Abstract

Background:

Increased risks of cerebral cerebral venous thrombosis or subdural hematoma, bacterial meningitis, persistent headache, and persistent low back pain are suggested in obstetric patients with post-dural puncture headache (PDPH). Acute postpartum pain such as PDPH may also lead to postpartum depression. This study tested the hypothesis that PDPH in obstetric patients is associated with significantly increased postpartum risks of major neurologic and other maternal complications.

Methods:

This retrospective cohort study consisted of 1,003,803 women who received neuraxial anesthesia for childbirth in New York State hospitals between January 2005 and September 2014. The primary outcome was the composite of cerebral venous thrombosis and subdural hematoma. The 4 secondary outcomes were bacterial meningitis, depression, headache, and low back pain. PDPH and complications were identified during the delivery hospitalization and up to 1 year post-delivery. Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence interval (CIs) were estimated using the inverse probability of treatment weighting approach.

Results:

Of the women studied, 4808 (0.48%; 95% CI, 0.47–0.49) developed PDPH, including 264 cases (5.2%) identified during a readmission with a median time-to-readmission of 4 days. The incidence of cerebral venous thrombosis and subdural hematoma was significantly higher in women with PDPH than in women without PDPH (3.12 per 1000 neuraxial or 1:320 versus 0.16 per 1000 or 1:6250, respectively; P < 0.001). The incidence of the 4 secondary outcomes was also significantly higher in women with PDPH than in women without PDPH. The aORs associated with PDPH were 19.0 (95% CI, 11.2–32.1) for the composite of cerebral venous thrombosis and subdural hematoma, 39.7 (95% CI, 13.6–115.5) for bacterial meningitis, 1.9 (95% CI, 1.4–2.6) for depression, 7.7 (95% CI, 6.5–9.0) for headache, and 4.6 (95% CI, 3.3–6.3) for low back pain. Seventy percent of cerebral venous thrombosis and subdural hematoma were identified during a readmission with a median time-to-readmission of 5 days.

Conclusion:

PDPH is associated with substantially increased postpartum risks of major neurologic and other maternal complications, underscoring the importance of early recognition and treatment of anesthesia-related complications in obstetrics.

Introduction

Post-dural puncture headache (PDPH) is the most frequent complication occurring after a neuraxial anesthetic in obstetric patients.1 In the 2004–2009 multicenter Serious COmplication REpository (SCORE) project aiming to estimate the incidence of serious complications related to obstetric anesthesia care, 0.7% of women who received neuraxial anesthetic developed PDPH.2 The risk of PDPH is estimated at about 50% after an accidental dural puncture with an epidural needle; it ranges between 1 % and 10% after a dural puncture with a spinal needle, depending on the needle size and type.3 Although often considered minor, PDPH may hinder women’s’ ability to perform daily activities, including caring for their baby and delays hospital discharge. It may also lead to hospital readmission and accounts for about 1% of postpartum readmissions.4 Furthermore, PDPH constituted 15% of claims associated with neuraxial anesthesia in obstetrics in the 1990–2003 ASA Closed Claims Study.5 PDPH still accounts for a significant proportion of liability claims in obstetrics.6

Case reports indicate that major, severe, life-threatening neurologic complications may follow PDPH in obstetric patients including subdural hematoma, cerebral venous thrombosis, or bacterial meningitis.7,8 The 2009–2012 United Kingdom Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Death (MBRRACE-UK) report that 2 of the 4 deaths associated with neuraxial anesthesia in obstetrics resulted from complications of accidental dural puncture during epidural catheter placement: 1 cerebral vein thrombosis and 1 subdural hematoma.9 In addition, retrospective surveys or retrospective case-controlled studies suggest an increased risk of persistent headache or persistent back pain in obstetric patients.10–13. Last, acute pain after childbirth such as pain associated with PDPH has been associated with an increased risk of postpartum depression.14 Similarly, acute or persistent headache or back pain have been associated with the development of depression in adults with no history of depressive disorders, suggesting that PDPH may also be associated with the development of postpartum depression.15 A confirmation of the increased risk of these complications associated with PDPH in obstetrics would indicate the need for heightened surveillance of women with PDPH to timely diagnose and treat these complications. A characterization of the time-to-onset of these complications would also indicate how long this surveillance should be.This study aimed to test the hypothesis that PDPH in obstetric patients is associated with a significantly increased postpartum risks of major neurologic complications (cerebral venous thrombosis, subdural hematoma, and bacterial meningitis), depression, headache, and low back pain.

Methods

The study protocol was granted exemption under 45 Code of Federal Regulation 46 (not human subjects research) by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University Medical Center. The manuscript is reported according to current guidelines.16,17 The study design and analysis plan described below were based on the initial design and plan combined with modifications suggested by peer reviewers.

Data systems

Hospital discharge records of the State Inpatient Database for New York were analyzed. State Inpatient Databases are part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. They capture all inpatient discharges from non-federal acute care community hospitals, including tertiary and academic centers. They do not capture outpatient or emergency department visits. For each discharge, the New York State Inpatient Database indicates the type of anesthesia provided, one hospital identifier allowing linkage with the American Hospital Association Annual Survey Database, and patient diagnoses and procedures performed defined in the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). Furthermore, the HCUP State Inpatient Database provide a variable indicating whether an ICD-9-CM diagnosis code was present on admission or not (variable DXPOA). This variable allows distinguishing a preexisting condition from a complication arising during hospitalization.

For patients with multiple hospitalizations, the New York State Inpatient Database provides a unique readmission identifier (variable VisitLink) that allows tracking patient for previous hospitalizations or readmissions across hospitals and over time. For these patients, a second variable is provided (variable DaysToEvent) that allows calculating the number of days elapsed between admissions.

Hospital characteristics were calculated from the State Inpatient Database or obtained from the American Hospital Association Annual Survey Database.

Study sample

The study sample included all women admitted for labor and delivery who received neuraxial anesthesia in New York State hospitals between January 1, 2005 and September 30, 2014. Childbirths were identified with a combination of ICD-9-CM diagnosis and procedure codes as previously described (Supplemental Table 1).18 The last 3 months of the year 2014 were not included because data for the last 3 months of the year 2015 were coded according to ICD-10-CM. ICD-9-CM codes and algorithms used in this study have not been validated based on ICD-10-CM-coded data.

