Abstract

Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) is a major contributor to neonatal mortality worldwide. However, little information is available regarding rates of RDS-specific mortality in low-income countries, and technologies for RDS treatment are used inconsistently in different health care settings. Our objective was to better understand the interventions that have decreased the rates of RDS-specific mortality in high-income countries over the past 60 years. We then estimated the effects on RDS-specific mortality in low-resource settings. Of the sequential introduction of technologies and therapies for RDS, widespread use of oxygen and continuous positive airway pressure were associated with the time periods that demonstrated the greatest decline in RDS-specific mortality. We argue that these 2 interventions applied widely in low-resource settings, with appropriate supportive infrastructure and general newborn care, will have the greatest impact on decreasing neonatal mortality. This historical perspective can inform policy-makers for the prioritization of scarce resources to improve survival rates for newborns worldwide.

Keywords: prematurity, neonatal mortality, technology, global health

The neonatal mortality rate (NMR) in the United States has decreased markedly over the past 60 years. In 1935, before the field of neonatology existed, the NMR was 35 per 1000 live births. 1 Since the 1950s, medical advances have decreased the NMR in a linear fashion to its current rate of ∼4 per 1000 live births. 2,3 However, despite these striking improvements in neonatal care in high-income settings, neonatal mortality contributes ∼40% to the mortality rate for children younger than 5 years around the world. 4

Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) was the neonatal condition that was most targeted for the development of treatments and technology for neonatal intensive care. From the current perspective, RDS is the most common respiratory disorder of premature newborns, and its incidence is directly proportional to the degree of prematurity. In the 1990s, RDS was diagnosed in ∼70% of very low birth weight infants (501–1500 g) in the United States. 5 RDS severity ranges widely from the need for low supplemental oxygen only to severe lethal respiratory failure, even with surfactant therapy and mechanical ventilation. 6 The pathophysiology of the disease is explained by a surfactant-deficient lung that is prone to collapse, which results in ventilation-perfusion mismatch, severe hypoxemia, and lung injury with spontaneous or mechanical ventilation. 6 Because there is no laboratory test to diagnose RDS, the diagnosis today is based on initial clinical symptoms, a chest radiograph consistent with RDS, the clinical course, and response to surfactant treatment.

Of the ∼40 000 infants in the United States with RDS each year, 7 the use of antenatal corticosteroids, surfactant treatment, and sophisticated modalities of ventilation have resulted in minimal mortality from RDS for infants born at >1500 g. Of the ∼15% of very low birth weight infants who die in high-resource countries, causes other than RDS (eg, pulmonary hypoplasia, severe intraventricular hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis, chronic lung disease) predominate. 5,8

In contrast, low-resource countries have high rates of neonatal mortality from RDS even in larger, less premature infants. 9 For example, in India, RDS occurs in much greater numbers: ∼200 000 infants per year according to 1 conservative estimate. 7 The overall mortality rate in larger infants from RDS alone remains high at ∼40% to 60%, 10,11 which is equivalent to the RDS mortality rate in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s, when oxygen was the only therapy. 12,13 Apart from what is cited here, few current data exist in low-resource settings regarding RDS-specific mortality rates. Therefore, we conducted a historical review to better understand the interventions that have decreased the rates of RDS-specific mortality in high-income countries over the past 60 years. We then estimated the effects on mortality in low-resource settings with the sequential introduction of technologies and therapies for RDS. Our hope is that understanding the effect of the introduction of treatment strategies over time on RDS mortality in the United States will inform policy-makers about the prioritization of scarce resources and result in improved survival rates for larger infants with RDS.

METHODS

We reviewed the English-language literature on neonatal mortality, RDS-specific mortality, and RDS treatments. We focused primarily on historical studies in high-income countries and more recent studies from low-resource settings for estimates of RDS-specific mortality rates. To identify the impact of interventions on survival after RDS, we grouped the RDS mortality data by 4 historic eras bookended by major interventions for the treatment of RDS, which include oxygen, mechanical ventilation, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), antenatal corticosteroids, and surfactant, to compare improvements in RDS mortality rates to the introduction of major advances in RDS treatment. Table 1 lists the 4 time periods and the various interventions introduced for treatment of RDS.

TABLE 1.

