Abstract

Recent work on health system strengthening suggests that a combination of leadership and policy capacity is essential to achieve transformation and improvement. Policy capacity and leadership are mutually constitutive but difficult to assemble in a coherent and consistent way. Our paper relies on the nested model of policy capacity to empirically explore how health reformers in seven Canadian provinces address the question of policy capacity. More specifically, we look at emerging representations of policy capacity within the context of health reforms between 1990 and 2020. Based on the exploration of the scientific and grey literature (legislation, annual reports of Ministries, agencies and organizations, meeting minutes, press, etc.) and interviews with key informants (n = 54), we identify how policy capacity is considered and framed within health reforms A series of core dilemmas emerge from attempts by each province to develop policy capacity for and through health reforms.

Keywords: health reforms, policy capacity, Canada, policy instruments, health system strengthening

The search for ways to adapt or improve health systems is high on the agenda of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) governments. Debates about the need for health policy changes proliferate due to escalating costs, emerging priorities or major health crisis like coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Assessments of the benefits of past reforms have been mixed or below expectations in many countries (Hunter, 2011). Canada is no exception, and it has been difficult to achieve satisfactory improvements despite successive waves of reform in various provinces (Lazar et al., 2013; Tuohy, 2018). For Lazar and colleagues (Lazar et al., 2013), reforms or policy reforms consist in deliberate attempts by governments to substantially change health policies in order to attenuate health system dysfunctions or face policy challenges such as escalating costs. Provinces and territories in Canada manage, organize, and, to a significant extent, each finance their own healthcare systems, within the parameters of the federal Canada Health Act (1984). Healthcare services are funded mainly by taxation in each province, with the federal government contributing about 24% through the Canada Health Transfer, provided to provinces on a per capita basis (Allin et al., 2020). Federal transfer payments are conditional on provinces respecting the Canada Health Act.

Many reasons have been put forward to explain the relative difficulty in achieving health reforms in Canada. Structural inertia is often associated with the Canada Health Act, which puts universal coverage of hospital and medical care at the center of systems across Canada. A recent report commissioned by Health Canada (Forest & Martin, 2018) identifies persistent vulnerabilities, including an outdated basket of publicly funded services, inadequate access to comprehensive primary care, poor digital information systems and data governance, lack of effective means of spreading innovations, inadequate patient and public engagement, and persisting health disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians. While political turf is often used to explain and excuse tolerance for these vulnerabilities, questions about policy capacity have become louder in recent reports (Advisory Panel on Healthcare Innovations, 2015; Forest & Martin, 2018). Policy capacity refers to the ability to “marshal the necessary resources to make intelligent collective choices” (Painter & Pierre, 2005), but also to implement preferred choices of action (Davis, 2000). The framework proposed by Wu et al. is useful as it specifies “what constitutes policy capacity” and how “existing and potential resources and skills can be combined to augment and deploy it” (Wu et al., 2015, p. 166).

In this paper, we empirically probe the manifestations of policy capacities within the context of health reforms in seven Canadian provinces. Our analysis reveals how challenging it is to ensure a comprehensive, balanced, and consistent stock of policy capacities over time to support health reforms. Findings further our understanding of the contribution of policy capacity to health system strengthening (HSS) and transformation. The health system is understood as the institutions, people, and resources that participate in the delivery of healthcare services.

Health system is used here to describe how health care is organized at national, regional, or local levels. It involves organizational units of people, institutions, and resources that deliver healthcare services to meet the primary, preventive, curative, and palliative needs of patients and population groups (World Health Organization, 2000). Key dimensions of health systems are leadership and governance; financing; the workforce, products and services involved in healthcare delivery; and health information systems (World Health Organization, 2007).

Conceptual background: policy capacity, reforms, and health system strengthening

Most work on policy capacity has focused on definitional issues and on identifying the construct’s multiple dimensions (Wu et al., 2015). It is now recognized that policy capacity is more than just a government’s analytical capacity. It incorporates a mix of elements, ranging from political savvy to operational know-how to scientific and technical knowledge, that support the whole policy cycle (Denis et al., 2015; Forest et al., 2015).

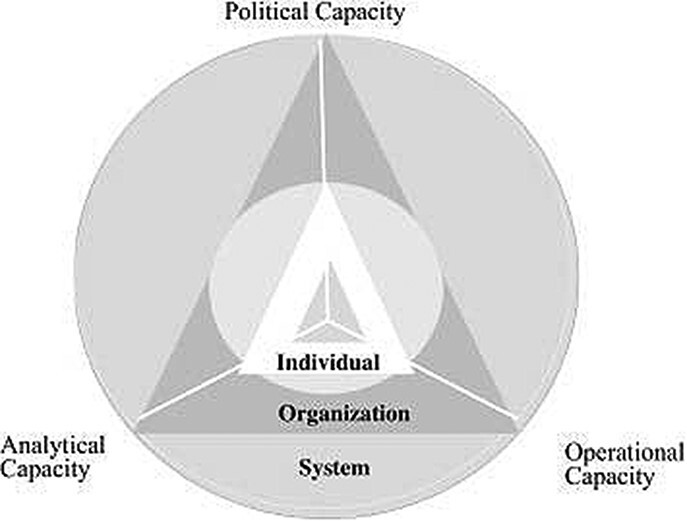

The model developed by Wu and colleagues (Wu et al., 2015) proposes a 3 × 3 matrix where capacities are clustered around political, operational, and analytical capacities at three levels of analysis, namely system, organization, and individual (see Appendix A). At each level, analytic capacities help assure that policies contribute to goal attainment; operational capacities involve securing the resources to implement and evaluate reforms; and political capacities help assure support for policy actions (Wu et al., 2015). More precisely, analytical capacities relate to knowledge generation, mobilization, and use to strengthen health policies (Mukherjee & Bali, 2019) and refer to the cognitive dimension of policy-making where actors accumulate data and evidence through social exchanges, develop and draw on expertise, and adjust policy beliefs and instruments in order to deal with collective problems (Moyson et al., 2017; Tamtik, 2016). Operational capacities deal with accountability, resources, and know-how to translate policy intentions in concrete and novel organizational arrangements and practices to achieve policy goals (Mukherjee & Bali, 2019). Political capacities aim to mobilize concerned stakeholders and increase the acceptability and feasibility of health reforms (Mukherjee & Bali, 2019). These capacities develop and interact in complex ways, influenced by health system context and institutions (Gleeson et al., 2009; Hughes et al., 2015; Peters, 2015). It is important to note that the three types of policy capacities (political, analytical, and operational) are all activated within governments—at national, regional, or municipal levels depending on the structure of the health system—to support and drive policy change and reforms. Some health systems have, in undertaking reforms, historically paid more attention to supporting the development of capacities for improvement at the point of care (Bohmer, 2016), while others have invested more in capacities at the system level to monitor and assess system performance (Kuhlmann & Burau, 2008). Overall, policy capacities are necessary conditions and resources to drive health reforms, but assembling an appropriate mix at scale appears challenging.

Health reforms are defined as deliberate and significant policy changes to the structures and processes of publicly funded health systems with the objective of improving their functioning or performance (adapted from Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2017). Health reforms differ from minor changes or local initiatives within care delivery organizations to improve care and services. In this paper, they represent a shift in policy orientation promoted by a government through various reformative templates that are proposed, debated, and adopted by parliaments in the various Canadian jurisdictions (Usher et al., 2020).

Three contextual elements influence the development and deployment of policy capacities to support health reforms, defined as substantial policy changes adopted by governments.

