Abstract

Background

In 2016, the California Department of Healthcare Services (DHCS) released an “All Plan Letter” (APL 16-014) to its Medicaid managed care plans (MCPs) providing guidance on implementing tobacco-cessation coverage among Medicaid beneficiaries. However, implementation remains poor. We apply the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework to identify barriers and facilitators to fidelity to APL 16-014 across California Medicaid MCPs.

Methods

We assessed fidelity through semi-structured interviews with MCP health educators (N = 24). Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and reviewed to develop initial themes regarding barriers and facilitators to implementation. Initial thematic summaries were discussed and mapped onto EPIS constructs.

Results

The APL (Innovation) was described as lacking clarity and specificity in its guidelines, hindering implementation. Related to the Inner Context, MCPs described the APL as beyond the scope of their resources, pointing to their own lack of educational materials, human resources, and poor technological infrastructure as implementation barriers. In the Outer Context, MCPs identified a lack of incentives for providers and beneficiaries to offer and participate in tobacco-cessation programs, respectively. A lack of communication, educational materials, and training resources between the state and MCPs (missing Bridging Factors) were barriers to preventing MCPs from identifying smoking rates or gauging success of tobacco-cessation efforts. Facilitators included several MCPs collaborating with each other and using external resources to promote tobacco cessation. Additionally, a few MCPs used fidelity monitoring staff as Bridging Factors to facilitate provider training, track providers’ identification of smokers, and follow-up with beneficiaries participating in tobacco-cessation programs.

Conclusions

The release of the evidence-based APL 16-014 by California's DHCS was an important step forward in promoting tobacco-cessation services for Medicaid MCP beneficiaries. Improved communication on implementation in different environments and improved Bridging Factors such as incentives for providers and patients are needed to fully realize policy goals.

Plan Language Summary

In 2016, the California Department of Healthcare Services (DHCS) in California released an “All Plan Letter” (APL 16-014) to its Medicaid managed care plans (MCPs) providing guidance on implementing tobacco-cessation coverage to address tobacco use among Medicaid beneficiaries. We conducted semi-structured interviews with health educators in California Medicaid MCPs to explore the barriers and facilitators to implementing the APL using the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment framework. According to MCPs, barriers included a lack of clarity in the APL guidelines; a lack of resources, including educational materials, infrastructure to identify smokers, and human resources; and a lack of incentives or penalties for providers to provide tobacco-cessation materials to beneficiaries. Facilitators included collaboration between MCPs and state and/or national public health programs. Overall, our findings can provide avenues for improving the implementation of tobacco-cessation services within Medicaid MCPs.

Keywords: Medicaid, tobacco cessation, policy

Tobacco use disproportionately affects low-income populations such as those enrolled in state Medicaid programs, with Medicaid beneficiaries reporting tobacco use at more than twice the rate of the privately insured (Creamer et al., 2019). Tobacco-dependence treatments have a robust evidence-base, resulting in the promotion of Clinical Practice Guidelines by the U.S. Public Health Service over the past 25 years (Fiore, 2000; Fiore et al., 2008; USDHHS, 1996). Recommended evidence-based practices (EBPs) include treatment with one of seven U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved medications (i.e., nicotine-replacement therapies [NRTs], bupropion, and varenicline) (Fiore et al., 2008). The 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) addressed tobacco use among Medicaid beneficiaries by requiring all state Medicaid programs to cover evidence-based tobacco-cessation treatments by 2014.

In response to the ACA's policy, the California Department of Healthcare Services (DHCS) released an All Plan Letter (APL)1 to the California Medicaid (“Medi-Cal”) managed care plans (MCPs) that define evidence-based comprehensive tobacco-cessation services. DHCS's APL guidance included EBPs previously recommended in four tobacco-cessation clinical practice guidelines, with the goal of encouraging MCPs to implement services that complied with ACA requirements and California state-level laws. DHCS's guidance described recommendations for including tobacco-cessation services as new Medi-Cal benefits, documenting members’ smoking status in their medical records, and advising all smokers to quit.

Although fidelity is a widely studied implementation outcome in organizational and community contexts, few studies have investigated fidelity to policy-level initiatives (Crable et al., 2022b; Purtle et al., 2015). Research is needed to better understand how organizations respond to and implement health policies disseminated by federal and state-level entities. Prior work by Crable et al. (2022a) suggests that U.S. federal executive branch influence has a limited impact on state and provider implementation outcomes. Additionally, the decentralized nature of Medicaid benefit administration can promote outer/inner context and EBP misalignment, poor fidelity, and limited adoption of evidence-based benefit policies (Crable et al., 2022b). The emergent subfield of health policy dissemination and implementation provides a useful lens to investigate strategies that promote widespread uptake of health policy, such as the APL, and the factors that impact fidelity implementation of this guidance. Previous research has shown that state Medicaid programs vary in their level of fidelity to the tobacco-cessation provisions stipulated in the ACA, with only 55% of states covering tobacco-cessation treatments as required (McMenamin et al., 2018). In addition, previous research on the implementation of California's tobacco cessation APL demonstrated low levels of fidelity among Medi-Cal MCPs, with only one out of 22 MCPs reporting full implementation (McMenamin et al., 2020). Barriers to and facilitators of fidelity to the APL among Medi-Cal MCPs have not yet been explored.

