Abstract

Macrocyclic retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor C2 (RORC2) inverse agonists have been designed with favorable properties for topical administration. Inspired by the unanticipated bound conformation of an acyclic sulfonamide-based RORC2 ligand from cocrystal structure analysis, macrocyclic linker connections between the halves of the molecule were explored. Further optimization of analogues was accomplished to maximize potency and refine physiochemical properties (MW, lipophilicity) best suited for topical application. Compound 14 demonstrated potent inhibition of interleukin-17A (IL-17A) production by human Th17 cells and in vitro permeation through healthy human skin achieving high total compound concentration in both skin epidermis and dermis layers.

Keywords: RORC2, RORγt, structure-based design, macrocyclization, topical delivery

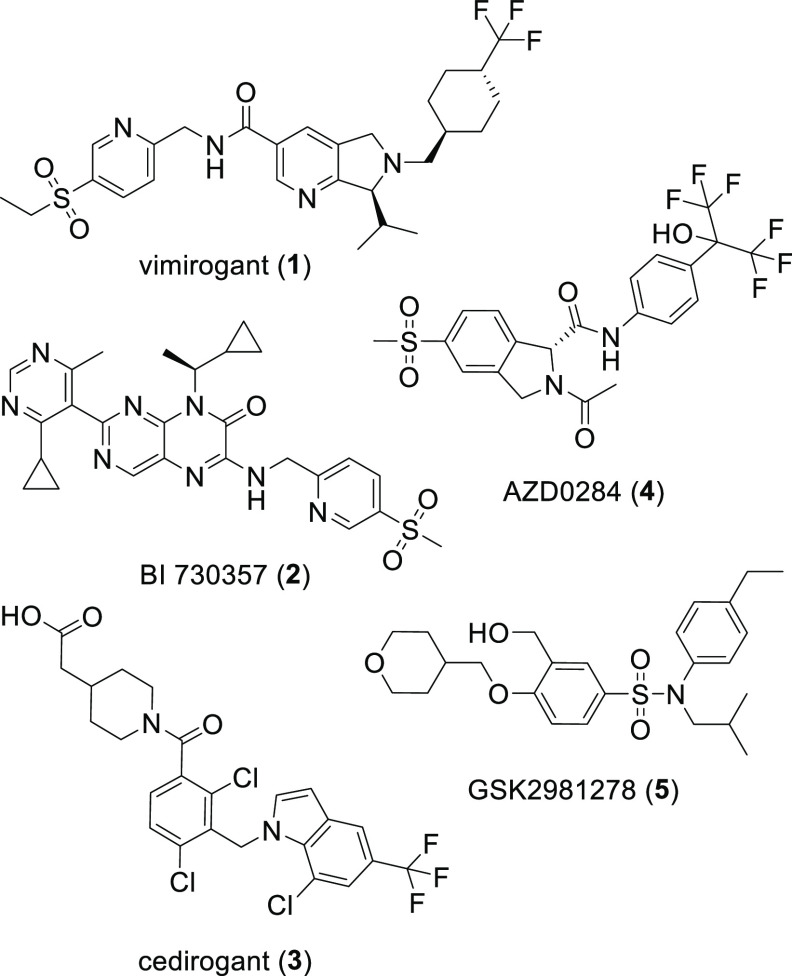

Retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor C2 (RORC2, RORγt) is a nuclear hormone receptor responsible for the expression of interleukin-17A (IL-17A) and IL-17F, which are secreted by T-helper 17 (Th17) cells.1 IL-17A is a potent proinflammatory cytokine.2 Monoclonal antibody therapies that neutralize IL-17A (secukinumab and ixekizumab) or block its corresponding receptor (brodalumab) have been found to be highly efficacious in the treatment of psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis.3−7 Small molecule inverse agonists to RORC2 have been shown to inhibit in vitro production of IL-17A in Th17 cells and have demonstrated efficacy in preclinical models of psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and multiple sclerosis.8−11 A wide diversity of structural chemistry has yielded potent RORC2 inverse agonists resulting in several oral clinical drug candidates (1–4)12−14 as well as clinical candidates administered through topical delivery specific to the treatment of psoriasis (5), Figure 1.15−17 The oral RORC2 inverse agonist vimirogant (1) was reported to reduce disease severity in a small cohort of patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis.12 Topical administration of an RORC2 inverse agonist may offer advantages in patient convenience and safety; however, despite such agents having apparently entered into clinical trials, to date, a similar report of early clinical efficacy has not appeared.

Figure 1.

Representative RORC2 inverse agonists that have entered human clinical trials delivered through oral dosing (1–4) or topical application (5).

The design of topically administered drugs targeting the skin as the site of action offers unique challenges compared to their orally delivered counterparts. The drug must traverse skin layers with differing properties including the stratum corneum, epidermis, and dermis. As a result, physiochemical properties play an important role. Seminal work by Potts and Guy18 has suggested an inverse relationship between the maximum flux of a chemical compound across the skin with its molecular weight. On the other hand, the extent of absorption of chemical compounds into intact skin was shown to follow a bell-shaped curve as a function of compound lipophilicity with a maximum between LogD 2–3.19 In contrast to oral drugs, high systemic clearance is usually desirable for topical agents in order to limit compound exposure in the body beyond the skin. The ideal combination of these attributes has been challenging to align with potency for RORC2 inverse agonists as the receptor tends to favor larger, more lipophilic molecules. For example, topical drug candidate 5 resides outside the likely ideal range (MW = 461.6 Da, LogD = 5.0). Therefore, novel approaches to efficiently engage the binding site with more compact and less lipophilic ligands are needed. Herein, we report the first example of a macrocyclic RORC2 inverse agonist to address these needs and the resulting characterization supporting favorable properties toward topical administration.