New York State Inpatient Database is the only HCUP participating state providing information on anesthesia care. Anesthesia type is reported as a categorical variable with values corresponding to general, regional (neuraxial), other, local, none, and missing. Each discharge record contains a maximum of one value for anesthesia type. For example, a woman who received general anesthesia for cesarean delivery because of a failed epidural catheter will be coded as general anesthesia, and the initial neuraxial procedure will not be captured. For the purpose of this analysis, the study sample was limited to women who received neuraxial anesthesia.

Exposure

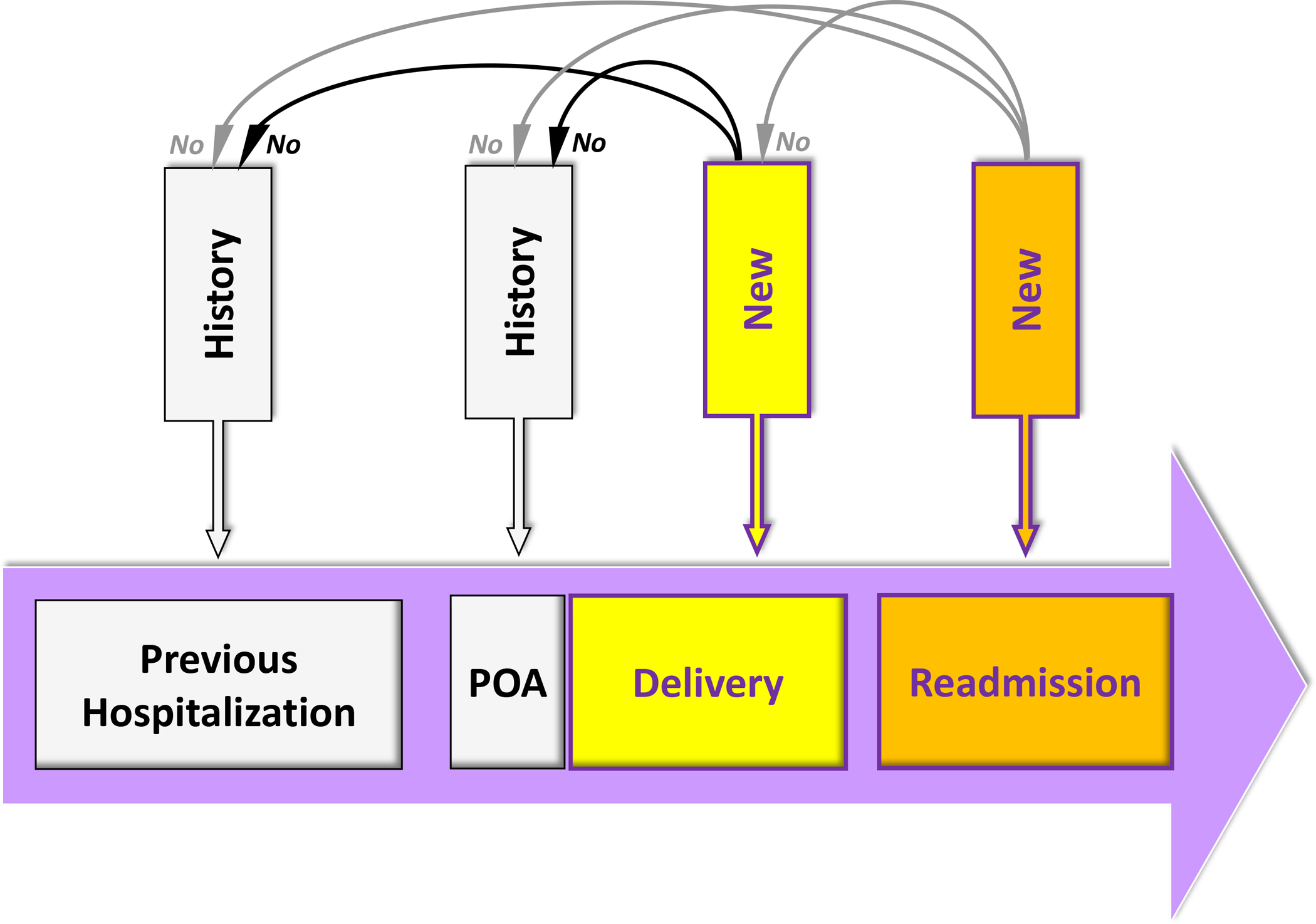

Exposure was the occurrence of PDPH after a neuraxial anesthesia (spinal, epidural, or combined spinal epidural anesthesia) for childbirth identified during the delivery hospitalization or a readmission up to 1 year after discharge in a woman without a previous history of PDPH. PDPH was identified with the ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes 349.0 (“headache following lumbar puncture”) and the ICD-9-CM procedure code 03.95 (“blood patch”). A history of PDPH was defined as a diagnosis of PDPH recorded during the year preceding the delivery hospitalization or present on admission of the delivery hospitalization (Figure 1). PDPH identified during a readmission was not counted if present during the index delivery hospitalization.

Figure 1:

Definitions of history and of new post-dural puncture headache (PDPH) or complication. History of PDPH or complication refers to a diagnosis of PDPH or complication recorded during the year preceding the delivery hospitalization or present on admission (POA) of the delivery hospitalization. New PDPH or complication during the delivery hospitalization refers to a diagnosis of PDPH or complication recorded during the delivery hospitalization among parturients without history of PDPH or complication. New PDPH or complication during a readmission refers to a diagnosis of PDPH or complication recorded during a readmission, up to 1 year after discharge from the index delivery hospitalization, among parturients without history of PDPH or complication and without a new PDPH or complication during the index delivery hospitalization.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the composite of cerebral venous thrombosis and non-traumatic subdural hematoma. The 4 secondary outcomes were: 1) bacterial meningitis, 2) depression, 3) headache and migraine, and 4) low back pain. Outcomes were further categorized into major neurologic and other complications. The 2 major neurologic complications were 1) the composite of cerebral venous thrombosis and non-traumatic subdural hematoma and 2) bacterial meningitis. The 3 other complications were 1) depression, 2) headache and migraine, and 3) low back pain.