Time Periods With RDS Treatments

| Period | Years | RDS-Specific Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Before 1950 | No widely used treatment |

| 2 | 1950–1969 | Oxygen |

| 3 | 1970–1989 | CPAP |

| Mechanical ventilation | ||

| 4 | After 1990 | Antenatal corticosteroids |

| Surfactant | ||

| Advanced care technologies | ||

| High-frequency oscillation | ||

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

RESULTS

Period 1: Before 1950

RDS was first described by Hochheim 14 in 1903, who noted unusual membranes in the lungs of 2 infants who died shortly after birth. 12,15 This initial description was followed by ∼60 years of confusion regarding the pathogenesis, etiology, and nomenclature for the disease. On the basis of autopsies of 8 newborn infants, Johnson and Meyer 16 first described the histologic findings of a “hyaline membrane” that was thought to impair gas exchange. 15,17 Because of disagreements regarding the standard definition and pathology, various incidences and mortality from RDS were reported. At one point, 9 different names were used to describe the same pathologic findings. 18 In 1959, a group of pediatricians and pathologists met to discuss the diagnostic criteria for the condition and agreed on the name “idiopathic respiratory distress of the newborn.” 15 Because no effective therapy existed, virtually all infants with this diagnosis died shortly after birth.

Period 2: 1950–1969

This time period included a remarkable number of developments for neonatal care. Newborn infants were viewed as patients in their own right, and pediatricians began to direct efforts toward improving neonatal survival rates. 3 The first NICUs were developed. 3 Controlled thermal environments, fluid and electrolyte management, and parenteral nutrition improved the general care for premature infants. 3,19 The death of then-President Kennedy's son Patrick in 1963 as a result of RDS focused attention on diseases of the newborn and resulted in increased funding for neonatal research by the National Institutes of Health. 3

RDS supplanted hyaline membrane disease (an autopsy diagnosis) as the common term to describe the condition seen in 20% to 40% of newborns who died in the first few days of life. 12 Research using RDS-like disease in animal models advanced the understanding of the pathophysiology of the disease. 20 A surface-active material, subsequently called surfactant, was recognized to line the airways and decrease surface tension. 12,21,22 In 1959, Avery and Mead 23 reported that the amount of surfactant was related to birth weight and maturity, and surfactant was low in the lungs of infants who died of RDS. 12,24

Oxygen was the only available treatment for the hypoxemia of RDS. 24 In the late 1940s, with increased recognition of oxygen toxicity, including retrolental fibroplasia (now called retinopathy of prematurity) and damage to alveoli, 25 clinicians were hesitant to administer oxygen concentrations above 40% to preterm infants. Avery and Oppenheimer 26 described 2 time periods of practice at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. From 1944 to 1948, oxygen was used freely without measurement, and rates of retrolental fibroplasia were at their highest. However, from 1954 to 1958, oxygen concentrations were restricted to below 40%, and hyaline membranes noted on the autopsies of premature infants increased, suggesting that some infants were not receiving enough oxygen to survive the disease. 26 Much debate ensued about the oxygen concentrations that were safe and beneficial for the treatment of RDS.

Artificial ventilation for newborns was introduced in 1959; however, its application was controversial for RDS. The ventilators were not designed specifically for newborns, particularly preterm newborns. 19 Although investigators observed decreased rates of mortality with assisted ventilation in larger infants who died of inadequate respiratory effort, premature infants still died of severe progressive lung disease and associated conditions. 27 Therefore, the only widely used effective therapy for RDS during this time period was supplemental oxygen delivered into the incubator or by hood.

Period 3: 1970–1989

By the late 1960s in the United States, neonatologists were increasingly skilled at using mechanical ventilation to improve survival rates for infants born at low birth weight. However, lung injury from mechanical ventilation and oxygen were identified as complications of RDS treatments. 19,28 In 1971, Gregory et al 29 published a sentinel article on the use of CPAP for 20 infants with RDS. Sixteen patients survived, including 7 of 10 patients who weighed <1500 g at birth. 29 In describing 15 months of experience, Dunn 30 recounted that the introduction of CPAP reduced the RDS-specific mortality rate in his NICU from 33% to 14.9%.

The concept of CPAP to stabilize the surfactant-deficient lung was rapidly adapted as positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) for the first ventilators designed for infants. Several studies showed that PEEP in intubated patients reversed airway closure and collapse of terminal alveoli and resulted in increased oxygenation and ventilation 31,32 and improved the survival rates of ventilated infants with RDS from 23% to 70%. 33 However, the increased pressures used to ventilate infants caused the morbidities of pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, and pneumopericardium.

