Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Our goal was to determine the prevalence of intestinal parasites in internationally adopted children, to examine factors associated with infection, and to determine if evaluating multiple stool specimens increases the yield of parasite identification.

METHODS:

We evaluated internationally adopted children with at least 1 stool specimen submitted for ova and parasite testing within 120 days after arrival to the United States. In children submitting 3 stool specimens, in which at least 1 specimen was positive for the pathogen studied, we examined whether multiple stool specimens increased the likelihood of pathogen identification.

RESULTS:

Of the 1042 children studied, 27% had at least 1 pathogen identified; with pathogen-specific prevalence of Giardia intestinalis (19%), Blastocystis hominis (10%), Dientamoeba fragilis (5%), Entamoeba histolytica (1%), Ascaris lumbricoides (1%), and Hymenolepsis species (1%). The lowest prevalence occurred in South Korean (0%), Guatemalan (9%), and Chinese (13%) children, and the highest prevalence occurred in Ethiopian (55%) and Ukrainian (74%) children. Increasing age was significantly associated with parasite identification, whereas malnutrition and gastrointestinal symptoms were not. Overall, the yield of 1 stool specimen was 79% with pathogen recovery significantly increasing for 2 (92%) and 3 (100%) specimens, respectively (P < .0001). Pathogen identification also significantly increased with evaluation of additional stool specimens for children with and without gastrointestinal symptoms.

CONCLUSIONS:

We provide data for evidence-based guidelines for intestinal parasite screening in internationally adopted children. Gastrointestinal symptoms were not predictive of pathogen recovery, and multiple stool specimens increased pathogen identification in this high-risk group of children.

Keywords: intestinal parasites, screening, international adoption, diarrhea

WHAT'S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT:

Intestinal parasite screening is recommended for internationally adopted children after arriving to the United States. Studies have found that the prevalence of parasites varies according to birth country and age.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS:

Intestinal parasites were found in 27% of internationally adopted children, and parasite recovery increased with the evaluation of additional stool specimens. Age was predictive of pathogen recovery, whereas malnutrition and gastrointestinal symptoms were not.

Over the past decade, nearly 200 000 children were internationally adopted in the United States. 1 The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that all internationally adopted children have a comprehensive evaluation shortly after arrival to the United States, including intestinal parasite screening. 2 Three stools are recommended for ova and parasite (O&P) testing and 1 stool for Giardia and Cryptosporidium direct fluorescent antibody (DFA). For asymptomatic children, it is suggested that 1 specimen may be sufficient. Several studies have described the prevalence of Giardia intestinalis in internationally adopted children with varying prevalences depending on the birth countries studied. 3 – 10 Other studies have investigated whether examining multiple stool specimens increases the likelihood of pathogen identification. 11 – 17 None of these studies have examined whether there is a benefit in testing additional specimens based on gastrointestinal symptoms. To our knowledge, these questions have not been answered in studies of internationally adopted children.

At the initial evaluation of internationally adopted children at our center, parents were asked to collect 3 stools 48 to 72 hours apart. This practice provided us with a unique opportunity to determine the prevalence of intestinal parasites in a large population of internationally adopted children, to examine factors associated with infection, and to determine if evaluating multiple stool specimens increases the yield of parasite identification.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

Children evaluated at the International Adoption Center at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center from November 1999 through June 2006 were eligible for the study if they submitted at least 1 stool sample for O&P examination within 120 days of arrival to the United States and the parents did not report treatment of parasites. The institutional review board of Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center approved the study.

Study Variables

Demographic information included the child's birth date, gender, birth country, and institutionalization history (>6 months was considered institutionalized). Clinical data included initial visit date, the child's weight, stool testing dates, and results. Each child's weight was converted to weight-for-age z scores by using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts. 18 A weight-for-age z score of ≥2 SDs below the mean was used as a surrogate for malnutrition. 19 Age was examined as a continuous and a group variable (<1 and ≥1 year). To maintain anonymity, birth countries with fewer than 10 children were combined under a regional designation. For children with an initial visit of January 1, 2004, and later, a gastrointestinal history was obtained. Parents were asked if their child had diarrhea and the child's number of stools a day (<3 vs ≥3).

Parasite Testing

Three stool specimens taken 48 to 72 hours apart were requested from each child. Specimens were preserved in 10% formalin and polyvinyl alcohol. Samples in formalin were concentrated by formalin-acetate sedimentation as recommended by the manufacturer of the ParaPak ULTRA Stool System (Meridian Bioscience, Inc, Cincinnati, OH) before microscopic examination. Samples in polyvinyl alcohol were treated with Wheatley's modified trichrome stain (Meridian Bioscience, Inc) to create permanently stained specimens. Identified parasites were classified as pathogens or nonpathogens. To detect G intestinalis and Cryptosporidium parvum, at least 1 specimen was submitted for testing with the Merifluor DFA (Meridian Bioscience, Inc), which identifies each pathogen by fluorescent antibody labeling.

