Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this study was to identify rates of switching to Medicare Advantage (MA) among fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) by race/ethnicity and whether these rates vary by sex and dual-eligibility status for Medicare and Medicaid.

Methods

Data came from the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File from 2017 to 2018. The outcome of interest for this study was switching from FFS to MA during any month in 2018. The primary independent variable was race/ethnicity including non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic African American, and Hispanic beneficiaries. Two interaction terms among race/ethnicity and dual eligibility, and race/ethnicity and sex were included. The model adjusted for age, year of ADRD diagnosis, the number of chronic/disabling conditions, total health care costs, and ZIP code fixed effects.

Results

The study included 2,284,175 FFS Medicare beneficiaries with an ADRD diagnosis in 2017. Among dual-eligible beneficiaries, adjusted rates of switching were higher among African American (1.91 percentage points [p.p.], 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.68–2.15) and Hispanic beneficiaries (1.36 p.p., 95% CI: 1.07–1.64) compared to non-Hispanic White beneficiaries. Among males, adjusted rates were higher among African American (3.28 p.p., 95% CI: 2.97–3.59) and Hispanic beneficiaries (2.14 p.p., 95% CI: 1.86–2.41) compared to non-Hispanic White beneficiaries.

Discussion

Among persons with ADRD, African American and Hispanic beneficiaries are more likely than White beneficiaries to switch from FFS to MA. This finding underscores the need to monitor the quality and equity of access and care for these populations.

Keywords: Dementia, Health care costs, Health insurance, Racial disparities

Beneficiaries who qualify for Medicare can “choose” whether to enroll in fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare or Medicare Advantage (MA). MA plans must cover all of the services that FFS Medicare covers except hospice care, but they place limits on out-of-pocket spending, have provider networks, and may require preauthorization for specific services (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2020c). MA has become a popular alternative among Medicare beneficiaries in recent years. Since the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, enrollment in MA increased by 21 percentage points (p.p.) among Medicare beneficiaries (from 25% in 2010 to 46% in 2021) and over 26 million beneficiaries were enrolled in MA plans in 2021 (Freed, Biniek, et al., 2022). In fact, prior research suggested that over 50% of new entrants to MA switched from FFS (G. A. Jacobson et al., 2015). Furthermore, individuals with dual eligibility to Medicare and Medicaid may be likely to switch between MA and FFS due to the ability to enroll in MA at any point during the year without penalty or restrictions (Meyers, Belanger, et al., 2019).

Unfortunately, there are wide disparities regarding socioeconomic status, health, cognitive impairment, and health coverage among Medicare beneficiaries that could constrain insurance choices among vulnerable groups (Ochieng, Cubanski, et al., 2021). MA plans are designed to have low monthly premiums, a limit on out-of-pocket costs, and additional benefits unavailable in FFS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2020b). These MA plan features and preexisting socioeconomic and systematic barriers may influence MA enrollment among racial and ethnic minority groups and beneficiaries with low incomes (Artiga, 2020; G. Jacobson et al., 2021) as larger shares of African American and Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries have lower education levels (not completing high school), family incomes below the poverty level, lower median per capita income, savings, and home equity (Ochieng, Cubanski, et al., 2021). Between 2009 and 2018, there was a 66% increase in enrollment among African American beneficiaries, a 43% increase among Hispanic beneficiaries, and a 101% increase among enrollees dually eligible with Medicaid (Meyers, Mor, et al., 2021). Additionally, over 50% of MA beneficiaries had an annual income of less than $30,000 (America’s Health Insurance Plans, 2019a), and similarly, there was a 60% increase among beneficiaries living in geographic areas with high deprivation (Meyers, Mor, et al., 2021).

Other factors that appear to be associated with MA enrollment include sex and health care utilization of beneficiaries (i.e., hospital, nursing home, or home health utilization; Meyers, Belanger, et al., 2019). There is a slightly higher proportion of female beneficiaries enrolled in MA compared to males (Tarazi et al., 2022). Historically, MA plans were less likely to enroll beneficiaries with chronic conditions (McWilliams et al., 2012) as payments to MA plan have been adjusted only minimally for clinical factors, leading to underpayments for those with chronic conditions. However, recent changes to the Hierarchical Condition Category Risk Adjustment Model (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2018) and the inclusion of special need plan options to improve care among MA beneficiaries with complex conditions (i.e., dual-eligible beneficiaries and people with dementia) may have increased enrollment among these beneficiaries (The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, 2018). Payments to MA plan do not account for social risk factors; however, this may still result in systematic underpayments for beneficiaries with social risk factors and incentivize MA plans to discourage their enrollment (Buntin & Ayanian, 2017). Thus, African American and Hispanic beneficiaries may be at a higher risk of disenrollment because these groups have higher rates of disability, cognitive impairment, and difficulties with activities of daily living (Ochieng, Cubanski, et al., 2021).

Beneficiaries with complex conditions who disenroll from MA into FFS may face gaps in health care services. Gaps in coverage are partially due to policy and state regulations that may negatively disadvantage racial and ethnic populations and other groups with low incomes. For instance, in many states Medigap insurers may refuse coverage among those with preexisting conditions due to medical underwriting if beneficiaries did not purchase a Medigap policy during the first 6 months of enrolling in Medicare Part B (Boccuti et al., 2018). Thus, beneficiaries with high needs may not have an alternative but to reenroll in MA to receive more comprehensive coverage options, especially in states without Medigap consumer protections (Boccuti et al., 2018; Meyers, Trivedi, et al., 2019). In fact, there has been an increase in switching from FFS to MA among people with complex chronic conditions (Holly, 2020).

