Abstract

Background

We aimed to determine if patient symptoms and computed tomography enterography (CTE) and magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) imaging findings can be used to predict near-term risk of surgery in patients with small bowel Crohn’s disease (CD).

Methods

CD patients with small bowel strictures undergoing serial CTE or MRE were retrospectively identified. Strictures were defined by luminal narrowing, bowel wall thickening, and unequivocal proximal small bowel dilation. Harvey-Bradshaw index (HBI) was recorded. Stricture observations and measurements were performed on baseline CTE or MRE and compared to with prior and subsequent scans. Patients were divided into those who underwent surgery within 2 years and those who did not. LASSO (least absolute shrinkage and selection operator) regression models were trained and validated using 5-fold cross-validation.

Results

Eighty-five patients (43.7 ± 15.3 years of age at baseline scan, majority male [57.6%]) had 137 small bowel strictures. Surgery was performed in 26 patients within 2 years from baseline CTE or MRE. In univariate analysis of patients with prior exams, development of stricture on the baseline exam was associated with near-term surgery (P = .006). A mathematical model using baseline features predicting surgery within 2 years included an HBI of 5 to 7 (odds ratio [OR], 1.7 × 105; P = .057), an HBI of 8 to 16 (OR, 3.1 × 105; P = .054), anastomotic stricture (OR, 0.002; P = .091), bowel wall thickness (OR, 4.7; P = .064), penetrating behavior (OR, 3.1 × 103; P = .096), and newly developed stricture (OR: 7.2 × 107; P = .062). This model demonstrated sensitivity of 67% and specificity of 73% (area under the curve, 0.62).

Conclusions

CTE or MRE imaging findings in combination with HBI can potentially predict which patients will require surgery within 2 years.

Keywords: Crohn disease, computed tomography enterography, magnetic resonance enterography, surgical intervention, predictive model

Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) is an inflammatory bowel disease characterized by chronic transmural inflammation and a relapsing and remitting clinical course.1 Symptoms may not necessarily correlate with biological activity or disease burden, so ileocolonoscopy is used for monitoring disease activity.2 Patients with small bowel CD often develop bowel obstruction and penetrating complications such as abscess and fistula, with approximately 50% of patients with CD requiring surgery within 10 years after initial diagnosis and one-third of CD patients requiring multiple surgeries.3,4 The goal of medical management is relief of symptoms in addition to mucosal healing based on ileocolonoscopy or transmural healing based on cross-sectional imaging to avoid surgery and loss of intestinal function.

Colonoscopy provides excellent visualization of the colon and the ability to biopsy and screen for neoplasia; however, interrogation of the terminal ileum can be compromised by stenosis of the ileocecal valve or terminal ileum, angulation, and visualization of the mucosa only, potentially resulting in underestimating the extent and transmural severity of small bowel CD.5,6 Conversely, computed tomography enterography (CTE) and magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) are cross-sectional imaging modalities optimized to display the small bowel wall with lower accuracy in the colon. They are complementary to colonoscopy and are able to display moderate and severely active inflammation in the small bowel,7-9 estimate the severity of inflammation,10,11 and detect penetrating and obstructing complications.8 They have been recommended for use in periodic surveillance of small bowel CD to guide therapy,12-14 with response by CTE or MRE indicating a decreased future risk of surgery.9,15

A predictive model that would incorporate CTE or MRE imaging findings and patient symptoms to predict near-term risk of surgery (eg, within 2 years) may assist gastroenterologists, colorectal surgeons, and patients in decision making regarding the likelihood of response to medical therapy vs moving quickly to surgery, especially for patients with CD complicated with definite strictures and probable strictures.5,16 Therefore, the purpose of this study is to determine if such a model combining stricture morphology from CTE or MRE in combination with patient symptoms and disease behavior can be used to predict near-term risk of surgery (ie, within 2 years of imaging) in patients with small bowel CD.

Methods

Patient Screening

For this study, we utilized a previously examined cohort of 150 consecutive adult patients ≥18 years of age with confirmed small bowel CD who underwent serial imaging with CTE and/or MRE at our institution from January 1, 2002, and October 31, 2014, to investigate the significance of radiological response as a treatment target.9,15 This cohort included patients who had a baseline CTE or MRE prior to initiation of medical therapy with a follow-up CTE or MRE on therapy, separated by a minimum of 6 months with at least 1 year of clinical follow-up after the baseline CTE or MRE. Alternatively, patients may have had 2 CTEs or MREs more than 6 months apart while on maintenance therapy with at least 1 year of clinical follow-up, with the earlier CTE or MRE defined as the baseline exam. Because patients undergo CTE or MRE examination before starting or changing medication and on maintenance therapy to assess achievement of treatment goal in our clinical practice, we utilized these 2 approaches to enroll patients. Patients were included if they had unequivocal radiologic evidence of a small bowel CD–associated definite stricture or probable stricture on baseline CTE or MRE examination in this study. Definite strictures were defined as small bowel segments demonstrating unequivocal luminal narrowing to <50% of a normal small bowel loop, bowel wall thickening of at least 25% compared with the normal bowel wall, and proximal small bowel dilation of >3 cm on CTE or MRE.17 Probable strictures were defined similarly, except that no specific threshold was set for proximal small bowel dilation.14,18 Patients were excluded if no stricture was present (eg, active inflammatory small bowel CD with or without luminal narrowing) or if they were <18 years of age.

Chart review documented demographic features, date of surgeries (if any), obstructive symptoms (ie, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, distention, and bloating), Harvey-Bradshaw index (HBI) and medication at the baseline CTE or MRE. The imaging measurements and observations and statistical analysis reported herein were performed for the current study. Patients were classified based on clinical and imaging findings at the time of exam according to the Montreal classification of disease behavior.19

Image Acquisition

CTE and MRE examinations were performed according to the recommended standard technique.12,13,20 Patients orally ingested 1350 mL of low contrast barium solution (Volumen; Bracco Diagnostics, Princeton, NJ, USA) over 30 to 60 minutes with additional ingestion of 500 mL of water at 15 minutes before CTE and MRE examinations.