Statistical Analysis

Frequency tables of demographic characteristics were generated for each birth country and summarized according to the 4 major regions. Regional demographic differences were examined using logistic regression for categorical variables and the Kruskal-Wallis test for non-Gaussian variables. The reference group for these analyses was Latin America.

Bivariate and multivariable analyses were performed to examine the prevalence of intestinal parasites and factors associated with infection. The prevalence was determined if a parasite was identified in ≥1 stool submitted by each child. Risk factors examined included gender, age, institutionalization history, and nutritional status.

Bivariate analyses were conducted for each country by using χ2 tests or Fisher's exact test. For the multivariable logistic regression analyses, data from all birth countries were combined because of sparse data. There was a significant interaction between gender and both age and institutionalization; therefore, analyses were performed for each gender separately. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated. Giardia O&P and DFA results were compared to calculate sensitivity and specificity. To determine if multiple stool specimens increased the likelihood of pathogen identification overall and for children with and without gastrointestinal symptoms, only children who had submitted 3 specimens were included. For pathogen-specific analyses, at least 1 of the specimens had to have a positive result for the specific pathogen examined. Because the order of collection could not be ensured, we estimated the probability of obtaining at least 1 positive result if 1, 2, or 3 specimens were examined as follows: 1 specimen examined = (n 3 + 2/3 × n 2 + 1/3 × n 1)/N; 2 specimens examined = (n 3 + n 2 + 2/3 × n 1)/N; or 3 specimens examined = (n 3 + n 2 + n 1)/N, where n i is the number of subjects with i positive specimens i = 1, 2, 3.

Nonnormally distributed variables were descriptively summarized as medians (ranges) and categorical variables as percentages. All tests were 2-sided and not adjusted for multiple testing. P values of ≤.05 or 95% CIs for ORs that did not include the value of 1 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

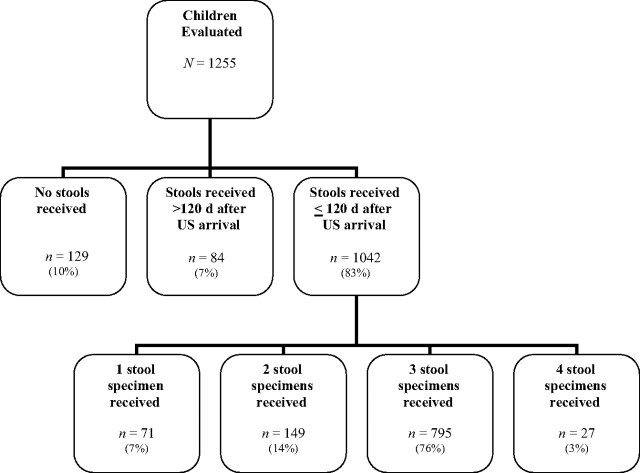

The International Adoption Center evaluated 1255 children from November 1999 through June 2006 (Appendix). Of these, 129 (10.3%) did not submit a stool specimen, 84 (6.7%) submitted stools >120 days after their US arrival, and 1042 (83.0%) submitted ≥1 stool specimen within 120 days of their US arrival and thus were included in the study. The distribution of time of specimen submission for these 1042 children was as follows: 55.9%, ≤2 weeks; 23.5%, within 2 to 4 weeks; and 20.6%, >4 weeks after arrival. Of the 1042 eligible children, 822 (78.9%) submitted ≥3 stool specimens, 149 (14.3%) submitted 2 specimens, and 71 (6.8%) submitted 1 specimen. Children included in the study were significantly younger (median age: 1.15 years) than those excluded because of the lack of stool submission (3.06 years) or stools collected >120 days after initial visit (3.05 years) (P < .0001).

Demographic Characteristics

The 1042 eligible children were adopted from 36 countries (Table 1). Eighty-four percent came from 5 countries: Russia (33%), China (22%), Guatemala (16%), South Korea (6%), and Kazakhstan (5%). Overall, 57% of children were female; 93% of Chinese children were female. The median adoption age was 14 months. Compared with other regions, Latin American children were more likely to be younger than 1 year, noninstitutionalized, and not malnourished.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Children According to Country/Region of Origin

| Country/Region | Total Children Studied |

Female Gender |

Age at Adoption, mo |

Aged Older Than 1 y |

Institutionalized |

Malnourished |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | Median | Range | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Europe | 431 | 41 | 189 | 44 | 20 a | 6–201 | 337 | 78 a | 420 | 97 a | 132 | 31 a |

| Russia | 346 | 33 | 156 | 45 | 17 | 6–201 | 256 | 74 | 339 | 98 | 108 | 31 |

| Ukraine | 31 | 3 | 9 | 29 | 37 | 15–172 | 31 | 100 | 31 | 100 | 14 | 45 |

| Bulgaria | 24 | 2 | 12 | 50 | 30 | 21–164 | 24 | 100 | 23 | 96 | 6 | 25 |

| Romania | 22 | 2 | 7 | 32 | 37 | 11–75 | 19 | 86 | 19 | 86 | 0 | 0 |

| Other Eastern European countries b | 8 | 1 | 5 | 63 | 19 | 9–40 | 7 | 88 | 8 | 100 | 4 | 50 |

