Abstract

There is a well-documented gap between research and practice in the treatment of mental health problems. One promising approach to bridging this gap is training community-based providers in evidence-based practices (EBPs). However, a paucity of valid, reliable measures to assess a range of outcomes of such trainings impedes our ability to evaluate and improve training toward this end. The current study examined the factor structure of the Acceptability, Feasibility, Appropriateness Scale (AFAS), a provider-report measure that assesses three perceptual implementation outcomes of trainings that may be leading indicators of training success (i.e., acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness). Providers who attended half-day EBP trainings for common mental health problems reported on the acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness of these trainings using the AFAS (N = 298). Confirmatory factor analysis indicates good fit to the hypothesized three-factor structure (RMSEA = .058, CFI = .990, TLI = .987). Acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness were three distinct but related constructs. Cronbach's alpha ranged from .86 to .91, indicating acceptable internal consistency for the three subscales. Acceptability and feasibility, but not appropriateness, scores varied between workshops, though variability across workshops was generally limited. This initial evaluation of the AFAS is in line with recent efforts to enhance psychometric reporting practices for implementation outcome measures and provides future directions for further development and refinement of the AFAS.

Plain Language Summary

Clinician training in evidence-based practices is often used to increase implementation of evidence-based practices in mental health service settings. However, one barrier to evaluating the success of clinician trainings is the lack of measures that reliably and accurately assess clinician training outcomes. This study was the initial evaluation of the Acceptability, Feasibility, Appropriateness Scale (AFAS), a measure that assesses the immediate outcomes of clinician trainings. This study found some evidence supporting the AFAS reliability and its three subscales. With additional item refinement and psychometric testing, the AFAS could become a useful measure of a training's immediate impact on providers.

Keywords: training, implementation outcomes, mental health, evidence-based practice

In recent decades, there have been widespread calls for better integration of evidence-based practices (EBPs) into community-based services (NAMHC, 2001). Training providers to deliver EBPs has gained attention as one promising strategy to expand access to quality services (IOM, 2010). Provider trainings are associated with positive outcomes that vary somewhat with the specific nature of the training (Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Frank et al., 2020; Herschell et al., 2010). Single-session workshops may improve EBP attitudes and knowledge, while intensive multicomponent trainings (e.g., initial workshop followed by ongoing consultation and fidelity monitoring) have shown more consistent posttraining provider EBP use. However, much remains to be learned about when, why, and how trainings produce such changes.

Systematic reviews highlight weaknesses of existing training research that limit our understanding of successful provider trainings. First, there is a lack of clarity about the most important, or most predictive, outcomes of provider trainings (Frank et al., 2020). Second, there is a dearth of validated measures that assess training outcomes (Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Frank et al., 2020; Herschell et al., 2010). Often, training studies use unvalidated “homegrown” measures that are study- or EBP-specific, limiting direct comparisons between training approaches and impeding understanding of key components of training and the mechanisms through which trainings ultimately change provider behavior.

One framework to guide the selection of training outcomes and development of corresponding measures is Proctor et al.'s (2011) implementation outcomes framework. This framework provides a taxonomy of the outcomes of a wide range of deliberate and purposive actions to implement new practices. It includes both the proximal effects or leading indicators (e.g., provider perceptions of acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness) and the more distal behavioral effects (e.g., adoption, fidelity, and sustained use of a new practice) of implementation efforts such as trainings (Lyon & Bruns, 2019; Proctor et al., 2011). Accurate assessment of these implementation outcomes is essential for evaluating whether efforts succeeded in their short-term goals (e.g., did providers find the training acceptable), and understanding how and why efforts ultimately succeed or fail to yield distal goals (e.g., is provider perception of training acceptability a key determinant of EBP adoption or sustained use).

