Abstract

Background:

In light of short lengths of stay and proximity to communities of release, jails are well-positioned to intervene in opioid use disorder (OUD). However, a number of barriers have resulted in a slow and limited implementation.

Methods:

This paper describes the development and testing of a Medication for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD) Implementation Checklist developed as part of a Building Bridges project, a two-year planning grant which supported 16 US jail systems as they prepared to implement or expand MOUD services.

Results:

Although initially developed to track changes within sites participating in the initiative, participants noted its utility for identifying evidence-based benchmarks through which the successful implementation of MOUDs could be tracked by correctional administrators.

Conclusions:

The findings suggest that this checklist can both help guide and illustrate progress toward vital changes facilitated through established processes and supports.

Plain Language Summary:

People incarcerated in jails are more likely to have opioid use disorder than the general population. Despite this, jails in the United States (U.S.) often offer limited or no access to Medication for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD). The Building Bridges project was designed to address this gap in 16 U.S. jail systems as they prepared to implement or expand MOUD services. This article addresses the use of a MOUD checklist that was initially designed to help the jails track changes toward evidence-based benchmarks. The findings suggest that this checklist can both help guide and illustrate progress toward vital changes facilitated through established processes and supports.

Keywords: jails, opioid use disorder, medications for opioid use disorder, implementation checklist

Opioid overdose deaths have been rising in the United States, accounting for almost 70% of all drug overdose deaths (Stephenson, 2020; Wilson et al., 2020). Additionally, it has been estimated that approximately 80% of arrests are related to drug and/or alcohol use and behaviors associated with drug distribution or acquisition (Sugarman et al., 2020). Even during incarceration, the use of opioids remains surprisingly high. It has been reported that 16.6% and 18.9% of state prisoners and sentenced jail inmates, respectively, reported using heroin or other opiates regularly (Bronson & USDOJ, 2017). Despite this, few jails provide adequate withdrawal and treatment services for people with opioid use disorder (OUD) (Bronson & USDOJ, 2017; Krawczyk et al., 2017; Lopez, 2018).

Medications for opioid use disorder (MOUDs) are an evidence-based treatment and are considered the standard of care in clinical settings but correctional settings have been slow to adopt them (Carson & Cowhig, 2020; Klein, 2018). For instance, out of over 3,000 local and county jails that operate in the Unites States, fewer than 200 in only 30 states reported providing MOUDs in 2018 (Carson & Cowhig, 2020; Klein, 2018). This is often limited to extended-release naltrexone delivery prior to release into the community (Krawczyk et al., 2017; Lopez, 2018; Vestal, 2018). Even those jails that follow best practices and provide MOUDs for pregnant women with OUD (Peeler et al., 2019) typically taper and then cease this provision following birth or termination of the pregnancy (Krawczyk et al., 2017; Lopez, 2018; National Sheriffs’ Association (NSA) & National Commission on Correctional Health Care (NCCHC), 2018; O’Connor & Bowling, 2020; Vestal, 2018).

In light of the often-short lengths of stay and proximity to communities of release, jails are well-positioned to intervene in substance use disorders and connect incarcerated people to ongoing care in the community (Stöver & Michels, 2010). More recently, the practice has begun to change as key community stakeholders and jails identify and overcome barriers to implementing MOUDs (Klein, 2018). Such translational approaches are tasked with cultivating cross-system collaborations and systems of care that span from correctional facilities to community-based treatment.

Despite the expansion of access to MOUDs in communities across the Unites States, there are often a number of concerns that arise as barriers specific to jails. Barriers include concerns regarding the potential diversion of medications, overdoses, and withdrawal-related deaths (Fiscella et al., 2020; White et al., 2016), as well as service delivery shortcomings, since the administration of MOUDs often requires additional staff effort, special training (e.g., an X waiver for providers prescribing buprenorphine), and systems of monitoring administration (NSA & NCCHC, 2018). This may be compounded by the preference among administrators for non-MOUD interventions and numerous state and federal regulations regarding opioid agonist treatment (Friedmann et al., 2012; Moore et al., 2018; Zaller et al., 2013). Navigating these challenges and barriers has slowed the pace of MOUD-uptake in correctional environments nationwide, as jails struggle to address known and unknown barriers in order to implement MOUDs within their facilities.