| Asia | 410 | 39 | 304 | 74 a | 13 a | 3–173 | 229 | 56 a | 306 | 75 a | 88 | 21 c |

| China | 234 | 22 | 218 | 93 | 13 | 6–167 | 151 | 65 | 205 | 88 | 55 | 24 |

| South Korea | 60 | 6 | 22 | 37 | 8 | 4–28 | 14 | 23 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Kazakhstan | 57 | 5 | 28 | 49 | 12 | 7–173 | 29 | 51 | 55 | 96 | 11 | 19 |

| India | 21 | 2 | 14 | 67 | 16 | 5–89 | 14 | 67 | 19 | 90 | 13 | 62 |

| Vietnam | 21 | 2 | 14 | 67 | 13 | 3–83 | 12 | 57 | 15 | 71 | 2 | 10 |

| Other Asian and Pacific Rim countries d | 17 | 2 | 8 | 47 | 12 | 3–90 | 9 | 53 | 9 | 53 | 6 | 35 |

| Latin America e | 180 | 17 | 86 | 48 | 8 | 4–190 | 49 | 27 | 44 | 24 | 23 | 13 |

| Guatemala | 172 | 16 | 81 | 47 | 8 | 4–136 | 43 | 25 | 39 | 23 | 20 | 12 |

| Other Latin American and Caribbean countries f | 8 | 1 | 5 | 63 | 40 | 4–190 | 6 | 75 | 5 | 63 | 3 | 38 |

| Africa | 21 | 2 | 15 | 71 c | 61 a | 6–188 | 18 | 86 a | 18 | 86 a | 2 | 10 |

| Ethiopia | 11 | 1 | 8 | 73 | 58 | 9–180 | 10 | 91 | 11 | 100 | 2 | 18 |

| Other African countries g | 10 | 1 | 7 | 70 | 83 | 6–188 | 8 | 80 | 7 | 70 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 1042 | 100 | 594 | 57 | 14 | 3–201 | 633 | 61 | 788 | 76 | 245 | 24 |

Differences among regions, P < .0001.

Includes Albania, Belarus, Moldova, and Slovakia.

Differences among regions, c P < .05.

Includes Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Japan, Marshall Islands, Nepal, Philippines, Republic of Georgia, Taiwan, and Thailand.

Reference region.

Includes Bolivia, Colombia, Haiti, Jamaica, and Peru.

Includes Ghana, Liberia, Senegal, South Africa, and Zambia.

Prevalence of Intestinal Parasites

Overall, 27% of children had at least 1 pathogenic parasite identified (Table 2). G intestinalis was most prevalent, seen in 19% of children, followed by Blastocystis hominis (10%), Dientamoeba fragilis (5%), and Entamoeba histolytica (1%). Helminths were found in 2% of children, with Ascaris lumbricoides and Hymenolepsis species seen most frequently.

TABLE 2.

Proportion of Children With Any Parasite (N = 1042)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Pathogen | ||

| Protozoa | ||

| G intestinalis | 198 | 19 |

| B hominis | 100 | 10 |

| D fragilis | 50 | 5 |

| E histolytica | 11 | 1 |

| Helminths | ||

| A lumbricoides | 9 | 1 |

| Hymenolepsis species | 10 | 1 |

| S stercoralis | 3 | <1 |

| Trichuris trichuria | 4 | <1 |

| Hookworm | 1 | <1 |

| At least 1 pathogen | 279 | 27 |

| Nonpathogen | ||

| Protozoa | ||

| Entamoeba coli | 66 | 6 |

| Endolimax nana | 30 | 3 |

| Entamoeba hartmanii | 18 | 2 |

| Chilomastix mesnili | 10 | 1 |

| Iodamoeba butschlii | 9 | 1 |

Prevalence According to Birth Country/Region

There was a significant difference in pathogen prevalence among countries where Guatemala was the reference group (P < .0001) (Table 3). Low-prevalence countries were South Korea (0%), Guatemala (9%), China (13%), and Vietnam (19%) and high-prevalence countries were Romania (50%), Bulgaria (54%), Ethiopia (55%), and the Ukraine (74%).

TABLE 3.

Proportion of Children With Pathogenic Parasites According to Country/Region of Origin

| Country/Region | No. of Children (n = 1042), % | Any Pathogen a (n = 279), % | G intestinalis (n = 198), % | B hominis (n = 100), % | D fragilis b (n = 50), % | E histolytica (n = 11), % | Any Helminth (n = 21), % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | 431 | 44 c | 32 c | 17 d | 10 | 1 | 2 |

| Russia | 346 | 41 e | 30 | 16 | 9 | 1 | <1 |

| Ukraine | 31 | 74 e | 55 | 35 | 19 | 0 | 0 |

| Bulgaria | 24 | 54 e | 42 | 13 | 4 | 0 | 21 |

| Romania | 22 | 50 e | 27 | 14 | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Other Eastern European countries | 8 | 25 | 25 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asia | 410 | 14 | 10 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| China | 234 | 13 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| South Korea | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kazakhstan | 57 | 21 f | 11 | 12 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| India | 21 | 33 f | 29 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Vietnam | 21 | 19 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| Other Asian and Pacific Rim countries | 17 | 18 | 18 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Latin America | 180 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Guatemala | 172 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Other Latin American and Caribbean countries | 8 | 38 f | 25 | 38 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Africa | 21 | 62 c | 38 c | 19 g | 0 | 10 g | 29 c |

| Ethiopia | 11 | 55 e | 27 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 18 |

| Other African countries | 10 | 70 e | 50 | 30 | 0 | 20 | 40 |

| Total | 1042 | 27 | 19 | 10 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

Values shown are number of children or percentage.