CTE image acquisition was obtained in the enteric phase of enhancement at 50 seconds after intravenous administration of iodinated contrast media (Omnipaque 350; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA). Multiplanar images were reconstructed with a high spatial resolution (slice thickness ≤3 mm) in axial, coronal, and sagittal planes.

MRE was performed using a 1.5-T MR imaging system employing an 8-channel phased-array coil to image the abdomen and pelvis. All MRE exams were performed using gadolinium and a spasmolytic agent (glucagon). Axial and coronal single-shot fast spin-echo T2-weighted image or fast imaging employing steady-state acquisition or true fast imaging with steady-state precession images were obtained, in addition to coronal images obtained during dynamic gadolinium enhancement (with 3-dimensional volume acceleration [LAVA or VIBE] sequences obtained at 45 seconds after the beginning of gadolinium administration, with 2 subsequent contrast-enhanced phases), in addition to postgadolinium axial LAVA or VIBE images.

Image Evaluation

Three fellowship-trained gastrointestinal radiologists (S.P.S., J.P.H., and J.G.F. with 15, 23, and 23 years interpreting CTE or MRE, respectively) blinded to patient history evaluated approximately one-third of the CTE or MRE images as described subsequently. Every small bowel segment that met stricture criteria on the baseline exam was analyzed, so more than 1 definite stricture or probable stricture could be assessed per patient. After this review was complete, all available cross-sectional imaging was reviewed to determine if each stricture was present on prior and subsequent imaging.

Imaging observations included determining type of stricture (naive vs anastomotic); single or multiple areas of luminal narrowing within the stricture; presence of marked small bowel dilation greater than 4 cm; imaging findings of active inflammation involving the stricture (eg, mural hyperenhancement, wall thickening, and ulceration); degree of mural enhancement (none, equivocal, mild, moderate, and severe); comb sign (absent, equivocal, mild, moderate, and severe); perienteric findings such as mesenteric edema; penetrating complications such as inflammatory mass, fistula, or abscess; perianal disease; and chronic mesenteric venous occlusion.

Imaging measurements of the small bowel segments with strictures were performed using a software program configured to record measurements for small bowel inflammation at CTE or MRE at our institution.21,22 Each reader measured the length of the inflamed or abnormal small bowel segment, the length of the small bowel definite strictures or probable strictures, luminal diameter (narrowest point within the stricture), maximum bowel wall thickness (at the site of greatest luminal narrowing), and maximum diameter of proximal small bowel dilation (in any plane) (Figure 1). Strictures were considered to start and end based on where luminal narrowing starts and stops, so this length could be shorter than the length of a longer inflamed segment. The ratio of the diameter of proximal small bowel dilation to minimum luminal diameter within the stricture (ie, the Dillman ratio) was also recorded.23 If a patient had multiple nearby small bowel segments with luminal narrowing (ie, a few centimeters apart without intervening proximal small bowel dilation), the entire small bowel segment that contained the nearby narrowed segments was included for the length measurement, along with the single value for minimum luminal diameter and maximum proximal small bowel dilation, and the single Dillman ratio was calculated.

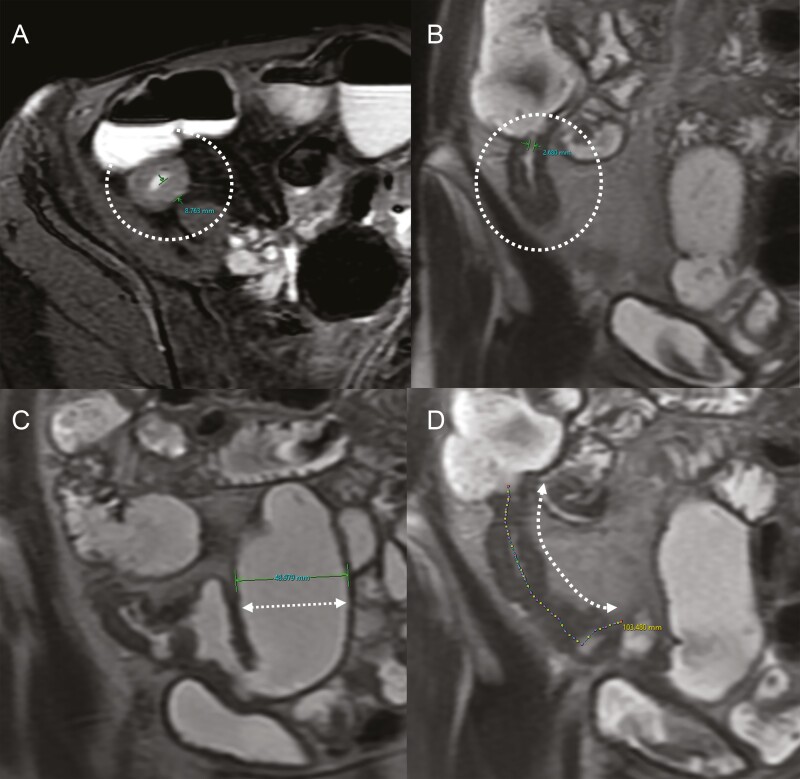

Figure 1.

An example of imaging measurements. A-D, Each reader measured the maximum bowel wall thickness (A: circle), narrowest luminal diameter (B: circle), diameter of the proximal small bowel greatest dilation (C: broken arrow), and stricture length (D: broken arrow).

