Abstract

This case report describes the ethical implications of paradoxical lucidity in persons with severe stage dementia. Paradoxical lucidity describes an episode of unexpected communication or connectedness in a person who is believed to be noncommunicative due to a progressive and pathological process that causes dementia. A caregiver who witnesses an event of paradoxical lucidity may experience it as ethically and emotionally transformative. We provide an ethical framework for addressing this event in clinical practice. The framework addresses clinician interactions with the patient, caregiver, and family to improve understanding of paradoxical lucidity and to enhance patient care, caregiver wellbeing, and decision making. Participants for this case study consented to having the case published. Participant names are changed to protect confidentiality.

Dan’s Spark of Mental Clarity

After Dan’s seventieth birthday, when he couldn’t figure out how to operate a new car, his wife Helen became concerned. Dan’s temper had sharpened and his finances were sloppy. A medical evaluation confirmed a diagnosis of dementia most likely caused by Alzheimer’s disease. As his disease progressed, Dan and Helen’s relationship changed. His cognitive problems increased, and she gradually transformed into his caregiver. Some nights, Helen would sit with him and go through photographs to rekindle memories, but he would never recall the people or stories she asked about.

One evening, when Dan’s wife and daughter were leafing through the photographs with him, Dan said a name. And another. And then another. He rattled off the names of twelve buddies from his army unit in a photograph. His voice was shaky, but the names were clear. Helen cried out and Dan basked in her joy. But as quickly as Dan found his voice, it faded. For another moment, it appeared as if he was trying to express something but could not. And then this spark of mental clarity was gone.

The episode lasted no more than a minute, but for Helen it reverberated for years, transforming how she thought about her husband and his disease. Helen had understood neurodegeneration as a one-way street, but now she questioned whether his disease had changed course. She saw the spontaneous change as a sign that, with more aggressive care, remnants of her husband’s past self might be salvaged. But when Helen spoke about the episode with her family and Dan’s clinicians, she encountered indifference at best and condescension at worst.

Their daughter, Annie, who had also witnessed the episode, viewed it as nothing more than a “short circuit” in Dan’s brain. Dan’s physician described the episode as just an instance of “mental hijinks” that persons living with dementia sometimes display late in life.

Paradoxical Lucidity

The preceding case report—about a spontaneous instance of mental clarity in a person living with dementia—is a common story among clinicians and caregivers. Sampled case studies suggest that such episodes are characterized by unexpected changes in a person’s communication or nonverbal behavior, such as eye contact, and could be triggered by familiar voices or music.1–7 These episodes differ from the waxing and waning in cognition—or “good days” and “bad days”—often observed in persons living with dementia. The episodes are unexpected relative to a patient’s clinical status and are often fleeting and irreproducible.

These episodes are described in the clinical literature as “paradoxical lucidity.” Paradoxical lucidity involves “unexpected, spontaneous, meaningful and relevant communication or connectedness in a patient who is assumed to have permanently lost the capacity for coherent verbal or behavioral interaction due to a progressive and pathophysiological dementing process.”8 To date, the clinical characterization and neurobiology of paradoxical lucidity are poorly understood. However, anecdotal reports suggest that most episodes last no more than an hour and precede death by 72 hours or less.1,3 Paradoxical lucidity is therefore sometimes referred to as “terminal lucidity,” though reports suggest that episodes of lucidity can happen long before a person dies.

In 2018, the U.S. National Institute on Aging (NIA) held an expert workshop that mapped a research agenda to discover the clinical significance of paradoxical lucidity. Among the insights of the workshop report was the recognition that, “[i]n addition to its important neurobiological implications, paradoxical lucidity has important ethical implications,” and that “research and clinical translation related to paradoxical lucidity should draw on an ethical framework.”8 Ethical challenges can arise for both caregivers and clinicians when probing the meaning in these episodes. Caregivers, who want to do what is best for their loved ones, might question their decisions about care plans after they witness paradoxical lucidity. Clinicians, also wanting to provide the best medical care, may lack a coherent understanding of paradoxical lucidity, which challenges their ability to help.