Difference among countries was only obtained for any pathogen. The data were too sparse for analysis for remaining pathogens.

Data too sparse for analysis for regional comparisons.

Differences among regions with reference region of Latin America, P < .0001.

Differences among regions with reference region of Latin America, P < .001.

Differences among countries with reference country of Guatemala, P < .0001.

Differences among countries with reference country of Guatemala, P < .05.

Differences among regions with reference region = Latin America, P < .05.

Helminths were infrequently identified. Overall, 9 children had A lumbricoides identified, and these children were from China, Guatemala, Vietnam, and other African countries. Strongyloides stercoralis was found in 3 children. Of the 10 Hymenolepsis species identified in children from Bulgaria, Romania, Ethiopia, and Guatemala, 9 were Hymenolepsis nana and 1 was Hymenolepsis dimunata. Hookworm was identified in 1 Vietnamese child.

Prevalence According to Age, Institutionalization, and Nutritional Status

For the bivariate analyses, age was significantly associated with pathogenic identification overall and specifically for Russia, China, Kazakhstan, and India (Table 4). Of the 633 children 1 year of age or older, 40% had at least 1 pathogen versus 7% of those younger than 1 year (P < .0001). Institutionalized children were significantly more likely to have a pathogen compared with noninstitutionalized children (34% vs 4%; P < .0001). Overall, there were no differences in pathogenic identification in malnourished versus nonmalnourished children.

TABLE 4.

Proportion of Children According to Country/Region of Origin With Any Pathogenic Parasite and According to Gender, Age, Institutionalization, and Nutritional Status

| Country/Region | Total No. Studied | Gender, n (%) |

Age at Adoption, n (%) |

Institutionalized, n (%) |

Malnourished, n (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Younger Than 1 y | 1 y or Older | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||

| Russia | 346 | 190 (38) | 156 (44) | 90 (14) | 256 (50) a | 7 (14) | 339 (42) | 238 (44) | 108 (35) |

| Female | 156 | — | — | 37 (24) | 119 (50) b | 3 (33) | 153 (44) | 117 (43) | 39 (49) |

| Male | 190 | — | — | 53 (8) | 137 (50) a | 4 (0) | 186 (39) | 121 (45) | 69 (28) c |

| China | 234 | 16 (25) | 218 (12) | 83 (8) | 151 (16) | 29 (14) | 205 (13) | 179 (15) | 55 (9) |

| Guatemala | 172 | 91 (8) | 81 (10) | 129 (2) | 43 (28) a | 133 (2) | 39 (31) a | 152 (9) | 20 (5) |

| Females | 81 | — | — | 65 (3) | 16 (38) d | 62 (3) | 19 (32) b | 76 (11) | 5 (0) |

| Males | 91 | — | — | 64 (2) | 27 (22) b | 71 (1) | 20 (30) d | 76 (8) | 15 (7) |

| South Korea | 60 | 38 (0) | 22 (0) | 46 (0) | 14 (0) | 57 (0) | 3 (0) | 59 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Kazakhstan | 57 | 29 (21) | 28 (21) | 28 (7) | 29 (34) c | 2 (0) | 55 (22) | 46 (22) | 11 (18) |

| Females | 28 | — | — | 17 (12) | 11 (36) | 1 (0) | 27 (22) | 25 (24) | 3 (0) |

| Males | 29 | — | — | 11 (0) | 18 (33) | 1 (0) | 28 (21) | 21 (19) | 8 (25) |

| Ukraine | 31 | 22 (73) | 9 (78) | — | 31 (74) | — | 31 (74) | 17 (71) | 14 (79) |

| Bulgaria | 24 | 12 (67) | 12 (42) | — | 24 (54) | 1 (0) | 23 (57) | 18 (56) | 6 (50) |

| Romania | 22 | 15 (47) | 7 (57) | 3 (0) | 19 (58) | 3 (0) | 19 (58) | 22 (52) | — |

| India | 21 | 7 (29) | 14 (36) | 7 (0) | 14 (50) e | 2 (0) | 19 (37) | 8 (38) | 13 (31) |

| Females | 14 | — | — | 5 (0) | 9 (56) | 2 (0) | 12 (42) | 6 (33) | 8 (38) |

| Males | 7 | — | — | 2 (0) | 5 (40) | — | 7 (29) | 2 (50) | 5 (2) |

| Vietnam | 21 | 7 (14) | 14 (21) | 9 (11) | 12 (25) | 6 (17) | 15 (20) | 19 (16) | 2 (50) |