A first important element of context relates to political regime (Bossert & Mitchell, 2011; Greer et al., 2020; Roman et al., 2017). When responsibilities are shared among federal and provincial or state governments, more consideration must be given to coordination of policy capacities. Canadian provinces and territories are responsible for governing and funding each of their health systems, which requires comprehensive and relevant policy capacity. Federal governments can, to some degree, compensate a lack of state (province) capacity (Forest & Helms, 2017) by promoting national policy capacities and standards (Forest & Martin, 2018). The legitimacy of these respective levels of government and their level of collaboration (Woo et al., 2015) will influence their ability to develop policy capacity.

A second important element relates to predominant policy frames (Jones & Exworthy, 2015) that inhabit health reforms and have consequences for the understanding of what is needed in terms of policy capacity to support reforms. Predominant policy frames reveal how policy-makers select, define, and understand situations that are perceived as problematic. Policies or reforms are influenced by predominant beliefs about what needs to be fixed and what is working well in health systems (Brown, 2012). Bacchi (2010) has developed the What is the problem represented to be approach (WPR approach), which underlines how policies carry specific representations of problems that affect what will be decided and done to alleviate so-called problematic social situations (Bletsas & Beasley, 2012). For Bacchi (2010, 2015, 2016), policies produce meanings that influence how social situations will be considered as problematic or not and the way they will be translated in problems that drive policy-making. For example, since the mid-1970s, health policy debate in high-income countries has been structured around a dichotomy between producing health care and producing health (Evans & Stoddart, 2017). The producing health perspective incorporates a specific representation of health and well-being and favors types of policy intervention aligned with a specific view of health in society. While considered progressive within the health policy field, this approach has limitations in its representation of health and equity in society (Bacchi, 2016). Alternatively, the producing care approach to health system design focuses on the delivery of medical and health services and care to a population, without much attention to broader social determinants of health and well-being. As we will see, Canadian health systems aspire within reforms to somewhat blend these two broad policy frames to guide policy changes, and this has implications for the development of policy capacities.

Bacchi’s work (Bacchi, 2010, 2016) portrays policy-making as a place where governments create problems with consequences. Health reforms offer a privileged viewpoint to document the framing of problems and their policy consequences. As they make policy, governments define what is and is not considered as elements of reform, and solidify the conception of subjects of reforms (i.e., healthy individuals or communities) and the expected impact of reforms. In this paper, we anticipate the following relationships between problem definition, as conceived by Bacchi (2010), and policy capacities and reforms. On the one hand, policy capacities within governments, including professional and policy experience and the social position of key policy actors, will influence how social situations are framed and interpreted as problems. On the other hand, the way problems are defined will influence perceived needs in terms of policy capacities within governments and policy processes. Predominant views on problems and viable solutions vary across disciplines and political ideologies (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2017). Policy leaders shape representations of problems and solutions, along with, indirectly, the set of policy capacities that are valued, considered, and mobilized to support policy changes. We will revisit these issues in the discussion section of this paper in light of our empirical findings.

A third element lies in the prevailing view of the policy process in terms of distributed capacities within broad policy networks (Rhodes, 2006). For example, policy design can be conceived as a complex social exchange process with input and feedback from a variety of traditional and non-traditional policy actors (Campbell, 2011). Here, policy capacity implies prospective analysis within policy design to assess political feasibility and acceptability (Blanchet & Fox, 2013). Health system reforms in the Canadian context are developed in a context where autonomous levels of government (federal and provincial) attempt to promote their own norms and rules. Policy dynamics within this context are characterized by polycentrism in policy-making (Gautier et al., 2018; Ostrom, 2010) with potential tensions or joint efforts between different levels of government. Moreover, when engaging in health reforms, federal and provincial governments mobilize (or not) a diversity of non-traditional policy actors such as professional associations and advocacy groups, taking into account distributed expertise, legitimacy, and capacities for health policy-making. In this context, policy entrepreneurs may engage in health reforms to gain influence on policy-making and promote policy innovations (Gautier et al., 2018; Tuohy, 2012). Depending on the openness of the policy process, health reforms can reflect state-centered activity, or be influenced by a complex mix of actors and organizations (Cairney, 2019). Within health reforms, governments may look to or mobilize policy capacities from a broader or narrower range of organizations and networks. Later in this paper, we will discuss the role of policy networks in the development and mobilization of policy capacity in our empirical cases.

Overall, development and deployment of policy capacity in health system reforms will be influenced by a complex mix of situational elements that shape policy work across the whole policy cycle. Characteristics of political regimes (such as federalism), predominant political ideologies, and allegiances, and the relative openness of the policy process will orient attention to and use of policy capacity. Our research looks at policy capacities in health reforms as dynamic entities that are shaped by these situational elements.

Methodology

Seven provinces—Nova Scotia, Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia—were selected as jurisdictions that pursued distinctive reforms between 1990 and 2020 (Usher et al., 2020). Two major criteria were used to identify provinces: (1) the approach to reforms is more radical than incremental and (2) the reforms target the whole health system, as opposed to particular targets, such as governance, delivery, or financing (Lazar et al., 2013).

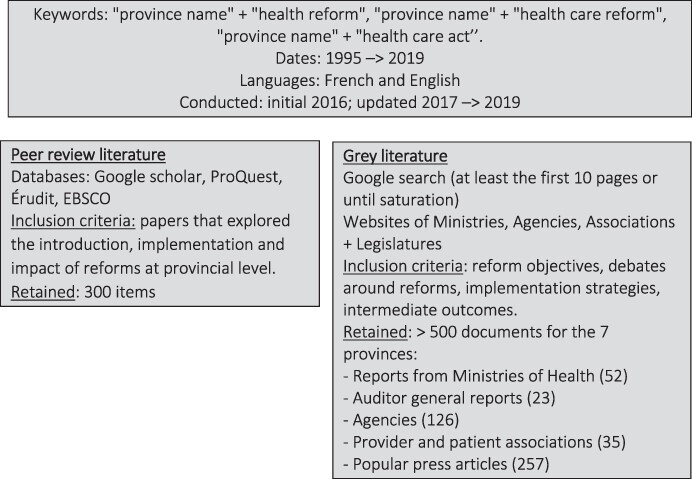

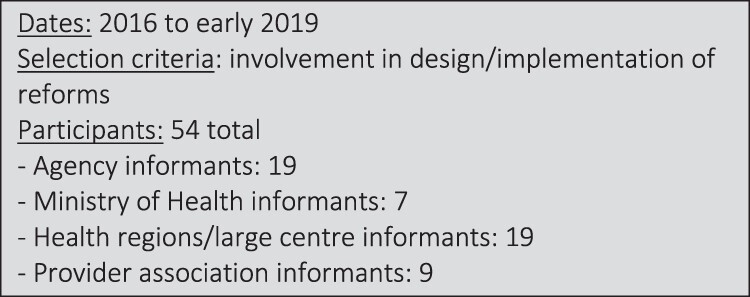

A step-wise and sequenced approach was used to develop longitudinal case studies of reforms in each province to identify priority objectives and strategies adopted by governments to improve their health systems. The time period (roughly 2000 to early 2019) was marked by emerging challenges (i.e., increased prevalence of chronic disease) and possibilities (i.e., advances in information technology) and a preoccupation with safety, quality, and performance. We developed initial narratives and timelines of health reforms based on available peer-review and grey literature (legislation, annual reports of Ministries, agencies and organizations, meeting minutes, press, etc.). Appendix B provides details on the search strategy for documents and literature. The narratives enabled us to identify different phases of reform in each province, essentially groupings of critical events over a given period, and factors that prompted passage from one reformative phase to another. We then conducted interviews with key informants in each province (54 interviews total) to validate and add depth to case narratives. Interview participants were selected as actors in executive positions in government, para-governmental agencies, delivery organizations, and provider groups who could provide a particular perspective on reforms. Identification was guided by the case narrative as well as by key informants with policy experience in each province who reviewed the case narratives. Interviews enhanced the case narratives with experience-based perspectives on reforms, what Molloy et al. call “testimony” (Molloy et al., 2016, p. 16). Appendix B describes the number of interviews across provinces per category of respondents, along with other main sources of data. A case narrative consists in a detailed description of each main phase of reforms, focusing on key actors, key reformist propositions, perceived challenges, and anticipated impact. A typical case narrative is over 100 pages.