Looking to identify RORC2 ligands with a minimum molecular weight profile, our attention was drawn to a previous report20 describing a series of benzylpiperazines including compound 6, Table 1. The report that compound 6 was able to permeate human skin after topical administration in an in vitro percutaneous study was also very promising.20 We had identified a similar screening hit except that the aryl ring was substituted by a sulfonamide instead of the 3-cyanobenzamide as in compound 6. Curious to explore the impact of transforming the amide of 6 into a sulfonamide, we surveyed a range of substituted benzenesulfonamides and subsequently identified that 4-fluorobenzenesulfonamide provided favorable potency as shown in compound 7a, Table 1. Compounds 6 and 7a displayed potent inhibition of steroid receptor coactivator 1 isoform 2 (SRC1-2) peptide binding to histidine-tagged RORC2-LBD in a time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET) assay. Both compounds also inhibited production of IL-17 by human primary Th17 cells. Indeed, sulfonamide 7a was about 2-fold more potent than the amide in both assays. Both compounds displayed high in vitro clearance in human liver microsomes (HLMs), a desirable feature for topically delivered agents. The sulfonamide analog 7a did show diminished passive permeability (RRCK MDCKII-LE cell monolayer) and higher lipophilicity than amide 6. Both compounds also demonstrated low micromolar binding to the hERG ion channel based on a radiolabeled dofetilide displacement binding assay.

Table 1. Representative Benzylpiperazine RORC2 Inverse Agonistsa.

| IC50 (nM) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | R | RORC2b | IL-17c | HLM CLint,a (μL/min/mg) | RRCKd Papp (10–6 cm/s) | DOFeKi (μM) | LogDf |

| 6 | 5.4 | 16 | 239 | 6.5 | 3.6 | 4.5 | |

| 7a | cPentyl | 2.1 | 6.5 | 68 | 1.3 | 4.0 | 5.3 |

| 7b | CH2cPr | 12 | 141 | 53 | 4.5 | 1.8 | 4.7 |

All values are the mean of two or more independent assays.

TR-FRET cofactor recruitment.

Inhibition of IL-17A production by human Th17 cells.

Passive permeability measured using RRCK (MDCKII-LE) cell monolayer.

[3H]dofetilide displacement binding assay.

LogD pH 7.4 measured by reverse phase HPLC.

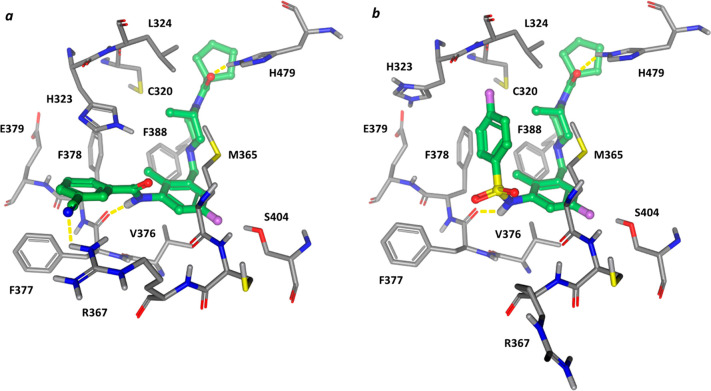

An X-ray cocrystal structure of amide 6 has been reported;21 however, a C-terminus SRC2-RORC2 LBD fusion construct was employed resulting in a physiologically inconsistent coactivator-bound active receptor conformation. We cocrystallized both compounds 6 and 7a with the RORC2 LBD in the presence of an allosteric ligand22 to stabilize helix-12 in an inactive conformation (see the Supporting Information), Figure 2. Both ligands bound to the putative endogenous ligand binding pocket. The carbonyl of the cyclopentylamide formed a hydrogen bond with H479 disrupting the triplet residue latch (H479–Y502–F506) that constrains helix-12 in the agonist conformation. The fluorine substituent to the central phenyl ring makes a close contact with the hydroxy group of S404, and the aniline nitrogen for both the amide of 6 and sulfonamide of 7a forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonyl of F377. The key difference in the binding pose for the two molecules is the orientation of the amide versus the sulfonamide. The amide of compound 6 adopts an extended conformation reaching into a subpocket with the cyano substituent forming a hydrogen bond contact with R367. On the other hand, the sulfonamide substituent of compound 7a occupies the large cavity above the ligand formed by the displacement of H323, which now forms an intraprotein salt bridge with E379. The observed eclipsing conformation of the sulfonamide H–N–S–O dihedral (0.5°) is consistent with the preferred conformation of this fragment in the Cambridge Crystallographic Database.23 This conformation places the fluorophenyl ring in close proximity (3.5 Å) to the piperazine methyl substituent, which adopts an axial orientation.

Figure 2.