Medicare Beneficiaries With Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias

The prevalence of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD) among Medicare beneficiaries has reached an all-time high; about 13% of Medicare beneficiaries have ADRD and are more likely to enroll in FFS Medicare (Jutkowitz et al., 2020). People with ADRD often face higher health care costs (Dwibedi et al., 2018). Compared to FFS beneficiaries with ADRD, MA enrollees with ADRD appear to have lower levels of health care utilization, including doctor visits, outpatient and inpatient hospital visits, and long-term care utilization (Park et al., 2020). However, there were no differences in care satisfaction and health status.

Although prior work has documented patterns of switching between FFS and MA overall (Meyers, Belanger, et al., 2019), limited studies have focused on understanding disenrollment from FFS to MA, especially among racial and ethnic groups with ADRD (Meyers, Rahman, et al., 2021; Park et al., 2019). ADRD prevalence is higher among African American (15%), followed by Hispanic (13%), and non-Hispanic White (12%) populations, which is reported as a major source of disparity in care and outcomes among the Medicare beneficiary population (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2020a). In addition, enrollment in MA plans among female beneficiaries with ADRD, and African American and Hispanic enrollees with ADRD appears to be about the same rate or higher than beneficiaries from these groups without ADRD (Park et al., 2020). Among beneficiaries with ADRD, MA disenrollment appears to be lower among females, and racial and ethnic groups with ADRD compared to their non-ADRD counterparts (Meyers, Rahman, et al., 2021).

Conceptual Framework

Behavioral economic frameworks suggest that making insurance-related decisions is a complicated process, and it may be more overwhelming among Medicare beneficiaries with complex chronic conditions and cognitive impairment (McWilliams et al., 2011; Rivera-Hernandez, Blackwood, Moody, et al., 2021). With a large number of options available to them, Medicare beneficiaries may experience difficulty making optimal choices among available plans (Abaluck & Gruber, 2011). However, broader structural and systemic inequalities, social and economic factors, chronic diseases, and disability may limit choices and constrain decision making among racial and ethnic groups, and between men and women (Artiga, 2020; Burkhart et al., 2020; Martino et al., 2021; Park, Langellier, et al., 2022; Park, Werner, et al., 2022). Cumulative disadvantages over the life course rooted in structural racism affect health care access and outcomes among racial and ethnic groups long before enrolling into the program (Ochieng, Cubanski, et al., 2021). While one study found that the rate of switching into MA was high for beneficiaries with newly diagnosed dementia (Park et al., 2019), there is no information regarding rates of switching from FFS to MA among African American and Hispanic beneficiaries with ADRD. Therefore, using data from all Medicare beneficiaries, our objectives were to assess racial and ethnic disparities in rates of switching to MA among FFS Medicare beneficiaries with ADRD. We also explored rates of switching after adjusting for demographic, geographic, and clinical characteristics and whether these rates vary by sex and dual eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid.

Method

Data and Study Population

Our main source of data for this study was the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File (MBSF) from 2017 and 2018. The MBSF includes demographic and enrollment characteristics, including MA/FFS enrollment status, of 100% of Medicare beneficiaries. In addition, we included information regarding beneficiaries’ chronic conditions/potentially disabling conditions and cost and utilization via the Chronic Conditions Segment, Other Chronic or Potentially Disabling Conditions Segment, and Cost and Utilization Segment (please see Research Data Assistance Center for more information about the data sets). Enrollment data were used to identify persons enrolled in FFS Medicare prior to 2018. In order to identify beneficiaries with ADRD diagnoses, we used data and algorithms from the chronic conditions segment (Chronic Condition Warehouse; CCW; Rahman et al., 2021). The reference period that the CCW uses to identify beneficiaries with ADRD is a 3-year lookback with at least one inpatient, outpatient, skilled nursing facility, home health agency, or carrier claim with any of the following diagnoses: F01.50, F01.51, F02.80, F02.81, F03.90, F03.91, F04, G13.8, F05, F06.1, F06.8, G30.0, G30.1, G30.8, G30.9, G31.1, G31.2, G31.01, G31.09, G94, R41.81, R54 (Rahman et al., 2021). In addition, the CCW includes the date when the criteria for ADRD diagnosis were met. We used this flag as year of ADRD diagnosis. We included all FFS Medicare beneficiaries enrolled during 2017 who survived at least until the start of 2018, were over 65, and that had an ADRD diagnosis. We excluded beneficiaries who died in 2017 as they would not have the ability to disenroll from FFS Medicare and enroll in a new MA plan in 2018. The researchers have access to these data under a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) data use agreement. The Brown University Institutional Review Board approved our use of these data.

Outcome

Our primary outcome of interest for this study was switching from FFS Medicare to MA at any month in 2018.

Predictors

The primary independent variable was race/ethnicity including non-Hispanic White (White hereafter), non-Hispanic African American (African American hereafter), and Hispanic beneficiaries. We used the Research Triangle Institute race/ethnicity variable in the MBSF, which has shown high sensitivity and specificity (Jarrín et al., 2020). Based on prior research, we adjusted for age categories (65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, 85–89, and older than 90 years), the number of common chronic and disabling conditions (see Supplementary Table A1 for the full list of these variables and distribution) categorized by quartiles, and total health care costs including outpatient, inpatient, post-acute care and other costs and categorized by quartiles for each study participant (Meyers, Belanger, et al., 2019; Meyers, Trivedi, et al., 2019).