Complications were identified during the delivery hospitalization or a readmission up to 1 year after discharge in a woman without a previous history of the examined complication (Figure 1). These 5 pre-specified maternal complications were defined using specific ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes or algorithms (Supplemental Table 2). A history of complication was defined as a diagnosis of the examined complication recorded during the year preceding the delivery hospitalization or present on admission of the delivery hospitalization (Figure 1). Complications identified during a readmission were not counted if present during the index delivery hospitalization. Complications identified during readmission were considered the reason for readmission if listed in the first or second ICD-9-CM code.

Maternal and hospital characteristics

The following maternal characteristics were recorded directly from the State Inpatient Databases: age, race and ethnicity, insurance type, admission for delivery during a weekend, and admission type (elective or non-elective). In the State Inpatient Database, Hispanic ethnicity is considered as a distinct racial/ethnic group. The Charlson comorbidity index and the comorbidity index for obstetric patients were calculated using previously described ICD-9-CM algorithms.19,20 They were calculated on the basis of conditions that were present or not on admission for the delivery hospitalization. The comorbidity index for obstetric patients was designed specifically for use in obstetric patient populations; it includes maternal age and 20 maternal conditions (e.g., severe preeclampsia/eclampsia or pulmonary hypertension), that are predictive of maternal end-organ injury or death during the delivery hospitalization through 30 days postpartum. Obesity, multiple gestation, and induction of labor were identified with ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes (Supplemental Table 3). Deliveries were categorized into 3 groups: vaginal delivery, non-emergent cesarean delivery, and emergent cesarean delivery. A cesarean delivery was defined emergent if associated with at least one of the 5 following conditions: abnormal fetal heart rhythm, abruptio placenta, placenta praevia with hemorrhage, uterine rupture, or umbilical cord prolapse.

The following hospital characteristics were calculated for each year of the study period using the State Inpatient Database data: volume of delivery, cesarean delivery rate, percent admission for delivery during a weekend, percent neuraxial anesthesia care in deliveries, percent women with Charlson comorbidity index ≥ 1 in deliveries, percent women with comorbidity index for obstetric patients ≥ 2 in deliveries, percent minority women in deliveries, percent Medicaid/care beneficiaries in deliveries, and intensity of coding. For each hospital, the annual intensity of coding was calculated as the mean number of diagnosis and procedure codes, including E-codes, reported per discharge.21 Adjustment on coding intensity is required to take into consideration the marked variations in coding pattern across hospitals and over time.22,23

The following hospital characteristics were obtained from the American Hospital Association Annual Survey Database: hospital location, teaching status, and neonatal level-of-care designation (1, 2 or 3). Hospital location is based on the Core Based Statistical Areas and include 4 categories: core metropolitan statistical areas (50,000 or more population), core metropolitan divisions (2.5 million or more population), core micropolitan statistical areas (at least 10,000 but less than 50,000 population), and non-core. A teaching hospital had an affiliation to a medical school or residency training accreditation. Neonatal level-of-care 1 hospitals provide basic neonatal level of care, level 2 specialty neonatal care (e.g., care of preterm infants with birth weight ≥1500 g), and level 3 subspecialty neonatal intensive care (e.g., mechanical ventilation ≥ 24 hour).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with R version 3.4.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and specific packages (mice for multiple imputations and lme4 for mixed-effect models).

Descriptive statistics

Results are expressed as median (interquartile range) or count (% or per 1000). Univariate comparisons of discharges with and without PDPH used Chi-squared test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. Categorical and continuous variables were also compared using the standardized mean difference (a value greater than 0.1 is usually considered to indicate a relevant difference). Missing values were estimated using multivariable imputation by chained equations with 5 iterations and five imputed datasets created (Supplemental Table 4). Because we examined five complications, we used a Bonferroni correction with a P-value threshold for statistical significance of 0.05/5 = 0.01.

Risk of maternal complications

Unadjusted odds ratios for the 5 complications associated with PDPH were assessed using univariate logistic regression. Complications were the dependent variable and PDPH the independent variable.

Adjusted odds ratios were calculated using an inverse probability of treatment weighting approach.24 The individual probability of PDPH was calculated using a mixed-effects logistic regression model. In this model, the fixed-effects were the year of delivery and all patient and hospital characteristics described in Supplemental Table 5. The random effect was the hospital identifier (normally distributed intercept and constant slope). Both the fixed and random effects were used to calculate the individual probability of PDPH (i.e., the propensity score). Inverse probability weights were calculated using the propensity score. Using weights aims to create a synthetic sample in which the distribution of measured baseline covariates is independent of treatment assignment (i.e., PDPH). Inverse weights were stabilized and truncated at 1 and 99%.25 The likelihood of maternal complications associated with PDPH was quantified with the odds ratio from a mixed-effects logistic regression. In this model, the outcome was the examined complication, the random effect was the hospital identifier, the fixed effect was PDPH, and the weight was the inverse stabilized weight.

In addition, we calculated the E-value associated with the adjusted odds ratio. The E-value estimates how strong an unmeasured confounder (i.e., an unknown factor associated with both PDPH and the complication examined) would need to be to explain away the observed association between PDPH and the complication.26 The lowest possible E-value is 1 and indicates that no unmeasured confounding is needed to explain away the observed association. The higher the E-value, the stronger the confounder association must be to explain away the observed association.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed three sets of sensitivity analysis. First, we limited the identification of complications during readmission to the first and second diagnosis codes. In the main analysis, complications during readmissions were identified among up to 25 possible diagnosis codes. They may therefore indicate preexisting conditions and not complications leading to the readmission. Complications identified in the first or second diagnosis codes are more likely to represent the reason for readmission than a preexisting condition. Second, we restricted the follow-up period for the identification of readmission for PDPH or complications to 3 months after discharge. Third, we compared the risk of the 5 complications examined in women who had a vaginal with neuraxial anesthesia to the risk in women who had a vaginal delivery without neuraxial anesthesia.

Study power consideration

Between January 2005 and September 2014, about 2.5 million deliveries occurred in New York State. Assuming that 50% of these deliveries would be excluded because women did not receive neuraxial anesthesia or the information on anesthesia care was missing and that 0.5% of women receiving neuraxial anesthesia will have PDPH, our estimated study sample size would be 1.25 million deliveries, including 6000 PDPH.