Cocrystal structure of the RORC2 LBD with (a) compound 6 (8FAV) and (b) compound 7a (8FB1). Key residues in the binding pocket are labeled.

Unfortunately, the increased molecular weight and lipophilicity imparted by the sulfonamide ran counter to our objectives to target a more topical formulation favorable physiochemical profile. The close proximity of the sulfonamide aryl and the piperazine methyl suggested the potential that a macrocyclic ring could efficiently occupy the hydrophobic pocket in a more atom economical fashion. Therefore, we set out to prepare several different macrocyclic variants to test this hypothesis, Table 2. We chose to use a piperazine cyclopropylmethyl amide for this study as the corresponding acyclic compound 7b (Table 1) was slightly less potent than 7a and provided a better dynamic range in our assays should we see potency improvements due to macrocyclization. Modeling suggested that a five-atom spacer between the sulfur atom and the piperazine ring would limit overall ring strain. Indeed, the five methylene analogue 9 demonstrated comparable inhibition of IL-17 production to that seen with the acyclic reference 7b while the four methylene variant 10 was significantly less potent. Replacement of one methylene unit by oxygen as in compound 11 was also detrimental, resulting in a 2-fold reduction of potency in both the TR-FRET and IL-17 production assays. In addition to sulfonamide-based macrocycles, sulfamides were also evaluated. Although the unsubstituted nitrogen analogue 12 was inferior in potency to the methylene equivalent 9, the N-methyl analogue 13 was found to be a 2-fold more potent inhibitor of IL-17 production. Notably, passive permeability for the lead macrocycles 9 and 13 was significantly improved compared to the acyclic variant 7b, and high clearance in human liver microsomes was retained.

Table 2. Optimization of Macrocyclic Linker Length and Functionalitya.

| IC50 (nM) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | R | X | Y | RORC2b | IL-17c | HLM CLint,a (μL/min/mg) | RRCKd Papp (10–6 cm/s) | LogDe |

| 8 | H | CH2 | CH2 | 2400 | >10 000 | 80 | 11.7 | 3.6 |

| 9 | CH3 | CH2 | CH2 | 69 | 55 | 260 | 12.4 | 3.2 |

| 10 | CH3 | CH2 | 620 | 2600 | 71 | 24.7 | 3.3 | |

| 11 | CH3 | CH2 | O | 120 | 110 | 55 | ND | 2.1 |

| 12 | CH3 | NH | CH2 | 150 | 170 | 160 | 18.4 | 2.9 |

| 13 | CH3 | NCH3 | CH2 | 14 | 26 | >320 | 21.0 | 3.5 |

All values are the mean of two or more independent assays. ND, not determined. All compounds were isolated as a racemic mixture.

TR-FRET cofactor recruitment.

Inhibition of IL-17A production by human Th17 cells.

Passive permeability measured using RRCK (MDCKII-LE) cell monolayer.

LogD pH 7.4 measured by reverse phase HPLC.

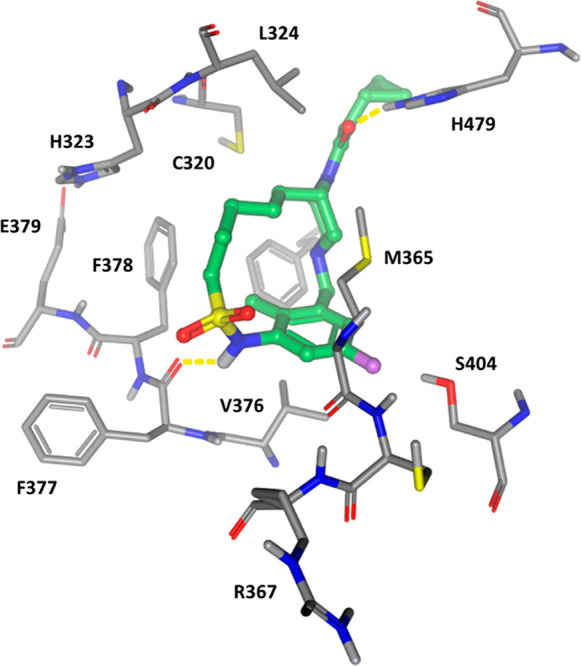

A cocrystal structure of compound 9 with the RORC2 LBD confirmed that the ligand binding mode mimics that of the acyclic analogue, Figure 3. Hydrogen bond contacts between residue H479 and the piperazine amide carbonyl as well as the backbone carbonyl of F377 and the sulfonamide NH were maintained in the macrocyclic analog. The favorable sulfonamide conformation resulting from an eclipsed H–N–S–O dihedral (8.1°) was also retained in the bound structure. The macrocyclic methylene linker now occupies the binding site void region above the plane of the toluene ring displacing H323 from the pocket.

Figure 3.

Cocrystal structure of the RORC2 LBD with compound 9 (8FB2). Key residues in the binding pocket are labeled.