In 1972, Liggins and Howie 34 published results of a controlled trial of 282 pregnant women at risk of preterm delivery who were randomly assigned to a 2-dose antenatal corticosteroid treatment or placebo. Infants born between 26 and 32 weeks' gestation after maternal administration of corticosteroids had a lower incidence of RDS and a reduction in early neonatal deaths. 34 However, despite this and subsequent trials, antenatal corticosteroids were not widely used until after 1994, when a National Institutes of Health consensus statement recommended the practice. 35 A definitive systematic review in 1995 demonstrated a 50% reduction of RDS in the infants of mothers treated with antenatal corticosteroids, in addition to significant decreases in neonatal mortality and intraventricular hemorrhage. 36

During the 1970s, Enhörning and Robertson 37 demonstrated that preterm animals would respond to surfactant treatment. Infants with RDS were first treated with surfactant in 1980. 18,38,39 The development and extensive testing of surfactants for clinical use were completed by 1990. 39 Numerous clinical studies showed that several different surfactants decreased rates of pneumothorax and neonatal mortality. 40

Decreased RDS-specific mortality from 1970 to 1989 resulted primarily from increased expertise and more sophisticated technologies for newborn care, such as better ventilators, saturation monitors, and nutritional and fluid management. Regionalization of perinatal care provided better access for infants at risk for referral to centers that had the personnel, knowledge, and experience to provide advanced care to the sickest newborns. 41

Period 4: After 1990

Neonatologists, armed with surfactant and improved ventilators specifically designed for newborn infants, continued to improve the mortality rate for more extremely premature infants. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the use of antenatal corticosteroids increased markedly by the mid-1990s and also improved survival rates. 5,42 Improvements in mortality rates were seen in all birth-weight categories; however, infants born between 750 and 1500 g had mortality rates that were significantly lower than in preceding eras. 43

Few infants died primarily of RDS after 1990. However, as more infants born at 23 and 24 weeks' gestation survived, more chronic problems of prematurity were evident, including poor growth, bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), and poor neurodevelopment. 44 – 46 The common outcome of very low birth weight infants with RDS and immaturity was a different type of BPD than first described by Northway et al. 28,47 Although the BPD described by Northway et al was characterized by airway injury, parenchymal fibrosis, and emphysema in larger preterm infants managed with mechanical ventilation and oxygen, the new BPD was characterized by arrested lung development. 47

BPD became the primary adverse pulmonary outcome of prematurity and replaced RDS, which had become a treatable disease. When comparing rates of BPD among various institutions, it became evident that certain hospitals had much lower rates of BPD. In a search for explanations, the initial management of RDS has been questioned. Controversy has arisen regarding the need for immediate endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation after birth versus a noninvasive approach with CPAP with or without surfactant administration. 48 More patient-friendly systems for administering CPAP provide an alternative, noninvasive means of respiratory support for a premature newborn without mechanical ventilation. Indeed, multiple studies have demonstrated that surfactant therapy followed by extubation to nasal CPAP decreased the need for mechanical ventilation in infants with RDS born between 24 and 31 weeks' gestation. 49 – 51 Infants at risk of RDS could be supported initially with CPAP and then selectively treated with surfactant if their respiratory failure increased as indicated by increased oxygen needs, with no significant increase in major morbidities. 49 – 51

Changes in RDS-Specific Mortality Rates in the United States

The neonatal mortality rate has steadily declined in a linear fashion in the United States since the early 1900s to the mid-1980s. 3 Although the RDS-specific mortality rate has also decreased over the past 60 years in the United States, it is difficult to quantify the effect of specific therapies on the decreased mortality rate. The criteria for diagnosing RDS have changed over time as a greater understanding of the disease has been achieved. Studies from the 1940s and 1950s attributed deaths to RDS on the basis of autopsy evidence of hyaline membranes rather than on a clinical diagnosis of RDS. Also, the classification of RDS and hyaline membrane disease by the International Classification of Diseases system is problematic, because revisions in definitions make documenting trends for cause-specific mortality rates difficult as a result of possible misclassification bias. 52 Current national vital statistics data only report neonatal mortality caused by “respiratory distress of the newborn” without defining the more specific diagnosis of RDS. 53