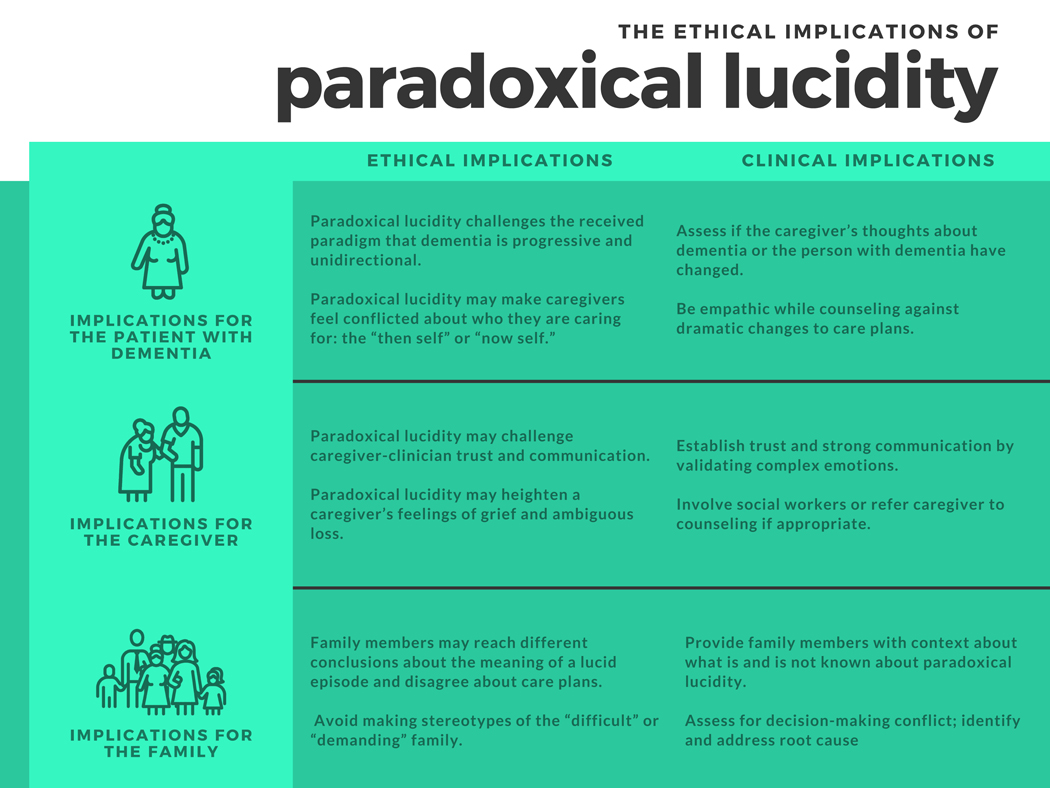

This case report outlines an ethical framework, illustrated in Figure 1., for the care of persons living with dementia who exhibit paradoxical lucidity. We identify the ethical implications of paradoxical lucidity for the patient, the caregiver, and the family. Caregivers may interpret the lucid episode as a rediscovery of the personhood of the patient. Paradoxical lucidity is “paradoxical” precisely because it conflicts with the received paradigm that neurodegeneration is both progressive and unidirectional. People who exhibit paradoxical lucidity disrupt this paradigm,9 which can challenge a caregiver’s understanding of dementia and possibly alter patient care. This can lead to emotional tensions for caregivers, and potentially interfamily conflict. Such episodes can be ethically and emotionally transformative for caregivers. Clinicians must be prepared to address these concerns.

Figure 1:

Ethical Implications of Paradoxical Lucidity

1. Ethical Implications for the Care of the Patient with Dementia

“Personhood” is an ethical concept that describes an individual who has intrinsic value.10 Persons should enjoy experiences, make plans, have goals, build relationships, form identities, and exercise their agency in the world. When we recognize individuals as persons, we have ethical obligations to treat them with dignity. Persons are not treated as means-to-an-end; they are neither inanimate objects nor slaves. Persons can be harmed and so have inherent worth that must be respected.