Based on their morphologic appearance, 2 gastrointestinal radiologists (A.I. and J.G.F. with 7 and 23 years interpreting CTE or MRE, respectively) subsequently classified each stricture into 4 different morphologic groups: (1) stricture with imaging findings of inflammation, (2) stricture without imaging findings of inflammation, (3) multifocal strictures (ie, multiple nearby strictures separated by ≤3 cm),17 or (4) stricture with inflammation associated with branching, complex enteric fistulas (not including sinus tract and abscess; with or without proximal small bowel dilation) (Figure 2). A stricture with overlapping features could be placed into 2 different categories, and then a dominant morphologic category was determined. This classification was performed in consensus between the radiologists, as there was no reference standard.

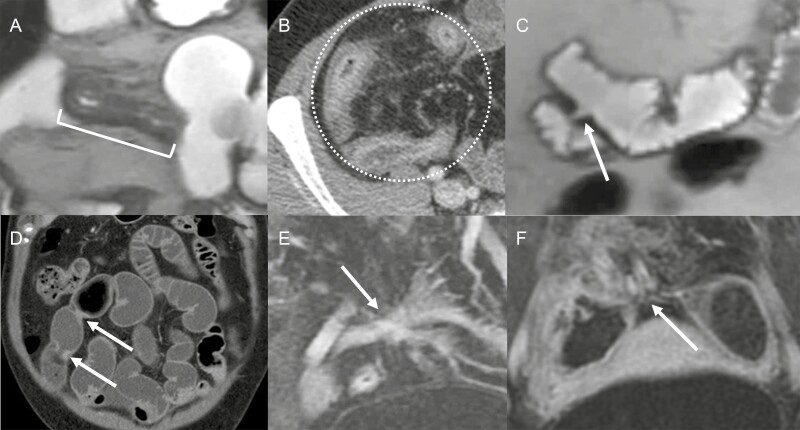

Figure 2.

Stricture morphology. A, Stricture with a short segment inflammation <10 cm (with proximal and distal ends marked by the bracket). B, Stricture with a long segment inflammation more than 10 cm (circle). C, Single stricture without inflammation (arrow). D, Multifocal short segment strictures (arrows). E, Complex fistula (arrow) with inflammation without upstream dilation. F, Complex fistula (arrow) with inflammation and upstream dilation.

Small bowel strictures were also categorized based on prior and subsequent CTE or MRE exams available at our institution. A patient with a small bowel stricture on a baseline CTE or MRE that was not present on prior CTE or MRE was categorized as having a newly developed stricture at baseline (ie, it could not be newly developed if the baseline CTE or MRE was the first imaging exam in our institutional imaging archive). A definite or probable small bowel stricture on baseline CTE or MRE, which was not associated with unequivocal proximal small bowel dilation on subsequent CTE or MRE, was categorized as having resolved.

Statistical Analysis

We sought to develop mathematical models of imaging measurements and observations in combination with HBI that could predict the risk of surgery within 2 years after a CTE or MRE demonstrating a definite stricture or probable stricture in patients with CD. A 2-year time window was chosen prior to the start of the study, as it was felt to be a short enough period of time that may affect provider and patient decision making relating to whether to proceed to surgery more rapidly. Additionally, as our dataset was small, we did not have enough observations to derive meaningful results from a time-to-event analysis. An outcome of surgical treatment of small bowel strictures identified within 2 years of the baseline CTE or MRE was the primary endpoint examined in our study. Small bowel stricture morphologic groups, measurements, and observations were compared with the primary endpoint (surgical resection vs observation), along with time from the baseline CTE or MRE and subsequent surgery, to identify variables that would predict the risk of subsequent surgery.

For patients with multiple small bowel strictures, the stricture with maximum proximal small bowel diameter was regarded as the dominant stricture, with the observations and measurements from the dominant stricture used in model development.

Several variables were categorized for analysis and predictive model creation. HBI values were categorized as 0 to 4, 5 to 7, and 8 to 16. Comb sign and mural enhancement were categorized as none to mild vs moderate to severe. Morphologic stricture groups were collapsed into strictures with imaging findings of inflammation, strictures without inflammation or multifocal strictures, and strictures with inflammation associated with complex enteric fistula.

For univariate analysis, a per-patient approach was used. The evaluated clinical and imaging findings and imaging measurements were compared using chi-square test for categorical variables (eg, gender). For continuous-value variables (eg, age), a t test was used to compare patients with and without subsequent surgery at the 5% significance level.

For multivariate analysis, we developed a logistic regression model and we used the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression for variable selection. LASSO shrinks the coefficient of nonimportant variables to zero by penalizing the number of variables in the regression model.24 LASSO is a regularization method which is widely used in literature.25,26 To create a multivariable model, we included variables associated with surgery within 2 years with a P value of .10 or less. We randomly split the dataset into train (75%) and validation (25%) datasets and used 5-fold cross-validation to validate the model. The binary response variable of the logistic regression model indicates whether a patient underwent surgery within 2 years of the baseline CTE or MRE. The model calculates the probability of a surgery for each patient, using a cutoff value of 0.5 to predict the response variable. We also calculated the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Receiver-operating characteristic analysis was conducted for the training and validation datasets to evaluate the performance of our predictive algorithm.

Ethical Considerations

Our institutional review board approved this retrospective study (IRB#: 18-011580), which utilized existing medical records and images, with the requirement for informed written consent being waived.