Toward this aim, the Society for Implementation Research Collaboration (SIRC) developed the Instrument Review Project. This repository of dissemination and implementation science measures (including implementation outcome measures), guided by two implementation outcomes frameworks (i.e., the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research [Damschroder et al., 2009] and the Implementation Outcomes Framework [Proctor et al., 2011]), provides information about measures’ psychometric properties to guide measure choice in implementation efforts (Lewis et al., 2015). To date, most of these measures assess outcomes of a clinical intervention (Mettert et al., 2020). For example, the recently developed Acceptability of Intervention Measure, Intervention Appropriateness Measure, and Feasibility of Intervention Measure (Weiner et al., 2017) assess for three implementation outcomes of EBPs that may be linked with provider behavior change. Unfortunately, there are relatively few complementary measures that assess for training implementation outcomes (e.g., training acceptability, post-training attitudes, knowledge, and adoption), and even fewer have demonstrated reliability or validity (Beidas et al., 2010; Frank et al., 2020; Herschell et al., 2010; Lewis et al., 2015). While there are several notable exceptions, including measures of provider attitudes toward EBPs (e.g., EBP Attitudes Scale [Aarons, 2004]; Modified Practice Attitudes Scale [Borntrager et al., 2009]) and knowledge of EBPs (e.g., Knowledge of EBP Strategies Questionnaire; Stumpf et al., 2009), a recent review of implementation outcome measures found that many training implementation outcome measures (e.g., Training Acceptability Rating Scale [Milne, 2010]; Training/Practice acceptability, feasibility, appropriateness scale [AFAS; Lyon, 2011]; Workshop Evaluation Form [Simpson, 2002]) have limited or unknown psychometric properties (Mettert et al., 2020). Thus, psychometric evaluation of existing training implementation outcome measures is needed to guide ongoing measure development (Mettert et al., 2020).

The current study provides an initial psychometric evaluation of one such training implementation outcome measure in the SIRC repository. As part of a county-wide initiative to improve youth mental health services (Herman et al., 2021), community-based providers received half-day continuing education workshops on EBPs for common mental health problems. The Training/Practice AFAS was identified as a measure of training quality in the SIRC repository to evaluate these trainings. The AFAS assesses three perceptual implementation outcomes (i.e., acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness) that may serve as leading indicators of the success of provider trainings (Lyon & Bruns, 2019; Proctor et al., 2011). With no published psychometric data available for the AFAS, this study aimed to provide initial psychometric information on the AFAS to contribute to the recent implementation science measurement efforts.

First, the structural validity of the AFAS was evaluated. It was hypothesized that the AFAS would have three distinct but correlated factors (i.e., acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness; Proctor et al., 2011). Second, the internal consistency of the three subscales was examined. It was expected that all subscales’ internal consistency would be adequate. Third, we explored subscale variability across workshops. Of note, this psychometric evaluation was based on single-session workshops which, on their own, may rarely lead to providers’ posttraining behavior change (e.g., Beidas & Kendall, 2010). However, because workshop trainings are one of the most widely used training methods on their own and as part of multicomponent trainings (e.g., Herschell et al., 2010), psychometrically sound measures of the immediate perceptual impact of such trainings may be important to further our understanding of leading indicators of training success.

Method

Procedures

Workshops were funded by a contract to provide training in EBPs for mental health providers serving individuals aged 0 to 19 years in a Midwestern county. Trainings were voluntary, free, and provided continuing education credits. A training schedule with several workshops that spanned several months was announced three times a year (e.g., Spring Training Series). Providers signed up for as many available trainings as desired. Providers in this sample attended at least one half-day training between June 2015 and August 2018 (38 offered). Trainings provided information about the evidence base for a specified target problem and population (e.g., youth anxiety disorders), and the theory and core components of EBPs for the specified target problem and age range (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy with exposure for youth anxiety) through a combination of didactics and active learning strategies. Providers also received provider guides, client handouts, and relevant assessment measures. At the end of each workshop, providers provided anonymous AFAS and free-response feedback about any aspect of the training. Procedures were approved as exempt by the institution's Institutional Review Board (approval #3013792).