The methyl substituent of the central 4-fluorotoluene ring was found to be an important structural element for potency as shown by des-methyl analogue 8 (IL-17 IC50 > 10 μM), Table 2. This effect was also seen in the acyclic series, suggesting it is not a consequence of steric rigidification by the macrocyclic ring. The methyl group is most likely inducing a ground state conformation of the molecule that more closely resembles the bound conformation, a similar effect we previously observed for indole amide RORC2 inverse agonists.8 Torsion analysis indeed suggests the methyl group significantly restricts the conformational space accessible to both the sulfonamide and benzylic amine substituents of the phenyl ring (Figure S1). The methyl substituent also likely provides favorable hydrophobic interactions with residues F378 and F388 in the binding site, which may also contribute to the enhanced potency.

Further optimization of 9 was pursued since it had the best balance of potency, lipophilicity, and low molecular weight identified from this survey. The uncertain metabolic fate for the methylsulfamide 13, potentially affording the active metabolite 12, was also a factor in this decision. Additional screening of the piperazine amide substituent indicated that the molecular size could be further truncated to the isopropyl amide while maintaining good potency as shown for compound 15, Table 3. The ligand interaction with S404 was also explored by replacing fluorine with hydrogen, chlorine, and a cyano substituent. Surprisingly, the hydrogen analogue 14 maintained good inhibition of IL-17 production, and the cyano derivative 17 behaved similarly. The chlorine analogue however showed a significant improvement in IL-17 inhibition compared to the other analogs (IC50 = 2.2 nM). The overall trend though suggests lipophilicity as the primary driver of potency rather than a specific halogen-hydrogen bond contact with S404 as the lipophilic efficiency (LIPE) for 16 (R = Cl, LIPE = 4.35) is similar to that of 14 (R = H, LIPE = 4.15). Again, the macrocyclic derivatives demonstrated consistently good passive permeability and appeared to offer a benefit in reduced hERG channel binding compared to the acyclic analogs. From a perspective of topical administration, compound 14 offered the most favorable combination of low molecular weight, moderate lipophilicity, and the combination of high passive permeability and predicted systemic clearance. Therefore, more detailed pharmacological profiling of 14 was pursued including its suitability for topical delivery.

Table 3. Influence of Halogen Substituent on Potency, ADME Properties, and in Vitro Safety Pharmacologya.

| IC50 (nM) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | R | RORC2b | IL-17c | HLM CLint,a (μL/min/mg) | RRCKd Papp (10–6 cm/s) | DOFeKi (μM) | LogDf |

| 14 | H | 9.3 | 28 | 223 | 24 | 37 | 3.4 |

| 15 | F | 5.2 | 87 | 205 | 19 | 19 | 3.8 |

| 16 | Cl | 2.4 | 2.2 | 200 | 17 | 11 | 4.3 |

| 17 | CN | 27 | 65 | 130 | 22 | 17 | 2.9 |

All values are the mean of two or more independent assays.

TR-FRET cofactor recruitment.

Inhibition of IL-17A production by human Th17 cells.

Passive permeability measured using RRCK (MDCKII-LE) cell monolayer.

[3H]dofetilide displacement binding assay.

LogD pH 7.4 measured by reverse phase HPLC.

Compound 14 showed no significant inverse agonism toward the most closely related nuclear hormone receptors to RORC2, RORA and RORB, in the TR-FRET assay (IC50 > 25 μM). Broad nuclear hormone receptor profiling was performed using the trans-FACTORIAL platform (Attagene Inc.). This multiplexed technology allows for the measurement of reporter RNA levels upon transfection of ligand binding domain chimeric constructs from 48 nuclear receptors with GAL4 DNA. Of the 48 receptors, only RORC2 showed a fold reduction (antagonist effect) of greater than 20% of control at a dose of 1 and 10 μM compound (Figure S2). Only the pregnane X receptor (PXR) showed a modest fold increase (agonist effect) greater than 20% of control at the 10 μM dose (2.04-fold, p = 0.0003). This level of PXR modulation was not viewed as a concern since the systemic exposure of 14 following topical administration was expected to be very low. Overall, these results demonstrate the high selectivity of compound 14 for RORC2 compared to all other nuclear receptors.

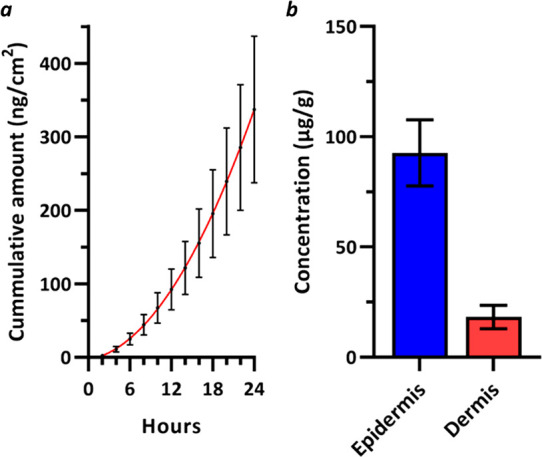

In order for a topical RORC2 inverse agonist to achieve a pharmacological effect, the compound should be able to penetrate the skin and deliver significant compound exposure to the dermis. Compound penetration into the skin was assessed through an in vitro permeation study where a topical formulation of 14 was applied to the outer surface of excised human abdominal skin placed in a flow-through Franz diffusion cell. The cumulative amount of compound 14 present in the receiver solution was monitored over a period of 24 h, Figure 4a. At the end of the experiment, the epidermis and dermis layers of the skin sample were separated and homogenized, and the concentration of compound 14 present was measured, Figure 4b. Although excess compound on the skin surface is removed prior to skin layer separation, the risk of inadvertent contamination to the skin sublayers cannot be completely excluded. Macrocycle 14 achieved a peak compound flux through the skin of 28.1 ng/cm2/h (SEM = 7.7), which is significantly higher than the reported flux for the acyclic progenitor 6 (3.4 ng/cm2/h).20 High total compound concentrations of 14 were also identified in both the skin epidermis (92.7 μg/g, SEM = 15.0) and dermis layers (18.3 μg/g, SEM = 5.3). These results suggest that compound 14 can readily penetrate healthy human skin and achieve pharmacologically relevant exposures at the target site of action in the dermis.