We then used these narratives of reforms to identify and code manifestations of policy capacity according to the three main capacities and levels of analysis identified by Wu et al. (2015). Manifestations of policy capacity are presented in Table 1 and the “Manifestations of policy capacity” section. We include a few illustrative quotations in the “Empirical findings” section to exemplify empirical markers of the policy capacities in the Wu et al. typology; a broader selection of quotations supporting each of Wu et al.’s nine typology components is presented in Appendix C. More specifically, we present manifestations of policy capacities under each generic capacity of Wu et al.’s (2015) model and then underline major manifestations of capacities according to the three levels of analysis: system, organization, and individual. Table 1 summarizes manifestations of the three forms of capacities across these three levels of analysis. Results are pooled across provincial jurisdictions to illustrate main trends in the development of policy capacities within health reforms across Canada.

Table 1.

Policy capacity within health reforms in Canada.

| System level | Organizational level | Individual level | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical capacity | Commissions with input from the public and stakeholders (mid-1990s to early 2000s): Romanow, Kirby (Fed); Fyke (SK); HRSC (ON); Clair (QC); Mazankowski (AB) Targeted consultations/advisory panels (after 2005) make actionable recommendations on specific policy challenges, sometimes looking at examples in other jurisdictions (IHI in USA, NHS England) Examples: Baker report on high-performing health systems (2007); Castonguay Report on health system sustainability in QC (2008); Drummond review in Ontario of public administration (2012); SK Advisory Panel on Health System Restructuring (2016); Peachy Report in Manitoba on consolidation (2017); Ernst and Young report in Alberta on power rebalancing and cost (2019–2020); ON Premier’s Council on Improving Healthcare and Ending Hallway Medicine (2019) Auditor General (AG) reports Examples of influence: SK (2015) AG report cast doubt on the Lean program’s return on investment; ON (2019) The AG’s findings that HQO was unable to monitor adoption of its clinical standards helps justify its integration into Ontario Health. Watching other provinces Example: NS adopts zone structure within single health authority after watching AB experience |

Performance monitoring and reporting Examples: ECFAA QIPs and hospital report cards (ON), control rooms (QC), WTIS (AB), PCN Panel reports (AB); Saskatchewan Surgical Initiative (SK) Western Canadian Wait List Project (federal funding) Patient input into improvement efforts Examples: Patient/Family Advisory Councils (BC, AB, SK); patient-centred measurement steering committee 2003 (BC); User Committees (QC); CHB role in decision-making (NS) Patients’ First Act (ON); Accreditation Canada standards (federal) Learning from other provinces and jurisdictions (CCN) and from leading centers/jurisdictions abroad (i.e., IHI; England NHS; Virginia Masson) |

Mobilize clinical and policy leaders Examples: Cy Frank’s model at Bone & Joint Institute informed SCNs (AB) Recruiting international experts Examples: Don Berwick on first SK HQC Board; Stephen Duckett as first AHS CEO Use of private consultants Example: Lean initiative (SK and QC) Narratives of patient and provider experience Examples: patients going to USA for radiation treatment prompted creation of CCO (ON); BC Fanny Albo case prompted inquiry into LTC (BC); Facebook post by nurse prompted efforts to address nurse staffing ratios (QC) |

| Partnering with physicians Examples: tripartite (gov, HA, physicians) type agreements (BC, AB, NS); inclusion of physicians in government planning of reforms (ON 2010 ECFAA; MN 2012 Medical Leadership Council; SK 2018 physicians on teams guiding RHA consolidation) Create arm’s length agencies |

|||

| Examples: ICES (ON), MCHP (MN), INESSS, AQESSS, CSBE (QC), Quality Councils (many provinces); CADTH, CIHI, CFHI, CPSI, CCA (Federal) |

|||

| Political capacity | Public consultation and commissions that give citizens and stakeholders a voice in reform processes Formal agreements with physician associations Examples: trilateral agreement (AB); GPSC (BC); physician participation in transition committee to SHA (SK) Negotiation with health worker unions Creation of intermediate governance bodies and arm’s length agencies Examples: LHINs (ON); Agencies, AQESSS, CSBE (QC); RHAs (persist in BC and MN); quality councils (many provinces) Learning provided to all provincial actors Example: Lean training (SK) |

Legislative instruments Examples: laws that give provincial governments power to appoint CEOs and/or boards of organizations; Excellent Care for All Act (ON), Provincial Health Authority Act (SK); RHA Act (AB); Medicare Protection Act (BC); Heath Authorities Act (BC and NS), Bill 10 and 20(QC) Targeted federal funding Examples: Primary Health Care Transition Fund; or Chronic Disease Innovation Fund Citizen and community advisory bodies Examples: PFCC Guiding Coalition (SK); Patient and Family Advisory Groups (AB); Community Health Boards (NS) National campaigns Examples: CFHI, CIHI, Patient Safety Institute; Choosing Wisely Development of collaboration between MoH and stakeholders Examples: Committees to align Ministry plan and physician contracts (AB, BC) |

Long-tenured Premiers

many provinces see three terms of same political party Experience and implementation-based experts Examples: Jean Rochon, Ken Fyke, Dan Florizone, Matt Anderson, McCann Media attention Examples: nurse staffing problems (SK, QC); system shortcomings (ON cancer radiation care in USA) Inter-provincial movement of experts Examples: Andreas Laupacis on first AHS Board; Ben Chan first HQO CEO after leading SK HQC Participation of provincial experts on national agencies Examples: Sinclair on Infoway Board |

| Operational capacity (In the case of operational capacity, identical capacities are found at the organizational and individual levels of analysis) |

Systemwide policy on performance Examples: Health Results Team and ECFAA (ON); salles de pilotage indicators and GMF targets (QC), wait times strategies (many provinces) Agencies or structures to lead and coordinate improvement efforts Examples: quality councils (many provinces), GPSC (BC), PCN and SCN (AB); FHT (ON); AQESSS, RUIS (QC), CHFI, CPSI (Federal) Agencies to support evidence-based decisions Examples: ICES (ON), INESSS (QC), MCHP (MN), Infoway, CADTH and CIHI (Fed) Centralization of governance structures Bill 10 (QC); single HA (AB, SK, NS), Ontario Health (ON) Private consultants Example: Lean implementation (SK) Incubators to try strategies before broader health system application Example: CCO (ON) |

