 16.0 (38.6) | 84 (152.8) | 133.0 (234.3) | 104.0 (n.s.) | 187.5 (n.s.) | 439.3 (n.s) |

| Other healthcare personnel | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 73.8 (266.3) | 6.0 (19.0) | 12 (37.9) | 36.0 (113.8) | -6.0 (n.s.) | -12.0 (n.s.) | 37.8 (n.s) |

| All professionals | 290.8 (815.9) | 615.4 (1624.4) | 1,850.8 (4,894.1) | 1,377.0 (2643.9) | 2,046.0 (3546.7) | 3,230.0 (4,445.7) | -1,086.2 (n.s.) | -1,430.6 (n.s.) | -1,379.2 (n.s) |

Note. n.s.: not significant. Since the p-value is also affected by the sample size (the smaller the sample size, the higher the p- value), we should be careful in interpreting the lack of statistical significance of the difference in estimates (as it may be driven by the low number of observations)

Supplementary Fig. 1.

- Sensitivity analysis – REMS

Supplementary Fig. 2.

- Sensitivity analysis – DXA

Level I exams: VES; complete blood count; Fractional protidemia; Calcemia; Phosphorea; Total alkaline phosphatase; Creatininemia; Calciuria of 24 h.

Level II exams: Ionized calcium; TSH; Serum parathyroid hormone; Serum 25-OH-vitamin D; Cortisolemia after overnight suppression test with 1 mg dexamethasone; Total testosterone in males; Serum and/or urinary immunofixation; Anti-transglutaminase antibodies; Specific tests for associated pathologies (e.g. ferritin and % transferrin saturation, tryptase, etc.)

Level II exams are recommended when there is suspicion of secondary forms of osteoporosis and their choice must be based on the anamnestic and clinical evaluation of the individual patients.