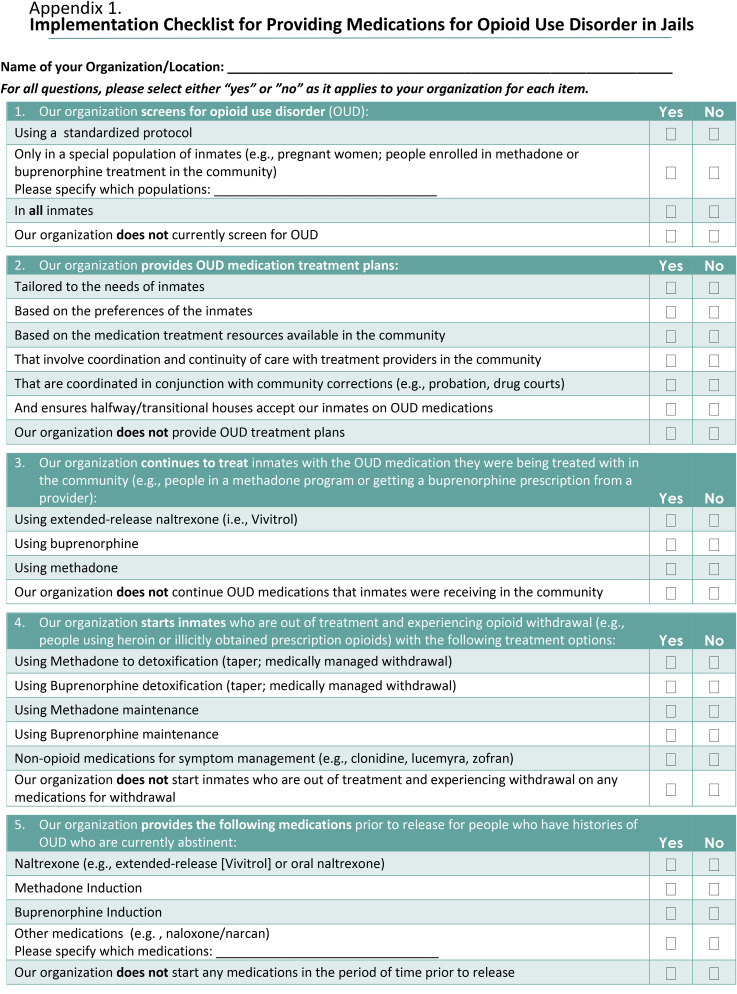

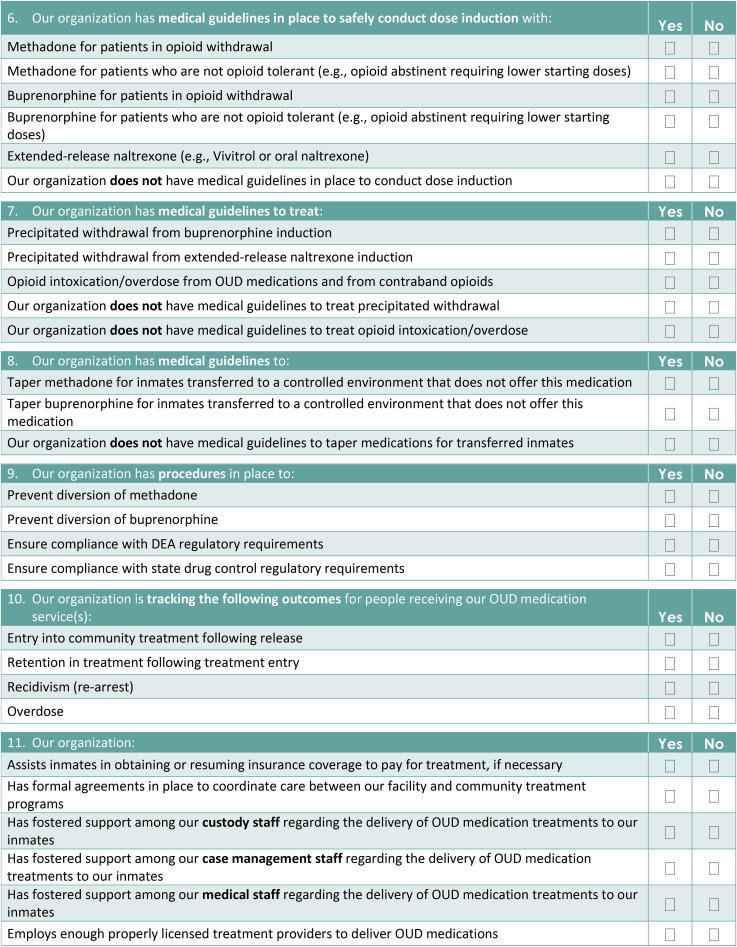

This paper describes the development of an MOUD Implementation checklist for jails (Appendix 1) developed for use in the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) and Arnold Ventures’ funded “Planning initiative to build bridges between jail and community-based treatment for opioid use disorder” (Building Bridges) project, which supported 16 US jurisdictions as they prepared to implement or expand MOUD services in their jails with continuation in the community. The 16 jurisdictions spanned the continental United States and represented a range of treatment capacity at baseline, with the size of the facility, number of inmates, and clinical services varying considerably based on the communities they served. Sites participating were required to commit a multidisciplinary team comprised of local stakeholders including jail, community corrections, and community treatment leadership. Although initially developed as an evaluation tool for tracking changes made relative to MOUD administration in jails participating in the Building Bridges project, the checklist can also provide correctional administrators and staff a set of benchmarks through which the successful implementation of MOUDs can be tracked in correctional systems, while ensuring alignment with evidence-based practices. This paper presents findings from the initial use of the checklist in the planning initiative.

Methods

The project was reviewed by WIRB and determined to be exempt under 45 CFR 46.102(l). Participants were provided with an information sheet describing the nature of the project and their ability to decline participation without penalty.