Because AFAS responses were anonymous, it was possible for providers to attend and submit AFAS responses for multiple workshops. However, it was observed that the same providers tended to attend one or more workshops within a single training series (e.g., Spring Training Series), followed by a mostly new group of providers attending the next series (e.g., Fall Training Series). Thus, this study only included AFAS responses from one randomly selected workshop from each training series to limit the instances of a provider contributing multiple AFAS responses to the study. The final sample included 298 AFAS responses completed for 11 trainings led by five trainers who were primarily doctoral level (60.00%) trainers from clinical and school psychology and psychiatry. Each workshop had an average of 32.91 attendees (SD = 9.51) and 82.32% AFAS response rate (range = 70.37%–96.43%).

Participants

The 11 trainings were attended by 230 providers. Attendees were primarily female (85.91%), White (77.39%), and master's-level (67.27%); with a mean age of 37.29 (SD = 11.93) years and 9.14 (SD = 9.33) years of clinical experience; reported social work (36.82%), counseling (32.27%), psychology (14.55%), marriage and family therapy (1.82%), psychiatry (1.36%), and other (8.18%) disciplines. Providers worked in outpatient clinics or community mental health centers (26.96%), private practice (23.48%), colleges or universities (12.61%), schools (10.00%), residential facilities (6.09%), inpatient settings (6.09%), and other settings (26.09%; e.g., day treatment, correctional facilities; the percentages sum to >100% because providers reported working in multiple settings).

Measures

The AFAS was identified as a measure of training outcomes on the SIRC repository by the local research team independent of the measure developer. The AFAS, developed by the second author prior to identification in this study, measures the implementation outcomes of acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness of provider trainings. Based on the definitions and examples articulated by Proctor et al. (2011), items were generated for each construct by the second author and then reviewed and revised by a larger research team with expertise in EBPs, provider training, and implementation science. Acceptability items (n = 6) were designed to assess the degree to which providers found the training and the practices covered in the training to be acceptable and satisfactory. Feasibility items (n = 3) were designed to assess how compatible the information and practices covered in the trainings were with providers’ routine practice settings. Appropriateness items (n = 5) were designed to assess how well the information and practices covered in the training fit with providers’ and their practice setting's mission. All items were rated on a 5-point scale (i.e., 1 = not at all, 3 = moderately, 5 = extremely), with higher ratings indicating higher acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Acceptability, feasibility, appropriateness scale (AFAS) item factor loadings, and descriptive statistics.

| Factor loading | Descriptives | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | 1a | 2b | 3c | M | SD | Range |

| 1. To what extent are you satisfied with the training you received and the practices covered? | .96 | 4.50 | 0.69 | 2-5 | ||

| 2. How credible did you find the presenters/consultants? | .86 | 4.79 | 0.47 | 2-5 | ||

| 3. How well organized and executed do you believe the training program to be? | .83 | 4.68 | 0.58 | 2-5 | ||

| 4. How satisfied are you with the content of the training and the practices covered? | .97 | 4.53 | 0.70 | 2-5 | ||

| 5. How satisfied are you with the complexity of the training and the practices covered? | .90 | 4.41 | 0.77 | 2-5 | ||

| 6. How comfortable are you with the practices contained within the training? | .54 | 4.31 | 0.76 | 2-5 | ||

| 7. How useful are the information and practices from the training to you in your everyday clinical practice? | .88 | 4.36 | 0.81 | 2-5 | ||

| 8. To what extent do you expect to be able to incorporate the concepts and techniques from the training into your daily work activities? | .90 | 4.17 | 0.86 | 1-5 | ||

| 9. How compatible do you expect the practices from the training to be with the practical realities and resources of your agency/service setting? | .93 | 4.21 | 0.87 | 2-5 | ||

| 10. How compatible are the information and practices with your agency/service setting's mission or service provision mandate? | .88 | 4.34 | 0.83 | 1-5 | ||