Assuming an incidence of 1 per 10,000 for the composite outcome of cerebral venous thrombosis and non-traumatic subdural hematoma in women who received neuraxial anesthesia and had no PDPH, a 2-tailed test, alpha 5%, and power 80%, our expected study sample would allow us to detect a 15-fold increase (or greater) in the incidence of the composite outcome in women who received neuraxial anesthesia and had PDPH

Results

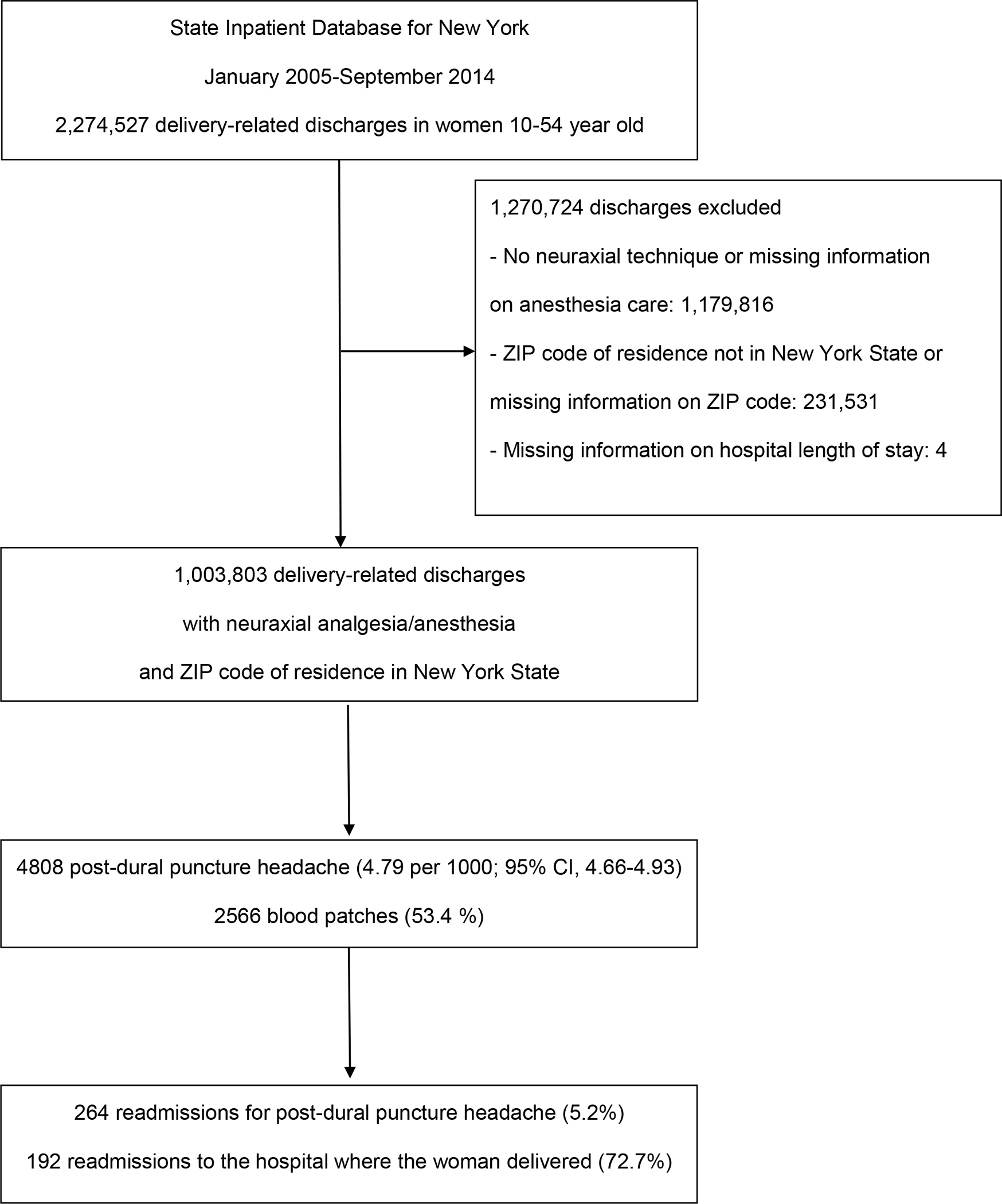

During the study period, 1,003,803 delivery-related discharges of women residing in New York State and who received a neuraxial anesthetics for childbirth were identified (Figure 2). Of them, 4808 women had a diagnosis of PDPH, yielding an incidence of 4.79 per 1000 neuraxial procedures (95% confidence interval (CI), 4.66–4.93).

Figure 2:

Flowchart of the study (CI: confidence interval; ZIP: zone improvement plan)

Among the 4808 PDPH cases, 264 cases (5.5%) were identified during a readmission. The median delay between hospital discharge and readmission for PDPH was 4 days (interquartile range, 2–43). The number of PDPH cases readmitted within 1 week after discharge was 170 (64.4%), between 1 and 6 weeks 28 (10.6%), and more than 6 weeks 66 (25.0%). The proportion of PDPH cases readmitted to the hospital where the woman delivered was 85.9%, 64.3%, and 42.4%, respectively. Among the 4808 PDPH cases, 2566 (53.4%) received epidural blood patch; 2442 blood patch (95.2%) were performed during the initial delivery hospitalization and 124 (4.8%) during a readmission.

Compared with women without PDPH, those with PDPH were more likely to be white or Hispanic, and obese (Table 1). Women with PDPH were also more likely than women without PDPH to have delivered through emergent cesarean sections. Delivery was more likely to have occurred in a hospital not located in a metropolitan division, in a hospital with a Level 1 neonatal care designation, and in a hospital with a lower annual volume of delivery.