Using death certificates, Malloy et al 52 noted the RDS-specific mortality rate to be ∼2.89 per 1000 live births between 1969 and 1973 with a 2% increase per year, which they attributed to changes in the coding of deaths (because a specific code was available for RDS/hyaline membrane disease in the eighth edition of the International Classification of Diseases). From 1974 to 1983, however, they observed a 9% per year decline in the RDS-specific mortality rate from 2.47 to 1.46 per 1000 live births, which was believed to result from the dissemination of neonatal intensive care and increased technology. 52 In a follow-up study from 1987 to 1995, Malloy and Freeman 54 estimated a decrease in the RDS-specific mortality rate by 56%, from 0.84 to 0.37 per 1000 live births; the largest decline was for larger infants born at 2000 to 2499 g and infants born at 33 to 36 weeks' gestation. The overall decline in RDS mortality accounted for 19% of the overall decline in infant mortality for the study period. 54 Malloy and Freeman felt that the decline in RDS-specific mortality was most pronounced after the introduction of surfactant in 1990. 54 Lee et al 55 also examined the trend in RDS-specific mortality from the years 1970 to 1995 by using linked birth and death certificates. They reported a decline in RDS-specific infant mortality from 2.6 per 1000 live births in 1970 to 0.4 per 1000 live births in 1995; more than three-quarters of this decrease occurred between 1970 and 1985, before the availability of surfactant or widespread use of antenatal corticosteroids. 55 The RDS-specific neonatal mortality rate decreased by 13% from 1985 to 1988 and by 28% between 1988 and 1991; these decreases were associated with surfactant. Lee et al 55 argued that although surfactant accelerated the decline in RDS-specific mortality, the greatest decline in RDS-specific mortality that occurred between 1970 and 1985 was likely a result of improved methods of mechanical ventilation, regionalized perinatal care, and continuous improvement in general neonatal care. As such, the RDS-specific mortality rate has decreased significantly for infants in all birth-weight categories. By the 1990s, mortality caused by RDS was minimal for infants born at >1500 g.

Management of RDS and Changes in RDS Mortality Rates in Low-Resource Settings

Although the documentation for decreased RDS-specific mortality is impressive in the United States, it is more challenging in low-resource settings, where death-certificate data are not available because of the lack of vital statistics registries. 56 Furthermore, a large proportion of infants who die of RDS may do so at home without treatment or documentation. Respiratory distress is the most common symptom in sick newborns, and verbal autopsy may not differentiate between the various causes of respiratory distress in term and preterm infants. 10 Even if the infant is evaluated, clinical skills and radiologic assessment may be inadequate to make the diagnosis of RDS. 56 Thus, reports of RDS incidence or RDS-specific mortality vary widely. For example, the Indian National Neonatal-Perinatal Database has revealed an incredulously low incidence of RDS of 1.2%, and an RDS-specific mortality rate of 13.5%, in a population in which 31.4% of infants are born at low birth weight and 14.5% are preterm. 57 The authors of a recently published multicenter South American study cited an RDS-specific mortality rate of 29.8%. 58 Nevertheless, RDS remains one of the most common causes of neonatal death in low-resource countries. 9 A case fatality rate of 100% in community-based settings has been reported, 59 and Indian neonatal units reported mortality rates of 57% to 89% in the 1990s. 11,60 Similarly, RDS survival rates ranged from 25% to 84% among centers in India. 7

The availability of interventions to treat RDS in low-resource countries is variable in the settings in which infants are born. In some rural locations, births may occur predominantly in the home, where all technologies such as oxygen, CPAP, or mechanical ventilation are absent, even with referral to nearby clinics. Although strong evidence supports the use of antenatal corticosteroids for women at risk of premature delivery to decrease the incidence of RDS and intraventricular hemorrhage, this treatment has not been tested in low-resource settings in which HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis may be comorbidities of pregnancy. In addition, the ability to identify women at risk of preterm delivery, a requirement for administration of antenatal corticosteroids, has not yet been evaluated. Such identification is not an easy task in settings in which mothers are malnourished and infants are often growth restricted. In addition, more than half of the infants born at home are delivered without a skilled attendant to identify prematurity and symptoms of RDS for referral to a higher level of care, if possible. 61

Regional clinics or hospitals that deliver infants also differ widely in the technologies and skills available to care for newborns. Regional clinics may be limited to oxygen use for care of a sick newborn with respiratory distress. Without referral, RDS-specific mortality rates should be similar to those in the United States in the 1950s. More basic hospitals may have only oxygen and perhaps CPAP and, therefore, have rates of RDS-specific mortality similar to those seen in the United States in the 1970s, whereas the most advanced centers have surfactant, sophisticated ventilators, and the infrastructure to care for infants with RDS and may have minimal rates of RDS-specific mortality (comparable to those in the United States today). Nevertheless, as technologies used for neonatal intensive care in high-resource countries become more available in low-resource settings, mortality rates for RDS have decreased (down to 14% in a 2004 Indian study 7 and 29.8% in a multicenter South American study 58 ).