Statistical Analysis

First, we described characteristics of beneficiaries who remained in FFS Medicare and those who switched to MA by race and ethnicity. We then fitted a linear regression model with all the predictors described above, year of ADRD diagnosis, and ZIP code fixed effects which enable us to compare beneficiaries who live in the same area and have the same theoretical access to MA plans to one another. We included two interaction terms in our analysis. The first interaction term was between race/ethnicity and dual eligibility to Medicare and Medicaid, as well as sex, as there may be differences in switching/disenrollment patterns among dual and nondual eligible to Medicare and Medicaid, and males and females. Dually eligible enrollees may switch plans or disenroll at any month during the year while nonduals are locked into their plan selections for the year (Meyers, Rahman, et al., 2021). In addition, dual-eligible beneficiaries have their premiums covered by Medicaid and face minimal cost-sharing and are more likely to have multiple chronic conditions, physical disability, and cognitive impairment (MedPAC & MACPAC, 2022). We also included a second interaction term between race and sex as there may be sex differences regarding switching/disenrollment patterns among racial and ethnic groups (Park, Langellier, et al., 2022). For all analyses, we used heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors. We reported model results as adjusted mean for switching rates among racial and ethnic groups by dual eligibility and sex using margins. Analyses were conducted using SAS and STATA.

Results

We identified 2,284,175 FFS Medicare beneficiaries with an ADRD diagnosis in 2017 (Table 1). About 84.92% of these beneficiaries were White, 9.26% were African American, and 5.83% were Hispanic. Beneficiaries from African American and Hispanic groups were slightly more likely to be younger (10.01%, 7.13%, and 5.20% of African American, Hispanic, and White were 65–69 years old), dual eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (50.15% African American, 59.47% Hispanic, and 23.44% White beneficiaries), and have higher number of chronic or potentially disabling conditions (21.03% African American, 20.54% Hispanic, and 16.02% White beneficiaries). Unadjusted results also showed that a higher proportion of African American and Hispanic beneficiaries switched to MA in 2018 (7.83% and 7.09%) compared to White beneficiaries (3.91%). All these differences were significant at p < .001.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of FFS Medicare Beneficiaries With ADRD in 2017 (N = 2,284,175)

| White (N = 1,939,696) | African American (N = 211,408) | Hispanic (N = 133,071) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Switched from FFS Medicare to MA, % | 3.91 | 7.83 | 7.09 | <.001 |

| Age, % | <.001 | |||

| 65–69 | 5.20 | 10.01 | 7.13 | |

| 70–74 | 12.23 | 15.80 | 14.18 | |

| 75–79 | 17.07 | 18.64 | 18.54 | |

| 80–84 | 21.09 | 20.57 | 21.96 | |

| 85–89 | 22.35 | 17.86 | 20.99 | |

| 90+ | 22.07 | 17.12 | 17.20 | |

| Female, % | 64.60 | 65.39 | 64.74 | <.001 |

| Dual eligibility, % | 23.44 | 50.15 | 59.47 | <.001 |

| Number of chronic or potentially disabling conditions, % | <.001 | |||

| Quartile 1 (0–2) | 38.14 | 20.75 | 22.27 | |

| Quartile 2 (3–4) | 31.99 | 30.99 | 30.35 | |

| Quartile 3 (5–6) | 23.85 | 27.24 | 26.85 | |

| Quartile 4 (7–16) | 16.02 | 21.03 | 20.54 | |

| Total costs, % | <.001 | |||

| Quartile 1 (0–6,504.68) | 25.70 | 24.43 | 24.92 | |

| Quartile 2 (6,504.71–17,547.81) | 25.69 | 23.82 | 23.92 | |

| Quartile 3 (17,547.85–41,505.41) | 25.16 | 24.28 | 25.20 | |

| Quartile 4 (41,505.49–4,114,921.00) | 23.45 | 27.47 | 25.96 |

Notes: ADRD = Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias; FFS = fee-for-service; MA = Medicare Advantage.

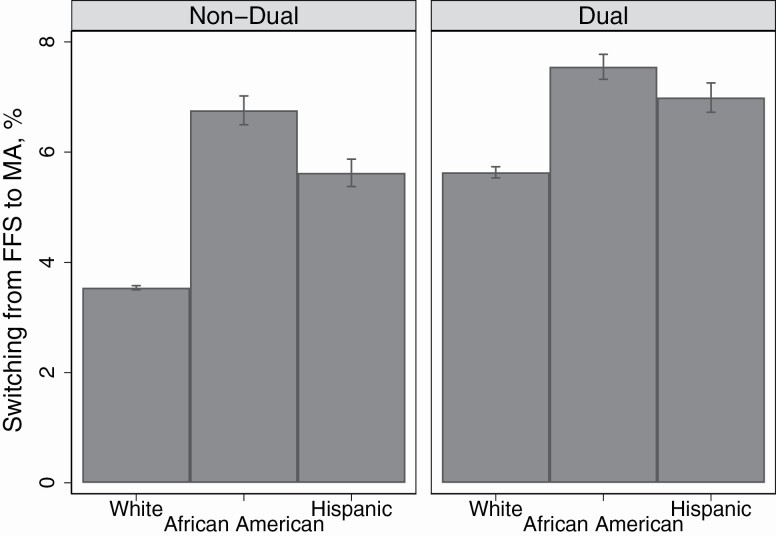

Figure 1 shows the adjusted mean switching rates among racial and ethnic groups by dual eligibility (full regression results are presented in Supplementary Table A2). Mean switching rates were significantly higher among African American dual-eligible beneficiaries (7.55%, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 7.32–7.77) followed by Hispanic dual-eligible beneficiaries (6.99%, 95% CI: 6.72–7.26) than White dual-eligible beneficiaries (5.63%, 95% CI: 5.53–5.74). However, when comparing switching rates among dual and nondual beneficiaries from the same racial and ethnic group, the widest gap was among White beneficiaries (2.09 p.p., 95% CI: 1.96–2.23) followed by Hispanic beneficiaries (1.37 p.p., 95% CI: 0.99–1.74) compared to African American dual-eligible and nondual-eligible beneficiaries (0.79 p.p., 95% CI: 0.40–1.18).