Checklist Development

The implementation checklist for MOUDs in jails was developed to capture MOUD-specific implementation components to document progress in the Building Bridges project. The checklist items were developed based on the existing jail MOUD implementation literature, such as the practice guidelines described by the National Sheriff's Association and National Commission on Correctional Health Care (NCCHC) report “Jail-Based Medication-Assisted Treatment: Promising practices, guidelines, and resources for the field” (Klein, 2018), as well as other correctional and clinical MOUD research (ASAM, 2015; Fu et al., 2013; Gordon et al., 2008; Kinlock et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2015; Magura et al., 2009; NCCHC, 2016; NIDA, 2016a; NIDA, 2016b; O’Brien & Cornish, 2006; Rich et al., 2015; SAMHSA, 2018; Smith & Strashny, 2016). This was augmented by team-based input from experienced researchers and clinicians with expert knowledge on the topic. Through a series of in-person team meetings, the initial checklist items were drafted, and organized thematically by service delivery topic, first focusing on elements necessary for identifying and initiating patients on MOUDs, then on the processes and procedures necessary for their successful implementation. When appropriate, new checklist items were added to specify which MOUD was being delivered and to which jail population (e.g., only pregnant women, only patients receiving MOUDs in the community). The checklist was revised multiple times until a group consensus was reached concerning its content. Items were then edited and, if necessary, reworded to ensure that the yes/no response options were suitable.

The final implementation checklist, comprised of 11 domains and a total of 56 yes/no items, assessed: the jail's level of OUD screening; MOUDs provided (and to which populations); the provision of medical guidelines for dose induction, and medication tapering for people being transferred to other facilities that do not offer MOUDs; procedures to prevent diversion; the tracking of patient outcomes in the community; and broader milieu factors.

Checklist Administration

The checklist was first administered at baseline during the Building Bridges kickoff meeting in August 2019 at the start of the planning initiative. During this in-person meeting, each jurisdiction's team, comprised of jail health care providers, jail leadership, public safety administrators, probation/parole representatives, and the local behavioral health department overseeing substance use treatment, completed a hard copy of the implementation checklist, usually as part of a group discussion.

The checklist's follow-up administration occurred in conjunction with the end of the planning initiative (March–April 2020). A PDF version of the checklist was emailed to each jurisdiction's team lead, who largely completed the checklist independently, sometimes seeking verification from the team's correctional health staff representative. There were minor wording changes to the instructions between the baseline and follow-up administrations to help ensure a response was given to all items within each domain, but the checklist items remained consistent. The checklists were completed on paper, scanned, and emailed to the research staff. All 16 jurisdictions completed the checklist both at baseline and follow-up.

Data Cleaning and Entry

The baseline checklist was completed at an in-person convening of all sites, however; the second checklist was emailed to sites. At follow-up, the research staff emailed or phoned the team lead if blank or conflicting responses were endorsed. In these cases, team leads most often conferred with other relevant team members to clarify responses or complete blank responses. Revised versions of the completed checklists were returned to the research staff via email.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted. Due to the small sample size, outcomes are reported in text as a change at follow-up in the percent of sites endorsing that item, out of the total number of sites that endorsed the item at baseline. This reporting mirrors the final column in Table 1.

Table 1.

Jail-based medication for opioid use disorder implementation checklist (N = 16).

| Implementation checklist items | Baseline | Follow-up | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Screening for opioid use disorder (OUD) | |||

| Using a standardized protocol | 12 (75%) | 15 (94%) | 3 (19%) |

| Only in a special population for opioid use disorder | 2 (13%) | 5 (31%) | 3 (19%) |

| In all inmates | 14 (88%) | 12 (75%) | −2 (−13%) |

| Our organization does not currently screen for OUD | 2 (13%) | 2 (13%) | 0 (0%) |

| Providing OUD medication treatment plans | |||

| Provides OUD medication treatment plans tailored to the needs of inmates | 8 (50%) | 11 (69%) | 3 (19%) |

| Provides OUD medication treatment plans based on inmate preferences | 6 (38%) | 8 (50%) | 2 (13%) |

| Provides OUD medication treatment plans based on medications available in the community | 7 (44%) | 11 (69%) | 4 (25%) |

| Provides OUD medication treatment plans that coordinate with community treatment providers | 8 (50%) | 13 (81%) | 5 (31%) |

| Provides OUD medication treatment plans coordinated with community corrections (e.g., probation, drug courts) | 8 (50%) | 11 (69%) | 3 (19%) |

| Provides OUD medication treatment plans that ensures halfway/transitional houses accept people on OUD medications | 6 (38%) | 11 (69%) | 5 (31%) |

| The organization does not provide OUD treatment plans | 4 (25%) | 2 (13%) | −2 (−13%) |

| Continuing inmates on MOUDs | |||

| Continues community extended-release naltrexone | 6 (38%) | 11 (69%) | 5 (31%) |

| Continues community buprenorphine | 7 (44%) | 10 (63%) | 3 (19%) |

| Continues community methadone | 10 (63%) | 8 (50%) | −2 (−13%) |

| Does not continue community OUD medications | 4 (25%) | 6 (38%) | 2 (13%) |

| Initiating medically managed withdrawal | |||

| Provides medically managed withdrawal with methadone to those out of care experiencing opioid withdrawal | 5 (31%) | 2 (13%) | −3 (−19%) |

| Provides medically managed withdrawal with buprenorphine to those out of care experiencing opioid withdrawal | 3 (19%) | 6 (38%) | 3 (19%) |

| Initiates methadone maintenance to those out of care with opioid withdrawal symptoms | 5 (31%) | 5 (31%) | 0 (0%) |

| Initiates buprenorphine maintenance to those out of care with opioid withdrawal symptoms | 4 (25%) | 7 (44%) | 3 (19%) |

| Provides non-opioid medications for withdrawal symptom management (e.g., clonidine, lofexidine, ondansetron) | 12 (75%) | 14 (88%) | 2 (13%) |