| 11. How relevant are the information and practices to your client population? | .85 | 4.34 | 0.85 | 2-5 | ||

| 12. How well do the information and practices fit with your current treatment modality, theoretical orientation, or skill set? | .91 | 4.29 | 0.85 | 1-5 | ||

| 13. How compatible are the information and practices with your workflow timing (e.g., when and for how long you see clients)? | .87 | 4.10 | 0.94 | 1-5 | ||

| 14. How well do the information and practices from the training fit with your overall approach to service delivery and the setting in which you provide care? | .91 | 4.27 | 0.84 | 2-5 | ||

Note. AFAS anchors were 1 = not at all, 3 = moderately, 5 = extremely.

Data analytic plan

We present descriptive statistics for all AFAS items. To examine structural validity, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to test the fit of a three-factor model to the data: acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness as three distinct but correlated latent factors. AFAS responses were nested within workshops. The nested structure was accounted for by specifying TYPE = COMPLEX and using the weighted least square mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator for categorical variables in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). RMSEA ≤ .05 and ≤.08 indicate good and adequate fit, respectively (Browne & Cudeck, 1993); CFI and TLI ≥.95 indicate good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Cronbach's alpha is presented for internal consistency, with α ≥ .70 indicating acceptable fit (Nunnally, 1978). For variability between workshops, we calculated the mean score for each AFAS subscale and compared each subscale mean across all 11 workshops using one-way analysis of variances.

Results

On average, workshops were perceived as having high acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness (see Table 1). None of the acceptability items demonstrated full range, while several feasibility and appropriateness items demonstrated full 1 to 5 range.

The fit indices suggested an adequate to good fit for the hypothesized model: RMSEA = .058, CFI = .990, and TLI = .987. As predicted, the three factors were correlated. Correlations were r = .49 between acceptability and feasibility, r = .52 between acceptability and appropriateness, and r = .92 between appropriateness and feasibility (all p < .001). Factor loadings ranged from .54 to .96 for acceptability, .88 to .93 for feasibility, and .85 to .91 for appropriateness (see Table 1). Internal consistency was acceptable for the three subscales: α = .86 for acceptability, α = .88 for feasibility, and α = .91 for appropriateness. Given the high correlation between appropriateness and feasibility, post hoc analyses were conducted to examine whether appropriateness and feasibility were a single factor. While this posthoc two-factor model (acceptability factor and a combined appropriateness/feasibility) also had adequate fit (RMSEA = .061, CFI = 0.988, TLI = 0.986), the three-factor model had a significantly better fit, , p < .001.

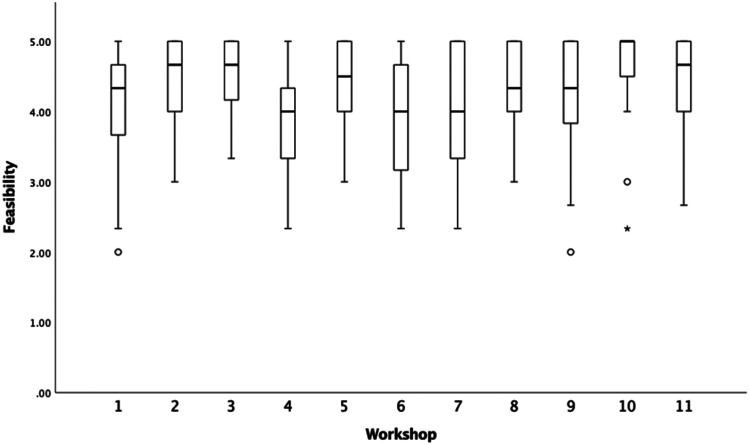

There were significant differences in subscale means for acceptability, F(10, 287) = 6.11, p < .001, and feasibility, F(10, 285) = 2.56, p = .006. Appropriateness means were not significantly different across workshops, F(10, 286) = 1.85, p = .053. While omnibus findings for acceptability and feasibility were significant, variability was generally limited (see Figures 1–3).