Figure 1.

Mean adjusted rates of switching to Medicare Advantage (MA) among fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, by race and ethnicity and dual-eligibility status.

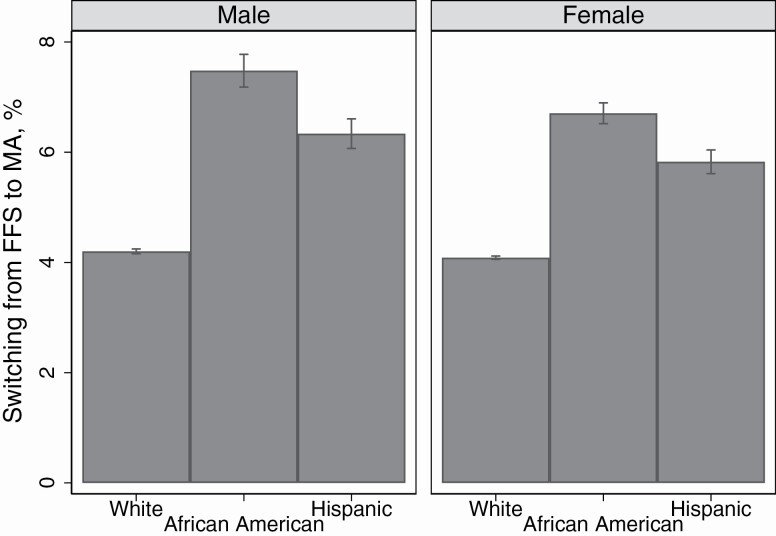

Figure 2 shows the adjusted mean switching rates among racial and ethnic groups by sex. Among male beneficiaries, switching rates were slightly higher among African American male beneficiaries (7.48%, 95% CI: 7.18–7.78) followed by Hispanic male beneficiaries (6.34%, 95 CI: 6.07–6.60) compared to White male beneficiaries (4.20%, 95 CI: 4.16–4.24). Similarly, the gap between males and females from the same racial and ethnic group was slightly higher among African American male beneficiaries (0.77 p.p., 95% CI: 0.47–1.07) followed by Hispanic male beneficiaries (0.51 p.p., 95% CI: 0.22–0.80) compared to White male and female beneficiaries (0.11 p.p., 95% CI: 0.05–0.17).

Figure 2.

Mean adjusted rates of switching to Medicare Advantage (MA) among fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, by race and ethnicity and sex.

Discussion

In this study of rates of switching to MA among FFS Medicare beneficiaries with ADRD, we found that overall African American and Hispanic enrollees with ADRD were substantially more likely to switch to MA compared to non-Hispanic White enrollees, even after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics. Surprisingly, dually eligible enrollees also had higher switching rates to MA compared to nonduals across groups, with the widest gap among non-Hispanic White beneficiaries. In addition, male beneficiaries had a slightly higher rate of switching to MA across groups, with the widest gap among African American male beneficiaries.

Our results are consistent with prior studies demonstrating greater MA enrollment among African American and Hispanic beneficiaries (Meyers, Mor, et al., 2021), which appear to be the case even among people with ADRD diagnoses. High switching from FFS Medicare to MA among racial and ethnic minority groups with ADRD—especially among male beneficiaries—may be related to preexisting health disparities and life-course disadvantages that are rooted in social determinants, and structural and systemic barriers (Artiga, 2020). In fact, insurance choice and supplemental coverage may be constraints among these groups (e.g., lack of financial access to Medigap policies among these groups). Compared to White beneficiaries, racial and ethnic groups have lower rates of enrollment in Medigap among FFS beneficiaries (Park et al., 2021). Without supplemental insurance coverage, FFS Medicare beneficiaries have no out-of-pocket limits as there is no ceiling for out-of-pocket expenses (Cubansk et al., 2018). Among all FFS Medicare enrollees, about one-third of them have Medigap plans (America’s Health Insurance Plans, 2019b). However, there are disparities in Medigap coverage by race and ethnicity, with African Americans and Hispanics being over 20% less likely to be enrolled in Medigap plans (Pourat et al., 2000).

In addition, a higher proportion of female beneficiaries across all groups are enrolled in a Medigap plan (Koma et al., 2021), which may explain the slightly higher rates of switching to MA among African American and Hispanic male beneficiaries. African American and Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries tend to have lower income than White beneficiaries, which may lead to low enrollment in Medigap and higher enrollment in MA (Park et al., 2021). Medigap premiums are costly (over $2,000), about four times more expensive than MA plans (Davis et al., 2019). If FFS Medicare beneficiaries do not sign up for a Medigap plan during the initial enrollment period, insurance companies can deny coverage based on preexisting conditions including ADRD (Meyers, Trivedi, et al., 2019). Restrictions that prevent individuals with ADRD and other preexisting conditions from obtaining supplemental coverage—as well as short enrollment periods—may encourage minority beneficiaries to switch to MA plans (Boccuti et al., 2018).