Figure 4.

In vitro permeation of topically applied compound 14 across human abdominal skin (5 donors, 10 replicates each; n = 50). Formulation: 2.75% (w/w) 14 in 30% (w/w) ethanol, 30% (w/w) PEG400, 20% (w/w) diethylene glycol monoethyl ether, 20% (w/w) glycerin. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. (a) Mean cumulative amount of 14 (ng/cm2) delivered to the receptor solution over a period of 24 h postapplication. (b) Mean concentration of 14 (μg/g) delivered to the epidermis and dermis 24 h postapplication.

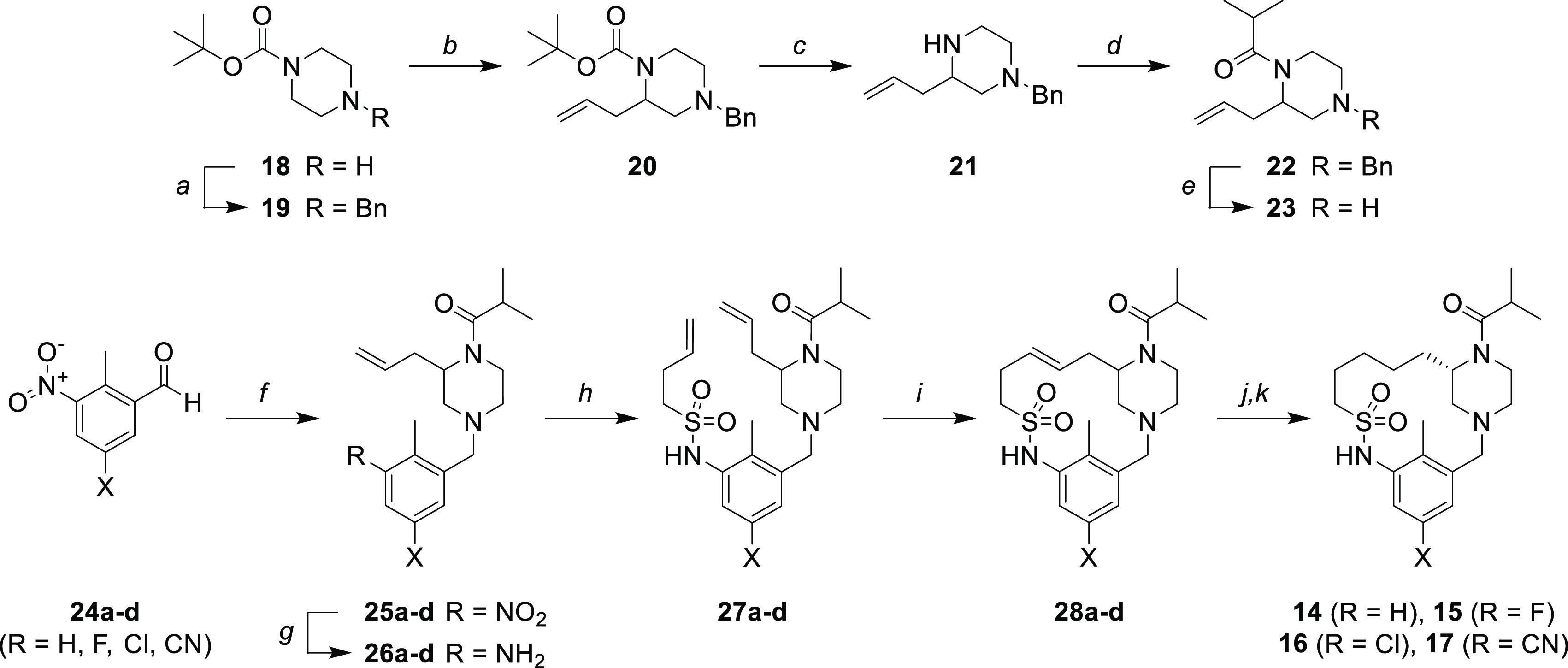

Macrocycles 14–17 were prepared as described in Scheme 1. The piperazine intermediate 20 was prepared as described by van Maarseveen24 in 43% yield. Subsequently, removal of the Boc protecting group followed by acylation with isobutyryl chloride provided compound 22. The benzyl group was then removed under conditions sparing the olefin.25 The resulting piperazine 23 was reacted with substituted nitro-aldehydes 24a–d to provide the corresponding tertiary amine products (25a–d) in good yields (54–61%). The nitro-group was cleanly reduced with Fe/NH4Cl to avoid olefin reduction and provide the anilines 26a–d, which were then sulfonylated with 3-butene-1-sulfonyl chloride to furnish the bis-olefin sulfonamides 27a–d. The ring closing metathesis reaction was achieved by using Grubbs Second Generation Catalyst26,27 under dilute conditions to give macrocyclic olefins 28a–d in various yields (21–61%). The olefin was then reduced by hydrogenation with PtO2 and hydrogen gas. The racemic product mixtures were separated by chiral chromatography to provide the desired S-enantiomers (14–17) and the R-enantiomers (see the Supporting Information). The other macrocycles described in this Letter (8–13) were prepared in a similar manner, with some modifications (see the Supporting Information).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Macrocycles 14–17.