| Does not provide any medications for withdrawal | 4 (25%) | 5 (31%) | 1 (6%) |

| MOUD induction prior to release | |||

| Provides naltrexone (e.g., extended-release or oral) induction prior to release | 10 (63%) | 11 (69%) | 1 (6%) |

| Provides methadone induction prior to release | 1 (6%) | 3 (19%) | 2 (13%) |

| Provides buprenorphine induction prior to release | 6 (38%) | 8 (50%) | 2 (13%) |

| Provides other medications prior to release | 3 (19%) | 9 (56%) | 6 (38%) |

| Does not start any OUD medications prior to release | 5 (31%) | 4 (25%) | −1 (−6%) |

| Guidelines for dose induction | |||

| Has medical guidelines to conduct methadone dose induction for patients with opioid withdrawal | 1 (6%) | 7 (44%) | 6 (38%) |

| Has medical guidelines to conduct methadone dose induction for patients who are not opioid tolerant | 0 (0%) | 6 (38%) | 6 (38%) |

| Has medical guidelines to conduct buprenorphine dose induction for patients with opioid withdrawal | 5 (31%) | 11 (69%) | 6 (38%) |

| Has medical guidelines to conduct buprenorphine dose induction for patients who are not tolerant | 4 (25%) | 11 (69%) | 7 (44%) |

| Has medical guidelines to conduct extended-release naltrexone dose induction | 7 (44%) | 13 (81%) | 6 (38%) |

| Our organization does not have medical guidelines in place to conduct dose induction | 8 (50%) | 2 (13%) | −6 (−38%) |

| Medical guidelines to treat withdrawal, intoxication, & overdose | |||

| Has medical guidelines to treat precipitated withdrawal from buprenorphine | 8 (50%) | 11 (69%) | 3 (19%) |

| Has medical guidelines to treat precipitated withdrawal from extended-release naltrexone | 8 (50%) | 11 (69%) | 3 (19%) |

| Has medical guidelines to treat opioid intoxication/overdose | 12 (75%) | 14 (88%) | 2 (13%) |

| Has medical guidelines to treat precipitated withdrawal | 2 (13%) | 4 (25%) | 2 (13%) |

| Does not have medical guidelines to treat opioid intoxication/overdose | 3 (19%) | 3 (19%) | 0 (0%) |

| Medical guidelines for medication taper | |||

| Has guidelines to taper methadone for inmates transferred to a controlled environment without this medication | 6 (38%) | 8 (50%) | 2 (13%) |

| Has guidelines to taper buprenorphine for inmates transferred to a controlled environment without this medication | 5 (31%) | 9 (56%) | 4 (25%) |

| Does not have medical guidelines to taper medications for transferred inmates | 7 (44%) | 0 (0%) | −7 (−44) |

| Procedures for compliance | |||

| Has procedures in place to prevent diversion of methadone | 9 (56%) | 12 (75%) | 3 (19%) |

| Has procedures in place to prevent diversion of buprenorphine | 7 (44%) | 13 (81%) | 6 (38%) |

| Has procedures in place to ensure compliance with DEA regulations | 12 (75%) | 14 (88%) | 2 (13%) |

| Has procedures in place to ensure compliance with state drug control regulations | 13 (81%) | 14 (88%) | 1 (6%) |

| Does not have procedures in place to ensure prevention or compliance | 3 (19%) | 2 (13%) | −1 (−6%) |

| Community tracking & connections | |||

| Tracking outcomes for entry into community treatment following release | 6 (38%) | 8 (50%) | 2 (13%) |

| Tracking outcomes for retention in treatment | 4 (25%) | 5 (31%) | 1 (6%) |

| Tracking recidivism (re-arrest) | 4 (25%) | 7 (44%) | 3 (19%) |

| Tracking post-release overdose | 3 (19%) | 5 (31%) | 2 (13%) |

| Does not track outcomes post-release | 8 (50%) | 6 (38%) | −2 (−13) |

| Assists inmates in obtaining or resuming health insurance coverage | 12 (75%) | 11 (69%) | −1 (−6%) |

| Has formal agreements to coordinate care with community treatment programs | 10 (63%) | 10 (81%) | 0 (0%) |

| Staffing | |||

| Has fostered support among custody staff surrounding OUD medications | 9 (56%) | 13 (81%) | 4 (25%) |

| Has fostered support among case management staff surrounding OUD medications | 8 (50%) | 12 (75%) | 4 (25%) |

| Has fostered support among our medical staff surrounding OUD medications | 13 (81%) | 12 (75%) | −1 (−6%) |

| Employs enough properly licensed treatment providers to deliver OUD medications | 7 (44%) | 10 (63%) | 3 (19%) |

Notes. Baseline data collection in August 2019 at the start of the Bridges planning initiative. Follow-up data collection in March and April 2020 at the end of the planning initiative.

Results

Treatment Plans

The increased understanding of evidence-based MOUD practices and high levels of readiness among team members culminated in considerable changes being made over the course of the nine-month planning initiative, both in the planning for and delivery of MOUDs in participating jails. As displayed in Table 1, gains were made in terms of providing MOUD treatment plans tailored to the needs (from 8 to 11 sites, +19%) and preferences (from 6 to 8 sites, +13%) of inmates, coordinated with community treatment providers (from 8 to 13 sites, +31%) and based on the medications available in the community (from 7 to 11 sites, +25%), and that ensured halfway/transitional houses would accept inmates on MOUDs (from 6 to 11 sites, +31%).