The aim of this study is to explore the barriers and facilitators to fidelity in implementing an evidence-based policy innovation (i.e., APL) for treating tobacco use and dependence in California Medi-Cal MCPs. Additionally, this research aims to provide recommendations for how California tobacco-cessation stakeholders (Medi-Cal MCPs, California Smokers’ Helpline [the Helpline], and DHCS) can collaborate to improve the implementation and sustainment of tobacco-cessation services and related APL policies within Medi-Cal MCPs.

Methods

Conceptual framework

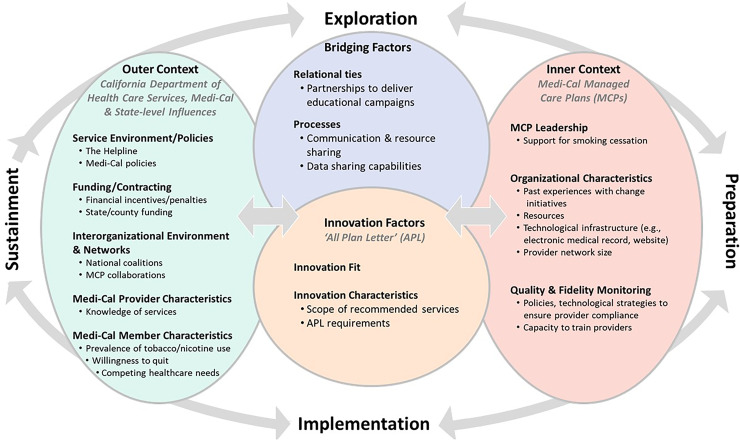

The Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) Framework guided our research to identify and contextualize MCP-identified outer (i.e., California health services environment) and inner (i.e., MCP) context barriers and facilitators to implementing the APL within Medi-Cal MCPs (Figure 1; Aarons et al., 2011). The EPIS framework describes four distinct, non-linear phases by which implementation activities unfold. During Exploration, DHCS policymakers examine the necessity for changing Medi-Cal policy to improve access to tobacco-cessation EBPs and to comply with ACA requirements. In Preparation, Medi-Cal MCP leaders prepare to adopt the new EBPs stipulated by DHCS guidance. During Implementation and Sustainment phases, MCPs begin to implement and identify ways to maintain coverage of EBPs and policy guidance. Throughout these phases, implementation activities are influenced by Inner Context (e.g., MCP organizational factors, leadership priorities, past experiences with change initiatives, quality and fidelity monitoring processes) and Outer Context factors (e.g., Medi-Cal program, Medi-Cal contracted providers, service environment, inter-organizational environment, Medi-Cal beneficiaries) that may act as barriers and facilitators to implementing the APL (Innovation). Finally, Bridging Factors describe the relational ties, formal arrangements, and processes that link Inner and Outer Contexts to support the implementation and sustainment of policy innovation and describe the types of supports necessary for achieving fidelity to APL guidelines (Lengnick-Hall et al., 2021; Moullin et al., 2019).

Figure 1.

Application of the EPIS framework to MCP implementation of tobacco-cessation APL.

Abbreviations: APL = all plan letter; MCPs = Medi-Cal managed care plans; EPIS = Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment

Data collection

In California and across the United States, the vast majority (> 80%) of Medicaid beneficiaries receive their services through MCPs (KFF, 2020). All 25 MCPs that contracted with Medi-Cal during 2018 were invited to participate in the study. MCP health educators were identified as having primary responsibility for implementing the APL and were recruited to participate in this study through the DHCS health educator listserv. Data were collected in two phases between September 2018 and February 2019. First, health educators were sent an online survey hosted by KeySurvey that inquired about the MCP implementation of each of the APL items. Follow-up one-hour virtual interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide that clarified responses to the survey, inquired about barriers and facilitators of APL implementation, and requested feedback related to APL requirements. Interviews were conducted by three female researchers: one with a doctorate in health policy (SM), another who previously worked at DHCS, and a policy analyst (SY). Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Key stakeholders from 24 MCPs (representing 96% of members in Medi-Cal MCPs) participated in the study. One MCP administers tobacco-cessation benefits for two other MCPs; therefore, the sample size is 22 MCPs. The UC San Diego Human Research Protections Program exempted this project as non-human-subjects research.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was conducted by the first author (an anthropologist), with frequent input from the rest of the research team, including implementation scientists, policy experts, and qualitative researchers. Interview data were reviewed exhaustively to develop themes (e.g., lack of resources, engagement, communication); saturation was reached after reviewing half of the interviews (11 MCPs). Transcripts were coded and summaries of each theme were developed. Initial thematic summaries were discussed as a group, who then determined that barrier and facilitator themes naturally aligned with Inner and Outer Contexts, Bridging and Innovation Factors construct language from EPIS. Mapping themes to EPIS constructs also promote transferability of the findings using framing from a seminal model in the health policy dissemination and implementation science field. For example, barriers and facilitators related to resource capacity and infrastructure were relevant to the MCP's Inner Contexts regarding their organizational staffing and quality and fidelity monitoring processes. Communication and partnership-related barriers spoke to the need for enhanced linkages, or Bridging Factors, between MCP's Inner Context and the broader Medi-Cal service system Outer Context. Themes describe lessons from the Implementation phase and recommendations suggest opportunities to support APL Sustainment.