Figure 1.

Boxplot of acceptability scores by workshop.

Figure 2.

Boxplot of feasibility scores by workshop.

Figure 3.

Boxplot of appropriateness scores by workshop.

Discussion

The current study found preliminary support for the AFAS’ structural validity and internal consistency among providers attending half-day EBP workshops. Acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness represented three distinct but correlated factors. Acceptability was moderately correlated with both feasibility and appropriateness. Providers may tend to find workshops that cover practices they perceive as appropriate (i.e., a good fit for their clientele) and feasible (i.e., practical to implement in their service setting) as more acceptable or satisfactory. Of note, appropriateness and feasibility were highly correlated, but our posthoc results suggest the two are distinct constructs, consistent with prior findings (Weiner et al., 2017). A practice covered in a training may be easily implemented in the providers’ practice setting but may not fit well with the clientele, or a practice covered may be appropriate for the clientele but cannot be feasibly implemented in their practice setting. It is also possible that completion of the AFAS immediately posttraining increased the correlation between these two subscales. Feasibility issues (e.g., productivity requirements, documentation, and implementation resources) may not become fully apparent until providers are actively using the practice (Aarons et al., 2011), and these two subscales may be less highly correlated if completed pos-timplementation.

Lastly, acceptability and feasibility varied between workshops while appropriateness did not. These findings suggest that the AFAS can assess for workshop-specific perceptions about training acceptability and feasibility. In contrast, appropriateness did not demonstrate variability between workshops. Providers may only have attended trainings they perceived would provide information about EBPs that were appropriate in their practice setting and for their clientele, and all training content was intentionally designed to introduce practices broadly applicable to local youth mental health providers. Even with significant findings, differences between workshops were small across all three subscales. Workshops were delivered as part of a publicly funded effort to improve EBP implementation and were developed with specific attention to acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness for the intended provider population. As such, variability may be greater across workshops that are not developed with implementation outcomes in mind.

In addition to being limited in scope (i.e., factor structure and subscale reliability), the study also has three noteworthy limitations. First, the half-day, standalone workshops in this study may elicit different response styles and scale correlations than more intensive trainings. At the same time, research on workshops may be useful given that they are often a primary, and sometimes the only, training component in place to support EBP implementation. Second, we had 298 AFAS responses from 230 workshop attendees indicating that some providers contributed more than one AFAS response to the sample. Third, many AFAS items did not demonstrate full range. With the current study, it is unclear whether this is due to a limited sample of providers, trainers, and workshops, or due to the measure itself, and further psychometric evaluation is needed.

Several future directions are warranted. Evaluation of other psychometric properties is needed. Weiner et al. (2017) provide an exemplar for measure development including test–retest reliability, known-groups validity, convergent and discriminant validity, and sensitivity to change. A scoring scheme must also be developed and evaluated (i.e., whether AFAS scores predict distal outcomes) for the AFAS to aid decision-making (Mettert et al., 2020). The AFAS may also benefit from a refinement of double-barreled items. Several items reference both the training processes and content which, while making for a briefer measure, may conflate perceptions of the training itself with perceptions of the practices covered. Strategies used to train providers and the content covered in these trainings may differentially impact proximal and distal implementation goals, and further revision of the items to focus on the training itself is needed.

In summary, this study provides an initial psychometric evaluation of the AFAS in line with recent calls for improved reporting practices and data generation for existing implementation measures (Mettert et al., 2020). Further refinement and evaluation of the AFAS and other training implementation outcome measures are needed to provide the tools necessary to advance the science and dissemination of provider training.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Boone County Children's Services Fund to Kristin M. Hawley.