We recognize someone as a person, in part, because of her cognitive abilities, including memory, language, and executive function. These cognitive abilities allow individuals to exercise their personhood; they form the foundation of what makes us human. Progressive dementia, however, erodes these abilities and, by extension, an individual’s personhood.11 In culture and clinical practice, the loss of personhood in people living with dementia is often expressed in ethically charged phrases, such as “loss of self” or “death before death,” implying that one must have these cognitive abilities to be socially alive.12

Over the course of dementia, an individual’s personhood transforms. These changes can be so significant that ethicists and clinicians speak of the person having two selves: the “then self” and the “now self.”13 The former describes who the person was early on, or even prior to their dementia. The latter describes who the person is in their present stage of the disease. This change in personhood creates an ethical dilemma for caregivers. Caregivers often struggle with the questions: Who is the person I am caring for? Should I make decisions that respect the “then self” or the “now self”?

Witnessing an episode of paradoxical lucidity can intensify this dilemma. Helen witnessed Dan’s “then self,” juxtaposing who Dan was with who Dan presently is. This led her to question the identity of the person she was caring for. Helen felt that the “now Dan”—the man unable to recognize images in photos—and the “then Dan”—the husband she loved who talked about his experiences in the war—were simultaneously present in those 60 seconds of clarity. This resulted in Helen questioning her understanding of dementia and her treatment decisions. Over the course of caring for her husband, Helen internalized the message that Alzheimer’s disease is progressive and irreversible. Dan saw fewer clinicians, Helen resisted administering new medications, and they spent more time apart as his disease advanced. But Dan’s episode of lucidity collapsed this framework. She believed latent aspects of her husband’s past self were still present. She had a newfound moral duty to pull that person back from oblivion.

Nightly, Helen quizzed Dan with photographs. She consulted with Dan’s doctors to see if a change in medication or increased rehabilitation might help. She even began to take her husband on “dementia dates,” visiting their favorite restaurants with the hope that Dan would enjoy the experience, even if he couldn’t express it. Helen’s behaviors were a result of hope, but also shame and guilt. She castigated herself for “giving up” too soon and obsessed over interventions that might spark more lucid episodes.

Caregivers, like Helen, may approach clinicians after an episode of paradoxical lucidity to request changes in care plans. Although caregivers may have good intentions with these decisions, dramatic shifts in care could be harmful to the patient. Abrupt treatment changes can disrupt care continuity. Confusion about care obligations to the “now self” versus the “then self” might obfuscate a mutually agreed upon care plan and undermine the previously expressed wishes of the patient. Clinical conversations about paradoxical lucidity should be empathetic, but to avoid false hope, clinicians must council caregivers with evidence-based recommendations about the outcomes of interventions for a person at the present stage of disability caused by dementia.

An episode of paradoxical lucidity might also raise ethical questions about patient autonomy. For Dan and Helen, the lucid episode was characterized by his recovered memories. But it is also plausible that paradoxical lucidity could manifest as a verbal preference, such as a person expressing that she doesn’t want to be seen by a particular nurse. How should a clinician respond to preferences expressed during an episode of paradoxical lucidity?

The ethical principle of respect for persons requires that clinicians promote the autonomy of patients, while also protecting those who lack the capacity to make decisions independently.14 Persons living with dementia who exhibit paradoxical lucidity likely have significantly impaired decision-making abilities. Therefore, in most cases, it would be unethical to acquiesce to a patient’s preferences expressed during a lucid episode, especially if those preferences impede medical care. Nonetheless, finding a place for patient preferences in the overall care plan—even if expressed during a lucid episode—shows respect for the dignity of persons living with dementia. Preferences that don’t negatively impact patient care—like food choice or types of activities—could guide daily decision making. Dementia is, fundamentally, a disease that erodes autonomy. Clinicians should therefore seize every opportunity to shore up patient self-determination.