Results

A total of 85 patients (average age at baseline scan: 43.7 ± 15.3 years; majority male [57.6%]) with 137 small bowel strictures, including 67 definite strictures that met Society of Abdominal Radiology/American Gastroenterological Association/CONSTRICT (CrOhN’S disease anti-fibrotic STRICTure Therapies) criteria with proximal small bowel dilation ≥3 cm and 70 probable strictures with unequivocal proximal small bowel dilation <3 cm,14,17,18 were enrolled. Of 85 patients, 60 patients had 1 stricture, 9 patients had 2 strictures, and 16 patients had 3 or more strictures. Obstructive symptoms were documented in approximately 60% of patients, and there was no significant difference in the frequency of obstructive symptoms between the 2 groups (P = .96). Most patients underwent CTE (n = 71) rather than MRE (n = 14) for the baseline enterography exam. Follow-up exams were available in all cases (median 4 [interquartile range (IQR), 2-5] CTEs or MREs), and prior exams were available in 23 patients (median 2 [IQR, 1-3] CTEs or MREs). At the baseline CTE or MRE, 42 patients had no medication, 22 patients were treated with tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitor, and 22 patients were treated with other medications (P = .10). Fifty-three (62%) patients eventually required surgical intervention because of their small bowel stricture, with a mean duration between baseline CTE or MRE and surgery of 2.6 ± 2.3 years. Approximately half of the patients that underwent surgery did so within 2 years (n = 26; including 18 patients with a single stricture and 8 patients with multiple strictures), and 59 patients did not undergo surgery within 2 years. Mean time of clinical follow-up was 6.9 ± 2.5 (range, 2.0-12.1) years in patients without surgical intervention within 2 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Age at baseline scan, y | 43.7 ± 15.3 |

|---|---|

| Female | 36 (42.4) |

| Obstructive symptom | 51 (60.0) |

| Strictures | |

| Definite stricture | 67 (48.9) |

| Probable stricture | 70 (51.1) |

| Number of involved segments | |

| 1 stricture | 60 (70.6) |

| 2 strictures | 9 (10.5) |

| 3 or more strictures | 16 (18.8) |

| Baseline scan | |

| CTE | 71 (83.5) |

| MRE | 14 (16.5) |

| Patients with prior scan | 23 (27.1) |

| Prior scans | 2 (1-3) |

| Patients with follow-up scan | 85 (100) |

| Prior scans | 4 (2-5) |

| Medication at index CTE/MRE | |

| No medication | 42 (49.4) |

| TNF-α inhibitor with/without immunomodulator | 22 (25.9) |

| Other treatment | 22 (25.9) |

| Surgery date from baseline scan, y | 2.6 ± 2.3 |

| Timing of surgery from baseline scan | 53 (62.4 %) |

| <1 y | 16 (18.8 %) |

| 1-2 y | 10 (11.8 %) |

| 2-3 y | 9 (10.6 %) |

| 3-5 y | 10 (11.8 %) |

| >5 y | 8 (9.4 %) |

Values are mean ± SD, n (%), or median (interquartile range).

Abbreviations: CTE, computed tomography enterography; MRE, magnetic resonance enterography; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

HBI was not available in 4 cases because of lack of clinical information, but about one-third (32% [n = 26 of 81]) of patients had an HBI of 0 to 4. Approximately one-third of patients had an HBI of 5 to 7 (36% [n = 29 of 81]), while another one-third had an HBI of 8 to 16 (32% [n = 26 of 81]). There was no significant difference in HBI (P = .58) between patients with and without surgical intervention within 2 years (Table 2). Additionally, there was no significant difference between 2 groups in disease behavior (P = .44) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis for patient factors, stricture morphology, imaging observations and measurements, and temporal changes in stricture appearance compared with near-term risk of surgery

| No Surgery Within 2 y (n = 59) | Surgery Within 2 y (n = 26) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease severity | |||

| HBI of 0-4 | 20 (33.9) | 6 (23.1) | .58 |

| HBI of 5-7 | 19 (32.2) | 10 (38.5) | |

| HBI of 8-16 | 17 (28.8) | 9 (34.6) | |

| Behavior | |||

| Neither stricturing nor penetrating | 23 (39.0) | 10 (38.5) | .44 |

| Stricturing | 18 (30.5) | 7 (26.9) | |

| Penetrating | 5 (8.5) | 5 (19.2) | |

| Stricturing and penetrating | 3 (5.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Neither stricturing nor penetrating with perianal fistula | 5 (8.5) | 1 (3.8) | |

| Stricturing with perianal fistula | 1 (1.7) | 2 (7.7) | |

| Penetrating with perianal fistula | 4 (6.8) | 1 (3.8) | |

| Stricture morphology | |||

| Stricture with inflammation | 38 (64.4) | 19 (73.1) | .72 |

| Stricture without inflammation or multifocal stricture | 5 (8.5) | 2 (7.7) | |

| Stricture with complex enteric fistula | 16 (27.1) | 5 (19.2) | |

| Imaging observation | |||

| Active inflammation | 56 (94.9) | 26 (100) | .59 |

| Anastomotic stricture | 19 (32.2) | 6 (23.1) | .55 |

| Multiple strictures in the same segment | 28 (47.5) | 13 (50.0) | 1.00 |

| Proximal small bowel dilation >4 cm | 11 (18.6) | 5 (19.2) | 1.00 |

| Marked segmental enhancement | 9 (15.3) | 9 (34.6) | .08 |

| Comb sign | 14 (23.7) | 7 (26.9) | .97 |

| Perienteric findings | 27 (45.8) | 10 (38.5) | .70 |

| Mesenteric thrombosis | 9 (15.3) | 3 (11.5) | .75 |

| Penetrating disease | 14 (23.7) | 9 (34.6) | .44 |

| Perianal fistula | 4 (6.8) | 2 (7.7) | 1.00 |

| Imaging measurements | |||

| Number of strictures in the same segment | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | .98 |

| Length of involved (inflamed) segment, cm | 12.0 (5.8-25.0) | 10.5 (8.0-15.0) | .17 |

| Length of stricture, cm | 6.2 (3.3-11.2) | 4.9 (3.3-8.0) | .20 |

| Luminal diameter in the stricture, mm | 1.1 (0.9-2.6) | 1.5 (1.0-2.0) | .21 |

| Maximum bowel wall thickness, mm | 9.0 (6.0-10.0) | 9.0 (7.3-11.0) | .34 |

| Diameter of proximal small bowel, cm | 3.2 (2.6-4.0) | 3.0 (2.4-3.6) | .50 |

| Dillman ratio | 28.0 (10.1-46.1) | 20.7 (15.2-33.3) | .19 |

| Temporal change in stricture | |||

| Newly developed stricture | 9 (15.3) | 12 (46.2) | <.01a |

| Stricture resolution | 14 (23.7) | 5 (19.2) | .86 |

Values are n (%) or median (interquartile range).