| Other Asia and Pacific Rim countries | 17 | 9 (22) | 8 (13) | 8 (0) | 9 (33) | 8 (0) | 9 (33) | 11 (18) | 6 (17) |

| Ethiopia | 11 | 3 (100) | 8 (38) | 1 (0) | 10 (60) | — | 11 (55) | 9 (67) | 2 (0) |

| Other Africa | 10 | 3 (67) | 7 (71) | 2 (50) | 8 (75) | 3 (33) | 7 (86) | 10 (70) | — |

| Other Eastern Europe countries | 8 | 3 (0) | 5 (40) | 1 (0) | 7 (29) | — | 8 (25) | 4 (25) | 4 (25) |

| Other Latin American and Caribbean countries | 8 | 3 (0) | 5 (60) | 2 (0) | 6 (50) | 3 (33) | 5 (40) | 5 (40) | 3 (33) |

| Total | 1042 | 448 (29) | 594 (25) | 409 (7) | 633 (40) a | 254 (4) | 788 (34) a | 797 (27) | 245 (28) |

P < .0001.

P < .01.

P = .02.

P < .001.

P < .05.

Multivariable analysis was performed separately for each gender. For female children, age and institutionalization were significantly associated with increased risk of infection. For each year of age, the adjusted odds of having any pathogen increased by a factor of 1.22 (95% CI: 1.13–1.31). The adjusted OR of having any pathogen was 5.10 (95% CI: 2.51–10.39) times higher for institutionalized children versus noninstitutionalized children. For male children, institutionalization data were too sparse for inclusion in the model. However, increasing age, overall and for the subgroup of institutionalized children, was significantly associated with pathogen identification (overall, OR: 1.78 [95% CI: 1.47–2.16]; institutionalized children, OR: 1.54 [95% CI: 1.31–1.82]). Malnutrition was not significant in either model.

Giardia intestinalis and Cryptosporidium parvum DFA Results

Overall, 979 children had DFA results for Giardia and Cryptosporidium, with 176 (18%) positive for Giardia and 19 (2%) positive for Cryptosporidium. The proportion positive for Giardia according to birth country did not vary when compared with Giardia O&P results (data not shown). The 19 children with Cryptosporidium were from Romania, the Ukraine, India, Russia, China, and Guatemala.

Comparison of Giardia DFA and O&P Testing

There were 730 paired O&P and Giardia DFA samples. O&P testing found 16% of children to have Giardia compared with 17% with DFA. In the 477 children in whom all 3 O&P samples were negative for Giardia, DFA identified 10 additional children with Giardia (2.1%). For the 104 children who had at least 1 of the 3 O&P samples positive for Giardia, DFA failed to identify 24 (23.0%) children with Giardia. Using the DFA as the gold standard, sensitivity and specificity for O&P testing was 83% and 99%, respectively. Using O&P as the gold standard, sensitivity and specificity for DFA was 93% and 96%, respectively.

Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Pathogenic Parasites

In a subset of 468 children, we questioned the children's parents about diarrhea history and the number of stools in a 24-hour period (stools per day). Data were missing for 13 children, leaving 455 for analyses. Diarrhea was reported in 82 (18%) children, and 373 (30%) reported their child had ≥3 stools per day. The proportion of children with any pathogen was not different between those with versus without diarrhea (20% vs 21%, respectively; P = .78). There were no significant differences in children with and without diarrhea for G intestinalis (13% vs 15%; P = .67); B hominis (7% vs 6%; P = .63), and D fragilis (4% vs 4%; P = .97). Also, the proportion of children with pathogens was the same in those with ≥3 vs <3 stools per day (20% vs 20%; P = .96).

Pathogen Yield With Examination of Multiple Stool Specimens

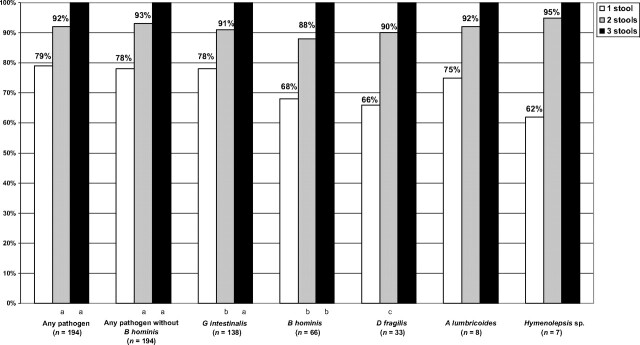

To determine if examining multiple stool specimens increased diagnostic yield, we used the subset of 795 children who had submitted 3 samples for evaluation (Fig 1). Analysis was limited to any pathogen, G intestinalis, B hominis, D fragilis, A lumbricoides, and H nana. Of the 194 children with any pathogen, if 1 specimen was tested, the probability of identifying any pathogen was 79%. For 2 specimens, the probability significantly increased to 92% (P < .0001), and for 3 specimens, it was 100% (P < .0001). Similar increases in yield were observed for G intestinalis, B hominis, D fragilis, A lumbricoides, and Hymenolepsis species.