2. Ethical Implications for the Care of the Caregiver

Caring for persons living with dementia places significant burdens on people in caregiving roles.15 Caregiving involves making decisions, assisting with instrumental and basic activities of daily living, and coordinating care. Caregivers are sometimes referred to as “invisible second patients,” as their work often requires them to surrender their own independent identity to function as a “dyad” with their loved one.16 Trust and strong communication between clinicians and caregivers can enhance these dyadic relationships and potentially lead to improved caregiver wellbeing and decision making.

The way that clinicians respond to caregivers’ interpretation of paradoxical lucidity can impact trust and communication. Knowledge of paradoxical lucidity is contingent on the reports of caregivers, as is the case with much of the information clinicians gather to care for persons with dementia. Nevertheless, without a way to verify an episode of lucidity, clinicians might question these reports as confabulations or “wishful thinking.” This skepticism could lead to condescension and subsequent erosion of trust with caregivers.

Dan’s physician, for instance, was not attentive to or respectful of Helen’s concerns. After Helen witnessed Dan’s lucid episodes, she had a different understanding of Dan’s personhood, which prompted her to investigate medical options with renewed urgency. These clinical interactions, however, were emotionally draining. Helen was particularly frustrated that, at their first clinical visit after the episode, Dan’s physician administered the same tests, offered no new medications, and was seemingly uninterested in her reports. Dan’s physician was “amused” by the episode and described it as something to “share at a cocktail party,” not something of clinical significance. This set the tone for all their follow-up visits.

Caregivers’ perceptions of paradoxical lucidity are also set upon a complex emotional background. Besides regret and shame, as discussed above, caregivers might also have feelings of ambiguous loss. Ambiguous loss describes a dissonance in grieving caused by a loved one being physically present, but psychologically absent.17 Families of persons with severe neurological injuries or disease perceive their loved ones as both “there” and “not there” at the same time, forestalling closure and the capacity to let go.18,19 Among caregivers of persons living with dementia, feelings of ambiguous loss are common.20

Caregivers who witness paradoxical lucidity might have heightened feelings of ambiguous loss, leading to beliefs that their loved one is “still in there” despite their clinical presentation. Episodes of lucidity can trigger dissonant emotions. Helen, for instance, cried out for joy when Dan recognized his friends in the photograph. Yet, as time passed, these feelings gave way to grief over the loss of her husband even though she believed he still might be present or aware of his surroundings. Other cases of paradoxical lucidity might be more distressing. A caregiver for a person who exhibits paradoxical lucidity when physically resisting bathing or toileting might view the episode as a cruel reminder that her loved one is already gone.

Caregivers’ emotional wellbeing can affect daily and clinical decisions for persons living with dementia. Failure of clinicians to recognize, acknowledge, and attend to these complex feelings could erode caregiver-clinician trust and communication. To avoid this, clinicians should anticipate possible episodes of paradoxical lucidity and equip caregivers with knowledge to document them so they can be evaluated more thoroughly. Listening to caregivers’ reports of episodes of lucidity—even if found to be clinically insignificant—can enhance the clinician-caregiver relationship. Clinicians should also be aware that ambiguous loss is often a baseline emotional state for caregivers; experiencing paradoxical lucidity may heighten these dissonant feelings, and such episodes might not always bring good experiences. When caregivers are distressed, clinicians should be prepared to refer them for appropriate counseling.21,22

3. Ethical Implications for the Care of the Family

Dementia is a disease of the family, not of individual patients. As caregivers provide critical support for the person living with dementia, a network of family and friends support the caregiver and the patient. When family members—a spouse or adult children—agree on daily and clinical decisions, support for the person with dementia follows a smooth division of labor. When there is interfamily conflict over diagnosis, medical decisions, or finances, the quality of patient care may suffer.