IT infrastructure and comprehensive, timely, comparable data For: harmonized clinical protocols and indicators; indicator tracking and monitoring, practice improvement Self-management programs comprehensive in BC; somewhat available in other provinces Community-driven prevention-promotion only in NS Provider structures to increase provincial ability to direct/influence their activities Examples: PCN (AB), GMF (QC), GPSC (BC) CCAC, FHT (ON) Scope of practice expansion Examples: NPs, pharmacists, emergency services Contracting with private providers Examples: surgical services (many provinces) Tools to better navigate care Examples: telephone triage and information services (all provinces) Coordination/integration among providers Examples: HealthLinks (ON), CI(U)SSS (QC), SCN (AB) Leaders with operational experience Examples: Brown in measurement and improvement (ON) Florizone (Lean), Hudson in academic health (ON), Ducket in health economics (AB), Rochon in population health (QC) |

|

VP: Vice President; DHAs: District Health Authorities; PFCC’: and Fam Patientily Centered Care; HRSC: Health Services Restructuring Commission; SCNs: Stratgic Clinical Networks; HQC: Health Quality Council; AHS: Alberta Health Services; PCNs: Primary Care Networks GMF: Group Medecin Famille; CCAC: Community Care Access Centre; FHT: Family Health Teams; GPSC: General Practice Services Committee; NP: Nurse Practioner; CISSS/CIUSSS: Centres Intégrés de Santé et de Services Sociaux/Centres Intégrés Universitaires de Santé et de Services Sociaux; ICES: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; INESSS: Institut national d’excellence en santé et en services sociaux; CADTH: Canadian Agency for Drugs & Technologies in Health; CIHI: Canadian Institute for Health Information; HA: Health Authorities; CFHI: Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement; CPSI: Canadian Patient Safety Institute; RUIS: Réseau universitaire intégré de santé; AQESSS: Association québécoise des établissements de santé et de services sociaux; CPAR : Central Patient Attachment Registry; ECFAA: Excellent Care for All Act; QIPs: Quality Improvement Plans; WTIS: Wait Time Information System RHA; LHINs: Local Health Integration Networks; HQCA: Health Quality Council of Alberta; HQO: Health Quality Ontario; CQCO: Cancer Quality Council of Ontario; OHQC: Ontario Health Quality Council; OHA: Ontario Hospital Association; IWK Health Authority: Izaak Walton Killam Health Authority; MCHP: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy.

The outcomes of health reforms represent a moving target that involves multiple interconnected factors. To capture the idea of continuous improvement, the World Health Organization (WHO) has adopted the idea of HSS to track country efforts that contribute to moving in a desired direction. To assess the influence of policy capacity on HSS in Canada, we pay attention to instances where policy capacities are conducive to changes in the building blocks identified in the WHO model: service delivery, health workforce, information, medical products, vaccines and technologies, financing, leadership, and governance. We work retrospectively to link observed policy shifts in these areas with policy capacity manifested through reforms. Our assessment reveals some significant patterns in the relationship between attention to and mobilization of policy capacity and intermediary outcomes of reforms. Assessment of the impact of policy capacity on HSS is presented in Table 2 and the “Impact of policy capacity on HSS” section.

Table 2.

Health system strengthening and policy capacity.

| Health system strengthening | |

|---|---|

| Analytical capacity | At the national level, Commissions and health forums influenced policy shift and ideas for reform, notably reinforcing universal health coverage. Two health accords were signed to improve wait times, primary care, and drug coverage. Primary healthcare became a main focus of reforms (AB, MB, ON, QC). |

| Following Commission recommendations, the federal government invested in specific programs. The Health Transition Fund and Primary Health Care Transition Fund influenced primary care strategies (AB, MB, ON, QC). | |

| At the provincial level, Commissions and consultations helped generate information to support decision-making and expand policy options, with influence on the content of reforms, notably primary care and physician engagement (Health and Social Service Centres and family medicine groups in Quebec, primary care networks in Manitoba and BC). MCHP data and information helped frame policy questions (120119_002). Alberta’s “Putting People First” consultation (2010) fed the “Becoming the best” (2012) 5-year action plan and Patients First Strategy (2015). | |

| Commission or advisory body recommendations also influenced structural changes in health reform (move from regionalization to centralization through consolidation of Health Authorities) to improve coordination and consolidate decision-making (AB, SK, NS) | |

| Political capacity | Various stakeholders participated in formulating policy and reform strategies by providing informed opinion and identifying practical difficulties. Citizens were included in system and organization improvement efforts Health Quality Councils supported patient engagement in CQI (BC, AB, SK) and public consultations informed strategic direction (NS: The Renewal of Public Health in Nova Scotia: Building a Public System to Meet the Needs of Nova Scotians). |

| More collaborative and participatory relations with stakeholders served to define priorities together and co-design and co-deliver health services. Partnerships often involved reaching out to patients and communities. Efforts were made to reinforce connections with communities and citizens (SK, MB, ON, NS). | |

| Conflicts were managed through partnerships or agreements with professional associations: FMGs in QC were an innovation developed collaboratively by government and the union of GPs; Alberta Health partnered with Strategic Clinical Networks; the tripartite agreement between the AMA, AH, and RHAs helped establish the Primary Care Initiative (PCI) to encourage physicians to implement PCNs. | |

| Leaders spread a strategy from an organization to a whole province: RHA leader with experience in Lean became DM and drove development of province-wide Lean capacities (SK). | |

| Provincial agencies and health networks established partnerships: in ON’s HQO/LHIN agreements, medical leadership was actively involved in planning and quality improvement, and, HQO worked hard with the “O’s and A’s” (organizations and associations) to “focus our resources on their gaps” (HQOWM2). In AB, the Primary Care Initiative provided incentives for physicians to develop Primary Care Networks as an 8-year plan in collaboration with RHAs | |

| Operational capacity | Health system redesign efforts sought to establish a more comprehensive primary health care system: GACOs and Super Clinics to reduce wait times and use of ER in QC; productive government relationships with primary (PCN) and specialist (SCN) physicians to partner in designing new models of care in AB; Health Links and LHINs in ON along with expanded access to multidisciplinary primary care with FHTs; shared care mental health, Physician Integrated Networks and My Health Teams in MB |

LHINs: Local Health Integration Networks; HQO: Health Quality Ontario; MCHP: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy; FHT: Family Health Teams.

Empirical findings

In this section, we first describe the types of policy capacity—analytical, political, and operational—governments (policy-makers and politicians) develop and activate over time to support health system reforms. Situational factors influence the type of policy capacities governments focus on at any given time. As underlined in Wu et al.’s (2015) framework, policy capacities to support reforms can be activated at the system level (macro), at the organization or delivery level (meso), and at the individual level (micro), as with the introduction of informational infrastructure that enables clinical performance to be compared.

Manifestations of policy capacity

Analytical capacities within health reforms

We describe manifestations of analytical capacities in terms of the use of public commissions, public consultations, targeted reviews, and data infrastructure. We look at the development of analytical capacities at three levels of policy intervention—system, organization, and individual—and identify core analytical capacities that have been developed or deployed.

Commissions and consultations with input from concerned publics and stakeholders are analytical capacities mobilized by the federal government and several provinces between 1990 and 2005, with each resulting in an extensive report about changes required. Commissions are run by policy elites or leaders (individual policy capacity) and members are high-ranking civil servants, health professionals, and civil society actors, including unions in some cases. Such pluralism in policy-making interacts with the development of political capacity for reforms (see below).

Commissions generally supplement their expertise by commissioning fine-grained analysis from external researchers or experts, often from academia. The most extensive commission, the (federal) Romanow Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada (2001–2002), included 15 expert workshops and roundtables and 52 discussion papers. Commissions represent a kind of network approach to policy-making where government accepts the risk of being influenced by a plurality of actors and viewpoints. Commissions play a generative function without excessive political risks. Many commissions during this period are sponsored by center-left or social-democratic (labor) parties, and cross-fertilization is seen between federal and provincial governments. Saskatchewan’s Fyke Commission (2000) was initiated by Premier Roy Romanow, who then left provincial politics to head the federal Commission, which promoted similar ideas. Reformative ideas generated by Commissions can also propose competing directions for change. The Mazankowski report in Alberta (2000) proposed shrinking public services, while federal commissions around the same time (National Forum on Health and Romanow Commission) advocated investing in the public system.