Results

During the Implementation phase, MCP representatives described barriers as stemming from Innovation Factors, Inner and Outer Contexts, and the absence of Bridging Factors to align Inner MCP and Outer Medi-Cal, provider, and patient Contexts (Table 1). MCP representatives described facilitators within the Inner and Outer Contexts. Participants also described recommendations for Inner and Outer Context activities and Bridging Factors that would support APL Sustainment activities.

Table 1.

Summary of barriers and facilitators by exploration, preparation, implementation, sustainment framework construct.

| Barrier | Facilitator | |

|---|---|---|

|

Innovation Factors:

All Plan Letter (APL) |

|

|

| Inner Context: Medi-Cal Managed Care Plans (MCPs) |

|

|

| Outer Context: California Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), Medi-Cal, and Other State-level Influences |

|

|

| Bridging Factors: Supportive Processes and Relationships that Link Inner and Outer Contexts |

|

• Non-physician tobacco champions that served as intermediaries

between MCP and providers •

Recommendations:

|

Barriers

APL policy guideline innovation factors

Throughout the Implementation phase, MCPs said a lack of specificity about the APL policy innovation created confusion among MCP leaders about how to promote APL fidelity within their organization. Specifically, health educators said that the APL lacked clarity regarding compliance with APL requirements and did not provide sufficient direction regarding the implementation of the policy. For example, the APL states that MCPs “must ensure that their contracted providers identify and track all tobacco use.” Health educators questioned what “ensure” means in this context: Is it enough to include these requirements as part of the provider contract, or are the MCPs also required to conduct an audit to “ensure” that providers comply with their contract?

Stakeholders also struggled to interpret and implement the APL given its broad scope of services. MCPs said that APL services were beyond their reach: “[We need the state/APL] to give us the answers—how do we do all this?—here's your APL, […], but give us some more ideas on how to implement this, especially since we are not at Kaiser Permanente [KP].” Many MCPs made similar comparisons to KP, highlighting that they lacked a similar large or coordinated network with the capacity to implement the APL given its broad scope.

MCP organizational inner context

The difficulties of implementing an APL with a scope that stretches beyond MCPs’ resources arise in part from MCPs’ organizational characteristics and staffing, including MCPs’ own lack of educational materials, infrastructure, and human resources. Educational materials required MCP staff time to develop or to identify existing available resources. MCPs described the need to have educational resources available in multiple languages and designed in ways that address cultural and generational barriers. Health educators also said that MCPs lacked the capacity to conduct APL-related trainings for providers or to deliver group tobacco-cessation counseling for MCP members. This situation left MCPs reliant on available training and group counseling resources from other community-based organizations, which were limited in smaller, more rural counties (see Outer Context).

Health educators also pointed to MCPs’ own infrastructural shortcomings as barriers to implementation. For example, poorly designed websites made it difficult for plan members to access information (e.g., tobacco-cessation materials). Additionally, technological limitations like not having a standard electronic medical records (EMR) system across all MCP-contracted providers complicated the implementation process: “If we had a closed system like [KP] where everyone is using the same [EMR], then it would be easy to enforce [identification of tobacco users], but we, as a health plan [are] not offering a medical record system, and everyone is using their own respective system.” Additionally, MCPs lack internal policies and mechanisms to ensure that providers follow guidelines. The absence of organizational strategies and infrastructure for quality and fidelity monitoring was compounded by lack of support from MCP leadership. One health educator also described a lack of political will among MCP management to implement the APL:

It has not been an interest, or has not been taken seriously, or there are other priorities […] I came into the health plan being a super tobacco control advocate, and [despite] the fact that it is the number one preventable disease, etc., no one is really willing to tap into it. When I start bringing up tobacco, [leadership] chuckle. It is weird that the thing I am the most serious about, they take me the least serious about.

MCPs described that implementing tobacco-cessation guidelines competed with other priorities pushed by the state (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, the opioid epidemic, etc.), and addressing all these priorities takes time. One MCP representative explained:

I’m going to place some blame back on the state for the fact that there is so much coming at the [MCPs] all of the time […] There is really [sic] so much we can take on and do effectively given the fact that there are so many changes.

MCPs explained that the resources required to implement the APL exceeded the scope of their existing resources. For example, MCPs with a large network of Medi-Cal providers described being unable to collect data on APL implementation and provide timely feedback to their providers: “The APL is not super realistic. We have an open system—I don’t know of any MCP that has the resources to monitor the providers’ assessments.” The lack of centralized technological infrastructure exacerbates problems of human resource limitations: “It's very time consuming, especially all of the other reporting we have to do. Doesn’t mean it can’t be done—it certainly can—it’s just availability and ease of retrieving the data I would say is one of the main [barriers].”

State DHCS, provider, and member outer context

MCP health educators described Outer Context barriers related to MCP-contracted providers and plan members. MCPs mentioned that DHCS did not financially incentivize provider compliance to the APL guideline, which hindered providers’ willingness to implement tobacco-cessation EBPs. One MCP explained:

We don’t have any leverage over the providers to do anything around this; providers don’t get penalized. […] It’s not a P4P [pay for performance]; there is nothing to incentivize our providers to do anything around this.