Although mechanical ventilation for newborns was introduced in India in the late 1980s, few academic institutions ventilated newborns in the early 1990s, 7 ∼20 years after ventilators were in widespread use in the United States. In a survey from 1995, infants with RDS accounted for 36% of mechanical ventilation cases across neonatal units in India. 62 Another study revealed that 17.8% of newborns who required ventilator care could not be referred because of financial constraints. 63 Thus, the level of technology available to treat a newborn with respiratory distress varies significantly according to where the infant is born, the distance the sick infant has to travel to reach a health center with the appropriate level of care, and financial resources of the family. Despite the increased use of more sophisticated technology, morbidity and mortality rates related to RDS remain high. 10

In a study of risk factors for mortality in infants with RDS at Aga Khan University Hospital in Pakistan, Bhutta and Yusuf 10 noted that despite access to high technology, a “learning curve” existed for the medical staff to appropriately care for sick newborns. In addition, although the technology was available, problems with the equipment, limited numbers of ventilators, and the inability to quickly replace faulty machines were also frustrations. 10 One significant risk factor for mortality was pneumothorax, which decreased after the introduction of surfactant therapy, similar to the clinical experience in the United States. 10 In addition, as survival rates improve with better treatments for RDS, there will be an increased burden of chronic lung disease and other long-term morbidities associated with prematurity. 7

DISCUSSION

We have reviewed why neonatal mortality associated with RDS declined in the United States over time and why RDS-specific mortality rates remain high in low-resource settings. In the United States, a better understanding of the pathophysiology of RDS, and specific interventions directed toward its treatment, including oxygen, CPAP, antenatal corticosteroids, surfactant, and mechanical ventilation, have improved survival rates for infants in all birth-weight categories, especially for larger premature infants, who responded first with improved survival rates before their more premature counterparts. In attempts to improve survival rates in low-resource settings, technologies that enjoy success in high-resource settings are currently being transferred. However, little thought is given to the implications for low-resource settings, which are variably able to adopt the technology because of differences in skilled personnel and lack of supportive infrastructure or government commitment, among many other factors. The lack of regionalized perinatal centers with the experience and staff to care for sick preterm infants adds to the challenge. Often, the technologies are adopted without evaluations of their effective use in such settings. High-end equipment requires sophisticated training, support, and resources, which may divert valuable resources from simple devices that may be easier to implement. Thus, policy-makers need recommendations on where to focus their scarce resources.

Global disparities exist, and we recognize that the use of technology for more premature infants born at <1500 g is a costly venture no matter where in the world. In 1 study, the costs of hospitalization per uncomplicated surviving infant with RDS in the United States were approximately $2448 for those born at >1500 g and 5 times that for the infants with birth weights of >1000 to 1500 g. 64 Treatments for more premature infants may result in long-term survival, albeit with significant neurodevelopmental delays in an environment unable to support children with special needs.

As such, we sought to prioritize the implementation of technologies that would have the greatest impact for the infants with the chance for intact survival. We recognize that for technology to be used successfully, personnel must be trained to use and maintain the equipment, which lends support to our bias that simpler is better. Assuming that sufficient infrastructure, clinical skills, and access to neonatal care existed, we wanted to imagine how the current, highly successful technologies available for the treatment of RDS could be used most efficiently to save the most newborn lives in low-resource settings. This exercise may help policy-makers select therapies that will have the greatest impact at the lowest cost.