Changes in care decisions that follow an episode of paradoxical lucidity could be a flashpoint for interfamily conflict. Helen, for instance, was focused on the long-term ramifications of Dan’s lucid episode while their daughter, Annie, was more skeptical. Annie was not convinced that her father had re-emerged in a significant way, or that she had witnessed a sign of potential clinical improvement. Instead, she interpreted his lucid episode as a happy accident in a long line of tragedies. She shared her mother’s sense of surprise, but it did not cause her to revisit his prognosis or second-guess her caregiving efforts. She had already moved on.

Neither Annie’s nor Helen’s interpretation is necessarily wrong. They arrived at different conclusions of what the lucid episode meant for Dan’s health, and so they disagreed about what should be done. This kind of decisional conflict occurs often. Decision scientists attribute such conflict to: 1) a lack of information about different options; 2) inadequate clarity about potential pros and cons from each possible choice; and 3) insufficient social support.23,24 Caregivers experience less conflict when making decisions for others when they have sufficient information, when they understand the outcomes, and when they feel supported from health care professionals, family, and friends.25 This guidance may be instructive for supporting families as they process the meaning of a lucid episode.

Clinicians should be aware that paradoxical lucidity could precipitate disagreement regarding the interests of the patient. They may be the cause of the “demanding” or “difficult” family. Helen’s general orientation toward care decisions changed because she glimpsed the past self of her husband; she felt compelled—even guilted—to care for this person. Annie, on the other hand, remained steadfast in viewing her father as his current self, significantly impaired from his dementia. Recognizing the nuance of this decisional conflict can help clinicians identify the root of the problem and address this discrepancy. Annie and Helen did not necessarily need further information to process the episode of lucidity. Rather, their ethical orientations toward the episode differed in important ways. Such insight can help clinicians de-escalate disagreements within families while avoiding “taking sides.”

Conclusion

One year after his lucid episode, Dan suffered a stroke and died. Years after his death, Helen readily recalls the onset of his disease and the days leading up to his death. Few moments stand out in the intervening years, except one: the night in the twilight of his life when she witnessed her husband find himself, at the dining room table, for those fleeting 60 seconds.

Paradoxical lucidity in persons living with dementia may be more ubiquitous than assumed and have far-reaching ethical implications that have yet to be explored. Figure 1. provides a preliminary ethical framework for these implications—focusing on the patient, caregiver, and family—and outlines recommendations for clinicians to address them. Approaching caregivers who have witnessed paradoxical lucidity with humility and respect may ultimately improve patient care in this deserving population.

Key Points:

Clinicians need to understand the ethical implications of witnessing paradoxical lucidity in persons with dementia.

How clinicians respond to caregivers’ reports of paradoxical lucidity can impact patient care and caregivers’ well-being.

This paper matters because: clinicians should be prepared to discuss paradoxical lucidity to assure patients, caregivers, and families receive ethically appropriate care.

Acknowledgements:

The subjects of this case generously provided this story to the authors for analysis. Their verbal consent was attained for publishing purposes. We would like to acknowledge and thank them for sharing a difficult memory with the goal of helping others with similar experiences. AP is supported by the Greenwall Foundation Faculty Scholars program and NIA/NIH R21AG069805.

Sponsor’s role:

This work is funded by NIA/NIH R21AG069805. The NIA/NIH had no role in the project.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest:

David Ney: None

Andrew Peterson: None

Jason Karlawish: Dr. Karlawish is a site PI for clinical trials sponsored by Lilly Inc, Biogen and Esai.

References:

- 1.Batthyány A, Greyson B. Spontaneous remission of dementia before death: Results from a study on paradoxical lucidity. Psychol Conscious Theory Res Pract. Published online 2020:No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified. doi: 10.1037/cns0000259 [DOI]