As a result, tobacco billing codes are infrequently used by providers, and when they are, it is as second or later diagnostic codes. One health educator pointed to the effect of provider individual characteristics, explaining that it ultimately “depends on how passionate the provider is about tobacco cessation.” Variation in providers’ passion for tobacco-cessation was thought to contribute to the lack of claims regarding counseling utilization: “Even if [providers] are submitting the encounter, but they are not coding correctly—that’s also going to change your numbers. […] Maybe [members are] being diagnosed, but [providers are] probably not billing the CPT [Current Procedural Terminology] codes [for delivery of counseling].”

MCP representatives characterized members as lacking interest in abstaining from smoking and having limited engagement in tobacco-cessation programs: “I think the APL did a good job of standardizing the benefits and making access to counseling and NRT widely available—I don’t think those are barriers anymore; I think the barriers are members’ willingness to quit.” MCPs highlighted that current smoking rates are lower than in the 1990s, with remaining smokers either being severely addicted or occasional smokers,2 who see less of a need to quit. This made it difficult for MCPs to earmark their limited resources for tobacco-cessation activities: “From a health plan perspective, it’s about where you put your dollars to pay a consultant to run a class and then no one shows up.”

Additionally, MCPs described how a lack of community-based services available to members serves as a barrier to APL implementation. One MCP referenced the discontinuation of county funding that had previously supported tobacco-cessation classes, which would have facilitated APL implementation by offering resources to MCP members. Another MCP described how “the Health Department is looking to provide classes within the community. There’s not a lot of funding for group classes, even though previous classes were successful; however, funding ran out.” The absence of Outer Context-supported tobacco-cessation classes and other resources hindered MCP members’ access to APL-aligned services.

Bridging factors

MCPs described the absence of relational ties, such as meaningful DHCS-MCP partnerships, and communication or data sharing processes with DHCS and MCP-contracted providers as substantial barriers to fidelity APL implementation and sustainment.

Health educators said there was a lack of communication between the state and MCPs due to the absence of an intermediary capable of resolving confusion around APL requirements. MCPs indicated that while APL-related resources may be featured on the DHCS website, they can be unclear, inconsistent, or incomplete. Additionally, health educators identified cultural and linguistic communication barriers related to existing resources like the Helpline: “We have an Indigenous population here in [county]; it would be nice to have more materials that are more relevant for this particular population.” MCPs wanted DHCS to take the lead in providing new resources to communicate with members related to the APL: “We don’t have a lot of resources when it comes to communication, materials, and marketing, and so having [DHCS] help us with that lead would be really beneficial—even just setting up the template, and we could produce it.” This participant suggested that such a resource could then be branded and distributed by MCPs.

Due to the structure of provider networks, communication between MCP staff and MCP-contracted providers was also identified as a major barrier. Several health educators contrasted their MCPs with integrated plans like KP, believing that KP’s health educators have an easier time communicating with contracted providers. Health educators described a power dynamic that made it difficult for them to provide medical advice about members to MCP-contracted providers:

The main barrier is the communication between us and the providers … For example, we get a member who has been on [the] NRT patch for years or they are on a long dosage, and we try to talk to the doctor’s office, there is miscommunication there—we don’t want to tell the doctor what to do, because we are not clinical, but yet sometimes the support from the provider[s] […] is not where it should be.

MCPs cited the need for an external intermediary who understood DHCS’s APL priorities and could support MCPs’ and providers’ fidelity to APL by offering re-training and follow-up workshops. Due to MCPs’ limited funding to contract an intermediary to deliver trainings, some MCPs aimed to enhance passive communication processes with contracted providers by posting materials and reminders about tobacco cessation on their provider-facing websites and newsletters.

MCPs also described the absence of a data-sharing process between plan staff and contracted providers as a barrier to evaluating provider compliance and identifying members with tobacco-use disorders to engage them in care. Given the lack of an integrated EMR across their provider network, MCPs receive member claims data in different formats from providers. MCPs do not have the bandwidth to combine the varied types of data they receive to monitor provider compliance or identify members who smoke. Due to the lack of a formal and efficient process for identifying members who might benefit from APL services, MCPs draw on diagnostic and counseling codes and pharmacy data, which are problematic due to inconsistencies in provider reporting. Some data on MCP members who smoke are derived via member responses to tobacco-cessation targeted mailings, but these data only identify members seeking assistance to quit smoking.

Finally, health educators pointed to patient-provider communication concerns and historical hesitancy for patients to discuss tobacco use with their providers. Without formal and efficient processes for identifying members who smoke, MCPs felt unable to implement APL guidelines with fidelity and effectively serve their members.

Facilitators

Inner context

Facilitators of APL implementation fidelity included resources for internal MCP programs, such as free group classes or internal telephone counseling. One MCP described notification systems that included robocalling members about tobacco-cessation programs available to them, as well as a forthcoming texting program. However, not all MCPs had the resources to support classes and counseling services.