Moreover, supplemental benefits available in MA plans may be important drivers of enrollment among African American and Hispanic beneficiaries with ADRD, consistent with prior research (Medicare Advantage Plans, 2021; Rivera-Hernandez, Blackwood, Moody, et al., 2021). Some of these benefits include dental, vision, transportation, in-home support services, meal delivery, and prescription drug coverage (Medicare Advantage Plans, 2021). Since 2019, new supplemental benefits include updated primarily health-related definition and special supplemental benefits for the chronically ill (Center for Managed Care Solutions and Innovation, 2021). MA plans can offer other benefits including additional meal benefits, adult day care services, caregiver support, home modifications, nonmedical transportation, and transitional support (Kornfield et al., 2021). With lower premiums and a more comprehensive list of benefits to address social determinants of health, switching from FFS Medicare to MA may only increase among beneficiaries with ADRD (Murphy-Barron et al., 2020).

Rates of switching to MA among these groups may also partially be related to insurance broker availability to help older adults navigate a very complex system, as well as in-person preference for obtaining information. Racial and ethnic minority populations live in areas with higher proportion of MA beneficiaries, with potentially heavy MA advertising (Freed, Biniek, et al., 2022). Older adults have reported confusion about navigating the Medicare program and understanding insurance terminology (Rivera-Hernandez, Blackwood, Moody, et al., 2021), which may be higher among these groups. When choosing a plan, Medicare beneficiaries have to consider current and future health needs, health care preferences, and insurance costs, which may lead to people with cognitive impairment making suboptimal Medicare choices (Chan & Elbel, 2012). For instance, according to the CMS Plan Compare, premiums for an FFS beneficiary in 2022 in Los Angeles, CA, may include the standard Part B premium ($170.10), the drug plan premium ($7.50–$160.20), and the Medigap policy premium ($34.00–$1,104.00). Thus, if a drug plan (Part D) and supplemental insurance coverage (Medigap policy) are selected, the current total monthly premium for an FFS beneficiary ranges anywhere from $211.60 to $1,434.30 (Medicaid may contribute to dually eligible beneficiaries’ cost-sharing). On the other hand, an MA beneficiary in the same area pays the standard Part B premium of $170.10 and the MA plan premium, which ranges from $0.00 to $397.00. Thus, the current total monthly premium for a MA beneficiary ranges from $170.10 to $567.10. There are about 69 MA plans (107 including special need plans) in Los Angeles in 2022, with variations in quality star ratings, benefits, deductibles, and total out-of-pocket costs. Beneficiaries are more likely to compare monthly premiums than other plan characteristics (Miller, 2020; Park, Langellier, et al., 2022), which may partly explain the high proportion of zero-premium plans available in MA. Insurance brokers or representatives may reach out to more vulnerable older adults, take time to discuss and show them the costs and benefits of switching to MA and help them with the process (Rivera-Hernandez, Blackwood, Mercedes, et al., 2021). Looking at cumulative transitions, a recent report found that during 2013–2017, African American and Hispanic beneficiaries were less likely to remain in FFS Medicare than in MA for the entire period (Murphy-Barron et al., 2020).

Similarly, recent trends regarding overall MA enrollment have seen a significant increase among dual-eligible beneficiaries, with close to 45% of dual beneficiaries enrolling in MA plans and an overall increase of 125% from 2013 to 2019 (Holly, 2020; Murphy-Barron et al., 2020). In order to improve gaps in quality of care, CMS has established different mechanisms created to foster Medicare and Medicaid managed care integration including Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans (D-SNPs) and the MA Value-Based Insurance Design (MA-VBID) Model (Integrating Care through Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans (D-SNPs), 2019). These strategies have been implemented to improve quality of care for duals and high-cost and high-need patients, as well as reduce federal and state spending (The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, 2018). D-SNPs are available in all but nine states (Integrating Care through Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans (D-SNPs), 2019). SNPs are slightly more likely to offer benefits targeted for individual with chronic conditions (Kornfield et al., 2021). Only a limited number of MA plans—about 11% (369 MA plans and 89 MA-VBID)—are targeting services for enrollees with chronic conditions. For instance, about nine MA plans and one MA-VBID (81,628 and 5,810 beneficiaries, respectively) designed their benefits to better serve the needs of people with ADRD as opposed to diabetes or heart disease (Kornfield et al., 2021). It is possible that as MA plans increasingly offer a more comprehensive list of benefits, MA enrollment among people with ADRD will increase.

Our results have limitations. First, we focused our research question on FFS Medicare beneficiaries with an ADRD diagnosis who switched to MA. We excluded MA enrollees in 2017 because encounter claims data are not available for all MA enrollees, which limits our ability to accurately capture ADRD, chronic conditions, and costs among MA enrollees. Second, we characterized switching during any month in 2018 and we did not follow beneficiaries over time. Although most beneficiaries are subjected to “lock-in” provisions which limits how often most beneficiaries can change plans, duals are more likely to switch plans during the year (The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, 2018). Third, we do not have person-level information regarding socioeconomic status including income and education or information about beneficiary experiences, and measures of structural racism and racial discrimination that may influence individual’s choice of insurance coverage. Finally, these data do not capture the nuances and heterogeneity of experiences and reasons for switching from FFS Medicare into MA.