Table 1:

Comparison of women with and without post-dural puncture headache (PDPH) who received neuraxial anesthesia during labor and delivery in New York State hospitals, January 2005–September 2014.

| No PDPH (N = 998,995) | PDPH (N = 4808) | P-valuea | SMDb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age (year) | 30 (25–34) | 30 (26–34) | 0.65 | 0.008 |

| Race/ethnicity (missing = 20,346) | < 0.001 | |||

| - White | 543,984 (55.6%) | 2769 (58.4%) | -- | |

| - Black | 140,112 (14.3%) | 550 (11.6%) | −0.08 | |

| - Hispanic | 153,356 (15.7%) | 780 (16.4%) | 0.02 | |

| - Other | 141,260 (14.4%) | 646 (13.6%) | −0.02 | |

| Insurance | 0.48 | |||

| - Medicare and Medicaid | 373,839 (37.4%) | 1840 (38.3%) | -- | |

| - Private insurance | 588,769 (58.9%) | 2804 (58.3%) | −0.01 | |

| - Self-pay | 13,905 (1.4%) | 58 (1.2%) | −0.02 | |

| - Other | 22,482 (2.3%) | 106 (2.2%) | −0.003 | |

| Hospital admission | ||||

| Elective admission (missing = 3165) | 635,027 (63.8%) | 3055 (63.8%) | 0.968 | 0.008 |

| Admission during weekend | 176,109 (17.6%) | 847 (17.6%) | 0.99 | −0.003 |

| Comorbidity and comorbidity indexes | ||||

| Comorbidity index for obstetric patients ≥ 2 | 289,704 (29.0%) | 1439 (29.9%) | 0.161 | 0.02 |

| Charlson comorbidity index ≥ 1 | 52,680 (5.3%) | 280 (5.8%) | 0.095 | 0.023 |

| Obesity | 37,639 (3.8%) | 264 (5.5%) | < 0.001 | 0.076 |

| Pregnancy and delivery | ||||

| Multiple gestation | 31,874 (3.2%) | 174 (3.6%) | 0.100 | 0.02 |

| Induction of labor | 159,026 (15.9%) | 770 (16.0%) | 0.871 | 0.003 |

| Delivery mode | 0.002 | |||

| - Vaginal delivery | 414,876 (41.5%) | 1921 (40.0%) | -- | |

| - Emergent cesarean delivery | 451,133 (45.2%) | 2291 (47.6%) | 0.05 | |

| - Non-emergent cesarean delivery | 132,986 (13.3%) | 596 (12.4%) | −0.03 | |

| Hospital | ||||

| Hospital location (missing = 4639) | < 0.001 | |||

| - Core metropolitan division | 644,373 (64.8%) | 2751 (57.4%) | -- | |

| - Core metropolitan | 307,460 (30.9%) | 1670 (34.8%) | 0.08 | |

| - Core micropolitan | 38,816 (3.9%) | 313 (6.5%) | 0.11 | |

| - Non-core | 3723 (0.4%) | 58 (1.2%) | 0.08 | |

| Teaching hospital (missing = 4639) | 969,624 (97.5%) | 4683 (97.7%) | 0.37 | 0.01 |

| Neonatal level-of-care designation (missing = 169,537) | < 0.001 | |||

| - 1 | 186,395 (22.5%) | 1127 (27.9%) | -- | |

| - 2 | 132,095 (15.9%) | 549 (13.6%) | −0.07 | |

| - 3 | 511,741 (61.6%) | 2359 (58.5%) | −0.06 | |

| Annual volume of delivery | 2570 (1646–4051) | 2444 (1430–3341) | < 0.001 | −0.15 |

| Cesarean delivery rate | 34.7 (31.1–39.9) | 35.1 (31.4–39.9) | < 0.001 | 0.06 |

| Percent admission during a weekend | 20.2 (18.3–21.6) | 20.3 (18.4–21.8) | < 0.001 | 0.04 |

| Percent neuraxial anesthesia in deliveries | 63.9 (35.4–82.7) | 63.9 (38.5–82.4) | 0.688 | 0.02 |

| Percent comorbidity index for obstetric patients ≥ 2 in deliveries | 23.3 (18.5–27.2) | 23.6 (19.0–28.2) | < 0.001 | 0.07 |

| Percent Charlson comorbidity index ≥ 1 in deliveries | 4.2 (2.3–6.8) | 5.0 (2.9–7.4) | < 0.001 | 0.16 |

| Percent minority women in deliveries (missing = 125) | 39.2 (29.5–60.9) | 39.1 (21.3–60.9) | < 0.001 | −0.04 |

| Percent Medicaid/care in deliveries | 35.4 (21.2–56.6) | 36.5 (24.5–57.9) | < 0.001 | 0.08 |

| Intensity of coding | 6.9 (6.0–8.3) | 7.4 (6.3–8.9) | < 0.001 | 0.249 |

Abbreviation: SMD: standardized mean difference

Results are expressed as count (%) or median (IQR).

From Chi-squared test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test with a P value threshold for statistical significance of 0.05.

For the standardized mean difference, a value greater than 0.1 is usually considered to indicate a relevant difference.

Risk of maternal complications

In our study sample, the incidence of the primary composite outcome of cerebral venous thrombosis and non-traumatic subdural hematoma was significantly higher in women with PDPH than in women without PDPH (3.12 versus 0.16 per 1000, respectively; P < 0.001; crude odds ratio (OR), 19.06; 95% CI, 11.23–32.37) (Table 2). The incidence of the 4 secondary outcomes was also significantly higher in women with PDPH than in women without PDPH. After adjustment using the inverse probability of treatment method, the risk of cerebral venous thrombosis and non-traumatic subdural hematoma was still significantly increased in women with PDPH (adjusted OR 18.98; 95% CI, 11.21–32.15) (Table 3). The risk was also increased for the 4 secondary outcomes with an adjusted OR of 39.70 for bacterial meningitis (95% CI, 13.64–115.54), 1.88 for depression (95% CI, 1.37–2.58), 7.66 for headache and migraine (95% CI, 6.49–9.05), and 4.58 for low back pain (95% CI, 3.34–6.29). The E-value was greater than 3 for the 5 complications examined and none a lower limit for the 95% CI including 1. In the 3 sensitivity analyses performed, results were consistent with the main analysis (Supplemental Tables 6 to 9).