After the mid-2000s, commissions with a broad mandate of reforming health systems give way to more targeted consultations and advisory panels around issues such as sustainability, integration, and quality of care. Analytical capacities mobilized in this period often draw on international agencies such as the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) in USA and National Health Service (NHS) England and more conservative political ideologies infused by New Public Management ideas (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2017). Identifying citizen expectations is a key objective in these reports, and a vocabulary of “patients first” “patient-centered” and “patient experience” appears in consultation reports and legislation. For example, Saskatchewan’s Patients First Review in 2009 had input from more than 4,000 citizens along with hundreds of healthcare providers and system leaders. As stated by an informant..“the Patients First Review really helped the system come together and make a commitment that patient- and family-centered care (PFCC) is what we want health care to be.. That was important. Out of the Review came the specific objective from the Ministry of Health to transform the experience for patients requiring surgery.. And from the surgical initiative we get to Lean. So, they’re all connected to me, but that’s how we get to a readiness for leaders to commit to a common improvement method” (Interview P3006).

Targeted reviews conducted by small advisory groups are mobilized to make actionable recommendations (see Table 1 for examples). Analytical capacity is often contracted out from government to consultants or organizations with allegiances compatible with the political party in power. Other types of review are not commissioned by governments, but originate from more progressive political positions or groups such as the BC Centre for Policy Alternatives and Institut de recherche et d’information socioéconomiques (IRIS) in QC. Auditor General reports on health system issues also become more influential during the 2000s.

Another important source of analytical capacity at the system level is found in national or provincial initiatives to expand the availability of comprehensive and timely data and the capacity to exploit these data to support health system improvement. This work was taken up by research institutes or data-driven agencies such as Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) in Ontario and Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP) in Manitoba or by arm’s length agencies, such as Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) at the federal level or Institut national d’excellence en santé et services sociaux (INESSS) in Quebec. Most provinces also created quality councils dedicated to developing standards and reporting variations in practice or utilization. Finally, broad national initiatives in research (i.e., Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR)’s Strategy for Patient-oriented Research, data analysis [Canadian Institute for Health Information—CIHI], and improvement strategies [Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement—CFHI]) aimed to increase capacity to exploit data for improvement. Challenges are evident in connecting these analytical capacities with system governance and infusing them into daily health system operations. While analytical capacity appears to be highly valued, provincial governments sometimes found the power of information politically problematic. Following comparative analysis that revealed shortcomings in some areas, for example, Quebec’s government attempted to abolish the office of the Health and Social Services Commissioner, an independent public agency (created earlier by the same government) in charge of providing public information on health system performance. Outcry from experts, providers, and citizens and the eventual reversal of the decision suggest that these capacities have become expected and essential.

Overall, earlier reforms seem more oriented toward discovering the right direction for policies through an open and well-informed policy process. The recent tendency is for a more restricted and selective (favoring political siblings) approach that is less generative, more targeted, and sometimes used to justify pre-determined options.

Development of, and interest in, analytical capacities at the organizational level is seen in the spread by governments of mandated management tools, performance indicators, and reporting mechanisms (Ontario, Saskatchewan, Quebec). The federal focus on wait times after the National Forum on Health, and targeted funding (i.e., Western Canadian Wait List Project) encourages these efforts. The focus of measurement and management also shifts to recognize changing population needs, which in turn emphasizes the need for patient input at federal and provincial levels. Patient and family advisory councils (BC, AB, SK) and community health boards (NS) contribute to informing health planning and evaluation at the organization and system levels. As is seen at the system level, organizational policy capacity often draws on experience in other jurisdictions to implement reforms: Ontario’s Cardiac Care Network, initiated in the early 1990s, provides a roadmap for multiple subsequent efforts to establish priorities and track improvements (i.e., Interview P3003).

Individual-level policy capacity develops and circulates in various ways in health reforms. Policy and clinical leaders are often mobilized. Dr Cy Frank, for example, developed an optimal care continuum at the Alberta Bone and Joint Institute that would provide the model for the province’s strategic clinical networks. Leaders also move between provinces and between provincial and national levels and are sometimes imported from abroad. The government of Saskatchewan brought in Don Berwick, who had led the US IHI, as a special advisor for its new Health Quality Council. When Alberta consolidated health regions into Alberta Health Services (AHS), it hired health economist Stephen Duckett from Australia as its first head.

Overall, analytical capacities are mobilized in recent reforms through a much more confined policy process where accountability and assessment are the core focus of attention. Ideas circulate between provinces that watch each other attentively to see how reforms—notably in primary care and regional governance—unfold. For example, Alberta’s precocious move to roll its regional health authorities (RHAs) into a single health authority (2008) provided leaders in other provinces an opportunity to examine the risks and benefits involved and tailor their own reforms accordingly. In some provinces, physician groups are also allowed important roles in advising government reforms (BC, AB, Ontario, and Manitoba). In the past 30 years, we see a shift from focusing on capacity to generate a broad policy agenda to putting analytical capacity at the service of accountability, performance assessment, and patient experience. This shift has implications for the type of analytical capacities developed and deployed by governments at the organizational level and the individual level.

Political capacities

As mentioned above, commissions, by involving a variety of stakeholders in policy conversations, increase the legitimacy of innovative policy options. For example, in Nova Scotia: “The ministry did a tour around the province and spoke to various constituents, so staff, physicians, leadership and at that point it was less a consultation on: ‘Will we on will we not consolidate’, it was more about what are the things that matter for health care in the future” (Interview NS C0050000). In addition, governments often use formal agreements and negotiations to stabilize relationships with key stakeholders and increase the feasibility of reforms. For example, the signature of master agreements between medical associations and government can stabilize political conditions within the system and ultimately increase the ability to drive reforms. In transitioning to a single health authority, the Saskatchewan Medical Association was asked to assign two physicians to the transition committee. Conversely, tensions between doctors and government can impede reforms. Breakdowns in relations between government and physician associations can “poison the well” for reforms (Interview P50004). In one case, “negotiations started within the first year of our operation. And that put us in a very difficult position in the sense of how we engaged physicians in planning for future services, how to get people at the table talk about change at the same time that they’re negotiating what their fee structure is going to be” (Interview C0030000).

Similar situations can be observed with negotiations between health unions and government. Improving working conditions in nursing has been key to acceptance of reforms in many provinces, and nursing opposition can play a powerful role in electoral politics. Political capacity at the system level is also generated by the negative experiences of patients or providers. In Ontario, the creation of Cancer Care Ontario (CCO) in 2001 was prompted by the major embarrassment caused by media reports of cancer patients being sent to the USA for radiotherapy.

The creation by governments of arm’s length agencies like quality councils can decrease political risk (as well as help to install operational capacity, see below) and serve as a more acceptable conduit for reform efforts. There is a balancing act between introducing agency roles and respecting the “turf” of existing organizations and associations and their ability to rally constituencies. Maintaining a plethora of agencies and organizations risks duplication of effort and complexifies policy change (Local Health Integration Networks [LHINs] in Ontario). Quebec, in 2015, drastically reduced the number of such bodies (Agences, Association québécoise d’établissements de santé et de services sociaux [AQESSS], and Commissaire à la santé et au bien-être [CSBE]) to create a direct route from Ministry decisions to organizations.

Citizen and community participation is also constitutive of political capacity at the system and organization levels. Centralizing reforms erode traditional forms of community representation in governance (on hospital and regional boards) across provinces, and new mechanisms for patient/citizen/community contribution to policy capacity emerge. The PFCC Guiding Coalition created in Saskatchewan after the 2011 Patients First Review and Alberta’s Patient and Family Advisory Group (PFAG) formed in 2010 are attempts to balance increased Ministry powers with citizen input. The volatility of citizen participation structures across reforms in many provinces suggests it is difficult to achieve the right balance. In Quebec, reforms enacted in 2015 concentrated political capacity in government and countervailing powers (i.e., hospital associations and elected citizen boards) were abolished.