Reagents and conditions: (a) BnBr, K2CO3, DMF, 67%. (b) sec-BuLi, TMEDA, THF, CuCN, LiCl, allyl bromide, 43%. (c) 4 M HCl in dioxane, 96%. (d) Isobutyryl chloride, TEA, DCM, 97%. (e) 1-Chloroethyl carbonochloridate, DCE, MeOH, 25%. (f) 23, DCM, Na2SO4, NaBH(OAc)3, 54–61%. (g) Fe, H2O/MeOH (1:2), NH4Cl, 82–100%. (h) 3-Butene-1-sulfonyl chloride, THF, pyridine, 13–77%. (i) Grubbs Second Generation Catalyst, DCM, 21–61%. (j) PtO2, H2, 28–93%. (k) Chiral separation (SFC or HPLC).

As described above, the unanticipated U-shaped bound conformation of 7a observed in the cocrystal structure with the RORC2 LBD has led to the successful design of macrocycles connecting the sulfonamide and piperazine methyl substituents. Indeed, macrocycle 9 maintained potent inhibition of IL-17 production, and its corresponding cocrystal structure confirmed an identical binding mode to the acyclic progenitor with the macrocyclic linker filling the hydrophobic pocket. Macrocyclization was found not to alter the desirable high in vitro human liver microsomal clearance of the series even though lipophilicity was reduced presumably due the presence of multiple metabolically labile sites. The high in vitro clearance was viewed favorably to limit systemic exposure following topical administration. Passive permeability as measured using the RRCK (MDCKII-LE) cell monolayer was found to be significantly increased for the macrocycles. Shielding of hydrogen bond donors would not be expected to be altered by macrocyclization in this specific example. Macrocyclization did remove one aromatic ring from the molecule, and this was considered a potential factor in the permeability change. However, an examination of matched molecular pairs from the Pfizer informatics database where a phenyl ring was replaced by a linear alkyl having one to four carbons (N = 1285) indicated that in most cases permeability remained the same (62%) while the remainder was nearly equally divided by increased (20%) and decreased (18%) results. A similar effect was seen specifically for sulfonamides though with a more limited data set (N = 35) in that 69% remained the same and only 11% resulted in an increase. Another significant difference for the macrocycles is a more spherical shape as noted by a smaller calculated mean radius of gyration (14, RoG = 3.50 Å; compared to 6, RoG = 5.35 Å). Important for optimization of the series for topical delivery, macrocyclization allowed for the identification of compound 14 with comparable potency to the acyclic literature example 6 but with a reduced molecular weight (ΔMW = −55 Da) and lower lipophility (ΔLogD = −1.1). As a result, macrocycle 14 has shown favorable in vitro properties suitable for topical delivery with low anticipated systemic exposure and provides a potential opportunity to treat IL-17 mediated inflammatory disease in the skin.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Chunru Cao, Jiaxin Chen, Liping Gao, Linhui Meng, Dan Shi, Sumei Wei, and Yu Zhang for compound synthesis. We are also grateful to the members of the Pfizer computational ADME group for development of the matched molecular pair database used in our analysis.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ADME

absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion

- HLMs

human liver microsomes

- LBD

ligand binding domain

- ROR

retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor

- TR-FRET

time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.2c00500.