ORCID iDs: Evelyn Cho https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9992-7807

Aaron R. Lyon https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3657-5060

Kristin M. Hawley https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9542-6095

References

- Aarons G. A. (2004). Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: The evidence-based practice attitude scale (EBPAS). Mental Health Services Research, 6(2), 61–74. 10.1023/b:mhsr.0000024351.12294.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons G. A., Hurlburt M., Horwitz S. M. (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(1), 4–23. 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas R. S., Edmunds J. M., Marcus S. C., Kendall P. C. (2010). Training and consultation to promote implementation of an empirically supported treatment: A randomized trial. Psychiatric Services, 63(7), 660–665. 10.1176/appi.ps.201100401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas R. S., Kendall P. C. (2010). Training therapists in evidence-based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology, 17(1), 1–30. 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.07.011.Innate [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borntrager C. F., Chorpita B. F., Higa-McMillan C., Weisz J. R. (2009). Provider attitudes toward evidence-based practices: Are the concerns with the evidence or with the manuals? Psychiatric Services, 60(5), 677–681. 10.1176/ps.2009.60.5.677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne M. W., Cudeck R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Bollen K. A., Long J. S. (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder L. J., Aron D. C., Keith R. E., Kirsh S. R., Alexander J. A., Lowery J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), 1–15. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank H. E., Becker-Haimes E. M., Kendall P. C. (2020). Therapist training in evidence-based interventions for mental health: A systematic review of training approaches and outcomes. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 27(3), 1–30. https://doi.og/10.1111/cpsp.12330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman K. C., Reinke W. M., Thompson A. M., Hawley K. M. (2019). The Missouri Prevention Center: A multidisciplinary approach to reducing the societal prevalence and burden of youth mental health problems. American Psychologist, 74(3), 315–328. 10.1037/amp0000433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschell A. D., Kolko D. J., Baumann B. L., Davis A. C. (2010). The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: A review and critique with recommendations. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(4), 448–466. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Bentler P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Planning a Continuing Health Professional Education Institute (2010). Redesigning continuing education in the health professions. National Academies Press (US). Summary. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK219801/ [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C. C., Stanick C. F., Martinez R. G., Weiner B. J., Kim M., Barwick M., Comtois K. A. (2015). The society for implementation research collaboration instrument review project: A methodology to promote rigorous evaluation. Implementation Science, 10(1), 1–18. 10.1186/s13012-014-0193-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon A. (2011). Training/Practice Acceptability/Feasibility/Appropriateness Scale [Unpublished manuscript]. Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon A. R., Bruns E. J. (2019). User-centered redesign of evidence-based psychosocial interventions to enhance implementation—hospitable soil or better seeds? JAMA Psychiatry, 76(1), 3–4. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mettert K., Lewis C., Dorsey C., Halko H., Weiner B. (2020). Measuring implementation outcomes: An updated systematic review of measures’ psychometric properties. Implementation Research and Practice. 10.1177/2633489520936644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne D. (2010). Can we enhance the training of clinical supervisors? A national pilot study of an evidence-based approach. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 17(4), 321–328. 10.1002/cpp.657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L. K., Muthén B. O. (2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. ttps://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/MplususerguideVer_7_r3_web.pdf [Google Scholar]

- The National Advisory Mental Health Council Workgroup on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention Development and Deployment (2001). Blueprint for change: Research on child and adolescent mental health. Rockville, MD.

- Nunnally J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E., Silmere H., Raghavan R., Hovmand P., Aarons G., Bunger A., Griffey R., Hensley M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(2), 65–76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson D. D. (2002). A conceptual framework for transferring research to practice. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 22(4), 171–182. 10.1016/S0740-5472(02)00231-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumpf R. E., Higa-McMillan C. K., Chorpita B. F. (2009). Implementation of evidence-based services for youth: assessing provider knowledge. Behavior Modification, 33(1), 48–65. 10.1177/0145445508322625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner B. J., Lewis C. C., Stanick C., Powell B. J., Dorsey C. N., Clary A. S., Boynton M., Halko H. (2017). Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implementation Science, 12(1), 108. 10.1186/s13012-017-0635-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]