From an individual standpoint, long-tenured provincial Premiers offer a certain stability to plan and negotiate support for reforms, and most provinces experience three-term tenures of a given party between 1990 and 2018. The profile of Health Ministers plays a role in shaping reform content and approaches to policy-making. Ministers of Health with academic or leadership experience in health policy organizations tend to adopt a broader view of reforms incorporating social dimensions of health. Ministers of Health whose experience is in politics, medical politics, or management tend to focus on the optimization of healthcare delivery with less attention to a broader health policy agenda. Ministers may also recruit Deputy Ministers or advisors with expertise (often gained through commissions) or experience (at operational level) in particular areas to be pursued in reforms. For example, in Saskatchewan, Dan Florizone, who had initiated a major Lean effort as CEO of a health region, became the driving force in developing province-wide Lean capacities (Interviews P3003, P3001) “Our deputy minister had experience with Lean and success with it in his region… and it appeared a good tool to use across the system” (Interview P3002). There is significant sharing and transfer of expertise that sees individuals advising or recruited to initiate or run programs in other provinces. National agencies provide a meeting ground for provincial experts, enabling an up-across-down movement of policy ideas.

Overall, political capacity within governments aims to secure sufficient coalitional or formal support for health policy options and assure the institutional capacity to balance the interests and values of State and non-State actors in policy-making. Endless debate and negotiation around expanding the scope of practice of different health professionals or adjusting the mode of remuneration of medical doctors are symptomatic of limited political capacity within government to introduce desirable but contested policy options. The power stance of citizens within this mix is less evident. At the organization level, as discussed below, input increasingly focuses on governments promoting quality improvement (QI) programs at a large scale rather than governance, and quality agencies play a role in channeling the participation of a variety of stakeholders that feel less threatened by QI initiatives than by broad structural reforms. In all provinces, political capacity is observable at various levels of analysis and exerts a powerful impact on the trajectory of reforms. Political capacity is associated with a dose of realism, where desirable reforms may be put aside for reasons of political feasibility and risk, and, implicitly, due to a lack of political capacity to ride the highly contested terrain of reforms.

Operational capacities

The emphasis on performance in recent years (see subsection, Analytical capacities within health reforms, above) has led to a growing concern with operational capacity as a fundamental ingredient of capacities to implement and monitor health reforms within governments. We focus here on the development of agencies for quality and improvement, on funding and resourcing policy changes to transform delivery dynamics, and on system strategies to value the participation of medical doctors in large-scale improvement initiatives at the point of care. New agencies designed to drive evidence-informed practice and quality, and to support delivery organizations in improvement, are found across provinces (HQO, quality councils in BC and SK, INESSS-QC) and at the federal level (CADTH, CFHI, CIHI, and Canadian Patient Safety Institute [CPSI]). Their work is conditioned by the expectations of central governments and varies from generating standards, monitoring performance, disseminating best practices, and offering direct support to delivery organizations in the form of large-scale improvement partnerships, coaching, and training. Some provinces legislate basic requirements (i.e., Ontario’s Excellent Care for All Act requiring quality improvement plans [QIPs]) that encourage provider acceptance of agency supports and interventions.

Providers can be more open to support and direction from arm’s length agencies than from the government. In Saskatchewan, good relations between the Quality Council and the Saskatchewan Medical Association prompted 20% of all physicians to undertake (around 2005) practice redesign efforts (i.e., Advanced Access). In Alberta, PRIMARY CARE NETWORKS (PCNs) perceive the Quality Council “quite favorably”, seeing it as a “neutral party” (Interview P21000). Sectoral initiatives to increase operational capacity can also generate acceptance and serve as models for broader change. In Ontario, policies to improve cancer care were incarnated in a new agency, CCO, that served as a testing ground and incubator for models to organize, monitor, and assure quality that were later transferred to the broader health system. Nova Scotia experimented a model for heart health before expanding it into a provincial strategy for chronic disease prevention and management.

Use of private contracted consultants to operationalize reforms is not common but was tried in Saskatchewan and Quebec around Lean. In retrospect, system leaders point to detrimental effects from the rigidity of the Lean model implemented by the external consultant (Interview P3006). However, the breadth and consistency of implementation efforts produced lasting results in terms of organizational and individual operational capacity within the health system to undertake improvement.

In contrast to the enabling type of agency approach, restructuring in Quebec (2015) created a much closer direct relationship between government and the operational level, where the minister could gather establishment Directors General (DG)s around a same table, communicate a same set of priorities, and look at the same data to inform operational actions. “The ability to bring these 34 leaders around a table “helped overcome the barrier we often refer to as paralysis in health care” (Interview P8003). The centralizing tendency in many provinces appears as a desire for government to get a better handle on the operational end of the system. Ontario Health, created through the Connecting Care Act of 2019, is an implementing body for Ministry strategies, with a board and CEO appointed by and accountable to the Ministry. While organizational autonomy may increase adaptation and enthusiasm for improvement, centralized governance may assure some degree of uptake across the board.

Operational capacity also relates to funding and resourcing. Demanding improvement programs (i.e., Lean, wait times targets) increase resource demands. Many provinces authorize contracting out to private providers in the hope that it will ease pressure on the system (certain surgeries in QC, AB, BC, SK, or home care in ON). Legislation in several provinces also gives organizational leaders greater flexibility in managing human resources (QC Bill 30, 2004; BC Bill 29, 2002).

Given the medical profession’s technical autonomy, operational capacity has been developed by promoting structures that increase connection points with the publicly managed system. Emphasis on primary care, supported by targeted funding from the federal government, energized primary care reforms. Ontario promoted a Family Health Team model, Alberta PCNs, BC Family Practice Groups. Government in QC provided incentives and, later, threats of penalties, to spread a new model of primary care, the Family Medicine Group (as proposed by the Clair Commission). Similarly, specialist care networks in Alberta “have allowed us to work provincially and let providers meaningfully contribute to developing change” (Interview P21802).

Individual-level operational capacity relates to initiatives promoted by governments to enhance skills and leadership at scale to improve delivery. The operational capacities described above have implications for the development of a variety of incentives like policies around performance targets and monitoring and coaching for improvement (Studer Model in Ontario, CFHI programs, quality council coaches, etc.).

Among patients and service users, individual capacity rests on policies for developing capacities to find and use system resources and support for disease management and self-care. While many provinces have reduced the place of public health in their systems, in Nova Scotia, wellness and personal and community responsibility for health are recurrent themes in policy statements. Provinces have all created telephone (sometimes also Internet) nurse advice services to support self-care and appropriate recourse to services. BC’s government supports the most expansive such system.

Overall, we observe a shift from pursuing a broad reformative and often innovative agenda based on ambitious policy frames like population health, to an emphasis on making the system more manageable and accountable, with greater attention to operational capacity within health systems in recent reforms.

Conclusion on the manifestations of policy capacities

Governments mobilize a wide range of policy capacities in health reforms. Significant attention is paid to the generation of analytical capacities. The representation of analytical capacities is largely influenced by predominant political ideologies and the type of government in power. More conservative governments appear less inclined to promote an open-tent approach to health policy-making. They also tend to focus the reformative agenda on more operational issues across the system than innovative and bold policy ideas like the democratization of health systems and the importance of population health. In all provinces, pressure from the population and patients for a well-functioning publicly funded health system—a system that provides timely access to care—supports reforms aimed at developing operational capacities at scale to support health system improvement. Policy capacities are not only a resource to support the implementation of reforms. New policy capacities can be developed and deployed as a result of reforms, as illustrated (among others) by the creation of agencies to support large-scale system improvement.

Impact of policy capacity on HSS

As underlined in the “Methodology” section, we assess the impact of policy capacity on HSS across the three main types of policy capacity proposed by Wu and colleagues (Wu et al., 2015). As mentioned earlier, WHO model of HSS is structured around the following dimensions: service delivery, health workforce, information, medical products, vaccines and technologies, financing, leadership, and governance. We use the HSS framework as a proxy of the impact of policy capacities on the ability to achieve health reform’s objectives.