Abbreviations: CTE, computed tomography enterography; HBI, Harvey-Bradshaw index; MRE, magnetic resonance enterography; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

P < .05.

Regarding stricture morphology, 72% (n = 99 of 137) were strictures with inflammation, 3% (n = 4 of 137) were strictures without inflammation, 4% (n = 5 of 137) were multifocal strictures, and 21% (n = 29 of 137) were strictures associated with complex enteric fistulas. There was no difference in the stricture morphology of the dominant stricture between patients that went to surgery within 2 years and those that did not (P = .72) (Table 2).

About one-quarter of strictures (24% [n = 33 of 137]) were adjacent to an ileocolonic or enteroenteric anastomosis. Twenty-one (27% [n = 23 of 85]) patients had penetrating complications associated with their small bowel stricture. Twelve (14% [n = 12 of 85]) patients had a chronic mesenteric venous thrombosis, and 6 (7.3% [n = 6 of 82]) had a perianal fistula. Three patients had incomplete imaging of their anus, so perianal disease could not be assessed. Sixteen (19% [n = 16 of 85]) patients had a dominant stricture with proximal small bowel dilation of 4 cm or greater. No significant difference was seen in any imaging observations between patients that went to surgery within 2 years and those that did not (Table 2).

Comparing the cohort of patients that avoided surgery vs those that underwent surgery within 2 years, the median length and IQR of definite or probable strictures was 6.2 (IQR, 3.3-11.2) cm vs 4.9 (IQR, 3.3-8.0) cm (P = .20), with the median minimal luminal diameter being 1.1 (IQR, 0.9-2.6) mm vs 1.5 (IQR, 1.0-2.0) mm (P = .21), the maximal bowel wall thickness being nearly identical (9.0 mm vs 9.0 mm; P = .34), the diameter of proximal small bowel dilation being 3.2 (IQR, 2.6-4.0) cm vs 3.0 (IQR, 2.4-3.6) cm (P = .50), and the length of the inflamed small bowel segment containing strictures being 12.0 (IQR, 5.8-25.0) cm vs 10.5 (IQR, 8.0-15.0) cm (P = .17). The median ratio of the proximal small bowel dilation to minimum luminal diameter within the strictures (Dillman ratio) was 28.0 (IQR, 10.1-46.1) vs 20.7 (IQR, 15.2-33.3) (P = .19).

Prior exams were available for review in 23 (27.1% [n = 23 of 85]) patients. Of patients with prior exams, almost all (91.3% [n = 21 of 23]) developed a small bowel stricture on the baseline CTE or MRE exam in this study. Follow-up exams were available for all 85 patients and 22% (n = 19 of 85) had resolution of unequivocal proximal dilation on subsequent CTE or MRE. In univariate analysis, only small bowel strictures that were newly developed on the baseline CTE or MRE were significantly correlated with near-term risk of surgery (P < .01). No other patient factors, imaging observations or measurements, or stricture morphologies were associated with near-term surgery within 2 years (Table 2).

A multivariable model was subsequently created that predicted near-term surgical intervention within 2 years in the training set (Table 3). This model included the following predictive parameters: HBI of 5 to 7 (OR, 1.7 × 105; P = .057), HBI of 8 to 16 (OR, 3.1 × 105; P = .054), anastomotic stricture (OR, 0.002; P = .091), bowel wall thickness (OR, 4.7; P = .064), penetrating disease behavior (OR, 3.1 × 103; P = .096), and newly developed stricture (OR, 7.2 × 107; P = .062) (Table 3 and Figure 3). Other variables that were not significant but which contained nonzero coefficients were also included in the model, as these values may subsequently be refined (Supplemental Table 1). These variables included the length of the abnormal segment containing the stricture, bowel wall thickness, stricture resolution, mesenteric vein thrombosis, perianal fistula, and MRE rather than CTE.

Table 3.

Predictors for near-term surgery risk within 2 years in multivariate analysis

| Predictor | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HBI of 5-7 | 1.7 × 105 | 0.7-3.9 × 1010 | .057 |

| HBI of 8-16 | 3.1 × 105 | 0.8-1.2 × 1011 | .054 |

| Anastomotic stricture | 0.002 | 0-2.7 | .091 |

| Bowel wall thickness | 4.7 | 0.9-25 | .064 |

| Penetrating disease | 3.1 × 103 | 0.2-3.8 × 107 | .096 |

| Newly developed stricture | 7.2 × 107 | 0.4-1.3 × 1016 | .062 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HBI, Harvey-Bradshaw index.