Some MCPs were able to improve APL quality/fidelity monitoring by having annual in-service trainings and re-trainings that were informed by chart audits. These MCPs conducted facility site reviews and audits to ensure provider compliance with regulations. MCPs varied in how often they conducted these (e.g., annually, every three years, or never). A few MCPs have quality improvement staff who facilitated new provider orientation, tracked providers’ identification of smokers, and conducted follow-up. They also provided re-training workshops, webinars, in-person office visits, and care packets with resources that allowed for corrective action in response to monitoring and evaluation of data. They also used newsletters and flyers to communicate with providers and patients and made web referrals to the Helpline available. Some MCPs were able to develop direct communication processes with their members and reported achieving greater APL implementation fidelity. Examples of successful communication processes between MCPs and members included MCPs assembling mailing lists informed by chart codes and using them to send targeted packages, such as one for smokers using pharmacotherapy and a different one for those not on pharmacotherapy. They also developed pamphlets and flyers specifically focusing on e-cigarettes/vaping for distribution among adolescents.

Outer context

MCPs described their interorganizational environment and networks as Outer Context facilitators. For example, MCPs collaborated with state public health programs, universities, telephone counseling, and hospital-based programs to expand their existing tobacco-cessation services, including health educators and outreach workers. State-wide resources were described as particularly beneficial, such as the Helpline, which is open after hours and provides services in multiple languages. Separate incentive programs for members were also seen as valuable, such as the pilot program providing incentives to call the Helpline:

When the NRT incentive—$25 incentives—sent to members via the [Helpline] was dropped, the number of calls to the [Helpline] from [MCP name] dropped by half. If there is some kind of incentive for our members, that would be another way to reach out to our members to reach out to the providers to obtain medications.

Some MCPs collaborated with other MCPs in their region, taking turns offering counseling in adjacent counties and in multiple languages. One health educator described, “The other thing we do is we work with the other health plans in [county]—and we take turns offering group classes, and [we offer] them in English, Spanish, Cantonese, and Mandarin. […] So we’ve developed a curricula that we all use—we standardized the curricula.” However, such MCP collaborations were rare.

Bridging factors

In response to challenges identifying MCP members with documented smoking or tobacco use, one MCP hired non-physician tobacco champions to serve as intermediaries between the MCP and contracted providers. One MCP noted that “[The champions’] jobs are to be in the facilities and work with physicians—they are the tobacco experts. They show [physicians] how to use the system to learn how to make referrals. They are on the ground to ensure physicians understand how to report and refer.”

Suggestions for improvement

Health educators were asked to propose recommendations to improve tobacco-cessation services and thus APL implementation. Due to acknowledgment of MCPs’ limited resources, there were few recommendations related to the Inner Context, with one MCP representative suggesting a shift from mail- to text message-based campaigns to reach members without delay. MCPs also suggested that they target their APL-related communications to members in November and December to highlight the potential to set New Year’s resolutions. Another MCP described that as smoking prevalence decreases, they hope to tailor their approach more:

Segmenting the population is important for us to sort out. […] How are we addressing individuals who don’t come in and access services? Why aren’t certain communities accessing services similar to the white male population? We need to learn how to address it. We are making movement in that area by creating culturally competent resources.

Other recommendations focused on the need to expand health education efforts from DHCS or other Outer Context organizations. MCPs suggested that Outer Context organizations develop and provide educational posters and reading materials for clinic waiting rooms. They also advocated for DHCS to offer financial incentives to Medicaid beneficiaries to promote their engagement in APL-related services. In addition, health educators also pointed to structural interventions (e.g., transportation, food security, and housing) that could help members quit smoking and remain smoke-free.

Most MCPs’ recommendations constituted Bridging Factors that would help promote APL policy guideline fidelity by aligning Inner and Outer Contexts. A few health educators requested information regarding other MCPs’ practices and programs to learn from each other. Health educators suggested that MCPs collaborate with DHCS to educate providers, motivating them to assess members, educate them, and bill for related services. One health educator suggested a train-the-trainers model: “We [would] work with our provider network staff, and they go out and meet with providers, and we give them a health education kit of information to share, and tobacco cessation programs [would be] part of that kit.” Another MCP described plans to create partnerships with hospitals to deliver group counseling for smoking cessation. A final recommendation was to establish an EMR system to share information between Medi-Cal membership lists and the Helpline—to facilitate identifying which members are accessing services and quitting.

Discussion

MCPs described several barriers and facilitators to fidelity to APL policy guidelines. APL language represented a substantial barrier to MCPs clearly understanding what was expected of them and their contracted providers. While the APL is a novel policy to promote tobacco-cessation in California, MCP representatives did not identify any facilitators related to the policy language or developers to aid their compliance with these guidelines. It is unclear whether MCPs are the appropriate level to implement APL components related to provider behavior. Yet due to the structure of existing contracting relationships, wherein DHCS contracts directly with MCPs who contract directly with providers, the APL is one of few mechanisms that DHCS has to potentially change provider behavior. Prior research on Medi-Cal implementation efforts suggests that providers are responsive to contract requirements, but additional provider-level implementation strategies are needed to ensure fidelity to complex policies changes (Crable et al., 2022b).

Barriers to fidelity were spread across Inner MCP (e.g., limited resources and infrastructure to deliver educational materials, low political will of MCP leaders to support implementation efforts due to competing demands, and limited quality/fidelity monitoring processes) and Outer state contexts (e.g., absence of financial incentives for providers and members, dearth of county funding to support APL-related initiatives, and limited interest among providers and members to engage in tobacco-cessation activities). Despite these challenges, some facilitators did exist to support MCPs achieving limited fidelity to APL guidelines. Internally, a few MCPs benefited from an integrated system, and many drew on their past experiences with tobacco-cessation activities to support APL implementation. MCPs also organized and mailed educational outreach to members to engage them in tobacco-cessation activities. Within the Outer Context, interorganizational network collaborations between county tobacco control programs, MCPs, and other providers facilitated APL implementation, and the Helpline provided after-hours and multilingual services to MCP beneficiaries seeking tobacco-cessation services.