Policy capacities in early phase reforms (1990–2005)

Our empirical results suggest the importance of analytical capacity in the form of commissions, forums, advisory councils, panels, or committees in early phases of reforms and its positive impact on information as one dimension of HSS. These consultative bodies offer the opportunity to develop a more sophisticated approach to policy formulation and design by integrating a greater variety of perspectives and sources of evidence and testing the acceptability of innovative policy options. Analytical capacity intersects here with political capacity by promoting a social exchange approach to policy-making and reinforcing the ability to anticipate the consequences of policy options for various stakeholders.

While concerns were raised about growing healthcare costs in this early period of reforms, there was relative consensus within commission reports and governments about the importance of maintaining publicly funded health systems. Mobilization of policy capacities did not impact on the level and provision of financial resources available within health systems. Policy attention focused on the misalignment between existing health system priorities and the emerging health needs of the population. As clearly shown in the Health Services Restructuring Commission report (Ontario) and the Rochon Commission report (Quebec), there was a growing imbalance between the focus on acute care and the need to invest in prevention and in care for long-term conditions, including mental health. Many reforms in Canadian provinces attempted to improve comprehensiveness and continuity of care for high-need segments of the population, with limited success (Nasmith et al., 2010). While analysis of these issues proliferated, the political capacity of governments, including their genuine commitment to such a policy shift, was in too short supply to achieve significant change, resulting in limited impact on HSS. Misalignment between service delivery and the health workforce, and the health needs of the population, persisted.

Moreover, the political hesitancy of provincial governments to increase investments to compensate the inadequate basket of services covered under the Canada Health Act (i.e., deficiencies in drug coverage, home care, mental health, and prevention), in a context of budgetary cutbacks at provincial and federal levels, also had a negative impact on the ability to achieve a better alignment of financing with health needs and emerging health priorities. In addition, pressure from the population and the media to focus on access to high-tech medicine instead of looking at health care more broadly played a role in putting the optimization of care delivery at the forefront of the policy agenda.

This early period also reveals nascent attention to the importance of operational capacity among policy-makers. An emerging consensus, informed by greater analytical capacity, that health systems produce illegitimate variations in quality and safety of care was behind this new policy focus. Provincial and federal agencies for QI were created to generate this new supply of operational capacity in the first decade of 2000 and strengthen service delivery. Greater attention to operational capacity did not, however, refrain provinces from making broad legal or structural changes in search of more effective governance arrangements that destabilized health systems. Quebec, Saskatchewan, Nova-Scotia, and Alberta all made major structural changes after 2000 that culminated in more centralized governance.

Policy capacities in later phase reforms (2005–2019)

After about 2005, a narrower approach to policy-making was adopted by governments with varying intensity across Canada. Optimizing health system efficiency and effectiveness, namely improving the relation between the resources allocated to the health system and access to safe high-quality care, took center stage in health policy debates. The idea that health systems should be managed and perform like other service businesses also gained prominence. There is persistent tension between two perspectives: on sees optimization as better response to patient needs and experience of care; the other views the narrowing of policy debates and delegation of part of the policy-making process to external consultants or advisors as a regression from a broad view of health to a more traditional hospital-centric focus. Strategic clinical networks in Alberta appear as a promising exception, providing a vehicle to reconcile the objective of optimization with a better response to population health needs by managing comprehensive patient trajectories and ultimately achieving a better ratio between resources and outcomes. Operational capacity is crucial but is not sufficient to bring about large-scale transformations for HSS in terms of maximizing outcomes from the pool of resources allocated to care (Best et al., 2012).

After about 2010, we see growing efforts to step up analytical capacity by investing in data analytics. The idea here, and this is visible in the work of agencies like ICES, INESSS, CADTH, and CIHI, is to generate fine-grained information to better manage patient trajectories and align resource allocation accordingly. Social care is increasingly considered in these refinements in the analytical capacity, but this remains at an early stage of development. All these efforts aim at strengthening the ability of health systems to respond to evolving needs while simultaneously optimizing the use of resources.

Greater supply and sophistication of analytical and operational capacity characterize the period of reforms between 2010 and 2020. It may have a significant impact on HSS mostly around delivery of care, information, and governance. However, it does not satisfactorily answer the question of sufficient political capacity and political imagination to address broad social issues such as equity in health status and equity-oriented health systems (Ford‐Gilboe et al., 2018). Real reforms also mean touching the way providers and organizations access resources. Developing political capacity for such changes will likely be at the forefront of future policy debates, but major changes were not implemented in this regard across Canadian health systems before 2020.

This brings us to the question of policy capacity at the individual level. Clearly, the knowledge and experience of political leaders, and more specifically Ministers of Health, have implications for the content of reforms. Some have a progressive view of health and an expansive vision of what health systems should focus on. Others may bring narrower policy experience and conservative views on health that focus on optimizing current arrangements instead of remodeling or reinventing the system. Finally, as described above, some policy leaders come from the delivery side of the system and bring operational know-how and perspectives to the system level that help to promote policies that impact the way care is delivered. They need to be able to find counterparts across government who are receptive to this know-how.

In most cases, policy capacity influences the governance and service delivery dimensions of the WHO-HSS model. Outside periods of budgetary cutbacks, no major policy shifts are observed in the way health providers and care are financed. The political feasibility of reforming the model of financing providers (organizations and professionals) remains a major issue (Evans, 1990; Lazar et al., 2013). Recent policy debates around vulnerabilities of Canadian health systems (Forest & Martin, 2018) forcefully point to the need for expanded policy capacity. In fact, while policy capacity seems to have an influence on reforms, that capacity has itself resulted from many health reforms in Canada, as exemplified by the creation of agencies for QI.

Discussion and conclusion

As underlined earlier, characteristics of political regimes (such as federalism), predominant political ideologies, and allegiances, and the relative openness of policy process impact on the development of policy capacities for health reforms.

Policy capacity is an evolving notion in policy analysis. Initially, the concept referred mostly to having the best brains within government policy shops (Painter & Pierre, 2005). Policy capacity was synonymous with analytical capacity in the hope that this would bring a dose of rationality into an arena where politics too often trump policies. We certainly observe, in Canadian health reforms, a significant dose of analytical capacity, but it appears intimately linked to political capacity. Political capacity is about the leadership, will, and ability to persist in promoting and legitimating policy ideas in a contested landscape. Political capacity also reveals how health reforms are shaped through complex networks of traditional and non-traditional policy actors. The experience, expertise, and political allegiance of policy-makers or reformers influence the design and focus of reforms and the strategies proposed to alleviate situations that are considered problematic (Bacchi, 2010, 2015, 2016). Earlier reforms were mostly driven by a political context marked by social-democratic ideologies. Emphasis was put on creating a new synthesis between advances in population health and the redistributive role of welfare states. Bold policy ideas, like democratization of health systems and equity in health status, were at the core of these reforms. It proved challenging, however, to maintain or implement this progressive policy agenda, and over time, reforms became more limited in scope, focusing on policies to improve the delivery of care and services.

Analytical capacities were developed and mobilized to inform the reformative agenda. We suggest that in most cases, and in the earlier phase of reforms, public commissions were used to put a broad set of traditional and non-traditional policy actors to work at designing innovative health policies in reforms. A mixture of political and analytical capacities developed and was mobilized to support ambitious reforms: the political machine of reforms opened up access to new analytical capacities (unions, advocacy groups, and external researchers). Analytical capacities revealed the importance of persistent inequities in health status even when a population has access to a publicly funded health system. The federal government and a majority of provincial governments in Canada adopted a very open approach to designing health reforms in the 1990s and early 2000s.