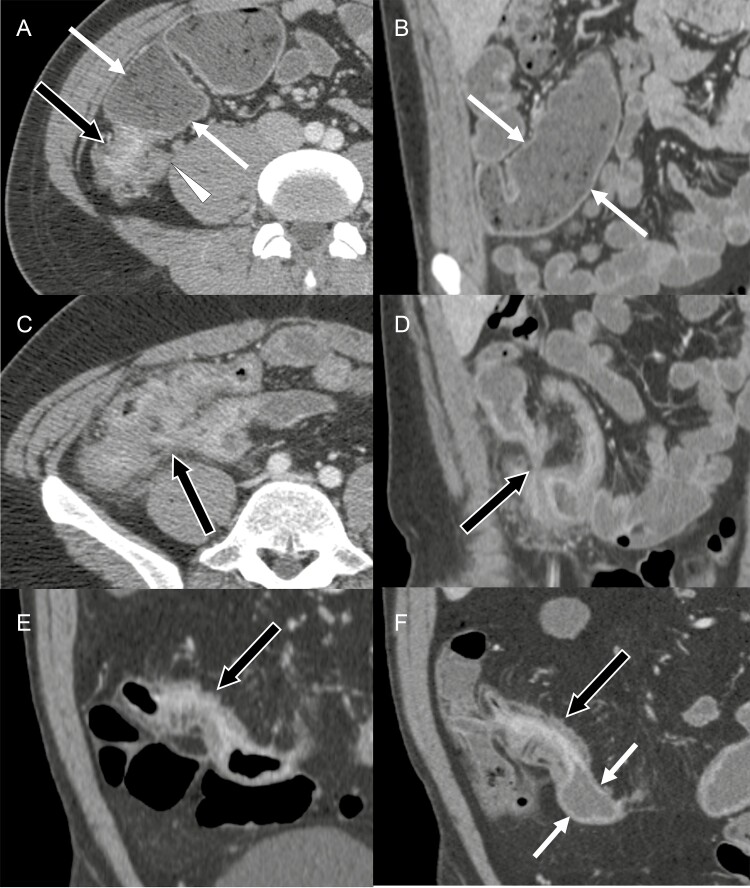

Figure 3.

Examples of imaging features that predict near-term surgery within 2 years in multivariate analysis. A and B, Predominantly inflammatory stricture: a 27-year-old male patient with ileal wall thickening with mural hyperenhancement (black arrow in A) associated with 54 mm of the proximal small bowel dilation (white arrows in A and B). The wall thickening is observed in the appendix (white arrowhead in A). This patient underwent ileal resection 282 days after the baseline computed tomography enterography (CTE). C and D, Penetrating disease: a 33-year-old male patient with inflamed small bowel segments tethered to each other and connected through a complex fistula (arrows). This patient underwent ileal resection 329 days after the baseline CTE. E and F, Newly developed stricture: a 38-year-old female patient with the terminal ileal bowel wall thickening and mural hyperenhancement, indicating active inflammatory Crohn’s disease on a CTE 64 months before baseline CTE (arrow in E). The same terminal ileal segment developed a stricture with 32 mm of proximal small bowel dilation on the baseline CTE (arrows in F). This patient underwent ileocolonic resection 105 days after the baseline CTE.

For prediction of near-term surgical intervention within 2 years, this model had an area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve of 0.98 in the training dataset and of 0.62 in the validation dataset (Supplemental Figure 1). The sensitivity and specificity for the model to predict near-term surgery within 2 years was 67% and 73% in the testing set, respectively.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that stricture morphologic classification, imaging observations, and measurements from CTE or MRE, coupled with patient symptoms, can be used to create a model to predict risk of surgery in CD patients with small bowel strictures. Nearly all strictures (96.5%) in our study had inflammation. Our study revealed that strictures that were newly developed strictures on baseline CTE or MRE were significantly associated with near-term risk of surgery within 2 years (P = .006). Incorporation of additional variables that tended to be associated with near-term surgery were used to create a mathematical model that predicted a near-term surgical intervention. Our model requires an assessment of imaging findings, eg, anastomotic stricture (OR, 0.002), bowel wall thickness (OR, 4.7), penetrating complications (OR, 3.1 × 103), newly developed stricture (OR, 7.2 × 107), and clinical symptoms (reflected in our study by HBI).

The achievement and maintenance of radiological response assessed on follow-up CTE or MRE exams has been shown to significantly reduce the risk of surgical intervention.15,27 These estimates were derived in a mixed patient population of patients with active inflammatory CD and small bowel strictures. For patients with strictures that will not respond to medical therapy, delay in surgery can lead to detrimental effects on the patient’s quality of life, repeated hospitalizations, impact on school or work productivity, and escalating expenses. Our analysis found that a new stricture was the only factor associated with near-term surgery in univariate analysis, and that development of a predictive model required information about patient symptoms as well as imaging observations and measurements at CTE or MRE. The model that included anastomotic stricture, bowel wall thickness, penetrating disease, and newly developed stricture (assessable on both CTE and MRE) along with the HBI has a sensitivity of 73% and specificity of 78% when examined in the validation dataset. While the performance of the current model is not yet optimized, it demonstrates that predictive models will require input of both patient symptoms and imaging features. Importantly, our study includes imaging measurements and observations that can be made using either MRE or CTE, so it can be employed in a variety of clinical settings depending on the selecting imaging modality, local expertise, and imaging access. The current suboptimal performance is likely due to several factors, including the relatively limited number of patients, lack of laboratory data, and assessment of combined imaging and patient features at a single time point. Additionally and importantly, surgical indication depends on multiple patient (eg, subjective severity, comorbidities, insurance, their role in household and society) and physician factors (eg, their expertise and aggressiveness), and these factors influence surgical risk in ways that will not be accounted for in an imaging and symptom-based model.

Refinement of patient models for risk of surgery will need to include larger numbers of patients as well as systematic recording of patient symptoms and imaging findings. Accumulation of these data would likely require clinical registries with data input from patient symptom questionnaires as well as systematic reporting and interpretation of CTE or MRE exams. Furthermore, there is no validated patient reported outcome tool to assess patient symptoms related to small bowel strictures, and the incorporation of salient patient features and symptoms in patients with CD-related strictures would likely improve this model. Additionally, the reproducibility of imaging findings outside of tertiary referral institution with CD images experts is currently unknown. Nevertheless, our study shows that such prediction may be possible, with an ability to refine and improve the predictive model with inclusion of more patients.