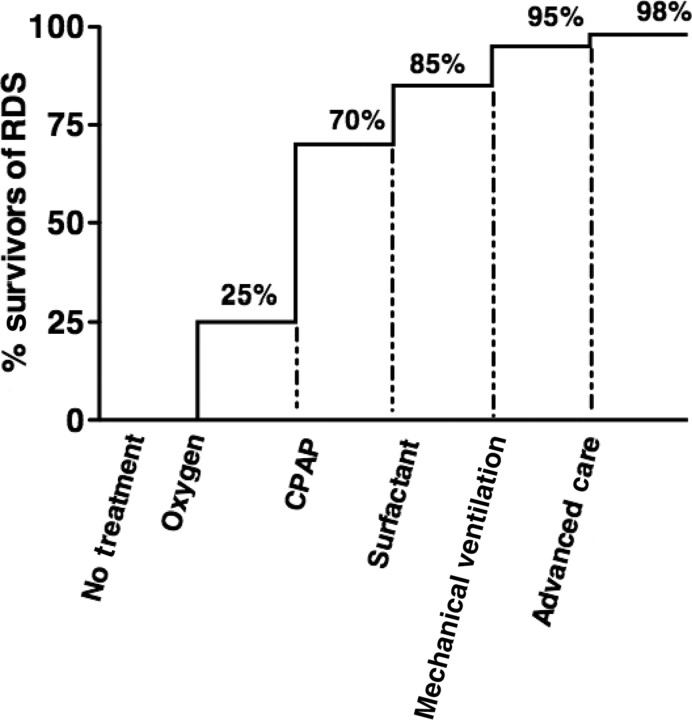

In particular, we focused on premature infants born at >1500 g as the those who are mature enough to need less specialized neonatal care (eg, blood transfusions, inotropic support, intravenous nutrition) and, importantly, to have intact survival. On the basis of our review of the current literature and our understanding of the decline of RDS-specific mortality in the United States, we speculate that for 100 premature infants born at >1500 g who have RDS, the mortality rate would be close to 100% without any intervention, similar to that for RDS survival before oxygen treatment and what is seen in community-based low-resource settings today (Fig 1). 59 As occurred for the treatment of RDS in the United States, 55 the greatest decline in the RDS-specific mortality rate will result from the availability and appropriate use of oxygen and then CPAP. With oxygen alone as a basic treatment for RDS, 25% (25) of the infants could perhaps be salvaged. Of the 75 remaining infants, CPAP plus oxygen would be sufficient to treat 45 of them. With the addition of surfactant, an additional 15 infants might be saved, and with prolonged mechanical ventilation, an additional 10 infants could be salvaged. With these therapies, if used correctly, we speculate that ∼95% of premature infants born at >1500 g with RDS could be saved. The addition of advanced neonatal care, including high-frequency oscillation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, only possible in a hospital setting with sufficient infrastructure and knowledgeable personnel, may only save an additional 3 infants.

FIGURE 1.

Speculated increased percentage in RDS survivors with introduction of specific treatments.

CONCLUSIONS

The more widespread availability of the basic interventions of oxygen and CPAP would have the greatest impact on decreasing RDS-specific mortality rates around the world. Much work is already being done to make these interventions more easily adaptable and economical in low-resource settings. 65 – 68 The introduction of these technologies to the settings close to where most infants are born, such as local clinics, would save the most newborn lives. However, CPAP would be problematic without trained personnel, a supporting infrastructure, and innovative designs for resource-poor settings. Still, advances in technology that most improved survival rates for infants with RDS would not have greatly affected neonatal mortality without overall improvements in general neonatal care, including better methods of thermoregulation, feeding practices, intravenous nutrition, and regionalized perinatal care. Priority should be placed on the recognition and transport of the high-risk pregnant woman to a center that can provide specialized care for both the mother and her infant. Without suitable infrastructure, personnel, and technology to take care of premature infants, the significant contribution of neonatal mortality to the overall mortality rate of childhood younger than 5 years will not decrease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded through a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to the Research Triangle Institute for Maternal and Neonatal Directed Assessment of Technology (MANDATE). The MANDATE team includes Dr Doris Rouse, Richard Satcher, Ms MacGuire, Ms McClure and Drs Goldenberg, Kamath, and Jobe.

All authors have made substantial intellectual contributions to this study and have approved the final version to be published.