- 2.Bright R. Music therapy in the management of dementia. In: Jones G, Miesen B, eds. Care-Giving in Dementia: Volume 1: Research and Applications. Routledge; 1992:162–180. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nahm M, Greyson B. Terminal Lucidity in Patients With Chronic Schizophrenia and Dementia: A Survey of the Literature. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197(12):942–944. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181c22583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nahm M, Greyson B, Kelly EW, Haraldsson E. Terminal lucidity: A review and a case collection. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55(1):138–142. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2011.06.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Normann HK, Asplund K, Norberg A. Episodes of lucidity in people with severe dementia as narrated by formal carers. J Adv Nurs. 1998;28(6):1295–1300. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00845.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Normann HK, Norberg A, Asplund K. Confirmation and lucidity during conversations with a woman with severe dementia. J Adv Nurs. 2002;39(4):370–376. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02298.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norberg A, Melin E, Asplund K. Reactions to music, touch and object presentation in the final stage of dementia: an exploratory study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2003;40(5):473–479. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7489(03)00062-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mashour GA, Frank L, Batthyany A, et al. Paradoxical lucidity: A potential paradigm shift for the neurobiology and treatment of severe dementias. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(8):1107–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peterson A, Clapp J, Largent EA, Harkins K, Stites SD, Karlawish J. What is paradoxical lucidity? The answer begins with its definition. Alzheimers Dement. n/a(n/a). doi: 10.1002/alz.12424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Dennett D. Are we explaining consciousness yet? Cognition. 2001;79(1):221–237. doi: 10.1016/S0010-0277(00)00130-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitwood T, Bredin K. Towards a theory of dementia care: personhood and well-being. Ageing Soc. 1992;12:269–287. doi: 10.1017/s0144686x0000502x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sweeting H, Gilhooly M. Dementia and the phenomenon of social death. Sociol Health Illn. 1997;19(1):93–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.1997.tb00017.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein E, Karlawish J. Ethics of Dementia Care. In: Principles and Practice of Geriatric Psychiatry. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2010:410–414. doi: 10.1002/9780470669600.ch65 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Research USNC for the P of HS of B and B. The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. The Commission; 1978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Etters L, Goodall D, Harrison BE. Caregiver burden among dementia patient caregivers: A review of the literature. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20(8):423–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00342.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brodaty H, Donkin M. Family Carers of People with Dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11:217–228. doi: 10.1201/b13196-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nathanson A, Rogers M. When Ambiguous Loss Becomes Ambiguous Grief: Clinical Work with Bereaved Dementia Caregivers. Health Soc Work. 2021;45(4):268–275. doi: 10.1093/hsw/hlaa026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doherty WJ, Boss PG, LaRossa R, Schumm WR, Steinmetz SK. Family Theories and Methods. In: Boss P, Doherty WJ, LaRossa R, Schumm WR, Steinmetz SK, eds. Sourcebook of Family Theories and Methods: A Contextual Approach. Springer US; 1993:3–30. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-85764-0_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peterson A, Kostick KM, O’Brien KA, Blumenthal-Barby J. Seeing minds in patients with disorders of consciousness. Brain Inj. 2020;34(3):390–398. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2019.1706000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blieszner R, Roberto KA, Wilcox KL, Barham EJ, Winston BL. Dimensions of Ambiguous Loss in Couples Coping With Mild Cognitive Impairment*. Fam Relat. 2007;56(2):196–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00452.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanders S, Sharp A. The Utilization of a Psychoeducational Group Approach for Addressing Issues of Grief and Loss in Caregivers of Individuals with Alzheimer’s Disease. J Soc Work Long-Term Care. 2004;3(2):71–89. doi: 10.1300/J181v03n02_06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meichsner F, Wilz G. Dementia caregivers’ coping with pre-death grief: effects of a CBT-based intervention. Aging Ment Health. 2018;22(2):218–225. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1247428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Connor AM. Validation of a Decisional Conflict Scale. Med Decis Making. 1995;15(1):25–30. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jung Kwak, De Larwelle Jessica A, O’Connell Valuch Katharine, Toni Kesler. Role of Advance Care Planning in Proxy Decision Making Among Individuals With Dementia and Their Family Caregivers. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2016;9(2):72–80. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20150522-06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang Y-P, Schneider JK, Sessanna L. Decisional conflict among Chinese family caregivers regarding nursing home placement of older adults with dementia. J Aging Stud. 2011;25(4):436–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2011.05.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]