Continuation of Community Medications

Gains were also made by the end of the initiative in the number of facilities that were continuing their incarcerated patients with extended-release naltrexone (from 6 to 11 sites; +31%) and buprenorphine (from 7 to 10 sites; +19%) for individuals who were receiving either of these medications in the community prior to incarceration. However, there was a decrease in the number of facilities that maintained individuals on methadone if they were receiving it in the community prior to incarceration (from 10 to 8 sites; −13%), as well as an increase in the number of facilities that reported not continuing incarcerated people on any MOUDs received in the community (from 4 to 6 sites; +13%).

Medically Managed Withdrawal

Similarly, there were changes in terms of which medications were being used for medically managed opioid withdrawal. The number of sites using buprenorphine for withdrawal treatment increased (from 3 to 5 sites; +19%) while those using methadone decreased (from 5 to 2 sites; −19%) at follow-up. There were also increases in the number of facilities that offered non-opioid medications for withdrawal symptom management (e.g., clonidine, lofexidine, odansetron) (from 12 to 14; +13%).

Initiating Medication Maintenance

With regard to medication maintenance during incarceration, there was no change in the number of facilities that reported continuing methadone maintenance for those individuals experiencing opioid withdrawal who were not in treatment (5 of 16 sites; +0%). In contrast, there were increases in the number of facilities that initiated buprenorphine maintenance for those individuals experiencing opioid withdrawal who were not in treatment at the time of detention (from 4 to 7 sites; +19%). The number of facilities that reported continuing community extended-release naltrexone increased sharply (from 6 to 11 sites; 31%). There was one additional facility at follow-up that reported not initiating incarcerated individuals on any MOUD if they were experiencing opioid withdrawal symptoms but were not in treatment (from 4 to 5 sites; +6%).

Medication Induction

Additionally, the number of sites that provided naltrexone (from 10 to 11 sites; +6%), methadone (from 1 to 3 sites; +13%), and buprenorphine (from 6 to 8 sites; +13%) induction for people with histories of OUD prior to release from jail increased at follow-up. There was one fewer facility (from 5 to 4 sites; −6% of sites) that reported not starting any MOUDs prior to release for people with histories of OUD.

Medical Guidelines

Perhaps the most notable MOUD-related improvements at follow-up were associated with the establishment of medical guidelines to safely conduct dose inductions using methadone (from 1 to 7 sites; +38%) and/or buprenorphine (from 5 to 11 sites; +38%) for patients in opioid withdrawal. There were also gains in methadone (from 0 to 6 sites; +38%) and/or buprenorphine (from 4 to 11 sites; +44%) medical guidelines for people who were presently abstinent. There were smaller gains in the establishment of medical guidelines for methadone (from 6 to 8 sites; +13%) and/or buprenorphine tapers (from 5 to 9 sites; +25%). More sites reported having procedures in place to prevent diversion of methadone (from 9 to 12 sites; +19%) and buprenorphine (from 7 to 13; + 38%) at follow-up compared with baseline. More sites also reported having procedures to ensure DEA (from 12 to 14 sites; +13%) and state drug control regulatory compliance (from 13 to 14 sites; +6%) at follow-up.

Outcome Tracking

Although comparatively lower overall, at follow-up more sites reported being able to track outcomes for people on MOUD once they are released into the community, including whether or not someone enters a program with their community treatment partners (from 6 to 8 sites; +13%), are retained in treatment (from 4 to 5 sites; +6%), or experience an overdose (from 3 to 5 sites; +13%). The greatest gains in data tracking surrounded re-arrest and/or recidivism (from 4 to 7 sites; +19%).

Support

Several sites reported fostering support among custody (9–13 sites; +25%) and case management staff (8–12 sites; +25%) regarding the delivery of MOUDs and reported employing enough properly licensed providers to deliver MOUDs (7–10 sites; +19%). There were slight decreases in sites reporting assisting incarcerated people in resuming or obtaining health insurance coverage to pay for treatment (13–12 sites; −6%). Additionally, there was no change from baseline to follow-up in the number of facilities with formal agreements with community treatment programs.

Discussion

The MOUD implementation checklist appears to have captured changes in evidence-based practices necessary for the delivery of MOUDs in jails, as progress was aligned with the topic areas addressed by sites during their involvement in the Building Bridges planning initiative. Over the course of developing this checklist, there was a delicate balance to be struck between comprehensiveness and conciseness, so that it would not become too cumbersome or time-consuming to complete. It was for this reason, for instance, that during development the checklist was changed from a Likert scale to a binary yes/no checklist format. In its complete form, it was estimated to take approximately 5 min to complete, when the information was readily available to the person completing it. However, the amount of time that it took appears to have been influenced by the degree to which information regarding practice was siloed, as correctional health staff may have possessed more information regarding things like medication initiation but jail administrators may have more knowledge regarding their ability to track outcomes and fostering staff support. This speaks to the organizational effort required to implement or expand MOUD care in jails.