Bridging Factors play a critical role in spanning the Inner and Outer Contexts to support implementation efforts (Lengnick-Hall et al., 2021; Moullin et al., 2019). In this study, we found that the absence of Bridging Factors represented substantial barriers to APL fidelity. MCPs highlighted the need for strengthened relational ties between MCPs and DHCS to improve APL information and knowledge sharing, training on APL services, and improved implementation of APL services. Prior research has highlighted the importance of strong relational ties to support policy implementation; however, there is a dearth of evidence for how and when to employ such collaborative strategies (Bunger et al., 2020; Selden et al., 2006). The field of policy dissemination and implementation research should further investigate the nature and impact of relational ties that target policy-specific knowledge exchange between Outer Context agencies and Inner Context stakeholders (Crable et al., 2022b). Bridging Factors that promote communication and collaboration processes between MCPs and providers were also needed to promote APL fidelity. The absence of technological processes to identify members with tobacco-use behavior was a substantial barrier to MCPs implementing APL guidelines. Such data-sharing processes are critical to reaching target populations and conducting meaningful implementation monitoring and feedback (Hysong et al., 2011; Lengnick-Hall et al., 2020; Perry et al., 2019).

Although Bridging Factors are distinct from implementation strategies (Lengnick-Hall et al., 2021), MCPs that can develop implementation strategies to “change record systems” that create compatible or uniform EHRs and facilitate provider-plan communication may achieve improved outcomes for APL and other DHCS initiatives (Powell et al., 2015). However, fidelity to delivering APL services may still be hindered by variation in providers’ passion for and willingness to deliver smoking-cessation EBPs. A large cross-sectional study revealed that healthcare providers across specialties fail to address smoking cessation with patients due to limited visit time, sensitivity or stigma around smoking behavior, and lack of training around smoking-cessation (Meijer et al., 2019). Our study amplifies prior calls to enhance provider training in smoking-cessation coaching EBPs. Strengthened relational ties between MCPs/DHCS, community-based organizations, and other intermediaries that are knowledgeable about tobacco-cessation EBPs may fulfill provider training needs.

Limitations

First, our primary respondents were health educators and other staff responsible for implementing the APL. Without engaging MCP leadership—those able to allocate additional resources to better support implementation fidelity—we were unable to fully assess how leadership priorities and organizational culture contributed to identified implementation problems. Second, our interview guide was not designed to exhaustively cover EPIS constructs.

Future directions

DHCS's release of an APL defining a comprehensive tobacco-cessation benefit in Medi-Cal MCPs was an innovative component of California's progressive and successful tobacco-control strategy. While these findings point to areas where improvements may be made, the APL itself represents a tremendous advance in tobacco control. That said, there were several areas identified by health educators where the APL fell short. Recommendations related to the improvement of the APL and Bridging Factors to improve the fit between the APL and the Outer and Inner Contexts are discussed below.

California's smoking cessation APL was issued to formally describe expectations for providing comprehensive tobacco-cessation services and to provide guidance regarding the implementation of the ACA's tobacco-cessation benefit. The APL was innovative in that the recommendations were evidence-based, drawing from clinical practice guidelines (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2008; Fiore et al., 2008; USPSTF, 2013, 2015). Other state Medicaid programs would benefit from issuing an APL to provide guidance to contracting MCPs to formally define comprehensive tobacco-cessation benefits. Yet, MCPs in California report needing additional guidance regarding how to implement specific components of the APL. Whereas formulary guidance related to drug coverage is straightforward, it is less clear how MCPs without integrated provider networks can implement some of the requirements related to tracking provider behavior. MCPs repeatedly contrasted their resources and organizational structure with KP, noting without a KP-like integrated EHR or shared culture between the health plan and providers, they would be unable to identify eligible members or implement the APL's large scope of services with fidelity (Maeda et al., 2014; Strandberg-Larsen et al., 2010).

In our study, health educators expressed frustration at the lack of follow-up from DHCS to audit the specific components and measure progress towards full implementation. DHCS requirements for MCPs to report on tobacco-cessation policies would signal to MCP leadership that tobacco cessation is an important part of the care they provide. MCP leadership has the ability to allocate additional resources to fully implement the APL, yet fails to do so often due to competing priorities and a lack of monitoring and enforcement by DHCS. In addition, guidance for MCPs without integrated provider networks or without sophisticated technology infrastructure for how to implement APL components related to monitoring and evaluation of providers and tobacco users should be provided by DHCS.