References

- 1.Consensus development conference. Consensus development conference: diagnosis, prophylaxis, and treatment of osteoporosis. Am J Med. 1993;94(6):646–650. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90218-E. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cummings SR, Melton LJ. Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet. 2002;359(9319):1761–1767. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08657-9. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lane NE. Epidemiology, etiology, and diagnosis of osteoporosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(2)(suppl):S3–S11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.08.047. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salari N, Ghasemi H, Mohammadi L et al. The global prevalence of osteoporosis in the world: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16(1):609. doi: 10.1186/s13018-021-02772-0. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Osteoporosis Foundation, Fondazione FIRMO. OSSA SPEZZATE, VITE SPEZZATE: un piano d’azione per superare l’emergenza delle fratture da fragilità in Italia. [Accessed September; 2022 ];2017 Online [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pazianas M, Miller P, Blumentals WA, Bernal M, Kothawala P. A review of the literature on osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with osteoporosis treated with oral bisphosphonates: prevalence, risk factors, and clinical characteristics. Clin Ther. 2007 Aug;29(8):1548–1558. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.08.008. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borgström F, Karlsson L, Ortsäter G et al. International Osteoporosis Foundation. Fragility fractures in Europe: burden, management and opportunities. Arch Osteoporos. 2020;15(1):59. doi: 10.1007/s11657-020-0706-y. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clynes MA, Harvey NC, Curtis EM, Fuggle NR, Dennison EM, Cooper C. The epidemiology of osteoporosis. Br Med Bull. 2020;133(1):105–117. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldaa005. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khosla S, Hofbauer LC. Osteoporosis treatment: recent developments and ongoing challenges. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017 Nov;5(11):898–907. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30188-2. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris CA, Cabral D, Cheng H et al. Patterns of bone mineral density testing: current guidelines, testing rates, and interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(7):783–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30240.x. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khosla S, Shane E. A crisis in the treatment of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31(8):1485–1487. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2888. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernlund E, Svedbom A, Ivergård M et al. Osteoporosis in the European Union: medical management, epidemiology and economic burden. A report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA). Arch Osteoporos. 2013;8(1):136. doi: 10.1007/s11657-013-0136-1. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.International Osteoporosis Foundation. How fragile is her future? [Accessed September; 2022 ];2000 Online [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine JP. Identification, diagnosis, and prevention of osteoporosis. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(6)(suppl 6):S170–S176. PubMed [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanis JA. Diagnosis of osteoporosis and assessment of fracture risk. Lancet. 2002 Jun 1;359(9321):1929–1936. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08761-5. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossini M, Adami S, Bertoldo F et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis, prevention and management of osteoporosis. Reumatismo. 2016 Jun 23;68(1):1–39. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2016.870. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caffarelli C, Pitinca MDT, Francolini V, Alessandri M, Gonnelli S. REMS technique: future perspectives in an academic hospital. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2018;15(2):163–165. Online [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Paola M, Gatti D, Viapiana O et al. Radiofrequency echographic multispectrometry compared with dual X-ray absorptiometry for osteoporosis diagnosis on lumbar spine and femoral neck. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30(2):391–402. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4686-3. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diez-Perez A, Brandi ML, Al-Daghri N et al. Radiofrequency echographic multi-spectrometry for the in-vivo assessment of bone strength: state of the art-outcomes of an expert consensus meeting organized by the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO). Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019;31(10):1375–1389. doi: 10.1007/s40520-019-01294-4. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casciaro S, Peccarisi M, Pisani P et al. An advanced quantitative echosound methodology for femoral neck densitometry. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2016;42(6):1337–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2016.01.024. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conversano F, Franchini R, Greco A et al. A novel ultrasound methodology for estimating spine mineral density. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2015;41(1):281–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.08.017. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adami G, Arioli G, Bianchi G et al. Radiofrequency echographic multi spectrometry for the prediction of incident fragility fractures: A 5-year follow-up study. Bone. 2020;134:115297. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2020.115297. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cortet B, Dennison E, Diez-Perez A et al. Radiofrequency Echographic Multi Spectrometry (REMS) for the diagnosis of osteoporosis in a European multicenter clinical context. Bone. 2021;143:115786. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2020.115786. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sistema nazionale per le linee guida. Diagnosi, stratificazione del rischio e continuità assistenziale delle Fratture da Fragilità. [Accessed September; 2022 ];2021 Online [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colson AR, Cooke RM. Expert elicitation: using the classical model to validate experts’ judgments. Rev Environ Econ Policy. 2018;12(1):113–132. doi: 10.1093/reep/rex022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bojke L, Soares M, Claxton K et al. Developing a reference protocol for structured expert elicitation in health-care decision-making: a mixed-methods study. Health Technol Assess. 2021;25(37):1–124. doi: 10.3310/hta25370. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soares MO, Bojke L. Expert elicitation to inform health technology assessment. In: Dias LC, Morton A, Quigley J, editors. Elicitation: the science and art of structuring judgement. Springer International Publishing; 2018. pp. 479–494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bojke L, Soares MO, Claxton K et al. Reference case methods for expert elicitation in health care decision making. Med Decis Making. 2022;42(2):182–193. doi: 10.1177/0272989X211028236. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. SAGE Publications. 2016 Online [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ministero della Salute. Nomenclatore dell’assistenza specialistica ambulatoriale. [Accessed September; 2022 ]; Online [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conto annuale – Costo del lavoro. [Accessed September; 2022 ]; Online [Google Scholar]

- 32.Determinazione del numero globale dei medici specialisti da formare per il triennio 2020/2023 ed assegnazione dei contratti di formazione medica specialistica alle tipologie di specializzazioni per l’anno accademico 2020/2021 (GU Serie Generale n.229 del 24-09-2021). [Accessed September; 2022 ]; Online [Google Scholar]

- 33.Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT). Rivaluta; [Accessed September; 2022 ]. Online [Google Scholar]

- 34.CCNL 2016-2018 del Comparto Sanità. [Accessed September; 2022 ]; Online [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (AIFA). Nota 79. [Accessed September; 2022 ]; Online [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (AIFA). Nota 96. [Accessed September; 2022 ]; Online [Google Scholar]