With time, health reforms came to be driven more by the immediate shortcomings of health systems, such as difficulties in providing timely access to care for all. Producing care and not producing health became the driver of reforms, fueled by a managerial turn often associated with center-right governments that conceive health reforms in terms of accountability and performance management. In this new political context, analytical capacities are increasingly mobilized to document very targeted problems like wait times. Such a narrowing of the policy agenda is coherent with a growing emphasis on operational capacities as a key resource to support health reforms, with less concern for generating broad consensus through political capacities around bold and innovative policy ideas. The different types of policy capacities mobilized in health reforms appear strongly interdependent in our study and are largely influenced by the broader political context.

While both analytical and political capacities are important, we find that they can either work in tandem or apart. Recognizing and sharing insights into health policy problems, such as the vulnerabilities of Canadian health systems, is not sufficient to trigger impactful reforms. Political leaders may not be able or willing to drive promising ideas through the whole policy cycle to attenuate these vulnerabilities. Boundaries between the political and the analytical are often fuzzy in reforms. In some situations, mobilizing analytical capacity gives form and legitimacy to new policy ideas. In others, analytical capacity is more at the service of political ideology, as seen when leaders commission supplementary analysis to support pre-determined options. Rationalization of all sorts is often the result of such political scheming. Rationality in health reforms is thus hybrid at best, where political criteria of feasibility and acceptability are part of any reasonable analysis. Therefore, analytical capacity increasingly incorporates the ability to find facts and arguments to understand and negotiate the political landscape of policy changes (Blanchet & Fox, 2013). These considerations may limit the determination of political leaders to engage in ambitious reforms.

Our analysis suggests that provincial and federal governments share responsibilities and an ad hoc division of labor in the sphere of policy capacity. Because provinces have the main responsibilities in health, policy capacity at the federal level tends to strive for broad and generic capacities that may help all provinces through expertise, standards, and opportunities to come together. The federal government can also use targeted funding to support specific policy options. Polycentrism is at play but with a division of labor that can be contested in times of crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic. The federal government currently promotes the application of national standards in long-term care to resolve quality issues in this sector that were revealed during the pandemic. Provinces have asked for more money from the federal to strengthen their health system, but are less inclined to accept the imposition of standards or conditions. Federal regimes, like the one in Canada, imply that provinces are responsible for creating a coherent approach to reforms and for orchestrating capacities deployed by the federal government and capacities developed at the provincial level to implement health reforms. The federal government, despite its ability to value and promote national standards and use its spending power to support policy changes, is not in a position to materialize reforms as a coherent set of policy changes in context that might improve the delivery of care or the health of the population in each province or territory. This does not mean the federal government has no important role to play, but the impact of policy capacities at the federal level is indirect and mediated by provincial context and responsibilities.

In the Canadian context, operational capacity in terms of improvement science and data analytics has been a fertile terrain for complicity between governments at each level. Here, policy capacity is more a result than a driver of reforms. The federal government has invested money and manpower to increase the supply of policy capacity with the creation of a national agency to supply data on the state and performance of health systems in Canada (CIHI) and another to support health system improvement (CFHI and CPSI recently merged to create HEC). Creating such enabling agencies is less contested than pushing for the adoption of policies that require the achievement of targets in exchange of additional resources from the federal governments. Again, the broader political context of the relations between the federal and provincial governments influences the approach taken for the development and mobilization of policy capacities within reforms. Most provinces appear reluctant to see the federal government dictating the orientations of health reforms.

Provinces have also increasingly acknowledged the crucial role of operational capacity in reforms. This ranges from increasing information supply for governance and accountability to capacity for QI within the delivery side of their health system. It is difficult to assess if a greater focus on operational capacity renders the system more impervious to political disruption. Our analysis reveals a constant tension between the political beliefs and policy frames within government (provincial) and the perceived needs of health organizations and frontline providers. The current COVID-19 crisis provides numerous examples of disconnection between those who govern and those who produce care and services (J. L. Denis et al., 2021). In addition, political cycles that bring in new governments, each with their own ideologies, beliefs, and frames, make perseverance in reforms difficult. This may limit the impact of reforms and policy capacity on HSS.

Another intriguing aspect is the attention paid to operational capacity and the promotion of bold and innovative policy ideas. Early reforms are characterized by an open-tent approach to policy design that seems to leave more space for independence and plurality in analytical work. More recent reforms initiated in a context of less political openness seem to leave more space for operational capacity but less energy for broad political and policy thinking. A view of policy capacity as a balancing act across the three core capacities (analytical, political, and operational) appears crucial to initiating and driving impactful reforms. It is still uncertain how the involvement of actors such as patients and citizens in various capacities in the policy process helps create this more balanced approach. It must be recognized that policy capacity takes shape within the broader political economy of health systems where stasis is somewhat of a norm (Edwards & Saltman, 2017). Stability helps create capacities but may also contribute to inertia, including in the type of capacities that are valued and mobilized. This brings us to the question of realistic expectations regarding the impact of policy capacity on HSS.

Policy capacity within health reforms in Canada seems to have a greater impact on targeted areas such as governance and service delivery. While changes in financing and incentives and a refocusing around emerging health priorities appear desirable, policy capacity does not seem sufficient to challenge predominant political forces and professional or organizational interests. Health system optimization takes precedence over producing health in society. Emphasis on patient experience may heighten this focus to the detriment of audacious policy options that go beyond improving the current situation.

Finally, work on policy capacity highlights the inadequacy of an overly rationalistic approach to policy-making. By bringing political capacity on board as a sign of realism, scholars have steered the notion of policy capacity toward the less tangible aspects of policy change. It brings to the forefront the importance of tacit knowledge and experience among politicians and governments. While growing attention to operational capacity is symptomatic of the insufficiency of such highly political considerations, operational capacity will never, by itself, create the avant-garde of health policies. The embeddedness of operational capacity within a broader policy frame is important. As Bacchi (2010, 2015, 2016) reminds us, the way policy-makers problematize health policy issues strongly determines policy content and consequences. Our analysis suggests that the way problematization occurs within the policy process will also influence representations of capacities needed to support reforms. We have more operational capacity today to think about and implement reforms but still see enduring system vulnerabilities and deficiencies. The current pandemic may act as a wake-up call to the importance of thinking about capacities within broader policy frames that focus on health equity.

In the Canadian experience, and probably elsewhere, capacity to maintain a high degree of political imagination, critical thinking, and openness in the policy process and to muster the analytical and operational capacity to push ahead with contested but progressive reforms, is part of the ideal toolkit for policy-makers.

Supplementary Material

Appendix A: Model developed by Wu and colleagues (Wu et al., 2015)

Policy capacity: A conceptual framework for understanding policy competences and capabilities

X. Wu, M. Ramesh & M. Howlett: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2015.09.001

Extract from: Wu, X., Ramesh, M., & Howlett, M. (Wu et al., 2015). Policy capacity: A conceptual framework for understanding policy competences and capabilities. Policy and Society, 34(3–4), 165–171.

Appendix B: Methodology of the narrative development for each province

1: Construct literature-based narratives identifying reform objectives and strategies in each province, establish a timeline of reforms and identify key actors and intermediate outcomes

2. Validation of extended case narratives by key informants with policy experience in each province

3. Collection of interview data

4. Extension and adjustment of case narratives integrating interview data

The case narratives become the database for analysis

Note: The methodology described here has been presented in a previous publication: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/health-economics-policy-and-law/article/abs/learning-from-health-system-reform-trajectories-in-seven-canadian-provinces/3279D11424D90E3996457EC9340D2374#supplementary-materials

Appendix C.

Table C1. Empirical results—quotations illustrative of markers of the policy capacities in Wu et al.’s typology.

| Political | Analytical | Operational | |

|---|---|---|---|