Our results have policy implications. Our finding that among FFS enrollees with ADRD, racial and ethnic minorities and those with dual eligibility have high rates of switching into MA suggests an imperative need to monitor the quality and equity of access and care for these enrollees. Current trends show that MA enrollment is expected to continue to grow, outpacing Medicare FFS (G. A. Jacobson & Blumenthal, 2022). Overall, MA beneficiaries appeared to be generally satisfied with their current coverage (Ochieng, Biniek, et al., 2021). However, there is less information regarding care satisfaction and patient experience among beneficiaries with ADRD and whether disparities exist among these beneficiaries. Racial and ethnic beneficiaries with ADRD are underrepresented in surveys regarding health care experiences, but among beneficiaries with ADRD and/or family members who responded to the Medicare Advantage Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems were more likely to report worse experiences with care in the MA program (Meyers et al., 2022). Greater availability of MA claims and accurate representation of people with ADRD is needed. Finally, CMS emphasizes “choice” among Medicare beneficiaries, but complex Medicare choices may disincentivize/discourage beneficiaries with ADRD to switch to MA and/or beneficiaries with ADRD may be less likely to select optimal choices (Chan & Elbel, 2012; McWilliams et al., 2011). In addition, racial and ethnic minority groups with a long history of discrimination and structural racism may face more constraints while choosing a plan (Artiga, 2020). High-rated MA plans, measured by a 5-star rating system, are less likely to be available to racial and ethnic minority beneficiaries than White beneficiaries (Park, Werner, et al., 2022). This suggests that differences in enrollment in high-rated MA plans by race and ethnicity may be partly attributable to limited access and not solely related to individual characteristics or enrollment decisions (Park, Werner, et al., 2022). While Medicare has decreased the gap in access to health care and outcomes, more efforts are needed to continue to advance social determinants of health and health equity (Wallace et al., 2021). Our findings highlight the importance of funding for programs (e.g., the State Health Insurance Assistance Program) that provide free and unbiased Medicare counseling and guidance for family members and/or Medicare beneficiaries with (and without) ADRD to navigate a very complex Medicare system with an overwhelming number of choices. In addition, our study provides further support for improved data collection of race and ethnicity among Medicare beneficiaries to identify disparities in plan selection within MA (Haley et al., 2022).

Conclusion

Among Medicare beneficiaries with ADRD, African American and Hispanic enrollees are more likely to switch from FFS to MA. We also found racial and ethnic variations by dual eligibility and sex. African American dually eligible beneficiaries showed higher rates of switching to MA; however, the widest gap was evident among non-Hispanic White beneficiaries when comparing dually eligible beneficiaries to nondual-eligible beneficiaries from the same racial or ethnic group. Finally, overall male beneficiaries had a slightly higher rate of switching to MA across groups, with higher rates of switching among African American males and the widest gap among African American male beneficiaries when compared to their female counterparts. Plan “choice” among Medicare beneficiaries may be constrained by multiple factors including structural and systemic inequalities. More information about why these beneficiaries may be switching to MA, as well as whether care needs are being met, is needed. There is an important need to monitor the quality and equity of access and care for these enrollees.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Maricruz Rivera-Hernandez, Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice, School of Public Health, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, USA; Center for Gerontology and Healthcare Research, School of Public Health, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, USA.

David J Meyers, Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice, School of Public Health, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, USA; Center for Gerontology and Healthcare Research, School of Public Health, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, USA.

Daeho Kim, Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice, School of Public Health, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, USA; Center for Gerontology and Healthcare Research, School of Public Health, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, USA.

Sungchul Park, Department of Health Policy and Management, College of Health Science, Korea University, Seoul, Republic of Korea; BK21 Four R&E Center for Learning Health Systems, Korea University, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Amal N Trivedi, Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice, School of Public Health, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, USA; Center for Gerontology and Healthcare Research, School of Public Health, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, USA.

Funding

The study was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (K01AG057822; P01AG027296).

Conflict of Interest

M. Rivera-Hernandez reported receiving grants form the National Institute on Aging during the conduct of the study. D. J. Meyers reported receiving grants from the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities outside the submitted work. A. M. Trivedi reported receiving grants from the National Institute on Aging during the conduct of the study and receiving grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Department of Veterans Affairs outside the submitted work.

Author Contributions

M. Rivera-Hernandez planned the study, performed the data analysis, and wrote the paper. All authors helped to plan the study and to revise the manuscript.

References

- Abaluck, J., & Gruber, J. (2011). Choice inconsistencies among the elderly: Evidence from plan choice in the Medicare Part D program. The American Economic Review, 101(4), 1180–1210. doi: 10.1257/aer.101.4.1180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- America’s Health Insurance Plans. (2019a). Medicare Advantage demographics report, 2016. https://www.ahip.org/wp-content/uploads/MA_Demographics_Report_2019.pdf

- America’s Health Insurance Plans. (2019b). State of Medigap 2019: Trends in enrollment and demographics. https://www.ahip.org/wp-content/uploads/IB_StateofMedigap2019.pdf

- Artiga, S. (2020, June 1). Health disparities are a symptom of broader social and economic inequities. KFF. https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/health-disparities-symptom-broader-social-economic-inequities/ [Google Scholar]

- Boccuti, C., Jacobson, G., Orgera, K., & Newman, T. (2018, July 11). Medigap enrollment and consumer protections vary across states. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medigap-enrollment-and-consumer-protections-vary-across-states/ [Google Scholar]

- Buntin, M. B., & Ayanian, J. Z. (2017). Social risk factors and equity in Medicare payment. The New England Journal of Medicine, 376(6), 507–510. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1700081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart, Q., Elliott, M. N., Haviland, A. M., Weech-Maldonado, R., Wilson-Frederick, S. M., Gaillot, S., Dembosky, J. W., Edwards, C. A., & MacCarthy, S. (2020). Gender differences in patient experience across Medicare Advantage plans. Women’s Health Issues, 30(6), 477–483. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2020.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Managed Care Solutions and Innovation. (2021). Medicare Advantage & the new supplemental benefits explained for CY2020. https://www.leadingage.org/sites/default/files/Medicare%20Advantage%20%26%20New%20Suppplemental%20Benefits%20Explained%20for%20CY2020%20FINAL.pdf