There was a sharp increase in the number of jails that offered continuing naltrexone or buprenorphine during incarceration. In contrast, the number of jails that reported continuing methadone treatment declined. This may be due to the fact that buprenorphine is easier to deliver, even with the X waiver requirements, because it has fewer regulatory restrictions than methadone. Naltrexone formulations have been more widely adopted in correctional facilities, possibly due to decreased concern about their diversion. This made them easier to implement at a more rapid pace. In some cases, jails that initially reported continuing patients on methadone or Vivitrol if they were receiving it in the community changed their answers at follow-up, likely indicating increased awareness of current practices (rather than discontinuation of services) and areas in need of further attention in order to expand care.

There was also a shift in medications used for medically managed withdrawal during the intervention. Four jails reported no longer using methadone for detox at follow-up but one new jail reported now using it and another jail maintained its use. In contrast, one jail reported no longer using buprenorphine for detox at follow-up, while four new jails reported starting using it for this purpose and another jail maintained its use. In addition, the number of jails that reported using no medication to treat opioid withdrawal increased from 5 to 6. Curiously, and in contrast to the reduction in the number of jails that reported administering methadone for medically managed withdrawal, the number of jails that reported initiating methadone prior to release increased from 1 to 3. Increases were also reported for the number of jails initiating buprenorphine (from 6 to 8) and oral or extended-release naltrexone (from 10 to 11) prior to release. This result is encouraging because it indicates the recognition that jails can serve an important role in protecting people from relapse and overdose in the community (Alex et al., 2017; Wenger et al., 2019). It is noteworthy that participation in the Building Bridges planning initiative was meant to increase readiness for MOUD delivery, so the large gains observed in the provision of services from baseline to follow-up was an unexpected surprise.

The planning initiative provided robust technical support for teams as they developed treatment manuals and protocols, so the fact that the greatest gains at follow-up were observed in items assessing the presence of guidelines for dose inductions and medication tapers was not surprising. It likely reflects the often-stepwise implementation process and, perhaps, indicates that the structure of the checklist should be reorganized to better guide jails through the process of implementing MOUDs. Making sample guidelines for medication use available to the facilities in order to generate the best, consistent medical practice based on scientific evidence or a consensus of medical opinion (Onion & Walley, 1995) may be particularly helpful in taking initial steps that will pave the way for increased medication service provision in the future. This is of importance because initiating methadone or buprenorphine prior to release in individuals with OUD who have been abstinent while in a controlled environment required a considerably lower initial dose (e.g., methadone 5 mg and buprenorphine 1 or 2 mg) and slower rates of increase than is typically provided for people who are experiencing opioid withdrawal at the time of arrest (Kinlock et al., 2007; SAMHSA, 2018; Vocci et al. 2015). In addition, while it might be assumed that individuals initiating naltrexone prior to release were also opioid abstinent, this is not always the case. As such, naltrexone induction should proceed cautiously as well.

Although sites reported fostering support for MOUDs among custody and case management staff, it was not the goal of this checklist to capture how this was achieved or how it was measured. Staff support has been shown to be important to the successful implementation of MOUDs. Overall, fewer sites reported they had staff to assist incarcerated people in resuming or obtaining health insurance coverage at follow-up, even when there were increases in adequate prescribing staff reported.

The use of checklists in conjunction with coaching to foster the implementation of evidence-based practices has been noted in other fields (Hales et al., 2008; Kara et al., 2017; Snyder et al., 2015). Although the checklist was developed and used as a tool to monitor change and progress in the project's evaluation, the coaches received copies of the baseline checklist and may have used it in their monthly coaching sessions. MOUD implementation checklists, such as the one developed for this project, could be useful to jails for many reasons, with or without the use of coaching support, such as providing correctional administrators and staff a set of benchmarks through which the successful implementation of MOUDs can be tracked in correctional systems, while ensuring alignment with evidence-based practices. Some sites reported that the checklist helped to keep them focused on implementation areas during the planning phase. Even a site with experience providing MOUDs to limited populations reported that they found the checklist helpful in persuading their jail administration to complete the remaining steps necessary to expand and improve MOUD service provisions. Lastly, sites reported that the checklist could be useful to reference during contract renegotiations with healthcare vendors.

Limitations

This project lacked experimental control and was not designed to rigorously examine the psychometric properties of the checklist, resulting in a largely descriptive understanding of the checklist and its ability to capture change in the implementation of evidence-based MOUD practices in these jails. Additionally, the differing checklist administration processes, including group completion at baseline and completion of the checklist by a sole team member at follow-up, may have accounted for some of the changes reported. The Yes/No format of the checklist does not offer respondents an opportunity to “explain” or document gradations, which limited our ability to fully interpret some of the changes reported at follow-up. Given that there were sometimes missing responses or both “yes” and “no” endorsed for the same item, it may be worth considering whether binary response options adequately capture some of these practices. The degree to which the findings may generalize to other jurisdictions, particularly in light of the initiative and commitment demonstrated by the 16 Building Bridges sites, is unclear. Finally, the project did not collect any demographic variables or specific staffing numbers as part of the data collection activities.

Conclusion

Jails represent important sites of intervention and care provision for people with OUD (Belenko et al., 2013; Binswanger et al., 2007; Binswanger et al., 2013; Zaller et al., 2013). This implementation pilot project suggests that having a simple checklist accounting for best practices and implementation considerations can both help guide and illustrate progress. Such a checklist can be used in conjunction with coaching as an implementation strategy, or to provide guidance toward best practices as correctional and health care administrators identify areas to target to increase MOUD treatment capacity and improve patient outcomes. Although the checklist itself is a useful tool to document the implementation of MOUD in jails, critical attention still needs to be given to the nature of the overall implementation process and the factors associated with those processes in order for successful MOUD implementation to occur.