Table 2:

Maternal complications in women with and without post-dural puncture headache (PDPH) in the 1,003,803 women who received neuraxial anesthesia during labor and delivery in New York State hospitals, January 2005–September 2014.

| No PDPH (N = 998,995) | PDPH (N = 4808) | P-valuea | Crude OR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Incidence (per 1000; 95% CI) | N | Incidence (per 1000; 95% CI) | |||

| Major neurologic complications | ||||||

| Cerebral venous thrombosis and non-traumatic subdural hematoma | 164 | 0.16 (0.14–0.19) | 15 | 3.12 (1.75–5.14) | < 0.001 | 19.06 (11.23–32.37) |

| Cerebral venous thrombosis | 145 | 0.15 (0.12–0.17) | -b | ≈ 1.66(0.72–3.28) | < 0.001 | 11.48 (5.63–23.41) |

| Non-traumatic subdural hematoma | 19 | 0.02 (0.01–0.03) | - b | ≈ 1.46 (0.59–3.00) | < 0.001 | 76.66 (32.21–182.44) |

| Bacterial meningitis | 21 | 0.02 (0.01–0.03) | - b | ≈ 0.83 (0.23–2.13) | < 0.001 | 39.61 (13.59–115.43) |

| Other complications | ||||||

| Depression | 3732 | 3.74 (3.62–3.86) | 38 | 7.90 (5.60–10.83) | < 0.001 | 2.12 (1.54–2.93) |

| Headache and migraine | 3771 | 3.77 (3.66–3.90) | 149 | 30.99 (26.27–36.29) | < 0.001 | 8.44 (7.15–9.97) |

| Low back pain | 1707 | 1.71 (1.63–1.79) | 40 | 8.32 (5.95–11.31) | < 0.001 | 4.90 (3.58–6.71) |

Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio

From Chi-square test. The threshold for statistical significance is 0.01.

Because of HCUP data use agreement restrictions on small cell size, the number of observed cases and exact proportions are not presented.

Table 3:

Adjusted odds ratio and associated E-value for the risk of maternal complications associated with post-dural puncture headache in the 1,003,803 women who received neuraxial anesthesia during labor and delivery in New York State hospitals, January 2005–September 2014.

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI)a | P-valueb | E-value (lower limit of the 95% CI)c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major neurologic complications | |||

| Cerebral venous thrombosis and non-traumatic subdural hematoma | 18.98 (11.21–32.15) | < 0.001 | 37.43 (21.91) |

| Cerebral venous thrombosis | 11.39 (5.63–23.06) | < 0.001 | 22.27 (10.76) |

| Non-traumatic subdural hematoma | 76.72 (32.25–182.50) | < 0.001 | 152.80 (63.90) |

| Bacterial meningitis | 39.70 (13.64–115.54) | < 0.001 | 78.90 (26.77) |

| Other complications | |||

| Depression | 1.88 (1.37–2.58) | < 0.001 | 3.17 (2.08) |

| Headache and migraine | 7.66 (6.49–9.05) | < 0.001 | 14.80 (12.44) |

| Low back pain | 4.58 (3.34–6.29) | < 0.001 | 8.63 (6.14) |

Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval;

Using the inverse probability of treatment method

From Wald test for the adjusted odds ratio. The threshold for statistical significance is 0.01.

The E-value estimates how strong an unmeasured confounder would need to be to explain away the association observed between PDPH and the complication. The lowest possible E-value is 1 and indicates that no unmeasured confounding is needed to explain away the observed association. The higher the E-value, the stronger the confounder association must be to explain away the observed association.

Readmission for complications

On average, time-to-readmission for the major neurologic complications was shorter than for the other 3 minor complications with a median of 5 days for the composite of cerebral venous thrombosis and non-traumatic subdural hematoma and of 3 days for bacterial meningitis (Table 4). For the major neurologic complications, the neurologic complication was usually the cause for readmission. For the 3 other complications, the complication was the reason for readmission in less than 50% of the cases.

Table 4:

Characteristics of complications identified during a readmission in the 4808 women with post-dural puncture headache in New York State hospitals, January 2005-September 2014. Because of the low number of bacterial meningitis, this outcome is not presented in this table

| Complication identified during a readmissiona | Time between discharge and readmission for a complication (days) | Complications as the cause for readmissionb,c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major neurologic complications | |||

| Cerebral venous thrombosis and non-traumatic subdural hematoma | 11/15 (73%) | 5 (IQR = 3–10; min -max = 2–22) | - d /11 (≈ 73%) |

| Other complications | |||

| Depression | 28/38 (74%) | 65 (IQR = 10–164; min -max = 1–351) | - d /28 (≈ 36%) |

| Headache and migraine | 54/149 (36%) | 18 (IQR = 4–209; min -max = 1–344) | 25/54 (≈ 46%) |

| Low back pain | 19/40 (47%) | 113 (IQR = 4–185; min -max = 2–331) | - d /19 (≈ 26%) |

Results are expressed as count (%) or median (interquartile range; minimum-maximum).

The denominator is the total number of complications, including complications identified during the delivery hospitalizations and during a readmission. The numerator is the number of complications identified during a readmission.

The denominator is the number of complications identified during a readmission

The complication was defined as the reason for readmission it the complication was listed in the first or second ICD-9-CM codes.

Because of HCUP data use agreement restrictions on small cell size, the number of observed cases and exact proportions are not presented.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest study of postpartum complications associated with PDPH following neuraxial anesthesia. We found substantially increased risks of major neurologic complications (cerebral venous thrombosis, subdural hematoma, and bacterial meningitis) in women with PDPH. Our study also suggests that PDPH is associated with significantly elevated risks of postpartum depression, headache, and low back pain.

Risk of major neurologic complications

Cranial subdural hematoma and cortical vein and venous sinus thrombosis have been previously associated with dural puncture.7,8 Subdural hematoma is thought to result from reduced cerebrospinal fluid pressure which may cause rupture of bridge meningeal veins. Venous thrombosis is suggested to result from the cerebral venous dilation associated with decreased intracranial pressure and the hypercoagulability that occurs during pregnancy. Although usually considered as rare complications of PDPH, the incidence of the composite outcome cerebral venous thrombosis and subdural hematoma in the current study was as high as 0.31% or 1 out of 322 PDPH cases. However, there is no available evidence suggesting that restoration of cerebrospinal fluid pressure with epidural blood patch for women with PDPH will necessarily lead to reduced incidence of cerebral venous thrombosis or subdural hematoma. Women with PDPH who experience changes in the characteristics of their headache, vomiting, focal neurologic symptoms, persistent or recurrent headache after epidural blood patch should have prompt central nervous system imaging. This will help identify and distinguish between venous thrombosis and subdural hematoma as their management is substantially different. Venous thrombosis requires anticoagulation which should be avoided in the case of subdural hematoma.