Grass et al28 recently reported an objective nomogram to predict ileocecal resection within 1 year in patients with a terminal ileal CD stricture. Their nomogram incorporates and relies on imaging findings at CTE or MRE to detect penetrating complications and upstream bowel dilation, in addition to young age to predict risk of ileocecal resection.28 Our results demonstrated that penetrating complications and patient symptoms, in addition to bowel wall thickness and other observations, were significantly correlated with near-term risk of surgery, but that age and proximal small bowel dilation were not. There are several reasons for potential differences between our study and that of Grass et al: we did not focus on exclusively terminal ileal strictures; we may have included a higher proportion of complex enteroenteric strictures, which can cause decompression of proximal small bowel dilation; the temporal endpoint for surgery was different; and different methods were used to develop the models. Moreover, the understanding of CD-related strictures is rapidly evolving: 2018 marked the agreement of an imaging-based definition for small bowel strictures using the Society of Abdominal Radiology/American Gastroenterological Association/CONSTRICT criteria.14,17,18 This study marks the first attempt to morphologically classify strictures from CD: strictures with inflammation, strictures without inflammation and multifocal strictures without inflammation, and strictures associated with penetrating complications.

Higher HBI score was a predictor for near-term risk of surgery within 2 years with high OR in the multivariable model but was not associated with risk of surgery by itself in univariate analysis, keeping with prior assessments that clinical symptoms are not accurately correlated with disease severity.29

There are several limitations to this study. Our model is based on a retrospective analysis and with limited numbers of patients owing to the need for stricturing small bowel CD, serial enterography exams, and need for clinical follow-up. While we have estimated robustness of results using 5-fold cross-validation, the model should be refined and validated in a larger prospective study. However, it represents a first step and could be refined as more patients are included. Limiting the model to MRE would permit inclusion of potentially responsive variables that can be assessed by MR imaging such as intramural T2 signal and diffusion restriction; however, this would limit generalizability. Interobserver reproducibility for the measurements and observations made by the gastrointestinal radiologists evaluating the exams is not known for many of the collected model inputs (especially given the 2 imaging modalities), and potential differences in radiologists may contribute to model inaccuracy. Additionally, the individual rationale for surgery (eg, clinical symptoms, penetrating complications on CTE or MRE, patient and provider preference) could not be determined or assessed for each patient. Indeed, many patients who require surgery refuse intervention and are willing to live with their disease regardless of symptoms or imaging findings. Moreover, we analyzed, trained, and tested the model using patients referred to a tertiary referral institution. The extrapolation of the results of this study to primary and secondary referral institutions may be limited. Additionally, we defined one important criterion affecting surgery as “newly developed” stricture on CTE or MRE; it is possible that some patients may have had prior CTE or MRE that were not available in our institutional imaging archives. Medication at the baseline CTE or MRE, which may affect the surgical intervention, was heterogeneous; however, there appeared to be little difference in the medications between the 2 groups. We did not include laboratory markers in the study, owing to its retrospective nature, availability in a minority of patients, and nonstandard assessment; prospective concurrent collection of laboratory markers may be contributory. Besides, the HBI does not fully capture obstructive symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, weight loss, distention, and bloating. The HBI also does not capture any dietary restrictions that have been implemented by the patient and not captured in their medical record in the absence of a prospective dietary assessment. We believe that a standardized assessment of obstructive symptoms would greatly benefit the care of patients with small bowel strictures; however, this is incomplete and inconsistently done in clinical practice. A patient reporting outcome tool that reproducibly reflects obstructive symptoms is greatly needed and could potentially benefit future predictive models and provide needed guidance to clinicians.

Conclusions

Imaging measurements and observations from CTE or MRE, in combination with patient symptoms as summarized in the HBI, can potentially be used to predict which patients will require near-term surgery with a modest degree of accuracy. In the future, we anticipate that future modeling will incorporate improved assessment of obstructive symptoms. Nevertheless, patient symptoms represented in the HBI, combined with multiple imaging findings such as presence of penetrating disease, anastomotic stricture, bowel wall thickness, and newly developed stricture were significant predictors of near-term surgery. Predicting the need for surgery may be helpful to patients in making treatment decisions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant retrospective study was approved by our institutional review board. All patients consented to the use of medical records for research purposes.

Contributor Information

Akitoshi Inoue, Department of Radiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA.

David J Bartlett, Department of Radiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA.

Narges Shahraki, Center for the Science of Health Care, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA.

Shannon P Sheedy, Department of Radiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA.

Jay P Heiken, Department of Radiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA.

Benjamin A Voss, Department of Radiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA.

Jeff L Fidler, Department of Radiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA.

Mohammad S Tootooni, Department of Health Informatics & Data Science, Loyola University Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Mustafa Y Sir, Applied Science Manager, Amazon Care, Amazon, Seattle, WA, USA.

Kalyan Pasupathy, Applied Science Manager, Amazon Care, Amazon, Seattle, WA, USA.

Mark E Baker, Abdominal Imaging Section, Imaging Institute, Digestive Diseases and Surgery Institute, Cancer Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, USA.

Florian Rieder, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition; Digestive Diseases and Surgery Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Ohio, USA.

Amy L Lightner, Department of Colorectal Surgery, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA.

Parakkal Deepak, Division of Gastroenterology, Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USAand.

David H Bruining, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA.

Joel G Fletcher, Department of Radiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA.