Preparation and characterization data for compounds 7–17, assay descriptions, broad NHR screening for compound 14, and protein crystallography methods (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ivanov I. I.; McKenzie B. S.; Zhou L.; Tadokoro C. E.; Lepelley A.; Lafaille J. J.; Cua D. J.; Littman D. R. The orphan nuclear receptor RORγt directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell 2006, 126, 1121–1133. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhoen M. Interleukin 17 is a chief orchestrator of immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 612–621. 10.1038/ni.3742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley R. G.; Elewski B. E.; Lebwohl M.; Reich K.; Griffiths C. E. M.; Papp K.; Puig L.; Nakagawa H.; Spelman L.; Sigurgeirsson B.; Rivas E.; Tsai T.-F.; Wasel N.; Tyring S.; Salko T.; Hampele I.; Notter M.; Karpov A.; Helou S.; Papavassilis C. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis – Results of two phase 3 trials. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 326–338. 10.1056/NEJMoa1314258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths C. E. M.; Reich K.; Lebwohl M.; van de Kerkhof P.; Paul C.; Menter A.; Cameron G. S.; Erickson J.; Zhang L.; Secrest R. J.; Ball S.; Braun D. K.; Osuntokun O. O.; Heffernan M. P.; Nickoloff B. J.; Papp K. Comparison of ixekizumab with etanercept or placebo in moderate-to-severe psoriasis (UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3): results from two phase 3 randomised trials. Lancet 2015, 386, 541–551. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebwohl M.; Strober B.; Menter A.; Gordon K.; Weglowska J.; Puig L.; Papp K.; Spelman L.; Toth D.; Kerdel F.; Armstrong A. W.; Stingl G.; Kimball A. B.; Bachelez H.; Wu J. J.; Crowley J.; Langley R. G.; Blicharski T.; Paul C.; Lacour J.-P.; Tyring S.; Kircik L.; Chimenti S.; Duffin K. C.; Bagel J.; Koo J.; Aras G.; Li J.; Song W.; Milmont C. E.; Shi Y.; Erondu N.; Klekotka P.; Kotzin B.; Nirula A. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab in psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1318–1328. 10.1056/NEJMoa1503824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInnes I. B.; Mease P. J.; Kirkham B.; Kavanaugh A.; Ritchlin C. T.; Rahman P.; van der Heijde D.; Landewé R.; Conaghan P. G.; Gottlieb A. B.; Richards H.; Pricop L.; Ligozio G.; Patekar M.; Mpofu S. Secukinumab, a human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriatic arthritis (FUTURE 2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2015, 386, 1137–1146. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeten D.; Sieper J.; Braun J.; Baraliakos X.; Dougados M.; Emery P.; Deodhar A.; Porter B.; Martin R.; Andersson M.; Mpofu S.; Richards H. B. Secukinumab, an interleukin-17A inhibitor, in ankylosing spondylitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2534–2548. 10.1056/NEJMoa1505066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnute M. E.; Wennerstål M.; Alley J.; Bengtsson M.; Blinn J. R.; Bolten C. W.; Braden T.; Bonn T.; Carlsson B.; Caspers N.; Chen M.; Choi C.; Collis L. P.; Crouse K.; Färnegårdh M.; Fennell K. F.; Fish S.; Flick A. C.; Goos-Nilsson A.; Gullberg H.; Harris P. K.; Heasley S. E.; Hegen M.; Hromockyj A. E.; Hu X.; Husman B.; Janosik T.; Jones P.; Kaila N.; Kallin E.; Kauppi B.; Kiefer J. R.; Knafels J.; Koehler K.; Kruger L.; Kurumbail R. G.; Kyne R. E.; Li W.; Löfstedt J.; Long S. A.; Menard C. A.; Mente S.; Messing D.; Meyers M. J.; Napierata L.; Nöteberg D.; Nuhant P.; Pelc M. J.; Prinsen M. J.; Rhönnstad P.; Backström-Rydin E.; Sandberg J.; Sandström M.; Shah F.; Sjöberg M.; Sundell A.; Taylor A. P.; Thorarensen A.; Trujillo J. I.; Trzupek J. D.; Unwalla R.; Vajdos F. F.; Weinberg R. A.; Wood D. C.; Xing L.; Zamaratski E.; Zapf C. W.; Zhao Y.; Wilhelmsson A.; Berstein G. Discovery of 3-Cyano-N-(3-(1-isobutyrylpiperidin-4-yl)-1-methyl-4-(trifluoromethyl)-1H-pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridin-5-yl) benzamide: A Potent, Selective, and Orally Bioavailable Retinoic Acid Receptor-Related Orphan Receptor C2 Inverse Agonist. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 10415–10439. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.; Xiao H.-Y.; Batt D. G.; Xiao Z.; Zhu Y.; Yang M. G.; Li N.; Yip S.; Li P.; Sun D.; Wu D.-R.; Ruzanov M.; Sack J. S.; Weigelt C. A.; Wang J.; Li S.; Shuster D. J.; Xie J. H.; Song Y.; Sherry T.; Obermeier M. T.; Fura A.; Stefanski K.; Cornelius G.; Chacko S.; Khandelwal P.; Dudhgaonkar S.; Rudra A.; Nagar J.; Murali V.; Govindarajan A.; Denton R.; Zhao Q.; Meanwell N. A.; Borzilleri R.; Dhar T. G. M. Azatricyclic inverse agonists of RORγt that demonstrate efficacy in models of rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 827–835. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.1c00112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igaki K.; Nakamura Y.; Tanaka M.; Mizuno S.; Yoshimatsu Y.; Komoike Y.; Uga K.; Shibata A.; Imaichi H.; Takayuki S.; Ishimura Y.; Yamasaki M.; Takanori Kanai T.; Tsukimi Y.; Tsuchimori N. Pharmacological effects of TAK-828F: an orally available RORγt inverse agonist, in mouse colitis model and human blood cells of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Res. 2019, 68, 493–509. 10.1007/s00011-019-01234-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y.; Igaki K.; Uga K.; Shibata A.; Yamauchi H.; Yamasaki M.; Tsuchimori N. Pharmacological evaluation of TAK-828F, a novel orally available RORγt inverse agonist, on murine chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis model. J. Neuroimmunol. 2019, 335, 577016. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2019.577016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer S.; Bryson C.; McGeehan G.; Lala D.; Krueger J.; Gregg R. First evidence of efficacy of an orally active RORγt inhibitor in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Exp. Dermatol. 2016, 25 (Suppl. 4), 3–51. 10.1111/exd.13200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asimus S.; Palmér R.; Albayaty M.; Forsman H.; Lundin C.; Olsson M.; Pehrson R.; Mo J.; Russell M.; Carlert S.; Close D.; Keeling D. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and safety of the inverse retinoic acid-related orphan receptor γ agonist AZD0284. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 86, 1398–1405. 10.1111/bcp.14253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue X.; De Leon-Tabaldo A.; Luna-Roman R.; Castro G.; Albers M.; Schoetens F.; DePrimo S.; Devineni D.; Wilde T.; Goldberg S.; Hoffmann T.; Fourie A. M.; Thurmond R. L. Preclinical and clinical characterization of the RORγt inhibitor JNJ-61803534. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11066. 10.1038/s41598-021-90497-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang E.; Wu S.; Gupta A.; von Mackensen Y.-L.; Siemetzki H.; Freudenberg J.; Wigger-Alberti W.; Yamaguchi Y. (2018), A phase I randomized controlled trial to evaluate safety and clinical effect of topically applied GSK2981278 ointment in a psoriasis plaque test. Br. J. Dermatol. 2018, 178, 1427–1429. 10.1111/bjd.16131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berstein G.; Zhang Y.; Berger Z.; Kieras E.; Li G.; Samuel A.; Yeoh T.; Dowty H.; Beaumont K.; Wigger-Alberti W.; von Mackensen Y.; Kroencke U.; Hamscho R.; Garcet S.; Krueger J. G.; Banfield C.; Oemar B. A phase I, randomized, double-blind study to assess the safety, tolerability and efficacy of the topical RORC2 inverse agonist PF-06763809 in participants with mild-to-moderate plaque psoriasis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 46, 122–129. 10.1111/ced.14412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gege C. Retinoic acid-related orphan receptor gamma t (RORγt) inverse agonists/antagonists for the treatment of inflammatory diseases – where are we presently?. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2021, 16, 1517–1535. 10.1080/17460441.2021.1948833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts R. O.; Guy R. H. Predicting skin permeability. Pharm. Res. 1992, 9, 663–669. 10.1023/A:1015810312465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano T.; Nakagawa A.; Tsuji M.; Noda K. Skin permeability of various non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in man. Life Sci. 1986, 39, 1043–1050. 10.1016/0024-3205(86)90195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han F.; Lei H.; Lin X.; Meng Q.; Wang Y.. Modulators of the retinoid-related orphan receptor gamma (ROR-gamma) for use in the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. WO 2014/086894, 2014.