Neuraxial infection was identified as the most common cause of neuraxial injury in obstetric cases in the ASA Closed-Claims Project database between 1980 and 1999; meningitis accounted for 50% of these infectious complications.27 The incidence of meningitis or abscess associated with neuraxial techniques in the recent SCORE project was estimated at 1 per 63,000 neuraxial technique; the incidence of bacterial meningitis in obstetrics associated with spinal techniques in a recent review was estimated at approximately 1 per 39,000 spinals.2,28 In the current study, the overall incidence of bacterial meningitis in women who received neuraxial anesthesia (with or without PDPH) was 1 per 40,000, that is in agreement with previously reported incidences. Importantly, adjusted risk of meningitis was 40-fold increased in women with PDPH. We have to acknowledge that this estimate of the risk of bacterial meningitis should be interpreted cautiously because of the small number of cases in women with PDPH (less than 10). Meningitis associated with neuraxial techniques are caused by the dural puncture and either a direct inoculation of the cerebrospinal fluid due to lack of aseptic technique or a rupture of the blood brain barrier in an infected woman. This reaffirms the need to respect aseptic techniques, especially for neuraxial techniques involving dural puncture, as recently highlighted.29

Risk of minor complications

Four retrospective surveys and case-control studies suggest that PDPH is associated with increased odds of persistent headache and persistent back pain.10–13. Our study, which excluded women with a history of headache or low back pain preceding the delivery hospitalization or present on admission, provides additional evidence for these associations. Mechanisms underlying these observed associations remain unidentified. However, the observed incidence of 3.1% for headache and 0.8% for low back pain in women with PDPH are much lower than those reported in other studies.9–12 Since our study was limited to complications associated with hospitalizations, we probably captured only the most severe forms of headache or back pain which explains our relatively low rates. Most of these complications by themselves would not require hospitalization.

Postpartum depression is of increasing concern in the United States. Its overall prevalence in 2012 was 11.5%.30 It is underdiagnosed and undertreated and is associated with increased maternal morbidity and mortality.31 For instance, maternal suicide is currently the leading cause of direct maternal death occurring within a year of delivery in the United Kingdom.32 Our results suggest a possible association between PDPH and new onset depression. This association may be explained by the intensity of pain after childbirth or a history of acute or chronic pain.14,15 Our findings warrant confirmation based on prospectively collected data and the causal nature of the relationship between PDPH and depression needs to be rigorously evaluated. The 2019 US Preventive Services Task Force Statement recommends interventions, such as counseling, for pregnant and postpartum women at risk for depression.33 If confirmed, our study indicates that PDPH represents a new clinical risk factor for postpartum depression and should be incorporated into screening and intervention programs.

Time-to-readmission for complications

The associations between PDPH and major neurologic complications identified in this study underscore the need for enhanced postpartum surveillance for women with PDPH. The two maternal deaths associated with dural puncture in the 2009–2012 MBRRACE-UK (1 cerebral vein thrombosis and 1 subdural hematoma) led to the recommendation that any woman who develops PDPH “must be notified to her general practitioner and routine follow-up arranged” but did not indicate how long the monitoring should be.9 In our study, the median delay for readmission for cerebral venous thrombosis or subdural hematoma was 5 days, ranging from 2 to 22 days. It suggests that follow-up with women who experience PDPH should be continued until headache is resolved or at least one month after discharge to exclude cerebral venous thrombosis or subdural hematoma. For bacterial meningitis, the median delay for readmission was 3 days but the low number of cases precludes the provision of an accurate follow-up duration.

Time-to-readmission for depression, headache, and low back pain was much longer and up to 4 months for low back pain. However, this interval should not be interpreted as the interval between delivery and the first manifestation of the complications but as the interval between delivery and first readmission. In fact, symptoms of depression, headache, and low back pain are likely to emerge much sooner. It suggests that for women who had PDPH, obstetricians should be notified to make longer term follow-up plan for identifying and treating depression, persistent headache, or low back pain.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the incidence of PDPH in our study (0.4%) was lower than reported in the SCORE project (0.7%).2 A possible explanation is that outpatient or emergency department visits are not captured in the State Inpatient Databases. Another explanation is that only one value for anesthesia type is authorized in State Inpatient Databases data. For example, a woman who received general anesthesia for an intrapartum cesarean delivery but had an analgesic epidural catheter during labor complicated by an accidental dural puncture would have been excluded from our study sample. Last, it is unknown how the coding of PDPH in administrative data is. The lower incidence of PDPH reported in our study might be due to a lower sensitivity of ICD-9-CM coded diagnosis than in the SCORE surveillance system. Second, we have no information about the type (pencil point or cutting edge) or the size (Gauge) of the needles used for the neuraxial procedure, nor do we know if women received a spinal versus epidural (or combined spinal-epidural) anesthesia. We cannot therefore distinguish between accidental dural puncture with an epidural needle from intentional dural puncture with spinal needles, or the use of cutting edge spinal needles versus pencil-point atraumatic spinal needles.

Conclusion

PDPH is associated with substantially increased risks of major neurologic complications and other maternal complications, underscoring the need for early recognition, treatment, and follow-up of women with PDPH.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Question:

Is post-dural puncture headache in obstetrics associated with an increased risk of maternal complications?

Findings:

In women who received neuraxial anesthesia for childbirth in New York State hospitals between 2005 and 2014, post-dural puncture headache was associated with significantly increased postpartum risks of cerebral venous thrombosis, subdural hematoma, bacterial meningitis, depression, persistent headache, and persistent low back pain.

Meaning:

These findings underscore the importance of interventions to reduce obstetric anesthesia-related complications.

Sources of financial support:

Jean Guglielminotti is supported by an R03 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1 R03 HS025787-01).