FIGURE 1.

Increase in pathogen yield with increasing number of stools examined. a P < .0001; b P < .001; c P < .01.

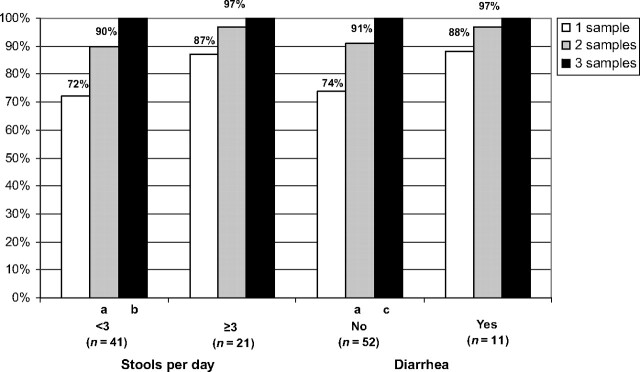

Pathogen Yield With Examination of Multiple Stool Specimens According to Symptom History

We assessed whether examining multiple stool specimens increased diagnostic yield for any pathogen in children with and without gastrointestinal symptoms (Fig 2). For children with <3 stools per day, yield significantly increased with 2 (P < .01) and 3 (P = .03) specimens. The increase with ≥3 stools per day was not significant. Similarly, in children without diarrhea, there was a significant increase in yield for any pathogen in children with 2 or 3 specimens (P < .01 and P = .01, respectively), whereas there was not a significant increase for children with diarrhea.

FIGURE 2.

Increase in yield of any pathogen with increased number of stools in children with and without gastrointestinal symptoms. a P < .01; b P < .03; c P < .01.

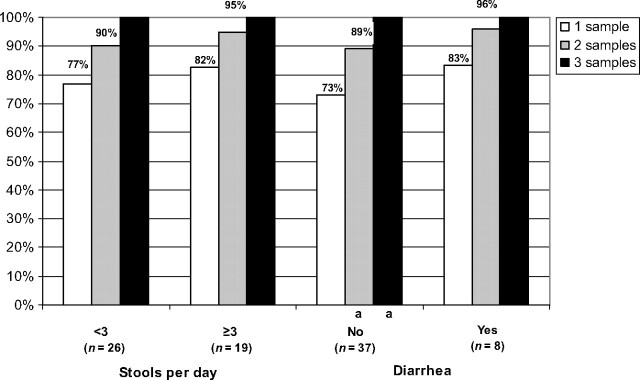

The analysis was repeated for G intestinalis (Fig 3). Although there was an increase in G intestinalis yield for children with <3 stools per day, for children with ≥3 stools per day and with and without diarrhea, the increase was only significant for children without diarrhea (P = .03).

FIGURE 3.

Increase in yield of G intestinalis according to increasing number of stools in children with and without gastrointestinal symptoms. a P < .03.

DISCUSSION

We found a high prevalence of intestinal parasites in our large cohort of internationally adopted children. Comparing our results with previously published studies is challenging given the distributional differences of age and birth country as well as a lack of detail regarding testing methods. Our overall prevalence of 27% was higher than the prevalence of 14% found in the only other study with a similar sample of internationally adopted children from an adoption clinic. 3 The difference seen could be because of differences in the distribution of age, birth countries (41% were Korean versus 6% in our study), and number of specimens tested. Compared with studies with country-specific estimates, our results were comparable in most cases. For Eastern Europe, our slightly lower prevalence of 44% compared with 51% determined in the study by Albers et al 5 is likely because of our lower median age (20 vs 26 months). Similarly, age differences may explain the differences between our prevalence of 50% compared with 33% found in a study of younger Romanian adoptees. 4 Our prevalence for Ethiopia (55%) was less than that (72%) determined by Miller et al, 10 and age did not seem to explain this difference because the mean age in our study was higher (65 months) than the mean age of 48 months reported in that study.

Several studies have reported G intestinalis prevalence in internationally adopted children. 3,4,6 – 9 Our overall and country-specific Giardia estimates varied according to birth country when compared with other published studies. The overall prevalence of 19% in the study by Saiman et al 7 was the same as ours. For Russia, our Giardia prevalence of 30% was similar to that of 2 other studies with prevalence findings of 25% 7 and 27%. 9 For China, the 10% prevalence we found for Giardia was the same as Miller and Hendrie 6 (10%) and similar to that of Saiman et al 7 (15%). Murray et al 9 reported a higher prevalence of Giardia in Ukrainian children (75%) than our estimate of 55%. Estimates for Guatemala ranged from 0% 7 to 8% 8 and were comparable to our finding of 6%.