MCP representatives also indicated that they would like additional resources from DHCS such as educational materials in multiple languages. Coordination between DHCS and the California Tobacco Control Program (CTCP) could be key to leveraging and disseminating existing educational resources developed by the CTCP to MCPs. Additional coordination between DHCS and the Helpline is essential to maximizing the utility of the Helpline by creating a system to provide feedback on patient progress to the MCPs. Previous research has demonstrated that incentive programs can increase rates of tobacco users’ quit attempts and sustained cessation (Anderson et al., 2018; Notley et al., 2019). MCP health educators indicated that they had more success with tobacco-cessation efforts during previous pilot programs offering incentives for cessation (Tong et al., 2018). MCPs also commented on the need for monetary incentives that encourage providers to conduct APL services. Financial strategies have demonstrated mixed results for incentivizing providers to implement EBPs; they may be insufficient to offset historically low Medicaid reimbursement rates and high administrative burdens of adopting new services (Andrews et al., 2015; Flodgren et al., 2011). Future research should investigate the utility of financial incentives among Medicaid providers and beneficiaries.

Health educators at MCPs clearly expressed that improved Bridging Factors are needed to increase the implementation of the APL. For example, one theme that emerged was the need for partners to deliver educational campaigns to members and trainings for providers. In addition, pathways for resource sharing were desired. While providers may contract with multiple MCPs, efficiency may be gained by creating a system where providers can directly report data on member tobacco use and cessation efforts into a centralized database accessible by both DHCS and the MCPs. This reduces the inefficiency of MCPs collecting data from multiple providers, who in turn may contract with multiple MCPs.

This study adds to the growing subfield of health policy dissemination and implementation science research. Our qualitative analysis provides insights into critical Inner and Outer Context factors that can hinder or promote the translation of state policy guidance into organizational policy and practice. This is critical given the dearth of policy-focused dissemination and implementation science, as well as a limited understanding of how Outer Context factors influence implementation efforts (McHugh et al., 2020). Future health policy research is needed to further explore and quantify the degree to which contextual barriers and facilitators impact implementation success and sustainment over time (Allen et al., 2020). Additionally, research should test the utility of implementation strategies that serve as Bridging Factors to enhance communication between state- and organizational policymakers and practitioners (Lengnick-Hall et al., 2021).

Conclusion

The release of the evidence-based tobacco-cessation APL by California's DHCS was an important step forward in promoting tobacco-cessation services for Medi-Cal managed-care members. However, fidelity implementation and sustainment of new services are hindered by diverse MCP and state contextual factors. Clearer policy guidance on APL requirements; enhanced relational ties; and data sharing processes between MCPs, DHCS, and providers are needed to fully realize the benefit of this policy.

In 2014, a policy letter was issued (14-006). An updated version was issued (APL 16-014) in 2016, which extended the implementation deadline for select requirements and provided additional guidance. We are specifically investigating implementation of APL 16-014.

Smokers who smoke some days, but not every day (USPHSOSG, 2020).

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (grant no. 28IR-0056).

ORCID iD: Melina A. Economou https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2752-3907

Sara B. McMenamin https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3235-6936

References

- Aarons G. A., Hurlburt M., Horwitz S. M. (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(1), 4–23. 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen P., Pilar M., Walsh-Bailey C., Hooley C., Mazzucca S., Lewis C. C., Mettert K. D., Dorsey C. N., Purtle J., Kepper M. M., Baumann A. A., Brownson R. C. (2020). Quantitative measures of health policy implementation determinants and outcomes: A systematic review. Implementation Science, 15(1), 1–17. 10.1186/s13012-020-01007-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics (2008). Bright futures: Guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents (3rd ed.). American Academy of Pediatrics. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C. M., Cummins S. E., Kohatsu N. D., Gamst A. C., Zhu S. H. (2018). Incentives and patches for Medicaid smokers: An RCT. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 55(6), S138–S147. 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews C., Abraham A., Grogan C. M., Pollack H. A., Bersamira C., Humphreys K., Friedmann P. (2015). Despite resources from the ACA, most states do little to help addiction treatment programs implement health care reform. Health Affairs, 34(5), 828–835. https://doi.org/10.1377%2Fhlthaff.2014.1330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunger A. C., Chuang E., Girth A., Lancaster K. E., Gadel F., Himmeger M., Saldana L., Powell B. J., Aarons G. A. (2020). Establishing cross-systems collaborations for implementation: Protocol for longitudinal mixed methods study. Implementation Science, 15(55), 1–14. 10.1186/s13012-020-01016-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crable E., Jones D. K., Walley A. Y., Hicks J. M., Benintendi A., Drainoni M. L. (2022a). How do Medicaid agencies improve substance use disorder benefits? Lessons from three states’ 1115 waiver experiences. Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law, 9716740. 10.1215/03616878-9716740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crable E. L., Benintendi A., Jones D. K., Walley A. Y., Hicks J. M., Drainoni M. L. (2022b). Translating Medicaid policy into practice: Policy implementation strategies from three US states’ experiences enhancing substance use disorder treatment. Implementation Science, 17(1), 1–14. 10.1186/s13012-021-01182-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creamer M. R., Wang T. W., Babb S., Cullen K. A., Day H., Willis G., Ahmed J., Neff L. (2019). Tobacco product use and cessation indicators among adults—the United States, 2018. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(45), 1013. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6845a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore M. C. (2000). Treating tobacco use and dependence (No. 18). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore M. C., Jaén C. R., Baker T. B., Bailey W. C., Benowitz N. L., Curry S. J., Dorfman S. F., Froelicher E. S., Goldstein M. G., Healton C. G., Henderson P. N., Heyman R. B., Koh H. K., Kottke T. E., Lando H. A., Mecklenburg R. E., Mermelstein R. J., Dolan Mulllen P., Orleans C. T., et al. (2008). Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Flodgren G., Eccles M. P., Shepperd S., Scott A., Parmelli E., Beyer F. R. (2011). An overview of reviews evaluating the effectiveness of financial incentives in changing healthcare professional behaviours and patient outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (7), 1–88. 10.1002/14651858.cd009255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hysong S. J., Esquivel A., Sittig D. F., Paul L. A., Espadas D., Singh S., Singh H. (2011). Towards successful coordination of electronic health record based-referrals: A qualitative analysis. Implementation Science, 6(1), 1–12. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation [KFF] (2020). Total Medicaid MCO enrollment as of July 1, 2018. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-medicaid-mco-enrollment/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D.