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2018). CMS risk adjustment. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/Risk-Adjustors [PubMed]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2020a). Alzheimer’s disease disparities in Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries. https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/OMH/Downloads/OMHDataSnapshot_Alzheimers_Final_508.pdf [PubMed]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2020b). Trump administration announces changes to Medicare Advantage and Part D to provide better coverage and increase access for Medicare beneficiaries. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/trump-administration-announces-changes-medicare-advantage-and-part-d-provide-better-coverage-and [PubMed]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2020c). Understanding Medicare Advantage plans. https://www.medicare.gov/Pubs/pdf/12026-Understanding-Medicare-Advantage-Plans.pdf [PubMed]

- Chan, S., & Elbel, B. (2012). Low cognitive ability and poor skill with numbers may prevent many from enrolling in Medicare supplemental coverage. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 31(8), 1847–1854. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubansk, J., Damico, A., Neuman, T., & Jacobson, G. (2018, November 28). Sources of supplemental coverage among Medicare beneficiaries in 2016. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/sources-of-supplemental-coverage-among-medicare-beneficiaries-in-2016/ [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K., Willink, A., & Schoen C. (2019). How the erosion of employer-sponsored insurance is contributing to Medicare beneficiaries’ financial burden. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2019/jul/erosion-employer-sponsored-insurance-medicare-financial-burden

- Dwibedi, N., Findley, P. A., Wiener R, C., Shen, C., & Sambamoorthi, U. (2018). Alzheimer disease and related disorders and out-of-pocket health care spending and burden among elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Medical Care, 56(3), 240–246. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freed, M., Biniek, J. F., Damico, A., & Neuman, T. (2022, August 25). Medicare Advantage in 2022: Enrollment Update and Key Trends. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-in-2022-enrollment-update-and-key-trends/ [Google Scholar]

- Haley, J. M., Dubay, L., Garrett, B., Caraveo, C. A., Schuman, I., Johnson, K., Hammersla, J., Klein, J., Bhatt, J., Rabinowitz, D., Nelson, H., & DePoy, B. (2022). Collection of race and ethnicity data for use by health plans to advance health equity. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/collection-race-and-ethnicity-data-use-health-plans-advance-health-equity [Google Scholar]

- Holly, R. (2020, October 19). Medicare Advantage enrollment up 125% among dual-eligible beneficiaries.Home Health Care News. https://homehealthcarenews.com/2020/10/medicare-advantage-enrollment-up-125-among-dual-eligible-beneficiaries/ [Google Scholar]

- Integrating Care through Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans (D-SNPs): Opportunities and challenges. (2019, April 8). ASPE. https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/integrating-care-through-dual-eligible-special-needs-plans-d-snps-opportunities-and-challenges [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, G., Cicchiello, A., Sutton, J. P., & Shah, A. (2021). Medicare Advantage vs. traditional Medicare: How do beneficiaries’ characteristics and experiences differ? Commonwealth Fund. doi: 10.26099/yxq0-1w42 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, G. A., & Blumenthal, D. (2022). Medicare Advantage enrollment growth: Implications for the US health care system. JAMA, 327(24), 2393–2394. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.8288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, G. A., Neuman, P., & Damico, A. (2015). At least half of new Medicare Advantage enrollees had switched from traditional Medicare during 2006–11. Health Affairs, 34(1), 48–55. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrín, O. F., Nyandege, A. N., Grafova, I. B., Dong, X., & Lin, H. (2020). Validity of race and ethnicity codes in Medicare administrative data compared with gold-standard self-reported race collected during routine home health care visits. Medical Care, 58(1), e1. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutkowitz, E., Bynum, J. P. W., Mitchell, S. L., Cocoros, N. M., Shapira, O., Haynes, K., Nair, V. P., McMahill-Walraven, C. N., Platt, R., & McCarthy, E. P. (2020). Diagnosed prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in Medicare Advantage plans. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring, 12(1), e12048. doi: 10.1002/dad2.12048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koma, W., Cubanski, J., & Neuman, T. (2021, March 23). A snapshot of sources of coverage among Medicare beneficiaries in 2018. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/a-snapshot-of-sources-of-coverage-among-medicare-beneficiaries-in-2018/ [Google Scholar]

- Kornfield, T., Kazan, M., Frieder, M., Duddy-Tenbrunsel, R., Donthi, S., & Fix, A. (2021). Medicare Advantage plans offering expanded supplemental benefits: A look at availability and enrollment. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2021/feb/medicare-advantage-plans-supplemental-benefits

- Martino, S. C., Elliott, M. N., Dembosky, J. W., Hambarsoomian, K., Klein, D. J., Gildner, J., & Haviland, A. (2021). Racial, ethnic, and gender disparities in health care in Medicare Advantage: April 2021. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Website (2021). https://www.rand.org/pubs/external_publications/EP68733.html [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, J. M., Afendulis, C. C., McGuire, T. G., & Landon, B. E. (2011). Complex Medicare advantage choices may overwhelm seniors—Especially those with impaired decision making. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 30(9), 1786–1794, doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, J. M., Hsu, J., & Newhouse, J. P. (2012). New risk-adjustment system was associated with reduced favorable selection in Medicare Advantage. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 31(12), 2630–2640. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicare Advantage Plans. (2021). New study shows why the coronavirus pandemic is leading many Americans to enroll in a Medicare Advantage plan for 2021. MedicareAdvantagePlans.Org. https://www.medicareadvantageplans.org/medicare-advantage-plans-2021-coronavirus-survey/ [Google Scholar]