We identified risk factors associated with pathogenic parasites in internationally adopted children. In the bivariate analyses, there were differences in the prevalence according to age, birth country, and institutional history. In the multivariable analyses, increasing age and institutionalization remained significantly associated with pathogen identification. Even limiting our analyses to the countries with the largest sample size, we were unable to demonstrate a difference in risk according to birth country. Our results are similar to other studies, with regard to finding a lower parasite prevalence among younger children compared with older children. 3,4,7 This finding is likely a result of younger children having less opportunity for exposure because of time, diet, and mobility. Our study supported the results of 2 other studies showing institutionalization as a risk factor for intestinal parasites. 3,8 We did not find an association between nutritional status and pathogen prevalence in either the bivariate or multivariable analysis. These results differ from the findings of Hostetter et al 3 who reported an association of malnutrition in an analysis using a similar definition for malnutrition. In a subanalysis, we examined pathogen prevalence in children with and without gastrointestinal symptoms. Similar to other studies, we did not find a difference in pathogen identification between children with and without diarrhea or with <3 and ≥3 stools per day. 20 – 26

We found that examination of multiple stool specimens increased the likelihood of pathogen identification. Several studies have examined this question in other populations, 11 – 17 and all but 1 12 found results similar to ours. Our probability of pathogen identification was 79% with 1 specimen and was similar to 3 other studies with estimates between 72% and 76%. 15 – 17 The increase in identification with 2 specimens ranged from 15% to 19% in these studies compared with our finding of 13%. An additional 8% of children were found to have a pathogen with a third specimen compared with 7% to 13% in the other studies. We also found an increase in pathogen-specific yield; however, these increases were only significant for the more prevalent parasites. In the only other study that examined their data according to parasite, Hiatt et al 14 found examining 3 stool specimens compared with 1 specimen increased the yield by 11%, 23%, and 31% for G intestinalis, Dientamoeba fragilis, and Entamoeba histolytica, respectively. These pathogen-specific results demonstrate the importance of examining multiple stool specimens. In addition, our analyses in children with and without gastrointestinal symptoms found a significant increase in the yield of pathogenic parasites in children without diarrhea and with <3 stools per day. These results suggest that regardless of gastrointestinal symptoms, all internationally adopted children should have ≥3 stools examined to identify intestinal parasites.

Although direct microscopic examination of specimens is reportedly less sensitive than DFA testing, 27,28 DFA did provide a modest increase in yield compared with O&P testing. This is consistent with previous work establishing the high sensitivity of the MERIFLUOR DFA test (Meridian Bioscience, Inc). 27,28 Our results support the use of DFA for screening this population for Giardia.

Although our study has several strengths, there were also limitations. Our study is the largest reported in internationally adopted children, but our sample size was still small for some countries, for subanalyses of less prevalent pathogens, and for the gastrointestinal symptom analyses and multivariable analyses. In addition, although we instructed parents on how to collect specimens, we cannot guarantee that the specimens were spaced or collected as instructed. Similar to other studies, the laboratory was not blinded to the routine O&P test results. Therefore, knowledge of results of previously examined specimens could bias identification of a specific parasite. A potential limitation is that there could be differences in our results by the timing of stool collection. To examine this concern, we did additional analyses according to the time of collection and we did not find any significant difference in pathogen identification by time of collection; 25.6% were positive with collection ≤2 weeks, 21.4% for collection 2 to 4 weeks, and 27.4% with collection >4 weeks from arrival to the United States. In addition, the results for the increase in pathogen yield with multiple specimens were similar for each of the time to collection strata. Another concern is the controversy over whether B hominis is a pathogen. 2,29,30 We repeated the analyses excluding B hominis as a pathogen, and the overall results and conclusions of our study did not change. In addition, we were unable to determine if the Giardia strains were virulent or resistant. We also did not systematically examine children after treatment to determine if the child's nutritional status and gastrointestinal symptoms improved or if other family members were infected. Finally, children could have received antiparasitic treatment before stool testing. Providing albendazole has been suggested as a cost-effective strategy for management of parasites in immigrants. 31,32 If treatment had been given to the children we evaluated, this therapy could have affected our results.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results provide data for the development of evidence-based guidelines for intestinal parasite screening in internationally adopted children. On the basis of our results, American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations should be revisited so that 3 stool specimens are submitted and evaluated for all internationally adopted children on arrival to the United States, regardless of gastrointestinal symptoms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dee Daniels, Linda Jamison, Rachel Akers, Jen Andriga, Marina Bischoff, Tyler Browning, Vanessa Florian, Kristen Frommier, Emilie Grube, Kasey Leach, Rotimi Okunade, and Elizabeth Roberts for their assistance with this study. We also thank all the wonderful children and their families who contributed to this study and whose participation will help improve the health of internationally adopted children in the future.

APPENDIX.

Evaluation of 1255 children from November 1999 through June 2006, at the International Adoption Center.