- Nakajima R.; Oono H.; Sugiyama S.; Matsueda Y.; Ida T.; Kakuda S.; Hirata J.; Baba A.; Makino A.; Matsuyama R.; White R. D.; Wurz R. P.; Shin Y.; Min X.; Guzman-Perez A.; Wang Z.; Symons A.; Singh S. K.; Mothe S. R.; Belyakov S.; Chakrabarti A.; Shuto S. Discovery of [1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyridine derivatives as potent and orally bioavailable RORγt inverse agonists. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 528–534. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheepstra M.; Leysen S.; van Almen G. C.; Miller J. R.; Piesvaux J.; Kutilek V.; van Eenennaam H.; Zhang H.; Barr K.; Nagpal S.; Soisson S. M.; Kornienko M.; Wiley K.; Elsen N.; Sharma S.; Correll C. C.; Trotter B. W.; van der Stelt M.; Oubrie A.; Ottmann C.; Parthasarathy G.; Brunsveld L. Identification of an allosteric binding site for RORγt inhibition. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8833. 10.1038/ncomms9833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez M. L.; Kaila N.; Strohbach J. W.; Trzupek J. D.; Brown M. F.; Flanagan M. E.; Mitton-Fry M. J.; Johnson T. A.; TenBrink R. E.; Arnold E. P.; Basak A.; Heasley S. E.; Kwon S.; Langille J.; Parikh M. D.; Griffin S. H.; Casavant J. M.; Duclos B. A.; Fenwick A. E.; Harris T. M.; Han S.; Caspers N.; Dowty M. E.; Yang X.; Banker M. E.; Hegen M.; Symanowicz P. T.; Li L.; Wang L.; Lin T. H.; Jussif J.; Clark J. D.; Telliez J.-B.; Robinson R. R.; Unwalla R. Identification of N-{cis-3-[Methyl(7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-yl) amino]cyclobutyl}propane-1-sulfonamide (PF-04965842): A selective JAK1 clinical candidate for the treatment of autoimmune diseases. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 1130–1152. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkheij M.; van der Sluis L.; Sewing C.; den Boer D. J.; Terpstra J. W.; Hiemstra H.; Bakker W. I. I.; van den Hoogenband A.; van Maarseveen J. H. Synthesis of 2-substituted piperazines via direct α-lithiation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 2369–2371. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2005.02.085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B. V.; O'Rourke D.; Li J. Mild and selective debenzylation of tertiary amines using α-chloroethyl chloroformate. Synlett 1993, 1993, 195–196. 10.1055/s-1993-22398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vougioukalakis G. C.; Grubbs R. H. Ruthenium-based heterocyclic carbene-coordinated olefin metathesis catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 1746–1787. 10.1021/cr9002424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou K. C.; Bulger P. G.; Sarlah D. Metathesis reactions in total synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 4490–4527. 10.1002/anie.200500369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.