- MedPAC & MACPAC. (2022). Data book: Beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Beneficiaries-Dually-Eligible-for-Medicare-and-Medicaid-February-2022.pdf

- Meyers, D. J., Belanger, E., Joyce, N., McHugh, J., Rahman, M., & Mor, V. (2019). Analysis of drivers of disenrollment and plan switching among Medicare Advantage beneficiaries. JAMA Internal Medicine, 179(4), 524–532. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, D. J., Mor, V., Rahman, M., & Trivedi, A. N. (2021). Growth in Medicare Advantage greatest among Black and Hispanic enrollees. Health Affairs, 40(6), 945–950. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, D. J., Rahman, M., Rivera-Hernandez, M., Trivedi, A. N., & Mor, V. (2021). Plan switching among Medicare Advantage beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Alzheimer’s & Dementia (New York, N.Y.), 7(1), e12150. doi: 10.1002/trc2.12150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, D. J., Rivera-Hernandez, M., Kim, D., Keohane, L. M., Mor, V., & Trivedi, A. N. (2022). Comparing the care experiences of Medicare Advantage beneficiaries with and without Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 70(8), 2344–2353. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, D. J., Trivedi, A. N., & Mor, V. (2019). Limited Medigap consumer protections are associated with higher reenrollment in Medicare Advantage plans. Health Affairs, 38(5), 782–787. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M. (2020, November 13). When Medicare choices get “pretty crazy,” many seniors avert their eyes. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/13/business/medicare-advantage-retirement.html [Google Scholar]

- Murphy-Barron, C., Pyenson, B., Ferro, C., & Emery, M. (2020). Comparing the demographics of enrollees in Medicare advantage and fee-for-service Medicare. Better Medicare Alliance, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ochieng, N., Biniek, J. F., Schwartz, K., & Newman, T. (2021, May 17). Medicare-covered older adults are satisfied with their coverage, have similar access to care as privately-insured adults ages 50 to 64, and fewer report cost-related problems—Issue brief. KFF. https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicare-covered-older-adults-are-satisfied-with-their-coverage-have-similar-access-to-care-as-privately-insured-adults-ages-50-to-64-issue-brief/ [Google Scholar]

- Ochieng, N., Cubanski, J., Neuman, T., Artiga, S., & Damico A. (2021, February 16). Racial and ethnic health inequities and Medicare.KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicare/report/racial-and-ethnic-health-inequities-and-medicare/ [Google Scholar]

- Park, S., Fishman, P., White, L., Larson, E. B., & Coe, N. B. (2019). Disease-specific plan switching between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage. The Permanente Journal, 24, 19.059. doi: 10.7812/TPP/19.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, S., Langellier, B. A., & Meyers, D. J. (2022). Association of health insurance literacy with enrollment in traditional Medicare, Medicare Advantage, and plan characteristics within Medicare Advantage. JAMA Network Open, 5(2), e2146792. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.46792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, S., Meyers, D. J., & Rivera-Hernandez, M. (2021). Enrollment in supplemental insurance coverage among Medicare beneficiaries by race/ethnicity. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 9(5), 2001–2010. doi: 10.1007/s40615-021-01138-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, S., Werner, R. M., & Coe, N. B. (2022). Racial and ethnic disparities in access to and enrollment in high-quality Medicare Advantage plans. Health Services Research, 1–11. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, S., White, L., Fishman, P., Larson, E. B., & Coe, N. B. (2020). Health care utilization, care satisfaction, and health status for Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare beneficiaries with and without Alzheimer disease and related dementias. JAMA Network Open, 3(3), e201809. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourat, N., Rice, T., Kominski, G., & Snyder, R. E. (2000). Socioeconomic differences in Medicare supplemental coverage. Health Affairs, 19(5), 186–196. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.5.186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M., White, E. M., Mills, C., Thomas, K. S., & Jutkowitz, E. (2021). Rural–urban differences in diagnostic incidence and prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 17(7), 1213–1230. doi: 10.1002/alz.12285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Hernandez, M., Blackwood, K. L., Mercedes, M., & Moody, K. A. (2021). Seniors don’t use Medicare.Gov: How do eligible beneficiaries obtain information about Medicare Advantage plans in the United States? BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 146. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06135-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Hernandez, M., Blackwood, K. L., Moody, K. A., & Trivedi, A. N. (2021). Plan switching and stickiness in Medicare Advantage: A qualitative interview with Medicare Advantage beneficiaries. Medical Care Research and Review, 78(6), 693–702. doi: 10.1177/1077558720944284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarazi, W., Welch, W. P., Nguyen, N., Bosworth, A., Sheingold, S., Lew, N. D., & Sommers, B. D. (2022). Medicare beneficiary enrollment trends and demographic characteristics. “ASPE” https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/f81aafbba0b331c71c6e8bc66512e25d/medicare-beneficiary-enrollment-ib.pdf

- The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. (2018). Managed care plans for dual-eligible beneficiaries (Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System). https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/import_data/scrape_files/docs/default-source/reports/jun18_ch9_medpacreport_sec.pdf [PubMed]

- Wallace, J., Jiang, K., Goldsmith-Pinkham, P., & Song, Z. (2021). Changes in racial and ethnic disparities in access to care and health among US adults at age 65 years. JAMA Internal Medicine, 181(9), 1207–1215. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.3922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.