Glossary of terms

- ASA

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- CI

Confidence Interval

- HCUP

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project

- ICD-9 (10)-CM

International Classification of Diseases, ninth (tenth) revision, Clinical Modification

- IQR

Interquartile Range

- MBRRACE-UK

Mothers and Babies, Reducing Risk through Audits and Confidential Enquiries across the UK

- OR

Odds Ratio

- POA

Present On Admission

- PDPH

Post-Dural Puncture Headache

- SCORE project

Serious COmplication REpository project

- SMD

Standardized Mean Difference

- US

United States

- ZIP

Zone Improvement Plan

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Cheesman K, Brady JE, Flood P, Li G. Epidemiology of anesthesia-related complications in labor and delivery, New York State, 2002–2005. Anesth Analg 2009;109:1174–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Angelo R, Smiley RM, Riley ET, Segal S. Serious complications related to obstetric anesthesia. Anesthesiology 2014;120:1005–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macarthur A. Postpartum headache. In: Chestnut DH, ed. Chestnut’s obstetric anesthesia: Principles and practice. Fifth edition ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders, 2014:713–38. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McQuaid-Hanson E, Hopp S, Radoslovich S, Leffert L, Bateman B. Risk factors and indications for postpartum readmission: A retrospective cohort study (Abstract #O2–03). Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatalogy 48th Annual Meeting. Boston, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies JM, Posner KL, Lee LA, Cheney FW, Domino KB. Liability associated with obstetric anesthesia: A closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology 2009;110:131–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kovacheva VP, Brovman EY, Greenberg P, Song E, Palanisamy A, Urman RD . A contemporary analysis of medicolegal issues in obstetric anesthesia between 2005 and 2015. Anest Analg 2019;128:1199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuypers V, Van de Velde M, Devroe S. Intracranial subdural haematoma following neuraxial anaesthesia in the obstetric population: A literature review with analysis of 56 reported cases. Int J Obstet Anesth 2016;25:58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reynolds F. Neurologic complications of pregnancy and neuraxial anesthesia. In: Chestnut DH, ed. Chestnut’s obstetric anesthesia: Principles and practice. Fifth edition ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders, 2014:739–63. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freedman RL, Lucas DN. MBRRACE-UK: Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care - Implications for anaesthetists. Int J Obstet Anesth 2015;24:161–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Webb CA, Weyker PD, Zhang L, Stanley S, Coyle DT, Tang T, Smiley RM, Flood P. Unintentional dural puncture with a Tuohy needle increases risk of chronic headache. Anesth Analg 2012;115:124–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeskins GD, Moore PA, Cooper GM, Lewis M. Long-term morbidity following dural puncture in an obstetric population. Int J Obstet Anesth 2001;10:17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacArthur C, Lewis M, Knox EG. Accidental dural puncture in obstetric patients and long term symptoms. BMJ 1993;306:883–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ranganathan P, Golfeiz C, Phelps AL, Singh S, Shnol H, Paul N, Attaallah AF, Vallejo MC. Chronic headache and backache are long-term sequelae of unintentional dural puncture in the obstetric population. J Clin Anesth 2015;27:201–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisenach JC, Pan PH, Smiley R, Lavand’homme P, Landau R, Houle TT. Severity of acute pain after childbirth, but not type of delivery, predicts persistent pain and postpartum depression. Pain 2008;140:87–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerrits MM, van Oppen P, van Marwijk HW, Penninx BW, van der Horst HE. Pain and the onset of depressive and anxiety disorders. Pain 2014;155:53–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007;370:1453–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, Harron K, Moher D, Petersen I, Sorensen HT, von Elm E, Langan SM, Committee RW. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS medicine 2015;12:e1001885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuklina EV, Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, Jamieson DJ, Meikle SF, Posner SF, Marchbanks PA. An enhanced method for identifying obstetric deliveries: Implications for estimating maternal morbidity. Matern Child Health J 2008;12:469–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bateman BT, Mhyre JM, Hernandez-Diaz S, Huybrechts KF, Fischer MA, Creanga AA, Callaghan WM, Gagne JJ. Development of a comorbidity index for use in obstetric patients. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122:957–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, Fushimi K, Graham P, Hider P, Januel JM, Sundararajan V. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:676–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guglielminotti J, Deneux-Tharaux C, Wong CA, Li G. Hospital-level factors associated with anesthesia-related adverse events in cesarean deliveries, New York State, 2009–2011. Anesth Analg 2016;122:1947–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song Y, Skinner J, Bynum J, Sutherland J, Wennberg JE, Fisher ES. Regional variations in diagnostic practices. N Engl J Med 2010;363:45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finkelstein A, Gentzkow M, Hull P, Williams H. Adjusting risk adjustment - Accounting for variation in diagnostic intensity. N Engl J Med 2017;376:608–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franklin JM, Eddings W, Austin PC, Stuart EA, Schneeweiss S. Comparing the performance of propensity score methods in healthcare database studies with rare outcomes. Stat Med 2017;36:1946–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schulte PJ, Mascha EJ. Propensity score methods: Theory and practice for anesthesia research. Anesth Analg 2018;127:1074–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: Introducing the E-Value. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:268–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee LA, Posner KL, Domino KB, Caplan RA, Cheney FW. Injuries associated with regional anesthesia in the 1980s and 1990s: A closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology 2004;101:143–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reynolds F. Neurological infections after neuraxial anesthesia. Anesthesiol Clin 2008;26:23–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Practice advisory for the prevention, diagnosis, and management of infectious complications associated with neuraxial techniques: An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on infectious complications associated with neuraxial techniques and the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. Anesthesiology 2017;126:585–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ko JY, Rockhill KM, Tong VT, Morrow B, Farr SL. Trends in postpartum depressive symptoms - 27 States, 2004, 2008, and 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:153–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ko JY, Farr SL, Dietz PM, Robbins CL. Depression and treatment among U.S. pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age, 2005–2009. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:830–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knight M, Nair M, Tuffnell D, Kenyon S, Shakespeare J, Brocklehurst P, Kurinczuk J, on behalf of MBRRACE-UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care - Surveillance of maternal deaths in the UK 2012–14 and lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2009–14 Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33.U. S. Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, Davidson KW, Doubeni CA, Epling JW Jr., Grossman DC, Kemper AR, Kubik M, Landefeld CS, Mangione CM, Silverstein M, Simon MA, Tseng CW, Wong JB. Interventions to prevent perinatal depression: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2019;321:580–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.