- RDS

- respiratory distress syndrome

- CPAP

- continuous positive airway pressure

- BPD

- bronchopulmonary dysplasia

REFERENCES

- 1. Clifford S . The problem of prematurity: obstetric, pediatric, and socioeconomic factors. J Pediatr. 1955;47(1):13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mathews T , MacDorman M . Infant mortality statistics from the 2006 period linked birth/infant death data set. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010;58(17):1–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lussky R . A century of neonatal medicine. Minn Med. 1999;82(12):48–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lawn JE , Kerber K , Enweronu-Laryea C , Massee Bateman O . Newborn survival in low resource settings: are we delivering? BJOG. 2009;116(suppl 1):49–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Horbar JD , Badger GJ , Carpenter JH , et al. ; Members of the Vermont Oxford Network. Trends in mortality and morbidity for very low birth weight infants, 1991–1999. Pediatrics. 2002;110(1 pt 1):143–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rodriguez R . Management of respiratory distress syndrome: an update. Respir Care. 2003;48(3):279–286; discussion 286–287 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kumar P , Sandesh Kiran PS . Changing trends in the management of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS). Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71(1):49–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fanaroff AA , Stoll BJ , Wright LL , et al. ; NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Trends in neonatal morbidity and mortality for very low birthweight infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(2):147.e1–147.e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ravikumara M , Bhat BV . Early neonatal mortality in an intramural birth cohort at a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Pediatr. 1996;63(6):785–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bhutta Z , Yusuf K . Profile and outcome of the respiratory distress syndrome among newborns in Karachi: risk factors for mortality. J Trop Pediatr. 1997;43(3):143–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kumar A , Bhat BV . Epidemiology of respiratory distress of newborns. Indian J Pediatr. 1996;63(1):93–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gregg RH , Bernstein J . Pulmonary hyaline membranes and the respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Dis Child. 1961;102(6):871–890 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Strang L . Neonatal Respiration: Physiological and Clinical Studies. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hochheim K . Ueber einige befunde in den lungen von neugeborenen und die beziehung derselben zur aspiration von fruchtwasser. Zentralbl Pathol. 1903;14:537–538 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Avery M . Hyaline membrane disease. In: Schaeffer A ed. The Lung and Its Disorders in the Newborn Infant. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Johnson WC , Meyer JR . A study of pneumonia in the stillborn and newborn. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1925;151–167 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dick F , Pund ER . Asphyxia neonatorum and the vernix membrane. Arch Pathol (Chic). 1949;47(4):307–316 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Obladen M . History of surfactant up to 1980. Biol Neonate. 2005;87(4):308–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Philip A . Chronic lung disease of prematurity: a short history. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;14(6):333–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Van Leeuwen G . Recent developments in neonatology. Mo Med. 1966;63(2):122–126 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pattle R . Properties, function and origin of the alveolar lining layer. Nature. 1955;175(4469):1125–1126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Clements J . Surface tension of lung extracts. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1957;95(1):170–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Avery M , Mead J . Surface properties in relation to atelectasis and hyaline membrane disease. AMA J Dis Child. 1959;97(5 pt 1):517–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Scopes J . Respiratory distress syndrome. In: Gairdner D , Hull D eds. Recent Advances in Paediatrics. London, United Kingdom: J&A Churchill; 1971:89–118 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lanman JT , Guy LP , Dancis J . Retrolental fibroplasia and oxygen therapy. J Am Med Assoc. 1954;155(3):223–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Avery M , Oppenheimer EH . Recent increase in mortality from hyaline membrane disease. J Pediatr. 1960;57(4):553–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Swyer PR . An assessment of artificial respiration in the newborn. In: Problems of Neonatal Intensive Care Units: Report of the 59th Ross Conference on Pediatric Research. Columbus, OH: Ross Laboratories; 1969:25–35 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Northway WH Jr , Rosan RC , Porter DY . Pulmonary disease following respiratory therapy of hyaline-membrane disease: bronchopulmonary dysplasia. N Engl J Med. 1967;276(7):357–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gregory G , Kitterman JA , Phibbs RH , Tooley WH , Hamilton WK . Treatment of the idiopathic respiratory-distress syndrome with continuous positive airway pressure. N Engl J Med. 1971;284(24):1333–1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dunn PM . Respiratory distress syndrome: continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) using the Gregory box. Proc R Soc Med. 1974;67(4):245–247 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Llewellyn M , Swyer P . Positive expiratory pressure during mechanical ventilation in the newborn. In: American Pediatric Society Inc and the Society for Pediatric Research. Atlantic City, NJ; 1970:224 [Google Scholar]