Appendix

Footnotes

Authors’ note: Ariel Ludwig, PhD – Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing-Original Draft, Data Curation, Visualization, Writing-Original Draft, Writing – Review and Editing. Laura B. Monico, PhD – Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – Review and Editing. Thomas Blue, PhD - Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – Review and Editing. Michael S. Gordon – Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Funding Acquisition, Writing – Review and Editing. Robert P. Schwartz, MD – Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – Review and Editing. Shannon Gwin Mitchell, PhD – Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Funding Acquisition, Writing – Review and Editing.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute on Drug Abuse [grant number 3R01DA043476-02S1]. Dr. Monico received research funding from Indivior. Dr. Gordon reports support (study drug) from Braeburn and research grant support from MedicaSafe. Dr. Schwartz has provided consultation for Verily Life Sciences. He was PI of a NIDA funded study that received study medication from Alkermes and Indivior.

References

- Alex B., Weiss D. B., Kaba F., Rosner Z., Lee D., Lim S., Venters H., MacDonald R. (2017). Death after jail release. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 23, 83–87. 10.1177/1078345816685311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Addiction Medicine [ASAM]. (2015). The ASAM: National practice guideline for the use of medications in the treatment of addiction involving opioid use. American Society of Addiction Medicine. Retrieved April 22, 2022, from https://www.asam.org/quality-care/clinical-guidelines/national-practice-guideline?gclid=Cj0KCQjwpImTBhCmARIsAKr58cxP7OeAJtba_e6F6DE_4xuE8xHQTHrquFj6z4h-jmvAUcdwvCcY2cIaAjZYEALw_wcB

- Belenko S., Hiller M., Hamilton L. (2013). Treating substance use disorders in the criminal justice system. Current Psychiatric Report, 15, 414. 10.1007/s11920-013-0414-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger I. A., Blatchford P. J., Mueller S. R., Stern M. F. (2013). Mortality after prison release: Opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Annals of Internal Medicine, 159, 592–600. 10.7326/0003-4819-159-9-201311050-00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger I. A., Stern M. F., Deyo R. A., Heagerty P. J., Cheadle A., Elmore J. G., Koepsell T. D. (2007). Erratum for: Release from prison--a high risk of death for former inmates. The New England Journal of Medicine, 356, 536–536. 10.1056/NEJMx070008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronson J., & United States. Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2017). Drug use, dependence, and abuse among state prisoners and jail inmates, 2007–2009, 1995–2013 (Ser. Special report). U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved April 22, 2022, from https://permanent.fdlp.gov/gpo88216/dudaspji0709.pdf____L.pdf

- Carson E. A., Cowhig M. P. (2020) Mortality in Local Jails, 2000–2016 – Statistical Tables. United States Department of Justice. Retrieved April 22, 2022, from https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=6767

- Fiscella K., Noonan M., Leonard S. H., Farah S., Sanders M., Wakeman S. E., Savolainen J. (2020). Drug- and alcohol-associated deaths in U.S. Jails. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 26, 183–193. 10.1177/1078345820917356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann P. D., Hoskinson R., Gordon M., Schwartz R., Kinlock T., Knight K., Flynn P. M., Welsh W. N., Stein L. A. R., Sacks S., O’Connell D. J., Knudsen H. K., Shafer M. S., Hall E., Frisman L. K., & Mat Working Group Of CJ-Dats. (2012). Medication-assisted treatment in criminal justice agencies affiliated with the criminal justice-drug abuse treatment studies (CJ-DATS): Availability, barriers, and intentions. Substance Abuse, 33, 9–18. 10.1080/08897077.2011.611460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J. J., Zaller N. D., Yokell M. A., Bazazi A. R., Rich J. D. (2013). Forced withdrawal from methadone maintenance therapy in criminal justice settings: A critical treatment barrier in the United States. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 44, 502–505. 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon M. S., Kinlock T. W., Schwartz R. P., Fitzgerald T. T., O’Grady K. E., Vocci F. J. (2008). A randomized clinical trial of methadone maintenance for prisoners: Findings at 6 months post-release. Addiction, 103, 1333–1342. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.002238.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales B., Terblanche M., Fowler R., Sibbald W. (2008). Development of medical checklists for improved quality of patient care. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 20, 22–30. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kara N., Firestone R., Kalita T., Gawande A. A., Kumar V., Kodkany B., Saurastri R.,, Singh V. P., Maji P., Karlage A., Hirschhorn L. R., Semrau K. E. A., & on behalf of the BetterBirth Trial Group. (2017). The BetterBirth Program: Pursuing effective adoption and sustained use of the WHO Safe Childbirth Checklist through coaching-based implementation in Uttar Pradesh, India. Global Health: Science and Practice, 5, 232–243. 10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock T. W., Gordon M. S., Schwartz R. P., O’Grady K., Fitzgerald T. T., Wilson M. (2007). A randomized clinical trial of methadone maintenance for prisoners: Results at 1-month post-release. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 91, 220–227. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein A. R. (2018). National Sheriffs’ Association, National Commission on Correctional Health Care (U.S.), National Institute of Corrections (U.S.), & United States. Bureau of Justice Assistance.