- Lengnick-Hall R., Stadnick N. A., Dickson K. S., Moullin J. C., Aarons G. A. (2021). Forms and functions of bridging factors: Specifying the dynamic links between outer and inner contexts during implementation and sustainment. Implementation Science, 16(1), 1–13. 10.1186/s13012-021-01099-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengnick-Hall R., Willging C., Hurlburt M., Fenwick K., Aarons G. A. (2020). Contracting as a bridging factor linking outer and inner contexts during EBP implementation and sustainment: A prospective study across multiple U.S. public sector service systems. Implementation Science, 15(1), 1–16. 10.1186/s13012-020-00999-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda J. L., Lee K. M., Horberg M. (2014). Comparative health systems research among Kaiser Permanente and other integrated delivery systems: A systematic literature review. The Permanente Journal, 18(3), 66–77. 10.7812/TPP/13-159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh S., Dorsey C. N., Mettert K., Purtle J., Bruns E., Lewis C. C. (2020). Measures of outer setting constructs for implementation research: A systematic review and analysis of psychometric quality. Implementation Research and Practice, 1, 2633489520940022. 10.1177/2633489520940022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMenamin S. B., Yoeun S. W., Halpin H. A. (2018). Affordable Care Act impact on Medicaid coverage of tobacco-cessation treatments. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 54(4), 479–485. 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMenamin S. B., Yoeun S. W., Wellman J. P., Zhu S. H. (2020). Implementation of a comprehensive tobacco-cessation policy in Medicaid managed care plans in California. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 59(4), 593–596. 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer E., Van der Kleij R. M. J. J., Chavannes N. H. (2019). Facilitating smoking cessation in patients who smoke: A large-scale cross-sectional comparison of fourteen groups of healthcare providers. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 1–16. 10.1186/s12913-019-4527-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moullin J. C., Dickson K. S., Stadnick N. A., Rabin B., Aarons G. A. (2019). Systematic review of the exploration, preparation, implementation, sustainment (EPIS) framework. Implementation Science, 14(1), 1–16. 10.1186/s13012-018-0842-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notley C., Gentry S., Livingstone-Banks J., Bauld L., Perera R., Hartmann-Boyce J. (2019). Incentives for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (7), 1–20. 10.1002/14651858.cd004307.pub6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry C. K., Damschroder L. J., Hemler J. R., Woodson T. T., Ono S. S., Cohen D. J. (2019). Specifying and comparing implementation strategies across seven large implementation interventions: A practical application of theory. Implementation Science, 14(1), 32. 10.1186/s13012-019-0876-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell B. J., Waltz T. J., Chinman M. J., Damschroder L. J., Smith J. L., Matthieu M. M., Proctor E. K., Kirchner J. E. (2015). A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project. Implementation Science, 10(1), 1–14. 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purtle J., Peters R., Brownson R. C. (2015). A review of policy dissemination and implementation research funded by the national institutes of health, 2007–2014. Implementation Science, 11(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186%2Fs13012-015-0367-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selden S. C., Sowa J. E., Sandfort J. (2006). The impact of nonprofit collaboration in early child care and education on management and program outcomes. Public Administration Review, 66(3), 412–425. 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00598.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strandberg-Larsen M., Schiøtz M. L., Silver J. D., Frølich A., Andersen J. S., Graetz I., Reed M., Bellows J., Krasnik A., Rundall T., Hsu J. (2010). Is the Kaiser Permanente model superior in terms of clinical integration?: A comparative study of Kaiser Permanente, Northern California and the Danish healthcare system. BMC Health Services Research, 10(1), 1–13. 10.1186/1472-6963-10-91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong E. K., Stewart S. L., Schillinger D., Vijayaraghavan M., Dove M. S., Epperson A. E., Vela C., Kratochvil S., Anderson C. M., Kirby C. A., Zhu S., Safier J., Sloss G., Kohatsu N. D. (2018). The Medi-Cal incentives to quit smoking project: Impact of statewide outreach through health channels. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 55(6), S159–S169. 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS] (1996). Smoking cessation, clinical practice guideline, No. 18. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- United States Preventive Services Task Force [USPSTF] (2013). Tobacco use in children and adolescents: Primary care interventions. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-children-and-adolescents-primary-care-interventions. [Google Scholar]

- United States Preventive Services Task Force [USPSTF] (2015). Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: Behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions-september-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Public Health Service Office of the Surgeon General [USPHSOSG] (2020). Chapter 2: Patterns of smoking cessation among U.S. adults, young adults, and youth. In Smoking cessation: A report of the surgeon general (pp. 35–122). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555598/. [Google Scholar]