- 32. DeLemos R , McLaughlin GW , Robison EJ , Schulz J , Kirby PR . Continuous positive airway pressure as an adjunct to mechanical ventilation in the newborn with respiratory distress syndrome. Anesth Analg. 1973;52(3):328–332 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cumarasamy N , Nussli R , Vischer D , Dangel PH , Duc GV . Artificial ventilation in hyaline membrane disease: the use of positive end-expiratory pressure and continuous positive airway pressure. Pediatrics. 1973;51(4):629–640 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liggins GC , Howie RN . A controlled trial of antepartum glucocorticoid treatment for prevention of the respiratory distress syndrome in premature infants. Pediatrics. 1972;50(4):515–525 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Effects of corticosteroids for fetal maturation on perinatal outcomes. NIH Consens Statement. 1994;12(2):1–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Crowley P . Antenatal corticosteroid therapy: a meta-analysis of the randomized trials, 1972 to 1994. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173(1):322–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Enhörning G , Robertson B . Lung expansion in the premature rabbit fetus after tracheal deposition of surfactant. Pediatrics. 1972;50(1):58–66 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fujiwara T , Adams FH . Surfactant for hyaline membrane disease. Pediatrics. 1980;66(5):795–798 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Halliday H . Surfactants: past, present and future. J Perinatol. 2008;28(suppl 1):S47–S56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Soll R , McQueen M . Respiratory distress syndrome. In: Sinclair J , Bracken M eds. Effective Care of the Newborn Infant. New York, NY: Oxford; 1992:324–358 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Committee on Perinatal Health. Towards Improving the Outcome of Pregnancy: Recommendations for the Regional Development of Maternal and Perinatal Health Services. White Plains, NY: National March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 42. St John E , Carlo W . Respiratory distress syndrome in VLBW infants: changes in management and outcomes observed by the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Semin Perinatol. 2003;27(4):288–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schoendorf K , Kiely J . Birth weight and age-specific analysis of the 1990 US infant mortality drop: was it surfactant? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151(2):129–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hack M , Fanaroff A . Outcomes of children of extremely low birthweight and gestational age in the 1990s. Semin Neonatol. 2000;5(2):89–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Costeloe K , Hennessy E , Gibson AT , Marlow N , Wilkinson AR . The EPICure study: outcomes to discharge from hospital for infants born at the threshold of viability. Pediatrics. 2000;106(4):659–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Johnson S , Hennessy E , Smith R , Trikic R , Wolke D , Marlow N . Academic attainment and special educational needs in extremely preterm children at 11 years of age: the EPICure study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2009;94(4):F283–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jobe A . The new BPD: an arrest of lung development. Pediatr Res. 1999;46(6):641–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sekar K , Corff K . To tube or not to tube babies with respiratory distress syndrome. J Perinatol. 2009;29(suppl 2):S68–S72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Morley CJ , Davis PG , Doyle LW , Brion LP , Hascoet JM , Carlin JB ; COIN Trial Investigators. Nasal CPAP or intubation at birth for very preterm infants [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1529]. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(7):700–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. SUPPORT Study Group of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Neonatal Research Network; Finer NN , Carlo WA , Walsh MC , et al. Early CPAP versus surfactant in extremely preterm infants [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2010;362(23):2235]. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(21):1970–1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rojas MA , Lozano JM , Rojas MX , et al. ; Colombian Neonatal Research Network. Very early surfactant without mandatory ventilation in premature infants treated with early continuous positive airway pressure: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):137–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Malloy MH , Hartford RB , Kleinman JC . Trends in mortality caused by respiratory distress syndrome in the United States, 1969–83. Am J Public Health. 1987;77(12):1511–1514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Xu J , Kochanek KD , Tejada-Vera B . Deaths: preliminary data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2009;58(1):1–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Malloy M , Freeman D . Respiratory distress syndrome mortality in the United States, 1987–1995. J Perinatol. 2000;20(7):414–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lee K , Khoshnood B , Wall SN , Chang Y , Hsieh HL , Singh JK . Trend in mortality from respiratory distress syndrome in the United States, 1970–1995. J Pediatr. 1999;134(4):434–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Coulter J . The incidence of respiratory distress syndrome: with particular reference to developing countries. Trop Geogr Med. 1980;32(4):277–285 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. NNPD Network. Neonatal Neonatal-Perinatal Database, Report 2002–2003. Deorari A ed. New Delhi: Indian Council of Medical Research; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fehlmann E , Tapia JL , Fernández R , et al. ; Grupo Colaborativo Neocosur. Impact of respiratory distress syndrome in very low birth weight infants: a multicenter South-American study [in Spanish]. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2010;108(5):393–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bang AT , Bang RA , Baitule S , Deshmukh M , Reddy MH . Burden of morbidities and the unmet need for health care in rural neonates: a prospective observational study in Gadchiroli, India. Indian Pediatr. 2001;38(9):952–965 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Malhotra AK , Nagpal R , Gupta RK , Chhajta DS , Arora RK . Respiratory distress in newborn: treated with ventilation in a level II nursery. Indian Pediatr. 1995;32(2):207–211 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Landers C . Maternal and newborn health: a global challenge. In: The State of the World's Children. New York, NY: United Nations Children's Fund; 2009:5 [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bhakoo O , Narang A , Ghosh K . Assisted ventilation in neonates: an experience with 120 cases. Presented at: IX Annual Convention of National Neonatology Forum; Manipal, India; February 17–20 [Google Scholar]

- 63. Garg P , Krishak R , Shukla D . NICU in a community level hospital. Indian J Pediatr. 2005;72(1):27–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Neil N , Sullivan SD , Lessler DS . The economics of treatment for infants with respiratory distress syndrome. Med Decis Making. 1998;18(1):44–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Diblasi RM , Zignego JC , Smith CV , Hansen TN , Richardson CP . Effective gas exchange in paralyzed juvenile rabbits using simple, inexpensive respiratory support devices. Pediatr Res. 2010; In press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Diblasi RM , Zignego JC , Tang DM , et al. Noninvasive respiratory support of juvenile rabbits by high-amplitude bubble continuous positive airway pressure. Pediatr Res. 2010;67(6):624–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Mokuolu OA , Ajayi OA . Use of an oxygen concentrator in a Nigerian neonatal unit: economic implications and reliability. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2002;22(3):209–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Koyamaibole L , Kado J , Qovu JD , Colquhoun S , Duke T . An evaluation of bubble-CPAP in a neonatal unit in a developing country: effective respiratory support that can be applied by nurses. J Trop Pediatr. 2006;52(4):249–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]