- Krawczyk N., Picher C. E., Feder K. A., Saloner B. (2017). Only one in twenty justice-referred adults in specialty treatment for opioid use receive methadone or buprenorphine. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 36, 2046–2053. 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., McDonald R., Grossman E., McNeely J., Laska E., Rotrosen J., Gourevitch M. N. (2015). Opioid treatment at release from jail using extended release naltrexone. Addiction, 110, 1008–1014. 10.1111/add.12894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez G. (2018). How America’s prisons are fueling the opioid epidemic. Vox. Retrieved April 22, 2022, from https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2018/3/13/17020002/prison-opioid-epidemic-medications-addiction

- Magura S., Lee J. D., Hershberger J., Joseph H., Marsch L., Shropshire C., Rosenblum A. (2009). Buprenorphine and methadone maintenance in jail and post-release: A randomized clinical trial. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 99, 222–230. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore K. E., Oberleitner L., Smith K. M. Z., Maurer K., McKee S. A. (2018). Feasibility and effectiveness of continuing methadone maintenance treatment during incarceration compared with forced withdrawal. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 12, 156–162. 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Commission on Correctional Health Care (NCCHC) (2016). Standards for opioid treatment programs in correctional facilities. In Standard O-E-02 health assessments. National Commission on Correctional Health Care. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2016a). Advancing addiction science, effective treatment for opioid addiction. Retrieved April 22, 2022, from https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/effective-treatments-opioid-addiction/effective-treatments-opioid-addiction

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2016b). Effective treatments for opioid addiction. Retrieved April 22, 2022, from https://www.drugabuse.gov/eff ective-treatments-opioid-addiction-0

- National Sheriffs’ Association (NSA) & National Commission on Correctional Health Care (NCCHC). (2018). Jail-based medication-assisted treatment: Promising practices, guidelines, and resources for the field. Retrieved April 22, 2022, from https://www.ncchc.org/filebin/Resources/Jail-Based-MAT-PPG-web.pdf

- O’Brien C. P., Cornish J. W. (2006). Naltrexone for probationers and prisoners. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 31, 107–111. 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor A., Bowling N. (2020). Initial management of incarcerated pregnant women with opioid use disorder. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 26, 17–26. 10.1177/1078345819897063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onion C. W., Walley T. (1995). Clinical guidelines: Development, implementation, and effectiveness. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 71, 3–9. 10.1136/pgmj.71.831.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeler M., Fiscella K., Terplan M., Sufrin C. (2019). Best practices for pregnant incarcerated women with opioid use disorder. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 25, 4–14. 10.1177/1078345818819855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich J. D., McKenzie M., Larney S., Wong J. B., Tran L., Clarke J., Noska A., Reddy M., Zaller N. (2015). Methadone continuation versus forced withdrawal on incarceration in a combined U.S. prison and jail: A randomized, open-label trial. The Lancet, 386, 350–359. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62338-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K., Strashny A. (2016). Characteristics of criminal justice system referrals discharged from substance abuse treatment and facilities with specially designed criminal justice programs (The CBHSQ Report). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Retrieved April 22, 2022, from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/report_2321/ShortReport-2321.html

- Snyder P. A., Hemmeter M. L., Fox L. (2015). Supporting implementation of evidence-based practices through practice-based coaching. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 35, 133–143. 10.1177/0271121415594925 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson J. (2020). Drug overdose deaths head toward record number in 2020, CDC warns. JAMA Health Forum, 1(10), e201318. 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stöver H., Michels I. I. (2010). Drug use and opioid substitution treatment for prisoners. Harm reduction journal, 7(17). 10.1186/1477-7517-7-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). Tip 63: Medications for opioid use disorders (HHS Publication No. [SMA] 18-5063EXSUMM). Rockville, MD. Retrieved April 22, 2022, from https://store.samhsa.gov/product/TIP-63-Medications-for-Opioid-Use-Disorder-Executive-Summary/PEP21-02-01-003

- Sugarman O. K., Bachhuber M. A., Wennerstrom A., Bruno T., Springgate B. F. (2020). Interventions for incarcerated adults with opioid use disorder in the United States: A systematic review with a focus on social determinants of health. PLoS One, 15, e0227968. 10.1371/journal.pone.0227968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vocci F. J., Schwartz R. P., Wilson M. E., Gordon M. S., Kinlock T. W., Fitzgerald T. T., O’Grady K. E., Jaffe J. H. (2015). Buprenorphine dose induction in non-opioid-tolerant pre-release prisoners. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 156, 133–138. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger L. D., Showalter D., Lambdin B., Leiva D., Wheeler E., Davidson P. J., Coffin P. O., Binswanger I. A., Kral A. H. (2019). Overdose education and naloxone distribution in the San Francisco county jail. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 25, 394–404. 10.1177/1078345819882771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson N., Kariisa M., Seth P., Smith H., 4th, Davis N. L. (2020). Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2017-2018. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 69(11), 290–297. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6911a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White N., Ali R., Larance B., Zador D., Mattick R. P., Degenhardt L. (2016). The extramedical use and diversion of opioid substitution medications and other medications in prison settings in Australia following the introduction of buprenorphine-naloxone film. Drug and Alcohol Review, 35, 76–82. 10.1111/dar.12317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaller N., McKenzie M., Friedmann P. D., Green T. C., McGowan S., Rich J. D. (2013). Initiation of buprenorphine during incarceration and retention in treatment upon release. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 45, 222–226. 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]