Conflicts of Interest

M.E.B. has received grants/funding to the institution from Siemens Healthineers, the Leona M. & Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, and Pfizer. F.R. has served as a consultant or on the advisory board for Agomab, Allergan, AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene/BMS, CDISC, Cowen, Galmed, Genentech, Gilead, Gossamer, Guidepoint, Helmsley, Index Pharma, Jannsen, Koutif, Mestag, Metacrine, Morphic, Organovo, Origo, Pfizer, Pliant, Prometheus Biosciences, Receptos, RedX, Roche, Samsung, Surmodics, Surrozen, Takeda, Techlab, Theravance, Thetis, UCB, Ysios, and 89Bio; and received funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Helmsley Charitable Trust, the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, UCB, Pliant, BMS, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Morphic, and the Kenneth Rainin Foundation. P.D. has served as a consultant or on the advisory board for Janssen, Pfizer, Prometheus Biosciences, Boehringer Ingelheim, AbbVie, and Arena Pharmaceuticals; received funding from Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb-Celgene, Boehringer Ingelheim, and the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust; and received the Junior Faculty Development Award from the American College of Gastroenterology and the IBD Plexus of the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation. D.H.B. has received research Support from Takeda and Medtronic; and served as a consultant for Medtronic. J.G.F. has received grants to the institution from Siemens Healthineers, Takeda, the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, and Pfizer; and served as consultant (funds to institution) from Takeda, Medtronic, Janssen, and GSK. The other authors disclose no conflicts.

References

- 1. Cosnes J, Cattan S, Blain A, et al. Long-term evolution of disease behavior of Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8:244-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Torres J, Mehandru S, Colombel JF, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2017;389:1741-1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Toh JW, Stewart P, Rickard MJ, et al. Indications and surgical options for small bowel, large bowel and perianal Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:8892-8904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Loftus EV Jr, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ. The natural history of adult Crohn’s disease in population-based cohorts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:289-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Deepak P, Fletcher JG, Fidler JL, Bruining DH. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance enterography in Crohn’s disease: assessment of radiologic criteria and endpoints for clinical practice and trials. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2280-2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nehra AK, Sheedy SP, Wells ML, et al. Imaging findings of ileal inflammation at computed tomography and magnetic resonance enterography: what do they mean when ileoscopy and biopsy are negative? J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:455-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Siddiki HA, Fidler JL, Fletcher JG, et al. Prospective comparison of state-of-the-art MR enterography and CT enterography in small-bowel Crohn’s disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:113-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guglielmo FF, Anupindi SA, Fletcher JG, et al. Small bowel crohn disease at CT and MR enterography: imaging atlas and glossary of terms. Radiographics. 2020;40:354-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Deepak P, Fletcher JG, Fidler JL, et al. Radiological response is associated with better long-term outcomes and is a potential treatment target in patients with small bowel Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:997-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rimola J, Rodriguez S, García-Bosch O, et al. Magnetic resonance for assessment of disease activity and severity in ileocolonic Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2009;58:1113-1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Steward MJ, Punwani S, Proctor I, et al. Non-perforating small bowel Crohn’s disease assessed by MRI enterography: derivation and histopathological validation of an MR-based activity index. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:2080-2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fidler JL, Guimaraes L, Einstein DM. MR imaging of the small bowel. Radiographics. 2009;29:1811-1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baker ME, Hara AK, Platt JF, et al. CT enterography for Crohn’s disease: optimal technique and imaging issues. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40:938-952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bruining DH, Zimmermann EM, Loftus EV Jr, et al.; Society of Abdominal Radiology Crohn’s Disease-Focused Panel. Consensus recommendations for evaluation, interpretation, and utilization of computed tomography and magnetic resonance enterography in patients with small bowel Crohn’s disease. Radiology. 2018;286:776-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Deepak P, Fletcher JG, Fidler JL, et al. Predictors of durability of radiological response in patients with small bowel Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:1815-1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Waljee AK, Wallace BI, Cohen-Mekelburg S, et al. Development and validation of machine learning models in prediction of remission in patients with moderate to severe Crohn disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e193721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rieder F, Bettenworth D, Ma C, et al. An expert consensus to standardise definitions, diagnosis and treatment targets for anti-fibrotic stricture therapies in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48:347-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bruining DH, Zimmermann EM, Loftus EV Jr, et al.; Society of Abdominal Radiology Crohn’s Disease-Focused Panel. Consensus recommendations for evaluation, interpretation, and utilization of computed tomography and magnetic resonance enterography in patients with small bowel Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1172-1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55:749-753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grand DJ, Guglielmo FF, Al-Hawary MM. MR enterography in Crohn’s disease: current consensus on optimal imaging technique and future advances from the SAR Crohn’s disease-focused panel. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40:953-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ehman EC, Sheedy S, Barlow JM, et al. Development of a CT enterography severity score for small bowel Crohn’s disease [poster]. In: 104th Scientific Assembly and Annual Meeting of the Radiological Society of North America, Chicago, IL; November 25-30, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ehman EC, Sheedy S, Barlow JM, et al. The London score for severity of active SB inflammation at MR enterography (MRE): Can we extend this measure to CT enterography (CTE)? In: SAR Annual Scientific Meeting and Educational Course, Orlando, FL; March 17-22, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Orscheln ES, Dillman JR, Towbin AJ, et al. Penetrating Crohn disease: does it occur in the absence of stricturing disease? Abdom Radiol (NY). 2018;43:1583-1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the Lasso. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1996;58:267-288. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim SM, Kim Y, Jeong K, et al. Logistic LASSO regression for the diagnosis of breast cancer using clinical demographic data and the BI-RADS lexicon for ultrasonography. Ultrasonography. 2018;37:36-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McEligot AJ, Poynor V, Sharma R, et al. Logistic LASSO Regression for Dietary Intakes and Breast Cancer. Nutrients. 2020;12:2652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ma C, Fedorak RN, Kaplan GG, et al. Long-term maintenance of clinical, endoscopic, and radiographic response to ustekinumab in moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease: real-world experience from a multicenter cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:833-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Grass F, Fletcher JG, Alsughayer A, et al. Development of an objective model to define near-term risk of ileocecal resection in patients with terminal ileal Crohn disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25:1845-1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Reinisch W, Colombel JF, et al. Clinical disease activity, C-reactive protein normalisation and mucosal healing in Crohn’s disease in the SONIC trial. Gut. 2014;63:88-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.