Portions of this work were presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies' annual meeting; May 2, 2010; Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

- OR

- odds ratio

- CI

- confidence interval

- O&P

- ova and parasite

- DFA

- direct fluorescent antibody

REFERENCES

- 1. US Department of State. Immigrant visas issued to orphans coming to US. Available at: http://adoption.state.gov/about_us/statistics.php . Accessed July 22, 2011

- 2. American Academy of Pediatrics. Medical evaluation of internationally adopted children for infectious diseases. In: Pickering LK , Baker CJ , Long SS , McMillan JA eds. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:177–184 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hostetter MK , Iverson S , Thomas W , McKenzie D , Dole K , Johnson DE . Medical evaluation of internationally adopted children. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(7):479–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Johnson DE , Miller LC , Iverson S , et al. The health of children adopted from Romania. JAMA. 1992;268(24):3446–3451 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Albers LH , Johnson DE , Hostetter MK , Iverson S , Miller LC . Health of children from the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. JAMA. 1997;278(11):922–924 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Miller LC , Hendrie NW . Health of children adopted from China. Pediatrics. 2000;105(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/105/6/e76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Saiman L , Aronson J , Zhou J , et al. Prevalence of infectious diseases among internationally adopted children. Pediatric. 2001;108(3):608–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miller L , Chan W , Comfort K , Tirella L . Health of children adopted from Guatemala: comparison of orphanage and foster care. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/115/6/e710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Murray TS , Groth ME , Weitzman C , Cappello M . Epidemiology and management of infectious diseases in international adoptees. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18(3):510–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Miller LC , Tseng B , Tirella LG , Chan W , Feig E . Health of children adopted from Ethiopia. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12(5):599–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thomson RB , Haas RA , Thompson JH . Intestinal parasites: the necessity of examining multiple stool specimens. Mayo Clin Proc. 1984;59(9):641–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gyorkos TW , MacLean JD , Law CG . Absence of significant differences in intestinal parasite prevalence estimates after examination of either one or two stool specimens. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;130(5):976–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nazer H , Greer W , Donnelly K , et al. The need for three stool specimens in routine laboratory examinations for intestinal parasites. Br J Clin Pract. 1993;47(2):76–78 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hiatt RA , Markell EK , Ng E . How many stool examinations are necessary to detect pathogenic intestinal protozoa? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;53(1):36–39 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cartwright CP . Utility of multiple-stool-specimen ova and parasite examinations in a high-prevalence setting. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37(8):2408–2411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Branda JA , Lin TY , Rosenberg ES , Halpern EF , Ferraro MJ . A rational approach to the stool ova and parasite examination. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(7):972–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Suputtamongkol Y , Waywa D , Assanasan S , Rongrungroeng Y , Bailey JW , Beeching NJ . The review of stool ova and parasite examination in the tropics. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(6):793–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES: CDC growth charts—United States. Available at: www.cdc.gov/growthcharts . Accessed September 24, 2010

- 19. Trehan I , Meinzan-Derr JK , Jamison L , Staat MA . Tuberculosis screening in internationally adopted children: the need for initial and repeat testing. Pediatrics. 2008;122;e7-e14. Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2007-1338 . Accessed September 24, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lerman D , Barrett-Connor E , Norcross W . Intestinal parasites in asymptomatic adult Southeast Asian immigrants. J Fam Pract. 1982;15(3):443–446 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Salas SD , Heifetz R , Barrett-Connor E . Intestinal parasites in Central American immigrants in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150(7):1514–1516 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Karrar ZA , Rahim FA . Prevalence and risk factors of parasitic infections among under-five Sudanese children: a community based study. East Afr Med J. 1995;72(2):103–109 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Buchwald D , Lam M , Hooton TM . Prevalence of intestinal parasites and association with symptoms in southeast Asian refugees. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1995;20(5):271–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Utzinger J , N′Goran EK , Marti HP , Tanner M , Lengeler C . Intestinal amoebiasis, giardiasis and geohelminthiases: their association with other intestinal parasites and reported intestinal symptoms. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93(2):137–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Benzeguir AK , Capraru T , Aust-Kettis A , Bjorkman A . High frequency of gastrointestinal parasites in refugees and asylum seekers upon arrival in Sweden. Scand J Infect Dis. 1999;31(1):79–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tinuade O , John O , Saheed O , Oyeku O , Fidelis N , Olabisi D . Parasitic etiology of childhood diarrhea. Indian J Pediatr. 2006;73(12):1081–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zimmerman SK , Needham CA . Comparison of conventional stool concentration and preserved-smear methods with merifluor Cryptosporidium/Giardia direct immunofluorescence assay and ProSpecT Giardia EZ microplate assay for detection of Giardia lamblia. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33(7):1942–1943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Garcia LS , Shum AC , Bruckner DA . Evaluation of a new monoclonal antibody combination reagent for direct fluorescence detection of Giardia cysts and Cryptosporidium oocysts in human fecal specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30(12):3255–3257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tan TC , Suresh KG . Predominance of amoeboid forms of Blastocystis hominis in isolates from symptomatic patients. Parasitol Res. 2006;98(3):189–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stenzel DJ , Boreham PF . Blastocystis hominis revisited. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9(4):563–584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Muennig P , Pallin D , Sell RL , Chan M . The cost effectiveness of strategies for the treatment of intestinal parasites in immigrants. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(10):773–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Muennig P , Pallin D , Challah C , Khan K . The cost-effectiveness of ivermectin vs. albendazole in the presumptive treatment of strongyloides in immigrants to the United States. Epidemiol Infect. 2004;132(6):1055–1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]